1. Introduction

1.1. Problem Statement

It is common for autistic females to have an associated mental illness (MI) (

Section 1.7). Females with autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) commonly camouflage, or mask, their condition (

Section 1.3) and therefore if they present with ASD at all, they first present with their mental illness or illnesses. As a result there are many studies of the prevalence of MI in diagnosed autistic women, but very few of the prevalence of ASD in women with an MI. MI is more difficult to manage in the presence of ASD (

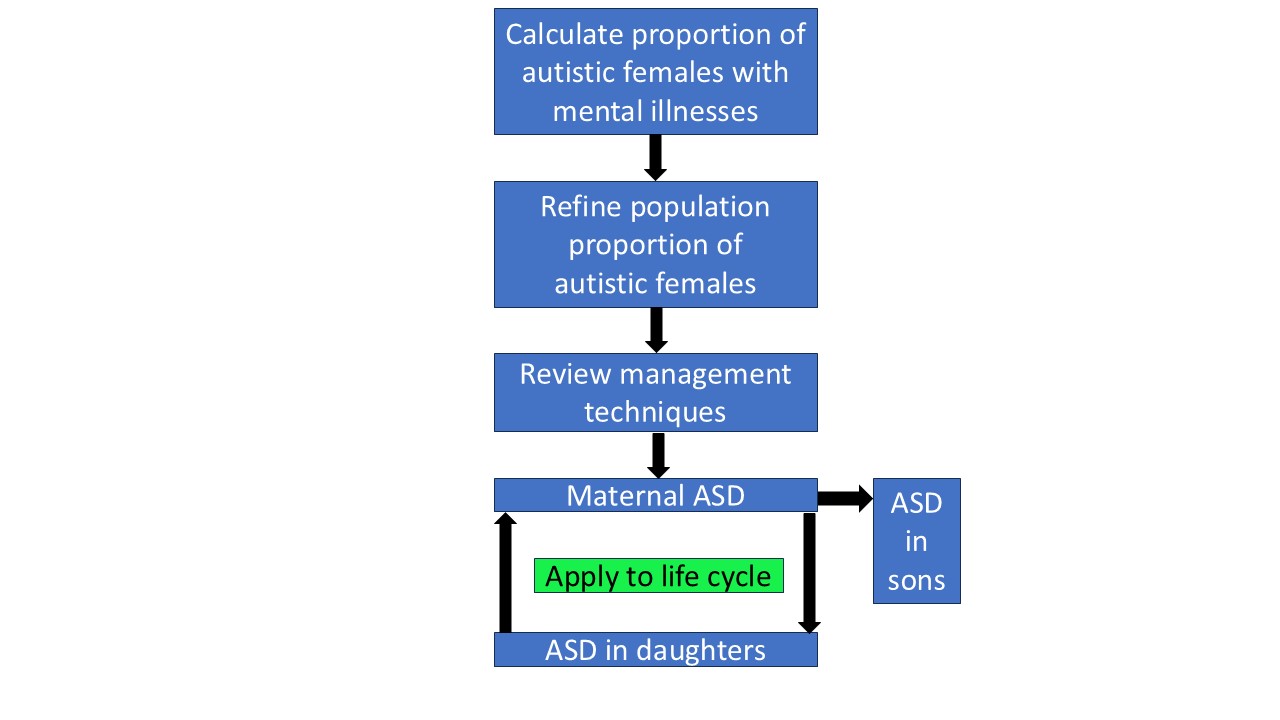

Section 3.4.1), so finding the ASD is critical for effective management. Key to finding the extent of the problem is the value of the overall prevalence of female ASD, which is used to calculate the proportion of females with ASD in MI. This paper will present information that the overall prevalence of both ASD in females and the prevalence of ASD in female MI are both far higher than generally thought, and for the first time calculate the proportion of young women in a number of MIs who are autistic, and consider the consequences for management over the intergenerational cycle.

1.2. The Importance of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) as a Mental Health Comorbidity in Adolescent Girls and Young Women

It is self-evident that to manage ASD you have to know it is present. If female ASD is not diagnosed prior to transitioning to adult care, it is likely the diagnosis will not be made (

Section 1.7), especially in the presence of MI. This will impact the entire intergenerational cycle since maternal undiagnosed ASD affects the prevalence and severity of perinatal depression, which in turn impacts the severity of mental health and associated problems in her offspring, and in particular in her daughters into the next generation.

In 2024 Cage et al. [

1] surveyed 225 autistic adults, of whom 50 had autistic children. The autistic adults ranked 25 research topics in order of importance to them. The rankings included:

First: Mental health conditions and mental well-being.

Second: Identifying autistic people/diagnosis.

Fifth: Issues impacting autistic women.

This paper will address the relationships between these three topics. The primary task is to calculate for the first time the proportion of young females with mental illnesses who have comorbid ASD. It will show why they are unknown, how to calculate the proportions, why they are important to know, and then discuss ways to improve diagnosis, therapy and service delivery for these girls and young women.

ASD is a neurodevelopmental disorder with two major domains: persistent impairment in reciprocal social communication and social interaction, and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests or activities. This latter domain includes hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input. It is defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5

th edition Text Revision 2022 [

2]. The first version (DSM-5) was published in 2013. It is a deficit model which expresses the behaviors as disorders compared to normal behaviors. Since that time there has been growing interest in an alternate philosophical model emphasizing difference rather than deficit. This model of neurodiversity, where the neurodivergent differs from the neurotypical, is outlined in

Section 1.5 and is the model favored in this paper.

There is extensive qualitative information that female ASD is considerably commoner than current estimates (

Section 1.3). Recent quantitative information suggests it is at least as common as in males [

3] and possibly even more common over the life span [

4]. There has only been one published numerical estimate of female ASD prevalence allowing fully for biases in recognition and diagnosis [

4]. If this estimate of 6% is valid then clinical reasoning about female ASD needs a new frame of reference. ASD may be comorbid with most mental health conditions [

5] and this is not well recognized by mental health services (

Section 1.7). If the ASD diagnosis is made, 75% are first diagnosed with another condition and the ASD diagnosis may be delayed 8 years [

6]. This makes these conditions more difficult to manage in psychosis [

7], anorexia nervosa [

8,

9,

10,

11], and anxiety and depression [

12,

13], with increased risk of suicide [

14]. It is well documented that therapy in ASD has to be tailored to the neurodivergent mind or it will not succeed (

Section 4.4). This paper aims to use Bayes’ theorem [

15] to calculate the proportion of females with an MI who have comorbid ASD. This derivation crucially requires the true value of the prevalence of ASD in the female population, designated P(ASD). The outcome sought is to demonstrate the clinical importance of ASD in female MI and the necessity to increase the rate of ASD diagnosis. This would lead to better targeted therapy, improved access by increased efficiency of management, and consequent greater overall mental wellbeing.

The format of the study is a population analogy of a clinical case: diagnosis, therapy and prognosis. The paper is then an exercise in quantitative induction with subsequent risk management. The problem with testing a hypothesis by deductive reasoning is that in an observational study information supporting an alternative hypothesis tends to be discounted [

16,

17], particularly if alternative explanations are deemed to be rare. The starting point of this paper is the observation that female autism is not rare, and so its importance needs to be explored. This type of study is hypothesis-generating. The aim here is not a clinical diagnosis but an assessment of the clinical risk of the comorbid relationship for females with MI who are on the spectrum and who have not been diagnosed. The focus will be on cis-gender girls and young adult women. Specific problems for transgender individuals will not be examined. The reason is this complicates the definition and quantification of female MI. Transgender ASD with comorbid MI is an extremely important area, and likely fairly common. The range of data so far reported is wide and, with discordant sex and gender reporting, is more complex. It deserves its own study.

A much higher prevalence, or probability P(ASD), in the female population might show levels of ASD in MI that must be addressed. A key factor contributing to this problem is camouflaging, also described as masking.

1.3. Camouflaging

P(ASD) has generally been reported as around 0.01, or 1% of the female population. There appears to be a female phenotype not well recognized [

18] and a significant feature is female camouflage, now well described qualitatively [

19,

20] and with quantitative estimations of about 90% of ASD females obtained on history [

20,

21], or by observation of its effect [

4]. The effect observed by parents and teachers is excellent behavior in school or even preschool, with meltdown between the classroom and home. The information on this behavior was gained on parental history in a survey over 3 months during routine diagnostic practice. The listed ages of the girls in

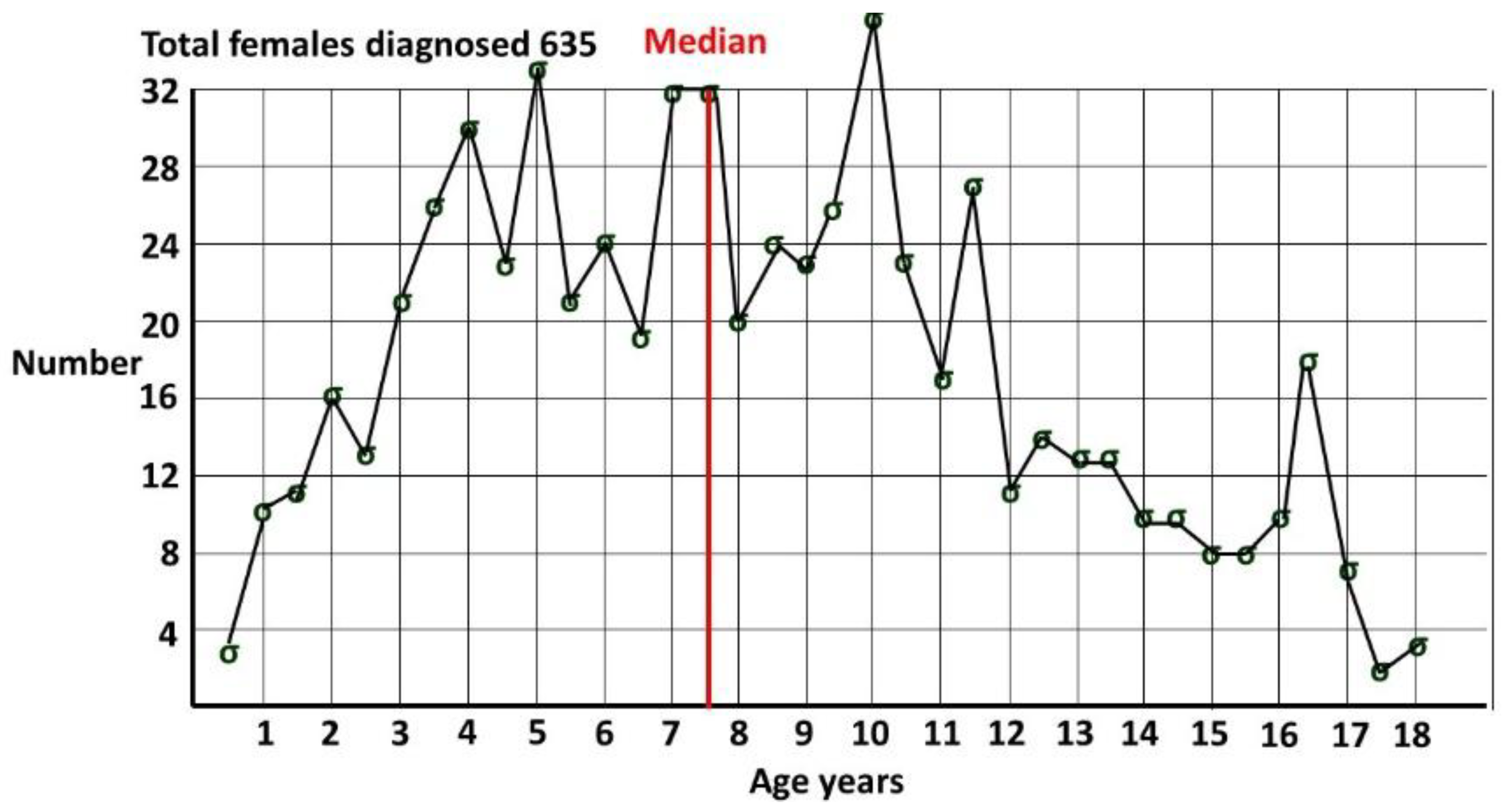

Table 1 were at the time of the study, which sets an upper limit on the age of onset of the behavior. There are two peaks corresponding to starting school and onset of puberty, where there is increased stress. Median age was 8 years 4 months, range 3 years 4 months to 17 years 4 months, and 15.9% started under 6 years. Camouflaging is clearly causing psychological distress from an early age.

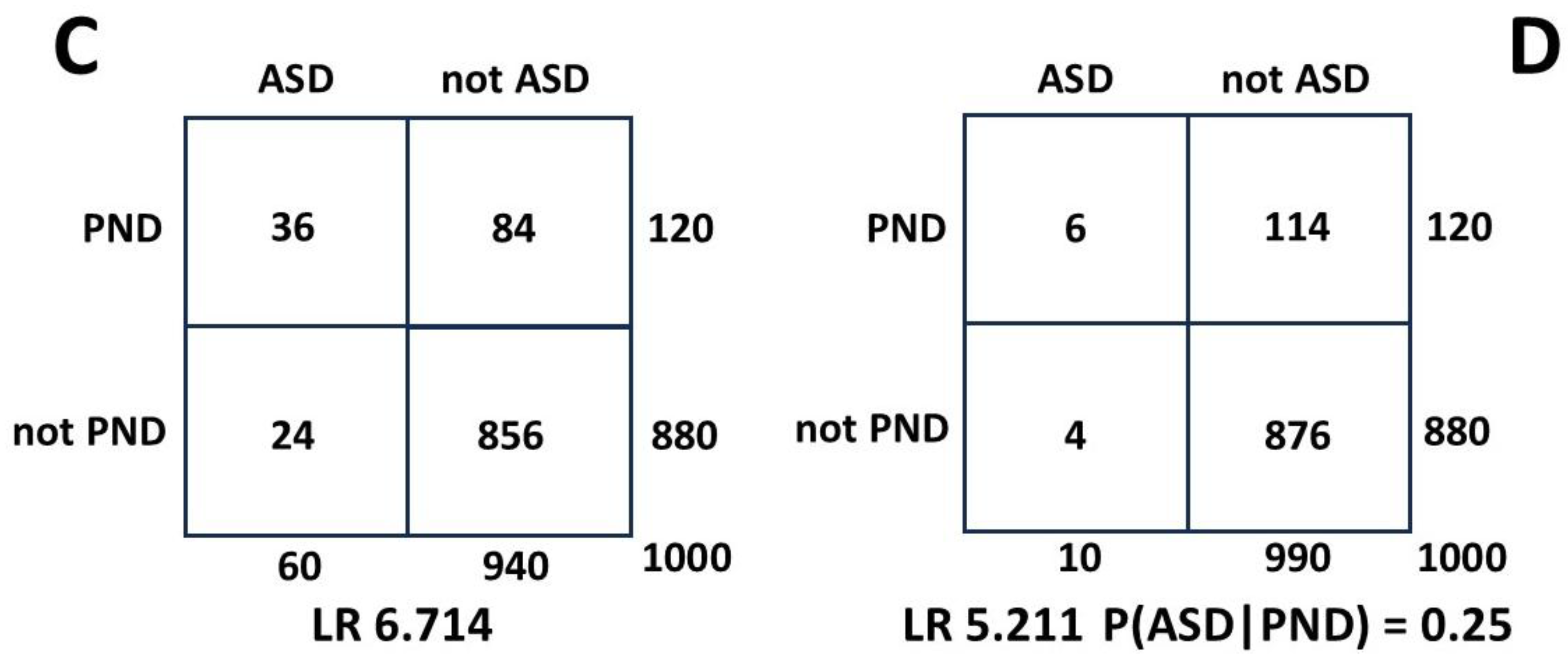

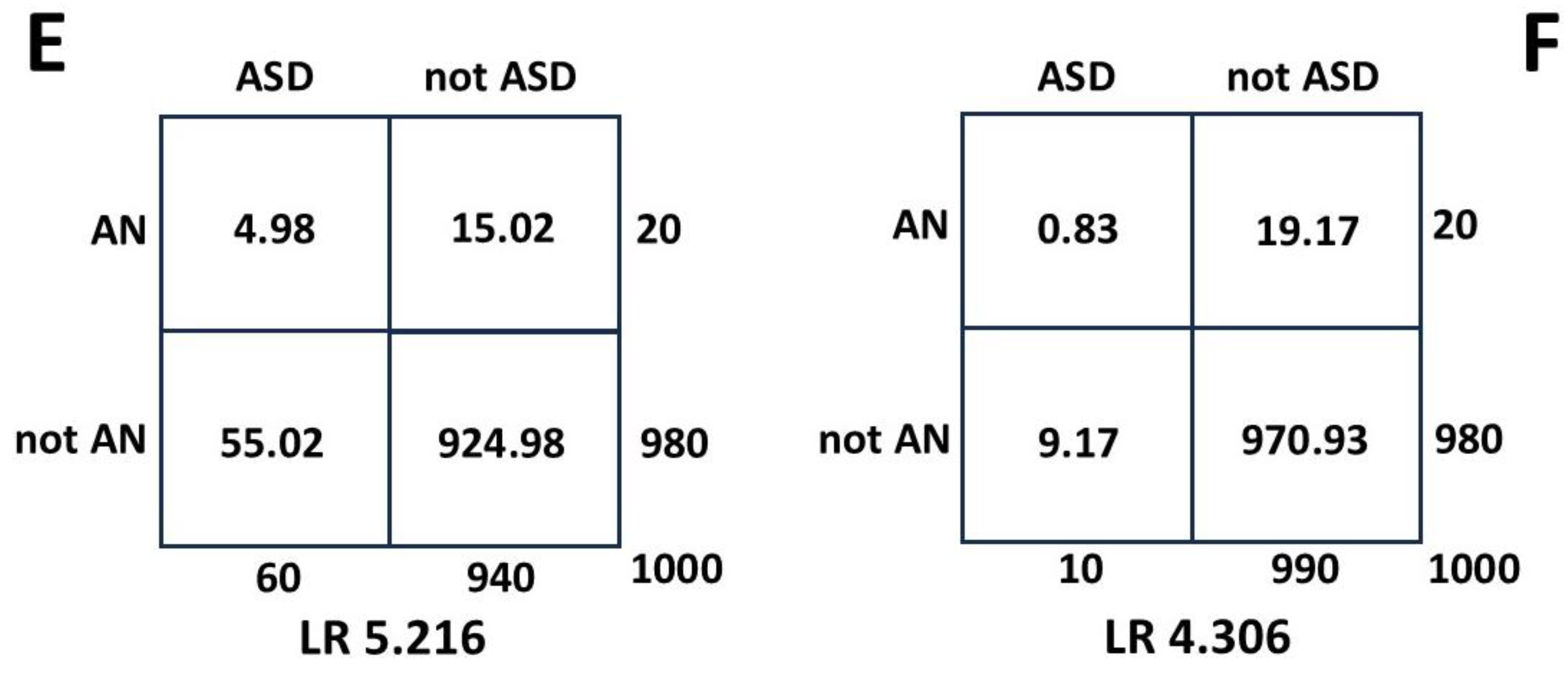

Though camouflaging was first described by Wing in 1981 [

22], it is only since 2015 that interest has grown exponentially (

Figure 1).

With such a high proportion of individuals camouflaging it is not surprising that a minority of females are recognized as possibly autistic [

4], let alone diagnosed. The neurotypical world of the majority imposes high social expectations on female behavior. From a young age autistic girls strive to fit in with their neurotypical peers, at great psychological cost [

23]. The key to successful management is the acceptance of their neurodivergence, and the tragic irony is they are so good at hiding it. A key aim of this paper is to reduce this effect by increasing general knowledge of ASD and to try to turn a vicious circle into a virtuous one.

Camouflaging in ASD is part of a larger problem in female neuroscience. There is a large gender bias where for example only 0.5% of brain imaging articles have considered factors specific to women, such as postpartum depression [

24].

1.4. Diagnostic Overshadowing

The underdiagnosis of ASD in the general female population is exacerbated when ASD is associated with an MI due to diagnostic overshadowing, the misattribution of ASD features to the MI. This may hinder a patient from receiving an appropriate assessment because the assessor reviews her symptoms through the lens of another condition. The overshadowing can occur in the other direction, and an autistic young woman may be pejoratively labelled as “hysterical” [

25]. Rather than the archetypical externalizing male presentation, female autism usually presents differently, with more internalizing symptoms [

26] and “girly” interests [

4]. Of particular relevance when considering the challenges faced by females with ASD is the concept of neurodiversity.

1.5. Neurodiversity: The Set of the Neurotypical and the Neurodivergent

“Who in the world am I? Ah, that’s the great puzzle!”.

Alice, from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Lewis Carroll [

27]

The basic premise of neurodiversity as expressed by Singer [

28] is that there is a range of difference in individual brain function and behavior traits. Those who diverge from the societal norm are not necessarily disabled. While some may be disabled, as within the neurotypical majority as well, the problem is that the dominant societal paradigm does not suit neurodivergent people. The scope of neurodivergence is a matter of active debate [

29], but there is no disagreement that autism is central to the concept. The root cause of most of the problems is a lack of mutual understanding, characterized as the double empathy problem [

30]. The implications for management are simple but profound. Neurotypicals, both therapists and contacts of all degrees of intimacy, need to understand the mutual misunderstanding and allow for it. Neurodivergent individuals need to do the same, but as “aliens on Earth” have to make extra adjustments. Society as a whole is not going to readily understand, and the neurodivergent are going to often have to adjust. Practical advice might be to learn to camouflage well when necessary but learn strategies to minimize the pressure. Then make your excuses, leave, and become again your authentic self.

The therapeutic interaction should be identity affirming [

31]. It is important to acknowledge that identity is a key component of mental health treatment. The act of validating symptoms and experiences, allowing accommodations when requested, and exploring identity formation regardless of diagnosis, allows all patients who identify as neurodivergent to benefit from treatment. The aim of therapy is not to “cure” the individual. Autistic spectrum conditions (ASC) and ASD can usefully be seen as different, with the disorder as a subset of the condition [

4]. The aim is to minimize the disorder element and manage in society. An ASC is permanent and not a pathology, but an ASC individual who has significant problems coping in a pervasive neurotypical environment, with or without a comorbid illness, has a disorder and requires assistance to cope successfully. Obviously understanding that ASD is present is required to manage it and professional assistance is required for comorbid MI. About 80% of autistic females have a comorbid mental health condition (

Section 3.1.12). The comorbid illness often presents during the transition period to adult care (

Section 3.1) and the transition is often poorly managed [

32,

33]. The pathological element of ASD usually has a comorbidity as the major driver [

34] and the analysis of this relation is a major theme of this paper.

1.6. ASD and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Within neurodivergence there is generally believed to be a polythetic taxon, which is a shared pattern of features that need neither to be universal nor constant among members of a class. The class includes ASD and ADHD. There is a continuous field of clinical characteristics which are best managed without worrying about a precise categorical diagnosis. A categorical diagnosis is fraught with danger since factors contributing to a behavior not consistent with the category chosen may be misinterpreted or overlooked. Neurodivergence is part of the differential diagnosis of a quiet girl failing academically at the back of the class. She may be camouflaging her autistic communication style to avoid standing out. She might have been bullied by classmates or shamed by the teacher when she tried to participate. She might not be able to focus or concentrate, especially if she has no interest in the subject. She may have an auditory processing problem and not be able to follow the teacher. She may be very good at deliberately processing information but the teacher may be skimming the topic or switching subjects too often. She might be very sensitive to noise and too distracted to pay attention. She may be comorbidly highly anxious. She just hates being in that class or that school. To tease out the multilayered elements requires careful listening to her in a non-threatening environment. Management will require a multidisciplinary approach involving environmental adjustment, education in mutual communication of the neurodivergent and neurotypical, talking therapies and medication, tailored to her individual circumstances. She must be comfortable with the program. For autistic management in particular, a top down approach will not work [

15]. Any distinction between ASD and ADHD is complicated by many ADHD features being also explained by features of ASD [

35]. Since ADHD, like ASD, is not necessarily seen as a mental illness, a rate of comorbidity will not be considered in this paper. The possibility of cryptic ASD should always be considered when ADHD is diagnosed and vice versa. The term AuDHD for the combination is now being used within the neurodivergent community and by peer reviewed papers, but it is not yet a formal diagnosis. The two are so intertwined, if ADHD and an MI comorbidity are not responding to therapy, ASD should be considered. The synergy in AuDHD appears to cause a high risk of behavioral, psychiatric and clinical conditions [

36] including substance abuse, accidents and offending behavior [

37]. My own clinical experience suggests anxiety and oppositional defiant disorder are particularly relevant features. While the overlap of ADHD and ASD may create diagnostic confusion the problem is much wider, and extends to most areas of MI.

1.7. Mental Illness Guidelines and ASD.

On the adult side of the pediatric/adult clinical divide mental health services do not appear to have fully appreciated the potential importance of ASD as a comorbidity in MI, especially in females. This may also apply to transition guidelines. There are a growing number of papers considering the relationship but these are generally coming from an ASD focus, and invariably conclude adult mental health services need to pay more attention to ASD. The lack of diffusion across the barrier is likely due to not appreciating either the frequency or the severity of the interaction of ASD and MI. The product of frequency and severity is the way risk is quantified. The literature on the severity of the relation again comes from an ASD focus, and the lack of a quantified P(ASD) until recently, together with female camouflage, have hidden the frequency. We will examine a selection of recent papers and guidelines as examples that demonstrate aspects of the problem.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guideline in 2022 [

38]. Depression in Adults: treatment and management. Listed as comorbidities are bipolar disorder, PTSD and anxiety. If there are “language or communication difficulties eg autism”, the guideline suggests linking to the NICE Autism guideline, but does not mention female camouflage possibly hiding comorbid ASD. The assumption appears to be that the possibility of ASD has been recognized. If it has not, the skills of female camouflaging would require very good understanding of female ASD by the clinician. The language and communication skills in female ASD can appear quite satisfactory, and the pathway would be difficult to navigate for a general practitioner/primary care physician.

An adolescent depression primary care screen in 2018 did not mention ASD among mental health risk factors [

39].

A study of treatment resistant depression in primary care in 2018 [

40] did not mention the possibility of comorbid ASD, though it did generate a response which did so [

41].

A 2021 paper on postpartum depression and psychosis [

42] examined the prevalence of neurodevelopmental disorders in the children but not in the mothers.

It has been suggested [

43] pediatricians have a role to play in reducing perinatal mortality and notes some do screen for maternal depression. ASD is not mentioned. We would add that this is an area where pediatric expertise could indeed be very useful if looking for it became routine, perhaps in partnership with midwives [

44] aware of both depression and ASD (

Section 3.1.6,

Section 4.5).

A study [

45] characterizing treatment-resistant anorexia nervosa (TRAN) from 2000 to 2016 in patients aged 17 and upwards was published in 2021. It did not mention ASD but did speculate that TRAN might be a different concept warranting additional research. There is qualitative information to support this [

32,

46].

The American Psychiatric Association 2023 Guideline [

47] for treating eating disorders lists other psychiatric disorders that should be particularly sought. ASD is not among them.

A recent review of eating disorders [

48] does not mention the relation of ASD to anorexia nervosa (AN) though it does mention the relation to avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), discussed in

Section 3.2.5.

A 2023 paper [

49] on difficult to treat bipolar disorder mentioned ADHD, but not ASD.

A discussion of treatment resistance in mental illness [

50] lists autism being misdiagnosed as schizophrenia but does not list schizophrenia spectrum disorder as being comorbid with ASD.

A 2023 paper [

51] listing comorbidities of borderline personality disorder (BPD) quotes BPD as a comorbidity of 37.7% of ADHD but does not list ASD.

The obvious conclusion is that knowledge possessed by ASD focused practitioners, generally but not solely on the pediatric side of the divide, is not reaching our adult colleagues. If indeed the risk of undiagnosed ASD is much higher than currently believed, it becomes essential to manage it. It is to the elements of this risk assessment we will now turn.

1.8. Problems Diagnosing the Prevalence of Female ASD.

We can only rely on a measurement of female ASD prevalence P(ASD) if we are sure that all ASD patients in the measured population of interest have been recognized and diagnosed. Lack of initial recognition appears to be the major problem rather than diagnostic bias [

4]. Community professionals do miss girls on diagnosis [

4] but at a fairly low rate compared to research studies. In my referred community specialist clinic [

4] (males 1052 females 659) the male to female odds ratio (MFOR) was 1.596. A recent study [

52] showed a “leaky pipeline” in the comparison of the MFOR for the community versus research diagnosis of females. The research standard was the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) module 4. The MFOR for community databases of referred patients (males 9192 females 5768) was 1.594. The MFOR for research ADOS assessments (males 189 and females 25) was 7.56. The ADOS relies on an observation protocol and it is difficult not to believe that camouflage was a serious confounding factor. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) prevalence [

53] for ASD at 8 years of age is often incorrectly referenced as the prevalence of ASD. The age qualification is often omitted when cited. In any cohort the overall prevalence must be greater as cases accumulate after this age, as demonstrated in

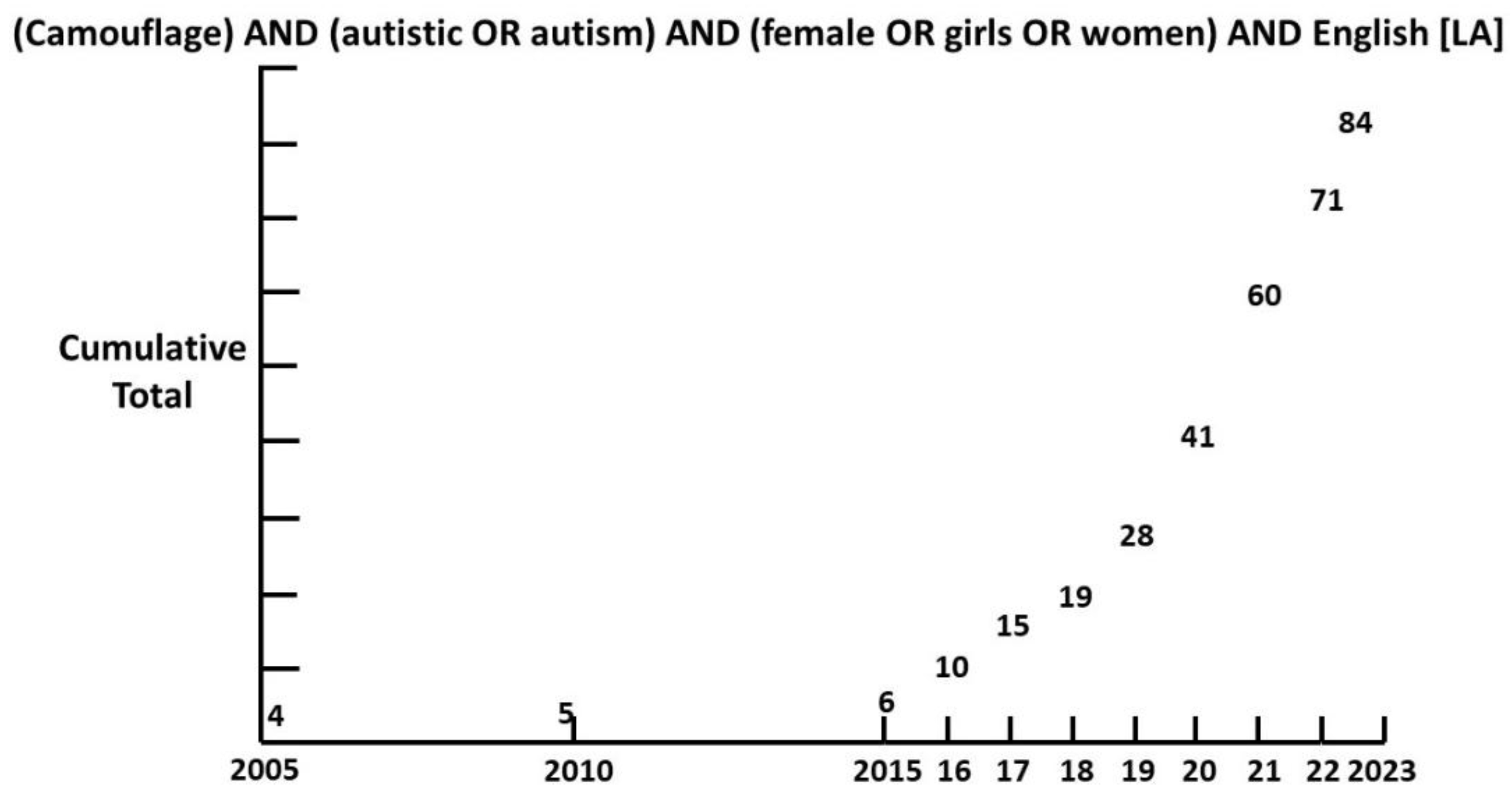

Figure 2 from my pediatric clinic, showing females diagnosed by me [

4], all with a known date of diagnosis. Females were defined by sex of assignation at the time of diagnosis. Median age of diagnosis was 7 years 6 months. At 8 years only around half the pediatric age diagnoses in females have been made.

2. Methods

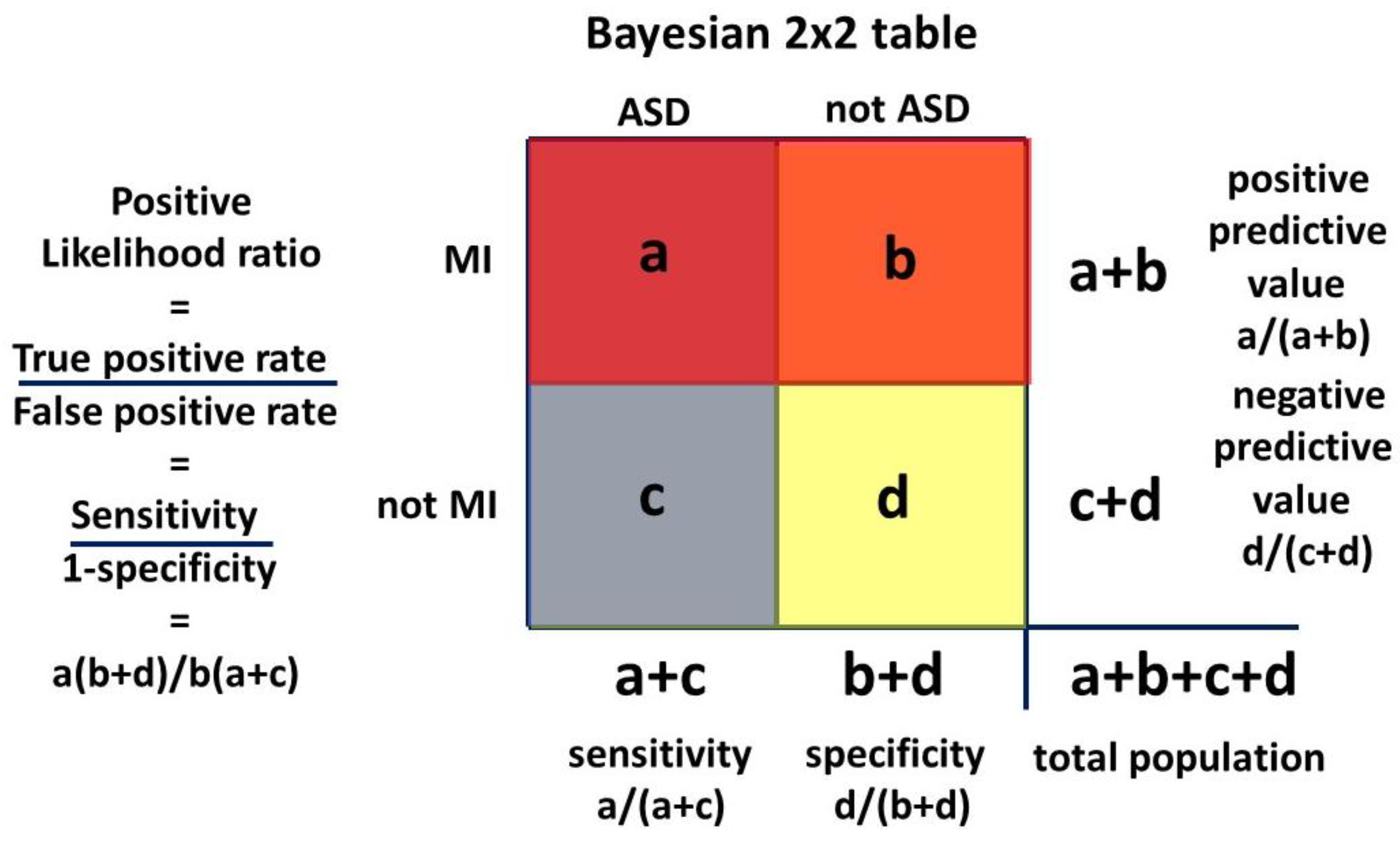

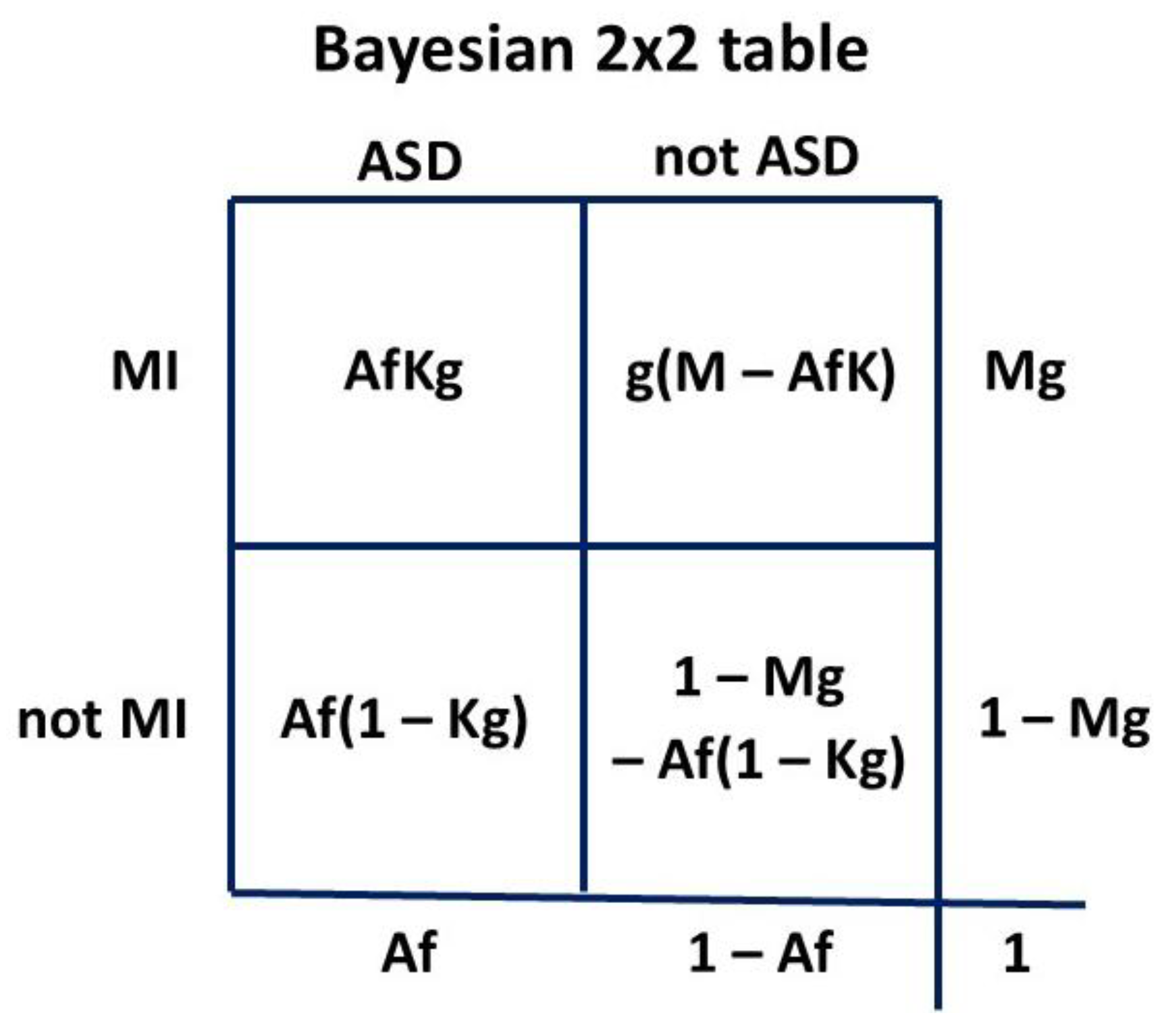

2.1. Conditional Probability and Bayes’ Theorem

Bayes’ theorem is a statistical method of taking initial (prior) information, and using further information to derive refined information. The process of clinical diagnosis is inherently Bayesian [

54]. Further information is sequentially added to a provisional diagnosis until the probability of the refined diagnosis is high enough to act upon. It is often the only way to reach certain conclusions in a timely manner. This is the case in this study. The process of refining basic data to derive a conclusion is induction, and is the bedrock of the scientific process. Due to the problems outlined in

Section 1.8 it would take many years to establish the proportion of ASD in female mental illnesses by direct measurement in those populations. Due to recent developments by the author of a new application of Bayes’ theorem [

15] and calculation of an unbiased value of 6.0% for the population prevalence of female ASD [

4,

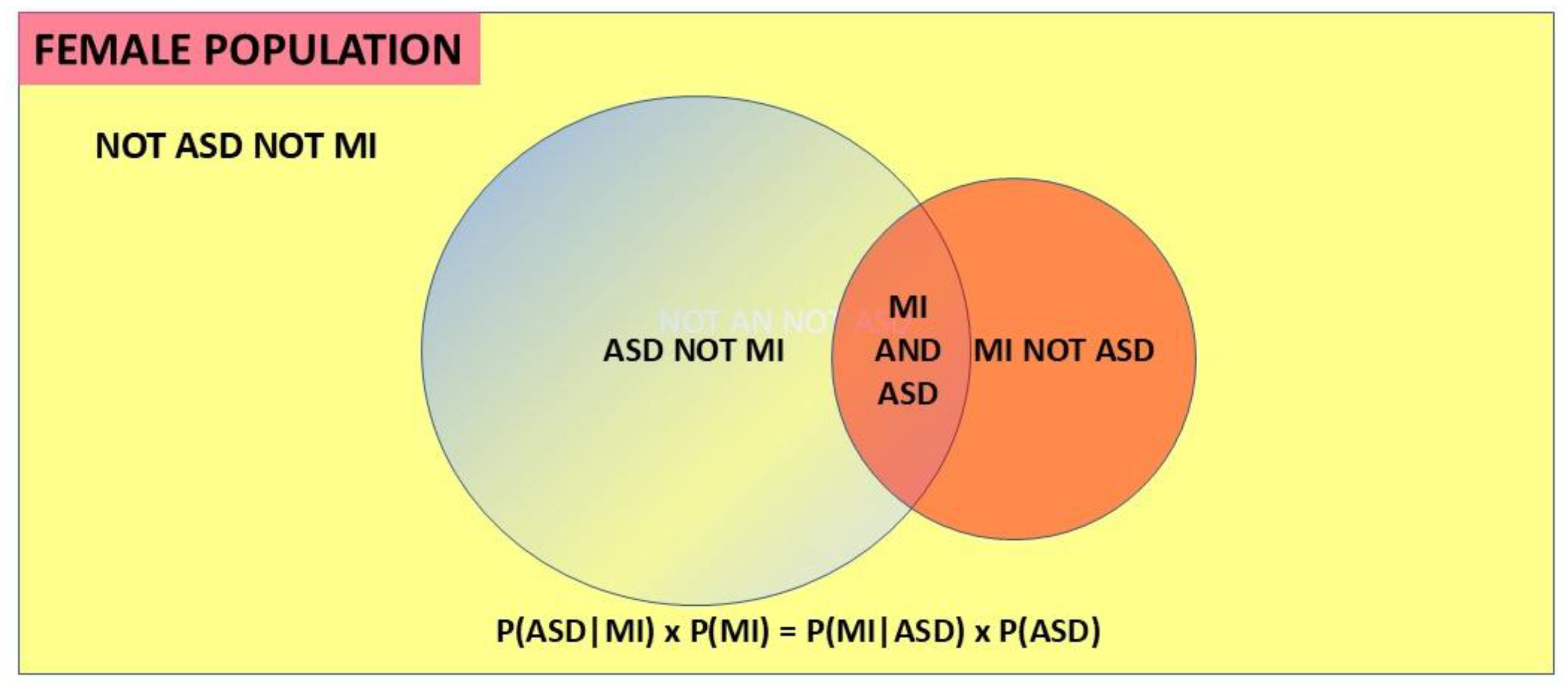

15], these proportions can be calculated using current published data, and their clinical importance assessed. There are four prevalence variables to consider. A prevalence is mathematically a proportion, or a probability. The first two variables are the female population prevalence of ASD, P(ASD) and of MI, P(MI). These are called base rates. The other two variables are conditional probabilities. When a proportion of population ASD interacts with the total population of MI, MI is designated the base and the interacting proportion of population ASD is designated the probability of ASD

given MI, or P(ASD|MI). Obviously then a proportion of population MI must interact with total population ASD, and then ASD is the base and the interacting proportion of population MI is designated P(MI|ASD). This is shown in the Venn diagram (

Figure 3). P(ASD|MI) is the variable we need to find. The probability of ASD in a population of MI can be found by using versions of Bayes’ theorem. The simplest forms of Bayes’ theorem are firstly the probability form:

Secondly another version, used in medical diagnoses, is the odds form:

Probability P and odds O are interconverted by the formulae:

The likelihood ratio (LR) is P(MI|ASD)/P(MI|not ASD). Here the MI is being used as a test for ASD, and LR is the ratio of the true positive rate and the false positive rate for the test. Hazard ratios (HR) are often reported in the literature and are mathematically equivalent to likelihood ratios [

15], though the derivation and purpose are different. Hazard ratios describe the relation at a particular time, and this must be kept in mind when interpreting the result, since the rate of diagnosis of each condition can change with age. The details of this form of Bayes’ theorem are discussed in

Appendix A. Both forms are used in the current paper to derive P(ASD|MI). Since female ASD is less visible than the comorbid MI we have a significant practical dilemma for the clinician:

MI given ASD: (MI|ASD). This is difficult. The combination is hard to manage because it is more complex than the MI alone. The therapist may lack the necessary skills, but knows ASD is present and can refer for expert help.

ASD given MI: (ASD|MI). This is much more difficult. The undiagnosed ASD with comorbid MI may be intractable to therapy and the therapist does not know why, and the person they refer to will probably not know either.

2.2. P(ASD)

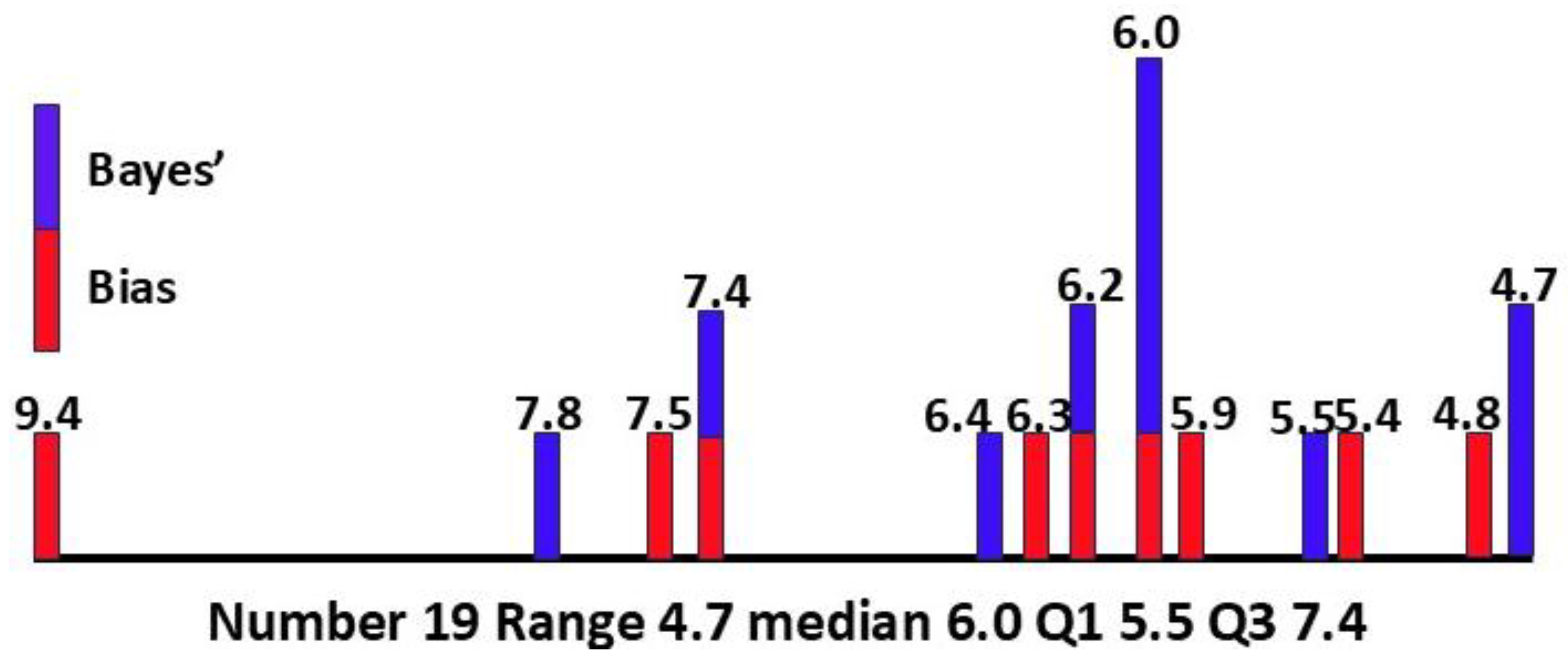

The value of P(ASD) is critical in both versions of Bayes’ theorem. The Bayesian relations hold if the unknown we are usually seeking, P(ASD|MI), is known and the unknown is P(ASD). P(ASD) was calculated [

15] using an HR in a Danish population study [

55] from 1981 to 2008. The data had quite different prevalences of anorexia nervosa (AN) and ASD to contemporary values, but the result of 0.060 was the median of the 19 values calculated to date (

Section 3.3). These include five calculated in this paper where the unknown variable was P(ASD).

If the estimate of 0.060 (6.0%) is indeed valid then the proportion of ASD in female MI becomes of significant quantitative importance in diagnosis, therapy and funding, and the risks can be estimated. The secondary data to which the formulae are applied, ie P(MI) and P(MI|ASD), are all referenced published values.

3. Results

3.1. P(ASD|MI) for Selected Mental Illnesses in Children, Adolescents and Young Adults

3.1.1. Context

We can now calculate the proportion of ASD given different mental illnesses. The range of values for P(MI|ASD) in a particular illness can be wide, and recent and reasonably conservative data have been used where available. There are in fact not very many published results and precise values are not critical. The aim of this study is to set a new frame of reference to establish the clinical importance of the relationship of the cryptic ASD with comorbid MI. One might substitute different published values for P(MI|ASD) and P(MI) but very few are likely to deliver a level of risk for P(ASD|MI) below clinical concern.

Figure 4 shows indicative timing of onset of comorbid illnesses in females, putting the results in context. Half of all individuals with a mental health disorder have their onset by 18 years, and 62.5% by age 25 [

56]. Mental illness is a problem for the young, emphasizing the importance of an informed transition to adult services.

3.1.2. Depression (DP)

Kirsch et al. [

57] gave a hazard ratio for depression-related diagnoses of 2.28 which by formula A2 gives P(ASD|DP) of 12.7%. Pezzimenti et al. [

58] for adolescents gave P(DP|ASD) of 0.202 and P(DP) of 0.084. With (P(ASD) of 0.060 this gives P(ASD|DP) of 0.144 or 14.4%. Hudson [

59] gave an effective lifetime hazard ratio of ~4 giving P(ASD|DP) of 0.203 or 20.3%, consistent with the comorbidity with ASD leading to more prolonged, visible or severe depression over time.

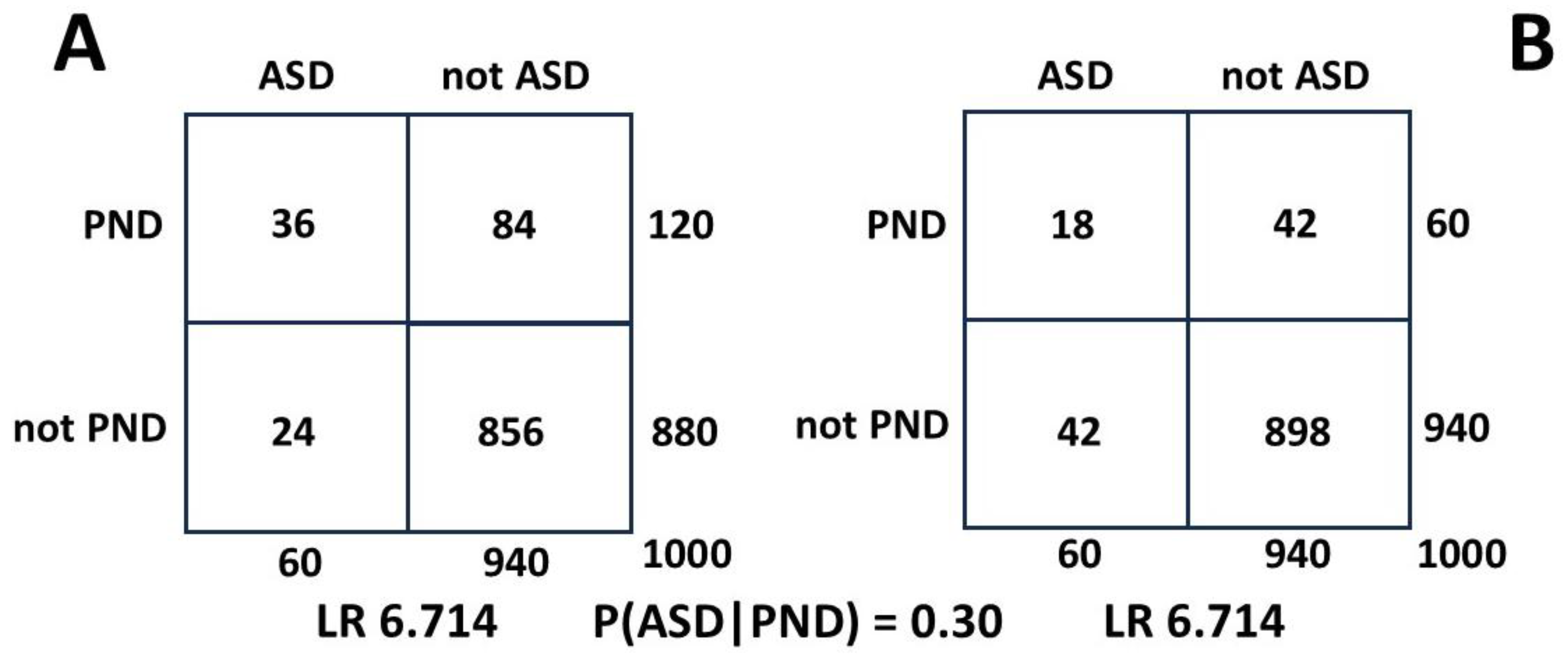

3.1.3. Perinatal Depression

Pohl et al. [

60] found a postnatal depression rate P(PND|ASD) in autistic women of 60%. This was potentially signaled by an antenatal rate of 40%. Luca et al. in a 2017 study [

61] found a postnatal rate in pregnancy, P(PND), of 11.5%. Then we find:

The likelihood of autism in postnatal depression may be a shocking 31.3%. Two thirds of these mothers will have antenatal depression [

60] and it is essential to make neurodivergence friendly arrangements to ease the stress of birthing for autistic mothers [

44].

3.1.4. Anxiety Disorders (ANX)

Kirsch et al. [

57] gave a hazard ratio for anxiety-related diagnoses of 2.91 which gives P(ASD|ANX) of 15.7%. Croen et al. [

62] gave data for anxiety related diagnoses in adults, allowing calculation of a hazard ratio of 3.22 which gives a P(ASD|ANX) of 0.170 or 17.0%

3.1.5. Social Anxiety Disorder (SA).

Values vary for P(SA|ASD) but are generally high. If we use an indicative value of 0.45 with a lifetime P(SA) of 0.103 [

63] then with P(ASD) of 0.060 we find a P(ASD|SA) of 0.262 or 26.2%. This is higher than the estimate for anxiety-related diagnoses but this is not surprising given that social communication is the major problem in ASD. The conclusion overall is that ASD is common in anxiety disorders.

3.1.6. Bipolar Disorder (BP)

A cohort study of 267 young adult females with ASD were matched with 534 referents and the hazard ratio for BP in ASD was 5.85 [

57]. Given P(ASD) of 0.060, this gives P(ASD|BP) of 0.272 or 27.2%.

3.1.7. Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorder (SSD)

Published values for P(ASD|SSD) vary widely, likely due to significant diagnostic overshadowing, but the upper estimates are about 0.5. [

64,

65] Overall P(SSD) is about 1% with a male:female ratio of 1.4:1 [

65,

66,

67] giving a female P(SSD) of 0.0083. If we take P(SSD|ASD) to be 0.06 [

68] then by Bayes’ theorem with P(ASD) of 0.06:

This suggests values for P(ASD|SSD) of up to 0.5 or 50% are plausible. This is supported by the shared genetics of SSD and ASD [

69].

3.1.8. Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

From a UK mental health trust study [

70] of females aged 4-17: females with OCD + ASD (121), OCD (522), ASD (1625). Then P(ASD|OCD) is 121/522 ie 0.2318 or 23.2%. This paper also gives P(OCD|ASD) of 0.0745. With a female OCD prevalence of 0.015 [

71] Bayes’ theorem gives a P(ASD) of 0.047, another independent measure of the high prevalence of female ASD. The relatively young age range may explain the value at the low end of the overall calculated range of P(ASD).

3.1.9. Anorexia Nervosa (AN)

There is reasonable current agreement [

72,

73] on a range of about 0.20 to 0.30 for P(ASD|AN). A value of 0.25 was used to calculate P(ASD) [

15]. Margari et al. [

74] give data to calculate a P(AN|ASD) of 0.068 compared to the published value [

15] of 0.083. With the same values [

15] for P(ASD|AN) of 0.25 and P(AN) of 0.02 this gives P(ASD) of 0.074. This is the third quartile value of the published median estimate of 0.060 and independently corroborates the estimated P(ASD). A further value of female P(AN|ASD) from Camm-Crosbie et al. [

75] of 10.7% gives a P(ASD) of 0.047, at the lower end of the Bayesian range. The 3 values for P(AN|ASD) give a mean of 0.086 or 8.6%, much lower than the erroneous value of the inverse probability of 20-30% (

Section 4.3).

3.1.10. Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD)

The value is uncertain with many overlapping features and uncertainty about the age when the diagnosis should be considered but 14.6% [

76] is widely referenced giving P(ASD|BPD) of 0.146. This value was used to calculate a P(ASD) of 0.060 [

4].

3.1.11. Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

PTSD is experienced by 10-12% of women [

77]. There is not a precise figure for female P(PTSD|ASD) but a lifetime figure may be as high as 60% [

78]. Then we find:

Considering the stresses that autistic women have to cope with [

19] it is not surprising that up to 30% of women with PTSD may be autistic and will need to be diagnosed so the PTSD is not perpetuated by inappropriate therapy.

3.1.12. Any Mental Health Disorder (MI)

Nyrenius et al. [

79] give P(ASD|MI) as 18.9%. Studies of P(MI|ASD) are quite heterogeneous. LeCavalier et al. [

80] give any externalizing disorder as 80.9% and any internalizing disorder as 43.6%. Lever et al. [

81] give 79% with no gender breakdown but female rates are typically higher than male rates. If we take 80% as indicative then with the National Institute of Mental Health [

82] 2021 value for female P(MI) of 0.272 and P(ASD) of 0.060 we obtain P(ASD|MI) of 0.176 or 17.6%. These values of 18.9% and 17.6% are less than for some individual conditions because it is common with ASD to have multiple mental health comorbidities [

83]. The outcome of the calculations of the proportion of women with comorbid ASD in mental illness are summarized in

Table 2. The overall magnitude of P(ASD|MI) reinforces the primary thesis that female ASD is being routinely missed in female mental illness. Nearly one in five women with mental illness appear to be autistic. Generally P(MI|ASD), P(MI) and P(ASD) are secondary (2

0) data and P(ASD|MI) can be calculated. P(ASD|MI) is occasionally available as a given value. If so and P(MI) and P(MI|ASD) are also available as 2

0 data, then another value of P(ASD) can be calculated. These additional results for P(ASD) were added to give overall values in

Section 3.3.

3.2. Proportion of Female ASD in Conditions Consequent on or Associated with ASD and Female MI

3.2.1. Attempted Suicide

While not a categorical mental illness, attempted suicide (AS) is an indicator of a serious underlying problem [

14]. A Danish registry study by Kolves et al. [

84] showed a marked increase in attempted suicide in female ASD, P(AS|ASD), compared to the non-ASD population, P(AS|not ASD). The comparison gave a likelihood ratio of 6.0. The HR was derived from AS per person-years so the resulting P(ASD|AS) of 0.277 would be the probability the patient on presentation has ASD. The clinician in practice has to first assess the patient by how they present, and then consider the variables that need to be diagnosed and managed. This probability of 27.7% strongly suggests seeking ASD is essential in female attempted suicide, with tailored prevention strategies [

84]. If the presence of ASD is recognized in attempted suicide in treatment resistant depression the knowledge is of itself therapeutic [

13].

3.2.2. Completed Suicide

The rate of completed suicide (CS) has been examined through the Swedish national register [

85]. The rate in female ASD, P(CS|ASD), was much higher than in the general population, P(CS|not ASD), and even higher in high functioning ASD. The relative risk for CS of the entire female ASD cohort compared to the control females was 0.0032/0.0003 or 10.667. This is P(CS|ASD)/P(CS|not ASD), mathematically equivalent to the LR and giving P(ASD|CS) of 0.405, or 40.5%. This is additional evidence that ASD increases the severity of comorbid mental illness. The relation of ASD with depression (mean 15.8% from

Table 2) is sobering, the increase to 27.7% for AS and to 40.5% for CS supporting the deleterious effect of ASD on depression severity [

13]. This is consistent with the finding for lifetime ASD/depression comorbidity found in

Section 3.1.2. The American Psychiatric Association’s clinical review journal suggests ADHD as a risk factor for suicide but does not list ASD [

86]. A study of autism and autistic traits in those who died of suicide [

87] gave a value for P(ASD|CS) of 0.414, very similar to the Bayesian calculation. The methodology however was completely different. The authors assessed coronial reports and medical records. There was no gender breakdown, but the risk of suicide in ASD may be higher in females than in males [

87] and so a P(ASD) value for females may be a low estimate. We can then reverse engineer a value of P(ASD) in appendix B of 0.062.

3.2.3. Sexual Violence

Cazalis et al. [

88] point out that being on the autistic spectrum is characterized by “experiencing difficulties in social communication such as decoding hidden intentions and emotions of others, understanding implicit communication and elements of context.” They found 88.4% of autistic women had suffered sexual violence (SV), starting in two thirds before the age of 18. This compared to 27% of the general female population [

89] giving P(ASD|SV):

Consequences of sexual abuse before age 18 include depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance abuse and suicide [

90]. As for all the mental illnesses discussed, thinking of ASD on presentation would permit targeted interventions likely to be effective in neurodivergence. Childhood abuse is particularly important as an upstream root cause of the cascading downstream consequences.

3.2.4. Sleep Problems

Gowin et al. [

91] looked at sleep problems (SLP) and the risk of suicidal behavior as preteens at age 10 transitioned to early adolescence at age 12. Increased suicidal behavior was associated with the severity of SLP, insomnia and daytime somnolence, anxiety and depression, family conflict and being female. Neurodivergence as a covariate was not considered. Estes et al. [

92] examined SLP in children aged 6 to 12 years. SLP were present in 84.4% of autistic girls compared to 44.8% of typically developing girls. Anxiety was present in 41% of the autistic girls but the rate of SLP was the same whether anxious or not, and so anxiety was of no value as a red flag for ASD. They concluded that SLP in autistic females (SLP|ASD) should be carefully considered, and that increased awareness of ASD in SLP ie P(ASD|SLP) could improve identification of females on the autistic spectrum. Pediatric clinicians are very aware of P(SLP|ASD) since it is so common (0.844). An estimate of P(ASD|SLP) was not given. By Bayes’ theorem:

While clinically significant due to the underestimation of P(ASD) it is still not very common in 6-12 year old girls. During adolescence and into adult transition it becomes much more problematic. Halstead et al. [

93] found 90% of autistic adults (sample 2/3 female) have clinical SLP. A health professional had not been consulted in 64.4% and of those who sought help up to 80% had an unsatisfactory outcome. While the rate of SLP in adult ASD is essentially unchanged from childhood the rate for adult women overall has declined to 21.8% [

94], and therefore P(ASD|SLP) by Bayes’ theorem has increased to 24.8%, comparable to the categorical MI already listed in

Table 2. Since the treatment of SLP in women already diagnosed with ASD is unsatisfactory, it is inevitably going to be worse if the ASD has not been diagnosed. Unlike in the general population, the suicide mortality risk is higher for autistic females than males [

95]. There is then a substantial population of females with ASD and SLP (5.4% of women) with a high risk of suicide who are poorly recognized and ineffectively treated.

3.2.5. Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder

Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) is a feeding and eating disorder recognized in DSM-5 that presents with substantial heterogeneity across the life span. There are three main drivers for the symptomatology:

Avoidance based on sensory characteristics of food.

Apparent lack of interest in eating and food.

Concern about adversive consequences of eating.

These features strongly suggest an overlap or comorbidity with ASD. However a 2023 review of ARFID diagnostic assessment [

96] did not consider ASD as a factor. A recent and likely reliable population estimate of female ARFID prevalence P(ARF) gave 0.0249 or 2.49% [

97]. P(ARF|ASD) in children of all genders has been recently assessed by Koomar et al. [

98] as 0.21 or 21%. The ARFID MFOR is likely 1:1.7 [

97] which suggests a Bayesian calculation of P(ASD|ARF) will underestimate the proportion in females. Then a lower limit for P(ASD|ARF) will be:

We can estimate female P(ARF|ASD) in the Koomar study. Simons Foundation Powering Autism Research for Knowledge (SPARK) data providing the overall 0.21 value gave an ASD MFOR of 1.71:1. [

52] Let the male value be

m, then to deconstruct the P(ARF) weighted average:

If we assume that the ARFID MFOR is the same for ASD females as for the general female population then:

Haidar et al. [

99] in 2024 reported 139 cases of ASD in 319 cases of ARFID from the British Paediatric Surveillance Unit and the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Surveillance System. ARFID males were 54.5% and females 45.5%. Median age was 11.9 years, range 5-18. The percentage with ASD was then 43.57%. No gender ratio for the ASD cases was provided, but we can estimate the female P(ASD|ARF) using the ARFID MFOR [

97] expressed as 0.558:1. Then let female P(ASD|ARF) be

f. Then:

Wronski et al. in 2025 [

100] reviewed the relation between ARFID and mental and somatic conditions from the Swedish National Patient Register from 2004 to 2020. They found a Cox regression hazard ratio for ASD of 12.10, giving P(ASD|ARF) of 0.436. In

Appendix A we find that the hazard ratio underestimates the value by ~15%, giving a likely P(ASD|ARF) of ~0.501 or 50%. These values lie within the first Bayesian calculated range. As expected clinically, a very high proportion of girls with ARFID, at least 40%, and probably higher, appear to be autistic, and it is essential to consider the diagnosis to provide optimum intervention.

3.3. Validation of the Female Prevalence Value for P(ASD)

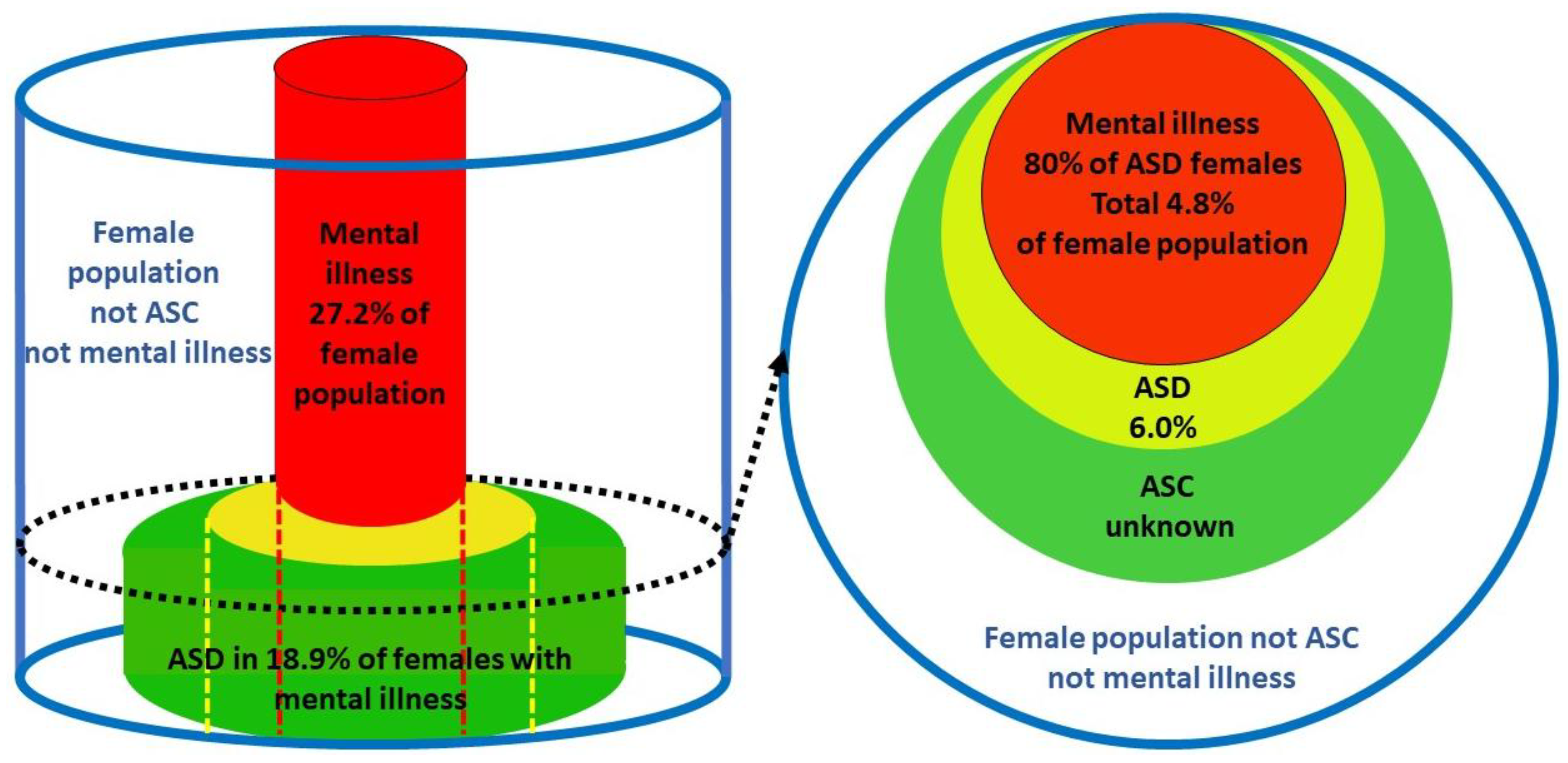

The relation of autism and mental illness in the female population is summarized in

Figure 5.

We can use these data to obtain another independent value for P(ASD) using Bayes’ theorem:

In addition to the 14 values already determined [

15] we can now add 0.064, from

Section 3.1.8, 0.047, from

Section 3.1.9, 0.047 and 0.074 and from

Section 3.2.2, 0.062. The median value of P(ASD) is then 0.060, with Q1 0.055, Q3 0.074, IQR 0.019, range 0.047-0.094, number of values 19.

For individual mental illnesses, values for P(MI|ASD) and P(MI) are quite variable due to heterogeneous populations, different diagnostic methods and diagnostic overshadowing. Average values for an individual comorbid illness P(MI|ASD) and mental illness P(MI) are going to be very different due to the natural variation in prevalence of the different mental illnesses. The degree in which they are comorbid with ASD is going to vary, and there are different degrees and combinations of multiple comorbidities in individual patients. All these variations are integrated in the variables for overall female mental illness, ie P(MI|ASD), P(ASD|MI) and P(MI), shown in

Figure 5. The value of P(ASD) derived from the data for overall MI was 0.064. The mean for the other 18 measurements of P(ASD) was 0.063. The two general methods [

4,

15] of determining P(ASD), by bias calculation from the author’s database and Bayes’ theorem from secondary peer reviewed data, employ completely independent mathematical processes. A comparison of the results is shown in

Table 3. The obvious strong correlation means that the Bayesian methodology alone is adequate to refine the P(ASD) value as more secondary data become available. The Bayesian methodology depends on data for females only, without comparison with male data. It relies on fewer assumptions than the bias method. The Bayesian values have a quite narrow interquartile range of 0.009. The results suggest the overall median of 6.0% and mean of 6.3% for the prevalence of female ASD are plausible. The combined values are skewed to the high end of the range so the median was preferred for calculating P(ASD|MI), giving more conservative values.

The overall calculated values and descriptive statistics for P(ASD) are shown in

Figure 6.

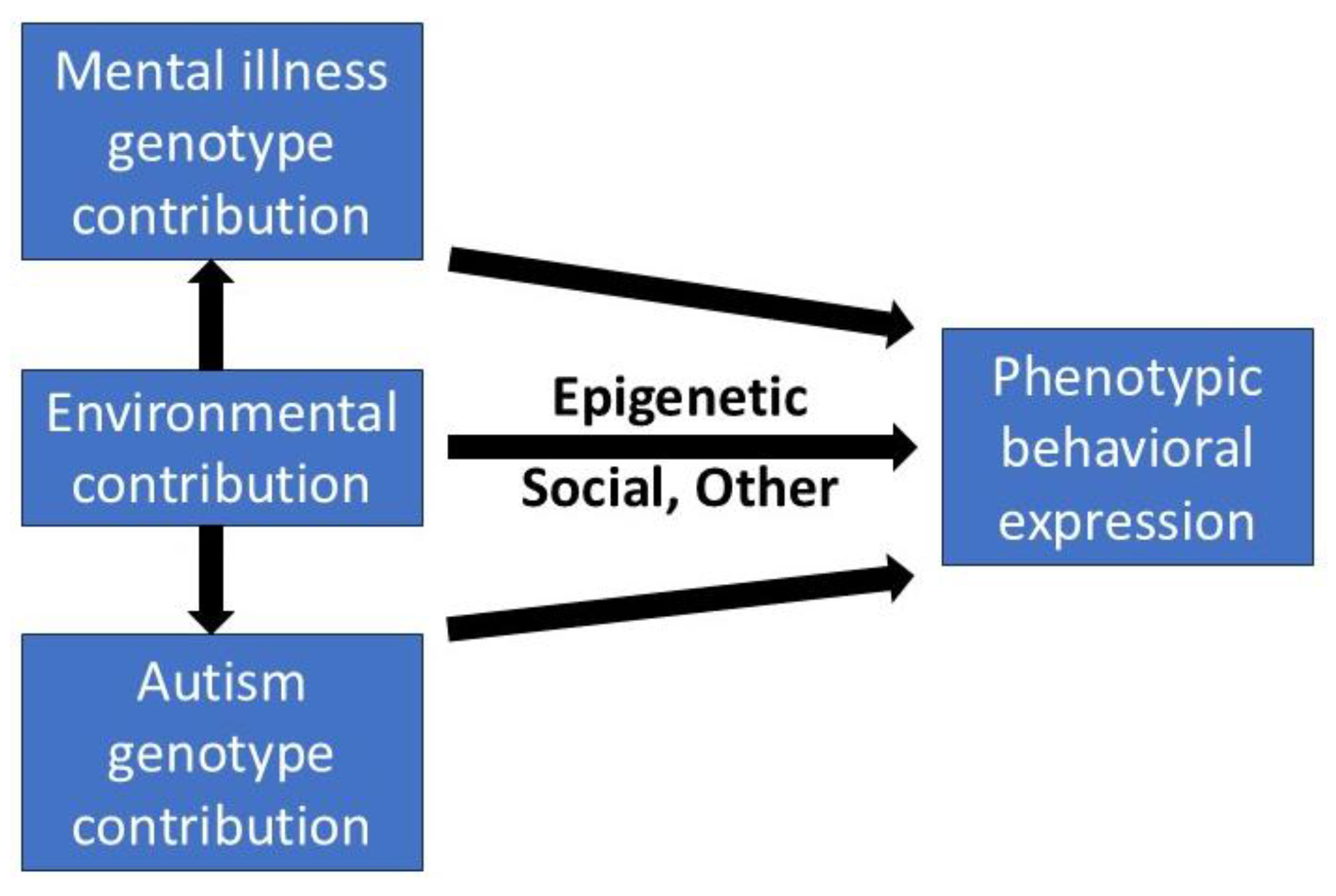

ASD is a complex outcome of multiple genes, and environmental factors including epigenetics. This will produce a continuous transition between the neurodivergent and the neurotypical. It does appear that it is a clinical problem for about 6% of women.

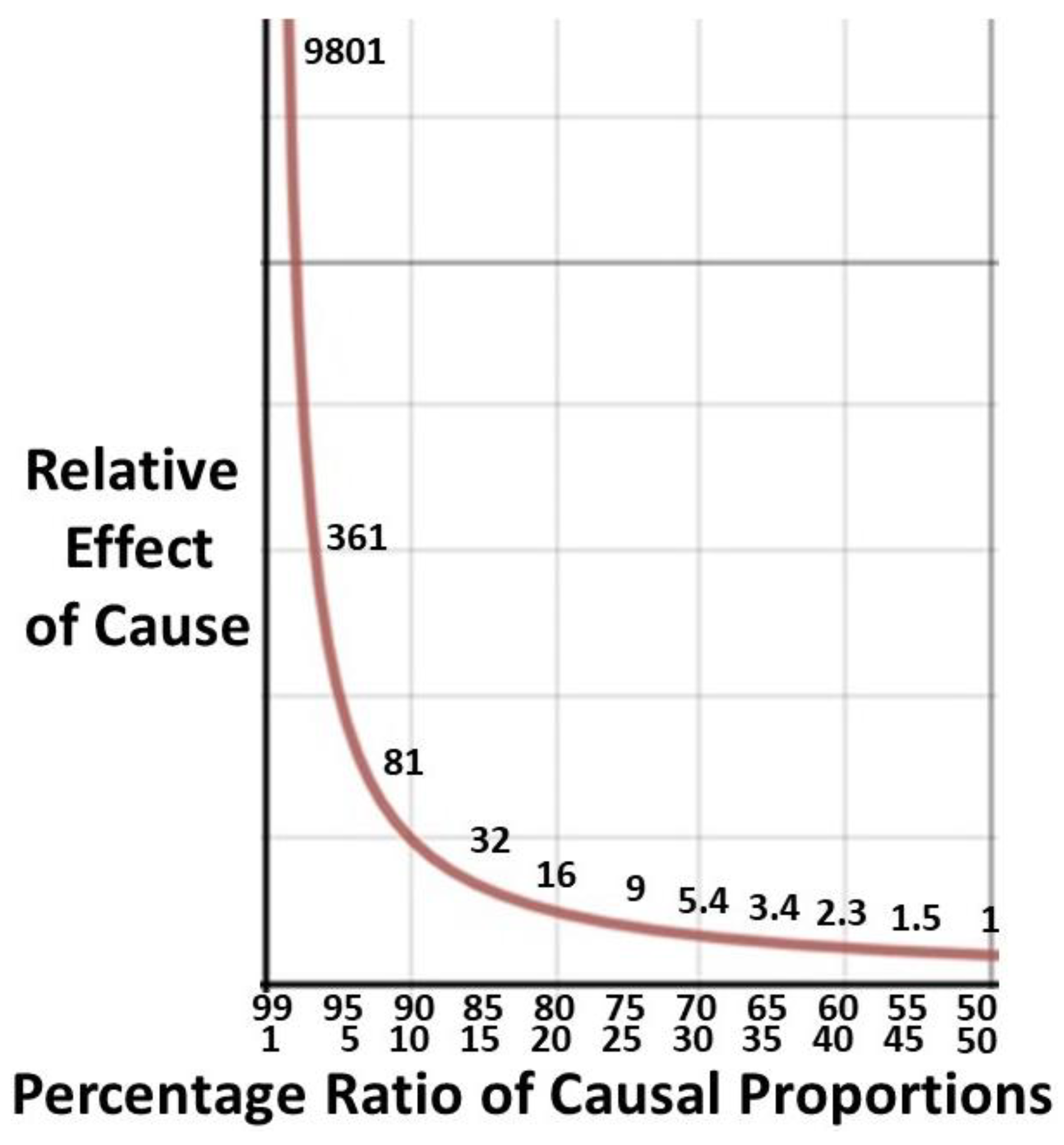

3.4. Degree of Benefit: Pareto Calculations

3.4.1. The Pareto Principle in Health

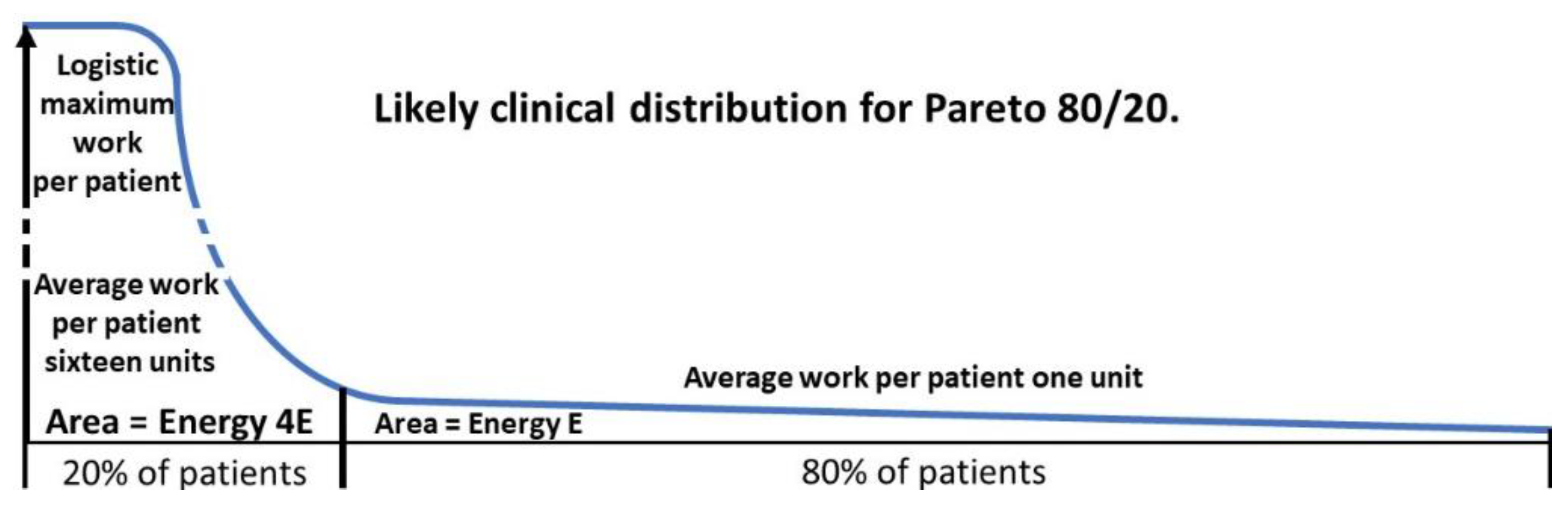

The Pareto principle is commonly called the 80/20 rule where 20% of the cause leads to 80% of the effect. While the variable strength of a particular cause will be a continuous power function, the division into 2 parts comparing the effect of the average of the strongest 20% of the cause to the average of the remaining 80% is a useful simplification. There may be multiple causes depending on the scenario but for the effect of ASD on female mental health we will consider ASD as an independent cause. From

Table 2 it can be seen that the prevalence of ASD in most MI is in the range 15-30%. This makes a Pareto analysis potentially useful, since there is considerable evidence the presence of ASD makes the MI more severe, for example with the stress of camouflaging in depression [

101,

102] and with AN more difficult and expensive to treat [

Section 3.4.3]. In mental health financial cost is a useful measure but is not necessarily the limiting variable. This is often a lack of trained staff poorly distributed in the population. A useful analogy for the drivers is the first law of thermodynamics. The amount of energy remains constant but can be moved around to do work. We will define a unit of energy as what is necessary to do the work to deliver a unit of service to an average patient in the less difficult group. This could equate to funding or performing a service. The two proportions do not have to be 80/20 and do not even have to add up to 100%. The Pareto principle seems to have wide application. We will now analyse why this might be so and apply it to health management.

3.4.2. Derivation of Pareto Formulae

The aim is to derive formulae to estimate the gain in system efficiency of management by treating the ASD of comorbid mental health patients in a manner empathetic to neurodivergence.

To examine the general case of the relation of two causal proportions in a given MI we will assume a binary risk with the higher risk group having the stronger effect. Let the higher patient proportion with the weaker average effect be p and the lower patient proportion with the stronger average effect be q. Proportion p of the patients requires proportion

q of the energy so an average patient in group p uses

q/p energy. An average patient in group q uses proportion

p/q energy. Then the energy cost ratio of the average high work patient in group q to the average low work patient in group p is (

p/q)/(

q/p) or (

p/q)

2. For the 80/20 rule the relative effect will be 16/1 (

Figure 7). The Pareto principle is said to be an empirical rule but in biology there is a plausible reason why it is rarely higher, say 90/10. Due to the exponential nature of cause and effect for delivery of a costly labor intensive biological service there will be a logistical upper limit to the ratio. The absolute ceiling will be the most intensive inpatient care possible or its clinical equivalent in the system of interest. There is evidence limited medical services do obey the 80/20 ratio [

50,

103,

104,

105] and the

p2/q2 ratio of 16/1 for the difficult 20% to the easier 80% reflects the logistic ceiling.

The likely patient work distribution for a ratio of 80/20 is shown in

Figure 8.

Focusing on the needs of the higher risk group is intuitively sensible but can be seen as inequitable if large numbers of patients get no care at all. Comorbid ASD is going to have a strong effect on the MI. We will quantify how diagnosing the comorbid ASD leads to a dramatic improvement in the entire group with the MI.

If we assume the energy cost of the service is the sum of the costs of individual consultations then the energy cost of the visits of the high work group q is:

The energy cost of the visits of the low work group p is p x 1.

Total energy cost in groups p and q in units of the work per average patient in group p is:

In a typical current reasonably well functioning health system the limiting variable will be staff availability. Group q will have been triaged for treatment but there will be a long waiting list for inclusion in the less severely affected group p. Since ASD makes MI more difficult to treat, the comorbid patients will be distributed preferentially into the higher work group q. In calculating a formula for the distribution of the comorbid ASD patients, in the entire (p + q) patients with a mental illness we will assume that on average the patients without ASD in each group, p and q, will require the same range of energy input as those with ASD. With overall P(ASD|MI) of nearly 20% it is likely that most of the patients in group q will have ASD. ASD should however be sought when assessing all MI patients since the patients in group p will also benefit. ASD does have continuous traits [

106] which will be distributed over a number of further patients in both groups. These patients will also benefit from an empathetic approach to neurodivergence and contribute an extra unmeasured benefit to the final outcome.

We then start with (p + q) patients with a mental illness (MI):

The average group q patient needs p2/q2 units of work. The average group p patient needs one unit of work.

Let the proportion P(ASD|MI) with comorbid ASD be m.

Then the number of patients with ASD is m(p + q).

Let the proportions of patients with ASD in groups p and q be s/(r + s) and r/(r + s).

Then the total work required by ASD patients in group q is p2/q2 x m(p + q) x r/(r + s).

The total work required by ASD patients in group p is 1 x m(p + q) x s/(r + s).

Total work required for all comorbid ASD patients is:

Let the average fractional efficiency gain by treating ASD patients in an empathetic neurodivergent manner be

e. Then the total reduction in work needed (= energy saved) in units required to treat group p patients is:

This energy can be used to service an extra em(p +q) (p2r + q2s)/q2(r + s) patients in the low work category p providing there is no removal of energy from the system. The rule should be a guide to the redistribution of resources, not a way to reduce them. Identifying ASD, especially in group q, gives a considerable positive opportunity dividend for therapy, where the clinical need far exceeds the resources. This is not immediately apparent from the formula, and we will calculate a plausible scenario.

3.4.3. A Worked Example

We can use data from anorexia nervosa to derive an indicative overall energy benefit. The 80/20 rule does appear to approximately apply for AN. About 20% of patients are refractory to treatment [

107]. P(ASD|AN) is about 25% [

15]. It is known that this group is more difficult to treat than AN alone [

8,

9,

10,

46,

108]. Successful treatments for this group are being found: a study [

109] has shown managing diagnosed inpatient AN/ASD patients accounting for their neurodivergence is effective and saves 32.2% cost per patient. Then an indicative

e is 0.322. P(ASD|AN) gives

m as 0.25. Most comorbid patients are likely to be in Pareto group q. A reasonable starting point then for an indicative efficiency dividend would be with both

p/q and

r/s being 80/20.

Then energy saved in group p patient equivalents by formula (2) is:

We have more than doubled the number of low work patients treatable in female AN, where a proportion is comorbid with ASD, by recognizing the ASD and managing it appropriately. This is the substantial result of diagnosing a common unrecognized but treatable comorbidity (ASD) which caused significant management problems in the initial diagnosed mental illness.

This example demonstrates how the study stimulates useful hypotheses. When we know P(ASD|MI) is clinically significant we can ask: What proportion of female patients with difficult to treat MI have comorbid ASD and what are the funding implications? “Difficult” would of course need to be defined and the mental illness designated. An observational study could follow and be compared with the theoretical result obtained above.

3.4.4. Downstream Effects

If a treatment gain is achieved there will be a major positive ripple effect due to significant improvement in personal, family and societal problems associated with unrecognized and undertreated mental illness. The ratio of direct treatment cost to overall societal cost for mental illness has been estimated to be about 4.7 [

110]. We then find the total useful societal energy gain (“heat” loss foregone) for our AN example is:

For every 100 patients (p + q) we would divert enough energy to treat an extra 393.5 group p patients, though in practice most of the energy would be potential, appropriately preventing adverse consequences in the downstream community.

As an example of downstream savings Luca [

61] found the average cost of an untreated postnatal depression mother/child dyad from conception to 5 years post-partum was

$31,800. P(ASD|PND) from

Section 3.1.3 is 0.313, so 31.3% of these dyads would be complicated by ASD. The societal ripple effect would give an extended average cost of 4.7 x 31,800 or

$149,460 per dyad. An example of useful intervention would be increased diagnosis of neurodevelopmental problems in the offspring [

42]. We can calculate the overall savings achieved by screening for maternal ASD in the antenatal period. Assume the costs of no treatment have a Pareto distribution and let the low initial average cost for the mother/child dyad in group p over 5 years be

z. The total cost of the patients

(p +

q) by formula (1) is:

The average dyad cost including ripple effect over 5 years is:

The proportion of patients with ASD is high at 31.3%. A realistic Pareto distribution would be

p/q of 70/30. Then the low average extended cost

z is

$64,054. The therapeutic effect of a diagnosis for mother is probably going to be quite high. The child would also be assessed as having an increased probability of ASD, and if diagnosed would receive early intervention, so aiming for a 50% saving (

e = 0.5) for comorbid dyads would probably be conservative. The proportion of ASD patients in group q is likely to be very high, say

r/s in groups q and p respectively of 90/10 then by formula (2) cost saving as multiples of

z is:

Then total 5 year extended cost saving is

$64,054 x76.685 ie

$4,911,981 for every

(p +

q) patients, giving % saving:

The substantial overall saving across all dyads is because most of the ASD/PND dyads are in the high cost Pareto group q. A 2023 paper on new screening recommendations for PND [

111] describes PND as the leading cause of overall and preventable maternal mortality. This will obviously cause severe downstream effects. The paper listed several comorbid mental illnesses but did not mention autism. A 2024 study [

112] using Swedish national registry data examined the aftermath of perinatal depression (PeND) from 2001-2017 inclusive. They observed that suicide from PeND accounts for 20% of maternal deaths in high income countries. Women with postpartum psychiatric disorders, including psychotic, affective and anxiety disorders, have an increased risk of death. They found that women with PeND had a high risk of death closely after diagnosis with a hazard ratio of 12.17 for suicide. This was attenuated over 12 months postpartum but was still elevated (HR~2) 18 years later compared to their parous genetic sisters who did not have PeND. This was independent of a prepregnancy psychiatric diagnosis and commoner under 30 years of age. The cause was unclear. They concluded that PeND required urgent detection and treatment. The possibility of comorbid ASD was not discussed but from their data P(ASD|PND) may have been up to 40%. There are physical risks for mothers with autism and their babies, including preterm delivery, especially extreme preterm, small for gestational age [

113], increased ceserean delivery and preeclampsia [

114], all of which may increase postnatal stress. The practical outcome of these results is the need to redesign a significant proportion of female mental health diagnosis and management. We will now discuss the cycle that must be broken.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Intergenerational Cycle

Let us enter the cycle with a pregnant autistic young woman. Her autism is undiagnosed, as is her antenatal depression. She develops visible PND but her autism remains hidden. This causes prolonged PND resistant to treatment and exposes her child to developmental risks, which vary with the persistence of stressful exposure; from early sensorimotor white matter tract impacts to later interregional connectivity problems. Both relate to PTSD [

115]. The maternal depression may last for several years [

112], and the effects include behavior problems, lower math skills and adolescent depression [

116]. Epigenetic effects of stress in early life include on genes for glucocorticoid receptor, brain derived neurotropic factor and serotonin transporter and may lead to later major depression, generalized anxiety and schizophrenia [

117]. For the autistic daughter bullying at school is a particular problem. Bullying of any child causes increased risk of depression, anxiety and suicide, and school avoidance, truancy and dropping out of school will exacerbate the mental health issues [

118]. Autistic children are victimized more, and girls, being more socially motivated than boys, are at higher risk [

119]. Finally viral infections during pregnancy can cause autism in the child. Of particular note is congenital rubella [

120]. It is ironic that with the antivaccination hysteria induced by the fraudulent MMR study, MMR immunization is protective against one cause of autism. So the daughter continues the cycle unless ASD is diagnosed and managed. The relations are demonstrated in

Figure 9.

4.2. Stumbling Blocks

In adults identification is not made and services are not accessed [

121]. Neurotypical people tend to have less positive first impressions of autistic people [

122], most commonly because they appear awkward and lacking in empathy. Health workers are not necessarily immune [

8]. ASD should be considered a possible underlying condition in adult psychiatry. There is no easy way of ruling out ASD in this population [

123,

124]. For anxiety and depression more session time is needed. More medication is used in the ASD comorbid group implying unresponsiveness to talk therapy or more complexity [

125].

Malik-Soni et al. [

33] find transition to adult ASD services has the following multiple problems: Services are accessed by only 1/5 of autistic youth. About 70% of pediatricians do not support youth during the transition process and >50% of families lack information on how to proceed. Little is still known about the effects of comorbid MI. Adult physicians need to monitor ongoing symptoms of ASD-which can intensify and diminish-to guide diagnosis and treatment choices. Specific barriers include a shortage of health care services, poor physician knowledge, cost of services, lack of family and individual knowledge, stigma and language barriers.

We would add that language here refers to non-native speaking patients, and does not include double empathy problems with lack of mutual understanding in one’s native language.

4.3. Conditional Probability: Transposing the Conditional

When searching for conditional probabilities of ASD/mental illness it was routinely found that the data were transposed, or if a conditional probability was unknown the transposed probability would be reported in a non-specific way. Truly useful information would be that no result could be found, rather than the ambiguous and confusing wrong information. This is an example of a baseline fallacy. For P(AN|ASD) we need an accurate P(ASD). If we take P(AN) as 0.02 and P(ASD|AN) as 0.25 [

15] then with P(ASD) of 0.060 P(AN|ASD) is 0.083. or 8.3%. There is literature corroboration of 0.068, or 6.8% [

69] and 10.7% [

75] for an overall mean of 8.6% (

Section 3.1.9) The transposition can potentially have unfortunate consequences. The proportion of female patients with anorexia nervosa believed to be autistic is well established to be about 20-30% [

72,

73] but this information is often given under a heading of the likelihood of developing AN if you are autistic. This could lead an autistic teenage girl to incorrectly believe she has a high chance of developing AN, the MI with the highest mortality [

126] and only a 20% chance of complete recovery [

127]. With a high level of anxiety, depression and food sensitivity to deal with already this would not be helpful. We can also surmise that the future is much more hopeful with the new information on the different causes of the comorbid AN [

8,

32,

46] and the improved outcome with therapy recognizing neurodiversity [

109]. Ironically the problem here is the unrecognized P(AN|ASD), the reverse of the usually unknown P((ASD|MI). Understanding of the logic of conditional probability remains poor. It needs to be continually reinforced [

128].

4.4. Effective Therapy

The key to effective therapy is understanding neurodiversity. Neurodivergent and neurotypical are just different ways of thinking. Neurodivergence is not necessarily inferior and may only be disabling due to mutual misunderstanding in an overwhelmingly neurotypical environment. Understanding neurodivergence is critical for helping autistic adults cope in all walks of life including health [

129]. The World Health Organization definition of Health requires “a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing…” [

130]. ASD does not meet this definition of health, but the definition should be accepted for ASC (

Section 1.5). The neurodivergent minority is going to struggle in a predominantly neurotypical world, so assistance must be twofold; to optimize social adaptation to that environment, but also to treat comorbid mental illness in a manner empathetic to neurodivergence. A healthy outcome does not however require conversion to a neurotypical mental state. Neurodiversity recognizes that disability needs attention, but also recognizes that in particular areas neurodivergence can have great strengths [

131] which can be empowering and thereby, if necessary, therapeutic. Neurodiversity affirming interventions are essential [

132]. A recent Delphi study of management of comorbid ASD and AN emphasized the need to manage the individual in the context of ASD and that treatment goals should not aim to change autistic behaviors [

133]. The understanding of the importance of empathetic management of comorbid ASD in MI remains embryonic. A 2024 study [

134] of outpatient MI presentations in 13-24 year olds excluded ASD from consideration.

Rules for empathetic therapy include: recognize the centrality of the double empathy problem [

135]. There are variations in empathy in autistic people and some can be quite empathetic [

136]. Recognize that autistic people are often more deliberative and less intuitive than neurotypical individuals [

137]. Cognitive behavior therapy for example can be adapted to the core features of ASD [

138]. In designing therapy improvements researchers with lived experience of autism should be involved [

139]. We would add autistic clinicians, patients and parents. Specific areas for therapists suggested by Gilmore et al. [

140] include: Be a change agent in the mental health workplace. Make thoughtful language choices. Individualize treatment. Leverage patient strengths. Agree on practical goals to navigate life situations.

We would add that a necessary corollary to individualizing treatment is individual treatment. Autistic people are often uncomfortable in a group and trying to stretch therapist resources is pointless if the therapy will not work.

4.5. The Art of the Possible

We must trust that responsible governments will adopt a utilitarian approach and generally provide services doing the most good for the greatest number. To do this they require an evidence base, in particular if the service has received little attention in the past. It is not strictly true that management always requires measurement [

141], but if you want evidence-based policy it helps to provide quantitative evidence, otherwise governments have a tendency to find policy-based evidence [

142], and policy based on evidence and evidence based on policy are definitely not commutative. If governments have evidence they tend to apply risk management. ASD is common in young women with mental health issues, a population at risk. The commonly occurring ASD increases the severity of their condition, and so the risk, the product of frequency and severity of outcome, is high. Since female ASD is cryptic the obvious next step is a screening process. There are effective screening mechanisms which can be incorporated in normal care [

44] once the possibility that ASD may be present has been recognized [

4]. There is a clear road map for effective therapy (

Section 4.4) and it is cost-effective (

Section 3.4.3).

The neglect of female ASD in adult mental health has been due to inertia in knowledge transfer. There is no obvious political issue, and the solution lies within the health field itself. As the Pareto examination indicates, it is possible to achieve a significant improvement in mental health coverage without extra cost. If the knowledge is transferred the stumbling block will be training extra practitioners and getting them to go to the regions, but you have to start somewhere, and the following section shows how some difficulties may be overcome.

4.6. It Takes a Village

According to the African tradition, it takes a village to provide a safe, healthy environment for children [

143]. This conveys the message that it takes many cooperating people to provide complete childcare. Two elements relevant to health are social connectedness where different agencies can cooperate, and the breaking down of siloes within the complex agencies of health delivery. This is much easier to achieve in…a village. Three examples follow from my own personal experience of rural pediatric practice. During a period as the sole pediatrician serving a rural population of about 50,000, about a third of my patients were seen for behavior problems alone and a further quarter had physical illnesses complicated by behavior problems. It was essential and not too difficult to get to know teachers, guidance officers, principals and education bureaucrats operating in the local provincial area. This was crucial for effective management of ASD, which was also my task to diagnose. It was easier to have a personal relationship with the local child protection service and have influence in their decisions as the only pediatrician on their team. Health is notorious for siloes, but a common interest in preventing birthing disasters and ensuring optimal outcomes for mothers and babies led to a close working relationship with the local midwives. Considering the new knowledge regarding perinatal depression (

Section 3.1.3), if midwives were screening for maternal ASD [

144] a logical step forward would be to use local pediatric expertise to at least informally assess mothers. This would in turn improve the downstream pediatric care of the children. There is no reason why this could not extend to antenatal care. This would assist mothers during delivery with an autism friendly approach [

44,

144]. Even an informal diagnosis can be very therapeutic and would likely decrease the degree of depression. There is still likely to be a problem with allied health access ie psychology, speech therapy and occupational therapy, but there is evidence that telehealth is not inferior to face-to-face therapy [

145]. Counterintuitively non-acute care delivered in a rural setting can often be superior to that in larger centers due to better interdisciplinary communication, including across the pediatric/adult divide. In larger centers, from my experience as a clinician and medical executive participating in hospital design, the main problem is spatial isolation of busy clinicians. In University Teaching Hospitals a campus including Adult, Children’s and Women’s Hospitals maximizes interdisciplinary communication. Mental health facilities should also be on campus. Clinics and consulting rooms on site will mean clinical staff can participate in seminars, and be on site if there is an emergency with one of their patients. Staff lounges and dining facilities may be seen as elitist but are a very efficient way to share confidential information. They should be interdisciplinary but reserved for clinicians. The main seminar room needs to be central so staff can get there and back during their lunch break. For smaller district facilities the same design rules apply appropriate for scale. The common and pervasive root cause in any setting is inadequate interdisciplinary communication. It must be made as convenient as possible.

4.7. The Long View

There are too many stresses facing young people today [

146,

147]. World-wide or jurisdiction-wide stresses are beyond easy control, but managing the interacting effects of the common problem of comorbid ASD and stress-related MI is quite feasible at health service level with current techniques. Solving what is solvable boosts morale by showing we care. From Chapter 63 of the “Tao Te Ching” of Lao Tzu [

148]:

“Difficult problems are best solved when they are easy.

Great projects are best started when they are small.

The Master never takes on more than she can handle,

Which means she leaves nothing undone.”

4.7. Overview

This study has used novel methods to organize existing data to open a new window for clinical action in a difficult area of mental health affecting young people, and provides a new frame of reference. It has for the first time quantified the proportion of women with several mental health problems who are autistic. This impacts rates of diagnosis, methods of management and allocation of funding. Financial resources and mental health therapist numbers are quite inadequate, and appropriate attention will free up therapy time to deal with more patients and devote more time to reducing their intractable problems. A recurring theme among patients and their parents is that health professionals did not listen to them. The mother of one of my patients said: “

We have to learn to think aspie.” We all, especially if neurotypical, have to get better at listening, empathizing with the different mindset, and managing the problems but celebrating the benefits of neurodiversity [

149].

5. Limitations of the Study

The experience of adult women in struggling to get a diagnosis of ASD and the evidence for extensive female camouflage makes it certain that the prevalence must be significantly higher than generally reported. When Bayes’ theorem is used with reliable estimates of mental illness prevalence in diagnosed ASD populations, and when ASD has been explicitly sought in diagnosed MI populations, it turns out that there are quite a lot of corroborating data (

Section 3.3,

Table 3) for a prevalence of ~6%. However this needs to be independently confirmed.

Estimates of P(MI|ASD) are heterogeneous with diagnostic overshadowing. Estimates of P(MI) are also heterogeneous with differing values due to diagnostic variation and the prevalence being different at different ages. As a result values for P(ASD|MI) are indicative at this stage. However as seen in

Table 2, results by different methods, and with different secondary data values by different authors, do tend to correlate.

The Pareto analysis is novel. With an improvement in diagnostic rate of ASD and consequent more efficient management of the comorbid conditions there should be savings in overall patient populations, but this analysis is a first attempt at a method of quantification. Current estimates are novel and would be refined as more extensive secondary data become available. The strategy of the study is to shift the frame of reference of ASD comorbidity and it is very early days for costings.

6. Future Directions

Due to the underestimation of P(ASD) and the very recent appreciation of the deleterious effect of ASD on comorbid MI the level of risk has been seriously underestimated. It is therefore not surprising that knowledge of the degree of risk has not reached our adult colleagues. With a new appreciation of the clinical problem advances in many areas can be anticipated.

The value for P(ASD) looks fairly reliable. The qualitative reports on camouflaging suggest we are missing a considerable proportion of females. It is reassuring that the use of Bayes’ theorem with variables from a number of independent secondary data sources do give a fairly narrow range of results that far exceeds the generally quoted estimate of 1%. Two different methods of calculation agree, but the value needs further corroboration by independent sources.

Refinement of diagnostic criteria will help quantify prevalence estimates. It is possible that the problem of diagnostic overshadowing may be resolved by adopting a continuous model of mental health conditions as genetics suggests. This should simplify management of comorbidity if that model is seen as the norm. Treatments could be applied to the entire continuum, as is becoming commoner for ASD/ADHD.

Data allowing calculation of P(ASD|MI) for specific mental illnesses are sparse. As more values for P(MI|ASD) and P(MI), or P(MI|ASD)/P(MI|not ASD) become available they can be assessed by Bayes’ theorem. Future results are unlikely to obviate the need for routine assessment for ASD.

Recent rapid advances in knowledge about female autism should help break down the transition barrier from adolescents to adults.

More work is needed to continue to improve talking therapies in mental illness with comorbid ASD.

More examples of savings by managing comorbid ASD are needed. The Pareto method can be refined to quantify efficiency gains. Funding should follow quantitation of the risk of comorbid ASD in female mental health if management is clearly shown to work. Government tends to fund programs with evidence of success.

7. Conclusions

This study completes a sequence of:

Quantifying the strong clinical suspicion of bias in detecting female ASD [

4].

Finding the true value of female ASD prevalence implicit in that suspicion [

15].

Calculating the practical clinical outcomes of a new frame of reference for the relation of ASD and female mental illness. This has been the contribution of this paper with the following conclusions:

A median P(ASD) of 6.0 % has received further confirmation.

Female camouflage appears to begin at a very early age.

This prevalence of ASD in female mental illness is clinically significant at a population level and for individual diagnosis. It does seem likely that up to one in five women with a mental illness is autistic and this is not generally being managed.

ASD in this population must be diligently sought both prior to and after the transition to adult care.

The solution to facilitating this transition lies within the health system in terms of establishing the extent of the problem and transmitting the information. The overall risk in extent and severity of outcome of the ASD/MI comorbidities is much higher than currently understood.

The risk for comorbid depression and its consequences is of particular concern and should be urgently addressed. Intergenerational morbidity arises from both heredity and environment and timely diagnosis of girls and young women would be of high societal benefit.

Effective therapy is quite feasible. At the present time a lot of energy is being wasted on ineffective therapy due to the lack of an ASD diagnosis. That wasted energy can be redirected to effective modes of management with a consequent large positive gain in efficiency as well.

The method of finding high risk ASD patients has identified and quantified the drivers of the Pareto analysis, and the Pareto formulation has given an estimate of system gain.

The overall improvement in female mental health and prevention of the downstream and intergenerational effects of mental illness is likely to be substantial, but accurate estimation of system gains is at present in its infancy.

The key to effective diagnosis and therapy is listening, understanding and empathizing with neurodiverse individuals.

Conflict of Interest: The author declares no conflict of interest.

Funding

The research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The data pertinent to the study were abstracted from peer reviewed published articles referenced in the text. It is completely deidentified and there are no ethical issues.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Appendix A

Accuracy of the hazard ratio as a likelihood ratio in calculating P(ASD|MI).

The HR method has interesting properties. The HR is P(MI|ASD)/P(MI|not ASD). The numerator P(MI|ASD) is itself a ratio of the measured MI patients who are comorbid with the measured ASD. If the ratio is the same whatever the number of ASD patients found, ie P(MI|ASD) is constant, then the number of ASD patients identified does not matter. ASD presents earlier than MI (

Section 3.1.1) and by the time MI is reliably diagnosable there will be a sufficient base of ASD to form the denominator of P(MI|ASD). The HR denominator P(MI|not ASD) consists of the balance of the MI patients who are not comorbid with ASD. There are three MI groups ie those comorbid with ASD and measured as such, those comorbid with ASD which has not itself been measured, and those who are not associated with ASD. Since the hazard ratio is a ratio of the MI groups MI|ASD and MI|not ASD, any fractional error in MI measurement will cancel as long as it is fairly constant across the three groups. We do not actually need to know the true P(MI). Changes in the measured value of P(ASD) do affect the value of P(MI|ASD)/P(MI|not ASD). The value does not vary much over a wide range of the relationship of ASD and MI however, and generally underestimates HR by a small margin. The estimates of P(ASD|MI) are then conservative. We will now derive a formula to find P(ASD|MI) from the HR.

The Venn diagram

Figure 3 can be transformed to a Bayesian 2 x 2 table. The 2 x 2 table, or Carrollian Table, was invented by Charles Lutwidge Dodgson,

nom de plume Lewis Carroll, who was a mathematics don at Oxford University. He was a logician who introduced the 2 x 2 table as the

biliteral diagram in 1896 [

150].