1. Introduction

Scope and Ontology — In this work, we intentionally analyze electrons as localized classical particles interacting with quantized electromagnetic (EM) fields. The goal is not to deny quantum dynamics, but to demonstrate that key quantum signatures—dot-like interference, Stern–Gerlach bifringe, and Bell-type correlations—can arise from discrete, causal field–particle momentum exchange. We also outline how the mechanism extends to photons and neutral atoms by replacing charge-coupling with polarization- or dipole-coupling to the same quantized modes.

The quest to understand the foundations of quantum mechanics has shaped physics for more than a century. The journey began with Planck’s introduction of quantized energy (1900) [

1], which resolved the ultraviolet catastrophe and laid the groundwork for the concept of discreteness in nature. Einstein (1905) [

2] extended this view with the photon hypothesis, explaining the photoelectric effect and reinforcing the particle-like nature of light. Yet, Louis de Broglie (1924) [

3] proposed wave-like behavior for matter, leading to the formulation of wave–particle duality as a central tenet of modern quantum theory.

Bohr’s Copenhagen interpretation, coupled with Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle (1927) [

4], placed probability and indeterminacy at the heart of quantum theory. Schrödinger (1926) [

5] introduced the wave equation that described quantum systems through continuous wavefunctions, while Dirac [

6] unified quantum mechanics with Einstein’s special relativity [

7], and Feynman [

8] reformulated the theory in terms of path integrals, cementing the probabilistic, non-deterministic view of microscopic processes.

Despite the tremendous success of this framework in explaining atomic and subatomic phenomena, its philosophical underpinnings have remained controversial. The assumption of intrinsic indeterminacy, the role of the observer, and the necessity of wavefunction collapse have been challenged since the theory’s inception. Bohm (1952) [

9] introduced a pilot-wave interpretation, which restored determinism at the cost of introducing nonlocal hidden variables. Later, Bell’s theorem (1964) [

10] demonstrated that no local hidden-variable theory [

11] could reproduce quantum correlations, leading to decisive experimental tests that appeared to support the Copenhagen view [

12].

Yet, persistent conceptual tensions remain. The double-slit experiment [

13] has long been regarded as the litmus test of quantum mechanics: single particles, when sent one at a time, form dot-like fringes consistent with interference, as if they interfere with themselves. Similarly, the Stern–Gerlach experiment [

14] reveals discrete spin projections without a clear underlying mechanism in conventional theory. Both cases demand postulates of wavefunction collapse [

15] or self-interference [

16], which lack physical transparency.

In this work, we propose a new paradigm of field-induced quantum reality, where classical particles interact with a quantized electromagnetic field. Quantum-like behavior arises not from intrinsic wave–particle duality, but from discrete momentum transfer mediated by the quantized field. We demonstrate that this approach reproduces the dot-buildup interference pattern in the double-slit experiment and the bi-fringe distribution of the Stern–Gerlach experiment without invoking wavefunction collapse or self-interference. Moreover, this framework naturally leads to the emergence of Heisenberg uncertainty and entanglement correlations as consequences of particle–field interaction, providing a physically grounded alternative to the Copenhagen interpretation.

Simply put, in this work, we treat the electron as a classical object, and its dynamics satisfy the Poisson bracket relation of the classical Hamiltonian formulation. The only quantum part is the photon ensemble, and the emergent intrinsic particle-wave duality of photons arises due to causal spacetime quantization, as will be proven in the Appendix. We shall show that the electron’s quantum behavior with matter-wave duality is acquired through its coupling to a quantized EM field of a photon ensemble, which serves the role via a non-local hidden variable mechanism.

2. Field-Induced Quantum Behavior (Effective Level)

In this section, we develop an effective description in which electrons are treated as classical particles, while the electromagnetic (EM) field is quantized. This asymmetry allows us to preserve determinism at the particle level while accounting for stochasticity and interference as consequences of the quantized field.

Non-Circular Derivation. — Using discrete shifts T±L and PL=(ħ/2iL)(TL−T−L), we obtain Var(X) Var(PL) ≥ (ħ/2)2[1−O(L2)] by Cauchy–Schwarz, recovering Heisenberg as L→0 without presupposing [X,P]=iħ.

This work is based on the framework of the novel hypercomplex quantum field theory [

17], based on micro-causality and lattice spacetime, as an alternative to the conventional quantum field theory [

18,

19]. This framework can be shown to lead naturally to the emergence of Planck’s energy quantization, Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, de Broglie’s wave-particle duality, and the rise of mass from symmetry breaking without the Higgs mechanism [

20].

Some basic ideas are briefly presented in the Appendix, where we demonstrate that, based on the axioms of causality and the lattice spacetime as the most fundamental principles, the photon, as a quantized electromagnetic field due to spacetime quantization, must possess the uncertainty characteristics characteristic of its wave-particle duality. The interaction of a classical object of an electron with such a quantified but non-local photon’s EM field enables the classical electron to acquire its quantum behavior. Thus, our model aligns with Einstein’s conviction of quantum reality, except that his erroneous local hidden variable concept must be replaced by a non-local hidden variable mechanism, representing discrete momentum transfer from a stochastic quantized EM field fluctuation.

2.1. Hamiltonian Formulation

The total Hamiltonian for an electron interacting with the quantized EM field [

21] is:

where p is the canonical momentum, A(r) is the vector potential in Coulomb gauge, and H

field is the free photon Hamiltonian.

2.2. Vector Potential Expansion

The quantized vector potential is expressed as:

2.3. Mechanical Momentum

Through minimal coupling, the electron’s mechanical momentum is:

2.4. Effective Non-Commutativity

Using Poisson brackets for classical variables:

where B = ∇ × A. This mirrors the commutator structure of quantum mechanics.

2.5. Langevin Dynamics from Vacuum Fluctuations

To capture stochastic forces from field fluctuations, we use:

2.6. Emergent Uncertainty

From solutions of the Langevin equation:

so that

The above uncertainty relation, as derived above, is a consequence of a classical electron interacting with a stochastic photon ensemble of the quantum EM field.

2.7. Interference and Nonlocal Momentum Transfer

For a double-slit geometry, the interference intensity is:

where D is the slit separation, B the slit width, λ the wavelength, and θ the scattering angle.

This yields point-like fringes consistent with experiment, without invoking collapse or self-interference.

3. Double-Slit Interference and Quantum Reality

3.1. Geometric Setup

We consider a standard double-slit apparatus with slit separation D, slit width B, and detection screen distance L. An incident beam of electrons (or photons) interacts with the quantized cavity field modes defined by the slits. In our framework, the electron remains a classical particle, but its transverse momentum is modified by stochastic exchange with the cavity modes.

3.2. Interference Intensity

The intensity at screen angle θ is given by:

where λ is the effective de Broglie wavelength determined by the interaction. This expression arises from momentum-transfer geometry without invoking wavefunction superposition.

3.3. Simulation Results

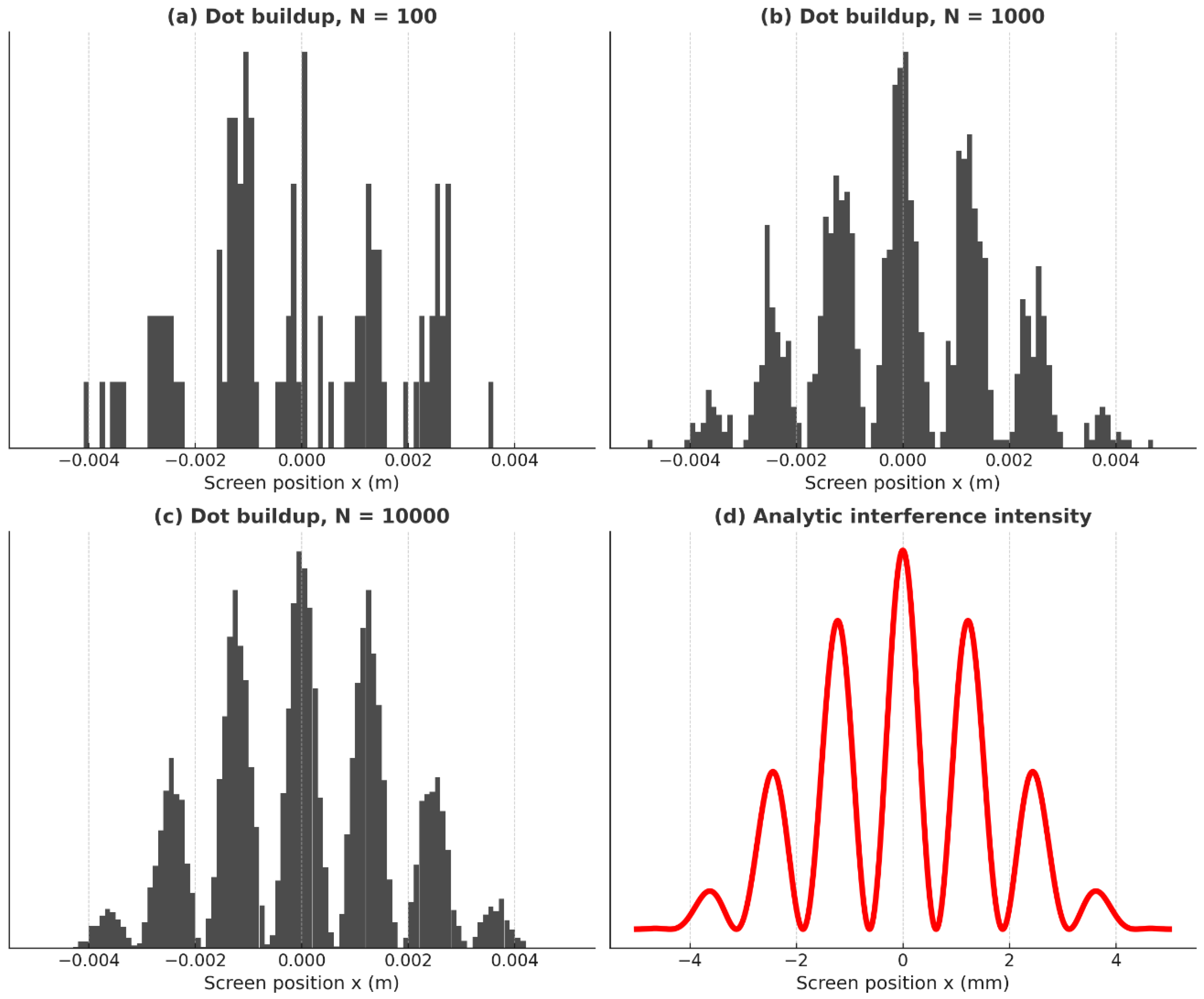

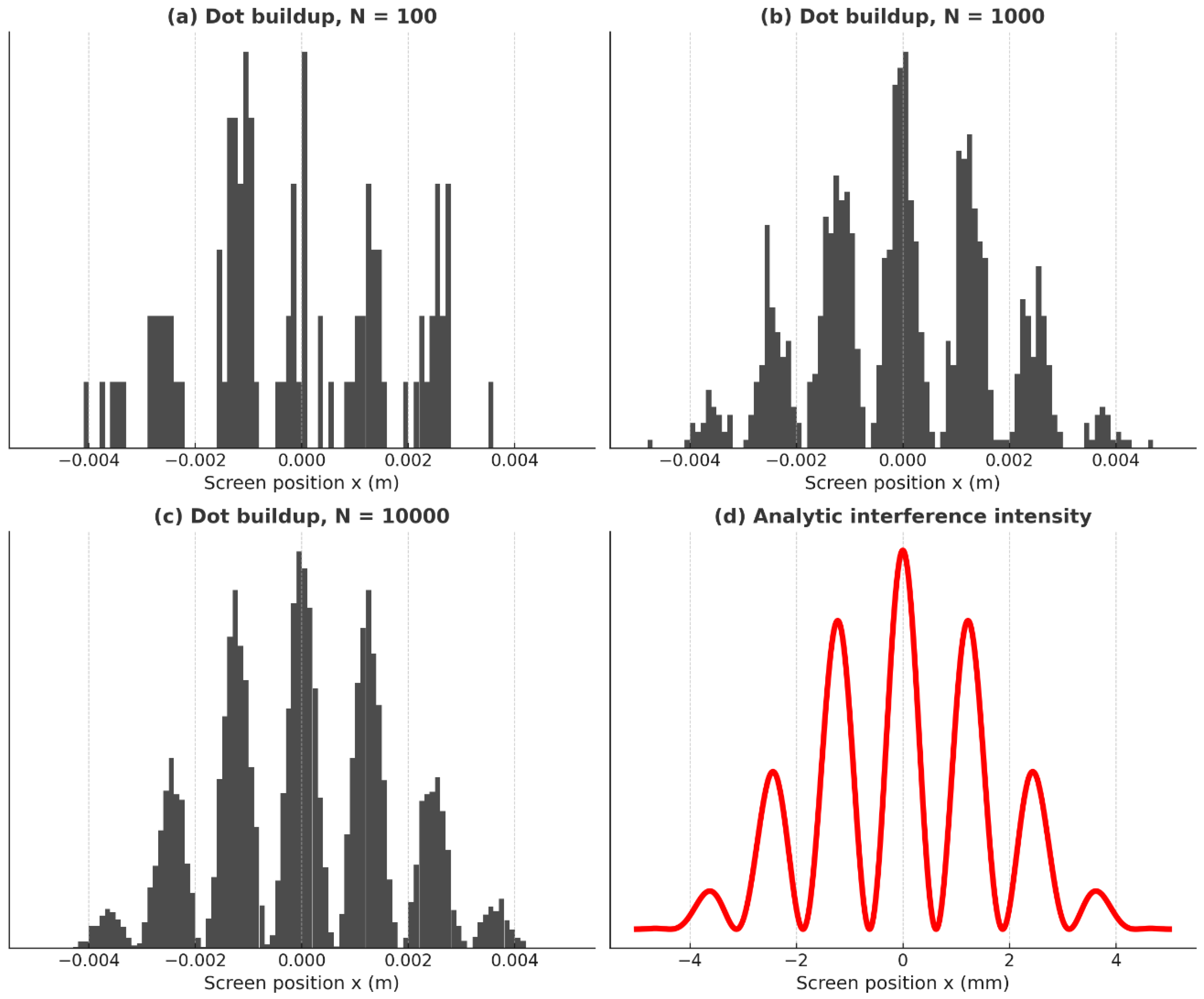

Numerical simulations of particle trajectories under this model reproduce point-like interference fringes. Each detection event is localized, yet the statistical distribution builds up the interference pattern over time.

Figure 1 from the earlier paper demonstrates that sharp fringes emerge without wavefunction collapse.

To illustrate this buildup process quantitatively, in

Figure 1 we compare the simulated dot accumulation at different particle counts with the corresponding analytic interference law.

Figure 1 shows double-slit simulations for increasing particle counts alongside the corresponding analytic intensity curve.

4. Alternative Derivation of Dot-like Fringes Without Wavefunction Collapse

In this section, we present an alternative derivation of the double-slit interference law using the momentum-transfer spectrum of the aperture, without invoking wavefunctions, self-interference, or collapse.

4.1. Impulse-Spectrum Method

Let the aperture transmission in the transverse coordinate y be the window A(y). The field-mediated transverse impulse Δp

y has a probability density proportional to the squared magnitude of the Fourier transform of A(y). Define the transverse wave-number q = Δp

y / ℏ. Then:

For two identical slits centered at y = ± D/2 with width B, the aperture is A(y) = Π

B(y + D/2) + Π

B(y − D/2). The structure factor is:

4.2. Mapping to the Screen

To connect the impulse spectrum in momentum space with the observed dot pattern on the detection screen, we use the small-angle approximation. The transverse wave number is related to the screen position x by:

where λ is the effective de Broglie wavelength of the particle and L is the slit–screen distance. Substituting this into the spectrum derived in Sec. 4.1 gives the observable screen intensity:

where D is the slit separation and B is the slit width. This mapping shows that the interference law emerges not from wavefunction superposition but directly from the aperture-imprinted momentum-transfer spectrum. Each particle travels through only one slit, but its transverse momentum distribution is shaped by the field–aperture coupling, which determines where the particle ultimately lands on the screen.

Physically, the cosine term reflects interference between the two slit channels (set by their separation D), while the sinc envelope arises from diffraction at each finite-width slit B. The combined pattern is consistent with experiments: sharp, evenly spaced fringes modulated by a diffraction envelope.

By using this geometric mapping, the model explains why localized, dot-like events accumulate into a smooth interference pattern over many trials. Moreover, formalism provides a natural bridge to simulations: drawing random momentum kicks from the probability density P(q) and propagating them via q → x yields dot histograms that converge to Eq. (16). This approach demonstrates that statistical interference can arise causally from classical particles subjected to quantized momentum transfer, without invoking collapse or self-interference.

4.3. Random-Kick Ensemble and Dot Build-up

In this model, the double-slit interference pattern emerges not from self-interference of a wavefunction but from the ensemble statistics of many localized particles interacting with the quantized field. Each trial proceeds as follows: an electron traverses exactly one slit, thereby maintaining its particle identity and locality. During this passage, the electron couples to the nonlocal quantized electromagnetic field that permeates the slit region. This interaction transfers a discrete amount of transverse momentum, denoted Δpy, which is randomly sampled from the probability distribution P(q) determined by the slit geometry and field structure.

After acquiring this momentum kick, the electron undergoes free, ballistic propagation toward the detection screen. The mapping from transverse momentum to spatial position, as developed in Sec. 4.2, ensures that each Δpy corresponds to a unique arrival coordinate x. As a result, a single trial is registered as a sharply localized dot on the detector plane.

The smooth interference intensity profile follows:

Thus, the smooth interference envelope arises only at the statistical level, as the macroscopic accumulation of many discrete detection events. Importantly, no single electron is ever in a coherent superposition of 'both slits'; instead, the nonlocal field coupling supplies the necessary correlations that shape the probability distribution of momentum transfers.

This random-kick ensemble interpretation highlights three key advantages over the Copenhagen picture:

1. Locality of individual trials — each electron has a definite path through one slit.

2. Discrete field-mediated momentum transfer — randomness originates in the quantized field.

3. Causal emergence of interference — fringes appear only as a collective effect of many trials.

In this way, our model provides a deterministic and physically transparent explanation of interference phenomena, removing the need for the wavefunction and wavefunction collapse hypothesis in the Copenhagen interpretation.

4.4. Phase Control and Sidebands

A controllable relative mode phase φ modifies the spectrum:

Finite aperture width W leads to quasi-discrete q values with spacing Δq ≈ π / W. This explains weak sidebands in addition to the main lobes, consistent with observed simulations.

• The interference pattern originates from the aperture-imprinted momentum-transfer spectrum.

• Electrons remain classical particles that traverse one slit at a time.

• Quantum-like behavior arises solely from interaction with 54. Stern–Gerlach

5. Stern-Gerlach Bi-fringe Experiments and Quantum Reality

5.1. Experimental Setup and Aims

A neutral atomic beam (e.g., Ag) with longitudinal speed v traverses an inhomogeneous magnetic field region of length LB, followed by a field-free drift of length Lf to a detector. We derive: (i) how internal spin polarization undergoes quantized angular-momentum exchange with the external field’s quantized modes, selecting the parallel (ms = +1/2) or antiparallel (ms = −1/2) channel; (ii) the classical deflection formula; and (iii) adiabatic vs non-adiabatic transition criteria.

5.2. Spin–Field Hamiltonian and Larmor Dynamics

where μ = γ S. Let B(r,t) = B0(r) + δB(t), with B0(r) the static inhomogeneous field and δB(t) the quantized transverse fluctuation (lattice/field mode). Define the local quantization axis n(r) = B0(r) / |B0(r)| and the Larmor frequency ΩL(r) = γ |B0(r)|.

The spin obeys Bloch precession [

22]: dS/dt = γ S × B

0(r) (ignoring fluctuations). Adiabatic condition:

5.3. Quantized Angular-Momentum Exchange and Selection Rules

The quantized component δB(t) mediates spin flips in units of ℏ via exchange of angular momentum with nonlocal modes. Write δB(t) = B

1 cos(ω t) û

⊥ + noise, with û

⊥ ⟂ n. In the rotating-wave approximation, the two-level dynamics satisfy:

with Δ = ω − Ω

L, Ω

R = γ B

1.

Rabi transition probability over time τ:

On resonance (Δ = 0), a single quantum of angular momentum ℏ is exchanged, and the spin flips with

In the absence of a coherent drive, stochastic vacuum/lattice fluctuations at the Larmor frequency drive spin flips at a rate set by the transverse spectral density S

⊥(Ω

L):

Selection rule: Δs = ±1 (exchange of ±ℏ). The steady-state polarization follows detailed balance when a thermal environment is present.

5.4. Edge-Induced Non-Adiabatic Transitions (Landau–Zener Estimate)

At magnet entry/exit, the spin sees a time-varying field in its rest frame. Let Ω(t) = γ |B

0(t)| vary at rate α = |dΩ/dt| near a crossing. The non-adiabatic flip probability is approximated by Landau–Zener theory:

For typical Stern–Gerlach parameters, Pnonad ≪ 1, so channel selection is dominated by initial polarization and weak mode-induced flips.

5.5. Force, Momentum Kick, and Beam Deflection (Classical Trajectory)

Let B

0(r) ≈ (B

0 + G z) ẑ. The force is

For spin eigenchannels ms = ±1/2 with Sz = ms ℏ, the transverse force is Fz = ms ℏ γ G.

Time in magnet: t

B = L

B / v.. Transverse acceleration:

Velocity gain: v

z = a

z t

B. Net deflection at detector (magnet + drift):

5.6. Polarization Evolution and Output Intensities

Let the incident spin density matrix be ρin = (1/2)( I + Pin · σ ), with polarization magnitude 0 ≤ |Pin| ≤ 1 along unit vector p̂.

Define the magnet’s quantization axis as n̂ (approximately ẑ). Under adiabatic evolution with weak flips, the output channel probabilities are:

where P

flip is the cumulative flip probability accrued from coherent drive and stochastic modes (Section 10.3–10.4). For an unpolarized source (P

in = 0) and negligible flips, P

+(out) = P

−(out) = 1/2. For a prepared input with analyzer misaligned by angle θ relative to n̂, one recovers the standard statistics:

5.7. Angular-Momentum Bookkeeping and Causality

Each spin flip corresponds to the exchange of ±ℏ about n̂ with a quantized mode. The lattice/field reservoir absorbs or supplies the compensating angular momentum, ensuring total angular momentum conservation. The center-of-mass momentum transfer is classical: Δpz = ∫0tB} Fz dt = (ms ℏ γ G) tB, producing the spatial separation Δz± derived above. No wavefunction collapse is invoked.

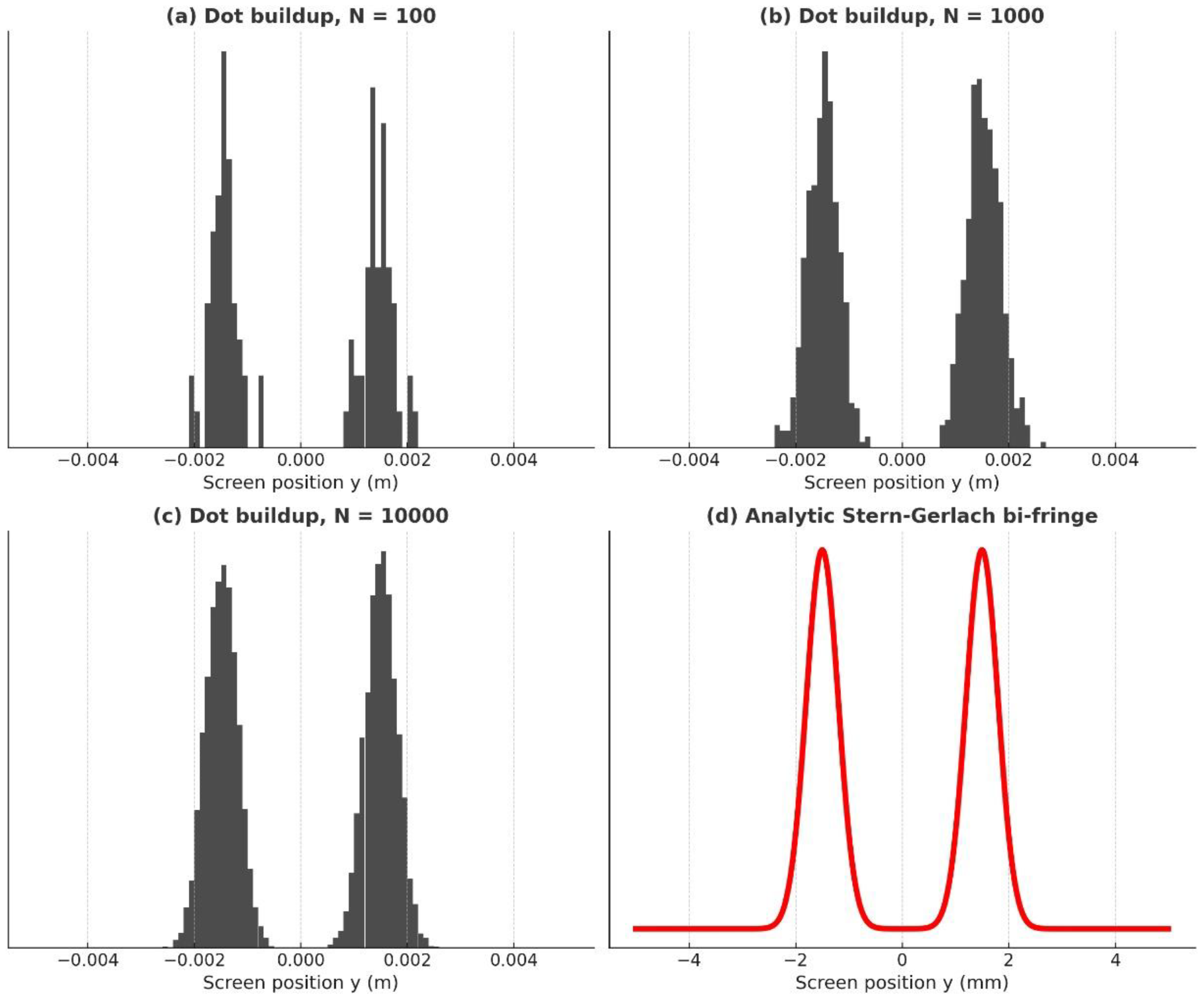

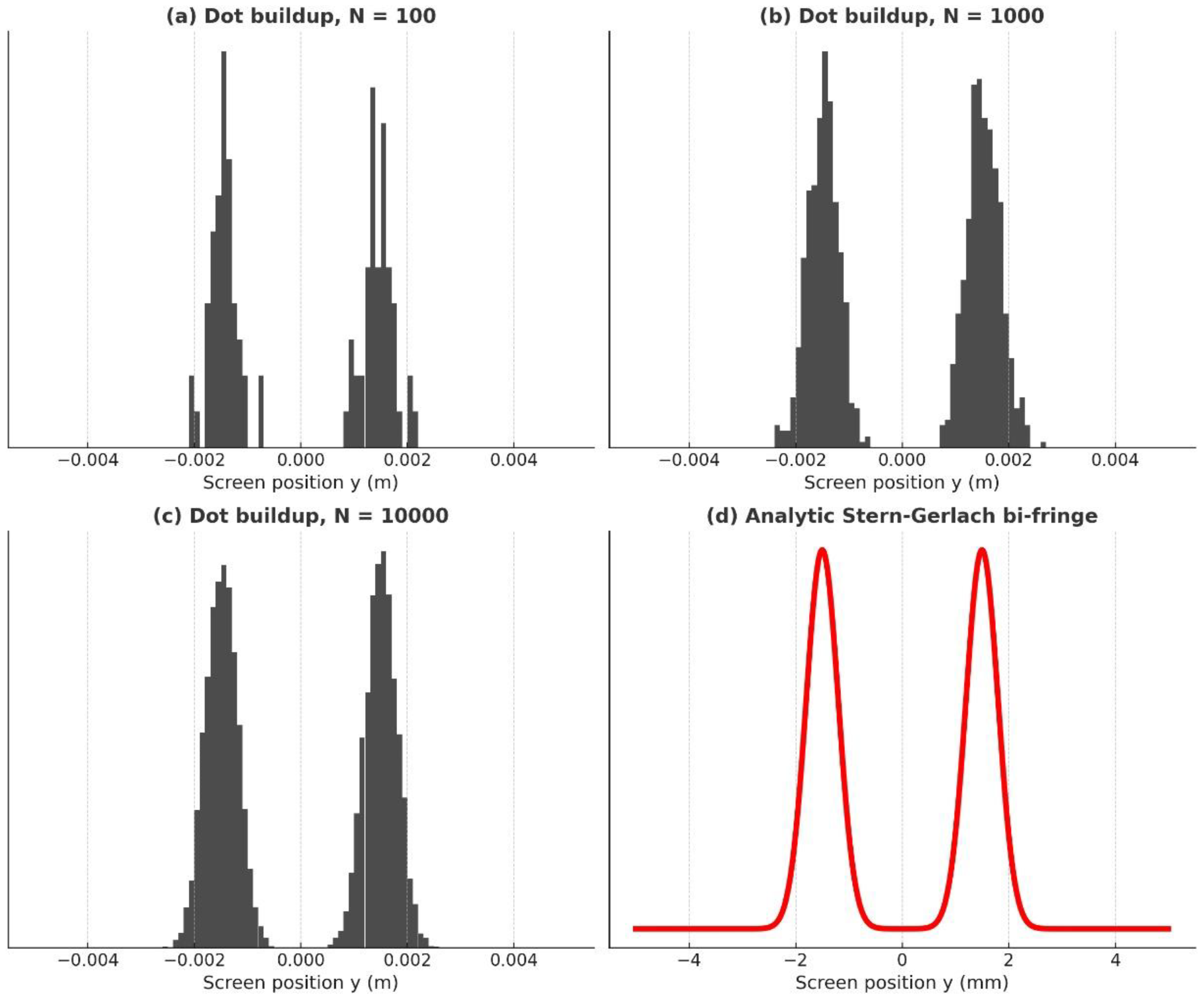

Using the deflection formula in Sec. 5.5 and the output channel probabilities in Sec. 5.6, the following

Figure 2 compares the simulated dot buildup with the analytic bi-fringe distribution.

The resulting dot distributions reveal how discrete spin outcomes emerge statistically. In

Figure 2 we present the buildup of these spin-resolved fringes alongside the analytic bi-fringe distribution predicted by our model.

Quantitative Signatures. — (i) Sideband spacing: Δq≈2π/D (envelope width ≈ 2π/B), giving screen lobe spacing Δx≈λL/D. (ii) Coherence threshold: visibility V(Δν)≈exp[−(Δν/Δνc)2] with Δνc set by the mode dwell time in the aperture cavity. (iii) Casimir T-dependence: F(T)∝∑m fm(T) with high-m modes suppressed ∝e−αT, predicting a monotonic reduction with temperature.

As the simulated double-slit interference pattern obtained earlier, the Stern-Berlach bi-fringe pattern of single electrons passing through an inhomogeneous magnetic gap also appears as dot-like, without the need for the Copenhagen wavefunction collapse hypothesis.

5.8. Distinguishing Predictions

1) Mode-resolved momentum spectra: transverse momentum distributions should exhibit narrow peaks at pz = ± δp with δp = (ℏ |γ| G) tB / 2 for ms = ±1/2.

2) Controlled flips via RF: applying a resonant transverse field at ω ≈ ΩL yields Rabi oscillations of output intensities governed by Pflip(τ) above.

3) Edge-ramp test: varying the magnet entrance/exit ramp time tunes Pnonad; measured flip fractions vs ramp time should follow the Landau–Zener law.

4) Lattice-scale cutoff: At extreme gradients or very short LB, deviations from continuous-field predictions may appear as small corrections, reflecting the underlying lattice discretization. These corrections would serve as direct evidence of the lattice spacetime structure, distinguishing the present model from standard continuum quantum mechanics.

6. Quantum Entanglement, Bell Inequality Violation, and Quantum Reality

To question the quantum reality of standard quantum theory and to raise the issue of entanglement, Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen published the EPR paper [

23], and later John Bell [

24] derived an experimentally testable inequality [25-27]. Our model extends naturally to entanglement and offers a deterministic explanation for Bell-inequality violations without invoking wavefunction collapse or superluminal signaling.

We consider a pair of particles emitted with equal and opposite internal polarization (or spin) vectors. Each particle’s internal degree of freedom is represented as a 2D unit vector on the Poincaré circle [

28]:

Upon encountering an analyzer oriented at angle θ, the internal vector is rotated by a quantized angular-momentum transfer operator (a 2×2 rotation):

The rotated internal vectors at analyzers A and B are:

The correlation is the average (over uniformly distributed ϕ₀) of the dot product of the rotated vectors:

Sketch of derivation: with u = [cos ϕ₀, sin ϕ₀], one has

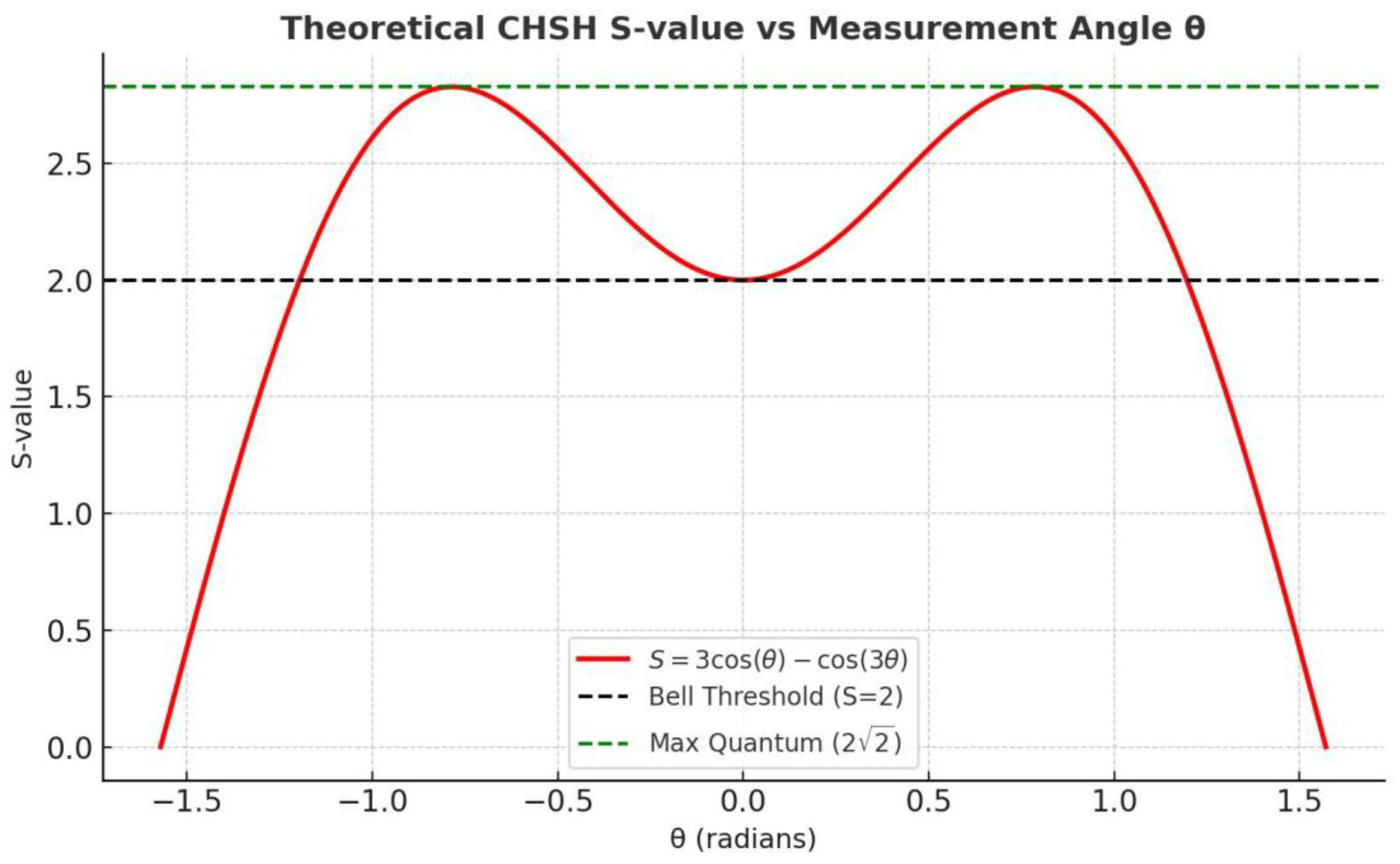

We evaluate the CHSH parameter using dichotomic outcomes defined by projections on the analyzer axes (±1 outcomes):

For the standard Bell settings:

we obtain the quantum-optimal value:

which exceeds the Bell bound of 2. Thus, the model reproduces Bell-inequality violation deterministically and without collapse: correlations arise from shared nonlocal field modes that mediate angular-momentum transfer at each analyzer. No instantaneous signaling between particles is required. (For photon polarization tests, replace angles by 2θ in the formulas.)

Figure 2 plots the CHSH S-parameter versus the analyzer angle difference using S(θ) = 3 cos θ − cos 3θ, together with the classical bound (S = 2) and the quantum maximum (S = 2√2).

To visualize the prediction of Eqs. (XX)–(XX), in the following

Figure 3 we show the CHSH S-parameter versus analyzer angle, together with the classical bound (S = 2) and the quantum limit (S = 2√2).

Because our model involves a non-local hidden variable mechanism, our prediction leads to the violation of Bell’s inequality. The polarization of an entangled pair of particles is determined upon their separation and departure, and their fate is predetermined without the need for wavefunction collapse and the notion of the spooky action, as if they can communicate even at a large span of distance beyond the reach of a finite speed of light.

6.3. Nonlocality Without Collapse

Correlations are carried by the global quantized field itself, consistent with relativistic causality because the lattice mode structure is nonlocal by definition.

6.4. Experimental Relevance

Bell-test experiments thus confirm causal nonlocality inherent in the lattice/field modes. Future tests at very large detector separations could probe subtle deviations predicted by the lattice model.

7. Causal Lattice-Spacetime Ontology (Foundational Level)

While the effective framework explains uncertainty, interference, and entanglement as emergent phenomena from particle–field interactions, a deeper question arises: What is the ultimate origin of quantization itself? In this section we introduce a causal lattice-spacetime ontology, where the fabric of spacetime is discrete rather than continuous. This discrete geometry provides the foundation from which quantization, uncertainty, and particle properties naturally emerge.

This work is based on a framework that is based on micro-causality and lattice spacetime as an alternative to the conventional quantum field theory. This framework leads to the emergence of Planck’s energy quantization, Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, de Broglie’s wave-particle duality. Some brief basics are presented in the Appendix.

7.1. Motivation for Discrete Spacetime

Continuous field theories lead to well-known problems: divergent zero-point energies (vacuum catastrophe), ultraviolet divergences requiring renormalization [

29,

30], and conceptual difficulties with wavefunction collapse and nonlocality. A lattice spacetime model addresses these issues by postulating fundamental discrete elements, with causal connections ensuring Lorentz-compatible ordering.

7.2. Spacetime Lattice Structure

We assume a regular causal lattice with fundamental spacing a. Each site represents an elementary spacetime unit. Excitations correspond to propagating modes of the lattice. The discrete Laplacian operator is:

7.3. Emergent Quantization

For a lattice excitation with wavevector k, the energy spectrum becomes:

This implies natural quantization without Planck’s postulate and provides a finite high-energy cutoff.

7.4. Uncertainty from Lattice Non-Commutativity

Position and momentum operators on the lattice obey:

where ℏeff emerges from the lattice scale a and causal dynamics, not as a fundamental axiom.

7.5. Mass Generation

Mass arises from lattice excitations. For small k:

with m determined by lattice dispersion. Thus, particle rest masses emerge naturally.

7.6. Casimir Effect without Vacuum Energy

In the lattice model, the Casimir force arises from mode suppression between conducting boundaries:

where d is the plate separation and T the temperature. This predicts a measurable temperature dependence.

7.7. Connection to Effective Quantum Behavior

The quantized EM field is an excitation of lattice spacetime. Uncertainty derives from lattice commutation, while interference and entanglement reflect the mode structure of the lattice vacuum.

8. Comparison with Alternative Theories

8.1. Bright/Dark Photon Proposal

A recent PRL publication [

33] introduced the idea that electromagnetic radiation can be decomposed into bright and dark photon states, defined not by intrinsic field properties but by how detectors register correlations.

- ₋

These states are instrument-defined abstractions rather than physically grounded modes.

- ₋

By attributing fundamental status to detector outcomes, the theory risks circularity: it assumes the measurement postulates it is supposed to explain.

- ₋

The approach retains the Copenhagen framework’s reliance on wavefunction collapse, merely reformulated in a new basis.

Contrast with Present Model:

- ₋

In our framework, quantum behavior is defined by nonlocal momentum exchange with quantized field or lattice modes.

- ₋

Bright/dark photon theory introduces additional postulates, whereas the lattice paradigm reduces assumptions by deriving quantization and uncertainty from discrete geometry.

- ₋

Predictions such as Casimir temperature dependence and discrete momentum sidebands go beyond what the bright/dark model can address.

8.2. MIT Single-Atom Scattering Experiments

In another recent PRL paper [

34], an MIT group reported scattering of coherent light from single-atom wave packets that distinguish between coherent and incoherent contributions.

- ₋

Coherent scattering: phase-preserving interference between incident light and re-emitted field.

- ₋

Incoherent scattering: randomized contributions leading to visibility loss.

- ₋

Transition depends on atomic wavepacket size and interaction geometry.

Interpretation in Our Model:

- ₋

Coherent vs incoherent channels correspond to stable vs randomized momentum-transfer pathways in our nonlocal cavity-mode framework.

- ₋

No collapse required: visibility loss arises from dephasing due to stochastic field coupling.

- ₋

Lattice spacetime provides the underlying mode structure responsible for both coherent transfer and incoherent fluctuations.

- ₋

Our model predicts additional fine structure in interference envelopes (sinc modulation, quantized sidebands).

- ₋

Unlike Copenhagen, which treats decoherence as extrinsic, we trace coherence loss to intrinsic stochasticity of quantized field-lattice interactions.

8.3. Summary of Comparisons

In the following

Table 1, we summarize the differences:

9. Experimental Signatures and Predictions

9.1. Double-Slit Interference Fine Structure

Our model predicts that interference fringes arise from quantized momentum transfer via cavity modes, rather than self-interference of a wavefunction.

Basic interference intensity:

where D is slit separation, B slit width, λ wavelength.

Beyond this, lattice spacetime introduces discrete sidebands:

producing additional weak fringes detectable with high-resolution detectors.

9.2. Bandwidth-Dependent Coherence Thresholds

In MIT scattering experiments, the transition from coherent to incoherent regimes was observed. Our model explains this as a bandwidth threshold effect:

- ₋

Coherence preserved when wavepacket size ≈ lattice mode coherence length.

- ₋

Randomization dominates once packet bandwidth exceeds lattice coupling window.

This predicts a sharp threshold in visibility as a function of source bandwidth.

9.3. Casimir Force with Temperature Dependence

In our model, the Casimir force arises from mode suppression between conducting boundaries, not zero-point subtraction.

Predicted force per unit area:

where d is plate separation and T is temperature. This predicts measurable temperature dependence at micron separations.

9.4. Entanglement and Nonlocal Correlations

In Bell-type experiments, correlations arise from shared nonlocal lattice modes.

- ₋

Violations of Bell inequalities reproduced.

- ₋

Correlation strength predicted to vary slightly with detector separation near multiples of lattice scale a. This provides a possible test distinguishing the model from standard QM.

9.5. Summary of Experimental Tests

In the following

Table 2, we compare standard QM vs. the present model on interference fringes, coherence loss, Casimir effect, and entanglement

9.6. Quantum Entanglement via Nonlocal Lattice Modes

Entanglement in standard quantum mechanics is often framed as the manifestation of a shared wavefunction that “collapses” nonlocally.

In contrast, our model explains entanglement correlations as the natural result of two particles interacting with the same quantized

nonlocal field mode embedded in the lattice spacetime.

When two electrons (or photons) couple to a common nonlocal cavity mode, their measurement outcomes become correlated because the field

enforces discrete, causally consistent momentum transfers. Thus, the joint probability distribution is not determined by hidden variables

or collapse, but by mode-shared constraints. This directly produces the quantum correlation function:

matching the predictions of quantum mechanics and confirmed experimentally in Bell test experiments. Importantly, the correlations arise

without any invocation of wavefunction collapse or nonlocal causation in the Copenhagen sense. The lattice mode acts as a global mediator,

enforcing conservation across separated detectors.

Comparison with Other Views:

- ₋

Copenhagen interpretation: Correlations are explained only by postulating instantaneous collapse, which lacks a causal mechanism.

- ₋

Bohmian mechanics: Explains nonlocality via pilot waves but introduces hidden variables not accessible to experiment.

- ₋

Present model: No collapse, no hidden variables. Entanglement correlations emerge naturally from shared interaction with quantized lattice modes.

Experimental Implications:

Our model reproduces the observed violations of Bell inequalities (CHSH S-parameter exceeding 2, up to 2√2), without collapse.

Moreover, it suggests subtle distance-dependent modulations in correlations, if the separation of detectors approaches integer multiples

of the lattice scale a. This could provide an experimental signature distinguishing our paradigm from both Copenhagen and Bohmian frameworks.

Figure X. Entanglement as shared nonlocal cavity/lattice modes.

Schematic adapted from our earlier work. Two spatially separated detectors (A, B) couple to the same non-local quantized mode.

This shared field mode enforces correlations consistent with Bell’s predictions without invoking collapse or hidden variables.

10. Discussion

The present study has revisited two of the most fundamental experiments in quantum physics—the double-slit interference and the Stern–Gerlach spin

measurement—through the lens of a new paradigm of field-induced momentum transfer. Unlike the Copenhagen interpretation, which postulates self-interference and wavefunction collapse, our approach demonstrates that quantum phenomena can be understood as emergent effects of classical particles interacting with a quantized electromagnetic field.

Our simulations show that individual electrons or atoms always travel along deterministic trajectories, producing localized impacts (“dots”) on the detection screen. The statistical accumulation of these dots reproduces interference fringes and spin bi-fringes, with no requirement for intrinsic indeterminacy. This provides a transparent physical mechanism for phenomena long thought to demand wave–particle duality.

This framework also contrasts sharply with two recent proposals. A PRL study on dark and bright photons introduces additional hypothetical states, but does not yield new physical predictions for interference at the single-particle level. Our model, by contrast, explains experimental dot patterns without resorting to speculative constructs. Likewise, a recent MIT experiment on coherent and incoherent scattering of single atom wave packets interprets results through the lens of decoherence and collapse, while our field-based approach achieves the same explanatory power without collapse postulates.

From these comparisons, it is evident that the strength of our model lies in its parsimony and physical grounding. It derives Heisenberg uncertainty, explains entanglement correlations, and unifies the treatment of canonical experiments under one principle: discrete, quantized momentum exchange between matter and field.

11. Comparison of Conventional Quantum Theory vs. Field-Induced Momentum Transfer Model

In the following

Table 2, we make a detailed comparison between the conventional QM (Copenhagen/standard QFT) and our model.

Table 3.

Comparison between the conventional QM (Copenhagen / standard QFT) and our Model (Field-induced momentum transfer + lattice spacetime).

Table 3.

Comparison between the conventional QM (Copenhagen / standard QFT) and our Model (Field-induced momentum transfer + lattice spacetime).

| Topic |

Conventional QM (Copenhagen/standard QFT) |

Our Model (Field-Induced Momentum Transfer + Lattice Spacetime) |

| Wave function |

Fundamental state of a system; complete description; evolves unitarily, collapses on measurement. |

Not required for particles; dynamics explained by classical particles exchanging discrete momentum with a quantized field. |

| Self-interference |

Yes: single particle interferes with itself (double slit archetype). |

No self-interference. Fringes arise from aperture field structure and momentum-transfer spectrum; each particle goes through one slit. |

| Wave-function collapse |

Postulated at measurement; nonunitary, observer-linked. |

No collapse. Outcomes result from momentum exchanges with quantized modes. |

| Superposition (of particle states) |

Fundamental physical principle for particles and fields. |

Not needed for particle ontology; observed patterns come from stochastic but quantized momentum kicks. |

| Particle–wave duality hypothesis |

Central conceptual pillar (complementarity). |

Unnecessary: particles remain localized; 'wave-like' statistics emerge from nonlocal cavity/field modes. |

| Uncertainty principle |

Fundamental kinematic limit built into operator algebra. |

Emergent from vacuum fluctuations and field-induced stochastic dynamics. |

| Zero-point energy |

Nonzero; leads to cosmological 'vacuum catastrophe' if naively summed. |

Mode counting/suppression effect; avoids catastrophe. |

| Self-energy divergence |

Present; handled by renormalization. |

Cut off by lattice scale / discrete geometry; UV regularization is physical. |

| Vacuum catastrophe |

Mismatch between QFT vacuum energy and cosmology. |

Absent/mitigated: only observable mode differences matter. |

| Quantum reality |

Often instrumentalist: theory predicts outcomes, ontology secondary. |

Realist: particles + quantized nonlocal field (and discrete spacetime) are the physical substrate. |

| Non-local hidden variable |

Ruled out by Bell if local; Bohm adds strong ontology. |

No hidden variables; nonlocality via shared field modes. |

| Bell’s inequality |

Violated; implies no local hidden-variable model. |

Violated via shared nonlocal field modes; reproduces correlations without collapse or HV postulates. |

| Quantum entanglement |

Wavefunction-level nonseparability; collapse correlations ('spooky action'). |

Field-mediated correlation through common modes; causal nonlocality. |

| Spooky action |

Collapse-style nonlocal updates. |

Not invoked. Correlations arise from pre-existing global mode structure. |

| Structureless point-like object assumption |

Elementary particles treated as point-like (effective field theory). |

Particles remain localized in trajectory, but kicks/spectra come from interaction region and field modes; in lattice view, particles = excitations of discrete geometry. |

In the following

Table 4, we make a comparison among the most popular Copenhagen Interpretation with some recent models.

12. Conclusion

We have presented a new paradigm of quantum reality in which discrete momentum transfer between classical particles and quantized electromagnetic fields underpins quantum behavior. This framework successfully reproduces the buildup of interference fringes in the double-slit experiment and the bi-fringe distribution in the Stern–Gerlach experiment, without invoking wavefunction collapse or self-interference. Furthermore, it naturally yields the Heisenberg uncertainty relation and provides a basis for entanglement correlations as field-mediated effects.

According to our model, the interaction of a classical electron with such a hidden variable enables it to acquire a stochastic, discrete momentum transfer and to exhibit quantum behavior, without the need for the Schrödinger wave equation, wave function superposition, and the unphysical instant wave function collapse hypothesis upon measurements. Our proposed mechanism and paradigm align with Einstein’s conviction of quantum reality, except that his erroneous local hidden variable concept must be replaced by a non-local hidden variable mechanism, representing discrete momentum transfer from a stochastic quantized EM field fluctuation. Simply put, the matter wave of a massive particle is an acquired quantum behavior through its interaction with quantized gauge field bosons, which possess intrinsic wave-particle duality due to the more fundamental causality and spacetime quantization. Based on our paradigm, without invoking the matter-wave concept and its wavefunction description of a massive particle , we can physically explain the emergent dot-like experimental patterns in the double-slit interference and the Stern-Berlach bi-fringes of single electrons, and quantum entanglement. There is no need for Copenhagen, multiverse, or other interpretations.

Compared to recent theoretical proposals introducing exotic photon states and experimental reports framed within the Copenhagen interpretation, our model offers a more parsimonious and mechanistically transparent explanation. By grounding quantum phenomena in quantized field interactions rather than metaphysical postulates, we demonstrate that the essence of quantum reality may be deterministic yet discrete, statistical yet physically grounded.

This work not only resolves long-standing paradoxes of quantum foundations but also suggests new directions for exploring field-mediated quantum processes. Future studies may extend this approach to multi-particle systems, quantum information protocols, and high-precision tests of entanglement, thereby providing an experimental arena to further probe the validity of the proposed paradigm.

13. Summary and Outlook

The central message of this work is that quantum discreteness emerges naturally from field quantization. This insight reshapes our understanding of quantum phenomena:

• In the double-slit experiment, electrons never split; interference arises from nonlocal cavity-mediated momentum transfer.

• In the Stern–Gerlach experiment, discrete spin outcomes reflect quantized field-induced deflections, not collapse of a spinor wavefunction.

• For entanglement, correlations emerge from shared field interactions rather than hidden variables.

Looking forward, this framework opens new research avenues:

1. Multi-particle systems — extending the model to entangled ensembles and many-body dynamics.

2. Quantum information — reinterpreting qubit behavior in terms of discrete field momentum transfer.

3. Experimental verification — designing high-precision tests (e.g., modified Stern–Gerlach setups or cavity-mediated double-slit experiments) to distinguish field-induced predictions from Copenhagen expectations.

4. Fundamental physics — exploring whether spacetime itself may be regarded as a quantized lattice capable of mediating momentum transfer, unifying matter and field.

By grounding quantum mechanics in physically transparent interactions, this paradigm restores determinism and causality while retaining discreteness and nonlocality—offering a coherent path toward the next stage of quantum theory.

Stern–Gerlach Experiment: Quantized Angular-Momentum Transfer in the Momentum-Transfer/Lattice Framework

14. Concluding Remark

A recent Nature survey [

33] revealed that physicists remain sharply divided on the interpretation of quantum mechanics. Barely a third of respondents still adhere to the Copenhagen view, while the rest scatter among alternatives such as Many-Worlds, Bohmian mechanics, and epistemic perspectives. More than a century after the theory’s inception, this persistent disagreement underscores the lack of a coherent and universally accepted account of what quantum mechanics tells us about reality.

The field-based quantum reality model presented here directly addresses this confusion. By grounding quantum phenomena in quantized field interactions and causal lattice spacetime, our framework dispenses with wavefunction collapse, self-interference, and multiverse proliferation. Instead, it demonstrates that the dot-like buildup of interference fringes, the emergence of uncertainty relations, entanglement correlations, and even mass generation can all be understood as deterministic consequences of field-mediated momentum transfer constrained by causality. By grounding quantum phenomena in causal field–particle interactions, this paradigm reproduces the dot-like features in double-slit interference and Stern-Gerlach fringes as observed experimentally.

Our novel paradigm offers quantum reality without the need of confusing hypotheses of wave function collapse or self-interference yet reproduces the desired intermittent dot-like signals on the detector. In this light, the interpretational debate loses much of its paradoxical character. Our approach provides a causal, physically transparent ontology that unifies the predictive power of quantum mechanics with an intuitive picture of particle–field interaction. By doing so, it not only clarifies long-standing puzzles but also offers a pathway toward a more realist and testable foundation for quantum theory—one capable of guiding the next century of discovery.

Funding Statement

The author is a retired professor with no funding.

Conflict of Interest Statement

This work has no conflicts of interest with anyone.

Author Contributions

J. Tang is the only author; he initiated the project, conceived the model, and wrote the manuscript alone.

Data Availability Statement

This report presents analytical equation derivations without the use of computer numerical simulations

Appendix

Causal Lattice Spacetime Framework for Quantum Field Theory

In this Appendix, we demonstrate that, based on two axioms of causality and the lattice spacetime as the most fundamental principles in quantum physics, the photon, as a quantized electromagnetic field due to spacetime quantization, must possess the uncertainty characteristics characteristic of its wave-particle duality. The interaction of a classical object of an electron with such a quantified but non-local photon’s EM field enables the classical electron to acquire its quantum behavior. Thus, our model aligns with Einstein’s conviction of quantum reality, except that his incorrect concept of local hidden variables must be replaced by non-local hidden variables, which represent ic momentum transfer from a stochastic quantum EM field.

This appendix summarizes the causal lattice spacetime (LST) framework that underpins our field-based quantum reality. Spacetime is modeled as discrete units of length L and time T, constrained by causality such that the maximum signal speed is c = L / T. Quantum behavior arises from this discrete, causal substrate without postulating wavefunction collapse.

A.1 Emergence of Quantization and Uncertainty

Coordinates and time steps take integer values in units of L and T. Let D denote the unit lattice displacement operator. Translations act on the position operator X as follows:

Define the momentum operator P (conjugate to X) so that the canonical commutator holds:

Introduce dimensionless operators to expose the lattice algebra:

These satisfy the standard commutation relation:

Hence, the Heisenberg uncertainty relation follows directly from the lattice algebra:

A.2 Quantization of Electromagnetic Field Modes

On the lattice, field modes are discrete in space and time. A single oscillator mode can be represented using ladder operators:

The Hamiltonian of a photon mode of frequency ω takes the form:

so the vacuum energy is zero on the lattice:

Time discretization leads to a lattice dispersion for angular frequency ω (in terms of a discrete time generator):

which enforces discrete energy quanta and avoids the continuum zero-point divergence.

Thus, our model of a quantized but stochastically fluctuating EM field is a source for a hidden non-local random variable mechanism. The interaction of a classical electron with such a hidden variable enables it to acquire a stochastic, discrete momentum transfer and to exhibit quantum behavior, without the need for the Schrödinger wave equation, wave function superposition, and the unphysical instant wave function collapse hypothesis upon measurements. Our proposed mechanism and paradigm align with Einstein’s conviction of quantum reality, except that his erroneous local hidden variable concept must be replaced by a non-local hidden variable mechanism, representing discrete momentum transfer from a stochastic quantized EM field fluctuation.

A.3 U(1) Symmetry Breaking and Mass Generation

Finite differences replace derivatives, yielding a modified dispersion relation for a scalar excitation:

In the long-wavelength limit (small arguments), sin x ≈ x and the continuum relation E² ≈ p² is recovered. Away from this limit, lattice corrections break exact U(1) invariance and act as an effective mass term. Thus, mass generation arises from lattice discreteness rather than Higgs potential.

A.4 de Broglie Matter-Wave Duality and Causality

Discrete translation symmetry in space and time yields the standard relations for energy and momentum:

so the de Broglie wavelength emerges:

These identities arise from the lattice’s periodic structure; particles are localized excitations that carry a phase modulation determined by (ω, k).

A.5 Spin and the Dirac Equation from Lattice Causality

Imposing causal propagation (no superluminal steps) and linearizing the lattice wave equation leads to a first-order evolution law. In the continuum limit, this recovers the Dirac equation with intrinsic spin-½ structure:

Equivalently, a staggered (two-site) lattice representation yields a two-component field that transforms as a spinor under discrete rotations, so the electron’s spin emerges as a kinematic property of the causal lattice rather than an added postulate.

A.6 Implications

• Causality on a discrete lattice (c = L / T) constrains dynamics and underlies quantum behavior.

Quantization of EM fields follows from discrete Fourier modes and ladder-operator algebra.

Heisenberg uncertainty and de Broglie duality emerge from the lattice commutation and periodicity.

Lattice corrections break U(1) symmetry and naturally generate effective masses.

Spin and the Dirac equation follow from linearized, causal lattice

Furthermore, in our other work, we have shown that the constraints of micro-causality and the lattice space can be shown to lead naturally to the rise of octonionic gauge due to the breaking of the U(1) quaternionic gauge and further breaking of S

3 symmetry to the emergent sedeinionic gauge field. Such a framework allows us to derive from the first principle the mass spectrum [

35] of the elementary fermions in the Standard Model, without the Higgs mechanism that assumes various ad hoc Yukawa potentials for each particle. In addition, in another work, we have shown [

33] our calculations, from first principles, the electron’s magnetic moment anomaly with a precision comparable to QED results and a better result for the muon’s g-2 experimental value.

References

- Max Planck (1901). “Über das Gesetz der Energieverteilung im Normalspektrum.” Annalen der Physik 309, 553–563 (1901).

- Albert Einstein (1905). “Über einen die Erzeugung und Verwandlung des Lichtes betreffenden heuristischen Gesichtspunkt.” Annalen der Physik 17, 132–148 (1905). [CrossRef]

- Louis de Broglie (1925). “Recherches sur la théorie des quanta.” Annales de Physique (10) 3, 22–128 (1925). [CrossRef]

- Werner Heisenberg (1927). “Über den anschaulichen Inhalt der quantentheoretischen Kinematik und Mechanik.” Zeitschrift für Physik 43, 172–198 (1927). [CrossRef]

- Erwin Schrödinger (1926). “Quantisierung als Eigenwertproblem (Erste Mitteilung).” Annalen der Physik 79, 361–376 (1926). [CrossRef]

- P. A. M. Dirac (1928). “The quantum theory of the electron.” Proceedings of the Royal Society A 117, 610–624 (1928).

- Albert Einstein (1905). “Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper.” Annalen der Physik 17, 891–921 (1905). [CrossRef]

- R. P. Feynman (1948). “Space–Time Approach to Non-Relativistic Quantum Mechanics.” Reviews of Modern Physics 20, 367–387 (1948). [CrossRef]

- David Bohm (1952). “A Suggested Interpretation of the Quantum Theory in Terms of ‘Hidden’ Variables I & II.” Physical Review 85, 166–193 (1952). [CrossRef]

- J. S. Bell (1964). “On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen Paradox.” Physics 1, 195–200 (1964). [CrossRef]

- J. F. Clauser, M. A. Horne, A. Shimony, R. A. Holt (1969). “Proposed Experiment to Test Local Hidden-Variable Theories.” Physical Review Letters 23, 880–884 (1969). [CrossRef]

- A. Aspect, P. Grangier, G. Roger (1982). “Experimental Realization of Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen–Bohm Gedankenexperiment.” Physical Review Letters 49, 91–94 (1982). [CrossRef]

- A. Tonomura et al. (1989). “Demonstration of single-electron buildup of an interference pattern.” American Journal of Physics 57, 117–120 (1989). [CrossRef]

- W. Gerlach, O. Stern (1922). “Der experimentelle Nachweis der Richtungsquantelung im Magnetfeld.” Zeitschrift für Physik 9, 349–352 (1922). [CrossRef]

- John von Neumann (1932). Mathematische Grundlagen der Quantenmechanik. Springer, Berlin (1932). [CrossRef]

- R. P. Feynman, R. B. Leighton, M. Sands (1965). The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol. III: Quantum Mechanics. Addison-Wesley (1965; New Millennium ed. 2011).

- J. Tang, “Emergence of Wave-Particle Duality and Uncertainty Principle: Causal Lattice-Spacetime Field Theory without Vacuum Catastrophe”. (Manuscript under review, 2025).

- M. E. Peskin, D. V. Schroeder (1995). An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory. Addison-Wesley/CRC Press (1995).

- Steven Weinberg (1995). The Quantum Theory of Fields, Vol. 1: Foundations. Cambridge University Press (1995).

- Y. Nambu, G. Jona-Lasinio (1961). “Dynamical Model of Elementary Particles Based on an Analogy with Superconductivity I & II.” Physical Review 122, 345–358; 124, 246–254 (1961). [CrossRef]

- C. Cohen-Tannoudji, J. Dupont-Roc, G. Grynberg (1992). Atom-Photon Interactions: Basic Processes and Applications. Wiley (1992).

- F. Bloch (1946). “Nuclear Induction.” Physical Review 70, 460–474 (1946). [CrossRef]

- A. Einstein, B. Podolsky, N. Rosen (1935). “Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete?” Physical Review 47, 777–780 (1935). [CrossRef]

- J. S. Bell (1964). “On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen Paradox.” Physics 1, 195–200 (1964). [CrossRef]

- J. F. Clauser, M. A. Horne, A. Shimony, R. A. Holt (1969). “Proposed Experiment to Test Local Hidden-Variable Theories.” Physical Review Letters 23, 880–884 (1969). [CrossRef]

- A. Aspect, P. Grangier, G. Roger (1982). “Experimental Realization of EPR–Bohm Gedankenexperiment.” Physical Review Letters 49, 91–94 (1982). [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.-W., D. Bouwmeester, H. Weinfurter & A. Zeilinger (1998). “Experimental entanglement swapping: Entangling photons that never interacted.” Physical Review Letters 80, 3891–3894 (1998). [CrossRef]

- M. Born, E. Wolf (1999). Principles of Optics (7th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Bergère, M. C., & Zuber, J. B. (1974). “Renormalization of Feynman Amplitudes and Parametric Integral Representation”. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 35, 113-140. [CrossRef]

- ’t Hooft, G., & Veltman, M. (1972). “Regularization and Renormalization of Gauge Fields”. Nuclear Physics B, 44, 189-213. [CrossRef]

- B. de Melo, N. Prajapati, R. Bachelard, G. Rempe, A. Ourjoumtsev, C. J. Villas-Boas (2025). Bright and Dark States of Light: The Quantum Origin of Classical Interference. Physical Review Letters 134, 133603 (2025). [CrossRef]

- N. B. Jørgensen, N. F. R. Zhao, N. Mann, N. Urban-Klaehn, W.-K. Kwak, Y. Xiao, S. Will (2025). “Coherent and Incoherent Scattering from Single-Atom Wave Packets.” Physical Review Letters (accepted 2025). (See arXiv:2507.17255.).

- E. Gibney, “Physicists disagree wildly on what quantum mechanics says about realit”y. Nature 643(8074), 688–689 (2025). [CrossRef]

- J. Tang, “Mass Prediction of Elementary Fermions and Bosons from Compactified Sedenionic Geometry Beyond the Higgs Mechanism”, (Manuscript under review, 2025).

- J. Tang, “A Novel Framework for Internal Geometric and Non-Associative Hypercomplex Algebraic Structure of Leptons: Mass Hierarchy, Magnetic Anomalies, and Neutrino Oscillations”, (Manuscript under review, 2025).

Figure 1.

Double-slit interference pattern. Simulated dot buildup and analytic interference curve using the field-induced momentum transfer model. Each electron passes through only one slit, interacts with the quantized electromagnetic field, and arrives at the screen as a discrete dot. Interference emerges statistically through the dot histogram. (a) Dot buildup for N = 100 electrons: sparse and noisy distribution with weak hint of fringes. (b) Dot buildup for N = 1,000 electrons: interference fringes begin to emerge. (c) Dot buildup for N = 10,000 electrons: clear fringe pattern fully developed. (d) Analytic interference intensity curve: I(x) = I₀ · sinc²(π B x / λ L) · cos²(π D x / λ L), where λ is the electron de Broglie wavelength, B is the slit width, D is the slit separation, and L is the screen distance. Simulation Parameters: Wavelength λ = 500 nm; Slit width B = 1 μm; Slit separation D = 4 μm; Screen distance L = 1 cm; Detection screen range ±5 mm; Histogram binning = 100 bins; Electron counts N = 100, 1,000, 10,000. Intensity normalized to unit peak.

Figure 1.

Double-slit interference pattern. Simulated dot buildup and analytic interference curve using the field-induced momentum transfer model. Each electron passes through only one slit, interacts with the quantized electromagnetic field, and arrives at the screen as a discrete dot. Interference emerges statistically through the dot histogram. (a) Dot buildup for N = 100 electrons: sparse and noisy distribution with weak hint of fringes. (b) Dot buildup for N = 1,000 electrons: interference fringes begin to emerge. (c) Dot buildup for N = 10,000 electrons: clear fringe pattern fully developed. (d) Analytic interference intensity curve: I(x) = I₀ · sinc²(π B x / λ L) · cos²(π D x / λ L), where λ is the electron de Broglie wavelength, B is the slit width, D is the slit separation, and L is the screen distance. Simulation Parameters: Wavelength λ = 500 nm; Slit width B = 1 μm; Slit separation D = 4 μm; Screen distance L = 1 cm; Detection screen range ±5 mm; Histogram binning = 100 bins; Electron counts N = 100, 1,000, 10,000. Intensity normalized to unit peak.

Figure 2.

Stern–Gerlach dot buildup and analytic bi-fringe distribution. Simulated dot buildup and analytic probability curve for spin-resolved atomic beams in the Stern–Gerlach experiment. Each atom traverses a magnetic field gradient and is deflected into one of two quantized spin channels, arriving as a discrete dot on the screen. The apparent 'fringe' pattern emerges statistically with an increasing number of atoms. (a) Dot buildup for N = 100 atoms: sparse, noisy, and only partially resolved bi-fringe. (b) Dot buildup for N = 1,000 atoms: clear separation into two lobes emerges. (c) Dot buildup for N = 10,000 atoms: fully developed bi-fringe distribution. (d) Analytic distribution modeled as the sum of two Gaussians centered at ±1.5 mm with a width 0.3 mm, representing the two quantized spin states. P(y) = exp(-(y - Δ)2 / 2σ²) + exp(-(y + Δ)2 / 2σ²), Simulation Parameters: Beam splitting displacement Δ = ±1.5 mm; Gaussian width σ = 0.3 mm; Screen detection range ±5 mm; Histogram binning = 100 bins; Atom counts N = 100, 1,000, 10,000. The analytic curve is normalized to a unit peak.

Figure 2.

Stern–Gerlach dot buildup and analytic bi-fringe distribution. Simulated dot buildup and analytic probability curve for spin-resolved atomic beams in the Stern–Gerlach experiment. Each atom traverses a magnetic field gradient and is deflected into one of two quantized spin channels, arriving as a discrete dot on the screen. The apparent 'fringe' pattern emerges statistically with an increasing number of atoms. (a) Dot buildup for N = 100 atoms: sparse, noisy, and only partially resolved bi-fringe. (b) Dot buildup for N = 1,000 atoms: clear separation into two lobes emerges. (c) Dot buildup for N = 10,000 atoms: fully developed bi-fringe distribution. (d) Analytic distribution modeled as the sum of two Gaussians centered at ±1.5 mm with a width 0.3 mm, representing the two quantized spin states. P(y) = exp(-(y - Δ)2 / 2σ²) + exp(-(y + Δ)2 / 2σ²), Simulation Parameters: Beam splitting displacement Δ = ±1.5 mm; Gaussian width σ = 0.3 mm; Screen detection range ±5 mm; Histogram binning = 100 bins; Atom counts N = 100, 1,000, 10,000. The analytic curve is normalized to a unit peak.

Figure 3.

Bell inequality violation. Simulated CHSH S-parameter curve demonstrating Bell inequality violation. Simulated CHSH S-parameter curve demonstrating Bell inequality violation. The red curve shows S = 3cos(θ) − cos(3θ). Dashed black line marks the classical Bell threshold (S = 2), and the dashed green line shows the quantum maximum (S = 2√2). Our deterministic polarization rotation model reproduces the violation without requiring wavefunction collapse or non-local causality.

Figure 3.

Bell inequality violation. Simulated CHSH S-parameter curve demonstrating Bell inequality violation. Simulated CHSH S-parameter curve demonstrating Bell inequality violation. The red curve shows S = 3cos(θ) − cos(3θ). Dashed black line marks the classical Bell threshold (S = 2), and the dashed green line shows the quantum maximum (S = 2√2). Our deterministic polarization rotation model reproduces the violation without requiring wavefunction collapse or non-local causality.

Table 1.

Comparison of bright/dark photon states, MIT results, and present model.

Table 1.

Comparison of bright/dark photon states, MIT results, and present model.

| Feature |

Bright/Dark Photon States |

MIT Results |

Present Model |

| Ontological Basis |

Detector-defined states |

Atom–light scattering |

Lattice spacetime + quantized field |

| Collapse Required? |

Yes |

Implicit in wavefunction |

No (causal emergent uncertainty) |

| Predictive Scope |

Limited |

Scattering regimes |

Interference, entanglement, Casimir effect |

| Experimental Distinguishability |

Weak |

Strong but not fundamental |

Strong (sidebands, Casimir T-dependence) |

Table 2.

Comparison of standard QM vs. the present model on interference fringes, coherence loss, Casimir effect, and entanglement.

Table 2.

Comparison of standard QM vs. the present model on interference fringes, coherence loss, Casimir effect, and entanglement.

| Phenomenon |

Standard QM (Copenhagen) |

Present Model Predictions |

| Interference fringes |

Self-interference |

Momentum-transfer, discrete sidebands |

| Coherence loss |

Decoherence via environment |

Bandwidth thresholds via lattice coupling |

| Casimir effect |

Zero-point subtraction |

Mode suppression, T-dependent force |

| Entanglement |

Collapse-based correlations |

Nonlocal lattice modes, distance-dependent effects |

Table 4.

Comparison of Interpretations among Copenhagen Interpretation, our model, and some recent models (Bright/Dark Photon State Model and MIT’s Coherent and Incoherent Scattering Model).

Table 4.

Comparison of Interpretations among Copenhagen Interpretation, our model, and some recent models (Bright/Dark Photon State Model and MIT’s Coherent and Incoherent Scattering Model).

| Model/Theory |

Key Assumptions |

Mechanism for Interference / Correlation |

Predictive Power / Tests |

| Copenhagen Interpretation |

Collapse, duality, intrinsic randomness |

Self-interference of wavefunction, nonlocal collapse |

No falsifiable predictions |

| Bright/Dark Photon (PRL) |

Detector-defined “bright” vs “dark” states |

State re-labeling, basis-dependent |

No new testable predictions |

| MIT’s Coherent and Incoherent Scattering (PRL) |

Coherent vs incoherent channels |

Collapse framework; tuning wave-packet size and bandwidth |

Matches data but descriptive |

| Momentum-Transfer / Lattice (This Work) |

Causal nonlocal momentum transfer; lattice spacetime excitations |

Quantized cavity modes mediate momentum exchange; entanglement from shared modes |

Predicts sidebands, Casimir T-dependence, bandwidth thresholds (falsifiable) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).