Submitted:

27 September 2025

Posted:

29 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

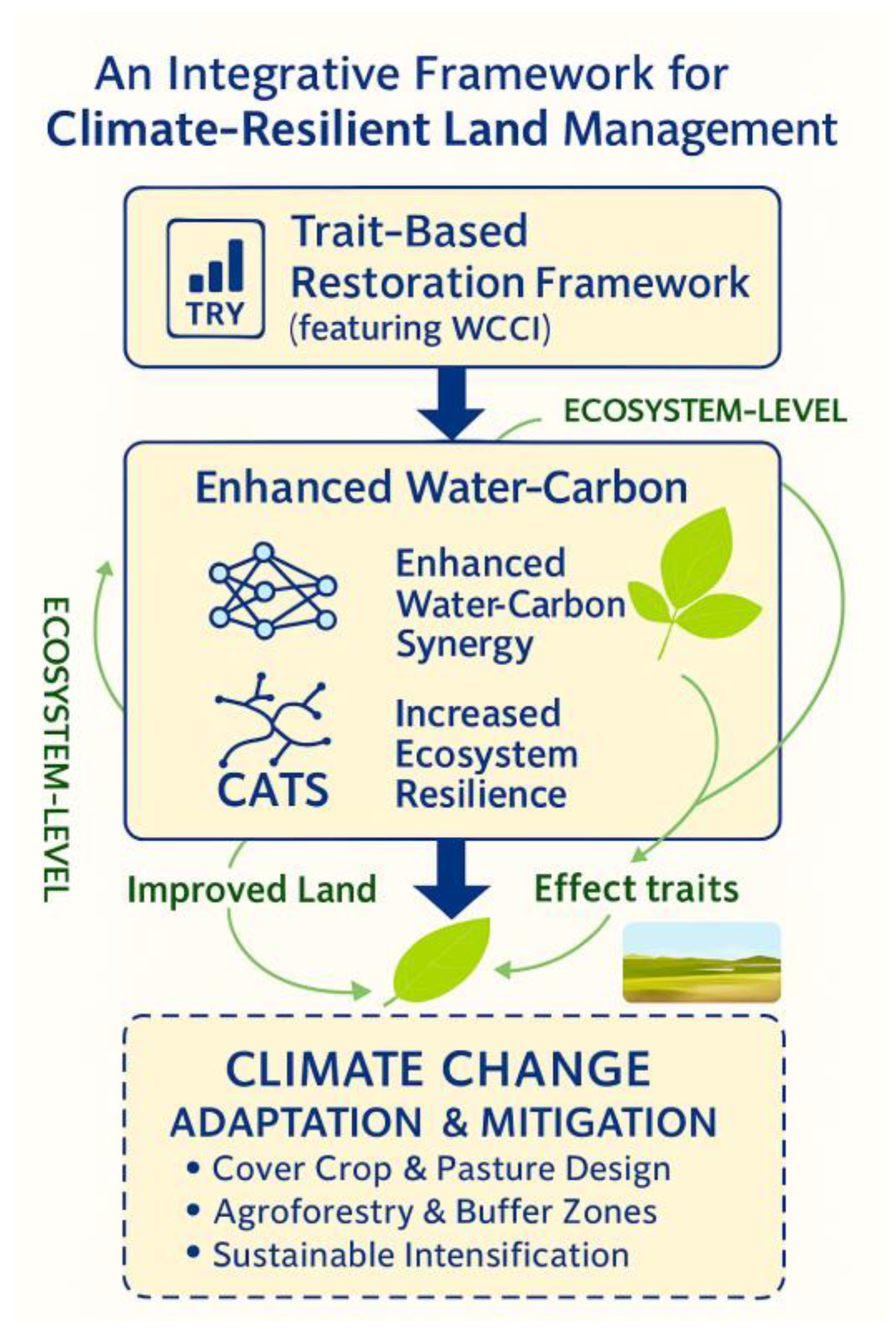

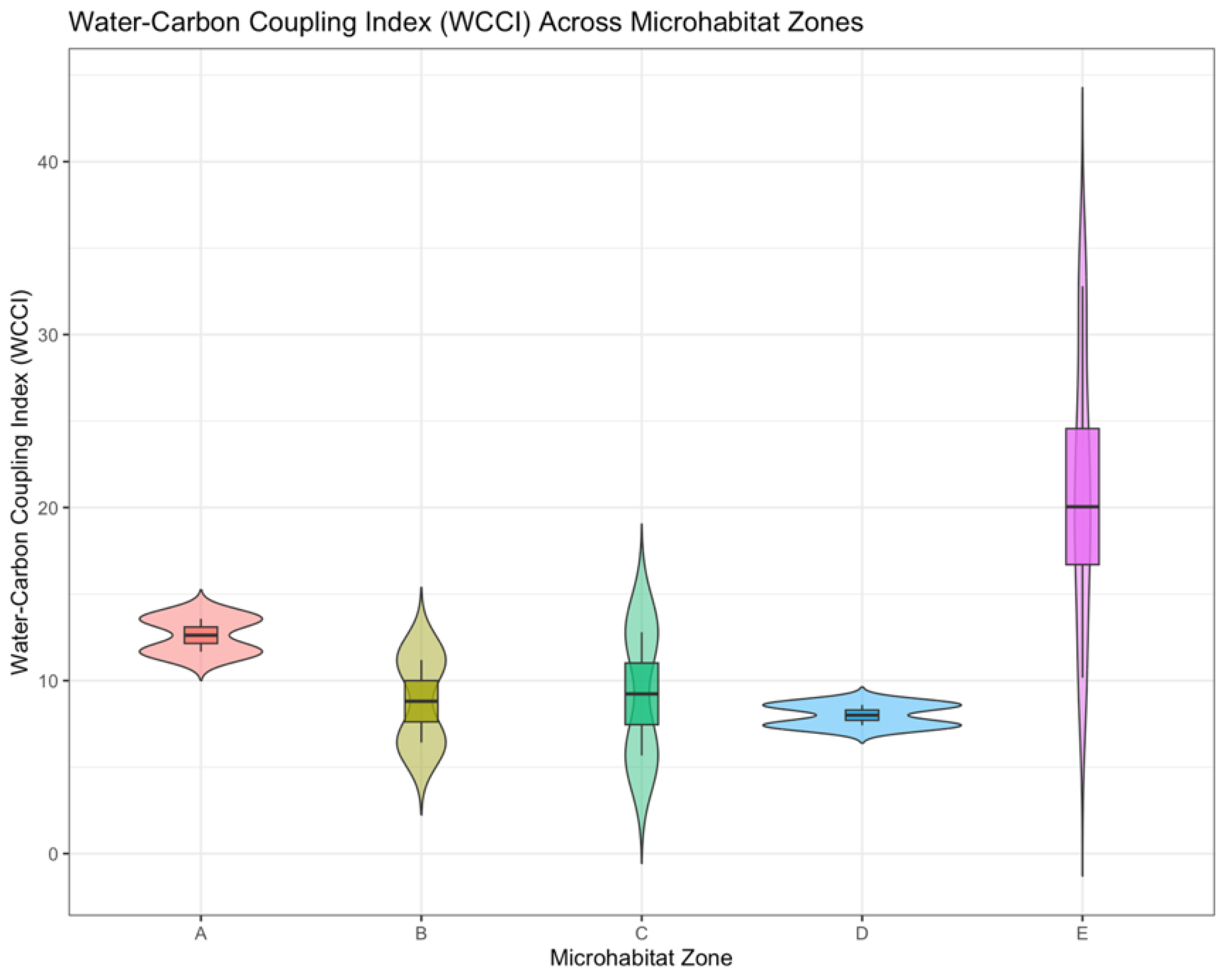

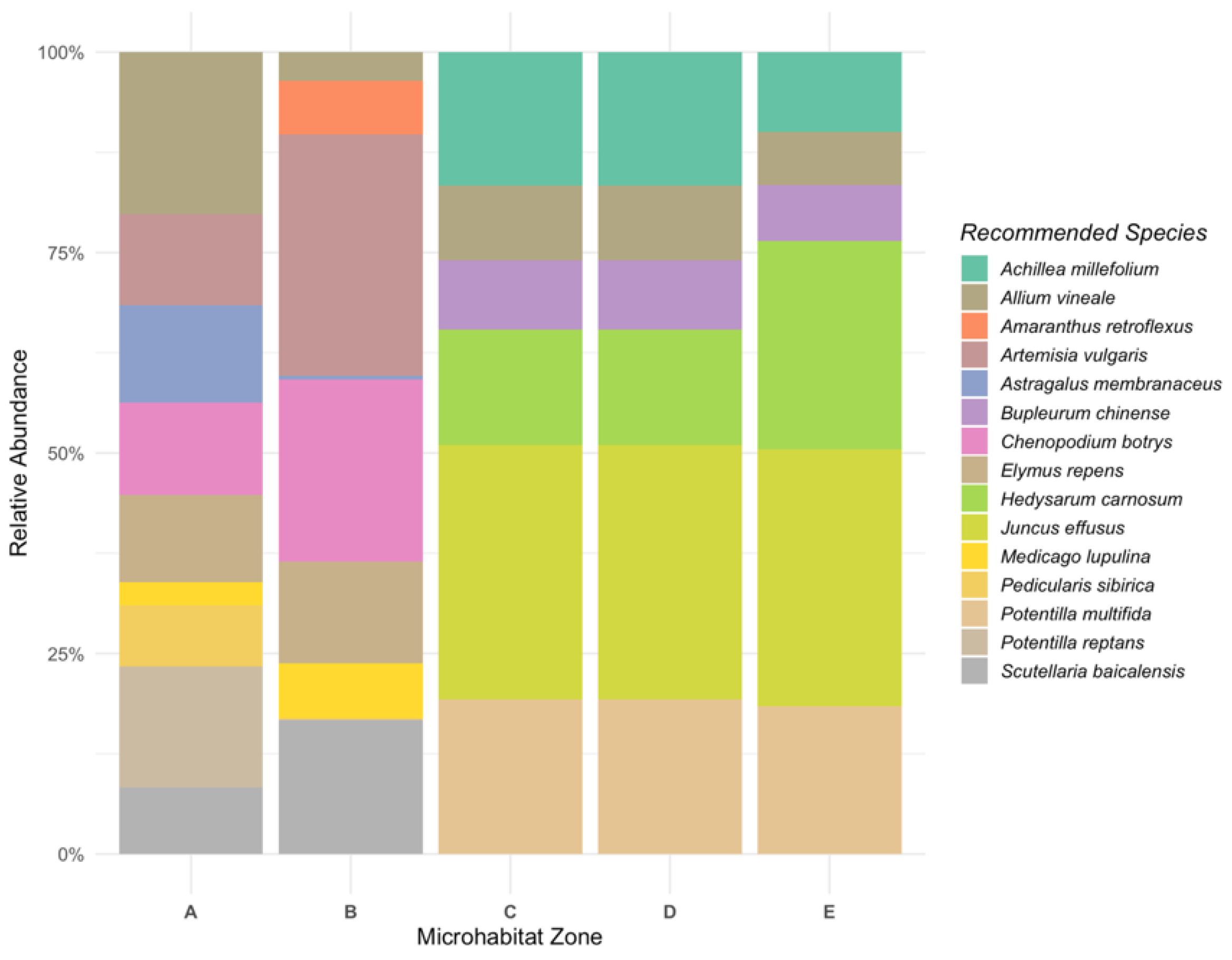

Ecological restoration in degraded landscapes requires a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing ecosystem function, particularly in relation to water and carbon cycling. This study explores the role of microtopography and plant functional traits in optimizing water-carbon coupling efficiency in a mining-affected ecosystem using the CATS model. We assessed the water-carbon coupling index (WCCI) across five microhabitat zones (A–E) within a mining area in the Hulunbuir Grassland. Results show significant variability in WCCI across zones, with Zone B exhibiting the highest functional efficiency due to its moderate moisture and low erosion, while Zone A displayed the lowest WCCI, constrained by water and nutrient limitations. The CATS model simulations revealed that water-carbon coupling is highly influenced by species functional traits such as SLA, height, and drought tolerance, with species like polygonum aviculare and cleistogenes caespitosa contributing most significantly to functional performance. Additionally, ecological filters, such as soil moisture, nutrient availability, and erosion intensity, were found to shape species selection and community structure. Our findings highlight the importance of trait-based approaches in restoration, emphasizing the need for tailored species optimization that accounts for both functional trait diversity and local environmental conditions. This research offers valuable insights for improving ecosystem resilience and optimizing water-carbon coupling in the face of climate change and land degradation.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

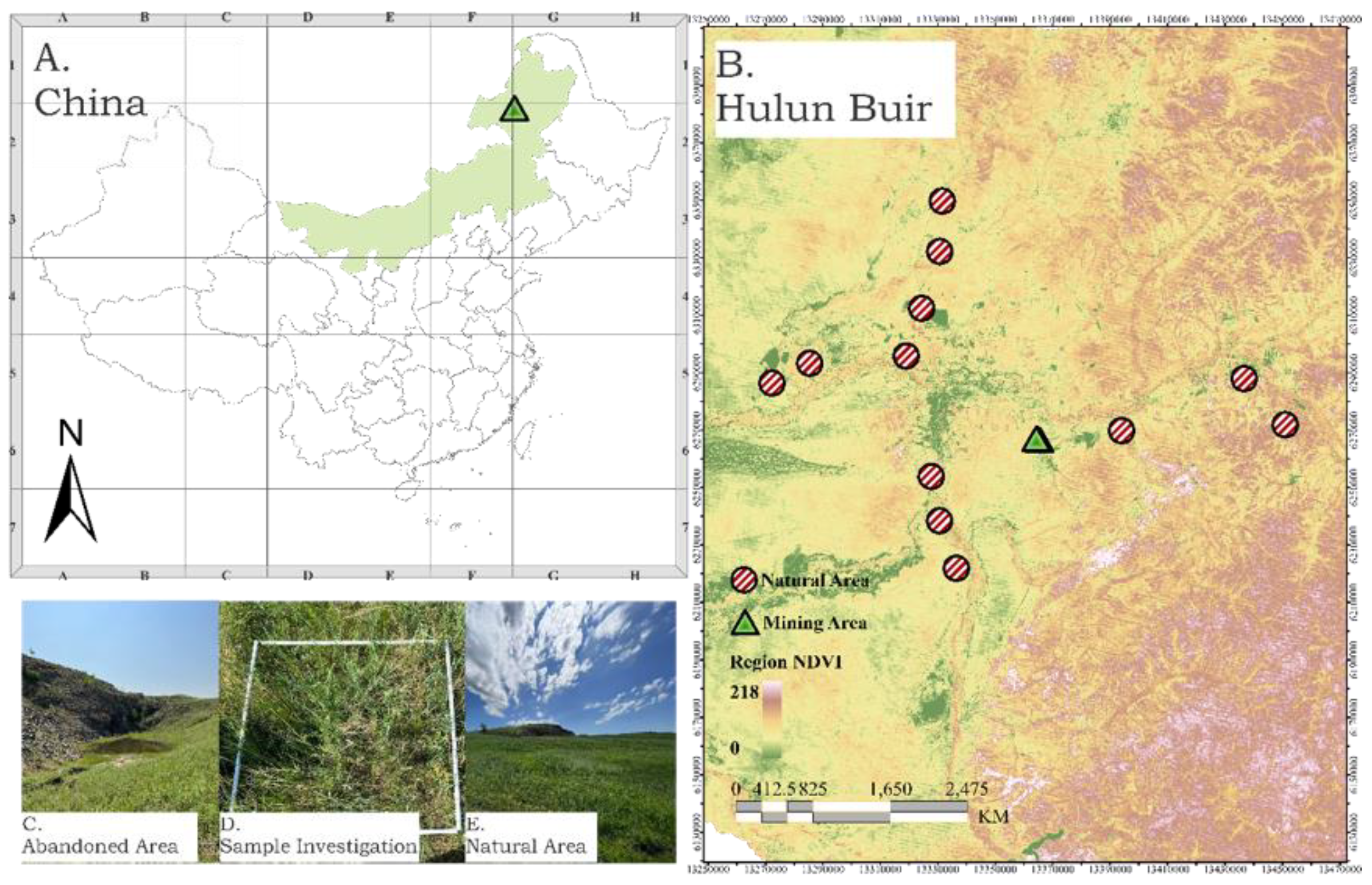

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling Design

2.3. Vegetation and Soil Data Collection

2.4. Trait-Environment Coupling Analysis

2.4.1. Community-Weighted Mean (CWM) Calculation[62]

2.4.2. Trait-Environment Correlation

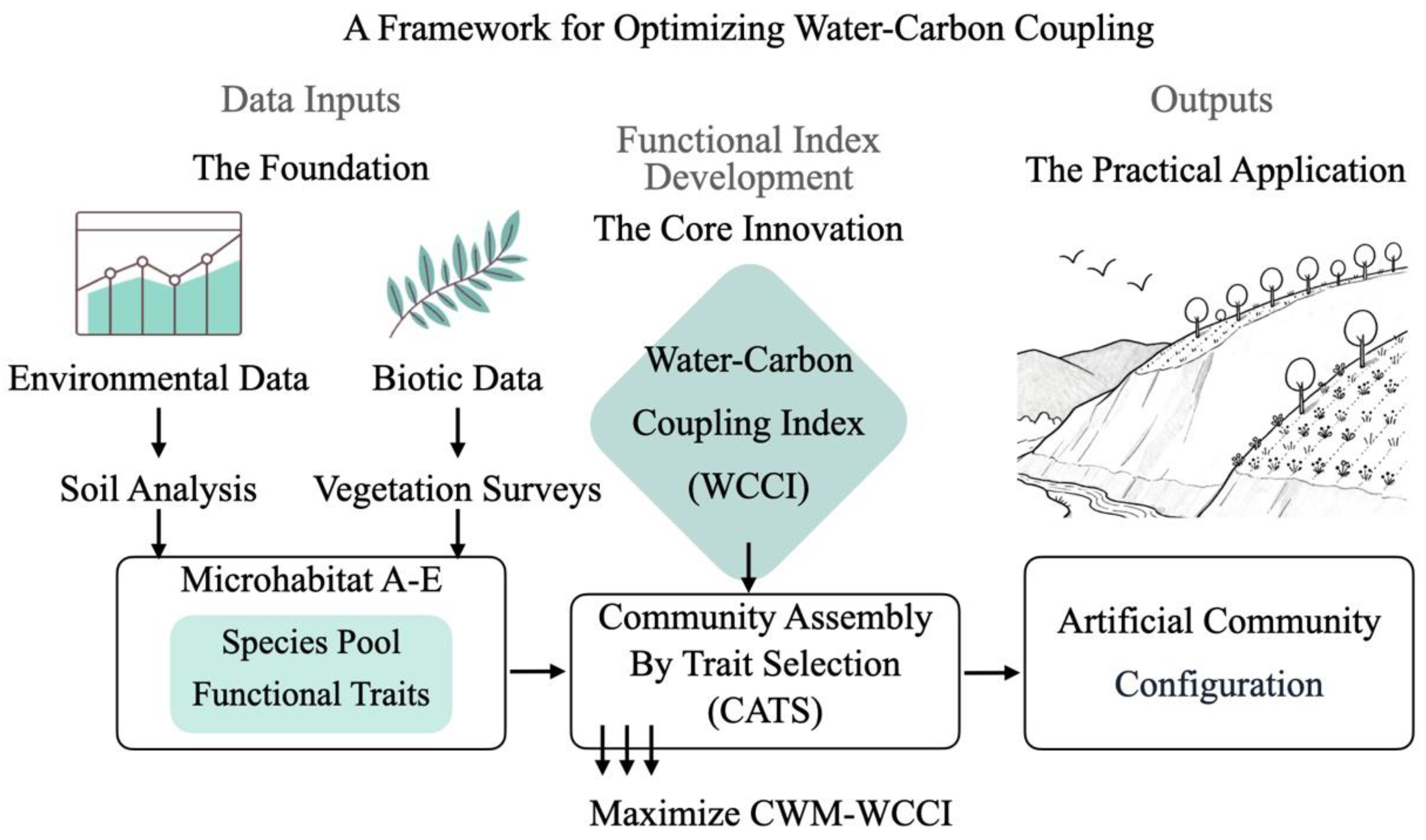

2.5. A Framework for Optimizing Water-Carbon Coupling

2.5.1. Calculation of the Water-Carbon Coupling Index (WCCI)

- (1)

- Trait Aggregation: For each of the 86 species, the average value for H, FC, and SLA was calculated from field measurements.

- (2)

- Proxy Normalization: Each of the three proxy traits (H, FC, and 1/SLA) was independently normalized to a scale of 0 to 1 across all species using min-max scaling:

- (3)

- Component Score Calculation: A Water Score and a Carbon Score were calculated for each species by summing the normalized values of their respective proxy traits.

- (4)

- Final Index Formulation: The resulting were themselves normalized to a 0–1 scale. The final WCCI was then calculated as the equally weighted average of these two component scores, as shown in Equation 2, with α set to 0.5.

2.5.2. Trait-Based Species Optimization with CATS

- (1)

- Trait Filtering: The first phase involved applying environmental constraints (e.g., SWC, SOM) to identify species whose traits align with the restoration site’s conditions. This process used random forest regression models to predict trait values and optimize the species pool.

- (2)

- Species Optimization: In the second phase, species abundance was optimized under the water-carbon coupling framework. Species in each microhabitat (A–E) were selected based on their ability to enhance water retention and carbon sequestration. Species were ranked by their ability to meet both the water and carbon targets, and a final species pool was selected for each microhabitat.

2.5.3. Microhabitat-Specific Optimization

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Sensitivity and Uncertainty Analysis

3. Results

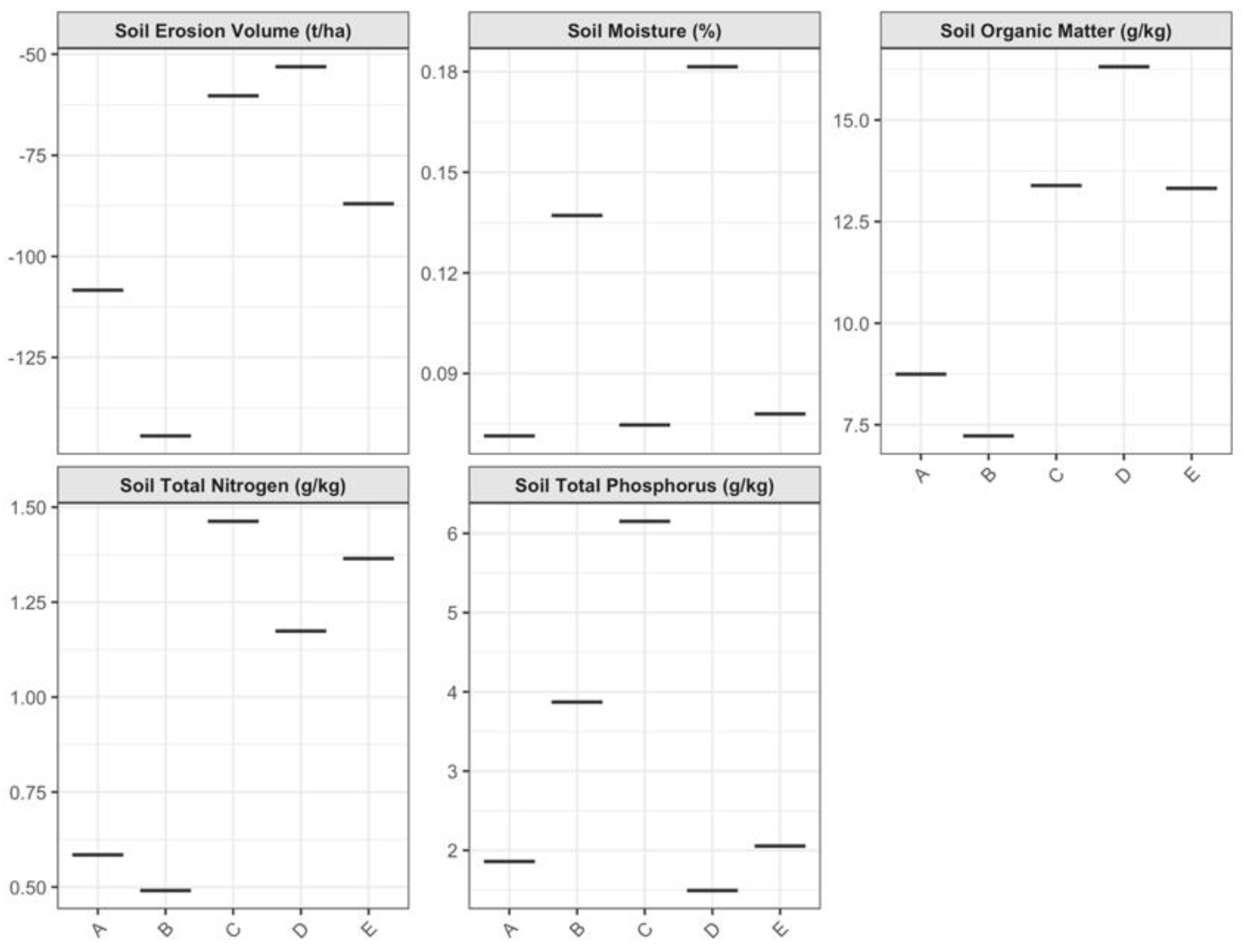

3.1. Significant Environmental Heterogeneity and Microhabitat Stratification

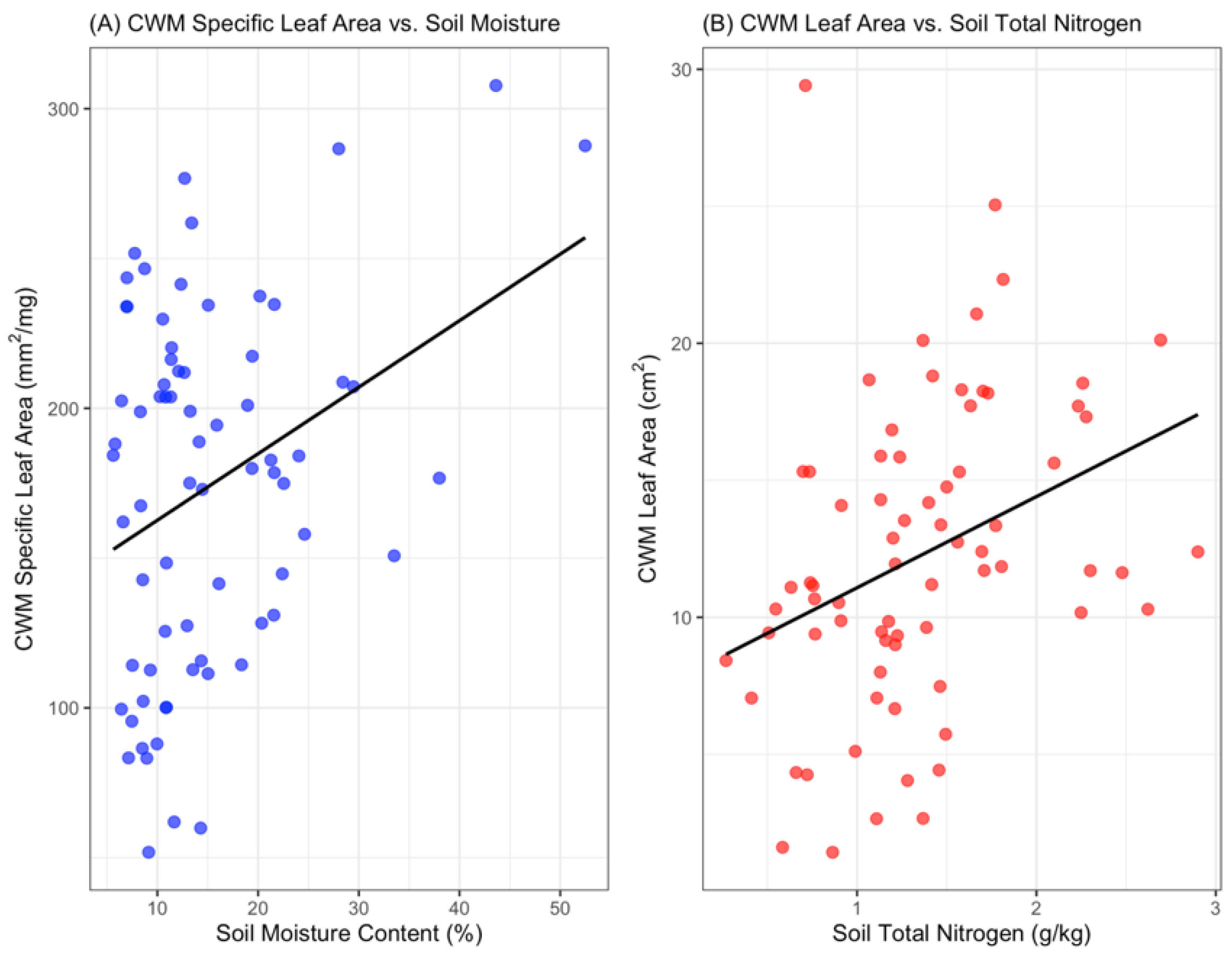

3.2. Strong Evidence of Trait-Based Environmental Filtering in Plant Communities

3.3. CATS-Based Simulations and Functional Trade-Offs Across Microhabitats

3.4. Optimized and Zone-Specific Community Assemblages for Functional Restoration

4. Discussion

4.1. An Innovative Framework for Optimizing Biogeochemical Function

4.2. The Mechanisms of Functional Optimization: Filters, Keystones, and Soil Feedbacks

4.3. Practical Implications: From Precision Restoration to Sustainable Agronomy

- i.

- Cover crop design: selecting species mixtures that simultaneously build soil organic carbon and reduce evaporation losses during fallow periods.

- ii.

- Pasture revitalization: identifying grass–forb combinations that increase forage productivity while enhancing drought resilience.

- iii.

- Buffer zone management: deploying species with high WCCI to improve water retention and erosion control in agroforestry or watershed protection schemes.

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Zhou, G.; Eisenhauer, N.; Terrer, C.; Eldridge, D.J.; Duan, H.; Guirado, E.; Berdugo, M.; Zhou, L.; Liu, S.; Zhou, X.; et al. Resistance of Ecosystem Services to Global Change Weakened by Increasing Number of Environmental Stressors. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 882–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, C.; Overpeck, J.T.; Allen, J.R.M.; Anderson, P.M.; Betancourt, J.L.; Binney, H.A.; Brewer, S.; Bush, M.B.; Chase, B.M.; Cheddadi, R.; et al. Past and Future Global Transformation of Terrestrial Ecosystems under Climate Change. Science 2018, 361, 920–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Khan, U.; Adnan, M.; Younas, W.; Qureshi, N.B.; Yasir, Q.M.; Cai, Q.; Chiu, M.-C. Global Decline of Aquatic and Terrestrial Insects Driven by Climate Change and Anthropogenic Impacts: The Interaction of Multiple Stressors and Disruption of Niche Conservatism. Biological Conservation 2025, 308, 111181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholes, R.; Montanarella, L.; Brainich, A.; Barger, N.; Brink, B.; Cantele, M.; Erasmus, B.; Fisher, J.; Gardner, T.; Holland, T.; et al. IPBES (2018): Summary for Policymakers of the Assessment Report on Land Degradation and Restoration of the Intergovernmental SciencePolicy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. In; 2018.

- Prăvălie, R.; Patriche, C.; Borrelli, P.; Panagos, P.; Roșca, B.; Dumitraşcu, M.; Nita, I.-A.; Săvulescu, I.; Birsan, M.-V.; Bandoc, G. Arable Lands under the Pressure of Multiple Land Degradation Processes. A Global Perspective. Environmental Research 2021, 194, 110697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Krupnik, T.J.; Timsina, J.; Mahboob, M.G.; Chaki, A.K.; Farooq, M.; Bhatt, R.; Fahad, S.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Agricultural Land Degradation: Processes and Problems Undermining Future Food Security. In Environment, Climate, Plant and Vegetation Growth; Fahad, S., Hasanuzzaman, M., Alam, M., Ullah, H., Saeed, M., Ali Khan, I., Adnan, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 17–61. ISBN 978-3-030-49731-6. [Google Scholar]

- Habibullah, M.S.; Din, B.H.; Tan, S.-H.; Zahid, H. Impact of Climate Change on Biodiversity Loss: Global Evidence. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2022, 29, 1073–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleespies, M.W.; Hahn-Klimroth, M.; Dierkes, P.W. Perceptions of Biodiversity Loss among Future Decision-Makers in 37 Countries. npj biodivers 2024, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Huang, J.; Zhang, G.; Han, D.; Ding, L.; Wei, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, C.; Yu, H. Abrupt Loss of Species Richness Caused by Ecosystem Transition. Science Bulletin 2025, 70, 1523–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Liu, Y.; Meadows, M.E. Ecological Restoration for Sustainable Development in China. National Science Review 2023, 10, nwad033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gann, G. The Language(s) of Ecological Restoration. Ecological Restoration 2009, 27, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, K.N.; Bauhus, J. Drivers of Native Species Regeneration in the Process of Restoring Natural Forests from Mono--specific, Even--aged Tree Plantations: A Quantitative Review. Restoration Ecology 2020, 28, 1074–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Ji, C.; Yang, J.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; Fu, L.; Liu, Q. The Advantage of Afforestation Using Native Tree Species to Enhance Soil Quality in Degraded Forest Ecosystems. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 20022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.; Jalonen, R.; Loo, J.; Boshier, D.; Gallo, L.; Cavers, S.; Bordács, S.; Smith, P.; Bozzano, M. Genetic Considerations in Ecosystem Restoration Using Native Tree Species. Forest Ecology and Management 2014, 333, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Mateos, D.; Alberdi, A.; Morriën, E.; Van Der Putten, W.H.; Rodríguez-Uña, A.; Montoya, D. The Long-Term Restoration of Ecosystem Complexity. Nat Ecol Evol 2020, 4, 676–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, N.; Mantuano, D.; Manhães, A.; Sansevero, J. Use of the Trait-Based Approach in Ecological Restoration Studies: A Global Review. Trees 2023, 37, 1287–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burylo, M.; Rey, F.; Mathys, N.; Dutoit, T. Plant Root Traits Affecting the Resistance of Soils to Concentrated Flow Erosion. Earth Surf Processes Landf 2012, 37, 1463–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brudvig, L.A. The Restoration of Biodiversity: Where Has Research Been and Where Does It Need to Go? American J of Botany 2011, 98, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancalion, P.H.S.; Niamir, A.; Broadbent, E.; Crouzeilles, R.; Barros, F.S.M.; Almeyda Zambrano, A.M.; Baccini, A.; Aronson, J.; Goetz, S.; Reid, J.L.; et al. Global Restoration Opportunities in Tropical Rainforest Landscapes. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Box, E.O. Plant Functional Types and Climate at the Global Scale. J Vegetation Science 1996, 7, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubin, I.; Munson, A.D.; Cardou, F.; Burton, P.J.; Isabel, N.; Pedlar, J.H.; Paquette, A.; Taylor, A.R.; Delagrange, S.; Kebli, H.; et al. Traits to Stay, Traits to Move: A Review of Functional Traits to Assess Sensitivity and Adaptive Capacity of Temperate and Boreal Trees to Climate Change. Environ. Rev. 2016, 24, 164–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklas, K.J.; Shi, P.; Gielis, J.; Schrader, J.; Niinemets, Ü. Editorial: Leaf Functional Traits: Ecological and Evolutionary Implications. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1169558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Deng, S.; Bai, Y.; Wu, Z.; Luo, J. Leaf Functional Traits and Their Influencing Factors in Six Typical Vegetation Communities. Plants 2024, 13, 2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, M.; Arunachalam, K.; Arunachalam, A.; Alatalo, J.M.; Pandey, R. Assessment of Leaf Morphological, Physiological, Chemical and Stoichiometry Functional Traits for Understanding the Functioning of Himalayan Temperate Forest Ecosystem. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 23807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yin, D.; He, P.; Cadotte, M.W.; Ye, Q. Linking Plant Functional Traits to Biodiversity under Environmental Change. Biological Diversity 2024, 1, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, N.; Bagousse-Pinguet, Y.L.; Liancourt, P.; Berdugo, M.; Gotelli, N.J.; Maestre, F.T. Functional Trait Diversity Maximizes Ecosystem Multifunctionality. Nat Ecol Evol 2017, 1, 0132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laughlin, D.C.; Strahan, R.T.; Huffman, D.W.; Sánchez Meador, A.J. Using Trait--based Ecology to Restore Resilient Ecosystems: Historical Conditions and the Future of Montane Forests in Western North America. Restoration Ecology 2017, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, D.C.; Laughlin, D.E. Advances in Modeling Trait-Based Plant Community Assembly. Trends in Plant Science 2013, 18, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, D.C.; Joshi, C.; Van Bodegom, P.M.; Bastow, Z.A.; Fulé, P.Z. A Predictive Model of Community Assembly That Incorporates Intraspecific Trait Variation. Ecology Letters 2012, 15, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laughlin, D.C. Applying Trait-Based Models to Achieve Functional Targets for Theory-Driven Ecological Restoration. Ecol Lett 2014, 17, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caners, R.T.; Lieffers, V.J. Divergent Pathways of Successional Recovery for In Situ Oil Sands Exploration Drilling Pads on Wooded Moderate--Rich Fens in Alberta, Canada. Restoration Ecology 2014, 22, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holyoak, M.; Caspi, T.; Redosh, L.W. Integrating Disturbance, Seasonality, Multi-Year Temporal Dynamics, and Dormancy Into the Dynamics and Conservation of Metacommunities. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8, 571130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, J.D.; Price, J.N.; Henning, J.A.; Batzer, E.E.; Ohlert, T.J.; Wainwright, C.E.; Adler, P.B.; Alberti, J.; Arnillas, C.A.; Biederman, L.A.; et al. Compositional Variation in Grassland Plant Communities. Ecosphere 2023, 14, e4542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.B.; Wang, T.; Maslov, S. Functional Convergence in Slow-Growing Microbial Communities Arises from Thermodynamic Constraints. The ISME Journal 2023, 17, 1482–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, P.; He, N.; Yu, K.; Xu, L.; Van Meerbeek, K. Integrating Multiple Plant Functional Traits to Predict Ecosystem Productivity. Commun Biol 2023, 6, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, J.I.; An, R.; Kraft, N.J.B.; Pacala, S.W.; Levine, J.M. Why Ecologists Struggle to Predict Coexistence from Functional Traits. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2025, 40, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zirbel, C.R.; Brudvig, L.A. Trait–Environment Interactions Affect Plant Establishment Success during Restoration. Ecology 2020, 101, e02971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camps-Valls, G.; Fernández-Torres, M.-Á.; Cohrs, K.-H.; Höhl, A.; Castelletti, A.; Pacal, A.; Robin, C.; Martinuzzi, F.; Papoutsis, I.; Prapas, I.; et al. Artificial Intelligence for Modeling and Understanding Extreme Weather and Climate Events. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Kattge, J.; Cornelissen, J.H.C.; Wright, I.J.; Lavorel, S.; Dray, S.; Reu, B.; Kleyer, M.; Wirth, C.; Colin Prentice, I.; et al. The Global Spectrum of Plant Form and Function. Nature 2016, 529, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.P.; Van Der Putten, W.H.; Wilschut, R.A.; Veen, G.F. (Ciska); Kardol, P.; Van Ruijven, J.; Allan, E.; Roscher, C.; Van Kleunen, M.; Bezemer, T.M. Plant–Soil Feedbacks and Temporal Dynamics of Plant Diversity–Productivity Relationships. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2021, 36, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornish, E.S.; Campbell, C.; Svejcar, L.; Munson, S.M.; Vaughn, K.; Spaeth, M.K.; Yelenik, S.G.; Wolf, A.; Mitchell, R. Functional Traits Are Used in Restoration Practice: A Response to Merchant et al. (2022). Restoration Ecology 2023, 31, e13880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, T.K.; Henn, J.J.; De Silva, I.; Van Cleemput, E.; Suding, K.N. Aspirational Goals for the Future of Functional Traits in Restoration: A Response to Gornish et al. (2023). Restoration Ecology 2025, 33, e14336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisfield, V.E.; Ficken, C.D.; Allen, B.E.; Jog, S.K.; Bried, J.T. The Potential of Trait Data to Increase the Availability of Bioindicators: A Case Study Using Plant Conservatism Values. Ecological Applications 2023, 33, e2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visscher, A.M.; Vandelook, F.; Fernández-Pascual, E.; Pérez-Martínez, L.V.; Ulian, T.; Diazgranados, M.; Mattana, E. Low Availability of Functional Seed Trait Data from the Tropics Could Negatively Affect Global Macroecological Studies, Predictive Models and Plant Conservation. Annals of Botany 2022, 130, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Yuan, X.; Ran, W.; Zhao, Z.; Su, D.; Song, Y. The Ecological Restoration Strategies in Terrestrial Ecosystems Were Reviewed: A New Trend Based on Soil Microbiomics. Ecology and Evolution 2025, 15, e70994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boretti, A. Evaluating Water Use Efficiency and CO2 Absorption in Plants under Rising Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Levels. Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics 2025, 266, 106409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres--Ruiz, J.M.; Cochard, H.; Delzon, S.; Boivin, T.; Burlett, R.; Cailleret, M.; Corso, D.; Delmas, C.E.L.; De Caceres, M.; Diaz--Espejo, A.; et al. Plant Hydraulics at the Heart of Plant, Crops and Ecosystem Functions in the Face of Climate Change. New Phytologist 2024, 241, 984–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Still, C.J. Trading Water for Carbon. Nature Geosci 2018, 11, 702–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakad, M.; Sevanto, S.; Domec, J.-C.; Katul, G. Linking the Water and Carbon Economies of Plants in a Drying and Warming Climate. Curr. For. Rep. 2023, 9, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Duveiller, G.; Wieneke, S.; Forkel, M.; Gentine, P.; Reichstein, M.; Niu, S.; Migliavacca, M.; Orth, R. Regulation of the Global Carbon and Water Cycles through Vegetation Structural and Physiological Dynamics. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 073008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentine, P.; Green, J.K.; Guérin, M.; Humphrey, V.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S. Coupling between the Terrestrial Carbon and Water Cycles—a Review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 083003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Shi, W.; Xiao, J.; Zhao, M.; Li, X.; Wu, Y. Recent Weakening of Carbon-Water Coupling in Northern Ecosystems. npj Clim Atmos Sci 2025, 8, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Wu, Y.; Xiao, J.; Hui, J.; Hu, J.; Zhao, F.; Qiu, L.; Liu, S. Remote Sensing and Modeling Fusion for Investigating the Ecosystem Water-Carbon Coupling Processes. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 697, 134064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novick, K.A.; Ficklin, D.L.; Stoy, P.C.; Williams, C.A.; Bohrer, G.; Oishi, A.C.; Papuga, S.A.; Blanken, P.D.; Noormets, A.; Sulman, B.N.; et al. The Increasing Importance of Atmospheric Demand for Ecosystem Water and Carbon Fluxes. Nature Clim Change 2016, 6, 1023–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Masri, B.; Schwalm, C.; Huntzinger, D.N.; Mao, J.; Shi, X.; Peng, C.; Fisher, J.B.; Jain, A.K.; Tian, H.; Poulter, B.; et al. Carbon and Water Use Efficiencies: A Comparative Analysis of Ten Terrestrial Ecosystem Models under Changing Climate. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 14680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-P.; Zhang, L.; Liang, X.; Yuan, W. Coupled Models of Water and Carbon Cycles from Leaf to Global: A Retrospective and a Prospective. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2024, 358, 110229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, W.; Van Der Velde, I.R.; Van Schaik, E.; Miller, J.B.; Ciais, P.; Duarte, H.F.; Van Der Laan-Luijkx, I.T.; Van Der Molen, M.K.; Scholze, M.; Schaefer, K.; et al. Increased Water-Use Efficiency and Reduced CO2 Uptake by Plants during Droughts at a Continental Scale. Nature Geosci 2018, 11, 744–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacelar, E.L.V.A.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.M.; Gonçalves, B.M.C.; Brito, C.V.Q.; Gomes-Laranjo, J.; Ferreira, H.M.F.; Correia, C.M. Water Use Strategies of Plants under Drought Conditions. In Plant Responses to Drought Stress; Aroca, R., Ed.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012; pp. 145–170. ISBN 978-3-642-32652-3. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, N.G.; Sapes, G.; Pivovaroff, A.; Adams, H.D.; Allen, C.D.; Anderegg, W.R.L.; Arend, M.; Breshears, D.D.; Brodribb, T.; Choat, B.; et al. Mechanisms of Woody-Plant Mortality under Rising Drought, CO2 and Vapour Pressure Deficit. Nat Rev Earth Environ 2022, 3, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beugnon, R.; Albert, G.; Hähn, G.; Yu, W.; Haider, S.; Hättenschwiler, S.; Davrinche, A.; Rosenbaum, B.; Gauzens, B.; Eisenhauer, N. Improving Forest Ecosystem Functions by Optimizing Tree Species Spatial Arrangement. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikum, D.A.; Shanholtzer, G.F. Application of the Braun-Blanquet Cover-Abundance Scale for Vegetation Analysis in Land Development Studies. Environmental Management 1978, 2, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Wu, M.; Feng, H. Applying Trait-Based Modeling to Achieve Functional Targets during the Ecological Restoration of an Arid Mine Area. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Global Patterns of Plant Functional Traits and Their Relationships to Climate. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Asefa, M.; Cao, M.; Zhang, G.; Ci, X.; Li, J.; Yang, J. Environmental Filtering Structures Tree Functional Traits Combination and Lineages across Space in Tropical Tree Assemblages. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Shipley, B.; Price, J.N.; Dantas, V.D.L.; Tamme, R.; Westoby, M.; Siefert, A.; Schamp, B.S.; Spasojevic, M.J.; Jung, V.; et al. Habitat Filtering Determines the Functional Niche Occupancy of Plant Communities Worldwide. Journal of Ecology 2018, 106, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yu, H.; Yu, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zeng, J.; Chen, P.; Xiao, F.; He, Z.; Yan, Q. Ecological Stability of Microbial Communities in Lake Donghu Regulated by Keystone Taxa. Ecological Indicators 2022, 136, 108695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; He, N.; Fernández--Martínez, M.; Yang, X.; Zuo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Song, J.; Li, G.; et al. Plant Acquisitive Strategies Promote Resistance and Temporal Stability of Semiarid Grasslands. Ecology Letters 2025, 28, e70110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, J.-K. Thriving under Stress: How Plants Balance Growth and the Stress Response. Developmental Cell 2020, 55, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, N.; Adler, P.B.; Chen, D.; Wu, H.; Catford, J.A.; Van Bodegom, P.M.; Bahn, M.; Crawford, K.M.; Chu, C. Relationships between Plant–Soil Feedbacks and Functional Traits. Journal of Ecology 2021, 109, 3411–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardgett, R.D.; Mommer, L.; De Vries, F.T. Going Underground: Root Traits as Drivers of Ecosystem Processes. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2014, 29, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, D.C.; Chalmandrier, L.; Joshi, C.; Renton, M.; Dwyer, J.M.; Funk, J.L. Generating Species Assemblages for Restoration and Experimentation: A New Method That Can Simultaneously Converge on Average Trait Values and Maximize Functional Diversity. Methods Ecol Evol 2018, 9, 1764–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, M.L.; Guo, D.; Iversen, C.M.; Chen, W.; Eissenstat, D.M.; Fernandez, C.W.; Li, L.; Ma, C.; Ma, Z.; Poorter, H.; et al. Building a Better Foundation: Improving Root--trait Measurements to Understand and Model Plant and Ecosystem Processes. New Phytologist 2017, 215, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, H.; Zhang, L.; Cong, C.; Deal, B.; Wang, Y. A Dynamic and Spatially Explicit Modeling Approach to Identify the Ecosystem Service Implications of Complex Urban Systems Interactions. Ecological Indicators 2019, 102, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).