Submitted:

08 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Physical Properties Of CsFKBPs

2.2. Evolutions of FKBPs in Different Species

2.3. Gene Structure and Conserved Motif Analysis of CsFKBPs

2.4. Expression Patterns of CsFKBPs Under Different Cold Stresses

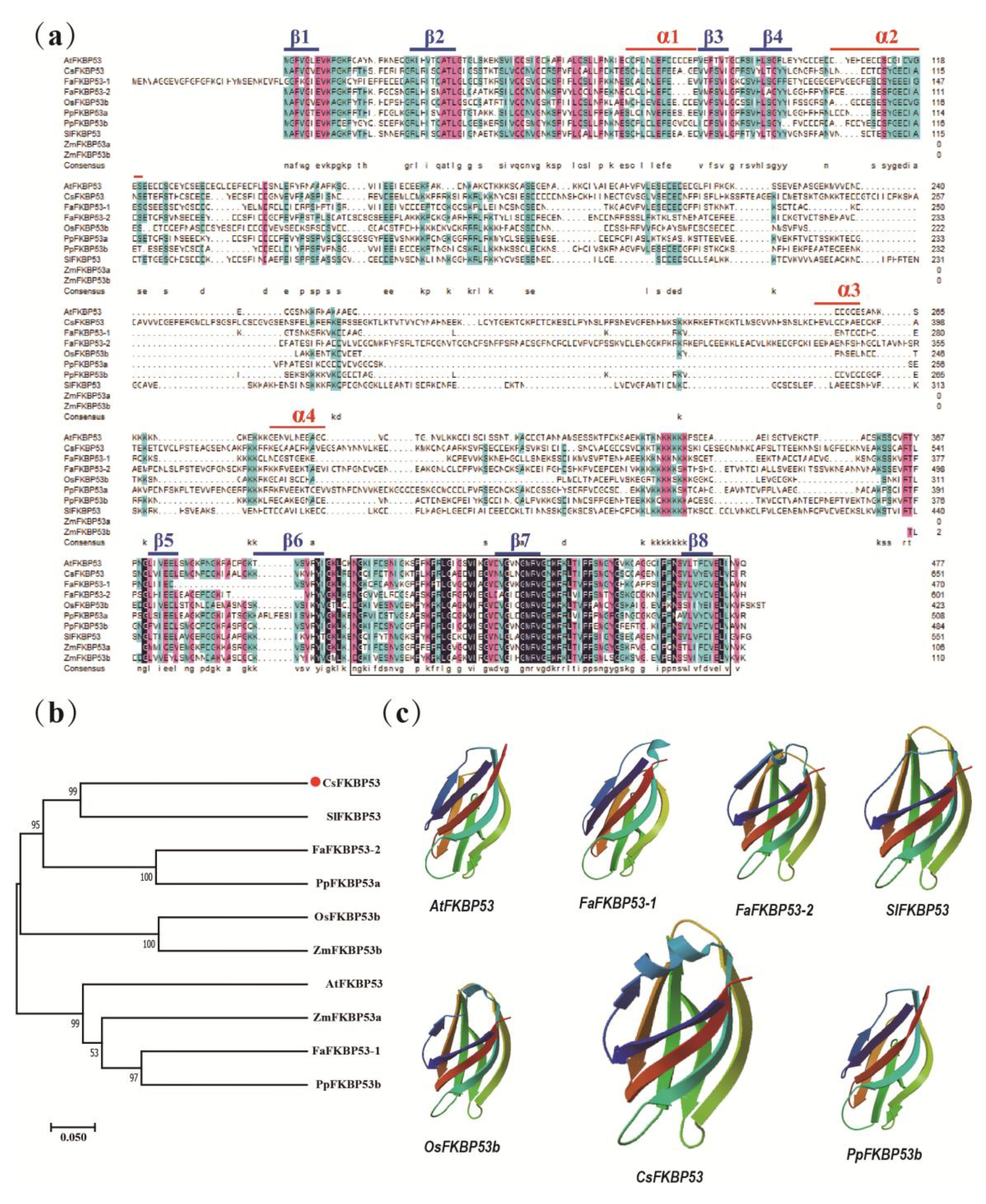

2.5. Sequence and Phylogenetic Analyses and Sub-Cellular Localization of CsFKBP53

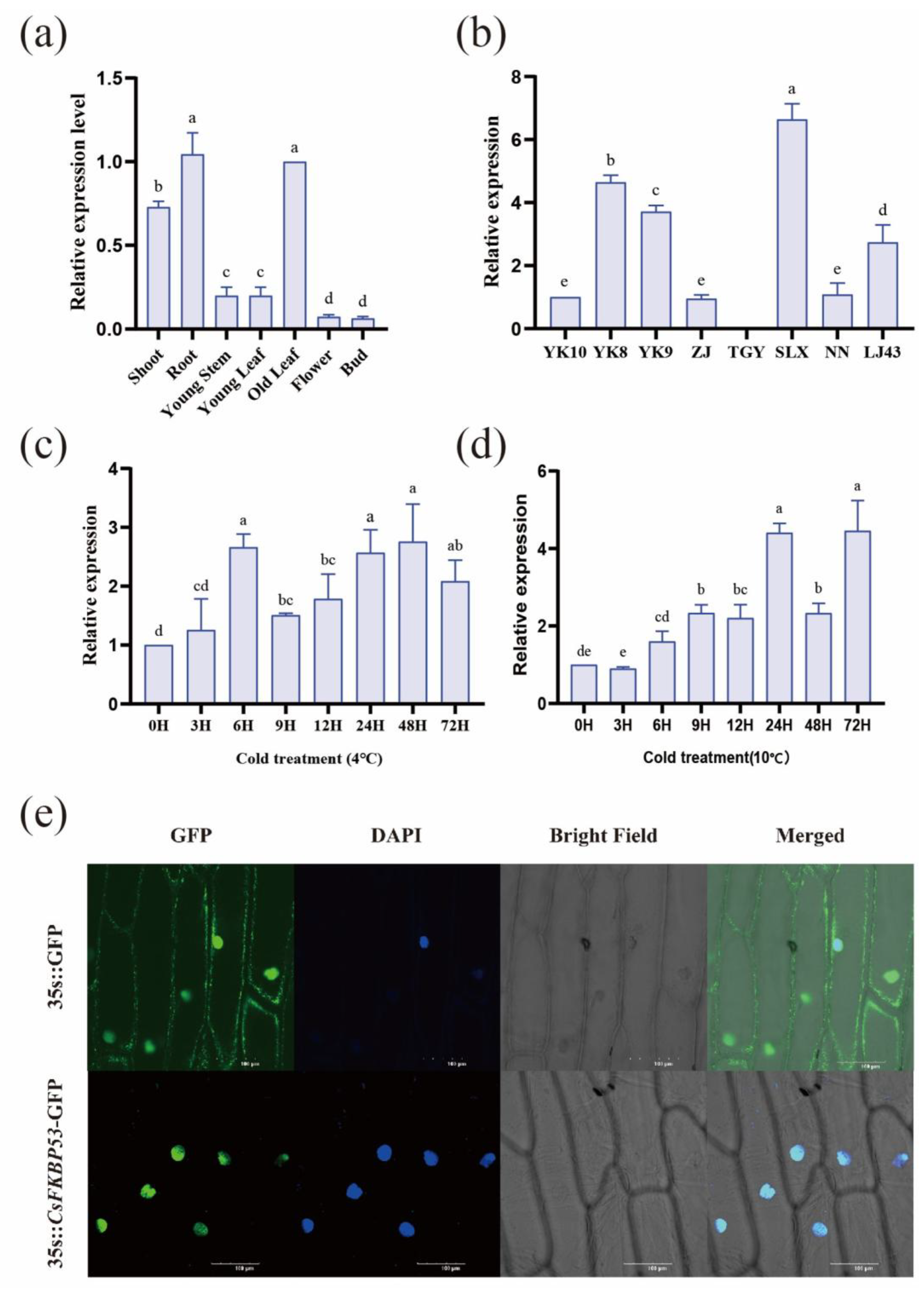

2.6. The Expression Pattern Analysis and Subcellular Localization of CsFKBP53

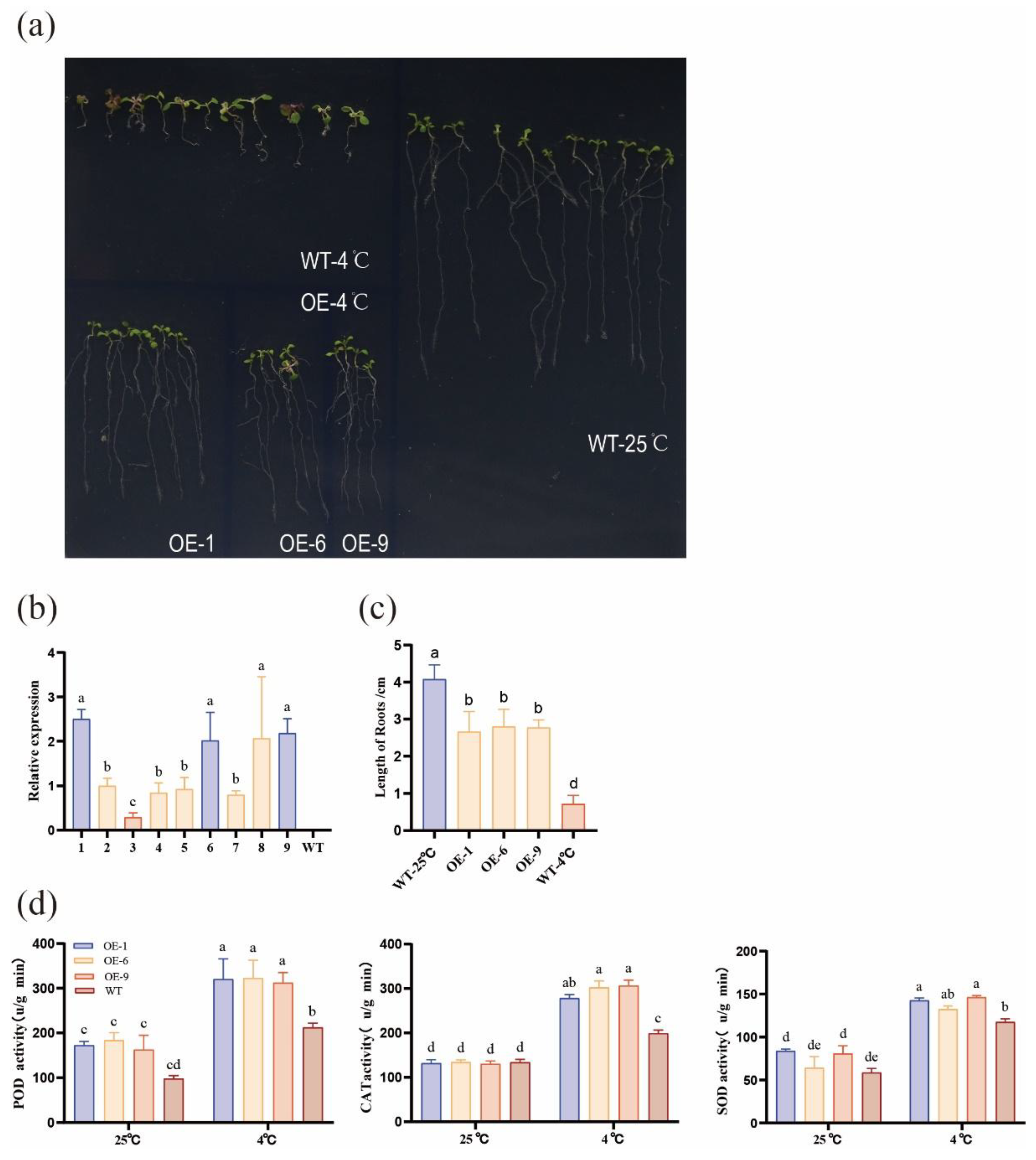

2.7. Transgenic CsFKBP53 Improves Low-Temperature Resistance of Arabidopsis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Stress Treatments

4.2. Identification and Physical Properties of FKBP Genes in Tea

4.3. Evolution of CsFKBP Protein in Tea

4.4. Gene Structure and Motif Analysis

4.5. Total RNA Extraction and Expression Analysis

4.6. Gene Cloning and Vector Construction

4.7. Protein Subcellular Localization Studies

4.8. Overexpress and Functional Analysis of CsFKBP53 Under Low Temperature Treatment

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harding, M.W.; Galat, A.; Uehling, D.E.; Schreiber, S.L. , A receptor for the immuno-suppressant FK506 is a cis–trans peptidyl-prolyl isomerase. Nature 1989, 341, 758–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siekierka, J.J.; Hung, S.H.Y.; Poe, M.; Lin, C.S.; Sigal, N.H. , A cytosolic binding protein for the immunosuppressant FK506 has peptidyl-prolyl isomerase activity but is distinct from cyclophilin. Nature 1989, 341, 755–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, G.; Bang, H.; Mech, C. , [Determination of enzymatic catalysis for the cis-trans-isomerization of peptide binding in proline-containing peptides]. Biomed Biochim Acta 1984, 43, 1101–11. [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan, D.; Gopalan, G.; Kumar, A.; Garcia, V.J.; Luan, S.; Swaminathan, K. , Plant immunophilins: a review of their structure-function relationship. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 2015, 1850, 2145–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiri, D.; Tazat, K.; Cohen-Peer, R.; Farchi-Pisanty, O.; Aviezer-Hagai, K.; Avni, A.; Breiman, A. , Involvement of Arabidopsis ROF2 (FKBP65) in thermotolerance. Plant Mol Biol 2010, 72, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aviezer-Hagai, K.; Skovorodnikova, J.; Galigniana, M.; Farchi-Pisanty, O.; Maayan, E.; Bocovza, S.; Efrat, Y.; von Koskull-Döring, P.; Ohad, N.; Breiman, A. , Arabidopsis immunophilins ROF1 (AtFKBP62) and ROF2 (AtFKBP65) exhibit tissue specificity, are heat-stress induced, and bind HSP90. Plant Mol Biol 2007, 63, 237–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, W.; Wunderlich, M.; Schoffl, F. , Identification of novel heat shock factor-dependent genes and biochemical pathways in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 2005, 41, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.C.; Kim, D.W.; You, Y.N.; Seok, M.S.; Park, J.M.; Hwang, H.; Kim, B.G.; Luan, S.; Park, H.S.; Cho, H.S. , Classification of rice (Oryza sativa L. Japonica nipponbare) immunophilins (FKBPs, CYPs) and expression patterns under water stress. BMC Plant Biol 2010, 10, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, S.; Kudla, J.; Gruissem, W.; Schreiber, S.L. , Molecular characterization of a FKBP-type immunophilin from higher plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996, 93, 6964–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Mu, C.; Zhang, F.; Wang, L.; Meng, Z. , Genome-wide analysis and environmental response profiling of the FK506-binding protein gene family in maize (Zea mays L.). Gene 2012, 498, 212–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiri, D.; Breiman, A. , Arabidopsis ROF1 (FKBP62) modulates thermotolerance by interacting with HSP90.1 and affecting the accumulation of HsfA2-regulated sHSPs. Plant J 2009, 59, 387–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edlich-Muth, C.; Artero, J.B.; Callow, P.; Przewloka, M.R.; Watson, A.A.; Zhang, W.; Glover, D.M.; Debski, J.; Dadlez, M.; Round, A.R.; Forsyth, V.T.; Laue, E.D. , The pentameric nucleoplasmin fold is present in Drosophila FKBP39 and a large number of chromatin-related proteins. J Mol Biol 2015, 427, 1949–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, M.; Ahmad, F.; Habib, S.; Gao, Y.; Li, Z. , Genome-wide identification of FK506-binding domain protein gene family, its characterization, and expression analysis in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Gene 2018, 678, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, P.; Gray, J.; Horton, P.; Luan, S. , Plant immunophilins: functional versatility beyond protein maturation. New Phytol 2005, 166, 753–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, G.; Rutkowska, A.; Wegrzyn, R.D.; Patzelt, H.; Kurz, T.A.; Merz, F.; Rauch, T.; Vorderwülbecke, S.; Deuerling, E.; Bukau, B. , Functional dissection of Escherichia coli trigger factor: unraveling the function of individual domains. J Bacteriol 2004, 186, 3777–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisler, M.; Bailly, A. , Tête-à-tête: the function of FKBPs in plant development. Trends Plant Sci 2007, 12, 465–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driessen, A.J.; Manting, E.H.; van der Does, C. , The structural basis of protein targeting and translocation in bacteria. Nat Struct Biol 2001, 8, 492–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, E.H.; Tong, W.; Wu, Q.; Wei, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Wei, C.L.; Wan, X.C. , Tea plant genomics: achievements, challenges and perspectives. Hortic Res 2020, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Li, X.; Ahammed, G.J. In Stress Physiology of Tea in the Face of Climate Change, Springer Singapore, 2018; 2018.

- Wang, M.; Yang, J.; Li, J.; Zhou, X.; Xiao, Y.; Liao, Y.; Tang, J.; Dong, F.; Zeng, L. , Effects of temperature and light on quality-related metabolites in tea [Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze] leaves. Food Res Int 2022, 161, 111882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Li, N.; Di, T.; Ding, C.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Hao, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, L. , The interaction of CsWRKY4 and CsOCP3 with CsICE1 regulates CsCBF1/3 and mediates stress response in tea plant (Camellia sinensis). Environmental and Experimental Botany 2022, 199, 104892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.-Y.; Burgos, A.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Q.; Tang, D.; Ruan, J. , Lipidomics analysis unravels the effect of nitrogen fertilization on lipid metabolism in tea plant (Camellia sinensis L.). BMC Plant Biology 2017, 17, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, Y.; Wei, C.; Yang, H.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Q.; Deng, W.; Wei, S.; Zhang, J.; Fang, C.; Ho, C.; Wan, X. , Transcriptomic and phytochemical analysis of the biosynthesis of characteristic constituents in tea (Camellia sinensis) compared with oil tea (Camellia oleifera). BMC Plant Biol 2015, 15, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, E.H.; Zhang, H.B.; Sheng, J.; Li, K.; Zhang, Q.J.; Kim, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, T.; Li, W.; Huang, H.; Tong, Y.; Nan, H.; Shi, C.; Shi, C.; Jiang, J.J.; Mao, S.Y.; Jiao, J.Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.J.; Zhang, L.P.; Liu, Y.L.; Liu, B.Y.; Yu, Y.; Shao, S.F.; Ni, D.J.; Eichler, E.E.; Gao, L.Z. , The Tea Tree Genome Provides Insights into Tea Flavor and Independent Evolution of Caffeine Biosynthesis. Mol Plant 2017, 10, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Mao, K.; Duan, D.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Huang, D.; Li, C.; Liu, C.; Gong, X.; Ma, F. , Genome-wide analyses of genes encoding FK506-binding proteins reveal their involvement in abiotic stress responses in apple. BMC Genomics 2018, 19, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollan, P.J.; Bhave, M. , Genome-wide analysis of genes encoding FK506-binding proteins in rice. Plant Mol Biol 2010, 72, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Li, L.; Luan, S. , Immunophilins and parvulins. Superfamily of peptidyl prolyl isomerases in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 2004, 134, 1248–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldape, R.A.; Futer, O.; DeCenzo, M.T.; Jarrett, B.P.; Murcko, M.A.; Livingston, D.J. , Charged surface residues of FKBP12 participate in formation of the FKBP12-FK506-calcineurin complex. J Biol Chem 1992, 267, 16029–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrar, Y.; Bellini, C.; Faure, J.D. , FKBPs: at the crossroads of folding and transduction. Trends Plant Sci 2001, 6, 426–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalaikumar, V.P.; Gorka, M.; Schulz, K.; Masclaux-Daubresse, C.; Sampathkumar, A.; Skirycz, A.; Vierstra, R.D.; Balazadeh, S. , Selective autophagy regulates heat stress memory in Arabidopsis by NBR1-mediated targeting of HSP90.1 and ROF1. Autophagy 2021, 17, 2184–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.Y.; Auyeung, W.K.; Li, K.P.; Lam, H.M. , A Rice Immunophilin Homolog, OsFKBP12, Is a Negative Regulator of Both Biotic and Abiotic Stress Responses. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollan, P.J.; Bhave, M.; Aro, E.M. , The FKBP families of higher plants: Exploring the structures and functions of protein interaction specialists. FEBS Lett 2012, 586, 3539–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigam, N.; Singh, A.; Sahi, C.; Chandramouli, A.; Grover, A. , SUMO-conjugating enzyme (Sce) and FK506-binding protein (FKBP) encoding rice (Oryza sativa L.) genes: genome-wide analysis, expression studies and evidence for their involvement in abiotic stress response. Mol Genet Genomics 2008, 279, 371–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, X.; Liu, D.; Zhao, M.; Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Mu, Q.; Zhu, X.; Li, P.; Fang, J. , Genome-wide identification and analysis of FK506-binding protein family gene family in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa). Gene 2014, 534, 390–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shangguan, L.; Kayesh, E.; Leng, X.; Sun, X.; Korir, N.K.; Mu, Q.; Fang, J. , Whole genome identification and analysis of FK506-binding protein family genes in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). Mol Biol Rep 2013, 40, 4015–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, J.; Liu, D.; Wen, X.; Li, Y.; Tao, R.; Peng, Y.; Fang, J.; Wang, C. , Genome-wide identification and analysis of FK506-binding protein gene family in peach (Prunus persica). Gene 2014, 536, 416–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurek, I.; Aviezer, K.; Erel, N.; Herman, E.; Breiman, A. , The wheat peptidyl prolyl cis-trans-isomerase FKBP77 is heat induced and developmentally regulated. Plant Physiol 1999, 119, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, W.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhu, T.; Yang, M.; Deng, S.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Chen, S. , Frost risk assessment based on the frost-induced injury rate of tea buds: A case study of the Yuezhou Longjing tea production area, China. European Journal of Agronomy 2023, 147, 126839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Wang, B.; Wang, L.; Zeng, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X. , Comprehensive transcriptome analysis reveals common and specific genes and pathways involved in cold acclimation and cold stress in tea plant leaves. Scientia Horticulturae 2018, 240, 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Mallano, A.I.; Li, F.; Li, P.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Ahmad, N.; Tong, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xia, E. , Characterization of CsWRKY29 and CsWRKY37 transcription factors and their functional roles in cold tolerance of tea plant. Beverage Plant Research 2022, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-L.; Cui, X.; Wang, Y.-X.; Liu, Z.-W.; Zhuang, J. , Members of R2R3-type MYB transcription factors from subgroups 20 and 22 are involved in abiotic stress response in tea plants. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment 2018, 32, 1141–1153. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Sun, B.; He, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, H.; Wang, B. , Current Understanding of bHLH Transcription Factors in Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranawake, A.L.; Manangkil, O.E.; Yoshida, S.; Ishii, T.; Mori, N.; Nakamura, C. , Mapping QTLs for cold tolerance at germination and the early seedling stage in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip 2014, 28, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Ou, W.; Lu, S.; Zhong, Q. , Differential responses of antioxidative system to chilling and drought in four rice cultivars differing in sensitivity. Plant Physiol Biochem 2006, 44, 828–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, E.H.; Li, F.D.; Tong, W.; Li, P.H.; Wu, Q.; Zhao, H.J.; Ge, R.H.; Li, R.P.; Li, Y.Y.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Wei, C.L.; Wan, X.C. , Tea Plant Information Archive: a comprehensive genomics and bioinformatics platform for tea plant. Plant Biotechnol J 2019, 17, 1938–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, E.; Tong, W.; Hou, Y.; An, Y.; Chen, L.; Wu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Yu, J.; Li, F.; Li, R.; Li, P.; Zhao, H.; Ge, R.; Huang, J.; Mallano, A.I.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Deng, W.; Song, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Wei, S.; Zhang, Z.; Xia, T.; Wei, C.; Wan, X. , The Reference Genome of Tea Plant and Resequencing of 81 Diverse Accessions Provide Insights into Its Genome Evolution and Adaptation. Mol Plant 2020, 13, 1013–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, T.J.; Eddy, S.R. , nhmmer: DNA homology search with profile HMMs. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 2487–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. , 20 years of the SMART protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, D493–d496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. , MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol Biol Evol 2016, 33, 1870–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Jin, J.; Guo, A.Y.; Zhang, H.; Luo, J.; Gao, G. , GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1296–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. , TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. , Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Mallano, A.I.; Li, F.; Li, P.; Wu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Ahmad, N.; Tong, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xia, E. , Characterization of <i>CsWRKY29</i> and <i>CsWRKY37</i> transcription factors and their functional roles in cold tolerance of tea plant. Beverage Plant Research 2022, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

| Gene Name | Gene ID | FKBP-C domain number | CDS Length/bp | Amino acid/aa | Molecular Weight/kD | Theoretical pl | Subcellular Localizations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CsFKBP11 | CsasTrans141447 | 1 | 306 | 101 | 11.02 | 8.87 | Nuclear | |

| CsFKBP12 | CsasTrans179814 | 1 | 692 | 112 | 11.93 | 7.75 | ChloroPlast | |

| CsFKBP12-1 | CsasTrans156117 | 1 | 332 | 110 | 12.26 | 10.13 | Nuclear | |

| CsFKBP13 | CsasTrans097150 | 1 | 1075 | 244 | 25.74 | 8.7 | Peroxisome | |

| CsFKBP15-1 | CsasTrans095919 | 1 | 959 | 153 | 16.34 | 7.68 | Vacuole | |

| CsFKBP16-2 | CsasTrans065843 | 1 | 1113 | 238 | 25.46 | 9.44 | Cytoplasm | |

| CsFKBP16-3 | CsasTrans159019 | 1 | 1132 | 273 | 29.67 | 8.47 | ChloroPlast | |

| CsFKBP16-4 | CsasTrans093053 | 1 | 1200 | 234 | 24.74 | 9.68 | ChloroPlast | |

| CsFKBP17-2 | CsasTrans181995 | 1 | 1220 | 259 | 27.69 | 6.18 | ChloroPlast | |

| CsFKBP18 | CsasTrans153703 | 1 | 1036 | 237 | 25.4 | 9.58 | ChloroPlast | |

| CsFKBP19 | CsasTrans009318 | 1 | 1424 | 295 | 32.24 | 6.79 | Extracell | |

| CsFKBP20 | CsasTrans077854 | 1 | 2327 | 188 | 20.5 | 7.76 | Nuclear | |

| CsFKBP27 | CsasTrans003218 | 1 | 1236 | 238 | 27.09 | 8.64 | ChloroPlast | |

| CsFKBP33 | CsasTrans135390 | 1 | 900 | 300 | 33.82 | 4.52 | Nuclear | |

| CsFKBP42 | CsasTrans194578 | 1 | 1493 | 364 | 41.76 | 5.66 | Nuclear | |

| CsFKBP47 | CsasTrans171260 | 3 | 1920 | 427 | 46.72 | 4.76 | Cytoplasm | |

| CsFKBP53 | CsasTrans084696 | 1 | 2329 | 651 | 72.43 | 5.61 | Nuclear | |

| CsFKBP53a | CsasTrans162628 | 1 | 2429 | 100 | 10.81 | 10.44 | ChloroPlast | |

| CsFKBP62 | CsasTrans005298 | 2 | 2600 | 571 | 63.81 | 5.17 | Peroxisome | |

| CsFKBP72 | CsasTrans105671 | 3 | 2428 | 619 | 69.99 | 5.35 | Nuclear | |

| CsTIG | CsasTrans154119 | 0 | 1151 | 383 | 43.06 | 5.09 | Nuclear |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).