Submitted:

09 October 2025

Posted:

10 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

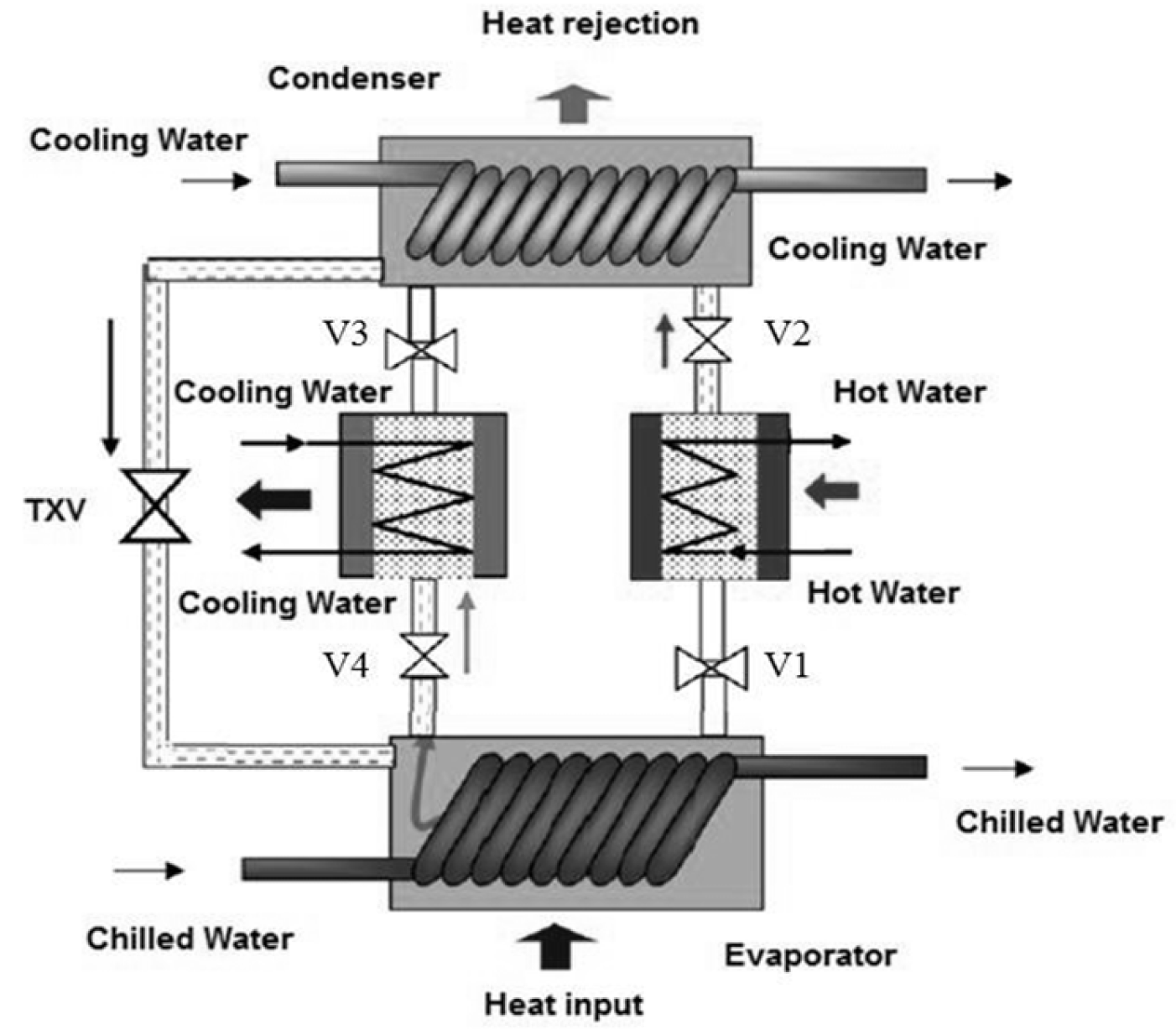

2.1. Working Principle of A Two-Bed Adsorption Chiller

3. Analysis and Modelling

3.1. Assumptions

- Uniform distribution: The temperature, pressure, and the quantity of adsorbed water vapor are assumed to be spatially uniform within each adsorbent bed. This assumption simplifies the model to a lumped-parameter approach.

- Adiabatic insulation: All components, including the adsorber and desorber, are considered to be perfectly insulated, thus neglecting any heat losses to the ambient environment.

- Ideal vapor transport: The water vapor desorbed from the adsorbent is assumed to flow instantaneously and completely into the condenser, without accumulation or delay.

- Ideal condensate flow: The condensate from the condenser is assumed to flow immediately and without resistance into the evaporator.

- Instantaneous evaporation and adsorption: The liquid water entering the evaporator is presumed to evaporate instantaneously under vacuum conditions, and the generated vapor is assumed to be adsorbed instantaneously in the cooled adsorber bed.

- Phase modeling: The adsorbed water is considered to exist in liquid phase, while the water vapor behaves as an ideal gas. This allows the use of the ideal gas law in mass and energy balance equations.

- Negligible hydraulic resistance: Pressure losses and flow resistances in the pipelines and valves are neglected.

- Constant properties: The thermophysical properties of the adsorbent material, working fluid (water), heat exchanger tubes (metal), and water vapor are considered to be constant throughout the cycle.

| Parameter | Value |

| ma | 50 Kg |

| 〖∆H〗_ads | 2800 kJ/kg |

| L_v | 2500 kJ/kg |

| Ccd ,Cev, C_ad | 0.386 kJ/kg.K |

| 〖Cp〗_(r,v) | 1.85 kJ/kg.K |

| C_a | 0.924 kJ/kg.K |

| C_pr | 4.18 kJ/kg.k |

| m·_(f,ad) | 1.6 m3/h |

| m·_(f,cd) | 3.7 m3/h |

| m·_(f,ev) | 2 m3/h |

| T_(ev,in) | 15 °C |

| T_(cd,in) | 22 °C, |

| T_(gn,in) | 62 °C |

| t_cycle | 840 s |

4. Results

4.1. Experimental Setup

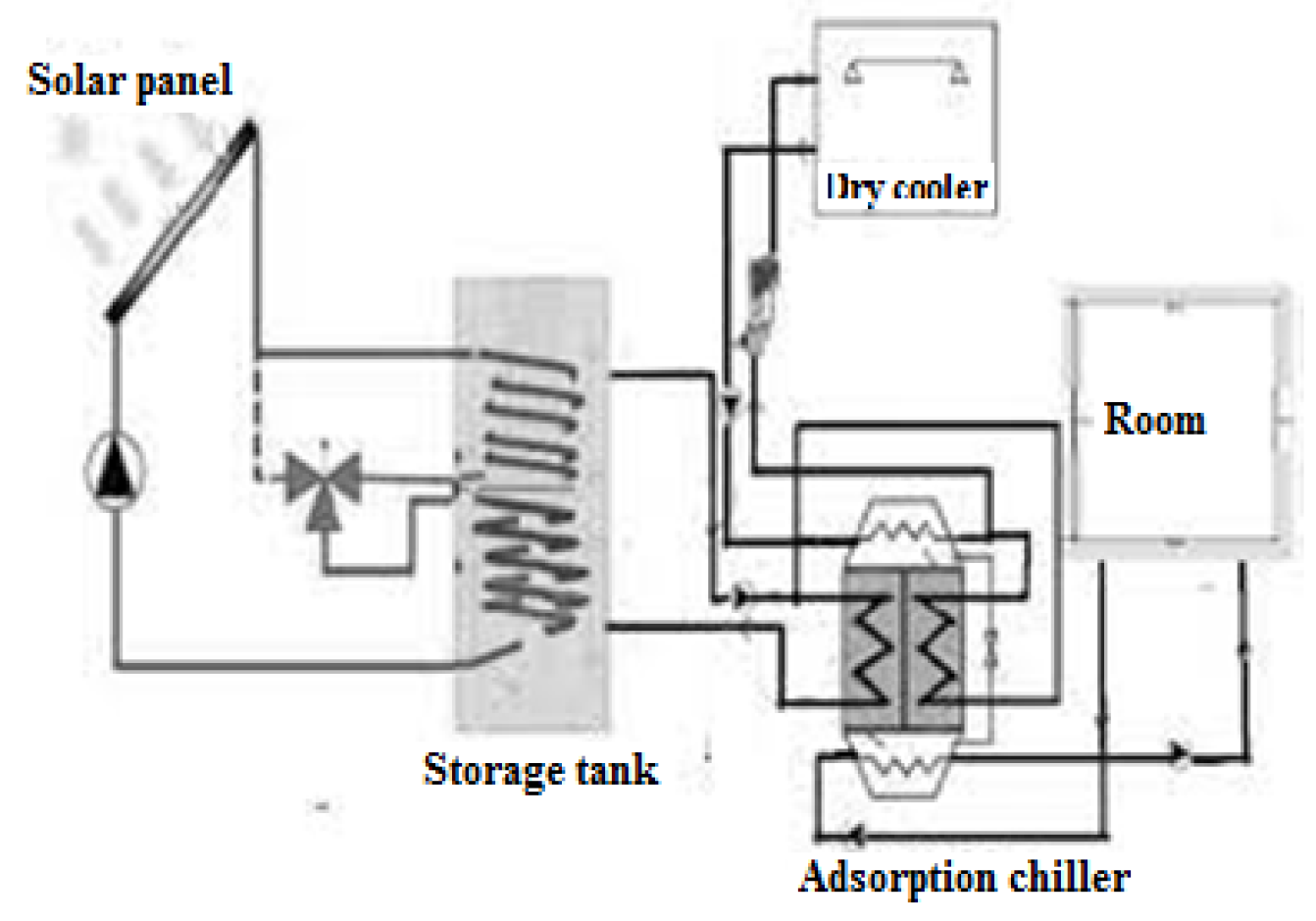

- A field of solar thermal collectors, responsible for harnessing solar energy and converting it into heat.

- A stratified thermal storage tank, used to store hot water generated by the solar collectors for subsequent use in desorption and domestic heating.

- A gas-fired cogenerator, based on an internal combustion engine, which produces both electricity and thermal energy. The recovered heat is used either for space heating or to supply the adsorption chiller.

- An adsorption refrigeration machine (ARM), which is activated by the thermal energy from the solar tank or cogenerator and delivers chilled water for air-conditioning applications.

- Expansion vessels for system safety, and hydraulic pumps to ensure fluid circulation between components.

- Plate heat exchangers to improve heat transfer in various loops.

- A climatic chamber, constructed from solid glued laminated timber, which consists of two thermally separated compartments, each with a volume of 27 m³. One chamber is conditioned using a chilled ceiling for cooling, while the other uses a heated floor for space heating.

4. Discussion

- Improved system flexibility and operational stability.

- Maximized utilization of available thermal and electrical energy.

- Reduced carbon footprint, by relying exclusively on renewable-based sources.

- Enhanced potential for off-grid or microgrid applications, especially in remote or arid regions where solar resources are abundant but cooling demand is high.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Almohammadi, A.; Riahi, A.; El-Shafie, M.; Khosravi, A. Operational conditions optimization of a proposed solar-powered adsorption cooling system: Experimental, modeling, and optimization algorithm techniques. Energy 2021, 206, 118007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalil, M.A.; Sidik, N.A.C.; Samion, S.; Kadirgama, K. Effect of adsorbent configuration on performance of a continuous solar adsorption chiller. Renew. Energy 2020, 158, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheniti, M.B.; Abdelrahman, A.K.; Shatat, M. Performance of a solar adsorption cooling and desalination system using aluminum fumarate and silica gel. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 194, 117085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatibi, J.; Taherian, H.; Momeni, M. Optimal aluminum additive loading in finned heat exchangers for adsorption systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 196, 117267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.P.Q.; Tay, K.H.; Shahzad, M.W.; Ng, K.C. Field synergy analysis for heat/mass transfer in adsorption-based desalination. Desalination 2020, 517, 115226. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.A.; Mahbub, M.; Rahman, M. Thermophysical properties of silica gels for adsorption cooling. Int. J. Refrig. 2020, 110, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzinger, C.; Reimann, A.; Alefeld, G. Life cycle assessment of a solar adsorption refrigerator. Int. J. Refrig. 2021, 121, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Wang, R.Z.; Xia, Z.Z. Solar heat pipe silica gel–water adsorption chiller with recovery. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2013, 50, 1015–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Saha, B.B.; Aristov, Y.I. Effect of grain size on dynamic performance of silica gel-based chillers. Energy 2020, 78, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocky, K.A.; Saha, B.B.; Tay, K.H. Specific heat capacity of parent and composite adsorbents. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 164, 114438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.; Wang, R.Z.; Xia, Z.Z. Experimental performance of a silica gel–water adsorption chiller. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2005, 25, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, R.P.; Choudhury, B.; Das, R.K. Comparative study of waste-heat driven silica gel adsorption systems. J. Energy Storage Appl. 2024, 57, 212–222. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, M.W.; Ng, K.C. Hybrid adsorption desalination and cooling using silica gel. Desalination 2019, 467, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Ng, K.C. Solar-driven adsorption desalination system. Energy Procedia 2014, 49, 2261–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, K.; Ahmed, S.; Saha, B.B. Heat capacities of carbon-based adsorbents for heat pumps. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 129, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, S.K.; Erhard, S.; Müller, D. Water vs methanol in silica gel chillers: A model-based study. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 236, 121816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, J. Performance of consolidated carbon-based adsorbents in heat pumps. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 217, 119100. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, R.; Silva, A.M.; Martins, N. Full system modeling of adsorption heat pump. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 213, 118792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, I.; Saha, B.B.; Chakraborty, A. Effect of metal doping on aluminum fumarate sorbents. Heat Transf. Eng. 2021, 42, 421–431. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh, P.S.; Choudhury, B.; Das, R.K. Performance analysis of two-bed silica gel chiller. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2016, 37, 30–46. [Google Scholar]

- Tso, C.Y.; Chao, C.Y.H. Composite adsorbents for enhanced adsorption cooling performance. Energy Convers. Manag. 2012, 55, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Boelman, E.C.; Saha, B.B.; Kashiwagi, T. Performance of silica gel–water chiller with heat recovery. Int. J. Refrig. 1995, 18, 239–246. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki, T.; Akisawa, A.; Kashiwagi, T. Three-bed adsorption cooling system performance. Energy 2010, 35, 967–972. [Google Scholar]

- Sapienza, A.; et al. Cycle optimization in zeolite-based adsorption cooling. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 4833–4842. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, D.Y.R.; Saha, B.B.; Ng, K.C. Comparative study of working pairs for low-temperature adsorption. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 172, 115147. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, A.A.; Mohamed, E.A.; Ramadan, M.K. Integrated adsorption multigeneration systems. Int. J. Refrig. 2020, 116, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J. 4E analysis of SOFC-CCHP system with LiBr chiller. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 5284–5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimelli, A.; et al. Energy-economic feasibility of battery-CCHP hybrid with adsorption unit. Energy 2025, 317, 134640. [Google Scholar]

- Abedi, M.; Jamei, A.; Asadi, M. Feasibility of solar chimney humidification–dehumidification. Renew. Energy 2023, 202, 88–102. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, M.T.; Nguyen, T.H. Efficient solar thermal water-splitting hydrogen production: A review. WIREs Energy Environ. 2024, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).