1. Introduction

The Western Balkans is one of Europe’s most disaster-prone regions, consistently affected by natural hazards that impact the lives and well-being of local communities (Cvetković, Renner, Aleksova, & Lukić, 2024). Floods are the most common disaster, impacting over five million people and causing economic damages exceeding 10 billion euros in the last thirty years. People in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina still vividly recall the severe floods of 2014, which destroyed thousands of homes and livelihoods. The region also sits in a seismically active zone, with earthquakes such as those in Skopje (1963), Montenegro (1979), and Albania (2019) leaving lasting scars and highlighting long-term vulnerability. Landslides often occur after heavy rains, disrupting transportation and isolating rural areas. At the same time, wildfires—driven by climate change and drought—pose increasing threats to homes, forests, and cultural sites, especially in Montenegro, Croatia, and North Macedonia. These recurring events reveal both the region’s fragility and the resilience of its people, who continually rebuild and recover after crises (EM-DAT, 2023; UNDRR, 2023).

First-responder systems in the Western Balkans face complex challenges due to increasing hazards, legacy issues from post-conflict periods, and shifting security threats (Cvetković, 2013; Cvetković, 2024a, 2024b; Cvetković, Tanasić, Renner, Raupenstrauch, Rokvić, & Beriša, 2024). Furthermore, first responders typically include fire and rescue services, police, emergency medical services, civil protection units, and the armed forces, as they are the first to arrive at the scene with the primary mission of protecting lives, property, and communities during emergencies (Cvetković, 2013; Cvetković et al., 2024). To some extent, recent research highlights a rise in the frequency and severity of disasters, emphasizing that traditional, isolated response models are outdated and must change toward technology-driven, networked, and collaborative methods (Grozdanić et al., 2024; Kanteler & Bakouros, 2024c; Trbojević & Radovanović, 2024). It is worth noting that this debate often revolves around three key themes: the rapid adoption of new response technologies such as AI, drones, and advanced communications; the importance of cross-border cooperation; and the integration of psychosocial and resilience training for emergency responders (Grozdanić et al., 2024; Kanteler & Bakouros, 2024c; Marceta & Jurisic, 2024; Trbojević & Radovanović, 2024).

Given the shared characteristics of many disasters, first responders tend to pursue a set of common objectives. For instance, these include (Cvetković, 2013): saving and protecting human lives; alleviating suffering; containing incidents and preventing their escalation; issuing timely warnings to the public and businesses, offering guidance, and providing accurate information; safeguarding the health and safety of emergency personnel; preserving the environment; protecting property and material assets as far as possible; maintaining or restoring critical operations; ensuring the continuity of essential services at an appropriate level; encouraging and facilitating self-help within local communities; supporting investigations and inquiries (e.g., by preserving the scene and managing official records effectively); assisting community recovery through humanitarian aid; assessing the effectiveness of response and recovery efforts; and identifying as well as implementing lessons learned.

From experience, various regional case studies demonstrate that digital tools are revolutionizing command, control, and coordination. For example, initiatives involving drones, awareness systems, and resilient communication have enhanced speed and information quality. Nonetheless, issues such as scaling, lifecycle management, and interoperability between agencies persist, mainly due to resource shortages and fragmented governance, which hinder technology adoption and sustained support (Jovičić, Gostimirović, & Milašinović, 2024a; Manoj & Baker, 2007; Ramakrishnan, Yuksel, Seferoglu, Chen, & Blalock, 2022). These challenges are often linked to resource gaps and fragmented governance, complicating the adoption of new technologies and their ongoing support. Since natural hazards such as floods, wildfires, earthquakes, and population movements frequently cross borders (Cvetković, Renner, Aleksova, & Lukić, 2024; Ivanov & Cvetković, 2016; Öcal, 2021), many studies emphasize the need for regional coordination of preparedness and response.

Delphi-based efforts suggest frameworks—from observatories to shared training facilities—to harmonize protocols, share capabilities, and formalize information exchange among nations (Kanteler & Bakouros, 2024a). However, inconsistent regulations and policy differences can impede implementation, creating gaps at the science–policy-practice interface (Kanteler & Bakouros, 2024a, 2024c; Kaplan, Bergman, Christopher, Bowen, & Hunsinger, 2017; Trbojević & Radovanović, 2024). The human element is equally important. Data from deployments and training reveal that responders and volunteers face ongoing psychological stress. This underscores the need for embedded mental health support such as peer networks, psychological first aid, and resilience training adapted to regional cultural and operational contexts (Denkova, Zanesco, Rogers, & Jha, 2020; Janković, Cvetković, Gačić, Renner, & Jakovljević, 2025; Metić, 2025; Milenkovic, 2025; O’Toole, Mulhall, & Eppich, 2022; Tan et al., 2024; Vidović & Beriša, 2025; Vračević, 2025; Wild et al., 2020). While progress has been made, many practitioners find that current mental health services are insufficient or inconsistently delivered, highlighting the need for practical, evidence-based approaches and routine evaluation (Doody, Robertson, Cox, Bogue, Egan, & Sarma, 2021).

Community capacity at the local level is vital alongside professional services. Therefore, research from Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia suggests that better preparedness is linked to social cohesion, education, and effective risk communication at the local level. This suggests, to some extent, responder effectiveness improves when citizen skills and trust are built together (Doody et al., 2021; Milan, 2018). Reviews recommend local strategies that utilize indigenous knowledge and participatory planning to address specific vulnerabilities (Chenwei, Qirui, & Lv, 2023; Imperiale & Vanclay, 2021). Overall, the region is undergoing modernization, increased cross-border cooperation, and a greater focus on psychosocial issues. Still, challenges like coordination gaps, mental health shortages, and inconsistent application of proven resilience measures persist.

These problems are worsened by institutional fragmentation and policy misalignment, which hinder capacity building and the dissemination of effective practices (Bela, Fisher, & Rexhepi, 2019; Trbojević & Radovanović, 2024). There is a clear need for culturally sensitive, evidence-based programs, which remain underdeveloped (Crane, Falon, Kho, Moss, & Adler, 2021; Crowe, Glass, Lancaster, Raines, & Waggy, 2017; Denkova et al., 2020; Drury, Carter, Cocking, Ntontis, Guven, & Amlȏt, 2019; Joyce, Shand, Lal, Mott, Bryant, & Harvey, 2018; Kelmendi & Hamby, 2022; Ketelaars, Gaudin, Flandin, & Poizat, 2024).

Building on existing evidence, cross-border cooperation is increasingly seen as essential for disaster resilience in the Balkans. In addition, multiple studies confirm that disasters, such as floods, wildfires, and earthquakes, do not respect national borders, making joint preparedness and response crucial (Ponder, Walters, Simons, Simons, Jetelina, & Carbajal, 2022). For instance, expert consensus, gathered through Delphi research with stakeholders from 12 countries, emphasizes the need for harmonized frameworks to facilitate coordination, shared awareness, and swift resource mobilization during crises (Kaim, Bodas, Camacho, Peleg, & Ragazzoni, 2023). Not only that, but these frameworks enable the pooling of limited equipment, expertise, and funding that no single country can sustain alone (Nunnari, 2008; Cvetković, Tanasić, Ocal, Kešetović, Nikolić, & Dragašević, 2021; Cvetkovic, 2019; Cvetković & Šišović, 2024; Renner, Cvetković, & Lieftenegger, 2025). They also promote standardized communication, reduce effort duplication, and help overcome longstanding institutional and political barriers to effective disaster management (Ayalew & Lema, 2025; Baćilo, 2025; Barik, Bhuyan, & Hodam, 2025; Beli et al., 2025; Hanspal & Behera, 2025; Matewos, 2025; Nunnari, 2008; Ocal & Torun, 2025; Sarkar, 2025)

However, implementing these frameworks remains difficult. While agreements and strategies are in place, their execution often faces obstacles such as political fragmentation, legal differences, and bureaucratic inertia (Cvetković, Renner, & Jakovljević, 2024; Dayberry & Fisher, 2023; Hanspal & Behera, 2024; Jovičić, Gostimirović, & Milašinović, 2024b; Jurišić & Marceta, 2024). Literature highlights that cross-border efforts should go beyond crises and include ongoing training, exercises, and trust-building activities. By increasing institutional capacity and promoting mutual understanding, collaboration can enhance emergency response speed and effectiveness, while also strengthening long-term resilience. Overall, research indicates that cross-border collaboration is both a practical necessity and a strategic opportunity for the Western Balkans, with success contingent upon sustained investment in joint planning, interoperable systems, and regional solidarity (Kaim et al., 2023; Ponder et al., 2022).

This review aims to place first-responder preparedness in the Western Balkans within an international framework, synthesize technological, organizational, psychosocial, and community reforms, identify strengths and obstacles, and suggest practical, region-specific strategies to boost resilience (Ahmed, 2025; Beli, Renner, Cvetković, Ivanov, & Gačić, 2025; Dada, Hamza, & Mohammed, 2025; Inusa et al., 2025; Karmaker, 2025; Ocal & Torun, 2025; Tushabe et al., 2025). It addresses important gaps in current research and supports policymakers and practitioners working toward interoperable, people-centered emergency systems in the Western Balkans (Dayberry & Fisher, 2023; Kanteler & Bakouros, 2024c; Trbojević & Radovanović, 2024). Despite some progress, significant gaps remain in evaluating the long-term effects of resilience training, scaling technological solutions, and integrating community-based approaches across diverse socioeconomic contexts.

Additionally, this review seeks a practical, people-centered understanding of the mixed realities on the ground. Its goal is to evaluate the current preparedness of first responders in the Western Balkans and identify areas that could enhance their safety, speed, and effectiveness in the future. A unified Readiness to Respond (R2R) approach is applied across five main services—firefighting and rescue, police, emergency medical services, civil protection, and armed forces—allowing fair comparison within and between countries. The R2R index (0–60 per sector; 0–360 overall) helps identify strengths and challenges by analyzing national documents, international reports, and peer-reviewed studies for a balanced view. By assessing staffing, equipment, infrastructure, training, laws, strategies, coordination, governance, and daily challenges, the review offers clear, region-specific recommendations for decision-makers and practitioners. Overall, it situates Western Balkan systems in an international context, emphasizes opportunities for cross-border cooperation and interoperability, and highlights critical gaps that future research and investments should target.

2. Methods

2.1. Research Scope and Objectives

The primary subject of this research was the assessment of different national capacities for emergency preparedness and response in the Western Balkans. The primary focus is on five critical security and response sectors: (a) firefighting and rescue services, (b) police, (c) emergency medical services (EMS), (d) civil protection, and (e) armed forces. Concrete speaking, the overarching objectives of the study were:

To identify the level of preparedness of each sector in relation to internationally recognized standards and benchmarks.

To develop a standardized measurement framework (R2R index) applicable across different institutional and country contexts.

To highlight strengths and weaknesses in national systems and to provide evidence-based recommendations for strengthening resilience in the region.

Hence, by addressing these objectives, the study aims to contribute to both the academic literature on disaster risk management and to the development of practical policies in the Western Balkans.

2.2. Assessment Dimensions

For each sector, as well as for the composite (system-wide) assessment, six identical dimensions were applied to ensure comparability and analytical consistency:

Staffing—adequacy of the number, distribution, and qualifications of personnel in relation to operational needs and international standards.

Equipment & Vehicles / Infrastructure—availability, condition, age, and specialization of vehicles, equipment, and critical infrastructure (including aviation, ICT, hazmat, USAR).

Training & Education—existence and quality of training programs, national centers, standardization procedures, and participation in EU/NATO/UN exercises.

Legislation & Strategies—existence, currency, enforcement, and international alignment of laws, strategies, and policy documents.

Coordination & Governance—degree of centralization or institutional dualism, mechanisms for inter-institutional cooperation, and interoperability in crisis management.

Main Challenges—identification of structural obstacles such as staffing deficits, aging equipment, limited budgets, fragmentation of governance, and reliance on external assistance.

These dimensions were chosen to capture both tangible resources (personnel, equipment, infrastructure) and intangible capacities (legal framework, governance, training), thus ensuring a holistic evaluation of system readiness.

2.3. Measurement Framework: Dual Scales and Normalization

To assess readiness in a structured and comparable way, a two-tier measurement framework was applied. This framework enabled the evaluation of both sectoral performance and the overall national system capacity:

Sectoral R2R (0–60): Each of the six dimensions was scored on a 0–10 scale. The sum provided a total sectoral score ranging from 0 to 60. This allowed for detailed comparison across specific sectors, such as police, EMS, or civil protection.

Composite/System R2R (0–360): At the national level, each dimension was scored on a broader 0–60 scale. Summing these values yielded a score between 0 and 360, representing the overall system’s capacity in relation to international standards.

The relationship between the scales was formalized as follows:

This transformation ensured proportional comparison and facilitated the normalization of results.

Table 6 displays the arithmetic mean of the five sectoral scores (0–60), reflecting the relative balance of national subsystems. In contrast, Table 7 presents the integrated composite/system score (0–360), offering a holistic view of national readiness. While not always directly comparable due to differences in scope and methodology, the two indicators together provide a more comprehensive analytical framework.

2.4. Scoring Rules

The scoring process combined both quantitative and qualitative indicators:

Quantitative indicators (e.g., number of staff per 1,000 inhabitants, vehicle-to-population ratios, budget allocations) were scored proportionally to established international standards (EU, NATO, UN).

Qualitative indicators (e.g., presence of laws, governance structures, interoperability mechanisms) were assessed by expert judgment using a standardized set of thresholds: 50–60: high level of compliance; 35–49: partial compliance; 15–34: significant shortcomings; 0–14: critical weaknesses.

Each dimension was weighted equally to avoid bias and to reflect the principle that systemic readiness depends on the balanced functioning of all components.

2.5. Calculation of Scores

Scores were calculated at three levels of analysis:

1. Sectoral level: readiness of individual sectors, based on the sum of six dimensions rated on a 0–10 scale.

2. Composite/System level: readiness of the overall national system, based on dimensions rated on a 0–60 scale, summed to a maximum of 360.

3. Average readiness level: a synthetic indicator obtained as the arithmetic mean of the five sectoral R2R scores.

Formulas:

This approach ensured comparability across levels, while allowing flexibility in both micro-level (sectoral) and macro-level (system-wide) analysis.

2.6. Readiness Categories

The obtained scores were classified into four readiness categories:

Critical readiness: 0–120 / 0–20—indicates systemic deficiencies and dependence on external support.

Low readiness: 121–200 / 20–33.3—basic capacities exist, but with serious weaknesses.

Moderate readiness: 201–280 / 33.3–46.7—functional system, but not harmonized with EU or international standards.

High readiness: 281–360 / 46.7–60—system aligned with EU and international standards, resilient and sustainable.

2.7. Missing and Uncertain Data

In several cases, data on sectoral resources and capacities were incomplete, fragmented, or contradictory. Such gaps were marked as N/A and excluded from arithmetic means unless well-documented assumptions were available. For the composite score (Table 7), where a single national index was required, expert judgment was applied through triangulation of multiple sources: a) official national documents (laws, strategies, ministry reports); b) international sources (UNDP, NATO, EU IPA, INSARAG); c) secondary sources (academic publications, NGO reports, media articles). Where discrepancies emerged, a conservative approach was taken—adopting either the lower estimate or the median value—to prevent overestimation of national capacities.

2.8. Limitations

Differences in institutional architecture posed challenges to comparability across countries. For example, North Macedonia’s dual system or Bosnia and Herzegovina’s multi-layered governance created obstacles to straightforward assessment. Additionally, the availability and quality of data varied significantly. Indicators such as the number of active volunteers or the average age of specialized equipment were often outdated, fragmented, or unavailable. Consequently, the results should be regarded as indicative rather than absolute values. Despite these constraints, the methodology remains a robust tool for identifying critical gaps, tracking progress, and providing a basis for future policy interventions and academic research.

2.9. Data Sources

Data for this study were collected from three main categories of sources:

National sources: laws, strategies, statistical yearbooks, and official reports from ministries of interior, defense, and civil protection agencies.

International sources: UNDP, NATO, EU IPA, INSARAG, and EU Civil Protection Mechanism reports.

Secondary sources: peer-reviewed articles, NGO assessments, and media reports on equipment procurement, staffing, and operational performance.

By triangulating these sources, the study ensured both breadth and depth of coverage, balancing official statistics with independent evaluations.

3. Results

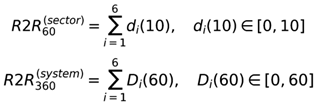

The analysis in

Table 1 reveals notable differences as well as shared challenges in the capabilities of firefighting and rescue services across the Western Balkans. All systems face issues with staffing, infrastructure, and training, while international programs like EU IPA, NATO, UNDP, and INSARAG are vital in bridging critical gaps.

Serbia (≈34/60) has approximately 3,100 professional and 1,200 volunteer firefighters (≈0.57‰), which is below the EU standard of 1‰, indicating a shortfall of around 1,400 firefighters. On the other side, the fleet’s average age is approximately 27 years, with some vehicles being renewed (420 cars from 2018 to 2023). Serbia has legislation for disaster risk reduction (2018) and fire protection, but the Fire Protection Strategy remains unadopted. Central issues include staffing shortages, aging equipment, limited local budgets, and uneven territorial coverage.

Bosnia and Herzegovina faces ongoing challenges in its emergency response capabilities. The reliance on volunteers, whose capacities vary across different entities and cantons, highlights the decentralized nature of the system. The absence of a unified legislative framework and strategy contributes to fragmentation and weak coordination among responders. Many firefighting vehicles are quite old, dating back 30–40 years, and the country only acquired its first firefighting aircraft in 2022. Overall, the country struggles with institutional fragmentation, dependence on municipal budgets, and inconsistent training, all of which hinder effective emergency management.

After all, Montenegro (60/60) has a favorable firefighter-to-population ratio of approximately 1.1 to 1.2 per thousand residents, comparable to or exceeding European Union standards. The country has 242 firefighting vehicles, although 36 are out of service, and three aircraft, with only one typically operational. Firefighting training is provided at the Police Academy and through international programs. The legal framework is based on the Law on Protection and Rescue, and a new strategic plan for 2018–2023 is currently under development. Major challenges include an aging aviation fleet, limited local budgets, and dependence on international aid.

North Macedonia (≈30/60) has approximately 800–900 firefighters (≈0.5‰), which is well below EU benchmarks, resulting in a deficit of 200–300 personnel. Vehicles are 30–50 years old, supplemented occasionally by donations. Training is provided at DZS and CUK centers with international support. Despite having a Protection and Rescue Law, the adoption of strategies is often delayed. Challenges include equipment shortages, staffing deficits, and dependence on neighboring countries during major incidents.

Albania (≈32/60) employs approximately 739 professional firefighters (≈0.53‰), which is about half the EU standard. Infrastructure comprises 70 stations and nearly 0.9 vehicles per 10,000 inhabitants, though specialized equipment is scarce. Training programs conducted by UNDP and Poland have trained approximately 356 firefighters to INSARAG standards. The legal framework includes the 2019 Civil Protection Law and the 2020 National Plan. The main hurdles are a lack of aerial firefighting capacity, high staff turnover, and reliance on international support (EU/NATO).

Regional overview: Except for Montenegro, all countries are below the EU benchmark of 1‰. Vehicle fleets are generally aged 25–50 years, relying partly on donations and international programs. Training varies in quality, and while legislative frameworks exist, strategies are often delayed or not fully integrated (notably in Bosnia and Herzegovina and North Macedonia). Common challenges include staffing shortages, outdated equipment, financial constraints, and dependence on external aid (

Table 1).

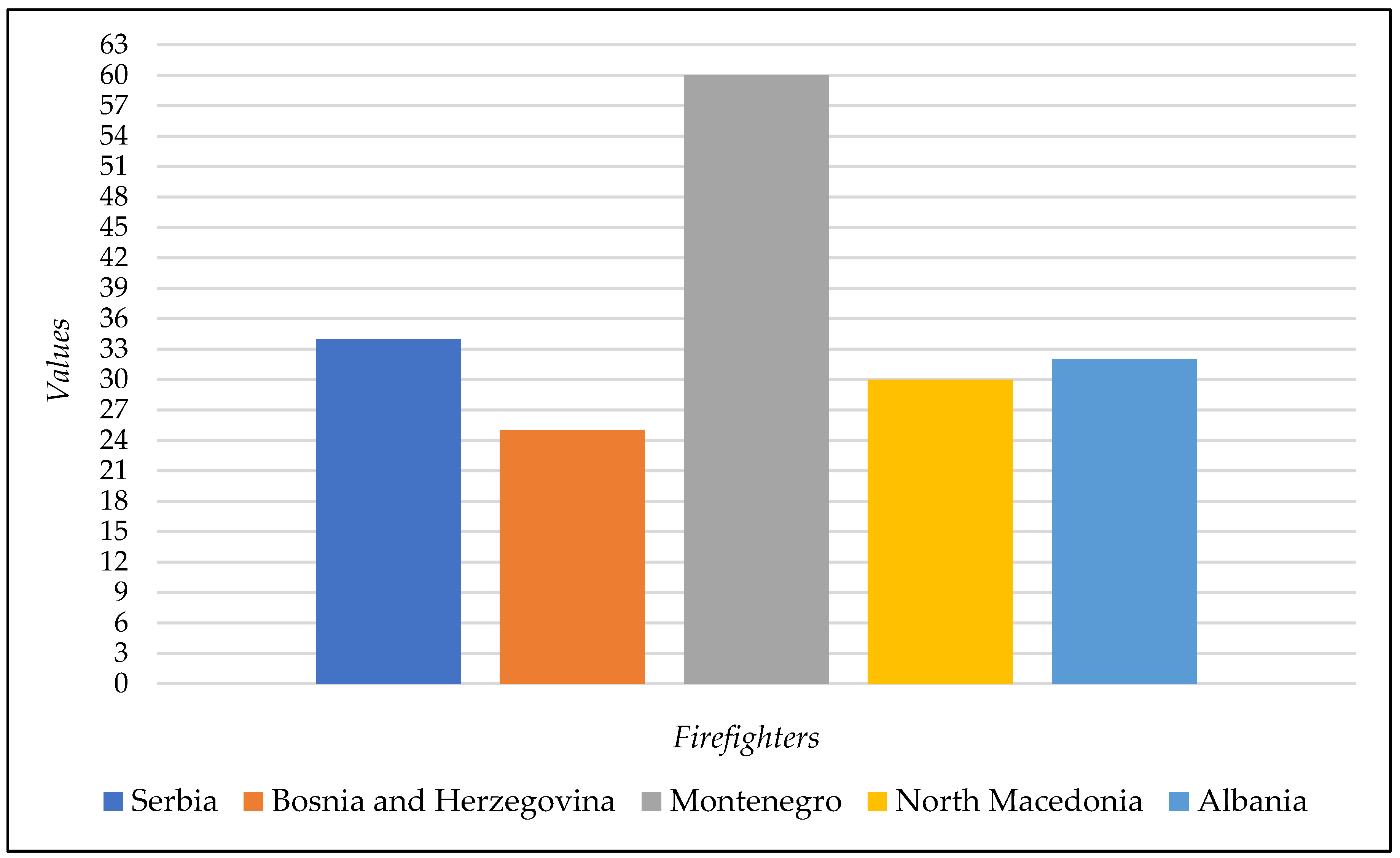

Police forces are a key component of security systems in the Western Balkans. Still, their capacities, professionalism, and readiness vary significantly depending on staffing, equipment, legal frameworks, and the main challenges they face.

Serbia (47/60) has about 44,000 police officers, with a ratio of 1 officer per 160 residents—well above the EU average. Infrastructure has been partly modernized, specialized units are in place, and digitalization is ongoing. The Police Academy and EU IPA programs offer continuous training, while the legal framework comprises the Police Law (2016, amended in 2021) and the Police Strategy. Main challenges include an excessive number of administrative staff, insufficient personnel in the local and traffic police, and politicization.

Bosnia and Herzegovina (35/60) has approximately 16,000 police officers across its entities and cantons, with a ratio of one officer per 200 residents. The system is highly fragmented, with training and equipment distributed unevenly across the organization. While entity and cantonal laws exist, weak coordination at the national level remains a significant issue. Key challenges are institutional fragmentation, inconsistent training quality, and politicization.

Figure 1.

Capacities and Readiness of Firefighting and Rescue Services in the Western Balkans.

Figure 1.

Capacities and Readiness of Firefighting and Rescue Services in the Western Balkans.

Montenegro (45/60) employs about 4,500 police officers, with a ratio of 1 per 140, which is a high coverage level relative to its population. Recently, vehicle and uniform modernization has been undertaken, and training is provided through the Police Academy and NATO/EU programs. The legal framework includes the Law on Internal Affairs and the Police Reform Strategy. The main challenges include a limited number of specialized officers and a dependence on international partners for training.

North Macedonia (38/60) has roughly 7,000 police officers, with a ratio of 1 per 230 residents—below the European average. Partial modernization has been achieved in special units, but regular police remain under-equipped. Training centers are available, and the National Police Reform Strategy is in place, although progress in reform is slow. The key challenges are the need for professionalization and low public trust in the police.

Albania (41/60) employs approximately 11,000 officers, with a ratio of 1 officer per 260 people, representing the lowest coverage in the region. Since 2014, reforms supported by the EU and OSCE have improved equipment and training through the Police Academy and international programs. The legal framework includes the Law on State Police and the Police Reform Strategy 2020–2030. Significant challenges include insufficient staffing in rural areas, corruption, and low public trust.

On average, Western Balkan states have more police officers per capita than most EU countries. However, capacities differ significantly—Serbia and Montenegro have substantially higher ratios of officers, while North Macedonia and Albania lag. Infrastructure also varies: some countries are undergoing modernization (Montenegro, Albania), while others rely on outdated equipment (Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia). A legal framework exists in all states, but challenges include fragmentation (BiH), slow reform implementation (North Macedonia), and persistent issues with politicization, excessive administrative staffing, corruption, and low public trust in police structures (

Table 2 and

Figure 2).

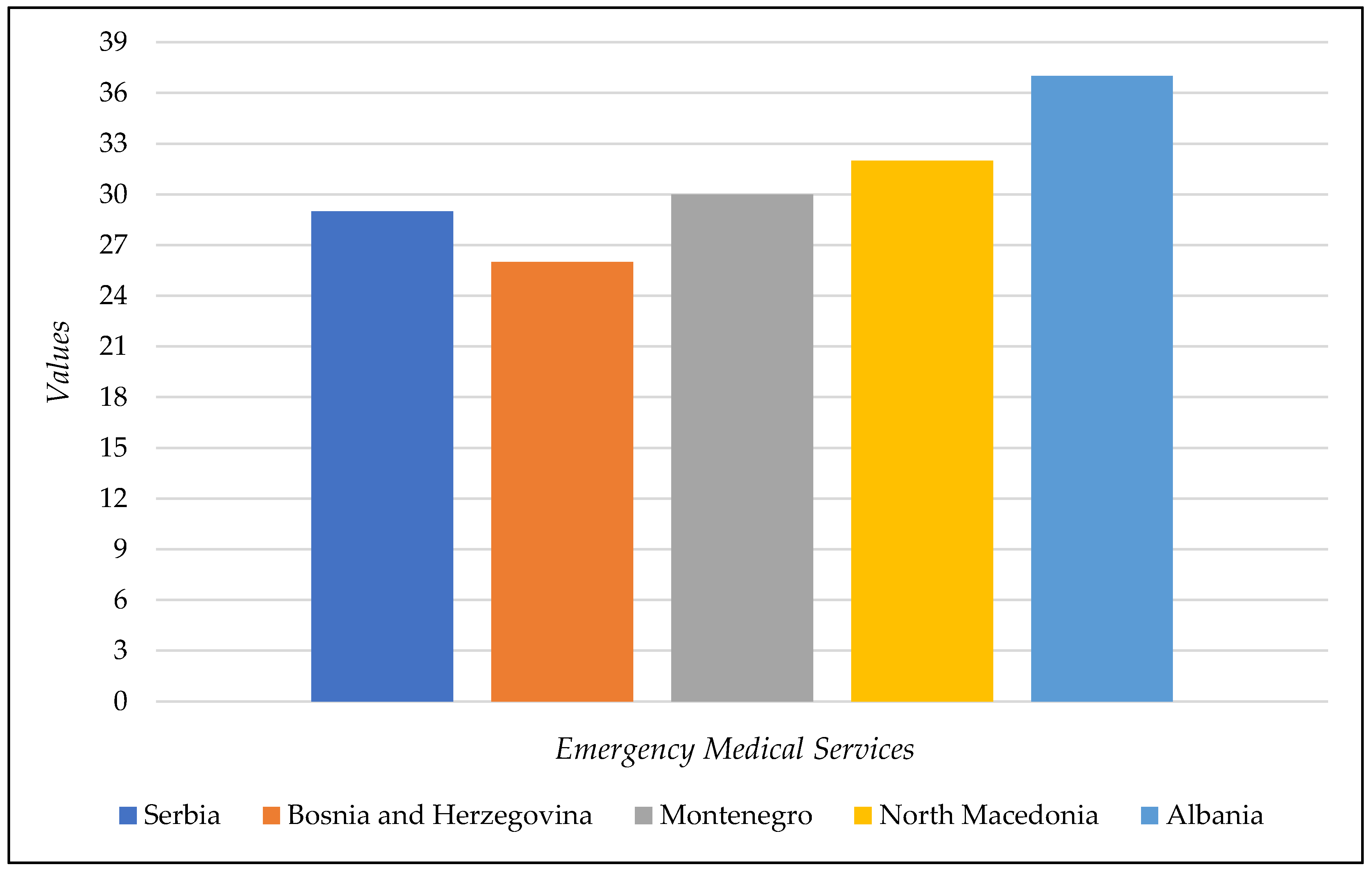

Emergency medical services (EMS) systems in the Western Balkans face significant challenges related to human resources, coverage, equipment, and legislative frameworks, all of which directly impact the quality and speed of response. Readiness scores (R2R) show that all countries fall within the lower-medium range, with pronounced disparities between urban and rural areas.

Serbia (29/60) has the largest workforce in the region (~5,000), yet about 40% of its territory lacks adequate coverage. Its fleet of roughly 500 vehicles is on average over 10 years old, and there are no specialized training centers. Due to the absence of a dedicated EMS law, the system operates under general health regulations, resulting in inconsistent protocols and longer response times.

Bosnia and Herzegovina (26/60) relies on 2,000–3,000 employees, who are heavily dependent on volunteers. Services are fragmented across entities and cantons, with significant differences in coverage and equipment. The absence of a unified legislative framework and common standards results in uneven service quality and poor coordination.

Montenegro (30/60) has a small workforce (~700) and about 120 ambulances, many of which are outdated. Urban coverage is adequate, but rural areas remain underserved. The biggest challenge is the shortage of emergency medicine specialists, and the planned integration into the 112 system is still in progress.

North Macedonia (32/60) employs approximately 1,200 staff. Although the 112 system was introduced in 2022, outdated equipment and administrative barriers hinder its effectiveness. While training centers exist, the shortage of vehicles and personnel remains a serious issue, exacerbated by weaknesses in management and organization.

Albania (37/60) implemented reforms after 2019 and modernized its fleet with donor support (IPA, USAID). International partners have supported training programs, but high staff turnover and reliance on external assistance persist. Nevertheless, Albania has the highest score in the region, thanks to recent reforms and modernization efforts.

Overall, the data indicate that EMS systems in the region remain underdeveloped, reliant on external support, and lack standardization. Key recommendations include increasing the number of emergency medicine specialists, modernizing vehicle fleets, establishing national training centers, and adopting unified legal frameworks to align EMS standards with European practices (

Table 3 and

Figure 3).

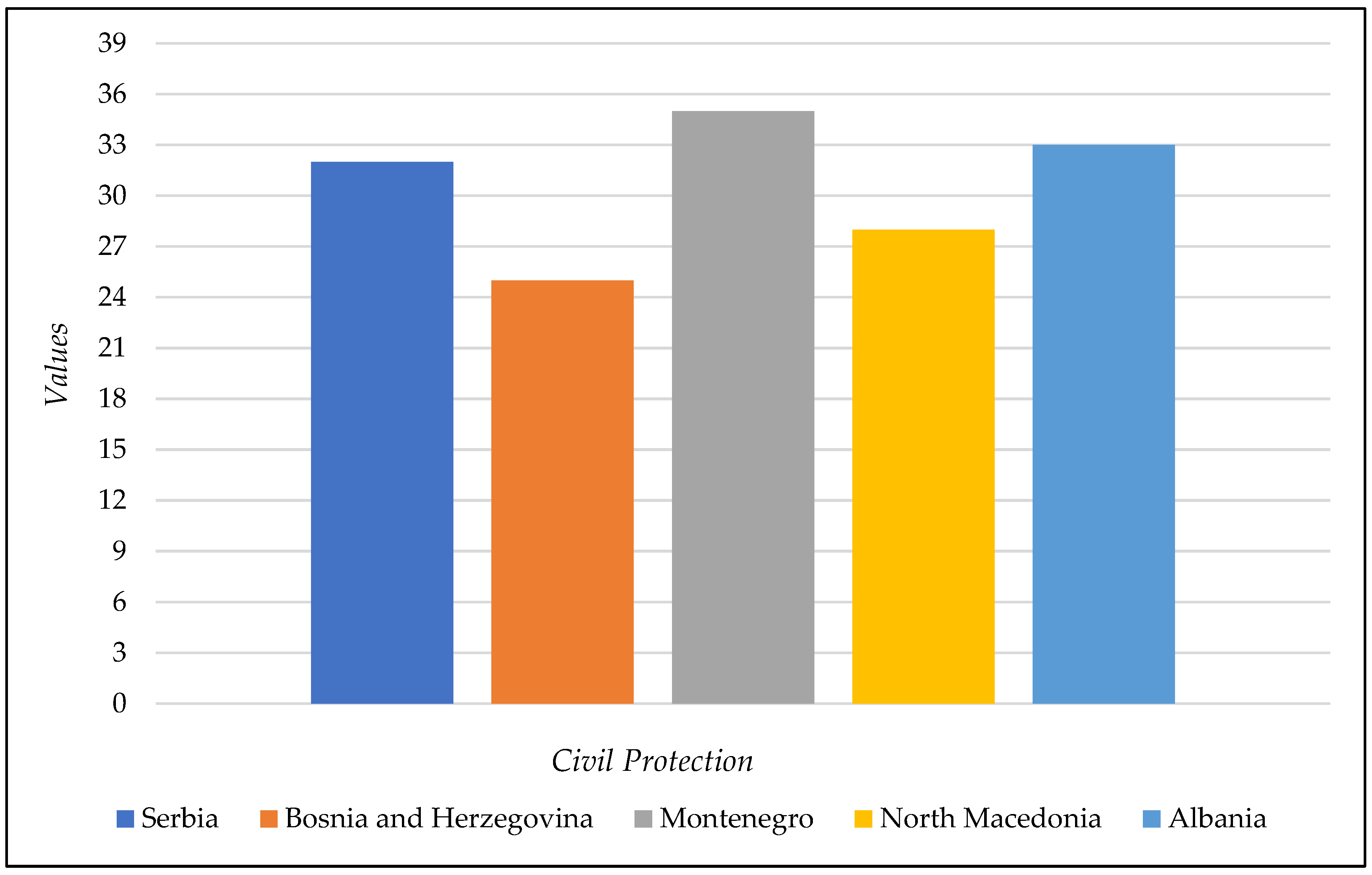

Table 4 presents the organization, resources, and key challenges of civil protection systems in the five Western Balkan countries. The results reveal significant differences in institutional structures and capacities but also highlight common issues such as staff shortages, outdated equipment, limited budgets, and reliance on international aid.

Serbia (32/60) has about 4,000 members in the Ministry of Interior’s Sector for Emergency Management, supported by a network of volunteers. The system is officially organized, with a National Training Center and IPA/EU training programs, but faces serious challenges—aging vehicles, insufficient staff, and limited local budgets. The legislative framework comprises the Disaster Risk Reduction Law (2018), the Fire Protection Law, and a new strategy currently under development.

Bosnia and Herzegovina (25/60) scores the lowest due to significant fragmentation. The system comprises the Federal Administration of Civil Protection (~211 staff), the Republic Administration (~187 staff), as well as cantonal and local units, but lacks a national law and centralized coordination. The equipment is outdated, training is irregular, and there is no national training center. The primary challenges are fragmentation, inadequate coordination, and a lack of stable funding.

Montenegro (35/60) has a Directorate for Protection and Rescue (~127 staff) supported by municipal units (~785 staff). The country operates 242 vehicles, with 152 being functional, while its small aerial capacity is often non-operational. Training is provided through the Police Academy and international exercises. The system is based on the Law on Protection and Rescue and the 2018–2023 Strategy. The main challenges include limited resources, aging equipment, and reliance on international support.

North Macedonia (28/60) operates a dual system comprising the Crisis Management Center (~285 staff) and the Protection and Rescue Directorate (~278 staff). The equipment is outdated, and for larger emergencies, the country relies on the military and neighboring countries. Training is mainly conducted through international programs (EU, NATO, UN), as there is no national training center. Significant issues include institutional dualism, weak coordination, and financial limits.

Albania (33/60) established the National Civil Protection Agency (NCPA) in 2019 with about 100 staff members. The system has been modernized through UNDP and Polish projects, and 356 staff members have been trained to INSARAG standards. However, serious challenges remain, including insufficient staffing, uneven distribution of equipment in rural areas, and a heavy reliance on donors.

Serbia and Montenegro have more stable institutional systems, though resources are limited. Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as North Macedonia, lag due to fragmentation and weak coordination. At the same time, Albania has made progress thanks to reforms and international support, though it has yet to reach a sustainable capacity level (

Table 4 and

Figure 4).

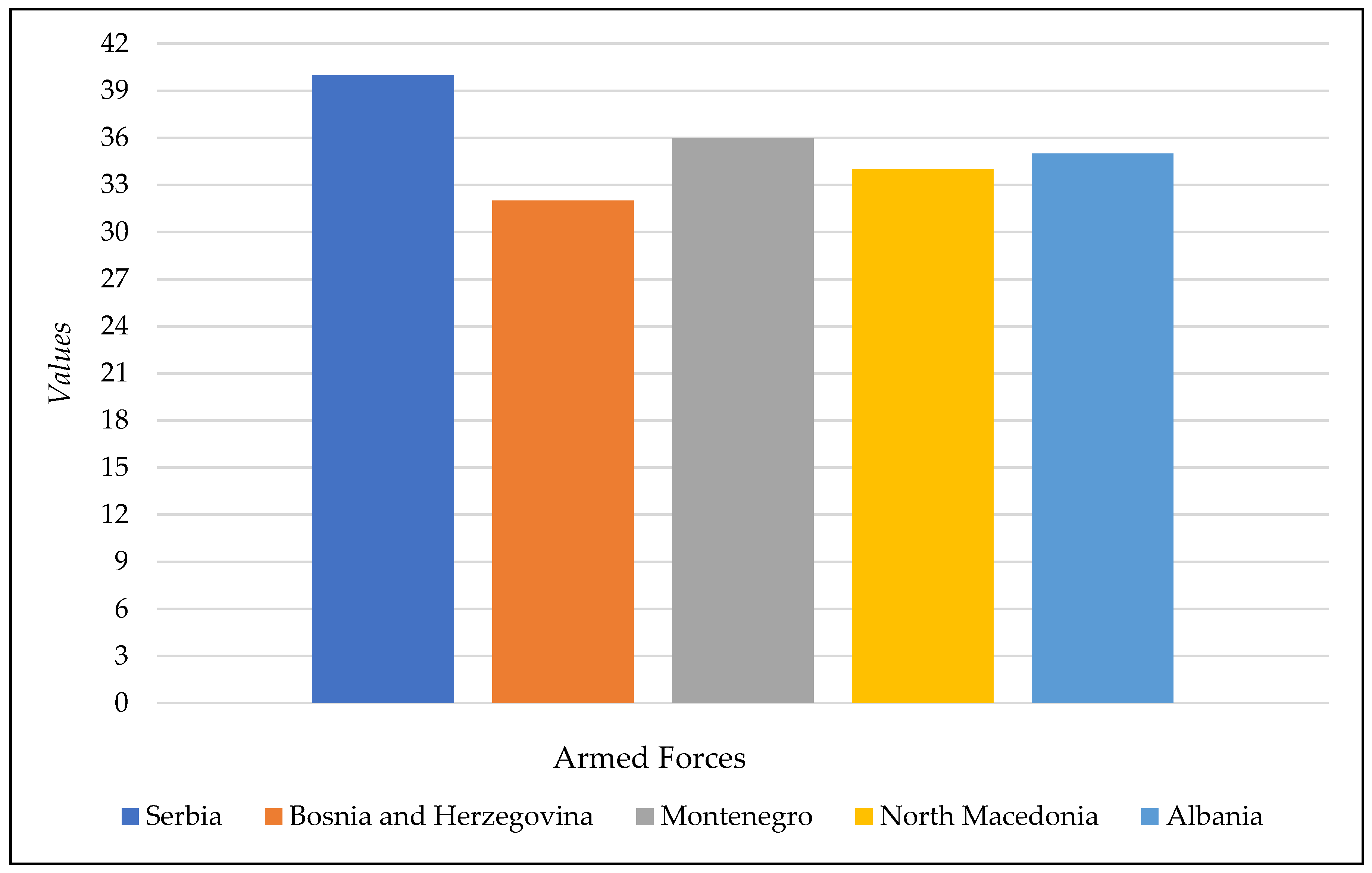

Table 5 outlines the structure, equipment, and training of the Western Balkans armed forces, highlighting key challenges that affect their readiness. While each country has unique aspects, common themes include small force sizes, reliance on light infantry, difficulties with modernization, and a heavy dependence on international partners such as NATO and the EU.

Serbia (40/60) has the most significant military, with about 28,000 active personnel and 50,000 reserves—roughly one soldier per 250 inhabitants. Its fleet includes newer equipment such as MiG-29 jets, helicopters, and Pantsir systems, alongside older Soviet hardware. Training is supported by institutions such as the Military Academy and NATO’s PfP exercises. However, Serbia faces challenges such as limited financial resources, outdated systems, and a lack of strategic agility.

Bosnia and Herzegovina (32/60), with around 9,500 active and 5,000 reserve soldiers, has a ratio of about one soldier per 330 inhabitants. It is primarily light infantry forces that depend on NATO donations and are trained at the Peace Support Operations Training Center, as well as through NATO and OSCE programs. Political and ethnic divisions significantly impact the military, complicating command and hindering modernization efforts due to underfunding.

Montenegro (36/60), with about 2,300 active troops (one per 280 inhabitants), emphasizes mobility over heavy firepower. Consequently, it maintains some naval patrols and NATO-compatible equipment. Since joining NATO in 2017, its training at the Danilovgrad Military Training Center aligns with alliance standards. Nonetheless, its small size makes it reliant on NATO and EU support, especially for air and naval capabilities.

North Macedonia (34/60) has roughly 8,000 active and 4,000 reserve soldiers—about one per 280 inhabitants. The military, primarily light infantry, has undergone significant modernization since NATO accession in 2020. Training at Krivolak, as well as participation in NATO and EU exercises, has enhanced interoperability. However, outdated equipment and slow upgrades continue to pose challenges, which are further compounded by financial constraints.

Albania (35/60) consists of approximately 8,500 active and 5,000 reserve personnel, with a ratio of one soldier per 350 inhabitants. Its light forces have benefited from NATO assistance, with the introduction of Black Hawk helicopters and patrol boats into service. Training is provided by the Armed Forces Academy and NATO missions, with updated laws and strategic plans. Despite progress, Albania continues to face logistical challenges, corruption risks, and a dependence on donors.

Overall, the Western Balkans’ armed forces share more similarities than differences, including small size, limited heavy weaponry, and reliance on NATO standards, exercises, and donations. Serbia has the most significant force, but its modernization is uneven. Montenegro and Albania benefit from NATO membership but face resource constraints. Bosnia and North Macedonia continue to face political, financial, and institutional challenges. The main regional challenge remains transforming these modest, donor-supported forces into sustainable, modern militaries capable of meeting national and regional security needs (

Table 5 and

Figure 5).

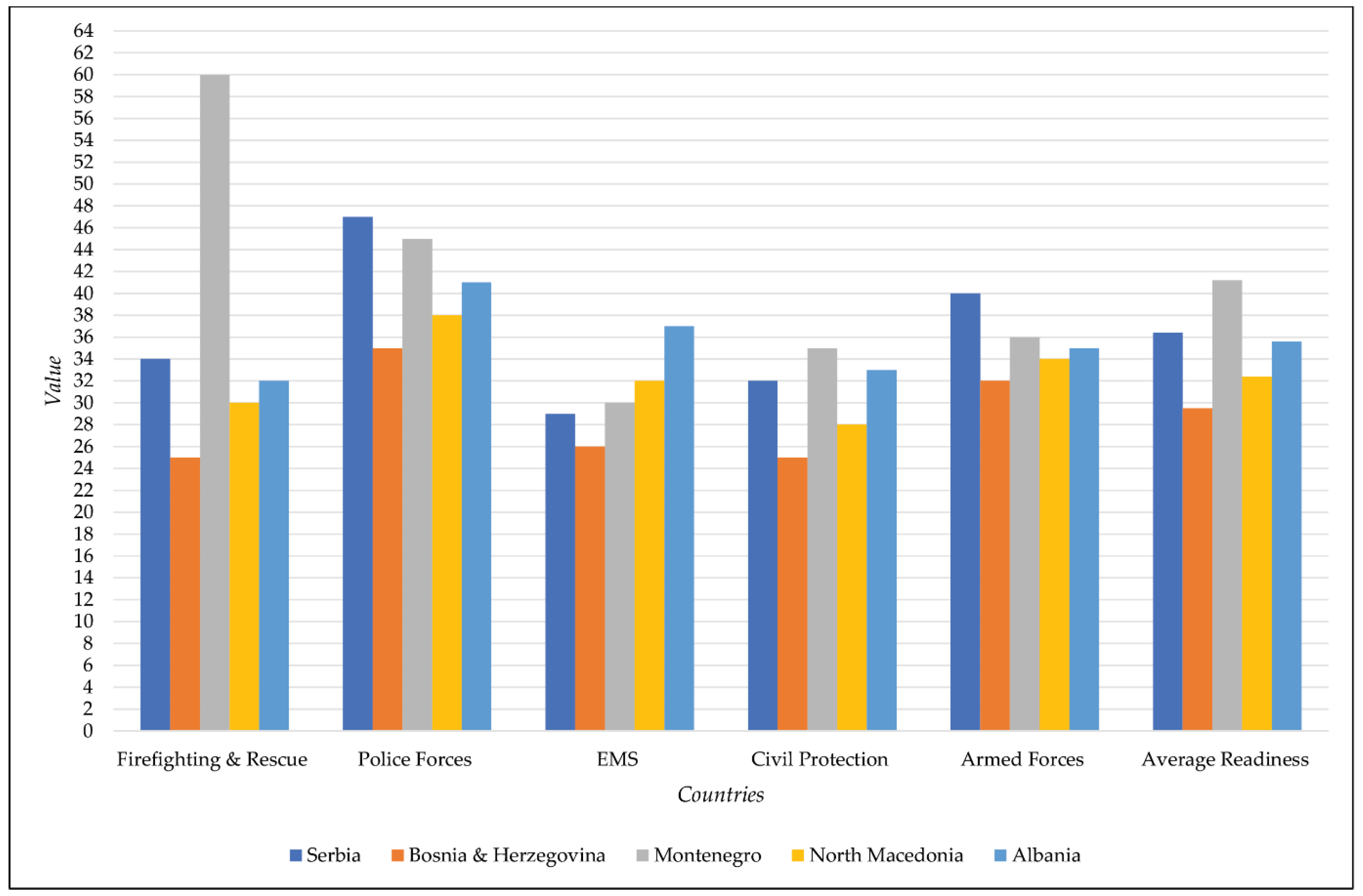

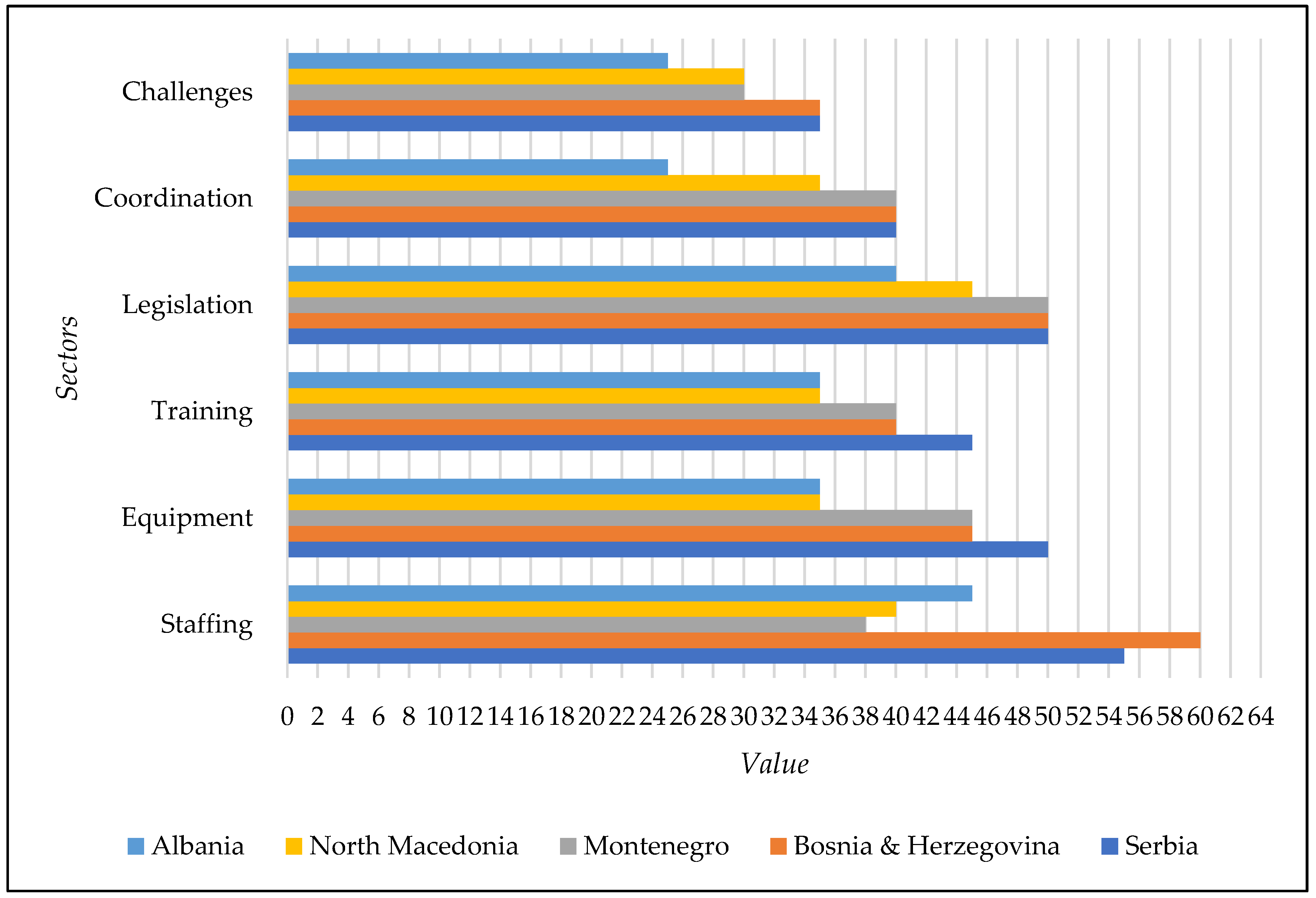

Table 6 offers a summary of the key capabilities of the five security and protection sectors—firefighting and rescue services, police, emergency medical services (EMS), civil protection, and armed forces—based on their readiness scores (R2R) across Western Balkan countries.

Serbia (36.4/60) shows moderate overall capacity, excelling in police (47/60) and armed forces (40/60), but scoring lower in EMS (29/60) and civil protection (32/60). Significant issues include outdated equipment and staffing shortages.

Bosnia and Herzegovina (29.5/60) has the lowest regional average, reflecting deep fragmentation in all sectors. Its weakest areas are EMS (26/60) and civil protection (25/60), though the armed forces (32/60) are somewhat more stable. System weaknesses stem from a lack of unified coordination and financial dependence.

Montenegro (41.2/60) scores the highest, thanks to excellent firefighting and rescue services (60/60) and a robust police sector (45/60). However, limited human resources and reliance on international support pose ongoing challenges.

North Macedonia (32.4/60) faces systemic issues, especially weak civil protection (28/60) and firefighting services (around 30/60). The police (38/60) and EMS (32/60) do somewhat better, but slow reforms and institutional dualism hinder efficiency.

Albania (35.6/60) has advanced through reforms in the police (41/60) and EMS (37/60), alongside modernization efforts supported by international partners. Still, poor rural equipment, high staff turnover, and dependence on donors remain significant obstacles.

No Western Balkan country fully meets high readiness standards across all five sectors. The starkest contrast exists between Montenegro, with the highest average readiness, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, which has the most fragmented system and the lowest scores. Common regional challenges include outdated equipment, staffing shortages, weak standardization, and ongoing reliance on international aid (

Table 6 and

Figure 6).

The review of preliminary readiness scores (R2R) in Western Balkan countries indicates that no country achieves a high level of preparedness (≥281/360). Instead, all are classified within the medium readiness category, with notable differences among them.

Serbia (275/360, 1st place) ranks highest due to its firm staffing, relatively modern equipment, and comprehensive legislative framework. However, challenges in coordination, funding, and human resources prevent it from advancing to a higher category.

Montenegro (270/360, 2nd place) shows an unexpectedly high readiness level for its small size. Its advantages include favorable staffing ratios and a solid normative infrastructure, yet limited system scale and reliance on international aid remain significant hurdles.

Albania (243/360, 3rd place) achieves good results, especially in legislation and internationally supported training; however, staff shortages and dependence on external support limit the system’s resilience and sustainability.

North Macedonia (220/360, 4th place) falls behind due to outdated equipment and institutional barriers. Despite having a normative framework and international training cooperation, limited resources and poor inter-institutional coordination are key issues.

Bosnia and Herzegovina (205/360, 5th place) scores the lowest, mainly due to systemic fragmentation and the lack of a unified national strategy. Weak coordination, obsolete equipment, and financial reliance on international aid further impede capacity development.

Regionally, Serbia and Montenegro lead in readiness, whereas Bosnia and Herzegovina lags significantly due to structural fragmentation. Common critical challenges across these countries include: a) outdated equipment, b) insufficient staffing, c) weak coordination mechanisms, and d) dependence on international financial aid (

Table 7 and

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

The findings show that first-responder systems in the Western Balkans are generally at a moderate level of readiness, with none reaching the “high readiness” standard. Moreover, research found that all five countries assessed fall within the medium range (scores ranging from 200 to 275 out of 360), although there are significant internal differences. Thus, Montenegro stands out as the most balanced and well-equipped system (highest average R2R of about 41 out of 60), mainly due to its strong firefighting and police forces. Additionally, Bosnia and Herzegovina ranks lowest (around 29.5 out of 60), primarily due to its extreme institutional fragmentation and uneven distribution of resources across its entities. Serbia, Albania, and North Macedonia fall in the middle range, each showing strengths in specific areas (e.g., Serbia’s police and military, Albania’s EMS improvements) but facing challenges elsewhere. It can be said that this variation highlights that having sector-specific strengths does not automatically ensure overall system resilience; weaknesses in areas such as EMS or civil protection can reduce a country’s overall disaster response effectiveness.

Several common capacity gaps explain why Western Balkan countries remain in the medium-readiness bracket. First, aging equipment and infrastructure are widespread—many fire and rescue fleets are between 25 and 40 years old, and advanced assets (such as aerial firefighting units or CBRN equipment) are limited or depend on foreign donations. Second, shortages and imbalances in human resources still exist. All countries fall short of the EU benchmark of 1 firefighter per 1,000 people (most have only 0.5–0.6‰) and face deficits in specialized roles like paramedics and disaster medicine specialists (Kanteler & Bakouros, 2024b). High turnover and reliance on volunteers—particularly in the fire services of Bosnia and Herzegovina and North Macedonia—further challenge consistency. Third, weak coordination and governance hurdles reduce efficiency (Peters, 2018; Schout & Jordan, 2005; Sopha, 2023). Unclear role division, overlapping responsibilities, and fragmented supply chains often lead to duplicated work, inefficient resource use, and higher operational costs—a pattern already seen in health systems and public investment management (Agung, Rani, Millensyah, Wijayanto, Sari, & Perdana, 2025; Barre, 2024; Guo, Mallinson, Ortiz, & Iulo, 2024; Hearne, 2025; Lieberherr & Ingold, 2019; Obergassel, Xia-Bauer, & Thomas, 2023; Ravikumar, Larson, Myers, & Trench, 2018).

Fragmented structures—whether Bosnia’s multi-tiered agencies or North Macedonia’s dual crisis institutions—lead to duplication and slow decision-making. Even more centralized systems (Serbia, Albania) report poor interoperability between agencies and levels of government. Finally, a heavy reliance on external aid and ad hoc donor projects is evident. Many modernization efforts (new vehicles, training programs, communications gear) were financed or donated by the EU, NATO, UN, or bilateral partners rather than sustained by domestic budgets. These four factors—old gear, staffing gaps, coordination weaknesses, and external dependence—are repeatedly identified as core challenges across the region, echoing findings from other studies (Kanteler & Bakouros, 2024b). The INFORM risk index, for example, indicates that all Western Balkan states face a significant shortage of coping capacity, with Bosnia and Herzegovina being the most disadvantaged. This alignment with international risk metrics reinforces the credibility of the R2R assessment: the Western Balkans are indeed less equipped to handle major disasters on their own compared to more developed systems.

Comparative perspectives show that Western Balkan first-responder readiness, while modest, is not unusually low. It is similar to other transitional or developing regions facing similar challenges. Many countries emerging from conflict or with lower-middle incomes display a similar pattern of moderate preparedness, often hindered by critical bottlenecks (Cvetković, Nikolić, Nenadić, Ocal, & Zečević, 2020; Cvetković, Nikolić, Ocal, Martinović, & Dragašević, 2022; Cvetković, Dragašević, Protić, Janković, Nikolić, & Milošević, 2022; Cvetković et al., 2024; Grozdanić, Cvetković, Tin Lukić, & Aleksandar Ivanov, 2024). For example, studies in South Asia and Africa highlight underinvestment in emergency services, aging infrastructure, and fragmented governance as barriers to effective disaster response (Mukherjee et al., 2023). Overall, the Western Balkans’ medium readiness remains notably below most EU member states and OECD countries, which generally benefit from long-term investments, professionalism, and strong national frameworks (Draçi, Kraja, & Themelko, 2022; Fedajev, Panić, & Živković, 2024; Gafuri & Muftuler--Bac, 2020; Kollias, Messis, Stergiou, & Zouboulakis, 2024; Matkovski, Đokić, Zekić, & Jurjević, 2020; Matkovski, Zekić, Đokić, Jurjević, & Đurić, 2021). In the EU, integrated mechanisms such as the Union Civil Protection Mechanism and rescEU reserves ensure that smaller countries can quickly access additional firefighting aircraft, medical supplies, and personnel during crises. The Western Balkans currently lack a true equivalent—though regional cooperation is improving, it remains more project-based than institutional. These examples show that while Western Balkan responders are committed and skilled, their ability to handle large-scale emergencies still depends heavily on external support, unlike many Western European contexts.

At the same time, the Western Balkans are not alone in confronting these challenges. Other regions with shared risk profiles and limited resources have pursued collaborative strategies to boost readiness (Jiang, Jie, & Chen, 2024; Mustapha, Agha, & Masood, 2022; Shahverdi, Tariverdi, & Miller-Hooks, 2020; Song, Hwang, & Seo, 2024; Wang & Bollmann, 2024). In the Caribbean, for instance, small island states pool response assets and expertise through regional agreements. Likewise, some Southeast European EU members (e.g., Slovenia, Croatia) leveraged EU accession to rapidly modernize their emergency services and align with international standards—a pathway that Western Balkan aspirants are now attempting to follow. The literature increasingly advocates such cross-border and inter-agency cooperation as a cost-effective way to compensate for national limitations (Bignami, Ambrosi, Bertulessi, Menduni, Pozzoni, & Zambrini, 2024; Kanteler & Bakouros, 2024b, 2024c; Liu, Guo, An, & Lian, 2021; Olson, Leitheiser, Atchison, Larson, & Homzik, 2005; Simona, Taupo, & Antunes, 2021; Yanakiev, Bernal, Navajo, Stoianov, Pérez, & Martin, 2023). These results strongly support this: countries that coordinated more closely with neighbors and international frameworks (such as Montenegro’s integration in NATO exercises or Albania’s INSARAG trainings) tended to score higher in readiness. Conversely, where political or administrative barriers impeded cooperation (as in Bosnia and Herzegovina’s fragmented system), readiness suffered. Notably, expert consensus, as determined through Delphi studies, has called for Balkan nations to establish joint disaster preparedness centers, mutual aid agreements, and synchronized protocols to enhance regional resilience (Kanteler & Bakouros, 2024a; Kaim et al., 2023).

In interpreting these findings, it is essential to acknowledge the significant progress the Western Balkans have made in their context. Over the past decade, all countries have updated key legislation, created national disaster risk reduction strategies, and participated in international training initiatives readings are very much “in transition”: no longer at a critically low level,”: no longer at a critically low level, no longer at a critically low level as might have been the case in the immediate post-conflict period, but still far from the desired robustness. Incremental improvements are visible—for example, Serbia’s procurement of new firefighting vehicles from 2018 to 2023, Albania’s post-2019 EMS reforms, and Montenegro’s consistent near-EU standards in responder-to-population ratios—yet these tend to be uneven and fragile. Without consistent funding and political commitment, gains can stall or reverse; indeed, several countries still lack sustainable equipment renewal plans or standardized training accreditation. Another consideration is that quantitative scores may mask sub-national disparities. Large cities typically have better response capacities compared to rural areas, resulting in vulnerabilities being primarily located away from capitals.

The readiness of first responders in the Western Balkans has shown gradual progress, yet it still lags behind established international standards. The absence of any country in the region reaching a “high readiness” category highlights the pressing need for decisive action. Positively, the main shortcomings are not insurmountable and can be addressed through well-designed measures: upgrading outdated equipment, investing in the workforce by recruiting and retaining skilled professionals, improving command-and-control systems to enhance interoperability, and fostering joint regional capacities. These priorities align with the principles emphasized in global disaster risk reduction frameworks, such as the Sendai Framework, which advocates for stronger technical capacities and enhanced cross-border cooperation.

By drawing on lessons from both successful European and NATO practices, as well as from comparable regions worldwide, Western Balkan states can accelerate their progress toward resilience. Practically, this requires moving away from a reactive, donor-driven approach toward proactive, long-term planning—for instance, allocating multi-year budgets for emergency services, pooling regional resources to sustain shared assets like firefighting aircraft, embedding joint training and exchange programs, and harmonizing certification, data management, and communication standards. Implementing such reforms would enable first responders across the region to act more quickly and effectively when disasters such as floods, wildfires, or earthquakes occur, reducing dependence on external assistance and providing protection for their citizens at a level comparable to that in more advanced systems.

5. Conclusions

This review systematically assessed first-responder capacities in the Western Balkans, focusing on five key sectors—firefighting and rescue, police, EMS, civil protection, and armed forces—using the Readiness to Respond (R2R) framework. By combining sector-specific (0–60) and overall (0–360) indices, the study provided both detailed intra-sector analysis and broad cross-country comparisons.

The comparison tables revealed notable disparities within and across countries. Firefighting and rescue services showed the most significant variation: Montenegro achieved perfect readiness (60/60), while Bosnia and Herzegovina and North Macedonia faced significant gaps due to fragmentation, outdated equipment, and dependence on volunteers. Serbia and Albania ranked mid-level, hindered by staff shortages and limited aerial firefighting. Police forces generally performed better, with Serbia (47/60) and Montenegro (45/60) leading; however, issues such as politicization, corruption, and uneven rural coverage persisted. EMS remained the weakest sector, with scores ranging from 26 to 37 out of 60, struggling with staffing, aging fleets, and a lack of standardized protocols, although Albania made progress with recent reforms. Civil protection systems varied and faced resource constraints, with Bosnia and Herzegovina scoring 25/60, Serbia 32/60, and Montenegro 35/60—better but still underfunded. The armed forces offered moderate stability, with Serbia’s larger, mixed-capacity forces (40/60) contrasting with the smaller, NATO-integrated, resource-limited militaries in Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Albania.

On a cross-sectoral level, Montenegro (41.2/60) stood out as the most balanced system, driven by strong firefighting and police sectors, while Bosnia and Herzegovina (29.5/60) scored lowest due to systemic fragmentation. Serbia (36.4/60), Albania (35.6/60), and North Macedonia (32.4/60) remained mid-range. Composite scores echoed this pattern: Serbia (275/360) and Montenegro (270/360) ranked highest, but still fell within the medium readiness category. Albania (243/360) was moderate, while North Macedonia (220/360) and Bosnia and Herzegovina (205/360) lagged behind.

None of the countries reached high readiness levels (≥281/360), and all stayed at a medium level. Sectoral imbalances persist, with police and armed forces appearing relatively stronger, whereas EMS and civil protection remain critical challenges. Institutional fragmentation and dualist structures, especially in Bosnia and Herzegovina and North Macedonia, hamper coordination. Common systemic issues include aging equipment, human-resource shortages, weak coordination, and reliance on external donors for training and modernization. On a positive note, practices like Montenegro’s firefighting, Serbia’s police and armed forces, and Albania’s EMS reforms set promising examples. While legal frameworks exist regionally, their implementation remains inconsistent, with strategies often delayed, underfunded, or fragmented. The regional outlook emphasizes the importance of cross-border cooperation, mutual aid, and harmonized standards in addressing shared risks and resource limitations.

Progressing toward high readiness requires a systematic fleet renewal, lifecycle maintenance, expanded accredited training, effective staff retention strategies, harmonized procedures, integrated asset and incident registries, stronger volunteer integration, and a shift from donation-based procurement to sustainable, multi-year investments. Given shared vulnerabilities, pooling specialized capacities, such as aerial firefighting and CBRN units, across borders and conducting joint exercises is especially crucial. This study faced limitations due to the inconsistent and incomplete nature of the data. Expert judgment was used cautiously to ensure reliability; however, the results should be viewed as indicative. Future efforts should institutionalize regular R2R benchmarking, expand indicators to include response times and survival rates, and incorporate lessons from complex emergencies into doctrine, training, and investments.

The Western Balkans shows moderate preparedness, with notable strengths and systemic weaknesses. Without sustained, coordinated investments in personnel, equipment, governance, and data systems, progress will be uneven and dependent on the generosity of donors. Enhancing regional cooperation and aligning capacities with EU and NATO standards offer the best path toward a resilient future for first responders and the communities they serve.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scientific–Professional Society for Disaster Risk Management, Belgrade (

https://upravljanje-rizicima.com/, accessed April 10, 2025) and the International Institute for Disaster Research, Belgrade, Serbia (

https://idr.edu.rs/, accessed April 10, 2025).

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the use of Grammarly Premium and ChatGPT 4.0 in the process of translating and improving the clarity and quality of the English language in this manuscript. The AI tools assisted in language enhancement but were not involved in developing the scientific content. The authors take full responsibility for the originality, validity, and integrity of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agung, M.F.M.; Rani, B.M.; Millensyah, E.W.; Wijayanto, H.; Sari, S.M.; Perdana, R.N. OPTIMIZATION OF A GOOD GOVERNANCE SYSTEM THROUGH SYNERGY AND COLLABORATION BETWEEN LEADERSHIP AND BUREAUCRACY IN INDONESIA. GEMA PUBLICA 2025, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. Impacts of Flooding Disaster Risk Management Policy for Resilience Building in Pastoral and Agro-Pastoral Community: The Case of Dassenech, Southern Ethiopia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 2025, 7, 137–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, N.A.; Lema, A.T. Conflict Risk Monitoring for Conflict Prevention in Ethiopia: The Case of Ataye Towen, North Shewa, Amhara Region. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 2025, 7, 177–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baćilo, I. Rescue Light Communication System (RLCS): Enhancing Emergency Signaling in Crisis Situations. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 2025, 7, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, P.; Bhuyan, A.; Hodam, S. University Students’ Perception, Knowledge, and Preparedness of Flood Disaster Risk Management in Assam (India). Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 2025, 7, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barre, G.S. Weaknesses of Federalism in Somalia and Required Reforms. East Afr. J. Arts Soc. Sci. 2024, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bela, M.; Fisher, J.R.; Rexhepi, Z.K. CITIZEN KNOWLEDGE AND READINESS FOR DISASTERS IN THE BALKANS. Knowl. Int. J. 2019, 34, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beli, A.; Renner, R.; Cvetković, V.M.; Ivanov, A.; Gačić, J. A Cross-National Study of Disaster Risk Management: Strengths and Weaknesses in Bulgaria, Romania, and Albania with Reflections on Serbia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 2025, 7, 431–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bignami, D.F.; Ambrosi, C.; Bertulessi, M.; Menduni, G.; Pozzoni, M.; Zambrini, F. Governance strategies and tools towards the improvement of emergency management of natural disasters in transboundary areas. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenwei, Q.; Lv, Y. One community at a time: Promoting community resilience in the face of natural hazards and public health challenges. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, M.F.; Falon, S.L.; Kho, M.; Moss, A.; Adler, A.B. Developing resilience in first responders: Strategies for enhancing psychoeducational service delivery. Psychol. Serv. 2022, 19, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowe, A.; Glass, J.S.; Lancaster, M.F.; Raines, J.M.; Waggy, M.R. A Content Analysis of Psychological Resilience Among First Responders and the General Population. SAGE Open 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.; Šišović, V. Capacity Building in Serbia for Disaster and Climate Risk Education. Disaster and Climate Risk Education Insights from Knowledge to Action, edited by Ayse Yildiz and Rajib Shaw, book series Disaster Risk Reduction, Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd., 152 Beach Road, 2024.

- Cvetković, V. Interventno-spasilačke službe u vanrednim situacijama [Emergency and rescue services in emergencies]. Beograd: Zadužbina Andrejević. 2013.

- Cvetković, V.M. Risk Perception of Building Fires in Belgrade. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 2019, 1, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.M. Tactical Approaches to Protection and Rescue in Traffic Accident-Induced Disasters. Firefighting and rescue operations in the aftermath of traffic accidents involving electric vehicles. International scientific and practical conference, Collection of Papers, 2024; pp. 87–97.

- Cvetković, V.M.; Dragašević, A.; Protić, D.; Janković, B.; Nikolić, N.; Milošević, P. Fire safety behavior model for residential buildings: Implications for disaster risk reduction. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.M.; Renner, R.; Jakovljević, V. Industrial Disasters and Hazards: From Causes to Consequences — a Holistic Approach to Resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 2024, 6, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.M.; Tanasić, J.; Renner, R.; Rokvić, V.; Beriša, H. Comprehensive Risk Analysis of Emergency Medical Response Systems in Serbian Healthcare: Assessing Systemic Vulnerabilities in Disaster Preparedness and Response. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.M.; Nikolić, N.; Nenadić, U.R.; Öcal, A.; Noji, E.K.; Zečević, M. Preparedness and Preventive Behaviors for a Pandemic Disaster Caused by COVID-19 in Serbia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, 17, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.M.; Nikolić, N.; Ocal, A.; Martinović, J.; Dragašević, A. A Predictive Model of Pandemic Disaster Fear Caused by Coronavirus (COVID-19): Implications for Decision-Makers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.M.; Renner, R.; Aleksova, B.; Lukić, T. Geospatial and Temporal Patterns of Natural and Man-Made (Technological) Disasters (1900–2024): Insights from Different Socio-Economic and Demographic Perspectives. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V. , Šišović, V. (2024). Community Disaster Resilience in Serbia. Belgrade: Scientific-Professional Society for Disaster Risk Management.

- Cvetković, V.M.; Tanasić, J.; Ocal, A.; Kešetović, Ž.; Nikolić, N.; Dragašević, A. Capacity Development of Local Self-Governments for Disaster Risk Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 10406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dada, K.S.J.; Hamza, J.M.; Mohammed, H.A. Disaster Risk Management in Libraries and Information Centers: Global Strategies, Challenges, Policy and Recommendations. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 2025, 7, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayberry, L.; Fisher, J. Applied Learning on A Study Abroad: Teaching Community Emergency Preparedness in the Balkans. J. Appl. Learn. High. Educ. 2023, 09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkova, E.; Zanesco, A.P.; Rogers, S.L.; Jha, A.P. Is resilience trainable? An initial study comparing mindfulness and relaxation training in firefighters. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 285, 112794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doody, C. , Robertson, L., Cox, K., Bogue, J., Egan, J., & Sarma, K. (2021). Pre-deployment programmes for building resilience in military and frontline emergency service personnel. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12.

- Draçi, P.; Kraja, G.; Themelko, H. The Regional Cooperation of the Western Balkans and the Challenges on the Path of Integration in the European Union. Interdiscip. J. Res. Dev. 2022, 9, 96–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, J.; Carter, H.; Cocking, C.; Ntontis, E.; Guven, S.T.; Amlôt, R. Facilitating Collective Psychosocial Resilience in the Public in Emergencies: Twelve Recommendations Based on the Social Identity Approach. Front. Public Heal. 2019, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J. , Chang, M. W., Lee, K. and Toutanova, K., 2019. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: 1; p. 4171. [Google Scholar]

- Fedajev, A.; Panić, M.; Živković, Ž. Western Balkan countries’ innovation as determinant of their future growth and development. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2024, 38, 447–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafuri, A.; Muftuler-Bac, M. Caught between stability and democracy in the Western Balkans: a comparative analysis of paths of accession to the European Union. East Eur. Politi- 2020, 37, 267–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozdanić, G. , Cvetković, V., Lukić, T., & Ivanov, A. (2024). Comparative analysis and prediction of sustainable development in earthquake preparedness: A cross-cultural perspective on Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia. Preprint.

- Grozdanić, G.; Cvetković, V.M.; Lukić, T.; Ivanov, A. Sustainable Earthquake Preparedness: A Cross-Cultural Comparative Analysis in Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Mallinson, D.J.; Ortiz, S.E.; Iulo, L.D. Collaborative governance challenges in energy efficiency and conservation: The case of Pennsylvania. Util. Policy 2024, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanspal, M.S.; Behera, B. Role of Emerging Technology in Disaster Management in India: An Overview. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 2024, 6, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanspal, M.S.; Behera, B. Disaster Management Laws in India: Past, Present, and Future Directions. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 2025, 7, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearne, E. ; Close Improving the Efficiency of Public Investment in Infrastructure in Belgium. Sel. Issues Pap. 2025, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperiale, A.J.; Vanclay, F. Conceptualizing community resilience and the social dimensions of risk to overcome barriers to disaster risk reduction and sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 891–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inusa, M.; Nnaemeka, E.C.; Nyomo, J.D.; Osawe, I.E.; Obadaki, Y.Y.; Isma'IL, M.; Ismail, A.; Bichi, A.A. Nature and Extent of Flood Risk Downstream of the Kubanni Dam, Kaduna State, Nigeria. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 2025, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A. , & Cvetković, V. (2016). Prirodne katastrofe—geoprostorna i vremenska distribucija [Natural disasters—Geospatial and temporal distribution]. Skopje: Fakultet za bezbednost.

- Janković, L.; Cvetković, V.M.; Gačić, J.; Renner, R.; Jakovljević, V. Integrating Psychosocial Support into Emergency and Disaster Management and Public Safety: The Role of the Red Cross of Serbia. Int. J. Contemp. Secur. Stud. 2025, 1, 99–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Ma, J.; Chen, X. Multi-regional collaborative mechanisms in emergency resource reserve and pre-dispatch design. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2024, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovičić, R.; Gostimirović, L.; Milašinović, S. Use of New Technologies in the Field of Protection and Rescue During Disasters. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 2024, 6, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovičić, R.; Gostimirović, L.; Milašinović, S. Use of New Technologies in the Field of Protection and Rescue During Disasters. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 2024, 6, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, S.; Shand, F.; Lal, T.J.; Mott, B.; A Bryant, R.; Harvey, S.B. Resilience@Work Mindfulness Program: Results From a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial With First Responders. J. Med Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurisic, D.; Marčeta, Ž. Collaborative Gaps: Investigating the Role of Civilian-Religious Authority Disconnection in Psychosocial Support Provision During the 2014 Floods. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 2024, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaim, A.; Bodas, M.; Camacho, N.A.; Peleg, K.; Ragazzoni, L. Enhancing disaster response of emergency medical teams through “TEAMS 3.0” training package—Does the multidisciplinary intervention make a difference? Front. Public Heal. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanteler, D.; Bakouros, I. A collaborative framework for cross-border disaster management in the Balkans. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanteler, D.; Bakouros, I. A collaborative framework for cross-border disaster management in the Balkans. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanteler, D.; Bakouros, I. Enhancing cross-border disaster management in the Balkans: a framework for collaboration part I. J. Innov. Entrep. 2024, 13, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.B.; Bergman, A.L.; Christopher, M.; Bowen, S.; Hunsinger, M. Role of Resilience in Mindfulness Training for First Responders. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 1373–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmaker, R. Stray Dogs in Urban Bangladesh: A Zoonotic Disaster Risk and Policy Challenge. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 2025, 7, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelmendi, K.; Hamby, S. Resilience After Trauma in Kosovo and Southeastern Europe: A Scoping Review. Trauma, Violence, Abus. 2022, 24, 2333–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketelaars, E.; Gaudin, C.; Flandin, S.; Poizat, G. Resilience training for critical situation management. An umbrella and a systematic literature review. Saf. Sci. 2023, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollias, C.; Messis, P.; Stergiou, A.; Zouboulakis, M. Governance quality in Western Balkan countries: are they converging with the EU? J. Contemp. Eur. Stud. 2024, 33, 590–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberherr, E. , & Ingold, K. (2019). Actors in water governance: Barriers and bridges for coordination. Water, 11(2), 326.

- Liu, J.; Guo, Y.; An, S.; Lian, C. A Study on the Mechanism and Strategy of Cross-Regional Emergency Cooperation for Natural Disasters in China—Based on the Perspective of Evolutionary Game Theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 11624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoj, B.; Baker, A.H. Communication challenges in emergency response. Commun. ACM 2007, 50, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marceta, Z. , & Jurišić, D. (2024). Psychological preparedness of the rescuers and volunteers: A case study of 2023 Türkiye earthquake. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management, 6(1), 25–39.

- Matewos, K. Domestic Hiking Tourism for Post-COVID Recovery and Transformation. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 2025, 7, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matkovski, B.; Đokić, D.; Zekić, S.; Jurjević, Ž. Determining Food Security in Crisis Conditions: A Comparative Analysis of the Western Balkans and the EU. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matkovski, B.; Zekić, S.; Đokić, D.; Jurjević, Ž.; Đurić, I. Export Competitiveness of Agri-Food Sector during the EU Integration Process: Evidence from the Western Balkans. Foods 2021, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metić, A. The Significance and Role of Police Officers in Building the School as a Safe Environment for All Students. Int. J. Contemp. Secur. Stud. 2025, 1, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan, C. Refugees at the Gates of the EU: Civic Initiatives and Grassroots Responses to the Refugee Crisis along the Western Balkans Route. J. Balk. Near East. Stud. 2018, 21, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenković, D. Theoretical, Institutional and Organizational Aspects of the Integrated Disaster Risk Reduction System: Towards a Deeper Understanding of Disaster Resilience in Serbia. Int. J. Contemp. Secur. Stud. 2025, 1, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.; Abhinay, K.; Rahman, M.; Yangdhen, S.; Sen, S.; Adhikari, B.R.; Nianthi, R.; Sachdev, S.; Shaw, R. Extent and evaluation of critical infrastructure, the status of resilience and its future dimensions in South Asia. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, S.A.; Agha, M.S.A.; Masood, T. The Role of Collaborative Resource Sharing in Supply Chain Recovery During Disruptions: A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 115603–115623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnari, E. (2008). The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. International Trade Statistics Yearbook 2017, Volume I, 455–463. [Google Scholar]

- O’tOole, M.; Mulhall, C.; Eppich, W. Breaking down barriers to help-seeking: preparing first responders’ families for psychological first aid. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2022, 13, 2065430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obergassel, W.; Xia-Bauer, C.; Thomas, S. Strengthening global climate governance and international cooperation for energy-efficient buildings. Energy Effic. 2023, 16, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- cal, A. (2021). Disaster management in Turkey: A spatial approach. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management, 3(1), 15–22.

- Öcal, F.E.; Torun, S. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence for Enhanced Disaster Response Coordination. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 2025, 7, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.; Leitheiser, A.; Atchison, C.; Larson, S.; Homzik, C. Public Health and Terrorism Preparedness: Cross-Border Issues. Public Heal. Rep. 2005, 120, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, B. (2018). The challenge of policy coordination. Policy Design and Practice, 1(1), 1–11.

- Ponder, W.N.; Walters, K.; Simons, J.S.; Simons, R.M.; Jetelina, K.K.; Carbajal, J. Network analysis of distress, suicidality, and resilience in a treatment seeking sample of first responders. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 320, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, K.K.; Yuksel, M.; Seferoglu, H.; Chen, J.; Blalock, R.A. Resilient Communication for Dynamic First Responder Teams in Disaster Management. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2022, 60, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, A.; Larson, A.M.; Myers, R.; Trench, T. Inter-sectoral and multilevel coordination alone do not reduce deforestation and advance environmental justice: Why bold contestation works when collaboration fails. Environ. Plan. C: Politi- Space 2018, 36, 1437–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, R.; Cvetković, V.M.; Lieftenegger, N. Dealing with High-Risk Police Activities and Enhancing Safety and Resilience: Qualitative Insights into Austrian Police Operations from a Risk and Group Dynamic Perspective. Safety 2025, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S. Smart Life Safety Jacket for Rescuers. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 2025, 7, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schout, A.; Jordan, A. Coordinated European Governance: Self-Organizing or Centrally Steered? Public Adm. 2005, 83, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahverdi, B.; Tariverdi, M.; Miller-Hooks, E. Assessing hospital system resilience to disaster events involving physical damage and Demand Surge. Socio-Economic Plan. Sci. 2020, 70, 100729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simona, T.; Taupo, T.; Antunes, P. A Scoping Review on Agency Collaboration in Emergency Management Based on the 3C Model. Inf. Syst. Front. 2021, 25, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Hwang, J.; Seo, I. Collaboration risk, vulnerability, and resource sharing in disaster management networks. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2024, 84, 48–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopha, B.M. Barriers to Coordination Among Humanitarian Organizations: Insights from Practitioners in a Developing Country. 2023 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, SingaporeDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 0475–0479.

- Tan, L.; Deady, M.; Mead, O.; Foright, R.M.; Brenneman, E.M.; Bryant, R.A.; Harvey, S.B. Yoga resilience training to prevent the development of posttraumatic stress disorder in active-duty first responders: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Trauma: Theory, Res. Pr. Policy 2025, 17, 1108–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trbojević, M.; Radovanović, M. Disaster Management in the Western Balkans Territory – Condition Analysis and Conceptualisation of the Cross-Border Cooperation Model. J. Homel. Secur. Emerg. Manag. 2024, 21, 243–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushabe, G.; Rukundo, P.M.; Kaaya, A.N.; Nahalomo, A.; Nateme, N.C.; Iversen, P.O.; Andreassen, B.A.; Rukooko, A.B. Retrogressive or Misplaced Priorities? An Assessment of Public Expenditure for Food Security and Disaster Risk Reduction in Uganda. Int. J. Disaster Risk Manag. 2025, 7, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDRR. (2023). Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction (GAR, 2023). United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Retrieved from https://www.undrr.org.

- Vidović, N.; Beriša, H. Economic Aspects of Cyber Security: Socio-Financial Consequences of Cyber Attacks. Int. J. Contemp. Secur. Stud. 2025, 1, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vračević, N. Strategic Roles of Private Military Companies: The Evolution and Privatization of Warfare in the Context of Contemporary Global Conflicts. Int. J. Contemp. Secur. Stud. 2025, 1, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.S.; Bollmann, A. A Strategy for Rolling out Climate De-risk Insurance through Regional Collaboration. Asia-Pacific J. Risk Insur. [CrossRef]

- Wild, J.; Greenberg, N.; Moulds, M.L.; Sharp, M.-L.; Fear, N.; Harvey, S.; Wessely, S.; Bryant, R.A. Pre-incident Training to Build Resilience in First Responders: Recommendations on What to and What Not to Do. Psychiatry 2020, 83, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanakiev, Y.; Bernal, S.L.; Navajo, A.M.; Stoianov, N.; Gil Perez, M.; Curto, M.C.M. Approach to harmonisation of technological solutions, operating procedures, preparedness and cross-sectorial collaboration opportunities for first aid response in cross-border mass-casualty incidents. ARES 2023: The 18th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, ItalyDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–9.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).