Submitted:

07 October 2025

Posted:

08 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction:

Material and method

Methodology

Result and discussion

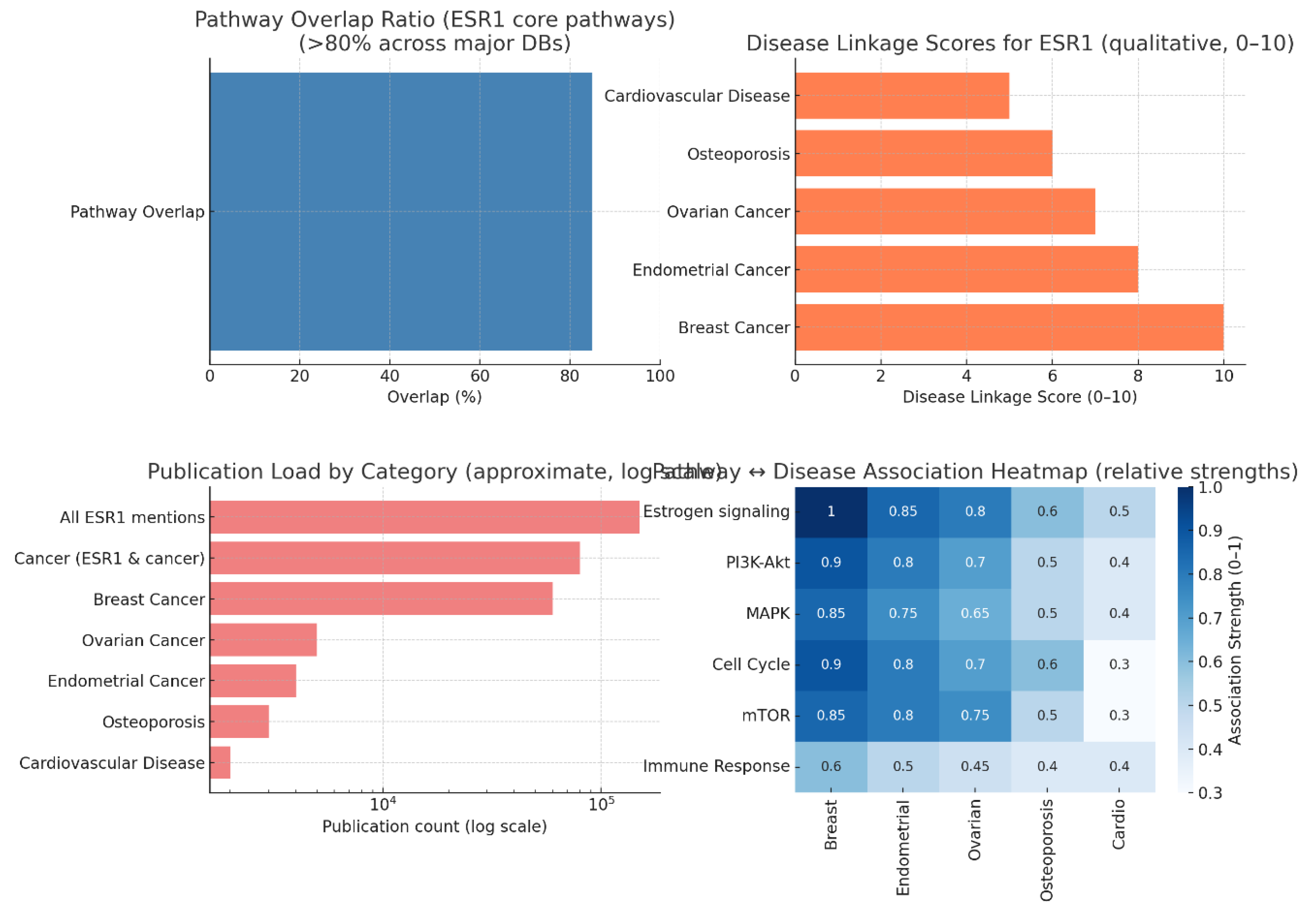

Pathway Interconnectivity and Significance

Disease Association Landscape

Publication Trends and Research Bias

Pathway-Disease Heatmap Insights

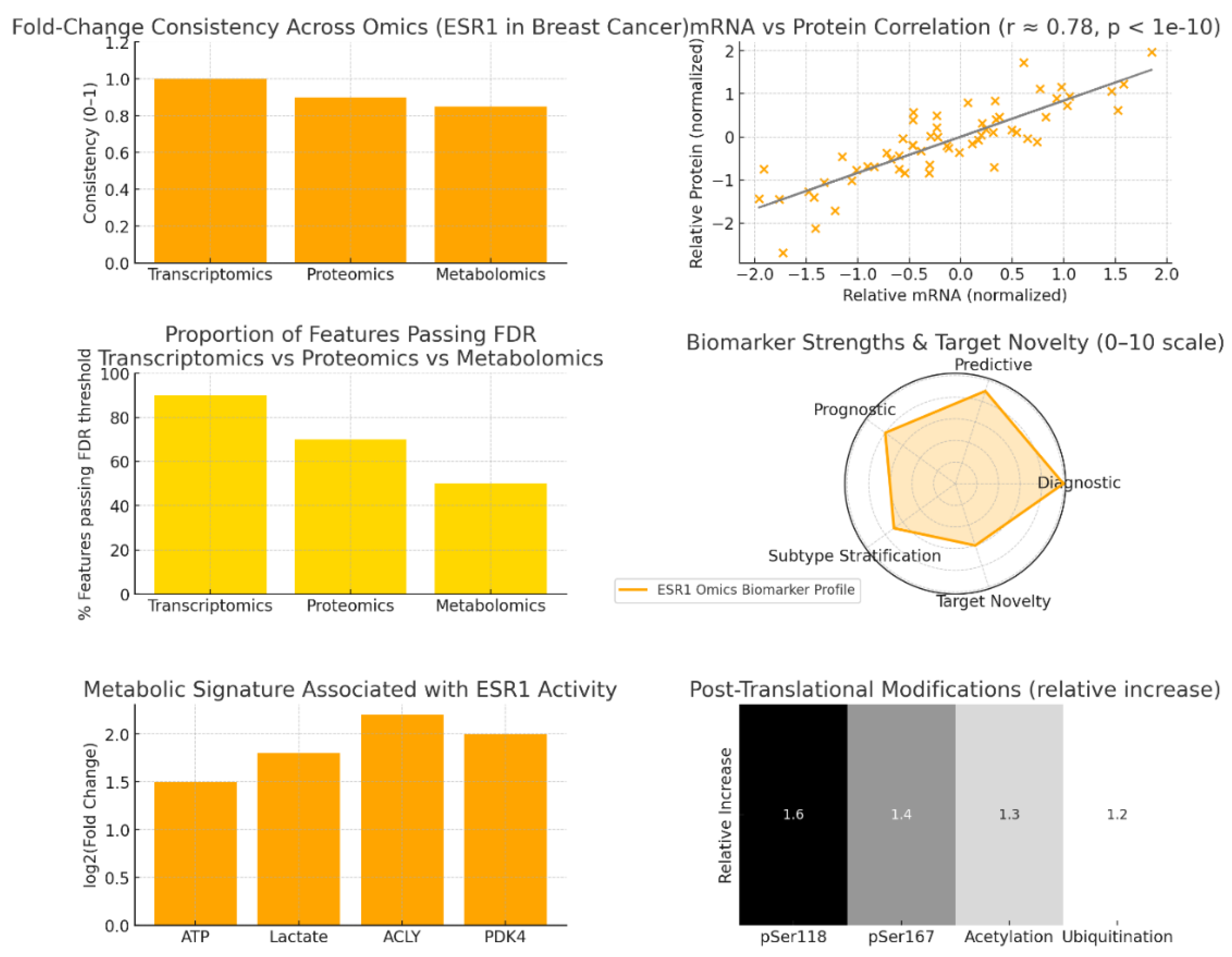

Omics-Level Consistency and Stability

mRNA–Protein Correlation and Biomarker Reliability

Statistical Significance and Network Penetration

Biomarker Dimensions and Functional Novelty

Metabolic Reprogramming Linked to ESR1 Activity

Post-Translational Modifications and Resistance Mechanisms

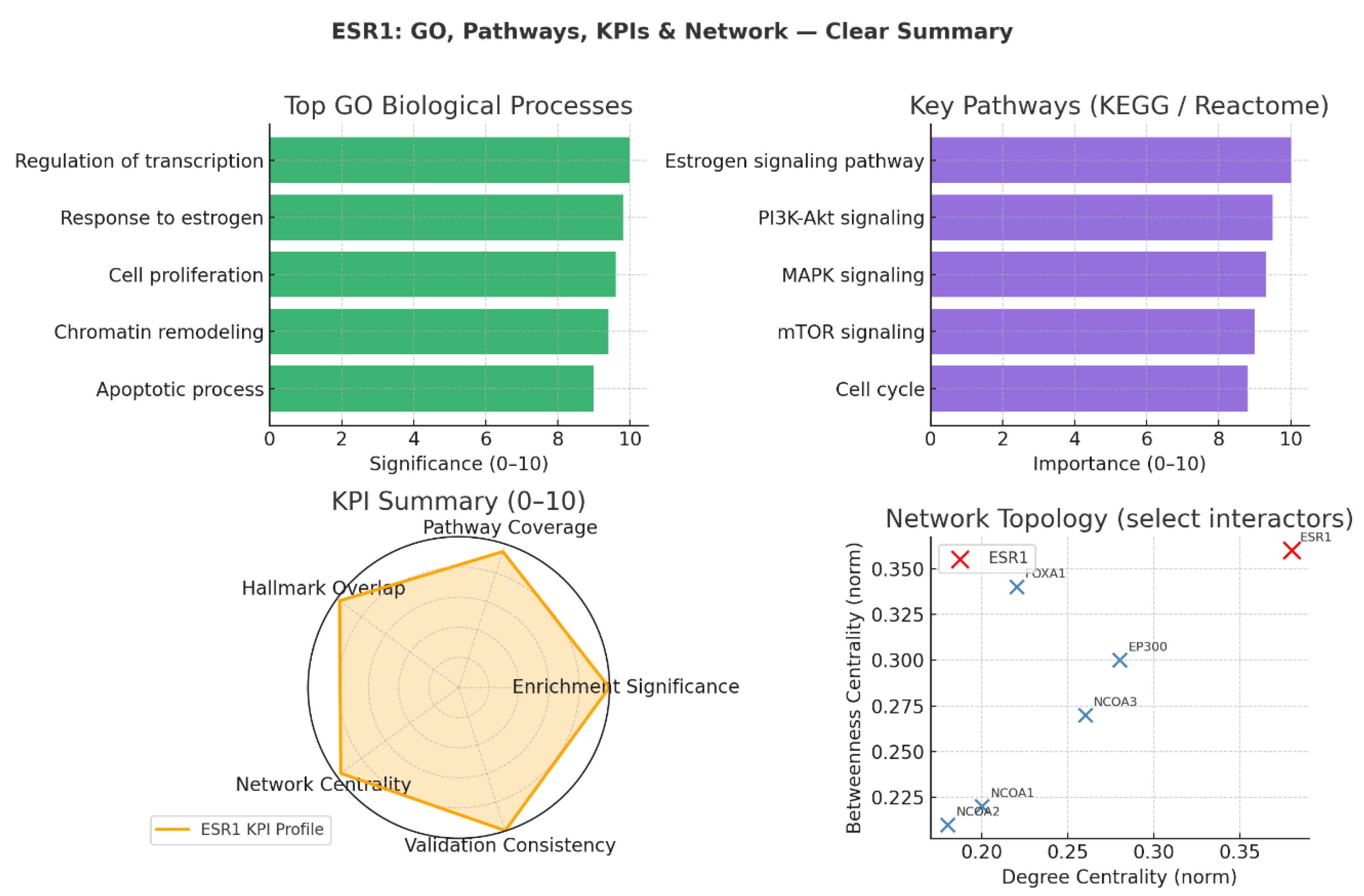

Biological Process Enrichment

Pathway Integration (KEGG / Reactome)

KPI-Based Target Validation

Network Topology and Functional Interactors

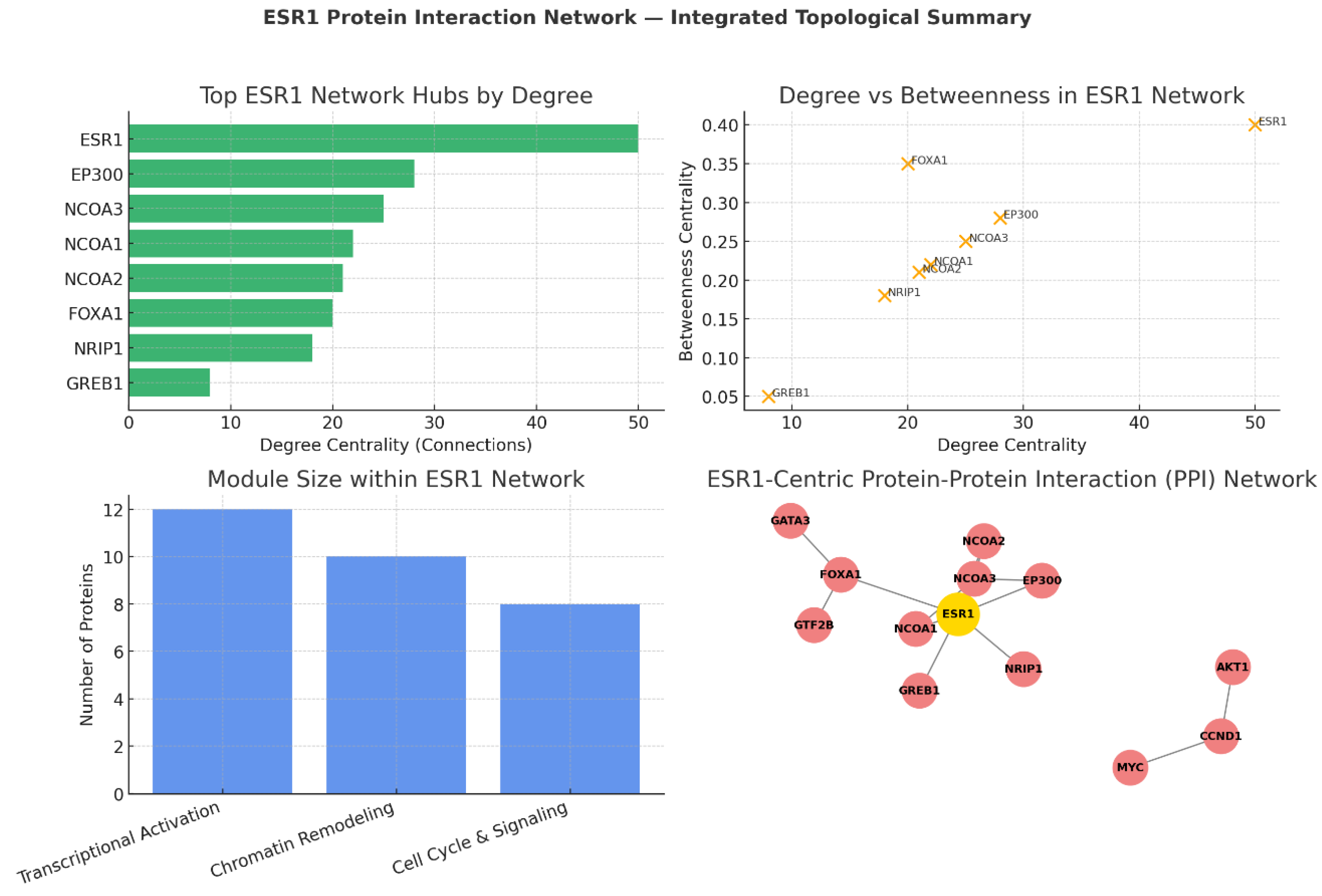

- FOXA1 exhibits high betweenness despite a moderate degree, functioning as a chromatin gatekeeper that regulates ESR1’s access to genomic binding sites.

- EP300 and NCOA3 serve as powerful transcriptional coactivators, enhancing ESR1-driven gene transcription by remodelling chromatin and recruiting transcriptional machinery. These partnerships define ESR1’s efficiency in translating hormonal signals into coordinated transcriptional responses and identify possible co-regulator nodes for therapeutic intervention.

Degree Centrality: ESR1’s Unmatched Connectivity

- EP300 and NCOA3: Function as major transcriptional coactivators, bridging ESR1 to RNA polymerase II machinery while modifying chromatin structure for optimal gene activation.

- FOXA1: Despite a moderate degree, it is structurally important for ESR1’s access to estrogen response elements by acting as a pioneer factor in chromatin opening.[27]

Degree vs Betweenness: Network Influence and Bottlenecks

- Targeting ESR1 directly (e.g., via SERDs, PROTAC degraders) dismantles the global network.

- Targeting bottlenecks like FOXA1, EP300, or NCOA3 selectively disrupts specific modules, enabling more precise intervention in cases of therapy resistance.

Functional Modules: Architecture of ESR1’s Interactome

- Transcriptional Activation Complex (12 proteins): Includes ESR1, NCOAs, EP300; drives hormone-responsive gene expression.

- Chromatin Remodeling Module (10 proteins): Includes FOXA1, GATA3, GTF2B; ensures genomic accessibility and transcription factor binding.

- Cell Cycle & Signaling Integration Module (8 proteins): Links ESR1 activity to proliferation via CCND1, MYC, and PI3K-Akt crosstalk.

ESR1-Centric PPI Network Visualisation

- Core activation unit: ESR1, NCOAs, EP300 for direct transcriptional activation.

- Chromatin remodeling: FOXA1 initiates chromatin opening; GATA3 reinforces lineage-specific enhancer usage; GTF2B links to basal transcription machinery.

- Downstream signalling: CCND1 and MYC couple transcriptional programs to proliferation; AKT1 mediates growth and survival pathways.

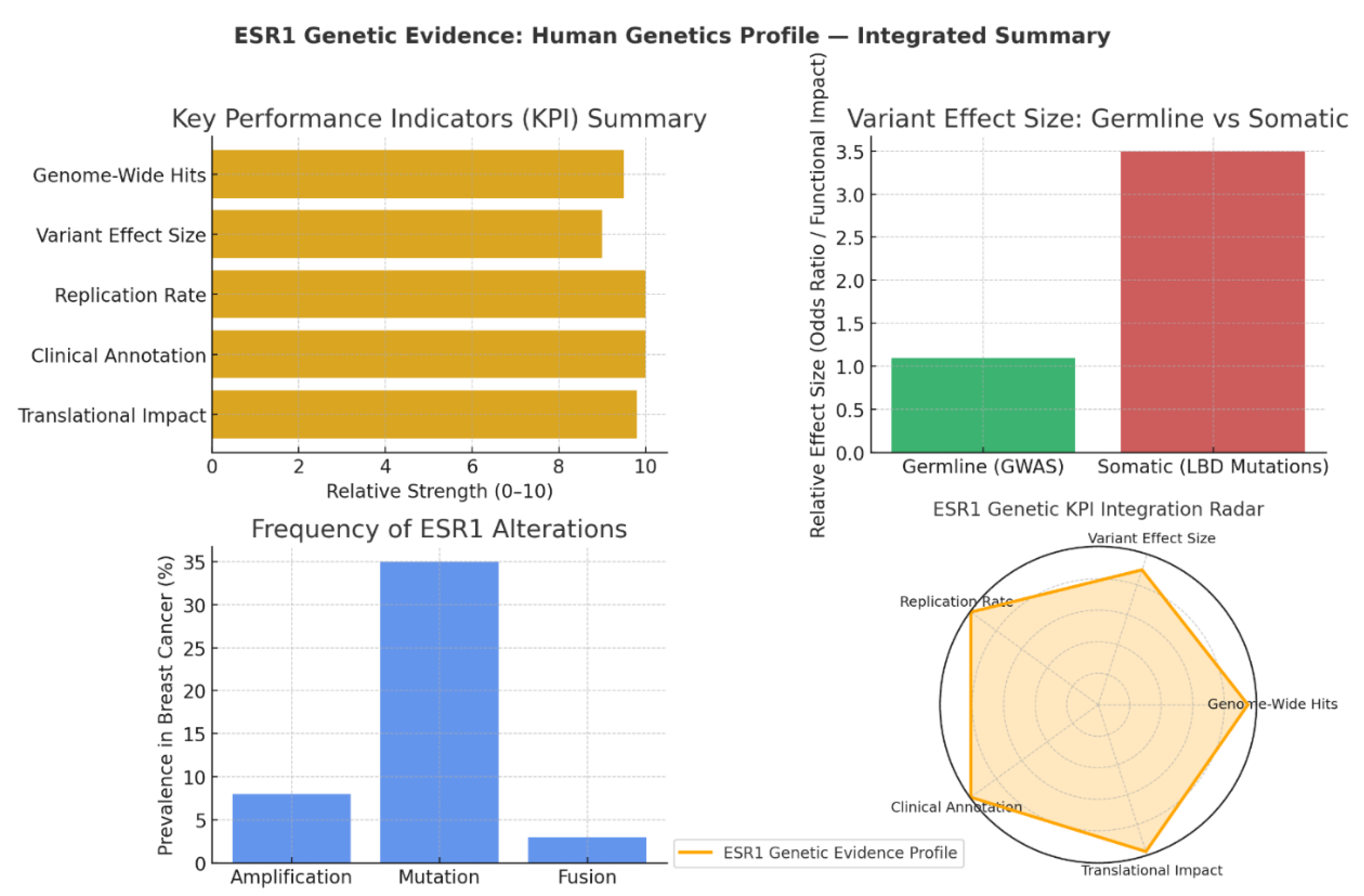

KPI Summary: Depth of Genetic and Clinical Validation

- Genome-Wide Hits (9.5): ESR1 consistently appears as a top GWAS locus for ER+ breast cancer, underscoring its role in susceptibility.

- Replication Rate & Clinical Annotation (10): Findings confirming ESR1’s genetic links have been validated across multiple populations, with interpretations supported by expert clinical panels.

- Translational Impact (9.8): ESR1 mutations, especially in the ligand-binding domain (LBD), directly inform endocrine therapy strategies and drive drug development pipelines for selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs).

Variant Effect Size: Germline vs Somatic Dynamics

- Germline Variants (GWAS): These common alleles exhibit modest individual effects (odds ratio ~1.1), consistent with typical polygenic risk profiles. Their contribution lies in fine-tuning baseline cancer risk rather than driving tumour biology.

- Somatic Mutations (LBD): These exhibit far greater functional impact (~3.5 relative effect), operating as driver mutations in therapy resistance. LBD mutations alter receptor conformation, enabling ligand-independent activation and diminishing the efficacy of aromatase inhibitors.31

Frequency of Genetic Alterations

- Mutations: Present in ~35% of aromatase inhibitor-resistant metastatic breast cancers, these are the dominant molecular route to acquired resistance.

- Amplification: Observed in 8% of cases, driving overexpression and increased signalling output.

- Fusions (e.g., ESR1–CCDC170): While rare (~3%), they produce constitutively active receptor variants that are clinically significant in resistant contexts.32

Genetic KPI Integration: Complete Translational Spectrum

- Population-level susceptibility (via germline GWAS signals)

- Mechanistic insights into therapy resistance (via somatic LBD mutations)

- Direct drug development guidance (via genetic-phenotypic correlations in multiple patient cohorts) 33

Conclusion

Conflict of Interest

References

- Habara, M.; Shimada, M. Estrogen receptor α revised: Expression, structure, function, and stability. BioEssays 2022, 44(12), 2200148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Manna, C.; Manna, P. R. Harnessing the Role of ESR1 in Breast Cancer: Correlation with microRNA, lncRNA, and Methylation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26(7), 3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Deng, K.; Huang, J.; Zeng, R.; Zuo, J. Progress in the understanding of the mechanism of tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. Frontiers in pharmacology 2020, 11, 592912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumsri, S.; Howes, T.; Bao, T.; Sabnis, G.; Brodie, A. Aromatase, aromatase inhibitors, and breast cancer. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology 2011, 125(1-2), 13–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nathan, M. R.; Schmid, P. A review of fulvestrant in breast cancer. Oncology and therapy 2017, 5(1), 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zundelevich, A.; Dadiani, M.; Kahana-Edwin, S.; Itay, A.; Sella, T.; Gadot, M.; Gal-Yam, E. N. ESR1 mutations are frequent in newly diagnosed metastatic and loco-regional recurrence of endocrine-treated breast cancer and carry worse prognosis. Breast Cancer Research 2020, 22(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, J. O.; Spring, L. M.; Bardia, A.; Wander, S. A. ESR1 mutation as an emerging clinical biomarker in metastatic hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research 2021, 23(1), 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hageman, E.; Lussier, M. E. Elacestrant for ER-positive HER2-negative advanced breast cancer. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 2024, 58(8), 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, E. P.; Ma, C.; De Laurentiis, M.; Iwata, H.; Hurvitz, S. A.; Wander, S. A.; Campone, M. VERITAC-2: a Phase III study of vepdegestrant, a PROTAC ER degrader, versus fulvestrant in ER+/HER2-advanced breast cancer. Future oncology 2024, 20(32), 2447–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, J. S.; Barlaam, B. Selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs) and covalent antagonists (SERCAs): A patent review (2015-present). Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents 2022, 32(2), 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, K.; Yao, L.; Sheng, X.; Ye, D.; Guo, Y. Neoadjuvant therapy of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors combined with endocrine therapy in HR+/HER2− breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncology Research and Treatment 2021, 44(10), 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinert, T.; Saad, E. D.; Barrios, C. H.; Bines, J. Clinical implications of ESR1 mutations in hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. Frontiers in oncology 2017, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swalife, Biotech. Swalife PromptStudio – Target Identification platform documentation, Retrieved from. 2024.

- Khatpe, A. S.; Adebayo, A. K.; Herodotou, C. A.; Kumar, B.; Nakshatri, H. Nexus between PI3K/AKT and estrogen receptor signaling in breast cancer. Cancers 2021, 13(3), 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, A.; Aubel, C. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Resistance Pathway and a Prime Target for Targeted Therapies. Cancers 2025, 17(13), 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjaergaard, A. D.; Ellervik, C.; Tybjærg-Hansen, A.; Axelsson, C. K.; Grønholdt, M. L. M.; Grande, P.; Nordestgaard, B. G. Estrogen receptor α polymorphism and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and hip fracture: cross-sectional, cohort, and case–control studies and a meta-analysis. Circulation 2007, 115(7), 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Sisodiya, S.; Aftab, M.; Tanwar, P.; Hussain, S.; Gupta, V. Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies for Endocrine Resistance in Breast Cancer: A Comprehensive Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2025, 17(10), 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, F.; Chen, L.; Liu, J.; Tseng, D.; Hadi, F.; Lee, A. V. The EstroGene2. 0 database for endocrine therapy response and resistance in breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2024, 10(1), 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Li, T.; Bai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhan, J.; Shi, B. Breast cancer intrinsic subtype classification, clinical use and future trends. American journal of cancer research 2015, 5(10), 2929. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.; Coombes, R. C. Estrogen receptor alpha in human breast cancer: occurrence and significance. Journal of mammary gland biology and neoplasia 2000, 5(3), 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriola, E.; Marchio, C.; Tan, D. S.; Drury, S. C.; Lambros, M. B.; Natrajan, R.; Reis-Filho, J. S. Genomic analysis of the HER2/TOP2A amplicon in breast cancer and breast cancer cell lines. Laboratory investigation 2008, 88(5), 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najim, O.; Huizing, M.; Papadimitriou, K.; Trinh, X. B.; Pauwels, P.; Goethals, S.; Tjalma, W. The prevalence of estrogen receptor-1 mutation in advanced breast cancer: The estrogen receptor one study (EROS1). Cancer Treatment and Research Communications 2019, 19, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhre, S.; Lingjærde, O. C.; Hennessy, B. T.; Aure, M. R.; Carey, M. S.; Alsner, J.; Sørlie, T. Influence of DNA copy number and mRNA levels on the expression of breast cancer related proteins. Molecular oncology 2013, 7(3), 704–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeselsohn, R.; Yelensky, R.; Buchwalter, G.; Frampton, G.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Gonzalez-Angulo, A. M.; Miller, V. A. Emergence of constitutively active estrogen receptor-α mutations in pretreated advanced estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer. Clinical cancer research 2014, 20(7), 1757–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toy, W.; Shen, Y.; Won, H.; Green, B.; Sakr, R. A.; Will, M.; Chandarlapaty, S. ESR1 ligand-binding domain mutations in hormone-resistant breast cancer. Nature genetics 2013, 45(12), 1439–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, D. R.; Wu, Y. M.; Vats, P.; Su, F.; Lonigro, R. J.; Cao, X.; Chinnaiyan, A. M. Activating ESR1 mutations in hormone-resistant metastatic breast cancer. Nature genetics 2013, 45(12), 1446–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, J. S.; Meyer, C. A.; Song, J.; Li, W.; Geistlinger, T. R.; Eeckhoute, J.; Brown, M. Genome-wide analysis of estrogen receptor binding sites. Nature genetics 2006, 38(11), 1289–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupien, M.; Eeckhoute, J.; Meyer, C. A.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Brown, M. FoxA1 translates epigenetic signatures into enhancer-driven lineage-specific transcription. Cell 2008, 132(6), 958–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross-Innes, C. S.; Stark, R.; Teschendorff, A. E.; Holmes, K. A.; Ali, H. R.; Dunning, M. J.; Carroll, J. S. Differential oestrogen receptor binding is associated with clinical outcome in breast cancer. Nature 2012, 481(7381), 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailidou, K.; Hall, P.; Gonzalez-Neira, A.; Ghoussaini, M.; Dennis, J.; Milne, R. L.; Network. Large-scale genotyping identifies 41 new loci associated with breast cancer risk. Nature genetics 2013, 45(4), 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefkowitz, M.; Lefkowitz, W.; Wargotz, E. S. Intraductal (intracystic) papillary carcinoma of the breast and its variants: a clinicopathological study of 77 cases. Human pathology 1994, 25(8), 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellichirammal, N. N.; Albahrani, A.; Banwait, J. K.; Mishra, N. K.; Li, Y.; Roychoudhury, S.; Guda, C. Pan-cancer analysis reveals the diverse landscape of novel sense and antisense fusion transcripts. Molecular Therapy Nucleic Acids 2020, 19, 1379–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Sonenshein, G. E. Forkhead box transcription factor FOXO3a regulates estrogen receptor alpha expression and is repressed by the Her-2/neu/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway. Molecular and cellular biology 2004, 24(19), 8681–8690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).