Introduction

Breast cancer, alongside colon and lung cancer, are the most prevalent cancer types globally among women. It is estimated that approximately one in every 8 to 10 women will develop breast cancer during their lifetime, with incidence rates showing an upward trend worldwide.[

1] According to the latest data from the World Health Organization's Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN) in 2020, out of 19 million cancer diagnoses worldwide, over 2 million cases were attributed to breast cancer alone. In Turkey, a total of 24,175 women were diagnosed with breast cancer in the same year.[

2]

The progression of breast cancer varies significantly depending on a multitude of factors related to both the patient and the tumor itself. Factors such as age, genetic predisposition, hormonal influences, lifestyle choices, and environmental exposures all contribute to the diverse clinical presentations and treatment responses observed in breast cancer patients. Early diagnosis saves lives by increasing the effectiveness of treatment when the disease is caught at an earlier stage.[

3]

The treatment of breast cancer is multidisciplinary and surgical treatment is one of the main treatments. The main goal of surgery is to remove the tumor with clean borders and not to disrupt the aesthetics of the remaining breast tissue. Surgical techniques, such as breast-conserving surgery and oncoplastic surgery, are especially concerned with the aesthetics of the remaining breast tissue and are sympathetic to the aesthetic concerns of patients after surgery.[

3]

Microbiota, an emerging field of research, has been associated with specific biological processes in many diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, obesity, diabetes, brain disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and cancer. Microbiota, in its simplest terms, is the bacterial community living in various parts of the human body. These bacterial communities, which have different characteristics in each person, affect human metabolism through basic mechanisms, such as inflammation and hormone synthesis. Recent studies suggest that changes in the intestinal microbiota in particular may affect cancer development and progression through mechanisms such as immunity, bioavailability of nutrients, and effects on hormonal processes. [

4,

5]

The aim of this study was to evaluate breast cancer tissue, normal breast cancer tissue and stool microbiota in a cohort of Turkish women with early-stage breast cancer and to investigate possible connections between them. We hope that by elucidating these relationships, we will better understand the etiology of breast cancer and that this knowledge will contribute to the development of future diagnosis and treatment options.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Patient Selection: This prospective observational study was conducted between 2022 and 2023 at a single tertiary care center in Turkey. Female patients aged between 30–75 years who were diagnosed with stage I–II invasive breast cancer and scheduled for breast-conserving surgery were screened. Inclusion criteria were: histopathologically confirmed invasive carcinoma, no systemic antibiotic or corticosteroid use within the last three months, no history of autoimmune or chronic inflammatory diseases, no previous malignancy, and no pregnancy or lactation during the study period. Patients who did not consent or failed to provide stool samples were excluded.

Sample Collection and Storage: During surgery, tumor tissue and adjacent normal breast tissue (at least 2 cm away from the tumor border) were aseptically collected and immediately stored in RNase/DNase-free tubes at −80°C. Fresh stool samples were collected one day before surgery using sterile collection kits (Qiagen), and stored at −80°C until DNA extraction.

DNA Extraction and16S rRNA Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from tissue samples using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) and from fecal samples using the PureLink™ Microbiome DNA Purification Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The concentration and quality of DNA were measured using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) and Qubit Fluorometer.

16S rRNA amplicon libraries were prepared using the 16S Metagenomics Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), targeting variable regions V2, V3, V4, V6-7, V8, and V9. Sequencing was performed on an Ion S5™ XL platform, generating an average of 50,000–80,000 reads per sample.

16. S rRNA Sequence Data Analysis

Raw sequence data were processed using the Ion Torrent Suite Software (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The ThermoFisher Ion Reporter Software metagenomics 16S analysis workflowwith QIIME 2 (v2021.8) was utilized to perform diversity analyses, including alpha and beta diversity, and to generate operational taxonomic unit (OTU) abundances from the 16S rRNA reads and assign taxonomy at the genus level by clustering sequences with a 97% similarity threshold.

Bioinformatic Analysis

Raw reads were processed using Ion Torrent Suite Software and analyzed via QIIME2 (v2021.8) and the SILVA v138 database. Denoising was performed using DADA2. Taxonomic assignment was carried out using a naïve Bayes classifier trained on SILVA 16S rRNA database (99% similarity). Alpha (Shannon diversity) and beta (Bray-Curtis dissimilarity) diversity metrics were computed. OTU abundance tables were normalized using rarefaction and visualized with principal coordinates analysis (PCoA).

Data Collection: Data on patients’ age, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), history of additional diseases, allergy history, menopausal status, menstrual regularity, breastfeeding history, oral contraceptive use, previous surgeries, family history of breast cancer, recent antibiotic use, COVID-19 infection status and vaccination history, histological subtype and stage of breast cancer were recorded.

Statistical Analysis: Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS, version 20.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. Normally distributed numeric variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation, while non-normally distributed variables are presented as median (25th-75th percentile). Categorical variables are expressed as frequency (percentage). Differences between groups were determined using the independent sample Student’s t-test and Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. The Kruskal-Wallis test was applied when there were more than two groups. Paired group comparisons were performed using the paired t-test and Wilcoxon-Signed Rank test. Relationships between categorical variables were determined using Chi-square analysis and Fisher’s Exact test. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

This study enrolled 22 female patients with an average age of 58.30±12.73 years and a mean BMI of 28.85±3.13 kg/m2. Of these patients, only 7 (31.8%) had a BMI below 30, while 15 (68.2%) had a BMI above 30.

1. Association Between Clinical Variables and Microbiota Composition

To assess whether clinical parameters influenced microbial diversity, we performed correlation and subgroup analyses:

No significant differences in alpha diversity (Shannon index) were found between premenopausal and postmenopausal women (p=0.291).

BMI categories (<30 vs. ≥30) did not significantly affect microbial richness or beta diversity (Bray–Curtis dissimilarity, PERMANOVA p=0.384).

Recent history of antibiotic use, oral contraceptive use, menopausal status, or comorbidities showed no statistically significant association with microbial abundance at genus level (all p > 0.05).

2. Microbial Differences Between Tumor and Normal Breast Tissue

Microbiota analysis of tumor and adjacent normal breast tissues revealed statistically significant compositional differences.

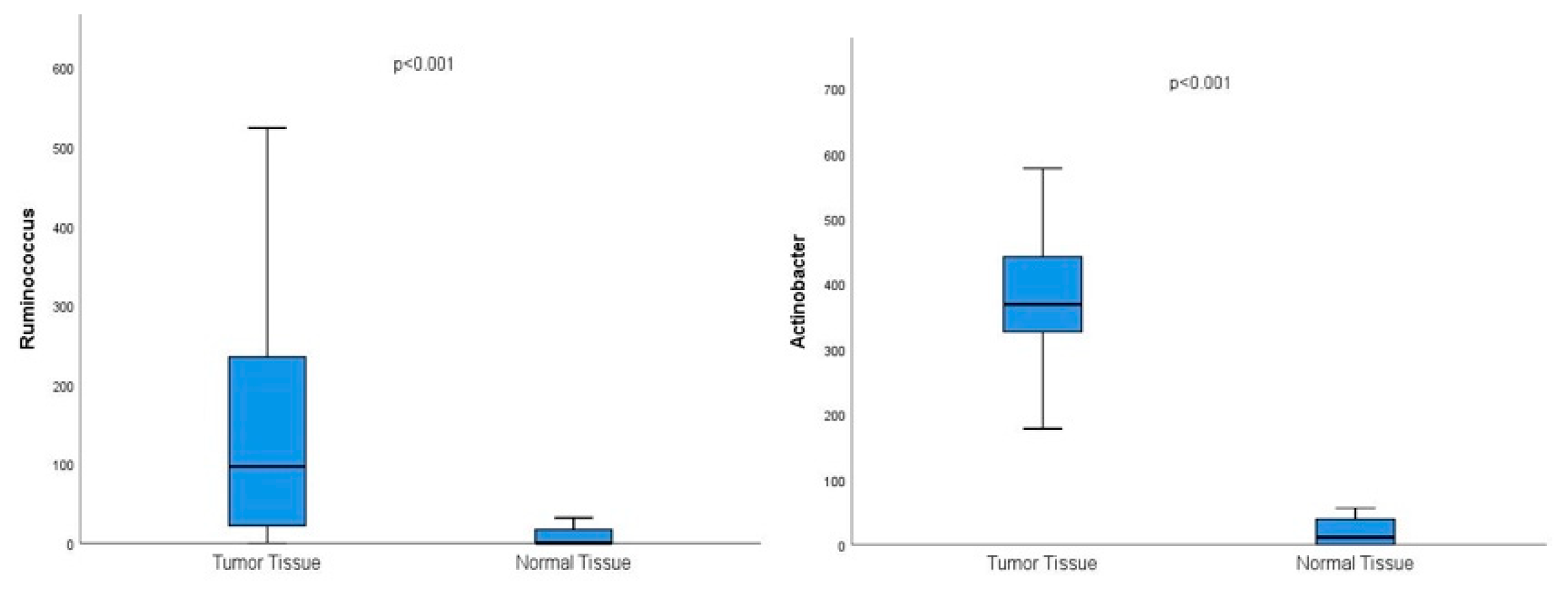

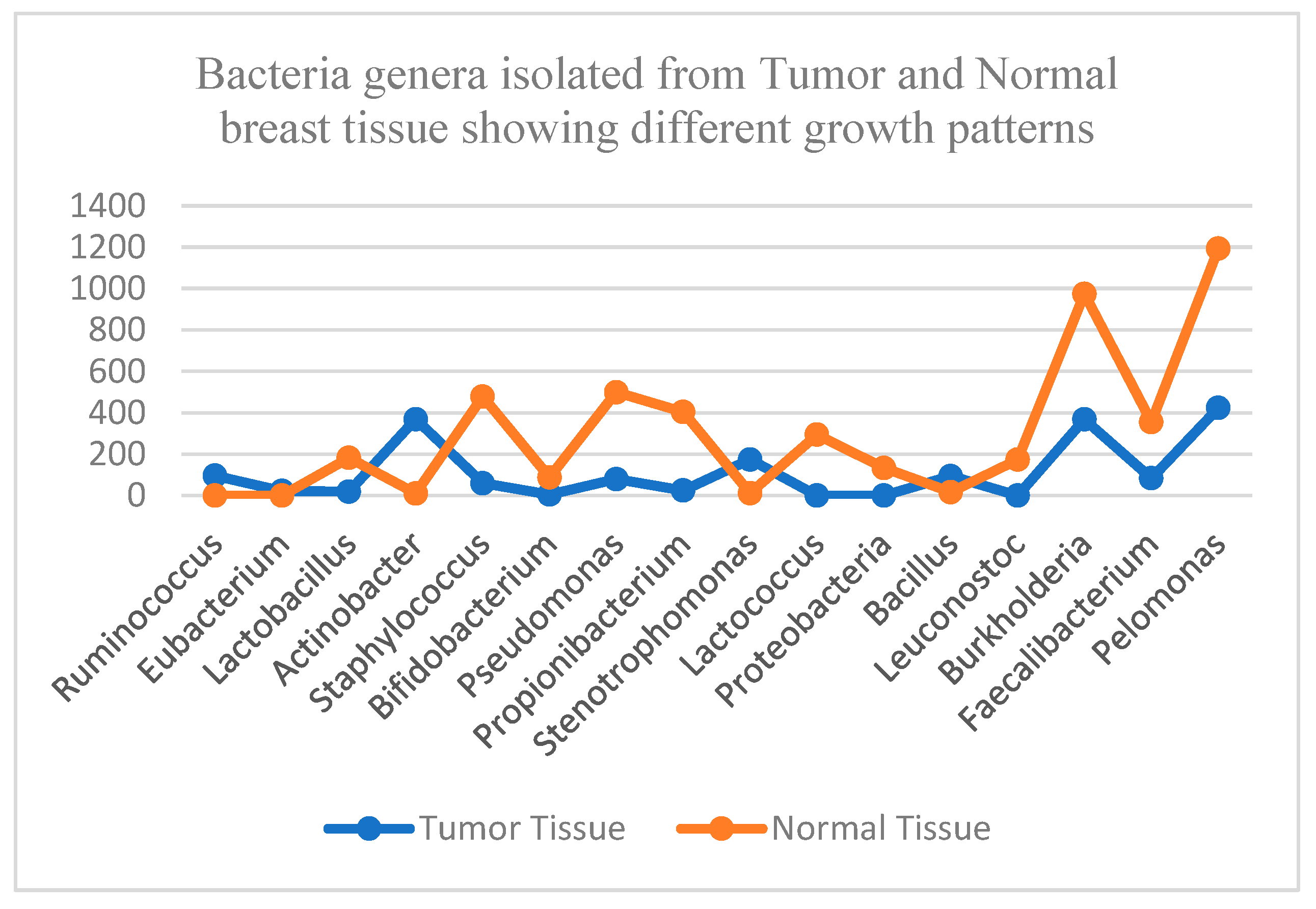

Microbiota analysis of tumor and normal breast tissue samples revealed significant variations in the growth patterns of several bacterial genera, families, and species. Notably, the tumor microenvironment exhibited distinct microbial profiles compared to adjacent normal tissue. Among the findings Ruminococcus, Eubacterium, Actinobacter, Stenotrophomonas, Bacillus, Lactobacillus, Staphylococcus, Bifidobacterium, Propionibacterium, and Lactococcus, exhibited significant differences in abundance and diversity between tumor and normal tissue samples. Organisms with higher prevalence in breast tumor tissue compared to normal tissue were Ruminococcus, Eubacterium, Actinobacter, Stenotrophomonas, and Bacillus genera.

Figure 1.

Graphs showing the significantly higher prevalence of the genus Ruminococcus and Actinobacter in tumor breast tissue compared to normal breast tissue in the whole cohort.

Figure 1.

Graphs showing the significantly higher prevalence of the genus Ruminococcus and Actinobacter in tumor breast tissue compared to normal breast tissue in the whole cohort.

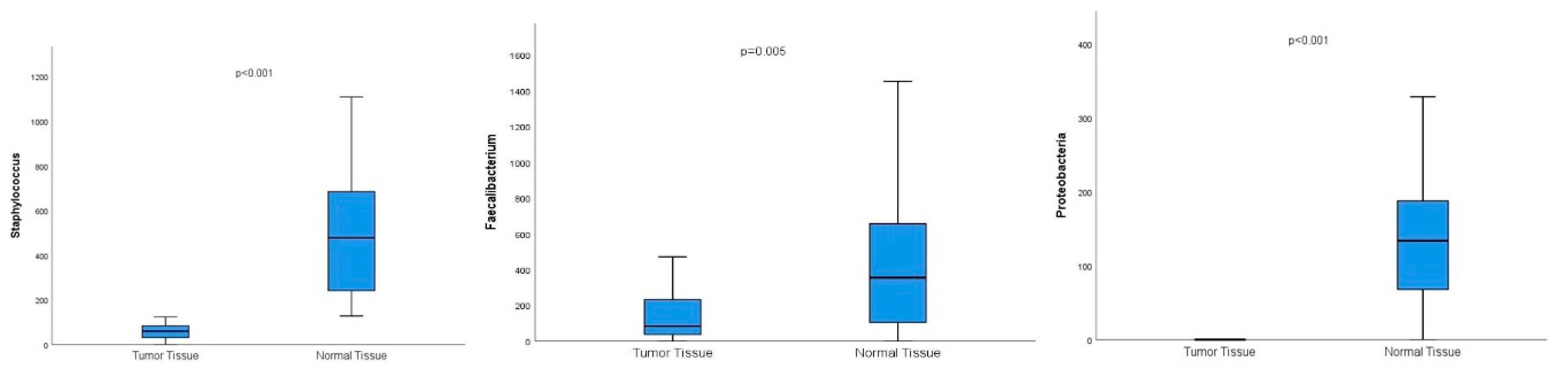

Conversely, Lactobacillus, Staphylococcus, Bifidobacterium, Propionibacterium, Lactococcus, Proteobacteria, Burkholderia, Faecalibacterium, and Pelomonas genera exhibited significantly higher prevalences in normal breast tissue compared to breast tumor tissue.

Figure 2.

Graphs showing the significantly higher prevalence of the genus Staphylococcus and Faecalibacterium and the species Proteobacteria in normal breast tissue compared to breast tumor tissue.

Figure 2.

Graphs showing the significantly higher prevalence of the genus Staphylococcus and Faecalibacterium and the species Proteobacteria in normal breast tissue compared to breast tumor tissue.

Figure 3.

This graph shows the distribution of bacterial genera with different growth patterns, specifically in tumor breast tissue and normal breast tissue.

Figure 3.

This graph shows the distribution of bacterial genera with different growth patterns, specifically in tumor breast tissue and normal breast tissue.

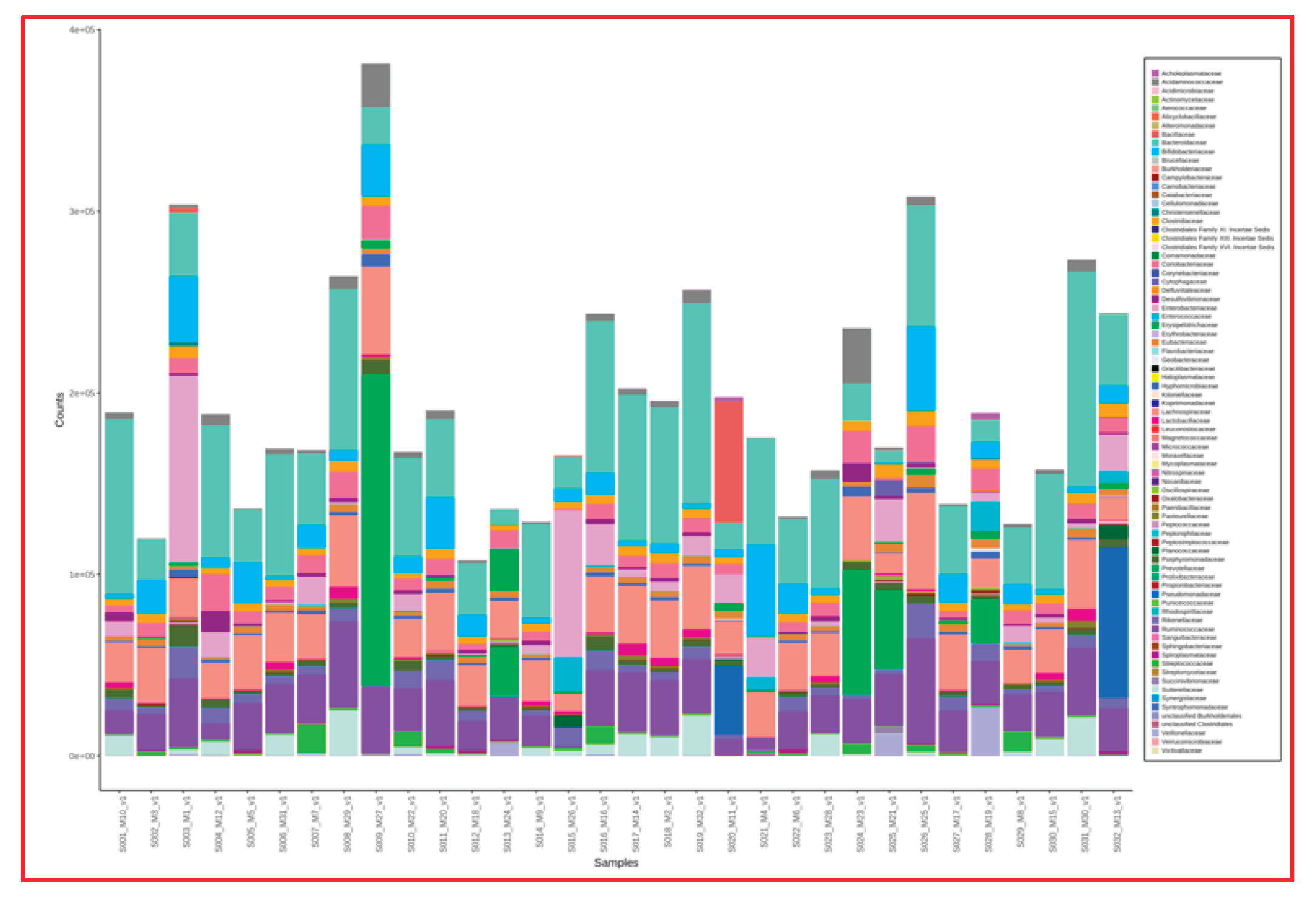

3. Fecal Microbiota Analysis

Fecal microbiota composition was assessed for each patient. However, no significant correlation was found between fecal microbial composition and either tumor or normal breast tissue microbiota (p > 0.05). Intra-cohort fecal microbiota profiles showed general similarity across patients, likely due to similar dietary habits reported by participants.

The results of the current study demonstrate dysbiosis in breast cancer tumor tissue compared to normal breast tissues from the same individual patients. These differences in individual microbiota in cancerous and normal breast tissue may reflect local changes in immune function. However, we suggest the potential role of this dysbiosis in the development of breast cancer should be investigated in depth, as it is possible that it may be directly influential in cancer development and progression. Investigating this imbalanced growth could provide data for developing personalized diagnostic and therapeutic methods tailored to the microbiota.

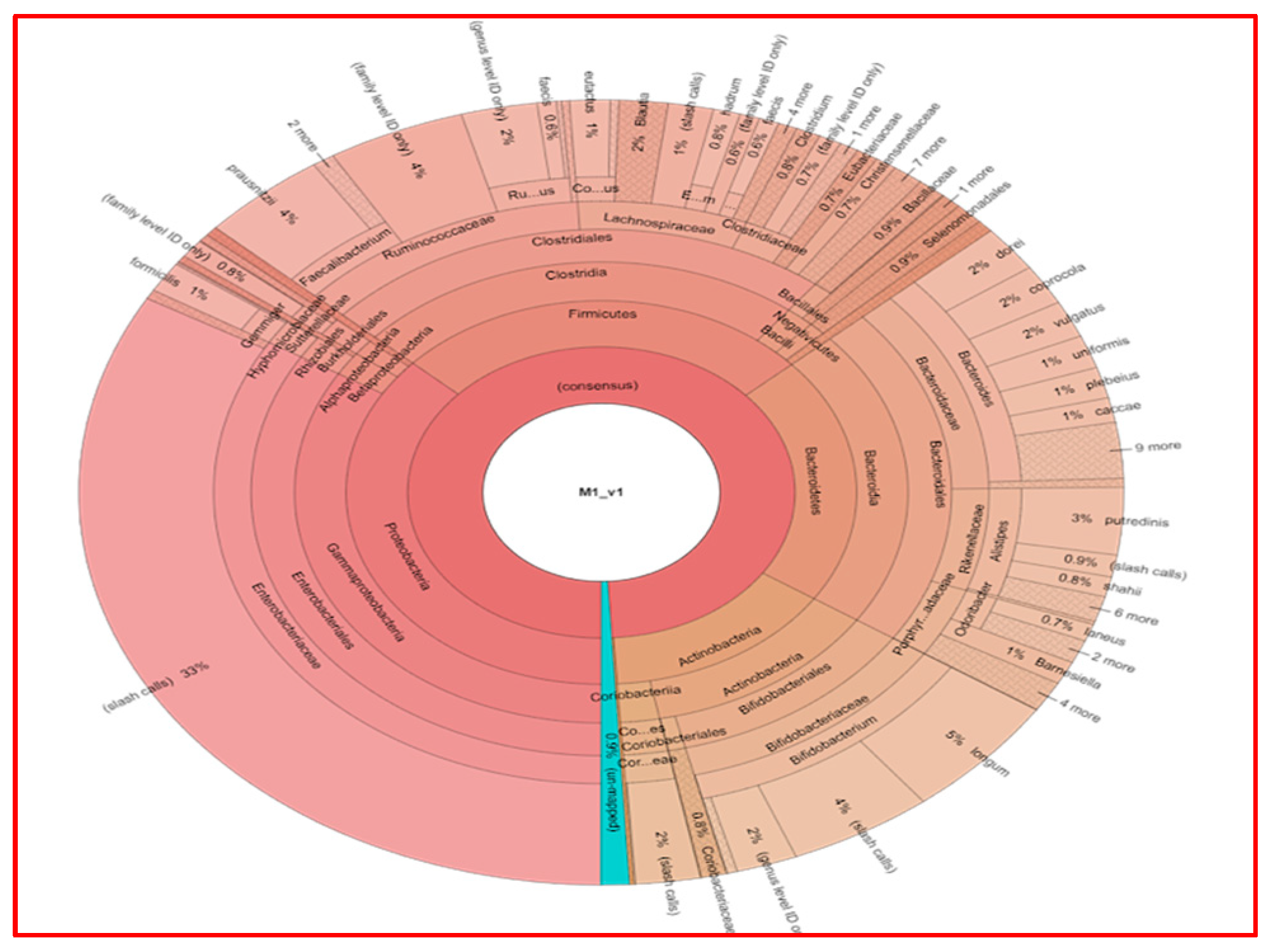

Figure 4 shows the results of fecal analysis in terms of bacterial genera for each individual patient.

Figure 5 shows the fecal analysis results of a single patient (Patient M1).

Upon examining the fecal microbiota analysis of the 22 patients included in our study, bacterial growth was generally found to be similar in number and type. Since our study does not include fecal samples from healthy individuals, the fecal microbiota of breast cancer patients was compared with the microbiota of both tumor and normal breast tissues, yielding no statistically significant results.

Discussion

This study provides further insights into the potential role of the microbiota in breast cancer by comparing bacterial profiles in tumor tissue, adjacent normal breast tissue, and stool samples from Turkish women with early-stage breast cancer. The significant microbial differences observed between tumor and normal tissue within the same individual highlight the possible involvement of local dysbiosis in breast cancer pathophysiology. Previous research has demonstrated the presence of distinct microbial communities in breast tissue, suggesting that the breast possesses its own microbiome independent of the gut [

1,

4,

8].

In line with these findings, our study revealed a higher abundance of Ruminococcus, Eubacterium, Actinobacter, Stenotrophomonas, and Bacillus in tumor tissues, whereas normal tissues were enriched with Lactobacillus, Staphylococcus, Bifidobacterium, and Faecalibacterium. These differences may indicate a shift in the breast microenvironment associated with tumorigenesis. We found that some bacteria proliferate more in breast cancer tissue, while others are more prevalent in normal breast tissue compared to cancerous tissue. Specifically, the high proliferation of Actinobacter and Stenotrophomonas species in breast cancer tissue, coupled with their almost negligible presence in normal tissue, may suggest their potential impact on tumor growth. Similarly, the high prevalence of Lactobacillus, Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas, and Lactococcus species in normal breast tissue but almost no growth in cancerous breast tissue suggests that the reduction of these species may be associated with the development of breast cancer in some fashion.

Differences in bacterial mRNA levels observed between cancerous and normal breast tissues suggest that the respective microbiota vary significantly. Pathogenic bacteria, such as Actinobacter and Stenotrophomonas, may play a role in the pro-inflammatory processes thought to contribute to cancer development. In contrast, bacteria known for their anti-inflammatory properties, such as Lactobacillus and Lactococcus, were found to be less abundant in cancerous tissues. This imbalance suggests that maintaining a healthy microbiota may be crucial for preventing the progression of breast cancer.

Particularly noteworthy is the high prevalence of

Actinobacter and

Stenotrophomonas in tumor tissue, which were nearly absent in normal samples. Previous studies have associated these taxa with chronic inflammation and immunomodulation, both of which are key processes in carcinogenesis [

5,

6,

9]. On the other hand,

Lactobacillus and

Lactococcus, which were significantly more abundant in normal tissue, have been recognized for their anti-inflammatory and potentially tumor-suppressive properties [

10,

11].

Breast cancer risk can be altered by local or gut microbiota through steroid hormone regulation, energy balance, metabolite synthesis (e.g., genotoxins, lipopolysaccharides, vitamins, antibiotics), and immune modulation [

6]

However, one of the limitations of the present study was the small sample size, which restricts the generalizability of our findings. Furthermore, the species identified in this population of Turkish women is unlikely to encompass the full range of microbiota variations in breast cancer patients. Unfortunately, the cross-sectional nature of the study also prevents us from establishing a causal relationship between microbiota composition and breast cancer. Thus large, multi-population studies are needed to confirm if these findings are consistently found in other populations. Longitudinal studies would be necessary to determine whether changes in microbiota precede the development of breast cancer or result from the disease. There are also some limitations to the methods used in microbiota analysis. Although mRNA analysis provides information about the degree of prevalence of bacteria in a sample, it cannot provide much information about the function of the organisims. Metagenomic and metabolomic techniques are the basic methods used to understand the microbiota. These methods allow the identification and quantification of microbial metabolites, thus providing quantitative data about which bacteria the microbiota consists of and some of the metabolic effects which may provide clues as to the effects of these bacteria on cancer development. [

7,

8]

Interestingly, we did not observe statistically significant associations between clinical variables—such as BMI, menopausal status, or oral contraceptive use—and microbiota composition. While previous literature has proposed a role for estrogen metabolism and obesity in shaping the gut and breast microbiome [

6], our findings suggest that microbial alterations in breast cancer tissue may be more locally driven rather than strongly associated with systemic factors. However, due to the limited sample size, these observations should be interpreted with caution.

Our fecal microbiota analysis revealed generally consistent profiles among patients, with no significant associations between stool and breast tissue microbiota. This contrasts with earlier studies suggesting potential communication between the gut and breast via immune or endocrine signaling [

4,

7]. The lack of a healthy control group further limited the interpretability of fecal findings in this study.

Clearly, the microbiota is affected by external factors, such as nutritional habits, antibiotic use and steroid use which are known to significantly affect the microbiota.[

9] Although we tried to control these factors in our study by excluding patients using antibiotics or systemic steroids, it should be accepted that some factors, particularly variations between individual patients diets, cannot be controlled.

No significant differences were detected when the fecal microbiota of the patients was compared with each other. When the dietary habits of the patients were included in our study, it was found that they had similar eating patterns. They reported occasionally consuming fast food and fried foods in their daily lives. However, the small number of patients in our study and the lack of fecal samples from non-cancer patients prevented us from making comparisons in this regard.

Several limitations warrant mention. First, the sample size was modest (n=22), limiting the statistical power to detect subtle associations. Second, the absence of healthy controls precluded comparison with baseline microbial profiles. Third, while we excluded patients with recent antibiotic or steroid use, diet—a known modulator of microbiota—could not be fully standardized. Patients in our cohort reported similar dietary habits, but these were self-reported and not validated.

Methodologically, we used 16S rRNA sequencing, which provides taxonomic resolution at the genus level but does not allow for functional profiling. Metagenomic or metabolomic analyses would be needed to elucidate microbial metabolic activity and its direct impact on the tumor microenvironment. Furthermore, longitudinal studies would be essential to determine whether microbial changes precede tumor formation or are a consequence of malignancy.

Despite these limitations, the results of this small-scale study suggest that the microbiota may have effects on the development of breast cancer and warrants further research. A better understanding of the microbiota may enable the discovery of new approaches for breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. Probiotics, prebiotics, and dietary changes are known to be effective methods for modulating and altering the microbiota. We speculate that if a microbiota profile conducive to breast cancer development can be clearly identified, then these methods may be used to alter the microbiota and reduce the risk of developing breast cancer. Changes to the microbiota may be effective in the prognosis, or perhaps even treatment, of breast cancer. [

10,

11]

Key Points to Emphasize:

Breast tissue has a distinct microbiome, differing between normal and cancerous areas.

Certain genera may play tumor-promoting or tumor-suppressive roles.

Microbial changes appear to be locally driven rather than linked to BMI or menopause.

Your study adds to growing evidence that local dysbiosis could be a biomarker or target in breast cancer.

Conclusion

This study compared the microbial profiles in samples of cancerous and normal breast tissue and stool samples obtained from patients who underwent breast-conserving surgery, in order to investigate the relationship between breast cancer and changes in microbiota. Our findings indicated that certain bacterial species were significantly more abundant in cancerous breast tissue compared to normal breast tissue, while others were more abundant in normal breast tissue compared to cancerous tissue. However, we did not find a significant relationship between patients' demographic characteristics or their clinical features and the microbiota profiles in our study. Furthermore, we did not identify significant microbiota-related relationships between stool samples and samples from breast cancerous tissue or normal breast tissue.

Thus there are qualitative differences between the profiles of organisms present in normal and malignant tissue but it is still unclear how the varying proliferation of these species, or their metabolites, impact or result in breast cancer. These relationships are likely extremely complex and indicate the need for further careful research. The better we understand the microbiota, which has been shown to affect many diseases, the better we can understand its effects and outcomes in breast cancer.

Although we did not observe significant associations between clinical or demographic factors and microbiota composition, our within-patient comparisons underscore that microbial alterations are likely localized phenomena rather than being broadly systemically influenced. Furthermore, stool microbiota profiles were generally homogeneous and did not significantly correlate with either tumor or normal breast tissue microbiota, highlighting the complexity of systemic versus local microbiome interactions.

Given the emerging evidence that microbial communities influence inflammation, immunity, and carcinogenesis, these findings open new avenues for investigating the role of the breast microbiome in cancer development and progression. However, our study is limited by its small sample size, lack of healthy controls, and use of 16S rRNA sequencing, which does not permit functional analysis.

Recommendations for Future Research

Larger, multi-center studies involving ethnically and geographically diverse populations are needed to validate our findings and establish generalizability.

Longitudinal studies could help determine whether microbiota alterations precede breast cancer development or are a consequence of tumor presence.

Functional metagenomics and metabolomics approaches should be employed to better understand the metabolic and immune interactions between microbiota and breast tissue.

The inclusion of healthy control groups and more detailed dietary assessments would improve the interpretability of stool microbiota data.

Future studies should also explore whether microbiota modulation—via probiotics, prebiotics, dietary interventions, or targeted microbial therapies—may offer preventive or therapeutic benefits in breast cancer.

Understanding the complex relationship between the microbiota and breast cancer may unlock new biomarkers and strategies for diagnosis, prognosis, and personalized treatment. Our findings contribute to the growing body of evidence that the local microbiome plays a meaningful role in breast cancer biology.

Declaration of İnterest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Committee Approval

The authors declare that the research was conducted according to the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki “Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects” (amended in October 2013). Local ethical committee approval was done at Kocaeli University IRB.

Funding Details

The authors declared that this study has received no financial support and no funding.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request.

References

- Harbeck, N.; Gnant, M. Breast cancer. Lancet 2017, 389, 1134–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Planning for tomorrow: global cancer incidence and the role of prevention 2020–2070. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2021, 18, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, M.F.; Reina-Pérez, I.; Astorga, J.M.; Rodríguez-Carrillo, A.; Plaza-Díaz, J.; Fontana, L. Breast Cancer and Its Relationship with the Microbiota. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018, 15, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eslami, S.Z.; Majidzadeh, A.K.; Halvaei, S.; Babapirali, F.; Esmaeili, R. Microbiome and Breast Cancer: New Role for an Ancient Population. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viswanathan, S.; Parida, S.; Lingipilli, B.T.; Krishnan, R.; Podipireddy, D.R.; Muniraj, N. Role of Gut Microbiota in Breast Cancer and Drug Resistance. Pathogens 2023, 12, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Tian, T.; Wei, Z.; Shih, N.; Feldman, M.D.; Peck, K.N.; Robertson, E.S. Distinct microbiological signatures associated with triple negative breast cancer. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 16893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hieken, T.J.; Chen, J.; Hoskin, T.L.; Walther-Antonio, M.; Johnson, S.; Ramaker, S.; Yao, J.Z. The microbiome of aseptically collected human breast tissue in benign and malignant disease. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 30751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbaniak, C.; Gloor, G.B.; Brackstone, M.; Scott, L.; Tangney, M.; Reid, G. The microbiota of breast tissue and its association with breast cancer. Appl Environ Microbiol 2016, 82, 5039–5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parida, S.; Sharma, D. The power of small changes: comprehensive analyses of microbial dysbiosis in breast cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2019, 1871, 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, S.; Chen, B.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhu, D.; Meng, Q.; Sun, Y. Study on the correlation between intestinal flora and breast cancer. Microb Pathog 2018, 114, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).