Submitted:

28 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

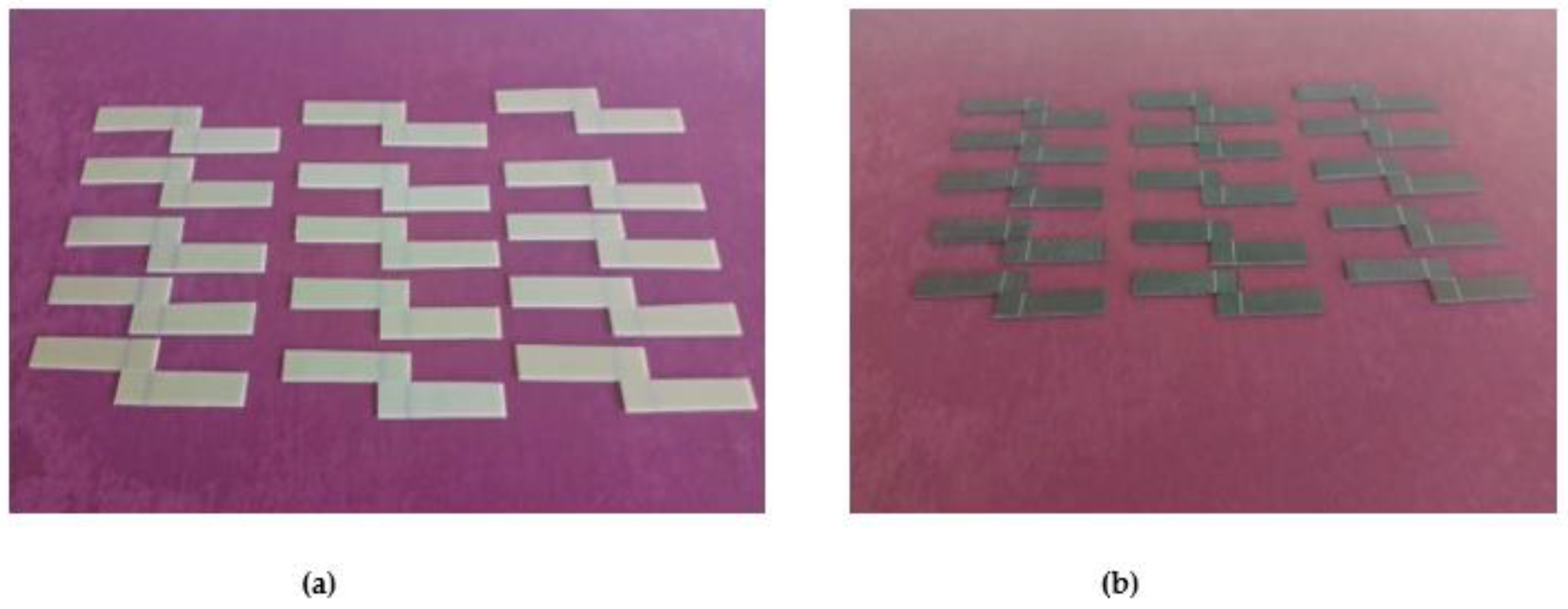

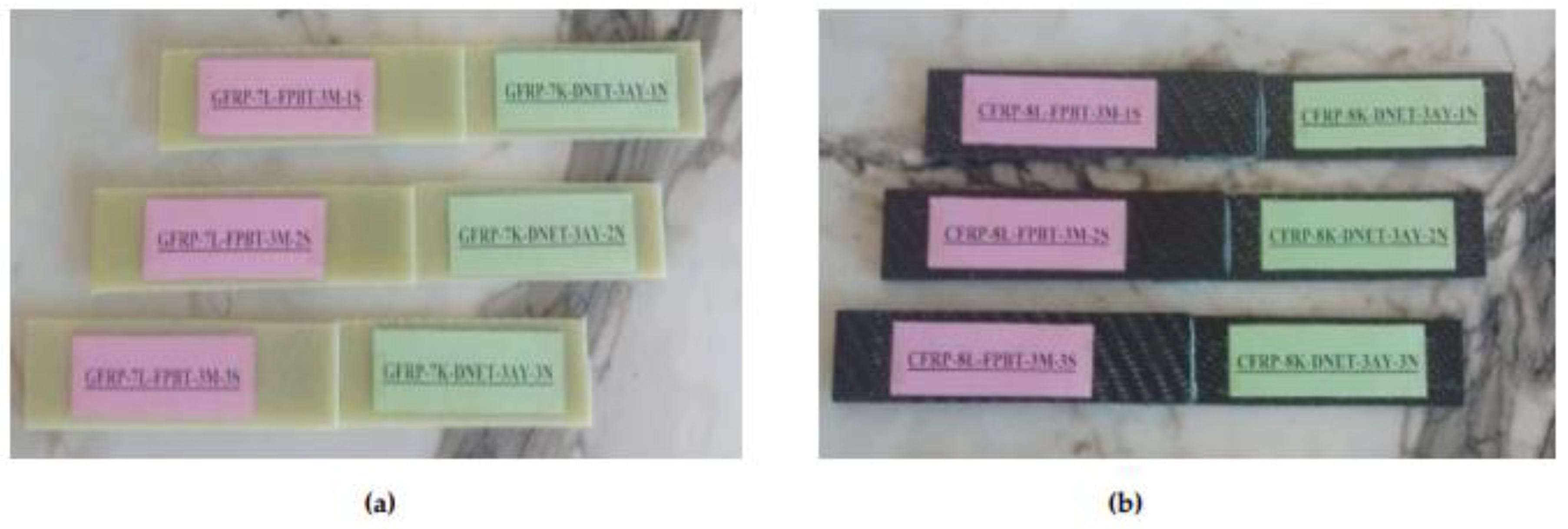

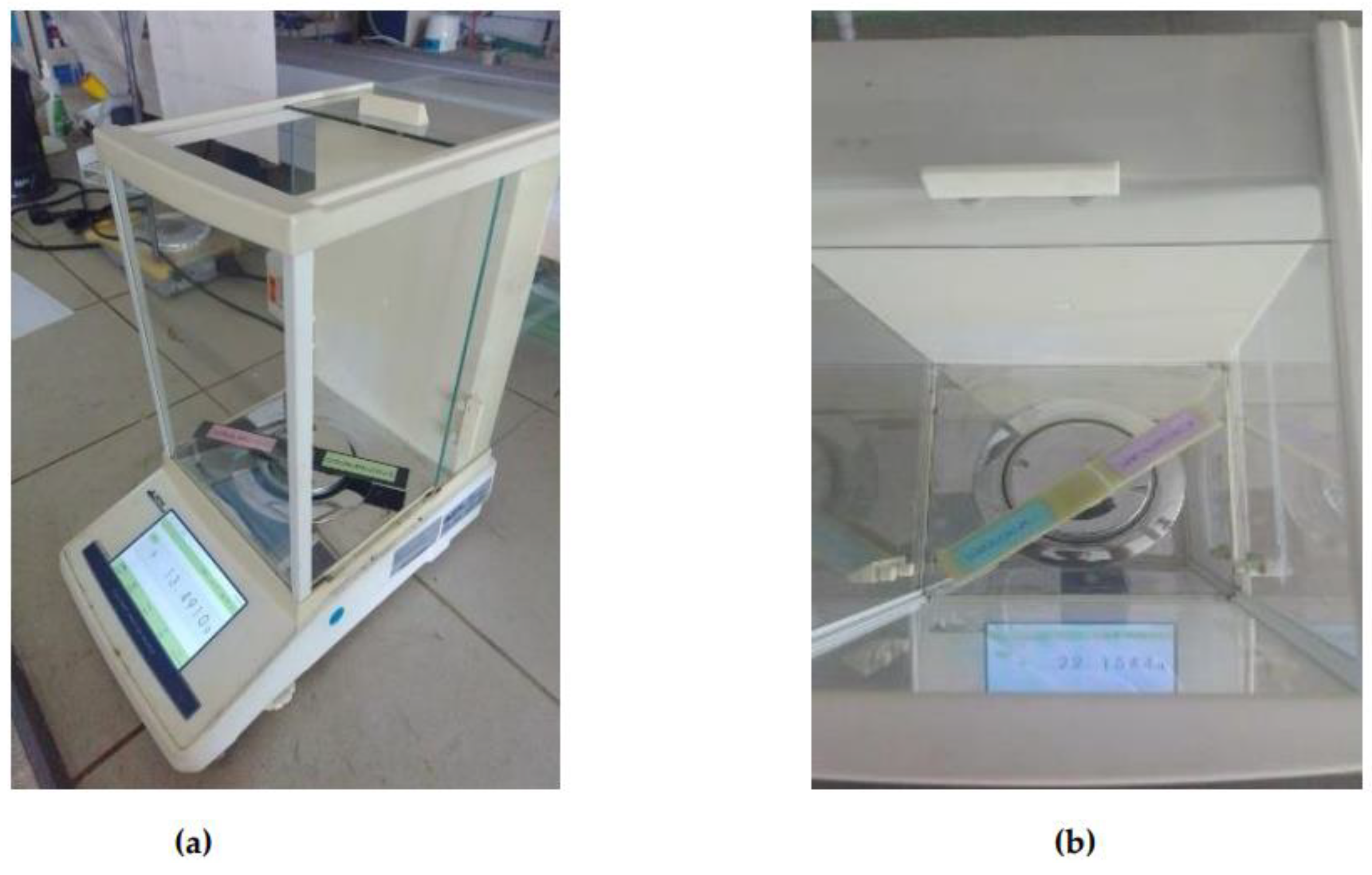

2.1. Comparative Investigation of Moisture Absorption Tendencies of GFRP and CFRP Composite Specimens Under the Effect of Sea Water

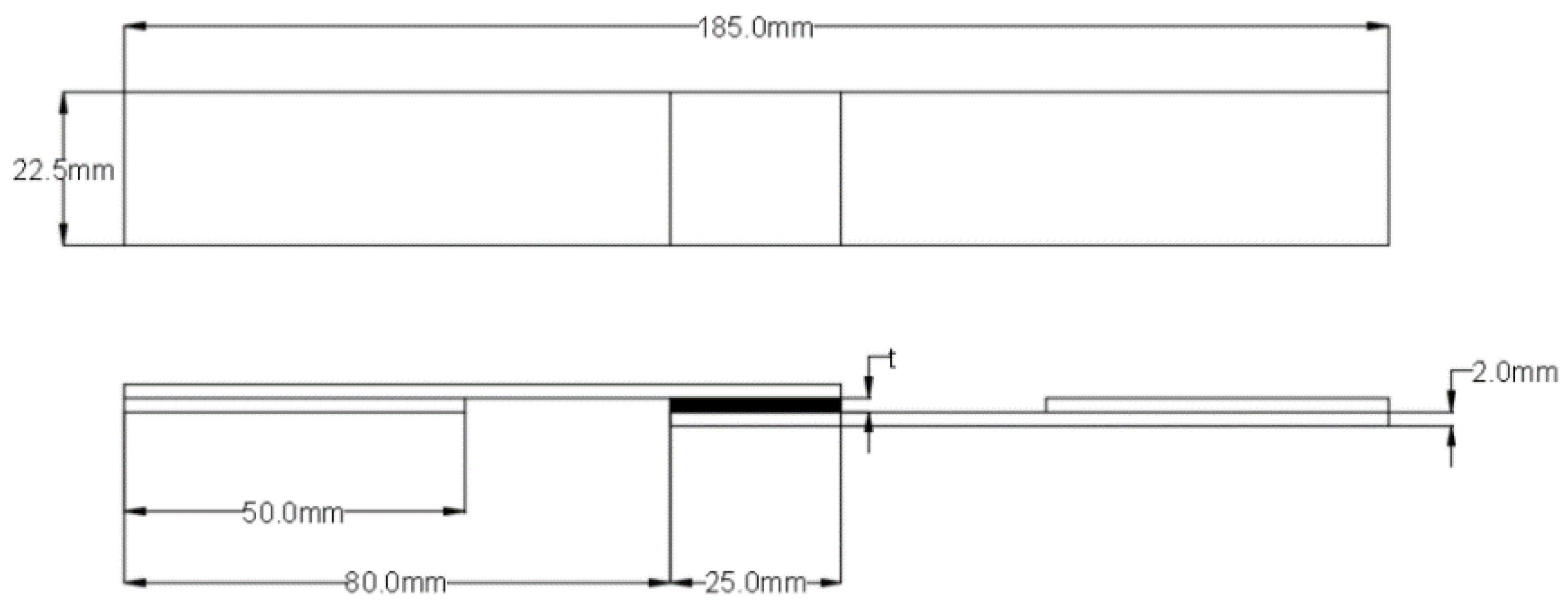

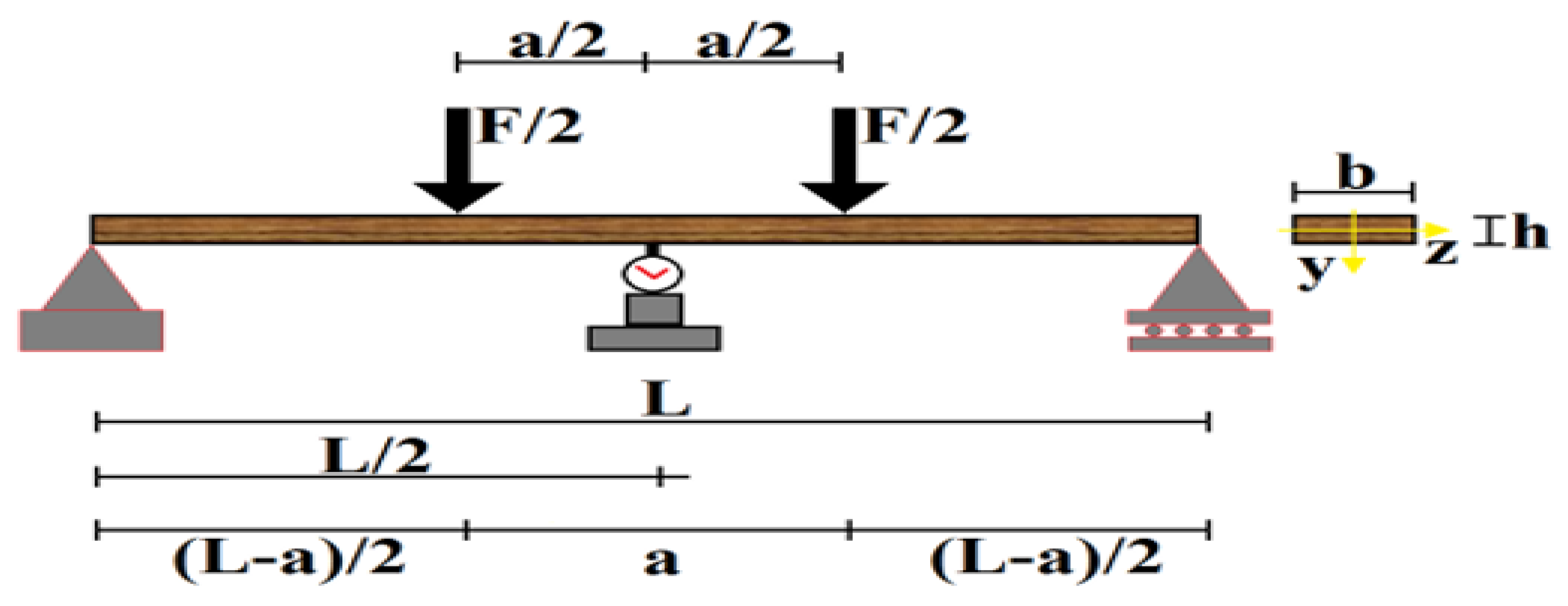

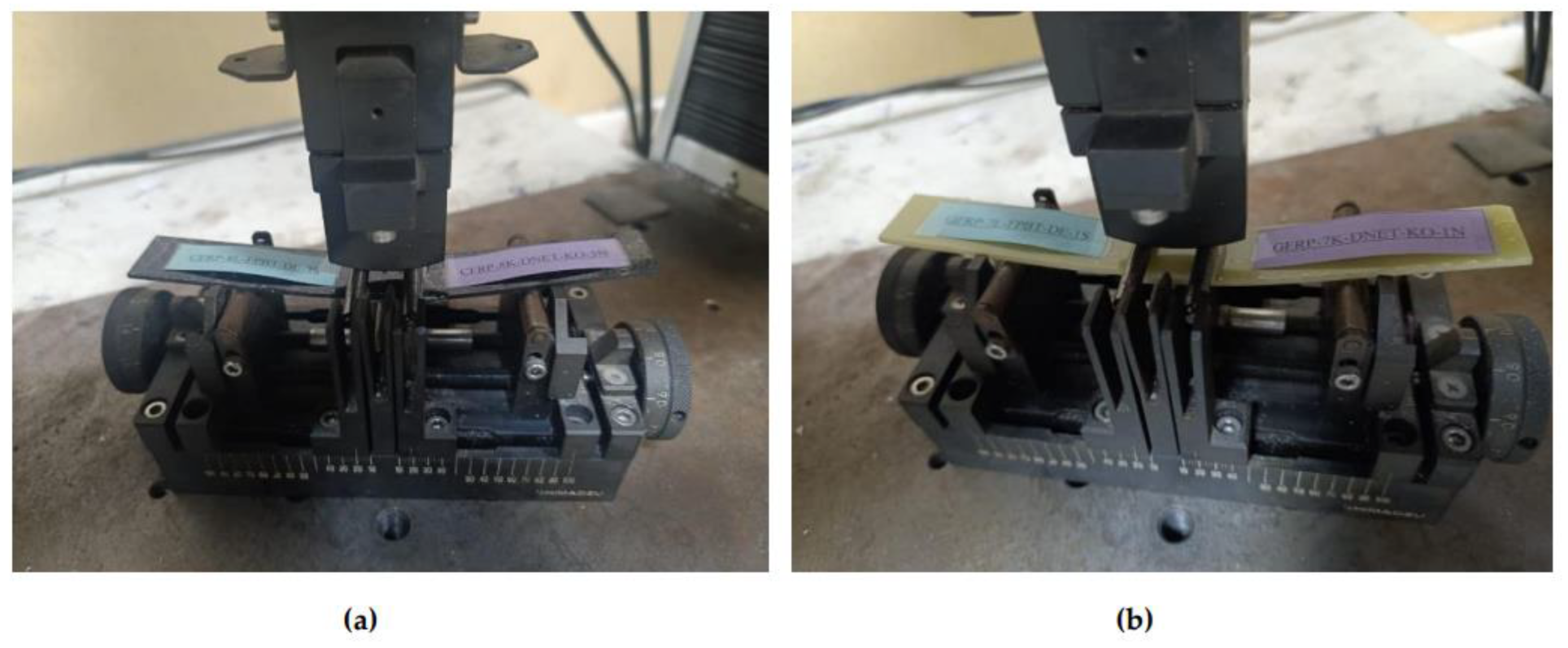

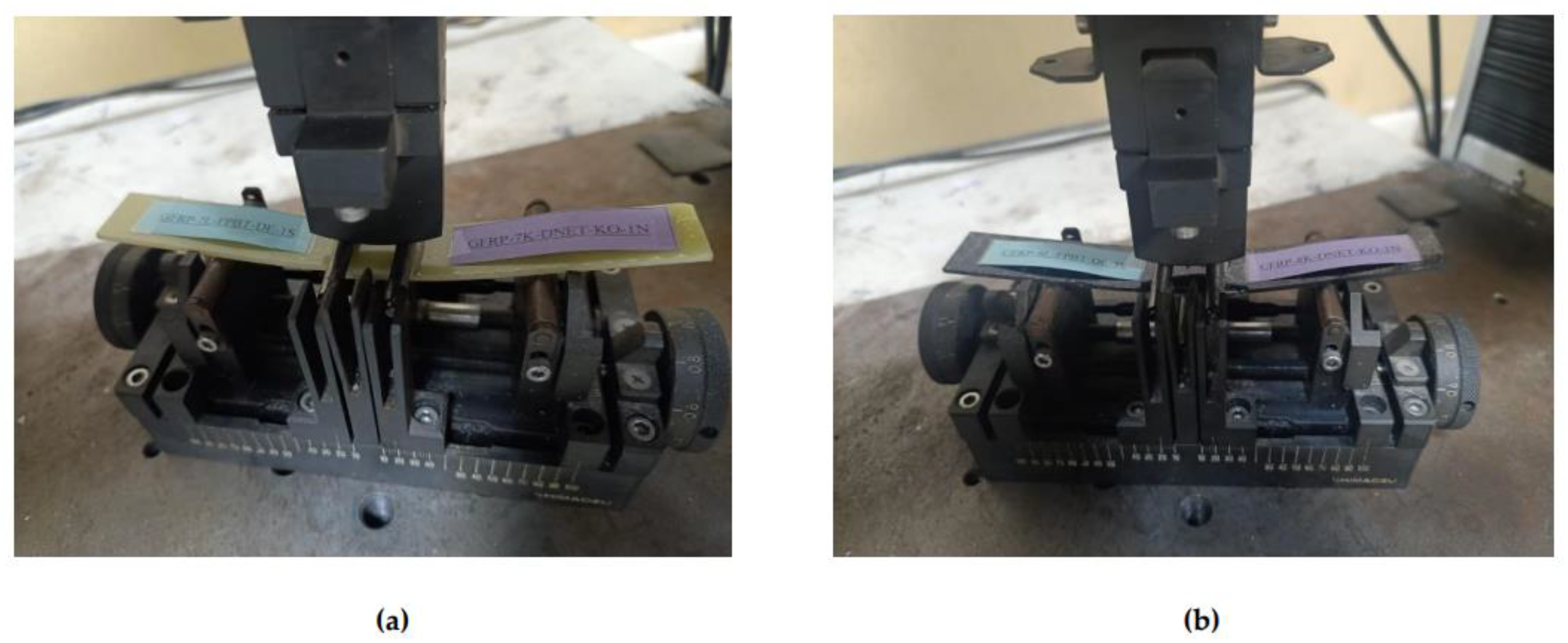

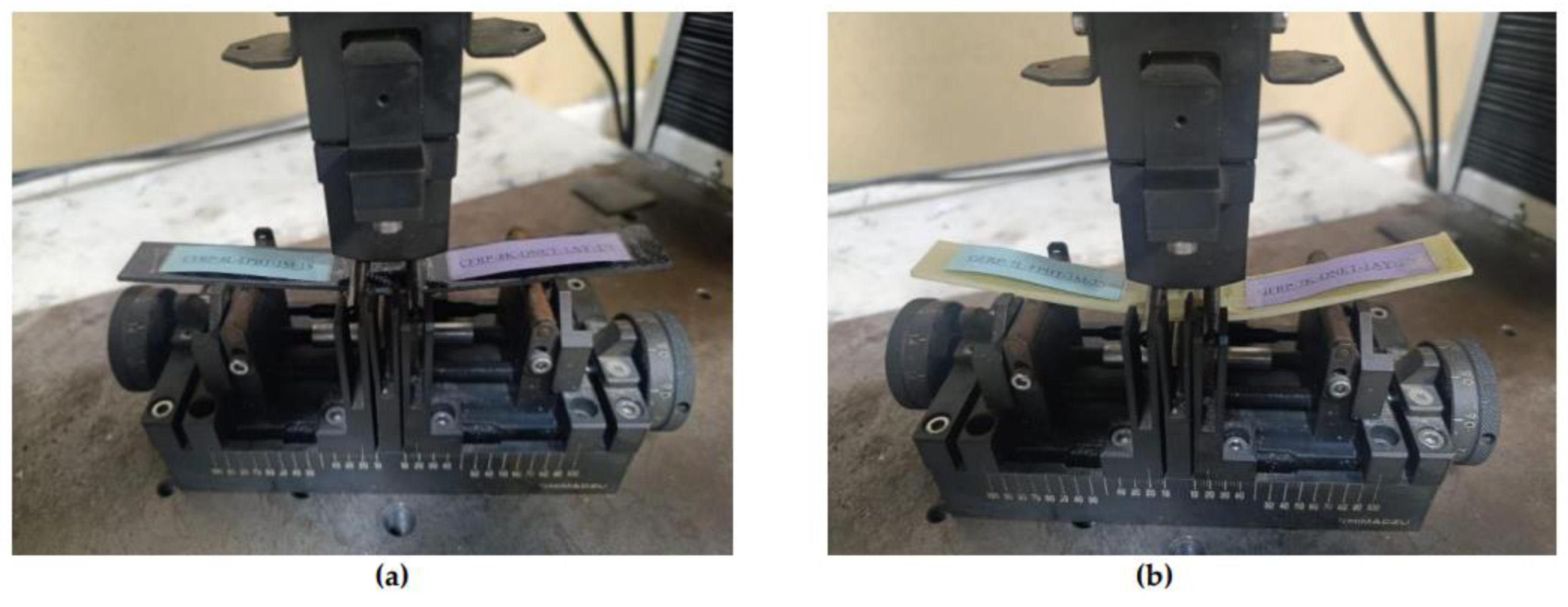

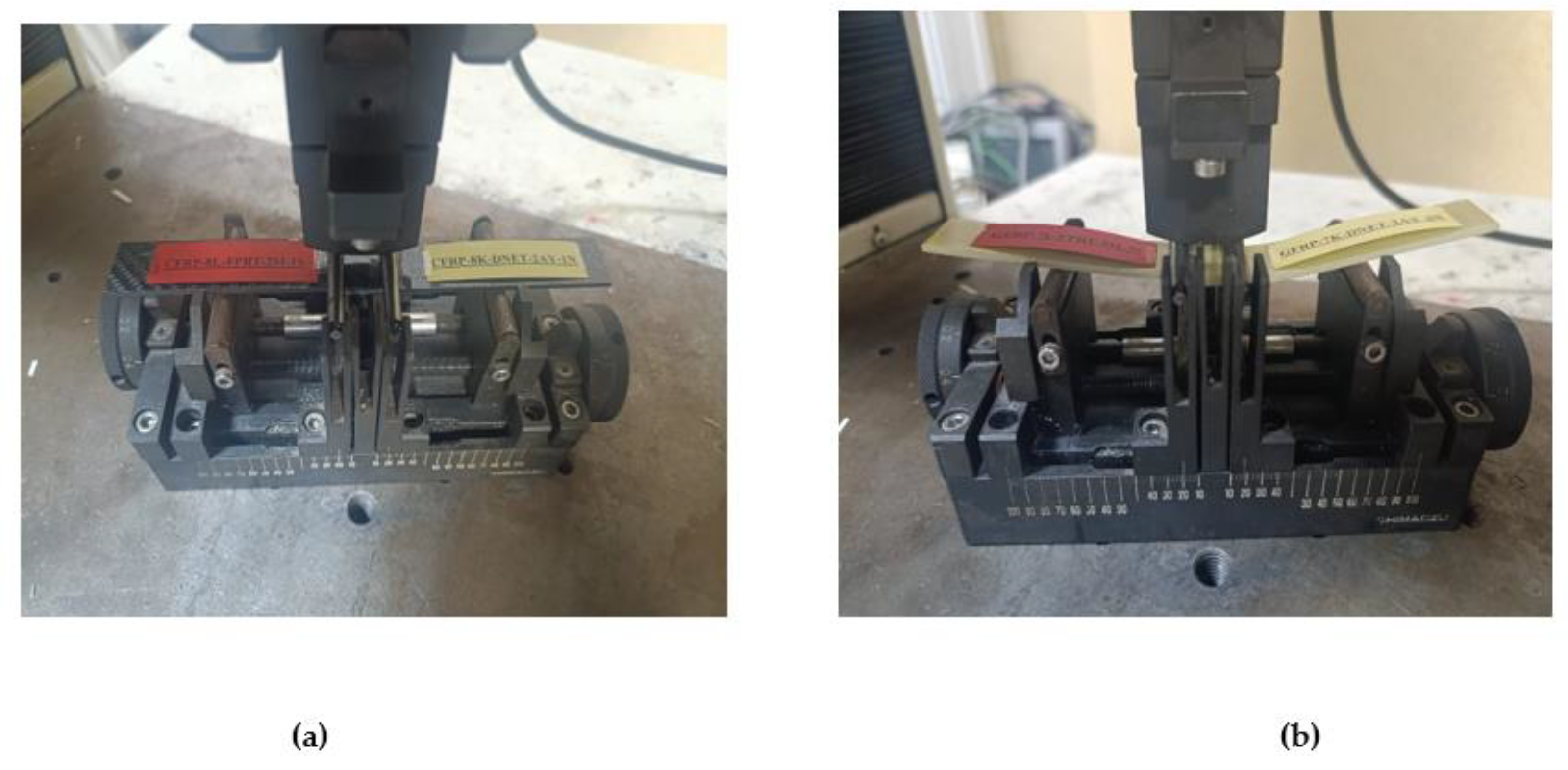

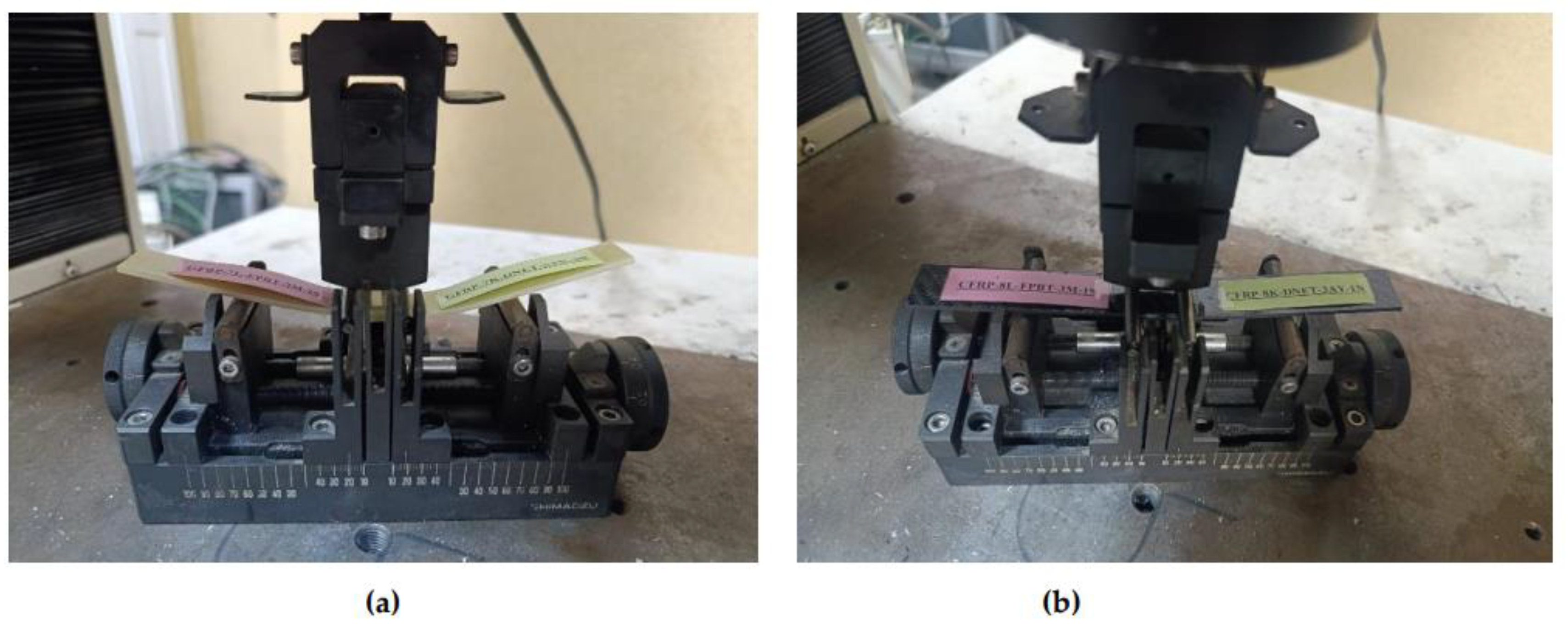

2.2. Four Point Bending Test

3. Results

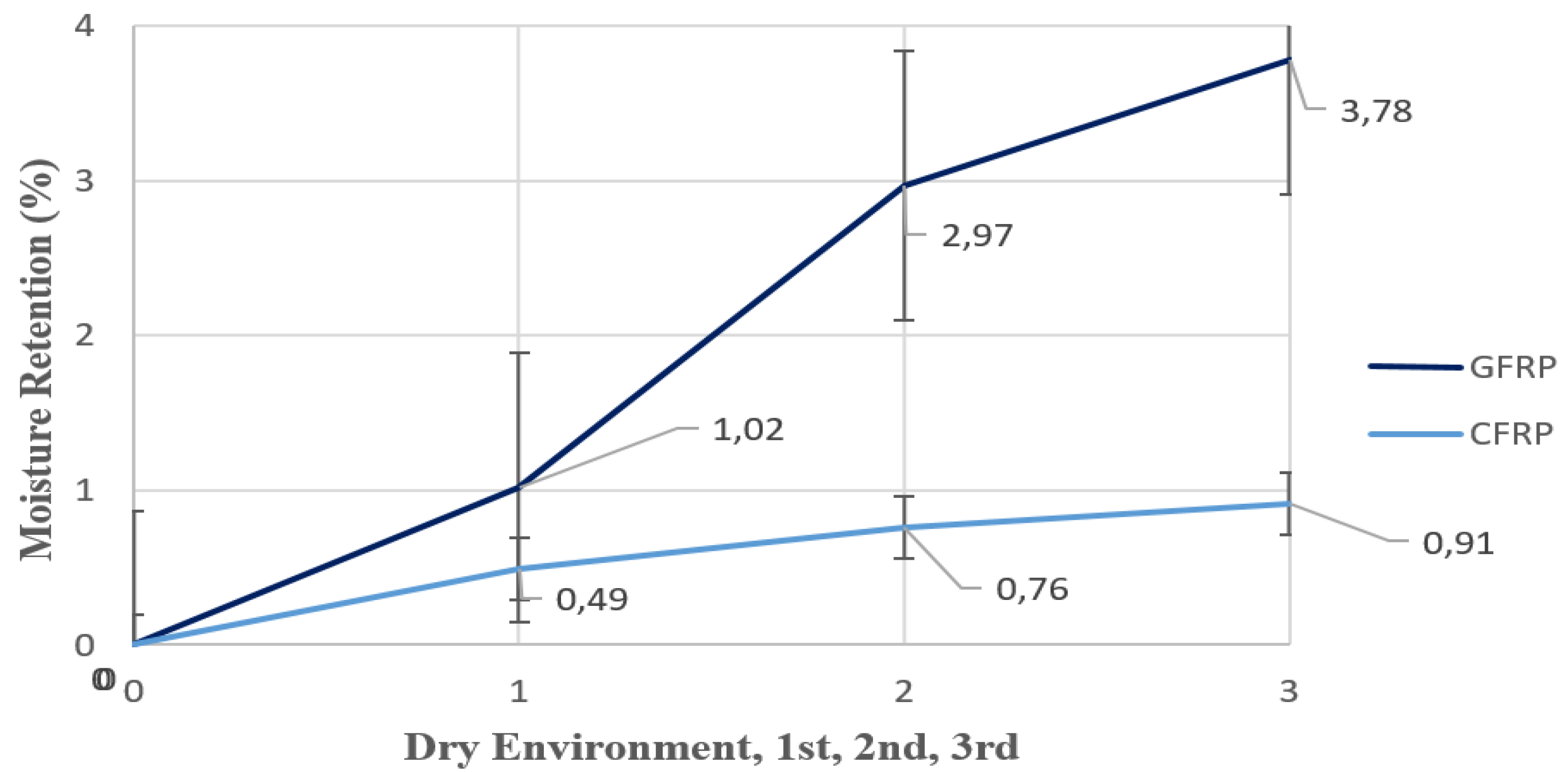

3.1. Moisture Absorption Results

- mk: the dry mass of the sample measured before exposure to moisture (g),

- my: wet mass measured after exposure to seawater for a specified period (g),

- M: moisture retention rate of the sample (%) it expresses.

- While moisture absorption in GFRP increases significantly over time, the increase in CFRP is comparatively lower.

- This indicates that CFRP offers better environmental durability in structural composite applications operating in humid and salty environments, such as offshore wind turbine blade joints.

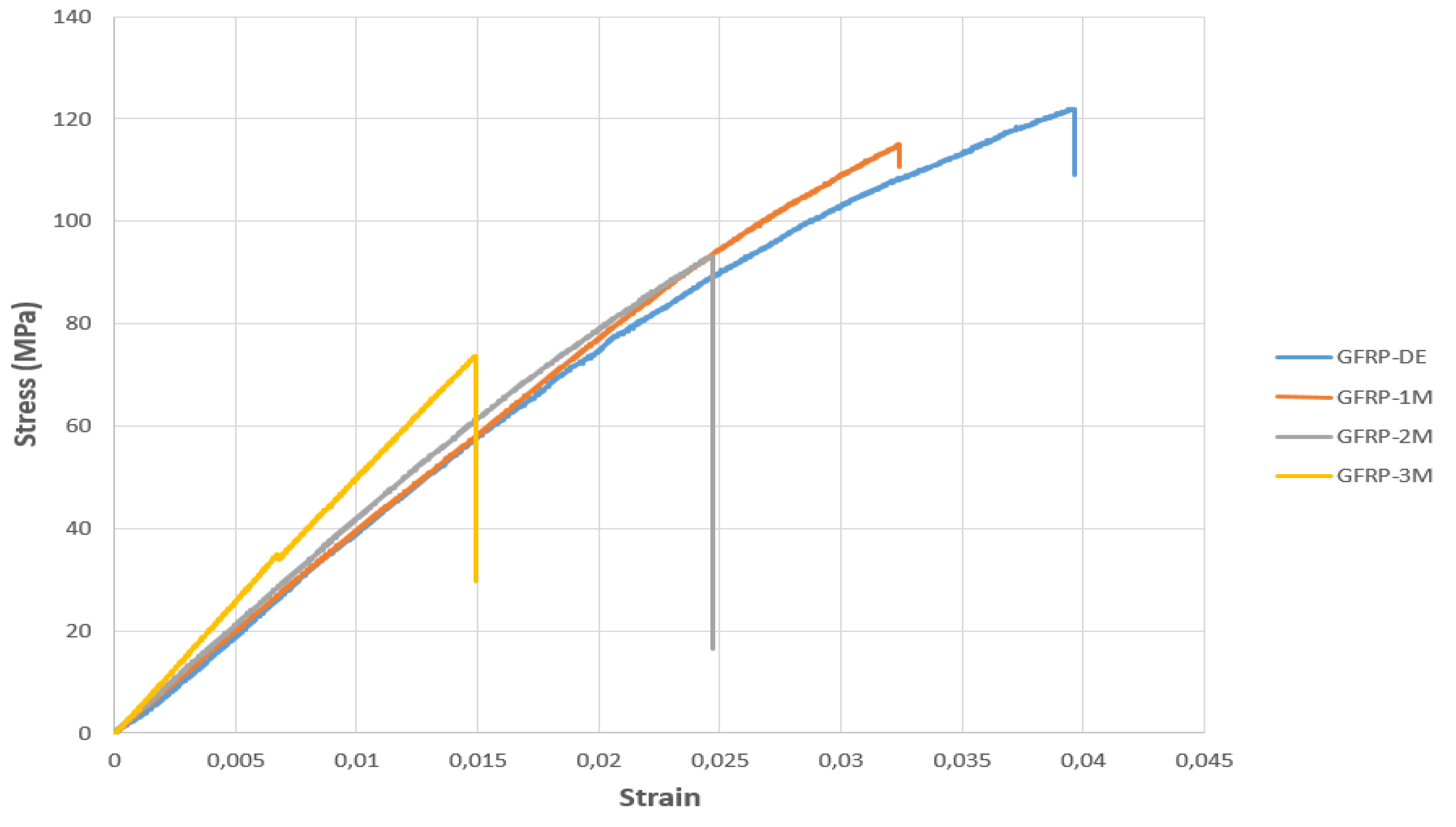

3.2. Four Point Bending Test Results

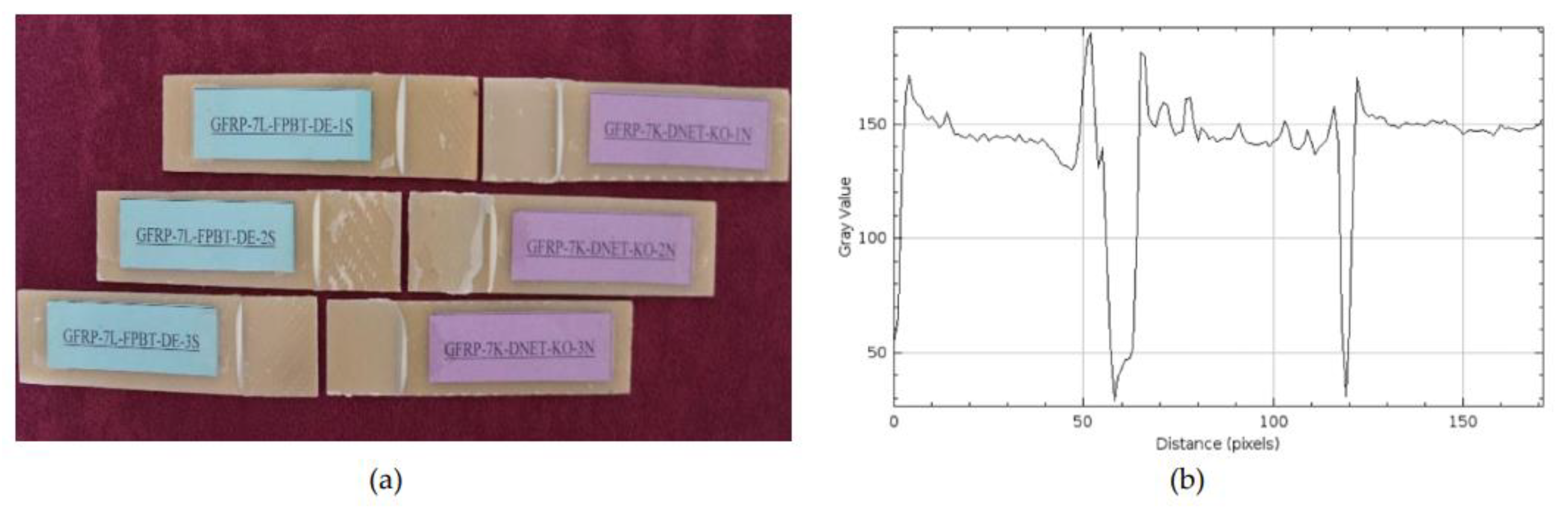

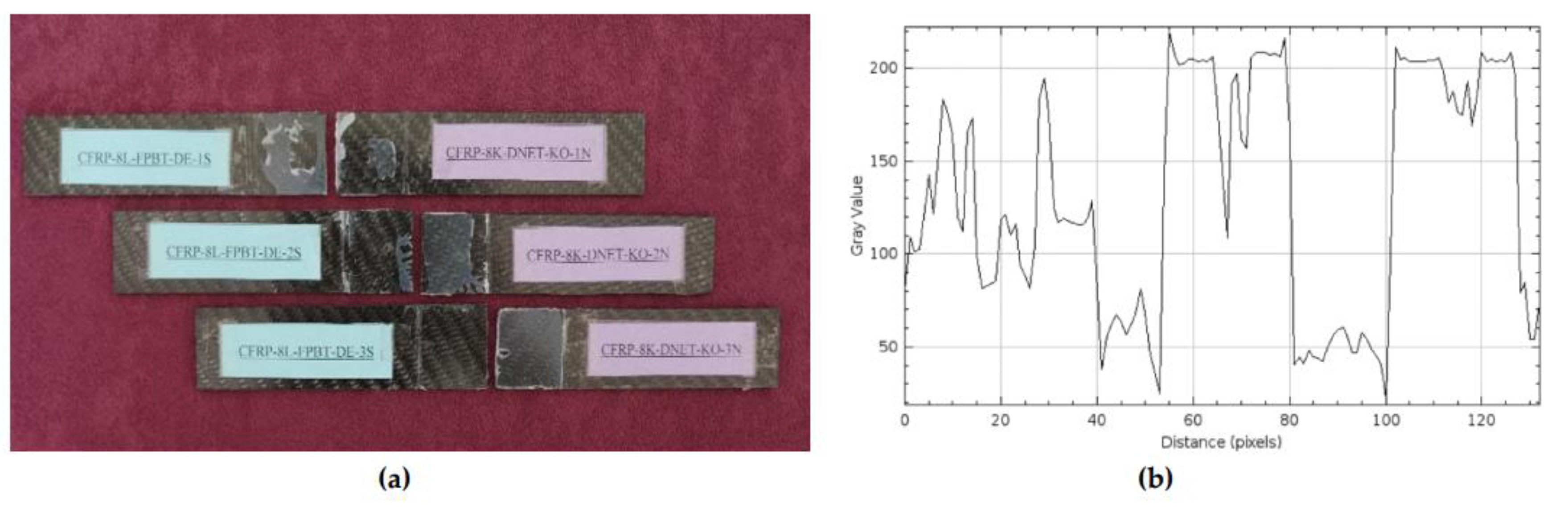

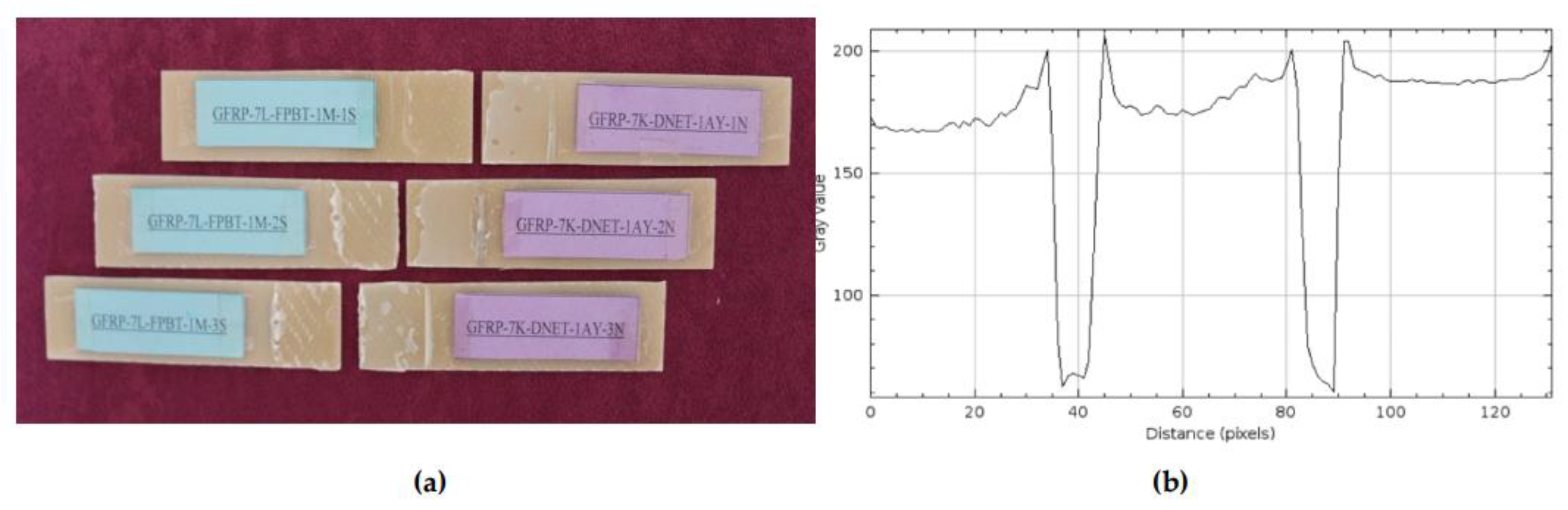

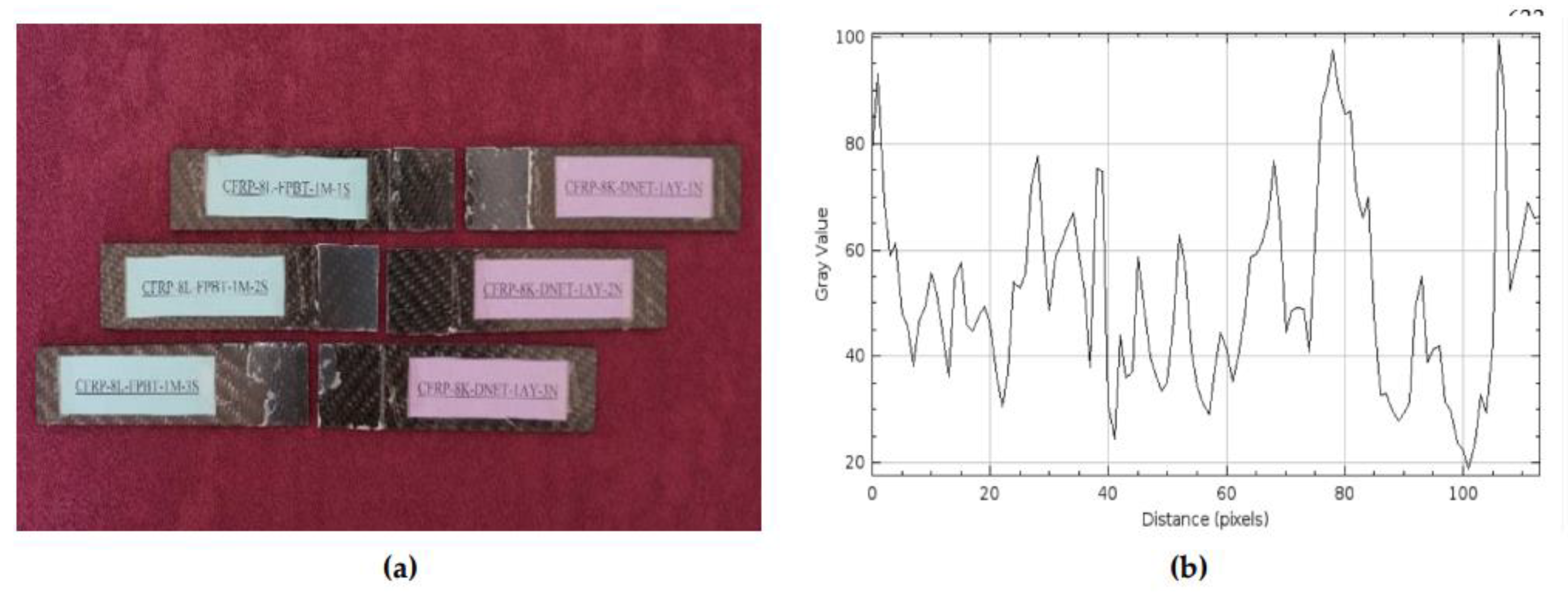

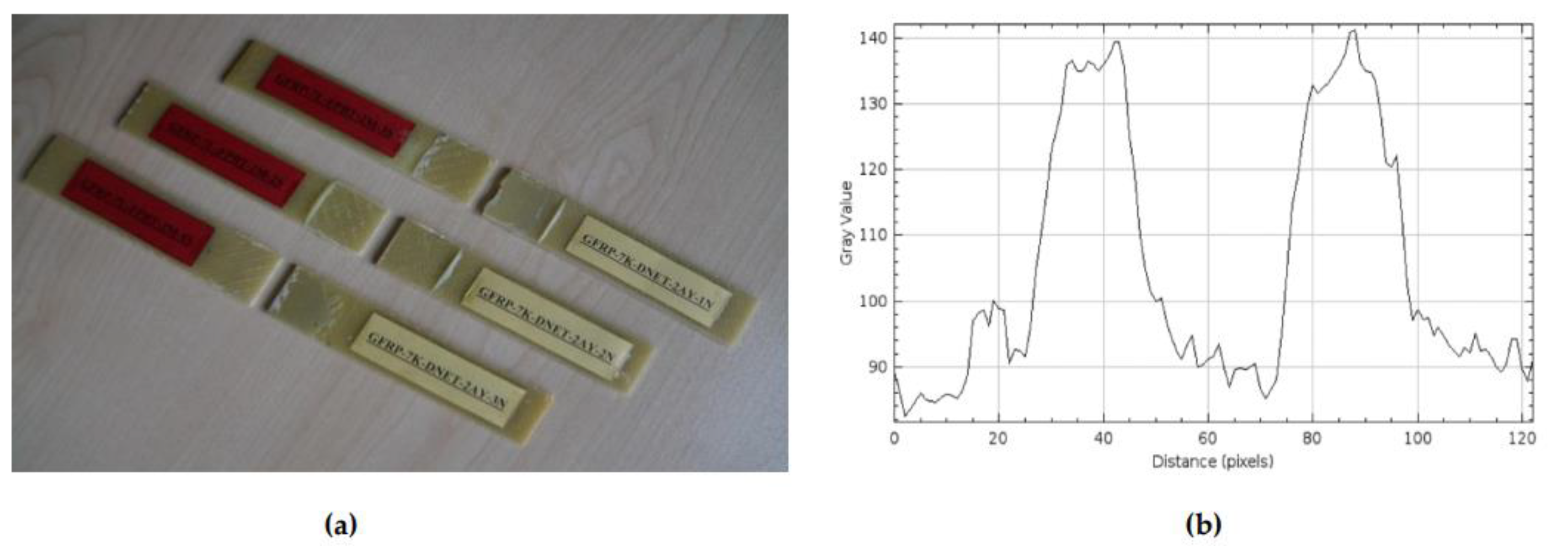

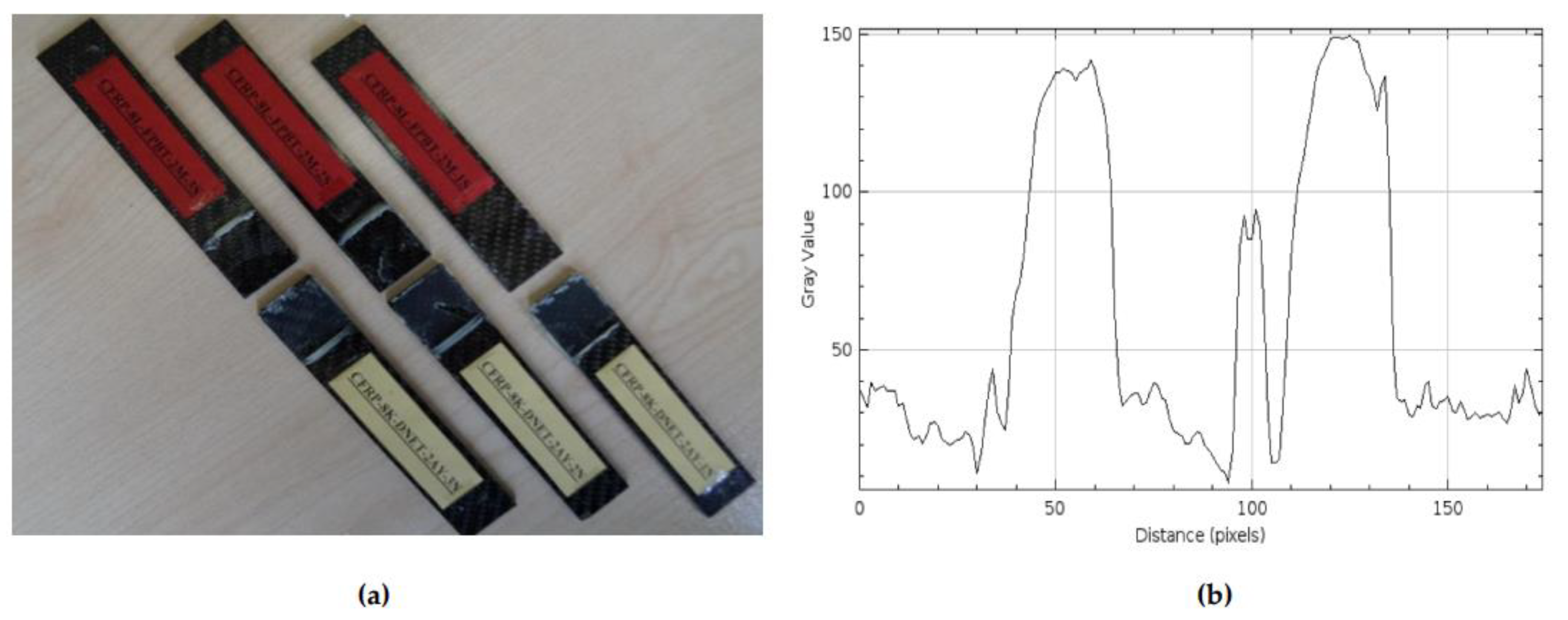

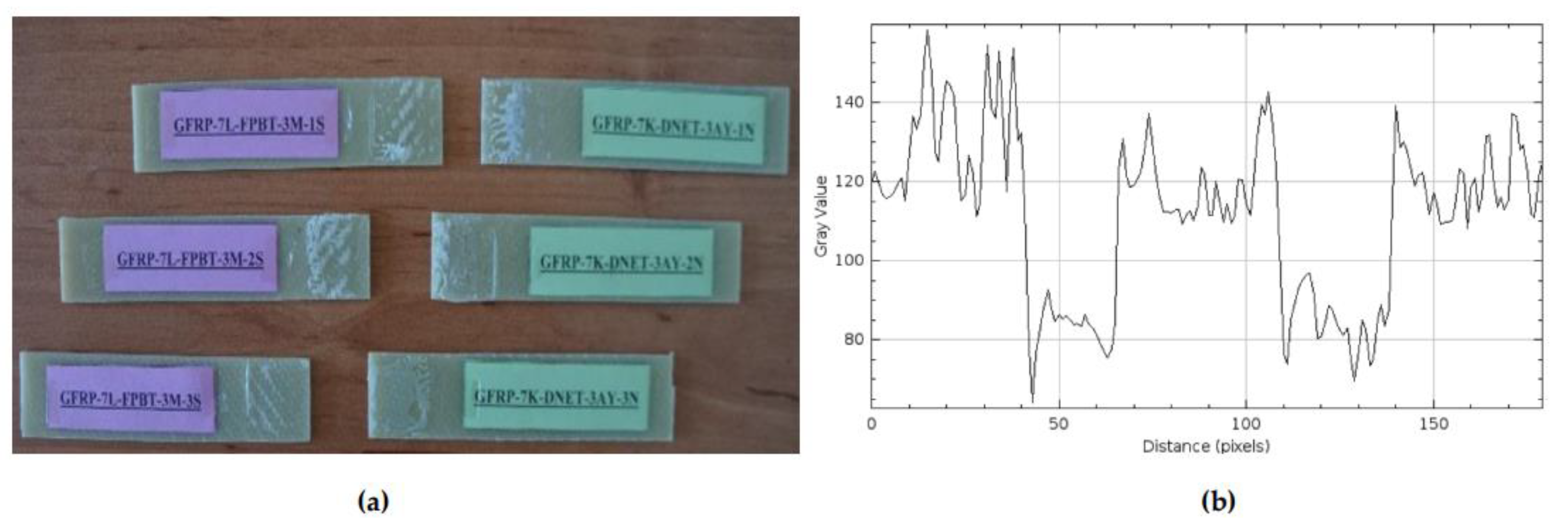

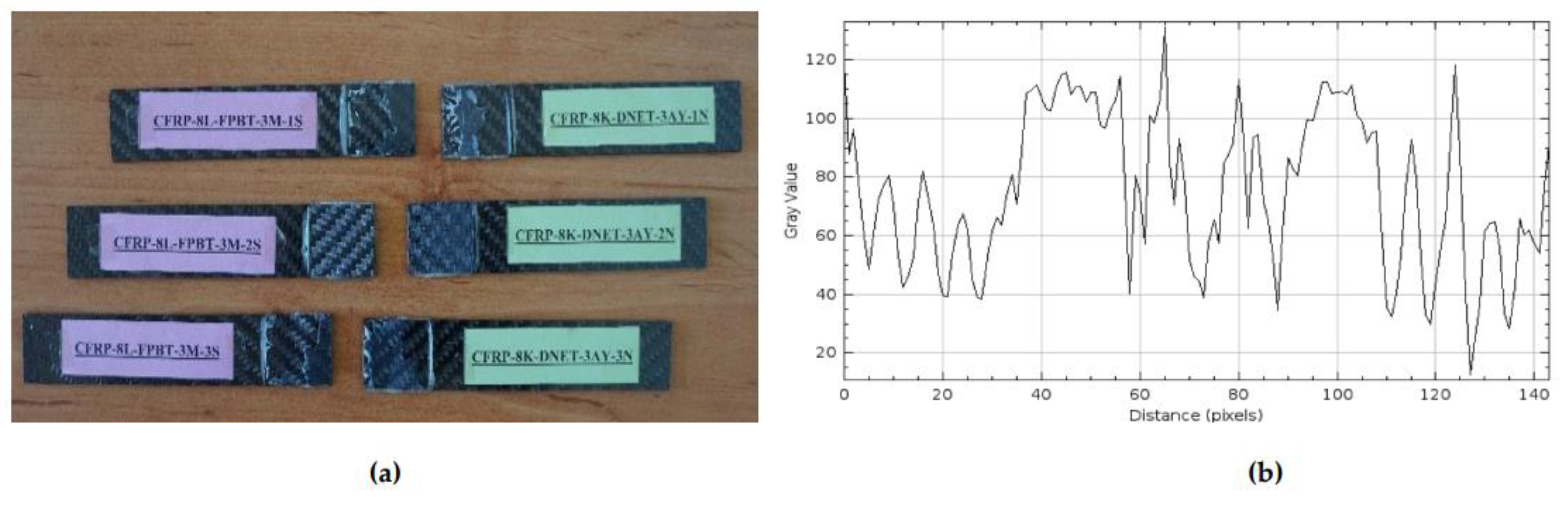

3.2.1. GFRP and CFRP Specimen Details

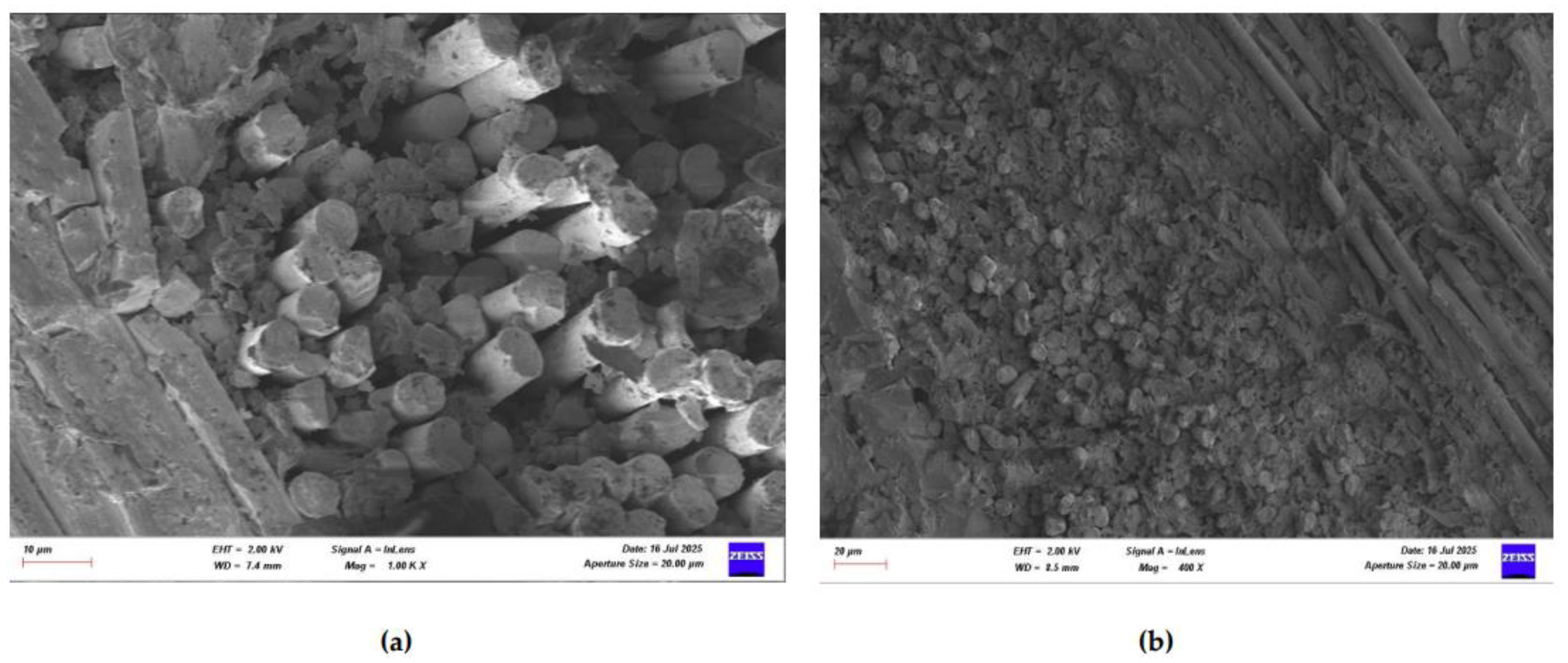

3.3. Damage Investigation of GFRP Specimens Using SEM After Four-Point Bending Test

3.4. Damage Investigation of CFRP Specimens Using SEM After Four-Point Bending Test

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agarwal, B. D.; Broutman, L. J.; Chandrashekhara, K. Analysis and performance of fiber composites; John Wiley & Sons, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, I. M.; Ishai, O.; Daniel, I. M.; Daniel, I. Engineering mechanics of composite materials; New York: Oxford university press, 1994; Vol. 3, pp. 256–256. [Google Scholar]

- Mallick, P. K. Materials, manufacturing, and design. Mechanical Engineering (Marcel Dekker, Inc.) 2007, 83, 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Mouritz, A. P.; Gibson, A. G. Fire properties of polymer composite materials; Springer Netherlands; Dordrecht, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Khoshmanesh, S.; Watson, S. J.; Zarouchas, D. The effect of the fatigue damage accumulation process on the damping and stiffness properties of adhesively bonded composite structures. Composite Structures 2022, 287, 115328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y. M.; Han, K. S. Fracture mechanics approach for failure of adhesive joints in wind turbine blades. Renewable energy 2014, 65, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. S.; Yoo, J. S.; Yi, Y. M.; Kim, C. G. Failure mode and strength of uni-directional composite single lap bonded joints with different bonding methods. Composite structures 2006, 72(4), 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertgenç Yoldaş, D.; Yoldaş, M. F. Investigation of Diffusion of Different Composite Materials on the Damage Caused by Axial Impact Adhesive Joints. Journal of Composites Science 2025, 9(4), 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçınkaya, S.; Mertgenç Yoldaş, D.; Yoldaş, M. F. Experimental Investigation of the Effect of Seawater on Glass and Carbon Fiber Composites via Mechanical Characterization. Journal of Composites Science 2025, 9(3), 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y. M.; Han, K. S. Fracture mechanics approach for failure of adhesive joints in wind turbine blades. Renewable energy 2014, 65, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshmanesh, S.; Watson, S. J.; Zarouchas, D. New indicator for damage localization in a thick adhesive joint of a composite material used in a wind turbine blade. Engineering Structures 2023, 283, 115870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosemeier, M.; Krimmer, A.; Bardenhagen, A.; Antoniou, A. Tunneling crack initiation in trailing-edge bond lines of wind-turbine blades. AIAA journal 2019, 57(12), 5462–5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiee, R.; Hashemi-Taheri, M. R. Failure analysis of a composite wind turbine blade at the adhesive joint of the trailing edge. Engineering Failure Analysis 2021, 121, 105148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musial, W.; Bourne, B.; Hughes, S.; Zuteck, M. D. Four-Point Bending Strength Testing of Pultruded Fiberglass Composite Wind Turbine Blade Sections (No. NREL/CP-500-30565); National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL); Golden, CO (United States), 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Santiago, O.; Robles-Ocampo, J. B.; Gálvez, E.; Sevilla-Camacho, P. Y.; de la Cruz, S.; Rodríguez-Reséndiz, J.; Hernández, E. Bending Behavior Analysis of Box Beams with the Reinforcement of Composite Materials for Wind Turbine Blades. Fibers 2023, 11(12), 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musial, W.; Bourne, B.; Hughes, S.; Zuteck, M. D. Four-Point Bending Strength Testing of Pultruded Fiberglass Composite Wind Turbine Blade Sections (No. NREL/CP-500-30565); National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL); Golden, CO (United States), 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Arwood, Z.; Young, S.; Foster, D.; Penumadu, D. Quality Investigation of Pultruded Carbon Fiber Panels Subjected to Four-Point Flexure via Fiber Optic Sensing. Materials 2025, 18(1), 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTMD5868-01. Standard Test Method for Lap Shear Adhesion for Fiber Reinforced Plastic (FRP) Bonding; ASTM International; West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Croccolo, D.; De Agostinis, M.; Fini, S.; Olmi, G. Influence of the engagement ratio on the shear strength of an epoxy adhesive by push-out tests on pin-and-collar joints: Part I: Campaign at room temperature. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2016, 67, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R. F. Principles of composite material mechanics; CRC press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM International. ASTM D6272-17: Standard Test Method for Flexural Properties of Unreinforced and Reinforced Plastics and Electrical Insulating Materials by Four-Point Bending; ASTM International; West Conshohocken, PA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTMD790;Standard Test Methods for Flexural Properties of Unreinforced and Reinforced Plastics and Electrical Insulating Materials; ASTM International; West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- Korkees, F. Moisture absorption behavior and diffusion characteristics of continuous carbon fiber reinforced epoxy composites: A review. Polymer-Plastics Technology and Materials 2023, 62(14), 1789–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, A.; Pathak, K. Mechanical stability of dental materials. In Applications of nanocomposite materials in dentistry; Woodhead Publishing, 2019; pp. 285–305. [Google Scholar]

- Selzer, R.; Friedrich, K. Mechanical properties and failure behaviour of carbon fibre-reinforced polymer composites under the influence of moisture. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 1997, 28(6), 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code (English) | Code (Turkish) | Description |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-2M-1S | GFRP-7K-DNET-2AY-1N | 7-layer GFRP, four-point bending test, 2 months in seawater, specimen no. 1 |

| CFRP-8L-FPBT-3M-2S | CFRP-8K-DNET-3AY-2N | 8-layer CFRP, four-point bending test, 3 months in seawater, specimen no. 2 |

| Dry sample code |

Dry Weight (g) |

Store time |

Soaked in sea water Sample code |

Wet Weight (g) |

Moisture Retention Rate (%) |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-DE | 17.2374 | 1st Month | GFRP-7L-FPBT-1M-1S | 17.3524 | 1.02 |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-DE | 17.2374 | 2nd Month | GFRP-7L-FPBT-2M-2S | 17.8593 | 2.97 |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-DE | 17.2374 | 3rd Month | GFRP-7L-FPBT-3M-3S | 17.9707 | 3.78 |

| Dry sample code | Dry Weight (g) | Store time | Soaked in sea water Sample code |

Wet Weight (g) | Moisture Retention Rate (%) |

| CFRP-8L-FPBT-DE | 14.7695 | 1st Month | CFRP-8L-FPBT-1M-1S | 14.8808 | 0.49 |

| CFRP-8L-FPBT-DE | 14.7695 | 2nd Month | CFRP-8L-FPBT-2M-2S | 14.9247 | 0.76 |

| CFRP-8L-FPBT-DE | 14.7695 | 3rd Month | CFRP-8L-FPBT-3M-3S | 14.9252 | 0.91 |

| Exposure Time (Months) | GFRP Moisture Absorption Rate (%) | CFRP Moisture Absorption Rate (%) |

| 1 | 1.02 | 0.49 |

| 2 | 2.97 | 0.76 |

| 3 | 3.78 | 0.91 |

| Specimen Code | Flexural Stress (MPa) | Strain (ε) | Seawater Exposure Duration |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-DE | 121.693 | 0.0395 | None (Dry Condition) |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-1M | 114.951 | 0.0323 | 1 Month |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-2M | 92.615 | 0.0244 | 2 Months |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-3M | 72.794 | 0.0146 | 3 Months |

| Specimen Code | Flexural Stress (MPa) | Strain (ε) | Seawater Exposure Duration |

| CFRP-8L-FPBT-DE | 148.572 | 0.0270 | None (Dry Condition) |

| CFRP-8L-FPBT-1M | 122.385 | 0.0254 | 1 Month |

| CFRP-8L-FPBT-2M | 121.944 | 0.0206 | 2 Months |

| CFRP-8L-FPBT-3M | 109.557 | 0.0185 | 3 Months |

| Specimen Code |

Elastic Modulus (MPa) |

Material Type |

Change Compared to Initial (%) |

| CFRP-8L-FPBT-DE | 6.270 | CFRP | Referans |

| CFRP-8L-FPBT-1M | 6.189 | CFRP | 1,29 |

| CFRP-8L-FPBT-2M | 6.106 | CFRP | 2,62 |

| CFRP-8L-FPBT-3M | 6.052 | CFRP | 3,48 |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-DE | 3.878 | GFRP | Referans |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-1M | 3.756 | GFRP | 3,15 |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-2M | 3.644 | GFRP | 6,42 |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-3M | 3.510 | GFRP | 9,45 |

| Figure No | Condition | Fiber-Matrix Interface | Observed Damage Mechanisms | Microstructural Condition | Mechanical Strength |

| Figure 25 | Dry Condition | Strong bonding | Fiber pull-out | Regular fiber alignment, minimal voids | High |

| Figure 26 | 1 Month Seawater | Initial degradation | Debonding, fiber pull-out, microcracks | Matrix swelling, weakened bonding | Reduced |

| Figure 27 | 2 Months Seawater | Significant damage | Fiber breakage, matrix fragmentation, voids | Loss of fiber-matrix interaction | Reduced |

| Figure 28 | 3 Months Seawater | Almost completely degraded | Macrocracks, chemical matrix degradation | Fibers free, merged cracks, brittle failure | Low |

| Figure No | Condition |

Fiber-Matrix Interface |

Observed Damage Mechanisms |

Microstructural Condition |

Mechanical Strength |

| Figure 29 | Dry Condition |

High integrity |

Balanced fiber breakage | Regular structure, controlled fracture | High |

| Figure 30 | 1 Month Seawater | Partial debonding |

Microcracks, matrix deformation | Initial degradation, weakened bonding | Reduced |

| Figure 31 | 2 Months Seawater | Severe degradation |

Fiber-matrix separation, resin cracking and voids | Brittle fracture, irregular fiber breakage | Lower |

| Figure 32 | 3 Months Seawater | Interface detached |

Delamination, void formation | Free fibers | Very low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).