Submitted:

08 October 2025

Posted:

09 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification and Physicochemical Properties Analysis of TaABCB Members

2.2. Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Tree Construction

2.3. Conserved Motifs and Domains Analysis of TaABCB Members

2.4. Chromosomal Mapping, Gene Duplication, and Collinearity Analysis of TaABCB Members

2.5. Cis-acting Elements Prediction and Gene Structure Analysis

2.6. RNA-seq Analysis

2.7. RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR Analysis

2.8. Computational Analysis of AlphaFold 3

2.9. Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assays

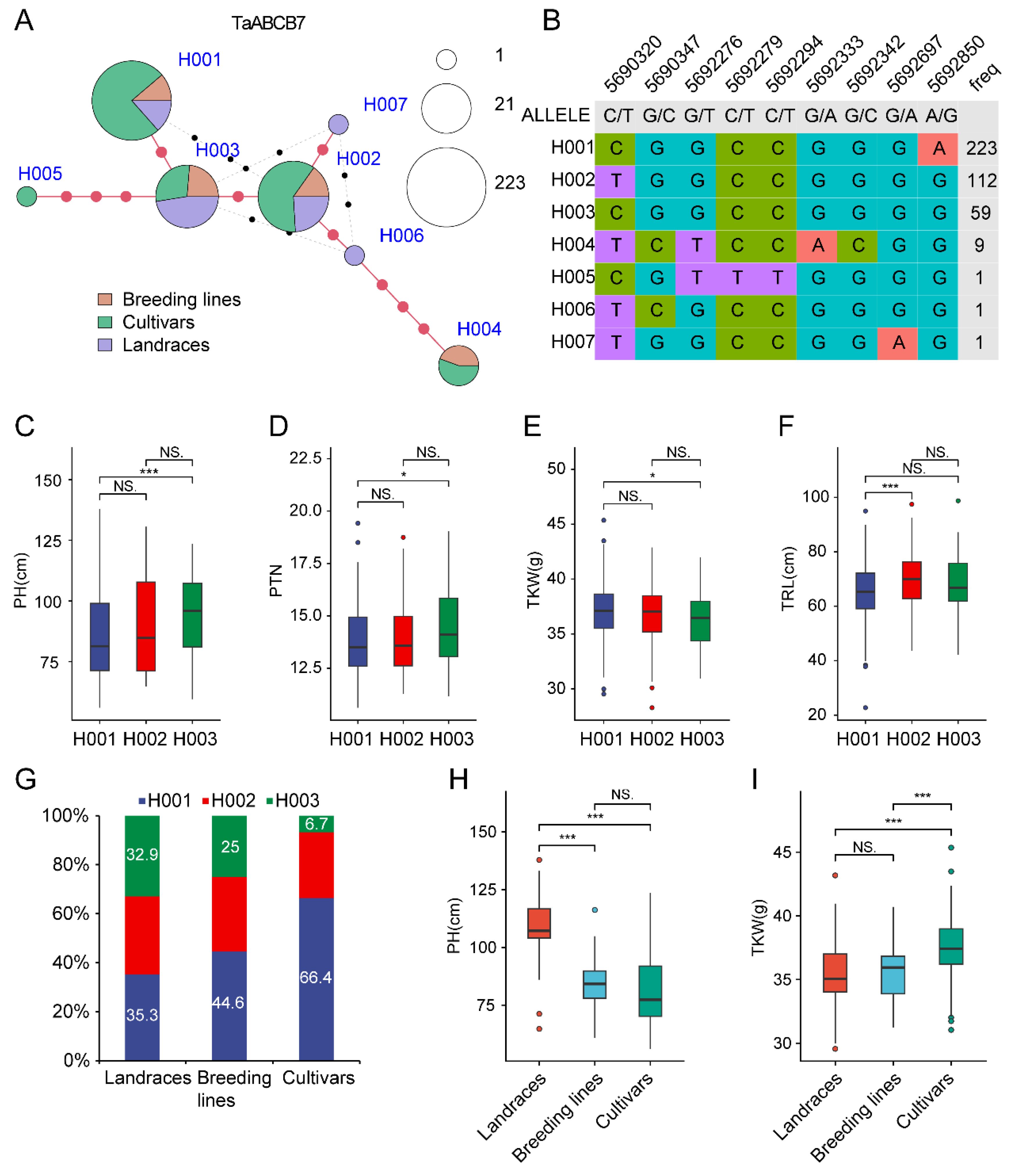

2.10. The Haplotype Analysis of TaABCB7

3. Results

3.1. Identification of TaABCB Gene Family Members in Wheat

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of TaABCB Members

3.3. Conserved Motifs and Domains Analysis of TaABCB Members

3.4. Chromosomal Mapping, Gene Duplication, and Collinearity Analysis

3.5. Cis-acting Elements and Gene Structure Analysis of TaABCB Members

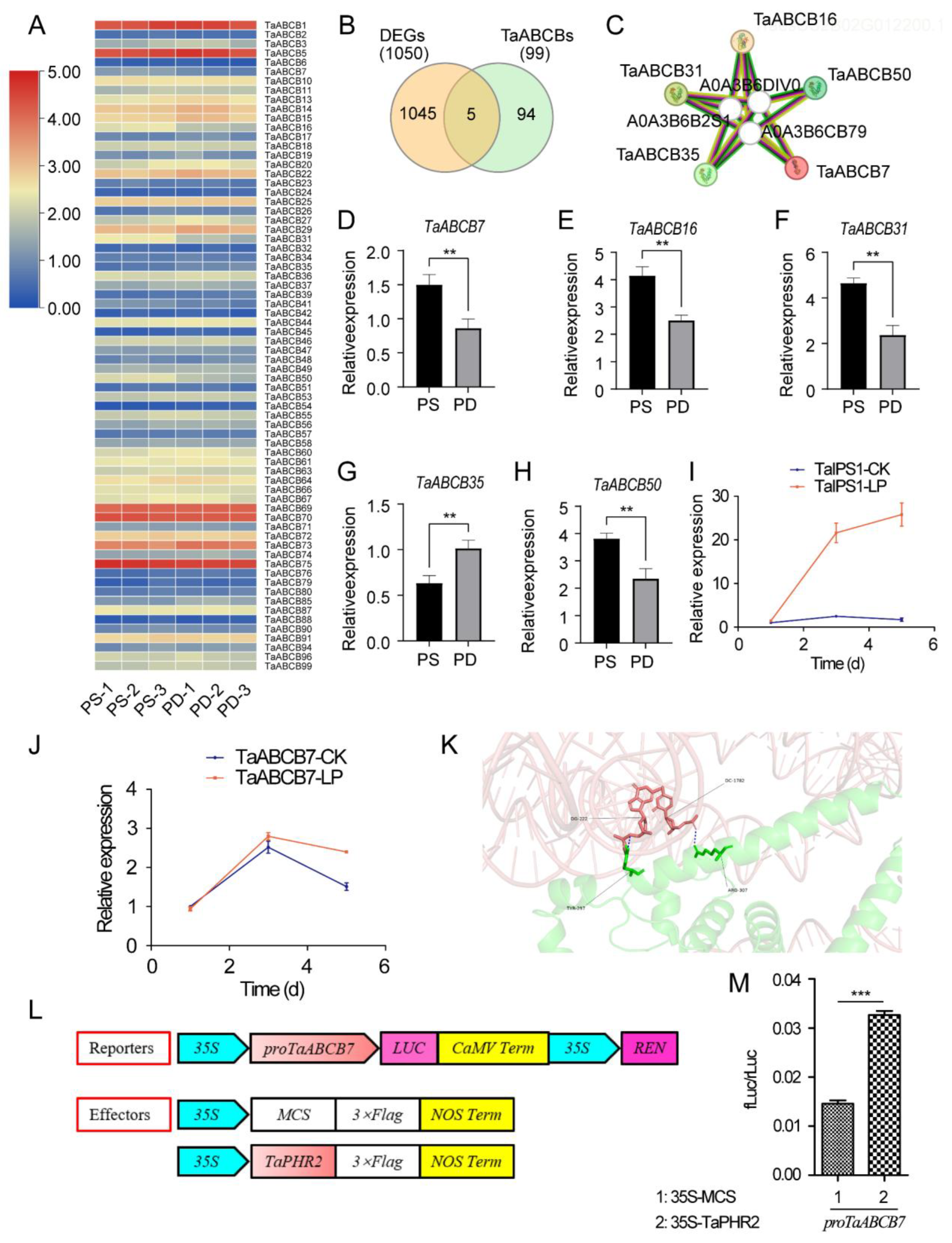

3.6. Phosphorus Starvation Transcriptome Analysis

3.7. Expression Profile of TaABCB Members in Response to Phosphate Starvation and the Analysis of Candidate Gene

3.8. Haplotype Analysis of TaABCB7

4. Discussion

4.1. The Characteristics of TaABCB Members in Wheat

4.2. The Function and Regulatory Mechanism of TaABCB Members in Wheat

4.3. The Haplotype of TaABCB7 in Wheat

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hwang, J.U.; Song, W.; Hong, D.; Ko, D.; Yamaoka, Y.; Jang, S.; Yim, S.; Lee, E.; Khare, D.; Kim, K.; et al. Plant ABC transporters enable many unique aspects of a terrestrial plant’s lifestyle. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 338–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, A.M. ABC transporters 45 years on. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banasiak, J.; Jasinski, M. ATP-binding cassette transporters in nonmodel plants. New Phytol. 2022, 233, 1597–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Ortiz, C.; Dutta, S.K.; Natarajan, P.; Peña-Garcia, Y.; Abburi, V.; Saminathan, T.; Nimmakayala, P.; Reddy, U.K. Genome-wide identification and gene expression pattern of ABC transporter gene family in spp. PloS One 2019, 14, e0215901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.H.T.; Martinoia, E.; Lee, Y.; Hwang, J.U. 2021 update on ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters: how they meet the needs of plants. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 1876–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gräfe, K.; Schmitt, L. The ABC transporter G subfamily in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.H.T.; Martinoia, E.; Lee, Y. Functions of ABC transporters in plant growth and development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2018, 41, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahuja, A.; Kumar, R.R.; Sakhare, A.; Watts, A.; Singh, B.; Goswami, S.; Sachdev, A.; Praveen, S. Role of ATP-binding cassette transporters in maintaining plant homeostasis under abiotic and biotic stresses. Physiol. Plant 2021, 171, 785–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, T.S.; Rempe, C.S.; Davitt, J.; Staton, M.E.; Peng, Y.H.; Soltis, D.E.; Melkonian, M.; Deyholos, M.; Leebens-Mack, J.H.; Chase, M.; et al. Diversity of ABC transporter genes across the plant kingdom and their potential utility in biotechnology. BMC Biotechnol. 2016, 16, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Cho, H.T. The function of ABCB transporters in auxin transport. Plant Signal Behav. 2013, 8, e22990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Bailly, A.; Zwiewka, M.; Henrichs, S.; Azzarello, E.; Mancuso, S.; Maeshima, M.; Friml, J.; Schulz, A.; Geisler, M. Arabidopsis TWISTED DWARF1 functionally interacts with auxin exporter ABCB1 on the root plasma membrane. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchetti, V.; Brunetti, P.; Napoli, N.; Fattorini, L.; Altamura, M.M.; Costantino, P.; Cardarelli, M. ABCB1 and ABCB19 auxin transporters have synergistic effects on early and late Arabidopsis anther development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2015, 57, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrichs, S.; Wang, B.J.; Fukao, Y.; Zhu, J.S.; Charrier, L.; Bailly, A; Oehring, S.C.; Linnert, M.; Weiwad, M.; Endler, A.; et al. Regulation of ABCB1/PGP1-catalysed auxin transport by linker phosphorylation. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 2965–2980.

- Noh, B.; Murphy, A.S.; Spalding, E.P. Multidrug resistance-like genes of Arabidopsis required for auxin transport and auxin-mediated development. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 2441–2454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Noh, B.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Peer, W.A.; Spalding, E.P.; Murphy, A.S. Enhanced gravi- and phototropism in plant mdr mutants mislocalizing the auxin efflux protein PIN1. Nature 2003, 423, 999–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.C.; Wang, H.Y. Two homologous ATP-binding cassette transporter proteins, AtMDR1 and AtPGP1, regulate Arabidopsis photomorphogenesis and root development by mediating polar auxin transport. Plant Physiol. 2005, 138, 949–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, W.; Wang, Y.W.; Wei, H.; Luo, Y.M.; Ma, Q.; Zhu, H.Y.; Janssens, H.; Vukašinović, N.; Kvasnica, M.; Winne, J.M.; et al. Structure and function of the Arabidopsis ABC transporter ABCB19 in brassinosteroid export. Science 2024, 383, eadj4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamimoto, Y.; Terasaka, K.; Hamamoto, M.; Takanashi, K.; Fukuda, S.; Shitan, N.; Sugiyama, A; Suzuki, H.; Shibata, D.; Wang, B.J.; et al. Arabidopsis ABCB21 is a facultative auxin importer/exporter regulated by cytoplasmic auxin concentration. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012, 53, 2090–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenness, M.K.; Carraro, N.; Pritchard, C.A.; Murphy, A.S. The Arabidopsis ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCB21 regulates auxin levels in cotyledons, the root pericycle, and leaves. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubes, M.; Yang, H.B.; Richter, G.L.; Cheng, Y.; Mlodzinska, E.; Wang, X.; Blakeslee, J.J.; Carraro, N.; Petrásek, J.; Zazímalová, E.; et al. The Arabidopsis concentration-dependent influx/efflux transporter ABCB4 regulates cellular auxin levels in the root epidermis. Plant J. 2012, 69, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, M.; Lee, S.H.; Cho, H.T. P-glycoprotein4 displays auxin efflux transporter-like action in Arabidopsis root hair cells and tobacco cells. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 3930–3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Choi, Y.; Burla, B.; Kim, Y.Y.; Jeon, B.; Maeshima, M.; Yoo, J.Y.; Martinoia, E.; Lee, Y. The ABC transporter AtABCB14 is a malate importer and modulates stomatal response to CO2. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 1217–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.X.; Zhang, S.N.; Guo, H.P.; Wang, S.K.; Xu, L.G.; Li, C.Y.; Qian, Q.; Chen, F.; Geisler, M.; Qi, Y.; et al. OsABCB14 functions in auxin transport and iron homeostasis in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant J. 2014, 79, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichikawa, Y.; Bayeva, M.; Ghanefar, M.; Potini, V.; Sun, L.; Mutharasan, R.K.; Wu, R.; Khechaduri, A.; Jairaj Naik, T.; Ardehali, H. Disruption of ATP-binding cassette B8 in mice leads to cardiomyopathy through a decrease in mitochondrial iron export. Proc, Natl, Acad, Sci, U, S, A. 2012, 109, 4152–4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaedler, T.A.; Thornton, J.D.; Kruse, I.; Schwarzländer, M.; Meyer, A.J.; Van Veen, H.W.; Balk, J. A conserved mitochondrial ATP-binding cassette transporter exports glutathione polysulfide for cytosolic metal cofactor assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 23264–23274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Bovet, L.; Kushnir, S.; Noh, E.W.; Martinoia, E.; Lee, Y. AtATM3 is involved in heavy metal resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006, 140, 922–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.X.; Feng, X.; Cao, F.B.; Wu, D.Z.; Zhang, G.P.; Vincze, E.; Wang, Y.Z.; Chen, Z.H.; Wu, F.B. An ATP binding cassette transporter HvABCB25 confers aluminum detoxification in wild barley. J. Hazard Mater 2021, 401, 123371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, P.B.; Cancel, J.; Rounds, M.; Ochoa, V. Arabidopsis ALS1 encodes a root tip and stele localized half type ABC transporter required for root growth in an aluminum toxic environment. Planta 2007, 225, 1447–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.F.; Yamaji, N.; Mitani, N.; Yano, M.; Nagamura, Y.; Ma, J.F. A bacterial-type ABC transporter is involved in aluminum tolerance in rice. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 655–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.F.; Lei, G.J.; Wang, Z.W.; Shi, Y.Z.; Braam, J.; Li, G.X.; Zheng, S.J. Coordination between apoplastic and symplastic detoxification confers plant aluminum resistance. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 1947–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.J.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.H.; Xia, R. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, S.C.; Luciani, A.; Eddy, S.R.; Park, Y.; Lopez, R.; Finn, R.D. HMMER web server: 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Lu, S.N.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; Thanki, N.; Yamashita, R.A.; et al. The conserved domain database in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.N.; Wang, J.Y.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Geer, R.C.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Hurwitz, D.I.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; et al. CDD/SPARCLE: The conserved domain database in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchler-Bauer, A.; Bo, Y.; Han, L.Y.; He, J.E.; Lanczycki, C.J.; Lu, S.N.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Geer, R.C.; Gonzales, N.R.; et al. CDD/SPARCLE: functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.M.; Song, W.J.; Xie, X.M.; Wang, Z.H.; Guan, P.F.; Peng, H.R.; Jiao, Y.N.; Ni, Z.F.; Sun, Q.X.; Guo, W.L. A collineari-ty-incorporating homology inference strategy for connecting emerging assemblies in the triticeae tribe as a pilot practice in the plant pangenomic era. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1694–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savojardo, C.; Martelli, P.L.; Fariselli, P.; Profiti, G.; Casadio, R. BUSCA: an integrative web server to predict subcellular localization of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, K.C.; Shen, H. Cell-PLoc: a package of Web servers for predicting subcellular localization of proteins in various organisms. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, V.N.T.; Moon, S.; Jung, K.H. Genome-wide expression analysis of rice ABC transporter family across spatio-temporal samples and in response to abiotic stresses. J. Plant Physiol. 2014, 171, 1276–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Suleski, M.; Sanderford, M.; Sharma, S.; Tamura, K. MEGA12: Molecular evolutionary genetic analysis version 12 for adaptive and green computing. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.P.; Zhang, Y.B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Yu, J. KaKs Calculator 2.0: a toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 2010, 8, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.F.; Zhou, Y.Q.; Chen, Y.R.; Gu, J. Fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varet, H.; Brillet-Guéguen, L.; Coppée, J.Y.; Dillies, M.A. SARTools: a DESeq2- and EdgeR-based r pipeline for comprehensive differential analysis of RNA-seq data. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0157022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Liu, Z.H.; Shi, X.; Hou, W.Y.; Cheng, M.Z.; Liu, Y.X.; Simmonds, J.; Ji, W.Q.; Uauy, C.; Xu, S.B.; et al. Modern wheat breeding selection synergistically improves above- and belowground traits. Plant Physiol. 2024, 196, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fernández, R.; Davies, T.G.; Coleman, J.O.; Rea, P.A. The Arabidopsis thaliana ABC protein superfamily, a complete inventory. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 30231–30244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, K.Y.; Li, Y.J.; Liu, M.H.; Meng, Z.D.; Yu, Y.L. Inventory and general analysis of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) gene superfamily in maize (Zea mays L.). Gene 2013, 526, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrier, P.J.; Bird, D.; Burla, B.; Dassa, E.; Forestier, C.; Geisler, M.; Klein, M.; Kolukisaoglu, U.; Lee, Y.; Martinoia, E.; et al. Plant ABC proteins-a unified nomenclature and updated inventory. Trends Plant Sci. 2008, 13, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, T.; Ezaki, B.; Matsumoto, H. A gene encoding multidrug resistance (MDR)-like protein is induced by aluminum and inhibitors of calcium flux in wheat. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002, 43, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.S.; Cameron, J.N.; Ljung, K.; Spalding, E.P. A role for ABCB19-mediated polar auxin transport in seedling photomorphogenesis mediated by cryptochrome 1 and phytochrome B. Plant J. 2010, 62, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.T.; Liu, L.; Mo, H.X.; Qian, L.T.; Cao, Y.; Cui, S.J.; Li, X.; Ma, L.G. The ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCB19 regulates postembryonic organ separation in Arabidopsis. PLoS One 2013, 8, e60809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukumar, P.; Maloney, G.S.; Muday, G.K. Localized induction of the ATP-binding cassette B19 auxin trans-porter enhances adventitious root formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 1392–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.R.; Miller, N.D.; Splitt, B.L.; Wu, G.S.; Spalding, E.P. Separating the roles of acropetal and basipetal auxin transport on gravitropism with mutations in two Arabidopsis multidrug resistance-like ABC transporter genes. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 1838–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, J.; Sengupta, A.; Gupta, K.; Gupta, B. Molecular phylogenetic study and expression analysis of ATP-binding cassette transporter gene family in Oryza sativa in response to salt stress. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2015, 54, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, H.E.; Shin, J.J.H.; Bird, D.A.; Samuels, A.L. Arabidopsis ABCG transporters, which are required for export of diverse cuticular lipids, dimerize in different combinations. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 3066–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velu, G.; Singh, R.P.; Huerta, J.; Guzmán, C. Genetic impact of Rht dwarfing genes on grain micronutrients concentration in wheat. Field Crops Res. 2017, 214, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, S.; Yadav, M.; Singh, K.; Jaat, R.S.; Singh, N.K. Exploring diverse wheat germplasm for novel alleles in HMW-GS for bread quality improvement. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 3257–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaveri, E.; Lobell, D.B. The role of irrigation in changing wheat yields and heat sensitivity in India. Nat Commun. 2019, 10, 4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).