Submitted:

21 August 2025

Posted:

21 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mapping Inclusive Proximity: Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey-Based Assessment: Identifying User Priorities

2.2. General Accessibility Mapping Using Radial Distance Analysis

2.3. Detailed Accessibility Maps and Route Scoring

| Accesibility Criterion | Caracteristics | Points | |

| Non-Disabled Users | public lighting | No lighting / broken | 0 / 1 (Absent) |

| Sparse / dim / inconsistent | 0,5 / 1 (Partial) | ||

| Uniform, bright, functional | 1 / 1 (Existent) | ||

| pleasant atmosphere | No vegetation / noise / unwelcoming | 0 / 1 (Absent) | |

| Minimal greenery / noise / dirty | 0,5 / 1 (Partial) | ||

| Green, quiet, aesthetically pleasant | 1/ 1 (Present) | ||

| cleanliness of the route | Littered, neglected | 0 / 1 (Absent) | |

| Intermittent cleaning | 0,5 / 1 (Partial) | ||

| Clean, well-maintained route | 1/ 1 (Present) | ||

| MAXIMUM POINTS FOR NON-DISABLED USERS’ CRITERIONS | 3 | ||

| Visual Impaired Users | public lighting, | No lighting / broken | 0 / 1 (Absent) |

| Sparse / dim / inconsistent | 0,5 / 1 (Partial) | ||

| Uniform, bright, functional | 1 / 1 (Existent) | ||

| surface quality of the route, | Rough / damaged / uneven | 0 / 1 (Absent) | |

| Mixed paving or partial obstacles | 0,5 / 1 (Partial) | ||

| Smooth, continuous, tactile-safe | 1 / 1 (Existent) | ||

| low interaction with traffic | Constant vehicular interference | 0 / 1 (Absent) | |

| Occasional crossing danger | 0,5 / 1 (Partial) | ||

| Protected, separated walk | 1 / 1 (Existent) | ||

| MAXIMUM POINTS / VISUAL IMPAIRED USERS’ CRITERIONS | 3 | ||

| Mobility Impaired Users | public lighting | No lighting / broken | 0 / 1 (Absent) |

| Sparse / dim / inconsistent | 0,5 / 1 (Partial) | ||

| Uniform, bright, functional | 1 / 1 (Existent) | ||

| presence of urban furniture | No benches or rest zones | 0 / 1 (Absent) | |

| Few benches, hard to reach | 0,5 / 1 (Partial) | ||

| Frequent benches, accessible | 1 / 1 (Existent) | ||

| surface quality of the route | Cracked / uneven / inaccessible | 0 / 1 (Absent) | |

| Some smooth, some inaccessible | 0,5 / 1 (Partial) | ||

| Flat, continuous, step-free | 1 / 1 (Existent) | ||

| MAXIMUM POINTS / MOBILITY IMPAIRED USERS’ CRITERIONS | 3 | ||

3. Results

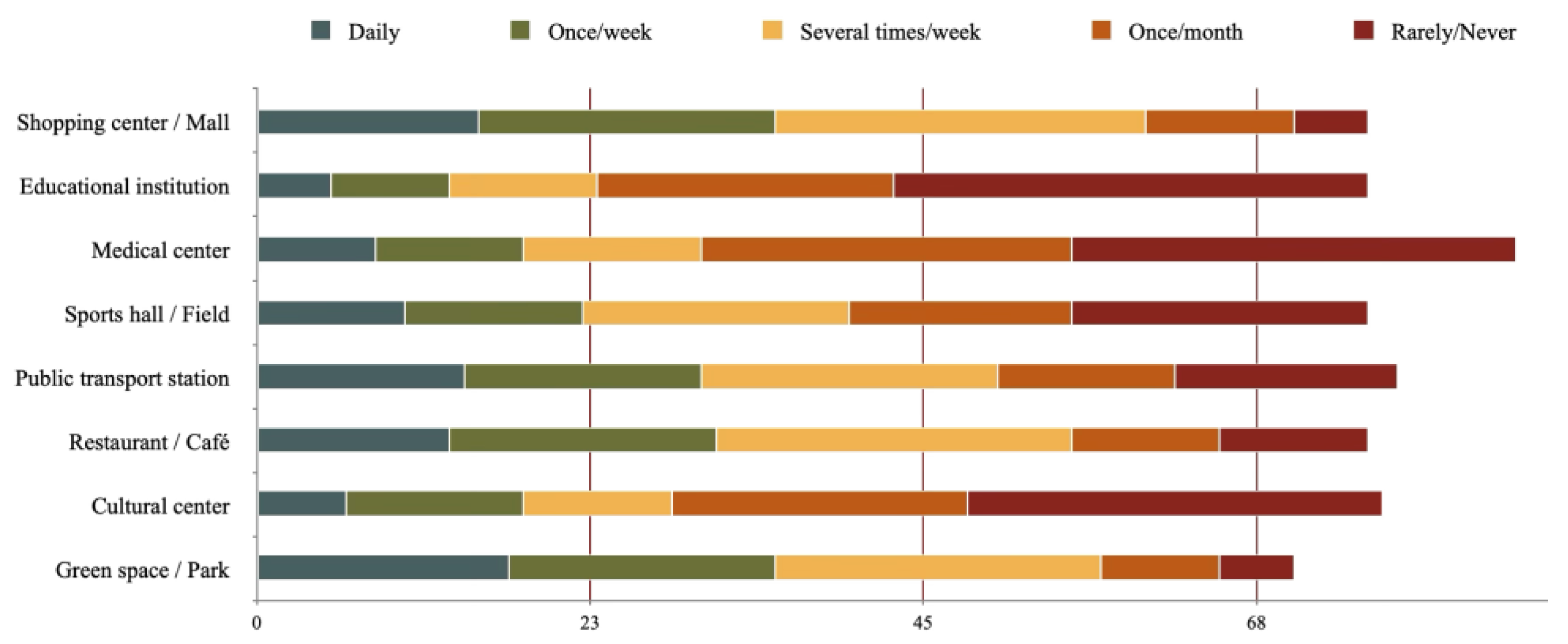

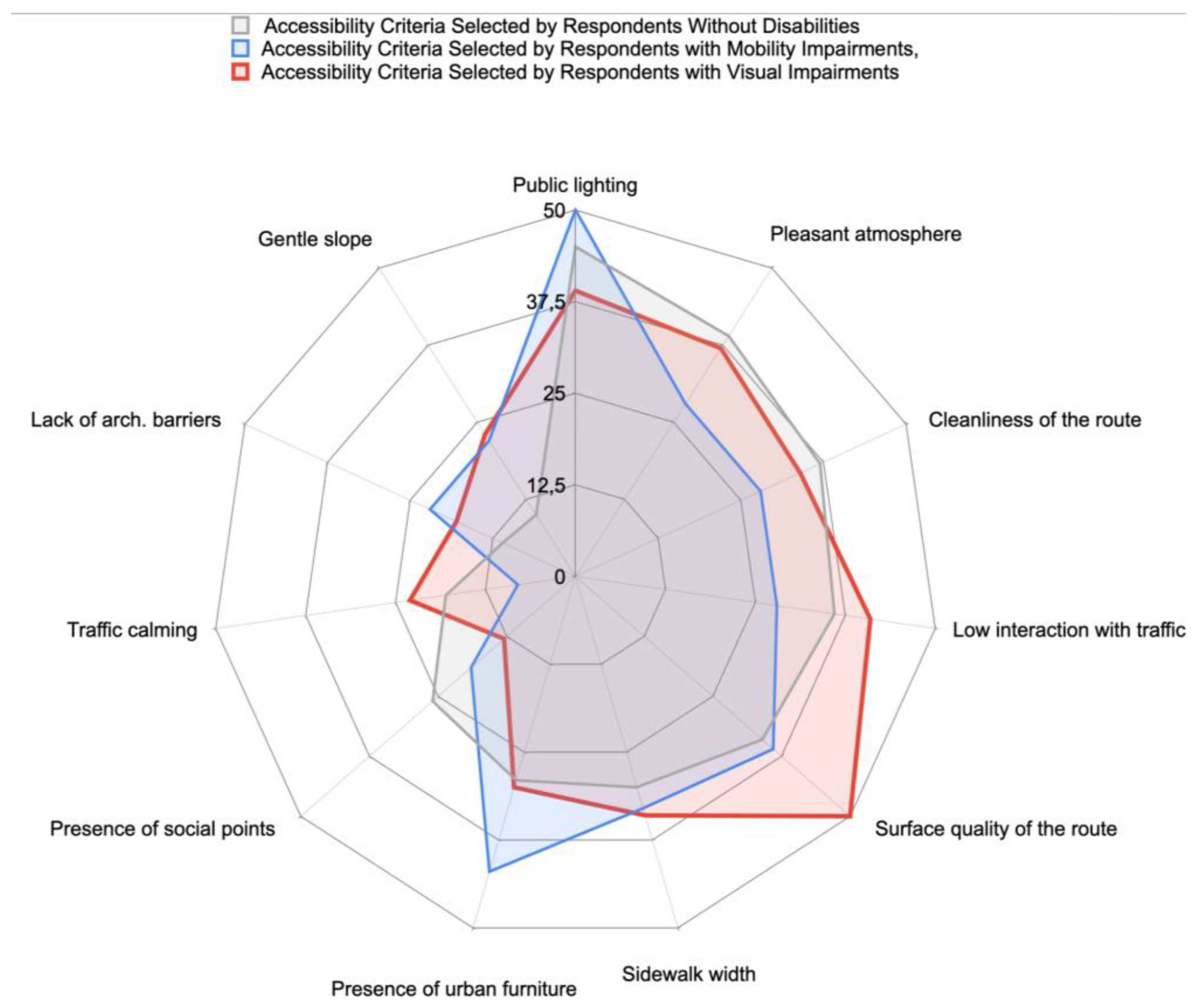

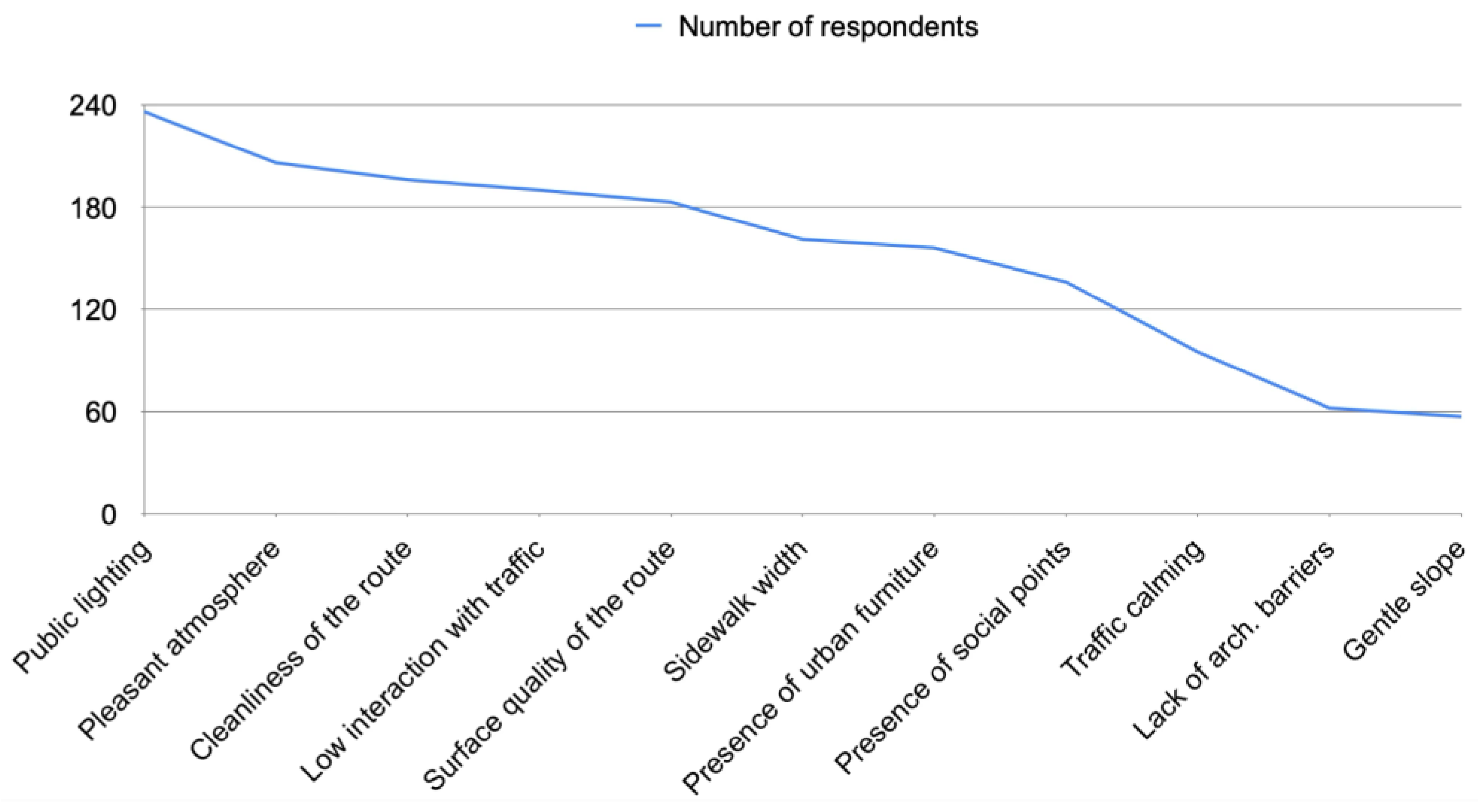

3.1. Residents' Prioritization of Urban Accessibility Feature

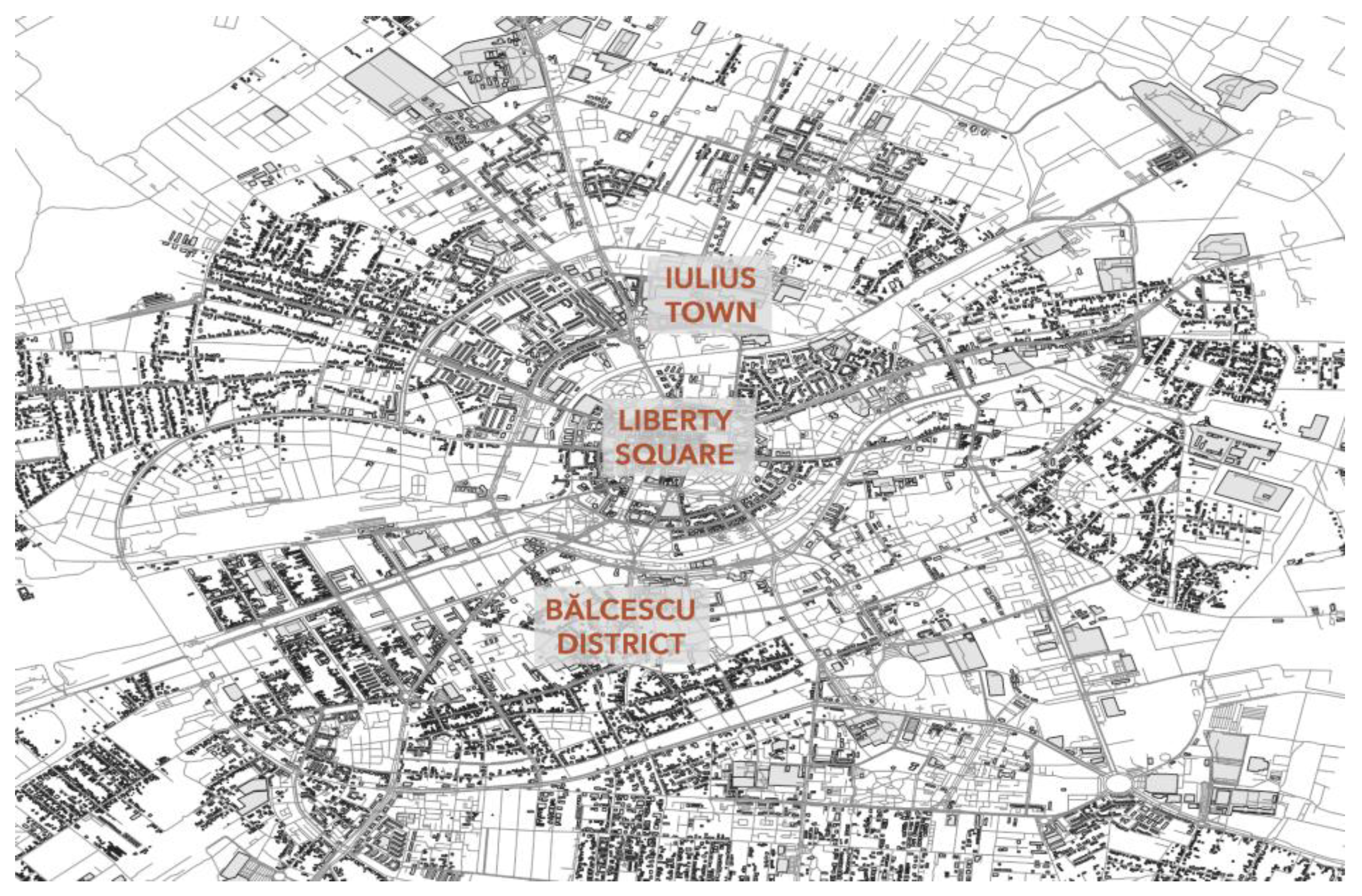

3.2. Spatial Disparities in Proximal Based Accessibility

- Normal speed walking (NSW): calculated for a 15-minute walking radius, using an average speed of 1.2 m/s [22],representing the general population;

3.3. Local Micro-Mapping of Accessibility Zones

3.3.1. Iosefin / Bălcescu

- public lighting: some areas are poorly lit or have unevenly distributed light (photo C), especially around building corners or on side streets: 0,5 points out of 1 point;

- pleasant atmosphere: although the nearby park offers a relaxing atmosphere, the presence of groups standing in front of shops and the noise from traffic, especially near the Profi supermarket, affect comfort.: 0,5 points out of 1 point;

- cleanliness of the route: sidewalks are generally clean, without piles of garbage or construction debris – photo B (speed limiter) and photo F (tactile pavement) indicate decent maintenance: 1 point out of 1 point.

- Visually impaired users: final score - 1,5 out of 3 points:

- public lighting: inconsistent, especially near pedestrian crossings and corners – reduced visibility (photo C). 0,5 points out of 1 point;

- quality of walking surface: sidewalks have variable textures and obstacles such as scaffolding Photo A), but poorly marked bicycle lanes (Photo D): 0,5 points out of 1 point;

- Low interaction with traffic: There are tactile mats at pedestrian crossings (Photo F), but there are no acoustic signals (Photo H), making crossing unsafe: 0,5 points out of 1 point.

- Users with reduced mobility - final score: 1 out of 3 points:

- public lighting: same issues as for the other groups – photo C shows poor lighting in key areas - 0,5 points out of 1 point;

- presence of street furniture: there are no observable benches or rest areas on the analyzed segment – none of the images show such facilities - 0 points out of 1 point;

- surface quality: Photo E and Photo G confirm the existence of ramps that facilitate access, but Photo A also indicates occasional obstacles (construction scaffolding). The surface is uneven in some areas - 0,5 points out of 1 point.

3.3.2. City Center

- Public lighting: In central areas, lighting is adequate, but on side streets, rich vegetation and irregular positioning of poles reduce visibility (Photo C). - 0,5 points out of 1 point;

- Pleasant atmosphere: Lively public spaces, the presence of cultural events and intense commercial activity contribute to a positive experience (Photo D) - 1 point out of 1 point;

- Cleanliness: Sidewalks and pedestrian areas are well maintained, without visible litter, contributing to a perception of urban quality - 1 point out of 1 point.

- public lighting: although the main streets are well lit, the uneven lighting on secondary routes creates difficulties in spatial orientation (Photo C) - 0,5 points out of 1 point;

- quality of walking surface: Sidewalks are often obstructed by obstacles such as low signal poles (Photo B), trees or disorganized street furniture (Photo A). Tactile paving is sporadically present (Photo G) - 0,5 points out of 1 point;

- low interaction with traffic: The pedestrian crossing at the Cathedral has no acoustic signal (Photo H), and this is repeated at other major intersections - 0,5 points out of 1 point.

- public lighting: visibility is reasonable, but lighting problems on adjacent streets can affect the safety of people in wheelchairs or with walking difficulties (Photo C) - 0,5 points out of 1 point;

- presence of street furniture: benches and rest areas are present, but not always accessible or comfortable for users with disabilities (Photo F) - 0,5 points out of 1 point;

- surface quality: ramps are present in many places (not directly illustrated in the images), but stairs at some entrances (Photo E) with limited access for wheelchairs. Sidewalks are generally free of significant obstacles - 0,5 point out of 1 point.

3.3.3. Iulius Town / Circumvalatiunii

- public lighting: combines cool and warm light sources, from street and commercial lighting (photo C). Excellent visibility even at night - 1 point;

- pleasant atmosphere: the area is lively, safe and well-maintained. Green spaces, terraces and commercial activity create a positive urban setting (photo A) - 1 point;

- cleanliness: the entire area has been recently modernized and cleanliness is evident on the sidewalks and public spaces (photo A) - 1 point.

- public lighting: Ensures adequate visibility for orientation and personal safety - 1 point out of 1 point;

- quality of walking surface: The sidewalks are wide, flat, without obstacles, facilitating movement (Photo D). Tactile pavement is present, but implemented unevenly (Photo C & E) or intersected by poorly demarcated bike lanes (Photo F) - 0,5 points out of 1 point;

- low interaction with traffic: all traffic lights in the area have functional acoustic signals (Photo B) - 1 point out of 1 point.

- public lighting: Good visibility along the entire route - 1 point out of 1 point;

- presence of urban furniture: Formal benches are missing in some areas, but there are improvised options (planter edges, low platforms) - 0,5 points out of 1 point;

- surface quality: ramps are functional, without high curbs or narrow alleys, which allows easy access to all functions - 1 point out of 1 point.

4. Limits

- presence of continuous tactile or audible landmarks;

- clarity of chromatic contrast for signs;

- uniform and coherent tactile paving;

- functional audible signaling at pedestrian crossings;

5. Conclusions

- revise the research instruments (especially the questionnaire),

- extend the analysis to other urban functions and interior spaces,

- integrate direct participatory components, through the active involvement of people with disabilities in validating the results,

- use digital tools (applications, sensors, interactive maps) to obtain additional objective data on real mobility experiences.

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

| 15mC | 15-Minute City |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| NSW | Normal-Speed Walk |

| SSW | Slow-Speed Walk |

| OSM | OpenStreetMap |

| ToD | Transit-oriented Development |

| UD | Universal Design |

| ITDP | Institute for Transportation and Development Policy |

| PI | Proximity Index (dacă ai folosit un indice compozit de proximitate) |

| VI | Visually Impaired |

| MI | Mobility Impaired |

| ND | Non-Disabled |

References

- S. Brain, “The 15 minutes-city: for a new chrono-urbanism! - Pr Carlos Moreno,” Carlos Moreno. Accessed: , 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.moreno-web. 17 June.

- Papas, T.; Basbas, S.; Campisi, T. Urban mobility evolution and the 15-minute city model: from holistic to bottom-up approach. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C40 Cities Climate Leadership Guide. How to Build Back Better with a 15-Minute City: Implementation Guide. C40 Cities. 2020. Available online: https://www.c40knowledgehub.org/s/article/How-to-build-back-better-with-a-15-minute-city?language=en_US (accessed on day month year).

- Garden Cities of To-Morrow, by Ebenezer Howard--The Project Gutenberg eBook.” Accessed: , 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/46134/46134-h/46134-h. 17 June.

- P. Calthorpe, The next American metropolis : ecology, community, and the American dream. New York : Princeton Architectural Press, 1993. Accessed: , 2025. [Online]. Available: http://archive. 17 June 0000.

- Vais, D. Type Projects as Tools: Housing Type Design in Communist Romania. Arch. Hist. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The In-between Space: Romanian Mass Housing Public Space as a Playground in the Collective Memory | Docomomo Journal.” Accessed: , 2025. [Online]. Available: https://docomomojournal.com/index. 17 June.

- L. Artieda, M. L. Artieda, M. Allan, R. Cruz, S. Shah, and V. S. Pineda, “Access and Persons with Disabilities in Urban Areas”.

- Barriers to disabled travel eased in 15-minute cities.” Accessed: , 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.movinonconnect. 17 June.

- The role of GIS in promoting the 15-minute city concept for Sustainabl’ by Eman Metwally, Yara Menshway et al.” Accessed: , 2025. [Online]. Available: https://mej.researchcommons. 22 June.

- Caselli, B. From urban planning techniques to 15-minute neighbourhoods. A theoretical framework and GIS-based analysis of pedestrian accessibility to public services. Eur. Transp. Eur. 2021; 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour, N.M.; Partanen, J. Planning for the urban future: two-level spatial analysis to discover 15-Minute City potential in urban area and expansion in Tallinn, Estonia. J. Comput. Soc. Sci. 2024, 7, 777–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PDF) The 15-minute city: assumptions, opportunities and limitations.” Accessed: , 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate. 22 June 3873.

- A universal framework for inclusive 15-minute cities | Nature Cities.” Accessed: , 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature. 22 June 4428.

- Abbiasov, T.; Heine, C.; Sabouri, S.; Salazar-Miranda, A.; Santi, P.; Glaeser, E.; Ratti, C. The 15-minute city quantified using human mobility data. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2024, 8, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PDF) Quantifying walkable accessibility to urban services: An application to Florence, Italy.” Accessed: , 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate. 22 June 3908.

- Barriers and facilitators of public transport use among people with disabilities: a scoping review - PubMed.” Accessed: , 2025. [Online]. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. 22 June 3828.

- Chidiac, S.E.; Reda, M.A.; Marjaba, G.E. Accessibility of the Built Environment for People with Sensory Disabilities—Review Quality and Representation of Evidence. Buildings 2024, 14, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanase and C., M. Povian, “Proximity to Priority_ the 15-Minute City Reframed for Timișoara – Survey-Based Study,” World Summit Civ. Eng.-Archit.-Urban Plan. Congr., p. 9, 2025.

- Wheelmap,” Wheelmap. Accessed: , 2025. [Online]. Available: https://wheelmap. 22 June.

- TravelTime Location API | Build Without Limits.” Accessed: , 2025. [Online]. Available: https://traveltime. 22 June.

- J. J. Fruin, Pedestrian planning and design. New York: Metropolitan Association of Urban Designers and Environmental Planners, 1971.

- Swenor, B.K.; Bandeen-Roche, K.; Muñoz, B.; West, S.K. Does Walking Speed Mediate the Association Between Visual Impairment and Self-Report of Mobility Disability? The Salisbury Eye Evaluation Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2014, 62, 1540–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahromi, M.N.; Samany, N.N.; Argany, M.; Mostafavi, M.A. Enhancing sidewalk accessibility assessment for wheelchair users: An adaptive weighting fuzzy-based approach. Heliyon 2024, 11, e41101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Amenity Type | Scenario | Uncovered Area (m²) | % of Total Area Not Covered |

| Supermarket | Normal Speed | 23,809 | 20,5% |

| Slow Speed | 54,378 | 46,8% | |

| Medical Center | Normal Speed | 66,237 | 38,0 % |

| Slow Speed | 88,850 | 56,0 % |

| Users | Accessibility Criterion | Maximum Points | Area 1: Iosefin |

Area 2: City Center |

Area 3: Iulius Town |

| Non-Disabled Users | public lighting | 1 | 0,5 / 1 | 0,5 / 1 | 1 / 1 |

| pleasant atmosphere | 1 | 0,5 / 1 | 1 / 1 | 1 / 1 | |

| cleanliness of the route | 1 | 1 / 1 | 1 / 1 | 1 / 1 | |

| TOTAL POINTS / NON-DISABLED USERS | 3 | 2 / 3 | 2,5 / 3 | 3 / 3 | |

| Visual Impaired Users | public lighting, | 1 | 0,5 / 1 | 0,5 / 1 | 1 / 1 |

| surface quality of the route, | 1 | 0,5 / 1 | 0,5 / 1 | 0,5 / 1 | |

| low interaction with traffic | 1 | 0,5 / 1 | 0,5 / 1 | 1 / 1 | |

| TOTAL POINTS / VISUAL IMPAIRED USERS | 3 | 1,5 / 3 | 1,5 / 3 | 2,5 / 3 | |

| Mobility Impaired Users | public lighting | 1 | 0,5 / 1 | 0,5 / 1 | 1 / 1 |

| presence of urban furniture | 1 | 0 / 1 | 0,5 / 1 | 0,5 / 1 | |

| surface quality of the route | 1 | 0,5 / 1 | 0,5 / 1 | 1 / 1 | |

| TOTAL POINTS / MOBILITY IMPAIRED USERS | 3 | 1 / 3 | 1,5 / 3 | 2,5 / 3 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).