1. Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common diagnosed disease globally with an estimated 2.26 million cases in 2020 and is the leading cause of cancer mortality among women [

1]. In Italy, it represents the 30% of all malignances [

2]. Mortality reached over 12,500 deaths in 2021, while survival after 5 years from the diagnosis was 88%. In 2022, over 55,700 new cases have been diagnosed (+ 0.5% from 2020) [

3]. Due to combined BC preventive and treatment strategies, overall patients’ survival is now standing at 80% in developed Countries [

4].

Since the most common subset of BC is hormone-receptor positive [

5], many patients receive adjuvant treatments with Tamoxifen or Aromatase Inhibitors (AI) [

6] with or without gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists (depending on premenopausal or post-menopausal tumor onset) [

7]. This adjuvant endocrine therapy results in rapid deterioration of bone mineral density (BMD) and requires immediate prevention strategies [

8].

Poor bone health might result in fractures and other bone-related complications. To manage this issue, several international guidelines describe the proper implementation of treatments and prevention of bone disease in BC patients. An international joint position statement ─published by several interdisciplinary cancer and bone societies─ indicated specific T-score values, together with risk factors, to suggest bone-directed therapy for the duration of AI treatment to prevent fractures [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

The anticancer benefits of adjuvant Bisphosphonates treatment in postmenopausal women are represented by a 34% relative risk reduction in bone metastasis, and a 17% relative risk decrease of BC mortality [

18,

19,

20].

According to Hadji and colleagues, bone-addressed therapy should be administered to all patients with a T-score < −2.0 or a T-score of < –1.5 SD with an additional risk factors (age > 65; smoking; BMI < 20; family history of hip fracture; personal history of fragility fracture > 50 years; oral glucocorticoids use > 6 months) or with ≥ 2 risk factor (without BMD) for the duration of AI treatment [

8]. Patients with T-score > −1.5 SD and no risk factors should be managed according to BMD loss during the first year and local guidelines for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Compliance should be assessed regularly, as should BMD on treatment after 12-24 months. Furthermore, given the decreased incidence of bone recurrence and BC-specific mortality, adjuvant Bisphosphonates is recommended for all postmenopausal women at significant risk of disease recurrence [

8].

In 2020, guidelines from the Italian Association of Medical Oncology (AIOM) [

23] suggested that Bisphosphonates and Denosumab were the drugs of choice in managing bone health in BC patients, as they have been shown to prevent BMD loss after adjuvant hormonal treatment. Direct efficacy against fractures has been demonstrated for Denosumab 60 mg subcutaneous injections administered every 6 months in postmenopausal women on AI therapy [

21,

22]. The AIOM stated that the optimal duration of treatment with Bisphosphonates or Denosumab in these women is not defined; however, it can be recommended to continue therapy at least for the period of treatment with GnRH and/or AI drugs. In a broader perspective, ensuring adequate levels of vitamin D and calcium through diet or supplementation is essential to support antiresorptive bone therapy; the daily calcium requirement for menopausal women is 1500 mg while the average recommended intake of vitamin D is 400-800 IU/day.

Similarly, in 2017 the Italian Drug Agency (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, AIFA) published a document known as “Note 79” stating that primary prevention with bone-modifying agents, such as Bisphosphonates or Denosumab, is necessary in menopausal women at increased risk of fracture following adjuvant hormonal blockade treatment for BC. Intake or supplementation of vitamin D and calcium in the diet is also recommended [

24].

Considering the abovementioned guidelines and clinical trials [

25,

26,

27,

28] supporting the use of Bisphosphonates or Denosumab in BC patients undergoing AI therapy to prevent bone loss, it is important to understand how such recommendations are followed within specific clinical scenarios. For example, a study by Recine et al. assessed the real-life clinical impact of bone health in patients with BC receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy in an Italian Osteoncology Center (research hospital), confirming that bone health management is an essential part of long-term cancer care [

29].

In our retrospective study, we assessed the impact of bone health clinical management in post-surgical BC patients receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy, in an Italian large-volume research hospital. The primary endpoint was to analyze the clinical pathway that post-surgical BC patients with prescription of AI treatment undergo to prevent bone loss. The secondary endpoint was to design a personalized clinical pathway to ensure a prompt implementation of international and local guidelines, for the assessment and possible prescription of antiresorptive therapy (with Bisphosphonates or Denosumab) with the goal of primary or secondary prevention.

2. Methods

Research hospitals are essential institutions specialized in the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of diseases by combining research and care. They serve as the hub of biomedical sciences, where clinicians and researchers work together to develop excellent treatments, devices, and therapies. In 2018, the Italian Ministry of Health recognized our polyclinic as research hospital for the disciplines of “Personalized Medicine” and “Innovative Biotechnologies”, aiming at providing cutting-edge research and advanced treatment options to patients from around the globe. In 2021, our research hospital received the Joint Commission International (JCI) accreditation and, in 2022, we joined the Organization of European Cancer Institutes (OECI) network.

One of the unique features of our institution is a strong commitment to precision medicine research, which aims at finding “the right treatment, to the right patient, at the right time”, [

30] allowing us to tailor and develop innovative treatments unique for the specific needs of our patients. To this aim, our hospital has a state-of-the-art research infrastructure that houses over 20 laboratories (e.g., biobank, bioinformatics, organoids, 3d bioprinting, genomics, radiomics, liquid biopsy, big data analysis) to support our scientists in conducting their research according to the highest quality standards.

For example, BC biological tissues can be stored in our biobank after surgery, and therefore studied for multiomic profiling, patients’ stratification, and deep phenotyping [

31]. This research infrastructure allowed the implementation of a Comprehensive Cancer Genome Profiling Program for 10 oncological diseases (including BC); such hybrid program combines clinical practices and translational research by using a 500-genes panel to acquire mutational information on a tumor tissue, allowing the identification of genome alterations that may respond to current target therapies, while extending the possibility for patients to access novel treatments and therefore provide targeted therapies [

32]. Specifically, the project for genomic profiling of BC patients started in 2022 and, until now, 11 patients have been profiled.

In this scenario, we conducted an organizational analysis to understand how specialists involved in the care of post-surgical BC patients (prescribed with AI treatment) manage their risk of bone loss, to define the workflow status and, eventually, increase its quality by redesigning the model. The new clinical pathway is part of the study “HEQUOBIP - health and quality of life in Oncological patients: management of bone pathology in the Italian cancer treatment induced bone loss (CTBL) population” (PROT 5147/18 ID 18 - Clinicaltrial.gov: NCT04055805) and received the approval as a standard clinical pathway (PCA -Pathway of Clinical Assistance) for breast cancer at 16-6-2022.

Our Institution is a research hospital, and this pathway (among others) adheres to national regulations, institutional policies and the Helsinki Declaration. Patients provide prior written consent before undergoing any clinical procedure and are treated according to International Guidelines. To redesign the pathway, we refer to the process improvement organizational method [

33,

34], which consists in four phases described as follows:

Analysis: process mapping (“as is”), goals assessment, identification of priorities and key processes, and creation of the team.

Planning: identification of gaps and critical points, and definition of the most relevant changes.

Action: changes implementation, definition of key performance indicators, and development of a data collection method.

Monitoring: control and plan of future improvements, and integration with the management control process.

The Analysis phase explores what is done and what is the value of the current activity in the clinical pathway of BC patients’ candidates to antiresorptive treatments. Oncologists, gynecologists, breast specialists, surgical radiotherapists at our research hospital created a team to assess the workflow by identifying its weaknesses and potentials. Considering its limitations and strengths, we designed a personalized clinical pathway (Planning) to enable prompt implementation of antiresorptive therapy (according to guidelines) to prevent bone loss and fragility fractures, by considering unmet needs and introducing changes in the workflow (Action) with the ambition of reducing BMD assessment within 30 days and therapy prescription within 90 days (Monitoring).

3. Results

3.1. Analysis and Planning

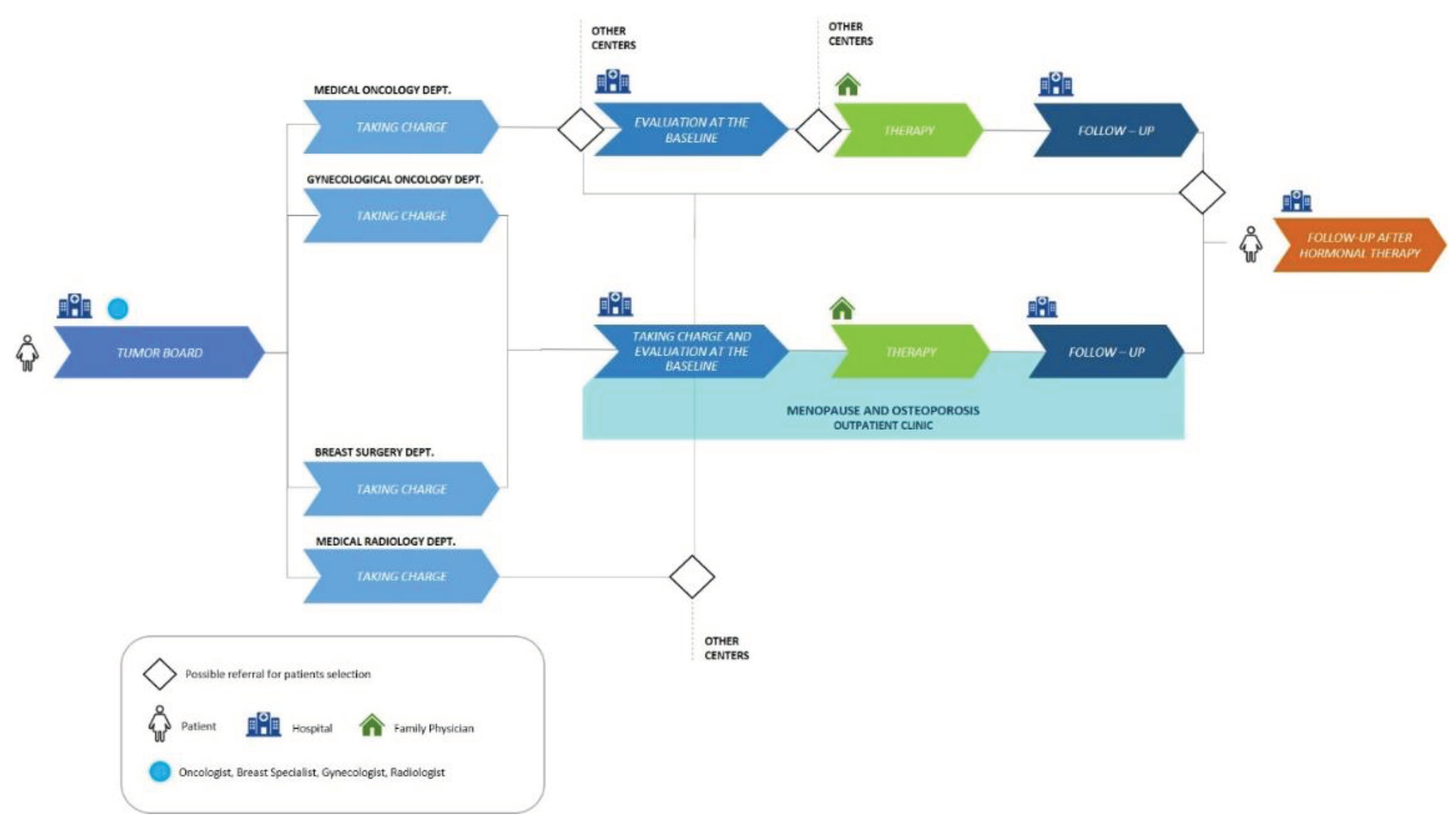

In our previous model (

Figure 1), post-surgery BC patients were discussed in a multidisciplinary tumor board, and those with hormone receptor-positive tumors received indications to start adjuvant endocrine therapy. These patients continued their clinical course in one or more medical departments (Medical Oncology, Gynecological Oncology, Breast Pathology, and Medical Radiology). Some of them were referred to our outpatient clinic specialized in Menopause and Osteoporosis for a basal evaluation of bone status including Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA) of lumbar spine and the hip and a panel of bone metabolism blood tests, followed by prescription of antiresorptive treatment, if appropriate.

Patients underwent annual follow-up with hip and spine DXA and a serum bone metabolism profile until endocrine therapy ended. A final follow-up was scheduled at the end of AI treatment. The rest of the patients (not referred to our Menopause and Osteoporosis outpatient clinic) were referred to different bone health centers nearby or within our hospital.

In analyzing the previous pathway, several critical points and unmet needs were identified. Initially, there was a mismatch between different specialists due to different working hours and organization. The resulting delay in evaluation led to inconsistencies in treatments prescribed (patients were disoriented by the different professionals approaching the problem).

Regarding patient’s taking charge phase, the presence of a tumor board that defines treatment strategies for each patient represented a key asset. Limitations consist in the absence of defined criteria for the distribution of patients between professionals and departments. We therefore understood that criteria should be defined and a bone specialist (e.g., gynecologist, rheumatologist, orthopedic, or endocrinologist) should be identified and involved as early as the tumor board stage, so that the bone health pathway is defined at the same time as the therapeutic strategy.

Another limitation of this phase consisted in the lack of implementation of a structured bone pathway ─which assesses bone status and treats it according to current shared guidelines─ already at the time of prescription of endocrine treatment during tumor board.

During the basal assessment phase, the presence of an outpatient clinic for Menopause and Osteoporosis within the hospital represented a strength. On the other hand, limitations consisted in the lack of dedicated slots for the required diagnostic examinations and the absence of shared assessment criteria for patients’ bone status at the baseline. We also found discrepancies in the timing of patient assessment between different professionals, while the absence of a key case manager figure in such pathway represented a major weakness.

In the treatment phase, a strength was noted regarding the involvement of the family physician in prescribing Denosumab after receiving the treatment plan from the specialist. It was also noted that patients were educated to adopt a correct lifestyle, healthy eating and to perform physical activity. Limitations included the lack of a multidisciplinary team in prescribing treatment and the absence of implementation of Note 79.

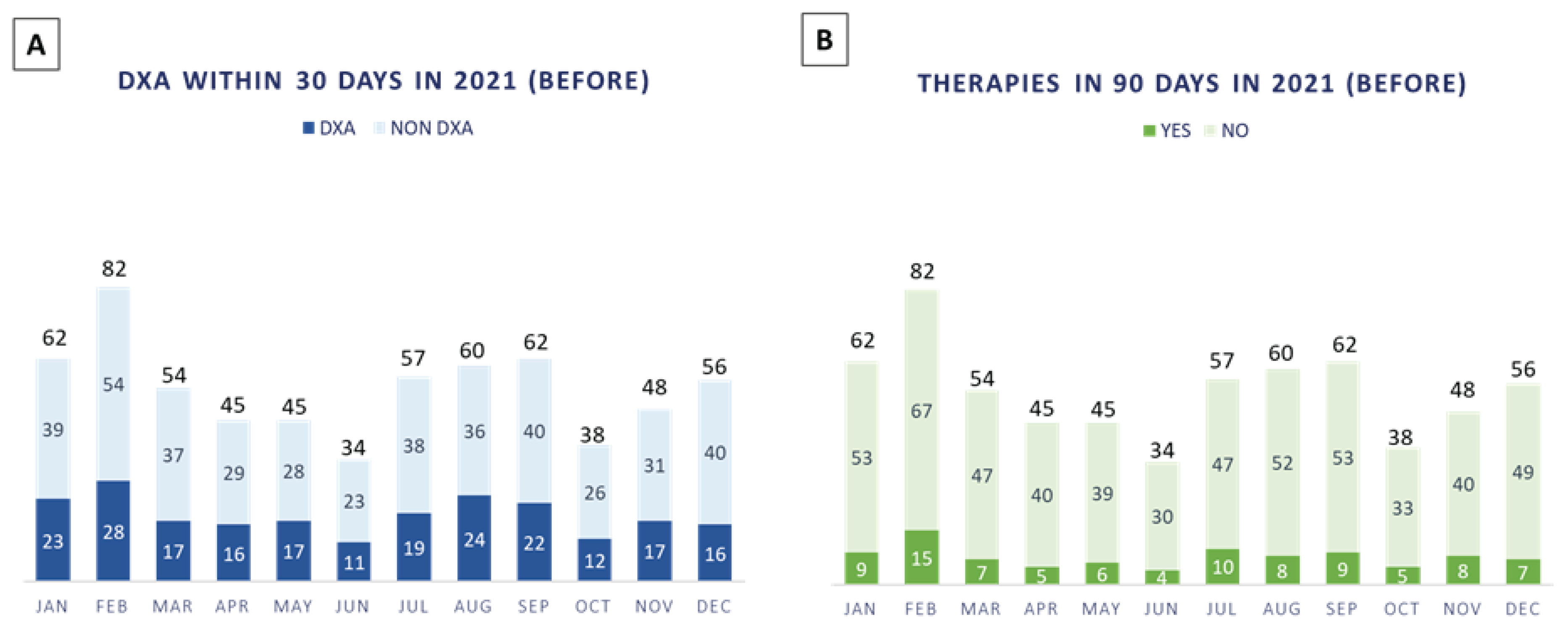

In 2021, n. 643 patients with a new diagnosis of BC were discussed in our multidisciplinary tumor boards, 34% (n. 222/643 patients) of which performed DXA evaluation within 30 days (

Figure 2A) and only 14% (n. 93/643 patients) were prescribed antiresorptive therapies within 90 days (

Figure 2B).

Regarding the follow-up phase, DXA and serum profile of bone metabolism markers were performed annually, and if there was any change in bone status, the patient was referred to our Menopause and Osteoporosis outpatient clinic or to the oncologist; even in this case, we pointed out the lack of a case manager figure to coordinate the bone health pathway. Another limitation was the discrepancy among oncologists regarding the application of eligibility criteria for Note 79 and the timing of bone health assessment.

Additionally, some unmet needs were identified, including the lack of shared criteria between departments for evaluating whether to continue or not treatment after the end of adjuvant endocrine therapy. The lack of referring patients to dedicated bone specialists and the absence of structured protocols for other hospital specialists were noted. The need for a case manager to support the bone health pathway (e.g., filling out the treatment plan, help manage the follow-up phase, and contribute to patient education) remained a primary issue.

Considering all these challenges, the design of a new personalized clinical pathway seemed the most appropriate organizational choice. This analysis created an opportunity to generate a defined workflow that promotes specialists’ training and awareness defining activities, responsibilities, and timeline focused on proper implementation of therapeutic choices.

3.2. Action and Monitoring

As we understood there was a need for implementing a novel pathway to systematically treat patients in a more personalized endeavor, we also set the goal of substantially reducing BMD assessment within 30 days and therapy prescription within 90 days. Such project required the introduction of the following organizational changes:

Alignment between the professionals and design of a dedicated, transversal bone health pathway, to be applied for all BC patients undergoing hormonal adjuvant therapies, in line with the Note 79 (regarding the correct therapy definition) for a personalized patient management and care.

Identification and integration of a bone specialist since the tumor board phase, to define every therapeutic strategy for each patient and evaluate the treatment of bone loss.

Introduction of a case manager (nurse) as a pivotal figure for interprofessional coordination, supporting therapy prescription and follow-up, as well as patient education.

Training of the health professionals and administrative staff involved for activity ownership and timing, to select the best care treatment as well as facilitating the organizational workflow.

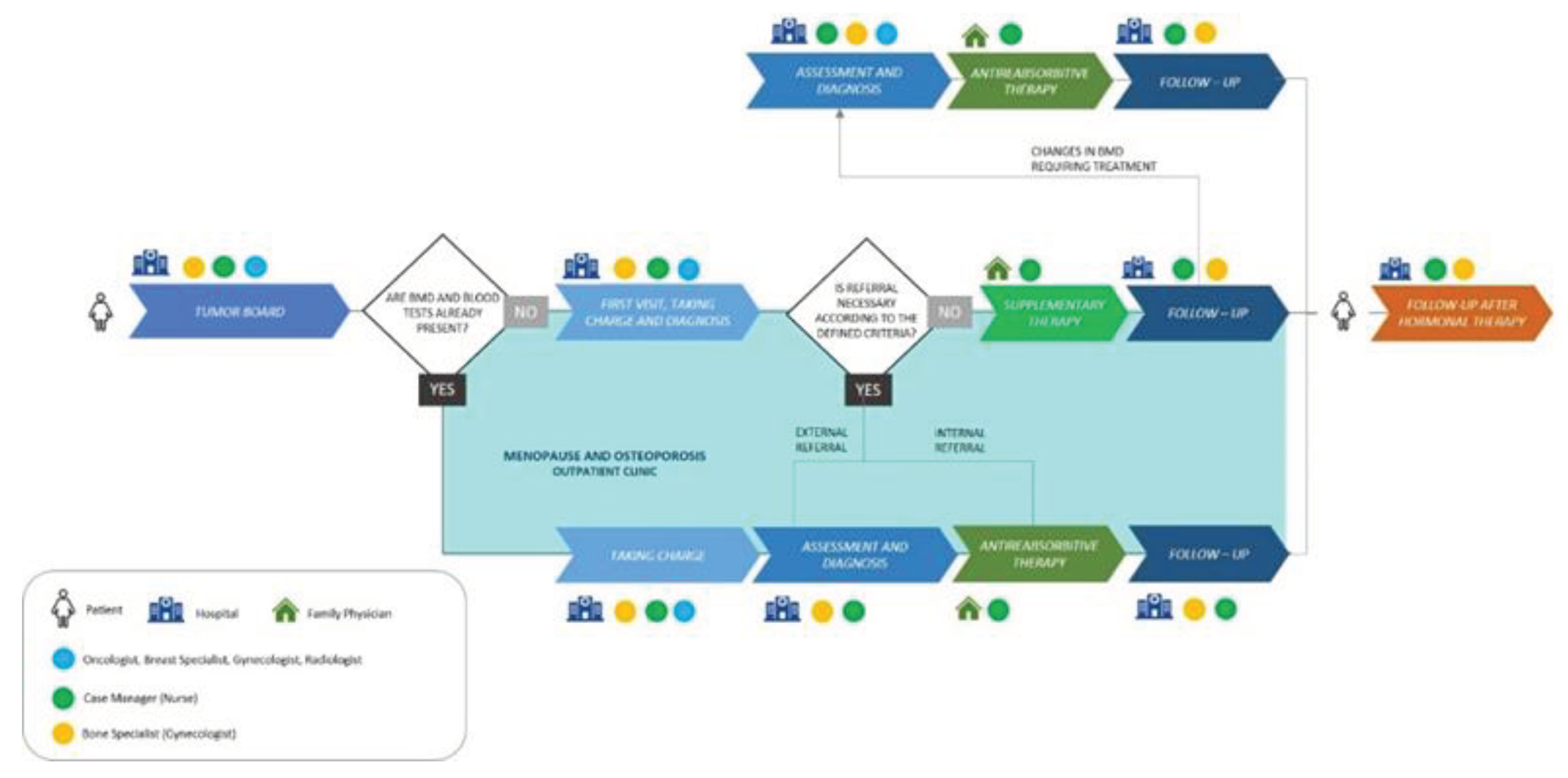

We designed a Diagnostic Therapeutic Assistance Pathway (DTAP) that fully implements international and local guidelines after verification of correct therapies, along with a structured bone health treatment pathway for patients (

Figure 3). The pathway includes a worktable with defined criteria presenting the treatment guidelines to update the participating specialists. It was designed according to the value-based healthcare model, a patient-centered transversal approach to organizational processes [

34].

During the tumor board, a multidisciplinary team consisting of gynecologists, breast specialists, radiologists, and oncologists follows a shared protocol that defines the diagnostic procedures required for basal assessment of bone health, the timing of these assessments, and the criteria for interpreting the diagnostic results. For each case discussion, if a decision is made to describe adjuvant endocrine treatment, the bone health pathway is activated by the case manager (in our organization is a nurse). The case manager verifies with every BC patient who is candidate for adjuvant endocrine treatment whether she has been evaluated by a bone specialist (in our organization is a gynecologist):

- a)

If the patient has not been evaluated, the case manager schedules her within 30 days of the prescription of adjuvant endocrine treatment.

- b)

If the evaluation is already present, the case manager assesses whether the examinations are recent and have them repeated if necessary.

- c)

If no such evaluation is present, the case manager prescribes DXA of spine and femur and blood panel for bone metabolism assessment.

Once the patient has completed the tests, the case manager schedules a meeting at our Menopause and Osteoporosis outpatient clinic, where the patient is be evaluated by the bone specialist. This evaluation and eventual treatment take place within 90 days of the start of adjuvant endocrine treatment. The bone specialist evaluates diagnostic tests and, taking into account the patient’s personal history, risk factors, Note 79, and other medical guidelines, prescribes antiresorptive treatment and, if appropriate, vitamin D and calcium supplementation. Bone health status is monitored by DXA and blood tests throughout the duration of adjuvant endocrine treatment.

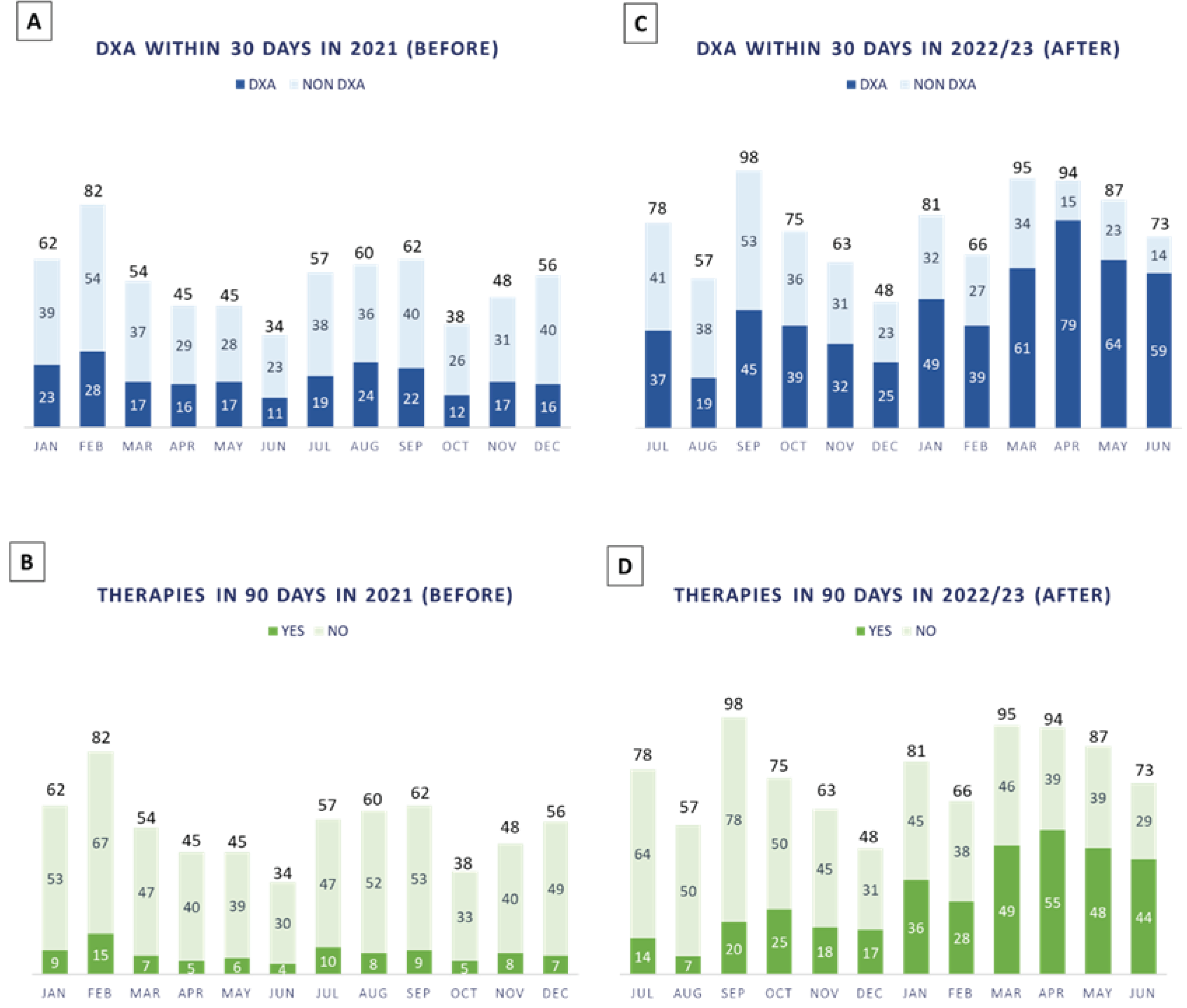

At the end of the BC therapy, further assessment of bone health is conducted to decide whether antiresorptive therapy should be continued, modified, or suspended. In case of vitamin D supplementation alone following normal BMD, the patient will continue annual follow-up to monitor any decline in BMD status. After this evaluation, patients continue to follow-up if needed. In this scenario, we monitored the first year of the new DTAP (

Figure 4 A–D).

From July 2022 to June 2023, n. 915 patients were discussed in our multidisciplinary tumor board for breast cancer, 60% (n. 548/915 patients) of which performed DXA evaluation within 30 days and 39.5% (n. 361/915 patients) were prescribed antiresorptive therapies within 90 days, thus increasing patients’ compliance.

4. Discussion

In complex health care scenarios, standardization of procedures and practices is not always feasible for several reasons, including patients’ flows (in terms of volumes of activities), human resources, organizational mission and vision, clinical assets and expertise [

34]. However, our experience could be useful to acknowledge some aspects that can facilitate patients’ management in large-volume hospitals, with the specific goal of preventing bone loss in BC patients. In fact, the preliminary results in

Figure 4C,D seem to be promising for our goal of substantially increasing DXA assessment within 30 days and therapy prescription within 90 days from AI treatment prescription.

In our research hospital, the case manager contributed significantly to coordinating numerous activities of the new personalized clinical pathway. Case managers complement with skills in assessment, monitoring, cultural competence, interpersonal collaboration, coordination, and advocating of resources and services to achieve patient goals in the health industry. Such professionals also address other social determinants of health, such as the patient’s social economic status, literacy, income, employment, and working conditions that affect patients’ health [

35]. As a nurse (a professional having several skills related to interprofessional education [

36]), our case manager facilitated communication between different specialists and departments, promoting the exchange of clinical information among them efficiently. The case manager also helped in reducing patients’ disorientation by coordinating activities, workflows, and time schedules.

From a clinical perspective, the integration of the case manager in the new pathway (

Figure 4C,D) helped reducing patients’ dropout due to the dispersion of the previous workflow (

Figure 4A,B). It also improved patients’ compliance with treatments by promoting their education while providing information and counselling. Therefore, case managers in bone health care can be of paramount importance in harmonizing the organizational workflow and conducting activities (e.g., monitoring the patient’s DXA, scheduling future visits and diagnostic tests).

Another crucial role has been played by the bone specialist who followed all cases and joined the patient’s case from the tumor board stage. Bone specialists are specialized in the diagnosis, treatment, and management of osteoporosis and other metabolic bone diseases, providing rehabilitation and prevention measures to improve patients’ bone health [

37]. Thus, collaboration among specialists from different departments has enriched and kept specialists up to date with current guidelines regarding bone pathology. Communication among them was facilitated by the presence of the case manager on tumor boards as well. Their cooperation has been significant for developing a shared protocol and define common interpretative criteria on diagnostic results.

In 2022, Italy has been recognized as the second Country with the greatest percentage of aging adults (23%) after Japan (28%) [

38]. Since the population gets older and treatments for breast cancer increase survival, we will treat more patients with the risk of bone loss and fractures in the future. Untreated bone loss often worsens, generating fractures and disabilities requiring surgery and, at times, insertion of prosthesis. Our results show that the implementation of a new DTAP increased the number of patients undergoing specific bone quality analysis within 30 days from tumor board (60% compared to the former 34%) (

Figure 4A,C, respectively). It also increased the number of patients that were prescribed antiresorptive therapies within 90 days from tumor board (37.5% compared to the former 14%), thus improving the promptness of treating bone loss (

Figure 4B,D, respectively). Such findings are important for clinical prevention of fragility fractures and treatment of bone pathology in these patients, personalizing “the right treatment for the right patient, at the right time”.

According to Cauley [

39], major consequences of bone fractures consist of an increased mortality for hip fractures, functional consequences (such as the reductions in quality of life), and the economic burden. Given the high impact of this social phenomenon on health systems worldwide, we outline the importance of fully integrating bone specialists and case managers in clinical pathways since the tumor board stage, to early diagnose and treat bone loss according to local and international guidelines.

Since the project was developed in a research hospital, we must recall that the clinical pathway is strictly intertwined with research laboratories and organizational strategies. The development of an appropriate pathway of care could lead researchers to enroll patients in clinical trials and perform translational medicine studies. Artificial Intelligence algorithms can help identify patients eligible for clinical trials by matching medical records with inclusion criteria to verify eligibility for enrollment [

40]. Next steps will include data collection on patients discussed at tumor boards to longitudinally assess how the new clinical pathway improves multidisciplinary clinical conduct. Future research in this clinical pathway will assess molecular and genetic characteristics of patients with the aim of finding precise biomarkers for preventing bone loss.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.D.A., P.V.; methodology, I.D.A., P.V.; validation, C.N., I.PQ.; I.PR., G.G., A.F., A.O., S.G., G.F., G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, I.D.A.; writing—review and editing, I.D.A.; supervision, P.V. The authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marika D’Oria, PhD for providing scientific counseling.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Wilkinson L, Gathani T. Understanding breast cancer as a global health concern. Br J Radiol 2021; 95:20211033. [CrossRef]

- Associazione Italiana di Oncologia Medica (AIOM). I numeri del cancro in Italia 2022. 2022. Available from: https://www.aiom.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/2022_AIOM_NDC-web.pdf [Last accessed: 07/17/2023].

- Italian Ministry of Health. Il tumore della mammella. 2023. Available from: https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/tumori/dettaglioContenutiTumori.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=5538&area=tumori&menu=vuoto [Last accessed: 07/17/2023].

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:209-49. [CrossRef]

- Howlader N, Altekruse SF, Li CI, et al. US incidence of breast cancer subtypes defined by joint hormone receptor and HER2 status. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106:dju055. [CrossRef]

- Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al. Medication Use to Reduce Risk of Breast Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2019;322:857-67. [CrossRef]

- Nourmoussavi M, Pansegrau G, Popesku J, et al. Ovarian ablation for premenopausal breast cancer: a review of treatment considerations and the impact of premature menopause. Cancer Treat Rev 2017;55:26-35. [CrossRef]

- Hadji P, Aapro MS, Body JJ, et al. Management of Aromatase Inhibitor-Associated Bone Loss (AIBL) in postmenopausal women with hormone sensitive breast cancer: Joint position statement of the IOF, CABS, ECTS, IEG, ESCEO IMS, and SIOG. J Bone Oncol 2017;7:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Saarto T, Vehmanen L, Elomaa I, et al. The effect of clodronate and antioestrogens on bone loss associated with oestrogen withdrawal in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer 2001; 84:1047-51. [CrossRef]

- Confavreux CB, Fontana A, Guastalla JP, et al. Estrogen-dependent increase in bone turnover and bone loss in postmenopausal women with breast cancer treated with anastrozole. Prevention with bisphosphonates. Bone 2007; 41:346-52. [CrossRef]

- Singh S, Cuzick J, Edwards R, et al. Effect of anastrozole on bone mineral density after one year of treatment: results from bone sub-study of the international breast cancer intervention study (IBIS-II). Breast Cancer Res Treat 2007;106:S9.

- Ellis GK, Bone HG, Chlebowski R, et al. Randomized trial of denosumab in patients receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitors for nonmetastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:4875-82. [CrossRef]

- Greenspan SL, Brufsky A, Lembersky BC, et al. Risedronate prevents bone loss in breast cancer survivors: a 2-year, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:2644-52. [CrossRef]

- Lester JE, Dodwell D, Purohit OP, et al. Prevention of anastrozole-induced bone loss with monthly oral ibandronate during adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy for breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res 2008;14:6336-42. [CrossRef]

- Hines SL, Mincey B, Dentchev T, et al. Immediate versus delayed zoledronic acid for prevention of bone loss in postmenopausal women with breast cancer starting letrozole after tamoxifen-N03CC. Breast Cancer Res. Treat 2009;117:603-9. [CrossRef]

- Llombart A, Frassoldati A, Paija O, et al. Zoledronic acid prevents aromatase inhibitor-associated bone loss in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer receiving adjuvant letrozole: E-ZO-FAST 36-month follow-up. Presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2009 Breast Cancer Symposium; 10/8-10/2009. San Francisco, CA. Abstract 213.

- van Poznak C, Hannon RA, Mackey JR, et al. Prevention of aromatase inhibitor-induced bone loss using risedronate: the SABRE trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:967–75. [CrossRef]

- Chlebowski RT, Chen Z, Cauley JA, et al. Oral Bisphosphonate use and breast cancer incidence in postmenopausal women. J. Clin. Oncol 2010;28:3582-90. [CrossRef]

- Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, Hampton JM. Bisphosphonates for osteoporosis treatment are associated with reduced breast cancer risk. Br. J. Cancer 2010;102:799-802. [CrossRef]

- Rennert G, Pinchev M, Rennert HS. Use of bisphosphonates and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3577-81. [CrossRef]

- Gnant M, Pfeiler G, Dubsky PC, et al. Adjuvant denosumab in breast cancer (ABCSG-18): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2015;386:433-43. [CrossRef]

- Gnant M, Pfeiler G, Steger GG, et al. Adjuvant denosumab in postmenopausal patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer (ABCSG-18): disease-free survival results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2019; 20:339-351. [CrossRef]

- Associazione Italiana di Oncologia Medica (AIOM). Linee guida. Neoplasie della Mammella. 2020. Available from: https://www.aiom.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/2020_LG_AIOM_NeoplasieMammella.pdf [Last accessed: 07/17/2023].

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (AIFA). Nota 79. Farmaci a carico SSN inclusi nella Nota 79: Alendronato, Bazedoxifene, Denosumab, Ibandronato, Raloxifene, Risedronato, Romosozumab, Teriparatide, Zoledronato. 2017. Available from: https://www.aifa.gov.it/nota-79 [Last accessed: 07/17/2023].

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Adjuvant bisphosphonate treatment in early breast cancer: Meta-analyses of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet 2015;386:1353-61. [CrossRef]

- Coleman RE, Finkelstein D, Barrios CH, et al. Adjuvant denosumab in early breast cancer: First results from the international multicenter randomized phase III placebo controlled D-CARE study. J Clin Oncol 2018;38:4569-4580. [CrossRef]

- Gnant M, Pfeiler G, Steger GG, et al. Adjuvant denosumab in early breast cancer: Disease-free survival analysis of 3425 postmenopausal patients in the ABCSG-18 trial. J Clin Oncol 2018;20:339-51. [CrossRef]

- Perrone F, De Laurentiis M, de Placido S, et al. The HOBOE-2 multicenter randomized phase III trial in premenopausal patients with hormone-receptor positive early breast cancer comparing triptorelin plus either tamoxifen or letrozole or letrozole + zoledronic acid. Ann. Oncol 2018;29:viii704. [CrossRef]

- Recine F, Bongiovanni A, Foca F, et al. BOne HEalth ManagEment in Patients with Early Breast Cancer: A Retrospective Italian Osteoncology Center “Real-Life” Experience (BOHEME Study). J Clin Med 2019;8:1894. [CrossRef]

- Nimmesgern E, Benediktsson I, Norstedt I. Personalized Medicine in Europe. Clin Transl Sci 2017;10:61-3. [CrossRef]

- De Maria Marchiano R, Di Sante G, Piro G, et al. Translational Research in the Era of Precision Medicine: Where We Are and Where We Will Go. J Pers Med 2021;11:216. [CrossRef]

- Nero C, Duranti S, Giacomini F, et al. Integrating a Comprehensive Cancer Genome Profiling into Clinical Practice: A Blueprint in an Italian Referral Center. J Pers Med 2022;12:1746. [CrossRef]

- Davenport HT. Process innovation. Reengineering work through Information Technology. Harvard: Harvard Business Press; 1993.

- Villa S. Operations Management for Healthcare Organizations. Theory, Models and Tools. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge; 2021.

- Mwandala T. Roles, Training, and Qualifications of a Case Manager in the Canadian Health Care Industry: A Narrative Review. Prof Case Manag 2021;26:27-33. [CrossRef]

- Palese A, Gonella S, Brugnolli A, et al. Nursing students’ interprofessional educational experiences in the clinical context: findings from an Italian cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e025575. [CrossRef]

- Tarantino U, Iolascon G, Cianferotti L. et al. Clinical guidelines for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis: summary statements and recommendations from the Italian Society for Orthopaedics and Traumatology. J Orthop Traumatol 2019;18:3–36. [CrossRef]

- PRB. Countries with the Oldest Populations in the World. 2022. Available from: https://www.prb.org/resources/countries-with-the-oldest-populations-in-the-world/ [Last accessed: 07/17/2023].

- Cauley JA. Public health impact of osteoporosis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2013;68(10):1243-51. [CrossRef]

- Cesario A, Simone I, Paris I, et al. Development of a Digital Research Assistant for the Management of Patients' Enrollment in Oncology Clinical Trials within a Research Hospital. J Pers Med. 2021; 11(4):244. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.f |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).