1. Introduction

In recent years, novel oral anticancer therapies have greatly improved the survival of patients with solid tumors, including breast cancer (BC) [

1]. Achieving and maintaining adequate adherence rates to these treatments is pivotal to obtaining optimal anticancer activity, eventually hesitating in favorable clinical outcomes [

2]. Adherence is a complex multifactorial issue, and its optimization may be challenged by side effects, schedule complexity, and emotional and psychological factors, including the patient’s motivation, understanding of the disease, and support system [

3,

4].

The issue of compliance to oral agents in BC is not new, and adherence to oral hormonal therapy (HT) in hormone-positive (HR+)/ human epidermal growth factor 2 negative (HER2-) BC patients may be lower than expected or perceived by prescribers due to a variety of barriers [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Regular HT intake is essential for achieving the best possible outcomes in terms of disease control since it prevents cancer from progressing by continuously inhibiting the targeted enzymes [

8]. However, HT represents a long-term commitment for patients who often experience side effects and impaired quality of life [

6]. Two systematic literature reviews of behavioral and educational interventions to improve HT adherence reported no significant improvements compared to usual care [

10,

11]. Authors reported variability in terminology and definitions of adherence to medication, which may hinder biases and render difficult comparisons among different studies.

Lately, the addition of a cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor (CDK4/6i) (i.e., palbociclib, ribociclib or abemaciclib) to HT became the standard of care for HR+/HER2- metastatic BC patients, and two of these agents (ribociclib and abemaciclib) also showed efficacy in the adjuvant setting [

1,

12,

13,

14]. Among CDK4/6i, abemaciclib (ABE) is particularly active in metastatic endocrine-resistant patients and achieved an invasive disease-free survival advantage in the adjuvant treatment of high-risk hormone-sensitive BC [

12,

14,

15,

16].

However, treatment with ABE may induce significant gastrointestinal side effects, mainly diarrhea and fatigue, which may interfere with treatment adherence [

17]. Several strategies can be adopted to improve compliance with this agent, including proactive side-effects management, patients’ and caregivers’ education, simplifying oral polypharmacy, or support systems implementation through healthcare providers, family, or external groups [

18,

19]. Still, limited data about compliance to CDK4/6i, including ABE, is available in real-world scenarios.

Here, we report a retrospective multicentric analysis of treatment adherence in a real-life series of patients receiving ABE plus HT for HR+/HER2- BC.

2. Materials and Methods

Study design. This non-interventional, retrospective analysis was conducted at five medical oncology units, one academic hospital, two cancer centers, and two general hospitals. Due to the study’s non-interventional, retrospective nature and the use of fully anonymized data, informed consent was waived.

Data sources. According to Italian regulation, novel anticancer agents subjected to monitoring by the Italian Medicine Agency (Agenzia Italiana per il Farmaco, AIFA) must be prescribed via a web-based application [

20]. This platform allows the production of three-weekly or monthly drug claims, recording prescription dates, patients’ characteristics, drug dose (including potential dose reductions), toxicity, laboratory tests, and clinical response. Drug claims are e-referred to the pharmacy every four weeks before drug shortage to avoid treatment interruptions. Previous prescription discharge on the electronic platform is a prerequisite for giving the green light to the new one. Toxicities leading to drug dose reductions are electronically reported to the regional pharmacovigilance office. At all-time prescriptions, medical oncologists send drug claims electronically to the nearest public community pharmacy. Public community pharmacies are organized according to a hub and spoke model on a geographical basis. A central pharmacy acts as a hub coordinating all the spoke offices. Public community pharmacists verify the appropriateness of prescriptions and send drugs to the patient’s address. This e-referral system was implemented by the local government’s public health system of the Pharmacy Service to avoid gatherings during the COVID-19 epidemic.

Adherence measurement. There is no universally standardized method for measuring medication adherence. The Pharmacy Quality Alliance is a standard set of measures to assess pharmacy performance using administrative claims data to calculate measure rates such as medication possession ratio (MPR) and proportion of days covered (PDC), two validated measures of adherence based on the percentage of days the patient has medication available, which, when used together, reduce the risk of adherence overestimation [

21]. PDC is the leading method for calculating medication adherence using prescription refill data from electronic records at the population level. It is defined as the proportion of days in the treatment period “covered” by prescription claims for the same medication or another in its therapeutic category. The PDC formula is (Number of days in the period covered)/ (Number of days in period) x 100. The level of PDC above which the medication is reasonably likely to achieve most of the potential clinical benefit (threshold of 80%) for many chronic conditions. Adherence was calculated and reported over a fixed 12-month treatment period, ranging from treatment initiation as per first drug claim. A score of 0.8 (i.e., 80% adherence rate) was the cutoff to classify the patients as adherent (0.8 ≤ PDC ≤1) or non-adherent (0 ≤ PDC <0.8). The duration of follow-up was defined as the time in months from the first prescription issued by the pharmacist in the community pharmacy to the last prescription registered and the date of treatment discontinuation for any reason, including progressive disease, death, severe toxicity, or loss of follow-up. As previously described [

22,

23]. This measure without stratification requires a minimum denominator of 30 for reliability. If the minimum denominator size is met, the measure should not be used for performance measurement, including in accountability programs. Reliability testing conducted on the MS Medicare data as a ratio of signal-to-noise using the Adams beta-binomial reliability methodology showed the measure was reliable, with a mean reliability score of 0.70 [

24]. To evaluate the potential impact of dose modifications on outcomes, authors calculated the relative dose intensity (RDI), which considers drug interruptions and dose reduction over time. For the RDI calculation, the standard starting dose was set according to approved labels, i.e., abemaciclib 150 mg twice daily in combination with either letrozole or fulvestrant. Dose intensity was calculated using the Hryniuk and Busch methods [

25,

26]. The RDI formula is (total dose over the study period)/ (standard total dose over the study period) x 100.

Statistics. The patient’s clinical characteristics were reported as absolute numbers and relative rates with a 95% confidence interval as needed. Correlation statistical analysis and graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism 10.1 (GraphPad Software Boston, USA), with two-tailed statistical significance levels set at p less than 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Population

The study covered a period from 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2022. The analysis included 100 patients treated with ABE plus an aromatase inhibitor (AI) or fulvestrant for advanced BC or plus an AI as adjuvant postoperative therapy.

Table 1 summarizes descriptive statistics of patient characteristics and adherence for each group of patients. Eligible patients had a median (range) age of 66 (30–90) years. Most patients (97%) had a 0-1 performance status according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale. 63 patients (63%) received ABE with letrozole, and 27 (27%) received fulvestrant. Nine of the 100 patients were treated early, and the remaining 91 were in the advanced stage. In this setting, 23%, 18%, and 50% of patients had bone-only, visceral, or soft tissue disease, respectively. Before ABE prescription most patients were carefully screened drug-drug interactions and for the presence of clinical characteristics predictive for severe diarrhea such as inflammatory colorectal diseases, previous abdominal radiotherapy, colitis, diverticulosis, and polypharmacy [

27]. Eighty-four patients started a full dose therapy of 150 mg b.i.d., while 16 patients started at 100 mg/m2 b.i.d. due to treating physician decision of pursuing a dose escalation strategy to prevent side-effects [

28]. Polypharmacy, defined as > 5 different medications taken for other than cancer-related disease, was recorded in 34 patients (34%).

3.2. Side-Effects

Table 2 shows side-effects. Grade 3 or prolonged grade 2 diarrhea was recorded in 35% of cases being the most frequent reason for dose reduction or treatment delay. Once treated adequately no case of permanent toxicity-driven ABE withdrawal was recorded. Time-trend analysis of side effects showed that diarrhea was most frequent during the first two months of therapy and subsequently its incidence dropped down to 3%. Grade 2-3 fatigue and anorexia emerged later and were reported in 21% and 16% of cases. Leukopenia was generally mild to moderate (grade 1-2), with reversible grade 3 events in 11% of cases. Thrombocytopenia was mild with 15 patients (15%) reporting grade 1-2 toxicity. Grade 2 and 3 anemia was reported in 21 (21%) and 2 (2%) patients respectively. No dose reduction was reported in patients starting with 100 mg b.i.d., even in those patients (n. 6) who escalated dosage to 150 mg b.i.d. On the other hand, 21 patients (21%) treated with a starting dose of 150 mg b.i.d. required dose reduction to 100 mg b.i.d. and 3 of them to 50 mg b.i.d. Forty patients (40%) experienced some treatment delay, mostly for side-effects (26%) or intercurrent non cancer related illnesses (7%), and in 7 cases (7%) for claims delays due to organizational dysfunction.

3.3. Adherence Rate

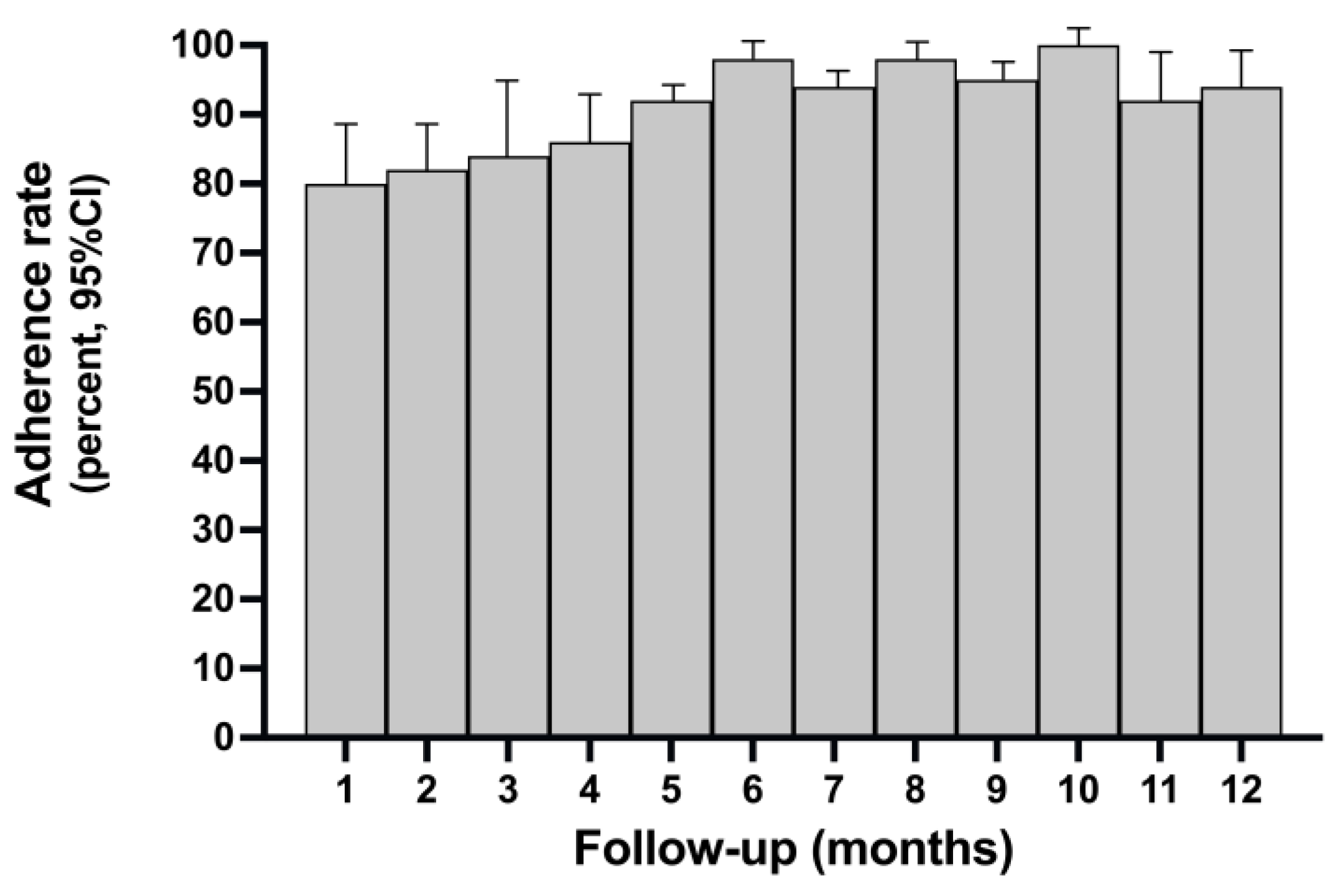

As shown in

Table 2, the global adherence rate according to PDC formula was 92.25% + 1.939 (SD), while the proportion of non-adherent patients with PDC <0.8 was 12.5% (95% CI 6.2 to 20.9%).

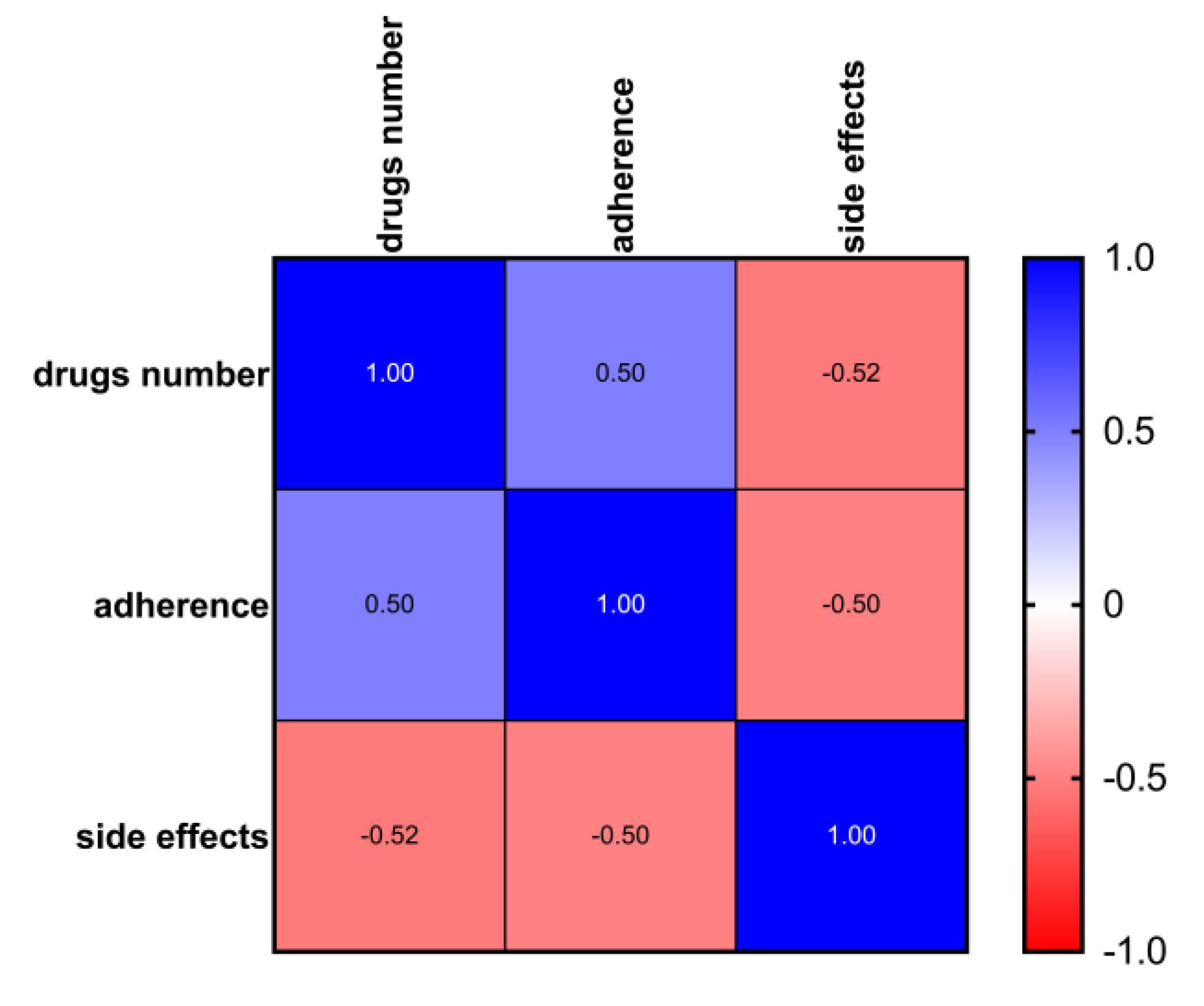

Figure 1 shows the time trend of adherence rate during the prefixed follow-up time. Adherence was lower in the first 1-5 months while increased in the subsequent phases of follow-up. As shown in

Figure 2, among patients treated with ABE, there was a significant correlation between the level of adherence, polypharmacy, and side effects (Pearson’s r <= 1). The occurrence of side effects probably negatively influenced adherence in the first three months of treatment as inferred from the time trend of adherence, which shows lower adherence in the first three months of ABE followed by an increase after dose reduction per protocol, better management of side-effects and progress in the learning curve by patients and caregivers.

3.4. Dose-Intensity

As shown in

Table 2. The programmed dose intensity as per protocol was 2100 mg/week (100%) of ABE in patients treated with a starting dose of 150 mg b.i.d., and 1400 mg/week in those who started at the dosage of 100 mg b.i.d. The received mean dose intensity 88.7% (95% CI 81-94; mean 1988 mg/week) in the overall population. The mean received dose intensity was 82% (95% CI 73-89; mean 1968 mg/week) in patients initially treated with full dose ABE of 150 mg b.i.d., while was 96.4% (95% CI 90-99; mean 1350 mg/week) in those patients treated with 100 mg b.i.d.

4. Discussion

Abemaciclib is an orally active inhibitor of CDK4/6 indicated in HR+/HER2- BC patients in combination with an AI or fulvestrant, depending on the clinical setting [

1,

12,

13,

14]. The most common adverse events associated with ABE are gastrointestinal toxicity, mainly diarrhea and fatigue, while cytopenia is less prevalent than with other CDK4/6i [

1,

12,

13,

14]. As per other oral treatments, ABE non-adherence and high inter-individual pharmacokinetic variability can influence response rates in metastatic settings. Adherence is even more critical in patients with surgically excised B, [

13]. Adequate patient evaluation, education, and proactive management of potential side events are crucial for optimizing adherence and dose intensity [

28]. These efforts represent a significant workload for oncologists dealing with BC. Therefore, insights into rates and barriers to adherence are paramount in clinical practice, considering the ever-increasing number of patients with access to ABE in the future [

29].

Precise and reliable monitoring of adherence to antineoplastic drugs is challenging since different methods exist, and many of them are only partly applicable to routine clinical practice [

30,

31,

32]. Individualized therapeutic drug monitoring, plasma concentration measurement of drug metabolites, and electronic registration of daily drug assumptions have been used to monitor adherence and, potentially, individualized treatment dosing [

32].

We reported the results of a retrospective analysis on 100 women treated with ABE plus AI of fulvestrant. We found a high adherence rate with a relatively low non-adherence proportion. The time trend of adherence in the 12 months of observation shows lower adherence in the first 2-3 months of therapy with an increase in the following months, suggesting that side effects might have a significant influence, and the ensuing dose-reduction or better management may explain the improvement of adherence with time. Overall, there was no correlation between adherence and menopausal status, socioeconomical level, comedication with AI or fulvestrant, or clinic-pathological setting, such as dominant disease. The presence of a caregiver was not correlated, but almost all the women included had a caregiver, impairing statistical analysis. On the other hand, there was a significant correlation between side effects and polypharmacy, the latter probably reflecting concomitant non-oncological diseases [

33,

34]. The data aligns with those above, as reported by other authors, confirming the high adherence rate to ABE-based oral regimens.

There are few scientific reports about adherence to ABE in the medical literature. Smyth et al. conducted a retrospective real-world study that analyzed medical, and pharmacy claims for patients over three years [

35]. This analysis included 454 patients with a 350-day follow-up who received ABE plus IA or fulvestrant, mainly for advanced stage disease. One-quarter of patients received previous chemotherapy, and nearly half had received another CDK4/6i. Overall, 55% of patients had visceral metastases, including one-third with liver disease. Researchers reported an adherence rate of 88.7% for ABE as determined by MDP.

Turcu et al. correlated adherence to CDK4/6i in 330 patients with advanced BC to age, gender, and follow-up duration [

36]. The average follow-up period was 14.6 ± 12.5, 10.6 ± 7.1, and 8.6 ± 6.4 months for palbociclib, ribociclib, and ABE, respectively. Non-adherence rates by PDC were 12.8% with palbociclib, 14.6% with ribociclib and 14.7% with ABE. Overall, there was no significant correlation between adherence, age, or gender. However, a significant correlation was found with follow-up length. However, the relatively high adherence rate was calculated only on an 8-month interval, and essential information on side effects leading to treatment discontinuation was incomplete.

A Canadian retrospective study on 65 patients reported the benefits of a patient-centered pharmacy practice according to American Society of Clinical Oncology/National Community Oncology Dispensing Association standards and described its impact on CDK4/6i treatment use in locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer [

28]. Such an approach ensures timely refills and strict monitoring and allows patients to achieve high adherence and persistence rates fitting in the range reported in clinical trials. The mean PDC was 89.6%. However, only 14 patients received ABE. The treatment interruption rates were similar for palbociclib (63%) and ABE (64%). In the first three treatment cycles, 16% of patients treated with palbociclib had at least one dose reduction compared to 43% of patients treated with ABE. During the study period, 33% and 71% of patients had a dose reduction with palbociclib and ABE, respectively. Overall, the median time-to-treatment discontinuation was estimated at 44.2 months in women treated with CDK4/6i + letrozole and 17.0 months in those treated with CDK4/6i + fulvestrant. The mean RDI was 85%, and the benefits of treatment were maintained regardless of the RDI levels.

Identification of potential barriers to adherence represents another critical issue. Stephenson et al. conducted a qualitative study to describe challenges and obstacles to adherence and persistence to CDK4/6i in 24 patients with advanced BC using a drug claim database over two years [

37]. Most patients reported a positive feeling concerning the ease of home administration and the ability to cope with potential side effects. A strong positive relationship with the managing oncologist and trust in expected benefits were among the significant factors contributing to adherence and persistence. A multifactorial intervention, including accurate patient education, evidence-based strategies for symptom management, and ease of communication with providers, may contribute to ensuring adherence. US investigators conducted a qualitative analysis to identify barriers and facilitators to adherence to CDK4/6i [

38,

39]. Barriers to adherence included knowledge of efficacy, side effects, and benefit perception of CDK4/6i. Adequate communication with the healthcare team and caregiver support were also significant determinants of adherence. Financial issues were less frequent but of great concern. Recently Goetz et al. reported the impact of dose reductions on adjuvant abemaciclib efficacy for patients with high-risk early breast cancer [

39] showing that proper management of toxicity and drug reduction as per protocol do not affect efficacy. Japanese investigators reported that low baseline weight (< 54 kg), bone metastases, and hemoglobin level ≤ 12.4 g/dL were independent predictors of abemaciclib discontinuation for any reason and that gastrointestinal side effects were the main reason for discontinuation [

40].

Our work has some limitations. Measurement of adherence by PDC may not be entirely reliable, as already stated in medical literature since there is no definitive evidence that patients are taking oral medication. Second, the data reported came from a group of investigators working in high-volume centers who are highly experienced in managing patients treated with CDK4/6i. Therefore, adherence and dose-intensity data may be optimistic compared to centers with lower experience. Third, the patient sample size may not reflect the reality in all settings, even if data mirrors real-life practice.

5. Conclusions

Medical oncologists’ primary concerns regarding oral anti-cancer agent prescription should be related to difficulties related to patient understanding and adherence to recommended regimens [

41,

42]. Precision medicine, which focuses on treating each patient according to the biological features of their disease, has become increasingly prevalent in oncology. Similarly, oncologists can improve precision treatment by identifying traits, preferences, and needs specific to each patient in the context of oral anticancer medications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, FM, MRV and GS; methodology, V.G. and D.S.; investigation, MRV, MVS, FM, DS, GM, LM, GP, and VG; writing—original draft preparation, VG, DS, and GS.; writing—review and editing, FM and VG; funding acquisition, MRV. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding is provided by the University of Palermo, Italy.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This retrospective chart review study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Kore University of Enna, Italy (Protocol n. 21538, October 26, 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to complete anonymization of identification personal data.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and legal aspects.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank dr. Santa Irene Polito for her technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

MRV, VG, FM, and MVS received honoraria from Eli Lilly as speakers. The other authors have not disclosed any competing interests. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABE |

Abemaciclib |

| CDK4/6i |

cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors |

| AI |

Aromatase inhibitor |

| RDI |

Received dose-intensity |

References

- Zhao, M.; Hanson, K.A.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, A.; Cha-Silva, A.S. Place in Therapy of Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4/6 Inhibitors in Breast Cancer: A Targeted Literature Review. Targeted Oncol. 2023, 18, 327–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Martorana, F.; Sanò, M.V.; Valerio, M.R.; Fogli, S.; Vigneri, P.; Danesi, R.; Gebbia, V. Abemaciclib pharmacology and interactions in the treatment of HR+/HER2- breast cancer: A critical review. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2024, 15, 20420986231224214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebbia, V.; Piazza, D.; Valerio, M.R. Harmful Interference of Detoxifying Diets and Nutraceuticals with Adherence to Abemaciclib in Advanced Estrogen Receptor-Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-2-Negative Breast Cancer: A Case Report. Case Rep. Oncol. 2021, 14, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, A.H.; Wang, P.S.; Winer, E.P.; Avorn, J. Nonadherence to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in women with primary breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chlebowski, R.T.; Geller, M.L. Adherence to endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Oncology 2006, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardas, P.; Lewek, P.; Matyjaszczyk, M. Determinants of patient adherence: A review of systematic reviews. Front Pharmacol. 2013, 4, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paranjpe, R.; John, G.; Trivedi, M.; Abughosh, S. Identifying adherence barriers to oral endocrine therapy among breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019, 174, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirgwin, J.H.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Coates, A.S.; Price, K.N.; Ejlertsen, B.; Debled, M.; et al. Treatment adherence and its impact on disease-free survival in the breast international group 1-98 trial of tamoxifen and letrozole, alone and in sequence. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 2452–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado-de-Mendoza, A.; Cabling, M.L.; Lobo, T.; Dash, C.; Sheppard, V.B. Behavioral Interventions to Enhance Adherence to Hormone Therapy in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Literature Review. Clin. Breast Cancer 2016, 16, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekinci, E.; Nathoo, S.; Korattyil, T.; Vadhariya, A.; Zaghloul, H.A.; Niravath, P.A.; Abughosh, S.M.; Trivedi, M.V. Interventions to improve endocrine therapy adherence inbreast cancer survivors: What is the evidence? J. Cancer Surviv. 2018, 12, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnant, M.; Singer, C.F.; Rinnerthaler, G.; Pfeiler, G.; Egle, D.F.; Balic, M.; Bartsch, R. Position paper on CDK4/6 inhibitors in early breast cancer. Memo, 2023, 16, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, S.R.D.; Harbeck, N.; Hegg, R.; Toi, M.; Martin, M.; Shao, Z.M.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Martinez Rodriguez, J.L.; Campone, M.; Hamilton, E.; et al. MonarchE Committee Members and Investigators (2020). Abemaciclib Combined With Endocrine Therapy for the Adjuvant Treatment of HR+, HER2-, Node-Positive, High-Risk, Early Breast Cancer (monarchE). J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3987–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurvitz, S.A.; Martin, M.; Press, M.F.; Chan, D.; Fernandez-Abad, M.; Petru, E.; Rostorfer, R.; Guarneri, V.; Huang, C.S.; Barriga, S.; et al. Potent Cell-Cycle Inhibition and Upregulation of Immune Response with Abemaciclib and Anastrozole in neo MONARCH, Phase II Neoadjuvant Study in HR+/HER2- Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 566–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sledge, G.W., Jr; Toi, M.; Neven, P.; Sohn, J.; Inoue, K.; Pivot, X.; Burdaeva, O.; Okera, M.; Masuda, N.; Kaufman, P.A.; et al. MONARCH 2: Abemaciclib in Combination with Fulvestrant in Women With HR+/HER2- Advanced Breast Cancer Who Had Progressed While Receiving Endocrine Therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 2875–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, M.P.; Toi, M.; Huober, J.; Sohn, J.; Trédan, O.; Park, I.H.; Campone, M.; Chen, S.C.; Manso, L.M.; Paluch-Shimon, S.; et al. Abemaciclib plus a nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor as initial therapy for HR+, HER2- advanced breast cancer: Final overall survival results of MONARCH 3. Ann Oncol. 2024, 35, 718–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandiera, C.; Locatelli, I.; Courlet, P.; Cardoso, E.; Zaman, K.; Stravodimou, A.; Dolcan, A.; Sarivalasis, A.; Zurcher, J.P.; Aedo-Lopez, V.; et al. Adherence to the CDK 4/6 Inhibitor Palbociclib and Omission of Dose Management Supported by Pharmacometric Modelling as Part of the OpTAT Study. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugo, H.S.; Huober, J.; García-Sáenz, J.A.; Masuda, N.; Sohn, J.H.; Andre, V.A.M.; Barriga, S.; Cox, J.; Goetz, M. Management of Abemaciclib-Associated Adverse Events in Patients with Hormone Receptor-Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Advanced Breast Cancer: Safety Analysis of MONARCH 2 and MONARCH 3. Oncologist 2021, 26, e53–e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takada, S.; Maeda, H.; Umehara, K.; Kuwahara, S.; Yamamoto, M.; Tomioka, N.; Takahashi, M.; Watanabe, K.; Hashishita, H. Clinical Management of Potential Toxicity of Abemaciclib and Approaches to Ensure Treatment Continuation. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2023, 24, 1955–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIFA https://servizionline.gov.it.

- Kwan, Y.H.; Weng, S.D.; Loh, D.H.F.; Phang, J.K.; Oo, L.J.Y.; Blalock, D.V.; Chew, E.H.; Yap, K.Z.; Tan, C.Y.K.; Yoon, S.; et al. Measurement Properties of Existing Patient-Reported Outcome Measures on Medication Adherence: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, A.L.; Dediu, D. Computation of adherence to medication and visualization of medication histories in R with AdhereR: Towards transparent and reproducible use of electronic healthcare data. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, A.M.; Nau, D.P.; Cramer, J.A.; Benner, J.; Gwadry-Sridhar, F.; Nichol, M.A. Checklist for medication compliance and persistence studies using retrospective databases. Value Health 2007, 10, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams John, L. The Reliability of Provider Profiling: A Tutorial. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2009. https://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR653.html.

- Hryniuk, W.; Bush, H. The importance of dose intensity in chemotherapy of metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin Oncol. 1984, 2, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slejko, J.F.; Rueda, J.D.; Trovato, J.A.; Gorman, E.F.; Betz, G.; Arcona, S.; Zacker, C.; Stuart, B. A Comprehensive Review of Methods to Measure Oral Oncolytic Dose Intensity Using Retrospective Data. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2019, 25, 1125–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebbia, V.; Martorana, F.; Sanò, M.V.; Valerio, M.R.; Giotta, F.; Spada, M.; Piazza, D.; Caruso, M.; Vigneri, P. Abemaciclib-associated Diarrhea: An Exploratory Analysis of Real-life Data. Anticancer Res. 2023, 43, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marineau, A.; St-Pierre, C.; Lessard-Hurtubise, R.; David, M.È.; Adam, J.P.; Chabot, I. Cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor treatment use in women treated for advanced breast cancer: Integrating ASCO/NCODA patient-centered standards in a community pharmacy. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2023, 29, 1144–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannehl, D.; Volmer, L.L.; Weiss, M.; Matovina, S.; Grischke, E.M.; Oberlechner, E.; Seller, A.; Walter, C.B.; Hahn, M.; Engler, T.; et al. Feasibility of Adjuvant Treatment with Abemaciclib-Real-World Data from a Large German Breast Center. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pednekar, P.P.; Ágh, T.; Malmenäs, M.; Raval, A.D.; Bennett, B.M.; Borah, B.J.; Hutchins, D.S.; Manias, E.; Williams, A.F.; Hiligsmann, M.; et al. Methods for Measuring Multiple Medication Adherence: A Systematic Review-Report of the ISPOR Medication Adherence and Persistence Special Interest Group. Value Health 2019, 22, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J.A.; Roy, A.; Burrell, A.; Fairchild, C.J.; Fuldeore, M.J.; Ollendorf, D.A.; Wong, P.K. Medication compliance and persistence: Terminology and definitions. Value in health: The journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research 2008, 11, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espírito-Santo, M.; Santos, S.; Estêvão, M.D. Digital Solutions Available to Be Used by Informal Caregivers, Contributing to Medication Adherence: A Scoping Review. Pharmacy (Basel) 2024, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viktil, K.K.; Blix, H.S.; Moger, T.A.; Reikvam, A. Polypharmacy as commonly defined is an indicator of limited value in the assessment of drug-related problems. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2007, 63, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masnoon, N.; Shakib, S.; Kalisch-Ellett, L.; Caughey, G.E. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, E.N.; Beyrer, J.; Saverno, K.R.; Hadden, E.; Abedtash, H.; DeLuca, A.; Lawrence, G.W.; Rybowski, S. Real-World Patient Characteristics, Utilization Patterns, and Outcomes of US Patients with HR+, HER2- Metastatic Breast Cancer Treated with Abemaciclib. Drugs Real World Outcomes 2022, 9, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcu-Stiolica, A.; Udristoiu, I.; Subtirelu, M.S.; Gheorman, V.; Aldea, M.; Dumitrescu, E.A.; Volovat, S.R.; Median, D.M.; Lungulescu, C.V. Digging in real-word electronic database for assessing CDK 4/6 inhibitors adherence in breast cancer patients from Romania. Front. Pharmacol, 2024, 15, 1345482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, J.J.; Gable, J.C.; Zincavage, R.; Price, G.L.; Churchill, C.; Zhu, E.; Stenger, K.; Singhal, M.; Nepal, B.; Grabner, M. Treatment Experiences with CDK4&6 Inhibitors Among Women with Metastatic Breast Cancer: A Qualitative Study. Patient Prefer. Adher. 2021, 15, 2417–2429. [Google Scholar]

- Conley, C.C.; McIntyre, M.; Pensak, N.A.; Lynce, F.; Graham, D.; Ismail-Khan, R.; Lopez, K.; Vadaparampil, S.T.; O’Neill, S.C. Barriers and facilitators to taking CDK4/6 inhibitors among patients with metastatic breast cancer: A qualitative study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022, 192, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, M.P.; Cicin, I.; Testa, L.; Tolaney, S.M.; Huober, J.; Guarneri, V.; Johnston, S.R.D.; Martin, M.; Rastogi, P.; Harbeck, N.; et al. Impact of dose reductions on adjuvant abemaciclib efficacy for patients with high-risk early breast cancer: Analyses from the monarchE study. NPJ Breast Cancer 2024, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kataoka, N.; Hata, T.; Hosomi, K.; Hirata, A.; Ota, R.; Nishihara, M.; Kimura, K.; Iwamoto, M.; Ashida, A.; Neo, M. Predictors of abemaciclib discontinuation in patients with breast cancer: A multicenter retrospective cohort study. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 133541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring, L.M.; Zangardi, M.L.; Moy, B.; Bardia, A. Clinical Management of Potential Toxicities and Drug Interactions Related to Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4/6 Inhibitors in Breast Cancer: Practical Considerations and Recommendations. The Oncologist 2017, 22, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, T.W. Advances in Oral Oncolytic Agents for Breast Cancer and Recommendations for Promoting Adherence. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2020, 11, 83–96. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).