1. Introduction

Lignans are a group of plant-derived phenolic compounds synthesized via the phenylpropanoid pathway. These secondary metabolites have gained attention for their diverse bioactivities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and estrogenic effects, as well as their potential roles in cancer prevention and cardiovascular health [

1,

2,

3]. In plants, lignans serve important physiological functions such as antimicrobial defense, structural support, and oxidative stress protection [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Their biosynthetic pathway typically involves the stereospecific coupling of monolignols to form pinoresinol, followed by sequential reduction to lariciresinol and secoisolariciresinol. These steps are catalyzed by pinoresinol–lariciresinol reductase (PLR), an NAD(P)H-dependent oxidoreductase that determines both the quantity and type of lignans produced in plant tissues [

8].

The molecular and enzymatic mechanisms underlying lignan biosynthesis have been well characterized in several dicot species such as flax (

Linum usitatissimum) [

9,

10], sesame (

Sesamum indicum) [

11], and

Forsythia spp [

12]. However, in monocot crops such as rice (

Oryza sativa L.), research on lignan biosynthesis remains limited. Although earlier studies have detected trace amounts of lignans in rice hulls and bran [

13], the genes and regulatory networks involved in their production within rice grains remain largely unexplored, especially in specialty or landrace varieties.

Black rice varieties are known for their high antioxidant activity due to their rich content of polyphenols, anthocyanins, and flavonoids [

14,

15,

16]. Mae Phaya Thong Dam, a Thai aromatic black rice landrace, is particularly notable for its distinctive fragrance, deep pigmentation, and nutritional value. In a preliminary investigation conducted as part of this study, we detected lignan compounds in developing seeds of Mae Phaya Thong Dam rice using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The levels of these compounds increased progressively from the milky to mature grain stages, suggesting that lignan biosynthesis is developmentally regulated in this landrace. These findings prompted further investigation into the underlying molecular mechanisms, particularly the possible involvement of

PLR homologs.

Alternative splicing has emerged as a key regulatory mechanism in plant gene expression, generating multiple transcript isoforms from a single gene and enabling functional diversification [

17]. In genes associated with specialized metabolism, such as PLRs, splicing variants may differ in enzyme activity, subcellular localization, and/or developmental regulation [

18,

19]. Understanding the transcript diversity and expression dynamics of PLR genes could thus provide important insights into lignan production in cereals.

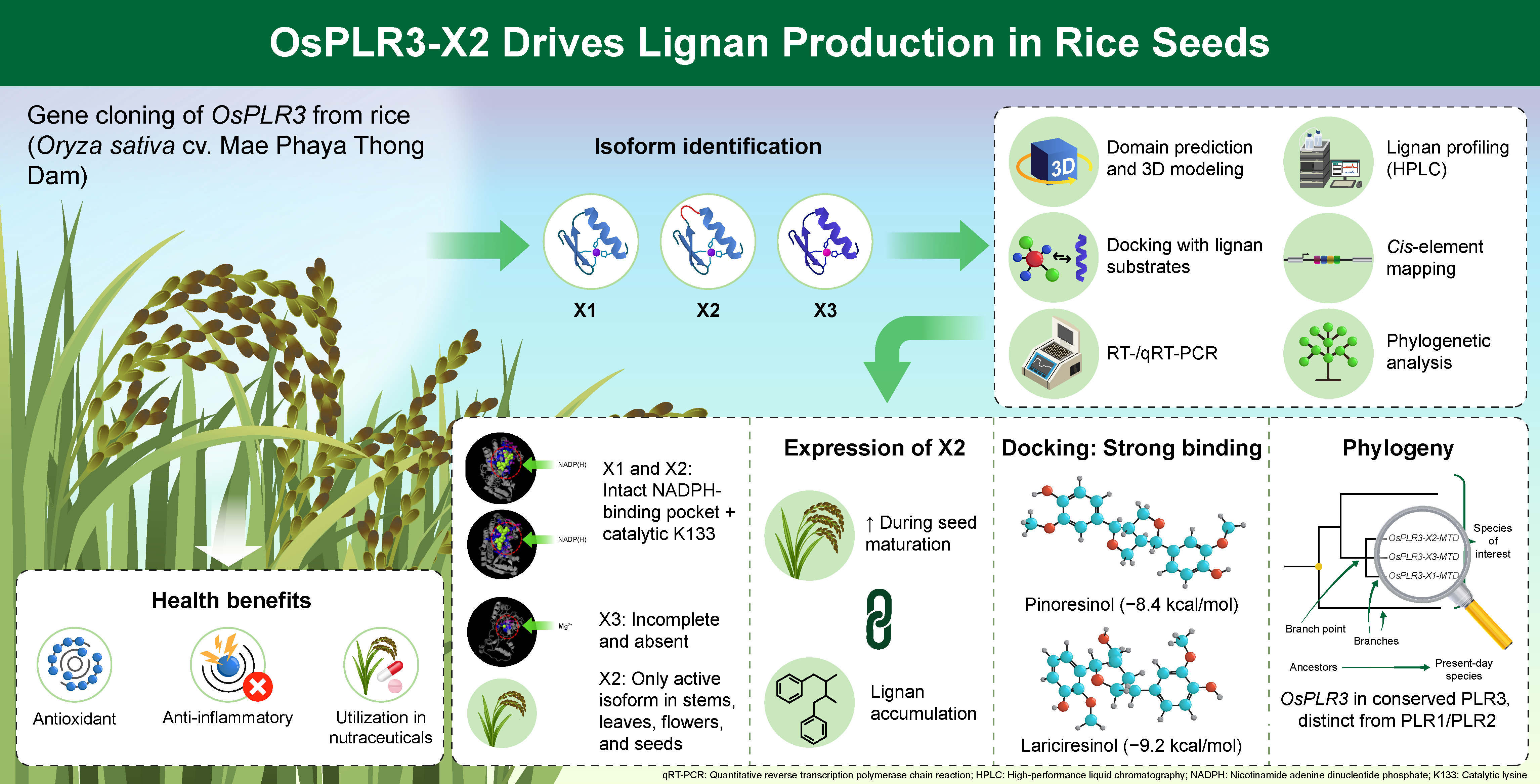

Here, we characterize OsPLR3, a putative PLR homolog from Mae Phaya Thong Dam rice, and identify three transcript isoforms (OsPLR3-X1, OsPLR3-X2, and OsPLR3-X3). Isoform OsPLR3-X2 exhibited distinct spatial and developmental expression patterns, with strong induction during seed maturation paralleling lignan accumulation, as confirmed by HPLC analysis. Functional relevance was demonstrated via 3D protein modeling and molecular docking, which revealed a conserved Rossmann-fold domain and strong ligand binding, consistent with PLR activity. Additionally, analysis of intronic cis-regulatory elements uncovered multiple hormone- and stress-responsive motifs, suggesting transcriptional modulation of OsPLR3 under developmental and environmental cues. Together, these findings highlight OsPLR3-X2 as a catalytically active isoform involved in lignan biosynthesis and underscore the potential of Mae Phaya Thong Dam rice as a genetic resource for functional food applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Sample Preparation

Seeds of the Thai black rice cultivar Oryza sativa L. cv. Mae Phaya Thong Dam were surface-sterilized and germinated on moist tissue paper under controlled conditions for 3 days. Uniform seedlings were subsequently transplanted into 15-inch plastic pots containing water-saturated soil. Each pot accommodated three seedlings. The experimental layout comprised three biological replicates, with each replicate consisting of five pots arranged in a row. Plant tissues were collected at six distinct developmental stages. These included the seedling stage (10 days after sowing), the tillering stage (60 days), and the flowering stage (approximately 90 days). In addition, developing grains were harvested at three reproductive stages: milky (8 days after fertilization), soft dough (14 days), and mature seed (30 days). For each sampling point, plant materials from all pots within the same biological replicate were pooled and treated as a single composite sample. Each sample was subsequently divided into two portions. The first portion was used for lignan profiling via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), allowing for both the identification and quantification of lignan compounds. The second portion was immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for total RNA extraction.

2.2. Cloning of the OsPLR3 Gene via PCR

To isolate the

PLR homolog

OsPLR3 in rice, the amino acid sequence of flax LuPLR1 (accession no. P0DKC8) was retrieved from the GenBank database and used as a query in a TBLASTN search against the Rice Genome Annotation Project database (

http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/; accessed on 21 March, 2021). Candidate nucleotide sequences showing homology to LuPLR1 were identified, and gene-specific primers were designed based on the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of the target gene. Primer sequences were evaluated using the Oligo Analysis Tool (Eurofins Genomics), and those used for PCR amplification are listed in

Supplementary Table S1.

PCR amplification was performed in a 20 µL reaction containing 2 µL of genomic DNA (20 ng/µL), 2.0 µL of 10X Thermo-Pol® Buffer, 2.0 µL of 20 mM MgCl2, 2.0 µL of 2 mM dNTP mix, 2.0 µL of each primer (5 µM), 0.1 µL of Taq DNA polymerase (5 U/µL; New England Biolabs® (Ipswich, MA, USA), and 7.9 µL of nuclease-free water to reach the final volume. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95° C for 30 s and annealing/extension at 65 °C for 3 min, with a final extension at 68 °C for 7 min. PCR products were analyzed via 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis. Amplified DNA fragments were purified using the GenepHlow™ PCR Cleanup Kit (Geneaid, New Taipei City, Taiwan), then ligated into the pGEM®-T Easy Vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The ligation was performed at an insert:vector molar ratio of 3:1, as recommended by the manufacturer, and the recombinant plasmids were subsequently transformed into Escherichia coli strain DH5α using the heat-shock method. Positive transformants were selected on LB agar plates containing ampicillin (100 µg/mL), X-gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-D-galactopyranoside), and IPTG (Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside), and white colonies were screened by colony PCR. Plasmids were extracted from confirmed colonies using the GenepHlow™ Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Geneaid, New Taipei City, Taiwan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and submitted for nucleotide sequencing at Macrogen (Seoul, Korea).

2.3. Bioinformatic Analysis

The identities of the cloned nucleotide sequences were confirmed by BLASTN analysis against the GenBank database (NCBI).Structural analysis was then performed using the Splign tool [

20] (accessed on 4 April, 2022) to determine exon–intron boundaries (splicing sites), using the cloned genomic DNA as the query and transcript sequences of

PLR homologs from

Oryza sativa japonica available in GenBank (accession numbers XM_026022838.2, XM_015769648.3, and XM_026022839.2) as references. The exon–intron junctions were further validated based on the canonical GT–AG rule.

The exon regions of each transcript variant were assembled, and the coding regions (open reading frames, ORFs) were identified and translated into amino acid sequences using the Expasy Translate tool [

21], accessed on 4 April, 2022. The deduced protein was functionally annotated using the Conserved Domain Search Service (CD-Search) [

22], accessed on 4 June, 2024, to predict conserved domains and active site residues.

To examine the conserved motifs and evolutionary relationships of PLR proteins, multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis were conducted using MEGA version 11 software [

23]. Multiple sequence alignment was conducted with ClustalW, and the phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Minimum Evolution (ME) method with 1000 bootstrap replicates to assess branch reliability.

The 3D protein structures were predicted using the I-TASSER server (version 5.1 accessed on 13 May 2025) [

24], and interaction with the NADP(H) cofactor was assessed. Molecular docking with pinoresinol and lariciresinol was performed using CB-Dock 2 web server (accessed July 26, 2025) which automatically identified potential binding cavities and calculated binding affinities based on Vina scores [

25]. Ligand structures were obtained from the PubChem database and prepared in MOL2 format [

26].

In addition, putative cis-regulatory elements within intronic regions of the

OsPLR3 gene were identified by submitting each intron sequence (FASTA format) to the PlantCARE ‘Search for CARE’ tool with default settings, and recording the element name, position (bp), strand, and functional category (accessed 13 July 2025) [

27] Docking was performed with the CB-Dock2 web server (accessed 7 September 2025), which uses AutoDock Vina v1.2.0 and the BioLip2 template database (release 2025-04-23).

2.4. Total RNA Extraction

Total RNA was extracted from leaf and stem tissues of rice plants 10 and 60 days after sowing, as well as from rice floral buds, and seeds in the milky, dough, and mature stages. The extraction was performed using the Trizol® reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and quantity of RNA were assessed via 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis to verify RNA integrity, and by spectrophotometric analysis at wavelengths of 260 and 280 nm, with an A260/A280 ratio of ~1.8–2.0 recommended as acceptable for subsequent cDNA synthesis. First-strand cDNA synthesis was carried out using the SuperScript™ III First-Strand Synthesis System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with oligo(dT) primers, following the manufacturer’s protocol. The reactions were initiated with equal amounts of total RNA for all samples, and the consistency of cDNA synthesis was confirmed by PCR amplification of the Actin 1 gene as an internal control.

2.5. Gene Expression Analysis via RT-PCR

Gene expression was analyzed using reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR). The reaction mixture (20 µL total volume) contained 2 µL of cDNA template, 2 µL of 2 mM dNTP mix (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP), 2 µL each of 5 µM gene-specific forward and reverse primers, 0.1 µL of Taq DNA polymerase (0.5 U/µL; New England Biolabs, USA), and 11.9 µL of nuclease-free water to adjust to the final volume. PCR amplification was performed using an MJ Mini Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) under the following cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s; 34 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 56 °C for 20 s, and extension at 68 °C for 20 s; and a final extension at 68 °C for 5 min. Amplified products were separated on a 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide (1 µg/mL) and visualized using a Gel Documentation System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

2.6. Quantitative Analysis of Gene Expression via Real-Time RT-PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was conducted to determine the expression levels of target genes in rice seeds in the milky, waxy, and mature stages. The reactions were performed using the iTaq™ Universal SYBR

® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, USA) in a 15 µL total volume, containing 1 µL of cDNA template, 7.5 µL of 2× SYBR

® Green Reaction Mix, 0.3 µL each of 5 µM forward and reverse primers, and 5.9 µL of nuclease-free water to complete the reaction volume. Amplification was carried out using a CFX96™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, USA) under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of annealing/extension at 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 30 s. Melting curve analysis was performed from 65 °C to 95 °C, with a 0.5 °C increment per step, to verify amplification specificity. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2

^–ΔΔCT method [

28], with

Actin I (KC140126.1) used as the internal reference gene for normalization. Primer sequences for all target genes used in the qRT-PCR analysis are listed in

Supplementary Table S2.

2.7. Lignan Extraction from Rice Grains

Lignan compounds were extracted from rice grains at different developmental stages using acid hydrolysis under heat, following a modified protocol based on Hutabarat et al. (2000) [

29]. Briefly, rice grains were ground into a fine and homogeneous powder using a benchtop herbal grinder. Subsequently, 1 g of the powder was mixed with 10 mL of 2 M hydrochloric acid and 40 mL of 96% ethanol. The mixture was incubated at 100 °C for 6 h. Following hydrolysis, the solution was filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper and allowed it to cool to room temperature. The final volume was adjusted to 50 mL with 96% ethanol. Each sample was extracted in triplicate. The resulting extracts were used for subsequent lignan quantification and profiling via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

2.8. Lignan Analysis via High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

The identification and quantification of lignan compounds were performed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), modified from the method described by Kuhnle et al. (2007) [

30]. Three lignan standards—secoisolariciresinol, matairesinol, and coumestrol—were used for calibration. Standard solutions were prepared in methanol at various concentrations and filtered through a 0.45 µm syringe filter prior to injection. The chromatographic analysis was conducted at the Laboratory of Chemistry, Faculty of Liberal Arts and Science, Kasetsart University, Kamphaeng Saen Campus, Thailand, using a reverse-phase C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm, ACE, UK). The mobile phase consisted of 0.025% acetic acid in water and acetonitrile (33:67, v/v), and the injection volume was 10 µL, with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min for 30 min. Detection was carried out using a UV detector (Chromaster 5410, Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at 260 nm. Quantification of lignan content was based on peak areas relative to calibration curves of standards. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 17.0). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied, and differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Cloning and Structural Characterization of the OsPLR3 Gene

The

OsPLR3 gene was cloned from

Oryza sativa L. cv. Mae Phaya Thong Dam using PCR amplification with gene-specific primers, yielding a 2,453 bp fragment. Sequence homology was analyzed using BlastN against the GenBank database with the “Reference RNA sequences (RefSeq RNA)” and “highly similar sequences (megablast)” parameters. The cloned fragment exhibited high sequence similarity to

PLR3 homologs from

O. sativa ssp.

japonica (LOC4330458),

Triticum aestivum (LOC123145218, LOC123128126, LOC123137921),

Hordeum vulgare (LOC123401120),

Sorghum bicolor (LOC8073160), and

Zea mays (LOC100280127). Based on this similarity, the gene was designated

OsPLR3, and its nucleotide sequence was submitted to GenBank under accession number PX391232. Gene structure was analyzed using the Splign alignment tool [

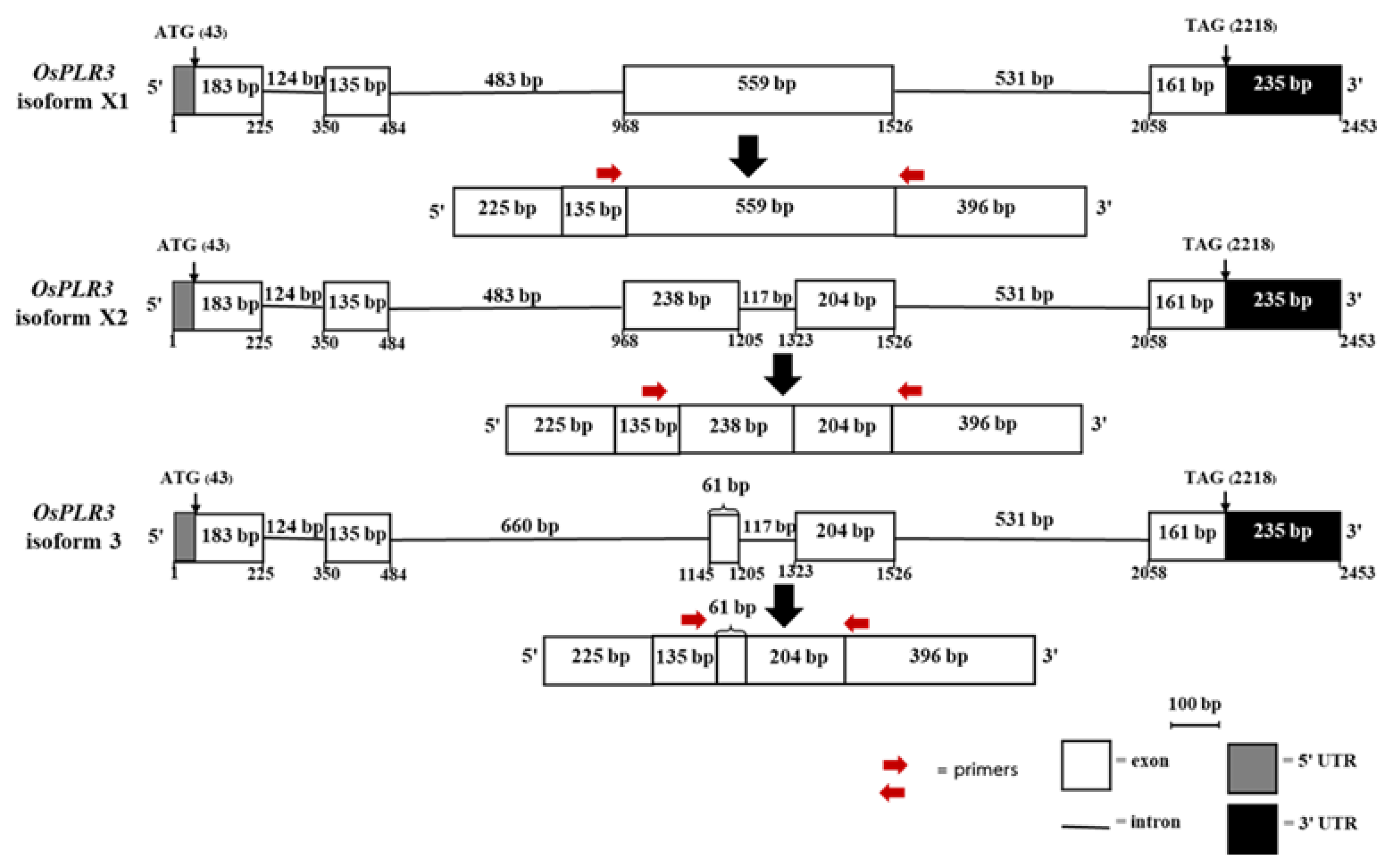

20] to determine exon–intron organization based on the genomic DNA sequence. Three alternatively spliced transcript isoforms were predicted (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2):

Isoform X1 consists of four exons (225, 135, 599, and 396 bp) and three introns (127, 483, and 531 bp), producing a 1,315 bp mRNA with an open reading frame (ORF) of 1,038 bp encoding a 345-amino acid protein.

Isoform X2 comprises five exons (225, 135, 238, 204, and 396 bp), generating a 1,198 bp transcript with a 921 bp ORF encoding 306 amino acids.

Isoform X3 also includes five exons (225, 135, 61, 204, and 396 bp), resulting in a 1,201 bp transcript with a 744 bp ORF encoding a 247-amino acid protein.

These findings suggest that OsPLR3 undergoes alternative splicing, potentially giving rise to isoforms with distinct functional roles.

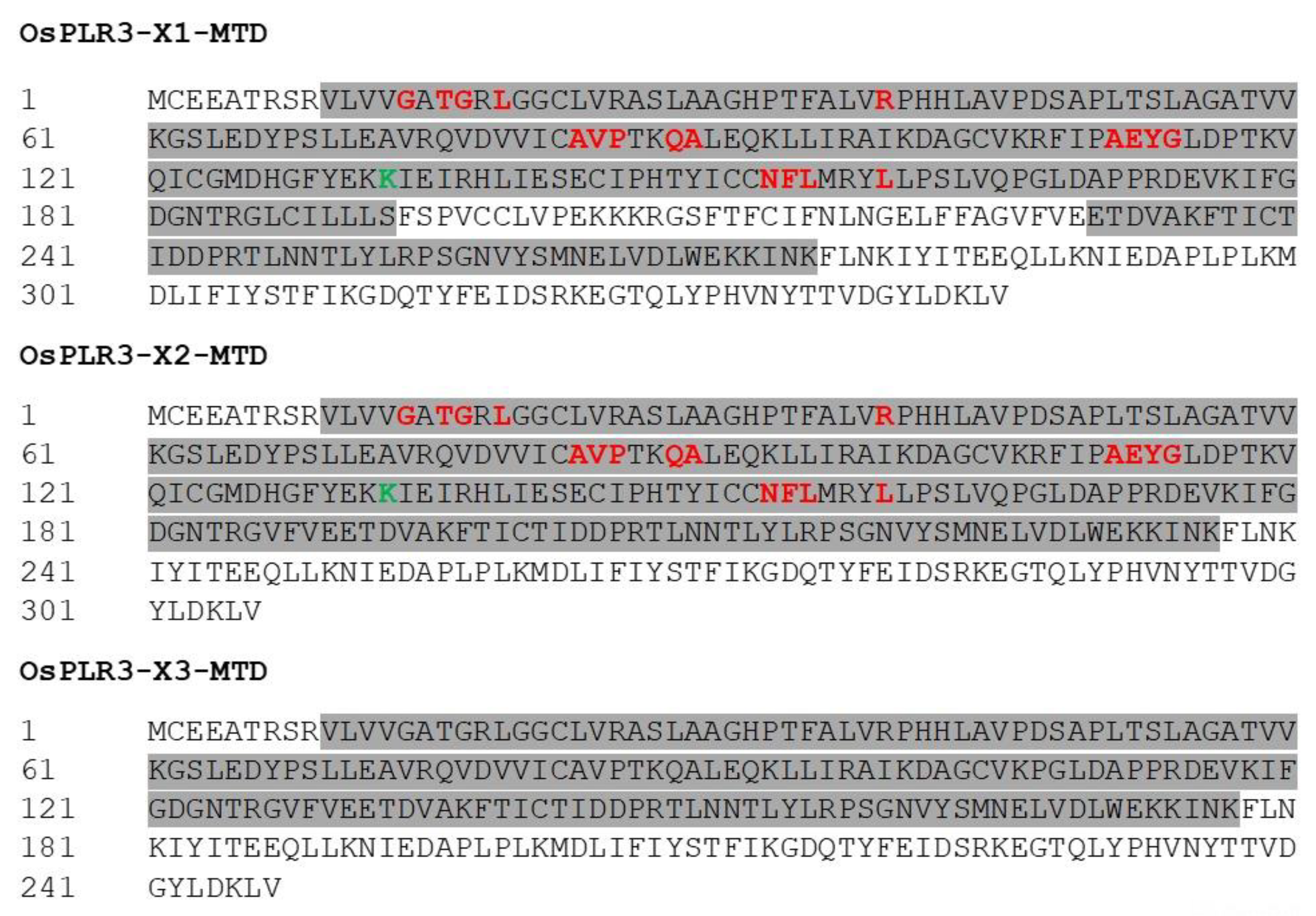

3.2. Conserved Domain and Motif Analysis of the OsPLR3 Isoforms

Conserved domain analysis of the three OsPLR3 isoforms, in comparison with LuPLR1 from

Linum usitatissimum (accession no. P0DKC8), revealed the presence of the Rossmann-fold NAD(P)(+) binding domain (NADB_Rossmann). This domain spanned amino acid positions 10–193 and 230-275 in isoform X1, 10–236 in isoform X2, and 10–117 in isoform X3, as shown in

Figure 2. Putative NAD(P)-binding residues were identified at positions 14, 16, 17, 19, 39, 83–85, 88–89, 111–114, 133, and 153–155, with the lysine at position 133 specifically conserved in isoforms X1 and X2. This lysine residue, known to be essential for dehydrogenation activity, was absent in isoform X3.

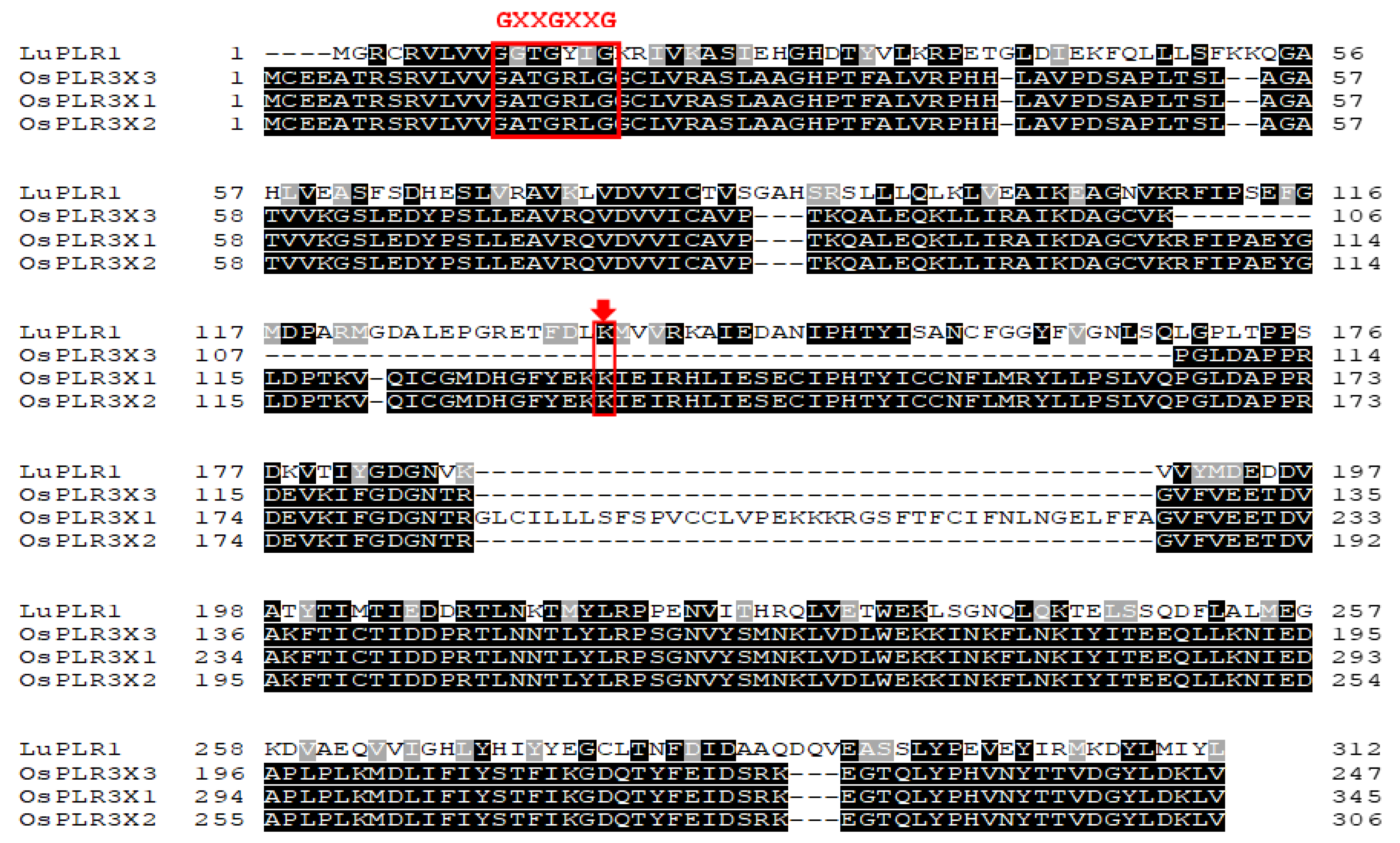

Multiple sequence alignment with LuPLR1 further identified a conserved N-terminal “GXXGXXG” motif characteristic of NADPH-dependent reductases, including PLR- and IFR-family enzymes [

31] (

Figure 3). The presence of both the NAD(P) binding domain and the catalytic lysine in isoforms X1 and X2 indicates their functional identity as PLR homologs. In contrast, the absence of this lysine residue in isoform X3 suggests that it may be catalytically inactive or possess altered enzymatic function.

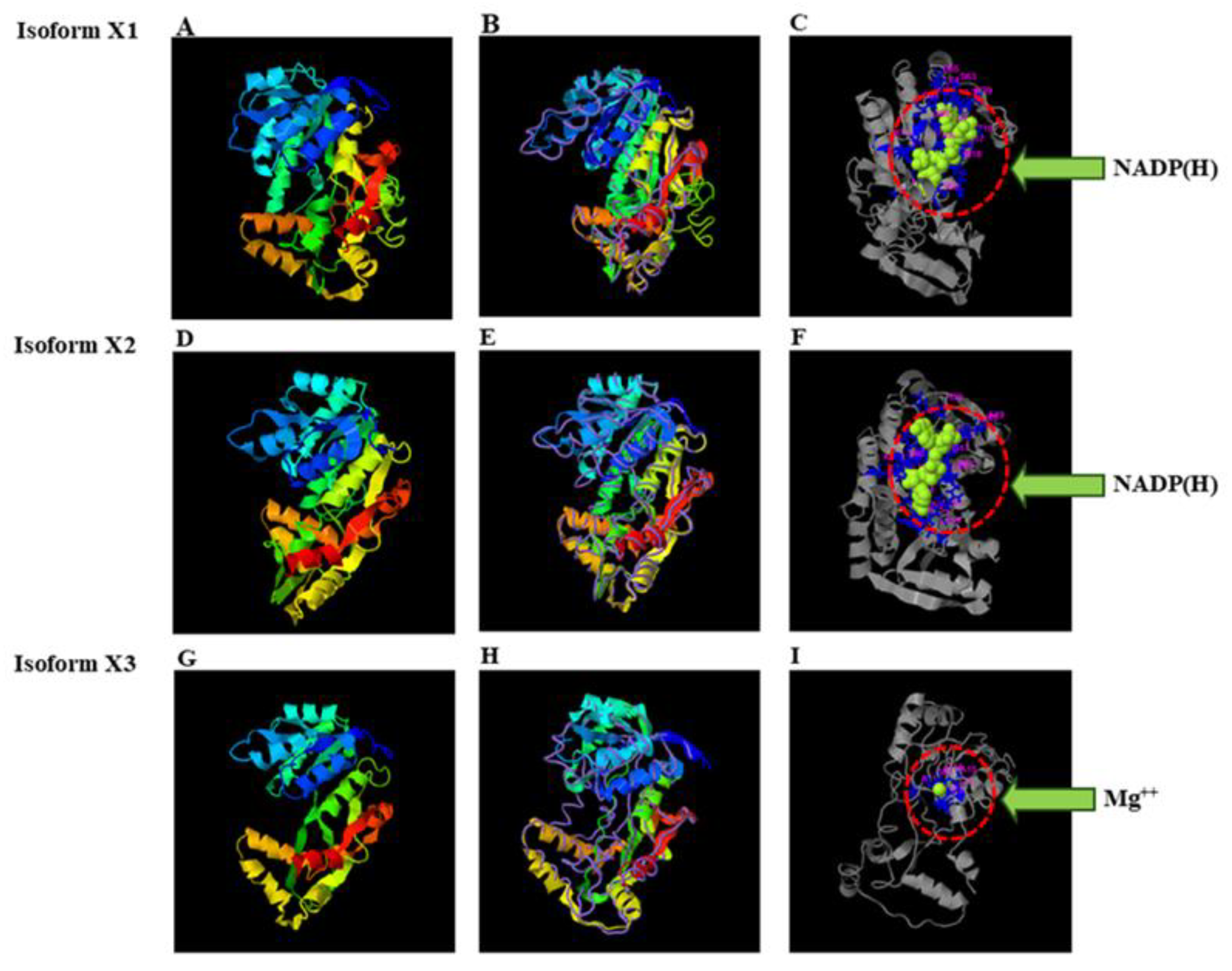

3.3. Structural Modeling and Molecular Docking Demonstrate the Enzymatic Function of the OsPLR3 Isoforms

To verify the catalytic function of OsPLR

3 in the dehydrogenation reaction, the 3D structures of all three isoforms were predicted using the I-TASSER server [

24]. The server automatically selected the most structurally homologous protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) as the modeling template, based on highest sequence identity and normalized Z-score provided by the threading algorithm. Isoform X

1′s structure was modeled using a

Pinus taeda PLR (PDB ID: 1qycA) as the template, resulting in a TM-score of 0.868 and an RMSD of 0.64 Å (

Figure 4A,B), indicating high structural similarity. Notably, isoform X1 also exhibited a well-defined NADP(H)-binding pocket (

Figure 4C), consistent with its proposed role as an NADPH-dependent reductase. Similarly, isoform X2 was modeled using a PLR (TpPLR1) from

Thuja plicata (PDB ID: 1qyc), yielding a TM-score of 0.972 and an RMSD of 0.82 Å (

Figure 4D,E), further supporting OsPLR

3′s classification as a PLR homolog. A comparable NADP(H)-binding pocket was observed in X2 (

Figure 4F), reinforcing the proposed dehydrogenase function of both isoforms X1 and X2. In contrast, isoform X3 was modeled using an isoflavone reductase (IFR) from

P. taeda (PDB ID: d1qyc), with a lower TM-score of 0.54 and a higher RMSD of 9.7 Å (

Figure 4 G,H), reflecting poor structural alignment. Furthermore, no NADP(H)-binding pocket was detected in isoform X3; instead, a magnesium ion (Mg

2+) was found at the predicted binding site (

Figure 4I). These results suggest that X3 may have diverged structurally and functionally from X1 and X2, lacking the catalytic machinery required for NADPH-dependent reduction, and it is therefore unlikely to participate in lignan biosynthesis.

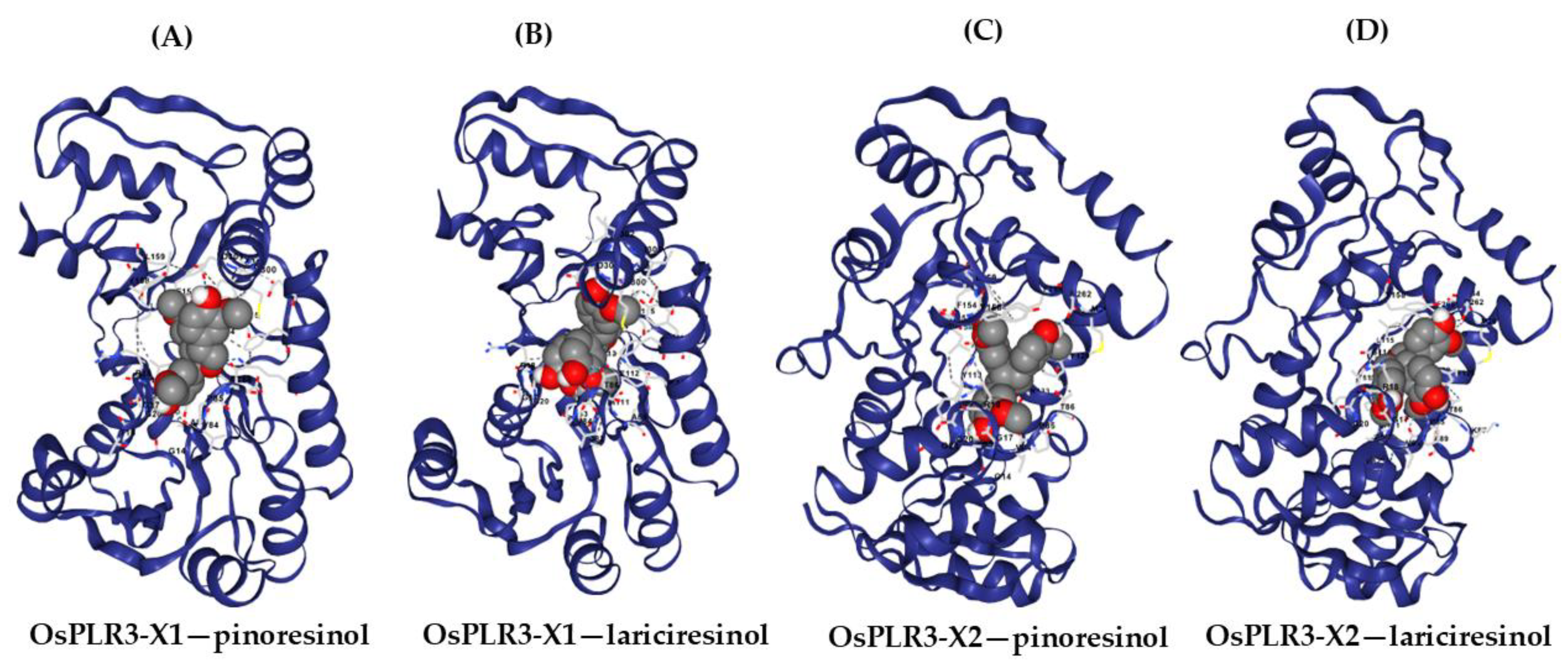

To evaluate the substrate-binding capabilities of the OsPLR3 isoforms, molecular docking was simulated using both pinoresinol and lariciresinol as ligands. The 3D structures of OsPLR3 isoforms X1 and X2 were modeled and subjected to blind docking analysis using the CB-Dock2 server. For each protein–ligand pair, five potential binding pockets (CurPocket IDs C1–C5) were predicted. Among them, CurPocket C2 consistently exhibited the most favorable binding characteristics across all conditions, including the lowest Vina scores and optimal pocket volumes (Supplementary

Tables S3–S6). In the case of OsPLR3 isoform X1, docking with pinoresinol produced a Vina score of –8.5 kcal/mol (

Table 1;

Figure 5A), while that with lariciresinol yielded the lowest overall binding energy of –9.6 kcal/mol among all the tested combinations (

Table 1;

Figure 5A and B). In molecular docking, the Vina score represents the predicted binding free energy (ΔG) in kcal/mol, with more negative values indicating stronger binding affinity between the ligand and the protein target. The ligands were accommodated within the same pocket (CurPocket C2), with a cavity volume of 934 Å

3, and formed interactions with conserved residues including GLU112, TYR113, ASN153, PHE154, LEU155, TYR158, and, notably, LYS133. These residues are located near the Rossmann-fold NADPH binding domain, with LYS133 proposed to play a critical role in substrate stabilization and possibly in the proton relay mechanism during catalysis. Similarly, OsPLR3 isoform X2 exhibited strong binding affinity toward both ligands. Docking with pinoresinol resulted in a Vina score of –8.4 kcal/mol (

Table 1;

Figure 5C and D), and that with lariciresinol produced a slightly stronger score of –9.2 kcal/mol (

Table 1;

Figure 5D). The identified binding pocket (CurPocket C2, cavity volume 1028 Å

3) involved highly conserved residues such as GLU112, TYR113, GLY114, LEU115, ASN153, PHE154, LEU155, and, again, LYS133, reinforcing its importance in ligand recognition.

Taken together, these findings indicate that both OsPLR3 isoforms possess a structurally conserved active site, centered on CurPocket C2, capable of accommodating both pinoresinol and lariciresinol with high affinity. The consistently strong binding energies and shared contact residues, particularly for LYS133, support the hypothesis that OsPLR3 can catalyze both reduction steps in the lignan biosynthesis pathway through a common substrate recognition mechanism.

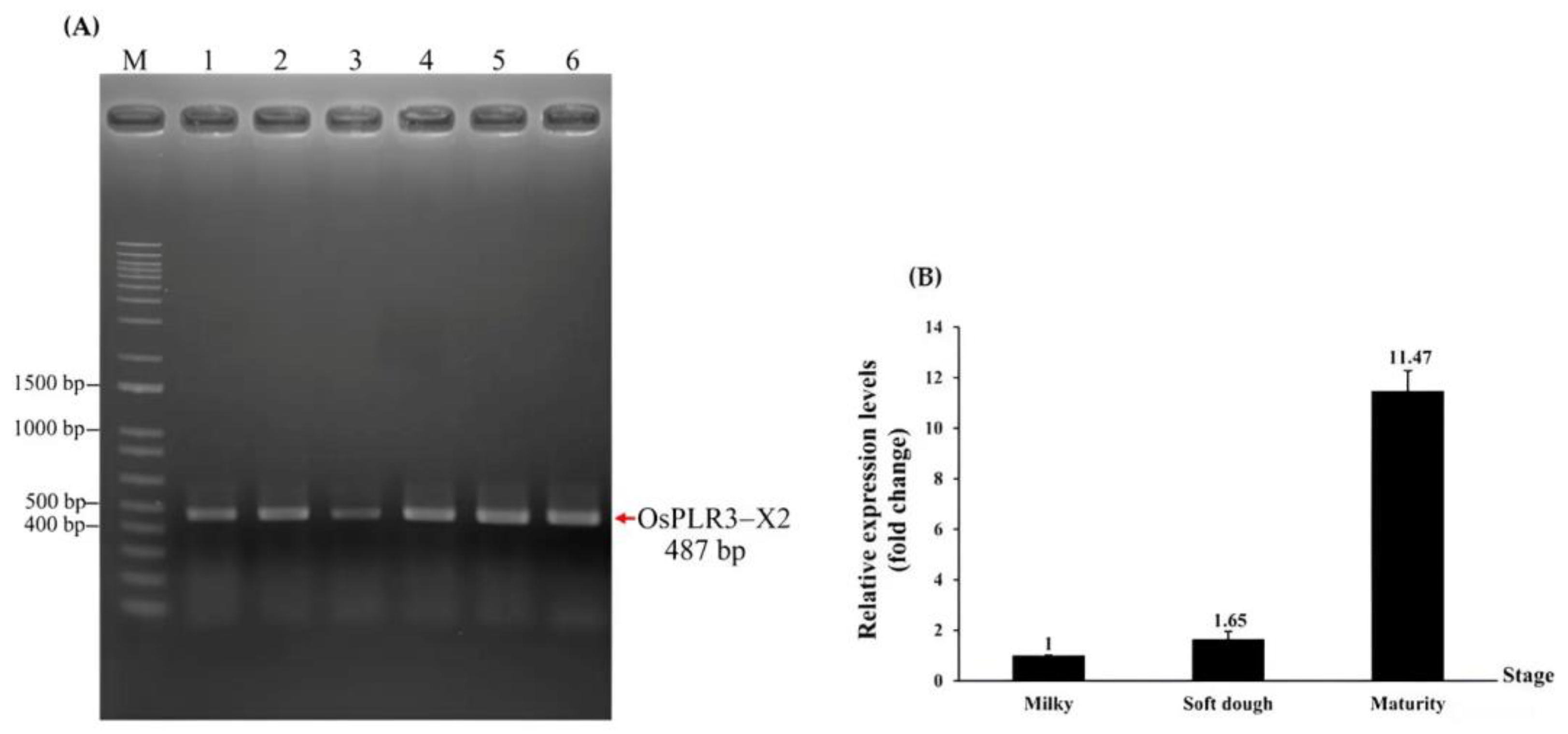

3.4. Gene Expression Analysis of OsPLR3

To investigate the expression patterns of individual

OsPLR3 isoforms, isoform-specific primers were designed based on the nucleotide sequences spanning exon 2 and the final exon (

Figure 1). These primers produced PCR amplicons of 584, 487, and 290 base pairs, corresponding to isoforms X1, X2, and X3, respectively (

Table 2). Using these primer pairs, RT-PCR was performed to examine

OsPLR3 expression in leaf and stem tissues of 10- and 60-day-old rice plants, as well as in flower and milk-stage seed tissues. The results revealed a PCR product of 487 base pairs in all examined tissues (

Figure 6A), indicating the expression of isoform X2. No PCR products corresponding to isoforms X1 or X3 were detected, indicating that isoform X2 is predominantly expressed and may contribute to lignan biosynthesis.

To further quantify

OsPLR3 isoform X

2′s expression during seed development, quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was conducted using RNA extracted from seeds in the milk, dough, and mature stages. The expression increased progressively, showing 1.65-fold and 11.47-fold upregulation in dough- and mature-stage seeds, respectively, compared to in milk-stage ones (

Figure 6B).

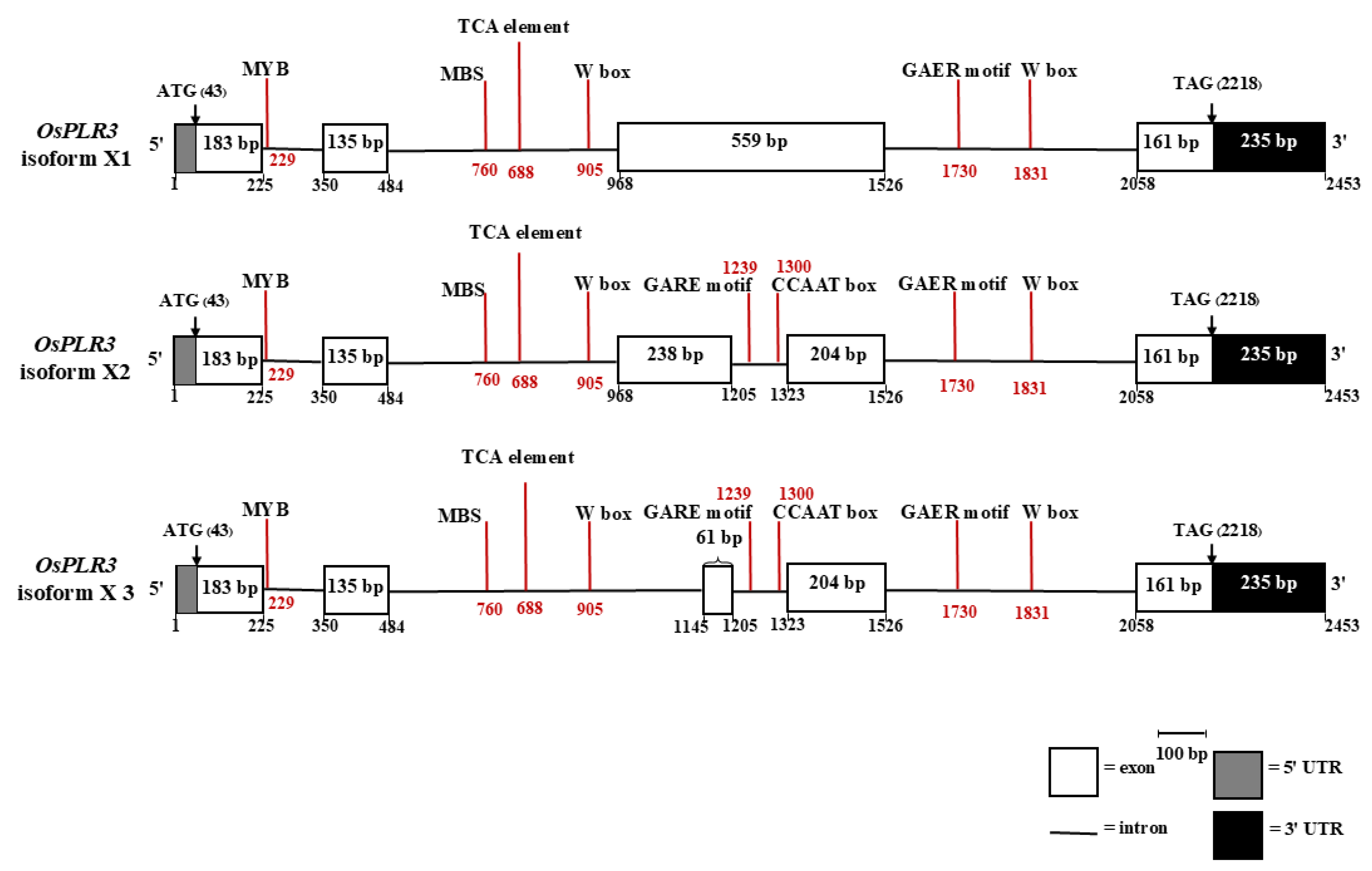

3.5. Cis-Regulatory Element Analysis of the OsPLR3 Isoforms

To explore potential transcriptional regulation of OsPLR3, cis-regulatory elements located within intronic regions were analyzed using the PlantCARE database. Multiple stress- and hormone-responsive elements were identified across all three isoforms (

Figure 7).

In isoform X1, five distinct cis-elements were found: a MYB binding site (CAACCA), an MBS (CAACTG), a TCA element (CCATCTTTTT), a W box (TTGACC), and two GARE motifs (TCTGTTG) associated with gibberellin responsiveness. These elements were located predominantly in introns 1 and 2, suggesting possible regulatory control via abiotic stress and hormonal cues, particularly gibberellin and salicylic acid.

Isoform X2 shared the same core cis-elements as X1, but with two additional motifs in intron 3: a CCAAT box (CAACGG), known to be a binding site for MYBHv1, which is involved in drought tolerance, and an additional GARE motif. These findings imply that isoform X2 may be more finely regulated in response to hormonal and environmental signals compared to X1.

In isoform X3, although the structure differed with the presence of a short 61 bp exon (from alternative splicing), the cis-element profile closely mirrored that of isoform X2. All key motifs—the MYB, MBS, W box, TCA-element, GARE, and CCAAT box—were present. However, despite its cis-element richness, isoform X3 showed no detectable transcript in RT-PCR, suggesting potential post-transcriptional or structural limitations.

Together, these results indicate that the differential distribution of cis-elements in the intronic regions may contribute to the isoform-specific expression of OsPLR3, particularly the dominance of isoform X2 under developmental and stress-responsive conditions. While all isoforms share core elements related to stress and hormonal responses, isoforms X2 and X3 possess additional GARE and CCAAT box motifs in later introns, suggesting possible roles in isoform-specific regulation of gene expression under abiotic stress and developmental signals.

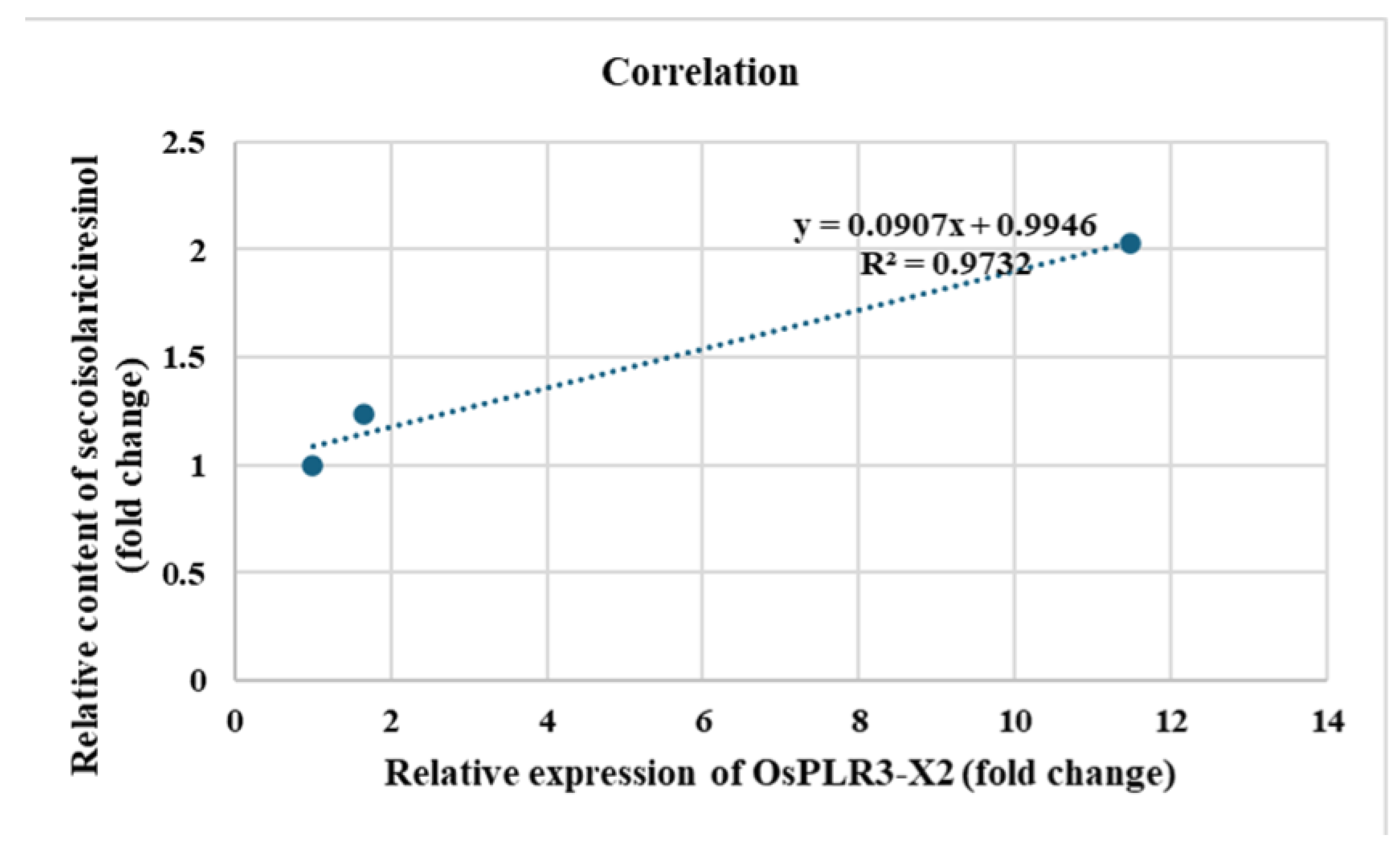

3.6. Secoisolariciresinol Accumulation During Seed Development in Mae Phaya Thong Dam Rice

Three lignan standards—secoisolariciresinol, matairesinol, and coumestrol—were used for calibration; however, only secoisolariciresinol was detected in the samples (Supplementary igure S3-S4) It was present at all developmental stages, with the highest concentration observed in mature grains (3.45 ± 0.19 mg/g of ground rice), followed by the soft dough stage (2.10 ± 0.25 mg/g) and the milk stage (1.70 ± 0.20 mg/g) (

Table 3). To further examine the molecular basis of this accumulation, the expression of OsPLR3 isoform X2 was analyzed across tissues and developmental stages. OsPLR3-X2 transcripts were predominantly detected in reproductive tissues, including developing seeds, and showed an increasing trend during seed maturation. The temporal pattern of OsPLR3-X2 expression corresponded with the progressive accumulation of secoisolariciresinol, with a strong positive correlation (r

2 = 0.99), as shown in

Figure 8. These findings suggest that secoisolariciresinol is a major lignan that accumulates progressively during seed maturation in this aromatic rice landrace.

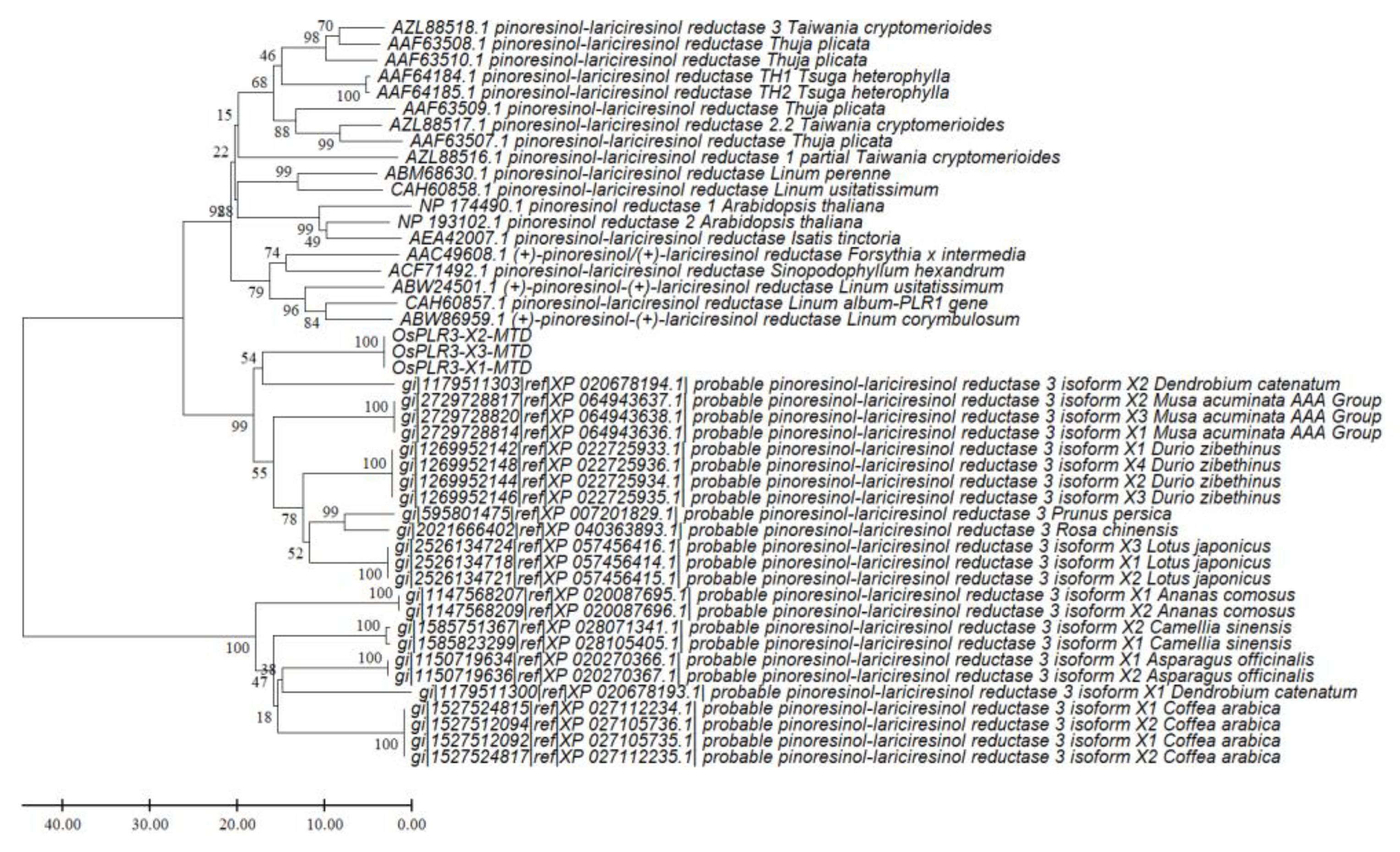

3.7. Phylogenetic Analysis of the OsPLR3 Isoforms

Phylogenetic reconstruction using the Minimum Evolution method (MEGA11) demonstrated that the three

Oryza sativa PLR3 isoforms (OsPLR3-X1, OsPLR3-X2, and OsPLR3-X3) grouped into a distinct clade that was clearly separated from the catalytically characterized PLR 1/2 proteins of dicot species, including

Linum usitatissimum, Forsythia intermedia, and

Arabidopsis thaliana (Figure 9). This clade also incorporated PLR3 homologs from both monocot and dicot species, indicating that OsPLR3 is part of a conserved PLR3 lineage across angiosperms. Within rice, the three isoforms formed a tight subgroup, with OsPLR3-X2 emerging as the predominant representative. Bootstrap support values confirmed the robustness of the branching pattern, reinforcing the distinct evolutionary placement of OsPLR3 isoforms within the PLR3 clade.

4. Discussion

This study provides compelling evidence that OsPLR3, a putative pinoresinol-lariciresinol reductase (PLR) gene in Oryza sativa cv. Mae Phaya Thong Dam, plays a functional role in lignan biosynthesis. Through a combination of gene cloning, transcript analysis, in silico structural modeling, molecular docking, and lignan quantification, we identified isoform X2 (OsPLR3-X2) as the predominant catalytically competent transcript.

OsPLR3-X2 exhibits structural and functional characteristics typical of the pinoresinol–lariciresinol reductase (PLR) family. This specific variant contains a conserved Rossmann-fold NAD(P)+ binding domain, which is essential for the enzymatic activity of PLRs. Additionally, the presence of the GXXGXXG motif and a catalytic lysine residue at position K133 further reinforces its functional integrity [

32]. The role of this lysine in the catalytic mechanism highlights the evolutionary conservation of this enzyme class across different plant species, suggesting that similar enzymes play analogous roles in lignan biosynthesis.

Several pinoresinol–lariciresinol reductases (PLRs) characterized in other species provide useful context for interpreting the putative function of OsPLR3-X2 in rice. For example, LuPLR1 from flax (Linum usitatissimum) catalyzes the sequential enantioselective reductions of pinoresinol to lariciresinol and subsequently to secoisolariciresinol, a central intermediate in lignan biosynthesis, as evidenced by Meagher et al. [

33], who isolated and characterized the lignans pinoresinol and isolariciresinol from flaxseed meal. The stereochemical complexity of these lignans is further illustrated by Sicilia et al. [

34], who provided a detailed stereochemical profile of lignans in flaxseed and pumpkin seeds. In addition, Hano et al. [

9] demonstrated that expression of the LuPLR gene in developing flax seed coats correlates with accumulation of its main lignan, secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG), confirming the in planta enzymatic context of lignan biosynthesis. A broader picture of PLR function across plants is provided by Markulin et al. [

8], who reviewed PLR activity, stereospecificity, and regulation, confirming their pivotal role in forming lariciresinol or secoisolariciresinol from pinoresinol across species. The presence of multiple PLR enzymes with opposite enantiospecificities in flax, such as LuPLR1 and LuPLR2, dictates the organ-specific enantiomeric composition of lignans—highlighted by Hemmati et al. [

10]. Altogether, these findings underscore the structural and functional parallels between PLRs in dicots and gymnosperms, suggesting that OsPLR3-X2 may perform analogous enzymatic roles in monocot lignan biosynthesis.

Molecular docking demonstrated that OsPLR3-X2 possesses strong binding affinities for both pinoresinol and lariciresinol, supporting its catalytic competence in lignan reduction. These results are consistent with the hypotheses of Fryatt and Botting, as the observed substrate recognition parallels the molecular interactions proposed for synthetic scaffolds designed to mimic PLR-mediated transformations in agricultural and industrial applications [

35]. In the broader context of the enzymatic community, the behavior of OsPLR3-X2 resembles that of previously characterized counterparts, such as Podophyllum secisolariciresinol dehydrogenase, which notably shares a structural motif with OsPLR3-X2 [

36]. Importantly, the expression pattern of OsPLR3-X2 was tightly correlated with the developmental accumulation of secoisolariciresinol, as revealed by qRT-PCR and HPLC analysis. The transcript level of OsPLR3-X2 increased significantly from the milky to the mature grain stage, which paralleled the progressive accumulation of secoisolariciresinol. This temporal alignment strongly supports its role in grain-specific lignan biosynthesis [

9,

37].

Our data also suggest isoform-specific regulation of OsPLR3 via intronic cis-regulatory elements, including the MYB, GARE motif, MBS, and CCAAT box elements—regulatory motifs associated with hormone responsiveness and abiotic stress responses [

8]. These elements were especially enriched in isoform X2 compared to X1 and X3, possibly contributing to its tissue-specific and developmental expression. Interestingly, despite having similar cis-elements, isoform X3 lacked both the catalytic lysine and a properly formed NADPH-binding pocket, and its transcript was undetectable, suggesting that it may represent a non-functional transcript subject to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD), a conserved post-transcriptional surveillance mechanism in plants that not only degrades aberrant transcripts but also regulates gene expression in response to environmental cues and developmental signals [

38].

Comparative studies on dicot species support the broader relevance of these findings. In flax, LuPLR1 shows strong correlation with lignan biosynthesis in seeds [

39], while in sesame (

Sesamum indicum), expression of SiPLR1 closely mirrors lignan accumulation and has been functionally validated in vitro [

11]. Forsythia PLR has also been extensively studied for its stereospecificity and tissue distribution [

40]. However, in monocots such as rice, the role of PLR genes has remained elusive, with only trace lignan content previously reported in hulls and bran [

13]. Our identification and validation of OsPLR3-X2 thus fills a critical knowledge gap, indicating that monocots may possess a conserved yet underexplored lignan biosynthetic capacity.

The phylogenetic analysis positioned OsPLR3 within the PLR3 subfamily, clearly distinct from the well-characterized PLR1/2 lineage. This placement suggests that PLR3 represents an evolutionarily conserved branch of the PLR gene family that diverged through an ancient duplication predating the monocot–dicot split [

8]. OsPLR3 proteins retain key catalytic motifs, including the NADPH-binding Rossmann fold and Lys133, consistent with reductase activity [

9]. Their separation from PLR1/2, however, implies divergence in substrate preference or physiological roles [

40,

41]. In rice, isoform X2 predominates across tissues, whereas X1 and X3 likely reflect alternative splicing without distinct evolutionary lineages. This points to functional specialization of OsPLR3 in monocots, possibly linked to lignan metabolism or related pathways [

7,

8]. Together, these findings support a model in which PLR3 originated from ancestral gene duplication and has been maintained across angiosperms. Within this framework, OsPLR3 exemplifies the monocot branch, with X2 as the dominant functional isoform in rice.

Furthermore, the predicted structural similarity between OsPLR3-X2 and gymnosperm PLRs such as TpPLR1, despite phylogenetic divergence, points to evolutionary conservation of the lignan biosynthetic machinery across major plant lineages. This conservation may reflect the physiological importance of lignans as antioxidants and defense compounds under diverse environmental conditions [

2].

While our findings strongly support that OsPLR3-X2 is a functional PLR homolog, further functional validation is warranted. Recombinant protein expression and in vitro enzymatic assays could confirm the catalytic conversion of pinoresinol to lariciresinol and secoisolariciresinol, as demonstrated for LuPLR1 and SiPLR1 [

9,

11]. Additionally, heterologous expression of OsPLR3-X2 in model systems such as

Arabidopsis thaliana or

Saccharomyces cerevisiae—followed by lignan quantification—would provide robust functional evidence. These approaches, successfully applied for other species, would not only confirm enzymatic activity but also shed light on subcellular localization and potential protein–protein interactions [

42,

43].

In summary, OsPLR3-X2 represents a catalytically competent PLR isoform that likely contributes to the NADPH-dependent reduction of pinoresinol derivatives during lignan biosynthesis in rice seeds. These findings not only expand our understanding of specialized metabolism in monocots but also offer a molecular target for metabolic engineering and breeding programs aimed at enhancing lignan content in rice grains for functional food and nutraceutical applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M., P.M., K.L., and W.P.; methodology, P.M. and K.L.; validation, C.M., P.M., and K.L.; investigation, C.M., K.L., and P.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M., K.L., and P.M.; writing—review and editing, C.M., K.L., and P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

The molecular structure of the OsPLR3 gene and its predicted alternative transcripts in Mae Phaya Thong Dam rice, including the positions of the primers for primer design to detect its specific isoform expression.

Figure 1.

The molecular structure of the OsPLR3 gene and its predicted alternative transcripts in Mae Phaya Thong Dam rice, including the positions of the primers for primer design to detect its specific isoform expression.

Figure 2.

The deduced amino acid sequences of isoform X1, X2 and X3 of OsPLR3 in Mae Phaya Thong Dam rice. The grey highlights indicate “Rossmann-fold NAD(P)(+)-binding proteins. The red letters indicate NAD(P) binding sites, and the green K (lysine) indicates active site lysine of PLR enzyme.

Figure 2.

The deduced amino acid sequences of isoform X1, X2 and X3 of OsPLR3 in Mae Phaya Thong Dam rice. The grey highlights indicate “Rossmann-fold NAD(P)(+)-binding proteins. The red letters indicate NAD(P) binding sites, and the green K (lysine) indicates active site lysine of PLR enzyme.

Figure 3.

The multiple sequence alignment of isoforms X1, X2, and X3 of OsPLR3 in Mae Phaya Thong Dam rice and LuPLR1 in flax (Linum usitatissimu). The conserved motif “GXXGXXG” is indicated by the red square and the lysine (K) active site is indicated by the red arrow.

Figure 3.

The multiple sequence alignment of isoforms X1, X2, and X3 of OsPLR3 in Mae Phaya Thong Dam rice and LuPLR1 in flax (Linum usitatissimu). The conserved motif “GXXGXXG” is indicated by the red square and the lysine (K) active site is indicated by the red arrow.

Figure 4.

Predicted 3D structures of the OsPLR3 isoforms X1 (A–C), X2 (D–F), and X3 (G–I) generated using I-TASSER. (A, D, G) Ribbon cartoon models of isoforms X1, X2, and X3, respectively, colored from the N-terminus (blue) to C-terminus (red). The structures of isoforms X1 and X2 were modeled using a Pinus taeda PLR (PDB ID: 1qycA) and Thuja plicata PLR (PDB ID: 1qyc), respectively, while X3 was modeled using an IFR homolog from P. taeda (PDB ID: d1qyc). (B, E, H) Backbone trace representations of the structural superimposition with their respective templates. (C, F, I) Predicted ligand binding sites highlighting interaction pockets. Isoforms X1 (C) and X2 (F) show specific binding to NADP(H) (green spheres), while isoform X3 (I) lacks an NADP(H) binding site and instead shows coordination with a Mg2+ ion (green arrows). Residues involved in binding are shown in stick representation and enclosed in red dashed circles.

Figure 4.

Predicted 3D structures of the OsPLR3 isoforms X1 (A–C), X2 (D–F), and X3 (G–I) generated using I-TASSER. (A, D, G) Ribbon cartoon models of isoforms X1, X2, and X3, respectively, colored from the N-terminus (blue) to C-terminus (red). The structures of isoforms X1 and X2 were modeled using a Pinus taeda PLR (PDB ID: 1qycA) and Thuja plicata PLR (PDB ID: 1qyc), respectively, while X3 was modeled using an IFR homolog from P. taeda (PDB ID: d1qyc). (B, E, H) Backbone trace representations of the structural superimposition with their respective templates. (C, F, I) Predicted ligand binding sites highlighting interaction pockets. Isoforms X1 (C) and X2 (F) show specific binding to NADP(H) (green spheres), while isoform X3 (I) lacks an NADP(H) binding site and instead shows coordination with a Mg2+ ion (green arrows). Residues involved in binding are shown in stick representation and enclosed in red dashed circles.

Figure 5.

Predicted binding interactions between the OsPLR3 isoforms and their respective lignan substrates, pinoresinol and lariciresinol, based on molecular docking simulations using CB-Dock2. (A,B) Docking of isoform X1 with pinoresinol (A) and lariciresinol (B). (C,D) Docking of isoform X2 with pinoresinol (C) and lariciresinol (D). Protein structures are shown as ribbon models (dark blue), while ligands are displayed as space-filling models (gray: carbon; red: oxygen). Key interacting residues are labeled and visualized in stick representation.

Figure 5.

Predicted binding interactions between the OsPLR3 isoforms and their respective lignan substrates, pinoresinol and lariciresinol, based on molecular docking simulations using CB-Dock2. (A,B) Docking of isoform X1 with pinoresinol (A) and lariciresinol (B). (C,D) Docking of isoform X2 with pinoresinol (C) and lariciresinol (D). Protein structures are shown as ribbon models (dark blue), while ligands are displayed as space-filling models (gray: carbon; red: oxygen). Key interacting residues are labeled and visualized in stick representation.

Figure 6.

(A) The expression of isoform X2 was detected in various tissues, including leaf tissues at 10 and 60 days of age (No.1 and No.3, respectively), stem tissues at 10 and 60 days of age (No.2 and No.4, respectively), and flower (No.5) and milky seed (No.6) tissues. M: 1 kb Plus DNA Ladder (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). (B) The expression change in OsPLR3-X2 during seed development of Mae Phaya Thong Dam rice. Values are expressed as relative fold change, with the expression in milky seeds set as one.

Figure 6.

(A) The expression of isoform X2 was detected in various tissues, including leaf tissues at 10 and 60 days of age (No.1 and No.3, respectively), stem tissues at 10 and 60 days of age (No.2 and No.4, respectively), and flower (No.5) and milky seed (No.6) tissues. M: 1 kb Plus DNA Ladder (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). (B) The expression change in OsPLR3-X2 during seed development of Mae Phaya Thong Dam rice. Values are expressed as relative fold change, with the expression in milky seeds set as one.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the gene structures and intron-located cis-regulatory elements in OsPLR3 isoforms X1, X2, and X3. Exons are shown as white boxes, introns as horizontal lines, and untranslated regions (UTRs) as shaded boxes (5′ UTR, gray; 3′ UTR, black). Red vertical lines indicate the positions of cis-regulatory elements identified via PlantCARE analysis, including the MYB (CAACCA), MBS (CAACTG), TCA-element (CCATCTTTTT), W box (TTGACC), and GARE (TCTGTTG), and CCAAT box (CAACGG) motifs.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the gene structures and intron-located cis-regulatory elements in OsPLR3 isoforms X1, X2, and X3. Exons are shown as white boxes, introns as horizontal lines, and untranslated regions (UTRs) as shaded boxes (5′ UTR, gray; 3′ UTR, black). Red vertical lines indicate the positions of cis-regulatory elements identified via PlantCARE analysis, including the MYB (CAACCA), MBS (CAACTG), TCA-element (CCATCTTTTT), W box (TTGACC), and GARE (TCTGTTG), and CCAAT box (CAACGG) motifs.

Figure 8.

Correlation between the relative expression of OsPLR3-X2 and the accumulation of secoisolariciresinol in Oryza sativa cv. Mae Phaya Thong Dam. The linear regression equation (y = 0.1542x + 1.6909) and the coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.9732) demonstrate a strong positive relationship between OsPLR3-X2 transcript levels and secoisolariciresinol content (mg·g−1 ground rice).

Figure 8.

Correlation between the relative expression of OsPLR3-X2 and the accumulation of secoisolariciresinol in Oryza sativa cv. Mae Phaya Thong Dam. The linear regression equation (y = 0.1542x + 1.6909) and the coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.9732) demonstrate a strong positive relationship between OsPLR3-X2 transcript levels and secoisolariciresinol content (mg·g−1 ground rice).

Figure 9.

Phylogenetic tree of pinoresinol–lariciresinol reductase (PLR) proteins constructed using the Minimum Evolution method in MEGA11. The analysis included three Oryza sativa OsPLR3 isoforms (X1, X2, and X3), PLR3 homologs from both monocot and dicot species, and functionally characterized PLR 1/2 proteins from dicots. Bootstrap values (1000 replicates) are shown at the nodes. The tree demonstrates that OsPLR3 isoforms cluster with the PLR3 subfamily across angiosperms, forming a lineage distinct from the validated PLR1/2 clade.

Figure 9.

Phylogenetic tree of pinoresinol–lariciresinol reductase (PLR) proteins constructed using the Minimum Evolution method in MEGA11. The analysis included three Oryza sativa OsPLR3 isoforms (X1, X2, and X3), PLR3 homologs from both monocot and dicot species, and functionally characterized PLR 1/2 proteins from dicots. Bootstrap values (1000 replicates) are shown at the nodes. The tree demonstrates that OsPLR3 isoforms cluster with the PLR3 subfamily across angiosperms, forming a lineage distinct from the validated PLR1/2 clade.

Table 1.

Molecular docking results of the OsPLR3 isoforms (X1 and X2) with pinoresinol and lariciresinol, as predicted by CB-Dock2.

Table 1.

Molecular docking results of the OsPLR3 isoforms (X1 and X2) with pinoresinol and lariciresinol, as predicted by CB-Dock2.

| OsPLR3 Isoform |

Ligand |

Vina Score (kcal/mol) |

Binding Pocket (CurPocket ID) |

Cavity

Volume (Å3) |

Key Contact Residues† |

Figure |

| X1 |

Pinoresinol |

–8.5 |

C2 |

934 |

GLU112, TYR113, ASN153, PHE154, LEU155, TYR158, LYS133

|

5A |

| X1 |

Lariciresinol |

–9.6 |

C2 |

934 |

GLU112, TYR113, ASN153, PHE154, LEU155, TYR158, LYS133

|

5B |

| X2 |

Pinoresinol |

–8.4 |

C2 |

1028 |

GLU112, TYR113, GLY114, LEU115, ASN153, PHE154, LEU155, LYS133

|

5C |

| X2 |

Lariciresinol |

–9.2 |

C2 |

1028 |

GLU112, TYR113, GLY114, LEU115, ASN153, PHE154, LEU155, LYS133

|

5D |

Table 2.

The designed primers for identifying the expression of isoforms X1, X2, and X3 of OsPLR3.

Table 2.

The designed primers for identifying the expression of isoforms X1, X2, and X3 of OsPLR3.

| Primer name |

Sequence (5′→3′) |

Tm |

Ta |

PCR product size (base pairs) |

| Isoform X1 |

Isoform X2 |

Isoform X3 |

| OsPLR3.Ex.F |

AAGATTACCCGAGCCTGCTG |

60.5 |

56 |

584 |

487 |

290 |

| OsPLR3.Ex.R |

GACATTTCCCGAGGGTCTCA |

60.5 |

56 |

Table 3.

Secoisolariciresinol content (mg/g ground rice) in rice grains harvested at different developmental stages.

Table 3.

Secoisolariciresinol content (mg/g ground rice) in rice grains harvested at different developmental stages.

| Rice Extract |

Secoisolariciresinol (mg/g ground rice) |

| Milky |

1.70 ± 0.20ᵃ |

| Soft dough |

2.10 ± 0.25b

|

| Maturity |

3.45 ± 0.19c

|