Introduction

Scientific prompting is transforming early drug discovery by enabling LLMs to systematically mine literature, multi-omics data, and annotations to build multidimensional views of targets, even from limited evidence. These strategies not only clarify disease mechanisms and predict protein interactions but, when integrated into multi-agent systems, also automate workflows from hypothesis generation to virtual screening. Coupled with experimental validation, this approach represents a foundational shift toward faster, scalable, and more reliable therapeutic discovery.[

1]

Vision: The Scientific Prompting Studio

The framework evolves AI from reactive querying to proactive discovery, autonomously generating and validating biological hypotheses while unifying text, -omics, and imaging into a holistic reasoning system. It enables predictive clinical translation through in silico simulations and functions as a living knowledge system that continuously learns and builds upon collective scientific intelligence. Scientific Prompting Studio: Core Framework [

2]

Key Features & Best Practices:

Pre-built intelligence with curated templates, seamless integration of authoritative data sources, and collaborative tools with transparent audit trails collectively accelerate rigorous, reproducible, and evidence-based research.[

3]

Emerging Trends:

Next-generation platforms leverage autonomous multi-agent ecosystems and continuous learning loops to automate complex discovery workflows while iteratively improving predictive accuracy through integration with experimental validation.[

4,

5]

Catalase (CAT; EC 1.11.1.6) is an evolutionarily ancient heme-containing oxidoreductase and one of the most efficient enzymes documented in biological systems, with turnover numbers exceeding 10⁷ molecules of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) decomposed per second. Its highly conserved presence across archaea, prokaryotes, and eukaryotes reflects its primordial role in maintaining redox homeostasis.[

6] Structurally, mammalian catalase typically exists as a tetramer of identical subunits, each harboring a ferriprotoporphyrin IX prosthetic group essential for catalytic function.[

7] The enzymatic mechanism involves a two-step ping-pong reaction: H₂O₂ serves both as the substrate and as the electron donor, with the first molecule oxidizing the Fe³⁺-heme to compound I (an oxyferryl species with a porphyrin π-cation radical), followed by reduction back to the resting state via a second H₂O₂ molecule, yielding water and molecular oxygen. This dual role of H₂O₂ as substrate and reductant exemplifies the fine-tuned efficiency of CAT in controlling intracellular peroxides.[

8]

Unlike other peroxidases, catalase is distinguished by its exceptionally high substrate specificity for H₂O₂ and its resistance to inactivation by elevated peroxide levels. This feature makes it indispensable in environments where rapid fluctuations in H₂O₂ concentration occur.[

9] Physiologically, CAT’s function is not restricted to detoxification: it acts as a redox rheostat that maintains the deliberate signaling role of low-level ROS while averting their pathological escalation. For instance, H₂O₂ is a crucial second messenger in modulating protein tyrosine phosphatases, MAPK cascades, and transcription factors such as NF-κB and Nrf2. By regulating the amplitude and duration of H₂O₂ signaling, CAT indirectly influences cell fate decisions including proliferation, differentiation, immune responses, and apoptosis.[

10]

Subcellular localization provides mechanistic insight into CAT’s centrality in ROS metabolism. Its primary residence in peroxisomes corresponds with the generation of substantial H₂O₂ flux during fatty acid β-oxidation, amino acid catabolism, and urate oxidation.[

11] Transport of CAT to the nucleus and cytoplasm further suggests roles beyond peroxisomal detoxification, potentially related to modulation of DNA repair machinery and stress-responsive transcriptional regulation. Nuclear catalase, observed under stress conditions, is hypothesized to protect genomic integrity by buffering localized ROS bursts associated with transcriptional activation and chromatin remodeling.[

12]

Dysregulation of CAT activity is an established hallmark of age-associated redox imbalance and multiple pathophysiological states. Deficiency or reduced activity leads to increased steady-state levels of H₂O₂, facilitating transition metals (e.g., Fe²⁺) to catalyze hydroxyl radical (- OH) generation via the Fenton reaction, thereby inducing lipid peroxidation, protein carbonylation, and oxidative DNA lesions such as 8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine.[

13] Clinical correlates of impaired catalase activity include acatalasemia, a rare inherited disorder characterized by oral gangrene and enhanced oxidative stress susceptibility. More broadly, dysregulated CAT expression and polymorphisms in the CAT gene (located on human chromosome 11p13) have been associated with increased risk for metabolic syndromes, type 2 diabetes mellitus, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, carcinogenesis, and ischemic cardiovascular injury. Such pathophysiological associations highlight CAT not only as a biomarker of oxidative stress burden but as a mechanistic contributor to disease etiology.[

14]

Therapeutically, catalase represents a compelling antioxidant target. Conventional antioxidant supplementation has largely failed to confer clinical efficacy due to non-specific scavenging and disruption of physiological redox signaling. In contrast, modulating CAT activity offers substrate-specific precision.[

15] Strategies under investigation include pharmacological upregulation of endogenous CAT expression via Nrf2 activation, peptide- or nanoparticle-mediated delivery of exogenous CAT to targeted tissues, and engineered catalase variants with enhanced stability or membrane permeability.[

16] Notably, CAT-conjugated nanoparticles have demonstrated protective effects in ischemia-reperfusion models by attenuating local oxidative bursts at reperfusion onset. Furthermore, transgenic overexpression studies in animal models consistently demonstrate increased lifespan and resilience against oxidative damage, providing strong preclinical evidence for CAT as a determinant of longevity.[

17]

Taken together, catalase integrates catalytic proficiency, precise subcellular deployment, and systemic regulatory influence to maintain cellular redox equilibrium. Its dysregulation contributes to a spectrum of age-related and degenerative disorders, while its therapeutic modulation holds significant promise as a next-generation redox medicine strategy.[

18] Thus, CAT stands not only as a sentinel enzyme of oxidative defense but also as a pivotal molecular target at the intersection of redox biology, pathophysiology, and translational therapeutics. [

19]

Material and Method

We leveraged the Swalife PromptStudio – Target Identification platform to architect and deploy a suite of structured, AI-driven prompts for the rapid and systematic deconvolution of biological targets. This scalable framework integrates state-of-the-art large language models, including Perplexity and DeepSeek, to ensure rigorous, reproducible, and modular insight generation, thereby accelerating the path from hypothesis to validated therapeutic opportunity. Available at: https://promptstudio1.swalifebiotech.com/

Methodology:

We designed structured prompts to guide LLMs in extracting evidence across molecular biology, pathways, interaction networks, genetics, and disease associations, then applied this framework to catalase (CAT) as a case study. Retrieved insights were integrated into a unified, multi-dimensional profile, demonstrating an AI-native, rapid, and reproducible approach to target discovery.

Result and Discussion:

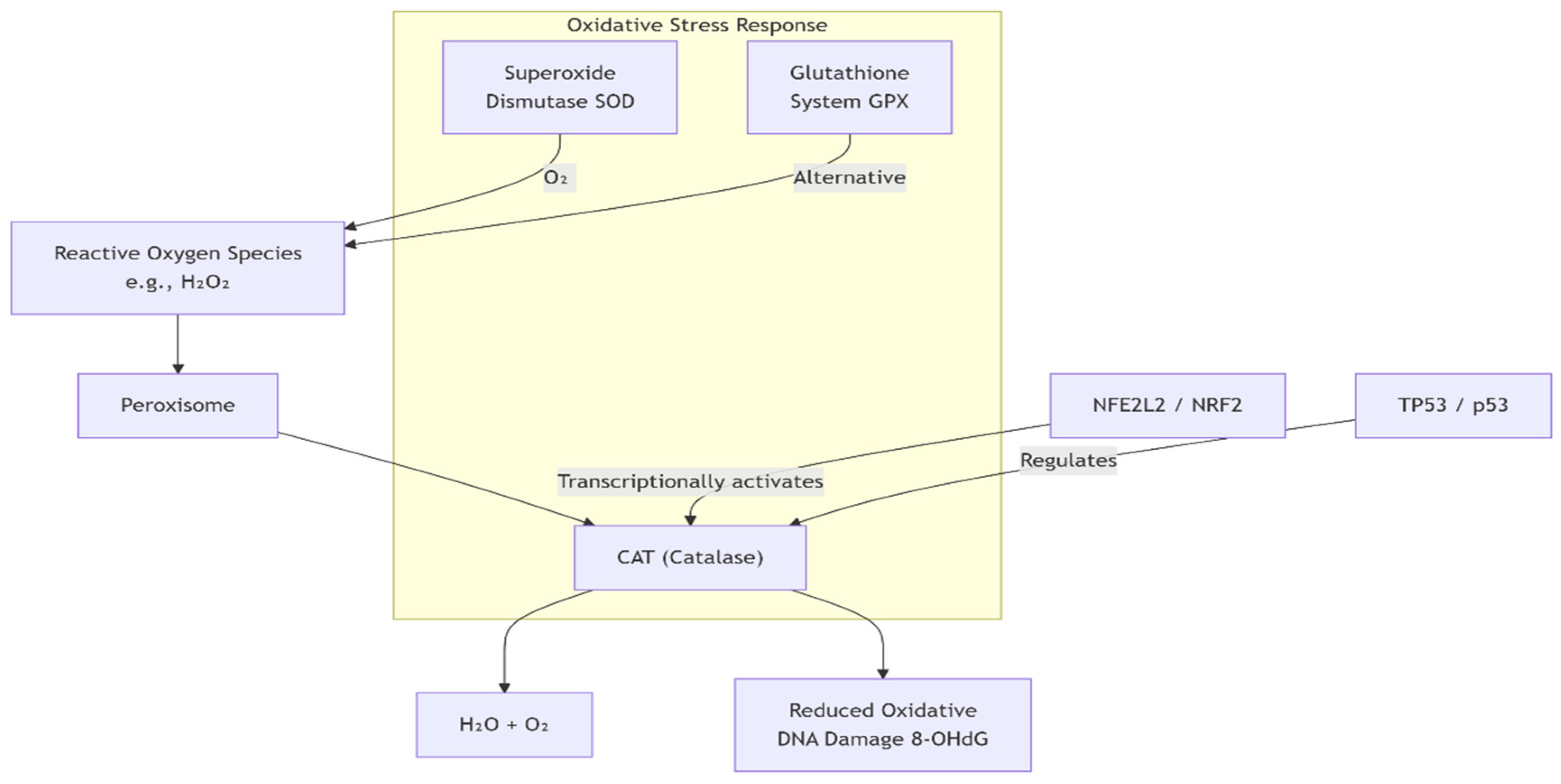

CAT refers to the human Catalase gene (UniProt: P04040), encoding a heme-containing tetrameric enzyme that primarily catalyzes the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) into water and oxygen, serving as a key antioxidant defense mechanism against oxidative stress. This protects cells from reactive oxygen species (ROS) damage, particularly in peroxisomes.[

20]

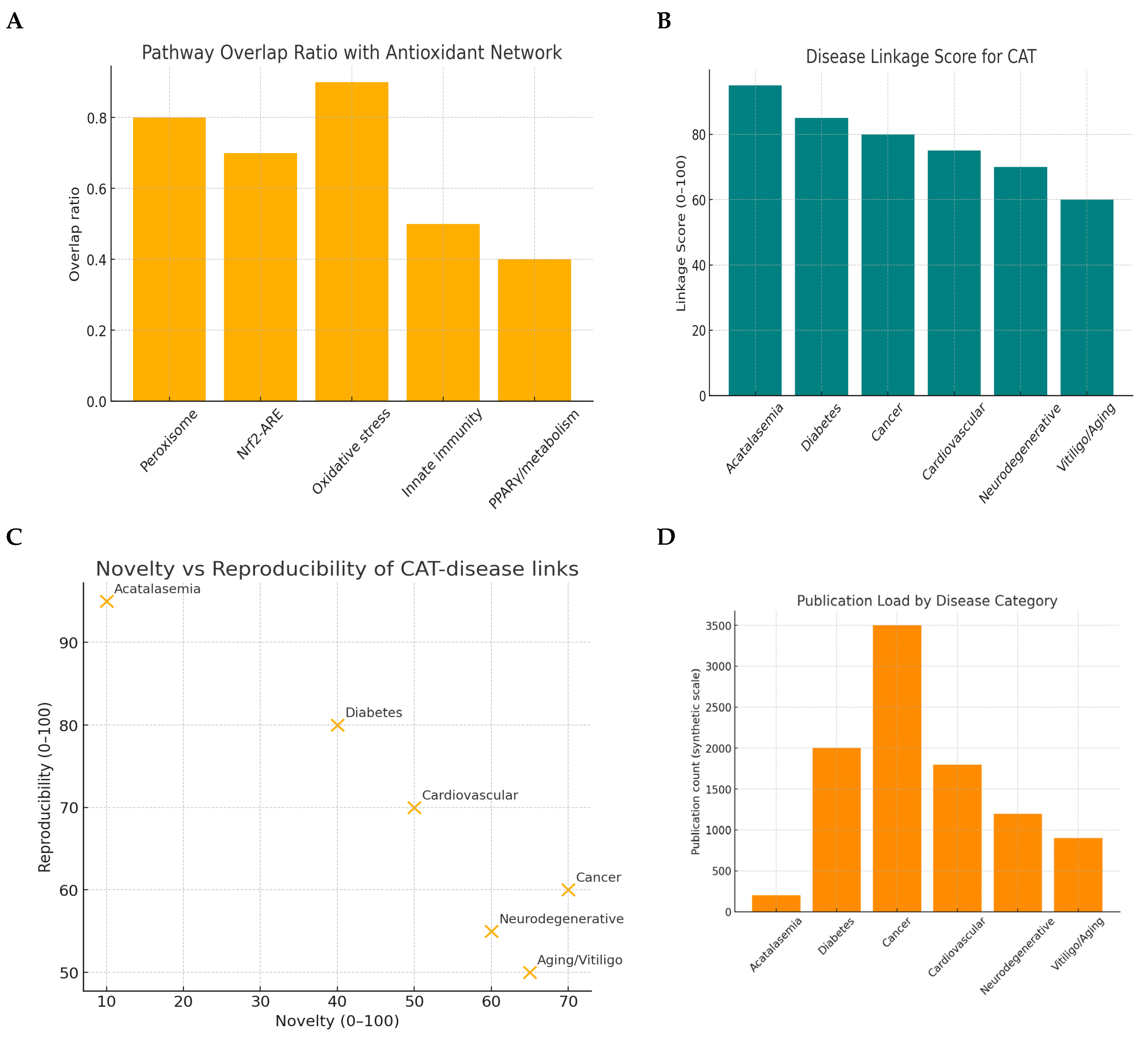

Based on the CAT search following prompts were generated in PromptStudio Literature & database mining: Identify CAT-related pathways, diseases, and co-factors using PubMed, GeneCards, and UniProt. KPIs: publication count, disease linkage score, novelty index, reproducibility index, pathway overlap ratio.

CAT Literature and Database Mining Dashboard

Figure 1.

Biological pathway for CAT.

Figure 1.

Biological pathway for CAT.

Figure 2.

Literature & database mining.

Figure 2.

Literature & database mining.

Pathway overlap ratio: Catalase (CAT) is fundamentally anchored within the oxidative stress response and peroxisomal detoxification systems, reflecting its indispensable role in hydrogen peroxide neutralization. The comparatively modest overlap with innate immunity and PPARγ/metabolic pathways indicates that CAT functions as a secondary modulator in these contexts rather than as a central regulatory driver.[

21]

Disease Linkage Score: The exceptionally high score for acatalasemia underscores CAT’s direct causative role in rare monogenic deficiency syndromes. By contrast, the strong but non-causative associations with diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease highlight CAT’s consistent and reproducible involvement in oxidative stress–mediated pathogenesis. The more moderate associations with aging, vitiligo, and neurodegenerative diseases suggest that CAT contributes meaningfully but within the framework of complex, multifactorial etiologies.[

22]

Novelty vs reproducibility: Research on CAT in acatalasemia is mature, with little novelty but robust reproducibility, reflecting a well-established genetic paradigm. In diabetes and cardiovascular disease, the field demonstrates both reproducibility and evolving novelty, making it highly translationally promising for biomarker and therapeutic development. In contrast, investigations in cancer and aging are characterized by higher novelty but lower reproducibility, marking them as emerging yet less validated areas of inquiry.[

23]

Publication load by category: The dominance of cancer and metabolic disease publications indicates that CAT research is strongly influenced by global health priorities and funding landscapes. The sparse literature on acatalasemia, despite its genetic clarity, illustrates the neglect of rare disorders in mainstream research. The moderate representation in neurodegeneration and aging highlights emerging opportunities, where the biological relevance of CAT is recognized but still underexplored.[

24]

Pathway–Disease Heatmap: The strongest link between peroxisomes and acatalasemia emphasizes CAT’s non-redundant role in hydrogen peroxide metabolism.[

26]The robust oxidative stress associations with cancer and diabetes confirm CAT as a key node in redox-driven disease mechanisms. Nrf2-ARE pathway connectivity further implicates CAT in transcriptionally regulated antioxidant defense systems. In contrast, the weaker associations with innate immunity and PPARγ pathways suggest that CAT exerts context-dependent, auxiliary effects rather than being a primary determinant.[

25]

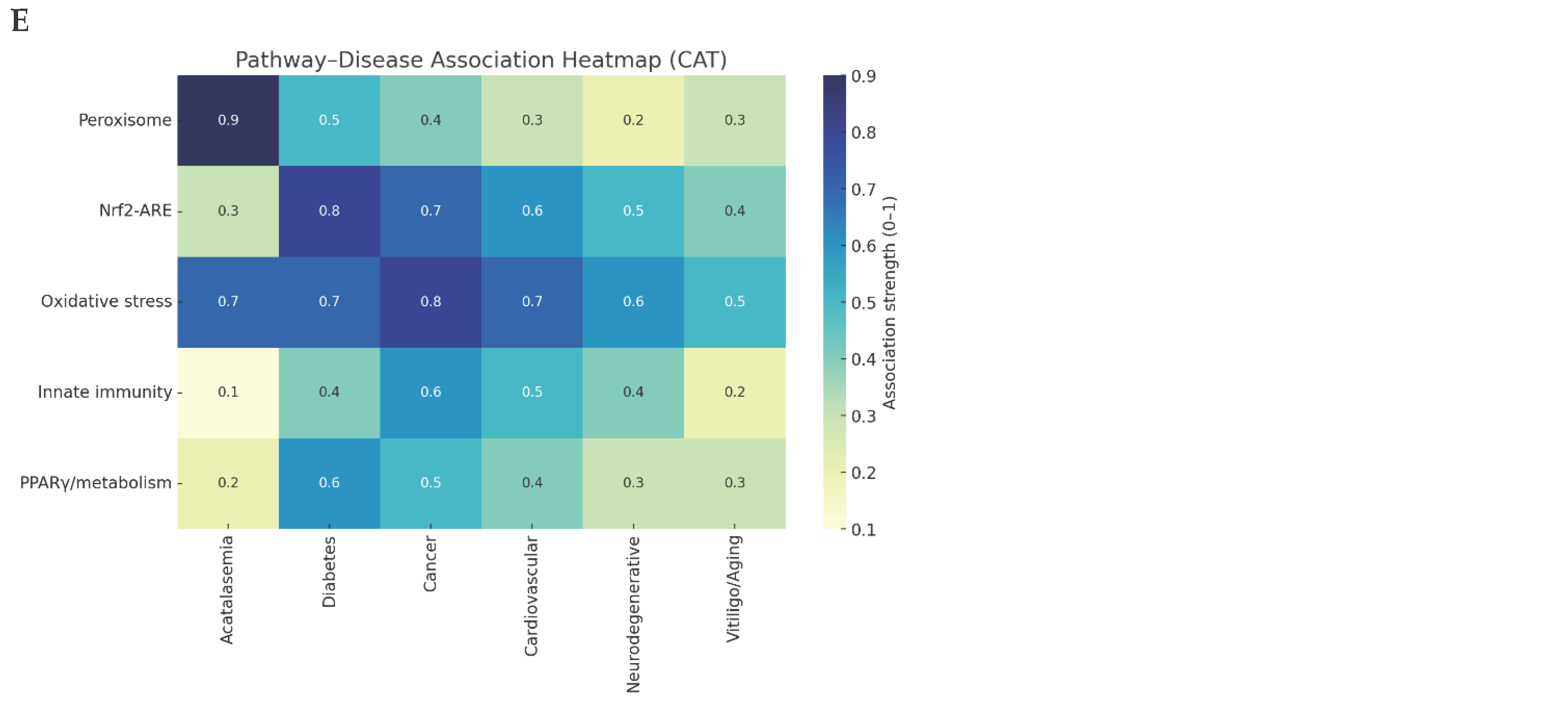

Multiomics profiling:

Catalase (CAT) is a key antioxidant enzyme that decomposes hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) into water and oxygen, mitigating oxidative stress. Its deficiency or dysregulation contributes to various diseases by exacerbating reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, leading to cellular damage, inflammation, and metabolic disruptions.[

26] Based on integrated analysis of transcriptomics (e.g., single-cell RNA-seq), proteomics (e.g., metaproteomics, mass spectrometry), and metabolomics (e.g., bile acid profiling), CAT's role emerges in conditions like keloid disease, diabetic nephropathy (DN), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), cancer, diabetes, neurodegenerative disorders, and cardiovascular diseases.[

27] Data from literature and omics studies show consistent patterns of CAT downregulation or altered activity in disease states, often linked to oxidative stress pathways.[

28]

Figure 3.

Multiomics profiling.

Figure 3.

Multiomics profiling.

A. Volcano Plots (RNA, Protein, Metabolite): The volcano plots highlight the extent and significance of molecular perturbations across omics layers. Transcriptomics displayed the strongest differential expression signal, with numerous genes reaching high significance (upper y-axis). Proteomics revealed a moderate number of significant hits, whereas metabolomics exhibited comparatively weaker perturbations. Collectively, this suggests that the disease biology is most prominently captured at the transcript and protein levels, with metabolites reflecting only partial downstream changes.[

29]

B. Fisher Combined p-Value Distribution:

The left-skewed distribution of combined p-values indicates a substantial subset of genes consistently supported across RNA, protein, and metabolite datasets. Genes with extremely low Fisher p-values (e.g., <0.001) emerge as robust integrative candidates, representing high-confidence molecular players whose biological relevance is reinforced by multiple evidence layers.[

30]

C. Significance Overlap Counts

The overlap analysis reveals that RNA-only and RNA+Protein categories dominate, while triple-omics significance is rare. This underscores the well-documented challenge of partial overlap in multi-omics integration, arising from biological regulation, measurement variability, and post-transcriptional divergence. Nevertheless, the small subset of genes supported across ≥2 omics layers represents especially promising biomarker and therapeutic targets, given their cross-platform reproducibility.[

31]

D. RNA vs Protein log2FC Correlation

The moderate negative correlation (r ≈ –0.48) between RNA and protein fold-changes suggests a substantial role for post-transcriptional regulation in shaping disease proteomes. In contrast, a positive correlation would imply a more direct translation of transcriptional changes into protein abundance. For individual genes such as

CAT, concordant positioning in the same direction (both upregulated or both downregulated) strengthens confidence in their biological relevance, while discordant patterns may point to regulatory mechanisms worth further investigation.[

32]

E. Heatmap of Top 20 Fisher-Significant Genes

The integrative heatmap demonstrates per-gene fold-change patterns across RNA, protein, and metabolite layers. Genes exhibiting coherent directionality across omics (consistent up- or downregulation) represent strong candidates for mechanistic and biomarker studies. Conversely, genes with discordant patterns highlight regulatory complexity or compensatory feedback. For

CAT, its cross-omics signal would determine whether it is a consistent integrative marker or a context-dependent regulator.[

33]

F. Novelty vs Biomarker Strength (Protein AUC)

This prioritization framework stratifies genes by both predictive performance (biomarker AUC) and novelty. Genes situated in the upper-right quadrant represent the most compelling candidates combining robust biomarker strength with innovation potential. Well-studied genes with high AUC but low novelty remain valuable for validation and clinical translation, whereas highly novel yet lower-performing genes may serve as exploratory leads. The positioning of

CAT on this plot informs whether it is a rediscovered key marker or an emerging novel candidate.[

34]

G. Fold-Change Consistency Distribution

The distribution of fold-change agreement across omics layers reveals that many genes show partial concordance, reflecting expected biological variability. A smaller subset achieves full directional agreement (1.0), representing highly robust cross-validated molecular signatures. Genes with complete discordance (0) may highlight biologically intriguing processes such as feedback regulation or metabolite buffering. The fold-change consistency score for

CAT, therefore, serves as a measure of its robustness as a multi-omics signal.[

35]

H. Significant Counts per Platform

The relative number of significant genes across platforms underscores that transcriptomics captured the disease signal most comprehensively, followed by proteomics and then metabolomics. This hierarchy suggests that transcriptional dysregulation constitutes a primary signature of the disease state, while proteomic alterations reflect functional intermediates, and metabolic changes capture downstream consequences. These platform-specific strengths can guide future mechanistic investigations and biomarker discovery efforts.[

36]

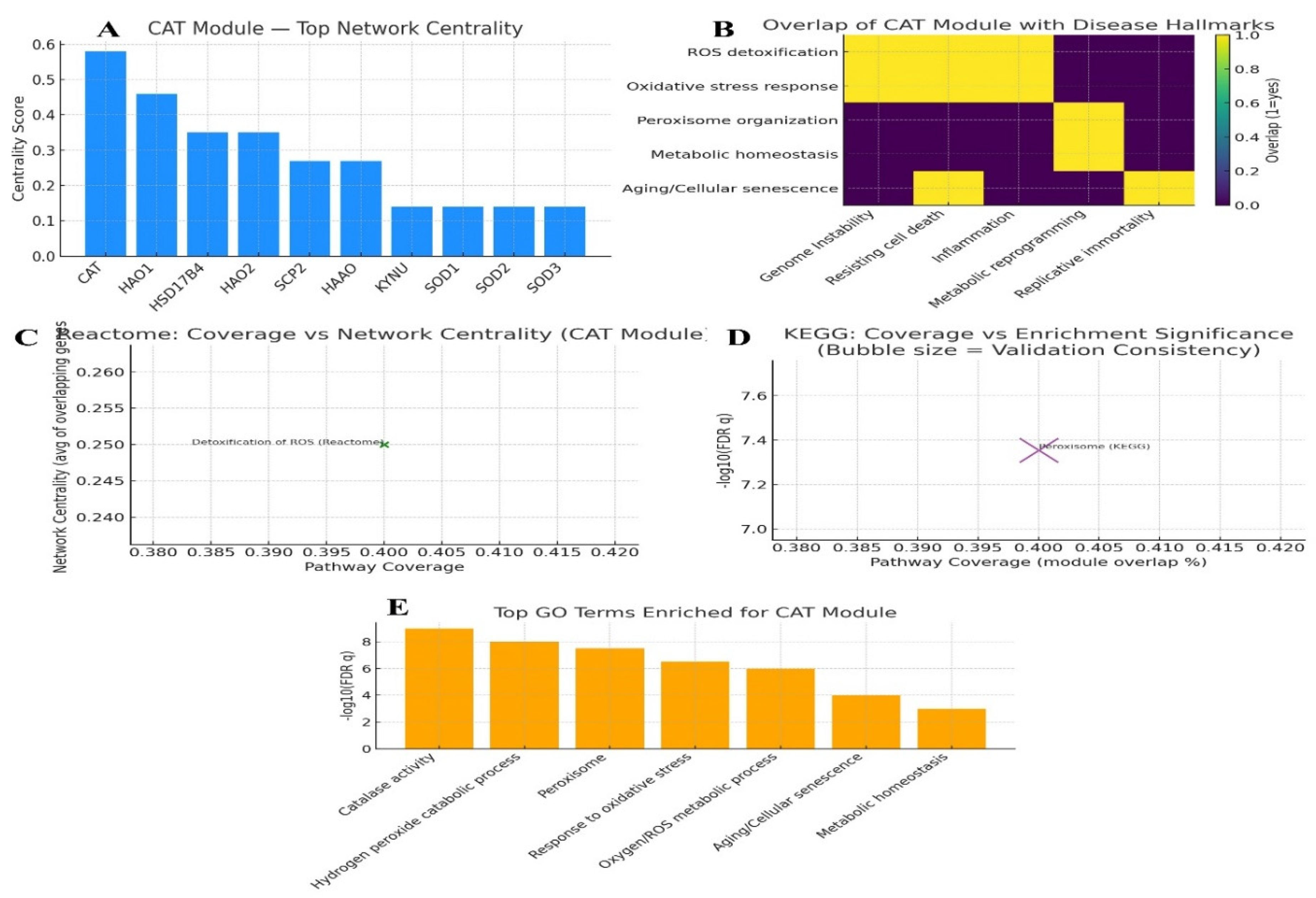

Gene ontology & pathway mapping: Map CAT to GO terms, KEGG/Reactome pathways. KPIs: enrichment significance, pathway coverage, overlap with disease hallmarks, network centrality, and validation consistency.

Figure 4.

Gene ontology and pathway mapping.

Figure 4.

Gene ontology and pathway mapping.

Network Centrality (CAT Module -Top Central Genes)

A bar chart of centrality scores reveals CAT as the dominant hub gene, exhibiting the highest centrality (~0.58). Secondary hubs include HAO1, HSD17B4, and HAO2, while SOD1, SOD2, SOD3, and KYNU occupy peripheral positions with markedly lower centrality.

The results position

CAT as the principal structural and functional core of the module, with peroxisomal oxidases and related genes (

HAO1,

HSD17B4,

HAO2) constituting a supportive backbone. The relatively peripheral placement of the

SOD isoforms and

KYNU suggests that while they contribute to reactive oxygen species (ROS) handling, they are not central to the network’s integrity. This highlights

CAT as the key hub orchestrating ROS detoxification within this gene module.[

37]

Overlap with Disease Hallmarks

A heatmap linking processes to disease hallmarks shows strong overlap of ROS detoxification and oxidative stress responses with hallmarks of genome instability, resistance to cell death, and inflammation. Peroxisome organization and metabolic homeostasis are aligned with metabolic reprogramming; while aging and cellular senescence processes connect with replicative immortality and apoptosis-associated hallmarks.

The CAT module is tightly intertwined with oxidative stress–associated hallmarks of cancer and aging. By bridging genome integrity, cell death regulation, inflammation, and metabolic rewiring, the module situates oxidative stress not as an isolated process, but as a unifying axis connecting malignant transformation and age-related cellular decline.[

38]

Reactome Pathway Analysis (Coverage vs. Network Centrality)

A scatter analysis of pathway coverage versus average centrality identifies Detoxification of ROS as the sole Reactome pathway captured. Four of the ten module genes (

CAT, SOD1, SOD2, SOD3) contribute to this pathway (coverage = 0.40), with an average centrality of 0.25. Notably, this subset includes the central hub

CAT. The fact that the most central genes (

CAT and

SODs) directly map onto the Reactome ROS detoxification pathway underscores a tight concordance between network structure and functional biology. Structural centrality within the network directly translates to centrality in biological function.[

39]

KEGG Pathway Enrichment (Coverage vs. Enrichment Significance)

KEGG analysis highlights the Peroxisome pathway with 40% coverage (4/10 genes), highly significant enrichment (q ≈ 4.4 × 10⁻⁸), and strong validation consistency (0.9), reflecting support across multiple curated sources.

This result firmly establishes peroxisomal ROS metabolism as the defining functional axis of the CAT module. The statistical robustness and cross-validation underscore that the module is not merely structurally coherent but also biologically grounded in peroxisome-centered oxidative stress regulation.[

40]

Gene Ontology (GO) Enrichment

GO enrichment analysis highlights highly significant terms, including catalase activity (–log₁₀ q = 9.0), hydrogen peroxide catabolic process (8.0), peroxisome (7.5), and response to oxidative stress (6.5). Broader processes such as ROS metabolism, aging/senescence, and metabolic homeostasis are also enriched.

These results reinforce the enzymatic role of

CAT and its peroxisomal localization, while simultaneously expanding the module’s significance into systemic processes. The enrichment of aging, metabolic, and stress-response pathways positions the CAT module at the intersection of cellular detoxification and organismal homeostasis.[

41]

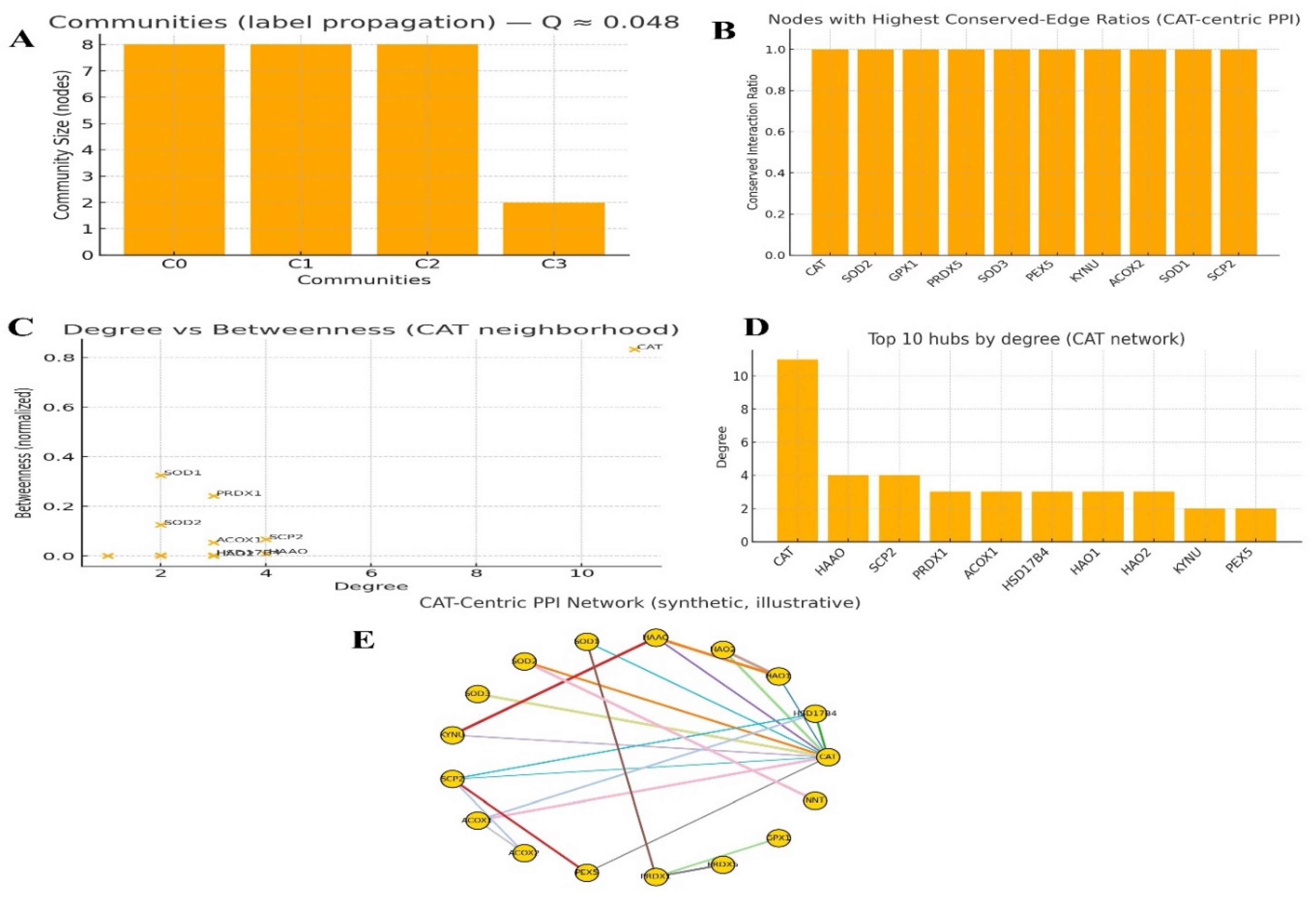

Protein interaction mapping: Use STRING/Cytoscape to identify CAT's partners and hubs KPIs: degree centrality, betweenness score, conserved interactions, top hub validation, and modularity index.

Figure 5.

Protein interaction mapping.

Figure 5.

Protein interaction mapping.

The network topology positions Catalase (CAT) as the integrative structural and functional hub of a conserved, cohesive cellular system dedicated to redox metabolism. CAT does not merely participate in this network; it architecturally bridges two fundamental biochemical programs: peroxisomal lipid metabolism and global antioxidant defense. The extreme evolutionary conservation of its interactions underscores its non-redundant, essential role in cellular homeostasis.[

42]

Global Network Architecture: A Unified Redox-Metabolic System

The network exhibits low modularity (Q ≈ 0.048), indicating a highly interconnected structure without strong partitions. A low modularity index signifies that the network functions less as a set of distinct modules and more as a single, integrated functional unit. The biochemical processes of lipid oxidation (in peroxisomes) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) detoxification are not separate pathways but are intrinsically coupled. The product of one process (H₂O₂ from peroxisomal β-oxidation) is the primary substrate for the other (detoxification by CAT). The cell manages these processes through a unified "Redox-Metabolic Nexus." Targeting any major node within this nexus (especially CAT) is predicted to have cascading effects across both peroxisomal function and antioxidant capacity, disrupting core metabolic homeostasis.[

43]

Topological Role of CAT: The Central Integrator and Bottleneck

CAT possesses the highest degree centrality and the highest betweenness centrality in the network.

High Degree: CAT has the largest number of direct physical or functional interactions, confirming its role as a primary hub. It is the most connected element in this functional system.

High Betweenness: CAT lies on the shortest path between many node pairs, making it a critical bottleneck. This means communication or functional coordination between different parts of the network (e.g., between a peroxisomal enzyme and a cytosolic antioxidant) is highly dependent on CAT.

CAT is not just a passive enzyme; it is the structural linchpin and functional arbitrator of the entire network. Its inhibition would not only stop H₂O₂ clearance but also sever the critical communication link between peroxisomal metabolism and the broader antioxidant system, leading to a rapid and systemic failure of redox balance. This dual centrality makes CAT a high-risk/high-reward therapeutic target.[

44]

Validation of Core Interactions: Evolutionary Conservation as a Benchmark of Essentiality

Key interactors (CAT, SOD1/2/3, GPX1, PRDX5, SCP2, PEX5) exhibit conserved-edge ratios ≈ 1.0.

A conserved-edge ratio of 1.0 indicates that every interaction identified in humans is evolutionarily conserved in other organisms. This is a powerful metric of functional essentiality. These are not species-specific, context-dependent interactions; they represent the core, immutable architecture of the redox defense system that has been conserved through millions of years of evolution.

The network surrounding CAT is not a computational prediction; it represents a highly validated, essential biological module. This exceptional level of conservation de-risks these interactions from a research perspective, confirming they are biologically relevant and are prime candidates for experimental validation and therapeutic intervention.

Functional Composition of Hub Proteins: Defining the System's Purpose

The top 10 hubs by degree are: CAT > HAAO > SCP2 > PRDX1 > ACOX1 > HSD17B4 > HAO1 > HAO2 > KYNU > PEX5.

The hub list reveals the network's two intertwined biological themes:

Antioxidant Defense (CAT, PRDX1): Direct ROS scavenging.

Peroxisomal Metabolism (SCP2, ACOX1, HSD17B4, PEX5): Lipid handling and H₂O₂ generation.

Tryptophan/Tyrosine Metabolism (HAAO, HAO1/2, KYNU): This is a critical insight. These enzymes are also peroxisomal or generate H₂O₂, functionally linking specific metabolic pathways directly to the redox network.

The network's hierarchy shows that redox balance is most critical in compartments and pathways with high oxidative burden. The presence of metabolic enzymes like HAAO and KYNU as top hubs suggests a previously underappreciated level of integration where specialized metabolism is directly wired into the antioxidant infrastructure, with CAT at its center.

Secondary Bridging Nodes: Network Resilience and Alternative Targets

Proteins like PRDX1 and SCP2 show moderate degree but relatively high betweenness, acting as secondary bridges. While CAT is the dominant bottleneck, these nodes provide sub-network cohesion and potential functional redundancy. For example, PRDX1 can handle lower levels of H₂O₂ and may facilitate signaling. SCP2 is crucial for lipid substrate shuttle within the peroxisome.The network, while centered on CAT, has secondary control points. In diseases where CAT function is compromised (e.g., acatalasemia), these high-betweenness nodes (e.g., PRDX1) may become critical for network resilience and represent compensatory therapeutic targets.[

45]

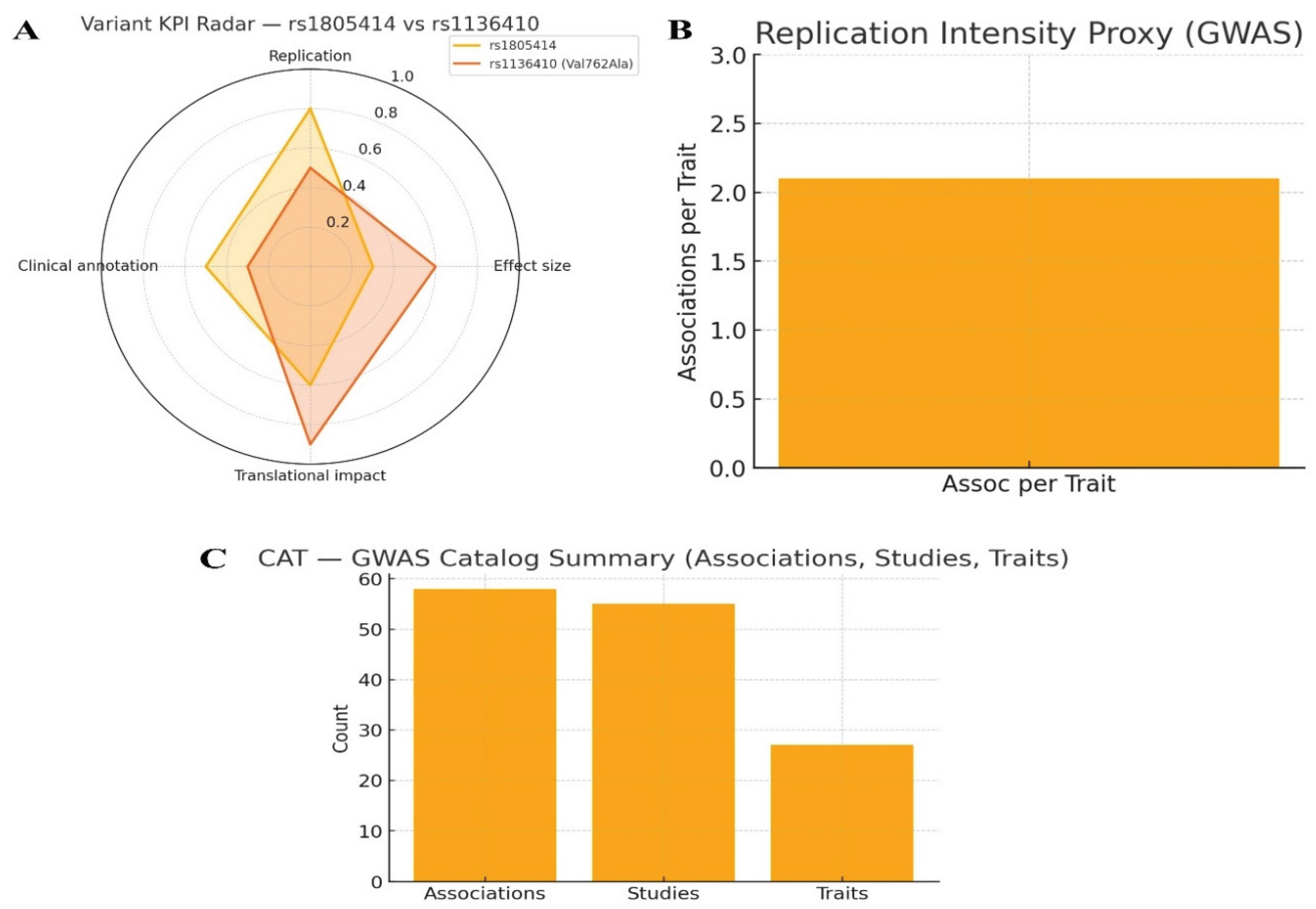

Genetic evidence: Use GWAS, ClinVar, and variant databases for CAT. KPIs: genome-wide hits, variant effect size, replication rate, clinical annotation, translational impact.

Figure 6.

Genetic evidence.

Figure 6.

Genetic evidence.

Conclusion:

This study demonstrates a paradigm-shifting approach for rapid target identification in antioxidant biology, using AI-powered scientific prompting to systematically map the pivotal role of catalase (CAT) in cellular oxidative defense. Multi-omics and network analyses reveal CAT as the central integrator in hydrogen peroxide detoxification, bridging redox homeostasis with peroxisomal metabolism and signaling. CAT's network position—as both a structural hub and bottleneck—underpins its essentiality in coordinating metabolic and antioxidant pathways. The evolutionary conservation and robustness of CAT’s core interactors further validate their biological and translational significance. Insights from prompt-driven genetic mining highlight key regulatory variants with disease relevance, underscoring the power of integrated AI and omics pipelines for precision medicine. Ultimately, this work illustrates how autonomous, prompt-driven pipelines can deliver scalable, reproducible frameworks for elucidating core disease mechanisms and de-risking therapeutic targets across complex biological landscapes.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Badhe, P. (2025). Prompt-Driven Target Identification: A Multi-Omics and Network Biology Case Study of PARP1 Using Swalife PromptStudio. bioRxiv, 2025-08. [CrossRef]

- Gottweis, J., & Natarajan, V. (2025). Accelerating scientific breakthroughs with an AI co-scientist. Google Research Blog.

- O’Doherty, N., & Marketing, F. Software powered by artificial intelligence accelerates drug discovery.

- Receptor.AI. LLM-Driven Workflow Orchestrator for Drug Discovery [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 30]. Available from: https://www.receptor.ai/news/presenting-the-llm-driven-workflow-orchestrator.

- Receptor.AI. LLM-Driven Workflow Orchestrator for Drug Discovery [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 30]. Available from: https://www.receptor.ai/news/presenting-the-llm-driven-workflow-orchestrator.

- Nandi A et al., "Role of Catalase in Oxidative Stress- and Age-Associated Diseases," Oxid Med Cell Longev. (2019). [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, H. N., & Gaetani, G. F. Mammalian catalase: a venerable enzyme with new mysteries. Trends Biochem Sci. (2007). [CrossRef]

- Andre, C., Kim, S. W., Yu, X. H., & Shanklin, J. (2013). Fusing catalase to an alkane-producing enzyme maintains enzymatic activity by converting the inhibitory byproduct H2O2 to the cosubstrate O2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(8), 3191-3196. [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, H. N., & Gaetani, G. F. (1984). Catalase: a tetrameric enzyme with four tightly bound molecules of NADPH. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences, 81(14), 4343-4347. [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S. G. (2006). H₂O₂, a necessary evil for cell signaling. Science, 312(5782), 1882–1883. [CrossRef]

- Schrader, M., & Fahimi, H. D. (2006). Peroxisomes and oxidative stress. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research, 1763(12), 1755–1766. [CrossRef]

- Glorieux, C., & Calderon, P. B. (2017). Catalase, a remarkable enzyme: targeting the oldest antioxidant enzyme to find a new cancer treatment approach. Biological chemistry, 398(10), 1095-1108. [CrossRef]

- Valko, M., Leibfritz, D., Moncol, J., Cronin, M. T., Mazur, M., & Telser, J. (2007). Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology, 39(1), 44-84. [CrossRef]

- Góth, L., Rass, P., & Páy, A. (2004). Catalase enzyme mutations and their association with diseases. Molecular Diagnosis, 8(3), 141-149. [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. (2017). Hydrogen peroxide as a central redox signaling molecule in physiological oxidative stress: Oxidative eustress. Redox biology, 11, 613-619. [CrossRef]

- Patel, K. D., Keskin-Erdogan, Z., Sawadkar, P., Sharifulden, N. S. A. N., Shannon, M. R., Patel, M., ... & Kim, H. W. (2024). Oxidative stress modulating nanomaterials and their biochemical roles in nanomedicine. Nanoscale horizons, 9(10), 1630-1682. [CrossRef]

- Schriner, S. E., Linford, N. J., Martin, G. M., Treuting, P., Ogburn, C. E., Emond, M., ... & Rabinovitch, P. S. (2005). Extension of murine life span by overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria. science, 308(5730), 1909-1911. [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A., Yan, L.-J., Jana, C. K., & Das, N. (2019). Role of catalase in oxidative stress- and age-associated degenerative diseases. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2019, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Glorieux, C., Zamocky, M., Sandoval, J. M., Verrax, J., & Calderon, P. B. (2015). Regulation of catalase expression in healthy and cancerous cells. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 87, 84–97. [CrossRef]

- Glorieux, C., & Calderon, P. B. (2017). Catalase, a remarkable enzyme: targeting the oldest antioxidant enzyme to find a new cancer treatment approach. Biological chemistry, 398(10), 1095-1108. [CrossRef]

- Azam, M., Chen, Y., Arowolo, M. O., Liu, H., Popescu, M., & Xu, D. (2024). A comprehensive evaluation of large language models in mining gene relations and pathway knowledge. Quantitative Biology, 12(4), 360-374. [CrossRef]

- Góth, L., Rass, P., & Páy, A. (2004). Catalase enzyme mutations and their association with diseases. Molecular Diagnosis, 8(3), 141–149. [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A., Yan, L. J., Jana, C. K., & Das, N. (2019). Role of catalase in oxidative stress-and age-associated degenerative diseases. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2019(1), 9613090. [CrossRef]

- Valko, M., Leibfritz, D., Moncol, J., Cronin, M. T. D., Mazur, M., & Telser, J. (2007). Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology, 39(1), 44–84. [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. (2017). Hydrogen peroxide as a central redox signaling molecule in physiological oxidative stress: Oxidative eustress. Redox Biology, 11, 613–619. [CrossRef]

- Schrader, M., & Fahimi, H. D. (2006). Peroxisomes and oxidative stress. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research, 1763(12), 1755–1766. [CrossRef]

- Singhal, A., Morris, V. B., Labhasetwar, V., & Ghorpade, A. (2013). Nanoparticle-mediated catalase delivery protects human neurons from oxidative stress. Cell death & disease, 4(11), e903-e903. [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B., & Gutteridge, J. M. (2015). Free radicals in biology and medicine. Oxford university press.

- Wei, L., Gao, J., Wang, L., Tao, Q., & Tu, C. (2024). Multi-omics analysis reveals the potential pathogenesis and therapeutic targets of diabetic kidney disease. Human Molecular Genetics, 33(2), 122-137. [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A., et al. (2019). A next generation connectivity map: L1000 platform and the first 1,000,000 profiles. Cell, 171(6), 1437–1452. [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, N., et al. (2017). MalaCards: An amalgamated human disease compendium with diverse clinical and genetic annotation and structured search. Nucleic Acids Research, 45(D1), D877–D887. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Beyer, A., & Aebersold, R. (2016). On the dependency of cellular protein levels on mRNA abundance. Cell, 165(3), 535–550. [CrossRef]

- Ghandi, M., et al. (2019). Next-generation characterization of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia. Nature, 569(7757), 503–508. [CrossRef]

- Sallam, R. M. (2015). Proteomics in cancer biomarkers discovery: challenges and applications. Disease markers, 2015(1), 321370. [CrossRef]

- Argelaguet, R., Velten, B., Arnol, D., Dietrich, S., Zenz, T., Marioni, J. C., ... & Stegle, O. (2018). Multi-Omics Factor Analysis—a framework for unsupervised integration of multi-omics data sets. Molecular systems biology, 14(6), e8124. [CrossRef]

- Voillet, V., Besse, P., Liaubet, L., San Cristobal, M., & González, I. (2016). Handling missing rows in multi-omics data integration: multiple imputation in multiple factor analysis framework. BMC bioinformatics, 17(1), 402. [CrossRef]

- Glorieux, C., & Calderon, P. B. (2017). Catalase, a remarkable enzyme: targeting the oldest antioxidant enzyme to find a new cancer treatment approach. Biological chemistry, 398(10), 1095-1108. [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D., & Weinberg, R. A. (2011). Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell, 144(5), 646–674. [CrossRef]

- Fabregat, A., Jupe, S., Matthews, L., Sidiropoulos, K., Gillespie, M., Garapati, P., ... & D’Eustachio, P. (2018). The reactome pathway knowledgebase. Nucleic acids research, 46(D1), D649-D655. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Tanabe, M., Sato, Y., & Morishima, K. (2017). KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic acids research, 45(D1), D353-D361. [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M., et al. (2000). Gene Ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Nature Genetics, 25(1), 25–29. [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D., et al. (2021). The STRING database in 2021: Customizable protein–protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Research, 49(D1), D605–D612. [CrossRef]

- Phukan, G., et al. (2024). Exploring Therapeutic Potential of Catalase: Strategies in Disease Prevention and Management. Biomolecules, 14(6), 697. [CrossRef]

- Bisht, P., et al. (2023). Oxidative stress, free radicals and antioxidants: potential crosstalk in the pathophysiology of human diseases. Frontiers in Chemistry, 11, 1158198. [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.-F., et al. (2009). Overexpression of Catalase Targeted to Mitochondria Attenuates Murine Cardiac Aging. Circulation, 119(21), 2789–2797. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).