1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO),

Mycobacterium tuberculosis and tuberculosis (TB) was the world’s second leading cause of death from a single infectious agent, after coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in 2022, and caused almost twice as many deaths as HIV/AIDS. The reported global number of people newly diagnosed with TB was 7,5 million in 2022. This is the highest number since WHO began global TB monitoring in 1995. Globally, an estimated 410,000 people (95% UI: 370,000–450,000) developed multidrug-resistant (MDR, defined as TB resistant to rifampicin and isoniazid) or rifampicin-resistant TB (RR-TB) in 2022 [

1].

Urgent action is required to end the global TB epidemic by 2030, a goal that has been adopted by all Member States of the United Nations and the WHO. The discovery, development and rapid uptake of new tools, interventions and strategies are among the key areas of focus in TB treatment. Priorities include a vaccine to reduce the risk of infection and new drug treatment to combat MDR-TB [

1]. This requires new anti-TB agents with a new mechanism of action for use in TB complex therapy.

The presence in the structure of two N-oxide fragments makes quinoxaline 1,4-dioxides (QdNOs) prospective compounds with wide spectrum of biological properties, including antitumor, antibacterial, antiparasitic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and herbicidal activities [

2]. In recent studies, some QdNOs’ derivatives have also exhibited excellent inhibitory activity against

M. tuberculosis, indicating the great interest of this scaffold for the development of new anti-TB drugs [

3,

4,

5]. The high biological activity of QdNOs is provided by the oxidation of nitrogen in a quinoxaline ring [

6]. Additionally, QdNOs are species that undergo a bioreductive process under the hypoxic conditions found in TB granulomas, where nonreplicating persistent forms of

M. tuberculosis can survive, resulting in long treatments and the risk of drug resistance development [

7].

We have previously identified a lead compound 7-chloro-2-(ethoxycarbonyl)-3-methyl-6-(piperazin-1-yl)quinoxaline 1,4-dioxide-1 (LCTA-3368) in a screen of QdNOs (

Figure S1) library on

Mycobacterium smegmatis [

8], a model organism widely used to screen anti-TB drug candidates [

9,

10]. LCTA-3368 exhibited strong inhibitory activity on both

M. smegmatis (4 μg/ml) and

M. tuberculosis (1.25 μg/ml). We showed that LCTA-3368 induces unique non-synonymous mutations in a variety of genes in spontaneous drug-resistant

M. smegmatis mutants, although we were unable to identify a clearly pronounced biotarget within the cell [

8]. One possible mechanism of action for quinoxaline 1,4-dioxide derivatives is the direct induction of single- and double-stranded DNA breaks in bacteria, which could account for the numerous mutations observed in

M. smegmatis strains [

11].

Transcriptomic studies, including analysis of complete RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), are currently becoming a powerful tool for establishing additional mechanisms of action of antimicrobials, including anti-tuberculosis drugs, through the bacterial transcriptional response to the presence of the drug [

12]. In our previous study we implied the transcriptomic analysis to reveal the impact on iron metabolism of imidazo tetrazines, a set of compounds for which it was not possible to determine a biotarget using the classical method of generating spontaneous drug-resistant mutants [

13].

In this study we describe the transcriptomic profile of M. smegmatis treated by LCTA-3368 in incubation time-depended (30 min and 90 min) and dose-depended (1/4 × MIC, 1/2 × MIC and 1 × MIC) manner to get an insight in the gradual changes in the bacterial response to exposure to this drug. We observed significant changes in the gene expression of those involved in DNA repair and replication processes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microbial Cultures and Growth Conditions

Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2 155 was grown in Middlebrook 7H9 medium (Himedia, India) supplemented with oleic albumin dextrose catalase (OADC, Himedia, India), 0.1% Tween-80 (v/v), and 0.4% glycerol (v/v) while soyabean-casein digest agar (M290, Himedia, India) and Middlebrook 7H11 agar (Himedia, India) supplemented with OADC were used as the solid media. Culture in liquid medium was incubated in the Multitron incubator shaker (Infors HT, Bottmingen-Basel, Switzerland) at 37°C and 250 rpm.

For drug exposure assay and transcriptomic analysis,

M. smegmatis mc2 155 was inoculated from the agarized plates in 7H9 medium and grown until OD

600 = 2.5 (two nights) to obtain a stable liquid culture without clumps, diluted in the proportion 1:200 and cultured overnight until OD

600 = 2, then diluted in the proportion of 1:10 in fresh medium (to an approximate OD

600 = 0.2). LCTA-3368 100 × stocks were prepared in DMSO (ACS Grade, Solon, India) and added to the bacterial cultures to a final concentration corresponding to 1/4 × MIC (1 μg/ml), 1/2 × MIC (2 μg/ml), and 1 × MIC (4 μg/ml) in 7H9 OADC medium. The same volume of DMSO was added to the control samples (1% v/v). Bacterial cultures were incubated for 30 min and 90 min (1/6 and 1/2 of the cell division time, respectively [

14]) at 37°C and 250 rpm and proceeded to RNA extraction. The experiments were carried in three biological replicates.

2.2. Total RNA Extraction

RNA was extracted using the MagMAX mirVana Total RNA Isolation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lithuania) on the KingFisher Flex Purification System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was treated with DNase using Turbo DNA-Free Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the 50 μl volume, and further purified using Agencourt RNAClean XP (Beckman Coulter, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The total amount of RNA was measured with the Quant-iT Ribogreen RNA assay kit (ThermoFisher Scientific), and the quality of extracted RNA was checked by Agilent Bioanalyzer on Agilent RNA 6000 Pico Chips (Agilent Technologies, United States).

2.3. Library Preparation and RNA Sequencing

For the preparation of transcriptomic libraries, 250 ng of total RNA was taken as input. Selective removal of ribosomal RNA was performed using the Ribo-Zero Plus rRNA Depletion Kit (Illumina, USA), followed by library preparation employing the KAPA RNA Hyper Kit (Roche, Switzerland), according to the manufacturer protocol. Subsequent RNA purification steps involved the application of RNA Clean XP magnetic beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, USA), with final library purification conducted using Agencourt AMPure XP magnetic beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, USA). The size distribution and quality of the libraries were assessed using the Agilent High Sensitivity DNA kit (Agilent Technologies, USA), while the library concentration was quantified using the Quant-iT DNA Assay Kit, High Sensitivity (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Finally, equimolar quantities of all libraries (12 pM) were sequenced by a high throughput run on the Illumina HiSeq using 2 × 100 bp paired-end reads and a 5% Phix spike-in control. RNA-seq read data were deposited to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under accession number PRJNA1091547.

2.4. Bioinformatics Analysis

Quality control of the raw sequencing data was performed using FastQC (v.0.11.9) [

15], individual reports were merged with MultiQC (v.1.9) [

16]. Adapters and low-quality reads were removed using Trimmomatic (v.0.39) [

17]. HISAT2 (v.2.2.1) [

18] was used to map trimmed reads to the reference

M. smegmatis mc2 155 genome (CP000480.1). Mapping quality and coverage along genes were assessed with QualiMap (v.2.2.2) [

19]. Mapped reads were assigned to genes with featureCounts (v.2.0.1) [

20]. Differential gene expression (DGE) analysis was performed using the edgeR (v.3.30.3) [

21] for R (v.4.0.2) [

22] . Genes with a false discovery rate (FDR) cutoff of 0.05 and fold change (FC) log2FC ≤ -1, or log2FC ≥1 were considered to be differentially expressed. Plots were generated within Python 3 (v.3.12.6) [

23] using matplotlib (v.3.9) [

24] and numpy (v.2.1.1) [

25] packages. Further functional enrichment analysis of the GO categories and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) was performed using the GOpiscator (v.0.1.5) [

26], categories were considered enriched with p ≤ 0.05. Heatmap plots were generated within Python 3 (v.3.12.6) using the Seaborn (v.0.13) package. Bubble chart based on GOpiscator (v.0.1.5) [

26] results data for DEGs was generated within Python 3 (v.3.12.6) using matplotlib (v.3.9) and numpy (v.2.1.1) packages.

3. Results

3.1. Whole-Transcriptome Analysis

A total of 32 RNA-seq libraries were generated to comprehensively characterize the transcriptional profile of M. smegmatis following LCTA-3368 treatment at different concentrations and time points, resulting in 167,144,850 raw reads. Following the removal of useless reads 165,637,398 clean reads were retained, representing an average retention rate of 98,75 – 99,96% of the raw reads. Average length of bases mapped per library is 256,321,391 bp.

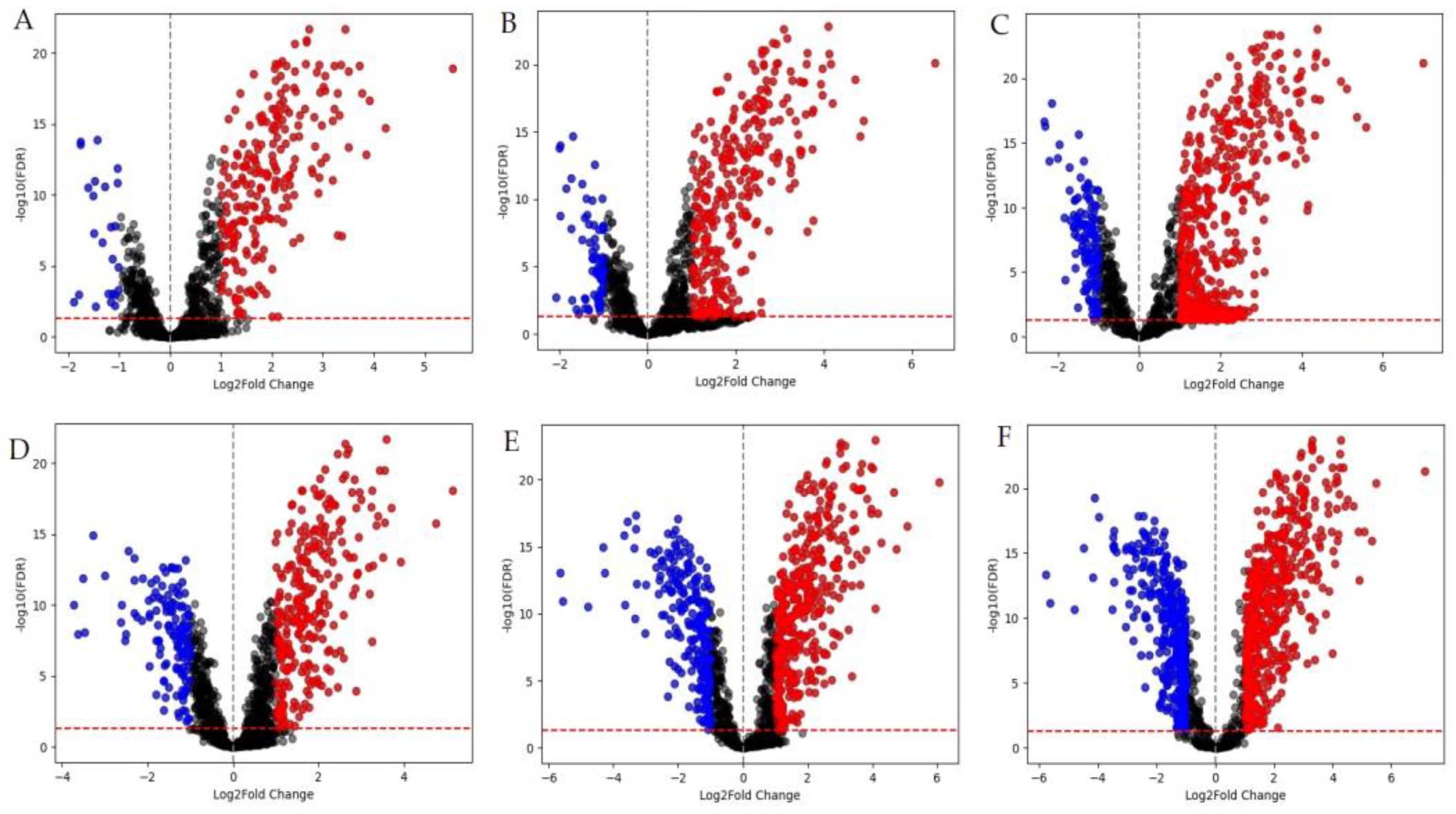

A total of 1,223 DEGs with at least a two-fold expression level change were obtained (

Table S1). Among them 767 genes were upregulated. Of these, 209 were expressed at all points of experiment. 456 DEGs were downregulated, 5 of them were expressed at all points of experiment.

Figure 1.

M. smegmatis differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Red dots are positively regulated DEGs (log2FC ≥1); blue dots are negatively regulated DEGs (log2FC ≤ -1). Graphs A-C represent volcano plots for samples that were incubated for 30 minutes, while graphs D-F are for samples that were incubated for 90 minutes in the presence of LCTA-3368 at 1/4 × MIC (A, D), 1/2 × MIC (B, E), and 1 × MIC (C, F).

Figure 1.

M. smegmatis differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Red dots are positively regulated DEGs (log2FC ≥1); blue dots are negatively regulated DEGs (log2FC ≤ -1). Graphs A-C represent volcano plots for samples that were incubated for 30 minutes, while graphs D-F are for samples that were incubated for 90 minutes in the presence of LCTA-3368 at 1/4 × MIC (A, D), 1/2 × MIC (B, E), and 1 × MIC (C, F).

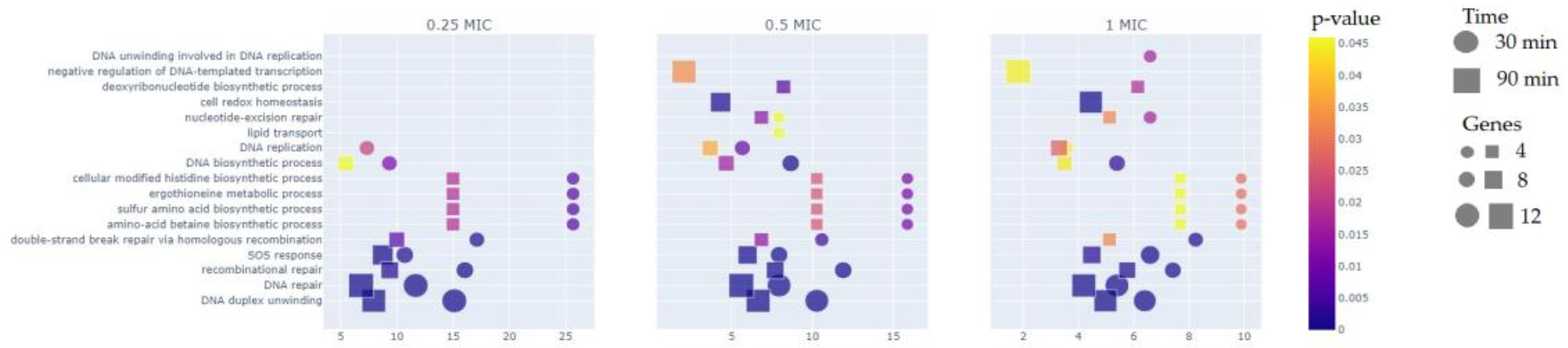

The comparison of different MICs groups reveals that more than a half of DEGs is represented within 90 minutes immersion in the test compound, especially for 1/2 × MIC and 1 × MIC groups. As for GO-analysis (

Figure 2), about 30% of DEGs in average belong to DNA repair pathway (GO:0006281) and DNA duplex unwinding pathway (GO:0032508) for both 30 and 90 minutes at all three groups (1/4 × MIC, 1/2 × MIC, 1 × MIC). For a 90 minute time point we can see negative regulation of DNA-templated transcription (GO:0045892) for 1/2 × MIC, and 1 × MIC groups, which was not observed in the 1/4 × MIC group. The same pattern is true for the nucleotide-excision repair (GO:0006289) and cell redox homeostasis (GO:0045454) pathways. Differential expression of genes in the lipid transport pathway (GO:0006869) was detected only for 30 minutes - 1/2 × MIC group, while those related to the DNA unwinding involved in DNA replication pathway (GO:0006268) were detected only in the 30 minutes - 1 × MIC group.

Since we have identified a large number of DEGs, we decided to introduce a dose-dependence criterion and analyze the results obtained based on this criterion. The main criteria for dose-dependence is a minimum difference 0.5 for upregulated genes, and -0.5 for the downregulated ones in the log2FC at 1/4 × MIC, 1/2 × MIC, 1 × MIC on each step at least. We selected the DEGs meeting this criterion at 30 and 90 minute timepoints, they will be referred as “dose-dependent” further. This difference was examined separately for 30 and 90 minutes, and also simultaneously for both times. So DEGs can be dose-dependent for 30 or 90 minutes or for both times. The next criteria is the change of log2FC in one direction relative to the increase in the concentration of LCTA-3368. DEGs satisfying all these conditions are called “dose-dependent”.

3.2. Functional Groups of Differentially Expressed Genes

The analysis revealed 42 DEGs participating in DNA repair, 86 transcriptional regulator DEGs, indicating the strength of the response to LCTA-3368, 91 DEGs encoding proteins with oxidoreductase functions, 55 DEGs whose products are involved in transport processes, 57 DEGs of fatty acid, amino acid metabolism and TCA cycle, 13 DEGs of transposases (

Table S2).

3.2.1. Reparation Genes

42 DEGs were identified as related to the DNA reparation pathway, and included all the available systems in mycobacteria: double-strand breaks (DSBs) repair, homologous recombination (HR), nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ), single-chain annealing (SSA), nucleotide excision repair (NER), SOS-system (SOS) (

Table S3). All the DNA repair DEGs were upregulated throughout the experiment, confirming the vast DNA damage caused to bacterial cells by LCTA-3368 [

27].

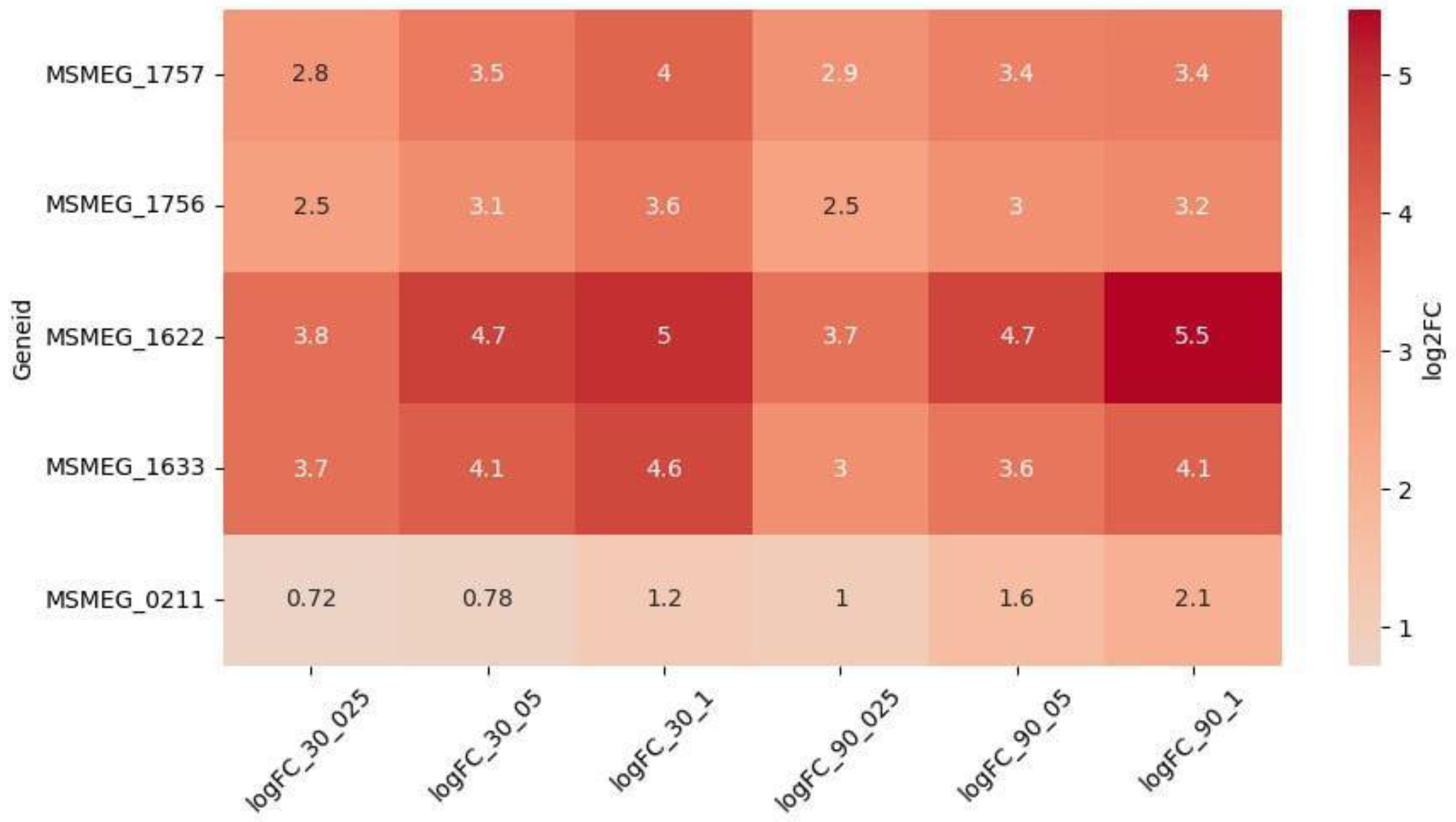

However, 5 genes were upregulated in a dose-dependent manner (

Figure 3):

MSMEG_1622 (DNA Repair) and

MSMEG_1633 (SOS) were the most upregulated and dose-dependent at both timepoints,

MSMEG_1756 and

MSMEG_1757 (NER) at 30 minutes, while

MSMEG_0211 (NER) at 90 minutes. Interestingly, the upregulation of

MSMEG_0211 increased at 90 minutes, as compared to 30 minutes, while the expression of other dose-dependent DEGs stayed the same, or slightly decreased at 90 minutes.

3.2.2. Oxidoreductases

The largest group of DEGs (N = 91, 69 upregulated and 22 downregulated DEGs) consisted of those encoding proteins with predicted oxidoreductase activity of the following families: SDR family, Nitroreductase superfamily, VOC family, LLM class flavin-dependent oxidoreductase, FAD-binding oxidoreductases. It has been previously shown that bacterial oxidoreductases may be involved in the metabolic activation of quinoxalines to generate free radicals that can inhibit synthesis and cause DNA damage [

28].

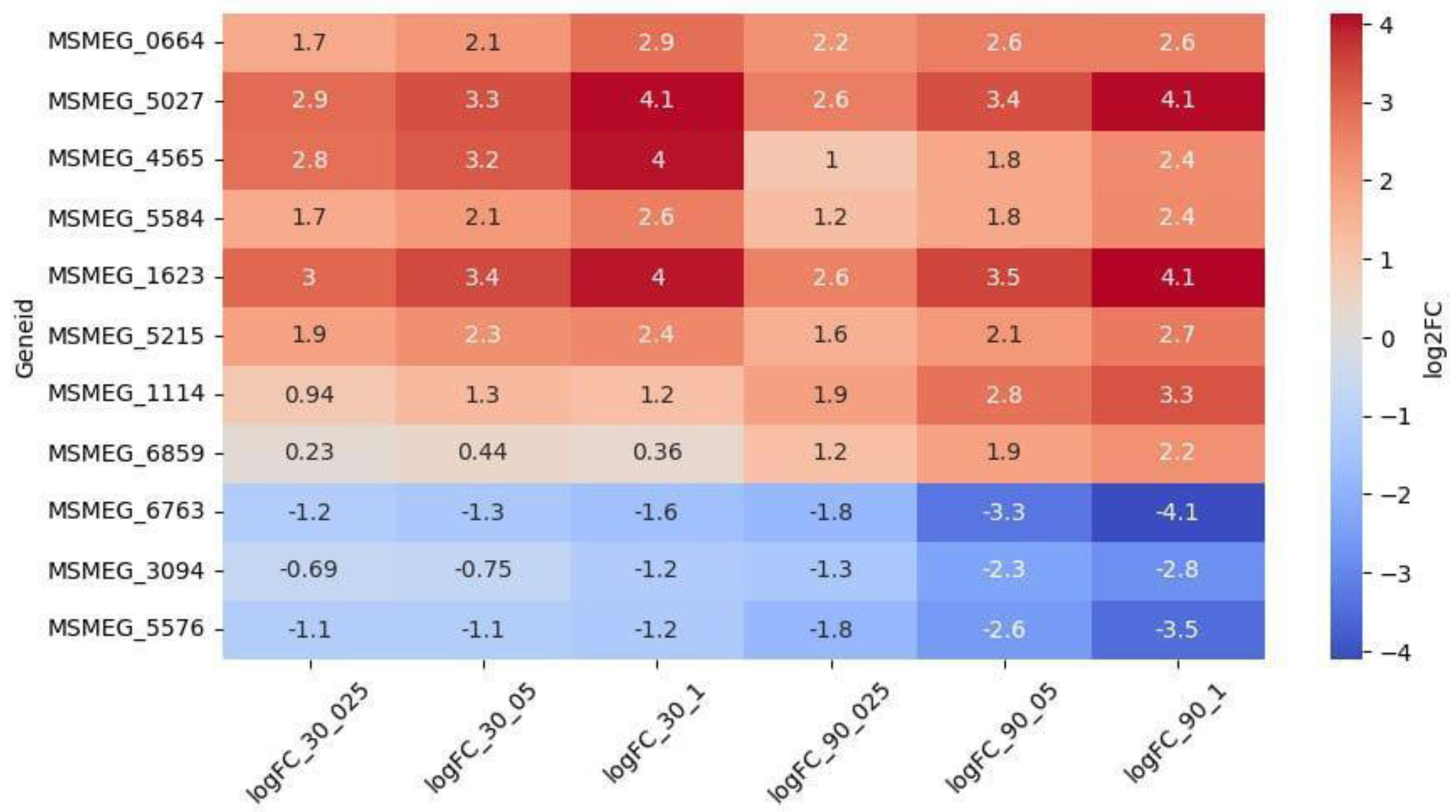

Among the 69 upregulated genes, 8 were dose-dependent (

Figure 4). Genes

MSMEG_5027 (encoding a VOC family protein) and

MSMEG_1623 (encoding an SDR family oxidoreductase) were the highest upregulated and the only dose-dependent at both timepoints. Genes

MSMEG_3094,

MSMEG_5576 and

MSMEG_6763 were downregulated throughout the experiment, and dose-dependent at 90 minutes.

Other Genes

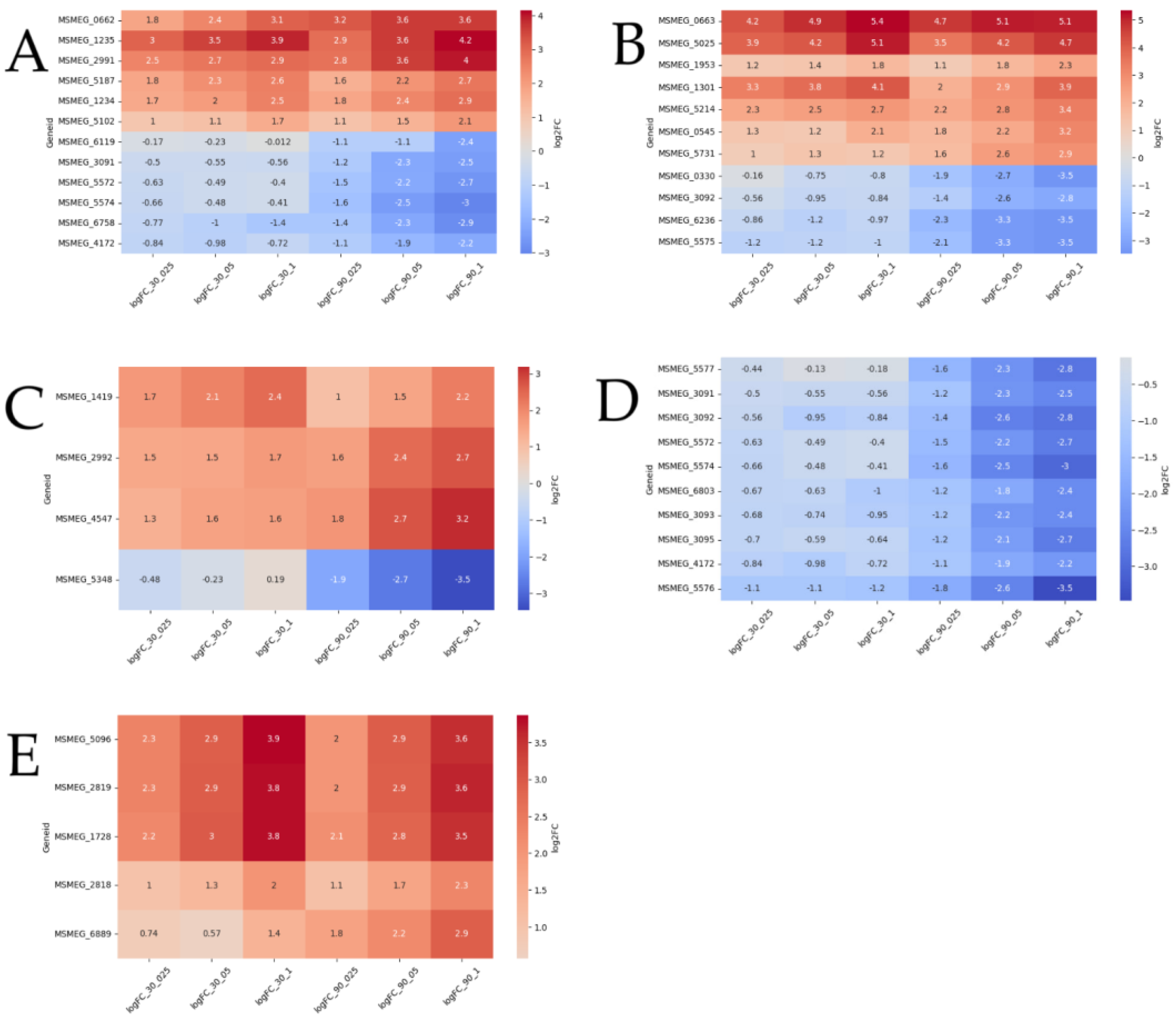

Differential expression of 55 transport genes was detected, of which 23 genes are upregulated and 32 are downregulated. Of them 12 are dose-dependent (

Figure 5A). Genes

MSMEG_2991, MSMEG_5187 (multidrug efflux MFS transporters),

MSMEG_5102, MSMEG_1234, MSMEG_0662 (ABC transporters) and

MSMEG_1235 (SulP transporter) were upregulated in a dose-dependent manner at both timepoints.

MSMEG_3091, MSMEG_4172, MSMEG_5572, MSMEG_5574 (carbohydrate ABC transporters),

MSMEG_6758 (aquaporin) and

MSMEG_6119 (sulfite exporter) were upregulated in a dose-dependent manner only at 90 minutes.

Among the 86 DEGs of transcriptional regulators 12 DEGs are dose-dependent (

Figure 5B).

MSMEG_0663, MSMEG_5025 (TetR),

MSMEG_1953 (WhiB7),

MSMEG_1301 (LuxR) and

MSMEG_5214 (sigma-70) upregulated at both timepoints. DEGs

MSMEG_0545 (LuxR) and

MSMEG_5731 (GntR) upregulated at 90 minutes.

MSMEG_0663 (TetR) was the most upregulated and dose-dependent at both timepoints. 4 DEGs were downregulated at 90 minutes:

MSMEG_0330 (LuxR),

MSMEG_3092 (sugar-binding),

MSMEG_6236 (MnoR),

MSMEG_5575 (MarR).

18 DEGs Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase/oxidase [

29], 12 DEGs enoyl-CoA hydratase/isomerase (Crotonase) genes [

30], DEG phytanoyl-CoA dioxygenase, 11 DEGs AMP-dependent synthetase/ligase [

29], DEGs CoA-transferase family I and III [

31], associated with fatty acid degradation and transport. 3 DEGs were upregulated in a dose-dependent manner at 90 minutes:

MSMEG_2992, MSMEG_4547 (acyl-CoA dehydrogenase) and

MSMEG_1419 (phytanoyl-CoA dioxygenase);

MSMEG_5348 (long-chain-fatty-acid--CoA ligase) was downregulated the same at 90 minutes (

Figure 5C).

56 DEGs were associated with carbohydrates metabolism and transport. 9 of them were dose dependent downregulated at 90 minutes (

Figure 5D).

MSMEG_5572, MSMEG_5574, MSMEG_3091, MSMEG_4172, MSMEG_6803 (sugar ABC transporters genes),

MSMEG_5577 (fructokinase gene),

MSMEG_3092 (sugar-binding transcriptional regulator gene),

MSMEG_3093,

MSMEG_3095 (FGGY carbohydrate kinase genes).

MSMEG_5576 (D-mannonate oxidoreductase gene) was the highest downregulated at both timepoints.

Among the 13 DEGs of transposases 4 upregulated in a dose-dependent manner at both timepoints MSMEG_1728, MSMEG_2819, MSMEG_5096 and MSMEG_2818. DEG of transposase MSMEG_6889 was upregulated only at 90 minutes.

4. Discussion

Currently, there is a need for an approach to search for new targets and new mechanisms of action of drugs against

M. tuberculosis. Quinoxaline 1,4-di-N-oxides belong to the heterocyclic family of benzodiazepines with N–O groups located at the 1- and 4-positions. The reducing potential of QdNO, which can generate free radical intermediates, contributes to their antibacterial action. It is known that QdNO exhibits high inhibitory activity

in vitro against various pathogens, including

Mycobacteria [

3].

The approach of our study, involving the analysis of 3 subinhibitory doses at two timepoints, aimed to elucidate the early defensive response of the bacterial cell to LCTA-3368 on the transcriptomic level. Thus, we expect the expression of genes able to provide any protective effect to the bacterial cell to be upregulated, while that of the genes, contributing to LCTA-3368 action, to do the opposite.

A number of studies have confirmed the mechanism of antibacterial action of QdNOs associated with the formation of free radicals during bioremediation, leading to DNA damage [2, 27, 32, 33].

M. smegmatis as well as

M. tuberculosis has many pathways for DNA reparation: repair of double-strand breaks (DSBs) homologous recombination (HR), nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ), and single-chain annealing (SSA) mechanism [

34]. We observed the upregulation of 42 DEGs involved in DNA repair processes, however only 5 of them did so in a strict dose-dependent manner.

The activation of SOS-reparation is a typical response of mycobacteria to antibiotics-caused stress, and is marked by increased transcription of error-prone DNA polymerases, which include DNA polymerase III (the highly upregulated

MSMEG_1633 in our experiment). The error-prone polymerases cause additional mutations, which can grant the bacterial cell drug-resistance. The DEG of error-prone DNA polymerase belonging to the Y family (

MSMEG_1622) is even more upregulated. Its expression was shown to increase in prokaryotes under unfavorable conditions, which promotes adaptive mutagenesis [

35].

Mycobacteria have an additional mechanism of DNA damage induction, namely the nucleotide excision repair (NER).Under NER pathway, genomic damage is repaired by incisions in regions bordering the damaged DNA, resulting in the excision of an oligonucleotide rather than a single base. This system can recognize a wide range of damaged bases using endonucleases with lower specificity. This pathway includes the three components ABC excinuclease, DNA helicase II

uvrD [

36]. Gene expression analysis revealed that

M. tuberculosis appears to depend on uvrB for defense against nitrosative stress. In the multi-step NER pathway the damage recognition and subsequent endonucleolytic reactions are carried out by the coordinated action of the UvrA, UvrB and UvrC proteins. In MTB, as observed in other bacteria, the NER cascade begins with formation of a macromolecular complex between UvrA and UvrB proteins that search for damaged sites inside DNA [

37]. Crosslink repair DNA glycosylase ycaQ is also involved in the excision repair process [

38]. Mycobacterial cells contain apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease IV, which plays a dominant role in protecting mycobacterial DNA from oxidative stress. Class II apurinic/apyrimidinic-endonuclease/3'-5' exonuclease III acts on base sites of damaged DNA and also as DNA-3-methyladenine glycosylase(tag) takes part in excision repair under oxidative stress [

39].

Mobile genetic elements (MGEs) make an additional contribution to the mutagenesis process [

40]. Transposases are key drivers of the MGEs. Out of 13 DEGs, identified as encoding transposases, 5 were upregulated in a dose-dependent manner. Additional mutations introduced by the transposition of MGEs under drug pressure, may increase the rate of drug resistance emergence [

41].

The broad upregulation of DNA-repair systems in our experiment is an additional confirmation of the suggested mode of action of QdNOs through DNA damage [2, 32]. The dose-dependent upregulation of mutagenic systems (error-prone polymerases, NER pathway, transposases), on the other hand, explains the numerous mutations in the LCTA-3368 resistant mutants [

8].

Oxidoreductases were shown to be essential for bioreductive activation of QqNOs [

42]. We observed 3 genes encoding proteins with oxidoreductase activity being downregulated in a dose-dependent manner: alpha/beta hydrolase fold (

MSMEG_6763), D-mannonate oxidoreductase (

MSMEG_5576) and oxidoreductase, zinc-binding dehydrogenase (

MSMEG_3094). We suggest that these 3 oxidoreductases are the top-contributors to LCTA-3368 activation.

On the other hand, 8 genes encoding proteins of different families with oxidoreductase activity were upregulated in a dose-dependent manner and 3 of them had the maximum level of differential expression compared to the rest: SDR family oxidoreductase MSMEG_1623, aldo/keto reductase MSMEG_4565, VOC family protein MSMEG_5027. MSMEG_4565 is maximally upregulated at 30 minutes of treatment LCTA-3368, while the rest at both 30 and 90 minutes. Apart of bioreductive activation of QdNOs, oxidoreductases are involved in many other cellular redox processes [43-46], involving various interactions and transfer of active forms of nitrogen and oxygen. The overexpression of these genes might show that they are primarily involved in the neutralization of free radicals, produced by exposure to LCTA-3368, thus providing a protective effect to bacterial cells.

In previous work, we obtained a set of strains resistant to 4 x MIC LCTA-3368, with multiple mutations in each [

8]. Using reverse genetics, we confirmed that resistance to LCTA-3368 is conferred by mutations in the genes encoding a pyruvate synthase (

MSMEG_4646), ferredoxin (

MSMEG_5122) and the transcriptional repressor MSMEG_1380, leading to the overexpression of the MmpS5-MmpL5 efflux system, which acts as an MDR-pump [

47]. We did not observe significant change in the expression of the MmpS5-MmpL5 system, though other MDR transporter genes (

MSMEG_3815, MSMEG_5187, MSMEG_2991) were overexpressed, suggesting their contribution to LCTA-3368 efflux.

Finally, we observed downregulation of genes involved in lipid and carbohydrate transport, amino acid biosynthetic process, that indicates the attenuation of metabolic processes even after 90 minutes of treatment with LCTA-3368 and the further death of M.smegmatis.

5. Conclusions

The QdNO LCTA-3368 creates stress conditions of oxidative and/or nitrosative origin, resulting in a vast transcriptomic response. DNA reparation systems, primarily SOS-response and NER, appear to be the main means of damage control in mycobacterial cells subjected to a QdNO, introducing along the way mutations, which can result in drug resistance. Genes encoding proteins with oxidoreductase activity are also differentially expressed in a dose-dependent manner, allowin to differentiate oxidoreductase in the ones activating LCTA-3368 (downregulated), and those presumably capable of deactivating its active metabolites. Our study will allow us to move on to the targeted synthesis of more specific compounds of the quinoxaline 1,4-dioxide (QdNO).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

O.B.B. and O.O.G. contributed equally to this work. Conceptualization, O.B.B., A.A.V., D.A.M.; methodology, O.B.B., O.O.G.; investigation, O.B.B, O.O.G., S.G.F., S.V.S., N.I.K., K.M.K., V.A.V., D.A.B.; resources, A.A.V., D.A.M., V.N.D.; data curation, R.A.I., E.A.S; writing—original draft preparation, O.O.G., O.B.B.; writing—review and editing, O.B.B., D.A.M., D.A.R., E.A.S.; visualization, O.O.G.; supervision, O.B.B., D.A.M., V.N.D.; project administration, A.A.V., D.A.M.; funding acquisition, D.A.M., A.A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the RUDN University Scientific Projects Grant System, project № 202760-2-000 and State assignment from the Ministry of Science of the Russian Federation №0092-2022-0003. The work of Rustem Ilyasov was conducted under the IDB RAS Government basic research program in 2024 No. 0088-2024-0009.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Andrey Shchekotikhin of the Gause Institute of New Antibiotics, for kindly providing LCTA-3368 for the research. Sequenсing was performed using the core facilities of the Lopukhin FRCC PCM “Genomics, proteomics, metabolomics” (

http://rcpcm.org/?p=2806).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Global Tuberculosis Report 2023 Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2023.

- Cheng, G.; Sa, W.; Cao, C.; Guo, L.; Hao, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Yuan, Z. Quinoxaline 1,4-Di-N-Oxides: Biological Activities and Mechanisms of Actions. Front Pharmacol 2016, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanetti, S.; Sechi, L.A.; Molicotti, P.; Cannas, S.; Bua, A.; Deriu, A.; Carta, A.; Paglietti, G. In Vitro Activity of New Quinoxalin 1,4-Dioxide Derivatives against Strains of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis and Other Mycobacteria. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2005, 25, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, M.A.; Montoya, M.E.; Jaso, A.; Zarranz, B.; Tirapu, I.; Aldana, I.; Monge, A. Antimycobacterial Activity of New Quinoxaline-2-Carbonitrile and Quinoxaline-2-Carbonitrile 1,4-Di-N-Oxide Derivatives. Pharmazie 2001, 56, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villar, R.; Vicente, E.; Solano, B.; Pérez-Silanes, S.; Aldana, I.; Maddry, J.A.; Lenaerts, A.J.; Franzblau, S.G.; Cho, S.-H.; Monge, A.; et al. In Vitro and in Vivo Antimycobacterial Activities of Ketone and Amide Derivatives of Quinoxaline 1,4-Di-N-Oxide. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008, 62, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, P.W.; Scamehorn, R.G.; Hollstein, U.; Ryan, M.D.; Kovacic, P. Cyclic Voltammetry of Phenazines and Quinoxalines Including Mono- and Di-N-Oxides. Relation to Structure and Antimicrobial Activity. Chem Biol Interact 1986, 60, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, G.; Kotandeniya, D.; Daniels, J.S.; Barnes, C.L.; Gates, K.S. Enzyme-Activated, Hypoxia-Selective DNA Damage by 3-Amino-2-Quinoxalinecarbonitrile 1,4-Di-N-Oxide. Chem Res Toxicol 2004, 17, 1399–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolova, S.G.; Vatlin, A.A.; Maslov, D.A.; Yusuf, B.; Buravchenko, G.I.; Bekker, O.B.; Klimina, K.M.; Smirnova, S.V.; Shnakhova, L.M.; Malyants, I.K.; et al. Novel Derivatives of Quinoxaline-2-Carboxylic Acid 1,4-Dioxides as Antimycobacterial Agents: Mechanistic Studies and Therapeutic Potential. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2023, 16, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.B. Development of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Whole Cell Screening Hits as Potential Antituberculosis Agents. J Med Chem 2013, 56, 7755–7760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.M. Uptake of Carbon Monoxide and Hydrogen at Environmentally Relevant Concentrations by Mycobacteria†. Appl Environ Microbiol 2003, 69, 7266–7272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junnotula, V.; Sarkar, U.; Sinha, S.; Gates, K.S. Initiation of DNA Strand Cleavage by 1,2,4-Benzotriazine 1,4-Dioxide Antitumor Agents: Mechanistic Insight from Studies of 3-Methyl-1,2,4-Benzotriazine 1,4-Dioxide. J Am Chem Soc 2009, 131, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briffotaux J, Liu S, Gicquel B. Genome-Wide Transcriptional Responses of Mycobacterium to Antibiotics. Front Microbiol. [CrossRef]

- Vatlin, A.A.; Shitikov, E.A.; Shahbaaz, M.; Bespiatykh, D.A.; Klimina, K.M.; Christoffels, A.; Danilenko, V.N.; Maslov, D.A. Transcriptomic Profile of Mycobacterium Smegmatis in Response to an Imidazo[1,2-b][1,2,4,5]Tetrazine Reveals Its Possible Impact on Iron Metabolism. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 724042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logsdon, M.M.; Aldridge, B.B. Stable Regulation of Cell Cycle Events in Mycobacteria: Insights From Inherently Heterogeneous Bacterial Populations. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babraham Bioinformatics - FastQC A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/.

- Ewels, P.; Magnusson, M.; Lundin, S.; Käller, M. MultiQC: Summarize Analysis Results for Multiple Tools and Samples in a Single Report. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3047–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-Based Genome Alignment and Genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-Genotype. Nat Biotechnol 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonechnikov, K.; Conesa, A.; García-Alcalde, F. Qualimap 2: Advanced Multi-Sample Quality Control for High-Throughput Sequencing Data. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 292–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: An Efficient General Purpose Program for Assigning Sequence Reads to Genomic Features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. edgeR: A Bioconductor Package for Differential Expression Analysis of Digital Gene Expression Data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R: The R Project for Statistical Computing Available online: https://www.r-project.org/index.html.

- Python 3.13 Documentation — DevDocs Available online: https://devdocs.io/python/.

- Matplotlib Documentation — Matplotlib 3.9.2 Documentation Available online: https://matplotlib.org/stable/index.html.

- NumPy Documentation Available online: https://numpy.org/doc/.

- GOpiscator 0.1.5 Available online: https://pypi.org/project/gopiscator/.

- Xu, F; Cheng, G; Hao, H; Wang, Y; Wang, X; Chen, D; Peng, D; Liu, Z; Yuan, Z; Dai, M. Mechanisms of Antibacterial Action of Quinoxaline 1,4-di-N-oxides against Clostridium perfringens and Brachyspira hyodysenteriae. Front Microbiol. 2016, 7 - 1948. [CrossRef]

- Suter, W.; Rosselet, A.; Knüsel, F. Mode of Action of Quindoxin and Substituted Quinoxaline-Di-N-Oxides on Escherichia Coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1978, 13, 770–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuPlessis, E.R.; Pellett, J.; Stankovich, M.T.; Thorpe, C. Oxidase Activity of the Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenases. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 10469–10477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padavattan, S.; Jos, S.; Gogoi, H.; Bagautdinov, B. Crystal Structure of Enoyl-CoA Hydratase from Thermus Thermophilus HB8. Acta Crystallogr F Struct Biol Commun 2021, 77, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savolainen, K.; Bhaumik, P.; Schmitz, W.; Kotti, T.J.; Conzelmann, E.; Wierenga, R.K.; Hiltunen, J.K. Alpha-Methylacyl-CoA Racemase from Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Mutational and Structural Characterization of the Active Site and the Fold. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 12611–12620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Huang, L.; Pan, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, D. Deoxidation rates play a critical role in DNA damage mediated by important synthetic drugs, quinoxaline 1,4-dioxides. Chemical Research in Toxicology 2015, 28(3), 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haoxian, An; Yonggang, Li; Yanshen, Li; Shanmin, Gong; Ya’ning, Zhu; Xinru, Li; Shuang, Zhou; Yongning, Wu. Advances in Metabolism and Metabolic Toxicology of Quinoxaline 1,4-Di-N-oxides. Chemical Research in Toxicology 2024, 37 (4), 528-539. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Barkan, D.; Redelman-Sidi, G.; Shuman, S.; Glickman, M.S. Mycobacteria Exploit Three Genetically Distinct DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathways. Mol Microbiol 2011, 79, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Nair, D.T. Cloning, Expression, Purification, Crystallization and Preliminary Crystallographic Analysis of MsDpo4: A Y-Family DNA Polymerase from Mycobacterium Smegmatis. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun 2011, 67, 812–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Vultos, T.; Mestre, O.; Tonjum, T.; Gicquel, B. DNA Repair in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Revisited. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2009, 33, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Riccardo, Miggiano; Castrese, Morrone; Franca, Rossi; Menico, Rizzi. Targeting Genome Integrity in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: From Nucleotide Synthesis to DNA Replication and Repair. Molecules 2020, 25(5), 1205. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Bradley, N.P.; Lu, W.; Wahl, K.L.; Zhang, M.; Yuan, H.; Hou, X.-F.; Eichman, B.F.; Tang, G.-L. Base Excision Repair System Targeting DNA Adducts of Trioxacarcin/LL-D49194 Antibiotics for Self-Resistance. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, 2417–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, T.; Rai, N.; Ramachandran, R. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Class II Apurinic/Apyrimidinic-Endonuclease/3’-5’ Exonuclease III Exhibits DNA Regulated Modes of Interaction with the Sliding DNA β-Clamp. Mol Microbiol 2015, 98, 46–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, Nätt; Annika, Thorsell. Stress-induced transposon reactivation: a mediator or an estimator of allostatic load? Environ Epigenet. [CrossRef]

- Frolova, S.G. , Klimina K.M., Kumar R., Vatlin A.A., Salunke D.B., Kendrekar P., Danilenko V.N., Maslov D.A. Identification of Mutations Conferring Tryptanthrin Resistance to Mycobacterium Smegmatis. Antibiotics, 2021, 10(1), 6.

- Ganley, B.; Chowdhury, G.; Bhansali, J.; Daniels, J. S.; Gates, K. S. Redox-activated, hypoxia-selective DNA cleavage by quinoxaline 1,4-di-N-oxide. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2001, 9, 2395–2401, 2395. [Google Scholar]

- Ashwani, Kumar; Aisha, Farhana; Loni, Guidry; Vikram, Saini; Mary, Hondalus; Adrie, JC. Steyn Redox homeostasis in mycobacteria: the key to tuberculosis control? Expert Rev Mol Med. 2011, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganley, B.; Chowdhury, G.; Bhansali, J.; Daniels, J. S.; Gates, K. S. . Redox-activated, hypoxia-selective DNA cleavage by quinoxaline 1,4-di-N-oxide. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2001, 9, 2395–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurumurthy, M.; Rao, M.; Mukherjee, T. ; Rao, et al. A novel F420-dependent anti-oxidant mechanism protects Mycobacterium tuberculosis against oxidative stress and bactericidal agents. Mol. Microbiol 2013, 87, 744–755. [CrossRef]

- Greening, C.; Jirapanjawat, T.; Afroze, S.; Ney, B.; Scott, C.; Pandey, G.; Lee, BM.; Russell, RJ.; Jackson, CJ.; Oakeshott, JG.; Taylor, MC.; Warden, AC. ; Mycobacterial F420H2-Dependent Reductases Promiscuously Reduce Diverse Compounds through a Common Mechanism. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatlin, A.A.; Frolova, S.G.; Bekker, O.B.; Danilenko, V.N. Studying the mechanism of action of new derivatives of quinoxalin-1,4-dioxide on the model organism Mycobacterium smegmatis. RUDN Journal of Ecology and Life Safety 2024, 32(1), 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).