Submitted:

08 October 2025

Posted:

13 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

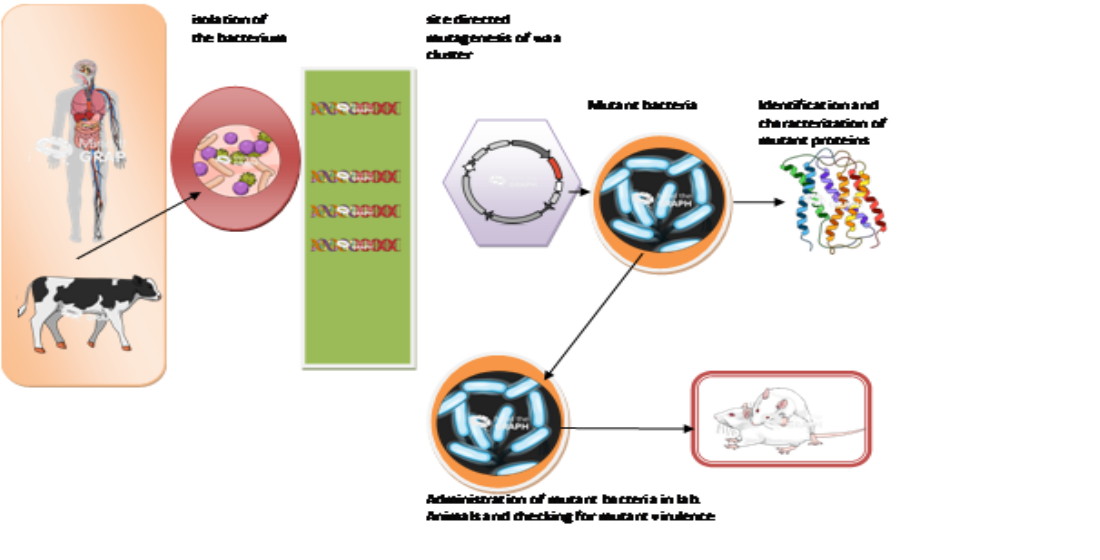

E. coli H7:O157, the causative pathogen of many disease outbreaks and cases of food poisoning, has been the subject of many studies. The bacterium's pathogenicity is highly associated with cell wall modifications and changes. A total of 20 fecal samples from patients who showed the typical symptoms of the infection tested positive for E. coli H7:O157 and another 20 samples from animals were also collected. The bacterium was isolated and identified using cultural and molecular methods. The waa K, waa L, and waa Y sites were subjected to site-directed mutagenesis, and the effect of these mutations were studied and analyzed through its influence on the pathogenicity compared to the wild type. We found that the invasiveness and morbidity of mutant E. coli H7:O157 increased significantly when ingested by laboratory animals. This may be attributed to waa K and waa L, since they led to a significant change in the transmembrane helix ratio compared to the wild type, enabling the uncontrolled release of the Shiga toxin into the infected animals, causing their death in 6 hours. Specific sites in the waa operon, namely waa K and waa L, play the leading role in controlling the progress of pathogenicity. Mutations in these sites may increase the virulence of this bacterium.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics and Participation in This Study

2.1.1. Animal Welfare and IRB Approval

2.1.2. Human Sample Collection Approval

2.1.3. Sample Collection

2.1.4. Isolation of E. coli O157:H7

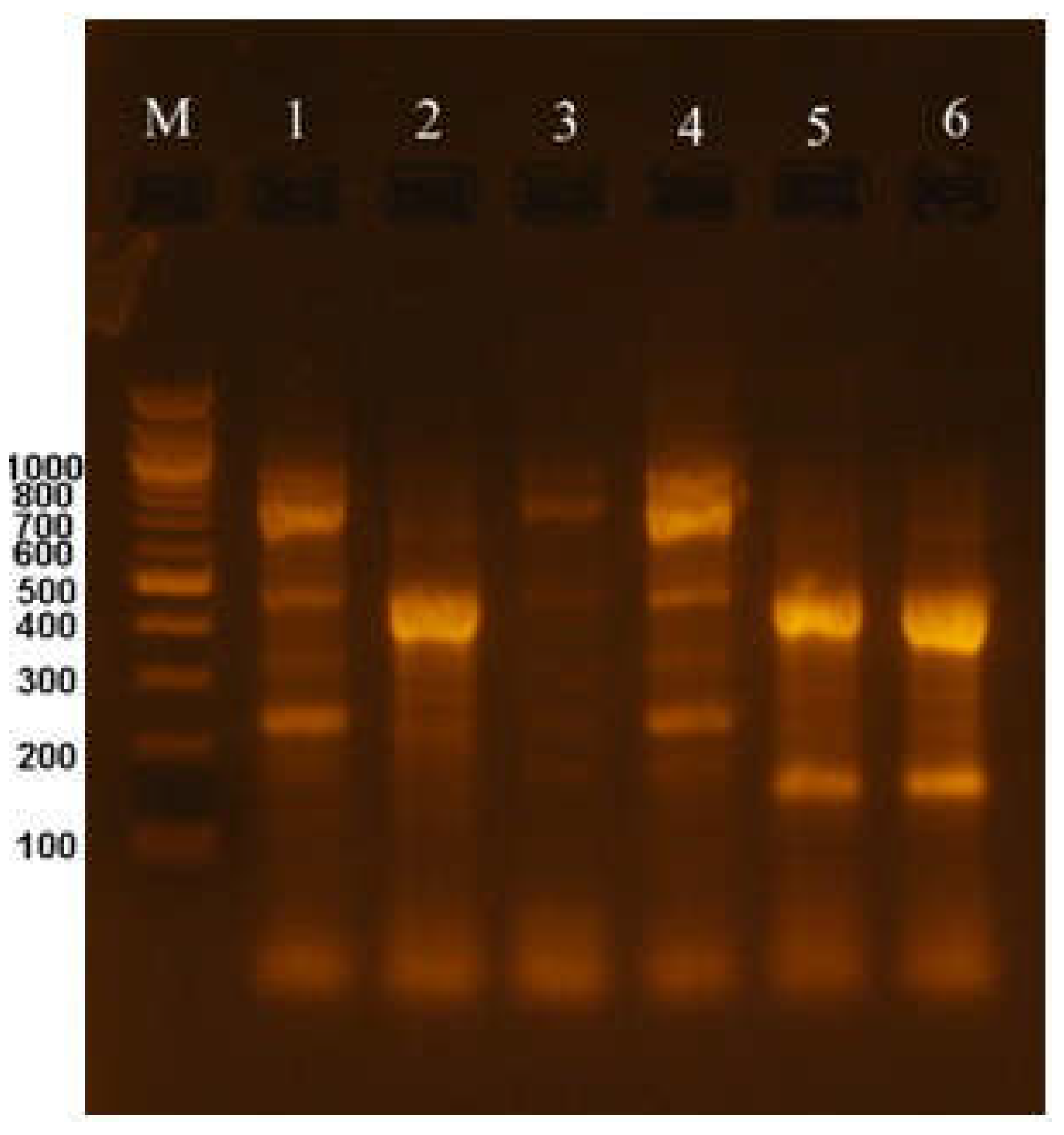

2.2. Molecular Identification of E. coli O157:H7

2.2.1. Extraction of DNA from Bacterial Cells

2.2.2. PCR Amplification of Specific E. coli O157:H7 Genes

2.2.3. The rpoB gene

2.2.4. The waa Gene

2.2.5. The Shiga Toxin Stx Gene

2.2.6. The rfbO Gene

2.2.7. Site-Directed Mutagenesis

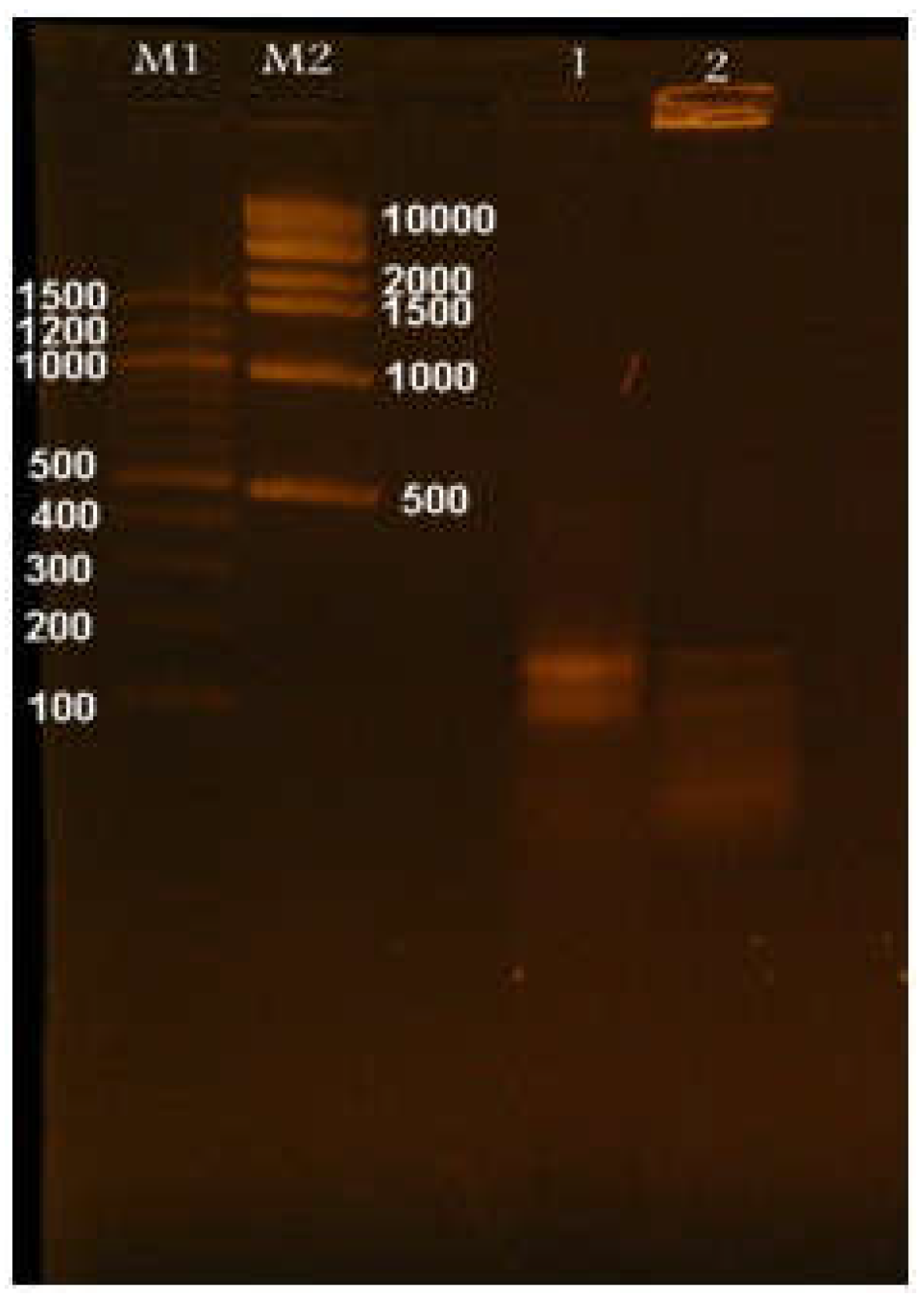

2.2.8. Cloning of the Mutated waa Gene

2.2.9. Transformation Procedure

2.2.10. Confirmation of Cloning and Transformation

2.2.11. Sequencing of PCR Products

2.2.12. Animal Experiment

2.2.13. Data Analysis and Bioinformatics

2.2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Isolation of E. coli O157:H7 and Morphological Characteristics

3.2. Molecular Identification and Classification of E. coli O157:H7

3.3. The waa Gene

3.4. The Shiga Toxin Gene stx

3.5. The rfbO Gene

3.6. Site-Directed Mutagenesis of the waa Gene

3.7. Cloning and Transformation of the Mutated waa Gene

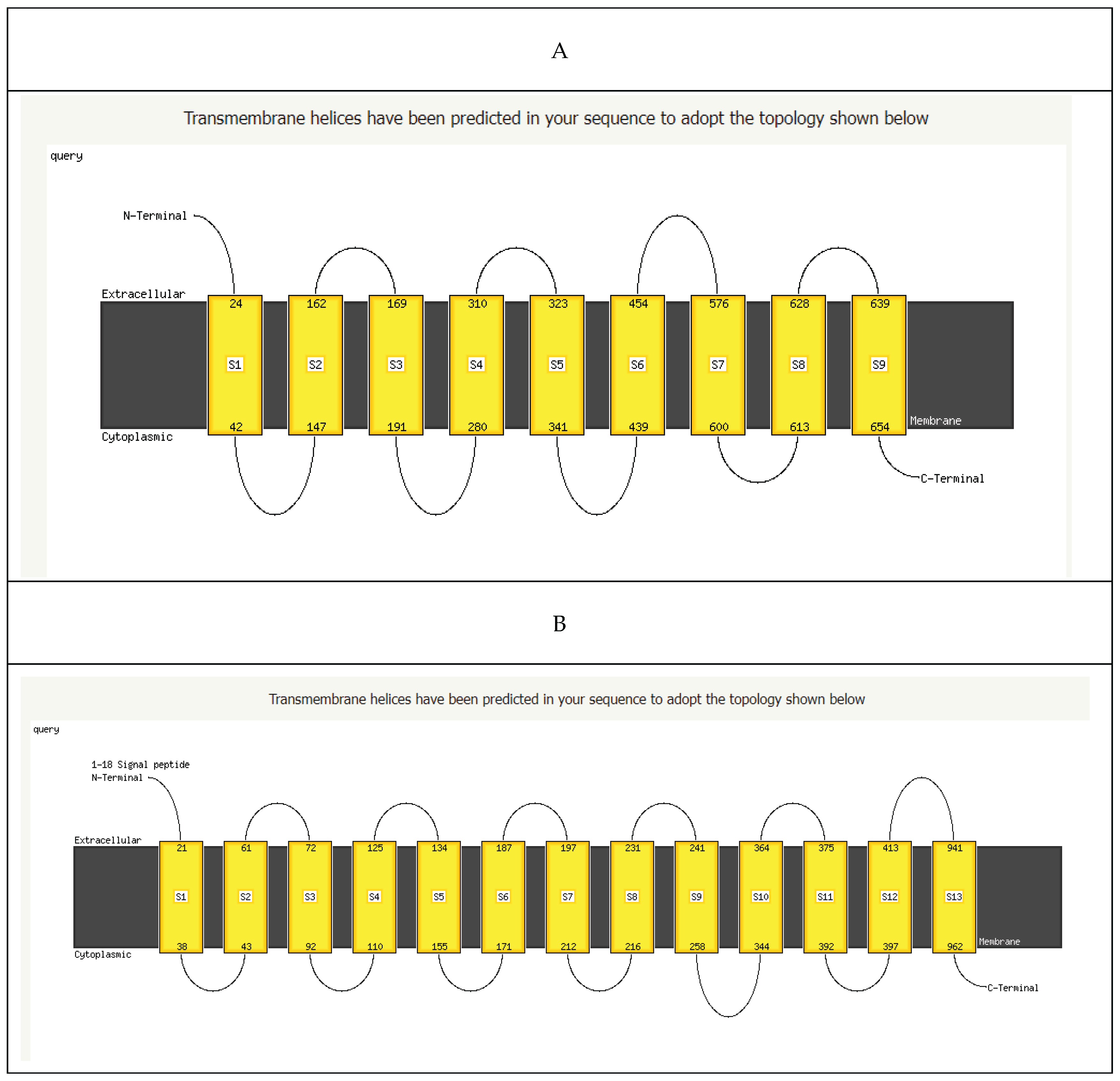

3.8. Interpretation of Site-Directed Mutagenesis of the waa Gene

3.8.1. Mutated waa K

3.8.2. The waa L Gene

3.8.3. The waa Y Gene

3.8.4. Cell Wall Topology of Mutated E. coli Compared to the Wild Type

3.9. Laboratory Animal Experiment and Statistical Analysis

3.9.1. Measuring Liver Function in Infected Animals

3.9.2. Measuring Kidney Function

4. Discussion

4.1. Cell Wall Topology

4.2. Effect of Mutation on E. coli O157:H7 Infectivity and Pathogenicity

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fontaine R, Arnon S, Martin W. Raw hamburger: An interstate common source of human salmonellosis. Am J Epidemiol. 1978, 107(1):36-45. [CrossRef]

- Blanco M, Blanco J, Mora A, Dahbi G, Alonso M, González E. Serotypes, virulence genes, and intimin types of Shiga toxin (verotoxin)-producing Escherichia coli isolates from cattle in Spain and identification of a new intimin variant gene (eae-xi). J Clin Microbiol. 2004, p. 645–651. [CrossRef]

- Al-Khyat F. Enterohaemorrhagic E. coli O157 in locally produced soft cheese. Iraqi J. Vet. Med. 2008, 32 (1); 88-99. [CrossRef]

- Guth B, Prado V, Rivas M. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. In: Torres AG, editor. Pathogenic Escherichia coli in Latin America. Galveston, TX, USA: Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Sealy Institute for Vaccine Sciences, University of Texas Medical Branch; 2010.

- Paton AW, Paton JC. Direct detection of Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli strains belonging to serogroups O111, O157, and O113 by multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1999; 37:3362–3365. [CrossRef]

- Heiman KE, Mody RK, Johnson SD, Griffin PM, Gould LH. Escherichia coli O157 outbreaks in the United States, 2003–2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(8). [CrossRef]

- Ahmed S. T., Jasim A.N., Ali A. M. Isolation and characterization E. coli O157:H7 from meat and cheese and detection of Stx1, Stx2, hlyA, eaeA using multiplex PCR. 2011. JOBRC. 5(2) p: 15-24. [CrossRef]

- Van TTH, Yidana Z, Smooker PM, Coloe PJ. Antibiotic use in food animals worldwide, with a focus on Africa: pluses and minuses. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020; 20:170–177. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed Z. A. Isolation and Identification of Escherichia coli O157:H7 from locally minced meat and imported minced and chicken meat. Iraqi J. Vet. Med. 2008, 32(1); 100-113. [CrossRef]

- Hasan J. M., Najim S. S. A review of the Prevalence of Enterohemorrhagic E. coli in Iraq. 2024. JOBRC. 18 (1) p: 33-39. [CrossRef]

- Khalil Z. K. Isolation and identification of Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella specious from raw beef and lamb meat in Baghdad by PCR. Iraqi Journal of Science, 2016, 57 (3B), 1891-1897.

- Lim JM, Singh SR, Duong MC, Legido-Quigley H, Hsu LY, Tam CC. Impact of national interventions to promote responsible antibiotic use: a systematic review. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020;75(1):14–29. [CrossRef]

- Nataro JP, Kaper JB. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11(1):142–201. doi:10.1128/CMR.11.1.142 37. Caprioli A, Morabito S, Brugere H, Oswald E. Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli: emerging issues on virulence and modes of transmission. Vet Res. 2005;36(3):289–311. doi:10.1051/vetres:2005002.

- Beata S, Michał T, Mateusz O, et al. Norepinephrine affects the interaction of adherent-invasive Escherichia coli with intestinal epithelial cells. Virulence. 2021; 12:630–637. [CrossRef]

- Thompson JS, Hodge DS, Borczyk AA. Rapid biochemical test to identify verocytotoxin-positive strains of Escherichia coli serotype O157. J Clin Microbiol. 1990; 28:2165–2168. [CrossRef]

- Perna NT, Plunkett G, Burland V, Mau B, Glasner JD, Rose DJ, et al. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature. 2001;409:529–533. [CrossRef]

- Dobrindt U, Agerer F, Michaelis K, Janka A, Buchrieser C, Samuelson M, et al. Analysis of genome plasticity in pathogenic and commensal Escherichia coli isolates by use of DNA arrays. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1831–1840. [CrossRef]

- Wick LM, Qi W, Lacher DW, Whittam TS. Evolution of genomic content in the stepwise emergence of Escherichia coli O157:H7. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:1783–1791. [CrossRef]

- Amézquita-López BA, Quiñones B, Soto-Beltrán M, et al. Antimicrobial resistance profiles of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 and non-O157 recovered from domestic farm animals in rural communities in Northwestern Mexico. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2016;5(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Aklilu, F., Daniel, K., & Ashenaf, K. (2017). Prevalence and antibiogram of Escherichia coli O157 isolated from bovine in Jimma, Ethiopia: Abattoir-based survey. Ethiopian Veterinary Journal, 21(2), 109–120. [CrossRef]

- Aschalew Ayisheshim Tarekegn, Birhan Agimas Mitiku, Yeshwas Ferede Alemu. Escherichia coli O157:H7 beef carcass contamination and its antibiotic resistance in Awi Zone, Northwest Ethiopia. 2023, Food Sci Nutr. 2023;11:6140–6150. [CrossRef]

- Gambushe S. M., Zishiri O., Zowalaty M. E El. Review of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Prevalence, Pathogenicity, Heavy Metal and Antimicrobial Resistance, African Perspective. Infection and Drug Resistance, 2022:15 4645–4673. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee S, Lo K, Ojkic N, Stephens R, Scherer NF, Dinner AR. 2021. Mechanical feedback promotes bacterial adaptation to antibiotics. Nat Phys 17:403–409. [CrossRef]

- Harris LK, Theriot JA. 2016. Relative rates of surface and volume synthesis set bacterial cell size. Cell 165:1479–1492. [CrossRef]

- Ojkic N, Banerjee S. 2021. Bacterial cell shape control by nutrient-dependent synthesis of cell division inhibitors. Biophys J 120:2079–2084. [CrossRef]

- Nikola Ojkica, Diana Serbanescua, Shiladitya Banerjee. Antibiotic Resistance via Bacterial Cell Shape-Shifting. ASM, May/June 2022 Volume 13 Issue 3 e00659-22. [CrossRef]

- Nikolic P. and Mudgil P. The Cell Wall, Cell Membrane and Virulence Factors of Staphylococcus aureus and Their Role in Antibiotic Resistance. Microorganisms 2023, 11(2), 259. [CrossRef]

- WHO estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases: foodborne disease burden epidemiology reference group 2007–2015.

- Sndra B. March and Samuel R. Sorbitol-MacConkey Medium for Detection of Escherichia coli 0157:H7 Associated with Hemorrhagic Colitis. JOURNAL OF CLINICAL MICROBIOLOGY, 1986, p. 869-872. [CrossRef]

- Dagny Jayne Leininger, Jerry Russel Roberson, Franc¸ois Elvinger. Use of eosin methylene blue agar to differentiate Escherichia coli from other gram-negative mastitis pathogens. J Vet Diagn Invest 13:273–275 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Ally C. Antony, Mini K. Paul, Reshma Silvester, Aneesa P.A., Suresh K., Divya P.S., Simmy Paul, Fathima P.A. and Mohamed Hatha Abdulla. Comparative Evaluation of EMB Agar and Hicrome E. coli Agar for Differentiation of Green Metallic Sheen Producing Non-E. coli and Typical E. coli Colonies from Food and Environmental SamplesJ. Pure.App. Microbiol. 2016, 10,4 p. 2863-2870. [CrossRef]

- Rani A., Ravindran V. B., Surapaneni A., Mantri N., Ball A. S. Review: Trends in point-of-care diagnosis for Escherichia coli O157:H7 in food and water. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 349, 2 2021, 109233. [CrossRef]

- Pagnout C., Sohm B., Razafitianamaharavo A., Caillet C., Offroy M., Leduc M., Gendre H., Jomini S., Beaussart A., Bauda P., Duval J. F L Pleiotropic effects of rfa-gene mutations on Escherichia coli envelope properties. Sci Rep. 2019; 4;9:9696. [CrossRef]

- Raetz, C.R. ∙ Whitfield, C. Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2002; 71:635-700. [CrossRef]

- Han W., Wu B., Li L., Zhao G., Woodward R., Pettit N., Cai L., Thon V., Wang P. Defining Function of Lipopolysaccharide O-antigen Ligase WaaL Using Chemoenzymatically Synthesized Substrates. Microbiology. 2012; 287(8),5357-5365. [CrossRef]

- Abeyrathne P. D, Daniels C., Poon K. K H, Matewish M. J, 1, Craig Daniels 1,†, Karen K H Poon 1, Matewish M. J, Lam J. S. Functional Characterization of WaaL, a Ligase Associated with Linking O-Antigen Polysaccharide to the Core of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Lipopolysaccharide. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(9):3002–3012. [CrossRef]

- Klena, J. D., Ashford, R. S., II, and Schnaitman, C. A. (1992) J. Bacteriol. 174; 7297-7307.

- Kaniuk, N. A., M. A. Monteiro, C. T. Parker, and C. Whitfield. Molecular diversity of the genetic loci responsible for lipopolysaccharide core oligosaccharide assembly within the genus Salmonella. Mol. Microbiol. 2002; 46:1305-1318. [CrossRef]

- Frirdich E., Lindner B., Holst O., Whitfield C. Overexpression of the waaZ Gene Leads to Modification of the Structure of the Inner Core Region of Escherichia coli Lipopolysaccharide, Truncation of the Outer Core, and Reduction of the Amount of O Polysaccharide on the Cell Surface. J Bacteriol. 2003; 185(5):1659–1671. [CrossRef]

- Yethon J. A., Heinrichs D., Monteiro M. A., Perry M. B., Whitfield C. Involvement of waaY, waaQ, and waaP in the Modification of Escherichia coli Lipopolysaccharide and Their Role in the Formation of a Stable Outer Membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 1998; 273(41), 26310-26316. [CrossRef]

- Taylor C. M, Goldrick M., Lord L., Roberts I. S . Mutations in the waaR Gene of Escherichia coli Which Disrupt Lipopolysaccharide Outer Core Biosynthesis Affect Cell Surface Retention of Group 2 Capsular Polysaccharides. J Bacteriol. 2006; 188(3):1165–1168. [CrossRef]

- Al wendawi SH. A., Al Rekaby S.M. THE EFFECIENCY OF ENTERIC LACTOBACILLUS IN PREVENTING HEMORRHAGIC COLITIS AND BLOCKING SHIGA TOXINS PRODUCTIONS IN RATS MODELS INFECTED WITH ENTEROHEMORRHAGIC ESCHERICHIA COLI (EHEC). Iraqi Journal of Agricultural Sciences.2021; 52(6):1346-1355. [CrossRef]

- Al-Taii D. H. F. Effects of E. coli O157:H7 Experimental Infections on Rabbits. Iraqi J. Vet. Med. 2019; 43 (1), 34-42. [CrossRef]

- Wang J., Ma W., Wang X. Insights into the structure of Escherichia coli outer membrane as the target for engineering microbial cell factories. Microb Cell Fact. 2021; 20:73. [CrossRef]

- Kaper, J. B., Nataro, J. P. & Mobley, H. L. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 2004; 2, 123–140. [CrossRef]

- Croxen M. A. and Finlay B. B. Molecular mechanisms of Escherichia coli pathogenicity. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2010; 8, 26–38. [CrossRef]

- Sora V. M., Meroni G., Martino P. A., Soggiu A., Bonizzi L. and, Zecconi A. Extraintestinal Pathogenic Escherichia coli: Virulence Factors and Antibiotic Resistance. Pathogens 2021, 10(11), 1355. [CrossRef]

- Abdul khaleq M. A., Abd A.H., Dhahi M. A. Efficacy of Combination of Meropenem with Gentamicin, and Amikacin against Resistant E. coli Isolated from Patients with UTIs: in vitro Study. Iraqi J Pharm Sci; 2011, 20 (2), 66-74. [CrossRef]

- Khan Md F., Rashid S. S. Molecular Characterization of Plasmid-Mediated Non-O157 Verotoxigenic Escherichia coli Isolated from Infants and Children with Diarrhea. Baghdad Science Journal. 2020, 17(3):710-719. [CrossRef]

- Wang X., Yu D., Chui L., Zhou T., Feng Y., Cao Y. and Zhi S. A Comprehensive Review on Shiga Toxin Subtypes and Their Niche-Related Distribution Characteristics in Shiga-Toxin-Producing E. coli and Other Bacterial Hosts. Microorganisms 2024, 12(4), 687. [CrossRef]

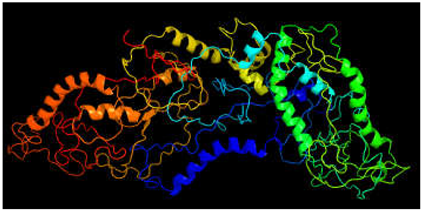

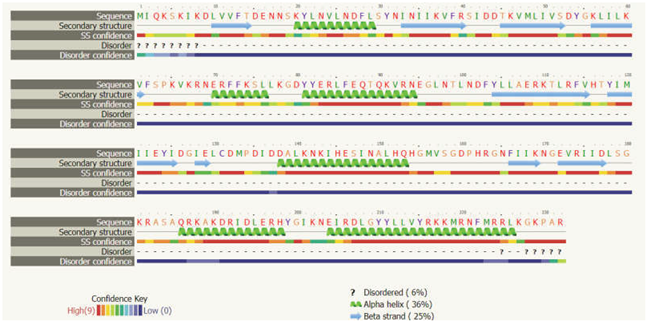

| The 3D structure of mutated waa gene | Expected biological function | ||

image colored by rainbow N → C terminus

|

Putative membrane antigen | ||

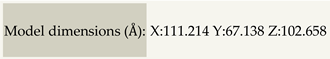

| The secondary structure of mutated waa gene | |||

| |||

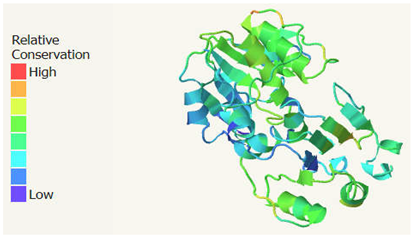

| Function conservation of mutated waa gene | Conserve amino acid residues in mutated protein | Position in the sequence | |

| Uncharacterized | |||

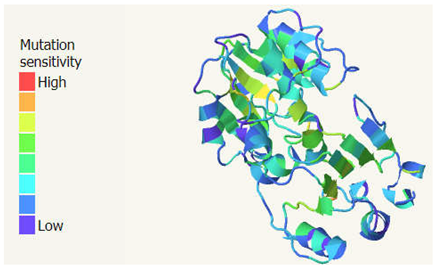

| Mutational sensitivity of mutated waa gene | Highly sensitive amino acid residues in mutated protein | Position in the sequence | |

| Uncharacterized | |||

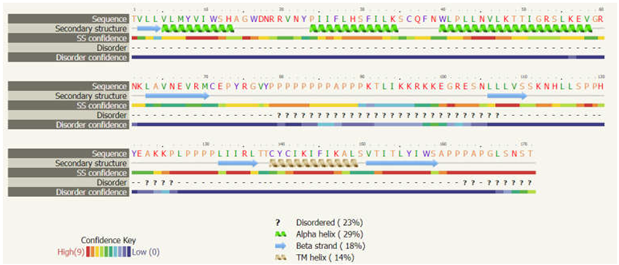

| The 3D structure of wild type cell wall | Expected biological function | ||

image colored by rainbow N → C terminus

|

Single-Particle Cryo-EM Structure of the waa L O-antigen ligase in its ligand bound state, lipopolysaccharide heptosyltransferase-1 |

||

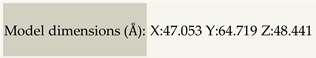

| The secondary structure of wild type waa gene | |||

| |||

| Function conservation of WILD type waa gene | Conserve amino acid residues in wild type protein | Position in the sequence | |

|

W, Y, Y, Y, P, R, R, Y, P, H, N, Y, H, D, F, D, H, W, E, A, D, P, Y, N, E, Y, Y | 88, 106, 137, 152, 218, 265, 288, 292, 303, 380, 239, 368, 466, 529, 565, 706, 711, 737, 889, 951, 970, 999, 1013, 1015, 1039, 1050, 1057 | |

| Mutational sensitivity of mutated waa gene | Highly sensitive amino acid residues in mutated protein | Position in the sequence | |

|

H, W, Y, R, Q, P, R, G, R, Y, P, H, H, N, G, G, K, D, P, | 9, 88, 152, 161, 115, 118, 165, 186, 288, 292, 303, 336, 338, 339, 349, 352, 539, 634 | |

| Mutated cell wall (733 residues) | Wild-type cell wall (1453 residues) | ||||

| Location on the cell wall | A.A. sequence | Type of helix | Location of A. A. residue | A.A. sequence | Type of helix |

| Outside | 1-19 | α / β | Inside | 1-19 | α / β |

| 20-42 | TMhelix | 20-37 | TMhelix | ||

| Inside | 43-144 | α / β | Outside | 38-40 | α / β |

| 145-162 | TMhelix | 41-60 | TMhelix | ||

| Outside | 163-166 | α / β | Inside | 61-71 | α / β |

| 167-186 | TMhelix | 72-91 | TMhelix | ||

| Inside | 187-290 | α / β | Outside | 92-105 | α / β |

| 291-310 | TMhelix | 106-128 | TMhelix | ||

| Outside | 311-319 | α / β | Inside | 129-134 | α / β |

| Inside | 320-436 | α / β | 135-157 | TMhelix | |

| 437-459 | TMhelix | Outside | 158-166 | α / β | |

| Outside | 460-733 | α / β | 167-189 | TMhelix | |

| Inside | 190-195 | α / β | |||

| 196-213 | TMhelix | ||||

| Outside | 214-239 | α / β | |||

| 240-259 | TMhelix | ||||

| Inside | 260-345 | α / β | |||

| 346-368 | TMhelix | ||||

| Outside | 369-371 | α / β | |||

| 372-394 | TMhelix | ||||

| Inside | 395-398 | α / β | |||

| 399-418 | TMhelix | ||||

| Outside | 419-1453 | α / β | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).