1. Introduction

In this report, we present a novel interpretation of double-slit interference based on quantized momentum transfer, offering a physically intuitive alternative to conventional wavefunction-based descriptions [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5] of quantum theory [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Unlike the standard Schrödinger wavefunction approach, which treats the double slit as a classical object and interference as the self-interaction of a single quantum particle’s wave packet, our model assigns a quantized spacetime structure to the slit geometry. This introduces discrete cavity modes that govern the particle’s interaction, resulting in a stochastic yet well-defined excitation process.

A key prediction of our model is that when the particle’s wavelength approaches the scale of a double slit with a sufficient gap width, the non-locality and discreteness of these cavity modes lead to deviations from the smooth continuum interference pattern expected in traditional quantum mechanics. This effect, arising purely from quantized momentum transfer, offers a testable signature requiring a highly coherent particle source and a stable slit structure. Additionally, our model naturally aligns with experimental violations of Bell’s inequality [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], reinforcing the non-local aspects of quantum mechanics without invoking Einstein’s hidden variables and questioning the quantum-mechanical description of physical reality [

17].

By explicitly incorporating a quantized mechanism for the double-slit interaction which has a nonlocal nature, our framework provides a deeper physical understanding of interference phenomena compared to interpretations such as Copenhagen, many-worlds, and Bohmian mechanics [

18,

19]. It not only preserves the realism Einstein advocated but also offers new insights into the interplay between quantum non-locality and spacetime structure, opens the door for further experimental verification.

2. Theory

In this section, we shall first present the Heisenberg’s operator approach to the double-slit interference without/with a finite slit width, and then the second-quantization’s creation and annihilation-operator approach for the treatment of the double-slit potential

2.1. Heisenberg’s Operator Approach to Double-Slit Interference with a Negligibly Small Slit Width

According to Heisenberg’s quantum operator formalism [

20,

21,

22], the Hamiltonian of a particle, say an electron in this report interacting with the potential of a double slit is given by

where

is the Dirac delta function. The above potential wall of the double slit represents

, and

vanishes elsewhere. According to Heisenberg’s matrix mechanics formalism, one has

where

Let us examine the trajectory of an electron initially at

before hitting the slit-wall at

. One has the impulsive force

and the impulsive action from the slit-wall is given by

If the potential energy

is much greater than the incident kinetic energy, quantum tunneling is not permissible and the electron is reflected. Therefore, the electron can only pass through the potential wall via the double slits.

The slit gap D is the fundamental length unit, and the fundamental mode has 1/2 wavelength equal to D so that the wave has nodes at the slits. The allowed discrete modes have a frequency as an integer multiple of the fundamental mode. One has the following relations between wavelength

of the fundamental cavity mode, wave vector

, and D as

As an electron passes through either slit, it gains a y-component momentum, proportional to

via absorbing or emitting a cavity quanta with the double-slit potential well, and a quantized field amplitude distribution

and a probability of

, which leads to the same probability distribution for the dot-like interference signal when the electron hits the detector.

The above results indicate that when an electron passes through either slit, it interacts with the double slit and receives a kick, representing a quantized momentum transfer

, from one of the cavity modes. This quantum of energy causes the electron to deflect from its original trajectory. As the deflected electron reaches the screen detector, it induces a dot signal. Each of the discrete multiple-mode force components in Eq. (4) leads to a different dot signal on the screen, and as time evolves with more electron counts, an interference pattern emerges. The amplitude distribution of the n

2-th mode is given by

. This value represents the field strength distribution of the cavity quanta, and its square represents the intensity or probability distribution of the cavity-mode quant. This leads to an interference pattern with an intensity proportional to

. The y-component momentum change after the electron passes through the top slit is given by

Accordingly, one has

where

, and the minimal Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle of

was used. Therefore, one has

From Eqs. (5A) and (5A) the deflected electron angles due to the n-th electron passing through the upper beam or the m-th electron of the lower beam are given by

Because of de Broglie’s duality hypothesis, a quantum particle possesses a dual component which can be represented by a complex-value distribution function, and the probability is the squared magnitude. Accordingly, the overall interference intensity from those upper- and lower-beam electrons is given by

where Eq. (5A) of

is used. Because

, the interference intensity of single electrons from the top and bottom beam is given by

where

or

represents the location of the n-th upper-beam or m-th lower-beam electron’s dot signal on the screen. Upon collecting the intermittent dot signals from arriving single electrons without knowing their trajectories, in the continuum limit of a large N, i.e., when the electron’s wavelength is much shorter than that of the fundamental cavity mode, Eq. (6B) can be reduced to the well-known formula [

23] as

This interpretation provides a more physical picture of how single electrons, neutrons, atoms, or molecules can result in an interference pattern yet induce a dot-like signal on a detector screen.Our mechanism offers a better physical explanation to the quantum interference of single particles. With quantized momentum transfer, one can obtain a better picture of how an electron can be deflected from its initial trajectory. According to our mechanism, a single electron can only pass one of the double slits at a time, there is no need for the counter-intuitive wave splitting, self-interference, and then wave recombination of the wave-packet of the same electron before detection. Furthermore, the Copenhagen interpretation of Schrodinger’s wave-equation approach does not need the unphysical wave function collapse hypothesis. According to our model, interference is caused by non-local interaction between the electron and the double-slit, and the interaction can be described as quantized momentum transfer from the double-slit cavity modes. The amplitude of the n2-th cavity mode is given by , which leads to an interference pattern with an intensity proportional to .

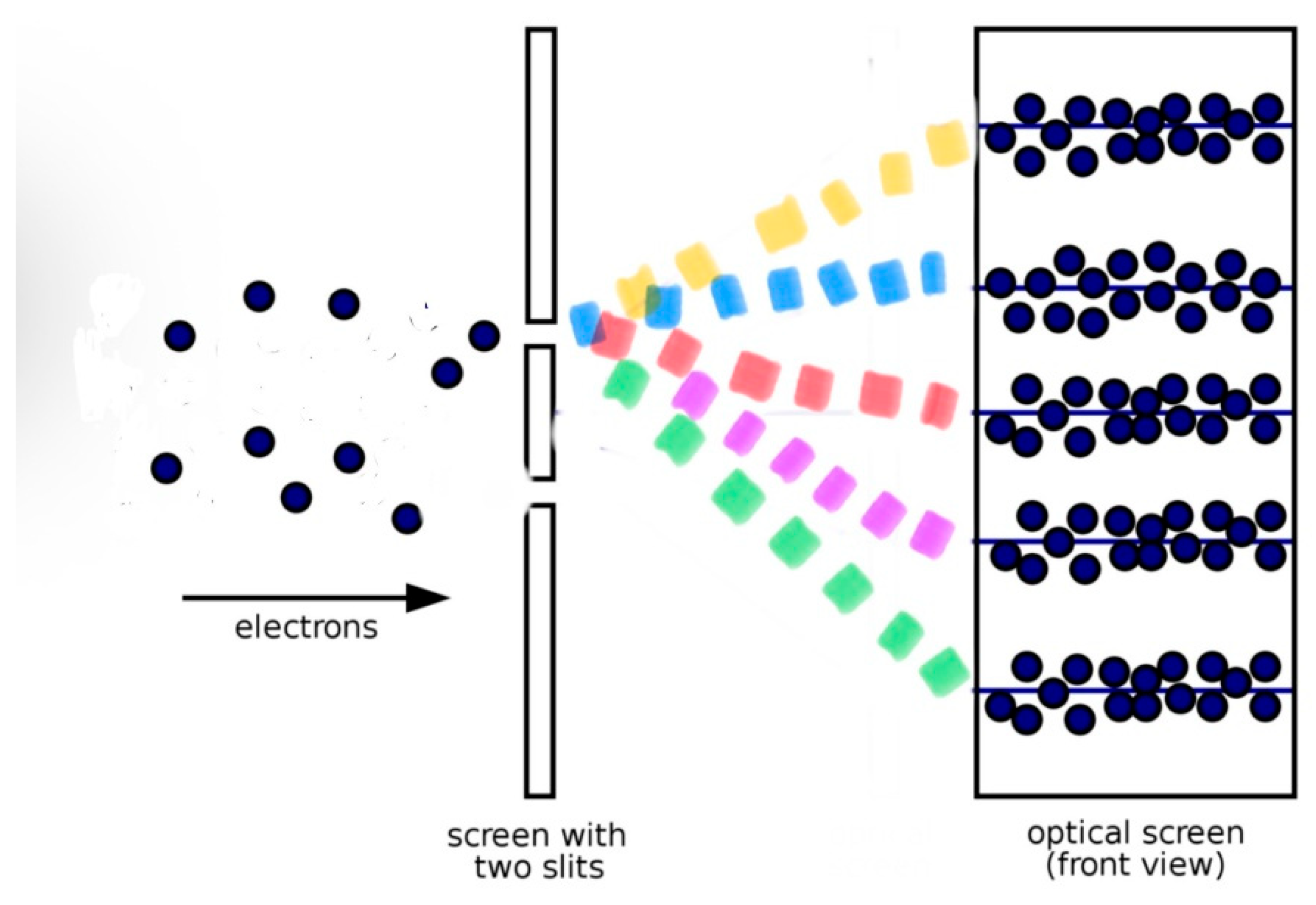

In

Figure 1, we use this schematic diagram for a couble0slit interference setup to elucidate our proposed mechanism, which indicates a single electron can only pass through one of the slits. Such a paradigm shift of quantum interpretation for the double-slit interference does not require the unphysical hypothesis of self-interference and wavefunction collapse during measurement.

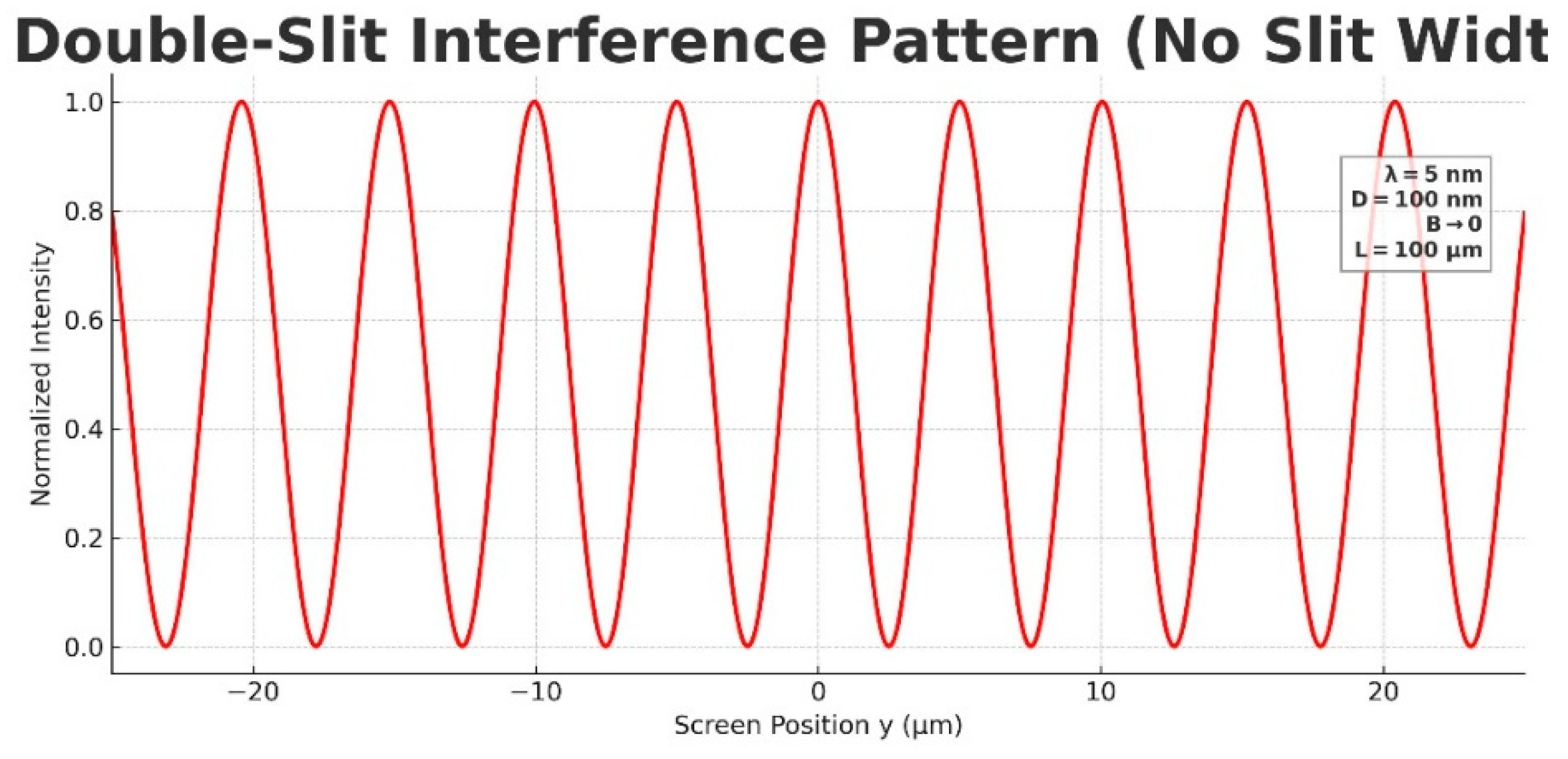

We use

Figure 2 to illustrate the resultant interference pattern for double-slit with a negligibly small slit width B, which is identical to the typical standard double-slit interference theory.

2.2. Heisenberg’s Operator Approach to Double-Slit Interference with a Finite Slit Width

Now, let’s consider a more realistic case where both slits have a finite width of B, then the potential becomes

where

, if

and vanishes elsewhere. The corresponding force components are given by

According to the above potential, with

and

defined in Eq, (4A), as a sum over the Fourier series components, it has

where

is the sinc-function defined as

Eq. (7) can be simplified and reduced to Eq (4) as B becomes 0. The overall interference intensity is given by

After accumulating the intermittent dot signals of single electrons without distinguishing their trajectories, in the continuum limit of a large N, i.e., when the wavelength of the fundamental cavity mode is much longer than that of the electron, the above equation can be simplified to the well-known formula [

23] as

Equations (10A–10B) serve as the key formulas for double-slit interference with a finite slit width B. Without invoking the wave theory’s counter-intuitive self-interference or the non-physical wavefunction collapse hypothesis, we re-derived the well-known interference formula which is a special case of our more general expression that predicts finer discrete fringes if the slit gap and the electron’s wavelength become comparable. Incoherence in the electron source or instabilities in the experimental setup—arising from mechanical or thermal fluctuations—can degrade the observed interference pattern.

Figure 3.

Double-slit interference pattern with finite slit width (B = 20 nm). An electron beam with wavelength λ = 5 nm is directed toward a double-slit barrier with slit separation D = 100 nm and slit width B = 20 nm. The resulting interference pattern is recorded on a detector screen located L = 100 μm away. The pattern exhibits modulation by a sinc2 envelope due to the finite slit width, superimposed on the cos2 interference fringes.

Figure 3.

Double-slit interference pattern with finite slit width (B = 20 nm). An electron beam with wavelength λ = 5 nm is directed toward a double-slit barrier with slit separation D = 100 nm and slit width B = 20 nm. The resulting interference pattern is recorded on a detector screen located L = 100 μm away. The pattern exhibits modulation by a sinc2 envelope due to the finite slit width, superimposed on the cos2 interference fringes.

2.3. The Second-Quantization Creation and Annihilation Operator Interpretation of Cavity Modes

In addition to the classical cavity field picture employed above, we now briefly reinterpret the discrete momentum transfer process using the formalism of second quantization. The double-slit cavity structure can be modeled as a set of localized quantized field modes, with the field potential expressed in operator form as

where

,

are the annihilation and creation operators for the nth cavity mode, f

and f

are normalized spatial profiles of mode n in the upper and lower slits respectively, and D is the slit separation. When an electron traverses one slit, it interacts with a single quantized field mode via minimal coupling. The momentum it acquires in the y-direction is proportional to the field amplitude of the selected mode

with

. The probability of such a mode interaction depends on the mode’s overlap with the slit structure, and the relative phase between contributions from the two slits. This leads directly to the interference term

. This term now acquires a natural interpretation: it quantifies the relative phase coherence between two cavity modes of equal index n, centered at each slit and separated by D. It corresponds to the projected Fock state overlap for detecting that cavity mode at the screen. If D/λ

c is such that the cosine term vanishes, then destructive interference prevents the excitation of that mode at the detector.

This second-quantized view provides an operator-level underpinning of the field structure responsible for interference, entirely consistent with the real-space Heisenberg dynamics derived earlier. Importantly, it offers a natural path for generalization to entangled cavities and multi-mode interactions. Such an interaction between a single electron with the cavity mode is causal and non-local because the wave nature of the cavity mode represents the electromagnetic force that is relativistic and causal. Although we use single electrons as an example, double-slit interference has been observed for other single particles, such as photons, atoms, and molecules. The interaction of single particles with a double-slit device is essentially an electromagnetic interaction between the particles and the dielectric slit device. Therefore, the basic underlying physics principle is the same.

We now extend the second-quantized operator formulation to include the effect of finite slit width B. Each slit cavity supports a set of standing wave modes that are confined to the physical width of the slit, and these modes can be described using windowed spatial functions. For slit width B, the mode functions take the form if or vanishes elsewhere.

This extension provides a richer basis for describing diffraction envelopes and modal interactions. The finite width introduces a sinc-like diffraction factor in the resulting momentum distribution

This formula captures the convolution of discrete cavity mode excitation with a continuous angular spectrum. The sinc envelope arises from the finite spatial confinement of the field, while the cosine term reflects coherent phase contributions between the upper and lower slits. This combined operator-based view aligns well with both the physical geometry and experimental interference profiles observed in electron and photon double-slit setups with structured slit boundaries.

3. Discussion

We propose a novel quantum framework based on quantized momentum transfer to analyze single-particle double-slit interference. This approach provides a physically grounded and intuitive explanation wherein an indivisible quantum particle traverses one slit and acquires discrete momentum via interaction with a quantized cavity field, ultimately producing a localized detection signal on a screen.

Unlike the standard Schrödinger wavefunction formalism and Copenhagen interpretation—which rely on wavefunction self-interference and probabilistic collapse, our model eliminates reliance on these non-deterministic assumptions. Instead, it attributes interference patterns to non-local, discrete momentum exchanges with structured cavity modes, offering a deterministic and experimentally testable alternative.

Importantly, this model remains consistent with observed violations of Bell’s inequality, reinforcing the inherently non-local nature of quantum phenomena without invoking hidden variables. Rather than relying on classical notions of local realism, non-locality emerges naturally in our framework from the quantized structure of the slit geometry and the stochastic excitation of cavity modes.

While the electron is used here as a primary example, our formulation generalizes readily to other quantum particles, including photons. The cavity-mode interaction mechanism unifies particle-like and wave-like behaviors in a physically meaningful manner, transcending the abstraction of wavefunction superposition. This resolves long-standing conceptual challenges and paradoxes—such as the necessity of wavefunction collapse or many-worlds branching—by offering a tangible, mechanistic picture of quantum interference.

Our theoretical predictions suggest measurable deviations from the standard interference fringe pattern when the particle wavelength approaches the scale of the slit separation. This opens a pathway for experimental validation, particularly in systems with high coherence and structural stability. Future experiments could help distinguish our framework from more abstract interpretations and offer new insights into the quantum-classical boundary.

By situating our analysis within both the Heisenberg operator framework and the second quantization formalism, we provide a comprehensive account of double-slit interference that is both physically realistic and mathematically rigorous. This approach aligns with Einstein’s vision of a complete quantum theory rooted in physical reality, potentially informing future foundational research in quantum mechanics.

4. Comparison with Existing Interpretations

Our proposed framework departs fundamentally from the major interpretations of quantum mechanics by attributing double-slit interference to quantized, non-local momentum transfer mediated by discrete cavity modes. This mechanism offers a deterministic, physically grounded alternative to conventional accounts, without invoking wavefunction collapse, self-interference, or ontologically ambiguous multiverses.

4.1. Copenhagen Interpretation

In the standard Copenhagen framework, the interference pattern arises from the superposition of the wavefunction traversing both slits simultaneously, followed by a non-unitary wavefunction collapse upon measurement. While this model reproduces experimental results, it relies on a probabilistic collapse mechanism that lacks a precise physical description and introduces a discontinuity in the evolution of quantum systems. By contrast, our model circumvents collapse entirely, maintaining unitary evolution and causal continuity. Interference arises not from the particle’s self-superposition but from quantized cavity-induced momentum kicks determined by the structured geometry of the slits.

4.2. Bohmian Mechanics

Bohmian mechanics provides a deterministic interpretation by introducing non-local hidden variables and guiding equations for particle trajectories. However, it retains the full wavefunction and relies on the quantum potential—a non-observable mathematical construct whose physical origin remains unclear. In contrast, our model attributes the observed behavior to physically quantized interactions with the slit cavity field, eliminating reliance on an ontologically real guiding wave. While both models are non-local and deterministic, our approach is conceptually simpler and directly tied to spatial quantization rather than an abstract configuration space.

4.3. Decoherence Theory

The decoherence approach explains the emergence of classical behavior through environmental entanglement, effectively suppressing interference between branches of the wavefunction. However, decoherence does not solve the measurement problem or explain why only one outcome is realized. Our framework does not depend on environmental decoherence but instead derives interference from discrete, stochastic interactions intrinsic to the slit geometry. The detection of localized outcomes results from quantized momentum exchange rather than partial trace operations over inaccessible degrees of freedom.

4.4. Delayed-Choice Interference

In Wheeler’s proposed delayed-choice interference experiments, one of the split beams is delayed and then combined with the other beam before detection [

24,

25], According to our mechanism, any changes of the double-slit configuration or additional detection scheme to probe the beams after passing the double-slit device would cause perturbations to each electron’s trajectory, and therefore, one need to include such impacts together with the quantized double-slit potential. The electron’s trajectory depends not only on the quantized potential of the double-slit configuration but also on any quantized interacting potential with other perturbing forces along its path.

5. Summary

Optical double-slit interference has been a hot debating issue since the era of Issac Newton and Thomas Young. The phenomena involving only single photons, electrons, or other larger particles are even more perplexing, leading to Feynman’s comment that no one understands quantum mechanics. Here, we formulate a deterministic, causal, non-local but causal model for double-slit quantum interference, based on Heisenberg’s operator and quantum field theory operator formalism.

Unlike Copenhagen (which assumes self-interference), Bohmian mechanics (which invokes guiding waves), or decoherence theory (which shifts the collapse into entanglement dynamics), our model directly ties interference to discrete, physically mediated, non-local momentum transfer within a quantized cavity structure. This offers both explanatory clarity and a pathway to experimentally testable deviations from conventional predictions. A crucial implication is its connection to Bell’s inequality, reinforcing quantum nonlocality while offering a new perspective without wavefunction collapse. Future experiments could further distinguish our approach, challenging many-worlds theory, which posits an unverified proliferation of universes. In contrast, our model grounds quantum behavior in discrete, testable momentum transfers, resolving paradoxes like Schrödinger’s cat as artifacts of misinterpreting wavefunction superposition. Crucially, this theory is not just interpretative, it is predictive, and it opens an experimental frontier in which new tests of various quantum interference and entanglement measurements can be done.

Formulated within Heisenberg’s operator framework, our model reproduces double-slit interference patterns without invoking self-interference or instantaneous collapse. This physically grounded approach aligns with Einstein’s vision of a comprehensible quantum reality while remaining experimentally testable.

Author Contributions

J. T. initiated the project, conceived the model, and derived the equations, J.T. and C. C. wrote the manuscripts.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported in part by the National Council of Science and Technology (Taiwan, NSTC 113-2221-E-002-193-MY3).

Disclosure

The authors have no conflict of interest with anyone or any organization.

References

- Feynman, R.P.; Leighton, R.B.; Sands, M. The Feynman Lectures on Physics; Addison-Wesley, 1965; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Merli, P.G.; Missiroli, G.F.; Pozzi, G. On the Statistical Aspect of Electron Interference Phenomena. American Journal of Physics 1976, 44, 306–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonomura, A.; Endo, J.; Matsuda, I.; Kawasaki; Ezawa, H. Demonstration of Single-Electron Buildup of an Interference Pattern. American Journal of Physics 1989, 57, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R.P. QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter; Princeton University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zeilinger, A. Dance of the Photons: From Einstein to Quantum Teleportation; Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bohr, N. Discussions with Einstein on Epistemological Problems in Atomic Physics, 1949.

- Everett, H. “Relative State” Formulation of Quantum Mechanics. Reviews of Modern Physics 1957, 29, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, D. A Suggested Interpretation of the Quantum Theory in Terms of “Hidden” Variables I & II. Physical Review 1952, 85, 166–193, (Bohmian Mechanics). [Google Scholar]

- Dirac, P.A.M. The Principles of Quantum Mechanics, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, J.A.; Zurek, W.H. Quantum Theory and Measurement; Princeton University Press, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, J.S. On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen Paradox. Physics Physique Физика 1964, 1, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspect, A.; Dalibard, J.; Roger, G. Experimental Test of Bell’s Inequalities Using Time-Varying Analyzers. Physical Review Letters 1982, 49, 1804–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weihs, G.; Jennewein, T.; Simon, C.; Weinfurter, H.; Zeilinger, A. Violation of Bell’s Inequality Under Strict Einstein Locality Conditions. Physical Review Letters 1998, 81, 5039–5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensen, B.; Bernien, H.; Dréau, A.E.; Reiserer, A.; Kalb, N.; Blok, M.S.; Taminiau, T.H. Loophole-Free Bell Inequality Violation Using Electron Spins Separated by 1.3 km. Nature 2015, 526, 682–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, J.S. Speakable and Unspeakable in Quantum Mechanics, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Aspect, A.; Grangier, P. Quantum Mechanics: From Basic Principles to Quantum Entanglement; Oxford University Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, A.; Podolsky, B.; Rosen, N. Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete? Physical Review 1935, 47, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, D. A Suggested Interpretation of the Quantum Theory in Terms of “Hidden” Variables. I & II. Physical Review 1952, 85, 166–179, 180–193. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, P.R. The Quantum Theory of Motion: An Account of the de Broglie–Bohm Causal Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics; Cambridge University Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Heisenberg, W. Quantum-Theoretical Re-Interpretation of Kinematic and Mechanical Relations. Zeitschrift für Physik 1925, 33, 879–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, J.J.; Napolitano, J.J. Modern Quantum Mechanics, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, D.J. Introduction to Quantum Mechanics, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Tannoudji, C.; Diu, B.; Laloë, F. Quantum Mechanics; Wiley, 1977; Volumes 1 and 2, ISBN 978-0471164333, 978-0471164357. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, J.A. The “Past” and the “Delayed-Choice” Double-Slit Experiment. In Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Theory; Marlow, A.R., Ed.; Academic Press, 1978; pp. 9–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jacques, V.; Wu, E.; Grosshans, F.; Treussart, F.; Grangier, P.; Aspect, A.; Roch, J.F. Experimental realization of Wheeler’s delayed-choice gedanken experiment. Science 2007, 315, 966–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).