Submitted:

26 August 2025

Posted:

28 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Computational Domain and Mathematical Formulation

2.1. Problem Statement

2.2. Modified Dubinin-Astakhov (DA) Model for Hydrogen Adsorption

- : Adsorbed amount (mol/kg)

- : Maximum adsorption capacity (saturation limit)

| Temperature-dependent energy term |

- ∘

- : Material-specific constants (linked to adsorbent-adsorbate interactions)

- ∘

- : Universal gas constant

- Saturation pressure of

- The coefficient is material-dependent and can be adjusted according to the specific MOF under investigation. Notably, has been established as the optimal value for modeling hydrogen adsorption in both MOF-5- and activated carbon, consistent with prior experimental validations.

2.3. Governing Equations

- Hydrogen gas is considered as ideal gas;

- The mass source term, , indicates the amount of hydrogen undergoing a phase change, from the adsorbed phase to the bulk phase;

- The average velocity related to the hydrogen flow through the porous medium, , is described by Darcy’s law;

- No volume changes with time, ;

- The temperature difference between the fluid and solid phases of the porous system is negligible, so the local thermal equilibrium approach is adopted for energy equation;

- The flow regime is considered laminar.

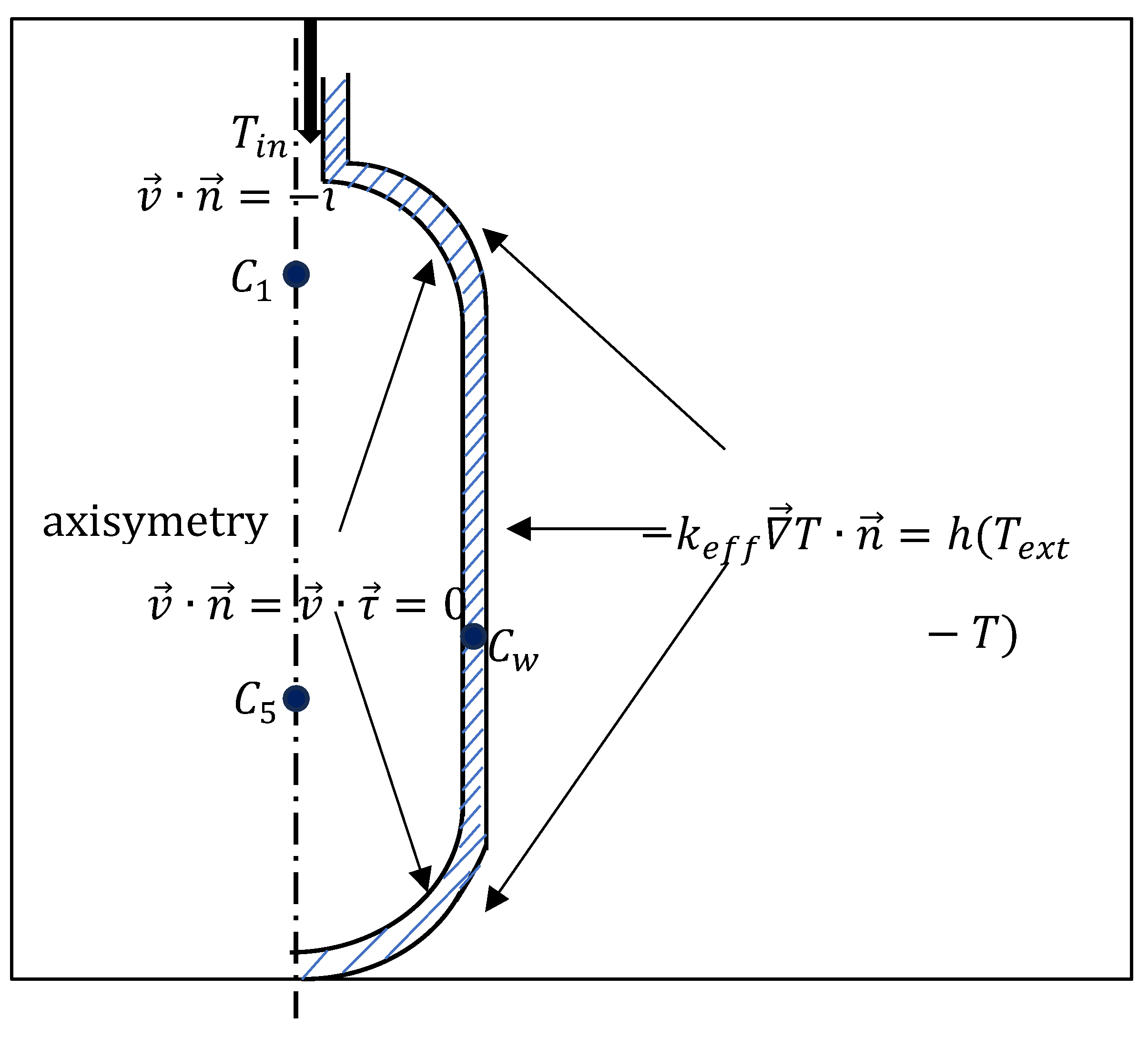

2.4. Initial and Boundary Conditions

3. Numerical Method, Grid Invariance and Validation

3.1. Numerical Method

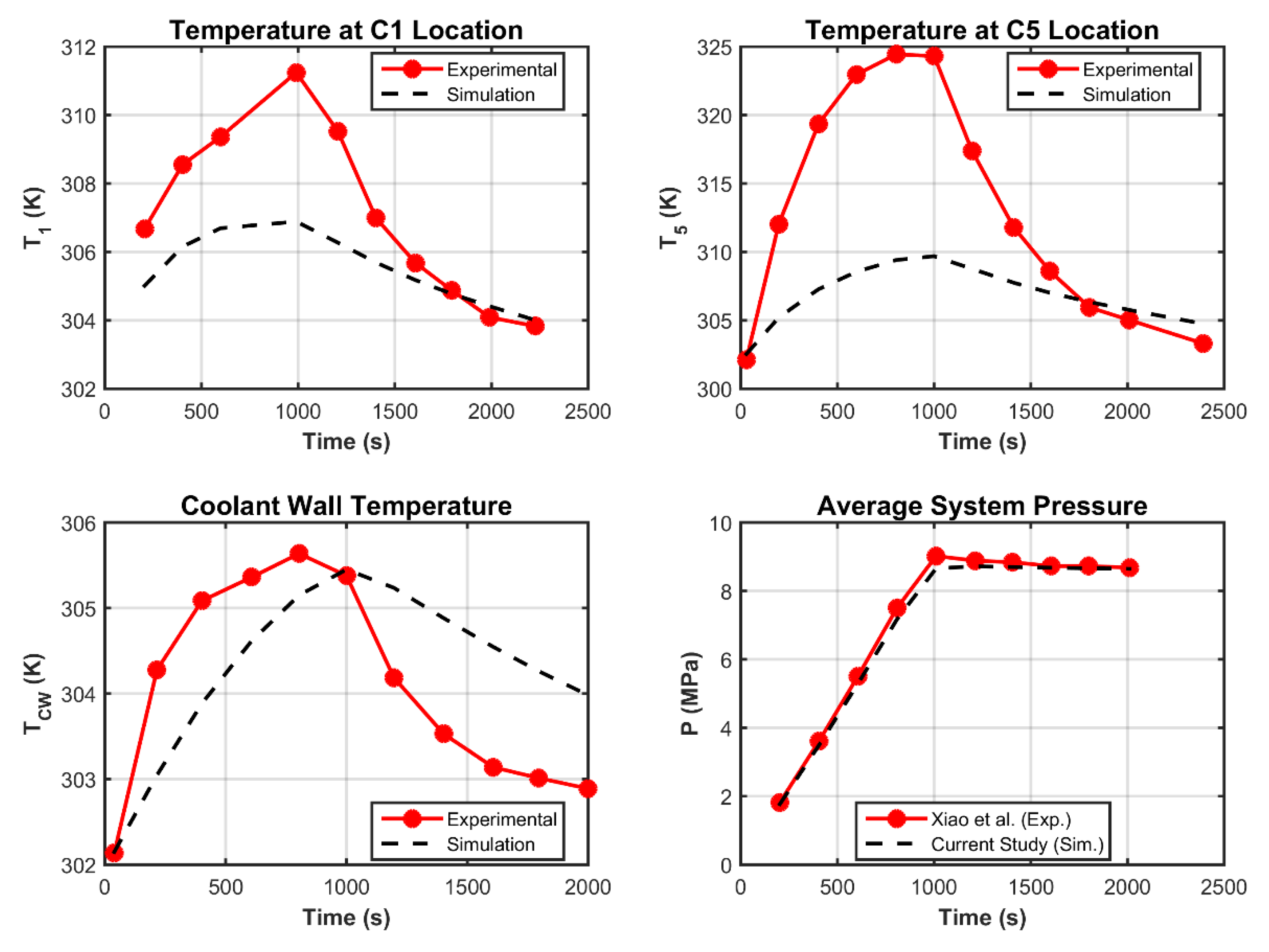

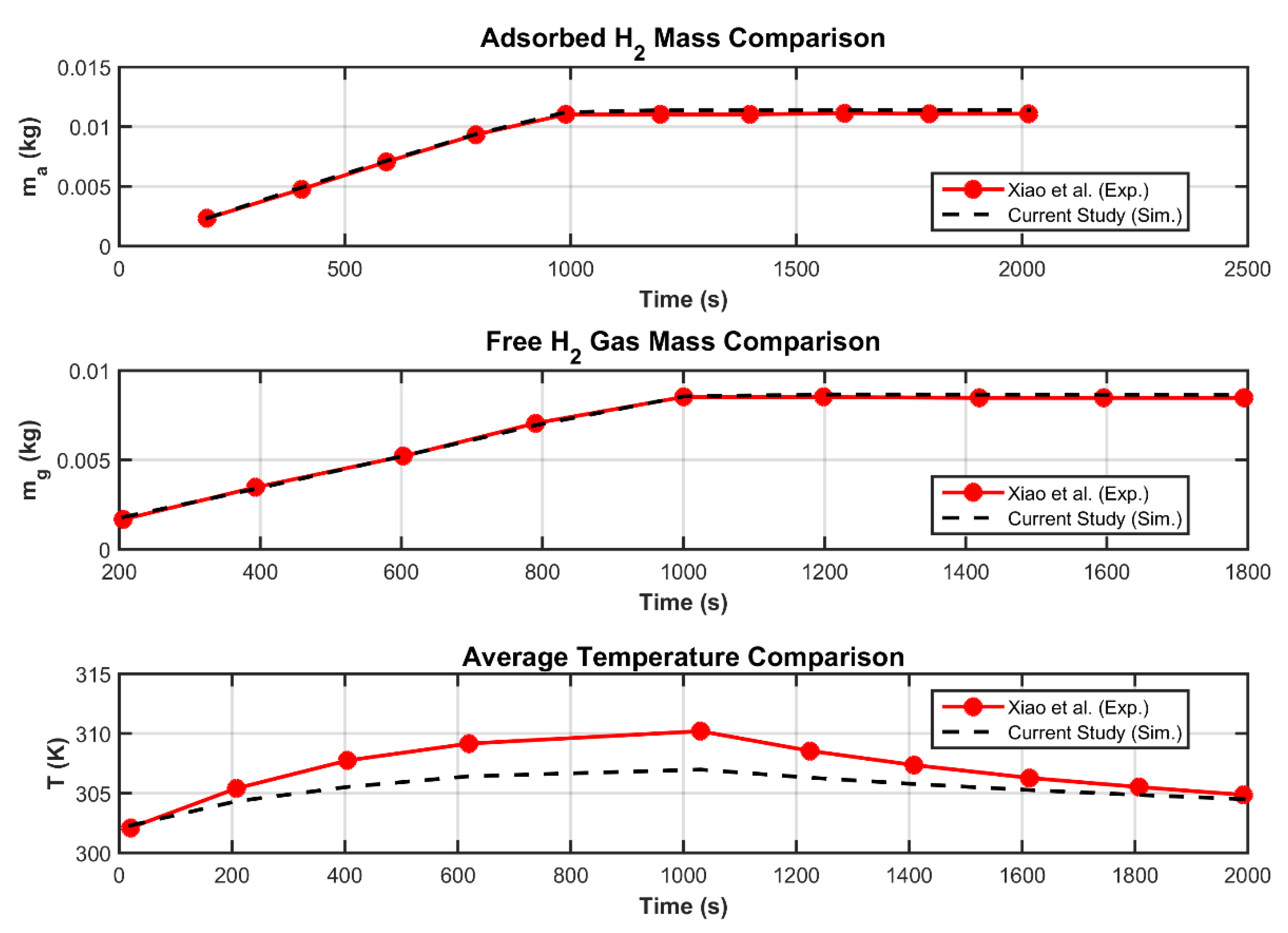

3.2. Grid Invariance and Validation

4. Parametric Study

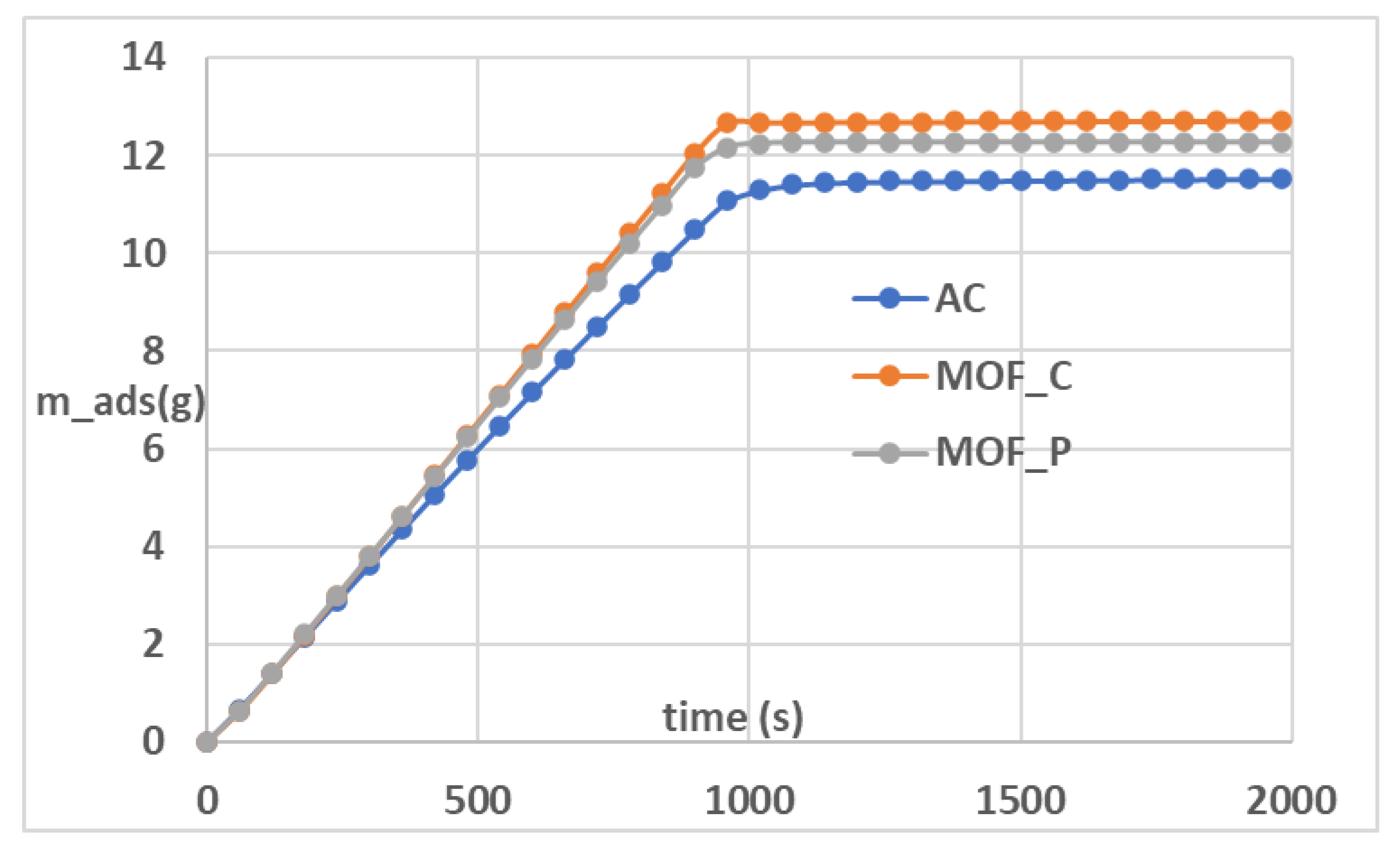

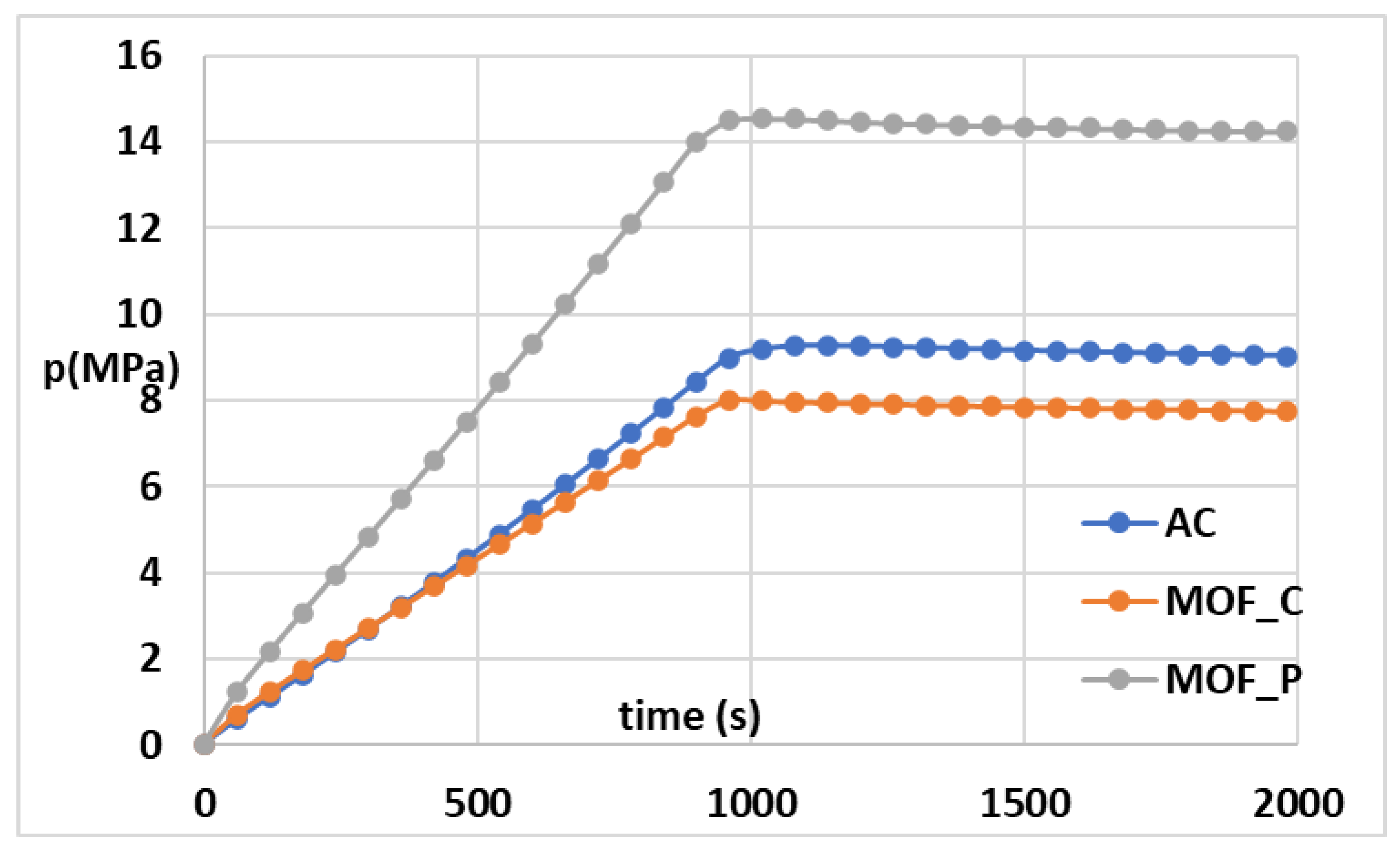

4.1. Effect of Material Properties

4.2. Effect of “Temperature and Flow Rate” Injection

5. Conclusions and Perspectives for Future Work

Nomenclature

| specific heat capacity | |

| particle diameter of adsorbent | |

| heat transfer coefficient | |

| thermal conductivity | |

| Molecular mass of hydrogen | |

| mass of adsorbed phase hydrogen | |

| mass of gas phase hydrogen | |

| total mass of hydrogen in tank | |

| absolute adsorption amount per unit adsorbent | |

| limit adsorption amount per unit adsorbent | |

| pressure | |

| limited pressure | |

| adsorption heat | |

| universal gas constant | |

| rate, of hydrogen transfer from gas phase to adsorbed phase | |

| temperature | |

| Darcy velocity vector | |

| isosteric heat of adsorption | |

| Greek symbols | |

| enthalpic factor | |

| entropic factor | |

| density | |

| permeability of porous material | |

| dynamic viscosity | |

| bed porosity | |

| Subscript | |

| a | adsorbent |

| ext | exterior or ambient |

| int | initial |

| inj | injection |

| eff | effective |

| p | particles |

| g | gas phase |

References

- A.Z. Arsad, M.A. Hannan, Ali Q. Al-Shetwi, R.A. Begum, M.J. Hossain, Pin Jern Ker, TM Indra Mahlia, Hydrogen electrolyser technologies and their modelling for sustainable energy production: A comprehensive review and suggestions, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 48, Issue 72, 2023, Pages 27841-27871, ISSN 0360-3199. [CrossRef]

- Hydrogen liquefaction: a review of the fundamental physics, engineering practice and future opportunities Saif ZS. Al Ghafri, Stephanie Munro, Umberto Cardella, Thomas Funke, William Notardonato, J. P. Martin Trusler, Jacob Leachman, Roland Span, Shoji Kamiya, Garth Pearce, Adam Swanger, Elma Dorador Rodriguez, Paul Bajada, Fuyu Jiao, Kun Peng, Arman Siahvashi, Michael L. Johns and Eric F. May Energy & environmental science 15 (7), 2690-2731. [CrossRef]

- Ayoub Aitakka Nalla, Mourad Nachtane, Xiaobin Gu, Mustapha El Alami, Ayoub Gounni, Advances in numerical modeling and experimental insights for hydrogen storage systems: A comprehensive and critical review, Journal of Energy Storage, Volume 128, 2025, 117206, ISSN 2352-152X. [CrossRef]

- Farshid Mahmoodi, Rahbar Rahimi, Experimental and numerical investigating a new configured thermal coupling between metal hydride tank and PEM fuel cell using heat pipes, Applied Thermal Engineering, Volume 178, 2020, 115490, ISSN 1359-4311. [CrossRef]

- Briki, C.; Dunikov, D.; Almoneef, M.M.; Romanov, I.; Kazakov, A.; Mbarek, M.; Abdelmajid, J. Experimental and Theoretical Studies of Hydrogen Storage in LaNi4.4Al0.3Fe0.3 Hydride Bed. Materials 2023, 16, 5425. [CrossRef]

- Rafik Elkhatib, Hasna Louahlia, Metal hydride cylindrical tank for energy hydrogen storage: Experimental and computational modeling investigations, Applied Thermal Engineering, Volume 230, Part A, 2023, 120756, ISSN 1359-4311. [CrossRef]

- Safia Harrat, Chaker Briki, Mounir Sahli, Abdelhakim Settar, Khaled Chetehouna, Abdelmajid Jemni, Experimental investigation of the hydrogen storage capacity in LaNi3.6Al0.4Mn0.3Co0.7 alloy, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 77, 2024, Pages 33-39, ISSN 0360-3199. [CrossRef]

- Wang C-S, Brinkerhoff J. Low-cost lumped parameter modelling of hydrogen storage in solid-state materials. Energy Convers Manag 2022;251:115005. [CrossRef]

- Jinsheng Xiao, Qian Li, Daniel Cossement, Pierre Bénard, Richard Chahine, Lumped parameter simulation for charge-discharge cycle of cryo-adsorptive hydrogen storage system, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 37, Issue 18, 2012, Pages 13400-13408, ISSN 0360-3199. [CrossRef]

- Jinsheng Xiao, Min Hu, Daniel Cossement, Pierre Bénard, Richard Chahine, Finite element simulation for charge–discharge cycle of cryo-adsorptive hydrogen storage on activated carbon, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 37, Issue 17, 2012, Pages 12947-12959, ISSN 0360-3199. [CrossRef]

- Jinsheng Xiao, Jijuan Wang, Daniel Cossement, Pierre Bénard, Richard Chahine, Finite element model for charge and discharge cycle of activated carbon hydrogen storage, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 37, Issue 1, 2012, Pages 802-810, ISSN 0360-3199. [CrossRef]

- Jinsheng Xiao, Rong Peng, Daniel Cossement, Pierre Bénard, Richard Chahine, CFD model for charge and discharge cycle of adsorptive hydrogen storage on activated carbon, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 38, Issue 3, 2013, Pages 1450-1459, ISSN 0360-3199. [CrossRef]

- Jinsheng Xiao, Rong Peng, Daniel Cossement, Pierre Bénard, Richard Chahine, Heat and mass transfer and fluid flow in cryo-adsorptive hydrogen storage system, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 38, Issue 25, 2013, Pages 10871-10879, ISSN 0360-3199. [CrossRef]

- J. Yao, et al., A continuous hydrogen absorption/desorption model for metal hydride reactor coupled with PCM as heat management and its application in the fuel cell power system, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 45 (52) (Oct. 2020) 28087-28099. [CrossRef]

- B. Arslan, M. Ilbas, S. Celik, Experimental analysis of hydrogen storage performance of a LaNi5-H2 reactor with phase change materials, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48 (15) (2023) 6010-6022. [CrossRef]

- Yang Ye, Jing Ding, Weilong Wang, Jinyue Yan, The storage performance of metal hydride hydrogen storage tanks with reaction heat recovery by phase change materials, Applied Energy, Volume 299, 2021, 117255, ISSN 0306-2619. [CrossRef]

- Atef Chibani, Chahrazed Boucetta, Mohammed Amin Nassim Haddad, Slimane Merouani, Samir Adjel, Safia Merabet, Houssem Laidoudi, Cherif Bougriou, Effect of fin material type and reactor inclination angle on hydrogen adsorption process in large-scale activated carbon-based heat storage system, Journal of Energy Storage, Volume 98, Part B, 2024, 113091, ISSN 2352-152X. [CrossRef]

- Zelenak V, Saldan I. Factors affecting hydrogen adsorption in metal-organic frameworks: a short review. Nanomaterials 2021;11(7):1638. [CrossRef]

- Chuchuan Peng, Rui Long, Zhichun Liu, Wei Liu, Improving adsorption hydrogen storage performance via triply periodic minimal surface structures with uniform and gradient porosities, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 53, 2024, Pages 422-433, ISSN 0360-3199. [CrossRef]

- Jiahao Wang, Daniele Melideo, Lorenzo Ferrari, Paolo Taddei Pardelli, Umberto Desideri, Study on the influence echanism of fin structure on the filling performance of cold adsorption hydrogen storage tank, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 94, 2024, Pages 897-911, ISSN 0360-3199. [CrossRef]

- Anurag Singh, M.P. Maiya, S. Srinivasa Murthy, Effects of heat exchanger design on the performance of a solid state hydrogen storage device, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 40, Issue 31, 2015, Pages 9733-9746, ISSN 0360-3199. [CrossRef]

- Jiahao Wang, Daniele Melideo, Lorenzo Ferrari, Paolo Taddei Pardelli, Umberto Desideri, Integrated targeted pre-cooling tubes and fins for enhanced hydrogen adsorption in activated carbon storage tank, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 146, 2025, 149942, ISSN 0360-3199. [CrossRef]

- Xuan Huang, Suke Jin, Meng Yu, Yang Li, Ming Li, Jianye Chen, Numerical studies of a new device for a cryo-dsorption hydrogen storage system, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 82, 2024, Pages 1051-1059, ISSN 0360-3199. [CrossRef]

- Jiahao Wang, Daniele Melideo, Lorenzo Ferrari, Paolo Taddei Pardelli, Umberto Desideri, Study on the influence mechanism of fin structure on the filling performance of cold adsorption hydrogen storage tank, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 94, 2024, Pages 897-911, ISSN 0360-3199. [CrossRef]

- Jiahao Wang, Daniele Melideo, Lorenzo Ferrari, Paolo Taddei Pardelli, Umberto Desideri, Integrated targeted pre-cooling tubes and fins for enhanced hydrogen adsorption in activated carbon storage tank, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 146, 2025, 149942, ISSN 0360-3199. [CrossRef]

- Hind Jihad Kadhim Shabbani, Ammar Ali Abd, Masad Mezher Hasan, Zuchra Helwani, Jinsoo Kim, Mohd Roslee Othman, Effect of thermal dynamics and column geometry of pressure swing adsorption on hydrogen production from natural gas reforming, Gas Science and Engineering, Volume 116, 2023, 205047, ISSN 2949-9089. [CrossRef]

- Chuchuan Peng, Rui Long, Zhichun Liu, Wei Liu, Improving adsorption hydrogen storage performance via triply periodic minimal surface structures with uniform and gradient porosities, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 53, 2024, Pages 422-433, ISSN 0360-3199. [CrossRef]

- Lijin Chen, Valeska P. Ting, Yuxuan Zhang, Shuai Deng, Shuangjun Li, Zhenyuan Yin, Fei Wang, Xiaolin Wang, Modeling adsorption-based hydrogen storage in nanoporous activated carbon beds at moderate temperature and pressure, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 122, 2025, Pages 159-179, ISSN 0360-3199. [CrossRef]

- Daniele Melideo, Lorenzo Ferrari, Paolo Taddei Pardelli, CFD simulation of hydrogen storage: Adsorption dynamics and thermal management in cryogenic tanks, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2025, 149261, ISSN 0360-3199. [CrossRef]

- Georg Klepp, Modelling activated carbon hydrogen storage tanks using machine learning models, Energy, Volume 306, 2024, 132318, ISSN 0360-5442. [CrossRef]

- Richard MA, Cossement D, Chandonia PA, Chahine R, MoriD, Hirose K. Preliminary evaluation of the performance of an adsorption-based hydrogen storage system. AIChE 2009; 55: 2985e96. [CrossRef]

- Richard MA, Bénard P, Chahine R. Gas adsorption process inactivated carbon over a wide temperature range above the critical point. Part 1: modified Dubinin-Astakhov model. Adsorption 2009; 15:43-51. [CrossRef]

- V. Nicolas, G. Sdanghi, K. Mozet, S. Schaefer, G. Maranzana, A. Celzard, V. Fierro, Numerical simulation of thermally driven hydrogen compressor as a performance optimization tool, Applied Energy, Volume 323, 2022, 119628, ISSN 0306-2619. [CrossRef]

- Jinsheng Xiao, Min Hu, Pierre Bénard, Richard Chahine, Simulation of hydrogen storage tank packed with metal organic framework, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 38, Issue 29, 2013, Pages 13000-13010, ISSN 0360-3199. [CrossRef]

| 1 | Volume of porous media |

| 2 | Root Mean Square Error |

| 3 | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| Adsorbents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activated carbon (AC) | ||||

| Powder MOF-5 | ||||

| Compact MOF-5 |

| Properties | Activated carbon | Powder MOF-5 | Compact MOF-5 |

| Particle density | |||

| Specific heat | |||

| Conductivity | |||

| Bed porosity | |||

| Paricle diameter |

| Parameter | Value/Description |

| Initial temperature (T₀) | 302 K |

| Total mass of injection | 19.5 g |

| Ambient temperature Text | 302 K |

| Injection time | 953 s |

| Wall heat transfer coefficient | 36 W/m/K |

| Parameter | RMSE2 | MAPE3 | Maximum relative error |

| 2.4 10⁻⁴ | 2.16% | 3.24% | |

| 1.3 10⁻⁴ | 2.25% | 7.58% | |

| 1.82 | 0.15% | 0.10% | |

| 0.19 | 2.34% | 4.42% | |

| 2.174 | 0.54% | 1.4% | |

| 8.83 | 2.09% | 4.63% | |

| 1.019 | 0.30% | 0.46% |

| 273 | 200 | 0.012432268 |

| 273 | 400 | 0.012307034 |

| 273 | 600 | 0.012111843 |

| 273 | 800 | 0.012433435 |

| 273 | 1000 | 0.012316264 |

| 283 | 200 | 0.012410988 |

| 283 | 400 | 0.01228127 |

| 283 | 600 | 0.012130479 |

| 283 | 800 | 0.012249503 |

| 283 | 1000 | 0.012319771 |

| 293 | 200 | 0.012124952 |

| 293 | 400 | 0.012293844 |

| 293 | 600 | 0.012233828 |

| 293 | 800 | 0.012309072 |

| 293 | 1000 | 0.012339576 |

| 303 | 200 | 0.012392542 |

| 303 | 400 | 0.012196179 |

| 303 | 600 | 0.012094533 |

| 303 | 800 | 0.012031741 |

| 303 | 1000 | 0.012418507 |

| 313 | 200 | 0.012078094 |

| 313 | 400 | 0.012354711 |

| 313 | 600 | 0.012225714 |

| 313 | 800 | 0.012286743 |

| 313 | 1000 | 0.012346961 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).