Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Line

2.2. Animals

2.3. Measurement of Tumor Size And Body Weight

2.4. ELF Exposure

2.6 Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining

2.7. Gram staining

2.8. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

...2.9Real-Time PCR

| Micro-organism | Primers | Sequence (5′-3′) | Annealing temp and time | Extension temp and time | Amplicon size (bp) | Detail |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E.coli |  |

56°C for 20 s | 72°C for 30 s | 40 | Self-designed |

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

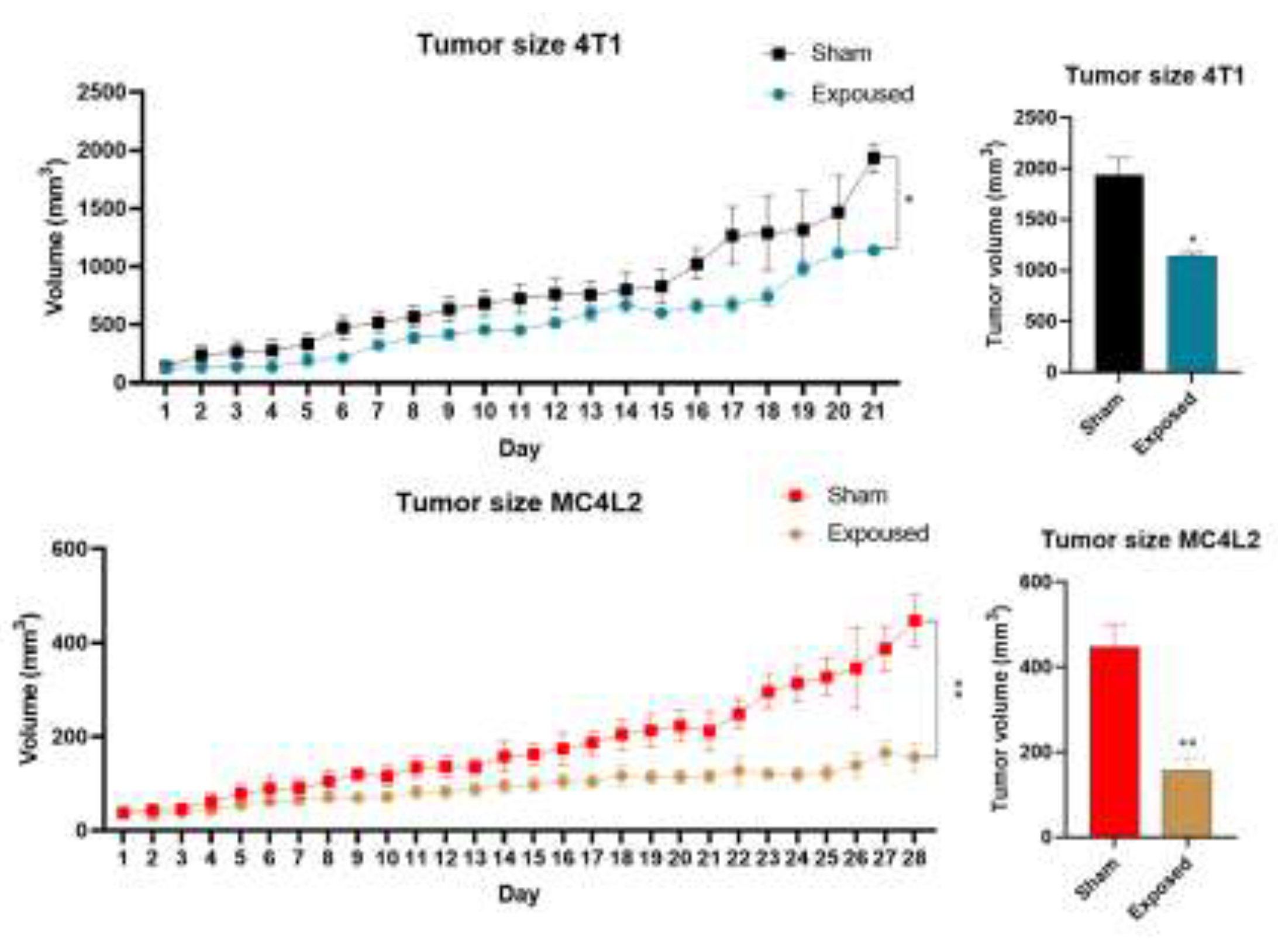

3.1. Tumor Size

3.2. H&E Staining Results on Vital Organs

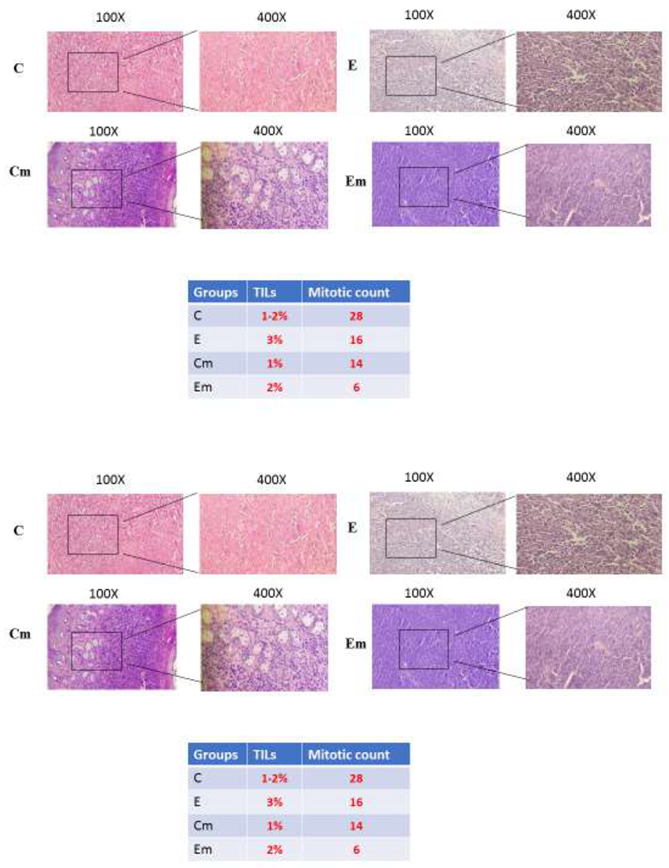

- The H&E results: The control group of TNBC mice showed high nuclear polymorphism and mitotic figures. However, there was no significant difference in the number of TILs between both the exposure and control groups. Therefore, there was no observed response to the treatment. Nevertheless, in the exposure group of TPBC mice, a reduction in mitotic figures was observed, indicating that exposure to ELF-EMF for two hours per day resulted in decreased tumor growth and a treatment response.

3.3. Gram Staining Results on Tumors

- The presence of rod-shaped bacterial entities with distinct nuclei around the tumor cells of TNBC and TPBC mice is observable. However, no significant change in the population of the microbiota was observed in both exposure and control groups in both mouse models.

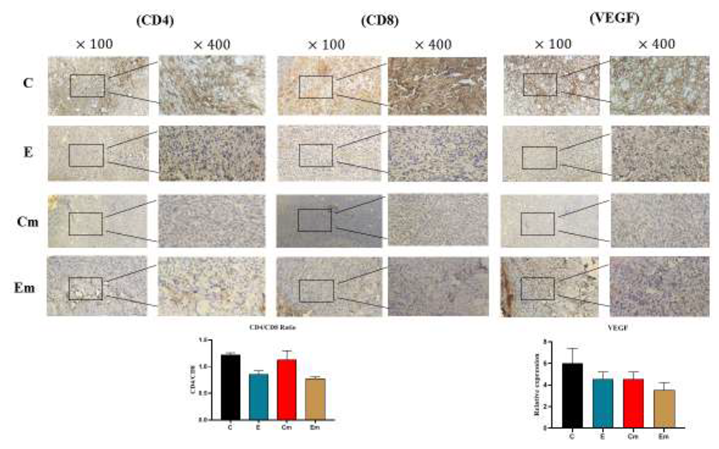

3.4. IHC Staining Results on Tumors

3.5. Real-time PCR results on tumors

4. Discussion

-

*Banerjee et al. used a microarray-based approach called the “PathoChip” to determine the microbial signature for different breast cancer subtypes [42].Banerjee et al. [42] identified the unique microbial signatures linked with triple-negative breast cancer.Polyoma viruses, herpesviruses, papilloma viruses, poxviruses, Arcanobacterium haemolyticum, Prevotella nigrescens, Pleistophora mulleris, Piedraia hortae, Trichuris trichura, Leishmania in triple-negative breast tissues are much more frequently than normal tissues* plasmodium-derived molecules have been associated with antitumor properties in adult mice in vivo and in vitro, and may be used as targets for tumor immunotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer [43] .

- The results of the study suggest that ELF-EMF exposure can be employed to reduce the intratumoral microbiota population in breast cancer patients. This approach could serve as an alternative treatment for infectious diseases or patients with TNBC characterized by the absence of cell surface receptors. In this study, we were limited in utilizing additional tests to examine the intratumoral microbiota population. Furthermore, the findings from this study can be extrapolated to human cancers along with in vivo studies.

5. Conclusions

References

- Knippel, R.J., J.L. Drewes, and C.L. Sears, The cancer microbiome: recent highlights and knowledge gaps. Cancer discovery, 2021. 11(10): p. 2378-2395. [CrossRef]

- Oliva, M., et al., Tumor-associated microbiome: where do we stand? International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021. 22(3): p. 1446.

- Thomas, R.M. and C. Jobin, The microbiome and cancer: is the ‘oncobiome’mirage real? Trends in cancer, 2015. 1(1): p. 24-35.

- Belkaid, Y. and S. Naik, Compartmentalized and systemic control of tissue immunity by commensals. Nature immunology, 2013. 14(7): p. 646-653. [CrossRef]

- Nejman, D., et al., The human tumor microbiome is composed of tumor type–specific intracellular bacteria. Science, 2020. 368(6494): p. 973-980. [CrossRef]

- Jayachandran, P., et al., Breast cancer and neurotransmitters: emerging insights on mechanisms and therapeutic directions. Oncogene, 2023. 42(9): p. 627-637. [CrossRef]

- Loizides, S. and A. Constantinidou, Triple negative breast cancer: Immunogenicity, tumor microenvironment, and immunotherapy. Frontiers in Genetics, 2023. 13: p. 1095839. [CrossRef]

- Schedin, T.B., V.F. Borges, and E. Shagisultanova, Overcoming therapeutic resistance of triple positive breast cancer with CDK4/6 inhibition. International journal of breast cancer, 2018. 2018.

- Thompson, K.J., et al., A comprehensive analysis of breast cancer microbiota and host gene expression. PloS one, 2017. 12(11): p. e0188873.

- Smrekar, K., A. Belyakov, and K. Jin, Crosstalk between triple negative breast cancer and microenvironment. Oncotarget, 2023. 14: p. 284. [CrossRef]

- Bayır, E., et al., The effects of different intensities, frequencies and exposure times of extremely low-frequency electromagnetic fields on the growth of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli O157: H7. Electromagnetic biology and medicine, 2015. 34(1): p. 14-18.

- Barati, M., et al., Cellular stress response to extremely low-frequency electromagnetic fields (ELF-EMF): An explanation for controversial effects of ELF-EMF on apoptosis. Cell Proliferation, 2021. 54(12): p. e13154. [CrossRef]

- Gualdi, G., et al., Wound repair and extremely low frequency-electromagnetic field: insight from in vitro study and potential clinical application. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021. 22(9): p. 5037. [CrossRef]

- Fojt, L., et al., Comparison of the low-frequency magnetic field effects on bacteria Escherichia coli, Leclercia adecarboxylata and Staphylococcus aureus. Bioelectrochemistry, 2004. 63(1-2): p. 337-341. [CrossRef]

- Segatore, B., et al., Evaluations of the effects of extremely low-frequency electromagnetic fields on growth and antibiotic susceptibility of Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. International Journal of Microbiology, 2012. 2012.

- Cahill, L.C., et al., Rapid virtual hematoxylin and eosin histology of breast tissue specimens using a compact fluorescence nonlinear microscope. Laboratory investigation, 2018. 98(1): p. 150-160. [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.D., et al., Hematoxylin and eosin staining for detecting biofilms: practical and cost-effective methods for predicting worse outcomes after endoscopic sinus surgery. Clinical and Experimental Otorhinolaryngology, 2014. 7(3): p. 193-197. [CrossRef]

- Becerra, S.C., et al., An optimized staining technique for the detection of Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria within tissue. BMC research notes, 2016. 9(1): p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Heymann, C.J., et al., The intratumoral microbiome: characterization methods and functional impact. Cancer letters, 2021. 522: p. 63-79. [CrossRef]

- Eisenhofer, R., et al., Contamination in low microbial biomass microbiome studies: issues and recommendations. Trends in microbiology, 2019. 27(2): p. 105-117. [CrossRef]

- Elie, C., et al., Comparison of DNA extraction methods for 16S rRNA gene sequencing in the analysis of the human gut microbiome. Scientific Reports, 2023. 13(1): p. 10279. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L., et al., Intratumoral microbiota: roles in cancer initiation, development and therapeutic efficacy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2023. 8(1): p. 35. [CrossRef]

- Fu, A., et al., Tumor-resident intracellular microbiota promotes metastatic colonization in breast cancer. Cell, 2022. 185(8): p. 1356-1372. e26. [CrossRef]

- Gluz, O., et al., Triple-negative breast cancer—current status and future directions. Annals of Oncology, 2009. 20(12): p. 1913-1927. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H., et al., A review of biological targets and therapeutic approaches in the management of triple-negative breast cancer. Journal of Advanced Research, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jin, C., et al., Commensal microbiota promote lung cancer development via γδ T cells. Cell, 2019. 176(5): p. 998-1013. e16.

- Geller, L.T. and R. Straussman, Intratumoral bacteria may elicit chemoresistance by metabolizing anticancer agents. Molecular & Cellular Oncology, 2018. 5(1): p. e1405139. [CrossRef]

- Moori, M., et al., Effects of 1Hz 100mT electromagnetic field on apoptosis induction and Bax/Bcl-2 expression ratio in breast cancer cells. Multidisciplinary Cancer Investigation, 2022. 6(1): p. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Xu, A., Q. Wang, and T. Lin, Low-frequency magnetic fields (LF-MFs) inhibit proliferation by triggering apoptosis and altering cell cycle distribution in breast cancer cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2020. 21(8): p. 2952. [CrossRef]

- Tatarov, I., et al., Effect of magnetic fields on tumor growth and viability. Comparative medicine, 2011. 61(4): p. 339-345.

- Raskov, H., et al., Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells in cancer and cancer immunotherapy. British journal of cancer, 2021. 124(2): p. 359-367. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C., et al., Stromal tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes evaluated on H&E-stained slides are an independent prognostic factor in epithelial ovarian cancer and ovarian serous carcinoma. Oncology letters, 2019. 17(5): p. 4557-4565. [CrossRef]

- Lakritz, J.R., et al., Beneficial bacteria stimulate host immune cells to counteract dietary and genetic predisposition to mammary cancer in mice. International journal of cancer, 2014. 135(3): p. 529-540. [CrossRef]

- Farhood, B., M. Najafi, and K. Mortezaee, CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes in cancer immunotherapy: A review. Journal of cellular physiology, 2019. 234(6): p. 8509-8521. [CrossRef]

- Umegaki, S., et al., Distinct role of CD8 cells and CD4 cells in antitumor immunity triggered by cell apoptosis using a Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase/ganciclovir system. Cancer Science, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Inai, T., et al., Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling in cancer causes loss of endothelial fenestrations, regression of tumor vessels, and appearance of basement membrane ghosts. The American journal of pathology, 2004. 165(1): p. 35-52. [CrossRef]

- Goel, H.L. and A.M. Mercurio, VEGF targets the tumour cell. Nature Reviews Cancer, 2013. 13(12): p. 871-882. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., et al., Influence of gut and intratumoral microbiota on the immune microenvironment and anti-cancer therapy. Pharmacological Research, 2021. 174: p. 105966. [CrossRef]

- Soto-Pantoja, D.R., et al., Diet alters entero-mammary signaling to regulate the breast microbiome and tumorigenesis. Cancer research, 2021. 81(14): p. 3890-3904. [CrossRef]

- Kong, F., et al., Abundance and metabolism disruptions of intratumoral microbiota by chemical and physical actions unfreeze tumor treatment resistance. Advanced Science, 2022. 9(7): p. 2105523. [CrossRef]

- Matson, V., C.S. Chervin, and T.F. Gajewski, Cancer and the microbiome—influence of the commensal microbiota on cancer, immune responses, and immunotherapy. Gastroenterology, 2021. 160(2): p. 600-613.

- Banerjee, S., et al., Distinct microbiological signatures associated with triple negative breast cancer. Scientific reports, 2015. 5(1): p. 15162.

- Junqueira, C., et al., Trypanosoma cruzi adjuvants potentiate T cell-mediated immunity induced by a NY-ESO-1 based antitumor vaccine. PloS one, 2012. 7(5): p. e36245. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).