1. Introduction

Wild animals exhibit variations in their behavior and activity levels throughout the day, and round the year [

1,

2]. It is believed that individual fitness and survival are directly impacted by the patterns of temporal activity fluctuations–revealing significant aspects of their ecological niche [

3]. In conservation biology, studies on animal behavior are crucial–especially for documenting the activity patterns of wild animals in response to several biotic and abiotic factors [

4]. Extreme and hostile habitats such as sandy deserts, tundra’s and high altitude mountains have a significant impact on a species' circadian rhythms–including movements, resting, reproductive cycles, and foraging. These harsh surroundings compel the species to explore the flexible and adaptive behaviors which are vital for survival [

5]. Therefore understanding the major variables that affect the activity patterns can help in finding answers to the questions regarding how organisms are able to survive, adapt, and persist in their surroundings [

6,

7].

Extremely high temperatures (up to 50.0°C), intense sun radiations, little precipitation, and tiny shady cover makes deserts the most austere of all the terrestrial habitats [

8]. For successful survival and propagation, animals must meet a variety of basic needs during the day, such as foraging along with additional necessities including seeking shelter, resting and social interactions etc. [

9]. However, the non-burrowing mammals residing hot arid environments such as deserts are constantly exposed to higher temperatures and face limited availability of vital resources–hindering and affecting their normal activity patterns [

10]. Consequently abnormal fluctuations in the activity patterns may aid to the threats for survival of animals inhabiting the hot and dry environments [

11,

12].

To cope with harsh climatic conditions, deserts ungulates have evolved through several behavioral adaptations [

13]. The primary strategy of desert antelopes to avoid heat stress is to change their daily activity patterns. Dorcas’s gazelles (

Gazella dorcas) in the Sahara, goitered gazelles (

Gazella subgutturosa) in the arid regions of the northern deserts of Central Asia, and springboks (

Antidorcas marsupialis) in the Kalahari Desert all exhibit similar behavior during the hot summer months, with two peaks of activity occurring in the early morning and late afternoon [

14,

15]. Likewise other species including springboks (

Antidorcas marsupialis), Kirk's dik-diks (

Madoqua kirkii), beira (

Dorcatragus megalotis) and gemsboks (

Oryx gazella) switch their activities from daylight to nocturnal in order to counter heat stress [

13,

16,

17,

18].

The Arabian Peninsula is the intersection of three biogeographic realms: Western Palearctic, Afro-tropical, and Indo-Malayan, and is home to a large array of wildlife species including 173 terrestrial mammal species [

19]. The fauna of the Arabian Peninsula is a combination of species with affinities to the Horn of Africa, Saharo-Sindian, Iranian-Central Asian, and Mediterranean elements, as well as endemic species from Arabia [

20]. Of these species, 11 are ungulates and Arabian sand gazelle (

Gazella marica) is one of them [

19].

Arabian sand gazelle, locally known as “Al-reem” is a relatively small antelope species, native to the Middle East–specifically the Arabian and Syrian Deserts. This species was once widely distributed in the aforementioned areas; however, the population has been drastically declined due to several factors–with poaching being a prominent cause [

21,

22,

23,

24]. The extermination of wild populations of Arabian sand gazelle apperently initiated soon after the Second World War, when the building of highways and the accessibility of four-wheel-drive cars opened up areas formerly inaccessible to man [

25]. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) red list, the estimated population size of

G. marica is 1750–2100 and is declared globally vulnerable with decreasing population trends [

26].

Several measures are taken to restore the species into the native habitats and to reinforce the existing small scattered wild populations of Arabian sand gazelle, including captive breeding and re-introduction [

25]. The practices mentioned above have mainly focused on the population monitoring, yet, there is a dearth of information on the behaviorof Arabian sand gazelle bred in captivity. It is believed that animals residing hot arid environments, probably cut back on their activities with higher temperatures [

27]. If this hold true, we presume that Arabian sand gazelle will be much more active in winter rather than in summer. Therefore, the current study was designed to investigate the seasonal activity patterns of the Arabian sand gazelle to know how they adjust their daily activities to the daily temperatures, to help support management of this threatened ungulate.

2. Materials and Methods

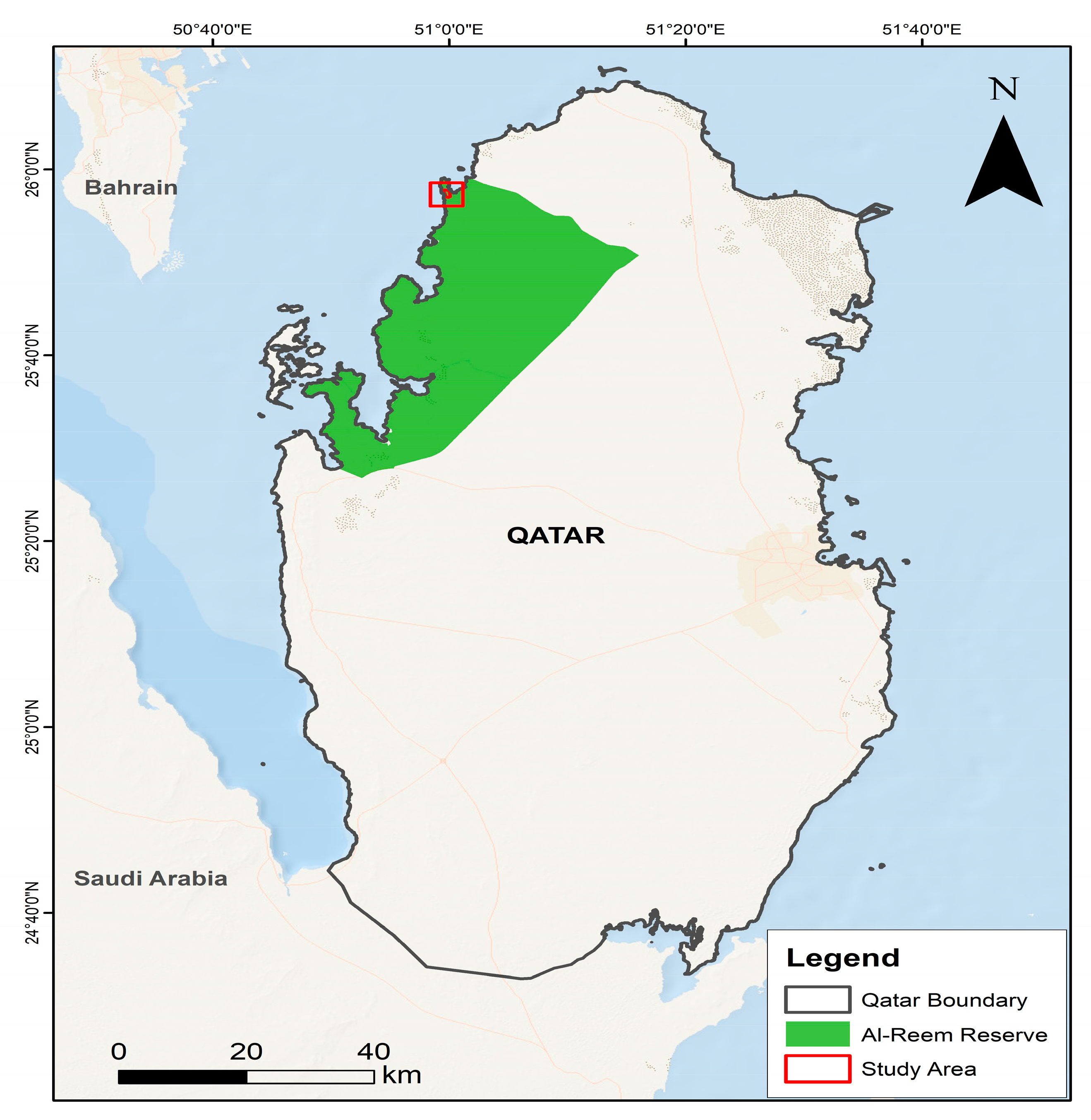

2.1. Study Area

The current study was carried out at Al-Reem Biosphere Reserve (Figure.1). This reserve is located in northwest Qatar (25°53.8’ N, 51°03.00’ E), encompassing an area of 1154 km

2 with elevation ranges between 0–60 m above sea level (asl). It was established as a protected area in 1994 and later on recognized as a biosphere reserve under UNSECO’s Man and Biosphere (MAB) program in 2007 [

28]. Topography of the reserves is characterized by unique gravel plains known as “hazm”, along with saline, swampy, and muddy depressions. Limestone formations are also major topographical features of the reserve. The average annual temperature is 29 °C and this number can hit 40 °C and beyond in summer, with an average annual rainfall of 70 mm. A total of 85 plant species have been reported from the reserve. Key ungulate species of the reserve are Arabian sand gazelle and Arabian Oryx (

Oryx leucoryx). [

29].

Figure 1.

Map showing location of study area.

Figure 1.

Map showing location of study area.

2.2. Study Animals

Our study animals were located in an outdoor enclosure encompassing an area of 3×3 km. This enclosure was a mixed specie exhibit, where Arabian sand gazelle (n = 360) shared the space with Arabian Oryx (n = 400). Our study animals were regularly fed with supplemental feed by the reserve rangers, including food pellets, fresh feed (green twigs, branches etc.) and alfalfa hay with ad-libitum supply of water. This reserve also harbors shelters in the form of scattered plantations and manmade shades.

2.3. Behavioral Observations

The current study was conducted in two phases i.e. summer (in between September-November, 2021) and winter (in between December 2021–January 2022). Data were collected for a total of 16 days (eight days in each season)–yielding a sampling effort of 1152 observations in 176 h. Following Estes (1991) we designed an ethogram to record activity patterns. We broadly classified the activity patterns in to five categories (

Table 1). We employed group scan sampling method as described by Martin et al [

30]. Based on the time interval method, each observation was recorded after every five minutes from 06:00–12:00 am and 13:00–17:00 pm. Observations were recorded by two observers. To reduce the observers presence impact on the behavior of animals, we tried to scan the groups from a distance of at least 100 m or more along with using a camouflage [

31]. Animals and groups were scanned and behaviors were recorded regardless of gender or age. The mean group size of the animals at the reserve was 16 ± 3. Different groups and solitary animals were taken in randomly considered. Air and soil temperatures were hourly recorded by using thermometer, and were assigned to all observations recorded during that hour.

2.4. Analytical Approach

To study the effect of season, time, air and soil temperatures on the Arabian sand gazelle activities, we used polynomial regression. The initial model contained all of the following factors. To keep only significant factors, we performed stepwise model selection based on the AIC [

32].

where β presents the regression coefficient while the subscript presents the index of respective explanatory variable, 2 etc. (Time)

2 + (Time)

3 presents the quadratic and cubic terms of time factor. The interaction terms (e.g., Season* Air temperature) presents the joint effect of these factors. These terms were included to capture potential nonlinear relationships in the data.

In order to differentiate between the variables used in the models β values were assigned where:

β1 represent Season, β2 represents Time, β3 represents Air Temperature and β4 Soil Temperature. Moreover, the β represent the straight variables used, single superscript shows the squared followed by additional subscript which represents the cubic effect. Superscripts are used to identify the parameters in relation to the straight variables used in analysis.

Each single behavioral category was treated as response; hence a separate model was fitted for behavioral category. For fitting the linear regression, we used function ‘lm’ in program R version 4.1.2 [

33].

3. Results

The final models, selected for each response variable, showed substantial improvements in fit. Corresponding reductions in AIC and improvements in log-likelihood values demonstrated the enhanced predictive power of the final models (

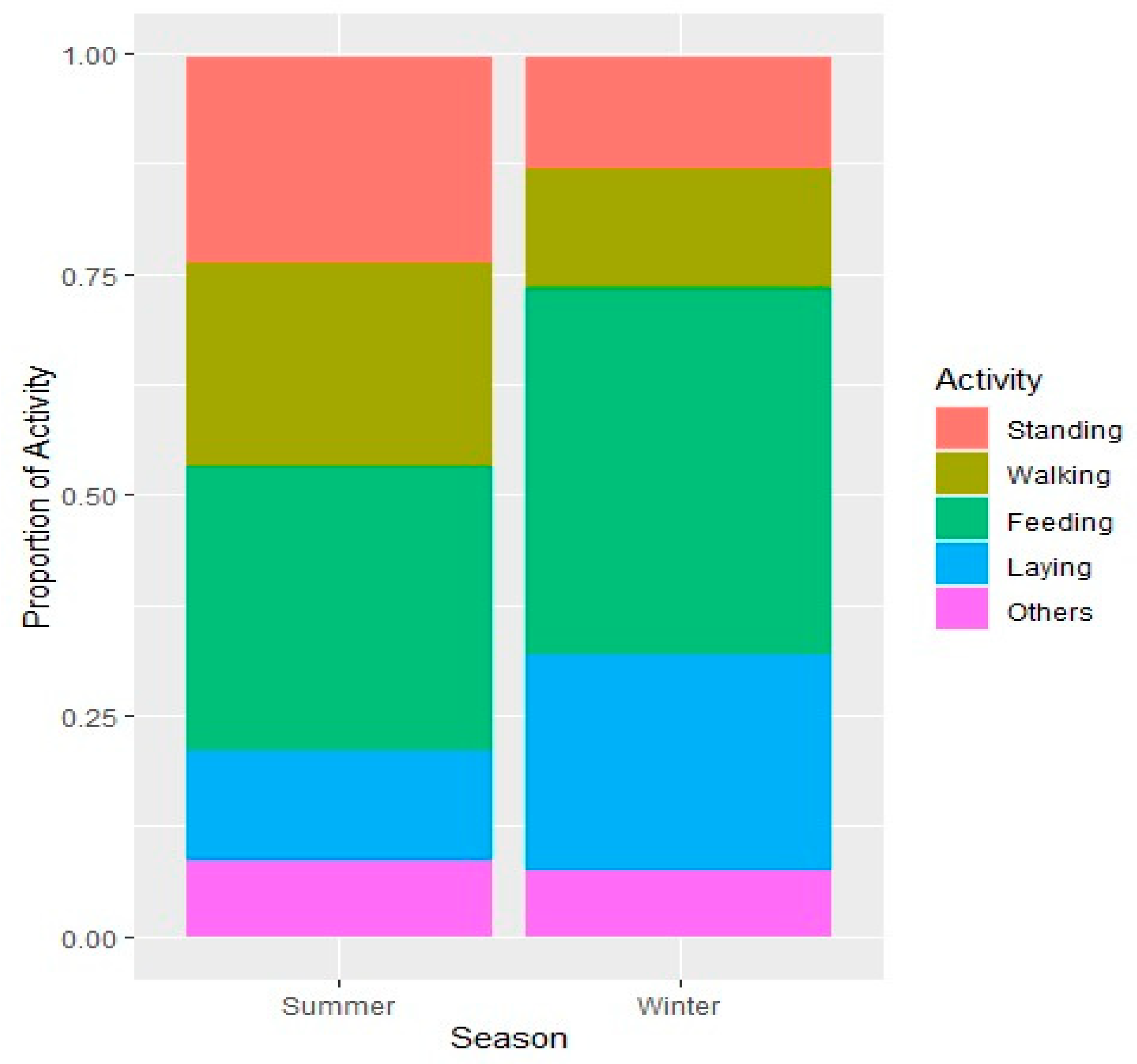

Table 2). Results obtained in the current study revealed that season has a profound effect on the time allocation for different activities (

Table 3). However, in all categories the time allocations remained consistent. It is pertinent to note that Arabian sand gazelle achieved this consistency by adjusting behaviors within each category during the two seasons. For instance, among active behaviors, feeding remained dominant in both seasons, however it got heightened from 32% to 42% in winter on expense of time allocated for walking. Likewise in summer the time allocated for standing was 26% and 13% for laying down; which got reversed to 12% and 24% respectively in winter (

Figure 2).

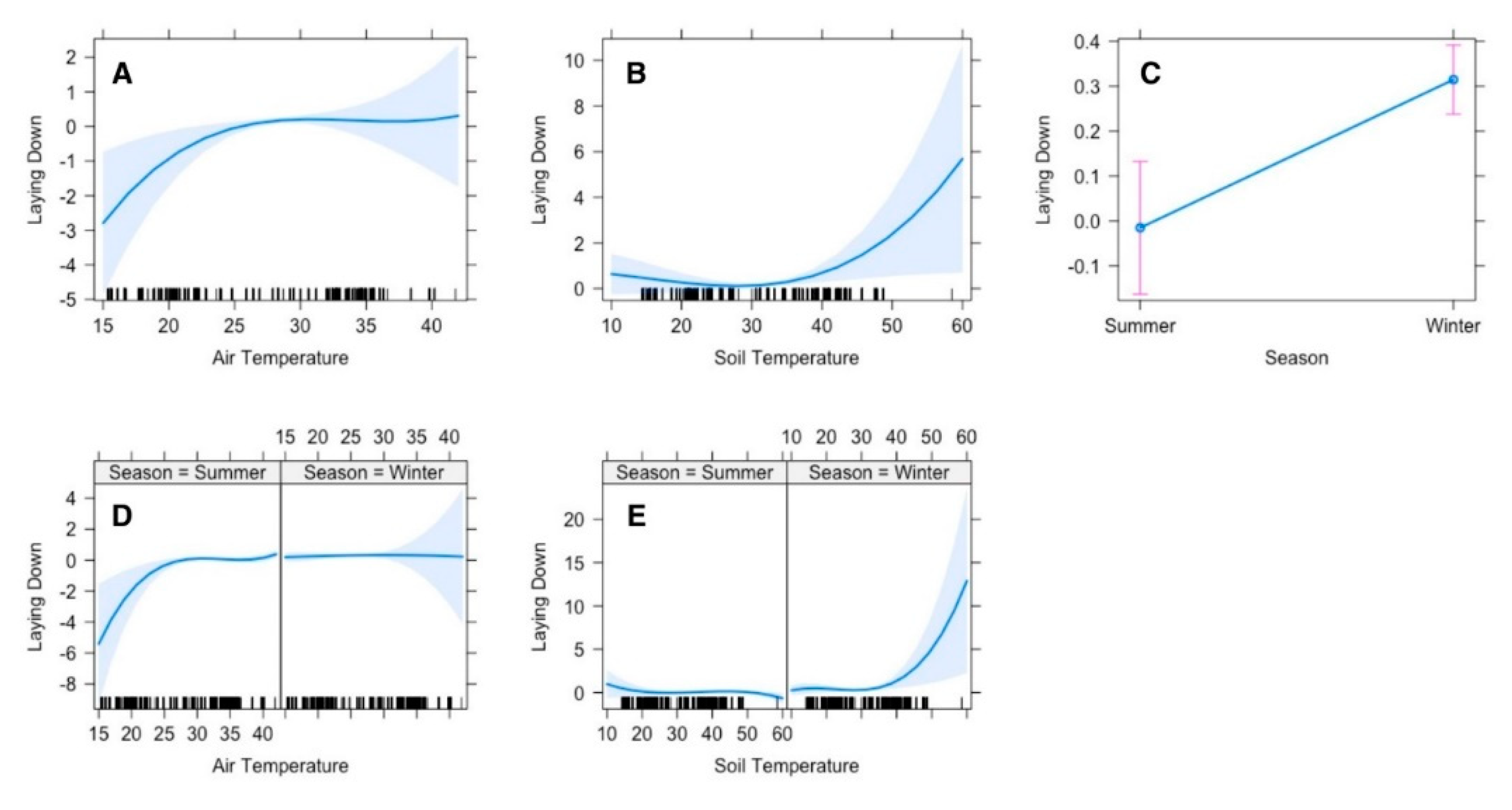

The top polynomial model suggested that the gazelle’s time allocation for laying down was significantly influenced by season, air and soil temperatures. The gazelle laid down less frequently at lower temperature (≤15 °C), however the duration of laying down increased gradually with increasing temperature until 25 °C, afterwards there was no noticeable change (

Figure 3A). Time allocation for laying down was also influenced by soil temperature as well. In winter when the soil temperature was comparatively low, and gazelles lay down less frequently, but when the temperature rises, they tend to lay down more frequently. However, in summer since the soil temperature was more often high and animals tend to lay down at any time of the day (

Figure 3E).

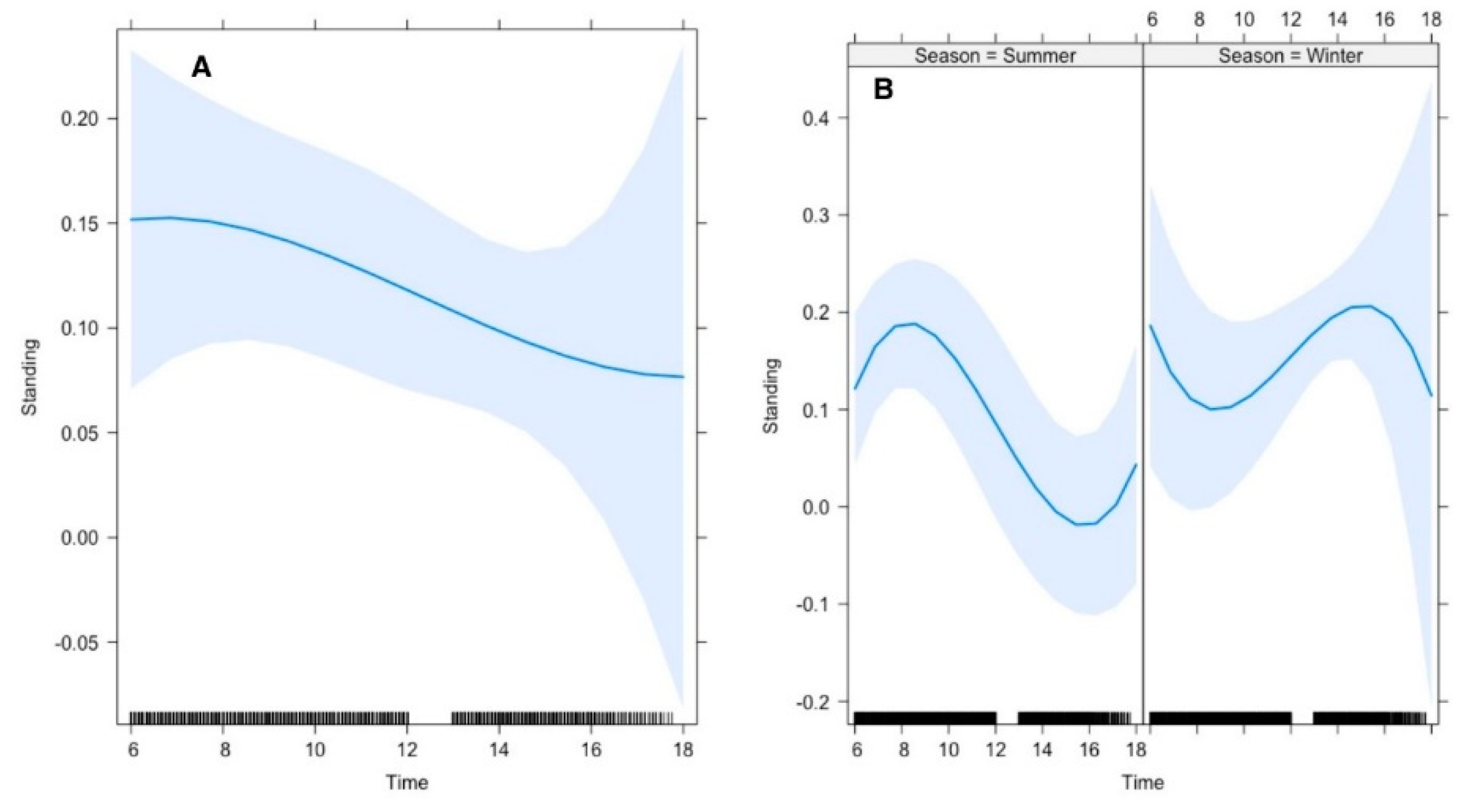

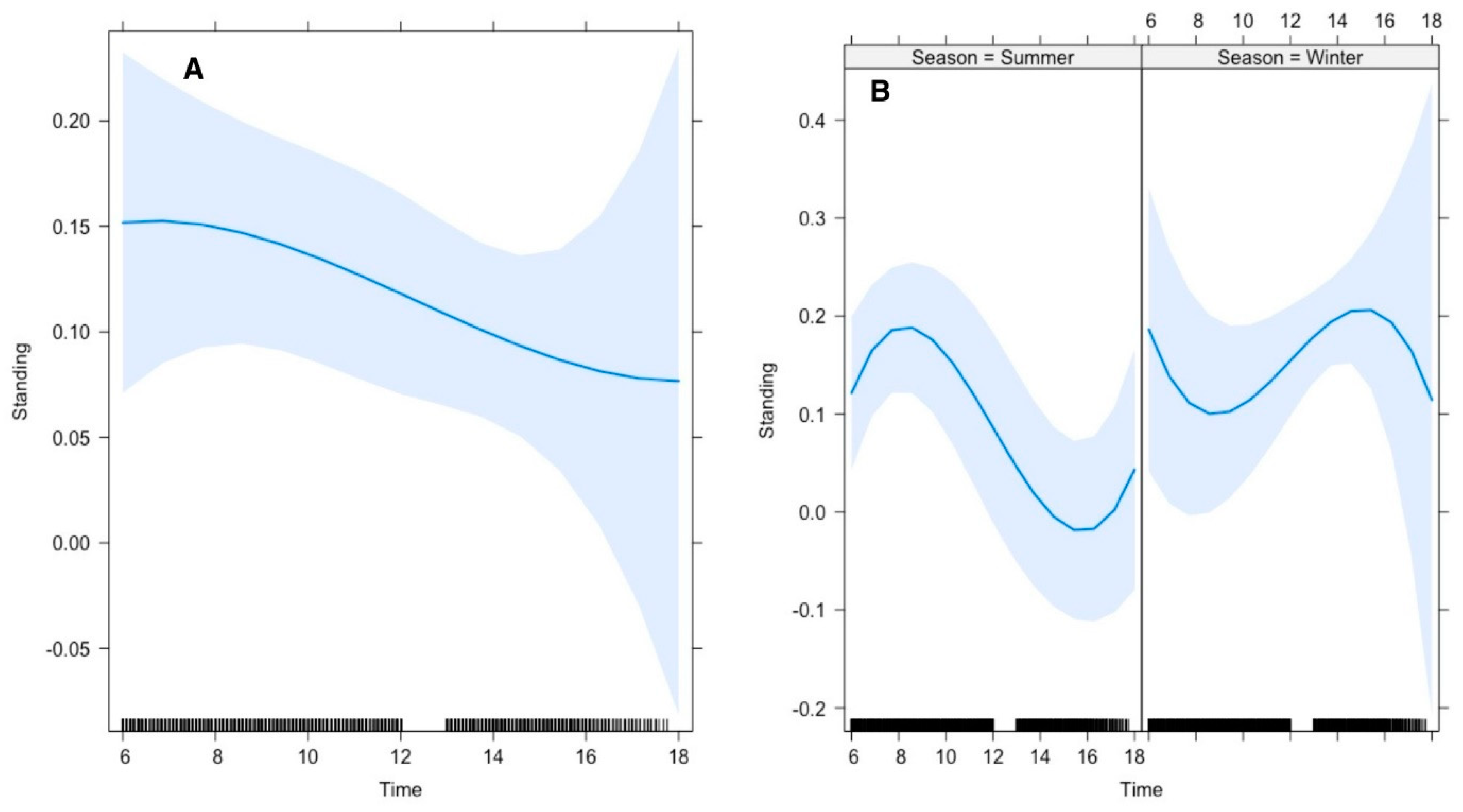

Our results further revealed that the average time gazelle spent on standing was 26% in summer and 12% in winter. The top polynomial model suggested that the gazelle’s time allocation for standing was significantly influenced by time of day. In summer, Arabian gazelle spent significantly higher time standing during morning than in afternoon, whereas this pattern was reversed in winter (

Figure 4).

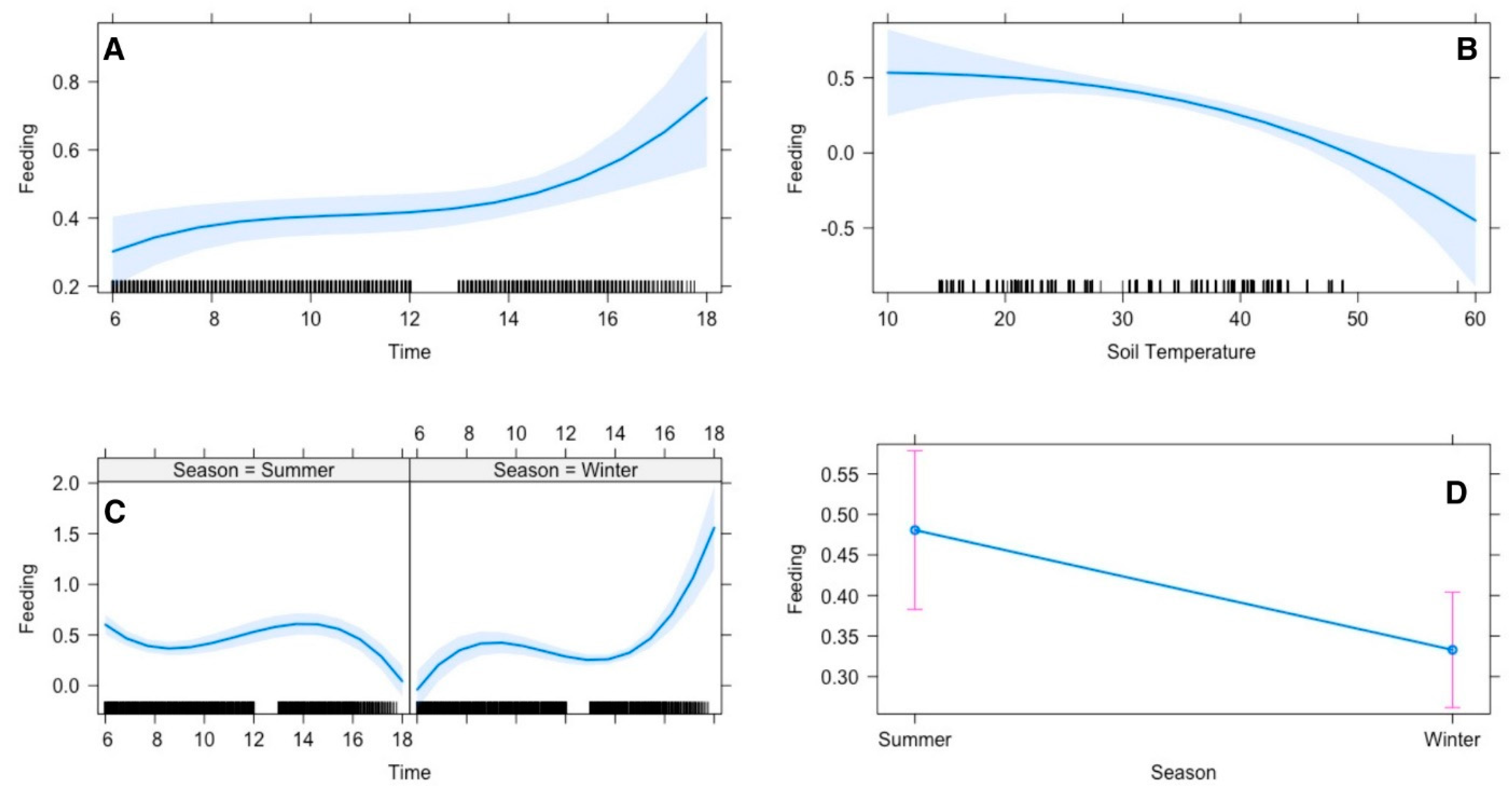

The average time Arabian gazelle spent on feeding was 42% and 32 % in summer and winter, respectively. The top polynomial model suggested that the gazelle’s time allocation for feeding was significantly influenced by season, time, and soil temperatures. Feeding activity was lowest in early morning (30%), there was minor increase until noon, and then a sharp increase was observed in late afternoon (after 16:00 pm). In evening (18:00 pm) gazelle utilized maximum time (80%) in feeding (

Figure 5A). This pattern is divergent among seasons, in evenings feeding activity declined in summer and increased in winter (

Figure 5C). If we compare seasons, the Arabian sand gazelle tend to eat more in summer than in winter by 15% (

Figure 5D). Moreover, when the soil temperature is low, the gazelle tend to eat more while when the temperature gets high, they tend to eat less (

Figure 5D).

The average time gazelle spent on walking was 22% in summer and 14% in winter, respectively. The top polynomial model suggested that the gazelle’s time allocation for walking was significantly influenced by time of the day only. The gazelles began their day by walking then it declined dramatically at 12:00 pm, but it started to increase again between 16:00–18:00 pm. However, this relationship curve was quadratic (

Figure 6). In summer, they walked more in the late afternoon, while in winter they tend to walk more in the early morning then it decreased every hour, till it reaches the lowest level in evening (

Figure 6).

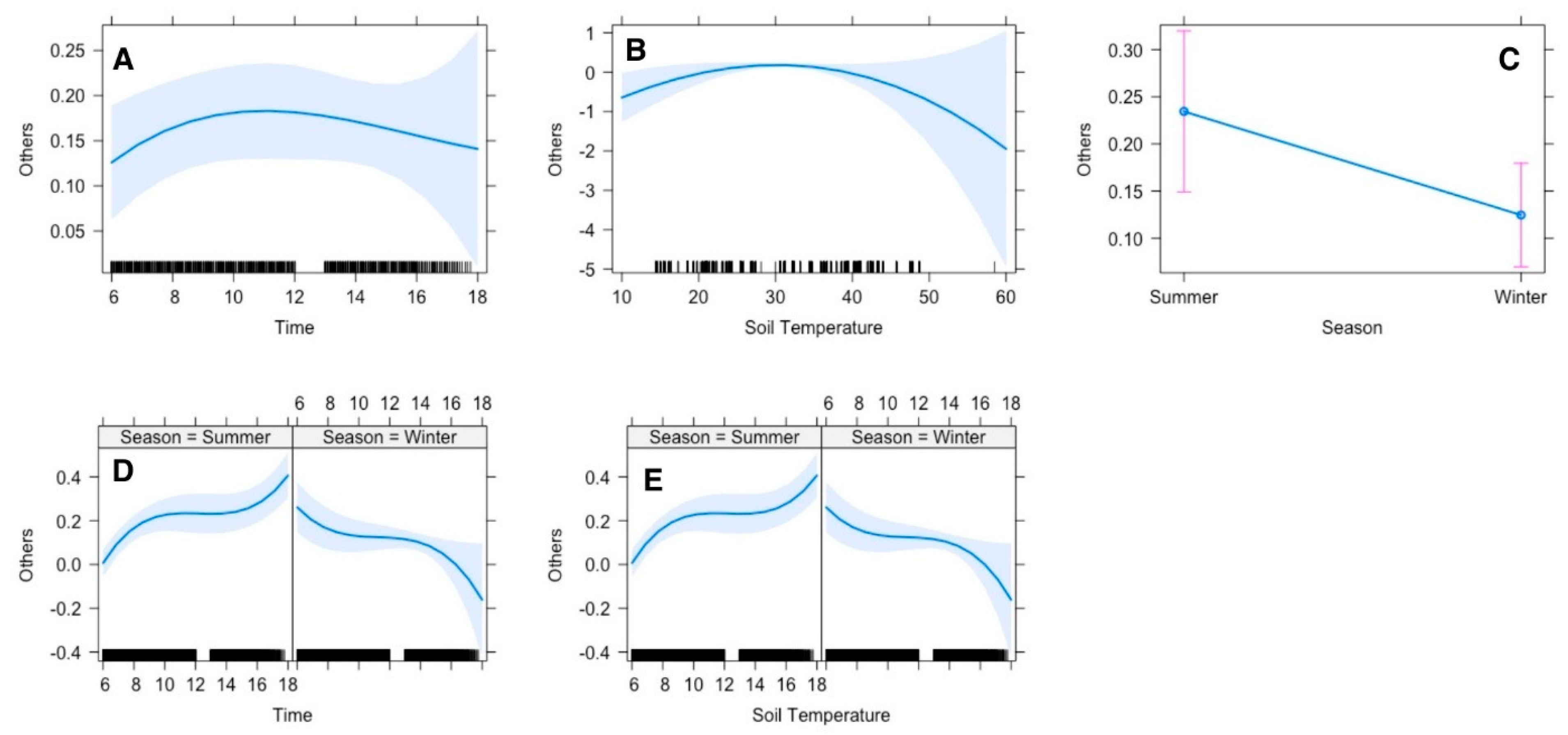

Regression analysis suggested that the gazelle’s time allocation for other activities (social interactions, urinating, defecating, grooming. sexual behaviors) was significantly influenced by season, and soil temperature. The time gazelles spent in other activities was constant throughout the observation period, which means it could occur at any time of the day (

Figure 7A). However, if we compare the two seasons, in summer they spent much time in other activities in late afternoon, while in winter the peak time was in the early morning (

Figure 7D). In summer, they performed the other activities more than in winter by nearly 25% (

Figure 7C). The optimal soil temperature recorded was ranged between 25–40 °C, at which gazelles tend to perform other activities frequently (

Figure 7B). However in summer the activities increased every hour till it reaches the highest spending time at 18:00 pm, while in winter the peak time was at 6:00 am with a quadric relationship between them (

Figure 7B).

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge the current study seems first-ever ambitious effort towards assessing the seasonal activity patterns of Arabian sand gazelle in captivity. Results obtained in the current study revealed noticeable impacts of seasons along with other factors like temperature and time of the day on the behavioral displays. Feeding was the most dominant behavioral display among both seasons, yet a bit higher in summer as compared to winter. It is reported that desert dwelling ungulates tend to eat more in summer order to meet the energetic costs to cope with heat stress [

34]. Our results for the Arabian sand gazelle run parallel to the aforementioned findings. The average annual temperature of study area is 29 °C, which can be considered pretty higher. Keeping in view the average temperature of the study area, we assume that such persisting high temperature dose not force gazelles for eating much in winter to raise their body temperature.

A negative correlation was found between soil temperatures and feeding i.e. lower the soil temperature, higher was feeding rate and vice versa (

Figure 5). Although our study animals were mostly provided with supplemental feed, yet there can be possible innate behaviors behind this trend. It is reported that gazelles primarily are browsing animals, yet simultaneously they graze and dig soil with their hooves to eat nutritious bulbs and roots [

35]. Since the climate of the Arabian Peninsula during summer is characterized by extreme soil temperatures exceeding up to 60°C, resulting in no eruption of ground level forages–thus limiting feeding [

36]. In our findings feeding activity was lowest in early morning, followed by a minor increase until noon, and then a sharp increase was observed in late afternoon till evening (after 16:00–18:00 pm). However, our results were slightly contrary to the aforementioned findings for morning hours. We presume that such trend observed may probably because of the possible bias in the results due to husbandry and management procedures, the most important of which is the feed supply. Our study animals were sharing the space with Arabian oryx which is a dominant and powerful competitors to gazelles. Therefore we strongly assume that Arabian oryx thus preventing gazelles from approaching feed once served in the morning by rangers–resulting an extended feeding activity by gazelles in the evening. Similar findings have been reported for Indian gazelle (

Gazella bennettii) living in mixed specie exhibits with Punjab urials (

Ovis vignei punjabiensis) [

31].

Our results revealed that with a significant impact of time of the day only, the time activity budget for walking by Arabian sand gazelle was 22% in summer and 14% in winter. As mentioned before that summer temperatures in our study area are extremely high [

36], which we presume is a triggering factor of extensive walking of Arabian sand gazelles–predominantly seeking shelter to avoid heat stress [

27]. It is believed that daily excursion activities in wild ungulates reach a peak level at dawn and dusk, with sharp declines in the afternoon [

13]. Our findings are supported by the statement mentioned above. However the compared results for walking in both seasons revealed that, Arabian sand gazelle displayed higher walking frequency at morning in winter whereas in summer this trend was observed in late afternoon and evening (

Figure 6). We believe that such movement patterns are facilitated by lower temperatures at these hours of the day, thus by shifting activities towards cooler periods of the day [

13,

37].

Laying down and standing were significantly affected by season, air and soil temperatures; and time of the day respectively (

Figure 3). Frequency and duration for laying down was pretty lower at ≤15 °C, however increased with increasing temperature up to 25 °C. To avoid heat dissipation, it is believed that heterotherms tends to avoid frequent and lengthy body contacts with cold soil [

38]. Furthermore gazelles spent much time in standing during summer as compared to winters. We believe that with rising temperatures (>25 °C) gazelles adopted this strategy to avoid extreme heat stress by lifting up their bodies from the ground levels [

13,

37].

In gregarious ungulates social interactions are of great importance to maintain herd structures and propagation. These interactions included agonistic and affinitive interactions like chase, blocking, parallel walk, fighting and thrusting, play, allogrooming, licking and sexual behaviors [

31]. Display of the behaviors mention above in confined areas is a sign of healthy social enrichment (Khattak et al., 2019). In addition to stay hygienic, animal’s also spare time to grooming, dust baths which keeps the dirt, debris and parasites at bay [

39]. Our results revealed that Arabian sand gazelle performed the other activities more in summer than in winter by nearly 25% (

Figure 7C), when the optimal temperature recorded ranged between 25–40 °C. Defecation was observed much more frequently in summer as compared to winter. We attribute this trend to the higher feeding rates displayed by our study animals in summers as compared to winter. Although summer temperature in our study remains high, yet, having coastal areas in proximity the humidity levels are considerable [

29]. We presume that such climate is very favorable for the exponential propagation of parasites [

40,

41]. Therefore we strongly believe that behaviors like allogrooming, licking and dust baths in Arabian sand gazelle significantly increases in summer than in winter.

5. Conclusions

The results obtained in the current study provide insights in into the variations in the seasonal activity patterns of Arabian sand gazelles in captivity. Findings of the current study goes counter to our hypothesis–revealing that Arabian sand gazelles are much more active in summer than in winter. In addition, Arabian sand gazelles possess great capability of switching behaviors and trading off, as evident from walking, laying down and feeding behaviors. Moreover Arabian sand gazelles displayed higher level of maintenance behaviors and social interactions in summer than in winter. Since our study animals are also provided with supplemental feed, therefore it is recommended to check the impact of feed types and human presence on the behavior of Arabian sand gazelle. It is advised to investigate the welfare conditions of these animals and to suggest recommendations for optimal animal welfare. Furthermore, we strongly recommend a long term monitoring to investigate the effects of the climatic factors and Arabian Oryx on the behavior of Arabian sand gazelle at Al-Reem Biosphere Reserve, and surrounding areas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M. and M.A.N.; methodology, N.M.; software, M.A.N.; validation, M.A.N. and R.H.K.; formal analysis, M.A.N.; investigation, N.M.; resources, M.A.N.; data curation, N.M.; writing—original draft preparation N.M. and R.H.K.; writing—review and editing, M.A.N. and R.H.K.; visualization, M.A.N. and R.H.K.; supervision, M.A.N.; project administration, M.A.N.; funding acquisition, M.A.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We are thankful to the Qatar’s University for providing financial support for this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data obtained is presented in this article.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the Qatar’s Ministry of Environment and Climate Change for providing access to the Al-reem reserve

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rahman, D.A.; Rianti, P.; Muhiban, M.; Muhtarom, A.; Rahmat, U.M.; Santosa, Y.; Aulagnier, S. Density and Spatial Partitioning of Endangered Sympatric Javan Leopard (Felidae) and Dholes (Canidae) in a Tropical Forest Landscape. Folia Zool. 2018, 67, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfirio, G.; Foster, V.C.; Fonseca, C.; Sarmento, P. Activity Patterns of Ocelots and Their Potential Prey in the Brazilian Pantanal. Mamm. Biol. 2016, 81, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronfeld-Schor, N.; Dayan, T. Partitioning of Time as an Ecological Resource. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2003, 34, 153–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, W.J. The Importance of Behavioural Studies in Conservation Biology. Anim. Behav. 1998, 56, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davimes, J.G.; Alagaili, A.N.; Bertelsen, M.F.; Mohammed, O.B.; Hemingway, J.; Bennett, N.C.; Manger, P.R.; Gravett, N. Temporal Niche Switching in Arabian Oryx (Oryx Leucoryx): Seasonal Plasticity of 24 h Activity Patterns in a Large Desert Mammal. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 177, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krop-Benesch, A.; Berger, A.; Hofer, H.; Heurich, M. Long-Term Measurement of Roe Deer (Capreolus Capreolus)(Mammalia: Cervidae) Activity Using Two-Axis Accelerometers in GPS-Collars. Ital. J. Zool. 2013, 80, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, R. Behavioural Biology: An Effective and Relevant Conservation Tool. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newby, J.; Wacher, T.; Durant, S.M.; Pettorelli, N.; Gilbert, T. Desert Antelopes on the Brink: How Resilient Is the Sahelo-Saharan Ecosystem? Antelope Conserv. from diagnosis to action 2016, 253–279. [Google Scholar]

- Abáigar, T.; Cano, M.; Ensenyat, C. Time Allocation and Patterns of Activity of the Dorcas Gazelle (Gazella Dorcas) in a Sahelian Habitat. Mammal Res. 2018, 63, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giotto, N.; Picot, D.; Maublanc, M.-L.; Gerard, J.-F. Effects of Seasonal Heat on the Activity Rhythm, Habitat Use, and Space Use of the Beira Antelope in Southern Djibouti. J. Arid Environ. 2013, 89, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, J.W.; Jansen, B.D.; Wilson, R.R.; Krausman, P.R. Potential Thermoregulatory Advantages of Shade Use by Desert Bighorn Sheep. J. Arid Environ. 2008, 72, 1518–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.R.; Krausman, P.R. Possibility of Heat-Related Mortality in Desert Ungulates. J. Arizona-Nevada Acad. Sci. 2008, 40, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, D.; Li, Y. Antelope Adaptations to Counteract Overheating and Water Deficit in Arid Environments. J. Arid Land 2022, 14, 1069–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, A.; Kamerman, P.R.; Maloney, S.K.; Matthee, A.; Mitchell, G.; Mitchell, D. A Year in the Thermal Life of a Free-Ranging Herd of Springbok Antidorcas Marsupialis. J. Exp. Biol. 2005, 208, 2855–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Launay, F.; Launay, C. Daily Activity and Social Organization of the Goitered Gazelle (Gazella Subgutturosa Marica). Ungulates 1992, 91, 373–377. [Google Scholar]

- Estes, R.D. The Behavior Guide to African Mammals. Berkeley and Los Angeles 1991.

- Giotto, N.; Laurent, A.; Mohamed, N.; Prevot, N.; Gerard, J.-F. Observations on the Behaviour and Ecology of a Threatened and Poorly Known Dwarf Antelope: The Beira (Dorcatragus Megalotis). Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2008, 54, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyers, M.; Parrini, F.; Owen-Smith, N.; Erasmus, B.F.N.; Hetem, R.S. How Free-Ranging Ungulates with Differing Water Dependencies Cope with Seasonal Variation in Temperature and Aridity. Conserv. Physiol. 2019, 7, coz064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallon, D.P.; Hilton-Taylor, C.; Amori, G.; Baldwin, R.; Bradshaw, P.L.; Budd, K. The Conservation Status and Distribution of the Mammals of the Arabian Peninsula. 2023.

- Delany, M.J. The Zoogeography of the Mammal Fauna of Southern Arabia. Mamm. Rev. 1989, 19, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legge, A.J.; Rowley-Conwy, P.A. Gazelle Killing in Stone Age Syria. Sci. Am. 1987, 257, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thouless, C.R.; Grainger, J.G.; Shobrak, M.; Habibi, K. Conservation Status of Gazelles in Saudi Arabia. Biol. Conserv. 1991, 58, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, P.L.; Wacher, T. Changes in the Distribution, Abundance and Status of Arabian Sand Gazelle (Gazella Subgutturosa Marica) in Saudi Arabia: A Review. 2009.

- Bar-Oz, G.; Zeder, M.; Hole, F. Role of Mass-Kill Hunting Strategies in the Extirpation of Persian Gazelle (Gazella Subgutturosa) in the Northern Levant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108, 7345–7350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.N.; Smith, T.R. Reintroduction of Arabian Sand Gazelle Gazella Subgutturosa Marica in Saudi Arabia. Biol. Conserv. 1996, 76, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group.

- Hetem, R.S.; Strauss, W.M.; Fick, L.G.; Maloney, S.K.; Meyer, L.C.R.; Shobrak, M.; Fuller, A.; Mitchell, D. Activity Re-Assignment and Microclimate Selection of Free-Living Arabian Oryx: Responses That Could Minimise the Effects of Climate Change on Homeostasis? Zoology 2012, 115, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillitoe, P.; Alshawi, A.A.; Al-Amir Hassan, A.K. Challenges to Conservation: Land Use Change and Local Participation in the Al Reem Biosphere Reserve, West Qatar. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2010, 6, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayed, N.J. , Al Naemi, J.B., Anna, P., Donia, A., Tarek, A. Al Reem Biosphere Reserve, Educational and Awareness Booklet. Available online: https://www.mme.gov.qa/static/cat_doc/env/AlreemBiosphereReserveEnglishSide.pdf/.

- Martin, P.; Bateson, P.P.G.; Bateson, P. Measuring Behaviour: An Introductory Guide; Cambridge University Press, 1993; ISBN 0521446147.

- Khattak, R.H.; Teng, L.; Mehmood, T.; Rehman, E.U.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z. Hostile Interactions of Punjab Urial (Ovis Vignei Punjabiensis) towards Indian Gazelle (Gazella Bennettii) during Feeding Sessions in Captive Breeding Settings. Animals 2021, 11, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.-S.; Kim, B.-J.; Jang, G.-S. Modelling the Spatial Distribution of Wildlife Animals Using Presence and Absence Data. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2016, 9, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, R.C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2013.

- Hilde, G.P.; Innis, D.A. The Camel, Its Evolution, Ecology, Behavior, and Relationship to Man. 1981.

- Schulz, E.; Fraas, S.; Kaiser, T.M.; Cunningham, P.L.; Ismail, K.; Wronski, T. Food Preferences and Tooth Wear in the Sand Gazelle (Gazella Marica). Mamm. Biol. 2013, 78, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babor, H.; Okab, A.B.; Samara, E.M.; Abdoun, K.A.; Omar, A.-T.; Al-Haidary, A.A. Adaptive Thermophysiological Adjustments of Gazelles to Survive Hot Summer Conditions. Pak. J. Zool. 2014, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, D.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Meng, D.; Liang, Y.; Hu, T.; Teng, L.; Liu, Z. The Activity Patterns and Grouping Characteristics of the Remaining Goitered Gazelle (Gazella Subgutturosa) in an Isolated Habitat of Western China. Animals 2024, 14, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobrial, L.I.; Cloudsley-Thompson, J.L. Daily Cycle of Activity of the Dorcas Gazelle in the Sudan. Biol. Rhythm Res. 1976, 7, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, G.M.W.; Flay, K.J.; Perroux, T.A.; McElligott, A.G. You Lick Me, I like You: Understanding the Function of Allogrooming in Ungulates. Mamm. Rev. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, R.H.; Zhensheng, L.I.U.; Liwei, T.; Ahmed, S.; Shah, S.S.A.; Abdel-Hakeem, S.S. Investigation on Parasites and Some Causes of Mortality in Captive Punjab Urial (Ovis Vignei Punjabiensis), Pakistan. Iran. J. Parasitol. 2021, 16, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzebny, A.; Nahimova, O.; Dabert, M. High Temperatures and Low Humidity Promote the Occurrence of Microsporidians (Microsporidia) in Mosquitoes (Culicidae). Parasit. Vectors 2024, 17, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 2.

Spread of diurnal time activity budgets of Arabian sand gazelle.

Figure 2.

Spread of diurnal time activity budgets of Arabian sand gazelle.

Figure 3.

Effect of environmental conditions on diurnal activity pattern (laying down) of Arabian sand gazelles in Al-Reem Reserve, Qatar. The plot illustrates the laying down pattern based on the final selected model. The blue line represents the model’s fitted line, depicting the predicted feeding activity levels throughout the day. The shaded area surrounding the line indicates the 95% confidence interval (CI), providing a measure of uncertainty in the model predictions. The black line on the x-axis represents the scale. This visualization offers insights into how environmental factors influence the diurnal feeding behavior of Arabian sand gazelles in Al-Reem Reserve.

Figure 3.

Effect of environmental conditions on diurnal activity pattern (laying down) of Arabian sand gazelles in Al-Reem Reserve, Qatar. The plot illustrates the laying down pattern based on the final selected model. The blue line represents the model’s fitted line, depicting the predicted feeding activity levels throughout the day. The shaded area surrounding the line indicates the 95% confidence interval (CI), providing a measure of uncertainty in the model predictions. The black line on the x-axis represents the scale. This visualization offers insights into how environmental factors influence the diurnal feeding behavior of Arabian sand gazelles in Al-Reem Reserve.

Figure 4.

Effect of environmental conditions on diurnal activity pattern (standing) of Arabian sand gazelles in Al-Reem Reserve, Qatar. The plot illustrates the diurnal feeding activity pattern based on the final selected model. The blue line represents the model’s fitted line, depicting the predicted feeding activity levels throughout the day. The shaded area surrounding the line indicates the 95% confidence interval (CI), providing a measure of uncertainty in the model predictions. The black line on the x-axis represents the scale. This visualization offers insights into how environmental factors influence the diurnal feeding behavior of Arabian sand gazelles in Al-Reem Reserve.

Figure 4.

Effect of environmental conditions on diurnal activity pattern (standing) of Arabian sand gazelles in Al-Reem Reserve, Qatar. The plot illustrates the diurnal feeding activity pattern based on the final selected model. The blue line represents the model’s fitted line, depicting the predicted feeding activity levels throughout the day. The shaded area surrounding the line indicates the 95% confidence interval (CI), providing a measure of uncertainty in the model predictions. The black line on the x-axis represents the scale. This visualization offers insights into how environmental factors influence the diurnal feeding behavior of Arabian sand gazelles in Al-Reem Reserve.

Figure 5.

Effect of environmental conditions on diurnal activity pattern (feeding) of Arabian sand gazelles in Al-Reem Reserve, Qatar. The plot illustrates the diurnal feeding activity pattern based on the final selected model. The blue line represents the model’s fitted line, depicting the predicted feeding activity levels throughout the day. The shaded area surrounding the line indicates the 95% confidence interval (CI), providing a measure of uncertainty in the model predictions. The black line on the x-axis represents the scale. This visualization offers insights into how environmental factors influence the diurnal feeding behavior of Arabian sand gazelles in Al-Reem Reserve.

Figure 5.

Effect of environmental conditions on diurnal activity pattern (feeding) of Arabian sand gazelles in Al-Reem Reserve, Qatar. The plot illustrates the diurnal feeding activity pattern based on the final selected model. The blue line represents the model’s fitted line, depicting the predicted feeding activity levels throughout the day. The shaded area surrounding the line indicates the 95% confidence interval (CI), providing a measure of uncertainty in the model predictions. The black line on the x-axis represents the scale. This visualization offers insights into how environmental factors influence the diurnal feeding behavior of Arabian sand gazelles in Al-Reem Reserve.

Figure 6.

Effect of environmental conditions on diurnal activity pattern (walking) of Arabian sand gazelles in Al-Reem Reserve, Qatar. The plot illustrates the diurnal feeding activity pattern based on the final selected model. The blue line represents the model’s fitted line, depicting the predicted feeding activity levels throughout the day. The shaded area surrounding the line indicates the 95% confidence interval (CI), providing a measure of uncertainty in the model predictions. The black line on the x-axis represents the scale. This visualization offers insights into how environmental factors influence the diurnal feeding behavior of Arabian sand gazelles in Al-Reem Reserve.

Figure 6.

Effect of environmental conditions on diurnal activity pattern (walking) of Arabian sand gazelles in Al-Reem Reserve, Qatar. The plot illustrates the diurnal feeding activity pattern based on the final selected model. The blue line represents the model’s fitted line, depicting the predicted feeding activity levels throughout the day. The shaded area surrounding the line indicates the 95% confidence interval (CI), providing a measure of uncertainty in the model predictions. The black line on the x-axis represents the scale. This visualization offers insights into how environmental factors influence the diurnal feeding behavior of Arabian sand gazelles in Al-Reem Reserve.

Figure 7.

Effect of environmental conditions on diurnal activity pattern (others) of Arabian sand gazelles in Al-Reem Reserve, Qatar. The plot illustrates the diurnal feeding activity pattern based on the final selected model. The blue line represents the model’s fitted line, depicting the predicted feeding activity levels throughout the day. The shaded area surrounding the line indicates the 95% confidence interval (CI), providing a measure of uncertainty in the model predictions. The black line on the x-axis represents the scale. This visualization offers insights into how environmental factors influence the diurnal feeding behavior of Arabian sand gazelles in Al-Reem Reserve.

Figure 7.

Effect of environmental conditions on diurnal activity pattern (others) of Arabian sand gazelles in Al-Reem Reserve, Qatar. The plot illustrates the diurnal feeding activity pattern based on the final selected model. The blue line represents the model’s fitted line, depicting the predicted feeding activity levels throughout the day. The shaded area surrounding the line indicates the 95% confidence interval (CI), providing a measure of uncertainty in the model predictions. The black line on the x-axis represents the scale. This visualization offers insights into how environmental factors influence the diurnal feeding behavior of Arabian sand gazelles in Al-Reem Reserve.

Table 1.

Ethogram designed and used for behavioral observation of Arabian sand gazelle.

Table 1.

Ethogram designed and used for behavioral observation of Arabian sand gazelle.

| s.no |

Behavior Pattern |

Description of Behavior |

| 1 |

Walking |

When an animal is running or walking from one place to another |

| 2 |

Feeding |

Feeding included foraging, searching for food, ruminating and drinking |

| 3 |

Laying down |

Animal found laying down still with eyes opened or closed |

| 4 |

Standing |

When an animal is standing still without any signs of alertness |

| 5 |

Others |

Others included social interactions, urinating, defecating, maintenance, sexual behaviors |

Table 2.

Comparison of initial and final models for predicting Arabian sand gazelle behaviors based on AIC and Log-Likelihood values.

Table 2.

Comparison of initial and final models for predicting Arabian sand gazelle behaviors based on AIC and Log-Likelihood values.

| Response |

Model |

AIC |

Log-Likelihood |

| Standing |

Initial Model |

1089.2 |

−530.60 |

| |

Final Model |

970.2 |

−475.10 |

| Walking |

Initial Model |

1153.7 |

−562.85 |

| |

Final Model |

1005.8 |

−491.90 |

| Feeding |

Initial Model |

1102.4 |

−537.20 |

| |

Final Model |

987.6 |

−481.80 |

| Laying |

Initial Model |

1201.6 |

−593.80 |

| |

Final Model |

1018.7 |

−502.35 |

| Others |

Initial Model |

1032.5 |

−504.25 |

| |

Final Model |

960.1 |

−460.05 |

Table 3.

Parameter estimates of polynomial regression models using gazelle’s activities as dependent variable. p-values are provided in parenthesis, and parameters with non-significant effects (p > 0.05) are excluded. Superscripts “2” and “3” indicate quadratic and cubic effects in the model.

Table 3.

Parameter estimates of polynomial regression models using gazelle’s activities as dependent variable. p-values are provided in parenthesis, and parameters with non-significant effects (p > 0.05) are excluded. Superscripts “2” and “3” indicate quadratic and cubic effects in the model.

| Variables |

Feeding |

Walking |

Laying Down |

Standing |

Others |

| Season (winter) |

−10.3

(1.28 *10−8) |

- |

27.4

(0.017) |

2.46

(0.007) |

- |

| Time |

−1.12

1.69 *10−21

|

- |

- |

0.38

(0.0058) |

- |

| Time 2

|

0.150

(4.47 *10−11) |

−0.03

(0.) |

- |

−0.034

(0.004) |

−0.03

(0.0003) |

| Time 3

|

−0.003

(3.06 *10−11) |

0.001

(0.002) |

- |

0.0009

(0.006) |

0.0009

(0.0008) |

| Air Temperature |

- |

- |

3.04

(0.005) |

- |

- |

| Air Temperature 2

|

- |

- |

−0.090

(0.005) |

- |

- |

| Air Temperature 3

|

-

|

|

0.0008

(0.005) |

- |

- |

| Soil Temperature |

- |

- |

- |

- |

−3.04

(0.002) |

| Soil Temperature 2

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

−0.009

(0.0006) |

| Soil Temperature 3

|

- |

- |

−7.71

(0.03) |

- |

8.91

(0.0002) |

| Season: Winter—Air temperature |

- |

- |

−3.0

(0.009) |

- |

NA |

| Season: Winter —Air temperature 2

|

- |

- |

0.091

(0.017) |

|

NA |

| Season: Winter —Air temperature 3

|

- |

- |

−0.0009

(0.039) |

|

NA |

| Season: Winter —Soil temperature |

-

|

- |

0.62

(0.012) |

|

−0.49

(0.002) |

| Season: Winter —Soil temperature 2

|

- |

- |

−0.02

(0.0071) |

|

0.017

(0.0019) |

| Season: Winter —Soil temperature—3

|

- |

- |

0.0003

(0.0072) |

|

−0.0002

(0.0049) |

| Season: Winter —Time |

3.001

(3.62*10−21) |

- |

|

−0.73

(0.006) |

−0.77

(0.00028) |

| Season: Winter —Time 2

|

−0.27

(7.88*10−21) |

- |

|

−0.06

(0.008) |

0.06

(0.0009) |

| Season: Winter —Time 3

|

0.008

(3.201 *10−20) |

- |

|

−0.001

(0.013) |

−0.001

(0.0017) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).