Submitted:

08 October 2025

Posted:

09 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Results and Discussion

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Competing Interests

References

- Oliver Summerfield-Ryan; Susan Park. The power of wind: The global wind energy industry's successes and failures. Ecological Economics. 2023, 210, 107841. [CrossRef]

- Xhao, X; Copenhaver, K; Wang, L; Korey, M; Gardner, D.J; Li, K; Lamm, M.E; Kishore, V; Bhagia, S; Tajvidi, M; Tekinalp, H; Oyedeji, O; Wasti, S; Webb, E; Ragauskas, A.J; Zhu, H; Peter, W.H; Ozcan, S. Recycling of natural fiber composites: Challenges and opportunities. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022,177, 105962. [CrossRef]

- Sachin Ghalme; Mohammad Hayat; Mahesh Harne.A comprehensive review of natural fibers: Bio-based constituents for advancing sustainable materials technology. J.Ren.Mat. 2025,13(2),273-295. [CrossRef]

- Marion, P; Andréas, R; Marie, H.M. Study of wheat gluten plasticization with fatty ac-ids. Polym.2003, 44,115-122. [CrossRef]

- Holmes John W; Brøndsted, Povl; Sørensen Bent, F; Zehui, Jiang; Zhengjun, Sun; Chen, Xuhe. Development of a bamboo-based composite as a sustainable green material for wind turbine blades. Wind Eng. 2009, 33, 197-210. [CrossRef]

- Jeyapragash R, Srinivasan V, Sathiyamurthy SJMTP. Mechanical properties of natural fiber/particulate reinforced epoxy composites–a review of the literature. Mater Today Proc. 2020; 22: 1223-1227. [CrossRef]

- Saravia, M.C; Saravia, L.J; Cortínez, V.H. A one-dimensional discrete approach for the determination of the cross-sectional properties of composite rotor blades. Renew Ener.2015, 80,713-723. [CrossRef]

- Fedon, N; Weaver, P.M; Pirrera, A; Macquart, T. A method using beam search to design the lay-ups of composite laminates with many plies. Composites Part C, 2021, 4,100072. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L; Ramachandra, M. Advanced materials for wind turbine blade-A Review, Mater. Today. Proc. 2018, 5 (1),2635–2640. [CrossRef]

- Gherissi, A. A study of wind turbine blade structure based on cellulose fibers composite material. Proc. Eng. Technol.2018,38, 80–85.

- Ganesh, R.K; Rajashekar, P; Narayan, N. Natural fiber reinforced polymer composite materials for wind turbine blade applications. Int. J. Sci. Develop. Res. 2016, 1(9), 28-37.

- Tarfaoui, M; Shah, O; Nachtane, M. Design and optimization of composite offshore wind turbine blades. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2019, 141 (5), 51204. [CrossRef]

- Lahcen Amzil; Saloua Fertahi; Tarik Raffak; Taoufiq Mouhib.Towards sustainable blade design: A critical review of natural fiber-reinforced hybrid composites and structural analysis tutorials. Next Mat. 2025,8,100688.

- Paulsen, U.S; Madsen, H.A; Hattel, J.H; Baran, I; Nielsen,P.H. Design optimization of a 5 MW floating offshore vertical-axis wind turbine. Energy Proc.2013, 35, 22–32. [CrossRef]

- Su, H; Dou, B; Qu, T; Zeng, P; Lei, L. Experimental investigation of a novel vertical axis wind turbine with pitching and self-starting function. Energy Convers Manag. 2020,217,113012. [CrossRef]

- Rajak, D.K; Pagar, D.D; Menezes, P.L; Linul, E. Fiber-reinforced polymer composites: manufacturing, properties, and applications, Polymers.2019, 11 (10),1667. [CrossRef]

- Das, S.C; Sheikh, A.E.K; Sayeed, M. A; Suruzzaman Paul; Dhar, D; Grammatikos, S.A. On the use of wood charcoal filler to improve the properties of natural fiber reinforced polymer composites. Mater. Today. 2020, 44:926–929. [CrossRef]

- Dinesh, S; Kumaran, S. Mohanamurugan, R; Vijay, D. L; Singaravelu, A; Vinod, M; Sanjay, R; Siengchin, P.S; Bhat, K.S. Influence of wood dust fillers on the mechanical, thermal, water absorption and biodegradation characteristics of jute fiber epoxy composites. J. Poly. Res. 2020, 27,1–13. [CrossRef]

- Mishnaevsky, L; Branner, K; Petersen, H.N; Beauson, J; McGugan, M; Sørensen, B.F. Materials for wind turbine blades: An overview. Materials.2017,10,1285. [CrossRef]

- Sever, K; Sarikanat, M; Seki, Y; Erkan, G; Erdogan, U.H; Erden, S. Surface treatments of jute fabric: The influence of surface characteristics on jute fabrics and mechanical properties of jute/polyestercomposites.Ind.Crops.Prod.2012,35,22–30. [CrossRef]

- Saiteja, J; Jayakumar, V; Bharathiraja, G. Evaluation of mechanical properties of jute fiber/carbon nano tube filler reinforced hybrid polymer composite. Mater. Today. Proc. 2019, 22(3),756-758. [CrossRef]

- Rana, A. K; Mandal, A; Mitra, B. C; Jacobson, R; Rowell, R; Banerjee, A. N. Short jute fiber-reinforced polypropylene composites: Effect of compatibilizer. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1998, 69, 329−338. [CrossRef]

- Le, T. M; Pickering, K. L. The potential of harakeke fibre as reinforcement in polymer matrix composites including modelling of long harakeke fibre composite strength. Composites Part A: Appl. Sci. Manufac.2015,76, 44-53. [CrossRef]

- Shah, D. U; Porter, D; Vollrath, F. (2014). Can silk become an effective reinforcing fibre? A property comparison with flax and glass reinforced composites. Composites. Sci. Tech.101,173-183.

- Charlet, K; Baley, C; Morvan, C; Jernot, J. P; Gomina, M; Bréard, J. Characteristics of Hermès flax fibres as a function of their location in the stem and properties of the derived unidirectional composites. Composites Part A: Appl.Sci. Manufac. 2007, 38(8), 1912-1921. [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy, T; Sathiskumar, R; Sanjay, M.R; Senthamaraikannan, P; Saravanakumar, S.S; Parameswaranpillai, J; Siengchin, S. Effect of graphene powder on banyan aerial root fibers reinforced epoxy composites. J. Nat.Fibers.2021, 18 (7),1029–1036. [CrossRef]

- Mohd Hafiz Zamri; Md Akil Hazizan; Bakar Abu Azhar; Ahmad Arifin Zainal; Cheng Leong. Effect of water absorption on pultruded jute/glass fiber-reinforced unsaturated polyester hybrid composites. J.Compo.Mater. 2011, 46, 51-61. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V; Biswas, S. Physical and mechanical properties of bi-directional jute fiber epoxy composites. Proc. Eng. 2013, 51:561–566. [CrossRef]

- Teh, P.L; Jaafar, M; Akil, H.M; Seetharamu, K.N; Wagiman, A.N.R; Beh K.S. Thermal and mechanical properties of particulate fillers filled epoxy composites for electronic packaging application. Poly. Adv.Technol.2008,19,308–315. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P. V; Prasad, P.R; Krishnudu, D.M; Hussain, P. Influence of fillers on mechanical properties of Prosopis juliflora fiber reinforced hybrid composites. Mater. Today: Proc. 2019, 7, 618. [CrossRef]

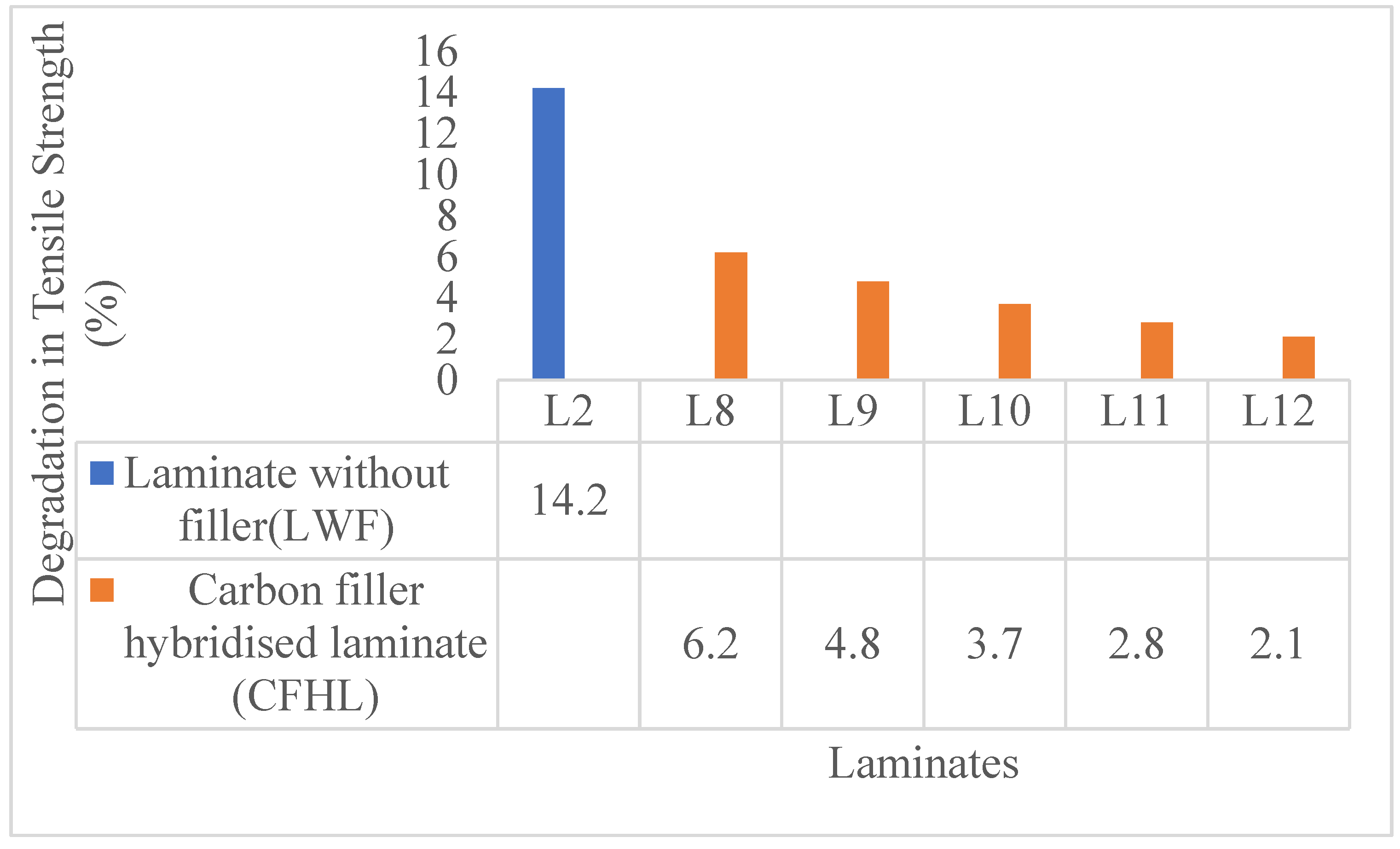

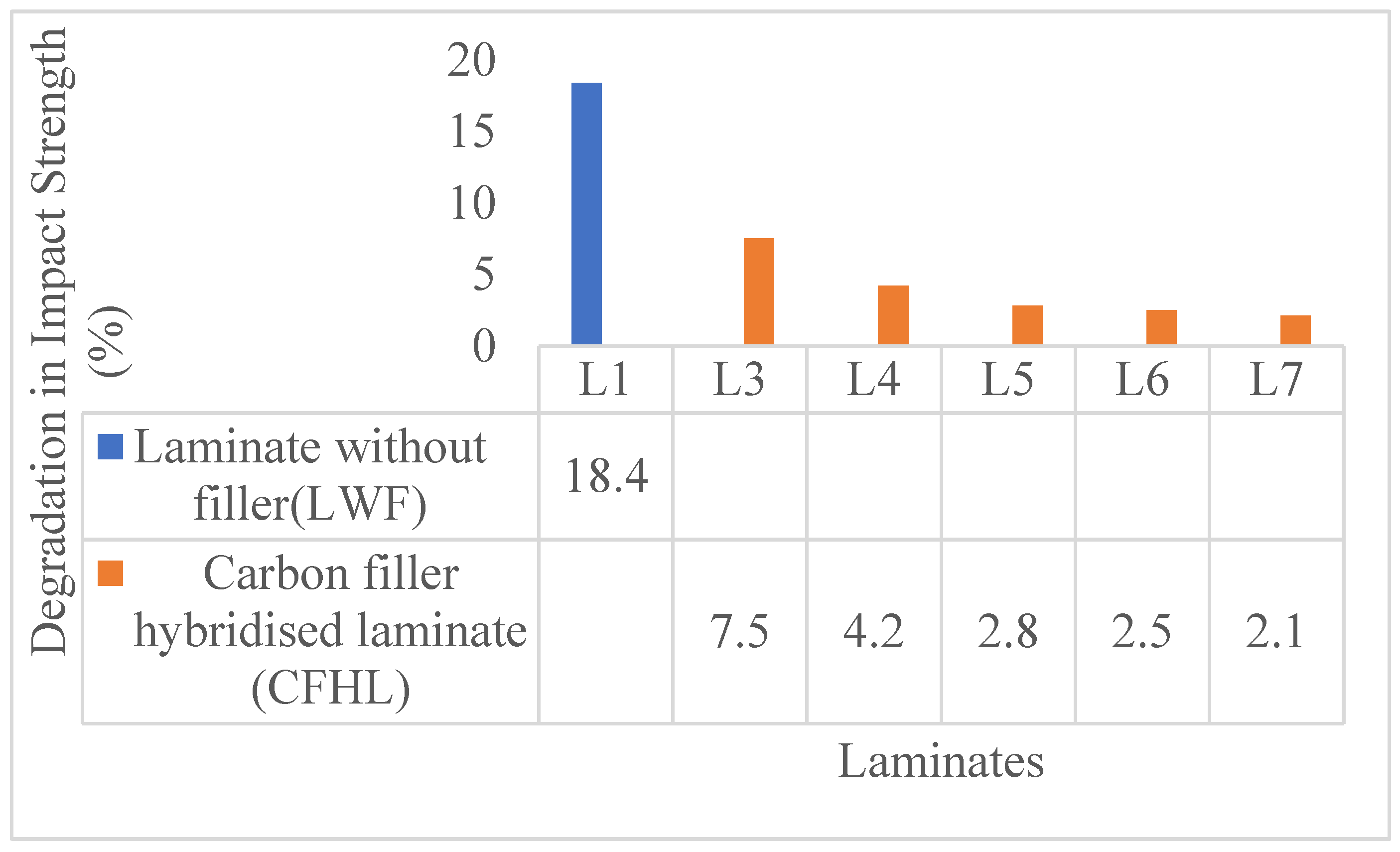

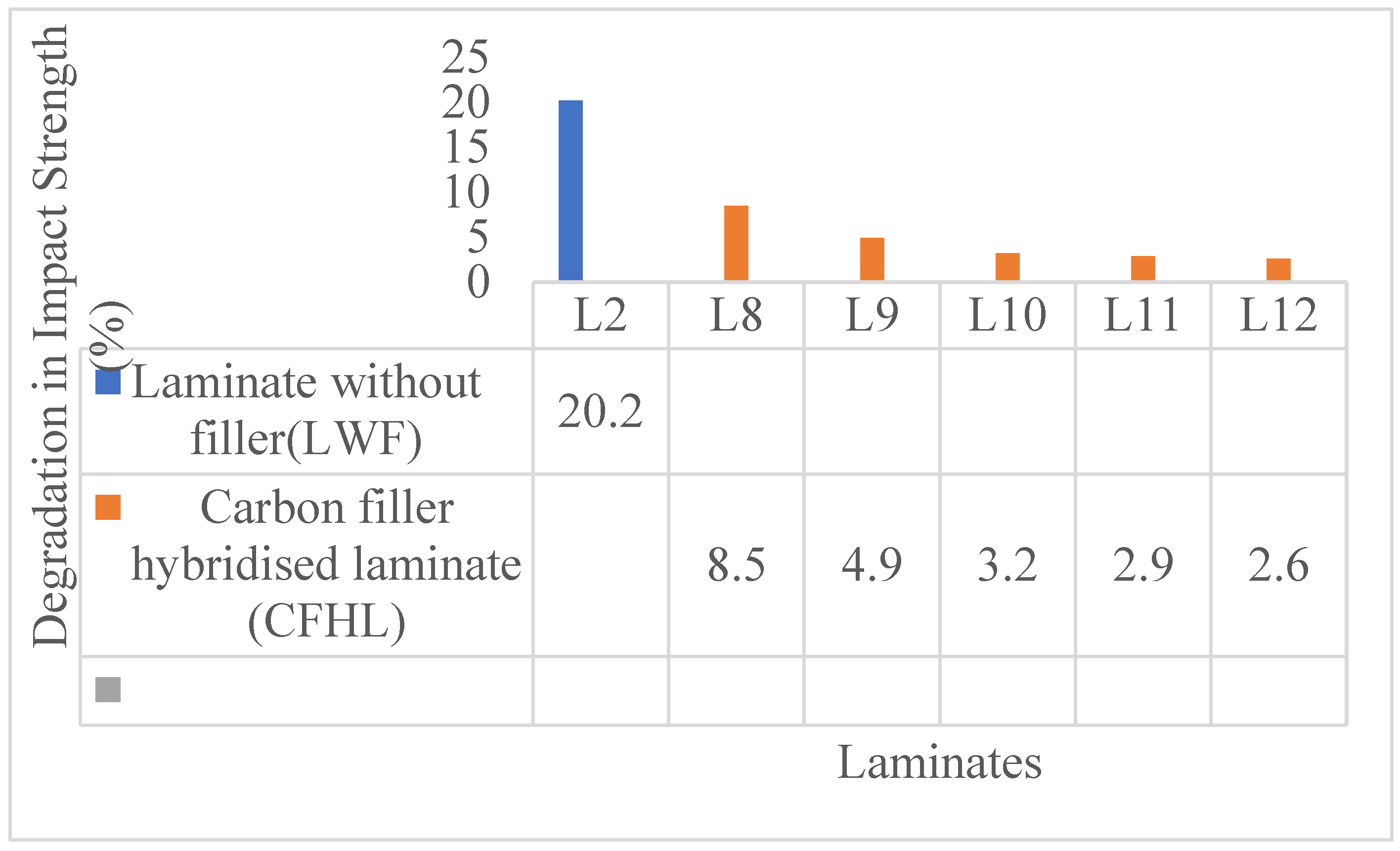

- Tesfay, A. G; Kahsay, M.B; Senthil Kumar, P.S. Improvement of the degradation of tensile and impact strength of water-aged sisal fiber-reinforced polyester composites: A comparative study on the effects of hybridizations, hybrid layering sequences, and chemical treatments. J. Natu. Fibers. 2022,19 (15), 11597–11609. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B; Hazra, B; Sarkar, A; Bandyopadhyay, N.R; Mitra, B.C; Sinha, A. Influence of ZrO2 incorporation on sisal fiber reinforced unsaturated polyester composites. Poly.Compos.2019, 40,2790–801. [CrossRef]

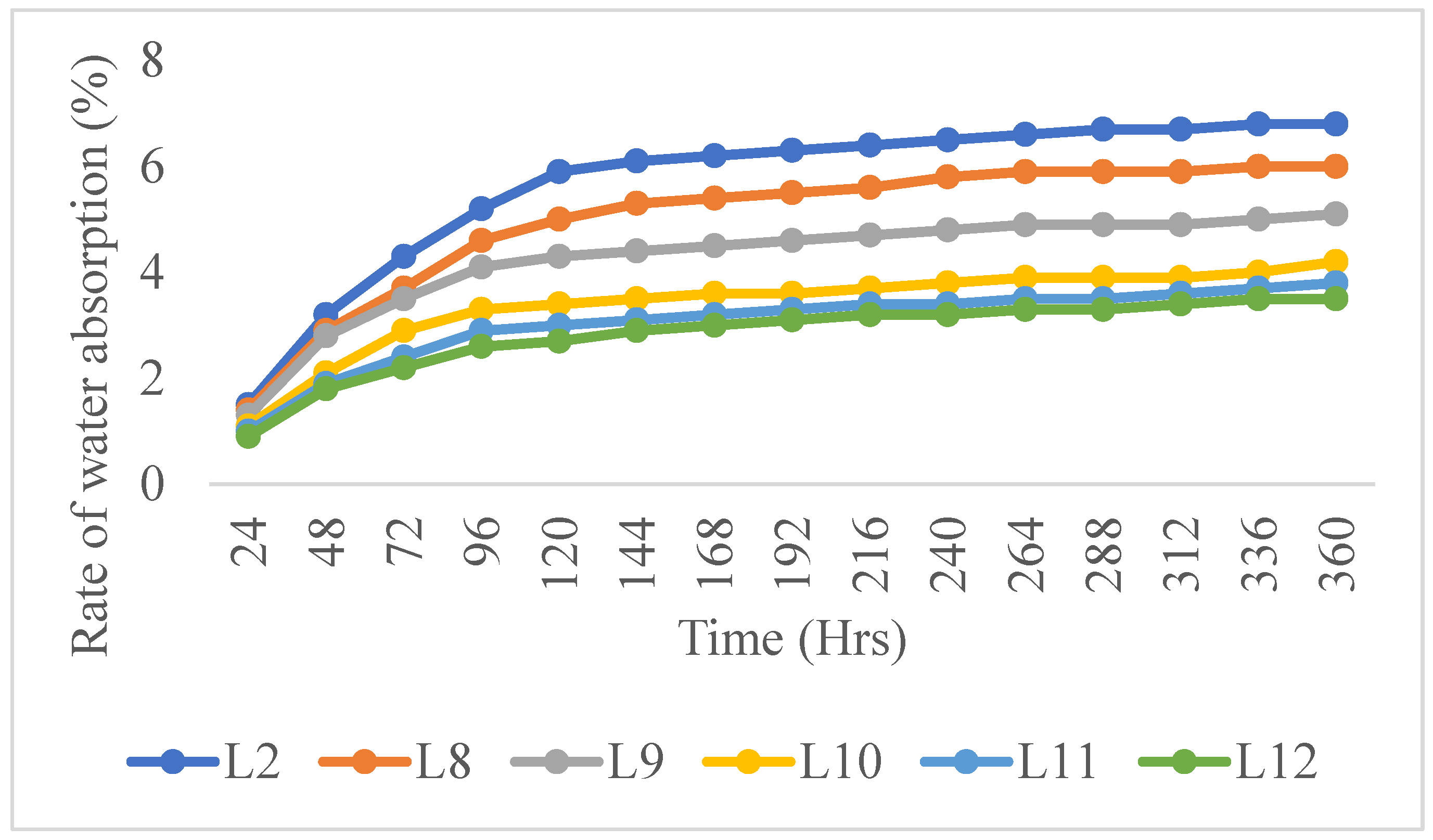

| Laminate | Classification | Composition |

| L1 | Composite 30/70 | 30 wt% jute fiber + 70 wt% Epoxy |

| L2 | Composite 40/60 | 40 wt% jute fiber +60 wt% Epoxy |

| L3 | C2, Composite 30/70 | Carbon filler (2% of the 30/70 composite) + 30/70 composite |

| L4 | C4, Composite 30/70 | Carbon filler (4% of the 30/70 composite) + 30/70 composite |

| L5 | C6, Composite 30/70 | Carbon filler (6% of the 30/70 composite) + 30/70 composite |

| L6 | C8, Composite 30/ 70 | Carbon filler (8% of the 30/70 composite) + 30/70 composite |

| L7 | C10, Composite 30/ 70 | Carbon filler (10% of the 30/70 composite) + 30/70 composite |

| L8 | C2, Composite 40/60 | Carbon filler (2wt% of the 40/60 composite) + 40/60 composite |

| L9 | C4, Composite 40/60 | Carbon filler (4wt% of the 40/60 composite) + 40/60 composite |

| L10 | C6, Composite 40/60 | Carbon filler (6wt% of the 40/60 composite) + 40/60 composite |

| L11 | C8, Composite 40/60 | Carbon filler (8wt% of the 40/60 composite) + 40/60 composite |

| L12 | C10, Composite 40/60 | Carbon filler (10wt% of the 40/60 composite) + 40/60 composite |

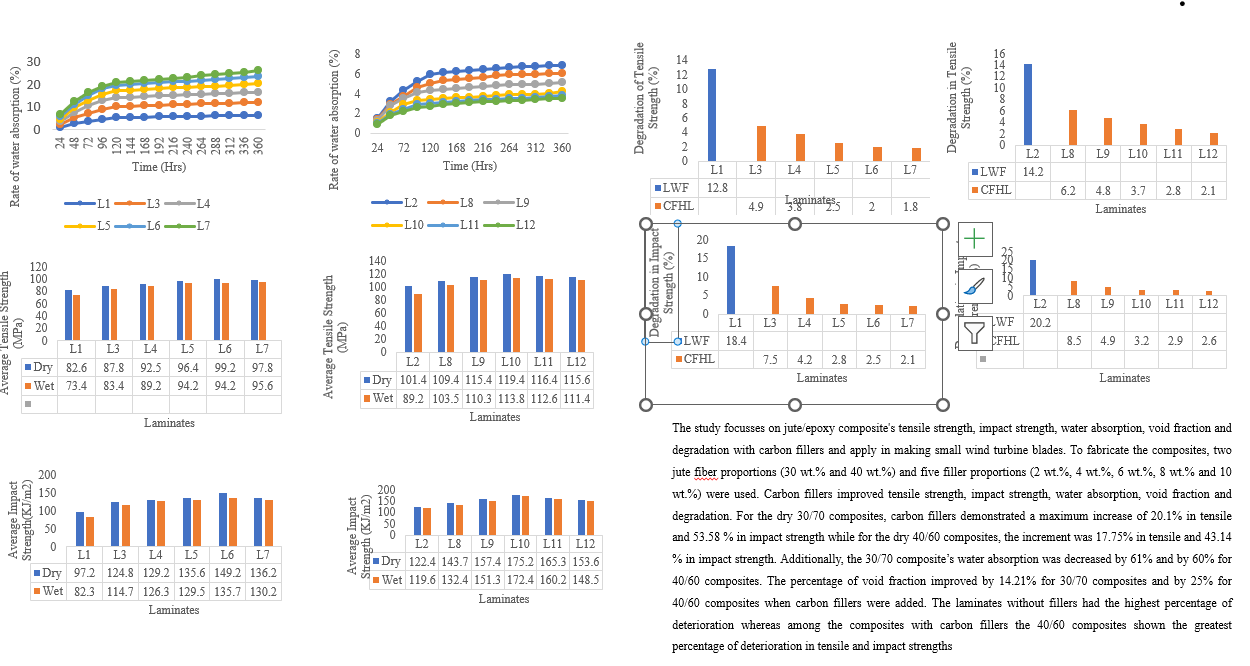

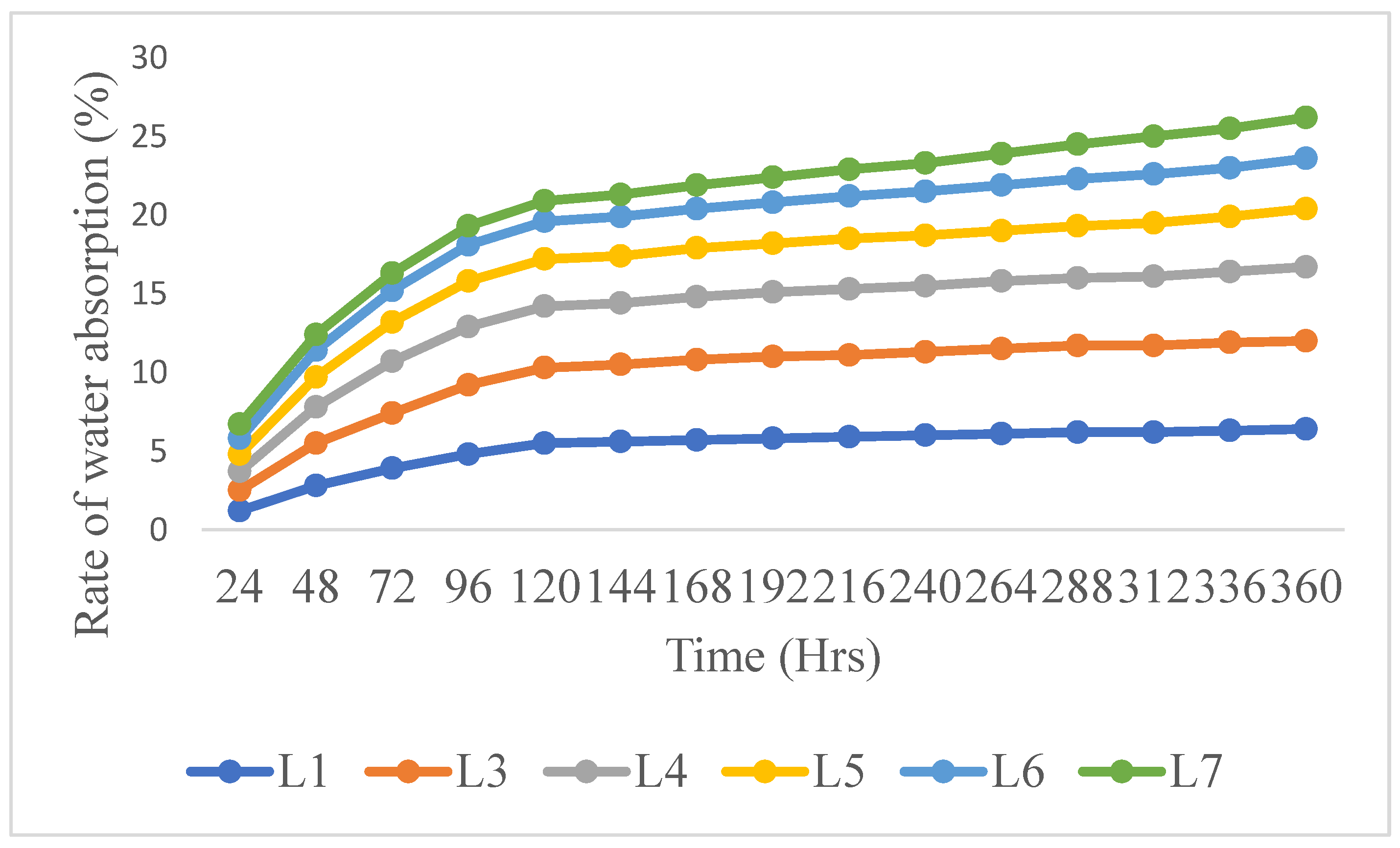

| Laminate | % of water absorption (Average % ± SD) |

| L1 | 6.4 ± 0.16 |

| L2 | 6.8 ± 0.23 |

| L3 | 4.9 ± 0.12 |

| L4 | 4.0 ± 0.16 |

| L5 | 3.3 ± 0.18 |

| L6 | 2.8 ± 0.14 |

| L7 | 2.5± 0.12 |

| L8 | 5.0 ± 0.16 |

| L9 | 4.1 ± 0.12 |

| L10 | 3.8 ± 0.14 |

| L11 | 3.1 ± 0.13 |

| L12 | 2.7± 0.14 |

| Laminate | Composition |

Theoretical Density

(ρt g/cm3) |

Experimental Density

(ρ exp g/cm3) |

Void Fraction (%) |

| L1 | 30 wt% jute fiber + 70 wt% Epoxy | 1.164 ± 0.016 | 1.107±0.021 | 4.91±0.005 |

| L2 | 40 wt% jute fiber +60 wt% Epoxy | 1.153 ± 0.014 | 1.104±0.016 | 4.24±0.002 |

| L3 | 2% carbon filler of the composite 30/70 + composite 30/70 | 1.172 ± 0.025 | 1.110±0.032 | 5.29±0.007 |

| L4 | 4% carbon filler of the composite 30/70 + composite 30/70 | 1.175 ± 0.021 | 1.111±0.025 | 5.44±0.004 |

| L5 | 6% carbon filler of the composite 30/70 + composite 30/70 | 1.181±0.018 | 1.115±0.026 | 5.59±0.008 |

| L6 | 8% carbon filler of the 30/70 composite + composite 30/70 | 1.185±0.023 | 1.118±0.027 | 5.65±0.004 |

| L7 | 10% carbon filler of the 30/70 composite + composite 30/70 | 1.187± 0.024 | 1.120±0.029 | 5.73±0.005 |

| L8 | 2% carbon filler of the composite 40/60 + composite 40/60 | 1.168 ± 0.025 | 1.108±0.032 | 5.14±0.007 |

| L9 | 4% carbon filler of the composite 40/60 + composite 40/60 | 1.173 ± 0.021 | 1.110±0.025 | 5.37±0.005 |

| L10 | 6% carbon filler of the composite 40/60 + composite 40/60 | 1.177 ± 0.024 | 1.112±0.028 | 5.52±0.004 |

| L11 | 8% carbon filler of the composite 40/60 + composite 40/60 | 1.182 ± 0.025 | 1.116±0.035 | 5.58±0.002 |

| L12 | 10% carbon filler of the composite 40/60 + composite 40/60 | 1.185 ± 0.026 | 1.118±0.036 | 5.65±0.008 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).