Submitted:

09 October 2025

Posted:

10 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

EGFR Structure and Normal Function

EGFR Dysregulation in Breast Cancer

EGFR in Breast Cancer Subtypes

Challenges and Future Directions

Material and Method

Methodology

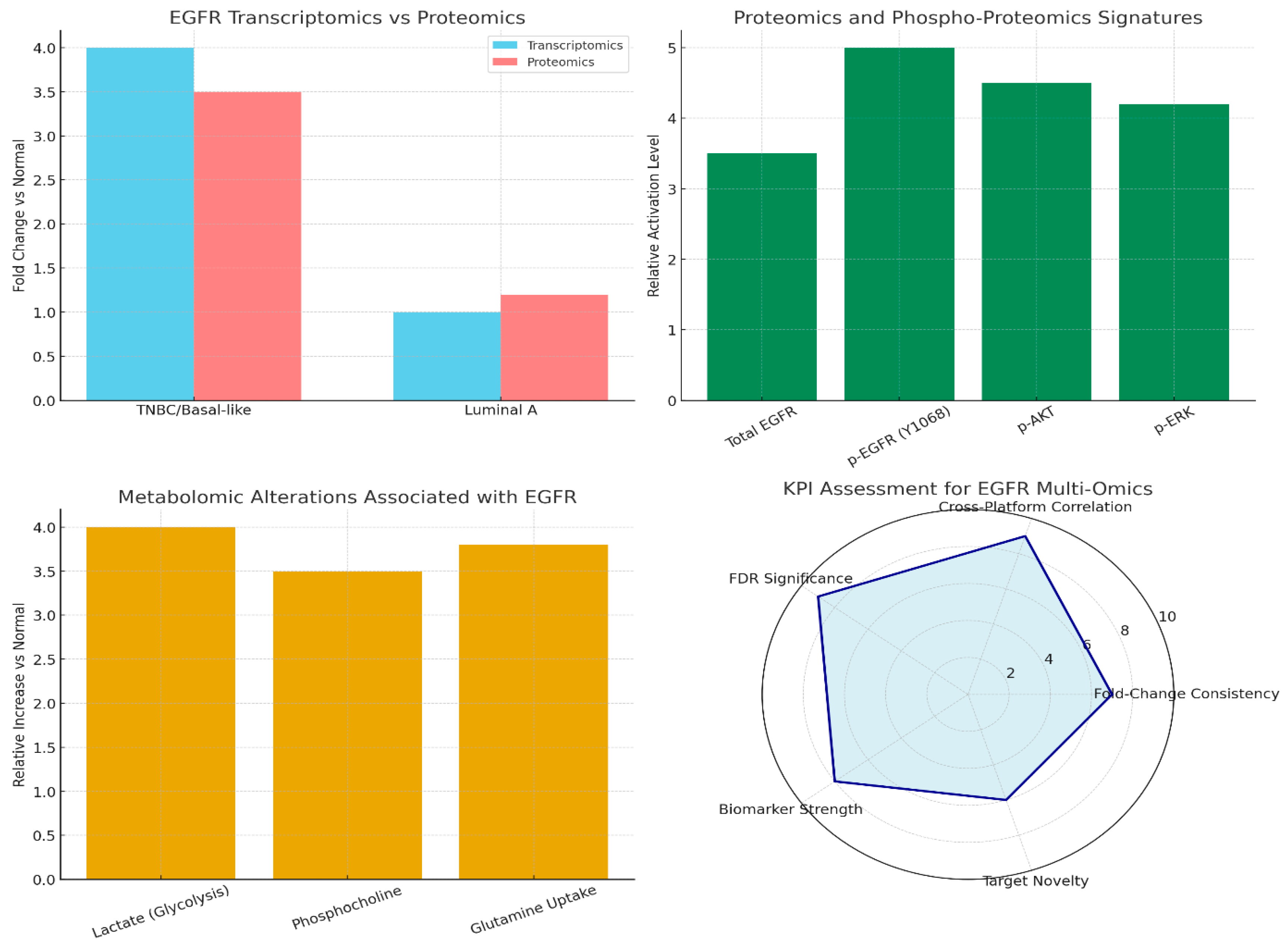

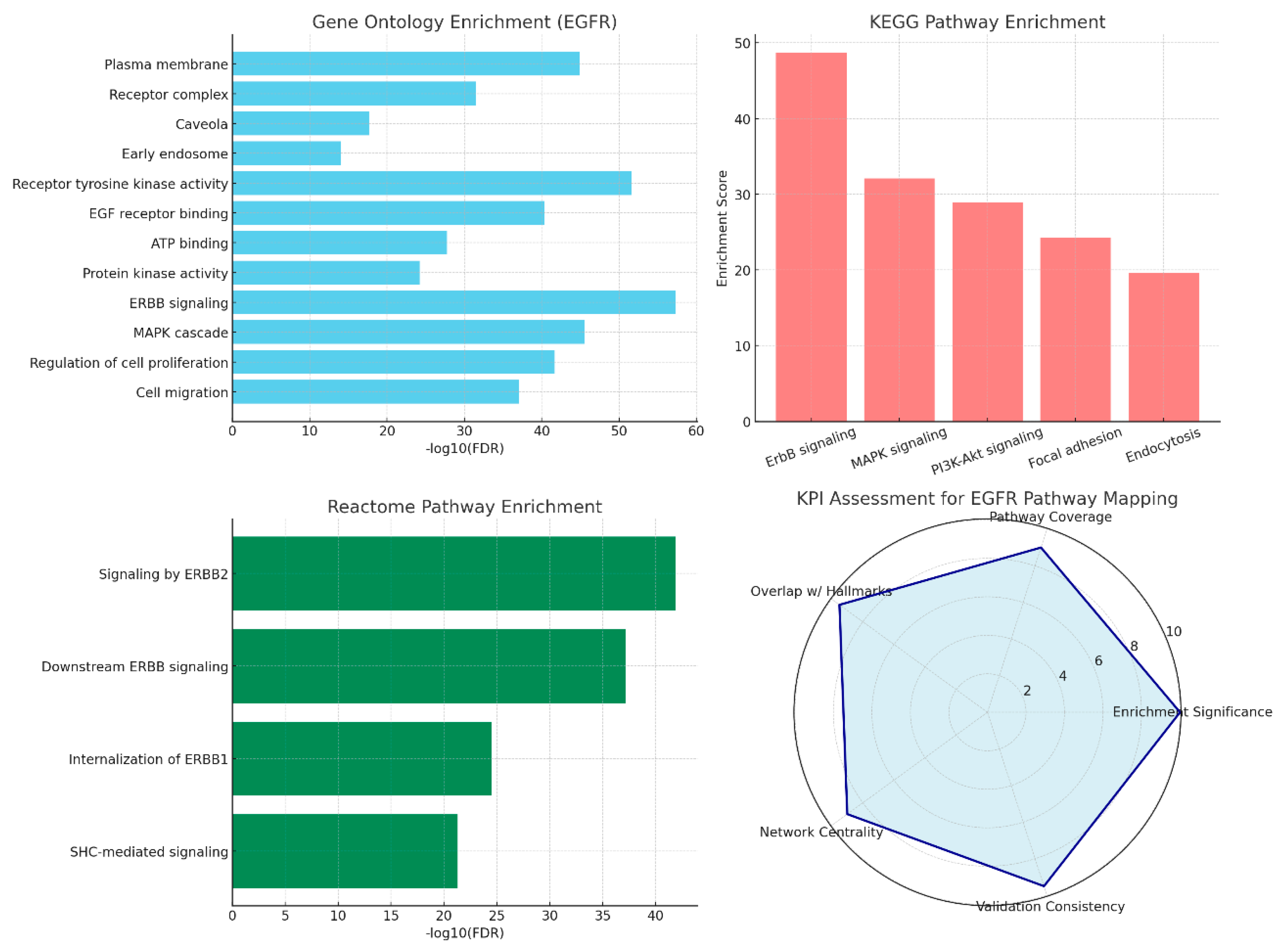

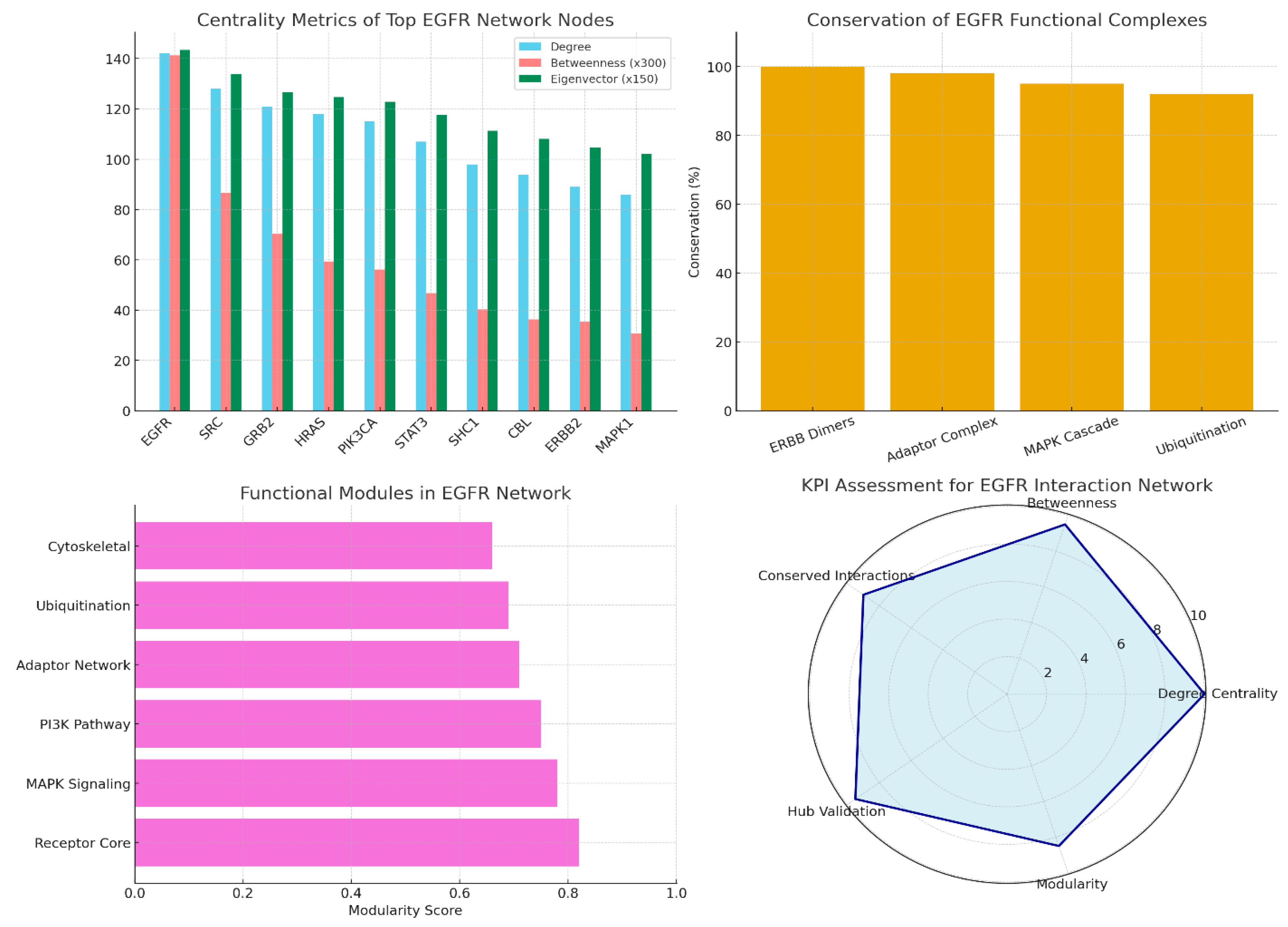

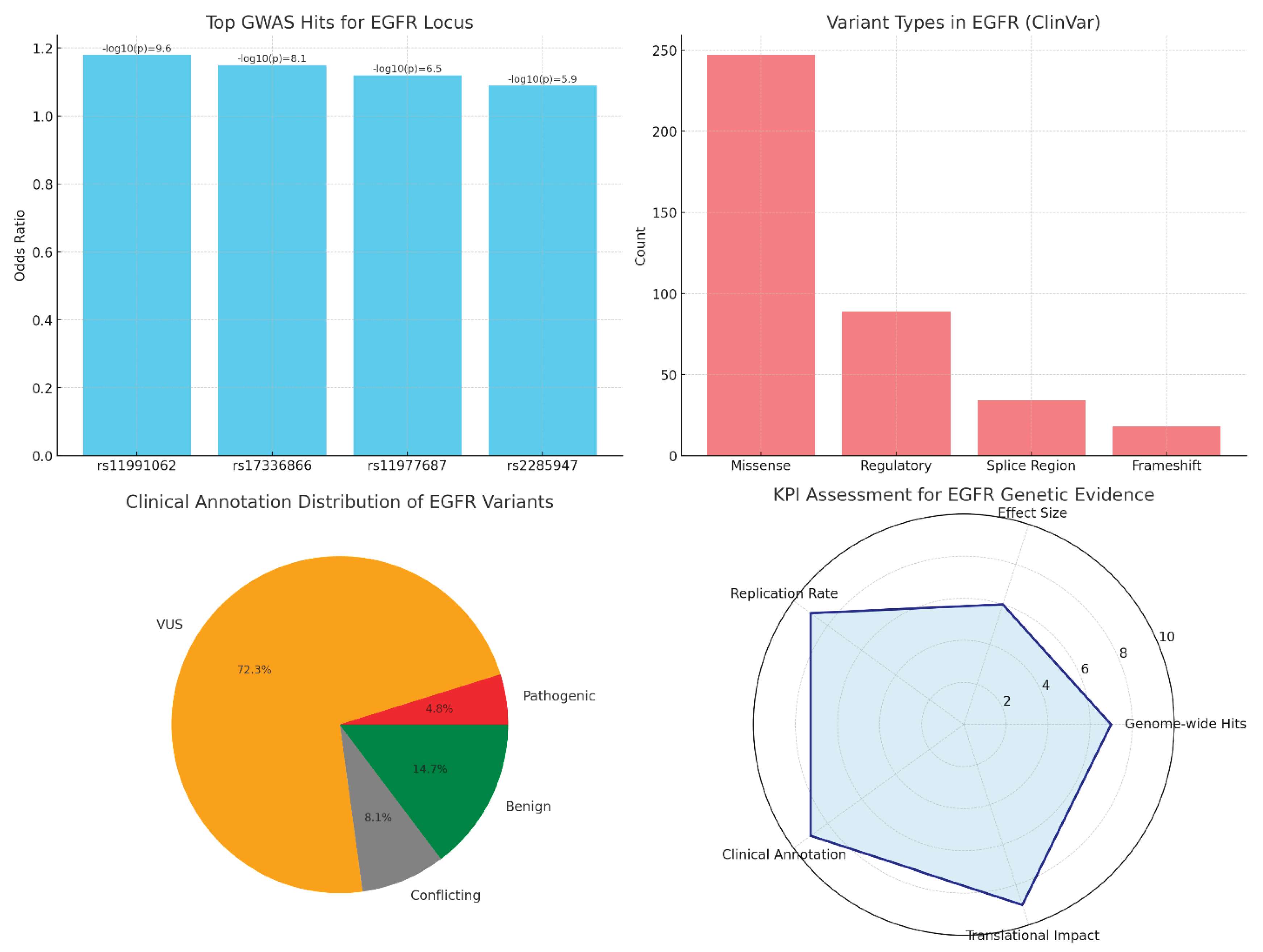

Result and Discussion

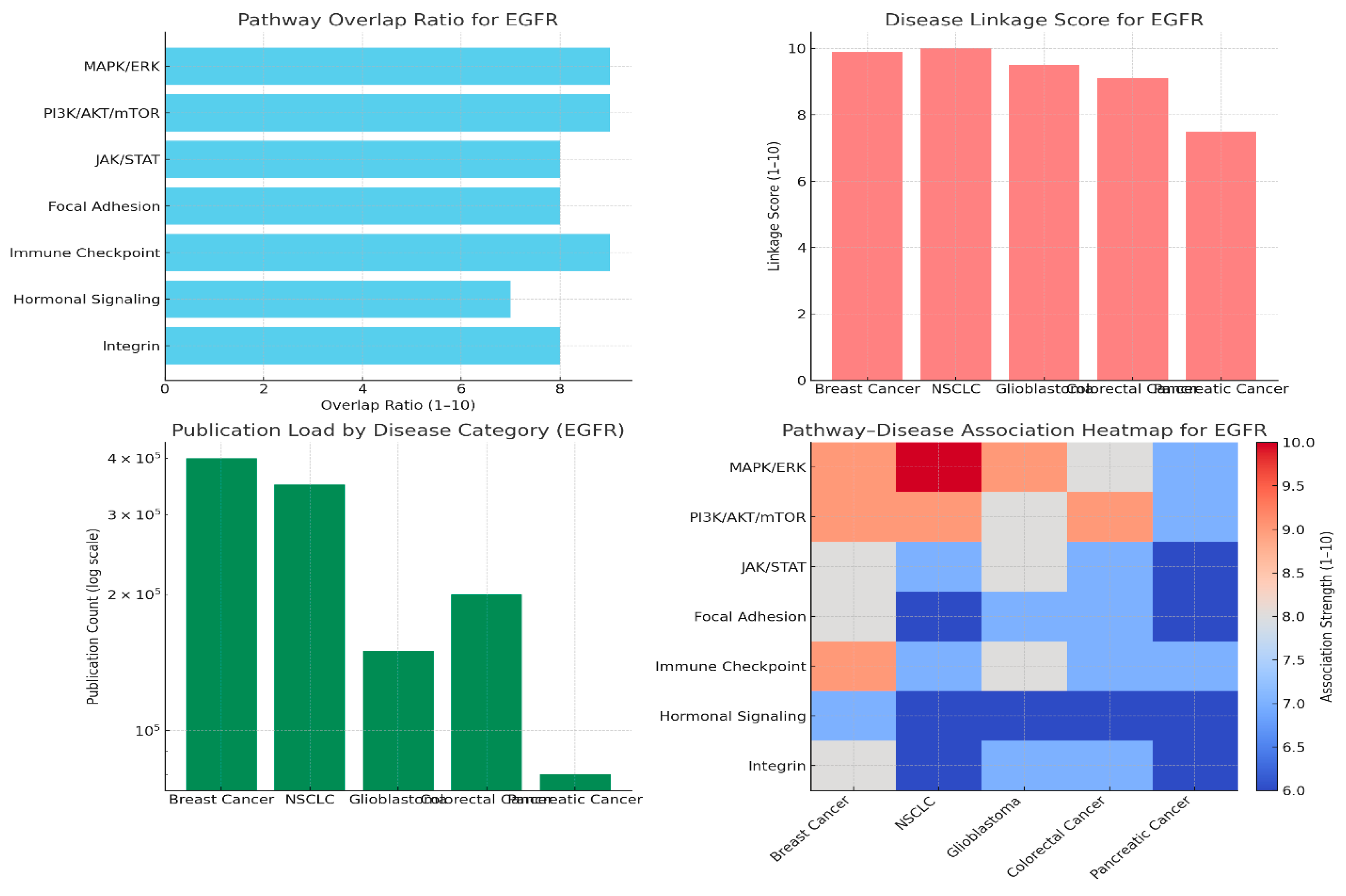

Pathway Overlap Ratio

Disease Linkage Scores

Publication Load by Disease Category

Pathway–Disease Heatmap

Conclusions

Conflict of Interest

References

- Masuda, H., Zhang, D., Bartholomeusz, C., Doihara, H., Hortobagyi, G. N., & Ueno, N. T. (2012). Role of epidermal growth factor receptor in breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment, 136(2), 331-345.

- Bai, X., Sun, P., Wang, X., Long, C., Liao, S., Dang, S., ... & Zhang, Z. (2023). Structure and dynamics of the EGFR/HER2 heterodimer. Cell Discovery, 9(1), 18. [CrossRef]

- Sigismund, S., Avanzato, D., & Lanzetti, L. (2018). Emerging functions of the EGFR in cancer. Molecular oncology, 12(1), 3-20. [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S. R., Kar, T., & Das, A. (2025). Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in breast Cancer: Therapeutic challenges and way forward. Bioorganic chemistry, 154, 108037. [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, M., Mahdiuni, H., Rasouli, H., Mansouri, K., Shahlaei, M., & Khodarahmi, R. (2018). Comparative experimental/theoretical studies on the EGFR dimerization under the effect of EGF/EGF analogues binding: Highlighting the importance of EGF/EGFR interactions at site III interface. International journal of biological macromolecules, 115, 401-417. [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, M., Nasser, M. W., Ravi, J., Wani, N. A., Ahirwar, D. K., Zhao, H., ... & Ganju, R. K. (2015). Modulation of the tumor microenvironment and inhibition of EGF/EGFR pathway: Novel anti-tumor mechanisms of Cannabidiol in breast cancer. Molecular oncology, 9(4), 906-919. [CrossRef]

- Paryani, J. (2018). Role of epidermal growth factor receptor in breast cancer: An analysis of biomolecular receptor study and its clinicopathological correlation. International Journal, 3(3), 70. [CrossRef]

- Changavi, A. A., Shashikala, A., & Ramji, A. S. (2015). Epidermal growth factor receptor expression in triple negative and nontriple negative breast carcinomas. Journal of laboratory physicians, 7(02), 079-083. [CrossRef]

- Lu X, Kang Y. Epidermal growth factor signalling and bone metastasis. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(3):457-461. [CrossRef]

- Carey, L. A., Rugo, H. S., Marcom, P. K., Irvin Jr, W., Ferraro, M., Burrows, E., ... & Winer, E. P. (2008). TBCRC 001: EGFR inhibition with cetuximab added to carboplatin in metastatic triple-negative (basal-like) breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 26(15_suppl), 1009-1009.

- Corkery, B., Crown, J., Clynes, M., & O’donovan, N. (2009). Epidermal growth factor receptor as a potential therapeutic target in triple-negative breast cancer. Annals of Oncology, 20(5), 862-867. [CrossRef]

- Baselga, J., Albanell, J., Ruiz, A., Lluch, A., Gascón, P., Guillém, V., ... & Rojo, F. (2005). Phase II and tumor pharmacodynamic study of gefitinib in patients with advanced breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23(23), 5323-5333. [CrossRef]

- Ciardiello, F., & Tortora, G. (2008). EGFR antagonists in cancer treatment. New England Journal of Medicine, 358(11), 1160-1174.

- Yarden, Y., & Pines, G. (2012). The ERBB network: at last, cancer therapy meets systems biology. Nature Reviews Cancer, 12(8), 553-563. [CrossRef]

- Thiery, J. P., Acloque, H., Huang, R. Y., & Nieto, M. A. (2009). Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. cell, 139(5), 871-890. [CrossRef]

- Swalife Biotech. (2024). Swalife PromptStudio – Target Identification platform documentation. Retrieved from.

- Yarden Y, Sliwkowski MX. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(2):127-137. [CrossRef]

- Sharma SV, Bell DW, Settleman J, Haber DA. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(3):169-181.

- Hynes NE, Lane HA. ERBB receptors and cancer: The complexity of targeted inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(5):341-354. [CrossRef]

- Zhang B, Wang J, Wang X, et al. Proteogenomic characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2014;513(7518):382-387. [CrossRef]

- Mertins P, Mani DR, Ruggles KV, et al. Proteogenomics connects somatic mutations to signalling in breast cancer. Nature. 2016;534(7605):55-62. [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z., & Guo, D. (2019). EGFR mutation: novel prognostic factor associated with immune infiltration in lower-grade glioma; an exploratory study. BMC cancer, 19(1), 1184. [CrossRef]

- Cao, H., Sun, B., Wang, J., Wu, S., Shi, N., Zhang, J., ... & Wang, H. (2025). Construction and validation of an EGFR-related risk signature identified SHC1 as a prognostic biomarker for lung adenocarcinoma. Translational Cancer Research, 14(7), 4331. [CrossRef]

- Haratani, K., Hayashi, H., Tanaka, T., Kaneda, H., Togashi, Y., Sakai, K., ... & Nakagawa, K. (2017). Tumour immune microenvironment and nivolumab efficacy in EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer based on T790M status after disease progression during EGFR-TKI treatment. Annals of oncology, 28(7), 1532-1539. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L. K., & Kholodenko, B. N. (2016, February). Feedback regulation in cell signalling: Lessons for cancer therapeutics. In Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology (Vol. 50, pp. 85-94). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Lu, D., Li, Q., Lu, F., Zhang, J., Wang, Z., ... & Wang, J. (2021). Identification of Six Prognostic Genes in EGFR–Mutant Lung Adenocarcinoma Using Structure Network Algorithms. Frontiers in Genetics, 12, 755245. [CrossRef]

- Waters, K. M., Liu, T., Quesenberry, R. D., Willse, A. R., & Bandyopadhyay, S. (2012). Network Analysis of Epidermal Growth Factor Signaling Using Integrated. [CrossRef]

- Sharip, A., Abdukhakimova, D., Wang, X., Kim, A., Kim, Y., Sharip, A., ... & Xie, Y. (2017). Analysis of origin and protein-protein interaction maps suggests distinct oncogenic role of nuclear EGFR during cancer evolution. Journal of Cancer, 8(5), 903. [CrossRef]

- Han, M. R., Zheng, W., Cai, Q., Gao, Y. T., Zheng, Y., Bolla, M. K., ... & Long, J. (2017). Evaluating genetic variants associated with breast cancer risk in high and moderate-penetrance genes in Asians. Carcinogenesis, 38(5), 511-518. [CrossRef]

- Baek, I. K., Cheong, H. S., Namgoong, S., Kim, J. H., Kang, S. G., Yoon, S. J., ... & Shin, H. D. (2022). Two independent variants of epidermal growth factor receptor associated with risk of glioma in a Korean population. Scientific reports, 12(1), 19014. [CrossRef]

- Fung, C., Zhou, P., Joyce, S., Trent, K., Yuan, J. M., Grandis, J. R., ... & Egloff, A. M. (2015). Identification of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) genetic variants that modify risk for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer letters, 357(2), 549-556. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).