1. Introduction

Thyroid cancer is the most common malignancy of the endocrine system and its incidence has been increasing steadily worldwide [

1,

2]. Papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) accounts for approximately 80–85% of cases. Known risk factors include radiation exposure, iodine deficiency or excess, hormonal influences, obesity, and oncogenic mutations such as

BRAF and

RAS [

3]. However, these factors do not fully explain the observed epidemiological trends.

Emerging evidence indicates that the human microbiota plays a role in carcinogenesis and endocrine regulation [

4,

5]. Dysbiosis has been linked to cancer initiation and progression through modulation of inflammation, immune escape, and hormonal metabolism [

6,

7]. Studies have already identified tissue-specific microbiota in breast, colorectal, and pancreatic cancers [

8]. In the thyroid, early studies suggest that

Cutibacterium acnes and other taxa may reside in both benign and malignant tissue [

3,

4]. Moreover, gut microbiota has been associated with autoimmune thyroid disease and thyroid function regulation [

7].

Despite these findings, rigorous characterization of thyroid tumor microbiota using paired non-tumor controls and simultaneous stool sampling is lacking. Population-specific studies are essential, given that diet, geography, and host genetics shape microbial ecology. Our group has previously demonstrated distinct microbial signatures in breast tumor versus normal tissues in Turkish women [

8]. Building on that framework, we hypothesized that PTC tumors would harbor unique microbial signatures distinct from paired non-tumor thyroid tissue and only partially overlapping with gut microbiota.

The aim of this pilot study was to compare the microbiota profiles of tumor tissue, adjacent normal thyroid tissue, and stool samples in Turkish patients diagnosed with papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC). To minimize interindividual variability and better characterize tissue-specific microbial signatures, paired samples from the same individuals were analyzed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

This single-center prospective pilot study enrolled consecutive adults (18–65 years) with histologically confirmed papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) scheduled for thyroidectomy at Kocaeli University Hospital. Key exclusion criteria were recent (≤3 months) systemic antibiotic or corticosteroid use, other active malignancy, autoimmune disease with immunosuppression, pregnancy or lactation, prior gastrointestinal surgery expected to alter gut microbiota, and BMI <18 or >32 kg/m² per protocol. A priori power estimation (G*Power) for paired nonparametric testing in a pilot framework supported inclusion of 15 participants.

The study was approved by the Kocaeli University Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee (protocol code: 2022/10.11; approval date: 10 September 2022) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.2. Sample Collection and Processing

Preoperative stool was collected one day before surgery using sterile kits (Qiagen, Hildeni Germany) with cold-chain transport and stored at −80 °C. During surgery, tumor and adjacent non-tumor thyroid tissue (~1 cm³ each, ≥1 cm from the tumor margin) were aseptically sampled by the attending pathologist using sterile, segregated instruments to minimize cross-contamination; samples were snap-frozen and stored at −80 °C. Negative controls (blank extraction and PCR no-template controls) accompanied every batch to monitor potential contamination. Only samples passing quality control thresholds (minimum sequencing depth of 20,000 reads after filtering) were retained for downstream analysis.

2.3. DNA Extraction and 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

DNA was extracted from tissues using either the PureLink™ Microbiome DNA Purification Kit or the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen Hilden, Germany) and from feces using the PureLink™ Microbiome Kit (Invitrogen Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). DNA quantity and purity were assessed by NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) and Qubit Fluorometer; fragment integrity was evaluated by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Hypervariable 16S rRNA regions were amplified with the Ion 16S™ Metagenomics Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) targeting V2, V3, V4, V6–7, V8, and V9. Libraries were prepared with the Ion Plus Fragment Library Kit and barcoded using Ion Xpress™ Adapters. Sequencing was performed on Ion PGM™/Ion S5™ platforms. Samples with <20,000 post-filter reads were excluded from downstream analyses.

2.4. Bioinformatics and Diversity Analyses

Raw reads were processed using Ion Torrent Suite and analyzed in QIIME2 (v2021.8). Denoising was performed with

DADA2 to obtain

amplicon sequence variants (ASVs). Taxonomic assignment used a naïve Bayes classifier trained on

SILVA v138 (99% similarity). Data were

rarefied to 20,000 reads per sample before diversity analyses. For compositional comparisons, abundances were converted to

relative abundance (%); all figures (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) use

0–100% Y-axes with units clearly labeled.

Raw counts were not used for between-group visualization or inference.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics v20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Normality was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. Normally distributed data are presented as mean ± standard deviation; non-normally distributed variables as median (interquartile range); categorical variables as frequency (%). Differences between groups were tested using independent sample t-test or Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. For paired comparisons, paired t-test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied. Relationships between categorical variables were examined using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test.

For microbial diversity analyses, PERMANOVA was used to test beta diversity differences. To strengthen interpretation, effect sizes (Cohen’s d or r) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated where appropriate. To control for multiple comparisons, p-values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) method, unless otherwise specified. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For paired tumor–normal comparisons, we used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and report effect sizes (r) alongside Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR)–adjusted p values. Box plots display median and interquartile range (IQR) with whiskers at 1.5 × IQR.

3. Results

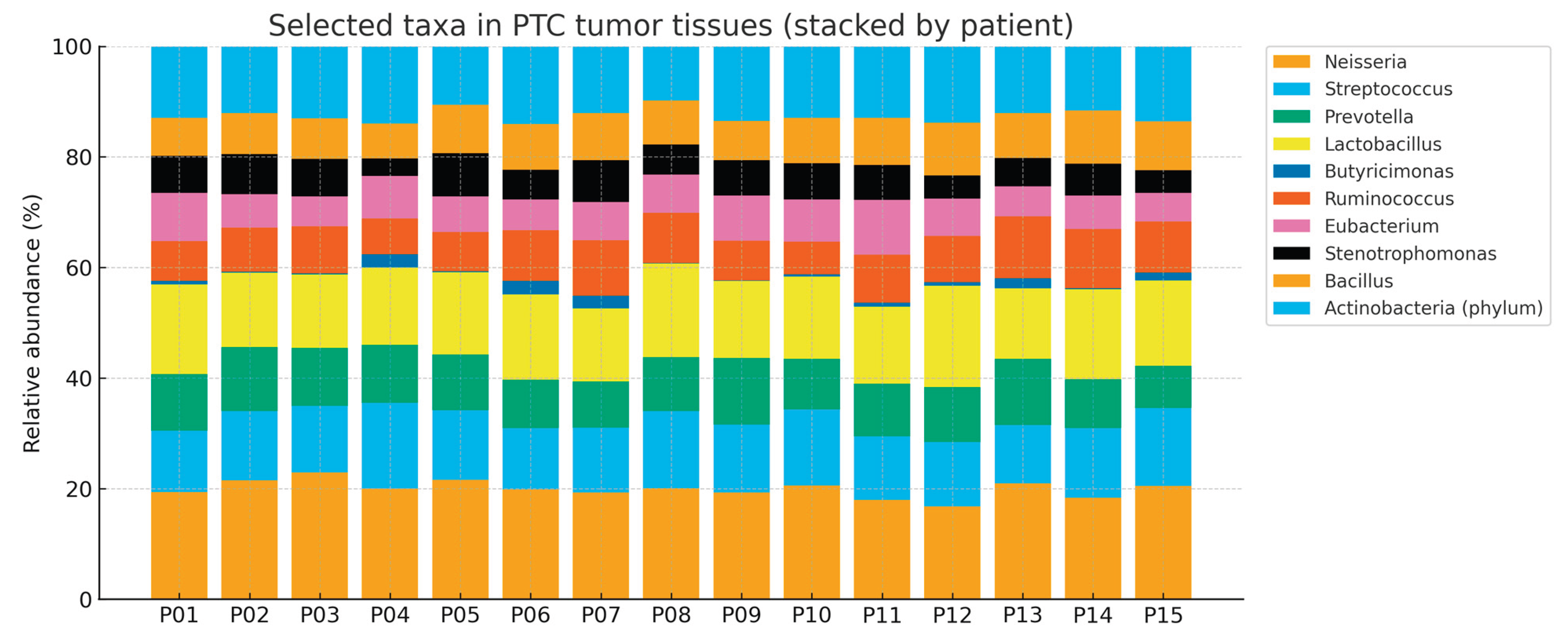

3.1. Cohort Characteristics

Fifteen PTC patients were included (female 86.7% [13/15]; male 13.3% [2/15]); mean age 43.0 ± 10.5 years. Thyroid function tests were within reference ranges at diagnosis. Multiple tumors were present in 40% (6/15). Median tumor diameter was 10 mm (IQR 6–15). Median number of involved lymph nodes was 1 (IQR 0–24). (

Table 1 ) Histology comprised classic PTC (66.7%), oncocytic variant (13.3%), and infiltrative variant (20%). Detailed encapsulation and invasion status are summarized in

Table 2.

3.2. Community-Level Differences

Alpha diversity differences between tumor and non-tumor thyroid tissues were modest and not consistently significant. Stool samples displayed higher richness and diversity, as expected. PERMANOVA confirmed significant separation between thyroid and stool, while tumor vs. non-tumor tissues clustered more closely but remained statistically distinguishable.

3.3. Family Level

Streptococcaceae and

Clostridiaceae were significantly enriched in tumors after FDR correction (see q values column).

Acetobacteraceae and

Bifidobacteriaceae showed nominal enrichment. Full results are summarized below. (

Table 3)

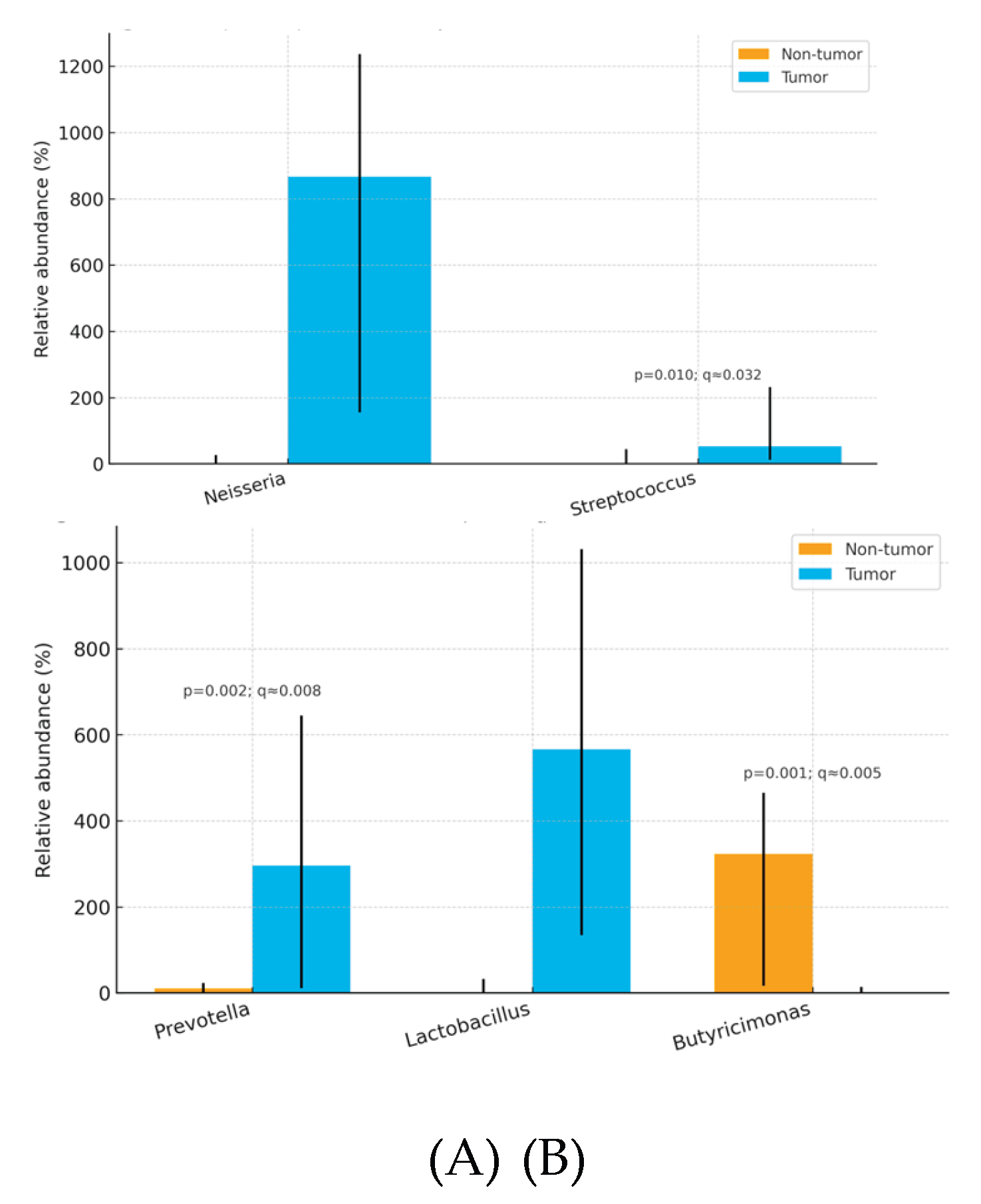

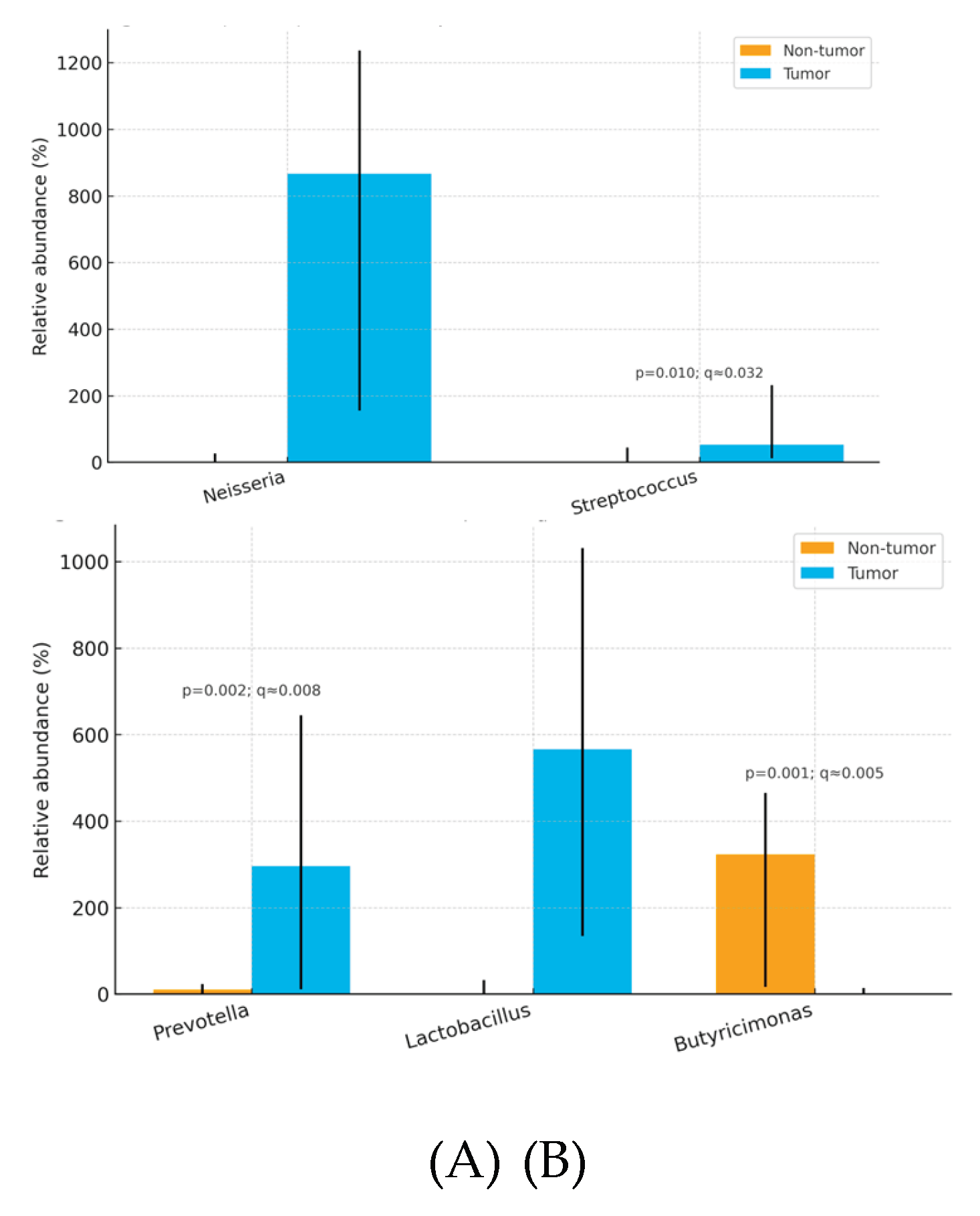

3.4. Genus Level

Tumors were enriched in

Neisseria, Streptococcus, Prevotella, Lactobacillus, and depleted in

Butyricimonas relative to non-tumor tissue. (

Table 4)

3.5. Species Level

Only

Cutibacterium (Propionibacterium) acnes showed nominal enrichment in tumor tissue. (

Table 5)

3.6. Summary of Findings

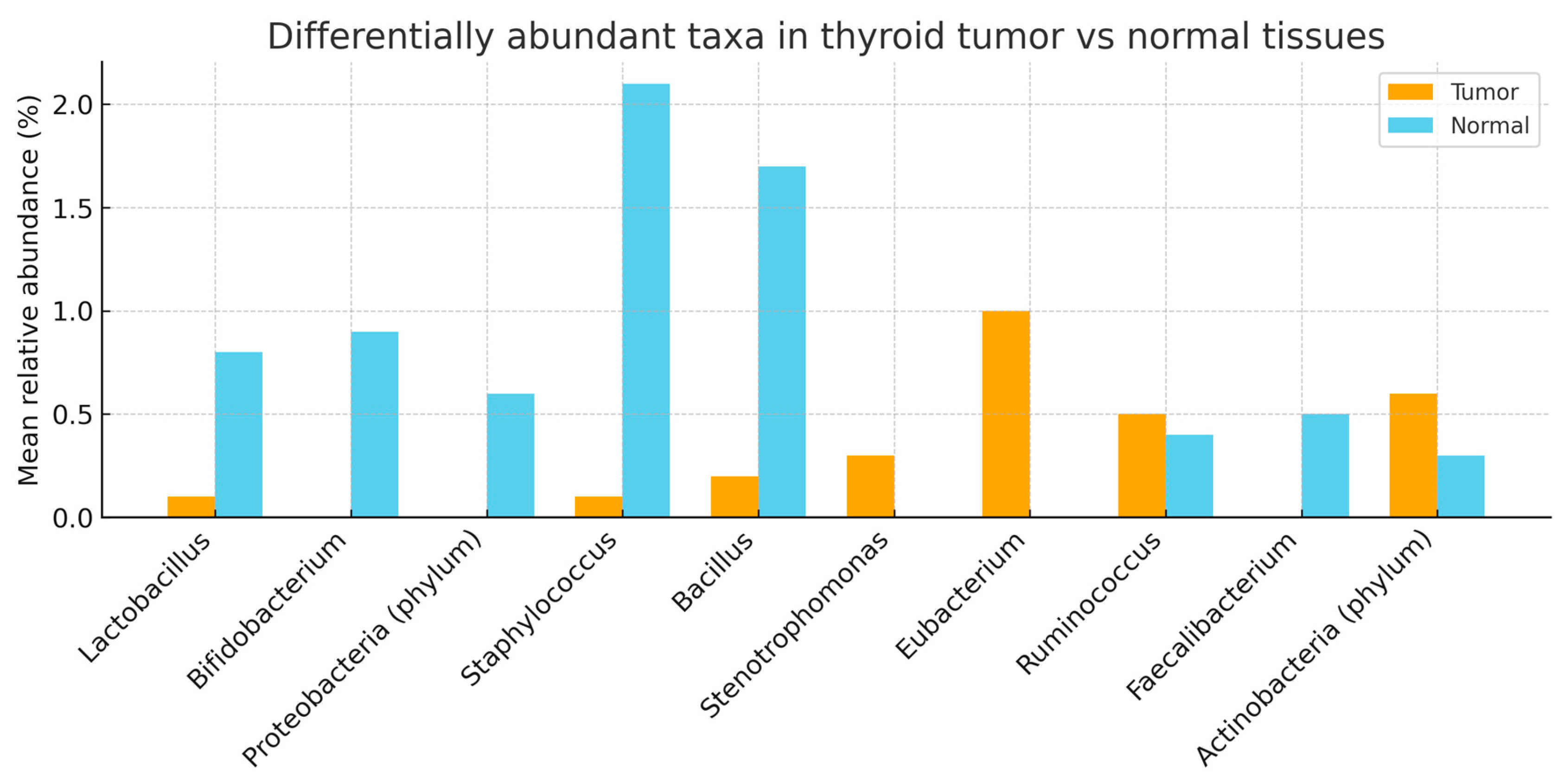

Overall, thyroid tumor tissue exhibited dysbiosis relative to paired non-tumor tissue, marked by enrichment of pro-inflammatory or opportunistic taxa at both family and genus levels—Streptococcaceae and Clostridiaceae at the family level, and Neisseria, Streptococcus, Prevotella, and Lactobacillus at the genus level—together with depletion of the potentially protective, SCFA-linked genus Butyricimonas. At the species level, Cutibacterium (Propionibacterium) acnes showed a nominal increase in tumor tissue but did not remain significant after FDR correction. These tissue-localized microbial shifts were not mirrored in fecal microbiota profiles, supporting the interpretation that dysbiosis in papillary thyroid carcinoma is primarily thyroid-specific rather than systemic. Patterns were broadly consistent across patients, although the modest cohort size limited power for subgroup analyses.

4. Discussion

Our prospective matched tri-sample study revealed distinct intratumoral microbiota in PTC compared with adjacent non-tumor tissue, while fecal microbiota showed limited correlation. These results strengthen the concept of a localized thyroid dysbiosis.

4.1. Comparison with Previous Literature

Our analysis showed consistent tumor-side enrichment of

Streptococcaceae, Clostridiaceae, Neisseria, Streptococcus, Prevotella, and

Lactobacillus, with

Butyricimonas comparatively depleted in adjacent non-tumor tissue. This pattern mirrors broader observations of tumor-associated microbial shifts in endocrine malignancies, in which dysbiosis favors pro-inflammatory or opportunistic taxa while commensal, metabolite-producing genera recede [

3] Mechanistically, the over-representation of streptococcal and neisserial lineages in tumors is compatible with chronic low-grade inflammation and redox stress, biological contexts known to promote DNA damage, immune evasion, and protumor signaling cascades [

4].Conversely, the relative loss of

Butyricimonas may indicate diminished short-chain fatty-acid tone at the lesion site, a change plausibly coupled to reduced epithelial barrier support and dampened anti-inflammatory signaling.

Of note, our species-level exploration detected a borderline increase of

Cutibacterium (Propionibacterium) acnes in tumor tissue. While this signal did not meet FDR significance, it is directionally aligned with prior suggestions that

C. acnes may shape intratumoral immune microenvironments., by tilting T-cell programs toward regulatory/immune-suppressive states thereby potentially facilitating tumor persistence [

4]. Taken together, these findings reinforce a model in which thyroid tumors host a microbiota that is not simply a passive passenger but a community whose composition is compatible with inflammatory and immunomodulatory niches. Finally, when viewed alongside our earlier breast cohort from Turkey, a recurring motif emerges: enrichment of putatively pro-inflammatory taxa within tumor tissue and attenuation of immunoregulatory commensals in adjacent normal tissue, suggesting shared ecological pressures across endocrine-related cancers despite organ-specific contexts [

8].

4.2. Biological Implications

Tumor enrichment of

Streptococcus and

Neisseria may reflect chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and DNA damage pathways [

5,

6]. Depletion of butyrate-producing

Butyricimonas suggests diminished SCFA-mediated anti-inflammatory tone [

9].

C. acnes enrichment, though borderline, is consistent with its known ability to induce Treg polarization and immunosuppressive tumor microenvironments [

4]. These microbial imbalances could influence NF-κB and STAT3 signaling cascades, potentially contributing to PTC pathogenesis.

4.3. Clinical Translation

Distinct intratumoral signatures could serve as biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis, or therapeutic stratification. If validated, microbial profiles may complement established molecular markers such as BRAF V600E. Furthermore, modulation of the microbiota through probiotics, prebiotics, or antibiotics, although speculative, warrants exploration. Our study underlines the potential of microbiota-targeted strategies in endocrine oncology.

4.4. Fecal Microbiota Findings

In contrast to thyroid tissue samples, fecal microbiota profiles in this study showed limited variability among participants and no significant correlation with either tumor or adjacent non-tumor thyroid microbiota. This finding differs from some reports suggesting potential gut–thyroid communication through immune or endocrine mechanisms. Several factors may account for this discrepancy. First, the cohort size was relatively small, reducing statistical power. Second, dietary habits were self-reported and relatively homogeneous across participants, possibly limiting interindividual variation in gut microbiota. Third, the absence of stool samples from healthy controls restricted the interpretability of fecal findings. Collectively, these observations suggest that although gut microbiota may influence systemic endocrine and immune regulation, the dysbiosis observed in papillary thyroid carcinoma appears to be predominantly localized to thyroid tissue rather than a reflection of systemic microbiome alterations.

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. The sample size was modest (n = 15), limiting generalizability and statistical power to detect subtle associations. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences regarding whether microbial alterations are drivers or consequences of tyhroid cancer. The lack of healthy thyroid tissue or stool controls restricts our ability to establish baseline comparisons. Dietary data were self-reported using non-validated questionnaires, which may have introduced bias. Methodologically, the use of 16S rRNA sequencing limited taxonomic resolution to the genus level and did not provide functional insights into microbial activity. Future studies employing shotgun metagenomics, metabolomics, or transcriptomics are required to clarify functional roles.

4.6. Future Directions

Future research should address these limitations and expand upon the current findings:

Larger, multi-center studies: To validate microbial signatures across diverse ethnic and geographic populations.

Longitudinal designs: To determine whether microbial shifts precede papillary thyroid carcinoma development or arise as a consequence of malignancy.

Functional analyses: Incorporating metagenomic, metabolomic, and transcriptomic approaches will be essential to identify metabolic pathways influenced by the thyroid microbiota.

Inclusion of healthy controls: Both thyroid tissue and stool samples from cancer-free individuals are necessary to establish reference baselines.

Dietary assessment: Standardized and validated dietary tools should be employed to minimize bias in gut–thyroid microbiota comparisons.

Therapeutic exploration: While speculative, interventions aimed at modulating the thyroid microbiome—such as probiotics, prebiotics, antibiotics, or dietary modifications—should be evaluated for potential preventive or adjunctive roles in thyroid cancer management.

5. Conclusions

This pilot study compared the microbial profiles of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) tissue, adjacent non-tumor thyroid tissue, and stool. We observed significant differences between tumor and paired non-tumor tissues, with enrichment of potentially pro-inflammatory or tumor-associated taxa in tumors notably Neisseria, Streptococcus, Prevotella, Lactobacillus, and the families Streptococcaceae and Clostridiaceae and relative depletion of potentially protective commensals such as Butyricimonas in non-tumor tissue. In contrast, fecal microbiota profiles were comparatively homogeneous across participants and showed no robust correlation with intrathyroidal composition, suggesting that dysbiosis in PTC is localized to thyroid tissue rather than reflective of a systemic gut signature.

Although limited by small sample size, lack of healthy thyroid/stool controls, and reliance on 16S rRNA sequencing, our study provides evidence that microbial alterations within thyroid tissue may be linked to PTC biology. These findings support the need for larger, multi-omics investigations to clarify functional roles of the thyroid microbiome and to evaluate its potential as a biomarker or therapeutic target in thyroid cancer.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, K.G., M.F.Ö. and T.Ş.; methodology, K.G. and M.F.Ö.; software, M.F.A.; validation, M.F.Ö., N.C. and D.S.A.; formal analysis, M.F.Ö. and M.F.A.; investigation, K.G., M.F.Ö. and N.C.; resources, T.Ş. and N.Z.C.; data curation, K.G. and M.F.A.; writing—original draft preparation, K.G. and M.F.Ö.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, M.F.A. and M.F.Ö.; supervision, T.Ş. and N.Z.C.; project administration, T.Ş. and N.Z.C.; funding acquisition, M.F.Ö. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Kocaeli University Faculty of Medicine (protocol code: 2022.10.09 approval date: 3 March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the technical staff of the Kocaeli University Medical Genetics and Medical Biology Departments for their assistance in sample processing and sequencing. Professional English editing was provided prior to submission.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.:

Abbreviations

| PTC |

Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma |

References

- Sung H.; Ferlay J.; Siegel R.L.; Laversanne M.; Soerjomataram I.; Jemal A.; Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin.2021;71:209–249. [CrossRef]

- Bray F.; Laversanne M.; Weiderpass E.; Soerjomataram I. The Ever-Increasing Importance of Cancer as a Leading Cause of Premature Death Worldwide. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229–263.

- Garrett W.S. Cancer and the Microbiota. Science. 2015;348:80–86. [CrossRef]

- Belkaid Y.; Hand T.W. Role of the Microbiota in Immunity and Inflammation. Cell. 2014;157:121–141. [CrossRef]

- Wang S.; Liu Y.; Li X.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Acts as a Pro-Carcinogenic Bacterium in Colorectal Cancer: From Association to Causality. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:710165. [CrossRef]

- Louis P.; Hold G.L.; Flint H.J. The Gut Microbiota, Bacterial Metabolites and Colorectal Cancer. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:661–672. [CrossRef]

- Virili C.; Centanni M. "With a Little Help from My Friends"—The Role of Microbiota in Thyroid Hormone Metabolism and Enterohepatic Recycling. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017;458:39–43. [CrossRef]

- Özsaray M.F.; Şimşek T.; Akkoyunlu D.S.; Çine N.; Cantürk N.Z. Distinct Breast Tissue Microbiota Profiles in Early-Stage Breast Cancer: A Prospective Study in Turkish Women. Life. 2025;15:1518. [CrossRef]

- Trivedi V.; Thomas M.; Chatzistamou I.; et al. Association of Cutibacterium acnes with Thyroid Cancer. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1152514. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note. The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).