Submitted:

02 October 2025

Posted:

03 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

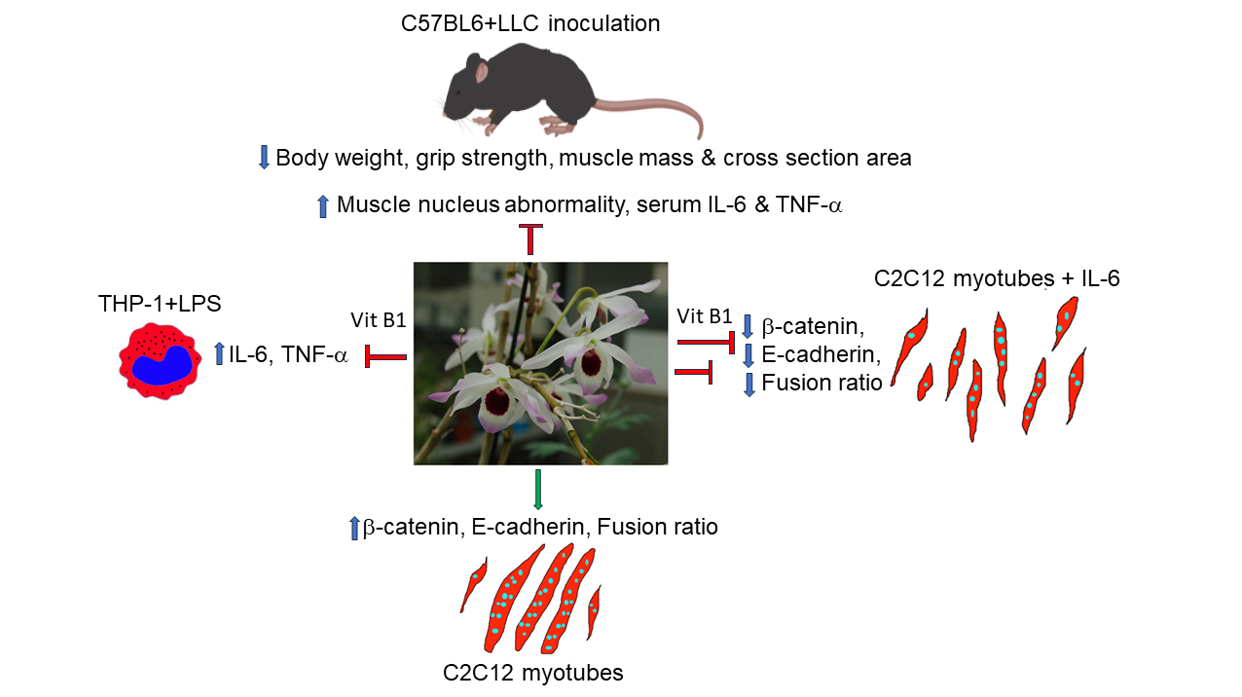

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. DTT Extraction and HPLC Procedure

2.2. Animal Model

2.3. Food Intake, Body Weight, and Grip Strength

2.4. Histological Analysis

2.5. Cell Culture, Treatments, and Transfection

2.6. Giemsa Staining and Measurement of Myotube Diameters

2.7. Immunostaining

2.8. Cytokines Analysis

2.9. Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analysis

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

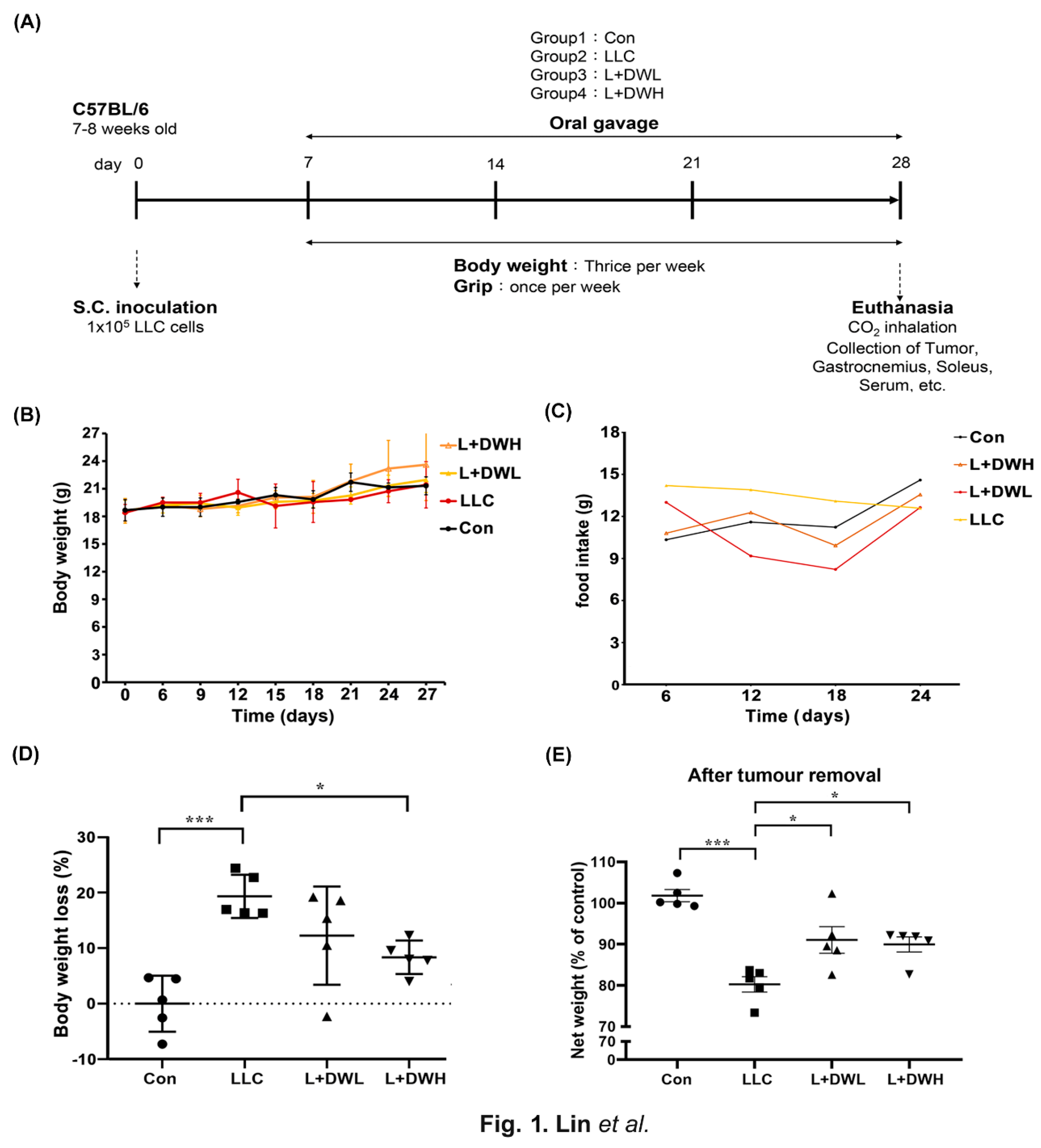

3.1. DTT Water Extracts Attenuate the Loss of Tumor-Free Body Mass in LLC Tumor-Bearing Mice

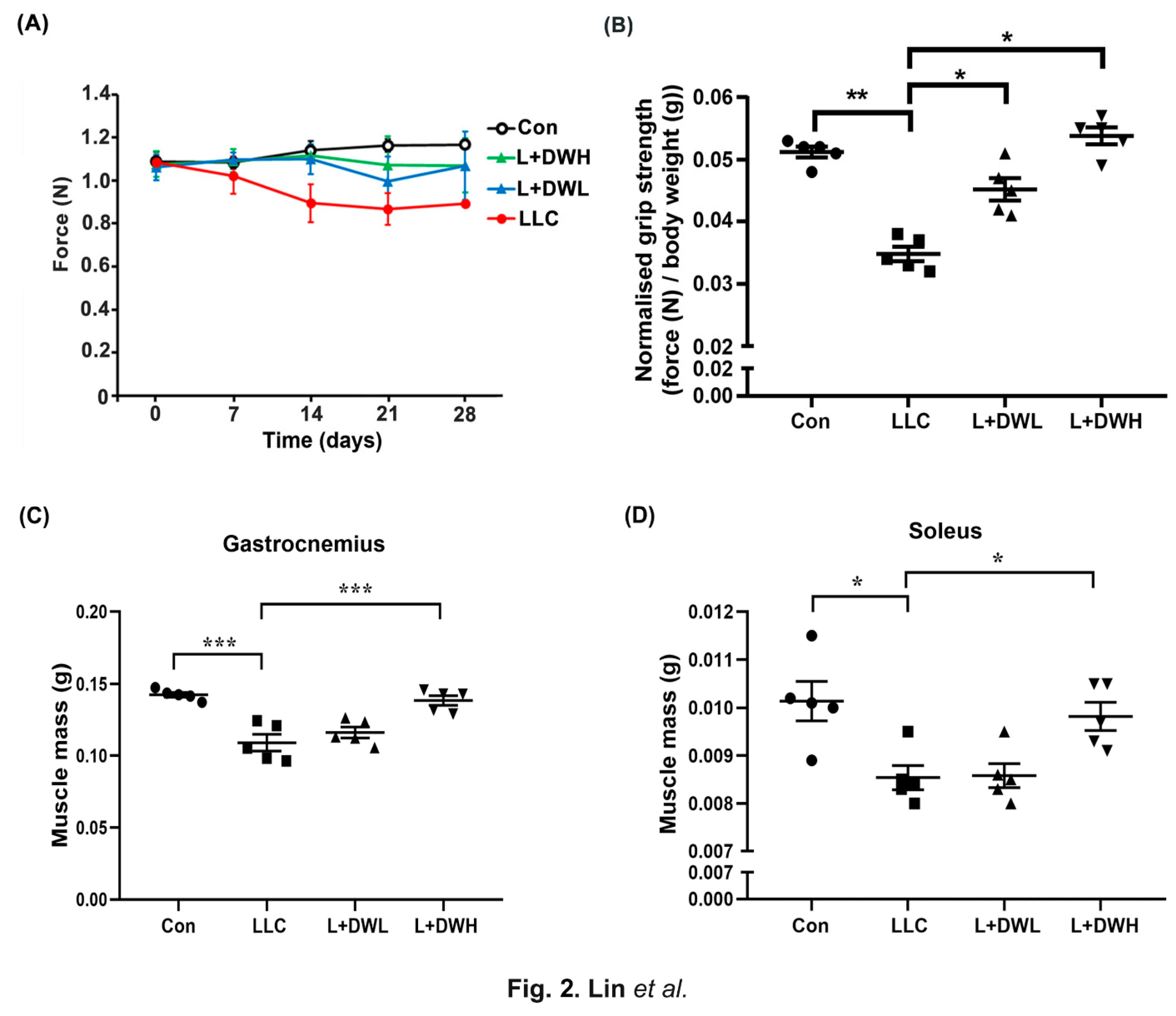

3.2. DTT Water Extracts Recover Muscle Mass and Grip Strength in LLC Tumor-Bearing Mice

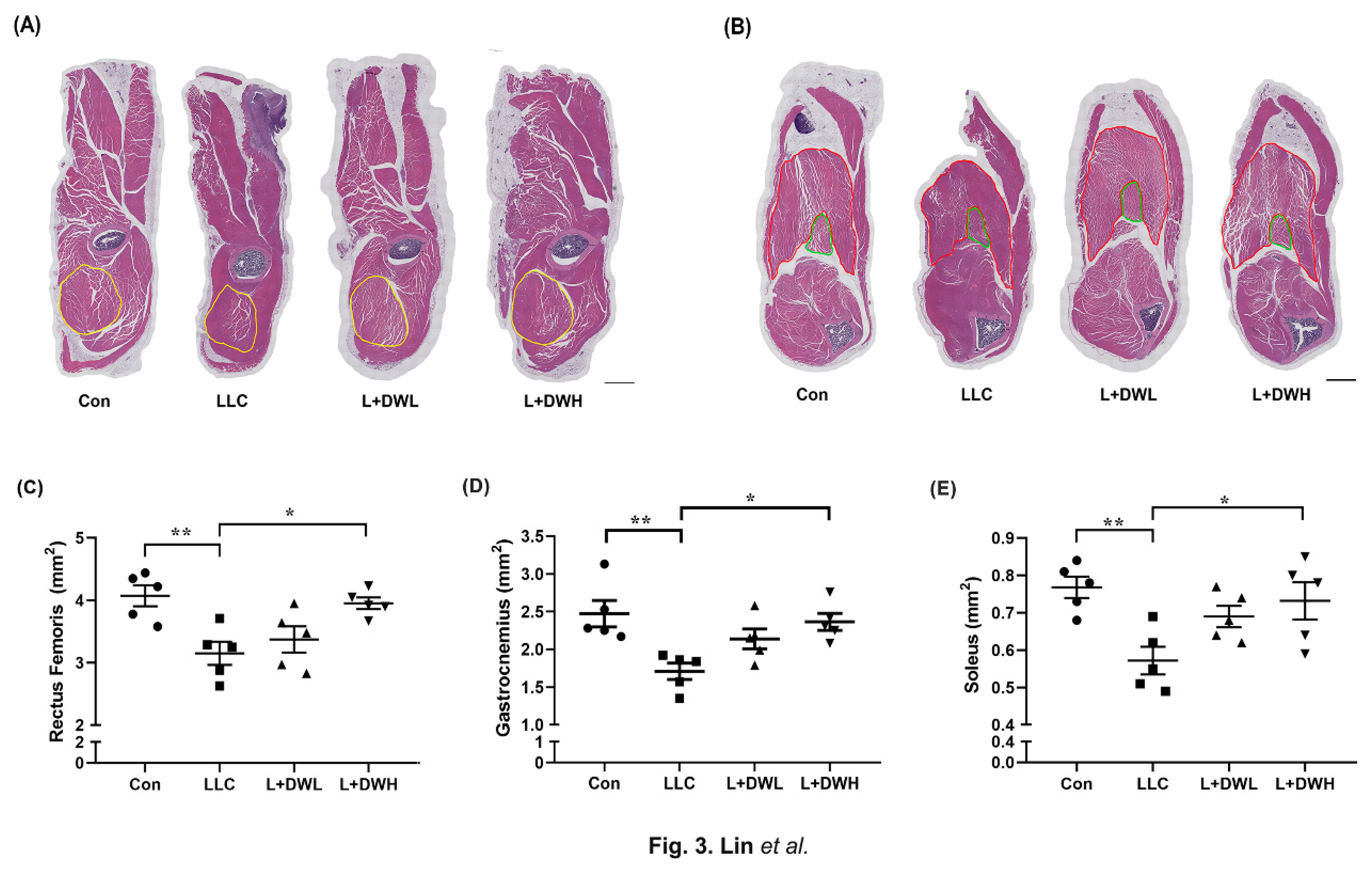

3.3. DTT Water Extracts Recover the Cross-Section Area of the Hindlimb in LLC Tumor-Bearing Mice

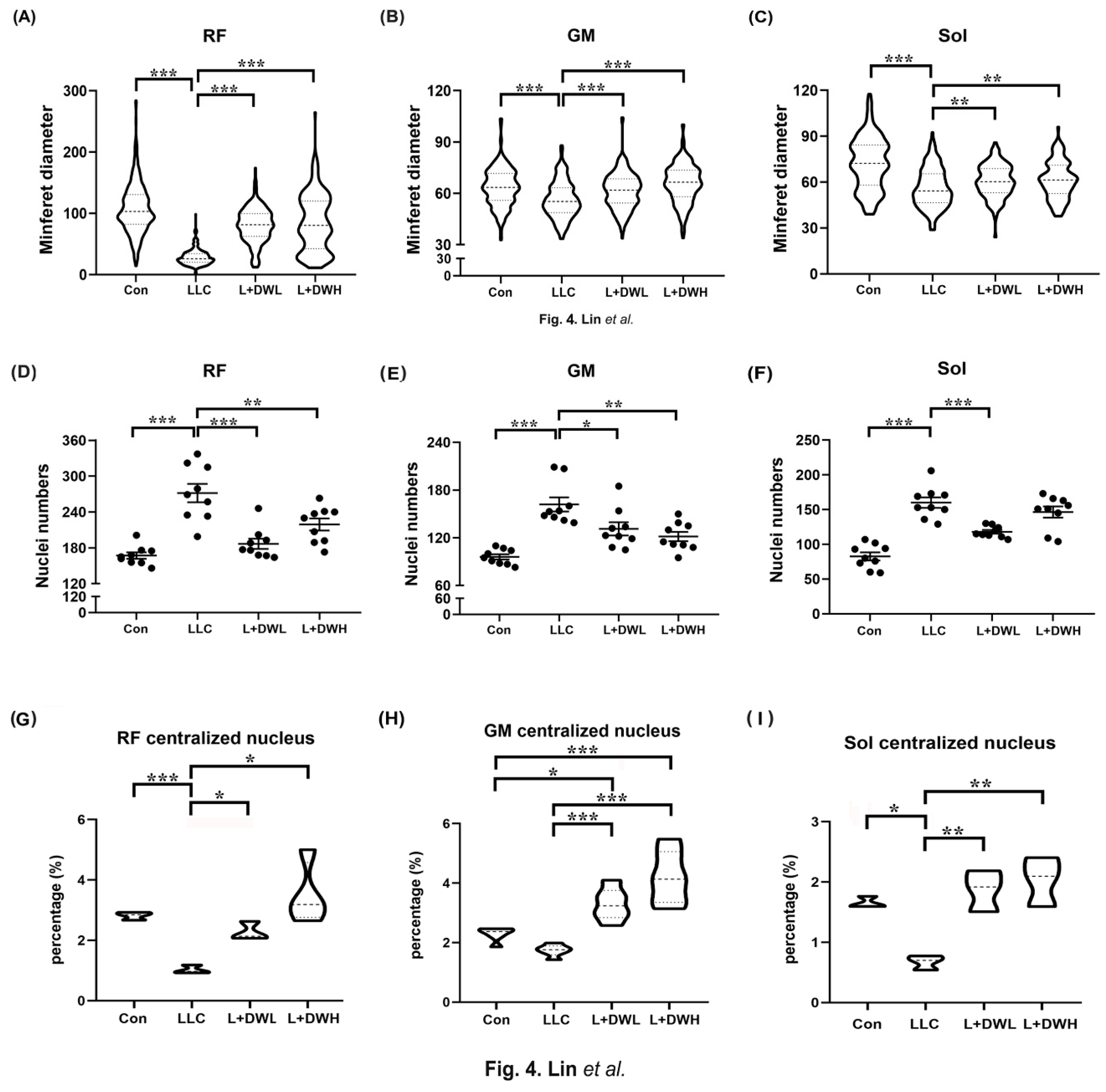

3.4. DTT Water Extracts Alleviate Myofiber Atrophy Induced by LLC Tumor

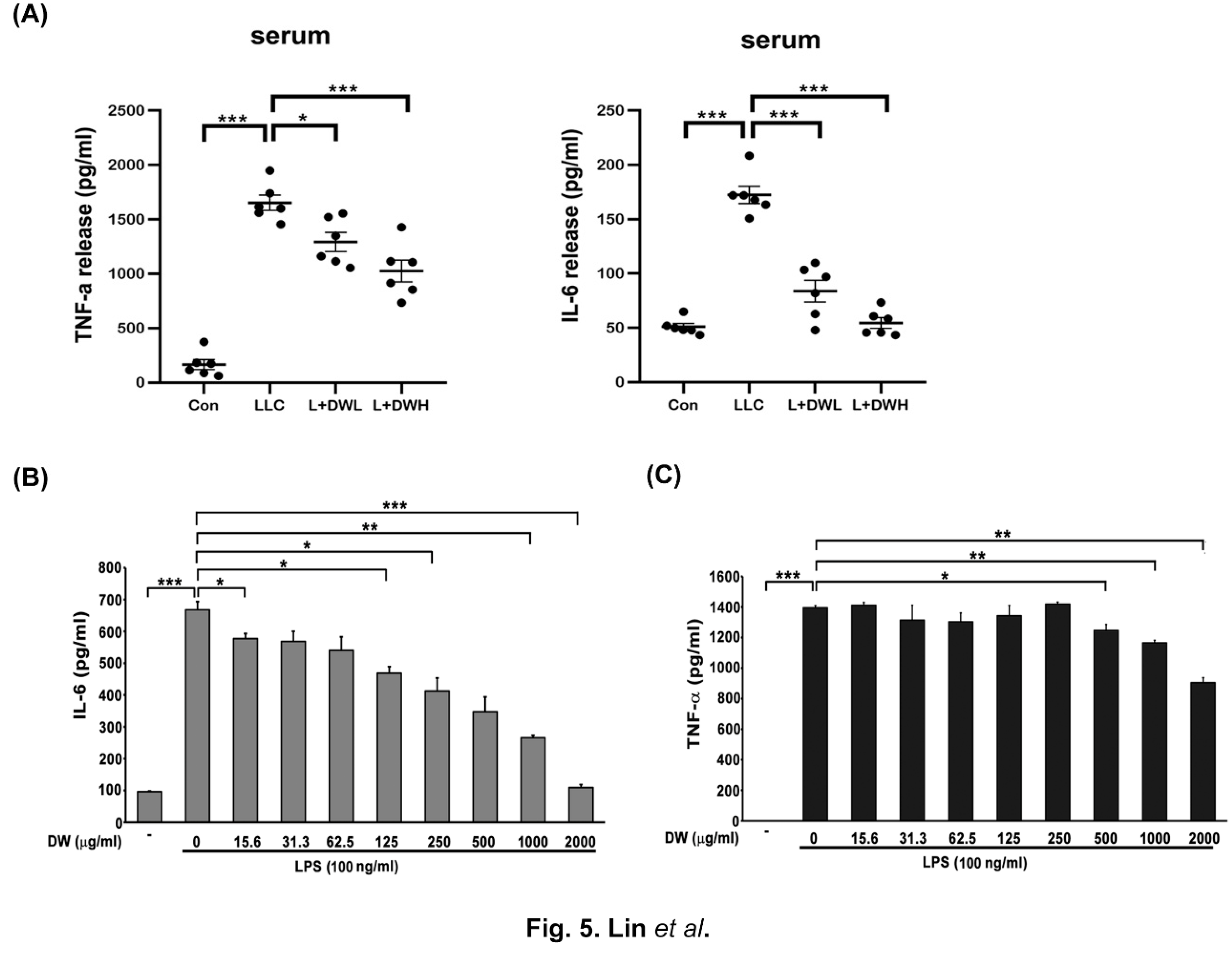

3.5. DTT Water Extracts Attenuate the Levels of Inflammatory Cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α Both In Vitro and In Vivo

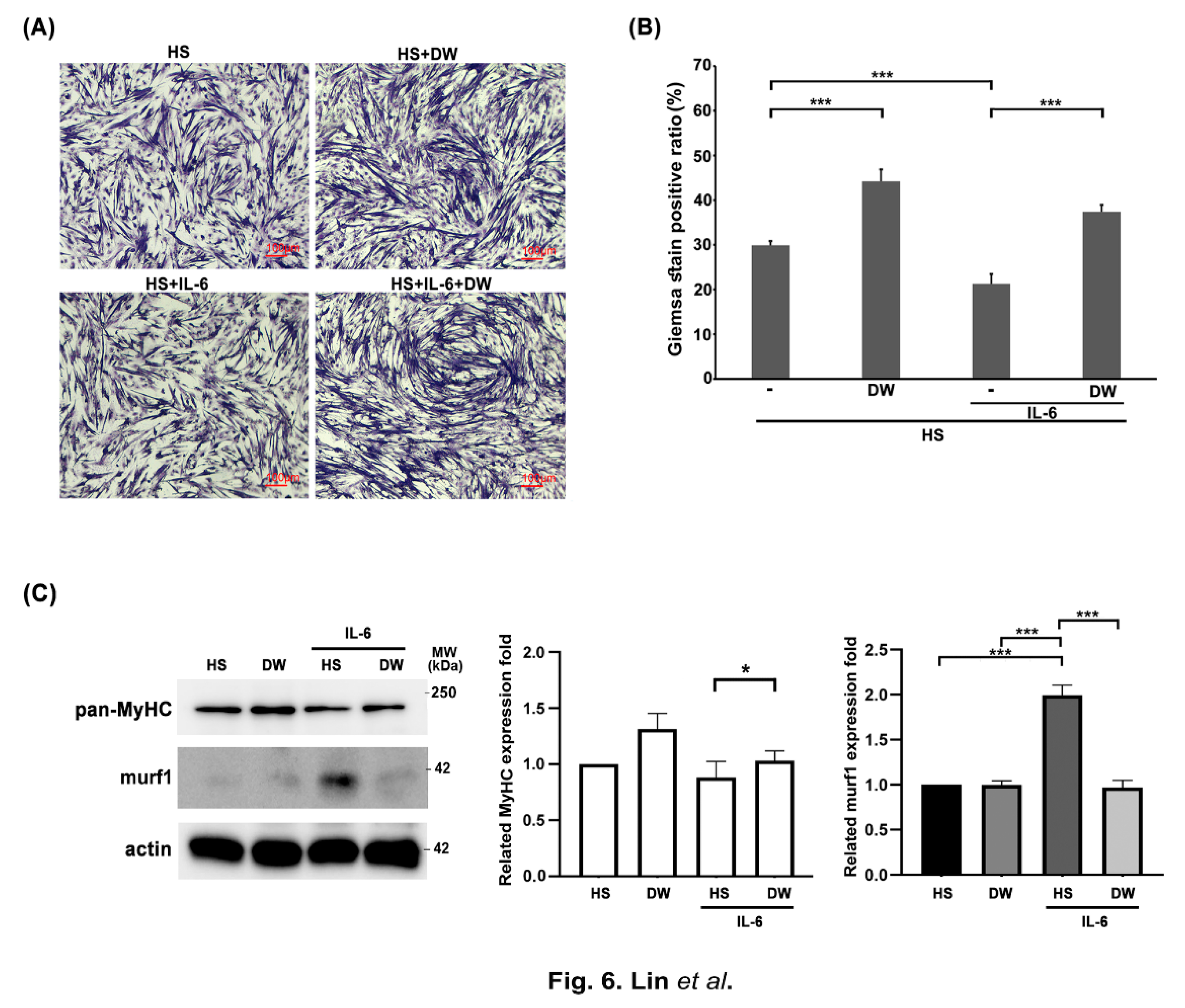

3.6. DTT Water Extracts Protect C2C12 Differentiation Against IL-6

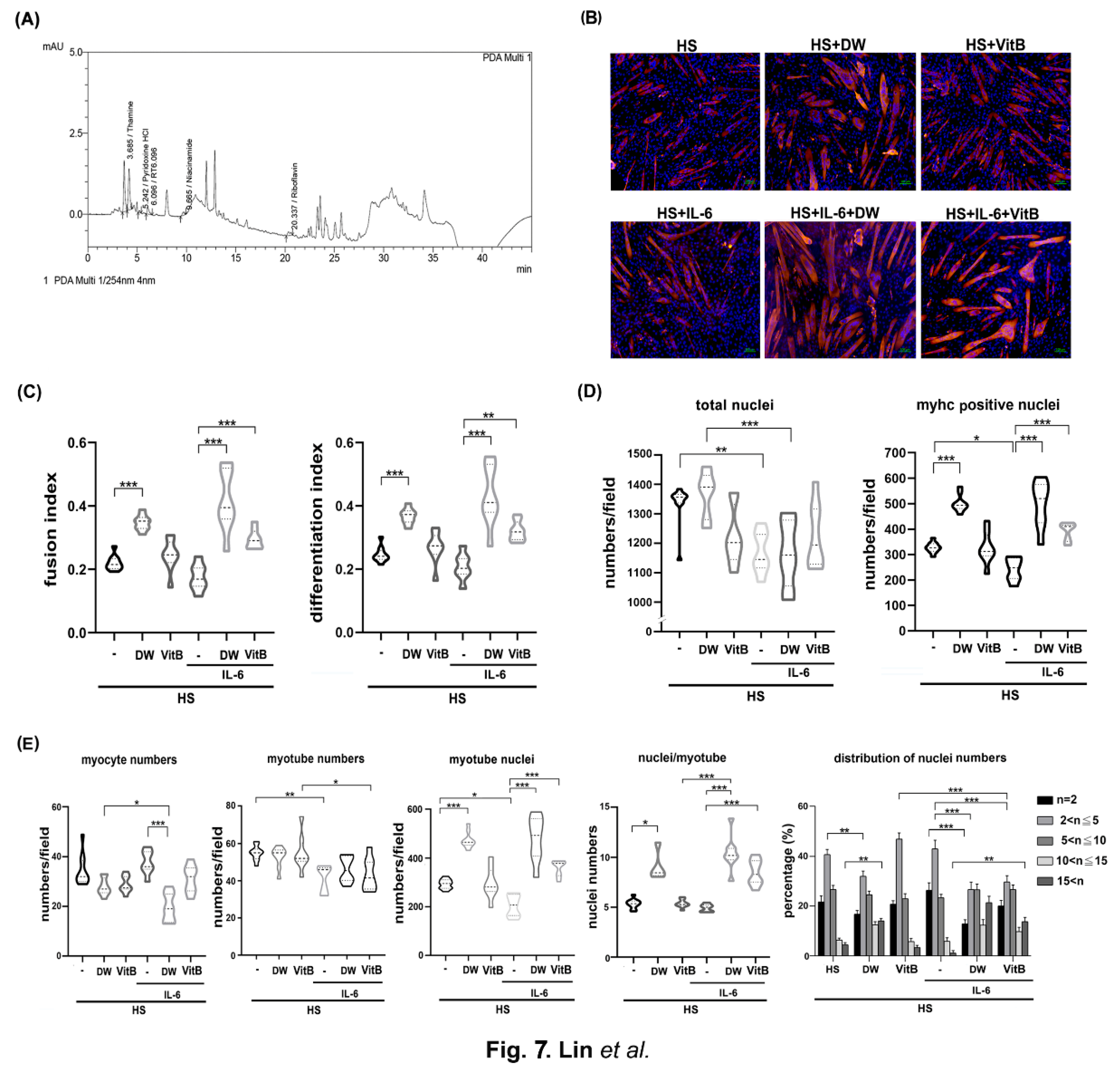

3.7. Vitamin B1 Is an Ingredient of DTT Water Extracts Involved in Protecting Differentiated C2C12 Cells Against IL-6

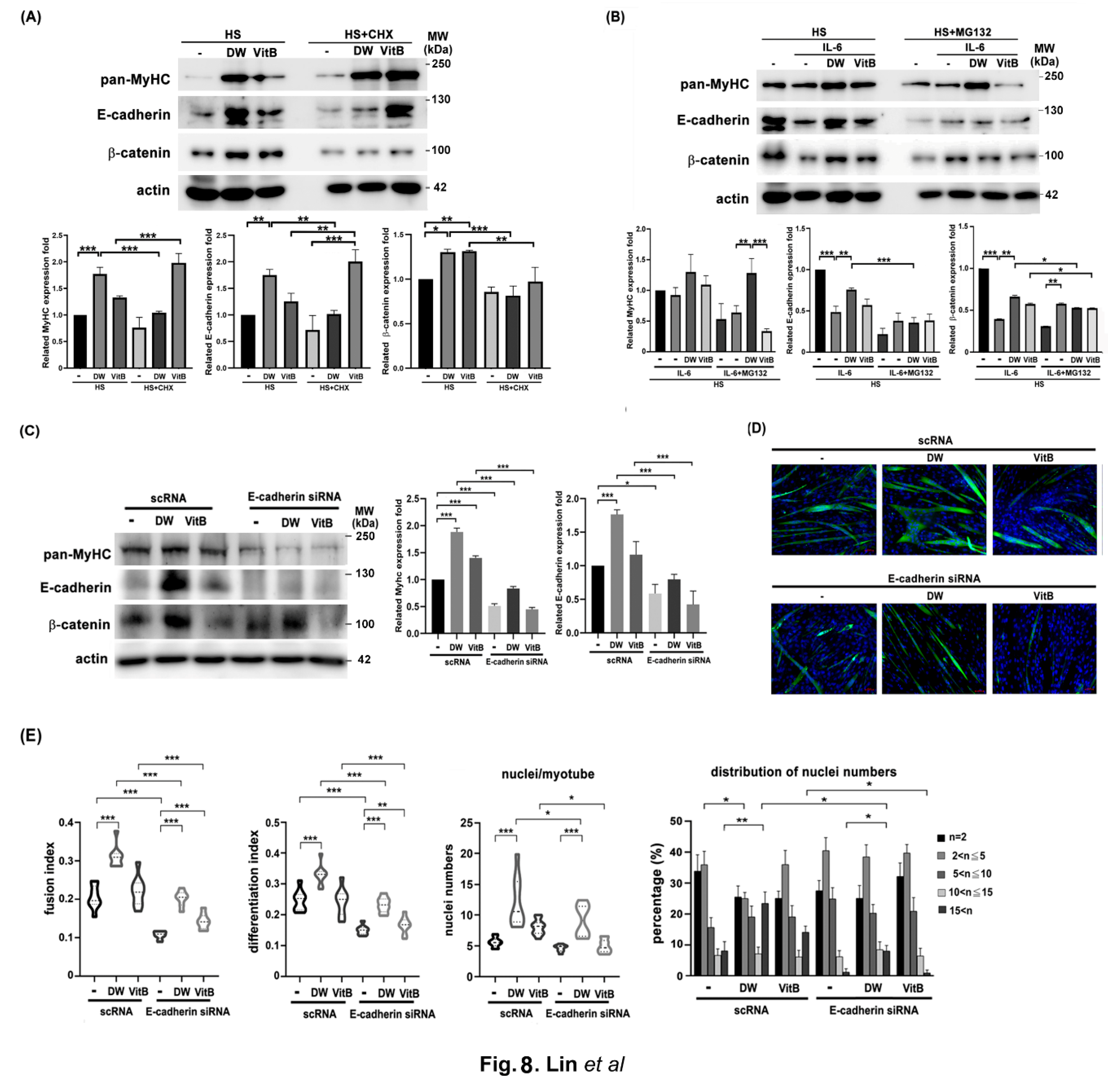

3.8. E-Cadherin Is Required for Multinucleation of C2C12 Myotubes Induced by DTT Water Extracts or Vitamin B1

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karagounis, L. G.; Hawley, J. A., Skeletal muscle: increasing the size of the locomotor cell. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 2010, 42, (9), 1376-1379.

- Dave, H. D.; Shook, M.; Varacallo, M., Anatomy, skeletal muscle. In StatPearls [Internet], StatPearls Publishing: 2021.

- Hindi, S. M.; Tajrishi, M. M.; Kumar, A., Signaling mechanisms in mammalian myoblast fusion. Science signaling 2013, 6, (272), re2-re2.

- Bottinelli, R.; Reggiani, C., Human skeletal muscle fibres: molecular and functional diversity. Progress in biophysics and molecular biology 2000, 73, (2-4), 195-262.

- Rosen, G. D.; Sanes, J. R.; LaChance, R.; Cunningham, J. M.; Roman, J.; Dean, D. C. J. C., Roles for the integrin VLA-4 and its counter receptor VCAM-1 in myogenesis. 1992, 69, (7), 1107-1119.

- Chang, Y.-H.; Tsai, J.-N.; Chen, T.-L.; Ho, K.-T.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Hsiao, C.-W.; Shiau, M.-Y. J. M. o. I., Interleukin-4 promotes myogenesis and boosts myocyte insulin efficacy. 2019, 2019.

- Kurosaka, M.; Ogura, Y.; Sato, S.; Kohda, K.; Funabashi, T. J. S. M., Transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6) is an inhibitory factor for adult myogenesis. 2021, 11, (1), 14.

- Wu, Z.; Woodring, P. J.; Bhakta, K. S.; Tamura, K.; Wen, F.; Feramisco, J. R.; Karin, M.; Wang, J. Y.; Puri, P. L. J. M.; biology, c., p38 and extracellular signal-regulated kinases regulate the myogenic program at multiple steps. 2000, 20, (11), 3951-3964.

- Suzuki, A.; Pelikan, R. C.; Iwata, J. J. M.; biology, c., WNT/β-catenin signaling regulates multiple steps of myogenesis by regulating step-specific targets. 2015.

- Frontera, W. R.; Ochala, J., Skeletal muscle: a brief review of structure and function. Calcified tissue international 2015, 96, 183-195.

- Evans, W. J., Skeletal muscle loss: cachexia, sarcopenia, and inactivity. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2010, 91, (4), 1123S-1127S.

- Penna, F.; Ballarò, R.; Beltrá, M.; De Lucia, S.; Costelli, P., Modulating metabolism to improve cancer-induced muscle wasting. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2018, 2018.

- Holecek, M., Muscle wasting in animal models of severe illness. International journal of experimental pathology 2012, 93, (3), 157-171.

- Nishikawa, H.; Goto, M.; Fukunishi, S.; Asai, A.; Nishiguchi, S.; Higuchi, K., Cancer cachexia: its mechanism and clinical significance. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, (16), 8491.

- Aoyagi, T.; Terracina, K. P.; Raza, A.; Matsubara, H.; Takabe, K., Cancer cachexia, mechanism and treatment. World journal of gastrointestinal oncology 2015, 7, (4), 17.

- Vaughan, V. C.; Martin, P.; Lewandowski, P. A., Cancer cachexia: impact, mechanisms and emerging treatments. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle 2013, 4, 95-109.

- Castaneda, C., Muscle wasting and protein metabolism. Journal of Animal Science 2002, 80, (E-suppl_2), E98-E105.

- Argilés, J. M.; Busquets, S.; Stemmler, B.; López-Soriano, F. J., Cancer cachexia: understanding the molecular basis. Nature Reviews Cancer 2014, 14, (11), 754-762.

- Peixoto da Silva, S.; Santos, J. M.; Costa e Silva, M. P.; Gil da Costa, R. M.; Medeiros, R., Cancer cachexia and its pathophysiology: links with sarcopenia, anorexia and asthenia. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle 2020, 11, (3), 619-635.

- Dodson, S.; Baracos, V. E.; Jatoi, A.; Evans, W. J.; Cella, D.; Dalton, J. T.; Steiner, M. S., Muscle wasting in cancer cachexia: clinical implications, diagnosis, and emerging treatment strategies. Annual review of medicine 2011, 62, 265-279.

- Baracos, V. E.; Mazurak, V. C.; Bhullar, A. S., Cancer cachexia is defined by an ongoing loss of skeletal muscle mass. Ann Palliat Med 2019, 8, (1), 3-12.

- Patel, H. J.; Patel, B. M., TNF-α and cancer cachexia: Molecular insights and clinical implications. Life sciences 2017, 170, 56-63.

- Bonetto, A.; Aydogdu, T.; Kunzevitzky, N.; Guttridge, D. C.; Khuri, S.; Koniaris, L. G.; Zimmers, T. A., STAT3 activation in skeletal muscle links muscle wasting and the acute phase response in cancer cachexia. PloS one 2011, 6, (7), e22538.

- Pelosi, M.; De Rossi, M.; Barberi, L.; Musarò, A., IL-6 impairs myogenic differentiation by downmodulation of p90RSK/eEF2 and mTOR/p70S6K axes, without affecting AKT activity. BioMed research international 2014, 2014.

- Adams, V.; Mangner, N.; Gasch, A.; Krohne, C.; Gielen, S.; Hirner, S.; Thierse, H.-J.; Witt, C. C.; Linke, A.; Schuler, G., Induction of MuRF1 is essential for TNF-α-induced loss of muscle function in mice. Journal of molecular biology 2008, 384, (1), 48-59.

- Garcia, V. R.; López-Briz, E.; Sanchis, R. C.; Perales, J. L. G.; Bort-Martí, S., Megestrol acetate for treatment of anorexia-cachexia syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, (3).

- Nakanishi, Y.; Higuchi, J.; Honda, N.; Komura, N., Pharmacological profile and clinical efficacy of anamorelin HCl (ADLUMIZ® Tablets), the first orally available drug for cancer cachexia with ghrelin-like action in Japan. Nihon Yakurigaku zasshi. Folia Pharmacologica Japonica 2021, 156, (6), 370-381.

- Bulchandani, D.; Nachnani, J.; Amin, A.; May, J., Megestrol acetate—associated adrenal insufficiency. The American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy 2008, 6, (3), 167-172.

- FARRAR, D. J., Megestrol acetate: promises and pitfalls. AIDS Patient Care and STDs 1999, 13, (3), 149-152.

- Wachtel-Galor, S.; Benzie, I. F., Herbal medicine. Lester Packer, Ph. D. 2011, 1.

- SONG, G.-Q., Research progress on pharmacological activities of medical plants from Dendrobium Sw. Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs 2014, 2576-2580.

- Teoh, E. S.; Teoh, E. S., Traditional Chinese Medicine, Korean Traditional Herbal Medicine, and Japanese Kanpo Medicine. Medicinal Orchids of Asia 2016, 19-31.

- Ramesh, T.; Koperuncholan, M.; Praveena, R.; Ganeshkumari, K.; Vanithamani, J.; Muruganantham, P.; Renganathan, P., Medicinal properties of some Dendrobium orchids–A review. Journal of Applied and Advanced Research 2019, 4, (4), 119-128.

- Xing, X.; Cui, S. W.; Nie, S.; Phillips, G. O.; Goff, H. D.; Wang, Q., A review of isolation process, structural characteristics, and bioactivities of water-soluble polysaccharides from Dendrobium plants. Bioactive Carbohydrates and Dietary Fibre 2013, 1, (2), 131-147.

- Teixeira da Silva, J. A.; Ng, T. B., The medicinal and pharmaceutical importance of Dendrobium species. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2017, 101, 2227-2239.

- Yang, L.-C.; Hsieh, C.-C.; Wen, C.-L.; Chiu, C.-H.; Lin, W.-C., Structural characterization of an immunostimulating polysaccharide from the stems of a new medicinal Dendrobium species: Dendrobium Taiseed Tosnobile. International journal of biological macromolecules 2017, 103, 1185-1193.

- Yang, L.-C.; Liao, J.-W.; Wen, C.-L.; Lin, W.-C., Subchronic and Genetic Safety Assessment of a New Medicinal Dendrobium Species: Dendrobium Taiseed Tosnobile in Rats. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2018, 2018.

- McLean, J. B.; Moylan, J. S.; Andrade, F. H., Mitochondria dysfunction in lung cancer-induced muscle wasting in C2C12 myotubes. Frontiers in physiology 2014, 5, 503.

- Castro, B.; Kuang, S. J. B.-p., Evaluation of muscle performance in mice by treadmill exhaustion test and whole-limb grip strength assay. 2017, 7, (8), e2237-e2237.

- Ballarò, R.; Costelli, P.; Penna, F., Animal models for cancer cachexia. Current opinion in supportive and palliative care 2016, 10, (4), 281-287.

- Cadot, B.; Gache, V.; Gomes, E. R. J. N., Moving and positioning the nucleus in skeletal muscle–one step at a time. 2015, 6, (5), 373-381.

- Oliff, A.; Defeo-Jones, D.; Boyer, M.; Martinez, D.; Kiefer, D.; Vuocolo, G.; Wolfe, A.; Socher, S. H. J. C., Tumors secreting human TNF/cachectin induce cachexia in mice. 1987, 50, (4), 555-563.

- Rupert, J. E.; Narasimhan, A.; Jengelley, D. H.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, J.; Au, E.; Silverman, L. M.; Sandusky, G.; Bonetto, A.; Cao, S. J. J. o. E. M., Tumor-derived IL-6 and trans-signaling among tumor, fat, and muscle mediate pancreatic cancer cachexia. 2021, 218, (6), e20190450.

- Wang, K.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Shui, W.; Wang, J.; Cao, P.; Wang, H.; You, R.; Zhang, Y., Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide attenuates type 2 diabetes mellitus via the regulation of PI3K/Akt-mediated glycogen synthesis and glucose metabolism. Journal of Functional Foods 2018, 40, 261-271.

- Yue, H.; Liu, Y.; Qu, H.; Ding, K., Structure analysis of a novel heteroxylan from the stem of Dendrobium officinale and anti-angiogenesis activities of its sulfated derivative. International journal of biological macromolecules 2017, 103, 533-542.

- Xing, Y.-M.; Chen, J.; Cui, J.-L.; Chen, X.-M.; Guo, S.-X., Antimicrobial activity and biodiversity of endophytic fungi in Dendrobium devonianum and Dendrobium thyrsiflorum from Vietman. Current microbiology 2011, 62, 1218-1224.

- Qiang, Z.; Ko, C.-H.; Siu, W.-S.; Kai-Kai, L.; Wong, C.-W.; Xiao-Qiang, H.; Liu, Y.; Bik-San Lau, C.; Jiang-Miao, H.; Leung, P.-C., Inhibitory effect of different Dendrobium species on LPS-induced inflammation in macrophages via suppression of MAPK pathways. Chinese journal of natural medicines 2018, 16, (7), 481-489.

- Liang, J.; Li, H.; Chen, J.; He, L.; Du, X.; Zhou, L.; Xiong, Q.; Lai, X.; Yang, Y.; Huang, S., Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides alleviate colon tumorigenesis via restoring intestinal barrier function and enhancing anti-tumor immune response. Pharmacological research 2019, 148, 104417.

- Huang, S.; Chen, F.; Cheng, H.; Huang, G., Modification and application of polysaccharide from traditional Chinese medicine such as Dendrobium officinale. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 157, 385-393.

- Cui, S.; Li, L.; Yu, R. T.; Downes, M.; Evans, R. M.; Hulin, J.-A.; Makarenkova, H. P.; Meech, R., β-Catenin is essential for differentiation of primary myoblasts via cooperation with MyoD and α-catenin. Development 2019, 146, (6), dev167080.

- Charoenrungruang, S.; Chanvorachote, P.; Sritularak, B.; Pongrakhananon, V., Gigantol, a bibenzyl from Dendrobium draconis, inhibits the migratory behavior of non-small cell lung cancer cells. Journal of Natural Products 2014, 77, (6), 1359-1366.

- Kuo, C.-T.; Hsu, M.-J.; Chen, B.-C.; Chen, C.-C.; Teng, C.-M.; Pan, S.-L.; Lin, C.-H., Denbinobin induces apoptosis in human lung adenocarcinoma cells via Akt inactivation, Bad activation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Toxicology Letters 2008, 177, (1), 48-58.

- Lee, Y. H.; Park, J. D.; Beak, N. I.; Kim, S. I.; Ahn, B. Z., In vitro and in vivo antitumoral phenanthrenes from the aerial parts of Dendrobium nobile. Planta Medica 1995, 61, (02), 178-180.

- Lu, T.-L.; Han, C.-K.; Chang, Y.-S.; Lu, T.-J.; Huang, H.-C.; Bao, B.-Y.; Wu, H.-Y.; Huang, C.-H.; Li, C.-Y.; Wu, T.-S., Denbinobin, a phenanthrene from Dendrobium nobile, impairs prostate cancer migration by inhibiting Rac1 activity. The American journal of Chinese medicine 2014, 42, (06), 1539-1554.

- Yang, K.-C.; Uen, Y.-H.; Suk, F.-M.; Liang, Y.-C.; Wang, Y.-J.; Ho, Y.-S.; Li, I.-H.; Lin, S.-Y., Molecular mechanisms of denbinobin-induced anti-tumorigenesis effect in colon cancer cells. World Journal of Gastroenterology: WJG 2005, 11, (20), 3040.

- Huang, Y.-P.; He, T.-B.; Cuan, X.-D.; Wang, X.-J.; Hu, J.-M.; Sheng, J., 1, 4-β-d-Glucomannan from Dendrobium officinale Activates NF-к B via TLR4 to Regulate the Immune Response. Molecules 2018, 23, (10), 2658.

- Hwang, J. S.; Lee, S. A.; Hong, S. S.; Han, X. H.; Lee, C.; Kang, S. J.; Lee, D.; Kim, Y.; Hong, J. T.; Lee, M. K., Phenanthrenes from Dendrobium nobile and their inhibition of the LPS-induced production of nitric oxide in macrophage RAW 264.7 cells. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2010, 20, (12), 3785-3787.

- Brown, J. L.; Lawrence, M. M.; Ahn, B.; Kneis, P.; Piekarz, K. M.; Qaisar, R.; Ranjit, R.; Bian, J.; Pharaoh, G.; Brown, C. J. J. o. C., Sarcopenia; Muscle, Cancer cachexia in a mouse model of oxidative stress. 2020, 11, (6), 1688-1704.

- Khal, J.; Wyke, S.; Russell, S. T.; Hine, A. V.; Tisdale, M. J. J. B. j. o. c., Expression of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and muscle loss in experimental cancer cachexia. 2005, 93, (7), 774-780.

- Roberts, B.; Frye, G.; Ahn, B.; Ferreira, L.; Judge, A. J. B.; communications, b. r., Cancer cachexia decreases specific force and accelerates fatigue in limb muscle. 2013, 435, (3), 488-492.

- Otis, J. S.; Lees, S. J.; Williams, J. H. J. B. c., Functional overload attenuates plantaris atrophy in tumor-bearing rats. 2007, 7, (1), 1-9.

- Levolger, S.; van den Engel, S.; Ambagtsheer, G.; IJzermans, J. N.; de Bruin, R. W. J. N.; Aging, H., Quercetin supplementation attenuates muscle wasting in cancer-associated cachexia in mice. 2021, 6, (1), 35-47.

- Al-Majid, S.; McCarthy, D. O. J. B. r. f. n., Cancer-induced fatigue and skeletal muscle wasting: the role of exercise. 2001, 2, (3), 186-197.

- Zhang, Y.; Han, X.; Ouyang, B.; Wu, Z.; Yu, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, G.; Ji, X. J. E.-B. C.; Medicine, A., Chinese herbal medicine Baoyuan Jiedu Decoction inhibited muscle atrophy of cancer cachexia through Atrogin-l and MuRF-1. 2017, 2017.

- Bonetto, A.; Aydogdu, T.; Jin, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhan, R.; Puzis, L.; Koniaris, L. G.; Zimmers, T. A. J. A. J. o. P.-E.; Metabolism, JAK/STAT3 pathway inhibition blocks skeletal muscle wasting downstream of IL-6 and in experimental cancer cachexia. 2012, 303, (3), E410-E421.

- Webster, J. M.; Kempen, L. J.; Hardy, R. S.; Langen, R. C. J. F. i. p., Inflammation and skeletal muscle wasting during cachexia. 2020, 11, 597675.

- Steyn, P. J.; Dzobo, K.; Smith, R. I.; Myburgh, K. H. J. I. j. o. m. s., Interleukin-6 induces myogenic differentiation via JAK2-STAT3 signaling in mouse C2C12 myoblast cell line and primary human myoblasts. 2019, 20, (21), 5273.

- Ono, Y.; Saito, M.; Sakamoto, K.; Maejima, Y.; Misaka, S.; Shimomura, K.; Nakanishi, N.; Inoue, S.; Kotani, J. J. F. i. P., C188-9, a specific inhibitor of STAT3 signaling, prevents thermal burn-induced skeletal muscle wasting in mice. 2022, 13, 1031906.

- Ono, Y.; Maejima, Y.; Saito, M.; Sakamoto, K.; Horita, S.; Shimomura, K.; Inoue, S.; Kotani, J. J. S. r., TAK-242, a specific inhibitor of Toll-like receptor 4 signalling, prevents endotoxemia-induced skeletal muscle wasting in mice. 2020, 10, (1), 694.

- Ono, Y.; Sakamoto, K. J. P. o., Lipopolysaccharide inhibits myogenic differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts through the Toll-like receptor 4-nuclear factor-κB signaling pathway and myoblast-derived tumor necrosis factor-α. 2017, 12, (7), e0182040.

- Chae, S. A.; Kim, H.-S.; Lee, J. H.; Yun, D. H.; Chon, J.; Yoo, M. C.; Yun, Y.; Yoo, S. D.; Kim, D. H.; Lee, S. A. J. I. J. o. E. R.; Health, P., Impact of vitamin B12 insufficiency on sarcopenia in community-dwelling older Korean adults. 2021, 18, (23), 12433.

- Takahashi, F.; Hashimoto, Y.; Kaji, A.; Sakai, R.; Kawate, Y.; Okamura, T.; Kondo, Y.; Fukuda, T.; Kitagawa, N.; Okada, H. J. N., Vitamin intake and loss of muscle mass in older people with type 2 diabetes: a prospective study of the KAMOGAWA-DM cohort. 2021, 13, (7), 2335.

- Komaru, T.; Yanaka, N.; Kumrungsee, T. J. N., Satellite Cells Exhibit Decreased Numbers and Impaired Functions on Single Myofibers Isolated from Vitamin B6-Deficient Mice. 2021, 13, (12), 4531.

- Gomes, M. D.; Lecker, S. H.; Jagoe, R. T.; Navon, A.; Goldberg, A. L. J. P. o. t. N. A. o. S., Atrogin-1, a muscle-specific F-box protein highly expressed during muscle atrophy. 2001, 98, (25), 14440-14445.

- Donalies, M.; Cramer, M.; Ringwald, M.; Starzinski-Powitz, A., Expression of M-cadherin, a member of the cadherin multigene family, correlates with differentiation of skeletal muscle cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1991, 88, (18), 8024-8028.

- George-Weinstein, M.; Gerhart, J.; Blitz, J.; Simak, E.; Knudsen, K. A., N-cadherin promotes the commitment and differentiation of skeletal muscle precursor cells. Developmental biology 1997, 185, (1), 14-24.

- Kang, J.-S.; Feinleib, J. L.; Knox, S.; Ketteringham, M. A.; Krauss, R. S., Promyogenic members of the Ig and cadherin families associate to positively regulate differentiation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2003, 100, (7), 3989-3994.

- Charrasse, S.; Meriane, M.; Comunale, F.; Blangy, A.; Gauthier-Rouvière, C., N-cadherin–dependent cell–cell contact regulates Rho GTPases and β-catenin localization in mouse C2C12 myoblasts. The Journal of cell biology 2002, 158, (5), 953-965.

- Wróbel, E.; Brzóska, E.; Moraczewski, J., M-cadherin and β-catenin participate in differentiation of rat satellite cells. European journal of cell biology 2007, 86, (2), 99-109.

- Li, L.; Wazir, J.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H. J. G.; Diseases, A comprehensive review of animal models for cancer cachexia: Implications for translational research. 2024, 11, (6), 101080.

- Pototschnig, I.; Feiler, U.; Diwoky, C.; Vesely, P. W.; Rauchenwald, T.; Paar, M.; Bakiri, L.; Pajed, L.; Hofer, P.; Kashofer, K. J. J. o. c., sarcopenia; muscle, Interleukin-6 initiates muscle-and adipose tissue wasting in a novel C57BL/6 model of cancer-associated cachexia. 2023, 14, (1), 93-107.

- Mueller, T. C.; Bachmann, J.; Prokopchuk, O.; Friess, H.; Martignoni, M. E. J. B. c., Molecular pathways leading to loss of skeletal muscle mass in cancer cachexia–can findings from animal models be translated to humans? 2016, 16, 1-14.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).