1. Introduction

Mycobacteria species are acid-fast bacteria that can cause infectious diseases in humans [

1,

2]. Some pathogens, such as

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, survives within macrophages by entering a dormant state [

3,

4]. In response, macrophage produce heme oxygenase, which generates toxic carbon monoxide (CO) as a defense mechanism against pathogens [

5]. However,

M. tuberculosis possesses CO dehydrogenase (CO-DH), an enzyme that oxidizes CO to derive energy [

6]. In addition, CO-DH can eliminate nitric oxide (NO), another toxic molecule produced by macrophages [

7]. CO-DH consists of three kinds of subunits and three cofactors; molybdopterin cytosine dinucleotide, flavin adenine dinucleotide, and an iron-sulfur center [

8]. The genes encoding CO-DH including

cutB, which codes for the medium subunit, are organized in an operon [

9,

10] (

Figure 1A). The CO-DH operon has been extensively studied in

Mycobacterium sp. strain JC1, and its expression is regulated by CutR, a transcriptional regulator [

11]. Sequence analysis shows that CutR belongs to the LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) family. CutR-mediated transcriptional regulation is essential for the efficient utilization of CO by

Mycobacterium sp. strain JC1.

LTTRs are composed of an N-terminal DNA-binding domain (DBD) containing a winged helix-turn-helix (wHTH) motif and a C-terminal ligand-binding domain (LBD) [

12,

13]. The LBD functions as a regulatory domain, composing two regulatory subdomains (RD1 and RD2); ligand binding between these subdomains induces a conformational change in the LTTRs. In the classical model of LTTR-dependent transcription regulation, the tetrameric form of LTTR binds to both the recognition binding site (RBS) and the activation binding site (ABS) upstream of target genes in the absence of a co-inducer. Interaction with a co-inducer alters the quaternary structure of the LTTR tetramer, causing a shift of the ABS binding from site-1 to site-2—a mechanism known as “sliding dimer mechanism”—which facilitates RNA polymerase recruitment to the promoter [

14,

15].

CutR functions as an activator, as the expression of CO-DH increases in the presence of CutR, whereas a mutant lacking CutR exhibits a loss of CO-DH activity in

Mycobacterium sp. strain JC1 [

11]. Since glucose represses CO-DH expression, this expression is subject to catabolite repression mediated by the catabolite repression protein (CRP). However, CO-DH in

Mycobacterium sp. strain JC1 is expressed at significant levels under non-catabolite repression conditions, regardless of the presence of CO. No dramatic increase in expression was observed upon CO exposure, suggesting that CO or its derivative is not an essential co-inducer and that CutR may function as a simple transcriptional activator without requiring a tetrameric conformational change.

Mycobacterium sp. strain JC1 contains duplicated CO-DH gene clusters [

10], each with an active promoter located upstream of their respective

cutB genes [

11]. Within the promoter region of

cutB, two inverted repeat (IR) sequences have been identified (

Figure 1B). One corresponds to the conserved CRP binding site, while the other, designated IR1, is essential for CO-DH gene expression. IR1, situated at the −60 position, contains a conserved RBS-like sequence featuring a T-n12-A motif instead of the typical T-n11-A. However, no suitable sequence for the ABS has been identified. Therefore, CutR may function as a dimer. It has been reported that some LTTRs, such as MetR [

16], CatR [

17], and OccR [

18], function as dimers, although the structural model for dimeric LTTRs has not yet been elucidated.

Although CutR is a member of the LTTR family, it exhibits characteristics distinct from those of typical LTTRs. The absence of IR sites that fulfill both RBS and ABS criteria upstream of cutB suggests that CutR does not function as a homotetramer. Furthermore, CutR can activate CO-DH gene transcription in the absence of CO, although CO enhances this expression. In this study, we demonstrate that CutR forms a homodimer that interacts with the IR1 sequence in the absence of CO. We also present the crystal structure of CutR, revealing a dimeric LTTR with two LBDs tightly associated in a symmetrical arrangement, along with the axis of its dimeric DBD complex. The structure further reveals a putative ligand-binding site capable of inducing a local conformational change.

3. Discussion

It is well established that LTTRs bind DNA as dimers through their α4 dimerization helices, and that two dimeric LTTRs can associate via their LBDs to form tetrameric LTTR complexes. Structural studies of tetrameric LTTRs have revealed asymmetric arrangements of their LBDs within homodimeric DBD units, alongside a two-fold symmetric arrangement of LBDs from different DBD pairs as shown in the crystal structure of CbnR [

22] (

Figure 7A). However, to date, no dimeric structure featuring a symmetric LBD arrangement together with a two-fold symmetric DBD dimer has been reported. Symmetric dimeric arrangements of LBDs have been observed in crystal structures of isolated LBDs, such as those of CynR [

23] and Cbl [

24]. In these dimers, the β-sheets from RD1 and RD2 are connected in a parallel manner (

Figure 7B,C). The close contact between RD1 and RD2 subdomains resembles the arrangement of RD subdomains in the DBD pairs of tetrameric LTTRs. This configuration, however, cannot support the characteristic antiparallel interactions of the dimeric DBD, which are necessary for the correct positioning of the two dimerization helices.

In this study, we present the homodimeric, full-length structure of CutR, a representative of the LysR family. The structure is characterized by a pronounced twisting of the two LBD domains, stabilized by the intertwining of the C-terminal β-strand, which results in extensive interactions between the two RD1 subdomains (

Figure 7D). Other LTTRs, such as MetR [

16] and CbbR [

25], which function as dimers, may adopt similarly stable homodimeric structures facilitated by their extended C-terminal peptide regions, as observed in CutR. LTTRs with longer sequences than typical members contain flexible C-terminal tails in their monomeric structures, as suggested by AlphaFold predictions [

15]. PqsR (MvfR) also contains a long C-terminal extension [

26], likely corresponding to the terminal β-strand (β11) in CutR. Notably, the crystal structure of the PqsR LBD lacking this C-terminal tail (PDB ID: 7QA0), in complex with a ligand [

27], demonstrates dimer formation via antiparallel interactions between two RD1 β-sheets (

Figure 7E). The presence of two additional β-strands between the RD1 sheets could facilitate greater rotation of the RD2 subdomains by twisting the β-sheet, enabling further interactions between RD2 subdomains. Thus, these LTTRs containing compact dimeric LBDs require an induction mechanism other than ligand-induced tetramerization.

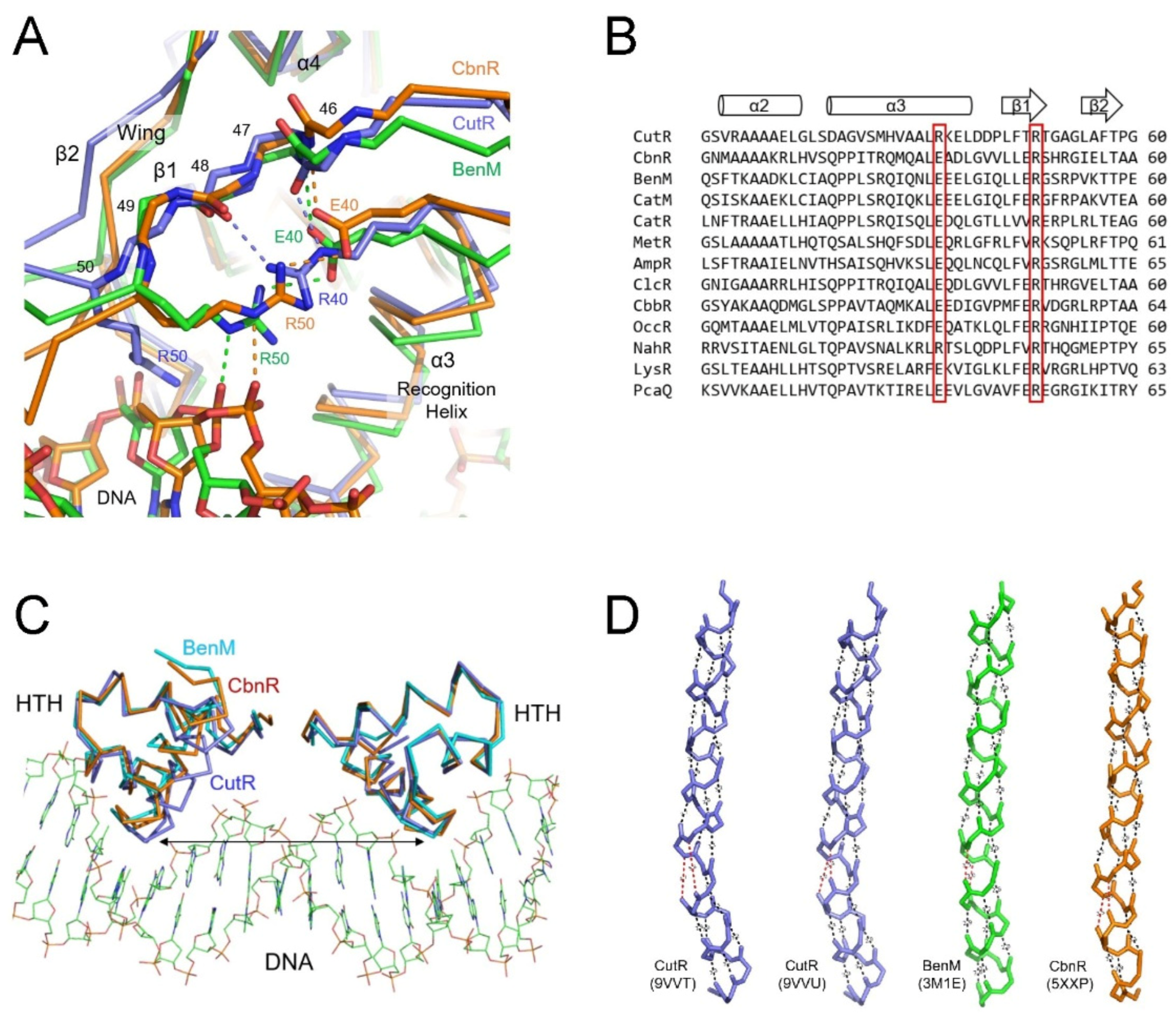

Most LTTRs recognize a conserved T-n11-A sequence, although some bind to modified variants. For example, OccR [

28] binds a shorter T-n10-A sequence, while PcaQ [

29] and IlvY [

30] recognize T-n12-A and T-n13-A sequences, respectively. The conserved thymine bases within the inverted repeat are typically recognized by a residue at position 30 in the recognition helix, as observed in the BenM [

19] and CbnR [

21] structures complexed with their target DNA containing the T-n11-A motif. CutR specifically binds to the IR1 and IR2 sequences containing the T-n12-A motif. In CutR, residue A30, located at the N-terminus of the α3 recognition helix, corresponds to P30 in BenM and CbnR, which recognize the thymine bases. For A30 to interact with both bases, the recognition helices would be expected to be spaced farther apart than in LTTRs that bind the canonical T-n11-A sequence. Surprisingly, structural comparison revealed that the two recognition helices in CutR are actually closer together. This suggests that increasing the distance between the recognition helices—potentially through by local conformational changes near the wHTH motif—may be necessary to optimally recognize the T-n12-A motif.

Although DNA bending and induced fit of the DBD may facilitate the accommodation of the recognition helices within the DNA, the LBD also appears to influence the positioning of the wHTH motif. The distance between the Cα atoms of residue P30 in full-length BenM without DNA (PDB ID: 3K1N) is 31.4 Å, increasing to 33.1~33.7 Å in the presence of DNA (PDB IDs: 4IHS and 4IHT). The LBD affects the position of the wHTH motif, as the structure of the DBD alone (PDB ID: 3M1E) shows a distance of 33.0 Å. The full-length CbnR complexed with DNA displays a distance of 33.4 Å (PDB ID: 7D98), whereas the DBD-DNA complex of CbnR (PDB ID: 5XXP) has a distance of 32.7 Å.

The DNA-binding affinity of CutR is determined by the positioning of the wHTH motifs, including the α3 recognition helices. Both the length and curvature of the α4 dimerization helix influence the spacing between the two wHTH motifs. Since the LBD pair in the CutR dimer is connected to the wHTH motifs through the α4 helix, changes in the arrangement within the LBD pair can affect the bending of the α4 dimerization helices, thereby modulating DNA binding. The crystal structure reveals that glycerol interaction within the cleft between the RD1 and RD2 subdomains can alter the local conformation of these subdomains, including the α6 helix adjacent to the wHTH motif. Optimal positioning of the α3 recognition helices induced by ligand binding could enhance CutR’s affinity for its target DNA.

CutR functions as a constitutive activator of CO-DH expression by forming a compact dimer capable of binding DNA even in the absence of a ligand. Although the distance between its recognition helices is shorter than that observed in DNA-bound LTTRs, CutR still binds its target DNA efficiently. Consistent with this, CO-DH is expressed at a significant baseline level in

Mycobacterium sp. strain JC1 regardless of CO presence, provided that CutR is present. However, CO exposure further enhances CO-DH expression, indicating that ligand binding may induce subtle structural changes in CutR that increase its affinity for the IR1 site, thereby boosting transcriptional activation. Although CO is usually recognized directly by heme-based regulators such as CooA [

31] and RcoM [

32], CutR appears to archive this through the binding of a small molecule at the site of residue E204. Since

Mycobacterium sp. strain JC1 can utilize various C

1 compounds [

6], CutR may recognize a metabolite generated in the presence of CO.

Genomic sequence analysis of Mycobacterium sp. strain JC1 reveals two copies of the CO-DH gene, resulting from a gene cluster duplication. Both cutB genes (cutB1 and cutB2) contain the CutR target sequence IR1 in their upstream regions. CO-DH expression is subject to catabolic repression, as indicated by the presence of a CRP binding site near the promoter regions of both cutB genes, adjacent to IR1. Additionally, IR2 is located upstream of cutB1, likely due to the proximity of the cutR gene. Functional analyses indicate that while both cutB1 and cutB2 promoters are active, cutB2 is more strongly activated by CutR, suggesting that IR1 alone is sufficient for CutR-mediated activation of the cutB genes.

Comparative genomic analysis reveals that most

Mycobacterium species possess a CO-DH gene cluster analogous to the

cutB2 locus in

Mycobacterium sp. strain JC1 (see

Figure 1A). The

cutR gene is highly conserved, particularly in its wHTH motif and key residues of the putative ligand-binding site, including S97, Y164, E204, and W269. All examined species retain a conserved IR motif containing a T-n12-A sequence, designated IR1, which serves as the CutR binding site, although upstream promoter regions may vary. Some species (e.g.,

M. tuberculosis,

M. bovis,

M. marinum) lack the CRP binding motif, whereas others (e.g.,

M. smegmatis) share this feature with

Mycobacterium sp. strain JC1 [

11]. These findings support the hypothesis that CutR functions as a dimer, interacting with the IR sequence to regulate and activate the CO-DH gene cluster across

Mycobacterium species.

Figure 1.

Gene architecture of CO-DH and the DNA sequences upstream of cutB in Mycobacterium sp. strain JC1. (A) Two copies of the genes encoding the three CO-DH subunits (yellow), along with genes involved in the biosynthesis of CO-DH cofactors, are present in Mycobacterium sp. strain JC1. In other Mycobacterium species containing a single copy of the CO-DH genes, the gene corresponding to CutR (gray) is located upstream of the gene corresponding to orf13 (cyan). The nucleotide sequences boxed with dotted lines are shown in (B). (B) An inverted repeat sequence (IR2) is located upstream of cutR, while two inverted repeat sequences (IR1 and the CRP binding site) are located upstream of cutB1 (top). The IR1 sequence upstream of cutB1 is located at the end of orf13 (bottom). Inverted repeat sequences are boxed, and the consensus sequences are highlighted in red. The sequence regions for orf13, cutR, and cutB are colored as in (A).

Figure 1.

Gene architecture of CO-DH and the DNA sequences upstream of cutB in Mycobacterium sp. strain JC1. (A) Two copies of the genes encoding the three CO-DH subunits (yellow), along with genes involved in the biosynthesis of CO-DH cofactors, are present in Mycobacterium sp. strain JC1. In other Mycobacterium species containing a single copy of the CO-DH genes, the gene corresponding to CutR (gray) is located upstream of the gene corresponding to orf13 (cyan). The nucleotide sequences boxed with dotted lines are shown in (B). (B) An inverted repeat sequence (IR2) is located upstream of cutR, while two inverted repeat sequences (IR1 and the CRP binding site) are located upstream of cutB1 (top). The IR1 sequence upstream of cutB1 is located at the end of orf13 (bottom). Inverted repeat sequences are boxed, and the consensus sequences are highlighted in red. The sequence regions for orf13, cutR, and cutB are colored as in (A).

Figure 2.

Size estimation by size-exclusion chromatography. CutR (red line) was eluted at a size corresponding to 54 kDa from a Superdex G75 column. Five proteins used as size standards are marked with inverted triangles: conalbumin (75 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), ribonuclease A (13.7 kDa), and aprotinin (6.5 kDa). CutR (34 kDa) is shown as a monomeric form in the SDS-PAGE (right panel).

Figure 2.

Size estimation by size-exclusion chromatography. CutR (red line) was eluted at a size corresponding to 54 kDa from a Superdex G75 column. Five proteins used as size standards are marked with inverted triangles: conalbumin (75 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), ribonuclease A (13.7 kDa), and aprotinin (6.5 kDa). CutR (34 kDa) is shown as a monomeric form in the SDS-PAGE (right panel).

Figure 3.

DNA-binding ability of CutR. In EMSA, CutR shifts the biotin-labeled DNA fragment containing IR1 or IR2. As the amount of CutR increases (0 to 4 μmole), the unbound DNA fragment containing IR1 at the bottom disappears (A), whereas increasing the DNA fragment (0 to 4 μmole) results in more unbound DNA at the bottom (B). (C) CutR shifts the biotin-labeled DNA fragment containing IR2 in EMSA. (D) Increasing the amount of unlabeled IR2 DNA fragment (0 to 4 μmole) causes the CutR-bound DNA fragment containing IR1 to disappear. (E) The CutR R40A mutant fails to bind the DNA fragment, whereas the Q5A, R7A, R19A, and Q38A mutants bind the DNA similarly to wild-type CutR.

Figure 3.

DNA-binding ability of CutR. In EMSA, CutR shifts the biotin-labeled DNA fragment containing IR1 or IR2. As the amount of CutR increases (0 to 4 μmole), the unbound DNA fragment containing IR1 at the bottom disappears (A), whereas increasing the DNA fragment (0 to 4 μmole) results in more unbound DNA at the bottom (B). (C) CutR shifts the biotin-labeled DNA fragment containing IR2 in EMSA. (D) Increasing the amount of unlabeled IR2 DNA fragment (0 to 4 μmole) causes the CutR-bound DNA fragment containing IR1 to disappear. (E) The CutR R40A mutant fails to bind the DNA fragment, whereas the Q5A, R7A, R19A, and Q38A mutants bind the DNA similarly to wild-type CutR.

Figure 4.

Crystal structure of CutR. (A) Ribbon diagram of a CutR monomer, comprising the N-terminal DNA-binding domain (DBD), which includes a winged helix-turn-helix motif (wHTH) (slate) and a dimerization helix (cyan), and the C-terminal ligand-binding domain (LBD) containing two regulatory subdomains: RD1 (yellow), RD2 (magenta), and an additional β-strand (green). The position of L162 is highlighted in red. (B) Ribbon diagram of the CutR dimer (slate/orange) highlighting four interacting regions (red circles), including an antiparallel interaction of the α4 dimerization helices, intertwining of the β11 strands connecting the two RD1 β-sheets, and a parallel interaction of the α9 helices in RD2. (C) Topology diagram of the CutR LBD dimer. Two five-stranded RD1 β-sheets form a 12-stranded β-sheet together with two β11 strands arranged antiparallel. The five-stranded RD2 β-sheet is connected to RD1 through the β6 and β10 strands. (D) Interaction between one RD1 and the RD2 of the other monomer is stabilized by hydrogen bonds between V305 and I221 and an ionic interaction between R308 and E216, enhancing the dimerization of the CutR LBD. (E) Parallel arrangement of α9 and α10 helices from both RD2 subdomains. Subdomains participating in the interaction from the two subunits are colored slate and orange. The residues at the interface are shown as sticks.

Figure 4.

Crystal structure of CutR. (A) Ribbon diagram of a CutR monomer, comprising the N-terminal DNA-binding domain (DBD), which includes a winged helix-turn-helix motif (wHTH) (slate) and a dimerization helix (cyan), and the C-terminal ligand-binding domain (LBD) containing two regulatory subdomains: RD1 (yellow), RD2 (magenta), and an additional β-strand (green). The position of L162 is highlighted in red. (B) Ribbon diagram of the CutR dimer (slate/orange) highlighting four interacting regions (red circles), including an antiparallel interaction of the α4 dimerization helices, intertwining of the β11 strands connecting the two RD1 β-sheets, and a parallel interaction of the α9 helices in RD2. (C) Topology diagram of the CutR LBD dimer. Two five-stranded RD1 β-sheets form a 12-stranded β-sheet together with two β11 strands arranged antiparallel. The five-stranded RD2 β-sheet is connected to RD1 through the β6 and β10 strands. (D) Interaction between one RD1 and the RD2 of the other monomer is stabilized by hydrogen bonds between V305 and I221 and an ionic interaction between R308 and E216, enhancing the dimerization of the CutR LBD. (E) Parallel arrangement of α9 and α10 helices from both RD2 subdomains. Subdomains participating in the interaction from the two subunits are colored slate and orange. The residues at the interface are shown as sticks.

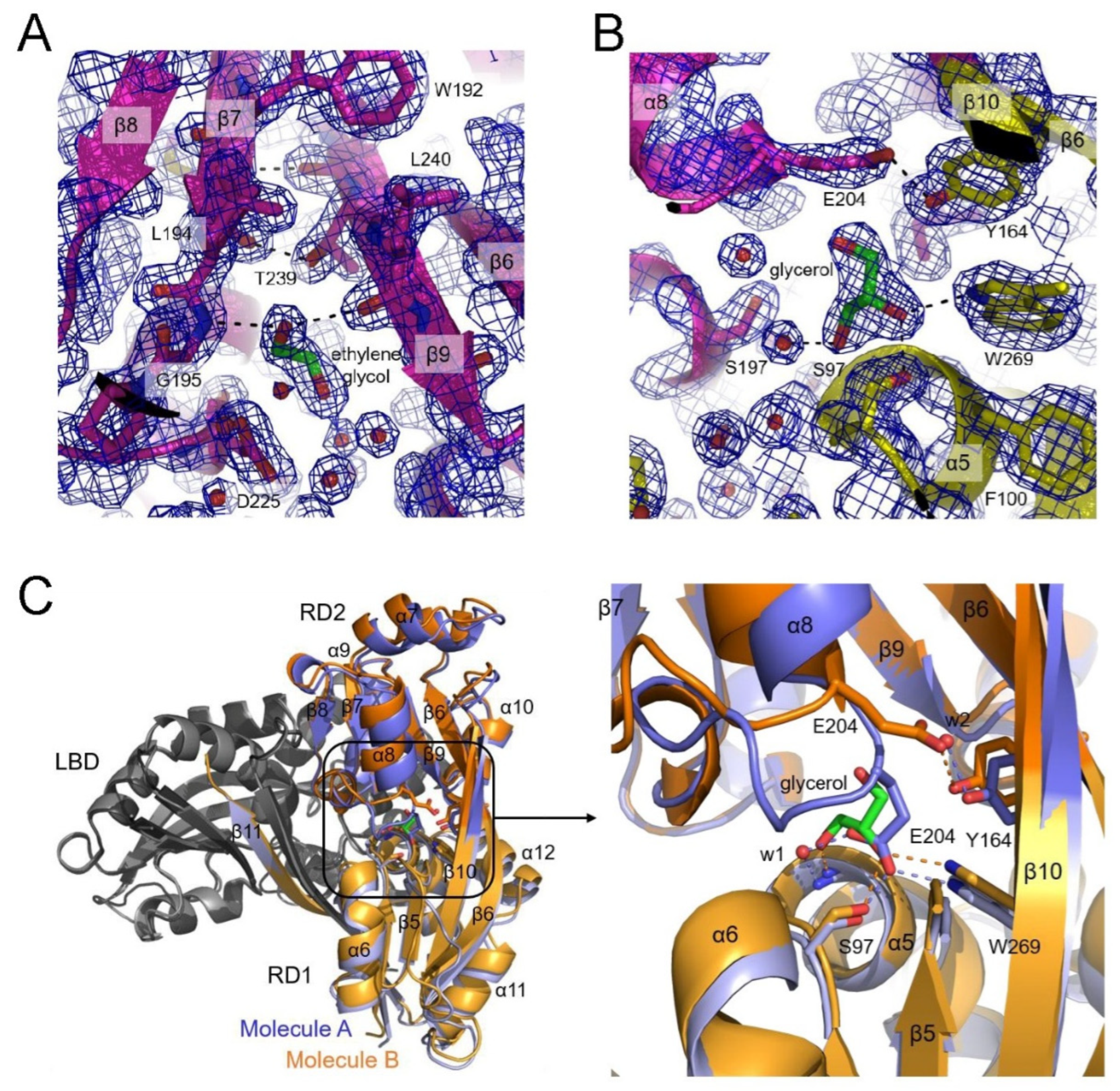

Figure 5.

Putative ligand-binding site. (A) The electron density map reveals an ethylene glycol molecule (green) located between the β7 and β9 strands in the RD2 subdomain (magenta), linking their C-termini through hydrogen bonds (dashed lines). (B) A glycerol molecule (green) positioned between the RD1 (yellow) and RD2 (magenta) subdomains is surrounded by residues S97, Y164, S197, E204, and W269 in molecule B. (C) Two CutR LBD dimers are depicted as ribbon diagrams. Molecule A (slate) of one LBD dimer is superimposed on molecule B (orange) of the other dimer, with the other subunits in both LBD dimers colored gray. RD1 subdomains are shown in lighter shades than RD2 in both LBDs. A glycerol molecule (green) is situated between the RD1 and RD2 subdomains in molecule B. The boxed area is zoomed in the right panel. In molecule A (slate), the α8 helix and the following loop are positioned close to the α5 and α6 helices of RD2, and the side chain of E204 in the loop forms hydrogen bonds with S97 and W269. In molecule B (orange), a glycerol molecule (green) occupies the position corresponding to E204 in molecule A. The side chain of E204 in molecule B is oriented toward the β10 strand and interacts with Y164.

Figure 5.

Putative ligand-binding site. (A) The electron density map reveals an ethylene glycol molecule (green) located between the β7 and β9 strands in the RD2 subdomain (magenta), linking their C-termini through hydrogen bonds (dashed lines). (B) A glycerol molecule (green) positioned between the RD1 (yellow) and RD2 (magenta) subdomains is surrounded by residues S97, Y164, S197, E204, and W269 in molecule B. (C) Two CutR LBD dimers are depicted as ribbon diagrams. Molecule A (slate) of one LBD dimer is superimposed on molecule B (orange) of the other dimer, with the other subunits in both LBD dimers colored gray. RD1 subdomains are shown in lighter shades than RD2 in both LBDs. A glycerol molecule (green) is situated between the RD1 and RD2 subdomains in molecule B. The boxed area is zoomed in the right panel. In molecule A (slate), the α8 helix and the following loop are positioned close to the α5 and α6 helices of RD2, and the side chain of E204 in the loop forms hydrogen bonds with S97 and W269. In molecule B (orange), a glycerol molecule (green) occupies the position corresponding to E204 in molecule A. The side chain of E204 in molecule B is oriented toward the β10 strand and interacts with Y164.

Figure 6.

Structure of DNA-binding domains. (A) The position of the wing, consisting of the β1 and β2 strands, is stabilized through the interaction of R40, which contacts the main chain of the β1 strand from the α3 recognition helix in CutR (slate). In the CbnR (orange) and BenM (green) structures, E40 from the α3 helix stabilizes the β1 strand. R50 from the β1 strand interacts with the phosphate backbone of DNA. (B) Glutamate or arginine at the α3 helix and arginine at the β1 strand are conserved in all LTTRs. (C) The distance between the α3 recognition helices in the CutR dimer (slate) is shorter than those in the DBD dimers of CbnR (orange) and BenM (cyan). The arrow indicates the distance between A30, which corresponds to P40 in BenM or CbnR, recognizing the thymine bases in the conserved T-n11-A DNA sequence. (D) The curvature of the α4 dimerization helix results from a kink in the helix. More gaps in the broken hydrogen bonds within the CutR helix increase its curvature, thereby decreasing the distance between the two recognition helices in a DBD dimer. Hydrogen bonds within the helix are shown with dashed lines; broken hydrogen bonds are highlighted in red. The PDB IDs are provided in parentheses.

Figure 6.

Structure of DNA-binding domains. (A) The position of the wing, consisting of the β1 and β2 strands, is stabilized through the interaction of R40, which contacts the main chain of the β1 strand from the α3 recognition helix in CutR (slate). In the CbnR (orange) and BenM (green) structures, E40 from the α3 helix stabilizes the β1 strand. R50 from the β1 strand interacts with the phosphate backbone of DNA. (B) Glutamate or arginine at the α3 helix and arginine at the β1 strand are conserved in all LTTRs. (C) The distance between the α3 recognition helices in the CutR dimer (slate) is shorter than those in the DBD dimers of CbnR (orange) and BenM (cyan). The arrow indicates the distance between A30, which corresponds to P40 in BenM or CbnR, recognizing the thymine bases in the conserved T-n11-A DNA sequence. (D) The curvature of the α4 dimerization helix results from a kink in the helix. More gaps in the broken hydrogen bonds within the CutR helix increase its curvature, thereby decreasing the distance between the two recognition helices in a DBD dimer. Hydrogen bonds within the helix are shown with dashed lines; broken hydrogen bonds are highlighted in red. The PDB IDs are provided in parentheses.

Figure 7.

Dimeric structures of the ligand-binding domains. Arrangements of the four RD subdomains in an LBD dimer are shown as ribbon diagrams from the tetrameric CbnR complex exhibiting separated DBDs (gray) (A); the crystal structures of LBD dimers of CynR (B) and Cbl (C); the dimeric CutR structure (D); and the crystal structure of the LBD dimer of MvfR in the absence of the C-terminal tail (E). Molecules B are depicted in lighter shades than molecules A in the LBD dimers. There is no interaction between the two RD1 subdomains of CynR and Cbl, whereas CutR and MvfR exhibit RD1-RD1 interactions. Twisting of the connected RD1 β-sheets facilitates contact between the two RD2 domains and brings the two DBDs into close proximity in the CutR dimer. Arrows indicate the location of the DBD.

Figure 7.

Dimeric structures of the ligand-binding domains. Arrangements of the four RD subdomains in an LBD dimer are shown as ribbon diagrams from the tetrameric CbnR complex exhibiting separated DBDs (gray) (A); the crystal structures of LBD dimers of CynR (B) and Cbl (C); the dimeric CutR structure (D); and the crystal structure of the LBD dimer of MvfR in the absence of the C-terminal tail (E). Molecules B are depicted in lighter shades than molecules A in the LBD dimers. There is no interaction between the two RD1 subdomains of CynR and Cbl, whereas CutR and MvfR exhibit RD1-RD1 interactions. Twisting of the connected RD1 β-sheets facilitates contact between the two RD2 domains and brings the two DBDs into close proximity in the CutR dimer. Arrows indicate the location of the DBD.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics.

| Data Set |

SeMet |

Native |

| Experimental Data |

|

|

| X-Ray source |

PAL 4A |

PAL 7A |

| Wavelength (Å) |

0.97926 |

0.97933 |

| Space group |

P212121 |

P212121 |

| Unit cell parameters |

|

|

|

a, b, c (Å) |

63.50, 92.08, 126.19 |

69.93, 81.81, 101.06 |

| α, β, γ (°) |

90.00, 90.00, 90.00 |

90.00, 90.00, 90.00 |

Resolution limit (Å)

Total reflections

Unique reflections

Redundancy

Completeness (%) |

50–2.50 (2.59–2.50) a

378,265

26,311

14.4 (14.6)

100 (100) |

50–1.80 (1.83–1.80)

337,472

52,582

6.4 (3.8)

96.5 (76.4) |

| Rsymm b

|

0.117 (0.492) |

0.062 (0.569) |

| Average I/σ (I) |

43.4 (6.2) |

37.8 (3.0) |

| Refinement Details |

|

|

| Resolutions (Å) |

40.26–2.50 |

36.62–1.80 |

Reflections (working)

Reflections (test) |

23,187

1252 |

50,949

1949 |

| Rwork/Rfree c

|

0.212/0.268 |

0.191/0.233 |

| Number of Waters |

44 |

398 |

| RMSD |

|

|

| Bond length (Å) |

0.008 |

0.005 |

Bond angle (o)

Average B factors (Å) |

1.115 |

0.736

|

Mol. A (main/side)

Mol. B (main/side)

Waters |

35.95 (35.73/36.21)

39.08 (39.02/39.14)

34.30 |

33.06 (30.22/36.31)

34.19 (37.05/31.72)

32.37 |