1. Introduction

Microorganisms inhabiting extreme environments have evolved remarkable mechanisms to withstand the detrimental effects of ionizing radiation (Nayak et al., 2021). Ionizing radiation, encompassing gamma rays, X-rays, and cosmic rays, possesses sufficient energy to remove tightly bound electrons from atoms (WHO, 2020), leading to the formation of free radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Azzam et al., 2012). These highly reactive molecules can inflict severe damage on cellular macromolecules (Kricka & Park, 2014), including DNA, proteins, and lipids, thereby compromising cellular integrity and function. For instance, lipid peroxidation, particularly of polyunsaturated fatty acids, results in increased membrane permeability (Bresciani et al., 2015) and loss of membrane potential, disrupting cellular homeostasis (Goran Slivšek et al., 2025). Similarly, radiation-induced DNA damage manifests as single- and double-strand breaks, base modifications, and crosslinking, which, if unrepaired, can lead to mutations, genomic instability, or cell death (Willers et al., 2004, Azzam et al., 2012).

To mitigate such damage, microorganisms have developed multifaceted strategies. DNA repair mechanisms, such as homologous recombination and base excision repair, are pivotal in restoring genetic integrity (Choi et al., 2020, Waters, 2006). Antioxidant systems, including superoxide dismutases and catalases, neutralize ROS (Jena et al., 2023), while pigment production, notably melanin, offers protection by scavenging free radicals and absorbing harmful radiation(Herrling et al., 2008). Furthermore, efficient energy metabolism ensures the ATP-dependent processes required for repair and maintenance (Kierans & Taylor, 2024).

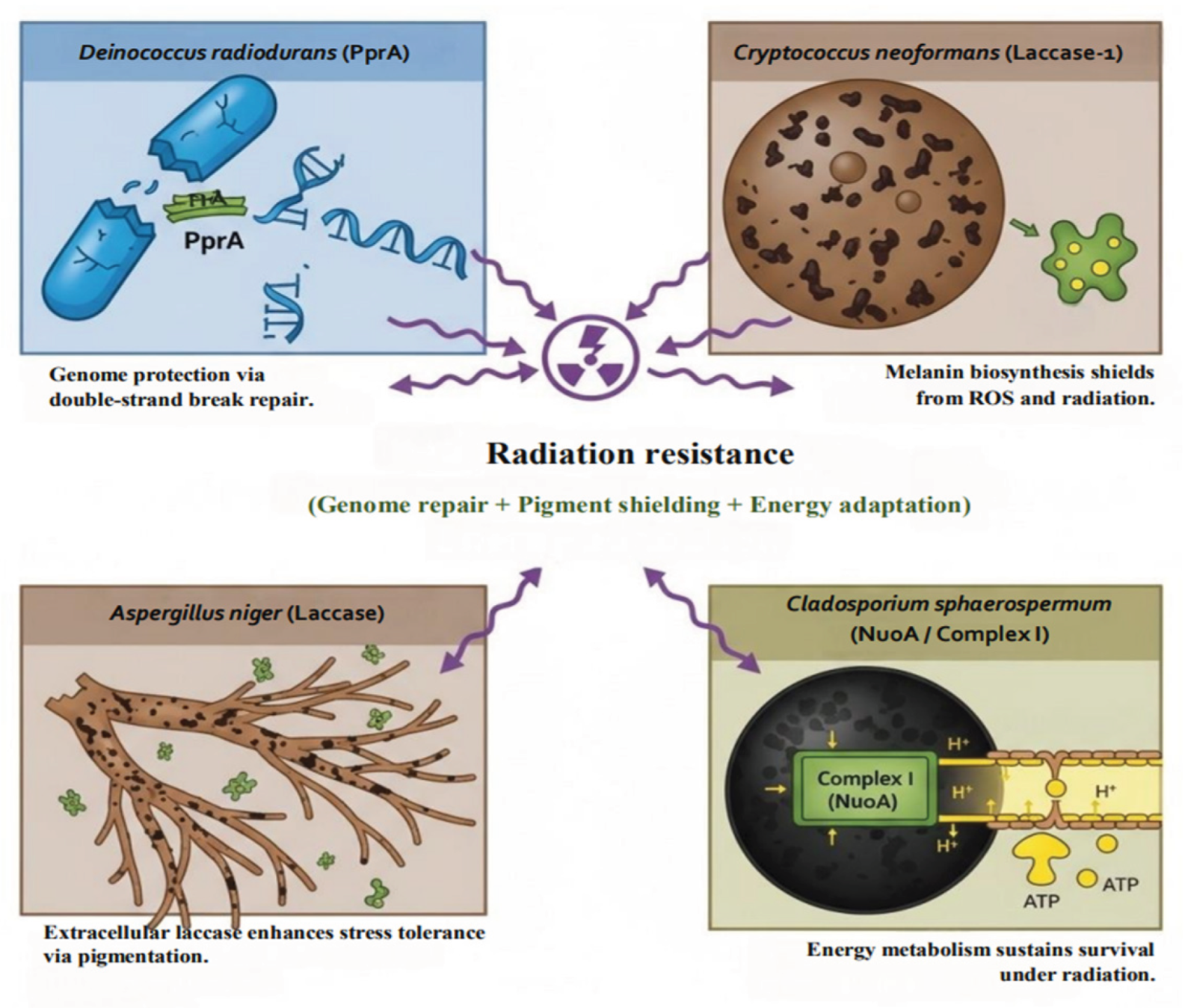

Among the diverse array of extremophiles, certain bacteria and fungi stand out for their exceptional radiation resistance. Deinococcus radiodurans, often termed the “Conan the Bacterium,” exhibits unparalleled resilience to ionizing radiation (Makarova et al., 2001). This bacterium can repair over 100 double-strand breaks per chromosome without lethality or mutagenesis, primarily through RecA-dependent homologous recombination pathways (Minton, 1994). Fungi, particularly melanized species, also demonstrate significant radioresistance. Cryptococcus neoformans, a basidiomycetous fungus, has been identified in radioactive environments (Jung et al., 2016) such as the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone (Dadachova & Casadevall, 2008). Its melanized form contributes to its resistance against ionizing radiation (Malo et al., 2018) by absorbing radiation and neutralizing free radicals (Dadachova et al., 2007). Similarly, Aspergillus niger, a ubiquitous filamentous fungus, produces melanin (Zakaria, 2024) and exhibits high resistance to UV-C and cosmic radiation (Markéta Kulišová et al., 2024). Studies have shown that its spores can withstand high doses of X-ray and cosmic radiation, highlighting its potential in biotechnological applications (Cortesão et al., 2020). Cladosporium sphaerospermum, a dematiaceous fungus, has garnered attention for its unique ability to utilize ionizing radiation (Pritideepa Behera et al., 2025) as an energy source (Marcotulli, 2025), a phenomenon termed radiosynthesis. This fungus survives well in radiation-rich environments, such as the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, by converting gamma radiation into chemical energy, facilitated by its melanin content (Travers, 2024).

Despite the growing body of research on individual mechanisms of radiation resistance, a comprehensive comparative analysis across different organisms is lacking. The roles of DNA repair, pigment-mediated protection and energy metabolism are central to the survival of microorganisms in extreme environments. Examining the interactions among these processes provides valuable insights into their adaptive strategies. Such understanding also highlights potential applications.

This study aims to fill this gap by conducting a comparative functional analysis of key proteins involved in radiation resistance across D. radiodurans, C. neoformans, A. niger, and C. sphaerospermum. By integrating bioinformatics tools such as BLASTp, InterProScan, and KEGG pathway mapping, we seek to elucidate the molecular underpinnings of their adaptive strategies. The findings from this comparative framework not only enhance our understanding of microbial life in extreme environments but also open avenues for innovative applications in bioremediation, biotechnology, and space exploration.

2. Methodology

2.1. Retrieval of Protein Sequences

Protein sequences representing radiation resistance and stress adaptation were retrieved from the UniProt Knowledgebase (UniProtKB) (Bateman et al., 2024). Four proteins were selected based on their documented roles in extremophilic organisms: NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain 4 from Cladosporium sphaerospermum (Protein ID: tr|A0A7H1KGJ9), Laccase-1 from Cryptococcus neoformans (Accession: Q55P57), PprA from Deinococcus radiodurans (Protein ID: sp|O32504), and Laccase from Aspergillus niger (Accession: A0A100ITR7). FASTA sequences were downloaded in standard format for subsequent analyses. The choice of these four organisms was deliberate: D. radiodurans serves as a benchmark bacterial model with well-characterized DNA repair machinery (Liu et al., 2023), while the three fungi represent diverse and underexplored mechanisms of radiation resistance—melanin-associated shielding (Dadachova & Casadevall, 2008), extracellular laccase-driven pigmentation (Samim Dullah et al., 2021), and energy adaptation through mitochondrial Complex I (Casadevall et al., 2017). This asymmetric selection (one bacterium and three fungi) reflects the current knowledge gap, as fungi are increasingly recognized in radioactive environments such as Chernobyl yet remain less studied than bacteria, making them central to uncovering novel strategies of bioremediation and survival under ionizing radiation.

2.2. Sequence Similarity Search (BLASTp)

Each protein sequence was queried against the NCBI non-redundant protein database (nr) using BLASTp (Altschul et al., 1990) with default parameters. Significant homologs were identified based on percentage identity, alignment length, E-value thresholds (<1e−5), and bit scores (Madeira et al., 2019). Top hits were selected to confirm evolutionary conservation and taxonomic distribution.

2.3. Functional Annotation and Domain Analysis

Protein functional features were annotated using InterProScan (Blum et al., 2024). Conserved domains and structural motifs were identified based on Pfam, SMART, PROSITE, and related databases. Gene Ontology (GO) terms were assigned for biological processes, molecular functions, along with cellular components. Signal peptides and transmembrane domains were also assessed where applicable.

2.4. Pathway Mapping

Proteins were functionally placed within biological pathways using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Automatic Annotation Server (KAAS). KEGG Orthology (KO) identifiers were assigned, and pathways were reconstructed to identify the role of each protein within metabolic and stress-adaptation frameworks. KEGG Mapper tools (Kanehisa & Sato, 2019) were used to visualize pathway associations, including oxidative phosphorylation and secondary metabolite biosynthesis (Kanehisa et al., 2021).

2.5. Comparative Functional Analysis

The integration of BLASTp similarity searches, InterProScan domain predictions, and KEGG pathway mapping provided the basis for functional annotation of the target proteins. Comparative insights were derived across the four organisms to identify both conserved roles and species-specific adaptations. Proteins were subsequently grouped into three adaptive categories: (i) DNA repair, (ii) melanin biosynthesis, and (iii) energy metabolism. Literature evidence was incorporated to corroborate computational predictions and to place the annotated functions within the broader context of microbial radiation resistance.

3. Results

To elucidate the molecular underpinnings of radiation resistance and stress tolerance, four representative proteins from radiation-adapted microorganisms were functionally annotated and compared: NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain 4 from Cladosporium sphaerospermum, Laccase-1 from Cryptococcus neoformans, PprA from Deinococcus radiodurans, and Laccase from Aspergillus niger. These proteins encompass three complementary adaptive axes (Energy metabolism, pigment-mediated protection, and DNA repair) forming an integrative model of microbial resilience.

3.1. NADH-Ubiquinone Oxidoreductase Chain 4 (Cladosporium sphaerospermum)

Sequence analysis of the NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain 4 (Protein ID: tr|A0A7H1KGJ9) revealed a high degree of conservation across fungi. The top BLASTp hit (QJS52743.1) showed 98.75% identity over 481 amino acids (E-value = 0.0), with additional homologs sharing 84–91% identity. Such conservation underscores its essential role in the mitochondrial electron transport chain.

InterProScan identified two key domains; NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase family (IPR003918) and NADH-quinone oxidoreductase chain M/4 subgroup (IPR010227), with multiple transmembrane motifs (ND/Mrp_TM, Proton_antipo_M) confirming its integral membrane localization. GO annotations associated the protein with ATP synthesis coupled electron transport (GO:0042773) and aerobic respiration (GO:0009060).

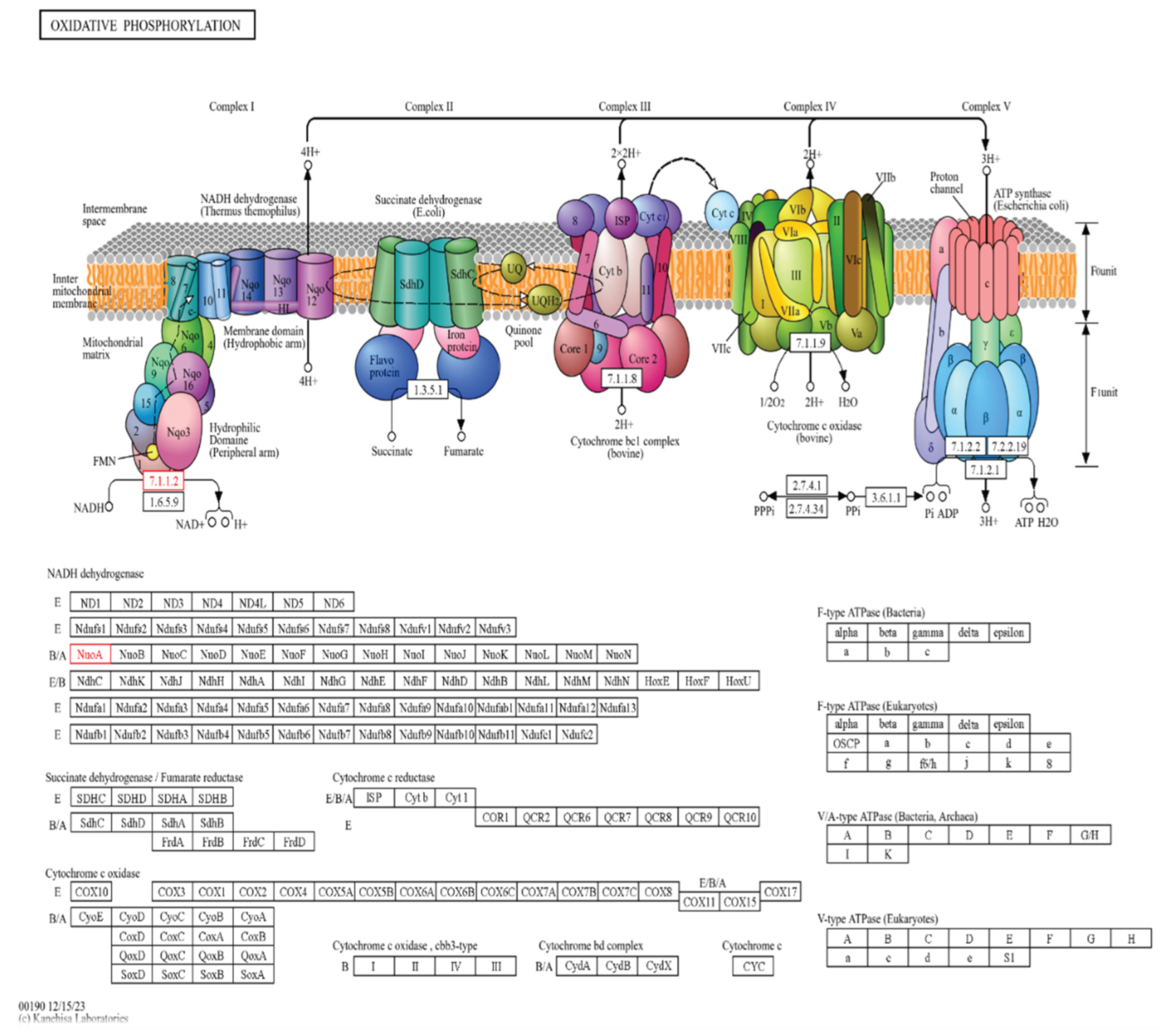

KEGG mapping assigned the sequence to KO K00330 (nuoA; EC 7.1.1.2), placing it in the oxidative phosphorylation pathway (map00190) and within module M00144 (NADH:quinone oxidoreductase). These findings confirm its role in Complex I-mediated proton translocation. In the black fungus C. sphaerospermum, this efficiency in oxidative phosphorylation likely underpins radiation resistance by maintaining redox balance and fueling energy-intensive repair responses.

Figure 1.

The KEGG oxidative phosphorylation pathway mapping for C. sphaerospermum.

Figure 1.

The KEGG oxidative phosphorylation pathway mapping for C. sphaerospermum.

Table 1.

InterProScan domain analysis of Cladosporium sphaerospermum NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain 4.

Table 1.

InterProScan domain analysis of Cladosporium sphaerospermum NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain 4.

| Protein ID |

InterPro Domain |

GO BP |

GO MF |

GO CC |

Features/Notes |

| A0A7H1KGJ9 |

IPR003918, IPR010227 |

ATP synthesis coupled electron transport; electron transport coupled proton transport; aerobic respiration |

NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) activity; ubiquinone binding |

Mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I |

Transmembrane domain (ND/Mrp_TM, Proton_antipo_M) |

Table 2.

KEGG pathway mapping assigned the protein to KO entry K00330 (nuoA; NADH-quinone oxidoreductase subunit A, EC:7.1.1.2).

Table 2.

KEGG pathway mapping assigned the protein to KO entry K00330 (nuoA; NADH-quinone oxidoreductase subunit A, EC:7.1.1.2).

| Protein ID |

KO Number |

KEGG Pathway |

Role in Pathway |

BRITE (KO) |

BRITE (Enzyme) |

Notes |

| A0A7H1KGJ9 |

K00330 |

Oxidative phosphorylation (map00190) |

Electron transport / ATP production |

Metabolism → Energy metabolism → Oxidative phosphorylation |

Translocase → Proton translocation → Linked to oxidoreductase reactions → NADH:ubiquinone reductase |

Supports radiation resistance & stress tolerance |

3.2. Laccase-1 (Cryptococcus neoformans)

The laccase-1 protein (Q55P57), a well-established determinant of melanin biosynthesis in C. neoformans, exhibited complete identity (100% with XP_774374.1) across 624 amino acids (E-value = 0.0). Homologous sequences from related fungi (82–90% identity) confirmed its evolutionary conservation.

InterProScan detected three copper-binding domains; Cu-oxidase_3 (PF07731), Cu-oxidase (PF00394) and Cu-oxidase_2 (PF07732), and the presence of a signal peptide, suggesting extracellular secretion. Functional annotation highlighted copper ion binding (GO:0005507) and oxidoreductase activity (GO:0016491). KEGG mapping associated the protein with KO K05909 (laccase; EC 1.10.3.2) under the oxidoreductase class.

Functionally, laccase-1 catalyzes the oxidation of diphenolic substrates to polymeric melanin, which provides both oxidative and radiation shielding. This dual functionality links metabolic adaptation to pathogenicity and environmental stress survival.

3.3. PprA (Deinococcus radiodurans)

The PprA protein (sp|O32504), a defining feature of D. radiodurans radiation resilience, displayed 65–99% sequence identity across homologs from related strains (E-values 2.8 × 10⁻¹⁴⁵ to 1.1 × 10⁻⁸⁷). Despite the absence of conserved domains or KEGG pathway mapping, literature-supported evidence establishes its role in DNA double-strand break repair and genome reassembly after irradiation.

The absence of conventional domain signatures suggests PprA’s non-enzymatic, regulatory mechanism in promoting DNA end-joining and replication restart, highlighting a unique bacterial adaptation distinct from metabolic or pigment-based defenses.

3.4. Laccase (Aspergillus niger)

The PprA protein (sp|O32504), a defining feature of D. radiodurans radiation resilience, displayed 65–99% sequence identity across homologs from related strains (E-values 2.8 × 10⁻¹⁴⁵ to 1.1 × 10⁻⁸⁷). Despite the absence of conserved domains or KEGG pathway mapping, literature-supported evidence establishes its role in DNA double-strand break repair and genome reassembly after irradiation.

The absence of conventional domain signatures suggests PprA’s non-enzymatic, regulatory mechanism in promoting DNA end-joining and replication restart, highlighting a unique bacterial adaptation distinct from metabolic or pigment-based defenses.

3.5. Comparative Analysis

Functional grouping of these proteins delineates a multi-layered adaptation network:

Energy metabolism and redox balance: C. sphaerospermum NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase supports efficient ATP generation and proton-coupled electron flow during oxidative stress.

Direct DNA repair and genome integrity: D. radiodurans PprA provides a unique protein-based repair mechanism independent of canonical enzyme systems.

Pigment-based protection: Fungal laccases in C. neoformans and A. niger mediate melanin synthesis, forming extracellular barriers that mitigate radiation and oxidative damage.

Table 3.

A summary of annotations.

Table 3.

A summary of annotations.

| Protein (Organism) |

Gene Name |

Length (aa) |

InterPro Domains / Family |

GO Terms (BP / MF / CC) |

KO Number |

KEGG Pathways / Modules |

Notes |

| NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain 4 (Cladosporium sphaerospermum) |

nad4 |

493 |

NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (IPR003918, IPR010227) |

BP: ATP synthesis coupled electron transport (GO:0042773)

MF: NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) activity (GO:0008137)

CC: None |

K00330 |

Oxidative phosphorylation (map00190)

Metabolic pathways (map01100)

Module M00144 |

Proton translocation, energy metabolism |

| Laccase-1 (Cryptococcus neoformans) |

LAC1 |

624 |

Multicopper oxidase (IPR045087) |

BP: None

MF: copper ion binding (GO:0005507), oxidoreductase activity (GO:0016491)

CC: None |

K05909 |

Multicopper oxidase activity (EC 1.10.3.2) |

Melanin biosynthesis |

| DNA repair protein PprA (Deinococcus radiodurans) |

pprA |

300 |

None predicted |

None |

None |

None |

Radiation resistance; no KEGG mapping available |

| Laccase (Aspergillus niger) |

ABL_09622 |

559 |

Multicopper oxidase (IPR045087) |

BP: None

MF: copper ion binding (GO:0005507), oxidoreductase activity (GO:0016491)

CC: None |

K05909 |

Same as C. neoformans laccase |

Melanin biosynthesis |

3.6. Overall Interpretation

The comparative annotation underscores how radiation-resistant microbes integrate complementary molecular systems; energy metabolism, pigment biosynthesis, and DNA repair to sustain survival under high-radiation stress. While D. radiodurans relies primarily on direct DNA restoration, melanized fungi employ bioenergetic and pigment-mediated resilience, leveraging efficient oxidative phosphorylation and extracellular melanin polymerization.

This integrative framework suggests convergent evolution of multi-axis defense mechanisms, providing foundational insights for potential applications in bioremediation, industrial biotechnology, and astrobiology.

4. Discussion

Microorganisms inhabiting extreme environments have evolved diverse molecular strategies to mitigate the damage caused by ionizing radiation (Dadachova & Casadevall, 2008). This study examined four representative proteins; PprA from Deinococcus radiodurans, Laccase-1 from Cryptococcus neoformans, Laccase from Aspergillus niger, and NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit A from Cladosporium sphaerospermum—to explore the molecular foundations of radiation resistance across bacteria and fungi. Functional annotation through BLASTp, InterProScan, and KEGG mapping revealed three interrelated protective mechanisms: DNA repair, melanin-mediated shielding, and energy metabolism. Together, these layers highlight how microbial resilience arises from a coordinated network of genomic, biochemical, and physiological adaptations.

4.1. DNA Repair as the First Line of Defense

Deinococcus radiodurans remains one of the most radiation-resistant organisms known (Repar et al., 2010), with its PprA protein central to this capacity (Adachi et al., 2014). Our analysis confirmed the strong conservation of PprA across D. radiodurans strains, underscoring its essential role in repairing double-strand DNA breaks. Although no functional domain or pathway was annotated by InterProScan or KEGG, this reflects the protein’s unique structural specialization—typical of extremophile genomes. PprA acts as a DNA end-binding factor that promotes efficient rejoining of DNA fragments (Narumi et al., 2004; Ishino & Narumi, 2015; Bowater & Doherty, 2006). Such rapid genome reconstitution ensures cellular survival before secondary stress responses are activated, exemplifying DNA repair as the first and most critical barrier to radiation-induced lethality.

4.2. Melanin Biosynthesis and Pigment Shielding

In fungi, melanin synthesis represents a convergent evolutionary strategy against radiation and oxidative stress (Eisenman & Casadevall, 2011). Both C. neoformans Laccase-1 and A. niger Laccase mapped to KO:K05909, confirming their roles as multicopper oxidases catalyzing the oxidation of L-DOPA and related phenolics during melanin polymerization. These enzymes are key to producing the dark pigments that absorb ionizing radiation and neutralize free radicals (Eisenman & Casadevall, 2011; Dadachova et al., 2007; Różanowska et al., 1999). Experimental data further demonstrate that melanized fungi, including fast- and slow-growing species, show markedly improved survival under deuteron and X-ray exposure (Pacelli et al., 2017). Likewise, melanin from Gliocephalotrichum simplex has been reported to protect plant seeds from gamma radiation, preserving germination capacity (Kunal et al., 2025). These observations reinforce melanin’s role as a biochemical shield that complements genomic repair, ensuring both molecular and cellular integrity under radiation stress.

4.3. Energy Metabolism and Adaptive Physiology

Our annotation of the Cladosporium sphaerospermum NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain 4 (KO:K00330) highlights energy metabolism as a third adaptive pillar. As a subunit of Complex I, this protein participates in electron transport and proton pumping, generating ATP that supports repair, stress signaling and survival under nutrient-limited or hostile conditions. The integration of robust energy metabolism with melanin-based protection may synergistically enhance survival in radiation-rich environments. Previous reports from Chernobyl have shown that melanized fungi not only resist radiation but also may utilize it as an energy source through a process termed radiosynthesis (Shunk et al., 2020). Our annotation of the NuoA-like protein supports this hypothesis by placing oxidative phosphorylation at the core of energy-linked stress responses in melanized fungi.

Prior studies suggest that Cladosporium sphaerospermum, known colloquially as a “black fungus,” may exploit melanin-associated energy capture under high radiation (Dadachova et al., 2007) while maintaining its usual metabolic energy-generating pathways. Melanin also confers significant radioprotective benefits, enhancing fungal survival under ionizing radiation stress (Pacelli et al., 2017). Together, such traits imply a functional interplay between pigmentation and energy transduction in extremotolerance. Experiments aboard the International Space Station demonstrated that a lawn of C. sphaerospermum biomass attenuated incident ionizing compared to a non-fungal control, and also exhibited a modest growth advantage in space relative to ground controls (Averesch et al., 2022). While these results do not establish a definitive pathway for radiation-derived energy capture, they are consistent with the hypothesis that melanin pigmentation contributes to both radioprotection and metabolic adaptation in extremotolerant fungi. Although the precise biochemical pathway(s) for converting radiation into usable metabolic energy remain incompletely characterized, our identification of a core Complex I ortholog (KEGG K00330, NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit A) associated with oxidative phosphorylation (KEGG Database) provides plausible mechanistic support for stress-adapted energy metabolism in melanized fungi.

While previous studies have examined DNA repair, melanin biosynthesis, and energy metabolism individually, our study provides a comparative, protein-level perspective that integrates these adaptive strategies across extremophilic bacteria and fungi. By annotating NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase, laccases, and PprA, we highlight how energy metabolism, pigment-mediated protection, and DNA repair may collectively contribute to survival under ionizing radiation. This perspective offers a framework that could inform future studies in bioremediation and astrobiology.

4.4. Integrated Survival Strategies

Radiation resistance emerges not from a single molecular defense but from a coordinated interplay of protective systems. These include (i) DNA repair mechanisms safeguarding genomic stability (Daly, 2012), (ii) melanin pigments acting as biochemical shields (Dadachova et al., 2007), and (iii) robust metabolic pathways that sustain energy-dependent recovery (Narumi, 2003).

Figure 2 illustrates this integrated framework, where DNA repair (PprA in

D. radiodurans), pigment shielding (laccases in

C. neoformans and

A. niger), and oxidative phosphorylation (Complex I in

C. sphaerospermum) collectively underpin microbial radiation tolerance. These interdependent systems demonstrate evolutionary convergence between bacterial and fungal extremophiles, optimizing survival in radiation-exposed ecosystems.

Figure 2.

Integrated strategies of radiation resistance in bacteria and fungi.

Figure 2.

Integrated strategies of radiation resistance in bacteria and fungi.

4.5. Implications for Bioremediation and Beyond

The molecular adaptations described here offer promising directions for biotechnology and astrobiology. Fungal melanins could serve as radiation-shielding biomaterials—for instance, in space agriculture, where melanin coatings might protect seeds or biological systems from cosmic radiation (Kunal et al., 2025). Similarly, the metabolic versatility of C. sphaerospermum (Averesch et al., 2022) may enable its application in self-regenerating bio-barriers for radioactive environments. Incorporating PprA or related DNA repair systems into synthetic or microbial consortia (Narumi et al., 2004) could enhance genome stability and resilience in engineered strains. Beyond environmental remediation, these insights hold potential for synthetic biology and genome engineering, where DNA repair proteins, laccases, and oxidative metabolism pathways may be harnessed to create radiation-tolerant organisms.

By integrating protein-level annotations across bacterial and fungal systems, this study presents a comparative molecular framework for radiation resistance. The synergy of DNA repair, pigment shielding, and metabolic adaptation defines the essence of microbial extremotolerance—shedding light on life’s resilience under the most hostile conditions and guiding translational applications in biotechnology, medicine, and space exploration.

5. Conclusion

This study provides a comparative, protein-level analysis of molecular strategies underlying radiation resistance in bacterial and fungal extremophiles. By annotating PprA from Deinococcus radiodurans, Laccase-1 from Cryptococcus neoformans, Laccase from Aspergillus niger, and NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain 4 from Cladosporium sphaerospermum, we outline how DNA repair, pigment-based protection, and energy metabolism act in a complementary manner to support survival under radiation stress. PprA provides a specialized mechanism for repairing double-strand DNA breaks, fungal laccases catalyze melanin polymerization conferring radioprotective benefits, and the Complex I subunit in C. sphaerospermum drives oxidative phosphorylation to supply energy for stress adaptation.

This comparative approach highlights both conserved strategies and species-specific adaptations, illustrating how evolutionary pressures shape complementary mechanisms across bacteria and fungi. These insights offer a conceptual framework for future studies in extremophile biology and potential applications in biotechnology, bioremediation, and astrobiology. Overall, the work emphasizes the importance of layered molecular strategies in microbial radiation survival and provides a reference point for exploring how extremotolerance can inspire translational research.

Author Contributions

Rofiqul Islam Nayem: Conceptualization, data collection, performing annotation, data analysis and manuscript writing.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Consent to Publish

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Ethics Declaration

Not applicable.

Clinical Trial Registration

Not applicable, as this study did not involve clinical trials.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Protein sequences used in this study were obtained from publicly accessible databases, including NCBI and UniProt, and all computational analyses (BLASTp, InterProScan, KEGG mapping) are fully reproducible using the methods described in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- Adachi, M., Hirayama, H., Shimizu, R., Satoh, K., Narumi, I., & Kuroki, R. (2014). Interaction of double-stranded DNA with polymerized PprA protein fromDeinococcus radiodurans. Protein Science, 23(10), 1349–1358. [CrossRef]

- Averesch, N. J. H., Shunk, G. K., & Kern, C. (2022). Cultivation of the Dematiaceous Fungus Cladosporium sphaerospermum Aboard the International Space Station and Effects of Ionizing Radiation. Frontiers in Microbiology, 13. [CrossRef]

- Azzam, E. I., Jay-Gerin, J.-P., & Pain, D. (2012). Ionizing radiation-induced metabolic oxidative stress and prolonged cell injury. Cancer Letters, 327(1-2), 48–60. [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E.W., Lipman, D.J. (1990) “Basic local alignment search tool.” J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410.

- Bateman, A., Martin, M.-J., Orchard, S., Magrane, M., Adesina, A., Ahmad, S., Bowler-Barnett, E. H., Hema Bye-A-Jee, Carpentier, D., Denny, P., Fan, J., Garmiri, P., Jose, L., Hussein, A., Alexandr Ignatchenko, Insana, G., Rizwan Ishtiaq, Joshi, V., Dushyanth Jyothi, & Swaathi Kandasaamy. (2024). UniProt: the Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2025. Nucleic Acids Research, 53(D1). [CrossRef]

- Blum, M., Andreeva, A., Florentino, L., Chuguransky, S., Grego, T., Hobbs, E., Pinto, B., Orr, A., Paysan-Lafosse, T., Ponamareva, I., Salazar, G., Bordin, N., Bork, P., Bridge, A., Colwell, L., Gough, J., Haft, D., Letunic, I., Llinares-López, F., & Marchler-Bauer, A. (2024). InterPro: the protein sequence classification resource in 2025. Nucleic Acids Research, 53(D1). [CrossRef]

- Bowater, R., & Doherty, A. J. (2006). Making Ends Meet: Repairing Breaks in Bacterial DNA by Non-Homologous End-Joining. PLoS Genetics, 2(2), e8. [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, G., da Cruz, I. B. M., & González-Gallego, J. (2015). Manganese superoxide dismutase and oxidative stress modulation. Advances in Clinical Chemistry, 68, 87–130. [CrossRef]

- Casadevall, A., Cordero, R., Bryan, R., Nosanchuk, J., & Dadachova, E. (2017). Melanin, radiation, and energy transduction in fungi. Microbiology Spectrum, 5(2). [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.-H., Yoon, S., Koh, Y. E., Seo, Y.-J., & Kim, K. P. (2020). Maintenance of genome integrity and active homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells. Experimental & Molecular Medicine, 52(8), 1220–1229. [CrossRef]

- Cortesão, M., de Haas, A., Unterbusch, R., Fujimori, A., Schütze, T., Meyer, V., & Moeller, R. (2020). Aspergillus niger Spores Are Highly Resistant to Space Radiation. Frontiers in Microbiology, 11. [CrossRef]

- Dadachova, E., Bryan, R. A., Huang, X., Moadel, T., Schweitzer, A. D., Aisen, P., Nosanchuk, J. D., & Casadevall, A. (2007). Ionizing Radiation Changes the Electronic Properties of Melanin and Enhances the Growth of Melanized Fungi. PLoS ONE, 2(5), e457. [CrossRef]

- Dadachova, E., & Casadevall, A. (2008). Ionizing radiation: how fungi cope, adapt, and exploit with the help of melanin. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 11(6), 525–531. [CrossRef]

- Dadachova, E., Bryan, R. A., Howell, R. C., Schweitzer, A. D., Aisen, P., Nosanchuk, J. D., & Casadevall, A. (2007). The radioprotective properties of fungal melanin are a function of its chemical composition, stable radical presence and spatial arrangement. Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research, 21(2), 192–199. [CrossRef]

- Daly, M. J. (2012). Death by protein damage in irradiated cells. DNA Repair, 11(1), 12–21. [CrossRef]

- Eisenman, H. C., & Casadevall, A. (2011). Synthesis and assembly of fungal melanin. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 93(3), 931–940. [CrossRef]

- Madeira, F., Park, Y. M., Lee, J., Buso, N., Gur, T., Madhusoodanan, N., Basutkar, P., Tivey, A. R. N., Potter, S. C., Finn, R. D., & Lopez, R. (2019). The EMBL-EBI search and sequence analysis tools APIs in 2019. Nucleic Acids Research, 47(W1), W636- W641. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, T., Sengupta, I., & Dhal, P. K. (2021). A new era of radiation resistance bacteria in bioremediation and production of bioactive compounds with therapeutic potential and other aspects: An in-perspective review. Journal of Environmental Radioactivity, 237, 106696. [CrossRef]

- Janusz, G., Pawlik, A., Świderska-Burek, U., Polak, J., Sulej, J., Jarosz-Wilkołazka, A., & Paszczyński, A. (2020). Laccase Properties, Physiological Functions, and Evolution. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(3), 966. [CrossRef]

- Jena, A. B., Samal, R. R., Bhol, N. K., & Duttaroy, A. K. (2023). Cellular Red-Ox system in health and disease: The latest update. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 162, 114606. [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.-W., Yang, D.-H., Kim, M.-K., Seo, H. S., Lim, S., & Bahn, Y.-S. (2016). Unraveling Fungal Radiation Resistance Regulatory Networks through the Genome-Wide Transcriptome and Genetic Analyses of Cryptococcus neoformans. MBio, 7(6). [CrossRef]

- Ishino, Y., & Issay Narumi. (2015). DNA repair in hyperthermophilic and hyperradioresistant microorganisms. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 25, 103–112. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M., & Sato, Y. (2019). KEGG Mapper for inferring cellular functions from protein sequences. Protein Science, 29(1), 28–35. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y., & Kawashima, M. (2021). KEGG mapping tools for uncovering hidden features in biological data. Protein Science, 31(1), 47–53. [CrossRef]

- Kierans, S. J., & Taylor, C. T. (2024). Glycolysis: A multifaceted metabolic pathway and signalling hub. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 300(11), 107906–107906. [CrossRef]

- Herrling, T., Jung, K., & Fuchs, J. (2008). The role of melanin as protector against free radicals in skin and its role as free radical indicator in hair. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 69(5), 1429–1435. [CrossRef]

- Kricka, L. J., & Park, J. Y. (2014). Assay Principles in Clinical Pathology. Pathobiology of Human Disease, 3207–3221. [CrossRef]

- Kunal, S., Bhanushali, S., Raghukumar, S., & Dadachova, E. (2025). Melanin from the fungus Gliocephalotrichum simplex protects seeds from the effects of exposure to gamma radiation. Scientific Reports, 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Liu, F., Li, N., & Zhang, Y. (2023). The radioresistant and survival mechanisms of Deinococcus radiodurans. Radiation Medicine and Protection, 4(2). [CrossRef]

- Marcotulli, B. (2025, February). A Black Fungus Might Be Healing Chernobyl By Drinking Radiation. Maker Faire Rome. https://makerfairerome.eu/en/blog/a-black-fungus-might-be-healing-chernobyl-by-drinking-radiation/.

- Makarova, K. S., Aravind, L., Wolf, Y. I., Tatusov, R. L., Minton, K. W., Koonin, E. V., & Daly, M. J. (2001). Genome of the Extremely Radiation-Resistant Bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans Viewed from the Perspective of Comparative Genomics. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 65(1), 44–79. [CrossRef]

- Malo, M. E., Bryan, R. A., Shuryak, I., & Dadachova, E. (2018). Morphological changes in melanized and non-melanized Cryptococcus neoformans cells post exposure to sparsely and densely ionizing radiation demonstrate protective effect of melanin. Fungal Biology, 122(6), 449–456. [CrossRef]

- Markéta Kulišová, Rabochová, M., Lorinčík, J., Maťátková, O., Tomáš Brányik, Hrudka, J., Scholtz, V., & Kolouchová, I. J. (2024). Comparative assessment of UV-C radiation and non-thermal plasma for inactivation of foodborne fungal spores suspension in vitro. RSC Advances, 14(24), 16835–16845. [CrossRef]

- Minton, K. W. (1994). DNA repair in the extremely radioresistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans. Molecular Microbiology, 13(1), 9–15. [CrossRef]

- Narumi, I. (2003). Unlocking radiation resistance mechanisms: still a long way to go. Trends in Microbiology, 11(9), 422–425. [CrossRef]

- Narumi, I., Satoh, K., Cui, S., Funayama, T., Kitayama, S., & Watanabe, H. (2004). PprA: a novel protein from Deinococcus radiodurans that stimulates DNA ligation. Molecular Microbiology, 54(1), 278–285. [CrossRef]

- Pacelli, C., Bryan, R. A., Onofri, S., Selbmann, L., Shuryak, I., & Dadachova, E. (2017). Melanin is effective in protecting fast and slow growing fungi from various types of ionizing radiation. Environmental Microbiology, 19(4), 1612–1624. [CrossRef]

- Pritideepa Behera, Debnath, D., & Mohapatra, C. (2025). Black Fungus that Eats Radiation for Breakfast: The Science behind Nature’s Super Survivor. 4(8), 725, 726, 727.

- Repar, J., Cvjetan, S., Slade, D., Radman, M., Zahradka, D., & Zahradka, K. (2010). RecA protein assures fidelity of DNA repair and genome stability in Deinococcus radiodurans. DNA Repair, 9(11), 1151–1161. [CrossRef]

- Shunk, G. K., Gomez, X. R., & Averesch, N. J. H. (2020). A Self-Replicating Radiation-Shield for Human Deep-Space Exploration: Radiotrophic Fungi can Attenuate Ionizing Radiation aboard the International Space Station. BioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Travers, S. (2024, November 2). This Black Fungus Might Be Healing Chernobyl By Drinking Radiation—A Biologist Explains. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/scotttravers/2024/11/02/.

- Goran Slivšek, Mijač, S., Dolanc, I., Marija Fabijanec, Silvija Petković, Mautner, R., Lončarek, K., Josip Kranjčić, Alenka Boban Blagaić, Marinović, M., Vitale, K., Verbanac, D., Miran Čoklo, & Jadranka Vraneković. (2025). Oxidative Stress and Down Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Antioxidants, 14(7), 816–816. [CrossRef]

- Waters, R. (2006). Maintaining genome integrity. EMBO Reports, 7(4), 377–381. [CrossRef]

- Willers, H., Dahm-Daphi, J., & Powell, S. N. (2004). Repair of radiation damage to DNA. British Journal of Cancer, 90(7), 1297–1301. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2020, October 26). Radiation: Ionizing Radiation. Www.who.int. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/radiation-ionizing-radiation.

- Zakaria, L. (2024). An Overview of Aspergillus Species Associated with Plant Diseases. Pathogens, 13(9), 813–813. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).