1. Introduction

Cities are dynamic and ever-evolving systems, influenced by a range of social, economic, and environmental factors. Effective planning plays a crucial role in guiding their development, as unregulated growth often leads to urban sprawl, inefficient land utilization, poor accessibility, and inadequate public services [

1]. As urbanization continues to accelerate and an estimated 70% of the world’s population is expected to live in cities by 2050, it becomes essential to invest in vital infrastructure, affortable housing, efficient transportation networks, and key social services to ensure cities are inclusive, resilient, and sustainable for all residents [

2]. Therefore, sound urban planning is fundamental to achieving sustainability, and without it, cities are unlikely to realize a positive and resilient future. Towards this direction, in 2015 the United Nation Member States have adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development which includes 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which are an urgent call for action by all countries - developed and developing - in a global partnership [

3].

The increase of land value, housing construction cost, economic growth and several planning policies are considered as influential factors for urban sprawl which leads residents to move away from the city center [

4,

5]. The impact of urban sprawl is multidimensional increasing transportation’s economic, social and environmental costs. Cities that continue to follow a sprawl pattern, their spatial distribution will prevent them from achieving sustainable and efficient urban transportation, no matter what [

6]. While the phenomenon of urban sprawl is increasing by the years it also affects positively the car dependency and thus the vehicles miles traveled per capita and the congestion-related delays [

7], which in turn decreases the number of commuters who walk or use public transport [

8,

9].

Acknowledging the requirements of the sustainable cities and communities (11

th goal of the 17 SDGs) but also the new rhythms of living, working and taking leisure requires a transformation of the urban space that is still strongly monofunctional, with the central city and its various specializations towards a polycentric city, driven by 4 major components: proximity, diversity, density, ubiquity. In this context the idea of the 15-minute city was born, where in 15-minutes an inhabitant can access his or her essential daily needs either by walk or bike [

10]. Therefore, the 15-minute city concept it is important to be seen as an urban development theme and not in isolation from urban planning and design practice [

11]. Reducing daily journeys to 15-minutes on foot or by bicycle helps reduce congestion in the city, reduce air pollution, improve quality of life, promote a health lifestyle and can help create more integrated communities [

12].

Several studies have used and analyzed the 15-minute concept (e.g., [

13,

14,

15]). However, analyses related to the 15-minute city concept must account for potential limitations, such as overlooking individual differences in walking and cycling abilities. To address this, it is important to consider slower walking speeds and include populations who are unable to walk or cycle in the planning process [

16]. Furthermore, cities with cultural preferences for driving may limit the effective use of local amenities, even when alternative exist [

17].

This study implements a spatial analysis utilizing the 15-minute concept in the city of Limassol (Cyprus), a city with an inefficient public transport service and almost inexistent cycling infrastructure [

18]. In detail, this paper presents how planning policies may be inadequate over time for avoiding phenomena of urban sprawl and thus creating transportation issues (such as congestion). Towards this purpose walking and cycling isochrones were implemented investigating the ability of residents to enjoy a higher quality of life by fulfilling six essential urban social functions, such as, lining; working; commerce; healthcare; education and entertainment [

19]. Similar application has been made by [

20], where they used isochrones for capturing realistic travel behavior and spatial dynamics instead of conventional buffer-based approaches.

Social functions where interpreted by the use of geo-located Points-of-Interest (POIs) which are considered adequate information for this application [

21]. The level of readiness to adopt the 15-minute concept was estimated by the percentage of residential coverage from the 15-minute walking and cycling isochrones initiating from the social functions’ locations [

22]. The results indicate the lack of readiness to adopt the 15-minute concept in the city of Limassol, due to the planning policies followed for the last 20 years which leaded to urban sprawl structures due to the unplanned and vast urban development that this city has followed over the years.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 presents the case study of this research and the data collected for its purposes.

Section 3 presents the results of this study. Discussion and conclusions are provided in the last section.

2. Case Study: Limassol, Cyprus

In this study we implement a spatial analysis using geo-referenced POIs that describe different social function locations (e.g., educational buildings) along with the road network and the land uses of the region (Limassol, Cyprus). Specifically, 15-minute walking and cycling isochrones where developed and the coverage percentage of the residential areas was measured. Prior any implementation it is important to conceptualize the city model, how this has occurred and created an urban sprawl structure and how this can be resolved through the implementation of the 15-minute concept.

2.1. Unregulated Economic Growth

This section presents an overview of the historic development of Limassol (Cyprus) over the years along with the planning policies followed that both led to the urban sprawl that this city is characterized which led to further problems, such as, low population densities and congestion not only in peak hours.

Cyprus has launched a naturalization scheme which allowed foreigners to invest in real estate in Cyprus (up a minimum of two million euros each). This investment scheme lasted until 2020 where the government decided to suspend it after EU recommendations [

23]. However, even after 2020 the development continued, based on the attraction of digital nomads, new investors and highly paid employees as a result of new governmental inventive plans, but also due to the unstable conditions in Middle Eastern and European countries, showing its continuous resilience and importance to the overall economy of the country.

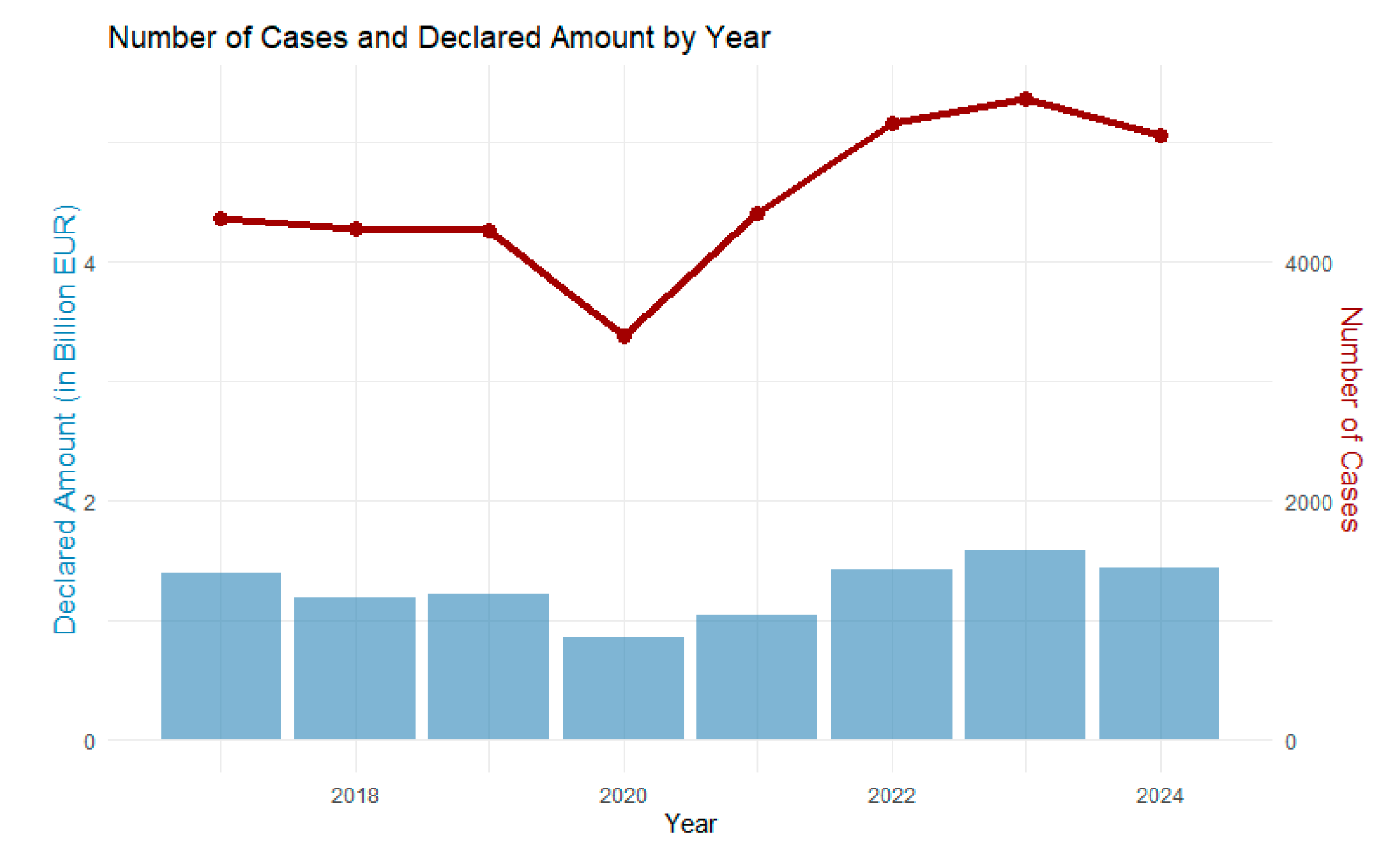

Figure 1 presents the number of cases of real estate sales were opened in Limassol and the total amounts declared in the Land Registry, presenting the decrement in 2020 and the escalation of this sector after 2020.

Since Limassol is a coastal city, the prices of plots close to the seafront have become unattainable, leading young people to seek alternative investment options for the redevelopment of their housing, resulting in a shift toward the city’s outskirts where property prices are more affordable, fact that forced Limassol to an urban sprawl structure.

2.2. Planning Policies

Planning policies are significant for the development of the city and for the regulation and thus prevention of phenomena, such as urban sprawl. Although urban development provides an economic growth to the region, it also affects the planning policies and, in some cases, it raises considerations of maintaining the agricultural land use and the demand for more living space, which in turn leads to urban sprawl. Examples, show also that due to urban sprawl the agricultural production is reduced, ecosystem and lifestyle is disturbed and land values increase [

24]. In the case of Limassol, planning policies appeared over the years to lead to directions that point out to urban sprawl.

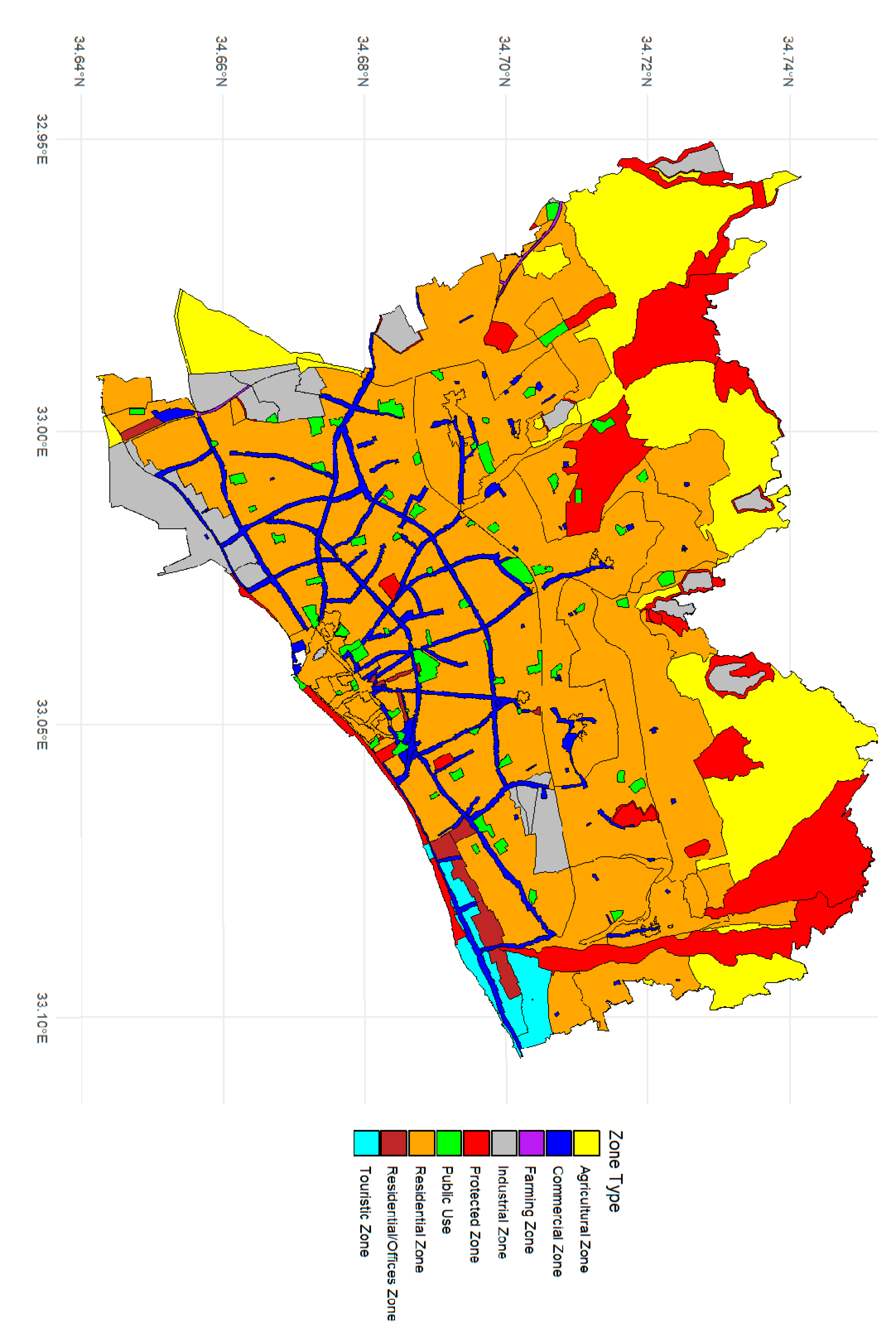

Figure 2 presents the general planning zones in Limassol for the year 2020.

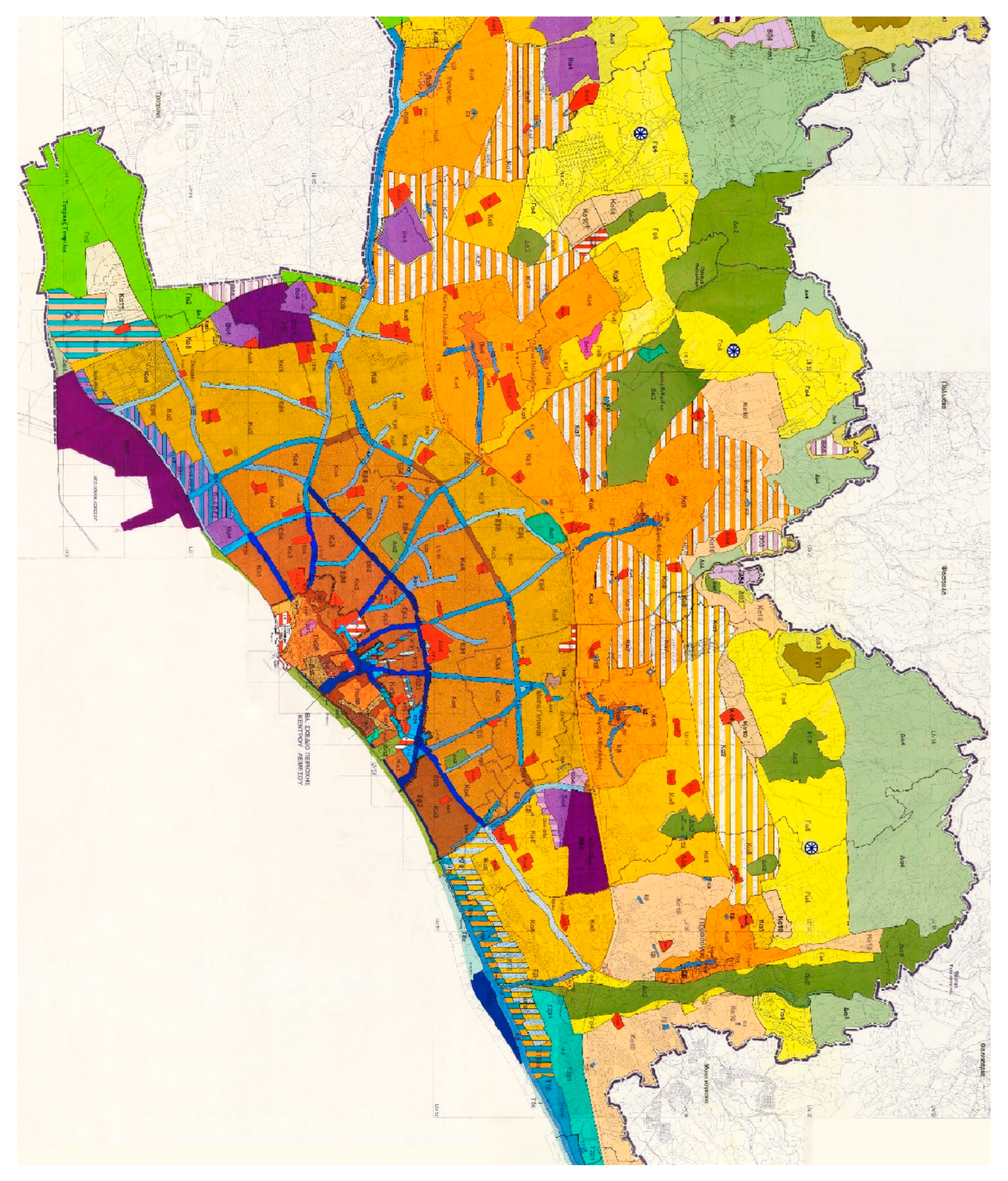

Analyzing how the planning policies have been evolved in the city of Limassol it is important to observe the planning zones within a framework of ten to twenty years. Therefore,

Figure 3 presents the planning zones in 2006 with yellow color the agricultural zones, which start with the Greek letter “Γ”. Comparing the two figures (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) it can be observed that many agricultural areas in the planning zones of 2006 have been resolved as residential areas in the planning zones of 2020 (approximately more than 1.5 square kilometers) indicating the planning policies followed which show the trend of urban expansion thus the urban sprawl the city of Limassol has followed the last twenty years. It should be noted that urban densities at the 2006 planning zones were very low compared to the average European city, and in most of the residential areas below 50 residents per hectare [

36].

Urban sprawl can be controlled or limited, likewise in the case of Limassol, by planning policies (e.g., restriction of specific land use), economic interventions (e.g., trading in building permits, and institutional change and management (e.g., special agencies for urban revitalization) [

27].

2.3. Infrastructure

Planning policies and road infrastructure are closely interrelated. In many cases, areas undergoing urban development, often driven by economic growth, are not effectively regulated by planning policies to prevent urban sprawl. Instead, these policies may unintentionally encourage it. As a result, new residential roads are constructed to accommodate the expanding development. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle: the construction of roads influences land use patterns and stimulates further development, which in turn increases the demand for more roads in previously undeveloped areas. Ultimately, this dynamic reinforces urban sprawl and contributes to the continuous outward expansion of cities, like the case of Limassol.

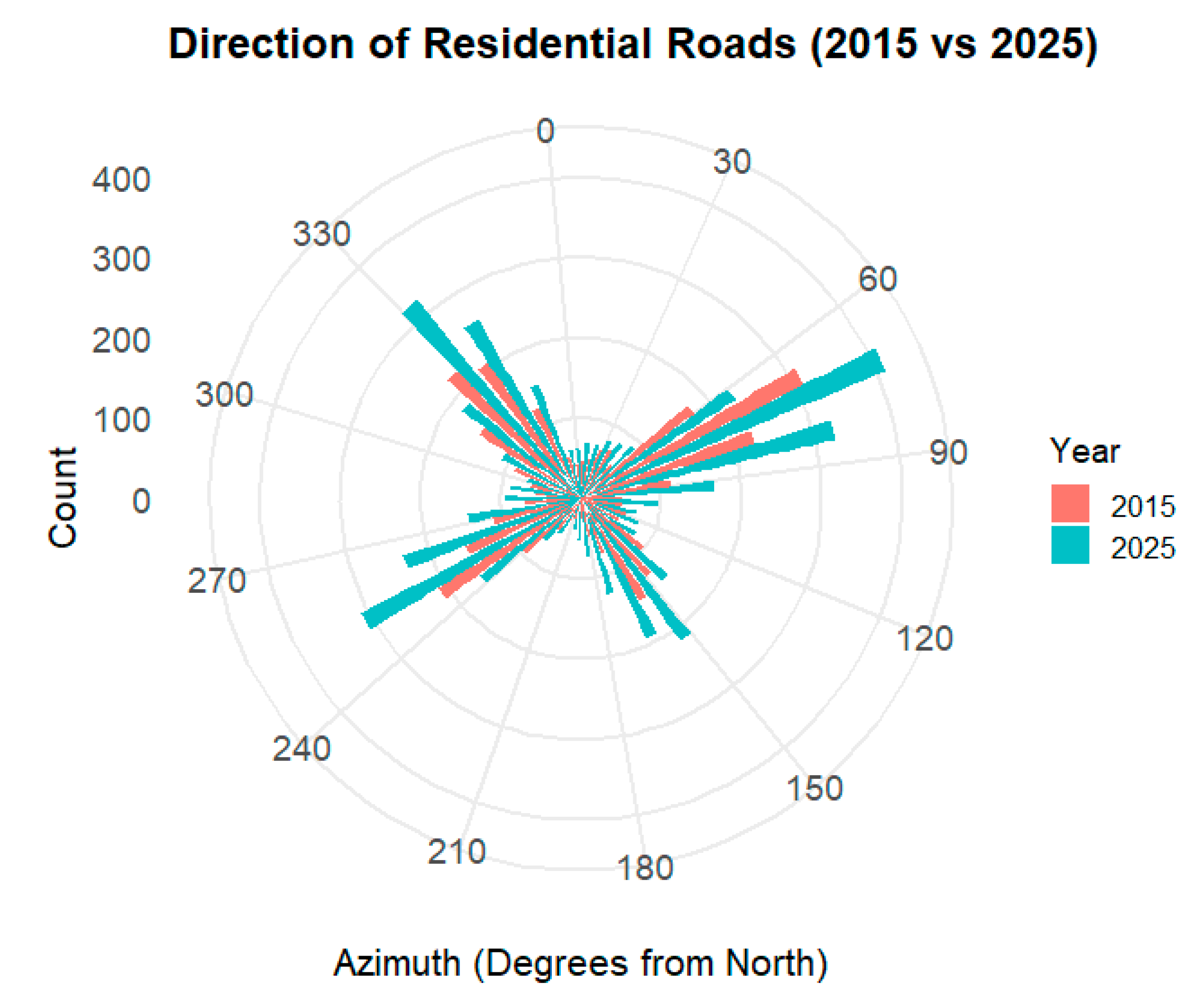

Figure 4 presents the direction of the residential roads from 2015 and 2025 indicating that since after a decade the city still proceeds with the construction of residential roads some of the in the sea front and most of them across the coastline and in the hinterland of the city and few of them in the city center. Therefore, this figure presents the direction of the city’s development which again follows the urban sprawl model.

However, despite the expansion of the residential road network in Limassol, it appears that the city also lacks efficiency in micromobility infrastructure, specifically, in the provision of dedicated cycleways.

Figure 5 presents the existing cycleway network in Limassol, highlighting its limited spatial coverage and fragmented layout. Most cycleways are concentrated along the coastal front and a few central corridors, while large areas, especially in the western, northern, and inner parts of the city, remain disconnected or underserved. This fragmented infrastructure poses challenges for safe and continuous cycling routes, potentially discouraging daily bicycle use for commuting and reducing the attractiveness of sustainable mobility options overall.

2.4. Social Functions

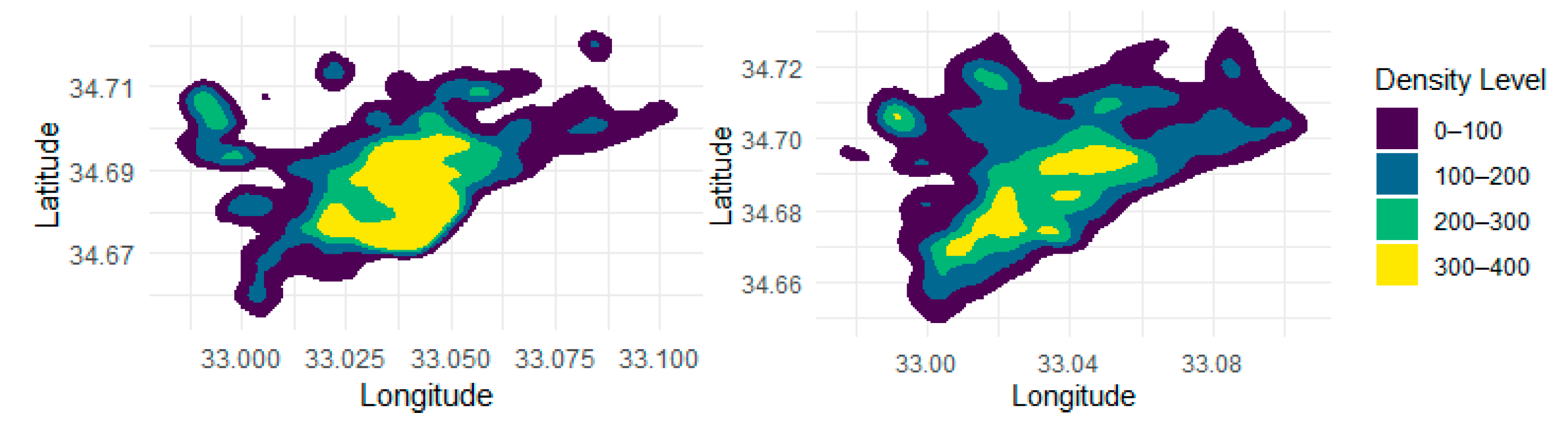

To support the spatial analysis of how Limassol can transition into a 15-minute city, despite its current sprawling structure resulting from insufficient planning policies, geolocated social function locations were collected using Points of Interest (POIs) from OpenStreetMap. The POIs were extracted for two reference years, 2015 and 2025, and are presented in

Figure 6. In 2015, the majority of POIs were concentrated in the city center, forming a predominantly monocentric structure. However, by 2025, the distribution of POIs appears more dispersed, indicating the emergence of polycentric urban patterns. Moreover, several POIs in 2025 are located in areas that were previously unserved in 2015. Given that the current urban form is the focus of this analysis and that the goal is to assess the city’s potential evolution toward the 15-minute city concept, the 2025 POIs were selected as the primary dataset for further investigation.

For analyzing the 15-minute concept for the city of Limassol the POIs were grouped into different urban social functions, such as:

Education (e.g., schools)

Food (e.g., restaurants, supermarkets)

Green Areas (e.g., parks)

Health (e.g., hospitals)

Services (e.g., banks, public authorities)

Shopping (e.g., shops.

Tourism (e.g., hotels, museums)

Transport (e.g., bike rentals)

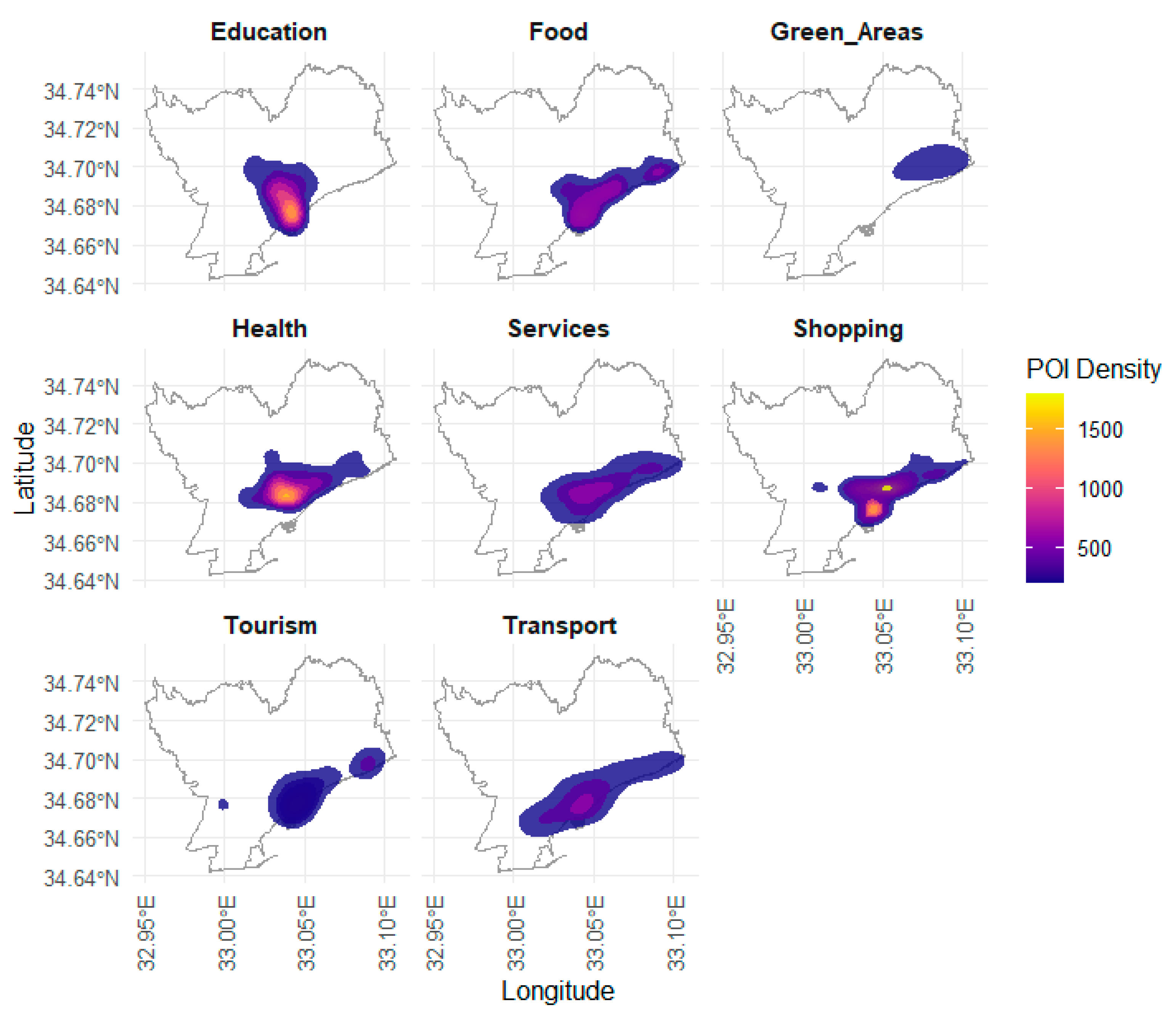

Figure 7 illustrates the spatial density distribution of POIs by different functional groups in Limassol for the year 2025. Notably, the POI distribution across categories such as Education, Health, Services, and Shopping remains heavily concentrated in the central and eastern parts of the city. In particular, the Shopping and Health categories exhibit intense clustering, indicating areas with high accessibility to these services, possibly representing key urban cores or commercial zones. This suggests that although some decentralization is observed, the urban structure still exhibits characteristics of centralization in certain service domains.

On the other hand, categories like Green Areas, Tourism, and Transport show a more dispersed spatial pattern, with POIs extending toward the city’s periphery. This dispersion may reflect ongoing efforts to improve access to public amenities and transport infrastructure in less dense or previously underserved areas, supporting a shift toward a more polycentric and equitable urban form. The variation in density among categories highlights the uneven development of functional accessibility, which poses both challenges and opportunities for implementing the 15-minute city concept in Limassol. Strengthening the spatial distribution of essential services in currently underrepresented areas could help support more balanced, inclusive, and sustainable urban mobility and accessibility.

This analysis is also motivated by the growing recognition that maintaining strong local social connections and access to everyday amenities is essential for enhancing urban liveability. As observed in many cities, including Limassol, essential services and facilities tend to be concentrated in central urban areas, while peripheral neighborhoods, often predominantly residential, remain underserved. This uneven spatial distribution limits walkability and challenges the implementation of inclusive, human-centered planning frameworks such as the 15-minute city [

19].

3. Results and Discussion

Based on the overview provided for the city of Limassol a concerned was raised for the city following urban sprawl structure due to the inefficiency of the planning policies followed for the last 10-20 years. Furthermore, the large number of cars, the limited parking spaces, the narrow sidewalks, the traffic accidents involving pedestrians and cyclists the few green spaces and the bike-unfriendly mentality that exists make difficult the transition from the current state of Limassol to a different concept of the city [

29].

Since the city of Limassol has been evolved to an urban sprawl structure it is important to study how the city can adopt the 15-minute concept where inhabitants (i.e., residential areas) will be able to be delivered by the different amenities within a walking or cycling distance of 15 minutes. Towards this purpose 15-minute walking and cycling isochrones where generated with the center of each social functions for the different groups. The percentage of coverage of the residential zone is then measured for observing how the city of Limassol is ready to adopt the 15-minute concept. For the estimation of the isochrones an average speed of 4.8 km/h and 14km/h was used for walking and cycling, respectively [

30]. A key limitation of this study is that it applies fixed average speeds for walking and cycling, without accounting for variations among different population groups. In real-world conditions, these speeds can vary significantly depending on age, physical ability, and other demographic factors. For instance, elderly individuals, people with disabilities, or families with small children may walk or cycle at much slower speeds, which would reduce their actual 15-minute coverage area. This highlights the need for planning authorities to consider inclusivity when assessing or implementing the 15-minute city concept. As suggested by Carvalho et al. (2025) [

31], locally adapted time thresholds and metrics are crucial for ensuring that proximity-based policies like the 15-minute city serve all populations equitably, especially in sprawled or segregated urban contexts.

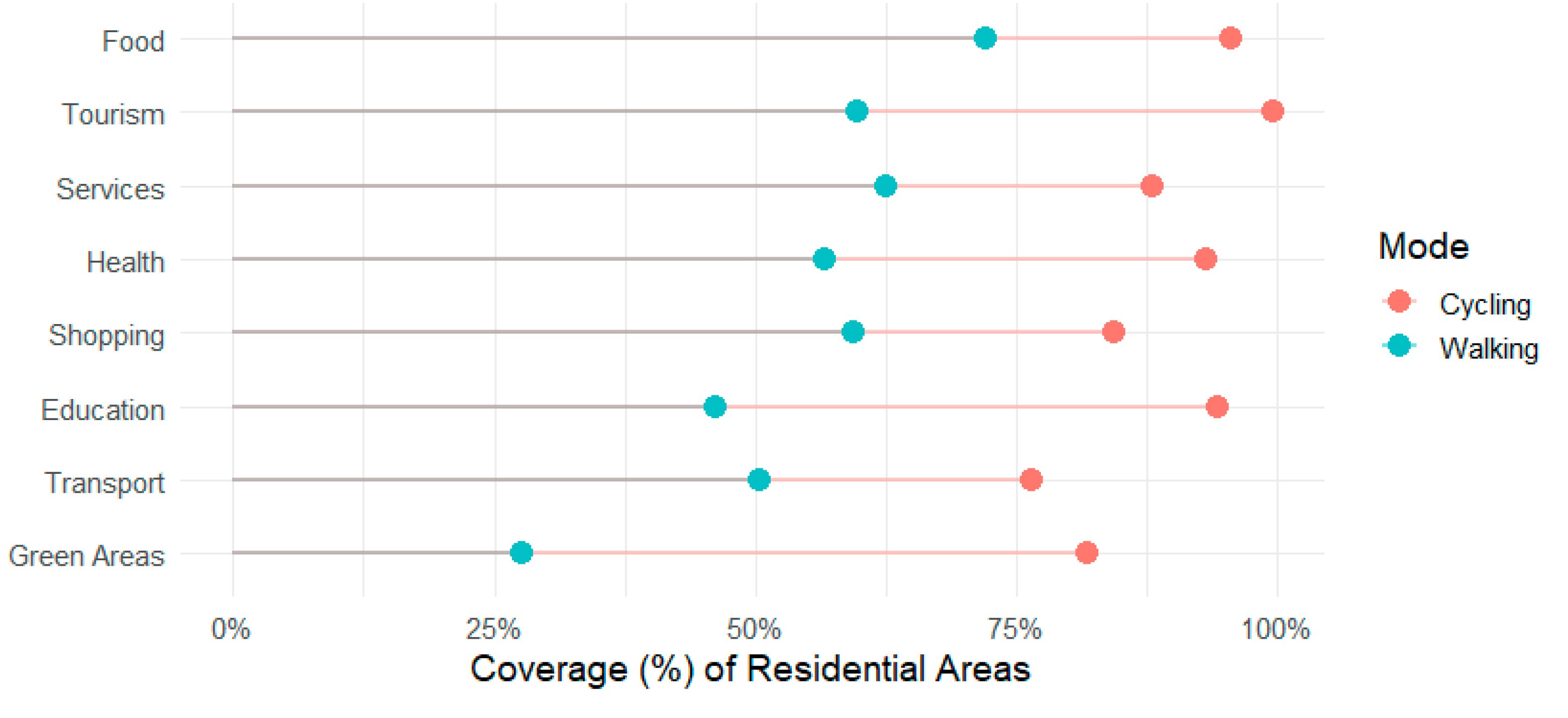

Figure 8 highlights the disparities in 15-minute accessibility to key urban functions in Limassol, differentiated by walking and cycling. Across nearly all categories, cycling offers substantially greater coverage of residential areas compared to walking. However, it must be noted that isochrones produced for 15-minute cycling considered the entire road network of the city and not just cycleways, since many people use road as share space for cycling. Categories such as Food, Services, and Shopping show the highest levels of accessibility, with cycling coverage approaching or exceeding 90%, while walking coverage remains moderate. This suggests that many essential amenities are within a reachable distance by bike, supporting the feasibility of shifting short-distance trips from cars to active transport modes. On the other hand, walking accessibility is notably limited for categories such as Green Areas, Transport, and Education, reflecting a spatial mismatch between residential zones and certain key services, particularly those typically located on the periphery or in centralized clusters.

These findings underscore both the opportunities and the challenges Limassol faces in its pursuit of the 15-minute city model. While the existing urban form allows for relatively strong cycling accessibility to many amenities, the limited walkable coverage reveals a need for targeted interventions, such as decentralizing certain services, improving pedestrian infrastructure, and strategically introducing new POIs in underserved residential areas. Particularly in categories like Green Areas and Transport, the low walkability scores indicate potential equity issues for populations without access to private vehicles or bicycles. Therefore, while Limassol shows potential for adopting a polycentric, human-scaled city model, significant improvements in local planning and investment in active mobility infrastructure are essential to ensure balanced and inclusive accessibility across all urban functions.

The results of the spatial and accessibility analysis for Limassol highlight both opportunities and challenges for advancing the 15-minute city model in the context of urban sprawl and car dependency. While the analysis reveals relatively high cycling accessibility to many essential functions, walking accessibility remains limited, especially in peripheral residential areas. These findings are consistent with broader research suggesting that low-density, unplanned urban expansion impedes walkability and undermines proximity-based planning goals [

2]. Moreover, as Elldér (2024) [

32] emphasizes, increasing population density and promoting mixed land uses are essential built environment factors for advancing 15-minute city transformations. In this regard, Limassol will likely require zoning reforms and land use adjustments to redistribute amenities more equitably and enhance access through active mobility, especially for categories such as green areas, education, and healthcare.

However, achieving spatial proximity is only one part of the equation. As Maciejewska et al. (2025) [

33] argue, modern urban lifestyles are shaped by diverse activity patterns and social networks that often extend beyond a 15-minute travel radius. Without policies that actively discourage private car use, the availability of nearby destinations may instead facilitate longer and more specialized trips. This reveals the need for complementary strategies that tackle both behavioral and infrastructural challenges. Furthermore, the use of fixed walking and cycling speeds in this analysis, while grounded in existing research (Radics et al., 2024), points to a limitation in inclusivity. Planners must account for different mobility needs, especially among older adults, people with disabilities, or households with children, where slower speeds or physical barriers may reduce effective accessibility.

Emerging technologies such as Digital Twins (DTs) are increasingly seen as valuable tools for simulating urban systems and supporting the practical implementation of the 15-minute city concept, especially by enhancing public understanding and enabling more adaptive, evidence-based planning strategies [

34]. For a city like Limassol, adopting this concept requires a structured approach that includes clearly defined goals and targets, a phased implementation strategy, either citywide or at the neighborhood level, and actions across several key domains. These include promoting sustainable urban mobility, fostering people-centered public spaces, improving smart logistics and service delivery, and advancing inclusive urban governance for mobility transition. Additional criteria involve the prioritization of walking and cycling infrastructure, land use reforms to support mixed-use development and urban densification, and the integration of participatory planning practices and evaluation frameworks to ensure long-term sustainability [

35]

4. Conclusions

This study provides a detailed spatial analysis of Limassol’s urban structure and accessibility landscape, revealing the challenges and opportunities for transitioning toward a 15-minute city. The findings highlight the city’s strong reliance on car-based mobility and centralized service delivery, outcomes of planning policies and economic incentives that encouraged urban sprawl. Despite recent polycentric development trends, many essential functions remain poorly connected to residential areas within walking distance. While cycling infrastructure extends reach significantly, its coverage remains fragmented and non-inclusive of vulnerable populations.

In the case of Limassol, the adoption of the 15-minute city concept offers a valuable framework to improve urban equity, reduce congestion, and promote sustainable mobility. However, such a transformation demands substantial policy shifts, including decentralizing amenities, improving pedestrian and cycling networks, and encouraging mixed-use development. Particular attention should be given to underserved areas where access to education, healthcare, green spaces, and public services is currently limited. Urban revitalization policies and participatory planning are essential to ensure that these changes meet the needs of all residents, including those with limited mobility.

Future applications of this work could involve dynamic simulations using Digital Twin technologies to test planning scenarios and infrastructure interventions in real time. By integrating socio-demographic data and behavioral patterns, planners can tailor accessibility metrics more inclusively. Extending this analysis to other Cypriot cities or comparing findings across Mediterranean coastal urban areas could further contextualize Limassol’s development model and guide national urban policy. The 15-minute city should not remain a conceptual ambition but evolve into an operational strategy for shaping healthier, more resilient urban environments.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, P.N., S.B. and B.I.; methodology, S.B., P.N. and B.I.; software, P.N.; validation P.N., S.B. and B.I.; formal analysis, P.N.; investigation, P.N., S.B. and B.I.; data curation, P.N.; writing, original draft preparation, P.N.; writing, review and editing, S.B. and B.I.; visualization, P.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

References

- UN-Habitat (2022). World Cities Report 2022. Envisaging the Future of Cities. https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2022/06/wcr_2022.pdf.

- United Nations (2024). The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2024. [online] United Nations, pp.1–51. Available at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2024/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2024.pdf.

- United Nations (n.d.). The 17 sustainable development goals. [online] United Nations. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals.

- Yu, H., Zhu, S., Li, J.V. and Wang, L. (2024). Dynamics of urban sprawl: Deciphering the role of land prices and transportation costs in government-led urbanization. Jour-nal of Urban Management. [online] doi:. [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, K., Jarallah Al-Zubaidi, A.M., Qelichi, M.M. and Dolatkhahi, K. (2025). Un-derstanding urban sprawl in Baqubah, Iraq: A study of influential factors. Journal of Urban Management. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Rosati, R.M. (2024). Urban Sprawl and Routing: A Comparative Study on 156 European Cities. Landscape and Urban Planning, [online] 253, pp.105205–105205. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.H. and Antipova, A. (2024). Structural equation model in exploring urban sprawl and its impact on commuting time in 162 US urbanized areas. Cities, [online] 148, p.104855. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Kakar, K.A. and Prasad, C.S.R.K. (2020). Impact of Urban Sprawl on Travel Demand for Public Transport, Private Transport and Walking. Transportation Research Procedia, 48, pp.1881–1892. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. (2024). Quantifying urban sprawl and investigating the cause-effect links among urban sprawl factors, commuting modes, and time: A case study of South Ko-rean cities. Journal of Transport Geography, 121, p.104009. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Moreno C (2016) The quarter-hour city: for a new chrono-urban planning. Available at: https://www.latribune.fr/regions/smart-cities/la-tribunede-carlos-moreno/la-ville-du-quart-d-heure-pour-un-nouveau-chronourbanisme-Allam604358.html (accessed 28 July 2025).

- Caprotti, F., Duarte, C. and Joss, S. (2024). Paranoid Urbanism, Post-Political Urban Practice and Ten Critical Reflections on the 15-Minute City. [online] doi:. [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, D., Szafrańska, E. & Korolko, M. (2024). The 15-minute city: assumptions, opportunities and limitations. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-economic Series, 66(66): 137-151. DOI: http://doi.org/10.12775/bgss-2024-0038.

- Brennan-Horley, C., Gibson, C., Wolifson, P., McGuirk, P., Cook, N. and Warren, A. (2025). Lived experiences of the x-minute creative city: Front and back spaces of crea-tive work. Cities, 162, p.105938. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Basbas, S., Campisi, T., Papas, T., Trouva, M. and Tesoriere, G. (2023). The 15-Minute City Model: The Case of Sicily during and after COVID-19. Communications - Scientific letters of the University of Zilina. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Papas, T., Basbas, S. and Campisi, T. (2023). Urban mobility evolution and the 15-minute city model: from holistic to bottom-up approach. Transportation Research Procedia, 69, pp.544–551. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Kostas Mouratidis (2024). Time to challenge the 15-minute city: Seven pitfalls for sus-tainability, equity, livability, and spatial analysis. Cities, 153, pp.105274–105274. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., Li, Y., Chuang, I-Ting., Qiao, W., Jiang, J. and Beattie, L. (2024). Evaluating the 15-minute city paradigm across urban districts: A mobility-based approach in Hamil-ton, New Zealand. Cities, 151, pp.105147–105147. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, P. and Basbas, S. (2023). Urban Development and Transportation: Investi-gating Spatial Performance Indicators of 12 European Union Coastal Regions. Land, 12(9), pp.1757–1757. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C., Allam, Z., Chabaud, D., Gall, C. and Pratlong, F. (2021). Introducing the ‘15-Minute City’: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities. Smart Cities, [online] 4(1), pp.93–111. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X., Jia, N., Su, X., Adams, M.D., Deng, Y. and Ling, S. (2025). Assessing the ap-plicability of the 15-minute city: Insights from a spatial accessibility perspective. Transportation Research Part A Policy and Practice, 199, pp.104579–104579. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Petrova-Antonova, D., Murgante, B., Malinov, S., Nikolova, S. and Ilieva, S. (2025). Walkability analysis of Sofia’s neighborhoods powered by 15-minute city concept. Cit-ies, 165, p.106171. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Liu, X., Sun, T., Ma, N. and Zhang, T. (2025). Compact urban morphology and the 15-minute city: Evidence from China. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 196, p.104482. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Crutcher, A.J.I.U. (n.d.). Is it really the end for Cyprus’s golden passports? [online] www.aljazeera.com. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/10/16/is-this-really-the-end-for-cypruss-golden-passports.

- Abebe, Fentahun. (2025). Urban Sprawl and Its Implications on Land Use/Land Cover Dynamics: The Case Bahir Dar City. 10.13140/RG.2.2.31542.61761.

- data.gov.cy. (2025). | National Open Data Portal. [online] Available at: https://www.data.gov.cy/ [Accessed 4 Aug. 2025].

- Moi.gov.cy. (2015). | Department of Town Planning and Housing. [online] Available at: https://www.moi.gov.cy/moi/tph/tph.nsf/developmentplansold_table_el/developmentplansold_table_el?OpenForm [Accessed 4 Aug. 2025].

- Europa.eu. (2025). Limiting urban sprawl into green spaces and agricultural land | Green Best Practice Community. [online] Available at: https://greenbestpractice.jrc.ec.europa.eu/node/397.

- OpenStreetMap contributors. (2015) Planet dump. [online] Available at: https://planet.openstreetmap.org [Accessed 4 Aug. 2025].

- Shoina, M., Voukkali, I., Anagnostopoulos, A., Papamichael, I., Stylianou, M. and Zorpas, A.A. (2024). The 15-minute city concept: The case study within a neighbour-hood of Thessaloniki. Waste Management & Research The Journal for a Sustainable Circular Economy, 42(8). doi:. [CrossRef]

- Radics, M., Panayotis Christidis, Alonso, B. and dell’Olio, L. (2024). The X-Minute City: Analysing Accessibility to Essential Daily Destinations by Active Mobility in Seville. Land, 13(10), pp.1656–1656. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Thiago Carvalho, Steven Farber, Kevin Manaugh & Ahmed El-Geneidy (2025). As-sessing the readiness for 15-minute cities: a literature review on performance metrics and implementation challenges worldwide, Transport Reviews, DOI: 10.1080/01441647.2025.2513530.

- Elldér, E. (2024). Built environment and the evolution of the ‘15-minute city’: A 25-year longitudinal study of 200 Swedish cities. Cities, 149, pp.104942–104942. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Maciejewska, M., Cubells, J. and Marquet, O. (2025). When proximity is not enough. A sociodemographic analysis of 15-minute city lifestyles. Journal of Urban Mobility, 7, p.100119. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z., Bibri, S.E., Jones, D.S., Chabaud, D. and Moreno, C. (2022). Unpacking the ‘15-Minute City’ via 6G, IoT, and Digital Twins: Towards a New Narrative for Increas-ing Urban Efficiency, Resilience, and Sustainability. Sensors, 22(4), p.1369. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, J.F., Silva, C., Seisenberger, S., Büttner, B., McCormick, B., Papa, E. and Cao, M. (2024). Classifying 15-minute Cities: A review of worldwide practices. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 189, p.104234. doi:. [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, B. (2019). Ageing in Suburban Neighbourhoods: Planning, Densities and Place Assessment. Urban Planning, 4(2), 18-30. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).