Submitted:

09 October 2025

Posted:

10 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Relationship Between The Endocrine System and Breast Cancer

1.3. Current Endocrine Treatment

1.4. Efficacy of AET

1.5. Compliance and Adherence of AET

1.6. Reasons for Non-Adherence

1.7. AET’s Effect on Bone Health

1.8. Aims of Study

2. Methodology

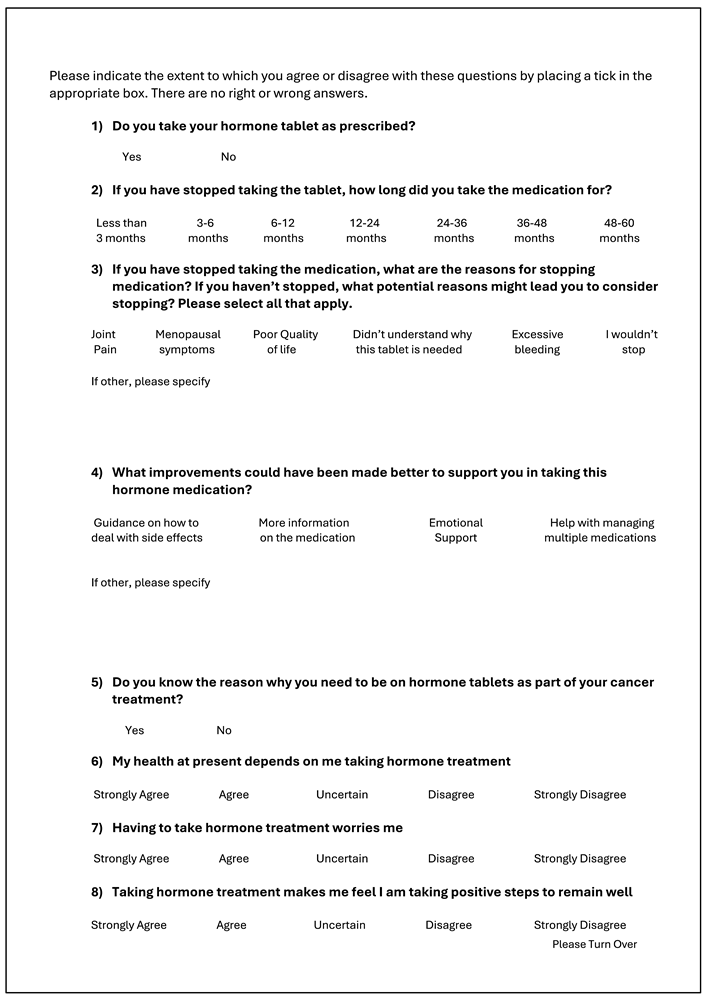

2.1. Questionnaire

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Questionnaire Creation

2.1.3. Data Collection

2.2. Semi-Structured Telephone Interviews

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Study Design

2.2.3. Data Collection

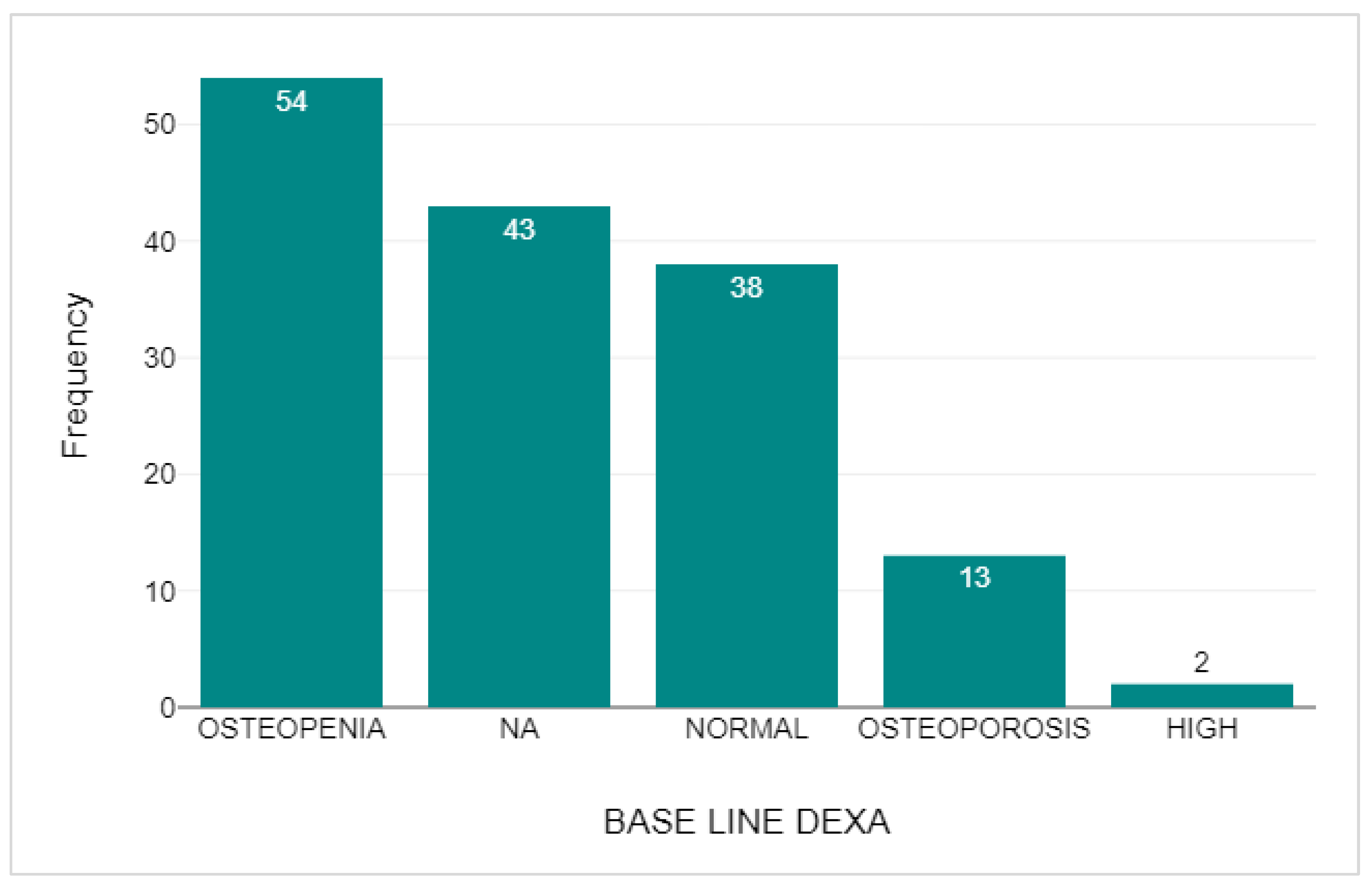

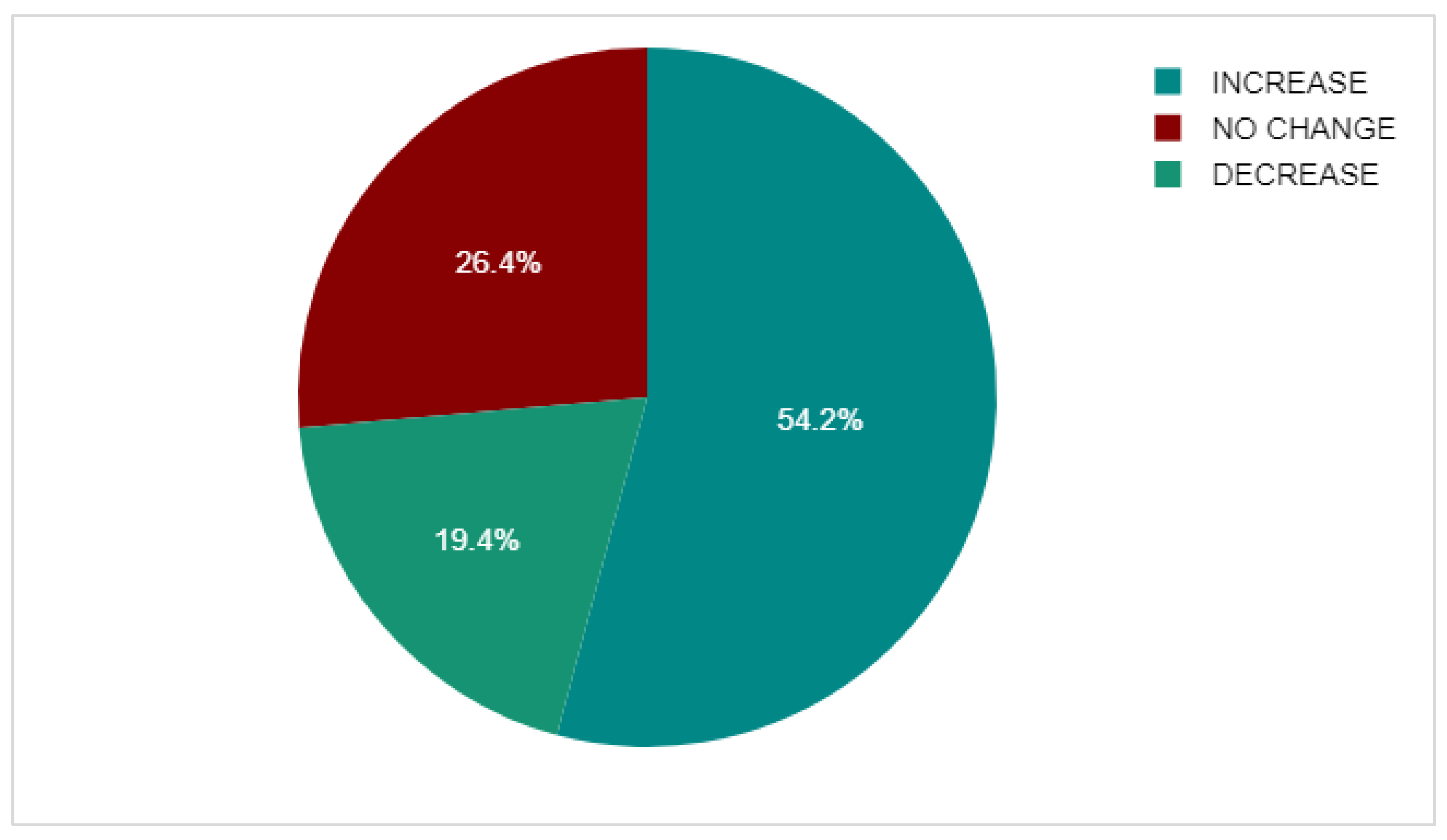

2.3. DEXA Scan Comparison

2.3.1. Participants

2.3.2. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

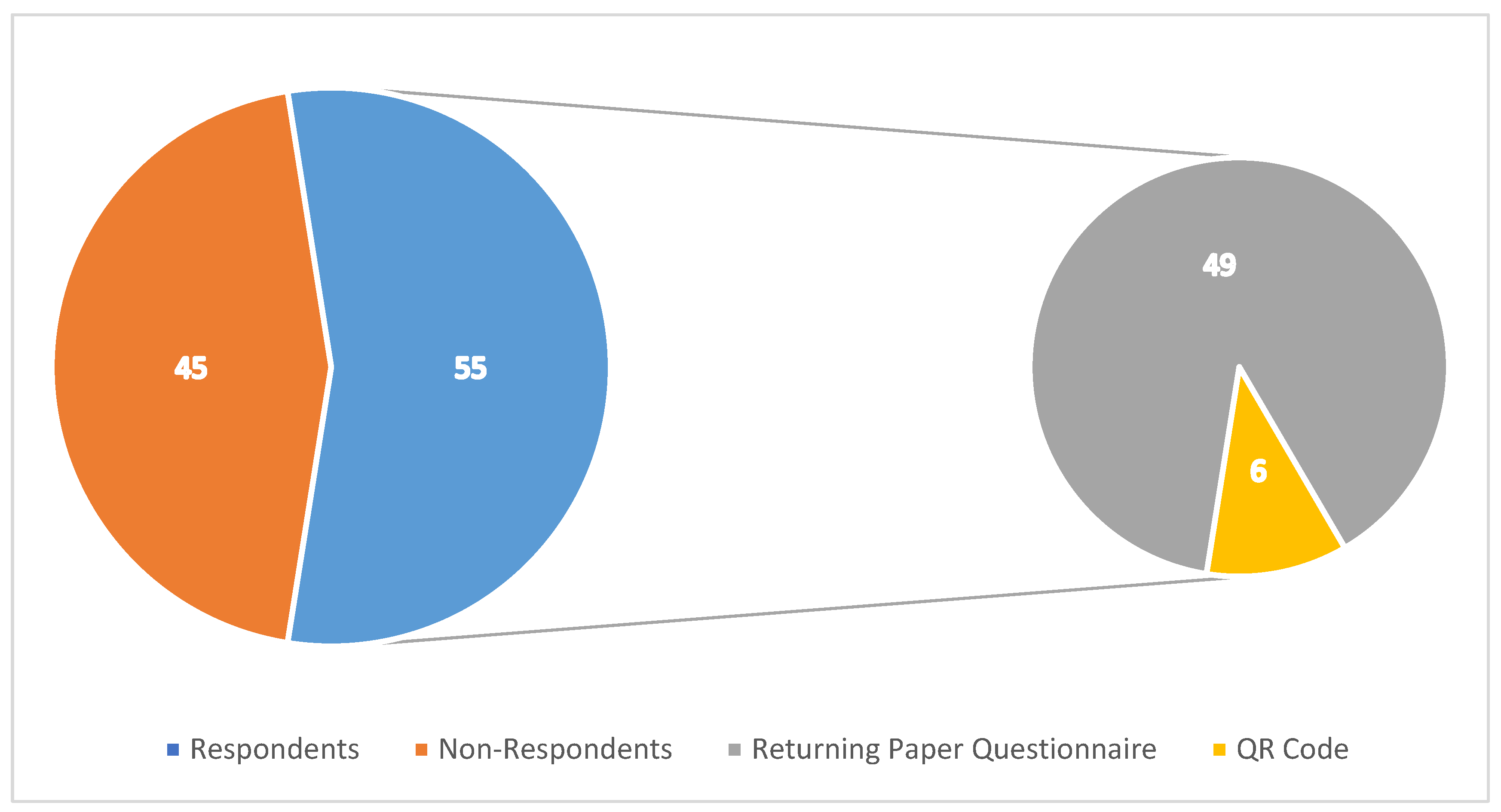

3.1. Response Rates

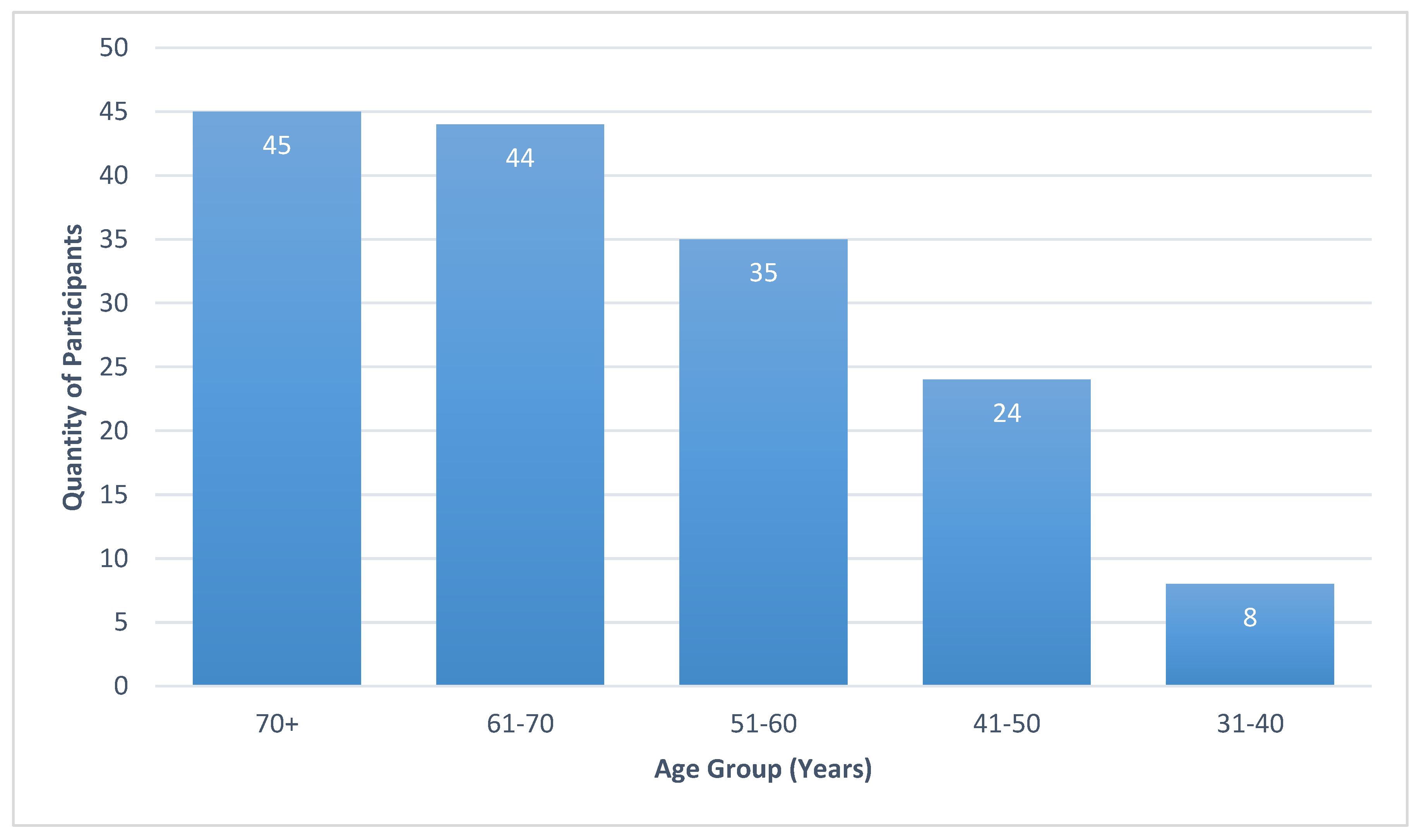

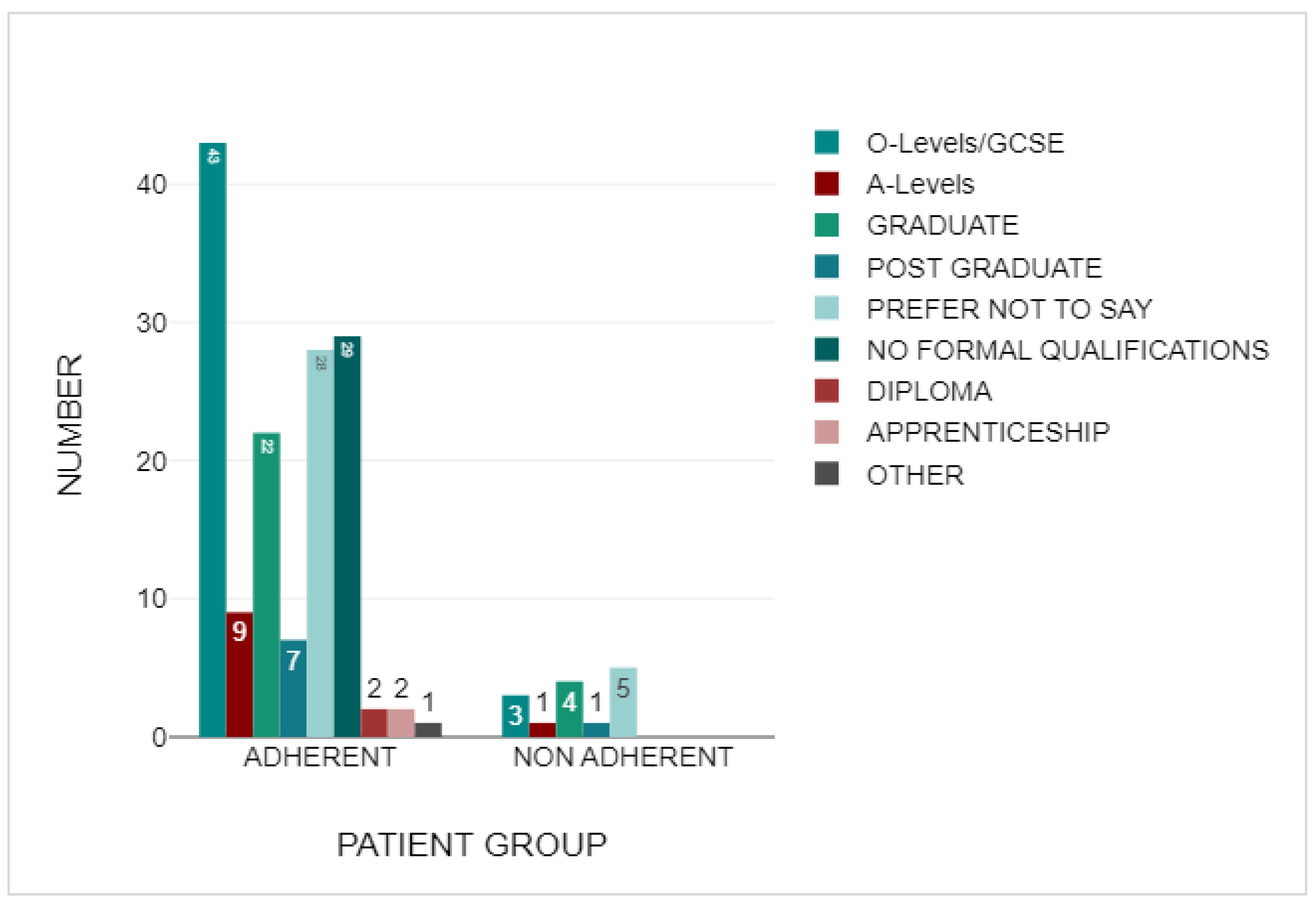

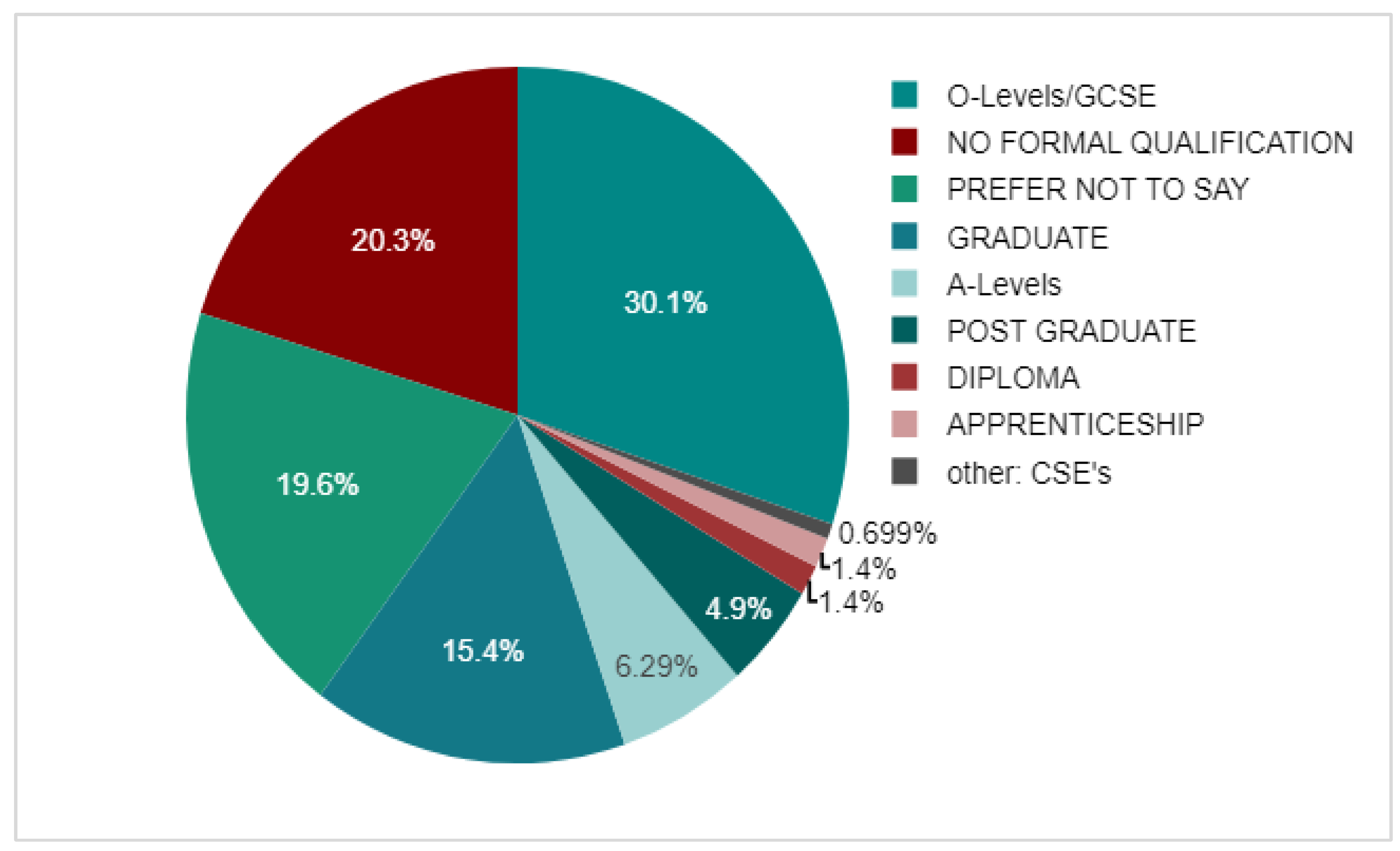

3.2. Demographics

3.3. Adherent Group

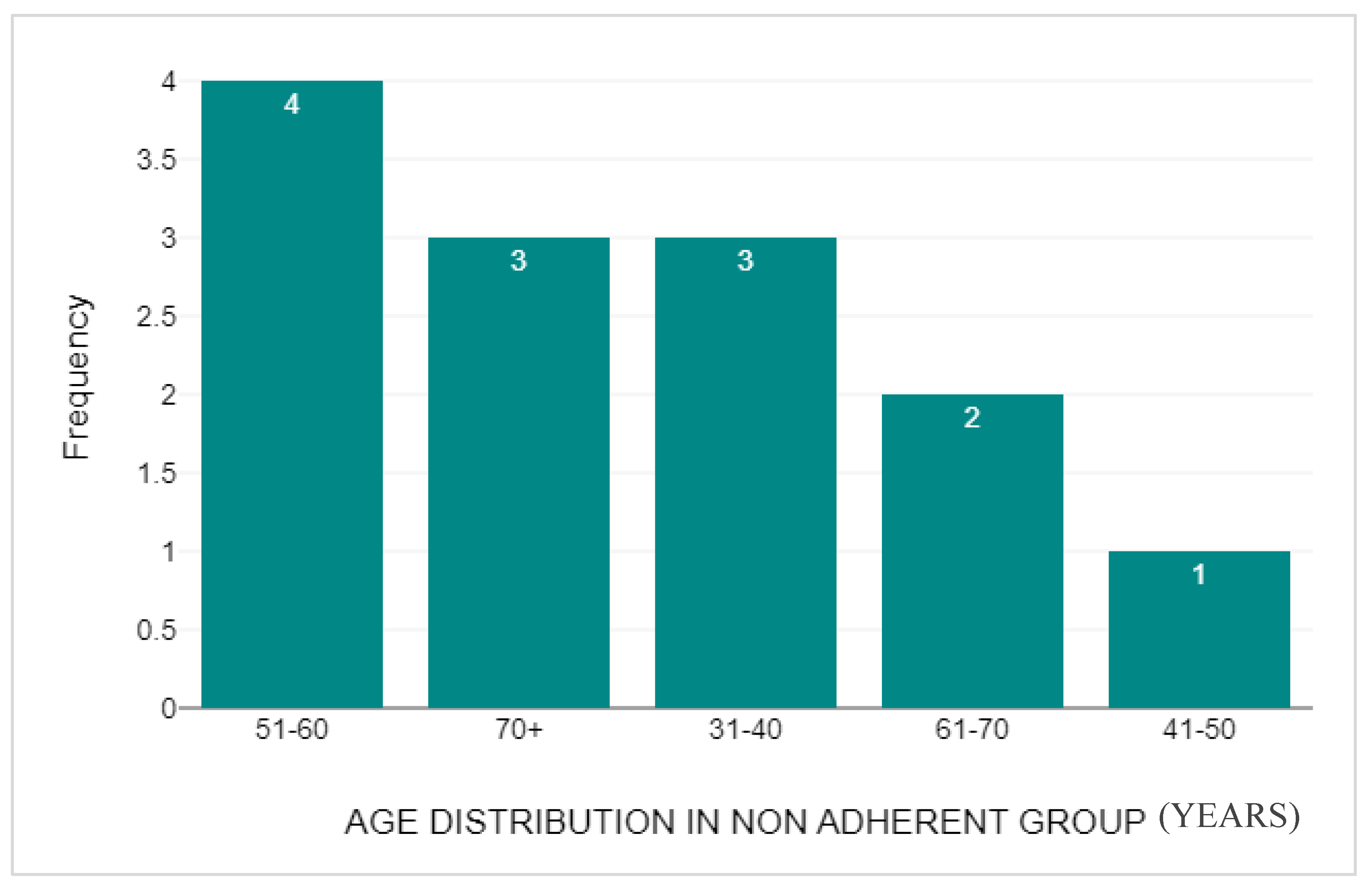

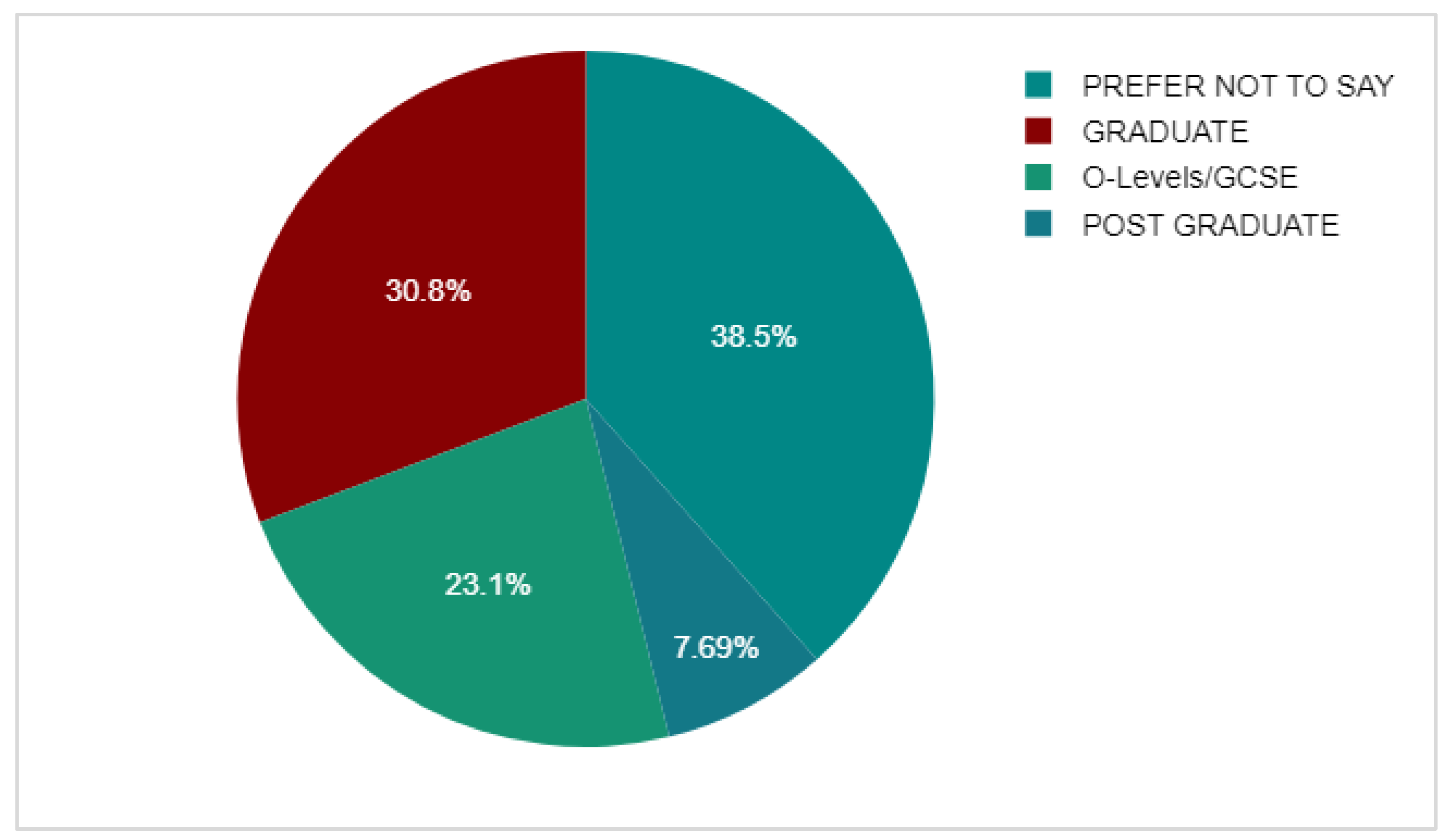

3.4. Non-Adherent Group

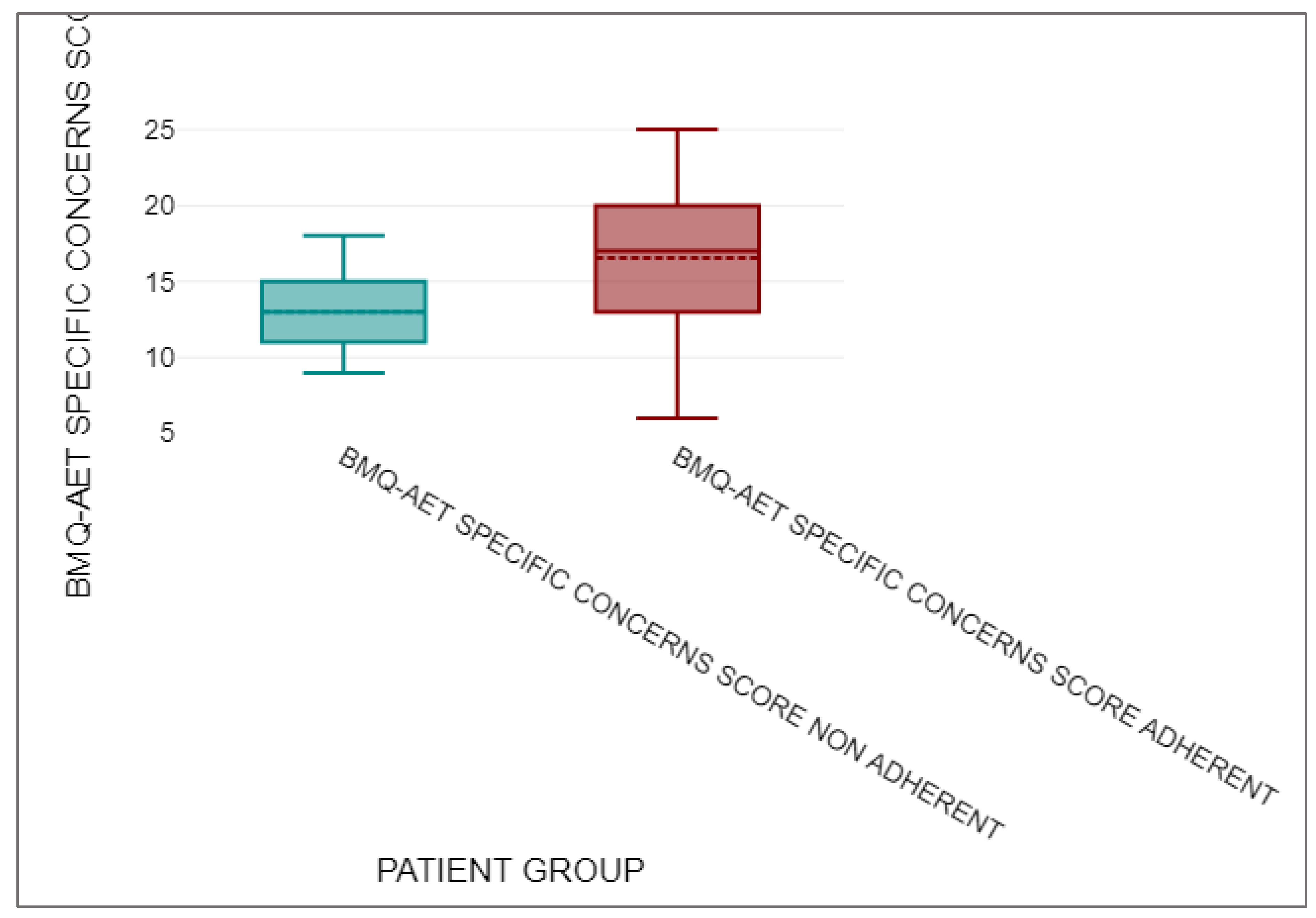

3.5. BMQ-AET Score Comparison

3.6. DEXA Scan Comparison

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Strengths

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusion

6. Appendix: The AET Adherence Questionnaire

Source of Funding

| N | MEAN | P-VALUE | |

| NON-ADHERENT | 13 | 17.54 | <0.001 |

| ADHERENT | 143 | 10.86 |

| N | MEAN | P-VALUE | |

| NON-ADHERENT | 13 | 13 | 0.002 |

| ADHERENT | 143 | 16.54 |

Abbreviations

References

- Cancer Research UK. Breast Cancer Statistics. [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 September 27]. Available from: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/breast-cancer#heading-Zero.

- World Health Organisation. Breast Cancer. [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 September 27]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer.

- Joint Formulary Committee (JFC). Breast Cancer. 2024 London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press. Available from: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatmentsummaries/breast-cancer/ [cited 2024 October 15].

- Rosso, R., D’Alonzo, M., Bounous, V.E., Actis, S., Cipullo, I., Salerno, E, Biglia, N. Adherence to Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy in Breast Cancer Patients. Current Oncology 2023 Jan 21; 30(2): 1461-1472. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9955792/.

- Al-Shami K, Awadi S, Khamees A, Alsheikh AM, Al-Sharif S, Ala’ Bereshy R, Al-Eitan SF, Banikhaled SH, Al-Qudimat AR, Al-Zoubi RM, Al Zoubi MS. Estrogens and the risk of breast cancer: A narrative review of literature. Heliyon. 2023 Sep 17;9(9): e20224. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10559995/.

- Russo J, Russo IH. The role of estrogen in the initiation of breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006 Dec;102(1-5):89-96. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1832080/.

- Lee JJ, Jung YL, Cheong TC, Espejo Valle-Inclan J, Chu C, Gulhan DC, Ljungström V, Jin H, Viswanadham VV, Watson EV, Cortés-Ciriano I, Elledge SJ, Chiarle R, Pellman D, Park PJ. ERα-associated translocations underlie oncogene amplifications in breast cancer. Nature. 2023 Jun;618(7967):1024-1032. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37198482/.

- Patel P, Jacobs TF. Tamoxifen. StatPearls [Internet]. 2025 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532905/.

- Peters A, Tadi P. Aromatase Inhibitors. [Updated 2023 Jul 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557856/.

- University of Oxford [Internet]. Aromatase inhibitors better than tamoxifen at reducing risk of breast cancer recurrence in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. 2022 [cited 6 November 2024]. University of Oxford Medical Sciences Division. Available from: https://www.ndph.ox.ac.uk/news/aromatase-inhibitors-are-better-than-tamoxifen-at-reducing-the-risk-of-breast-cancer-recurrence-in-premenopausal-as-well-as-postmenopausal-women.

- Simpson ER. Sources of estrogen and their importance. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003 Sep;86(3-5):225-30. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14623515/.

- McCann, K.E., Goldfarb, S.B., Traina, T.A., Regan, M.M., Vidula, N., Kaklamani, V. Selection of appropriate biomarkers to monitor effectiveness of ovarian function suppression in pre-menopausal patients with ER+ breast cancer. npj Breast Cancer 2024 [cited 6 November 2024] 10, 8 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Early Breast Cancer Trialist’s Collaborative Group. Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. The Lancet. 2005 May 14; 365(9472), 1687–1717. Available from https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(05)66544-0/abstract.

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG); Davies C, Godwin J, Gray R, Clarke M, Cutter D, Darby S, McGale P, Pan HC, Taylor C, Wang YC, Dowsett M, Ingle J, Peto R. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2011 Aug 27;378(9793):771-84. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3163848/.

- ATAC Trialist’s Group. Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years’ adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. The Lancet 2005 Jan; 365(9453), 60-62. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673604176666.

- Davis, S.A., Feldman, S.R. Using Hawthorne Effects to Improve Adherence in Clinical Practice: Lessons From Clinical Trials. JAMA Dermatology 2013;149(4),490–491. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamadermatology/fullarticle/1679347.

- Mir, T.H. (2023) Adherence Versus Compliance. HCA Healthcare Journal of Medicine 2023 April 28; 4(2), 219-220. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10324868/.

- Wassermann, J., Rosenberg, S.M. (2017) Treatment Decisions and Adherence to Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy in Breast Cancer. Current Breast Cancer Reports 2017 June;9, 100– 110. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12609-017-02485.

- Chamalidou, C., Nasic, S., Linderholm, B. Compliance to adjuvant endocrine therapy and survival in breast cancer patients. Cancer Treatment and Research Communications 2023; 35, 100704. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2468294223000254.

- Hershman, D.L., Shao, T., Kushi, L.H., Buono, D., Tsai, W.Y., Fehrenbacher, L., Kwan, M., Gomez, S.L., Neugut, A.I. Early discontinuation and non-adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat 2010 Oct 2; 126, 529–537. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3462663/.

- McCowan, C., Wang, S., Thompson, A.M., Makubate, B., Petrie, D.J. The value of high adherence to tamoxifen in women with breast cancer: a community-based cohort study. Br J Cancer 2013 Aug 15; 109(5), 1172-80. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3778308/.

- Yussof, I., Mohd Tahir, N.A., Hatah, E., Mohamed Shah, N. (2022) Factors influencing five-year adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer patients: A systematic review. The Breast 2022 Jan 24; 62: 22-35. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8818734/.

- Gremke, N., Griewing, S., Chaudhari, S., Upadhyaya, S., Nikolov, I., Kostev, K., Kalder, M. (2022) Persistence with tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors in Germany: a retrospective cohort study with 284,383 patients. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 2022 Sep 23; 149(8), 4555-4562. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10349696/.

- Ali, A., Xiem, Z., Stanko, L., De Leo, E., Hong, YR., Bian, J., Daily, K.C. Endocrine adherence in male versus female breast cancer: a seer-medicare review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2022 Feb 10; 192, 491–499. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10549-022-06536-0.

- Marcum ZA, Gellad WF. Medication adherence to multidrug regimens. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012 May;28(2):287-300. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3335752/.

- Panahi, S., Rathi, N., Hurley, J., Sundrud, J., Lucero, M., Kamimura, A. Patient Adherence to Health Care Provider Recommendations and Medication among Free Clinic Patients. J Patient Exp 2022 Feb 9;9, 23743735221077523. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8832560/.

- Lambert LK, Balneaves LG, Howard AF, Chia SK, Gotay CC. Understanding adjuvant endocrine therapy persistence in breast Cancer survivors. BMC Cancer. 2018 Jul 11;18(1):732. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6042363/.

- Toivonen, K.I., Williamson, T.M., Carlson, L.E., Walker, L.M., Campbell, T.S. Potentially Modifiable Factors Associated with Adherence to Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy among Breast Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. Cancers (Basel) 2020 Dec 31; 13(1), 107. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7794693/.

- Cancer Research UK [Internet]. 2024. Side effects of hormone therapy in women. [cited 8 November 2024]. Available from: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/treatment/hormonetherapy/side-effects-women.

- Wagner LI, Zhao F, Goss PE, et al. Patient-reported predictors of early treatment discontinuation: treatment-related symptoms and health-related quality of life among postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer randomized to anastrozole or exemestane on NCIC Clinical Trials Group (CCTG) MA.27 (E1Z03). Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019 Jun 1;169(3):537-548. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6092930/.

- Fleming, L., Agnew, S., Peddie, N., Crawford, M., Dixon, D., MacPherson, I. The impact of medication side effects on adherence and persistence to hormone therapy in breast cancer survivors: A quantitative systematic review. Breast 2022 May 14; 64,63-84. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9130570/.

- Peddie, N., Agnew, S., Crawford, M., Dixon, D., MacPherson, I., Fleming, L. The impact of medication side effects on adherence and persistence to hormone therapy in breast cancer survivors: A qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis. Breast 2021; 58, 147-159. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34049260/.

- Briot, K., Tubiana-Hulin, M., Bastit, L., Kloos, I., Roux, C. Effect of a switch of aromatase inhibitors on musculoskeletal symptoms in postmenopausal women with hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer: the ATOLL (articular tolerance of letrozole) study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010 Feb; 120(1), 127-34. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20035381/.

- Al-Tarawneh, F., Ali, T., Al-Tarawneh, A., Altwalbeh, D., Gogazeh, E., Bdair, O., Algaralleh, A. Study of Adherence Level and the Relationship Between Treatment Adherence, and Superstitious Thinking Related to Health Issues Among Chronic Disease Patients in Southern Jordan: Cross-Sectional Study. Patient Prefer Adherence 2023 Mar 9; 17, 605-614. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10010127/.

- Berkowitz, M.J., Thompson, C.K., Zibecchi, L.T., Lee, M.K., Streja, E., Berkowitz, J.S., Wenziger, C.M., Baker, J.L., DiNome, M.L., Attai, D.J. (2021) How patients experience endocrine therapy for breast cancer: an online survey of side effects, adherence, and medical team support. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 15(1),29-39. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7430212/.

- Ramchand, S.K., Cheung, Y-M., Yeo, B., Grossmann, M. The effects of adjuvant endocrine therapy on bone health in women with breast cancer. Journal of Endocrinology 2019; 241(3), 111-124. Available from: https://joe.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/joe/241/3/JOE-19-0077.xml.

- Fisher B., Costantino, J.P., Wickerham, D.L., Cecchini, R.S., Cronin, W.M., Robidoux, A., Bevers, T.B., Kavanah, M.T., Atkins, J.N., Margolese, R.G., Runowicz, C.D., James, J.M., Ford, L.G., Wolmark, N. Tamoxifen for the Prevention of Breast Cancer: Current Status of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2005; 97(22), 1652–1662. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jnci/article/97/22/1652/2521468?login=true.

- Ahlstedt Karlsson, S., Wallengren, C., Olofsson Bagge, R., Henoch, I. “It is not just any pill”- Women’s experiences of endocrine therapy after breast cancer surgery. European Journal of Cancer Care 2019; 28(3), e13009. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30748038/.

- Verbrugghe, M., Verhaeghe, S., Decoene, E., De Baere, S., Vandendorpe, B., Van Hecke, A. Factors influencing the process of medication (non-)adherence and (non-)persistence in breast cancer patients with adjuvant antihormonal therapy: a qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2017 Mar; 26(2). Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26059246/.

- Tseng, O.L., Spinelli, J.J., Gotay, C.C., Ho, W.Y., McBride, M.L., Dawes, M.G. Aromatase inhibitors are associated with a higher fracture risk than tamoxifen: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2018; 10(4),71-90. Available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1759720X18759291. [CrossRef]

- Amir, E., Seruga, B., Niraula, S., Carlsson, L., Ocaña, A. (2011) Toxicity of adjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011; 103(17),1299-309. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jnci/article/103/17/1299/2516517?login=true.

- Al-Farhat, Y. Detecting bone density in early breast cancer survivors: The arm-DXA method. Annals of Oncology 2018; 29(8), VIII84. Available from: https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(19)48688-2/fulltext.

- Ahmed, S., Banerjee, S., Horsnell, J. (2023) The management of bone health in breast cancer patients on aromatase inhibitors. European Journal of Surgical Oncology 2023; 49(5), 238. Available from: https://www.ejso.com/article/S0748-7983(23)00258-5/fulltext.

- Xu, J., Cao, B., Li, C., Li, G. The recent progress of endocrine therapy induced osteoporosis in estrogen-positive breast cancer therapy. Frontiers in Oncology 2023; 13, 1218206.Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10361726/.

- Gallagher J.C., Tella S.H. Controversies in osteoporosis management: antiresorptive therapy for preventing bone loss: when to use one or two antiresorptive agents? Clin Obstet Gynecol 2013; 56(4), 749-56. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4140184/.

- Matza, L.S., Park, J., Coyne, K.S., Skinner, E.P., Malley, K.G., Wolever ,R.Q. “Derivation and validation of the ASK-12 adherence barrier survey. Ann Pharmacother 2009; 43(10), 1621-1630. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19776298/.

- Naqvi, A.A, Hassali, M.A., Jahangir, A., Nadir, M.N, Kachela, B. Translation and validation of the English version of the general medication adherence scale (GMAS) in patients with chronic illnesses. J Drug Assess 2019; 8(1), 36-42. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33719815/.

- Brett, J., Hulbert-Williams, N.J., Fenlon, D., Boulton, M., Walter, F.M., Donnelly, P., Lavery, B., Morgan, A., Morris, C., Horne, R., Watson, E. Psychometric properties of the Beliefs about Medicine Questionnaire-adjuvant endocrine therapy (BMQ-AET) for women taking AETs following early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychol Open 2017; 4(2), 2055102917740469. [online]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29379627/.

- DATAtab: Online Statistics Calculator. DATAtab e.U. Graz, Austria. Available from: https://datatab.net.

- Lee, H.S., Lee, J.Y., Ah, Y.M., Kim, H.S., Im, S.A., Noh, D.Y., Lee, B.K. Low adherence to upfront and extended adjuvant letrozole therapy among early breast cancer patients in a clinical practice setting. Oncology 2014; 86(5-6),340-349. Available from: https://karger.com/ocl/article/86/56/340/238958/Low-Adherence-to-Upfront-and-Extended-Adjuvant.

- Beryl, L.L., Rendle, K.A.S., Halley, M.C., Gillespie, K.A., May, S.G., Glover, J., Yu, P., Chattopadhyay, R., Frosch, D.L. Mapping the Decision-Making Process for Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy for Breast Cancer: The Role of Decisional Resolve. Medical Decision Making 2017; 37(1),79-90. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0272989X16640488.

- Breast Cancer Research UK [internet]. Breast cancer risk. 2025 [cited 2025 January 2]. Available from: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancerstatistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/breast-cancer/risk-factors.

- Woolpert, K.M., Schmidt, J.A., Ahern, T.P., Hjorth, C.F., Farkas, D.K., Ejlertsen, B., Collin, L.J., Lash, T.L., Cronin-Fenton, D.P. Clinical factors associated with patterns of endocrine therapy adherence in premenopausal breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Research 2024; 26(1), 59. Available from: https://breast-cancer-research.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13058-024-01819-4.

- Brito, C., Portela, M.C., de Vasconcellos, M.T. Adherence to hormone therapy among women with breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2014; 14,397. Available from: https://bmccancer.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2407-14-397.

- Unni, E., Shiyanbola, O.O., Farris, K.B. Change in Medication Adherence and Beliefs in Medicines Over Time in Older Adults. Global Journal of Health Science 2015 Aug 31; 8(5),39-47. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4877212/.

- Office for National Statistics. How qualification levels across England and Wales differ by country of birth [internet].2023 [cited 2025 January 2]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/educationandchildcare/articles/howqualificationlevelsacrossenglandandwalesdifferbycountryofbirth/2023-05-15.

- Karlsen, R. V., Høeg, B.L., Dalton, S.O., Saltbæk, L., Dehlendorff, C., Johansen, C., Svendsen, M.N., Bidstrup, P.E. Are education and cohabitation associated with health-related quality of life and self-management during breast cancer follow-up? A longitudinal study. Acta Oncologica 2023; 62(4),407–413. Available from: https://medicaljournalssweden.se/actaoncologica/article/view/34998.

- Brito, C., Portela, M.C., Vasconcellos, M.T. Factors associated to persistence with hormonal therapy in women with breast cancer. Revista de Saude Publica 2014; 48(2),284-95. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4206152/.

- Spencer, J.C., Reeve, B.B., Troester, M.A., Wheeler, S.B. Factors Associated with Endocrine Therapy Non-Adherence in Breast Cancer Survivors. Psychooncology 2020; 29(4), 647-654. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7190446/.

- Bertaut, A., Badovinac Crnjevic, T., Martin, A-L, Gaudin, C., Chen, L. 346P Quality of life (QoL) and toxicity in patients (pts) with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative early breast cancer (HR+, HER2– eBC) treated with adjuvant (adj) endocrine therapy (ET) in the CANcer TOxicities (CANTO) study. Annals of Oncology 2023; 34, S320 - S321. Available from: https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(23)01912-9/fulltext.

- Jing, F., Zhu, Z., Qiu, J., Tang, L., Xu, L., Xing, W., Hu, Y. Contemporaneous symptom networks and correlates during endocrine therapy among breast cancer patients: A network analysis. Frontiers in Oncology 2023; 13, 1081786. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10103712/.

- Sella, T., Poorvu, P.D., Ruddy, K.J., Gelber, S.I., Tamimi, R.M., Peppercorn, J.M., Schapira, L., Borges, V.F., Come, S.E., Partridge, A.H., Rosenberg, S.M. Impact of fertility concerns on endocrine therapy decisions in young breast cancer survivors. Cancer 2021; 127(16), 2888-2894. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8351455/.

- Winstead, E. (2023) Pausing Long-Term Breast Cancer Therapy to Become Pregnant Appears to Be Safe. Cancer Currents Blog. [internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 January 2] Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2023/pausing-breastcancer-treatment-to-conceive.

- Partridge, A.H., Nima, S.M., Ruggeri, M., Peccatori, F.A., Azim, Colleoni M., Saura, C., Shimizu, C., Sætersdal, A.B., Kroep, J.R., Mailliez, A., Warner, E., Borges., Amant, F., Gombos, A., Kataoka, A., Rousset-Jablonski, C., Borstnar, S., Takei, J., Lee, J.E, Walshe, J.M., Ruíz-Borrego ,M., Moore, H.C.F., Saunders, C., Bjelic-Radisic, V., Susnjar, S., Cardoso, F., Smith, K.L., Ferreiro, T., Ribi, K., Ruddy, K., Kammler, R., El-Abed, S., Viale, G., Piccart ,M., Korde, L.A., Goldhirsch, A., Gelber, R.D., Pagani, O. Interrupting Endocrine Therapy to Attempt Pregnancy after Breast Cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine 2023; 388(18),1645-1656. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2212856.

- Jimmy, B., Jose, J. Patient medication adherence: measures in daily practice. Oman Medical Journal 2011; 26(3),155-9. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3191684/.

- Haskins, C.B., McDowell, B.D., Carnahan, R.M., Fiedorowicz, J.G., Wallace, R.B., Smith, B.J., Chrischilles, E.A. Breast cancer endocrine therapy adherence in health professional shortage areas: Unique effects on patients with mental illness. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2021; 140, 110294. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022399920308564.

- Sharma, A., Jasrotia, S., Kumar, A. Effects of Chemotherapy on the Immune System: Implications for Cancer Treatment and Patient Outcomes. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacology 2024; 397, 2551–2566. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00210-023-02781-2.

- Hung, W., Chow, S. Optimizing Medication Use in Older Adults. Clinical Therapeutics 2020; 42(4), 556-558. Available from: https://www.clinicaltherapeutics.com/article/S0149-2918(20)30126-0/fulltext.

- Salter, C., McDaid, L., Bhattacharya, D., Holland, R., Marshall, T., Howe, A. Abandoned acid? Understanding adherence to bisphosphonate medications for the prevention of osteoporosis among older women: a qualitative longitudinal study. PLoS One 2014; 9(1), e83552.Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3879247/.

- Sipos, M., Farcas, A., Prodan, N., Mogosan, C. Relationship between beliefs about medicines and adherence in elderly patients with cardiovascular and respiratory diseases: A cross-sectional study in Romania. Patient Education and Counselling 2021; 104(4), 911-918. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0738399120304766.

- Al-Qerem, W., Jarab, A.S., Badinjki, M., Hyassat, D., Qarqaz, R. Exploring variables associated with medication non-adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS One 2021; 16(8), e0256666. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8382191/.

- Ozumba, L.N., Dienye, P., Ndukwu, G. Role of Illness Perception and Medication Beliefs in Medication Adherence among Hypertensive Patients. The Anatolian Journal of Family Medicine 2023; 6(1),31-36. Available from: https://jag.journalagent.com/ajfamed/pdfs/ANATOLJFM_6_1_31_36.pdf.

- Al Bawab, A.Q., Al-Qerem, W., Abusara, O., Alkhatib, N., Mansour, M., Horne, R. What Are the Factors Associated with Nonadherence to Medications in Patients with Chronic Diseases? Healthcare (Basel) 2021; 9(9), 1237. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8469667/.

- Rathbone, A.P., Jamie, K., Todd, A., Husband, A. (A qualitative study exploring the lived experience of medication use in different disease states: Linking experiences of disease symptoms to medication adherence. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 2021; 46(2), 352-362. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jcpt.13288.

- Świątoniowska-Lonc, N., Polański, J., Mazur, G., Jankowska-Polańska, B. Impact of Beliefs about Medicines on the Level of Intentional Non-Adherence to the Recommendations of Elderly Patients with Hypertension. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021; 18(6), 2825. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7998243/.

- Marasine, N.R., Sankhi, S. Factors Associated with Antidepressant Medication Non-adherence. Turkish Journal of Pharmaceutical Science 2021; 18(2), 242-249. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8100773/.

- Cinar, F.I., Mumcu, Ş., Kiliç, B., Polat, Ü., Bal Özkaptan, B. Assessment of Medication Adherence and Related Factors in Hypertensive Patients: The Role of Beliefs About Medicines. Clinical Nursing Research 2021; 30(7),985-993. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1054773820981381.

- Kim, S.H., Cho, Y.U., Kim, S.J., Han, M.S. Changes in Bone Mineral Density in Women With Breast Cancer: A Prospective Cohort Study. Cancer Nursing 2019; 42(2), 164-172. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/cancernursingonline/fulltext/2019/03000/changes_in_bone_mineral_density_in_women_with.9.aspx.

- Malik, L. (The dilemmas of breast cancer treatment and increased fracture risk. Annals of Oncology, 2014;25(8), 1664. Available from: https://www.annalsofoncology.org/article/S0923-7534(19)34831-8/fulltext.

- Rachner, T.D., Coleman, R., Hadji, P., Hofbauer, L.C. Bone health during endocrine therapy for cancer. Lancets Diabetes & Endocrinology 2018; 6(11), 901-910. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2213858718300470.

- Bouvard, B., Soulié, P., Hoppé, E., Georgin-Mege, M., Royer, M., Mesgouez-Nebout, N., Lassalle, C., Cellier, P., Jadaud, E., Abadie-Lacourtoisie, S., Tuchais, C., VinchonPetit, S., Audran, M., Chappard, D., Legrand, E. Fracture incidence after 3 years of aromatase inhibitor therapy. Annals of Oncology 2014; 25(4),843-847. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S092375341936497X.

- Smajic, E., Avdic, D., Pasic, A., Prcic, A., Stancic, M. Mixed Methodology of Scientific Research in Healthcare. Acta Informatica Medica 2022; 30(1), 57-60. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9226784/.

- Greenlaw, C., Brown-Welty, S. A Comparison of Web-Based and Paper-Based Survey Methods. Evaluation Review 2009; 33(5),464-80. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/26674054_A_Comparison_of_Web-Based_and_Paper-Based_Survey_Methods_Testing_Assumptions_of_Survey_Mode_and_Response_Cost.

- Lee, A.Y., Lyons, A.T., Makris, V., Kamaraju, S., Stolley, M.R., Neuner, J.M., Flynn, K.E. Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer: a qualitative exploration of attribution of symptoms among post-menopausal women. Support Care Cancer 2024; 32(4):265. Available from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00520-024-08463-w.

- Chalela, P., Munoz, E., Inupakutika, D., Kaghyan, S., Akopian, D., Kaklamani, V., Lathrop, K., Ramirez A. Improving adherence to endocrine hormonal therapy among breast cancer patients: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Contempory Clinical Trials Communications 2018; 12,109-115. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2451865418300784.

- Wu M-J., Zhao K., Fils-Aime F. Response rates of online surveys in published research: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior Reports 2022 May 5;7, 100206. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2451958822000409.

- Gumpili, S.P., Das, A.V. Sample size and its evolution in research. IHOPE Journal of Ophthalmology 2022; 1(1), 9-13. Available from: https://ihopejournalofophthalmology.com/sample-size-and-its-evolution-in-research/.

- Jimenez, K., Vargas, C., Garcia, K., Guzman, H., Angulo, M., Billimek, J. Evaluating the Validity and Reliability of the Beliefs About Medicines Questionnaire in Low-Income, Spanish-Speaking Patients With Diabetes in the United States. Diabetes Education 2017; 43(1), 114-124. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5899517/.

- Harland, N., Holey, E. Including open-ended questions in quantitative questionnaires—theory and practice. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation 2013; 18(9). Available from: https://www.magonlinelibrary.com/doi/full/10.12968/ijtr.2011.18.9.482.

- Singer, E., Couper, M.P. Some Methodological Uses of Responses to Open Questions and Other Verbatim Comments in Quantitative Surveys. Methods, Data, Analyses 2017; 11(2),20. Available from: https://d-nb.info/1192141725/34.

- Riegel B. I Forgot: Memory and Medication Adherence in Heart Failure. Circulation. Heart Failure 2016; 9(12). Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.116.003642.

- Glick, I., Zamora, D., Davis, J.M., Suryadevara, U., Goldenson, A., Kamis, D. Are Patients With Schizophrenia Better Off With Lifetime Antipsychotic Medication?: Replication of a Naturalistic, Long-Term, Follow-Up Study of Antipsychotic Treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2020; 40(2),145-148. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/psychopharmacology/abstract/2020/03000/are_patients_with_schizophrenia_better_off_with.7.aspx.

- Wright, F., Malone, S.K., Wong, A., D’Eramo Melkus, G., Dickson, V.V. Addressing Challenges in Recruiting Diverse Populations for Research: Practical Experience From a P20 Center. Nursing Research 2022; 71(3), 218-226. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9038626/.

- Andrade, C. Sample Size and its Importance in Research. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 2020; 42(1), 102-103. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6970301/.

- Guyot, M., Pelgrims, I., Aerts, R., Keune, H., Remmen, R., De Clercq, E.M., Thomas, I., Vanwambeke, S.O. Non-response bias in the analysis of the association between mental health and the urban environment: a cross-sectional study in Brussels, Belgium. Archives of Public Health 2023; 81(1), 129.Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10327324/ [Accessed 30 December 2024].

- Curtis, S. and Rees Jones, I. Is There a Place for Geography in the Analysis of Health Inequality? Sociology of Health & Illness 1998; 20, 645672. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/1467-9566.00123.

- Cabral, A.C., Moura-Ramos, M., Castel-Branco, M., Caramona, M., Fernandez-Llimos, F., Figueiredo, I.V. Influence of the mode of administration on the results of medication adherence questionnaires. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 2017; 23(6), 1252-1257. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/jep.12773.

- Lechner, C.M., Partsch, M.V., Danner, D., Rammstedt, B. (2019) Individual, situational, and cultural correlates of acquiescent responding: Towards a unified conceptual framework. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology 2019; 72(3),426-446. Available from: https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bmsp.12164.

- Adams-Quackenbush, N.M., Horselenberg, R., Hubert, J., Vrij, A., van Koppen, P. Interview expectancies: awareness of potential biases influences behaviour in interviewees. Psychiatry, Psychology Law and Law 2019; 26(1), 150-166. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6762119/.

- Jindal, T., Sinha, R.K., Mukherjee, S., Mandal, S.N., Karmakar, D. Misinterpretation of the international prostate symptom score questionnaire by Indian patients. Indian Journal of Urology 2014; 30(3), 252-5. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/indianjurol/fulltext/2014/30030/misinterpretation_of_th e_international_prostate.4.aspx.

- Kusmaryono, I., Wijayanti, D., Maharani, H.R. Number of Response Options, Reliability, Validity, and Potential Bias in the Use of the Likert Scale Education and Social Science Research: A Literature Review. International Journal of Educational Methodology 2022; 8(4), 625-637. Available from: https://pdf.ijem.com/IJEM_8_4_625.pdf.

- Zulman, D.M, Slightam, C.A., Brandt, K., Lewis, E.T., Asch, S.M., Shaw, J.G. “They are interrelated, one feeds off the other”: A taxonomy of perceived disease interactions derived from patients with multiple chronic conditions. Patient Education and Counselling 2020; 103(5), 1027-1032. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0738399119305270.

- Sun, X., Briel, M., Busse, J.W., You, J.J., Akl, E.A., Mejza, F., Bala, M.M., Bassler, D., Mertz, D., Diaz-Granados, N., Vandvik, P.O., Malaga, G., Srinathan, S.K., Dahm, P., Johnston, B.C., Alonso-Coello, P., Hassouneh, B., Truong, J., Dattani, N.D., Walter, S.D., Heels-Ansdell, D., Bhatnagar, N., Altman, D.G., Guyatt, G.H. The influence of study characteristics on reporting of subgroup analyses in randomised controlled trials: systematic review. BMJ 2011; 342, d1569. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/342/bmj.d1569.

- Thomson, P., Rushworth, G.F., Andreis, F., Angus, N.J., Mohan, A.R., Leslie, S.J. Longitudinal study of the relationship between patients’ medication adherence and quality of life outcomes and illness perceptions and beliefs about cardiac rehabilitation. BMC Cardiovasc Disorders 2020; 20(1),71. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7011382/.

- Luong, G., Charles, S.T., Rook, K.S., Reynolds, C.A., Gatz, M. Age differences and longitudinal change in the effects of data collection mode on self-reports of psychosocial functioning. Psychol Aging 2015; 30(1), 106-119. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4362730/.

| n | Mean | Median | Standard deviation | ||

| BMQ-AET SPECIFIC NECESSITY SCORE NON-ADHERENT | 13 | 17.54 | 18 | 3.15 | |

| BMQ-AET SPECIFIC NECESSITY SCORE ADHERENT | 143 | 10.86 | 10 | 3.13 |

| n | Mean | Median | Standard deviation | ||

| BMQ-AET SPECIFIC CONCERNS SCORE NON-ADHERENT | 13 | 13 | 13 | 2.68 | |

| BMQ-AET SPECIFIC CONCERNS SCORE ADHERENT | 143 | 16.54 | 17 | 4.24 |

| U | z | asymptotic p | exact p | r | |

| 452.5 | -3.07 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).