Submitted:

08 October 2025

Posted:

09 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

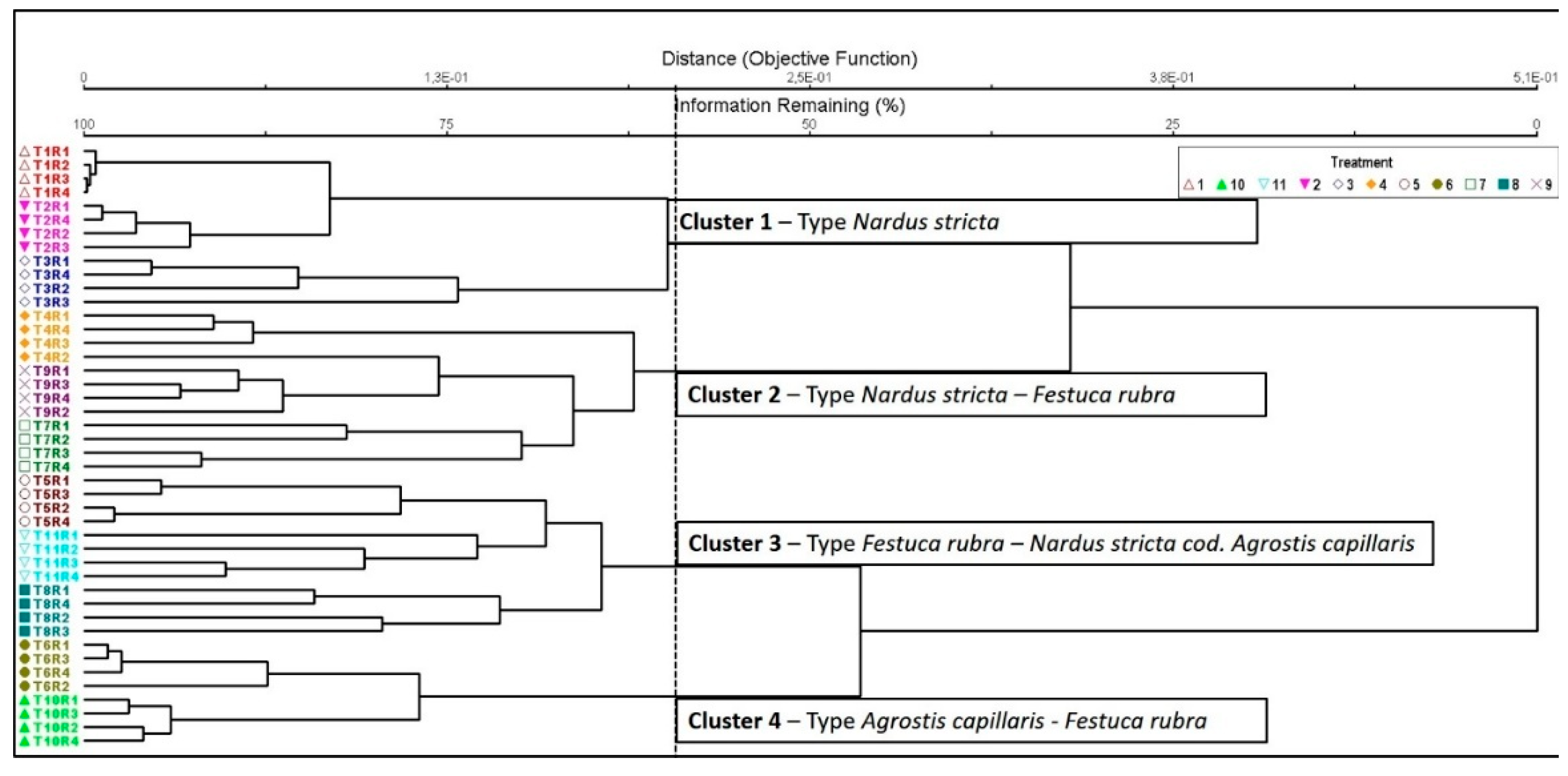

2.1. The Influence of Management Scenario on Floristic Composition

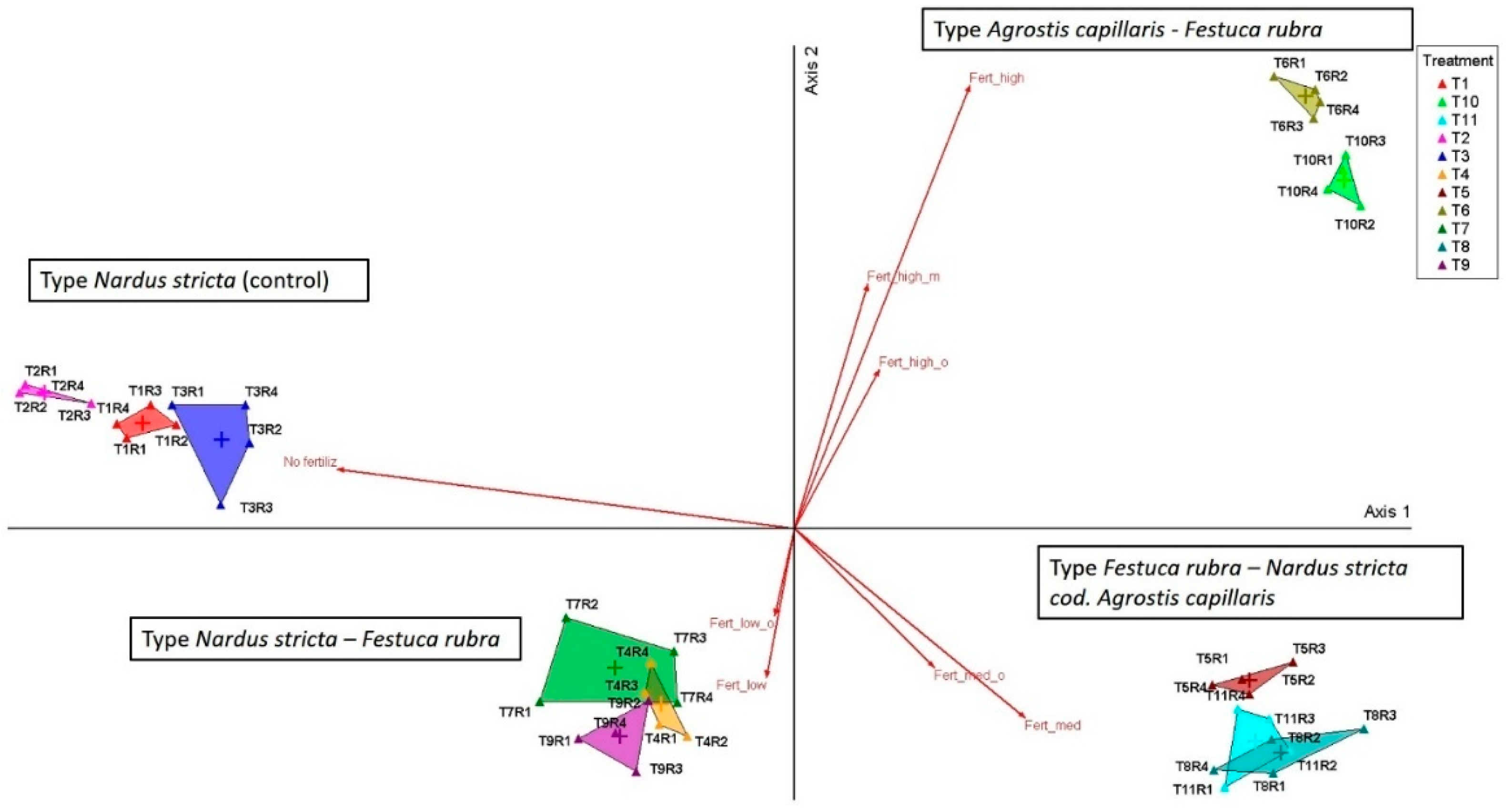

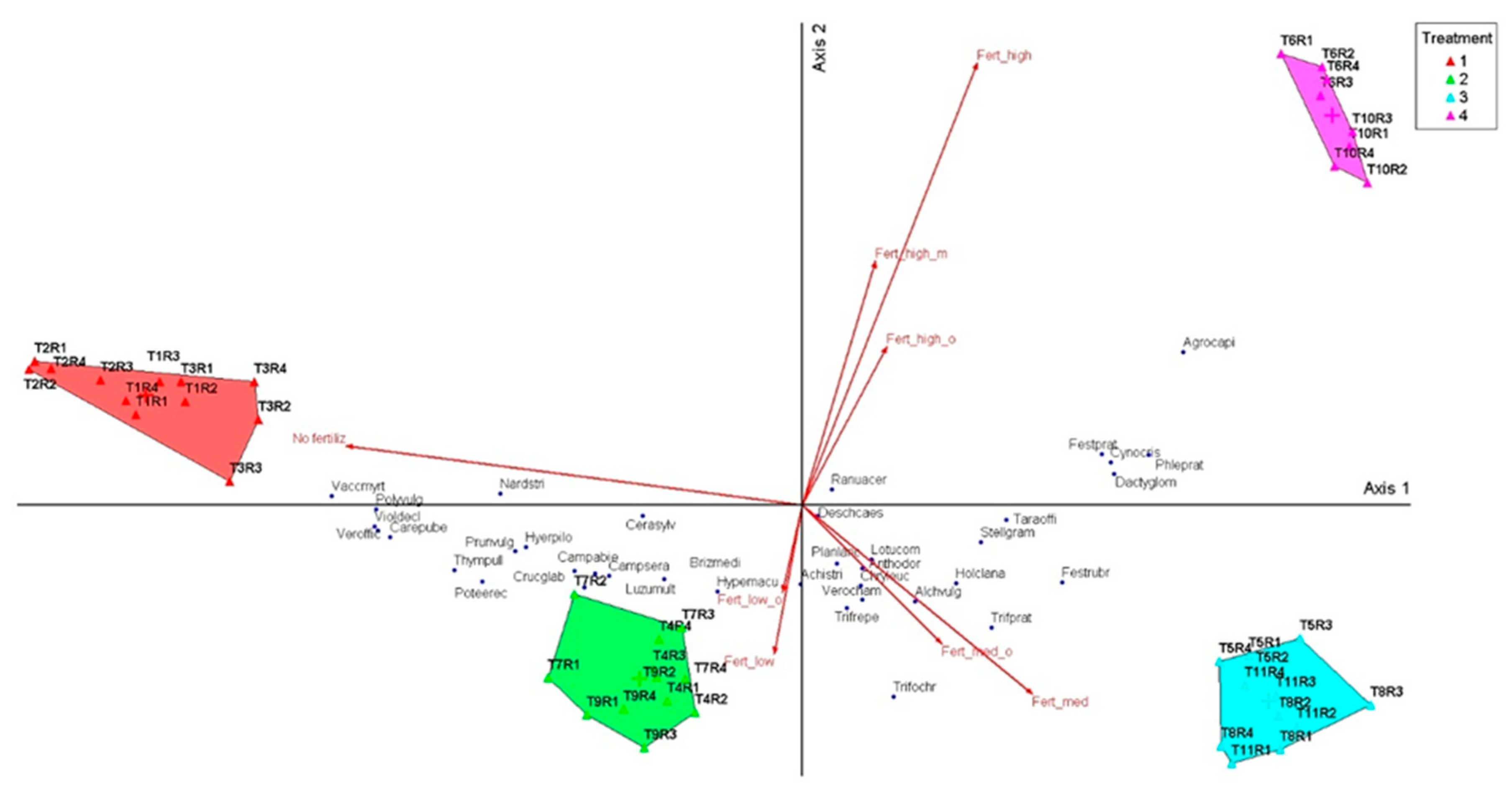

2.2. Plant Community Patterns Explored Through Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA)

2.3. The Analysis of Community Composition Through Multi-Response Permutation Procedure (MRPP)

2.4. The Indicator Species Analysis (ISA) on Plant Communities Shaped by Management Scenarios

- •Group 1 (Nardus stricta grasslands) – characterized by strong indicators with high significance: Nardus stricta, Campanula abietina, Cerastium sylvaticum, Cruciata glabra, Polygala vulgaris, Viola declinata, Veronica officinalis, Vaccinium myrtillus.

- •Group 2 (transitional communities) – associated with grasses (Anthoxanthum odoratum, Briza media, Cynosurus cristatus) and legumes (Lotus corniculatus, Trifolium ochroleucon, Trifolium repens).

- •Group 3 (Festuca rubra–Agrostis capillaris co-dominance) – marked by species tolerant to moderate inputs: Festuca rubra, Holcus lanatus, Trifolium pratense, Alchemilla vulgaris, Centaurea pseudophrygia, Stellaria graminea.

- •Group 4 (competitive mesotrophs) – with indicators such as Agrostis capillaris, Dactylis glomerata, Festuca pratensis, Phleum pratense, but also generalist species (Taraxacum officinale, Veronica chamaedrys).

2.4. The Impact of Management Scenarios on Diversity Indices

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Soil and Climatic Conditions

4.2. Experimental Design

- V1 - unfertilized (control);

- V2 – abandonment (unharvested or non-grazing);

- V3 – mulching (cut and leave the biomass on site);

- V4 - N50P50K50 kg/ha annually;

- V5 - N100P100K100 kg/ha annually;

- V6 - N150P150K150 kg/ha annually;

- V7 - 10 t/ha cattle manure, annually;

- V8 - 20 t/ha cattle manure, annually;

- V9 - 20 t/ha cattle manure, at 2 years;

- V10 - 30 t/ha cattle manure, annually;

- V11 - 30 t/ha cattle manure, at 2 years.

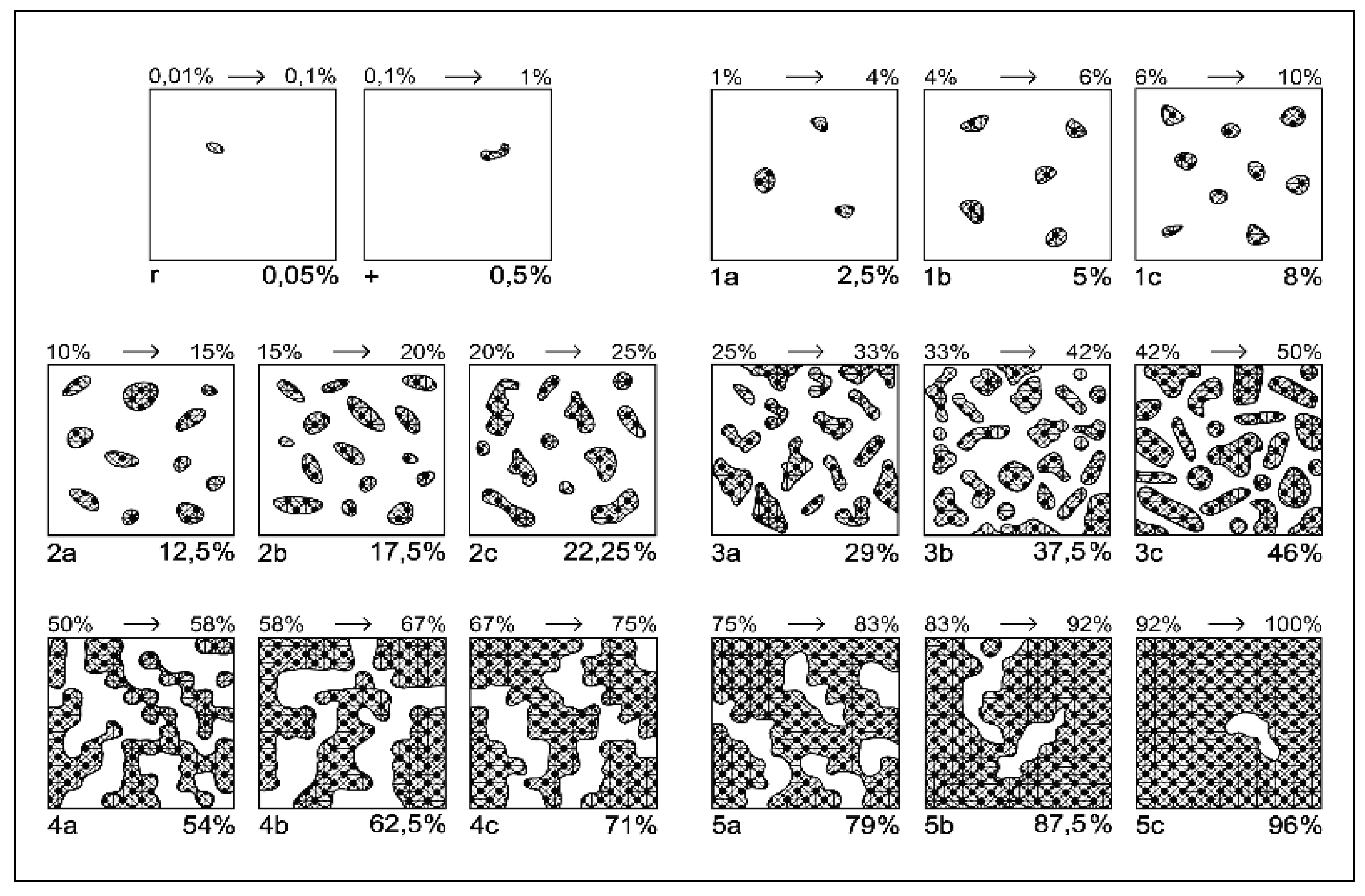

4.3. Vegetation Survey

4.4. Data Analysis

- Low-input: T4 (N50P50K50), T7 (10 t/ha cattle manure applied annually);

- Medium-input: T5 (N100P100K100), T8 (20 t/ha cattle manure applied annually), T9 (20 t/ha cattle manure once every two years), T11 (30 t/ha cattle manure once every two years);

- High-input: T6 (N150P150K150), T10 (30 t/ha cattle manure applied annually).

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buchmann, N.; Fuchs, K.; Feigenwinter, I.; Gilgen, A.K. Multifunctionality of Permanent Grasslands: Ecosystem Services and Resilience to Climate Change. In Grassland Science in Europe; European Grassland Federation; Zurich, Switzerland, 2019; Vol. 24, 19–26.

- Lomba, A.; McCracken, D.; Herzon, I. High Nature Value Farming Systems in Europe. Ecology and Society 2023, 1;28(2).

- Liu, S.; Ward, S.E.; Wilby, A.; Manning, P.; Gong, M.; Davies, J.; Killick, R.; Quinton, J.N.; Bardgett, R.D. Multiple Targeted Grassland Restoration Interventions Enhance Ecosystem Service Multifunctionality. Nature Communications 2025, 28;16(1):1-1.

- Marușca, T.; Păcurar, F.S.; Scrob, N.; Vaida, I.; Nicola, N.; Taulescu, E.; Dragoș, M.; Lukács, Z. Contributions to the Assessment of Grasslands Productivity of the Apuseni Natural Park (Rosci 0002. Romanian Journal of Grassland and Forage Crops 2021, 24.

- Michler, B.; Rotar, I.; Păcurar, F. Biodiversity and Conservation of Medicinal Plants: A Case Study in the Apuseni Mountains in Romania. Buletinul USAMV-CN 2006, 62, 86–87.

- Jakobsson, S.; Envall, I.; Bengtsson, J.; Rundlöf, M.; Svensson, M.; Åberg, C.; Lindborg, R. Effects on Biodiversity in Semi-Natural Pastures of Giving the Grazing Animals Access to Additional Nutrient Sources: A Systematic Review. Environmental Evidence 2024, 1;13(1):18.

- Sângeorzan, D.; Rotar, I.; Păcurar, F.; Vaida, I.; Suteu, A.; Deac, V. The definition of oligotrophic grasslands. Rom. J. Grassl. Forage Crops 2018, 2018.

- Vaida, I.; Păcurar, F.; Rotar, I.; Tomoş, L.; Stoian, V. Changes in Diversity Due to Long-Term Management in a High Natural Value Grassland. Plants 2021, 10, 739, doi:10.3390/plants10040739.

- Maruşca T, Păcurar FS, Taulescu E, Vaida I, Nicola N, Scrob N, Dragoș MM. Indicative species for the agrochemical properties of mountain grasslands soil from the apuseni natural park (rosci 0002). Romanian Journal of Grasslands and Forage Crops. 2022;31.

- Păcurar, F. Specii indicator pentru evaluarea şi elaborarea managementului sistemelor de pajişti cu înaltă valoare natu-rală-HNV. Casa Cărţii de Ştiinţă 2020.

- Diviaková, A.; Ollerová, H.; Stašiov, S.; Veverková, D.; Novikmec, M. Plant Functional Structure Varies across Different Management Regimes in Submontane Meadows. Nature Conservation 2024, 13;56, 181–200.

- Fernández-Guisuraga, J.M.; Fernández-García, V.; Tárrega, R.; Marcos, E.; Valbuena, L.; Pinto, R.; Monte, P.; Beltrán, D.; Huerta, S.; Calvo, L. Transhumant Sheep Grazing Enhances Ecosystem Multifunctionality in Productive Mountain Grasslands: A Case Study in the Cantabrian Mountains. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2022, 12;10, 861611.

- Gaga, I.; Rotar, I.; Păcurar, F.S.; Plesa, A.D.; Vaida, I. Study of Grassland Types from the Agricultural Research-Development Station (Ards) Turda. Romanian Journal of Grasslands and Forage Crops 2020, 21.

- Vaida, I.; Rotar, I.; Păcurar, F.; Vidican, R.; Pleşa, A.; Mălinaş, A.; Stoian, V. Impact on the Abandonment of Semi-Natural Grasslands from Apuseni Mountains. Bulletin of the University of Agricultural Sciences & Veterinary Medicine Cluj-Napoca. Agriculture 2016, 1;73(2.

- Păcurar, F.; Rotar, I.; Pleșa, A.; Balázsi, Á.; Vidican, R. Study of the Floristic Composition of Certain Secondary Grasslands in Different Successional Stages as a Result of Abandonment. Print ISSN 1843-5246; Elec-tronic ISSN 1843-5386, DOI 2015, 72, 11165.

- Reif, A.; Ruşdea, E.; Păcurar, F.; Rotar, I.; Brinkmann, K. A Traditional Cultural Landscape in Transformation. Mountain Research and Development 2008, 28, 18–22, doi:10.1659/mrd.0806.

- Rușdea, E.; Reif, A.; Höchtl, F.; Păcurar, F.; Rotar, I.; Stoie, A.; Dahlström, A.; Svensson, R.; Aronsson, M. Grassland Vegetation and Management-on the Interface between Science and Education. Bulletin of University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine Cluj-Napoca: Agriculture 2011, 68.

- Balazsi, A., Rotar I., Păcurar F., Vidican R., Pleșa A., Gliga A., Mălinaș A. Mulching and mulching with organic fertilizing as an alternative way to conserve the oligotrophy grasslands’ phytodiversity and maintain their productivity in Apuseni Mountains. Romanian Journal of Grasslands and Forage Crops 2014, 9, 7.

- Connell, J.H. Diversity in Tropical Rain Forests and Coral Reefs. Science 1978, 199, 1302–1310, doi:10.1126/science.199.4335.1302.

- Tilman, D. Secondary Succession and the Pattern of Plant Dominance along Experimental Nitrogen Gradients. Ecol. Monogr 1987, 57, 189–214, doi:10.2307/2937080.

- Biswas, M., SR; A.U. Disturbance Effects on Species Diversity and Functional Diversity in Riparian and Upland Plant Com-Munities. Ecology 2010, Jan;91(1):28-35.

- Zhang, C.; Xu, H.; Li, S. Revealing Ecotype Influences on Cistanche Sinensis Distribution and Diversity. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 10394521, doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.10394521.

- Păcurar, F.; Balázsi, Á.; Rotar, I.; Vaida, I.; Reif, A.; Vidican, R.; Ruşdea, E.; Stoian, V.; Sângeorzan, D. Technologies Used for Maintaining Oligotrophic Grasslands and Their Biodiversity in a Mountain Landscape. Romanian Biotechnological Letters 2018, 23, 13614–13623, doi:10.25083/rbl/23.3/13614.13623.

- Rotar, I.; Păcurar, F.; Vaida, I.; Nicola, N.; Pleșa, A. The Effect of Mulching on a Grasslands in the Apuseni Mountains. Romanian Journal of Grasslands and Forage Crops 2023, 28.

- Zarzycki, J.; Józefowska, A.; Kopeć, M. Can Mulching or Composting Be Applied to Maintain Semi-Natural Grassland Managed for Biodiversity? Journal for Nature Conservation 2024, 1;78, 126584.

- Vaida, I.; Rotar, I.; Păcurar, F. The Cumulative Effect of Manure on a Festuca Rubra Grasslands for 15 Years. Bulletin of the University of Agricultural Sciences & Veterinary Medicine Cluj-Napoca. Agriculture 2017, 1;74(2).

- Rotar, I.; Vaida, I.; Păcurar, F. Species with Indicative Values for the Management of the Mountain Grasslands. Romanian Agri-cultural Research 2020, 1.

- Samuil, C.; Vintu, S.C.; M, S. Influence of Fertilizers on the Biodiversity of Semi-natural Grassland in the Eastern Carpathians, Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca 2013, 41, 195–200.

- Samuil, C.; Vîntu, V.; Sîrbu, C.; Saghin, G.; Popovici, C. The Influence of Mineral and Organic Fertilization on Temporary Grasslands in North-Eastern Romania. Romanian Agricultural Research 2014, 31, 91–99.

- Vîntu V.; Samuil C.; Sirbu C.; Popovici C.I.; Stavarache M.; Sustainable Management of Nardus stricta L. Grasslands in Ro-mania’s Carpathians, Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca 2011, 39, 142–145.

- Corcoz, L.; Păcurar, F.; Pop-Moldovan, V.; Vaida, I.; Pleșa, A.; Stoian, V.; Vidican, R. Long-Term Fertilization Alters Mycorrhizal Colo-Nization Strategy in the Roots of Agrostis Capillaris. Agriculture 2022, 12;12(6):847.

- Stoian, V.; Vidican, R.; Păcurar, F.; Corcoz, L.; Pop-Moldovan, V.; Vaida, I.; Vâtcă, S.-D.; Stoian, V.A.; Plesa, A. Exploration of Soil Functional Microbiomes - A Concept Proposal for Long-Term Fertilized Grasslands. Plants 1253, 2022, 11, doi:10.3390/plants11091253.

- Mălinas, A.; Rotar, I.; Vidican, R.; Iuga, V.; Păcurar, F.; Mălinas, C.; Moldovan, C. Designing a Sustainable Temporary Grassland System by Monitoring Nitrogen Use Efficiency. Agronomy 2020, 19;10(1):149.

- Balazsi, A.; Păcurar, F.; Mihu-Pintilie, A.; Konold, W. How Do Public Institutions on Nature Conservation and Agriculture Contribute to the Conservation of Species-Rich Hay Meadows? International Journal of Conservation Science 2018, 9, 549–564.

- Sângeorzan, D.D.; Păcurar, F.; Reif, A.; Weinacker, H.; Ruşdea, E.; Vaida, I.; Rotar, I. Detection and Quantification of Arnica Montana L. Inflorescences in Grassland Ecosystems Using Convolutional Neural Networks and Drone-Based Remote Sensing. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, doi:10.3390/rs16112012.

- Janišová, M.; Škodová, I.; Magnes, M.; Iuga, A.; Biro, A.-S.; Ivașcu, C.M.; Ďuricová, V.; Buzhdygan, O.Y. Role of Livestock and Traditional Management Practices in Maintaining High Nature Value Grasslands. Biological Conservation 2025, 309, 111301.

- Hagemann, N.; Gerling, C.; Hölting, L.; Kernecker, M.; Markova-Nenova, N.N.; Wätzold, F.; Wendler, J.; Cord, A.F. Improving Re-Sult-Based Schemes for Nature Conservation in Agricultural Landscapes—Challenges and Best Practices from Selected European Countries. Regional Environmental Change 2025, Mar;25(1):12.

- Păcurar, F.; Reif, A.; Rusḑea, E. Conservation of Oligotrophic Grassland of High Nature Value (HNV) through Sustainable Use of Arnica Montana in the Apuseni Mountains, Romania. InMedicinal Agroecology 2023.

- Elliott, J.; Tindale, S.; Outhwaite, S.; Nicholson, F.; Newell-Price, P.; Sari, N.H.; Hunter, E.; Sánchez-Zamora, P.; Jin, S.; Gallardo-Cobos, R.; et al. European Permanent Grasslands: A Systematic Review of Economic Drivers of Change, Including a Detailed Analysis of the Czech Republic 2024, 21;13(1):116.

- Sattler, C.; Schrader, J.; Hüttner, M.L.; Henle, K. Effects of Management, Habitat and Landscape Characteristics on Biodiversity of Orchard Meadows in Central Europe: A Brief Review. Nature Conservation 2024, 28;55, 103–134.

- Rocha-Filho, L.C.; Santos, J.L.; Pereira, B.A. The Initial Impact of a Hydroelectric Reservoir on Tree Community Structure. Forests 2025, 16, 1236, doi:10.3390/f16081236.

- Gaga I.; Păcurar, F.; Vaida, I.; Plesa, A.; Rotar, I. Responses of Diversity and Productivity to Organo-Mineral Fertilizer Inputs in a High-Natural-Value Grassland, Transylvanian Plain, Romania. Plants 2022, 11, doi:10.3390/plants11151975.

- Shi, T.S.; Collins, S.L.; Yu, K.; Peñuelas, J.; Sardans, J.; Li, H.; Ye, J.S. A Global Meta-Analysis on the Effects of Organic and Inorganic Fertilization on Grasslands and Croplands. Nature Communications 2024, 22;15(1):3411.

- Titěra, J.; Pavlů, P., VV; L, H.; M, G.; J, S.; J. Response of Grassland Vegetation Composition to Different Fertilizer Treatments Recorded over Ten Years Following 64 Years of Fertilizer Applications in the Rengen Grassland Experiment. Applied Vegetation Science 2020, Jul;23(3):417-27.

- Melts, I.; Lanno, K.; Sammul, M.; Uchida, K.; Heinsoo, K.; Kull, T.; Laanisto, L. Fertilising Semi-Natural Grasslands May Cause Long-Term Negative Effects on Both Biodiversity and Ecosystem Stability. J. Appl. Ecol 2018, 55, 1851–1864, doi:10.1111/1365-2664.13129.

- Schaub, S.; Finger, R.; Leiber, F.; Probst, S.; Kreuzer, M.; Weigelt, A.; Buchmann, N.; Scherer-Lorenzen, M. Plant Diversity Effects on Forage Quality, Yield and Revenues of Semi-Natural Grasslands. Nature Communications 2020, 7;11(1):768.

- Hautier, Y.; Zhang, P.; Loreau, M.; Wilcox, K.R.; Seabloom, E.W.; Borer, E.T.; Byrnes, J.E.; Koerner, S.E.; Komatsu, K.J.; Lefcheck, J.S.; et al. General Destabilizing Effects of Eutrophication on Grassland Productivity at Multiple Spatial Scales. Nature Communications 2020, 23;11(1):5375.

- Dale, L.M.; Thewis, A.; Rotar, I.; Boudry, C.; Păcurar, F.S.; Lecler, B.; Agneessens, R.; Dardenne, P.; Baeten, V. Fertilization Effects on the Chemical Composition and in Vitro Organic Matter Digestibility of Semi-Natural Meadows as Predicted by NIR Spectrometry. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca 2013 b, 41, 58–64.

- Isselstein, J.; Jeangros, B.; Pavlu, V. Agronomic Aspects of Biodiversity Targeted Management of Temperate Grasslands in Europe–a Review. Agronomy research 2005, 3, 139–151.

- Samuil, C.; Stavarache, M.; Sirbu, C.; Vintu, V. Influence of sustainable fertilization on yield and quality food of Mountain Grassland. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca 2018, 46, 410–417.

- Rotar I, Păcurar F, Vidican R, Bogdan A. Impact of grassland management on occurrence of Arnica montana L. Grassland–a European Resource?. 2012 Aug 1:701.

- Wan, L.; LIU, G.; SU, X. Organic Fertilization Balances Biodiversity Maintenance, Grass Production, Soil Storage, Nutrient Cycling and Greenhouse Gas Emissions for Sustainable Grassland Development in China: A Meta-Analysis. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2025, 381, 109473.

- Rotar, I.; Păcurar, F.; Pleșa, A.; Balázsi, Á. Low mineral fertilization on grassland after 6 years. Lucrări Ştiinţifice 2015, 58, 2.

- Peppler-Lisbach, C.; Kratochwil, A.; Mazalla, L.; Rosenthal, G.; Schwabe, A.; Schwane, J.; Stanik, N. Synopsis of Nardus Grassland Resurveys Across Germany: Is Eutrophication Driven by a Recovery of Soil pH After Acidification? Journal of Vegetation Science 2025, May;36(3, 70040.

- Sherstiuk, M.; Skliar, V.; Kašpar, J.; Mohammadi, Z. Size and Vitality Characteristics of Bilberry (Vaccinium Myrtillus L.) Popula-Tions in the Central Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic: A Case Study of Non-Timber Forest Products. Global Ecology and Conservation 2024, 1;56, 03295.

- Hegland, S.J.; Gillespie, M.A. Vaccinium Dwarf Shrubs Responses to Experimental Warming and Herbivory Resistance Treatment Are Species-and Context Dependent. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2024, 13;12, 1347837.

- Dalle Fratte M, Cerabolini BE. Extending the Interpretation of Natura 2000 Habitat Types beyond Their Definition Can Bias Their Conservation Status Assessment: An Example with Species-Rich Nardus Grasslands (6230*. Ecological Indicators 2023, 1;156, 111113.

- Borawska-Jarmułowicz, B.; Mastalerczuk, G.; Janicka, M.; Wróbel, B. Effect of Silicon-Containing Fertilizers on the Nutritional Value of Grass–Legume Mixtures on Temporary Grasslands. Agriculture 2022, 21;12(2):145.

- Călina, J.; Călina, A.; Iancu, T.; Miluț, M.; Croitoru, A.C. Research on the Influence of Fertilization System on the Production and Sustainability of Temporary Grasslands from Romania. Agronomy 2022, 27;12(12):2979.

- Bobbink, R. Review and Revision of Empirical Critical Loads and Dose-Response Relationships. UNECE Workshop on the Review and Revision of Empirical Critical Loads and Dose-response Relationships. RIVM 2011.

- Nazare A.I., Stavarache M., Samuil C., Vîntu V. The Improvement of Nardus Stricta L. Permanent Meadow from the Dorna Depression through Mineral and Organic Fertilization. Scientific Papers. Series A. Agronomy 2024, 1;67(2.

- Zornić, V.; Petrović, M.; Babić, S.; Lazarević, Đ.; Đurović, V.; Sokolović, D.; Tomić, D. NPK fertilizer addition effect on „Nardus stricta” type grassland in kopaonik mountine. In Proceedings of the 1st International Symposium On Biotechnology, Proceedings, 2023.

- Păcurar, F.; Rotar, I.; Reif, A.; Vidican, R.; Stoian, V.; Gärtner, S.M.; Allen, R.B. Impact of Climate on Vegetation Change in a Mountain Grassland – Succession and Fluctuation. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca 2014, 42, 347–356, doi:10.15835/nbha4229578.

- Zhu, K.; Song, Y.; Lesage, J.C.; Luong, J.C.; Bartolome, J.W.; Chiariello, N.R.; Dudney, J.; Field, C.B.; Hallett, L.M.; Hammond, M.; et al. Rapid Shifts in Grassland Communities Driven by Climate Change. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2024, Dec;8(12):2252-64.

- Movedi, E.; Bocchi, S.; Paleari, L.; Vesely, F.M.; Vagge, I.; Confalonieri, R. Impacts of Climate Change on Semi-Natural Alpine Pastures Productivity and Floristic Composition. Regional Environmental Change 2023, Dec;23(4):159.

- Straffelini, E.; Luo, J.; Tarolli, P. Climate Change Is Threatening Mountain Grasslands and Their Cultural Ecosystem Services. Catena 2024, 30;237, 107802.

- Poláková J, Maroušková A, Holec J, Kolářová M, Janků J. Changes in grassland area in lowlands and marginal uplands: Medium-term differences and potential for carbon farming. Soil & Water Res. 2023;18, 245. 10.17221/65/2023.

- Hünig, C.; Benzler, A. The monitoring of agricultural land with high natural value in Germany., BfN - Skripten (Bundesamt für Naturschutz 2017, 196.

- Butz, R.J.; Dennis, A.; Millar, C.I.; Westfall, R.D. Global Observation Research Initiative in Alpine Environments (GLORIA): Results from Four Target Regions in California. InAGU fall meeting abstracts 2008, Dec, Vol. 2008, 21–0705.

- Socher, S.A.; Prati, D.; Boch, S.; Müller, J.; Baumbach, H.; Gockel, S.; Hemp, A.; Schöning, I.; Wells, K.; Buscot, F.; et al. Interacting Effects of Fertilization, Mowing and Grazing on Plant Species Diversity of 1500 Grasslands in Germany Differ between Regions. Basic and Applied Ecology 2013, 1;14(2):126-36.

- Dale, L.M.; Thewis, A.; Boudry, C.; Rotar, I.; Păcurar, F.S.; Abbas, O.; Dardenne, P.; Baeten, V.; Pfister, J.; Fernández Pierna, J.A. Discrimination of Grassland Species and Their Classification in Botanical Families by Laboratory Scale NIR Hyperspectral Imaging: Preliminary Results. Talanta 2013 a 116, 149–154, doi:10.1016/j.talanta.2013.05.006.

- Kagan, K.; Jonak, K.; Wolińska, A. The Impact of Reduced N Fertilization Rates According to the “Farm to Fork” Strategy on the Environment and Human Health. Applied Sciences 2024, 20;14(22):10726.

- Villa-Galaviz, E.; Smart, S.M.; Ward, S.E.; Fraser, M.D.; Memmott, J. Fertilization Using Manure Minimizes the Trade-Offs between Biodiversity and Forage Production in Agri-Environment Scheme Grasslands. Plos one 2023, 4;18(10):e0290843.

- Păcurar, F.; Rotar, I.; Morea, A.; Stoie, A.; Vaida, I. Management of High Nature Value Grasslands in the Apuseni Mountains. Romanian Biotechnological Letters 2012, 17, 7164–7174.

- Stănilă, A.L.; Dumitru, M. Soils Zones in Romania and Pedogenetic Processes. Agriculture and Agricultural Science Procedia 2016, 1;10, 135–139.

- Păcurar, F.; Rotar, I. Metode de Studiu Şi Interpretare a Vegetaţiei Pajiştilor 2014.

- Fartyal, A.; Chaturvedi, R.K.; Bargali, S.S.; Bargali, K. The Relationship between Phenological Characteristics and Life Forms within Temperate Semi-Natural Grassland Ecosystems in the Central Himalaya Region of India. Plants 2025, 7;14(6):835.

- Andreatta, D.; Bachofen, C.; Dalponte, M.; Klaus, V.H.; Buchmann, N. Extracting Flowering Phenology from Grassland Species Mixtures Using Time-Lapse Cameras. Remote Sensing of Environment 2023, 1;298, 113835.

- McCune, B.; Grace, J.B. Analysis of Ecological Communities; MjM Software Design: Gleneden Beach 2002.

- McCune B., Mefford M., P.C.-O.R.D. Multivariate Analysis of Ecological data. Versiunea 6. MjM Software 2011.

- Hao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Song, B. Assessing Biological Dissimilarities between Five Forest Plots in China Using Species Abun-Dance and Phylogenetic Information. Forest Ecosystems 2019, 6, 47, doi:10.1186/s40663-019-0188-9.

- Campos, R.; Fontana, V.; Losapio, G.; Moretti, M. How Cities Impact Diversity and Ecological Networks: A Functional and Phylogenetic Perspective. Urban Ecosystems 2024, doi:10.1007/s11252-024-01551-z.

- Li, X.; Pearson, D.E.; Ortega, Y.K.; Jiang, L.; Wang, S.; Gao, Q.; Wang, D.; Hautier, Y.; Zhong, Z. Nitrogen Inputs Suppress Plant Diversity by Overriding Consumer Control. Nature Communications 2025, 1;16(1):5855.

- Caldararu, S.; Rolo, V.; Stocker, B.D.; Gimeno, T.E.; Nair, R. Ideas and Perspectives: Beyond Model Evaluation–Combining Experi-Ments and Models to Advance Terrestrial Ecosystem Science. Biogeosciences Discussions 2023, 1–22.

- Sun, Y.; Tao, C.; Deng, X.; Liu, H.; Shen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, R.; Shen, Q.; Geisen, S. Organic Fertilization Enhances the Resistance and Resilience of Soil Microbial Communities under Extreme Drought. Journal of Advanced Research 2023, 1;47, 1–2.

- Jaunatre, R.; Buisson, E.; Leborgne, E.; Dutoit, T. Soil Fertility and Landscape Surrounding Former Arable Fields Drive the Ecological Resilience of Mediterranean Dry Grassland Plant Communities. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2023, 11.

- Manu, M.; Băncilă, R.I.; Onete, M. Soil Fauna-Indicators of Ungrazed Versus Grazed Grassland Ecosystems in Romania. Diversity 2025, 29;17(5):323.

- Peck, J. Multivariate Analysis for Community Ecologists: Stepby Step Using PC-ORD 2010.

- Dufrêne, M.; Legendre, P. Species Assemblages and Indicator Species: The Need for a Flexible Asymmetrical Approach. Ecol. Monogr 1997, 67, 345–366, doi:10.1890/0012-9615(1997)067.

- Yan, H.; Li, F.; Liu, G. Diminishing Influence of Negative Relationship between Species Richness and Evenness on the Modeling of Grassland α-Diversity Metrics. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2023, 3;11, 1108739.

- Sang, Y.; Gu, H.; Meng, Q.; Men, X.; Sheng, J.; Li, N.; Wang, Z. An Evaluation of the Performance of Remote Sensing Indices as an Indication of Spatial Variability and Vegetation Diversity in Alpine Grassland. Remote Sensing 2024, 18;16(24):4726.

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Oduor, A.M.; Kleunen, M.; Liu, Y. Diversity and Productivity of a Natural Grassland Decline with the Number of Global Change Factors. Journal of Plant Ecology 2025, 17, 112.

- Magurran, A.E. Measuring Biological Diversity; Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing, 2004; ISBN 978-0-632-05633-0.

| Experimental factors | Axis 1 (r) | Sig. | Axis 2 (r) | Sig. |

| No fertilization (T1–T3) | −0.825 | *** | 0.224 | ns |

| Fertilization – Low (T4, T7) | 0.352 | * | −0.315 | ns |

| Fertilization – Medium (T5, T8, T9, T11) | 0.586 | ** | 0.174 | ns |

| Fertilization – High (T6, T10) | 0.512 | ** | −0.241 | ns |

| Organic inputs (all levels) | 0.468 | ** | 0.112 | ns |

| Mineral inputs (all levels) | 0.455 | ** | −0.098 | ns |

| Axis importance | 87.5% | 11.1% | ns |

| Groups compared | T statistic | A (within-group agreement) | p-value |

| Group 1 vs. Group 2 | −15.43 | 0.513 | <0.001 |

| Group 1 vs. Group 3 | −15.75 | 0.689 | <0.001 |

| Group 1 vs. Group 4 | −12.95 | 0.723 | <0.001 |

| Group 2 vs. Group 3 | −15.69 | 0.535 | <0.001 |

| Group 2 vs. Group 4 | −12.95 | 0.623 | <0.001 |

| Group 3 vs. Group 4 | −12.87 | 0.519 | <0.001 |

| Species | Axis 1 (r) | Axis 1 (r-sq) | Axis 1 (tau) | Signif. | Axis 2 (r) | Axis 2 (r-sq) | Axis 2 (tau) | Signif. |

| Agrostis capillaris | 0.735 | 0.540 | 0.788 | *** | 0.635 | 0.403 | -0.006 | ns |

| Anthoxanthum odoratum | 0.163 | 0.026 | 0.171 | ns | -0.368 | 0.136 | -0.270 | * |

| Briza media | -0.423 | 0.179 | -0.410 | * | -0.488 | 0.238 | -0.319 | ** |

| Cynosurus cristatus | 0.761 | 0.579 | 0.699 | *** | 0.227 | 0.052 | -0.127 | ns |

| Dactylis glomerata | 0.859 | 0.737 | 0.646 | *** | 0.186 | 0.035 | 0.053 | ns |

| Festuca pratensis | 0.819 | 0.670 | 0.732 | *** | 0.301 | 0.090 | 0.043 | ns |

| Festuca rubra | 0.768 | 0.591 | 0.567 | *** | -0.494 | 0.244 | -0.309 | * |

| Nardus stricta | -0.987 | 0.974 | -0.906 | *** | 0.083 | 0.007 | 0.107 | ns |

| Phleum pratense | 0.845 | 0.714 | 0.754 | *** | 0.262 | 0.069 | -0.050 | ns |

| Trifolium pratense | 0.544 | 0.296 | 0.356 | ** | -0.762 | 0.581 | -0.565 | *** |

| Trifolium repens | 0.144 | 0.021 | 0.095 | ns | -0.719 | 0.517 | -0.522 | *** |

| Luzula multiflora | -0.525 | 0.275 | -0.451 | ** | -0.426 | 0.181 | -0.287 | * |

| Potentilla erecta | -0.634 | 0.402 | -0.506 | *** | -0.328 | 0.108 | -0.176 | ns |

| Veronica chamaedrys | 0.137 | 0.019 | 0.093 | ns | -0.465 | 0.216 | -0.433 | * |

| Vaccinium myrtillus | -0.848 | 0.719 | -0.654 | *** | 0.037 | 0.001 | 0.170 | ns |

| Carex pallescens | -0.452 | 0.204 | -0.387 | * | -0.312 | 0.097 | -0.243 | ns |

| Ranunculus acris | 0.236 | 0.056 | 0.139 | ns | -0.268 | 0.072 | -0.201 | ns |

| Rumex acetosella | 0.718 | 0.515 | -0.535 | *** | 0.059 | 0.003 | 0.010 | ns |

| Stellaria graminea | -0.023 | 0.001 | 0.025 | ns | -0.240 | 0.057 | 0.205 | ns |

| Taraxacum officinale | 0.702 | 0.493 | -0.554 | *** | -0.258 | 0.066 | 0.194 | ns |

| Species | Group | IndVal | Signif. |

| Agrostis capillaris | 4 | 66.7 | p < 0.001 |

| Anthoxanthum odoratum | 2 | 50.2 | p < 0.001 |

| Briza media | 2 | 45.2 | p < 0.001 |

| Cynosurus cristatus | 4 | 46.6 | p < 0.001 |

| Dactylis glomerata | 4 | 42.4 | p < 0.001 |

| Deschampsia caespitosa | 3 | 27.8 | ns |

| Festuca pratensis | 4 | 46.7 | p < 0.001 |

| Festuca rubra | 3 | 52.3 | p < 0.001 |

| Holcus lanatus | 3 | 54.9 | p < 0.001 |

| Nardus stricta | 1 | 50.4 | p < 0.001 |

| Phleum pratense | 4 | 48.1 | p < 0.001 |

| Lotus corniculatus | 2 | 36.2 | p < 0.05 |

| Trifolium ochroleucon | 2 | 60.0 | p < 0.001 |

| Trifolium pratense | 3 | 46.8 | p < 0.001 |

| Trifolium repens | 2 | 46.7 | p < 0.001 |

| Achillea stricta | 2 | 55.1 | p < 0.001 |

| Alchemilla vulgaris | 3 | 38.2 | p < 0.05 |

| Leucanthemum vulgare | 2 | 38.8 | p < 0.01 |

| Carex pubescens | 2 | 52.2 | p < 0.001 |

| Campanula serata | 2 | 35.3 | p < 0.05 |

| Campanula abietina | 1 | 41.7 | p < 0.001 |

| Cerastium sylvaticum | 1 | 35.9 | p < 0.001 |

| Cruciata glabra | 1 | 42.9 | p < 0.001 |

| Luzula multiflora | 2 | 48.3 | p < 0.001 |

| Hyeracium pilosela | 2 | 43.5 | p < 0.01 |

| Hypericum maculatum | 2 | 51.7 | p < 0.001 |

| Prunela vulgaris | 2 | 45.2 | p < 0.01 |

| Polygala vulgaris | 1 | 52.4 | p < 0.001 |

| Plantago lanceolata | 2 | 35.4 | ns |

| Potentila erecta | 2 | 62.9 | p < 0.001 |

| Ranunculas acris | 3 | 27.9 | ns |

| Stellaria gramineae | 3 | 42.0 | p < 0.05 |

| Taraxacum officinale | 4 | 34.8 | ns |

| Thymus pullegioides | 2 | 56.3 | p < 0.001 |

| Viola declinata | 1 | 53.8 | p < 0.001 |

| Veronica officinalis | 1 | 52.0 | p < 0.001 |

| Veronica chamaedrys | 2 | 37.0 | ns |

| Vaccinium myrtillus | 1 | 61.9 | p < 0.001 |

| Treatment |

Species richness (S) |

Shannon index (H’) | Evenness (E) | Simpson (D) |

| T1 | 35.50 ± 0.50 a | 1.54 ± 0.02 e | 0.43 ± 0.01 d | 0.51 ± 0.01 d |

| T2 | 31.25 ± 0.48 b | 1.30 ± 0.04 f | 0.38 ± 0.01 d | 0.42 ± 0.02 d |

| T3 | 35.00 ± 0.00 a | 1.79 ± 0.05 d | 0.50 ± 0.02 c | 0.58 ± 0.02 c |

| T4 | 37.00 ± 0.00 a | 2.59 ± 0.04 a | 0.72 ± 0.01 a | 0.84 ± 0.01 a |

| T5 | 27.50 ± 1.55 c | 2.37 ± 0.04 b | 0.72 ± 0.01 a | 0.84 ± 0.01 a |

| T6 | 22.50 ± 0.65 d | 2.15 ± 0.01 c | 0.69 ± 0.01 ab | 0.80 ± 0.00 b |

| T7 | 38.00 ± 0.00 a | 2.54 ± 0.05 a | 0.70 ± 0.01 ab | 0.83 ± 0.01 a |

| T8 | 28.25 ± 1.11 c | 2.49 ± 0.04 a | 0.75 ± 0.01 a | 0.86 ± 0.01 a |

| T9 | 37.00 ± 0.00 a | 2.62 ± 0.01 a | 0.73 ± 0.00 a | 0.85 ± 0.00 a |

| T10 | 22.75 ± 0.48 d | 2.24 ± 0.02 bc | 0.72 ± 0.00 a | 0.83 ± 0.00 a |

| T11 | 28.00 ± 1.47 c | 2.5 ± 0.05 a | 0.75 ± 0.016 a | 0.86 ± 0.01 a |

| F test | 51.72 (df=10,33) | 156.03 (df=10,33) | 160.32 (df=10,33) | 267.54 (df=10,33) |

| p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Class |

Coverage Interaval (%) |

Class Central Value (%) |

Sub-Note | Sub-Interval (%) | Central-Adjusted Value of Sub-Interval (%) |

| 5 | 75–100 | 87.5 | 5c | 92–100 | 96 |

| 5b | 83–92 | 87.5 | |||

| 5a | 75–83 | 79 | |||

| 4 | 50–75 | 62.5 | 4c | 67–75 | 71 |

| 4b | 58–67 | 62.5 | |||

| 4a | 50–58 | 54 | |||

| 3 | 25–50 | 37.5 | 3c | 42–50 | 46 |

| 3b | 33–42 | 37.5 | |||

| 3a | 25–33 | 29 | |||

| 2 | 10–25 | 17.5 | 2c | 20–25 | 22.25 |

| 2b | 15–20 | 17.5 | |||

| 2a | 10–15 | 12.5 | |||

| 1 | 1–10 | 5 | 1c | 6–10 | 8 |

| 1b | 4–6 | 5 | |||

| 1a | 1–4 | 2.5 | |||

| + | 0.1–1 | 0.5 | - | - | 0.5 |

| r | 0.01–0.1 | 0.05 | - | - | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).