Submitted:

02 October 2025

Posted:

04 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The Rose-ringed Parakeet (Psittacula krameri) is an invasive parrot increasingly established in European cities, including Athens, Greece, yet its diet and exposure to plant toxins in Mediterranean ecosystems remain poorly documented. We examined seasonal foraging patterns in Athens and assessed the toxicity of key food items using a brine shrimp lethality assay. Field observations recorded 601 feeding events across 10 plant species, and eight commonly consumed foods were tested with Artemia franciscana nauplii exposed to aqueous extracts for 48 hours to determine LC50 values and toxicity classes. Four foods—cypress seeds (Cupressus sempervirens), chinaberries (Melia azedarach), Canary Island dates (Phoenix canariensis), and olives (Olea europaea)—accounted for 82.9% of feeding events. Dietary diversity was highest in winter and summer, while foraging presence remained relatively stable, peaking in autumn. Toxicity assays identified chinaberries as most toxic and cypress seeds as least, indicating potential dietary risks. These findings show that P. krameri exhibits flexible, opportunistic foraging and tolerates plant compounds harmful to other vertebrates. Seasonal dietary shifts and ecological plasticity likely support its urban invasion success, highlighting the importance of understanding diet composition and potential exposure to plant toxins in urban parakeet populations.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Site

Foraging Observations

Toxicity Analysis

Sample Collection and Processing

Preparation of Aqueous Extracts

Brine Shrimp Hatching

Brine Shrimp Lethality Test (BSLT)

Statistical Analyses

3. Results

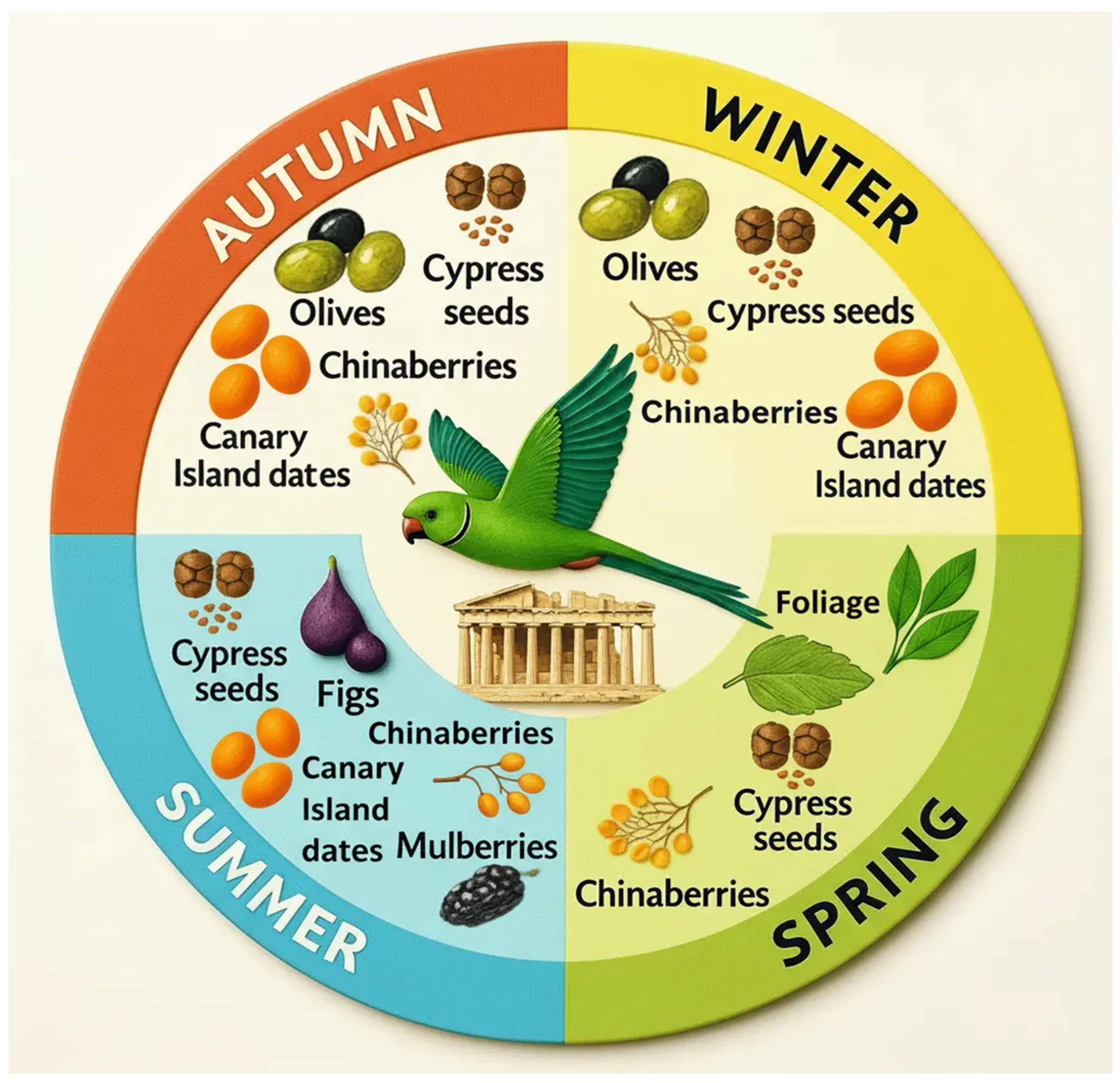

- Cypress seeds (Cupressus sempervirens) – Seeds were taken from green cones throughout the year. Birds broke unripe, non-woody cones with their beaks to access the seeds.

- Chinaberries (Melia azedarach) – Ripe fruits were consumed year-round. Birds held the fruit in their beaks and removed the peel with chewing movements before ingestion.

- Olives (Olea europaea) – Consumed mainly from October to February. Parakeets preferred mature olives, both green and dark-colored. Once an olive was grasped with the beak, they manipulated it with their feet before consuming parts of the flesh and eventually ingesting the pit (endocarp) (Figure 2).

- Canary Island dates (Phoenix canariensis) – Consumed from August to January at the mature stage, either eaten whole or partially, the latter in a manner similar to olives.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUA | Agricultural University of Athens |

| IMBBC-HCMR | Institute of Marine Biology, Biotechnology and Aquaculture, Hellenic Centre for Marine Research |

References

- Hulot, M. Papagalos o Athinaios [The Athenian Parrot]. LiFO, 2021. Available online: https://www.lifo.gr/tropos-zois/urban/papagalos-o-athinaios (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Butler, C.J. Population Biology of the Introduced Rose-ringed Parakeet Psittacula krameri in the UK. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Strubbe, D.; Matthysen, E. Establishment success of invasive ring-necked and monk parakeets in Europe. J. Biogeogr. 2009, 36, 2264–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ważna, A.; Ciepliński, M.; Ratajczak, W.; Bojarski, J.; Cichocki, J. Parrots in the wild in Polish cities. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, M.L.; Shiels, A.B. Monk and rose-ringed parakeets. In Ecology and Management of Terrestrial Vertebrate Invasive Species in the United States; Pitt, W.C., Beasley, J.C., Witmer, G.W., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 333–357. [Google Scholar]

- Manchester, S.J.; Bullock, J.M. The impacts of non-native species on UK biodiversity and the effectiveness of control. J. Appl. Ecol. 2000, 37, 845–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreyer, M.R.; Bucher, E.H. Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus). In The Birds of North America, No. 322; Poole, A., Gill, F., Eds.; Birds of North America, Inc.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1998; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolov, B.; Kralj, J.; Legakis, A.; Saveljic, D.; Velevski, M. Review of the alien bird species recorded on the Balkan Peninsula. In First ESENIAS Report: State of the Art of Invasive Alien Species in South-Eastern Europe; Rat, M., Trichkova, T., Scalera, R., Tomov, R., Uludag, A., Eds.; ESENIAS: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2016; pp. 189–201. Available online: https://www.esenias.org/files/13_Esenias_report_2016_193-205_bird.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Wetmore, A. Observations on the Birds of Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Chile, No. 133; Smithsonian Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 1926; pp. i–iv, 1–448. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10088/10240 (accessed on 28 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Aramburú, R.M. Ecología alimentaria de la cotorra (Myiopsitta monachus monachus) en la provincia de Buenos Aires, Argentina (Aves: Psittacidae) [Feeding ecology of the Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus monachus) in Buenos Aires Province, Argentina (Aves: Psittacidae)]. Physis (B. Aires) Secc. C 1997, 53, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Aramburú, R.; Corbalán, V. Dieta de pichones de cotorra Myiopsitta monachus (Aves, Psittacidae) en una población silvestre [Diet of nestlings of the Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus) (Aves: Psittacidae) in a wild population]. Ornitol. Neotrop. 2000, 11, 241–245. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher, E.H.; Aramburú, R.M. Land-use changes and monk parakeet expansion in the Pampas grasslands of Argentina. J. Biogeogr. 2014, 41, 1160–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzinger, C.; Larner, C.; Heatley, J.J.; Bailey, C.A.; MacFarlane, R.D.; Bauer, J.E. Conversion of α-linolenic acid to long-chain omega-3 fatty acid derivatives and alterations of HDL density subfractions and plasma lipids with dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids in Monk parrots (Myiopsitta monachus). J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2014, 98, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soni, A.C. Food habit and morphometrics of the roseringed parakeet Psittacula krameri Scopoli. M.Sc. Thesis, Gujarat Agricultural University, Anand, India, 1991. Available online: http://krishikosh.egranth.ac.in/handle/1/5810049006 (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Koutsos, E.A.; Matson, K.D.; Klasing, K.C. Nutrition of Birds in the Order Psittaciformes: A Review. J. Avian Med. Surg. 2001, 15, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiels, A.B.; Bukoski, W.P.; Siers, S.R. Diets of Kauai’s invasive rose-ringed parakeet (Psittacula krameri): evidence of seed predation and dispersal in a human-altered landscape. Biol. Invasions 2018, 20, 1449–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flory, A. Psittacula krameri (rose-ringed parakeet). Animal Diversity Web, University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. 2019. Available online: https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Psittacula_krameri/ (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Shivambu, T.C.; Shivambu, N.; Downs, C.T. Aspects of the feeding ecology of introduced Rose-ringed Parakeets Psittacula krameri in the urban landscape mosaic of Durban, KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. J. Ornithol. 2021, 162, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Khan, H.A.; Javed, M. An estimation of Rose-ringed Parakeet (Psittacula krameri) depredations on citrus, guava and mango in orchard fruit farm. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2012, 14, 149–152. [Google Scholar]

- Fraticelli, F. The Rose-ringed Parakeet Psittacula krameri in an urban park: Demographic trend, interspecific relationships and feeding preferences (Rome, central Italy). Avocetta 2014, 38, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Thabethe, V.; Wilson, A.L.; Hart, L.A.; Downs, C.T. Ingestion by an invasive parakeet species reduces germination success of invasive alien plants relative to ingestion by indigenous turaco species in South Africa. Biol. Invasions 2015, 17, 3029–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, I.M.; Symes, C.T. Invasion of Psittacula krameri in Gauteng, South Africa: are other birds impacted? Biodivers. Conserv. 2019, 28, 3633–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhaecke, P.; Persoone, G.; Claus, C.; Sorgeloos, P. Proposal for a short-term toxicity test with Artemia nauplii. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 1981, 5, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, M.; Russo, R.; Thurston, R. Trimmed Spearman-Karber method for estimating median lethal concentrations in toxicity bioassays; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, 1977; Available online: http://cfpub.epa.gov/si/si_public_comments.cfm?dirEntryId=43308 (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Meyer, B.N.; Ferrigni, N.R.; Putnam, J.E.; Jacobsen, L.B.; Nichols, D.E.; McLaughlin, J.L. Brine shrimp: A convenient general bioassay for active plant constituents. Planta Med. 1982, 45, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosselin, R.E.; Smith, R.P.; Hodge, H.C.; Braddock, J. Clinical toxicology of commercial products, 5th ed.; Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hamidi, M.; Jovanova, B.; Kadifkova Panovska, T. Toxicological evaluation of the plant products using Brine Shrimp (Artemia salina L.) model. Maced. Pharm. Bull. 2014, 60, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juniper, T.; Parr, M. Parrots: A Guide to the Parrots of the World; Pica Press: Robertsbridge, UK, 1998; pp. 1–584. [Google Scholar]

- Strubbe, D.; Matthysen, E. Invasive ring-necked parakeets Psittacula krameri in Belgium: Habitat selection and impact on native birds. Ecography 2007, 30, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Ripley, S.D. Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan: Together with Those of Bangladesh, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan and Sri Lanka, Vol. 7, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1996; pp. 1–236. [Google Scholar]

- Eason, P.; Victor, R.; Eriksen, J.; Kwarteng, A. Status of the exotic ring-necked parakeet, Psittacula krameri, in Oman (Aves: Psittacidae). Zool. Middle East 2009, 47, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Khan, H.A.; Javed, M.; Ur-Rehman, K. Roost composition and damage assessment of rose-ringed parakeet (Psittacula krameri) on maize and sunflower in agro-ecosystem of Central Punjab, Pakistan. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2011, 13, 731–736. [Google Scholar]

- Clergeau, P.; Vergnes, A. Bird feeders may sustain feral rose-ringed parakeets Psittacula krameri in temperate Europe. Wildl. Biol. 2011, 17, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Symes, C.T. Founder populations and the current status of exotic parrots in South Africa. Ostrich 2014, 85, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tella, J.L.; Baños-Villalba, A.; Hernández-Brito, D.; Rojas, A.; Pacífico, E.; Díaz-Luque, J.A.; Carrete, M.; Blanco, G.; Hiraldo, F. Parrots as overlooked seed dispersers. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2015, 13, 338–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borray-Escalante, N.A.; Mazzoni, D.; Ortega-Segalerva, A.; Arroyo, L.; Morera-Pujol, V.; González-Solís, J.; Senar, J.C. Diet assessments as a tool to control invasive species: Comparison between Monk and Rose-ringed parakeets with stable isotopes. J. Urban Ecol. 2020, 6, juaa005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strubbe, D. Psittacula krameri (rose-ringed parakeet). CABI Compendium. 2022. [CrossRef]

- McNeely, J.A.; Mooney, H.A.; Neville, L.E.; Schei, P.; Waage, J.K. (Eds.) A global strategy on invasive alien species; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK, 2001; 50 pp., ISBN 2-8317-0609-2. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M.A. Biotic globalization: Does competition from introduced species threaten biodiversity? BioScience 2003, 53, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevitch, J.; Padilla, D.K. Are invasions a major cause of extinctions? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2004, 19, 470–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Zuniga, R.; Morrison, D. Update on the environmental and economic costs associated with alien-invasive species in the United States. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 52, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caughley, G.H.; Gunn, A. Conservation biology in theory and practice; Blackwell Science: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996; 459 pp., ISBN 0865424314. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, S. Rare plants protect Cape’s water supplies. New Sci. 1995, 145, 8. Available online: https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg14519633-200-rare-plants-protect-capes-water-supplies/ (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Mukherjee, A.; Borad, C.K.; Parasharya, B.M. Damage of rose-ringed parakeet, Psittacula krameri borealis, to safflower, Carthamus tinctorius L. Pavo 2000, 38, 15–18. Pavo 2000, 38, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kale, M.A.; Dudhe, N.; Kasambe, R.; Bhattacharya, P. Crop depredation by birds in Deccan Plateau, India. Int. J. Biodivers. 2014, 947683, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.R. Studies on damage to sorghum by the rose-ringed parakeet, Psittacula krameri (Scopoli), at Rajendranagar, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh. Pavo 1998, 36, 79–80. [Google Scholar]

- Klug, P.E.; Bukoski, W.P.; Shiels, A.B.; Kluever, B.M.; Siers, S.R. Rose-ringed parakeets. Wildl. Damage Manage. Tech. Ser. 2019, 23, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Shiels, A.; Kalodimos, N. Biology and impacts of Pacific island invasive species. 15. Psittacula krameri, the rose-ringed parakeet (Psittaciformes: Psittacidae). Pac. Sci. 2019, 73, 421–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, H.L.; Pringle, H.E.; Marshall, H.H.; Owens, I.P.; Lord, A.M. Experimental evidence of impacts of an invasive parakeet on foraging behavior of native birds. Behav. Ecol. 2014, 25, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menchetti, M.; Mori, E. Worldwide impact of alien parrots (Aves: Psittaciformes) on native biodiversity and environment: A review. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 2014, 26, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaefstathiou, E.; Agapiou, A.; Giannopoulos, S.; Kokkinofta, R. Nutritional characterization of carobs and traditional carob products. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 2151–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailaja, R.; Kotak, V.C.; Sharp, P.J.; Schmedemann, R.; Haase, E. Environmental, dietary, and hormonal factors in the regulation of seasonal breeding in free-living female Indian rose-ringed parakeets (Psittacula krameri). Horm. Behav. 1988, 22, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabethe, V.; Thompson, L.J.; Hart, L.A.; Brown, M.; Downs, C.T. Seasonal effects on the thermoregulation of invasive rose-ringed parakeets (Psittacula krameri). J. Therm. Biol. 2013, 38, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Salguero, R.; Camarero, J.J.; Carrer, M.; Gutiérrez, E.; Alla, A.Q.; Andreu-Hayles, L.; Hevia, A.; Koutavas, A.; Martínez-Sancho, E.; Nola, P.; Papadopoulos, A.; Pasho, E.; Toromani, E.; Carreira, J.A.; Linares, J.C. Climate extremes and predicted warming threaten Mediterranean Holocene fir forests refugia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E10142–E10150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, W.R.; Schutzman, H.; Lee, B.R.; Knight, M.W. Chinaberry poisoning in two dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1997, 210, 1638–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.G. Poisoning in ostriches following ingestion of toxic plants—field observations. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2007, 39, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Yasinzai, M.; Mehmood, Z.; Khan, J.; Khalil, A.; Saqib, S.; Rahman, W. Comparative study of green fruit extract of Melia azedarach Linn. with its ripe fruit extract for antileishmanial, larvicidal, antioxidant and cytotoxic activity. Am. J. Phytomed. Clin. Ther. 2014, 2, 442–454. [Google Scholar]

- Rjeibi, I.; Ben Saad, A.; Ncib, S.; Souid, S.; Allagui, M.S.; Hfaiedh, N. Brachychiton populneus as a novel source of bioactive ingredients with therapeutic effects: antioxidant, enzyme inhibitory, anti-inflammatory properties and LC-ESI-MS profile. Inflammopharmacology 2020, 28, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisele, T.A.; Loveland, P.M.; Kruk, D.L.; Meyers, T.R.; Sinnhuber, R.O.; Nixon, J.E. Effect of cyclopropenoid fatty acids on the hepatic microsomal mixed-function-oxidase system and aflatoxin metabolism in rabbits. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1982, 20, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrianaivo-Rafehivola, A.A.; Gaydou, E.M.; Rakotovao, L.H. Revue sur les effets biologiques des acides gras cyclopropéniques. Oléagineux Corps Gras Lipides 1994, 1, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, M.A.; Abou Zeid, A.H.; Hamed, M.A.; Kandeel, Z.; El-Rafie, H.M.; El-Akad, R.H. Metabolomic fingerprint classification of Brachychiton acerifolius organs via UPLC-qTOF-PDA-MS analysis and chemometrics. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 29, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokbli, S.; Sbihi, H.; Nehdi, I.; Romdhani-Younes, M.; Tan, C.; Al-Resayes, S. A comparative study of Brachychiton populneus seed and seed-fiber oils in Tunisia. Waste Biomass Valor. 2018, 9, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilardi, J.D.; Toft, C.A. Parrots eat nutritious foods despite toxins. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janzen, D.H.; Fellows, L.E.; Waterman, P.G. What Protects Lonchocarpus (Leguminosae) Seeds in a Costa Rican Dry Forest? Biotropica 1990, 22, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acedo, V. Ecology of the Yellow-Naped Amazon in Guatemala. AFA Watchbird 1992, 18, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Norconk, M.A.; Grafton, B.W.; Conklin-Brittain, N.L. Seed Dispersal by Neotropical Seed Predators. Am. J. Primatol. 1998, 45, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terborgh, J. Maintenance of Diversity in Tropical Forests. Biotropica 1992, 24, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilardi, J.D.; Duffey, S.S.; Munn, C.A.; et al. Biochemical Functions of Geophagy in Parrots: Detoxification of Dietary Toxins and Cytoprotective Effects. J. Chem. Ecol. 1999, 25, 897–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species Name | Common Name of the Tree |

Item | Common Name of the Item |

Native Status in Greece |

| Brachychiton populneus | Kurrajong Tree | Pod seeds | Kurrajong seeds | Non native – locally naturalized (rare) |

| Cupressus sempervirens | Mediterranean Cypress | Cone seeds | Cypress seeds | Native |

| Ficus carica | Fig Tree | Fleshy fruits | Figs | Native |

| Ligustrum japonicum | Japanese Privet | Fleshy fruits | Privet berries | Non native – locally naturalized |

| Laurus nobilis | Bay Laurel | Fleshy fruits | Bay laurel berries | Native |

| Melia azedarach | Chinaberry tree | Fleshy fruits | Chinaberries | Non native – occasional naturalization (uncertain extent) |

| Morus spp. | Mulberry Tree | Fleshy fruits | Mulberries | Long naturalized (non native) |

| Olea europaea | Olive Tree | Fleshy fruits | Olives | Native |

| Phoenix canariensis | Canary Island Date Palm | Fleshy fruits | Canary Island dates | Non native – not naturalized* |

| Pistacia lentiscus | Mastic Tree | Fleshy fruits | Mastic berries | Native |

| Species Name | Item | Feeding Observations (%) | |||

|

Autumn n=185 (100%) |

Winter n=139 (100%) |

Spring n=158 (100%) |

Summer n=119 (100%) |

||

| Brachychiton populneus | Pod seeds | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (6.7%) |

| Cupressus sempervirens | Cone seeds | 31 (16.8%) | 27 (19.4%) | 55 (34.8 %) | 35 (29.4%) |

| Ficus carica | Fleshy fruits | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (15.1%) |

| Ligustrum japonicum | Fleshy fruits | 0 (0%) | 4 (2.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Foliage | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 15 (9.5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Laurus nobilis | Fleshy fruits | 0 (0%) | 10 (7.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Melia azedarach | Fleshy fruits | 48 (25.9%) | 33 (23.7%) | 64 (40.5%) | 9 (7.6%) |

| Foliage | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (6.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Morus spp. | Fleshy fruits | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 16 (13.4%) |

| Foliage | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (6.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Olea europaea | Fleshy fruits | 55 (29.7%) | 48 (34.5 %) | 4 (2.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Phoenix canariensis | Fleshy fruits | 45 (24.3%) | 16 (11.5 %) | 0 (0%) | 28 (23.5%) |

| Pistacia lentiscus | Fleshy fruits | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.7%) |

| Shannon Index (H’) | 1.480 | 1.603 | 1.399 | 1.720 | |

| Season | Birds observed on trees | Census walks | Foraging Presence$ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autumn | 230 | 33 | 6.97 |

| Winter | 179 | 30 | 5.97 |

| Spring | 188 | 29 | 6.48 |

| Summer | 141 | 21 | 6.71 |

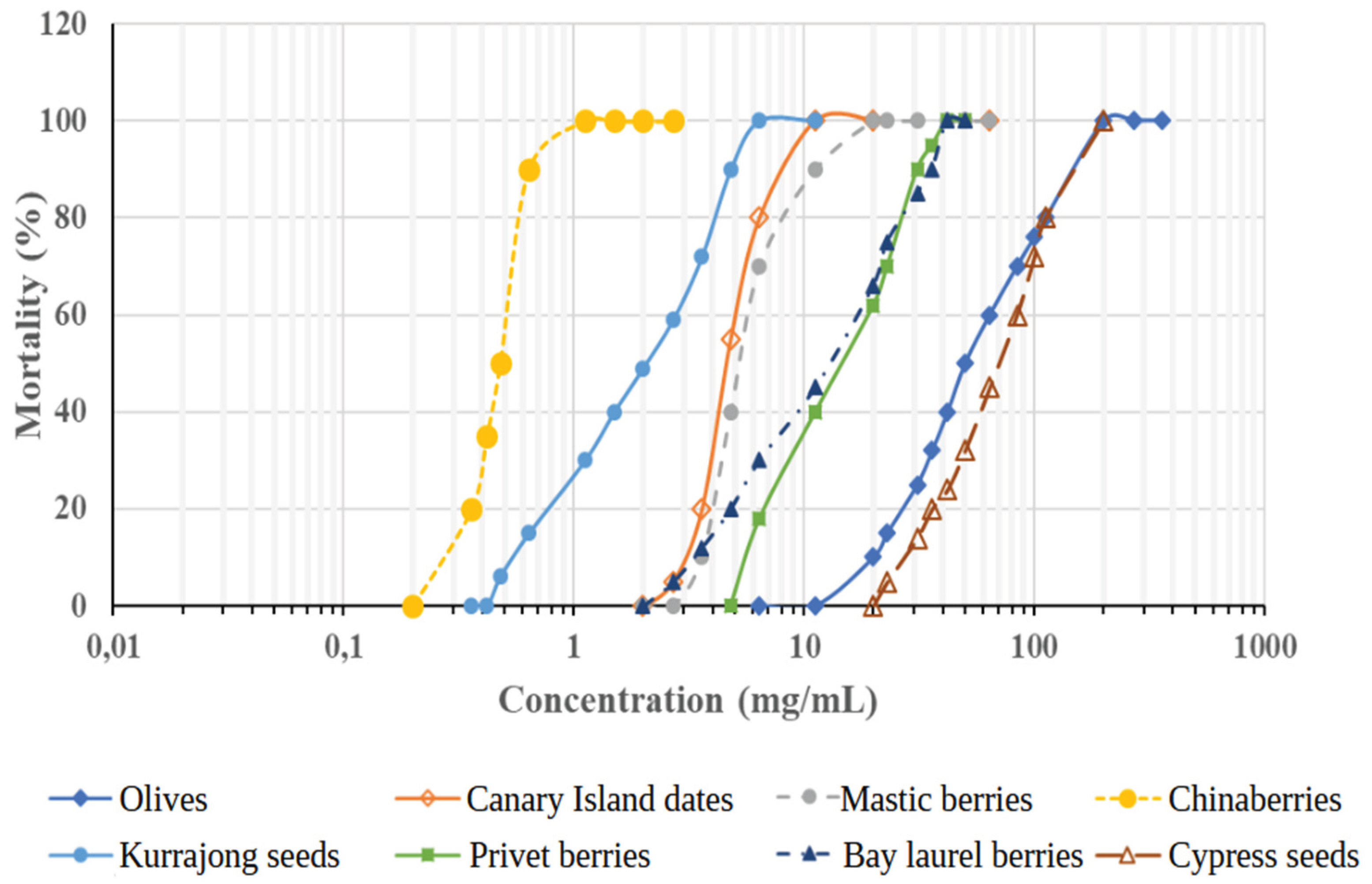

| Species Name | Extract Sample | 48h-LC50 (mg/mL) ± SD | Range (98% Conf. Int.) |

Toxicity Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brachychiton populneus | Kurrajong seeds | 2.14 ± 0.01 | 1.36 – 3.34 | Moderately toxic |

| Cupressus sempervirens | Cypress seeds | 84.58 ± 3.80 | 66.48 – 104.46 | Non-toxic |

| Laurus nobilis | Bay laurel berries | 11.64 ± 0.11 | 7.92 – 17.14 | Slightly toxic |

| Ligustrum japonicum | Privet berries | 14.44 ± 0.10 | 10.96 – 19.04 | Slightly toxic |

| Melia azedarach | Chinaberries | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 0.38 – 0.56 | Moderately to Very toxic |

| Olea europaea | Olives | 51.70 ± 2.24 | 38.46 – 69.50 | Non-toxic |

| Phoenix canariensis | Canary Island dates | 4.84 ± 0.22 | 3.98 – 5.90 | Moderately toxic |

| Pistacia lentiscus | Mastic berries | 5.68 ± 0.02 | 4.54 – 7.12 | Slightly to Moderately toxic |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).