Submitted:

12 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Smart-grid analysis in order to map and compare architectures, control layers, data flows, and interfaces between legacy assets and DERs (Distributed Energy Resources) to explain operating mechanisms and classical–renewable interactions.

- Vulnerability identification and assessment with the aim to build a risk taxonomy (technical, cyber, operational) and a quantitative scoring model to prioritize threats to safety and stability.

- Blackout-prevention methods to design proactive tools (forecasting, protection coordination, DER/DR Distributed Energy Resources/ Demand Response pre-positioning) and reactive schemes (FLISR, UFLS/UVLS - Underfrequency Load Shedding/ Undervoltage Load Shedding, microgrid islanding) to reduce major-outage risk.

- Resilience enhancement in order to develop models and strategies that increase absorptive, adaptive, and restorative capacity to ensure service continuity under extreme or unforeseen events.

- Energy sustainability promotion with the aim to embed low-carbon best practices (CVR/VVO - Conservation Voltage Reduction/ Volt/VAR Optimization, DR, storage orchestration) to cut losses and carbon intensity while optimizing consumption.

- Integrated conceptual framework for a multidisciplinary, SGAM-aligned framework uniting power-systems engineering, cybersecurity, and sustainability for end-to-end analysis.

- Vulnerability assessment methodology with measurable criteria and indicators, plus a reproducible scoring toolkit, for risk analysis specific to SG.

- Innovative blackout-prevention solutions using AI-driven forecasting and anomaly detection with automation (ADMS/DERMS - Distributed Energy Resources Management System) to prevent cascading failures and speed restoration.

- Resilience strategies are models for co-optimizing generation–storage–demand, orchestrating microgrids, and sequencing restoration to minimize EENS (Expected Energy Not Served) and recovery time.

- Energy-sustainability advances in order to emphasize actionable recommendations and policy–technology playbooks for integrating renewables and efficiency measures into routine grid operations.

2. State of the Art and Sector Landscape

2.1. International Landscape

- 1.

- Regulation and security frameworks

- EU publishes specific codes for cybersecurity in the electricity sector (Network Code on Cybersecurity) adopted in March 2024 and steps up enforcement of NIS2. ENISA provides maturity analyses (NIS360) for critical sectors. These impose requirements for risk assessment, vulnerability reporting and supply chain management [49];

- In North America NERC CIP standards (FERC-approved and evolving) remain the mandatory baseline for the Bulk Electric System. FERC continues to update/strengthen CIP (e.g., CIP-003-11 proposals in 2025) [50];

- UK applies NIS Regulations for downstream gas/electricity with Ofgem as co-competent authority and statutory guidance for Operators of Essential Services [51];

- Australia with SOCI/SLACIP regime expands mandatory risk-management and reporting obligations across critical infrastructure (incl. electricity) [52];

- Singapore implements Cybersecurity Act (amended 2024/2025) that sets obligations for Critical Information Infrastructure, including the energy sector [53];

- Global standards ecosystem relies on IEC 62351 series for power-system communications security and ISO/IEC 27019:2024 for energy-utility controls complement regulatory frameworks. IEC 62351-3:2023 stipulates how to provide CIA confidentiality, integrity availability, and message level authentication for protocols that make use of the TCP/IP protocol (OSI Transport Layer) where cyber-security is compulsory [54]. ISO/IEC 27019:2024 standard rules about information security controls for the energy utility industry [55].

- 2.

- Emerging technologies

- 3.

- Lessons from recent incidents

2.2. Romanian National Landscape

- 4.

- Policies and plans - Transelectrica company has included the development of SG elements in the RET Development Plan 2024–2033; large companies (such as Electrica etc.) are investing in monitoring and digitalization of networks. However, large-scale implementation of advanced functions (PMU, extended DMS automation, DER integration) by DSO/TSO is ongoing;

- 5.

- Vulnerability assessment capacity - existence of studies and activity reports by private/sectoral actors, but lack of frequent publications of independent audits and national resilience testing programs to cyber-attacks and extreme scenarios;

- 6.

- EU funding & programs - Romania can access EU funds for smart-grid modernization (included in operational programs) — opportunity to increase DSO/TSO capabilities;

- 7.

- Vulnerability assessment:

- Cyber vulnerabilities - compromised inputs (SCADA/RTU/IED), vulnerable firmware, supply chains, unencrypted telemetry, lack of segmentation of operational networks. ENISA and industry events recommend periodic assessments, OT-specific pen-testing and vulnerability management;

- Physical/operational vulnerabilities - loss of regulation capacity (inertia reduction due to high penetration of renewables), protection failures, lack of back-ups for critical communications. Recent studies show that climate change increases the risk of outages.

- 8.

- Blackout prevention techniques and practices:

- Advanced monitoring: PMU, dynamic state estimation, real-time anomaly detection and RT-NMS for automated actions;

- Systemic services and market design: preserving control capabilities (synchronous resources, fast reserve, balancing contracts), progressive disconnection rules;

- Distributed operation and microgrids: islanding/local control capability of DER + storage reduces the risk of extended power outage;

- Restoration plans and exercises: scale simulations, coordinated exercises TSO-DSO-Suppliers-Authorities. ENTSO-E and regional bodies promote post-incident investigations and peer learning.

- 9.

- Resilience measures (medium-long term):

- Segmentation and redundancy of communications (separate fiber + LTE/5G channels); encryption & strong authentication for IED/SCADA;

- Operational flexibility: integration of batteries and DER with VPP controllers/aggregators for rapid response;

- Proactive vulnerability management: software/hardware inventory, patch management and transparent reporting (according to NIS2 / network code);

- Climate capabilities: design with extreme event scenarios (maximum loads, temperatures) and infrastructure modernization for overloads.

- 10.

- Recent lessons and trends:

- Major blackouts can start from multi-factor technical combinations (voltage, protections, generation loss). There are not always cyber-attacks. The response is strengthening physical monitoring and cybersecurity;

- European regulations are evolving rapidly, and energy entities must integrate NIS2 requirements and sector codes into procedures and contracts.

- 11.

- Practical recommendations for Romania (priority):

- National vulnerability assessment program (OT/IT audit, pen-testing, soft/hardware inventory) — coordinated by TSO + DSO + Authority (ANRE/Transelectrica);

- Rapid implementation of PMU/State Estimation at critical nodes and data integration at TSO-DSO level for early detection;

- National blackout exercises (tabletop combined with practical exercises) with scenarios inspired by the Iberian case and other recent events. These include telecommunications and critical services;

- EU program funding plan for DMS, SCADA and resilient communications modernization (to be used lines from PNRR/POIM/other);

- Creation as well as participation in regional vulnerability information exchange mechanisms in order to keep sharing threat intelligence updated according to ENISA.

2.3. Academic Scientists

- • Prof. Massoud Amin – University of Minnesota. Recognized expert in security, resilience and self-healing for SG;

- • Prof. Enrico Zio – Politecnico di Milano / ETH / research in reliability, vulnerability and uncertainties for energy systems (smart grid vulnerability studies);

- • Dr. Daogui Tang – research on “false pricing” / social-network-based attacks on smart grid demand-response programs;

- • Prof. Yi-Ping (Yiping) Fang – CentraleSupélec / Université Paris-Saclay; work on computational models for risk, vulnerability and resilience analysis of critical infrastructures (including SG);

- • Prof. José E. Ramírez-Márquez – Stevens Institute of Technology; specialist in systems resilience and quantitative assessments of infrastructure vulnerability/resilience;

- • Prof. Dan Popescu – Politehnica University of Bucharest (Automatics / Systems) — involved in relevant fields for measurement, control and smart-grid applications;

- • Prof. Sorin-D. Grigorescu – research in electrical engineering, power quality monitoring and applications for SG;

- • Prof. Ciprian Dobre – Politehnica University of Bucharest (academic profile/activity; IT and systems fields) — relevant contributions to IT/telecom components of smart-grid;

- • Dr. Radu Plămănescu – Politehnica University of Bucharest (measurements and data platforms for SG) — works and projects related to practical applications in grids.

3. Vulnerability Assessment

| Vulnerability identified |

Identification of the generated source (Dysfunction, deficiency, non-conformity) |

Causal analysis |

| Poor management of the transmission operator activity (operation, maintenance and development) of energy installations related to the Electricity Transmission Network | Dysfunction | • lack, precariousness or non-compliance with operating procedures; • lack, precariousness or non-compliance with maintenance procedures; • lack, precariousness or non-compliance with development procedures. |

| Causes | Effects |

| • short circuits of power equipment; • loads of some overhead power lines; • loads of some power equipment; • poor condition of power equipment; • lack of investment in power stations; • non-functioning of system automation within power groups; • lack of overhauls of power equipment; • lack of upgrading of power stations; • incorrect configuration of power stations; • lack of specialized and/or trained operational personnel; • lack of communication or poor communication with DET – Territorial Power Dispatcher or DEN – National Power Dispatcher; • unspecialized DET or DEN personnel during a crisis; • lack of work procedures in power stations during a crisis; • lack / non-compliance / ignorance of national / European procedures in case of serious damage (black out); • lack of training in the field of Risk Management; • failure to close the 400 kV ring of Romania – becomes a vulnerability of the SEN – National Energy System; • occurrence of electrical discharges; • lack or incorrect functioning of lightning rod installations; • incorrect functioning of arresters; • failure to comply with fire safety regulations; • failure to comply with occupational health and safety regulations; • failure to use PPE – Personal Protective Equipment; • poor condition of energy equipment; • lack of overhauls of energy equipment; • use of non-compliant energy subassemblies; • lack of investments; • failure to modernize electrical substations; • lack of specialized and/or trained maintenance personnel; • wrong maneuvers performed by operational personnel in substations. |

• stopping the energy market between Romania and the EU (ENTSO-E); • stopping the energy market between Romania and Serbia, Ukraine, the Republic of Moldova; • failure to supply electricity to neighboring energy systems and the EU; • failure to supply electricity to important consumers and to the main power lines within the SEN; • possibility of a local, regional or national blackout. • work accidents caused by an explosion that may generate fire (individual or collective) fatal or with incapacity for work; • work accidents caused by a fire (unitary or collective) fatal or with incapacity for work; • propagation of the explosion (fire) to other energy equipment in the area; • propagation of the explosion (fire) to other external objectives (forests, houses, blocks of flats, factories, etc.); • propagation of the fire to other energy equipment in the area; • spread of the fire to other external objects (forests, houses, blocks of flats, factories, etc.); • untimely disconnection of the respective equipment; • material damage resulting from the lack of electricity; • major material damage resulting from the interdependence of other consumers |

| Situational Severity Analysis | Level | |

| a) Failure to close Romania's 400 kV ring: • lack of investment (failure to upgrade power stations, overhead power lines and new energy objectives); • impregnability of the political system; • possibility of a zonal, regional or national blackout, generating the shutdown of the electricity market between Romania and the EU; • economic insecurity generating national insecurity; b) Specialization degree and periodic training of personnel responsible for restoring the electricity supply process: • operational personnel; • maintenance personnel; • security personnel. c) Location of the power station (European critical infrastructure) from the point of view of safety in supplying electricity to consumers: • zonal, regional and national consumers; • national interconnection; • interconnection with neighboring energy systems. d) Degree of specialization and training of fire response personnel; e) Degree of specialization and periodic training of operational personnel responsible for restoring the electricity supply process; f) Equipping the power station with fire extinguishing means and equipment; g) Equipping the operational personnel with individual means and protective equipment; h) Existence of work procedures in the field of security for the power station: • risk management; • crisis management; • emergency management; • occupational health and safety management. i) State of equipment and technological installations related to the electricity transmission process (lack of investment): • protection equipment against atmospheric overvoltages (lightning rods, arresters); • transformation equipment (transformers, autotransformers); • switching and protection equipment (circuit breakers, disconnectors); • insulators, measuring transformers (voltage and current), etc.; • technical and human resilience: • partial or total technical possibility of returning to the initial state; • partial or total human possibility of returning to the initial state. |

1. Very low | |

| 2. Low | ||

| 3. Medium | ||

| 4. High | ||

| X | 5. Very high | |

| Level | Severity | |

| 1. Very low | The event causes minor disruption to business operations, with no material damage | |

| 2. Low | The event causes minor material damage and limited disruption to business operations | |

| 3. Medium | Injuries to personnel, and/or some loss of equipment, utilities, and delays in service provision. | |

| 4. High | Serious injuries to personnel, significant loss of equipment, facilities, and delays and/or interruption of service provision. | |

| X | 5. Very high | The consequences are catastrophic resulting in fatalities and serious injuries to personnel, major loss of equipment, facilities, and services, and interruption of service provision. |

| Impact Analysis | Level | ||

| Potential deaths (persons) | X | 1. Very low | 0 – 5 persons |

| 2. Low | 6 – 10 pers. | ||

| 3. Medium | 11 – 15 pers. | ||

| 4. High | 16 – 20 pers. | ||

| 5. Very high | > 21 pers. | ||

| Potential injured persons (persons) | X | 1. Very low | 0 – 20 pers. |

| 2. Low | 21 – 40 pers. | ||

| 3. Medium | 41 – 60 pers. | ||

| 4. High | 61 – 80 pers. | ||

| 5. Very high | > 81 pers. | ||

| Potential damage or deterioration of on-site infrastructures providing the main utilities: electricity, communications, drinking water, natural gas (damages) | 1. Very low | Temporary damage | |

| 2. Low | Temporary damage | ||

| 3. Medium | Average damage | ||

| 4. High | High damage | ||

| X | 5. Very high | Very high damage | |

| Potential damage or deterioration of the material assets of those served by the national critical infrastructure in question: public, commercial, private (return on invested capital) | 1. Very low | 0 – 10% of VCI | |

| 2. Low | 11 – 20% of VCI | ||

| 3. Medium | 21 – 30% of VCI | ||

| 4. High | 31 – 40% of VCI | ||

| X | 5. Very high | over 41% of VCI | |

| Potential damage or deterioration of the environment (%) | 1. Very low | 0 – 20% | |

| 2. Low | 21 – 40% | ||

| X | 3. Medium | 41 – 60% | |

| 4. High | 61 – 80% | ||

| 5. Very high | over 81% | ||

| Potential social impacts (population confidence) | 1. Very low | 0 – 10% din ÎP | |

| 2. Low | 11 – 20% of ÎP | ||

| X | 3. Medium | 21 – 30% of ÎP | |

| 4. High | 31 – 40% of ÎP | ||

| 5. Very high | peste 41% of ÎP | ||

| Nivel | Impact | |

| 1. Very low | The event causes minor disruption to business operations, with no material damage | |

| 2. Low | The event causes minor material damage and limited disruption to business operations | |

| 3. Medium | Injuries to personnel, and/or some loss of equipment, utilities, and delays in service provision. | |

| 4. High | Serious injuries to personnel, significant loss of equipment, facilities, and delays and/or interruption of service provision. | |

| X | 5. Very high | The consequences are catastrophic resulting in fatalities and serious injuries to personnel, major loss of equipment, facilities, and services, and interruption of service provision. |

| Interdependencies Analysis | Infrastructure or critical systems |

|

|

| Vulnerability | Recomandations proposed |

| Failure to close Romania's 400 kV ring |

|

| The degree of specialization and periodic training of operational personnel responsible for restoring the electricity supply process |

|

| The degree of specialization and training of fire response personnel |

|

| Equipping the power station with fire-fighting means and equipment |

|

| The state of technological equipment and installations related to the electricity transmission process (lack of investment) |

|

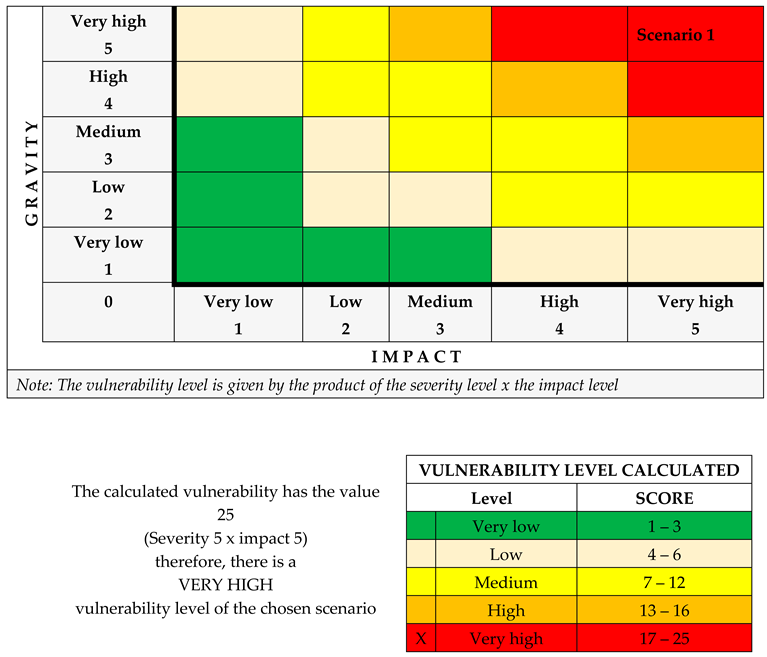

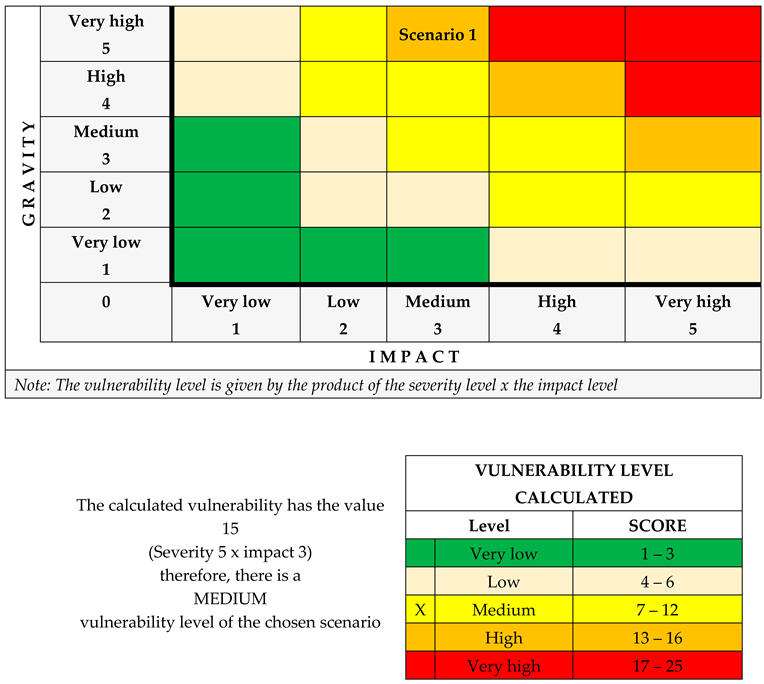

| Vulnerability | Identified | After the proposed recommendations | ||

| a) Failure to close the 400 kV ring of Romania; b) Degree of specialization and periodic training of operational personnel responsible for restoring the electricity supply process; c) Degree of specialization and training of fire response personnel; d) Degree of specialization and periodic training of operational personnel responsible for restoring the electricity supply process; e) Equipping the power station with fire-fighting means and equipment; f) Location of the power station (European critical infrastructure) in terms of safety in supplying consumers with electricity; g) Equipping the operational personnel with individual means and protective equipment; h) Existence of work procedures in the field of security for the power station: i) State of equipment and technological installations related to the electricity transport process (lack of investment); j) Technical and human resilience. |

1. Very low | 1. Very low | ||

| 2. Low | 2. Low | |||

| 3. Medium | X | 3. Medium | ||

| 4. High | 4. High | |||

| X | 5. Very high | 1. Very high | ||

4. Blackout Prevention, Resilience Assessment and Quantification

4.1. Blackout Prevention

- Infrastructure modernization by replace the power lines (overhead, underground or submarine) of old and obsolete (auto)transformers and distribution equipment (poor and/or non-compliant condition) to reduce the risk of failure;

- Automation and protections by implement novel SCADA systems and automatic protections that can quickly isolate the affected areas, without interrupting the entire network;

- Reserve capacities by maintain plants on standby (hydro, gas, large batteries) that can be started quickly when needed;

- Diversification of energy sources using a smart and reliable balanced integration of renewable sources with storage (batteries, hydro-pumping) and maintaining stable capacities (nuclear, hydro, gas);

- International interconnections allowing connecting to the electricity networks of other countries for mutual support in case of imbalance;

- Testing and exercises including regular simulations for major breakdown scenarios and clear restart procedures (“black start”).

- Backup generators to maintain critical activity;

- Consumption management (demand response) to reduce or shift consumption during peak hours;

- Protection equipment (UPS, stabilizers) to avoid failure of equipment sensitive to fluctuations.

- Reducing consumption during peak hours (morning/evening, summer/winter);

- Energy-efficient equipment and rational use of large household appliances;

- Alternative sources as portable batteries, solar panels with storage, small generators for emergency situations;

- Awareness as a main tool for an educated population about how to react and how to temporarily reduce consumption in critical situations.

| Scenario | Cause of production and propagation |

| Black-out | 1. Faults in the Electric Transmission Network: |

| |

| |

| |

| 2. Imbalance between production and consumption: | |

| |

| 3. Power plant faults: | |

| |

| 4. Poor coordination in the National Energy Dispatching Office or territorial dispatching offices: | |

| |

| 5. Problems in protection and automation systems: | |

| |

| 6. Cyber-attacks or computer errors | |

| |

| 7. Natural disasters or catastrophes: | |

|

4.2. Assessing and Quantifying the Resilience of SG

| Factor generator – black-out | Resilience |

1. Faults in the Electric Transmission Network:

|

|

2. Imbalance between production and consumption:

| |

| 3. Power plant failures: | |

| |

| |

| 4. Poor coordination in the National Energy Dispatching Office or territorial dispatching offices: | |

| |

| |

| 5. Problems in protection and automation systems: | |

| • Protections that act incorrectly or with a delay, which can propagate a failure; | |

| * depending on the blackout generator factor (type of fault), resilience can last less than 5 hours or more than 25 hours. | |

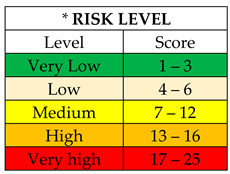

| Black-out type | Propagation area | Risk level* | Resilience |

| 1. Local blackout | Apartment/home | 1 | 5 – 20 minutes |

| 2. Zonal blackout | Neighborhood | 4 | 20 – 40 minutes |

| 3. Rural/communal black-out | Village/commune | 6 | 40 – 60 minutes |

| 4. Urban blackout | City/district | 12 | 1 – 2 hours |

| 5. Regional blackout | Region | 16 | 2 – 5 hours |

| 6. National blackout | Whole country | 5 | 5 – 25 hours |

| 7. Continental blackout | Continent | 5 | 10 – 50 hours |

| 8. Intercontinental blackout | Continents | 5 | 20 – 100 hours |

|

The resilience (exposure time) was approximated by the authors following statistics of fault times (technical incidents) within the SEN Electricity Transmission Network. | ||

| Key elements of national resilience | Impact on national security | Importance on national security |

| 1. Institutional capacity: Functionality and robustness of government, public administration, army, police, etc.; Inter-institutional coordination in emergency situations. |

1. Very low | Maintains the functioning of state and societal mechanisms and institutions under stress |

| 2. Low | ||

| 3. Medium | ||

| 4. High | ||

| 5. Very High | ||

| 2. Critical infrastructure: Safety and functioning of transport, energy, water, telecommunications networks; Continuity plans in case of major breakdowns. |

1. Very low | Provides essential facilities for the population and reduces the negative impact of external or internal shocks |

| 2. Low | ||

| 3. Medium | ||

| 4. High | ||

| 5. Very High | ||

| 3. Crisis response: Early warning and rapid response systems; National disaster and pandemic response plans. |

1. Very low | Increases the capacity for rapid and effective recovery after a crisis |

| 2. Low | ||

| 3. Medium | ||

| 4. High | ||

| 5. Very High | ||

| 4. Economy and finance: Economic recovery capacity; Strategic reserves and fiscal stability. |

1. Very low | Increases the capacity for economic recovery after a crisis |

| 2. Low | ||

| 3. Medium | ||

| 4. High | ||

| 5. Very High | ||

| 5. Societal dimension: Social cohesion, trust in institutions, civic education; Resistance to disinformation and propaganda. |

1. Very low | Strengthens the security and societal stability of the population |

| 2. Low | ||

| 3. Medium | ||

| 4. High | ||

| 5. Very High | ||

| 6. Security and defence dimension: Military capacity, reservist mobilization, NATO/EU cooperation; Border protection and cybersecurity. |

1. Very low | Provides essential military facilities to the army and national safety and security structures |

| 2. Low | ||

| 3. Medium | ||

| 4. High | ||

| 5. Very High | ||

| 7. Sustainability and climate change: Adaptation to medium-risk, natural resource management; Green energy transition strategies. |

1. Very low | Provides essential resources for the population and reduces the negative impact of external or internal shocks |

| 2. Low | ||

| 3. Medium | ||

| 4. High | ||

| 5. Very High | ||

| 8. Energy, food and drinking water: Continuous access to energy: natural gas, oil, fuels (diesel, gasoline, kerosene, etc.), coal, uranium, etc.; Continuous access to food; Continuous access to drinking water. |

1. Very low | Provides essential resources for the population and reduces the negative impact of external or internal shocks |

| 2. Low | ||

| 3. Medium | ||

| 4. High | ||

| 5. Very High |

5. Strategies to Increase the Resilience ff SG and Promote Energy Sustainability Practices

5.1. Increasing the Resilience of SG

- Modernization of transmission and distribution lines with weatherproof cables;

- Network redundancy (the possibility of rerouting energy in the event of failures);

- Distributed storage through batteries, hydrogen or other technologies.

- Implementation of IoT sensors and smart meters for rapid anomaly detection;

- Use of artificial intelligence for consumption forecasts and failure prevention;

- Creation of control centers with self-healing algorithms (self-healing grids).

- Implementation of cybersecurity standards to prevent attacks;

- Segmentation and encryption of network communications;

- Stress tests and periodic attack simulations.

- Decentralized production from renewable sources (solar panels, local wind);

- Independent microgrids that can operate in isolation in case of crisis;

- Prosumer models, where consumers are also energy producers.

5.2. Promoting Energy Sustainability

| Vulnerabilities of the Electric Transmission Network | Proposed recommendations with a stability, security and sustainability effect |

| Non-closure of Romania's 400 kV ring | a) major investments in national and European critical infrastructure; b) predictability (security) of the political system; c) accessing European funds regarding the security of European critical infrastructures. |

| Degree of specialization and periodic training of operational personnel with duties of restoring the electricity supply process; | d) training and advanced training courses for operational, maintenance and security personnel e) analysis of events, incidents, etc.; f) control of installations on the operating line and carrying out preventive maintenance. |

| Degree of specialization and training of fire intervention personnel | g) training and improvement courses in the field of emergency situations - PSI; h) simulations of interventions (very short time) in case of fires |

| Equipping the power station with fire extinguishing means and equipment | i) equipping with individual fire extinguishing means and equipment |

| State of technological equipment and installations related to the electricity transmission process (lack of investments) | j) major investments in high-performance equipment |

- Increasing the share of solar, wind, geothermal and hydro energy;

- Fiscal incentives and support schemes for investments in renewables;

- Development of green energy storage capacities.

- Implementation of smart buildings with efficient lighting and air conditioning systems;

- Modernization of industrial equipment and reduction of losses in the distribution chain;

- Education and awareness programs for consumers.

- Introduction of dynamic tariffs to encourage responsible consumption;

- Efficiency standards for electrical appliances and vehicles;

- Integration of climate neutrality objectives into national strategies.

- Peer-to-peer trading platforms for locally produced energy;

- Community renewable energy projects;

- Supporting research in emerging technologies (SMR, long-term storage, hybrid SG).

6. Results

References

- Campana, P.; Censi, R.; Ruggieri, R.; Amendola, C. SG and Sustainability: The Impact of Digital Technologies on the Energy Transition. Energies 2025, 18, 2149. [CrossRef]

- Kiasari, M.; Ghaffari, M.; Aly, H.H. A Comprehensive Review of the Current Status of Smart Grid Technologies for Renewable Energies Integration and Future Trends: The Role of Machine Learning and Energy Storage Systems. Energies 2024, 17, 4128. [CrossRef]

- Faria, P.; Vale, Z. Demand Response in SG. Energies 2023, 16, 863. [CrossRef]

- Koukouvinos, K.G.; Koukouvinos, G.K.; Chalkiadakis, P.; Kaminaris, S.D.; Orfanos, V.A.; Rimpas, D. Evaluating the Performance of Smart Meters: Insights into Energy Management, Dynamic Pricing and Consumer Behavior. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 960. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, S.; Dener, M. Security with Wireless Sensor Networks in SG: A Review. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1295. [CrossRef]

- Dokku, N.S.; Raj, R.D.A.; Bodapati, S.K.; Pallakonda, A.; Reddy, Y.R.M.; Prakasha, K.K. Resilient Cybersecurity in Smart Grid ICS Communication Using BLAKE3-Driven Dynamic Key Rotation and Intrusion Detection. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 32754. [CrossRef]

- Ejuh Che, E.; Roland Abeng, K.; Iweh, C.D.; Tsekouras, G.J.; Fopah-Lele, A. The Impact of Integrating Variable Renewable Energy Sources into Grid-Connected Power Systems: Challenges, Mitigation Strategies, and Prospects. Energies 2025, 18, 689. [CrossRef]

- Riurean, S.; Fîță, N.-D.; Păsculescu, D.; Slușariuc, R. Securing Photovoltaic Systems as Critical Infrastructure: A Multi-Layered Assessment of Risk, Safety, and Cybersecurity. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4397. [CrossRef]

- Yaacoub, J.P.A.; Noura, H.N.; Salman, O.; Chahine, K. Toward Secure Smart Grid Systems: Risks, Threats, Challenges, and Future Directions. Future Internet 2025, 17, 318. [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, D.; Riurean, S. Cyber-Security Attacks, Prevention and Malware Detection Application, December 2022, Journal of Digital Science 4(2):3-19. [CrossRef]

- Dorji, S.; Stonier, A.A.; Peter, G.; Kuppusamy, R.; Teekaraman, Y. An Extensive Critique on Smart Grid Technologies: Recent Advancements, Key Challenges, and Future Directions. Technologies 2023, 11, 81. [CrossRef]

- Boeding, M.; Scalise, P.; Hempel, M.; Sharif, H.; Lopez, J., Jr. Toward Wireless Smart Grid Communications: An Evaluation of Protocol Latencies in an Open-Source 5G Testbed. Energies 2024, 17, 373. [CrossRef]

- Riurean, S.M., Leba, M., Ionica, A.C. (2021). Conventional and Advanced Technologies for Wireless Transmission in Underground Mine. In: Application of Visible Light Wireless Communication in Underground Mine. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Ojo, K.E.; Saha, A.K.; Srivastava, V.M. Review of Advances in Renewable Energy-Based Microgrid Systems: Control Strategies, Emerging Trends, and Future Possibilities. Energies 2025, 18, 3704. [CrossRef]

- Chatuanramtharnghaka, B.; Deb, S.; Singh, K.R.; Ustun, T.S.; Kalam, A. Reviewing Demand Response for Energy Management with Consideration of Renewable Energy Sources and Electric Vehicles. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 412. [CrossRef]

- Riurean, S., Rus, C. (2025). Optical Wireless Battery Management System for Enhanced Performance and Safety. In: Antipova, T. (eds) Digital Technology Platforms and Deployment. Information Systems Engineering and Management, vol 36. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Tang, Z.; Si, C.; Bian, J.; Mu, C. A Review of Smart Grid Evolution and Reinforcement Learning: Applications, Challenges and Future Directions. Energies 2025, 18, 1837. [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y. Sustainable Development Through Energy Transition: The Role of Natural Resources and Gross Fixed Capital in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 83. [CrossRef]

- Chrysikopoulos, S.K.; Chountalas, P.T.; Georgakellos, D.A.; Lagodimos, A.G. Decarbonization in the Oil and Gas Sector: The Role of Power Purchase Agreements and Renewable Energy Certificates. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6339. [CrossRef]

- Berrich, O. The Paris Agreement’s Contribution to Renewable Energy Diffusion in Africa and Europe: A Panel Data Analysis. Energies 2024, 17, 4238. [CrossRef]

- Niște, D.-F.; Bobo, C.; Jilavu, A.; Badea, A.-F.; Bogdan, C. Electricity Losses in Focus: Detection and Reduction Strategies—State of the Art. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 3517. [CrossRef]

- Luty, L.; Zioło, M.; Knapik, W.; Bąk, I.; Kukuła, K. Energy Security in Light of Sustainable Development Goals. Energies 2023, 16, 1390. [CrossRef]

- Wojtaszek, H. Energy Transition 2024–2025: New Demand Vectors, Technology Oversupply, and Shrinking Net-Zero 2050 Premium. Energies 2025, 18, 4441. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; et al. Renewable energy quality trilemma and coincident wind–solar droughts. Communications Earth & Environment 2024. [CrossRef]

- Staadecker, M.; et al. The value of long-duration energy storage under various scenarios. Nature Communications 2024. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; et al. An Overview of Power System Flexibility: High Renewable Energy Penetration. Energies 2024, 17, 6393. [CrossRef]

- Monaco, R.; et al. Digitalization of power distribution grids: Barrier analysis, ranking and implications. Energy Policy 2024, 114083. [CrossRef]

- Aghahadi, M.; et al. Digitalization Processes in Distribution Grids: A Comprehensive Review of Strategies and Challenges. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 4528. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, F.B.; et al. A comprehensive review of the dynamic applications, benefits and impediments of digital-twin technology in the energy sector. Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; et al. A globally interconnected solar–wind system can meet future electricity demand. Nature Communications 2025. [CrossRef]

- Adeyinka, A.M.; et al. Advancements in hybrid energy storage systems for grid-connected renewable integration: a review. Sustainable Energy Research 2024, 9, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Naghibi, A.F.; et al. Capabilities of battery and compressed-air storage for flexibility regulation in multi-microgrids. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 24856. [CrossRef]

- Štogl, O.; et al. Electric vehicles as facilitators of grid stability and flexibility: opportunities and challenges. WIREs Energy and Environment 2024, e536. [CrossRef]

- Gremes, M.F.; et al. NTL-Unet: A satellite-based approach for non-technical loss detection in electricity distribution using Sentinel-2 imagery and ML. Sensors 2024, 24, 4924. [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.; Dabbaghjamanesh, M.; Goswami, S.; Arefifar, S.A. SG and Renewable Energy Systems: Perspectives and Grid Integration Challenges. Energy Strategy Reviews 2024, 51, 101299. [CrossRef]

- Athanasiadis, C.L.; Papadopoulos, T.A.; Kryonidis, G.C.; Doukas, D.I. A Review of Distribution Network Applications Based on Smart Meter Data Analytics. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 191, 114151. [CrossRef]

- Pourfarzin, S.; Ghafouri, M.; Askarzadeh, A. Technoeconomic Conservation Voltage Reduction–Based Demand Response for Distributed Power Networks. International Transactions on Electrical Energy Systems 2024, 2024, 9752955. [CrossRef]

- Cabot, P.; Girbau-Labagueria, J.; Olivella-Rosell, P.; Sumper, A. Demand-Side Flexibility in Liberalised Power Markets: From Technical Capabilities to Market Products and Standardised Services. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 187, 114694. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, C.; Hirth, L.; Schlecht, I. Grid Tariff Design and Peak Demand Shaving: A Comparative Analysis between Germany and the United States. Energy Policy 2025, 192, 114777. [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Wang, X.; Lin, H.; Wang, F.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, T. Demand Response with Pricing Schemes and Consumers with Varying Preferences: A Comparative Analysis. Applied Energy 2025, 375, 123724. [CrossRef]

- Rouhani, Z.; Fereidunian, A.; Saderi, N. A Critical Review of Cybersecurity in Intelligent Renewable-Dominated Microgrids. Energy 2024, 293, 130409. [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.; Sarker, A.; Abhi, S.H. Potential Smart Grid Vulnerabilities to Cyber Attacks: Current Threats and Existing Mitigation Strategies. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37980. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yao, Y.; Ding, F. Integrated Framework of Multisource Data Fusion for Outage Location in Looped Distribution Systems. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2025. [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.F.W.; Rodrigues, K.A.; Ribeiro, P.F.; Oleskovicz, M.; Kagan, N.; Chad, D.; Cardoso, da Silva, D.C.; et al. Islanding Detection Methods for Distributed Generation in Electric Power Systems: A Comprehensive Assessment. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 16170. [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.A.; Gouveia, H.T.V.; Ferreira, A.A.; de Lima Neta, R.M.; et al. Detection of Non-Technical Losses on a Smart Distribution Grid Based on Artificial Intelligence Models. Energies 2024, 17, 1729. [CrossRef]

- Janev, V.; Berbakov, L.; Tomašević, N.; Sotoca, J.M.-B.; Lujan, S. Validating the Smart Grid Architecture Model for Sustainable Energy Community Implementation: Challenges, Solutions, and Lessons Learned. Energies 2025, 18, 641. [CrossRef]

- Basilico, P.; Biancardi, A.; D’Adamo, I.; Gastaldi, M.; Yigitcanlar, T. Renewable Energy Communities for Sustainable Cities: Economic Insights into Subsidies, Market Dynamics and Benefits Distribution. Applied Energy 2025, 389, 125752. [CrossRef]

- Official Journal of the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=OJ%3AL_202401366 (accessed on 01.10.2025).

- European Union Eur-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2024/1366/oj/eng (accessed on 01.10.2025).

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Available online: https://www.ferc.gov/industries-data/electric/industry-activities/cyber-and-grid-security (accessed on 01.10.2025).

- Ofgem. Available online: https://www.ofgem.gov.uk/energy-regulation/technology-and-innovation/cybersecurity. (accessed on 01.10.2025).

- Australian Government Department of Home Affairs. Available online: https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-publications/submissions-and-discussion-papers/slacip-bill-2022 (accessed on 01.10.2025).

- Cybersecurity Agency of Singapore. Available online: https://www.csa.gov.sg/legislation/cybersecurity-act (accessed on 01.10.2025).

- International Electrochemical Commission. Available online: https://webstore.iec.ch/en/publication/68410 (accessed on 01.10.2025).

- ISO. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/85056.html (accessed on 01.10.2025).

- IEEE Standard Association. Available online: https://standards.ieee.org/ieee/C37.118.1/4902.

- Electrifyng Europe. Available online: https://www.entsoe.eu/publications/blackout/28-april-2025-iberian-blackout. (accessed on 01.10.2025).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Guidelines for Smart Grid Cybersecurity, NISTIR 7628, Rev. 1; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2014. Available online: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ir/2014/nist.ir.7628r1.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). IEC 62443 3 3:2013—System Security Requirements and Security Levels; IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. Available online: https://webstore.iec.ch/en/publication/7033 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- International Society of Automation (ISA). ISA/IEC 62443 Series of Standards—Overview. Available online: https://www.isa.org/standards-and-publications/isa-standards/isa-iec-62443-series-of-standards (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC). CIP 002 5.1a—BES Cyber System Categorization; NERC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.nerc.com/pa/stand/reliability%20standards/CIP-002-5.1a.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC). CIP 002 6—BES Cyber System Categorization; NERC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.nerc.com/pa/Stand/Reliability%20Standards/CIP-002-6.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC). CIP 013 2—Supply Chain Risk Management; NERC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.nerc.com/pa/Stand/Reliability%20Standards/CIP-013-2.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/2196 of 24 November 2017 establishing a network code on electricity emergency and restoration. Off. J. Eur. Union 2017, L 312, 54–93. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2017/2196/oj/eng (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- ENTSO E. Guidelines and Rules for Defence Plans in the Continental Europe Synchronous Area; ENTSO E: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. Available online: https://www.entsoe.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/_library/publications/entsoe/RG_SOC_CE/RG_CE_ENTSO-E_Defence_Plan_final_2011_public.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- ENTSO E. System Defence Plan (v8, Draft); ENTSO E: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. Available online: https://www.entsoe.eu/Documents/SOC%20documents/Regional_Groups_Continental_Europe/2022/220215_RGCE_TOP_03.2_D.1_System%20Defence%20Plan_v8_final.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- ENTSO E. Operation Handbook—Policy 5 (Emergency Operations); ENTSO E: Brussels, Belgium. Available online: https://eepublicdownloads.entsoe.eu/clean-documents/pre2015/publications/entsoe/Operation_Handbook/Policy_5_final.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. Available online: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/CSWP/NIST.CSWP.29.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). CSF 2.0 Resource & Overview Guide (SP 1299); NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. Available online: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.1299.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Buldyrev, S.V.; Parshani, R.; Paul, G.; Stanley, H.E.; Havlin, S. Catastrophic cascade of failures in interdependent networks. Nature 2010, 464, 1025–1028. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ning, P.; Reiter, M.K. False Data Injection Attacks against State Estimation in Electric Power Grids. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS '09), Chicago, IL, USA, 9–13 November 2009; pp. 21–32. Available online: https://reitermk.github.io/papers/2009/CCS1.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- ENTSO E. Continental Europe Synchronous Area Separation on 08 January 2021—Final Report; ENTSO E: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. Available online: https://www.entsoe.eu/Documents/SOC%20documents/SOC%20Reports/Continental%20Europe%20Synchronous%20Area%20Separation%20on%2008%20January%202021%20-%20Main%20Report_updated.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- ENTSO E. Executive Summary: Continental Europe Separation on 08 January 2021; ENTSO E: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. Available online: https://www.entsoe.eu/Documents/SOC%20documents/SOC%20Reports/Continental_Europe_Synchronous_Area_Separation_on_08_January_2021_-_Executive_Summary_updated.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Dan Codruț Petrilean, Nicolae Daniel Fîță, Gabriel Dragoș Vasilescu, Mila Ilieva-Obretenova, Dorin Tataru, Emanuel Alin Cruceru, Ciprian Ionuț Mateiu, Aurelian Nicola, Doru-Costin Darabont, Alin-Marian Cazac, Sustainability Management Through the Assessment of Instability and Insecurity Risk Scenarios in Romania’s Energy Critical Infrastructures, MDPI – Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, Sustainability 17, no. 7: 2932. (Q2), 2025. [CrossRef]

- Fita Nicolae Daniel, Ilie Utu, Marius Daniel Marcu, Dragos Pasculescu, Ilieva Obretenova Mila, Florin Gabriel Popescu, Teodora Lazar, Adrian Mihai Schiopu, Florin Muresan-Grecu, and Emanuel Alin Cruceru, Global Energy Crisis and the Risk of Blackout: Interdisciplinary Analysis and Perspectives on Energy Infrastructure and Security, MDPI – Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, Energies 18, no. 16: 4244. 2025. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).