Introduction

Bacterial resistance to antibiotics is one of the major threats to global public health, with several million deaths estimated each year. Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly its western region, appears to be especially affected by this phenomenon [

1]. However, even industrialized countries experience significant health and economic consequences [

2,

3].

Among the primary causes of this resistance are the excessive and inappropriate use of antibiotics in both human and animal health, poor management stewardship, and the intrinsic resistance specific to certain bacterial species [

4].

In 2019,

Escherichia coli (E. coli) was one of the six pathogens responsible for the highest number of deaths related to antibiotic resistance, ranking first [

1]. As a member of the

Enterobacteriaceae family,

E. coli is a commensal bacterium in the mammalian digestive tract. While most strains are harmless, some are pathogenic and can cause severe intestinal or extra-intestinal infections [

5]. The World Health Organization (WHO) ranks

E. coli, alongside other

Enterobacteriaceae, among the priority pathogens due to the growing threat they pose to human health [

6].

E. coli is a common cause of diarrhea in children worldwide. In Mali, this bacterium is implicated in more than 30% of diarrhea cases in children under five years of age. These strains show increased resistance to several classes of antibiotics, notably beta-lactams and quinolones, although they remain relatively sensitive to imipenem, a carbapenem [

7]. Moreover, multiple multidrug-resistant strains have been isolated from children suffering from acute diarrhea [

8].

Beyond its multidrug-resistant profile,

E. coli also plays a key role as a reservoir of resistance genes, due to its ability to acquire such genes from other bacteria and transmit them through horizontal gene transfer mechanisms [

9,

10]. This resistance is more pronounced in clinical strains compared to environmental strains[

11].

In this context, this study aims to characterize the molecular profile of virulence and antibiotic resistance genes in clinical E. coli strains, with a particular focus on carbapenems, a class that remains understudied in Mali.

Materials and Method

The study focused on 98 clinical E. coli isolates collected from stool samples of patients between 2020 and 2021 at the laboratory of the CHU of Point G, Bamako, Mali, and stored at -80 °C. The isolates were subsequently analyzed at the Laboratory of Applied Molecular Biology (LBMA) using standard PCR.

Molecular analyses included screening for DEC-specific virulence genes, detection of resistance genes across various antibiotic classes, and identification of class 1, 2, and 3 integrons (

Table 1).

Frozen isolates were thawed and cultured on Mueller-Hinton (MH) agar for DNA extraction. Then, a full loop of fresh pure E. coli culture was stored at -80 °C in 1.5% (v/v) glycerol in enumeration broth for further analysis.

DNA Extraction

Reference strains were provided by the National Institute of Public Health (NIPH) of Mali. DNA was extracted from E. coli isolates and the reference strain using a full loop of colonies in 100 µL of ultrapure water following the Salting-out method. The purified DNA was eluted in 70 µL of TE buffer and stored at -20 °C for further amplification.

Identification of Virulence Genes

Strains harboring at least one DEC-associated virulence gene were classified as Diarrheagenic

E. coli (DEC). Several genes characteristic of Diarrheagenic

E. coli (DEC) were targeted (see

Table 1):

bfpA and eae for typical enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC),

agg and aaic for enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC),

lt and st for enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC).

Three microliters of DNA from the reference strains provided by the NIPH, the negative control (sterile ultrapure water), and the

E. coli isolates were used for multiplex PCR with specific primers (

Table 1), as described by Vilchez S et al., 2009 [

8].

Additionally, to confirm the multiplex PCR results, DNA extracted from freshly cultured colonies on MH agar was subjected to single PCR. Each specific primer was tested independently in single PCR to confirm suspected DEC isolates identified by multiplex PCR.

Identification of Resistance and Integron Genes

Specific resistance genes to different antibiotic families were evaluated: ESBL genes (Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamases) for beta-lactams; blaNDM and blaIMP for carbapenems; tetA for tetracyclines; qnrS1 for quinolones; catA1 for chloramphenicols, and aphA3 for aminoglycosides.

PCR was used to detect the presence of antibiotic resistance genes, as well as class 1, 2, and 3 integrons genes, and to assess their distribution among the isolates. Integrons play a major role in the acquisition, expression, and dissemination of antibiotic resistance, particularly resistance integrons.

All amplification was carried out using the PTC 200 thermocycler (MJ Research, USA) with specific primer sequences as listed in

Table 1. The reaction total volume was 25 µl containing 3 µL of DNA, 1x Buffer (Mg

2+ free), 3 mM MgCl

2, 0.4 mM deoxynucleotide triphospahtes (dNTPs) (Invitrogen, USA), 0.4 μM of each primer, and 0.025 U of Taq polymerase (Invitrogen, USA).

The PCR program for all reactions was as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 seconds (denaturation), annealing at 44 to 60 °C for 45 seconds (variable according to the specific primers), and 72 °C for 1 minute (extension). The annealing temperatures were: OXA (44 °C), QnrS1 and IMP (50 °C), NDM (52 °C), SHV (60 °C), TEM (55 °C), catA (59 °C), tetA (55 °C), CTX-M (57.2 °C), aphA-3 (51.9 °C), Int1 (59 °C), Int2 (55 °C), and Int3 (57 °C), respectively. A final elongation step was performed at 72 °C for 10 minutes. All PCR products were visualized on a 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

Table 1.

List of primers Used.

Table 1.

List of primers Used.

| DEC type |

Target gene |

Primer |

Primer sequence 5’ - 3’ |

PCR product Size bp |

Reference |

| ETEC |

eltB |

LT-F |

TCTCTATGTGCATACGGAGC |

322 |

[12] |

| |

|

LT-R |

CCATACTGATTGCCGCAAT |

|

|

| |

estA |

ST-F |

GTCAAACCAGTA(G/A)GGTCTTCAAAA |

147 |

[12] |

| |

|

ST-R |

CCCGGTACA(G/A)GGAGGATTACAACA |

|

|

| EHEC |

vt1 |

VT1-F |

GAAGAGTCCGTGGGATTAC |

130 |

[12] |

| |

|

VT1-R |

AGCGATGCAGCTATTAATAA |

|

|

| |

vt2 |

VT2-F |

ACCGTTTTTCAGATTTT(G/A)CACATA |

298 |

[12] |

| |

|

VT2-R |

TACACAGGAGCAGTTTCAGACAGT |

|

|

| EPEC |

EaeA |

Eae-F |

CACACGAATAAACTGACTAAAATG |

376 |

[12] |

| |

|

Eae-R |

AAAAACGCTGACCCGCACCTAAAT |

|

|

| |

bfpA |

bfpA-F |

TTCTTGGTGCTTGCGTGTCTTTT |

367 |

[12] |

| |

|

bfpA-R |

TTTTGTTTGTTGTATCTTTGTAA |

|

|

| EIEC |

Ial |

SHIG-F |

CTGGTAGGTATGGTGAGG |

320 |

[12] |

| |

|

SHIG-R |

CCAGGCCAACAATTATTTCC |

|

|

| EAEC |

pCVD432 |

EA-F |

CTGGCGAAAGACTGTATCAT |

630 |

[12] |

| |

|

EA-R |

AAATGTATAGAAATCCGCTGTT |

|

|

| Resistance genes |

blaOXA

|

OXA 1-F |

ATGAAAAACACAATACATATC |

890 |

[13] |

| |

|

OXA 1-R |

AATTTAGTGTGTTTAGAATGG |

|

|

| |

blaSHV

|

SHV-F |

TTATCTCCCTGTTAGCCACC |

800 |

[13,14] |

| |

|

SHV-R |

GATTTGCTGATTTCGCTCGG |

|

|

| |

blaTEM

|

TEM-F |

ATAAAATTCTTGAAGACGAAA |

850 |

[13] |

| |

|

TEM-R |

GACAGTTACCAATGCTTAATC |

|

|

| |

blaCTX-M-3/15/22

|

CTX-M-F |

GTTACAATGTGTGAGAAGCAG |

593 |

[15] |

| |

|

CTX-M-R |

CCGTTTCCGCTATTACAAAC |

|

|

| |

catA1 |

catA 1-F |

CGCCTGATGAATGCTCATCCG |

450 |

[14] |

| |

|

catA 1-R |

CCTGCCACTCATCGCAGTAC |

|

|

| |

tetA |

tetA-F |

GTAATTCTGAGCACTGTCGC |

956 |

[14] |

| |

|

tetA-R |

CTGCCTGGACAACATTGCTT |

|

|

| |

aphA-3 |

aphA-3-F |

GGGACCACCTATGATGTGGAACG |

600 |

[14] |

| |

|

aphA-3-R |

CAGGCTTGATCCCCAGTAAGTC |

|

[16] |

| |

blaNDM

|

NDM-1_F |

GGTTTGGCGATCTGGTTTTC |

621 |

|

| |

|

NDM-1_R |

CGGAATGGCTCATCACGATC |

|

|

| |

blaIMP

|

IMP_F |

CACTTGGTTTGTGGAACGTG |

192 |

This study

GenBank: CP090265.1

|

| |

|

IMP_R |

CAATAGTTAACCCCGCCAAA |

|

|

| |

QnrS1 |

QnrS1_F |

ACGCACGGAACTCTATACCG |

154 |

This study

GenBank: CP090265.1

|

| |

|

QnrS1_R |

ACGACATTCGTCAACTGCAA |

|

|

| Integron |

intI1 |

Int1_F |

ACATGTGATGGCGACGCACGA |

580 |

[17] |

| |

|

Int1_R |

ATTTCTGTCCTGGCTGGCGA |

|

|

| |

intI2 |

Int2_F |

CACGGATATGCGACAAAAAGGT |

806 |

[17] |

| |

|

Int2_R |

GTAGCAAACGACTGACGAAATG |

|

|

| |

intI3 |

Int3_F |

AACTCTTGCACCGTTCGGAT |

542 |

This study

GenBank: CP047278.1

|

| |

|

Int3_R |

CAGGAGGTTCAGACGTTGCT |

|

|

Sequencing

Among isolates carrying the blaNDM gene, one isolate was sequenced by the Sanger to identify mutations associated with carbapenem resistance.

The amplified product was purified using Exonuclease I and Alkaline Phosphatase enzymes, followed by thermal cycling and ethanol precipitation. Sequencing was performed on the CEQ™ 8000 DNA Analyzer (Beckman Coulter). The resulting sequence was compared to database entries using the NCBI BLAST search tool. Mutations were analyzed using Geneious Prime 2023.0 software.

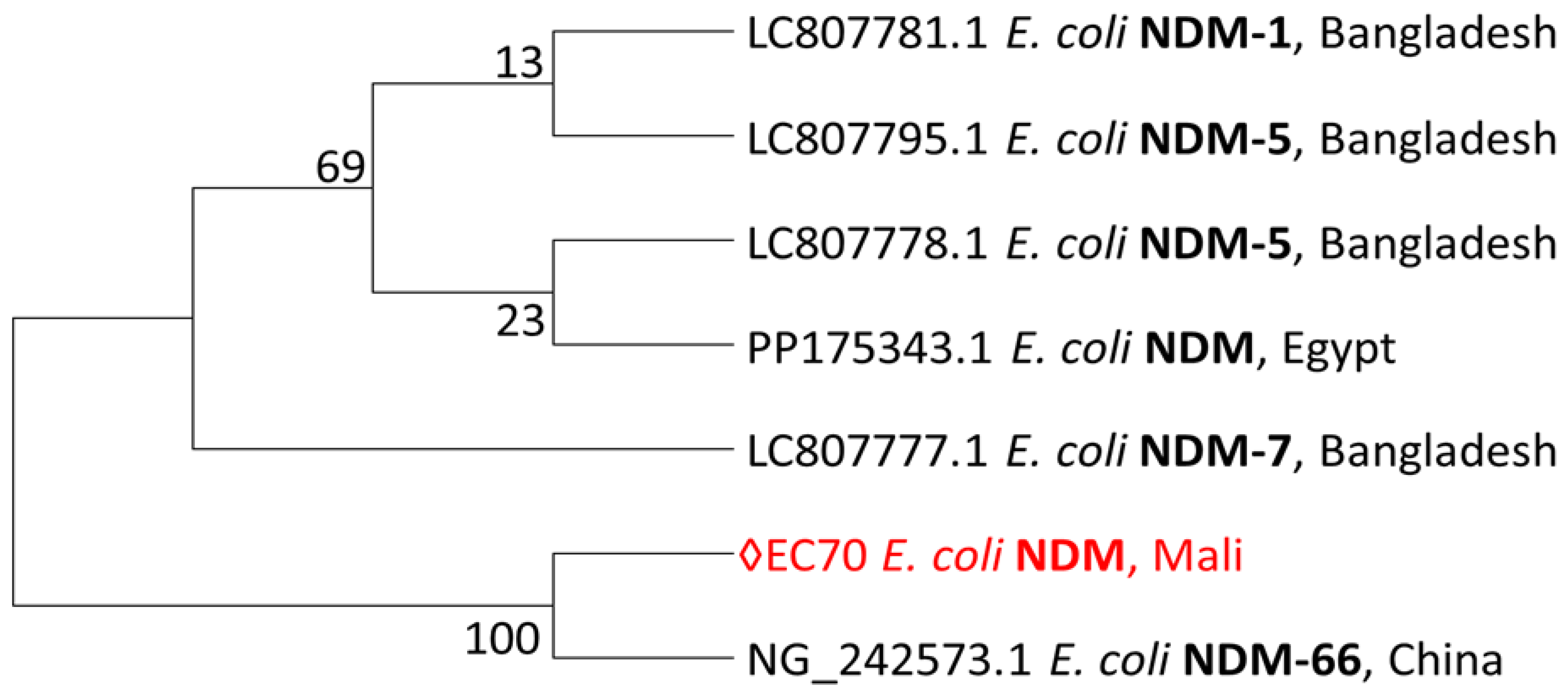

Phylogenetic analysis

We retrieved the most closely related sequences from GenBank as of June 3rd, 2024. The sequence dataset was aligned using BioEdit, version 7.7.1 (5/10/2021). Based on the resulting alignments, we performed a maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic reconstruction using MEGA version 7.0.26, applying the Tamura-Nei model and assessing branch support with 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using STATA software version 14.0. The Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used, as appropriate, to determine the statistical significance of the data. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Beta-lactam resistance was defined as the presence of at least one beta-lactam resistance gene. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) was defined as the presence of at least one resistance gene from three different classes of antibiotics. Figures were generated using Excel and the online platform Flourish (

https://flourish.studio/), employing chord diagrams to illustrate associations between variables in cases of co-infections, multi-resistance, and the presence of different integrons.

Results

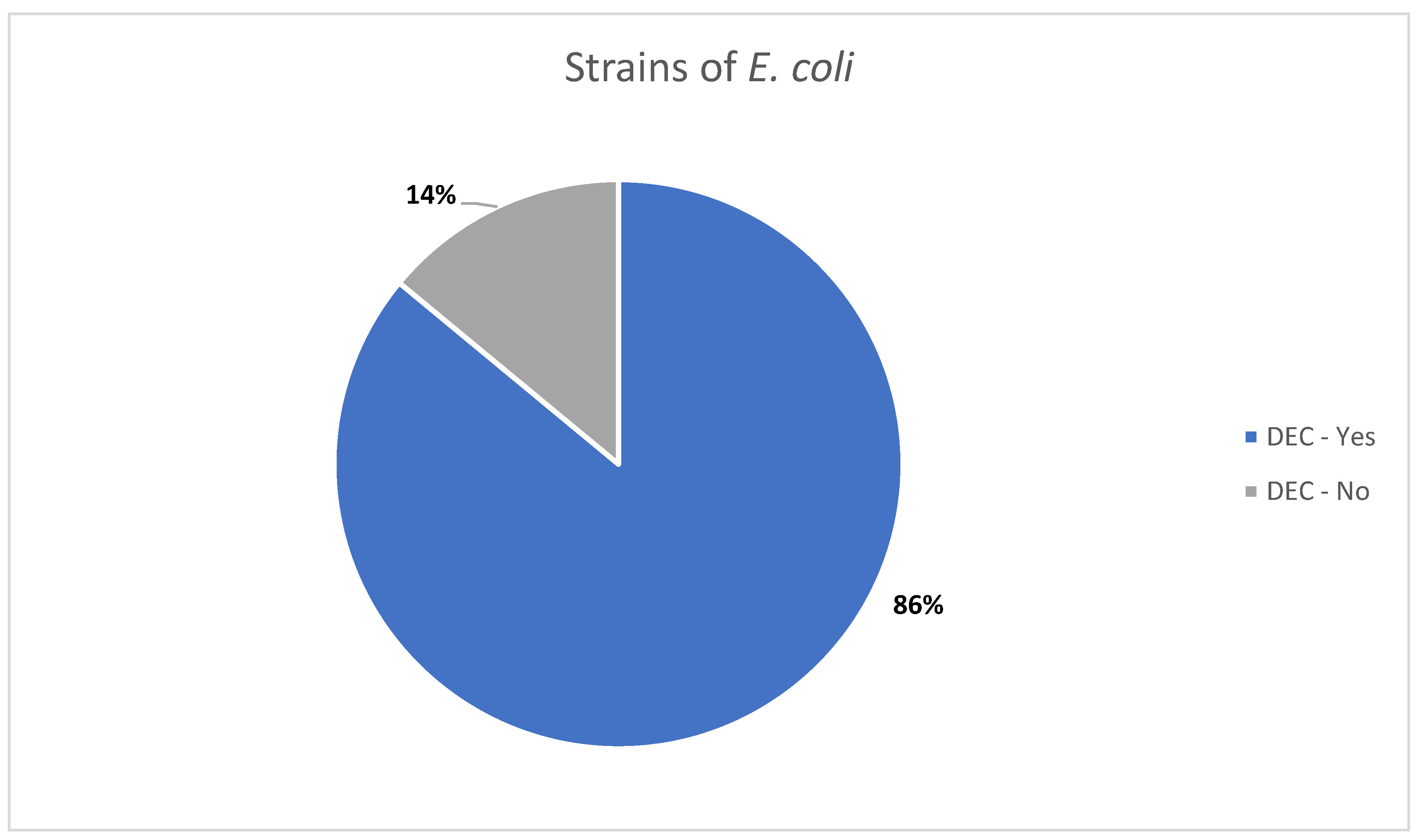

This study focused on the molecular characterization of virulence and antibiotic resistance genes profiles of

E. coli strains isolated in a clinical setting. Of the 98 isolate, 84 (approximately 86%) were identified as DEC, based on the detection of at least one specific virulence gene (

Figure 1).

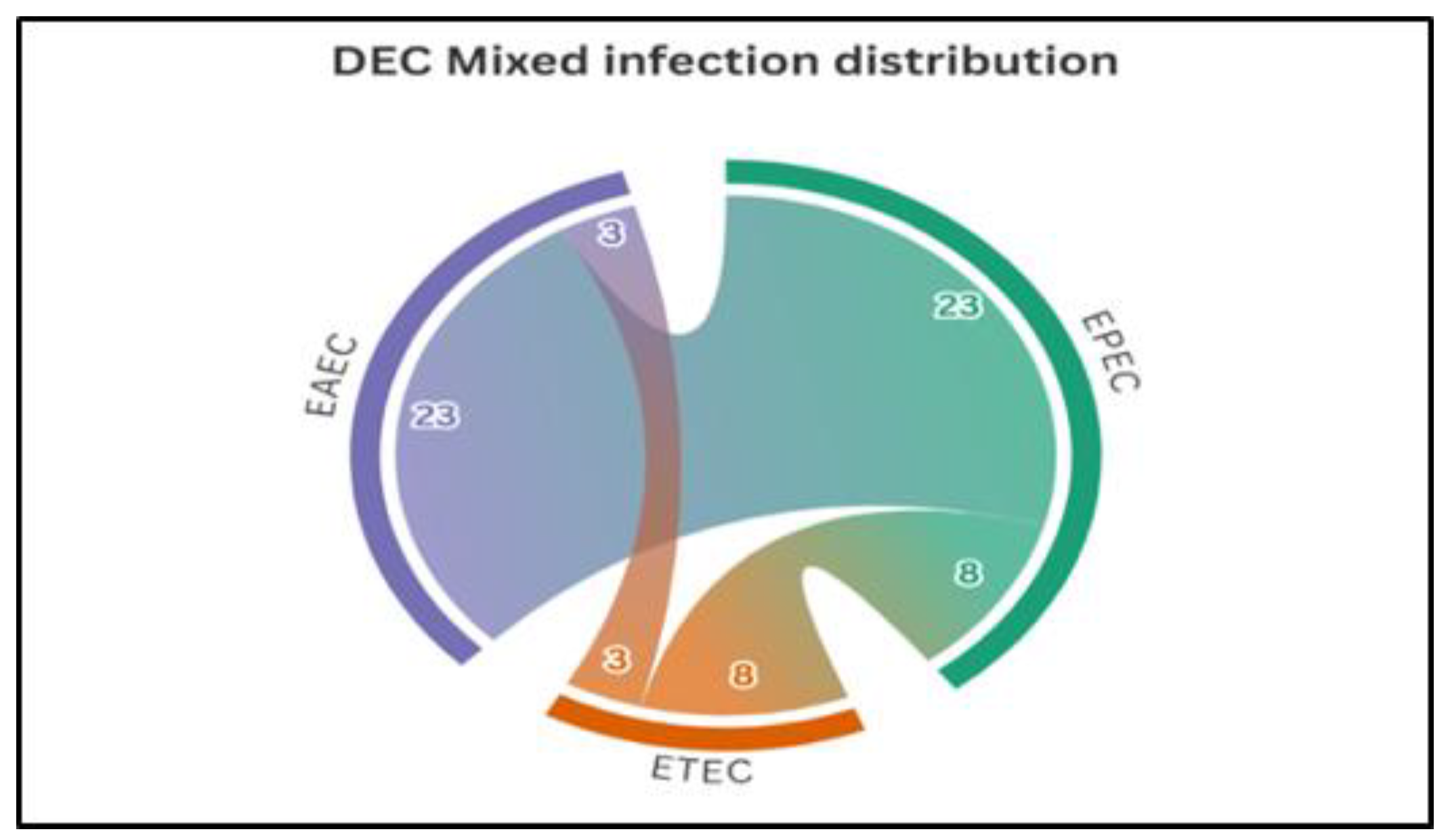

Among the 84 DEC strains identified, 50% were mono-infections, predominantly EPEC (21.4%), followed by EAEC (20.2%) and ETEC (8.3%). The remaining 50% involved mixed infections, with the EAEC–EPEC combination being the most common (27.4%), followed by EPEC–ETEC (9.5%), EAEC–ETEC (3.6%), and the triple combination EAEC–EPEC–ETEC (9.5%) (

Figure 2).

Detection of resistance genes

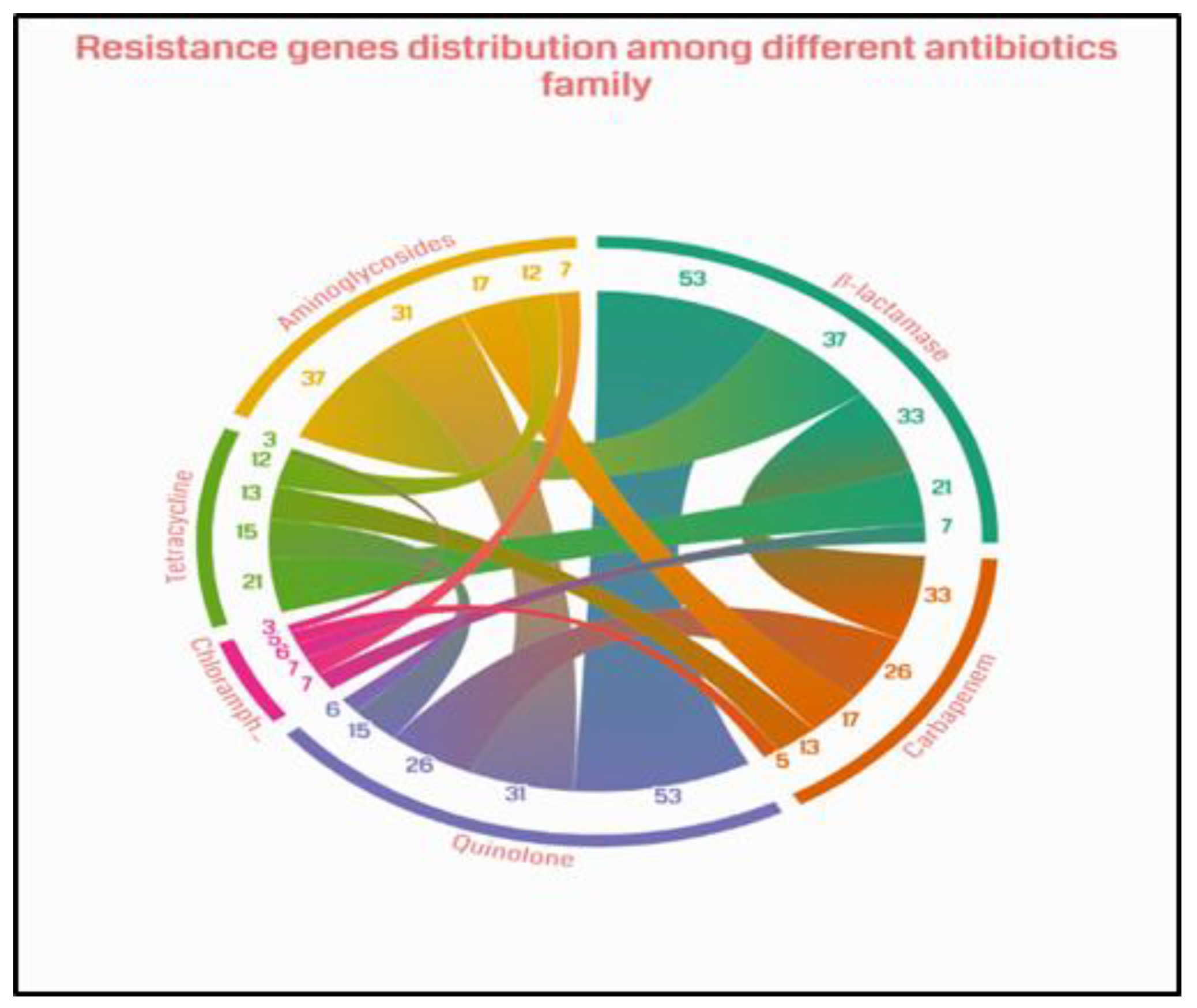

A total of 93 out of 98 E. coli isolates (94.9%) carried at least one antibiotic resistance gene, and 50% (49/98) were identified as multidrug-resistant (MDR).

Beta-lactam resistance genes were detected in 77.6% (76/98) of isolates, with

blaT

EM being the most frequently identified gene. Regarding the overall prevalence of resistance genes,

qnrS1 was the most common (66.3%), followed by

blaTEM (49%),

aphA3 (45.9%),

blaCTX-M (35.7%),

blaIMP (23.5%),

tetA (22.5%),

blaNDM (16.3%), and

catA1 (10.2%). Carbapenem resistance genes were detected in 38.8% of isolates (

Table 2).

Multidrug resistance associated with the blaNDM resistance gene was observed in 4 isolates, of which 3 also carried an integron gene. Additionally, 11 isolates harbored the blaTEM-blaCTX-M-qnrS1 gene combination, and 8 of them also carried an integron gene. Finally, 7 isolates carried the blaOxa- blaCTX-M-qnrS1 gene combination, all of which were positive for integron gene.

Table 2.

Distribution of resistance genes according antibiotic families among E. coli isolates.

Table 2.

Distribution of resistance genes according antibiotic families among E. coli isolates.

| Antibiotic families |

Gene |

Present

n (%) |

Absent

n (%) |

| |

Overall, N = 98 |

93 (94.9) |

5 (5.1) |

| Beta-lactams |

Overall |

76 (77.6) |

22 (22.4) |

| |

blaTEM

|

48 (49.0) |

50 (51.0) |

| |

blaCTX-M

|

35 (35.7) |

63 (64.3) |

| |

blaSHV

|

25 (25.5) |

73 (74.5) |

| |

blaOXA

|

16 (16.3) |

82 (83.7) |

| Carbapenems |

Overall |

38 (38.8) |

60 (61.2) |

| |

blaIMP

|

23 (23.5) |

75 (76.5) |

| |

blaNDM

|

16 (16.3) |

82 (83.7) |

| Quinolone |

qnrS1 |

65 (66.3) |

33 (33.7) |

| Chloramphenicol |

catA1 |

10 (10.2) |

88 (89.8) |

| Tetracycline |

tetA |

22 (22.5) |

76 (77.5) |

| Aminoglycoside |

aphA3 |

45 (45.9) |

53 (54.1) |

| Integron |

Overall |

37 (37.8) |

61 (62.2) |

| |

Int 1 |

35 (35.7) |

63 (64.3) |

| |

Int 2 |

25 (25.5) |

73 (74.5) |

| |

Int 3 |

31 (31.6) |

67 (68.4) |

Co-detection of resistance genes was observed between resistance genes across most classes of antibiotics investigated. However, the most frequent co-detections were observed between beta-lactams and quinolones (53 isolates), followed by beta-lactams and aminoglycosides (37 isolates), beta-lactams and carbapenems (33 isolates), aminoglycosides and quinolones (31 isolates), quinolones and carbapenems (26 isolates), and beta-lactams and tetracyclines (21 isolates) (

Figure 3). These co-detections contribute to the high risk of multidrug resistance, significantly reducing therapeutic options.

Integron Distribution and Resistance Genes

Integron genes were detected among the

E. coli isolates as follows:

Int1 (35.7%, 35/98),

Int3 (31.6%, 31/98), and

Int2 (25.5%, 25/98) (

Table 3). A statistically significant association was observed between class 2 integrons and isolates harboring more than three resistance genes (p = 0.011), suggesting a strong link between class 2 integrons and multidrug resistance. Although class 1 and class 3 integrons were also found among isolates with more than three resistance genes (60% and 61.3%, respectively), their associations were not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (

Table 3).

Analysis of blaNDM sequencing results

Sequencing of the PCR-amplified

blaNDM product showed high similarity to

blaNDM-5. The encoded protein was characterized by several amino acid substitutions, including Val→Leu at position 88 and Met→Leu at position 154. It differed from previously described enzymes by additional substitutions at positions 132 (Leu→Met) and 166 (Asp→Hist), which may alter the structure or function of the protein (

Table 4). These novel mutations could contribute to reduced susceptibility of

E. coli strains to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins and carbapenems.

- ⮚

Phylogenetic Diversity of NDM-Producing Escherichia coli Strains Including a Malian Isolate

The single sequence from this study is closely related to the sequence from China.

Figure 4.

Phylogeny of blaNDM sequence from this study.

Figure 4.

Phylogeny of blaNDM sequence from this study.

Maximum-likelihood phylogeny of blaNDM sequence from this study reconstructed with MEGA version 7.0.26. Phylogeny was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Tamura-Nei model, and branch support was evaluated with bootstrap approximation using 1,000 replicates. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together is shown next to the branches. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the Maximum Composite Likelihood (MCL) approach, and then selecting the topology with superior log likelihood value. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. We used six sequences from BLAST in GenBank, along with the single sequence from this study. The sequences from this study is shown in red.

Discussion

Enteropathogenic

E. coli (EPEC) strains play a central role in the occurrence of diarrhea, especially in children [

18,

19]. In this study, 85.7% of the isolates were identified as EPEC, representing a higher prevalence than that reported in other African countries: 61.1% in Niger, 55.9% in Ethiopia [

20,

21], and 45% in Burkina Faso [

22]. Conversely, lower rates have been observed in Colombia (17.9%) [

18], Kenya (22.46%) [

19], and India (17.4%) [

23]. Such variability may be attributed to differences in the target population, sanitation conditions, and detection methods.

In this study, EPEC strains were the most frequently detected, followed by EAEC and ETEC. This trend is consistent with findings from Kenya [

19], South Korea [

21], and India [

23], although the latter did not report any ETEC strains. Other studies, however, have reported the opposite pattern, with a predominance of EAEC followed by EPEC [

24,

25,

26]. Although the overall prevalence of EPEC is generally low, these strains are highly contagious in children and can lead to more severe forms of diarrhea [

27]. We did not differentiate between typical and atypical EPEC strains, but previous research suggests that typical EPEC strains are more commonly associated with diarrheal illness in developing countries [

28].

Additionally, 50% of DEC strains in this study exhibited mixed infections involving two or three virulence genes. These combinations may enhance the pathogenic potential of the strains and exacerbate the severity of infection [

29,

30]. Similar associations have been reported in sub-Saharan Africa, although at lower frequencies [

20,

22,

26]. Regarding antibiotic resistance, 50% of the DEC strains in this study were multidrug-resistant (MDR), defined as the presence of at least one resistance gene in three different antibiotic classes. By comparison, MDR rate were 63.2% in Ethiopia [

21], 95.3% in Nigeria [

31], and 42.07% in Iran [

32]. In Mali, a study also reported high levels of beta-lactam resistance, with 13 different variants identified [

7].

The most frequently detected resistance genes in this study were

blaTEM (49%),

blaCTX-M (35.7%), and

blaSHV (25.5%). These results align with those obtained by Guindo et al. in Bamako [

33] and are consistent with findings from other studies. For instance, in Iran, the prevalence of these genes was 93.2% for

blaTEM, 20.5% for

blaCTX-M, and 2.3% for

blaSHV [

34]. Co-detection of resistance genes across multiple antibiotic classes was also observed, particularly between beta-lactams and quinolones, and between beta-lactams and aminoglycosides. A similar, though less frequent, association was reported in Iran (11.4%) [

34]. The coexistence of ESBL genes and fluoroquinolone resistance has also been documented in other studies [

35]. We also found isolates carrying both the

blaNDM gene and integron genes.

The high prevalence of multidrug resistant (MDR)

E. coli observed in this study may be attributed to the strong selection pressure exerted by excessive and inappropriate antibiotic use in Mali. Historical data support this hypothesis; for instance, a 2002 study conducted in community health centers (CSCOM) reported an antibiotic prescription rate of 61.6%, with a substantial proportion classified as inappropriate [

36]. Such prescribing practices not only promote resistance but also reduce the effectiveness of commonly used treatment over time. Beta-lactams remain the most frequently prescribed class, followed by aminoglycosides [

37]. This pattern of antibiotic use in concerning, as it may contribute to the continued selection of resistant strains, particularly in environments with limited diagnostic capacity and antimicrobial stewardship programs.

We also observed a high prevalence of class 1 integrons, followed by class 3 and class 2 integrons. These genetic elements facilitate the acquisition and dissemination of resistance genes. A similar integron distribution profile was reported by Guindo et al. in Mali [

7]. In contrast, a study conducted in Iran found that class 2 integrons (76.8%) were more strongly associated with multidrug resistance [

32]. In our study, class 2 integrons were significantly associated with the presence of more than three resistance genes. For class 1 and class 3 integrons, associations were observed but did not reach statistical significance. This contrasts with the findings of Singh et al., who reported a significant association only for class 1 integrons [

38].

Finally, the detection of the

blaNDM gene, which encodes carbapenemase production, underscores the emergence of highly resistant strains. To our knowledge, this is the first report of NDM β-lactamase gene with mutations in Mali, highlighting its spread within hospital settings in Bamako. These findings emphasize the urgent need for enhanced surveillance and molecular studies to mitigate the clinical impact of this emerging resistance threat. This gene was first identified in 2008 [

39], and the sequence obtained in our study reveals two characteristic mutations at positions 88 (Val→Leu) and 154 (Met→Leu) [

40]. The presence of

NDM-5 in clinical isolates constitutes a major public health concern, given the limited therapeutic options available for treating infections caused by such strains.

One limitation of this study is the low number of sequenced samples due to the limited resources and its retrospective design. However, a key strength is the large number of resistance genes investigated using a molecular approach. Finally, additional studies using high-throughput sequencing (NGS) are needed to better characterize the genetic diversity of E. coli strains and to deepen our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying their resistance.

Conclusions

This study highlights the prevalence of diarrheagenic E. coli (DEC) strains, associated with the widespread distribution of antibiotic resistance genes. These findings illustrate the significant threat that multidrug-resistant DEC strains pose to public health.

References

- Murray, C.J.L., et al. (2022). Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet, 399(10325), 629-655. [CrossRef]

- Fair, R.J., & Tor, Y. (2014). Antibiotics and Bacterial Resistance in the 21st Century. SAGE Open. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2024). Antimicrobial resistance.

- Marston, H.D., et al. (2016). Antimicrobial Resistance. JAMA, 316(11), 1193.

- Nataro, J.P., & Kaper, J.B. (1998). Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 11(1), 142-201.

- World Health Organization. (2017). WHO names 12 bacteria that pose the greatest threat to human health. The Guardian.

- Guindo, I., et al. (2022). Pathogenicity Factors and Antibiotic Resistance of Escherichia coli Strains Isolated from Diarrheic Children Aged 0–59 Months in Community Settings in Bamako.

- Diarra, B., et al. (2024). High frequency of antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella and Escherichia coli causing diarrheal diseases at the Yirimadio community health facility, Mali. BMC Microbiology, 24(1), 35. [CrossRef]

- Poirel, L., et al. (2018). Antimicrobial Resistance in Escherichia coli. Microbiology Spectrum, 6(4), 6.4.14.

- Rodrigo, L. (2020). E. Coli Infections: Importance of Early Diagnosis and Efficient Treatment. BoD – Books on Demand, 236.

- World Health Organization. (2019). Exploring the antimicrobial resistance profiles of WHO critical priority list bacterial strains. BMC Microbiology.

- Vilchez, S., et al., Prevalence of diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli in children from León, Nicaragua. Journal of Medical Microbiology, 2009. 58(Pt 5): p. 630-637.

- Weill, F.X., et al., Multidrug resistance in Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium from humans in France (1993 to 2003). Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 2006. 44(3): p. 700-708. [CrossRef]

- Letchumanan, V., et al., Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from retail shrimps in Malaysia. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2015. 6: p. 33-33. [CrossRef]

- Pagani, L., et al., Multiple CTX-M-type extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in nosocomial isolates of Enterobacteriaceae from a hospital in northern Italy. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 2003. 41(9): p. 4264-4269. [CrossRef]

- Awoke T, T.B., Aseffa A, Sebre S, Seman A, Yeshitela B, Abebe T, Mihret A. , Detection of blaKPC and blaNDM carbapenemase genes among Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Dominance of blaNDM. PLoS One. 2022 Apr 27;17(4):e0267657. [CrossRef]

- Ploy, M.C., et al., Molecular characterization of integrons in Acinetobacter baumannii: description of a hybrid class 2 integron. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2000. 44(10): p. 2684. [CrossRef]

- Rúgeles, L.C., et al. (2010). Molecular characterization of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli strains from stools samples and food products in Colombia. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 138(3), 282-286. [CrossRef]

- Okumu, N.O., et al. (2023). Risk factors for diarrheagenic Escherichia coli infection in children aged 6–24 months in peri-urban community, Nairobi, Kenya. PLOS Global Public Health, 3(11), e0002594. [CrossRef]

- Abdoulaye, O., et al. (2020). Prevalence of Virulence Genes of Escherichia Coli During Acute Gastroenteritis in Children in Niamey. HEALTH SCIENCES AND DISEASE, 21(7).

- Wolde, A., et al. (n.d.). Molecular Characterization and Antimicrobial Resistance of Pathogenic Escherichia coli Strains in Children from Wolaita Sodo, Southern Ethiopia. Journal of Tropical Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Clinical Microbiology and Infection. (2012). Diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli detected by 16-plex PCR in children with and without diarrhoea in Burkina Faso.

- Shetty, V.A., et al. (2012). Prevalence and Characterization of Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli Isolated from Adults and Children in Mangalore, India. Journal of Laboratory Physicians, 4(1), 24-29. [CrossRef]

- Hegde, A., Ballal, M., & Shenoy, S. (2012). Detection of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli by multiplex PCR. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology, 30(3), 279-284. [CrossRef]

- Konaté, A., et al. (2017). Molecular characterization of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in children less than 5 years of age with diarrhea in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. EuJMI, 7(3), 220-228. [CrossRef]

- Moyo, S.J., et al. (2007). Identification of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli isolated from infants and children in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Infectious Diseases, 7(1), 92. [CrossRef]

- Gambushe, S.M., Zishiri, O.T., & El Zowalaty, M.E. (2022). Review of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Prevalence, Pathogenicity, Heavy Metal and Antimicrobial Resistance, African Perspective. Infection and Drug Resistance, 15, 4645-4673. [CrossRef]

- Trabulsi, L.R., Keller, R., & Gomes, T.A.T. (2002). Typical and Atypical Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 8(5). [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.C.d.M., et al. (2020). Diversity of Hybrid- and Hetero-Pathogenic Escherichia coli and Their Potential Implication in More Severe Diseases. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 10, 339.

- Nature Reviews Microbiology. (2004). Pathogenic Escherichia coli.

- Medugu, N., et al. (2022). Molecular characterization of multi drug resistant Escherichia coli isolates at a tertiary hospital in Abuja, Nigeria. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 14822. [CrossRef]

- Kargar, M., et al. (2014). High Prevalence of Class 1 to 3 Integrons Among Multidrug-Resistant Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in Southwest of Iran. Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives, 5(4), 193-198. [CrossRef]

- CHU du Point G. (2008). Prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing enterobacteria from 2006 to 2008.

- Egwu, E., et al. (2023). Antimicrobial susceptibility and molecular characteristics of beta-lactam and fluoroquinolone resistant E. coli from human clinical samples in Nigeria. Scientific African, 21, e01863. [CrossRef]

- Rupp, M.E., & Fey, P.D. (2003). Extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae: considerations for diagnosis, prevention and drug treatment. Drugs, 63(4), 353-365.

- Diawara, A., et al. (2007). Prescription practices in community health centers (CSCOM) and medicine usage by populations.

- Coulibaly, Y., et al. (2014). Study of antibiotic prescription in Malian hospitals. Revue Malienne d’Infectiologie et de Microbiologie, 2-8.

- Singh, T., et al. (2021). Integron mediated antimicrobial resistance in diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in children: in vitro and in silico analysis. Microbial Pathogenesis, 150, 104680. [CrossRef]

- Yong, D., et al. (2009). Characterization of a new metallo-beta-lactamase gene, bla(NDM-1), and a novel erythromycin esterase gene carried on a unique genetic structure in Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 14 from India. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 53(12), 5046-5054. [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, M., Phee, L., & Wareham, D.W. (2011). A novel variant, NDM-5, of the New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase in a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli ST648 isolate recovered from a patient in the United Kingdom. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 55(12), 5952-5954. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).