1. Introduction

The global availability of freshwater has declined sharply due to rapid population growth, industrialization, and increasing drought frequency. Given that freshwater constitutes a mere 3% of the planet's water resources [

1], and the WHO reports that one-fifth of the global population resides in areas of physical water scarcity [

2], significant attention has turned to alternative water sources [

3]. Among these, desalination technology, the process of purifying saline or brackish water, stands as an essential and effective method for producing potable water and mitigating worldwide water shortages [

4,

5,

6]. Global reliance on desalination for drinking water is growing rapidly. While it currently provides about 1% of the world's potable water [

7], this share is increasing every year. Investment is following this trend, with a projected

$10 billion set to add 5.7 million cubic meters of new daily capacity within five years; total global capacity is expected to double by 2030. From 18,000 plants in 2015 producing 86.55 million m³/day, the number of facilities grew to nearly 21,000 by 2022 [

8]. Today, these plants produce roughly 35 billion cubic meters of freshwater annually [

9]. While nearly half of all capacity (44%) is concentrated in the Middle East and North Africa, the fastest future growth is anticipated in Asia, the United States, and Latin America.

The expansion of desalination in the EU, primarily in the Mediterranean, is hampered by major economic and environmental obstacles. The most significant barriers are the exorbitant initial investment and the process's extensive energy needs. This high energy consumption not only makes the process costly but also, when powered by fossil fuels, leads to CO₂ emissions that accelerate climate change. Furthermore, the process generates brine, a highly saline waste product that poses a distinct environmental threat [

10].

The integration of renewable energy sources (RES) presents a transformative pathway for powering desalination, offering a sustainable alternative to fossil fuel-dependent systems. By harnessing clean and abundant resources like solar, wind, and geothermal power, the desalination sector can effectively break the link between freshwater production and greenhouse gas emissions [

11,

12]. This synergy is critical for advancing towards a more sustainable and environmentally responsible solution to global water scarcity. Consequently, the coupling of RES with desalination technologies is becoming a focal point of research and development, driven by the dual imperative of energy and water security [

13,

14,

15].

Technological progress is steadily enabling the adoption of cost-effective and eco-friendly desalination methods. Regions with high solar irradiation and wind potential, such as the Middle East, have been early adopters, hosting a significant portion of the world's renewable-powered desalination facilities. As of 2017, there were over 130 such plants in operation globally. The technological breakdown is led by solar photovoltaic systems, which account for approximately 43% of the market, followed by solar thermal 27%, wind 20%, and hybrid systems 10% [

16]. A renewed surge of interest in this field is now being fueled by consistent reductions in the cost of renewable technologies and ongoing breakthroughs in their efficiency and storage capabilities.

Energy storage systems (ESS) are becoming essential part of desalination system powered by renewables primarily because they mitigate the intermittent nature of renewable energy sources and ensure a stable, flexible power supply [

17]. The growing demand for sustainable energy solutions has spurred significant interest in ESSs in recent years. These systems are particularly vital in microgrids (MG), where they address power flow management challenges by storing surplus energy during low-demand periods and discharging it during peak demand, thereby enhancing grid reliability and stability [

18]. A key advantage of ESSs in microgrids is their ability to facilitate the integration of a greater share of renewable energy sources [

19,

20]. Numerous types of energy storage systems exist, each operating on distinct principles. Battery energy storage systems (BESS) are among the most common ones.

BESS represent a major category within the broader field of energy storage systems. In microgrid applications, for instance, integrating BESS with renewable energy sources offers a cost-effective solution. Projections from the Statista Research Department indicate that by 2030, Europe alone will have installed 57 GW of BESS capacity [

21]. For short-term storage, lithium-ion batteries have become the prevailing technology, largely supplanting older alternatives. This shift is propelled by continuous technological advancements and the decreasing cost of lithium-ion cells, which currently dominate the market for new installations. Despite falling cell prices, batteries continue to constitute the most significant expense in a BESS [

22].

Fuel Cell Systems (FCS) represent another critical technology within the energy storage landscape, distinct from batteries in their operation as electrochemical power generators. In a microgrid context, fuel cells can provide reliable, long-duration backup power and enhance overall system resilience especially in the transportation industry [

23]. Unlike batteries that store energy, fuel cells continuously produce electricity through a chemical reaction, typically between hydrogen and oxygen, with water and heat as the primary byproducts. This makes them particularly suitable for RES applications requiring sustained power output over extended periods [

24].

The interest in fuel cell technology is growing, supported by advancements in efficiency and a global push towards green hydrogen as an energy carrier. While the upfront cost of fuel cells remains a significant hurdle, decreasing electrolyzer costs and the potential for renewable hydrogen production are improving their economic viability. For desalination systems, stationary fuel cells can provide combined heat and power (CHP), significantly increasing overall energy efficiency by utilizing the thermal byproduct. When integrated with renewable sources, fuel cells can convert excess solar or wind energy into hydrogen via electrolysis, which is then stored and used to generate electricity on demand. This capability positions fuel cells as a key solution for long-term seasonal energy storage, a challenge that batteries alone cannot easily address.

The integration of fuel cell systems with battery energy storage systems presents a promising hybrid approach for powering energy-intensive desalination plants. This configuration, often referred to as a Hybrid Energy Storage System (HESS), leverages the complementary strengths of both technologies: the high-power density and rapid response of batteries for handling short-term load fluctuations, and the high-energy density and sustained output of fuel cells for providing stable base-load power [

25]. For reverse osmosis (RO) or electrodialysis (ED) facilities, such a system can effectively smooth the intermittent power supply from solar or wind sources, ensuring continuous and efficient operation while reducing reliance on the main grid.

By mitigating the high energy demands and operational costs associated with desalination, a battery-fuel cell HESS can enhance the economic viability and environmental sustainability of freshwater production. This synergy not only helps in managing the variable energy consumption of the desalination process but also contributes to a more resilient and decarbonized water-energy nexus.

This review paper begins with an overview of the main desalination technologies, establishing the context for their energy demands and the necessity for efficient hybrid storage systems (

Section 2). The paper then details the electrochemical technologies employed in Hybrid Energy Storage Systems (HESSs), offering a classification and analysis of various battery and fuel cell types and their characteristics (

Section 3 and

Section 4). The aim is to survey recent advancements and the current state of battery and fuel cell technology for HESSs. Subsequently, the paper examines a range of energy management strategies, from traditional methods such as proportional-integral-derivative (PID) control to advanced techniques including model predictive control (MPC), fuzzy logic control (FLC), and artificial neural network (ANN) control (

Section 5). Discussion of the results follows in

Section 6. Key information of the discussion section is leading to the final conclusions.

Overall, this review serves as a valuable reference for researchers and engineers engaged in the design and optimization of hybrid energy storage systems based on batteries and fuel cells, as well as for policymakers interested in supporting the integration of renewable energy sources for desalination technologies.

2. Desalination Technologies

The evolution of desalination from a niche thermal process to a cornerstone of modern water security has been punctuated by a series of transformative technological breakthroughs. Modern thermal desalination technology has evolved from an ancient concept into an industrial process. Although its core principle was utilized by Minoan sailors and documented by Aristotle, practical application required the energy infrastructure of the Industrial Revolution [

26]. This enabled milestones such as the first land-based plant in 1928 and the subsequent mid-20th century innovations of Multi-Stage Flash (MSF) and Multi-Effect Distillation (MED). These technologies established thermal desalination as the industry standard for large-scale water production. A paradigm shift occurred mid-century with the rise of membrane-based separation, first through electrodialysis (ED) in the 1950s for brackish water, and more decisively with the advent of reverse osmosis (RO) in the 1960s. The subsequent refinement of thin-film composite membranes and high-efficiency energy recovery devices cemented RO's dominance, while established thermal (MSF, MED) and electrochemical (ED) technologies pursued incremental gains. Today, the field stands on the cusp of a new revolution, driven by advanced materials science and electro-chemical processes,

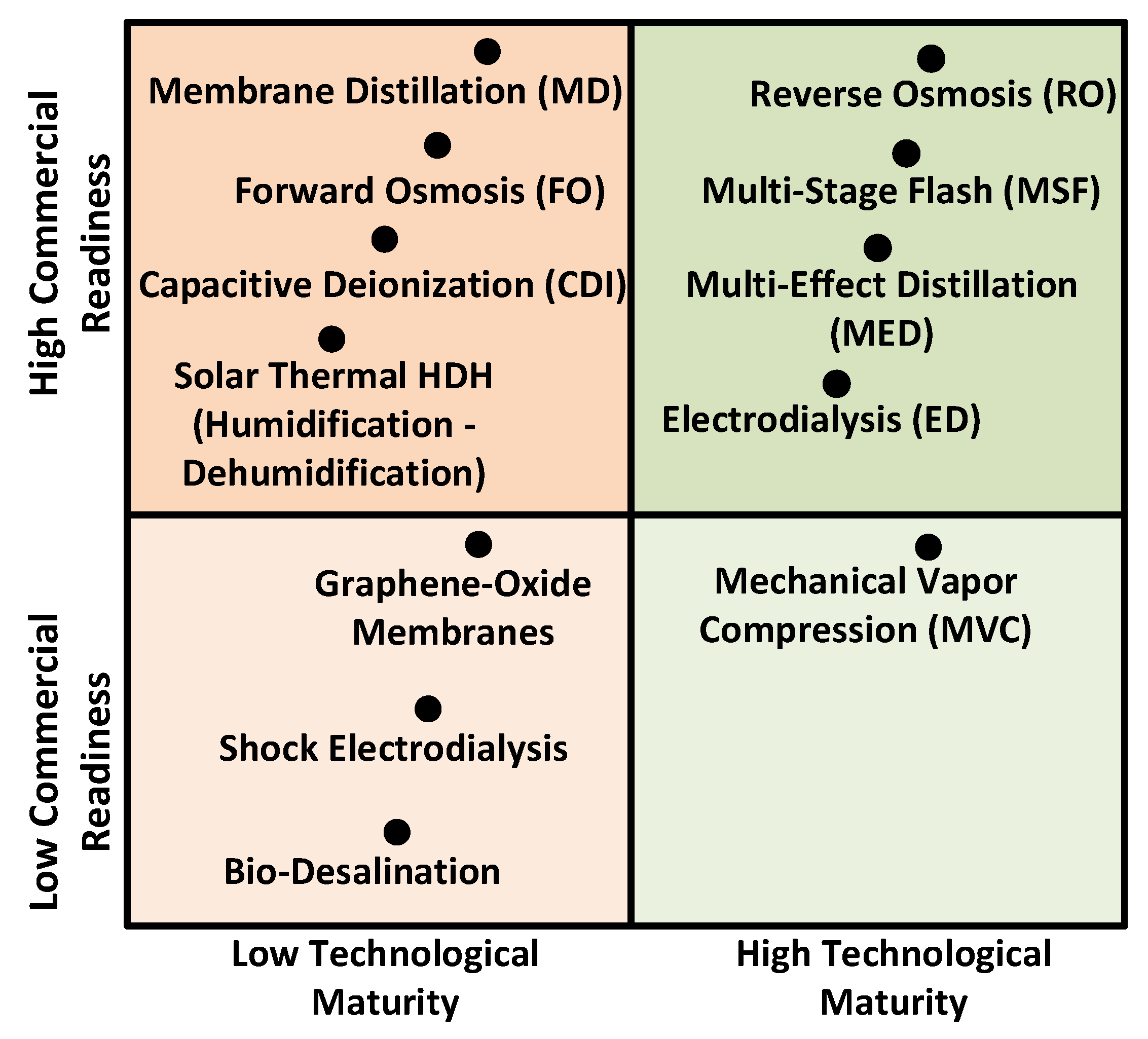

Figure 1. This chapter briefly describes some of the established and emerging desalination technologies and specifically focuses on renewable energy-powered RO with integrated energy storage systems.

2.1. Established Processes

2.1.1. Multi-Effect Distillation (MED)

Multi-Effect Distillation is a robust thermal desalination process renowned for its high efficiency. The core principle involves repeating the evaporation and condensation process across multiple stages, known as "effects." In a typical MED plant, steam or hot water from an external source (often a power plant for co-generation) flows through the tubes of the first effect. This heats the feed-seawater, causing it to evaporate [

27,

28]. The generated vapor then serves as the heat source for the subsequent effect, which operates at a lower pressure and temperature. This vapor is condensed to produce fresh water, while the process simultaneously creates more vapor for the next stage. This efficient reuse of latent heat across several effects significantly reduces the system's overall energy consumption compared to other thermal methods. MED plants are characterized by their reliability, ability to handle varying feed salinities, and high-quality distillate output. They are particularly advantageous in co-generation facilities where waste steam or low-pressure heat is readily available, maximizing energy utilization. Modern advancements, such as Thermal Vapor Compression (TVC) [

29], which recycle vapor to boost efficiency, have further solidified MED's role as a competitive and mature technology for large-scale water production, especially in regions where thermal integration is feasible.

2.1.2. Multi-Stage Flash (MSF)

Multi-Stage Flash distillation is a cornerstone thermal desalination technology, historically dominating the large-scale production of freshwater from seawater, particularly in the Middle East. Its operation is centered on the principle of "flashing." Heated feed seawater is introduced into a series of chambers (so-called stages), each maintained at a progressively lower pressure [

30]. As the water moves into a stage with pressure below its saturation point, a rapid, violent boiling occurs—termed "flashing"—where a portion instantly vaporizes. This vapor contacts the tubes of the heat exchanger, condensing into fresh distillate [

31]. The latent heat released during this condensation preheats the incoming feed water flowing through those same tubes, a key mechanism for energy recovery.

The process repeats through numerous stages (often 15-25), maximizing heat reuse and significantly improving thermal efficiency compared to single-stage boiling. MSF plants are renowned for their robust construction, high reliability, long lifespan, and ability to handle feedwater with high salinity and poor quality with less pre-treatment than membrane systems. However, their intensive thermal energy requirements, high operating temperatures promoting scaling, and large capital costs have curtailed their adoption for new projects, where Reverse Osmosis (RO) is often the more energy-efficient choice. MSF remains crucial in co-generation facilities where steam waste heat is readily available. In some cases, it is possible to combine MSF with MED technology [

32].

2.1.3. Electrodialysis (ED)

Electrodialysis is an electrochemical desalination process that separates salt ions from water using electrical energy and ion-exchange membranes, rather than using heat or pressure [

33]. Its core components are alternating anion-exchange membranes (AEM) and cation-exchange membranes (CEM), arranged between an anode and a cathode. When an electrical potential is applied, dissolved salt ions are selectively transported through these membranes: cations, such as Na⁺ move toward the cathode, passing through CEMs, while anions, such as Cl⁻ move toward the anode, passing through AEMs. This migration creates alternating channels of concentrated brine and diluted freshwater, which are then separately extracted.

A significant variant is Electrodialysis Reversal (EDR), which periodically reverses the polarity of the electrodes [

34]. This clever innovation helps to disrupt membrane scaling and fouling, reducing the need for chemical pre-treatment and enhancing operational stability. Unlike Reverse Osmosis, ED is not well-suited for high-salinity seawater desalination due to prohibitive energy costs. Instead, it is highly efficient and competitive for desalinating brackish water, achieving higher water recovery rates and requiring less extensive pre-treatment. This makes ED/EDR a mature and vital technology for specific applications, including industrial process water production, wastewater reclamation, and in the production of potable water from low-salinity sources.

2.1.4. Mechanical Vapor Compression (MVC)

Mechanical Vapor Compression is a thermal desalination process that operates on a highly efficient, self-contained cycle, primarily powered by electrical energy. The core of the system is a mechanical compressor, which is the key differentiator from other thermal technologies, such as MED or MSF [

35]. The process begins as seawater is sprayed onto the exterior of a heat exchanger bundle. The low-pressure vapor already present in the chamber is drawn into the compressor, which increases its pressure and temperature significantly. This now energy-rich vapor is then circulated inside the heat exchanger tubes, where it condenses into fresh water, releasing its latent heat in the process. This released heat causes the seawater on the outside of the tubes to evaporate, generating more vapor to sustain the cycle.

This closed-loop design, which continuously recycles the vapor's latent heat, allows MVC units to achieve high thermal efficiency without needing an external steam supply [

36]. Consequently, MVC is highly compact and mechanically simple. However, this efficiency is offset by the high electrical energy demand of the compressor, which becomes economically prohibitive at a very large scale. MVC is therefore not a competitor for large seawater reverse osmosis (SWRO) or multi-stage flash plants. Instead, it excels in decentralized, small-to-medium-scale applications where reliability and simplicity are paramount, such as for industrial processes, resorts, islands, and vessels, particularly for treating high-salinity feedwater that would challenge membrane systems.

2.1.5. Reverse Osmosis (RO)

Reverse Osmosis is the globally dominant desalination technology, utilizing a semi-permeable membrane and applied hydraulic pressure to separate dissolved salts and impurities from water [

37]. The core principle involves applying pressure—exceeding the natural osmotic pressure of saline feedwater—to force water molecules through a dense polymeric membrane, while rejecting up to 99.8% of dissolved salts, organic compounds, and microorganisms. This process is enabled by advanced thin-film composite (TFC) polyamide membranes, which offer high salt rejection and sufficient water permeability.

The supremacy of RO is largely due to its superior energy efficiency compared to thermal desalination methods, a achievement unlocked by the development of high-efficiency energy recovery devices (ERDs) that reclaim pressure from the concentrated brine stream. RO plants are modular, scalable, and form the backbone of modern water supply for municipalities and industries worldwide. However, the technology faces challenges including membrane fouling and scaling, which require extensive pre-treatment and chemical cleaning, and the environmental management of the concentrated brine byproduct. Continuous innovation in membrane materials, such as nanocomposites, aims to further enhance permeability, fouling resistance, and longevity, cementing RO's role as the cornerstone of the desalination industry.

2.2. Emerging Processes

2.2.1. Graphene-Oxide (GO)

Graphene-Oxide membrane technology represents a frontier in advanced materials for desalination and molecular separation. This technology utilizes ultrathin membranes fabricated from nanosheets of graphene oxide, a derivative of graphene [

38]. The separation mechanism is fundamentally different from traditional polymeric membranes; it relies on molecular sieving through precisely sized nanochannels formed between the stacked GO layers and through intrinsic defects, allowing for ultra-fast water transport while blocking salt ions and other contaminants. A key advantage is the potential for tunable selectivity, where the nanochannel spacing can be chemically or physically adjusted to target specific ions, such as divalent salts for nanofiltration-like applications or even monovalent salts for reverse osmosis [

39].

The theoretical promise of GO membranes is extraordinary, primarily due to their atomic thinness, which minimizes hydraulic resistance and could lead to water permeability rates orders of magnitude higher than current polyamide membranes. This translates to the potential for significantly lower energy consumption and operational costs in desalination plants. However, this technology remains predominantly in the research and development phase. Critical challenges, such as membrane stability in aqueous environments, controlling swelling to maintain precise pore size, and developing scalable, cost-effective manufacturing processes, must be overcome before widespread commercial deployment can become a reality.

2.2.2. Shock Electrodialysis (SED)

Shock Electrodialysis is a novel, membrane-less desalination technology that utilizes the principle of ion concentration polarization (ICP) and the formation of propagating deionization shock waves to separate salt from water [

40]. Unlike conventional ED, it operates without ion-exchange membranes. The process occurs within a microfluidic channel filled with a porous medium. When an electric current is applied, it creates a sharp boundary, or "shock" front, between ion-depleted and ion-concentrated zones. This shock wave propagates through the channel, effectively pushing concentrated brine ahead of it and leaving behind desalinated water, which is then extracted.

This technology is fundamentally disruptive due to its elimination of membranes, thereby avoiding the perennial issues of fouling, scaling, and degradation that plague membrane-based systems. Its theoretical advantages include extreme robustness, the potential for high water recovery, and operation with minimal pre-treatment. However, SED is currently a predominantly conceptual and early-stage laboratory technology [

41]. Significant engineering challenges remain in scaling the process from microfluidic devices to industrial capacities, managing energy efficiency at larger scales, and stabilizing the shock waves in practical, continuous-flow systems. It represents a promising future pathway for desalination, but one that is still firmly within the domain of foundational research.

2.2.3. Forward Osmosis (FO)

Forward Osmosis is an osmotic process that utilizes a draw solution with higher osmotic pressure than the saline feedwater to naturally draw water through a semi-permeable membrane [

42]. Unlike reverse osmosis, which uses external hydraulic pressure to overcome osmosis, FO harnesses the natural osmotic pressure gradient, resulting in a fundamentally lower energy input for the separation step itself. The diluted draw solution then undergoes a secondary, often energy-intensive, separation process to recover the fresh water and regenerate the concentrated draw solution for reuse.

The technology's primary advantages lie in its low membrane fouling propensity and high theoretical water recovery, making it exceptionally suitable for treating challenging wastewaters and highly concentrated brines where RO would struggle. However, FO is not a standalone technology; its viability is entirely dependent on the efficiency of the draw solution recovery process. This has limited its widespread commercialization, as finding an ideal draw solute, one that is easily and economically separated, remains a key challenge. Consequently, FO has found niche commercial applications in areas like industrial wastewater concentration, food processing, and as a pre-treatment step to reduce the load on downstream RO systems, rather than as a direct competitor for seawater desalination.

A brief overview of the mentioned desalination technologies is presented in

Table 1.

2.3. RES-Powered Desalination Systems

The integration of renewable energy is pivotal for decarbonizing the desalination processes and particularly energy-intensive reverse osmosis (RO) desalination. Hybrid systems that combine solar and wind power are emerging as a robust solution, leveraging the complementary nature of these resources to enhance energy reliability and system resilience [

43]. Photovoltaic (PV) panels generate electricity during peak daylight hours, often aligning with high water demand, while wind turbines can provide power day and night, particularly in coastal regions where consistent winds are common [

44]. This synergy mitigates the intermittency of a single renewable source and ensures a more stable energy supply for the constant operation of high-pressure pumps and pretreatment systems. By displacing fossil fuels with this complementary mix, solar-wind-RO systems significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions and offer the potential to stabilize long-term operational costs. The modularity of PV, wind turbines, and RO systems enables highly scalable deployments, making this integrated approach a technically and economically viable strategy for a wide range of applications, from off-grid communities to large-scale municipal water supply.

Furthermore, maximizing efficiency requires optimizing the largest energy consumer of the RO unit: the high-pressure pump [

45]. Advanced control strategies are essential to minimize its input power. Techniques such as variable frequency drives (VFDs) [

46], predictive control [

47], and energy-optimized scheduling algorithms [

48] allow the pump's operation to be precisely modulated in response to real-time changes in renewable power availability, feedwater salinity, and membrane conditions. This dynamic optimization reduces specific energy consumption, mitigates the load on the energy storage system, and extends equipment lifespan. Intelligent pump control is leading to a more reliable and economically viable desalination process.

However, even with the fully optimized and balanced RO unit, the inherent intermittency of solar and wind resources introduces significant challenges for the continuous operation required by RO. This underscores the critical necessity of advanced energy storage systems to balance generation and demand, ensure voltage stability, and provide uninterrupted power for sensitive RO components like high-pressure pumps.

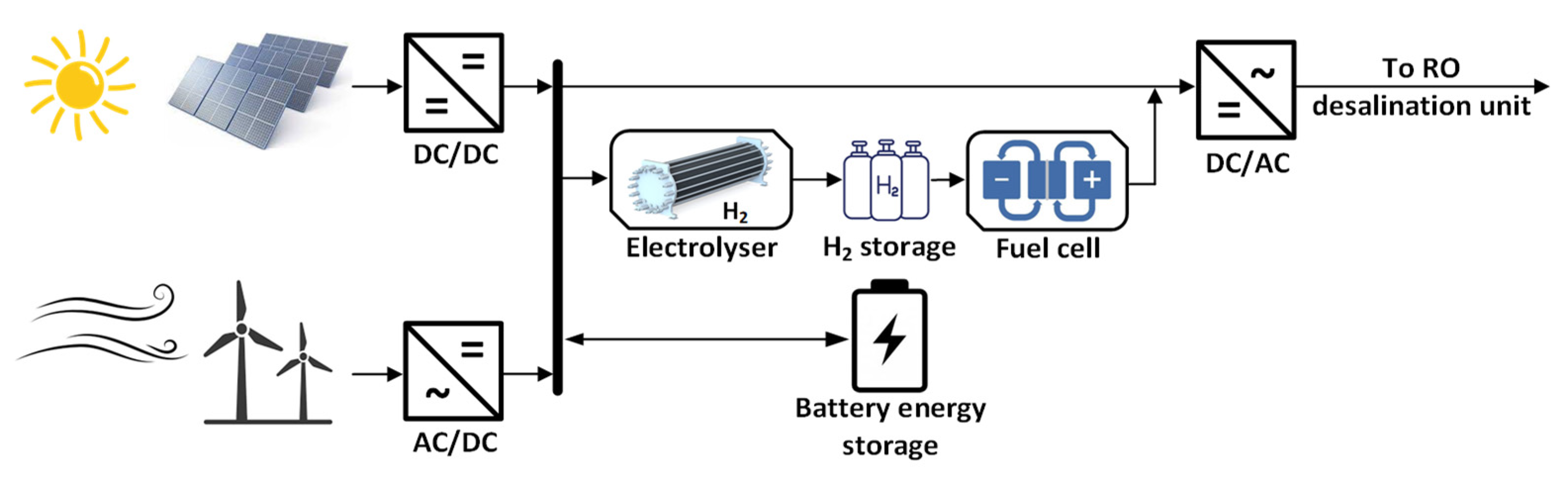

Among storage options, hybrid systems are particularly significant solutions [

49]. Batteries offer excellent responsiveness for managing short-term fluctuations and frequency regulation, while hydrogen-based fuel cells provide sustained [

50], long-duration energy storage. Excess solar and wind energy can be used to produce hydrogen via electrolysis, which is then stored and reconverted to electricity by the fuel cell during extended periods of low renewable generation [

51],

Figure 2. This integrated approach not only guarantees 24/7 operability without fossil fuel backup but also maximizes the utilization of renewable assets, ultimately leading to a more reliable, efficient, and truly sustainable desalination process that can significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions and stabilize long-term operational costs.

In [

52], the authors introduced a solar- wind- powered RO desalination plant with integrated PV panels and wind turbines (WT) for power generation, a battery bank for short-term energy storage, a RO unit for desalination, and freshwater storage tanks. To address long-term energy storage needs, a hydrogen storage system was incorporated to store surplus electricity accumulated at the end of each daily cycle. The RO process was primarily driven by solar and wind generation, with any excess energy directed to a combined battery–hydrogen storage (BHS) system for later use. Same authors, in [

53] showed that hydrogen energy storage systems are essential for managing renewable intermittency in desalination but introduce significant cost and safety challenges. They presented a safety-oriented optimization framework for designing HESS in a hybrid solar-wind powered reverse osmosis system. A comprehensive risk assessment method was developed to evaluate critical HESS design parameters such as storage size, pressure, flow rate, and temperature.

Some studies suggested a poly-generation approach designed to generate electricity, green hydrogen, ammonia, and produce fresh water [

54]. This technology allows us to utilize the waste heat generated by the fuel cell for desalination purposes. The novel system in [

55] employs a water-hydrogen nexus to facilitate renewable seawater desalination. Using hydrogen as an energy carrier, the system optimally co-generates electricity, heat for desalination, drinkable water, and green hydrogen itself.

3. Electrochemical Energy Storages

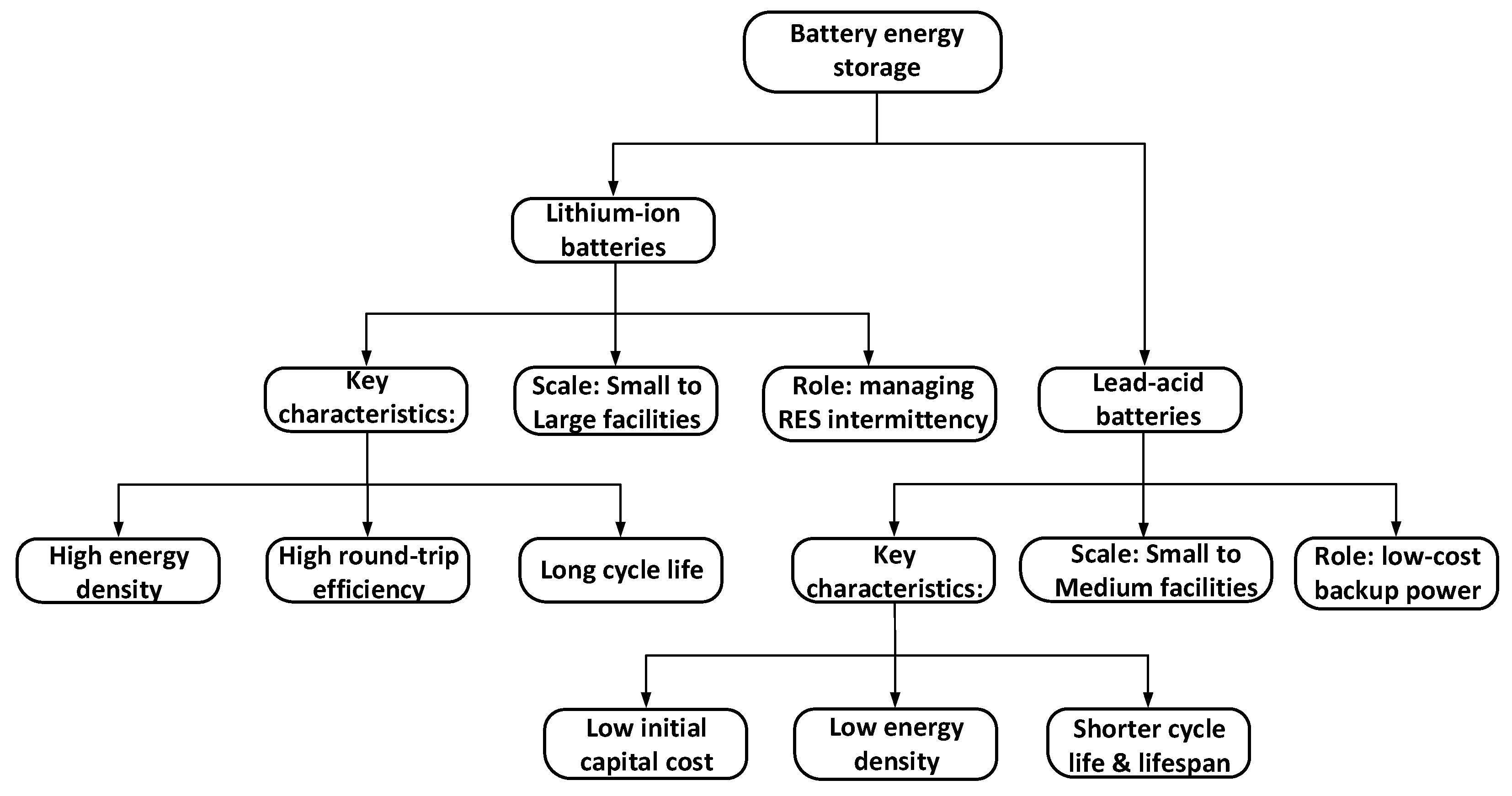

The integration of electrochemical energy storage is essential for enabling the widespread adoption of intermittent renewable sources in power-intensive applications like desalination. This chapter examines the critical role of these systems in stabilizing energy supply, managing demand fluctuations, and ensuring the operational reliability of desalination plants. A particular focus is placed on the dominant technology in this domain: lithium-ion batteries. Owing to their high energy density, declining cost, and operational efficiency, Li-ion batteries have become the cornerstone of short-duration energy storage solutions [

56]. They are exceptionally capable of providing rapid frequency regulation, smoothing short-term solar and wind variability, and optimizing the energy use of reverse osmosis systems. Li-ion batteries are highly suitable for renewable energy applications in desalination, from small to large facilities, due to their high energy density.

In contrast, lead-acid batteries are typically used in small-to-medium-scale storage systems because of their lower cost, though they offer reduced energy density and a shorter operational lifespan compared to li-ion alternatives. These storage technologies are particularly advantageous for reverse osmosis and electrodialysis desalination plants, where a consistent and reliable power supply is critical,

Figure 3.

In a renewable-powered RO desalination plant, the battery energy storage system must continuously undergo charge and discharge cycles to ensure a stable power supply for the high-pressure pumps and system controls. The energy management algorithm prioritizes charging the BESS when excess renewable energy is available, particularly when the battery's state of charge (SoC) is low. Subsequently, the BESS discharges to power the RO unit when renewable generation is insufficient, such as during nighttime or cloudy periods.

For effective and safe integration, two key parameters are monitored: the state of charge and depth of discharge (DoD). SoC indicates the available energy reserve in the battery (100% = fully charged, 0% = fully depleted). DoD measures the fraction of the total capacity that has been used. Managing a shallow DoD is crucial for RO applications, as it extends battery lifespan by reducing stress. Maintaining an optimal SoC range is essential for both protecting the battery and guaranteeing it can always respond to the RO plant's high-energy demands, ensuring uninterrupted and safe desalination operation. SoC and DoD are described with the help of the following equations [

57]:

where I(t) is a load current (A) and Q is a maximum battery capacity (Ah), t

0 is initial time of measurement. To effectively analyze battery charge and discharge characteristics, key parameters such as source voltage, internal resistance, and current must be accurately known.

3.1. Lead-Acid Batteries

Lead-acid batteries represent one of the most mature rechargeable battery technologies and have historically been widely used in various energy storage applications, including renewable energy buffering for desalination systems [

58]. They operate on the principle of converting chemical energy into electrical energy through a reaction between lead dioxide (PbO₂) as the positive plate, sponge lead (Pb) as the negative plate, and a sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) electrolyte. While their use is declining in favor of more advanced technologies like lithium-ion, they remain relevant in certain contexts due to their low upfront cost, reliability, and ease of recycling [

59].

There are several types of lead-acid batteries, with variations in design that cater to different operational needs:

There are two main subtypes of VRLA:

Absorbent Glass Mat (AGM): Uses a fiberglass mat to absorb the electrolyte, making it spill-proof, resistant to vibration, and capable of delivering high currents. It has a low self-discharge rate and is suitable for applications requiring reliability with minimal maintenance.

Gel: The electrolyte is gelled with silica, which immobilizes it. These batteries are highly resistant to shock, vibration, and deep discharges, and have a very low self-discharge rate. However, they are sensitive to overcharging and require careful charge voltage control.

The demanded capacity of the battery energy storage system - C

Wh, can be calculated according to the equation:

where E

L represents energy load demand, AD is BESS’s autonomy per day, η is system efficiency, and DoD is an acceptable depth of discharge for a particular battery type. In [

61], authors presented the optimization procedure for the PV-battery system (BS) of desalination plant for irrigation in an isolated region in Al Minya in Egypt. It was shown that the PV system with 75 kW production capacity, BS consisting of 32 units of lead-acid battery - Trojan L16P, and converter with output power of 28 kW is satisfying the optimization criteria.

3.2. Lithium-Ion Batteries

Lithium-ion batteries operate on the principle of reversible lithium-ion movement between a cathode and an anode through an electrolyte. During discharge, lithium ions move from the anode to the cathode, releasing electrons to an external circuit to power loads such as high-pressure RO pumps. During charging, this process is reversed using energy from photovoltaic or wind sources. Key advantages include high round-trip efficiency (~95%), the ratio of energy delivered during discharge to the energy absorbed during charging, low self-discharge, and scalability, making them ideal for balancing energy supply with desalination demand. During charging, the battery energy storage system functions as a load, consuming power, whereas during discharging, it operates as a generator, supplying power. For instance, in grid applications, batteries charge during periods of renewable energy surplus and discharge during peak demand, effectively acting as generators when renewable availability is insufficient. This dual operational role of battery storage systems can be represented by the following equations:

In equation (4), V and I represent the charging voltage and current, respectively, while η

rt in equation (5) denotes the round-trip efficiency, accounting for all charging losses. Additionally, self-discharge and parasitic losses must be considered as they significantly limit the effective capacity and performance of the energy storage system. As demonstrated in [

62], commercially available Li-ion batteries offer substantial advantages over traditional nickel-metal hydride or lead-acid batteries. These include higher round-trip efficiency, superior energy and power density, minimal maintenance requirements, and enhanced sustainability. A key benefit is their very low self-discharge rate, typically between 2% and 5%, which further bolsters their efficiency and suitability for long-duration applications.

Lithium-ion batteries represent a category of energy storage technologies defined by diverse chemical compositions, utilizing different anode and cathode materials to achieve varied performance characteristics [

63]. Several cathode chemistries define a unique balance of trade-offs in safety, energy density, cost, cycle life, and operational performance:

Lithium Titanate Oxide (LTO): Represents a unique lithium-ion chemistry that replaces the traditional graphite anode with one made of lithium titanate. This fundamental change grants LTO exceptional advantages, most notably extremely fast charging, a very long cycle life, and superior safety due to its high thermal stability and elimination of lithium plating [

64]. However, these benefits come at the cost of lower energy density and a higher upfront cost compared to NMC or LFP batteries. LTO is ideally suited for applications where reliability, rapid cycling, and safety are paramount, such as in public transportation buses, and grid frequency regulation.

Lithium Nickel Manganese Cobalt Oxide (NMC): Offers a balance of energy density, cycle life, and cost. Its cathode blends nickel, manganese, and cobalt, offering greater stability and longer cycle life than NCA variants, though at a slightly lower energy density [

65]. NMC batteries are prevalent in electric vehicles, power tools, and renewable energy storage due to their reliability. Widely used in medium- to large-scale energy storage.

Lithium Nickel Cobalt Aluminum Oxide (NCA): High specific energy and good longevity but requires careful thermal management. Its cathode combines nickel for reversibility, cobalt for stability, and aluminum to reduce structural stress during cycling. NCA batteries offer high energy and power density, making them suitable for electric vehicles and power tools [

66]. Common in grid storage and automotive applications.

Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP): Distinguished by its exceptional safety, long cycle life, and stability. Though lower in energy density than NMC or NCA, its operational safety and durability is high [

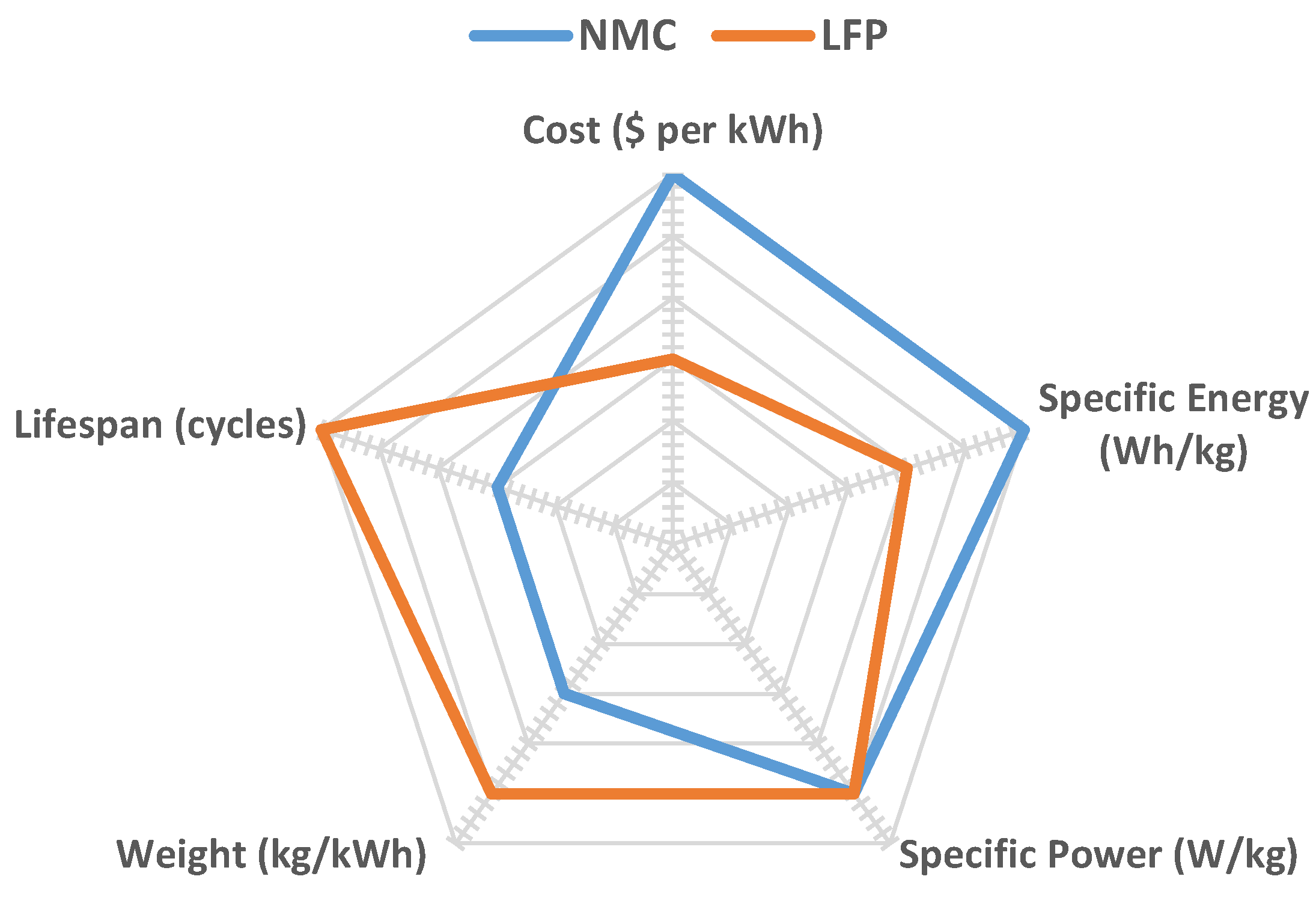

67]. These batteries are particularly well-suited for renewable energy-powered RO desalination due to their safety, long cycle life, and cost-effectiveness. Their superior thermal stability reduces fire risk, a critical advantage in remote or arid locations, while their ability to endure frequent charging and discharging aligns perfectly with solar or wind intermittency. Although LFP has a lower energy density than NMC, resulting in larger battery banks, this is often an acceptable trade-off for stationary RO applications where space is less constrained than in vehicles,

Figure 4. The technology’s main limitations, reduced performance in cold climates and difficulties in state-of-charge estimation due to its flat voltage curve, can be mitigated with proper system design, insulation, and advanced battery management software. For these reasons, LFP has become the leading storage choice for sustainable, off-grid, and hybrid-powered RO desalination systems.

Battery energy storage systems are essential not only in grid-connected RES-powered applications but also in off-grid and weak-grid contexts, particularly in remote or underserved areas such as rural communities and mining sites. When integrated with renewable energy sources, BESS compensates for the intermittency of solar and wind generation, ensuring a continuous and reliable power supply. In the absence of grid support, batteries stabilize systems by managing load variations, preventing operational disruptions during periods of low renewable generation, and delivering critical surge power to start and run high-demand equipment such as high-pressure reverse osmosis pumps.

4. Fuel Cell Technologies

4.1. Fuel Cell Role in Renewable-Powered Desalination

Fuel cells convert the chemical energy of a fuel, most commonly hydrogen, and oxygen from air directly into electricity, releasing heat and water as by-products. The defining feature is continuity: a fuel cell keeps delivering power as long as it receives fuel and oxidant, whereas a battery is limited by its stored charge. In desalination plants supplied by solar and wind, this distinction matters because the renewable resources are variable while the water demand is not. Batteries are excellent at absorbing fast fluctuations and covering short gaps, but they become bulky and expensive when asked to bridge long night periods or multi-hour wind lulls. Fuel cells fill that role naturally. They can be scheduled at a steady operating point across the hours when renewable generation is inadequate, allowing the desalination process, especially reverse osmosis, to run under stable power and pressure conditions. This steadiness reduces membrane stress, cuts the number of start–stop events, and improves uptime [

68].

An additional advantage is thermal. The heat rejected by a fuel cell is not a nuisance in a desalination plant; it is an asset. Low-temperature fuel cells produce warm water and coolant streams that can preheat the feed, support low-temperature processes such as membrane distillation, or temper intake and pretreatment stages. High-temperature fuel cells provide much hotter exhaust that can drive thermal auxiliaries, organic Rankine or absorption cycles, or hybrid RO–thermal schemes. When the site includes electrolysis, excess solar and wind power is converted to hydrogen and stored, and the fuel cell closes the loop during periods of low renewable output [

69]. In this way, hydrogen becomes the long-duration buffer that batteries cannot economically provide, while the battery remains in charge of the rapid dynamics [

70].

4.2. Fundamentals and Design Aspects Relevant to Coastal Plants

All fuel cells share the same core architecture. On the fuel side, the anode catalyzes the oxidation of hydrogen or another fuel; on the air side, the cathode catalyzes oxygen reduction. Between them sits the electrolyte, which conducts ions but blocks electrons so that useful current flows through the external circuit. Around the stack, the balance of plant handles air filtration and compression, thermal management and humidification, fuel processing and safety, water management, and power electronics.

Coastal environments impose specific requirements on that balance of plant. Salt aerosols and fine sand mandate high-grade filtration and corrosion-resistant materials in air paths and enclosures. Service water for humidifiers, coolant make-up, and periodic cleaning must have very low conductivity; RO permeate is a convenient source, provided chloride ingress to the stack is prevented. Start-up and ramp sequences must be coordinated with the high-pressure pumps and energy-recovery devices typical of reverse osmosis, so that electrical transients do not translate into hydraulic shocks. Safe handling of hydrogen requires proper zoning, ventilation, leak detection, and vent placement with prevailing winds in mind.

4.3. Technology Families and Their Fit for Desalination Duty

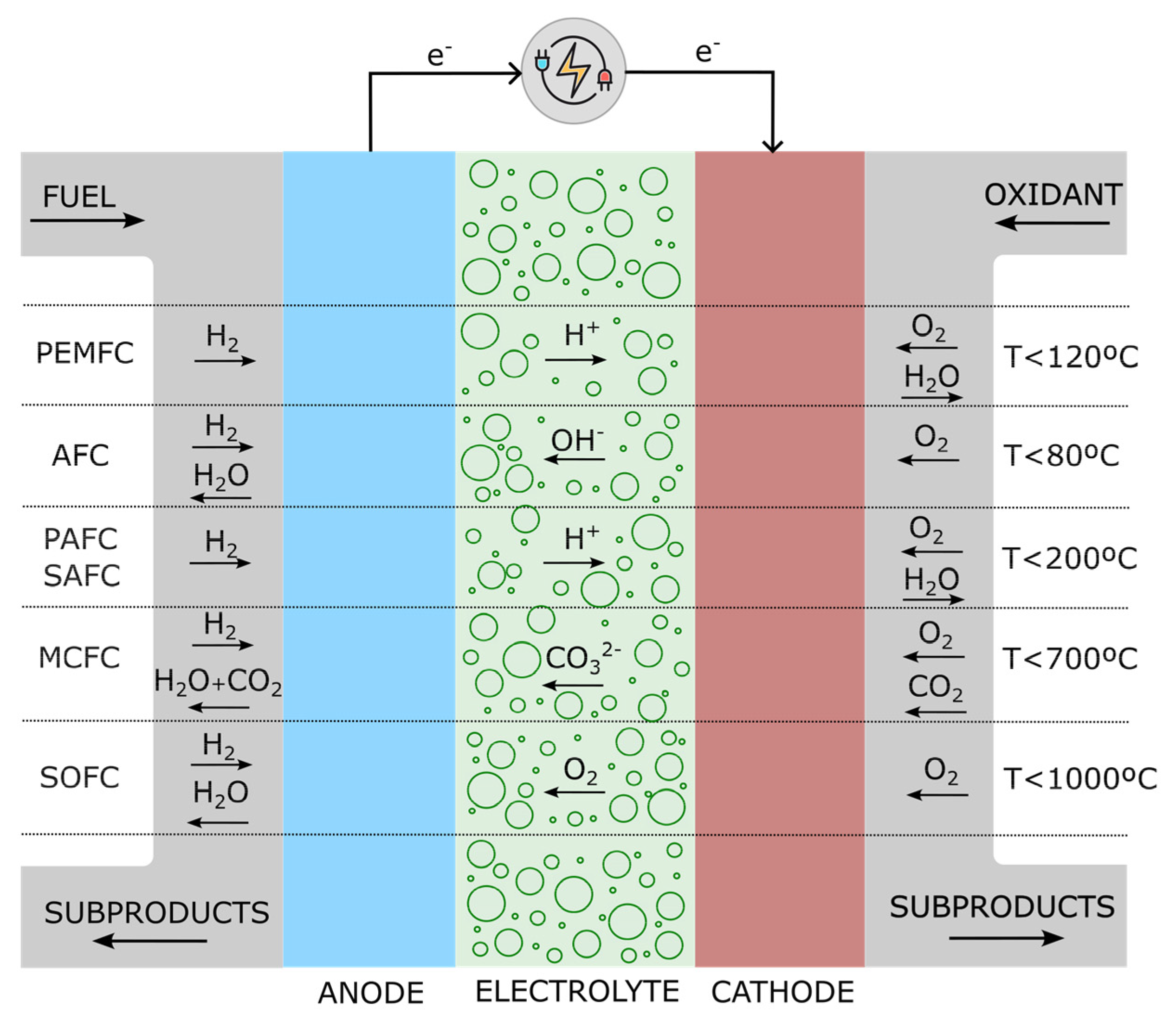

Although the underlying electrochemistry is similar, fuel cell families differ in electrolyte, operating temperature, impurity tolerance, dynamics, and the grade of heat they produce. These differences determine how each type integrates with desalination processes. Adapted from [

71],

Figure 5 presents a schematic of the main fuel cell technologies and their operating principles. Details of each type are provided below.

Alkaline fuel cells (AFCs) use an aqueous alkaline electrolyte, typically potassium hydroxide. Hydroxide ions move from the cathode to the anode; at the anode, hydrogen reacts with OH⁻ to form water and electrons, and at the cathode oxygen combines with water and electrons to regenerate OH⁻. The operating temperature is modest, usually around 60–80 °C, which simplifies thermal management and enables quick starts. The major drawback is sensitivity to carbon dioxide: CO₂ in the air or in the fuel converts the electrolyte into carbonates and degrades performance. In a coastal, open-air setting that sensitivity is a serious design constraint unless CO₂ scrubbing is provided [

72]. When CO₂ can be controlled and very fast starts are valuable, small, islanded RO plants with frequent on/off cycles are a typical case, AFCs can be effective. Recent anion-exchange membrane variants aim to reduce CO₂ uptake by replacing liquid KOH with a solid membrane, but these systems are less mature than polymer electrolyte fuel cells [

73].

Proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs) employ a solid polymer electrolyte that conducts protons. At the anode, hydrogen splits into protons and electrons; protons cross the membrane and combine with oxygen at the cathode to form water. PEMFCs operate near 60–80 °C, with high-temperature formulations reaching around 120 °C [

74]. They are compact, respond rapidly to load changes, and start readily from cold, which makes them a natural partner for battery-smoothed RO operation. They are not affected by CO₂ in air, but they require very clean hydrogen because the catalysts are sensitive to carbon monoxide, sulfur compounds, and ammonia. The heat they produce is low-grade but still useful for feed preheating or low-temperature tasks. In most small to medium hybrid plants that prioritize operational simplicity and frequent cycling, PEMFCs provide the best overall match [

75].

Phosphoric acid fuel cells (PAFCs) and sulfuric acid variants use liquid acids as electrolytes, so the charge carrier is also the proton, but the operating window moves up to roughly 150–200 °C. At these temperatures, the stack yields a steadier flow of medium-grade heat, which can be absorbed by membrane distillation units, thermal pretreatment, or space and water heating within the facility. PAFCs are designed for stationary baseload operation; they ramp and start more slowly than PEMFCs and have lower power density, while still requiring noble-metal catalysts. They tolerate some impurities better than PEMFCs but remain sensitive to carbon monoxide and sulfur, so fuel quality control is still necessary [

76].

Molten carbonate fuel cells (MCFCs) operate much hotter, generally between 600 and 700 °C. The electrolyte is a molten carbonate salt held in a ceramic matrix. The mobile ionic species is CO₃²⁻, which forms at the cathode by reacting oxygen with carbon dioxide. Because carbonate ions carry charge, the cathode requires a controlled supply of CO₂, which is usually recirculated from the anode exhaust. At the anode, hydrogen reacts with CO₃²⁻ to produce water, CO₂, and electrons [

77]. High temperature brings several advantages: platinum is unnecessary, nickel-based electrodes are sufficient, and internal reforming of light hydrocarbons such as natural gas or biogas is possible. The penalty is dynamic, the stacks prefer long, steady campaigns and do not appreciate frequent start–stop cycles, and the balance of plant must handle hot salt environments and CO₂ logistics. Where the desalination complex is large and continuous and can make use of high-temperature heat, for example, by preheating feed to multi-effect distillation, driving mechanical vapor compression auxiliaries, or feeding bottoming cycles, MCFCs can deliver excellent overall efficiency [

78].

Solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) push the temperature envelope further. Their ceramic electrolytes, often yttria-stabilized zirconia, conduct oxide ions from cathode to anode. At the cathode, oxygen molecules accept electrons and become O²⁻; at the anode, hydrogen reacts with O²⁻ to form water and release electrons back to the circuit [

79]. Operating temperatures from roughly 600 up to 1,000 °C allow internal reforming and flexible fueling with clean natural gas, hydrogen, or syngas, without noble metals [

80]. Like MCFCs, SOFCs are not designed for frequent thermal cycling; they are most comfortable in steady baseload service [

81]. The quality of the heat they produce is exceptionally high. In desalination hubs that combine RO with thermal processes, SOFCs unlock cogeneration layouts that use the electrical output for high-pressure pumps and the thermal output for multi-effect or multi-stage systems, absorption chillers, or district heating and cooling that shares infrastructure with the water plant.

4.4. Hybridization with Batteries and Power Electronics

A fuel cell–battery combination is more than a redundancy; it is a coordinated system in which each technology operates where it is most efficient. The battery governs the fast end of the spectrum, catching second-to-second fluctuations from clouds or gusts and smoothing pump inrushes and pressure control events. The fuel cell holds a near-constant set-point chosen for high efficiency and stack longevity, and it adjusts slowly to longer imbalances between renewable supply and desalination demand. This division reduces battery cycling depth, which extends battery life, and it protects high-temperature fuel cells from damaging ramps.

Electrical architecture should reflect that strategy. A common approach is a DC bus that ties together photovoltaics, the battery system, the electrolyser, and the fuel cell through high-efficiency converters. DC coupling minimizes the number of conversions stages and improves round-trip efficiency when excess solar or wind power is stored as hydrogen and later converted back to electricity. On the control side, soft-start and soft-stop sequences for the fuel cell are aligned with the desalination plant’s hydraulic constraints, so that changes in electrical supply never translate into abrupt shifts in feeding pressure or flow.

4.5. Integration Challenges and Mitigations in Coastal Deployment

The promise of fuel cells in desalination is realized only when the details of sitting and operation are handled well. Airborne salt and sand can erode performance if filtration and sealing are not rigorous; filters should be monitored for differential pressure so that airflow and stack stoichiometry remain in specification. Service water purity is not negotiable: humidifiers, coolant loops, and cleaning procedures must use very low-conductivity water, and any interface with seawater systems needs clear physical segregation to prevent chloride contamination of the stack. Where alkaline or molten-carbonate systems are considered, the handling of carbon dioxide becomes a design topic, either to keep it out (AFC) or to deliver it consistently (MCFC). For PEMFCs and PAFCs, the focus is fuel cleanliness; guard beds and polishing steps are common when hydrogen is derived from reforming. High-temperature stacks, MCFCs and SOFCs, reward steady operation; they should be planned for long campaigns with hot standby options, leaving the battery to absorb the frequent cycling.

Hydrogen safety is an overarching requirement. Equipment rooms should be classified appropriately, ventilated to prevent accumulation, and instrumented with reliable leak detection. Vent stacks and relief lines need to be routed with coastal winds and salt spray in mind so that releases disperse safely and do not corrode nearby equipment. Finally, protection and control schemes must coordinate the fuel cell with the desalination train: when a trip occurs on the water side, the electrical side should ramp down gracefully, and when renewable generation falls suddenly, the battery should bridge the gap while the fuel cell adjusts.

4.6. Choosing the Right Fuel Cell for the Application

Matching technology to duty is a pragmatic exercise. Small and medium RO plants that cycle daily and value responsive operation usually favor PEMFCs because they combine fast dynamics with relatively simple integration and readily usable low-grade heat. If the site can continuously use heat near 150–200 °C, through membrane distillation, thermal pretreatment, or site heating, PAFCs merit consideration despite their slower dynamics, but still needs further industrial development. Where the desalination complex is large, continuous, and thermally integrated, MCFC or SOFC options come into their own: they achieve high overall efficiency by pairing electric output with substantial high-temperature heat, at the cost of slower start-ups and stricter thermal management. AFCs occupy a niche in situations that demand very fast starts and can manage CO₂ scrubbing; in open coastal air, that requirement is often decisive.

5. Energy Management Strategies

Hybrid energy systems are typically supervised by an energy management system (EMS) that allocates power and energy among components to meet performance, durability, and economic objectives under operating constraints. In hybrid storage, the EMS leverages complementary device characteristics (e.g., fuel cell: high specific energy; Li-ion battery: high round-trip efficiency; supercapacitor: high power) while mitigating individual limitations [

82]. Most reported architectures pair a fuel cell (FC) with a Li-ion battery and, in many cases, a supercapacitor. Applications include renewable-rich microgrids and electric vehicles; fewer studies address desalination directly, although methods are transferable with appropriate load and constraint models.

For clarity, EMS designs are organized into four families: rule-based, optimization-based, learning-based, and distributed/cooperative,

Figure 6. Rule-based controllers are straightforward to implement and suitable for real-time use but are generally sub-optimal under changing conditions [

83]. Optimization-based methods can approach optimality given a model and a cost function but may incur higher computational burden [

84]. Learning-based methods adapt from data and cope with model mismatch. Distributed/cooperative schemes coordinate multiple assets or controllers with limited communication.

The state-of-art regarding the hybrid energy storage systems in which one of the components is a cell fuel presents the use of very different types of EMS. The investigations found present two different combinations for the HESS, it is mainly a mix of fuel cell and lithium battery, but it is also seen the addition of a supercapacitor to the previous combination. In these studies, these systems are usually used for renewable energy systems with PV and wind generation and electric vehicles, unfortunately there are not a lot of these studies focused on their application for desalination, but the ones focused on RES systems can be similar.

Regarding the control strategies followed on these studies, the majority seem to be different rule-based strategies, with a preference for fuzzy logic. In some cases, optimization-based strategies are also used and even a combination of both types, rule-based and optimization-based, can be considered the option for better efficiency of the system. In the following subsections there is a description of the different control strategies used in some investigations. Considering that all these strategies come from very different studies, all have different applications and even objectives, they cannot be compared directly to obtain the best control strategy possible.

5.1. Rule-Based Strategies

5.1.1. Fuzzy Logic

Fuzzy inference maps measured variables, such as, load, state of charge, DC-bus voltage, to set points through linguistic rules and membership functions, allowing intermediate truth values between 0 and 1 [

85]. In typical HESS rules, the FC supplies average demand at low battery SOC, while the battery supports higher load at high SOC [

86].

5.1.2. Filter-Based Power Splitting

Power is decomposed by frequency to exploit intrinsic device time scales: the FC supplies low-frequency or average power, the battery handles mid-frequency dynamics, and the supercapacitor covers high-frequency transients [

87,

88].

5.1.3. Finite-/Multi-State Logic

Operating modes, such as, charge-sustain, assist, boost, are defined by thresholds in SOC, load, and FC limits. Reported designs range from three coarse modes to more than ten states with detailed transitions [

89,

90,

91]. Hybrid schemes may switch between state logic and fuzzy control to select an FC current set-point while regulating battery SOC [

92].

5.1.4. GA-Tuned Fuzzy and Neuro-Fuzzy (ANFIS)

Metaheuristic tuning and neuro-fuzzy design strengthen rule-based EMS. Genetic algorithms adjust fuzzy membership and rule weights, lowering hydrogen use versus hand-tuned controllers [

93]. Adaptive Network-based Fuzzy Inference Systems (ANFIS) fuse neural learning with fuzzy inference, typically a five-layer structure (inputs, fuzzification, rule/combination, defuzzification, outputs), and can act as a supervisory layer over ECMS or inner loops. In [

94], an ANFIS-assisted ECMS for an FC–battery–ultracapacitor HESS reduced hydrogen consumption, improved efficiency, and lowered fuel-cell stress compared with PI control, frequency-decoupling fuzzy logic, and standalone ECMS.

5.2. Optimization-Based Strategies

5.2.1. Equivalent Consumption Minimization Strategy (ECMS)

ECMS minimizes an instantaneous equivalent fuel cost that combines FC hydrogen use and battery power via an equivalence factor. Simple feedback, such as, PID maintains SOC around a reference. ECMS commonly outperforms basic state logic in hydrogen usage for comparable constraints. This optimization strategy is characterized by determining the power split with the minimization of the instantaneous fuel consumption. In these cases, not only the actual fuel cell consumption is considered but also the equivalent fuel consumption of the battery. In some publications, this strategy is implemented with a PID and aims to reduce hydrogen consumption and, at the same time, increase the lifetime and decrease its stress.

5.2.2. Dynamic Programming (DP)

DP discretizes state and control to compute a globally optimal trajectory for a specified cycle, frequently with hydrogen consumption as the principal term in the cost [

95]. Due to computational cost and preview requirements, DP serves primarily as a benchmark.

5.2.3. Pontryagin’s Minimum Principle (PMP)

PMP casts energy management as choosing the control that minimizes a local “Hamiltonian” cost at each instant. The cost, an internal signal tied to e.g. SOC, plays the role of a time-varying equivalence factor between fuel and battery. In real time, its dynamics are approximated or learned and updated online, so the controller continuously adjusts the split between FC and battery, like adaptive ECMS but grounded in an optimality framework with consistent handling of terminal SOC targets [

96]. Constraints (currents, voltages, ramp limits) are enforced via projection or penalties, with filters/hysteresis to avoid chattering. Compared to fixed-factor ECMS, PMP tracks long-horizon objectives better across varying drive cycles while staying lightweight for embedded use [

97].

5.2.4. Model Predictive Control (MPC)

MPC solves receding horizon optimization with explicit constraints on currents, ramp rates, SOC bounds, and thermal limits. Linear or convex (LP/QP) MPC favors embedded deployment; nonlinear MPC captures detailed device dynamics; economic MPC optimizes operational cost, such as, hydrogen and electricity tariffs. Explicit MPC can pre-compute policies for fast runtime.

5.2.5. Convex/QP and Mixed-Integer Programming

When models are linearized or convexified, LP/QP delivers fast solutions with certificates of optimality. Mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) is useful for co-optimizing discrete decisions (start/stop, operating modes, batch timing in desalination) with continuous power flows [

98].

5.2.6. Other Metaheuristics

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Differential Evolution (DE), and Simulated Annealing (SA) seek high-quality solutions without requiring convexity. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is an optimization method in which a population of particles explores the search space by updating position and velocity from randomized initial states to improve an objective function. Owing to its stochastic nature, PSO typically yields high-quality solutions but does not guarantee global optimality. A quantum-behaved variant (QPSO) replaces the classical position–velocity update with a probabilistic position update derived from a wavefunction, which enhances global search capability. Comparative studies on HESS objectives, e.g., hydrogen production rate, hydrogen utilization efficiency, and cost, often report that QPSO outperforms classical PSO under the same constraints and test conditions [

99].

5.2.7. Robust and Stochastic Optimization

Uncertainty in renewable generation, load, and FC efficiency can be addressed via robust (set-based) or stochastic (chance-constrained, scenario-based) formulations, including robust/stochastic MPC, to maintain feasibility and performance under forecast errors [

100].

5.2.8. Degradation-Aware Optimization

Degradation-aware optimization adds wear-related costs or constraints, so the EMS minimizes lifetime cost rather than energy alone. For fuel cells, penalties target current slew/ripple, high current density, start–stop cycling, and elevated temperature; for batteries, they target temperature, C-rate, depth-of-discharge/SOC window, dwell, and throughput. These terms can be cast as convex penalties, soft/chance constraints, or adaptive equivalence factors and implemented in ECMS, MPC, or DP; MPC can also co-optimize thermal control. Calibration relies on simple stressor models or data-driven surrogates with online state-of-health updates, yielding policies that preserve efficiency while extending component life [

101].

5.3. Learning-Based Strategies

5.3.1. Reinforcement Learning (RL)

RL learns a policy mapping states (load, SOC, temperature, device limits) to actions (power split) by maximizing a long-horizon reward that combines efficiency, cost, and degradation. Representative methods include tabular Q-learning/SARSA for low-dimensional settings and deep actor–critic (e.g., DDPG/TD3, SAC) for continuous control. Safe or constrained RL enforces limits through Lagrangian methods or safety layers; model-based RL improves sample efficiency. RL can tune ECMS equivalence factors or MPC terminal terms online for adaptation to drift and aging [

102].

5.3.2. Supervised Learning

Policies can be trained to mimic optimal trajectories produced by DP or MPC, enabling near-optimal real-time decisions with minimal computation, provided the operating domain is well covered by the training data [

103].

5.4. Distributed and Cooperative Control

5.4.1. Consensus-Based Control

Agents, such as FC, battery, supercapacitor, or subsystems, update local set-points using neighbor exchanges to agree on shared variables such as DC-bus power or marginal cost. Convergence is achieved under standard connectivity assumptions with modest communication [

104].

5.4.2. Distributed Optimization (ADMM)

A global objective (cost, hydrogen usage, degradation) is decomposed into local subproblems solved in parallel with coordination steps. This approach is suitable for microgrids and desalination plants with geographically dispersed assets [

105].

5.4.3. Multi-Agent MPC

Multi-agent MPC uses local MPC controllers that solve coupled receding-horizon problems and exchange limited information, such as, set-point proposals, marginal costs, or multipliers) to satisfy network-level constraints [

106]. Coordination is implemented via consensus penalties, primal–dual schemes, or ADMM, with synchronous or asynchronous updates and warm starts. Stability is addressed through terminal costs/constraints; short horizons and simplified local models reduce computation. Hierarchical variants place device-level MPC under a slower economic coordinator, preserving data privacy while approaching centralized performance at lower communication and compute load [

107].

5.5. Selection Guidelines

Forecast quality determines controller choice: long-horizon or economic MPC and DP are advantageous when reliable predictions of load, renewables, and prices are available, because they exploit temporal coupling, whereas ECMS, fuzzy control, and short-horizon MPC operate effectively with limited preview by relying on current measurements. Implementation constraints also matter: rule-based schemes and convex LP/QP formulations have predictable runtime and are suitable for embedded deployment, while nonlinear MPC and deep reinforcement learning can improve performance at the cost of higher computation, tuning effort, and additional safeguards to ensure stability and constraint satisfaction. Under forecast uncertainty or parameter drift due to aging, robust or stochastic MPC maintains feasibility by modeling uncertainty explicitly, and safe RL introduces constraint handling during learning and execution; in all cases, incorporating degradation metrics, such as, current slew, temperature, SOC window, throughput) protects fuel-cell and battery health. A practical architecture combines a fast inner loop—PI/PID, fuzzy, or explicit MPC, for regulation with a slower supervisory layer, ECMS, MPC, RL, or a metaheuristic, that updates set-points or parameters, balancing responsiveness and optimality. For batch or flexible desalination loads, MILP or economic MPC can co-optimize production timing and energy cost while enforcing fuel-cell warm-up and ramp limits and battery SOC bounds, enabling coordinated water–energy operation with reduced operating cost and component stress.

6. Discussion

Advancing desalination's sustainability requires technological innovation to overcome key operational challenges. Concurrently, the energy supply must transition from fossil fuels to renewables. While the increased integration of renewable sources is vital, it introduces challenges of power supply reliability and energy efficiency due to their inherent intermittency, as previously discussed in

Section 1 and

Section 2.

As detailed in previous sections, hybrid energy storage system consisting of batteries and fuel cells can offer a promising solution to the intermittency of renewable energy sources like solar and wind. These natural fluctuations can create a mismatch, causing low energy availability precisely when desalination demand is high. A hybrid battery-fuel cell system bridges this gap by storing excess energy during peak production and discharging it during low generation, ensuring a continuous and reliable power supply.

These systems are more reliable and efficient than heterogeneous setups because they strategically combine different characteristics of Li-ion battery chemistries and fuel cells, to optimize overall performance. As it was shown in

Section 3, LFP batteries are well-suited for powering desalination equipment due to their respectable lifespan, relatively high specific power, low cost, and good thermal resistance. Even though their drawback includes low specific energy for most of the stationary applications of desalination plants it is a minor issue. As shown in

Section 4, fuel cells are uniquely positioned to provide a consistent, long-duration energy source, ensuring a stable power supply for desalination plants during extended periods of low renewable generation. Unlike batteries, which are ideal for managing fast fluctuations but become costly for long-term storage, fuel cells operate continuously as long as fuel is supplied. This steadiness is critical for processes like RO, as it allows them to run under stable power and pressure conditions, thereby reducing membrane stress and improving overall system uptime.

The synergy within a hybrid LFP battery-fuel cell system is fundamental to its efficiency. This configuration creates a strategic division of advantageous characteristics: the high-power LFP batteries manage rapid, second-to-second variations in renewable supply and load demand, while the high-energy fuel cell operates at a steady, efficient set-point to cover the baseload. This synergy is further enhanced by the cogeneration potential of fuel cells, the thermal energy they produce as a by-product can be used to preheat feedwater or drive low-temperature thermal desalination processes, adding another layer of efficiency.

By intelligently managing the energy flow between these complementary technologies, the hybrid energy storage system not only guarantees a reliable power supply but also significantly reduces the energy losses and operational inefficiencies typical of traditional, non-integrated desalination methods. As detailed in

Section 5, the integration of an EMS is critical for unlocking the full potential of hybrid battery-fuel cell storage in desalination. By intelligently controlling the power split between components, an EMS does not merely reduce energy losses, it actively optimizes the entire system for enhanced efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and longevity. The high-power responsiveness of batteries is seamlessly combined with the sustained, high-energy output of fuel cells, mitigating the inherent disadvantages of each technology when used alone.

Various EMS strategies achieve this, ranging from simple, real-time rule-based methods to complex optimization algorithms. For instance, Fuzzy Logic controllers effectively manage complementary operation, using the fuel cell when battery state-of-charge is low and relying on the battery when it is full. More advanced hybrid strategies, such as Genetic Algorithms combined with Fuzzy Logic or ANFIS, have been shown to significantly improve outcomes. Research indicates these approaches can minimize hydrogen consumption by optimizing control parameters in real-time.

Furthermore, optimization-based strategies like ECMS directly target and minimize instantaneous fuel use, while methods like swarm particle optimization search for the most efficient power distribution profiles. The overarching finding is that a sophisticated EMS of a hybrid battery-fuel cell storage, moves beyond simple energy loss reduction. It delivers a comprehensive performance enhancement, leading to lower operational costs, extended system lifespan, and a more reliable and sustainable water production process by ensuring each component operates within its optimal range.

5. Conclusions

This paper provides a comprehensive review of hybrid battery-fuel cell energy storage systems integrated with renewable energy for desalination technologies. The analysis, drawing from over 100 publications spanning 2004 to 2025, assesses the status of both established and emerging technologies, study findings, and the application of traditional and innovative approaches in the field, with a specific emphasis on system composed from lithium-ion batteries and fuel cells.

The principal findings of this research highlight the benefits of hybrid energy storage systems, especially hybrid battery-fuel cell systems. These systems provide a coordinated solution to manage renewable energy intermittency, maximize desalination effectiveness, and lessen environmental footprints. Furthermore, the paper emphasizes the critical role of cutting-edge control and optimization strategies. Evidence from recent studies indicates that advanced control, optimization, and energy management techniques significantly improve hybrid energy storage system controllability, thereby ensuring optimal renewable energy driven desalination plant performance. The review also covers new developments in control systems based on artificial neural networks. By leveraging hybrid battery-fuel cell energy storage and advanced control strategies, these systems can achieve greater energy efficiency, environmental sustainability, and economic viability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.G.; methodology, J.L.D.-G. and L.T.; investigation, L.G., H. P. G. and P.A.; writing—review and editing, L.G., H. P. G. and P.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“This research was funded by the European Union, grant number 101216330. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Executive Agency (REA). Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. This work was also supported by the Spanish Government through the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación under the PID2024 programme for the VAIANA project, grant number PID2024-163090OB-I00.”

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADMM |

Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers |

| AEM |

Anion-Exchange Membranes |

| AFC |

Alkaline Fuel Cells |

| AGM |

Absorbent Glass Mat |

| ANFIS |

Adaptive Network-based Fuzzy Inference Systems |

| ANN |

Artificial Neural Network |

| BESS |

Battery Energy Storage System |

| BHS |

Battery–Hydrogen Storage |

| CEM |

Cation-Exchange Membranes |

| DC |

Direct Current |

| DE |

Differential Evolution |

| DoD |

Depth of Discharge |

| DP |

Dynamic Programming |

| ECMS |

Equivalent Consumption Minimization Strategy |

| ED |

Electrodialysis |

| EDR |

Electrodialysis Reversal |

| EMS |

Energy Management System |

| ERD |

Energy Recovery Devices |

| ESS |

Energy Storage System |

| FC |

Fuel Cell |

| FLA |

Flooded Lead-Acid |

| FLC |

Fuzzy Logic Control |

| FO |

Forward Osmosis |

| GO |

Graphene-Oxide |

| HESS |

Hybrid Energy Storage System |

| ICP |

Ion Concentration Polarization |

| LFP |

Lithium Iron Phosphate |

| LTO |

Lithium Titanate Oxide |

| MCFC |

Molten Carbonate Fuel Cells |

| MED |

Multi-Effect Distillation |

| MG |

Microgrid |

| MPC |

Model Predictive Control |

| MSF |

Multi-Stage Flash |

| MVC |

Mechanical Vapor Compression |

| NCA |

Nickel Cobalt Aluminum |

| NMC |

Nickel Manganese Cobalt |

| PAFC |

Phosphoric Acid Fuel Cells |

| PEMFC |

Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells |

| PID |

Proportional-Integral-Derivative |

| PMP |

Pontryagin’s Minimum Principle |

| PV |

Photovoltaic |

| PSO |

Particle Swarm Optimization |

| QPSO |

Quantum Particle Swarm Optimization |

| RES |

Renewable Energy Sources |

| RL |

Reinforcement Learning |

| RO |

Reverse Osmosis |

| SED |

Shock Electrodialysis |

| SOC |

State of Charge |

| SOFC |

Solid Oxide Fuel Cells |

| SWRO |

Seawater Reverse Osmosis |

| TVC |

Thermal Vapor Compression |

| VFD |

Variable Frequency Drives |

| VRLA |

Valve-Regulated Lead-Acid |

| WT |

Wind Turbine |

References

- National Ocean Service. Available online: https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/wherewater.html (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation. Water for Life: Making it Happen. World Health Organization. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/43224 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Yang, S.-R.; Chen, X.-R.; Huang, H.-X.; Yeh, H.-F. Innovation in Water Management: Designing a Recyclable Water Resource System with Permeable Pavement. Water 2024, 16, 2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Vicidomini, M.; Calise, F.; Duić, N.; Østergaard, P.A.; Wang, Q.; da Graça Carvalho, M. Review of Hot Topics in the Sustainable Development of Energy, Water, and Environment Systems Conference in 2022. Energies 2023, 16, 7897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, E.; Estrela, T.; Lora, J. Desalination in Spain. Past, Present and Future. La Houille Blanche 2019, 105, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasoudi, S.; Jamoussi, B. Desalination Technologies and Their Environmental Impacts: A Review. Sustain. Chem. One World 2024, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IWA. Desalination–Past, Present and Future. Available online: https://iwa-network.org/desalination-past-present-future/ (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Desalination in the context of global water security. Available online: https://onewater.blue/article/desalination-in-the-context-of-global-water-security-10629f3f (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- European Commission and the European Environment Agency, Climate-ADAPT, Desalination. 2023. Available online:. Available online: https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/en/metadata/adaptation-options/desalinisation (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Liyanaarachchi, S.; Shu, L.; Muthukumaran, S.; Jegatheesan, V.; Baskaran, K. Problems in Seawater Industrial Desalination. Processes and Potential Sustainable Solutions: A Review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2014, 13, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Domínguez-García, J.L.; Romero, L.T. Review on Solar Photovoltaic-Powered Pumping Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkov, L.; Kirpichnikova, I. Model of Solar Photovoltaic Water Pumping System for Domestic Application. In Proceedings of the 2021 28th International Workshop on Electric Drives: Improving Reliability of Electric Drives (IWED), Moscow, Russia, 27–29 January 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasoudi, M.; Hemida, H.; Sharifi, S. Offshore Energy Island for Sustainable Water Desalination—Case Study of KSA. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, R.P.; Fajardo, A.; Lara-Borrero, J. Decentralized Renewable-Energy Desalination: Emerging Trends and Global Research Frontiers—A Comprehensive Bibliometric Review. Water 2025, 17, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, W.; Machorro-Ortiz, A.; Jerome, B.; Naldoni, A.; Halas, N.J.; Dongare, P.D.; Alabastri, A. Decentralized Solar-Driven Photothermal Desalination: An Interdisciplinary Challenge to Transition Lab-Scale Research to Off-Grid Applications. ACS Photon. 2022, 9, 3764–3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.W.; Burhan, M.; Ang, L.; Ng, K.C. Energy-water-environment nexus underpinning future desalination sustainability. Desalination 2017, 413, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengel Gálvez, R.M.; Caparrós Mancera, J.J.; López González, E.; Tejada Guzmán, D.; Sancho Peñate, J.M. Application of Electric Energy Storage Technologies for Small and Medium Prosumers in Smart Grids. Processes 2025, 13, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, R.; Ramos, F.; Pinheiro, A.; Junior, W.d.A.S.; Arcanjo, A.M.C.; Filho, R.F.D.; Mohamed, M.A.; Marinho, M.H.N. Case Study of Backup Application with Energy Storage in Microgrids. Energies 2022, 15, 9514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Cai, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Yan, N.; Ma, S. Research on Optimal Allocation Method of Energy Storage Considering Supply and Demand Flexibility and New Energy Consumption. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 4th Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Wuhan, China, 30 October–1 November 2020; pp. 4368–4373. [Google Scholar]

- Shively, D.; Gardner, J.; Haynes, T.; Ferguson, J. Energy Storage Methods for Renewable Energy Integration and Grid Support. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Energy 2030 Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–18 November 2008; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1334680/europe-battery-storage-capacity/ (accessed on 7 September 2025).