1. Introduction

Optimal foraging theory suggests that animals prefer to choose food that is high in energy while minimizing effort (Pyke et al., 1977; Stephens & Krebs, 1986). This theory predicts that when animals have to choose between two tasks to get the same food reward, they will choose the easier one. However, many studies have shown that when faced with an equal amount of food resources, animals prefer to work for their food rather than take free food. This phenomenon contradicts the optimal foraging theory and is known as contrafreeloading (CFL) (Jensen, 1963; Inglis et al., 1997).

CFL has been widely reported in laboratory, captive, and domesticated animals, such as laboratory rats (Rattus norvegicus), laboratory pigeons (Columba livia), captive maned wolves (Chrysocyon brachyurus), captive rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta), red jungle fowl (Gallus gallus), and pigs (Sus scrofa) (Jensen, 1963; Neuringer, 1969; Vasconcellos et al., 2012; Reinhardt, 1994; Lindqvist & Jensen, 2008; de Jonge et al., 2008). Some wild animals in captivity also show a tendency for CFL. For example, McGowan et al. (2010) found that captive wild grizzly bears (Ursus arctos horribilis) spent more time opening food boxes to get food rather than taking free food. CFL has also been reported in humans. Tarte (1981) found that young people preferred to press a lever to get candy or cash rewards rather than take them directly.

Inglis et al. (1997) proposed five possible explanations for this seemingly counterintuitive behavior. Prior training theory suggests that the training process to obtain food serves as a stimulus and becomes a secondary reinforcer, resulting in animals having more challenging foraging behavior even when free food is available. Neophobia theory suggests that the training needed for a task causes animals to fear the free food provided. Stimulus change theory proposes that any form of sensory change is beneficial, and animals will seek to alter their environment by searching for food, creating novelty. Information primacy theory argues that the process of working for food provides useful information for future foraging. Self-reinforcing theory suggests that the effort animals put into obtaining food is self-satisfying.

From the above explanations, several potential factors might affect CFL levels. First, according to prior training theory and neophobia theory, foraging training may affect animals' CFL levels. The training process can serve as a stimulus reinforcer or make animals fear free food, leading to higher CFL levels. However, few experimental studies have compared the impact of foraging training on CFL levels. Second, according to information primacy theory, the process of working for food provides useful information for future foraging. However, when the motivation to gather information is replaced by a stronger feeding motivation (such as hunger), information-gathering behavior decreases (Inglis & Ferguson, 1986). This suggests that animals may show different levels of CFL under different food deprivation levels. Finally, self-reinforcing theory predicts that the effort required to obtain food can also affect the level of CFL. On the one hand, animals gain satisfaction from the effort of obtaining food, increasing their motivation to persist in challenging foraging tasks (Sasson-Yenor & Powell, 2019). On the other hand, if the difficulty is too high and animals cannot gain satisfaction from overcoming it, they will stop foraging, leading to the disappearance of CFL (Inglis et al., 1997).

Budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus) are small climbing birds belonging to the order Psittaciformes, family Psittacidae, genus Melopsittacus. They are common subjects in animal cognition research. Previous studies have shown that trained budgerigars can complete complex tasks to obtain food, and their problem-solving ability is related to their exploratory behavior (Chen et al., 2019). Therefore, budgerigars are ideal subjects for studying CFL and its influencing factors. This study sets up three potential factors to observe budgerigars' choices among different challenge feeders, aiming to analyze the effects of prior training, food deprivation, and effort required on the level of CFL, and to explore the mechanisms underlying CFL in vertebrates.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects and Apparatus

2.1.1. Subjects

This study involved 12 adult budgerigars (six males and six females) as the study subjects. All budgerigars were procured from the Hefei Yufeng Market. Healthy and active budgerigars were selected, and none had prior experience with foraging task training. The budgerigars were housed in a well-ventilated animal room with a day-night light cycle. Four birds were placed in each wire cage, with free access to food and water. The food provided was dry, shelled grains. Researchers can identify individuals based on external characteristics such as size and feather color.

2.1.2. Apparatus

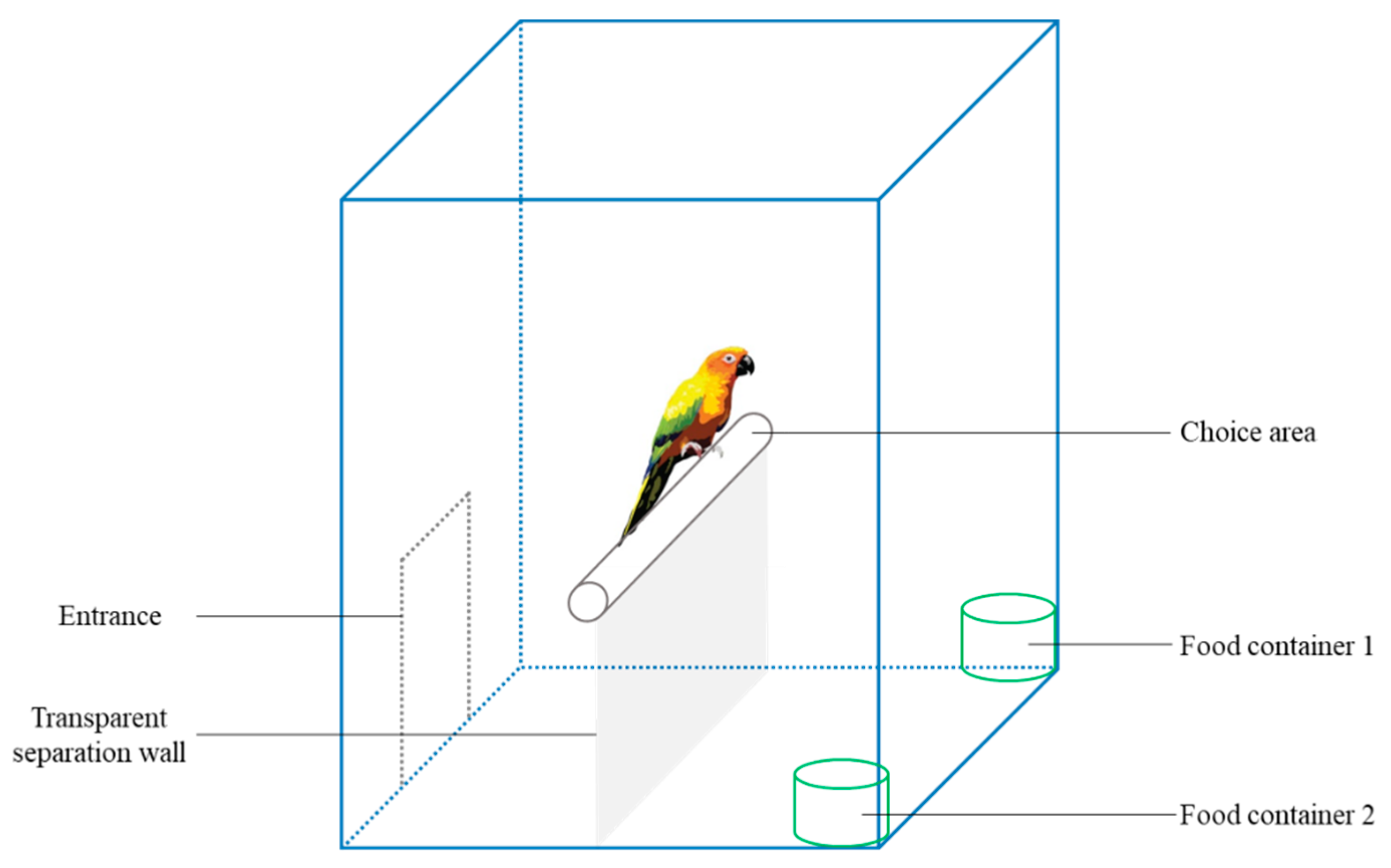

We conducted the experiments in a small birdcage (24.5×17×15 cm), which included a choice area and two food containers (one being easy and another challenging to obtain food) (

Figure 1). The budgerigars entered the cage through an entrance into an adaptation buffer area between the entrance and a transparent partition (made of glass). The transparent partition prevented agitated animals from entering the food area and affecting the accuracy of the experiment while allowing the birds to observe the food area. When the budgerigars reached the perch, they could observe the food containers and make choices based on the foraging challenge.

We set three devices for animals to obtain food. Easy: The top of the food container was uncovered, allowing the budgerigars to access the food freely. Moderate challenge (MC): The food in the container was covered with wood shavings, requiring the budgerigars to use their claws or beaks to move the shavings aside to access the food. High challenge (HC): The food in the container was covered with wood shavings and the top was sealed with plastic wrap (weak enough to be pierced by the beaks of the budgerigars). The budgerigars needed to peck open the plastic wrap and move the shavings aside to access the food.

2.2. Pre-Experiment

2.2.1. Habituation

The budgerigars were placed in the experimental preparation room before the formal experiment, preventing the researcher's actions, sounds, and experimental apparatus from causing fear in the animals. Researchers fed the birds by hand and placed the required experimental apparatus around them, allowing the budgerigars to become familiar with the experimental environment. After several days, the budgerigars no longer showed fearful behavior and moved freely in the cage, indicating habituation (Bean et al., 1999).

2.2.2. Pre-Training

We selected six budgerigars (three males and three females) for pre-training. First, for the MC, the budgerigars could see the covered food through the transparent plastic food container. If the budgerigars initially could not obtain the food, researchers would remove the wood shavings to encourage the budgerigars to see and eat the food from the top. Once they successfully obtained the food, the wood shavings were replaced, and researchers observed whether the budgerigars could remove the shavings to eat. We repeated it until the budgerigars could smoothly remove the wood shavings and consume food. Second, for the HC, researchers pierced the plastic wrap to encourage the budgerigars to pierce the wrap and move the wood shavings to eat, and the unpierced plastic wrap was presented until the budgerigars could pierce the wrap and move the shavings to eat. The training ended when all six budgerigars could complete these two steps and successfully obtain the food.

2.3. Procedure

To prevent interference with gender factors, we employed six males and six females in our experiment. Before the formal experiment, researchers identified individual budgerigars based on size, feather color, and specific markings. The experiments were conducted between 9 a.m. and 3 p.m. to avoid the influence of light. Each budgerigar was placed in a 24.5×17×15 cm cage for the experiment, which lasted 10 minutes. We recorded every trial with a camera.

Six budgerigars (three males and three females) were pre-trained, while the others were not. Given that budgerigars' feeding cycles are generally 3-5 hours, we create three food deprivation levels: no deprivation (NDP, free feeding), moderate deprivation (MDP, 4 hours without food), and high deprivation (HDP, 8 hours without food) (Bean et al., 1999).

For each trial, we recorded the budgerigars' ID, gender, training status, and food deprivation levels, placing them in the experimental cage. Once the budgerigars were emotionally stable and freely moving in the cage without visible stress, their food choices were observed and recorded. The study compared choices between Easy and MC, and between Easy and HC. We determined container preferences by the first choice and the proportion of time spent at the MDP/HDP food containers (Sasson-Yenor & Powel, 2019). The time proportion of choice was calculated as follows: time spent at the MDP/HDP food containers / (time spent at the MDP/HDP food containers + time spent at the Easy food containers).

2.4. Data Analysis

The study first compared the first food container choice proportions for budgerigars with NDP. If the proportion choosing challenging food containers exceeded 50%, the budgerigars were considered to show CFL tendencies (Osborne, 1977; Vasconcellos et al., 2012; Sasson-Yenor & Powell, 2019). Additionally, we used paired t-tests to compare the time spent choosing challenging versus Easy food containers for budgerigars with NDP.

To analyze the effecting factors on CFL levels, we constructed two generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) using the binomial error structure and logit link function in R 3.6.3. The dependent variables were the first choice of Easy/MC food containers and Easy/HC food containers. Prior training and food deprivation levels were fixed factors, while individual identity and gender were random variables. The GLMM analysis was performed using the glmer function from the lmerTest package in R (Bates et al., 2012). Another two GLMMs with Gaussian error structure and identity link function were used to analyze the proportion of time spent at MC and HC food containers, with fixed factors and random variables as above. The GLMM analysis was performed using the lmer function from the lmerTest package in R (Bates et al., 2012).

Finally, to compare the impact of feeding challenges on CFL levels, independent sample t-tests were used to compare the proportion of time spent at MC and HC. All data were analyzed with a significance level of 0.05 (two-tailed).

3. Results

We conducted a total of 72 trials in this study. Among them, the animals did not choose in six trials, and these instances occurred under conditions with NDP. In the remaining 66 trials, 40 times they first chose the NDP food containers, which allowed them to obtain food without any effort, and 26 times they chose the challenging food containers, which required effort to access food. The specific choices are detailed in

Table 1.

3.1. Budgerigars' CFL Tendencies

Given that the identification of CFL tendency is based on the choices made by animals without food deprivation, this study compared the first choice and the time proportion of the food containers chosen by the budgerigars with NDP. In the 18 experiments without food deprivation, the budgerigars first chose the Easy food containers eight times and the challenging food containers ten times, with the proportion of selection through effort exceeding 50%. Additionally, a paired t-test showed no significant difference in the time spent between Easy and challenging food containers (t = 1.758, df = 17, p = 0.097). It indicates that budgerigars exhibit CFL tendencies in their food container choices.

3.2. Factors Affecting Budgerigars' First Choice of Food Containers

For the trials set on the choice between MC and Easy food containers, the first choice occurred at 28.19 ± 10.57 s, and the number of times moving between food containers was 1.38 ± 0.31 times. Out of 32 first choices, the budgerigars chose the Easy food containers 23 times and the MC food containers nine times.

Table 2 (MC vs Easy) shows that pre-training (Yes/No) and food deprivation (MDP vs NDP, HDP vs NDP) did not significantly affect the animals' first choice between the MC and Easy food containers.

For the trials set on the choice between HC and Easy food containers, the first choice occurred at 20.38 ± 6.85 s, and the number of round trips between food containers was 1.12 ± 0.25 times. Out of 34 first choices, the budgerigars chose the Easy food containers 17 times and the HC food containers 17 times.

Table 2 (HC vs Easy) shows that the trained animals were more inclined to initially choose the HC food containers (

p = 0.0499), while food deprivation (MDP vs NDP, HDP vs NDP) did not have a significant impact on the animals' first choice.

3.3. Factors Affecting Budgerigars' Selection Time Proportion for Food Containers

For the trials between MC and Easy food containers, the time taken by animals to choose the Easy food containers was 220.56 ± 33.78 s, while the time taken to select the MC food containers was 112.03 ± 29.96 s. The analysis results in

Table 3 (MC vs Easy) show that pre-training (Yes/No) and food deprivation (MDP vs NDP, HDP vs NDP) did not have a significant impact on animals' selection time proportion between MC and Easy food containers.

For the trials between HC and Easy food containers, the time taken by animals to choose the Easy food containers was 335.35 ± 36.12 s, while the time taken to select the HC food containers was 40.26 ± 21.59 s. Analysis in

Table 3 (HC vs Easy) shows that pre-training (Yes/No) has a non-significant but approaching significance (

p = 0.0682) effect on the selection time proportion between HC and Easy food containers, indicating that trained budgerigars tend to choose the HC food containers for foraging. Budgerigars with MDP tend to select the Easy food containers (p = 0.0234), while those with HDP also tend to select the Easy food containers, but not significant (

p = 0.1295).

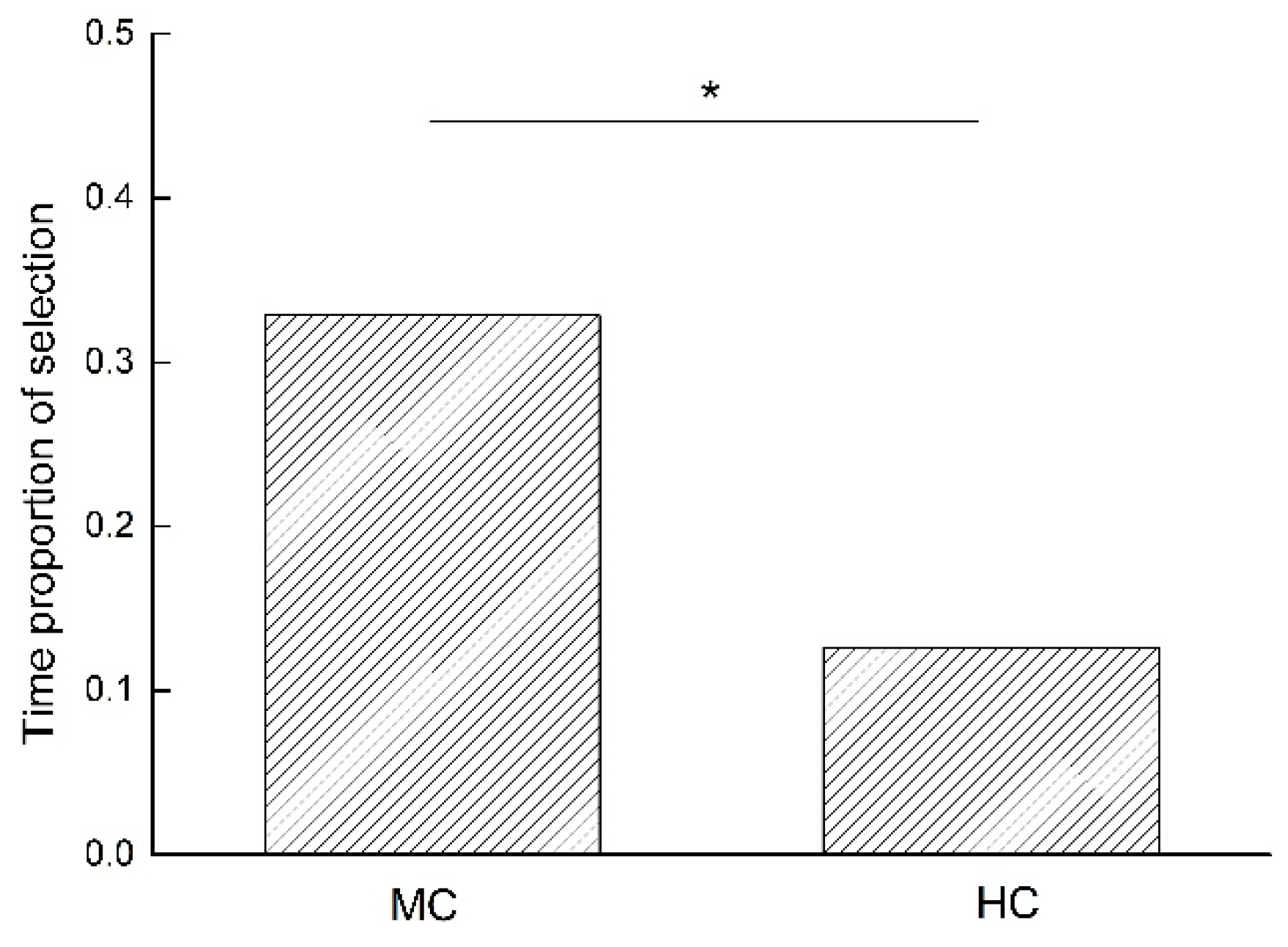

The independent sample T-test analysis showed that budgerigars’ selection time proportion for MC food containers was significantly higher than that for HC food containers (t = 2.316, n = 64,

p = 0.024), as shown in

Figure 2.

4. Discussion

This study conducted the first investigation into the contrafreeloading behavior in budgerigars. The results revealed that, without food deprivation, budgerigars preferred challenging food containers, indicating that budgerigars show tendencies to contrafreeload. Additionally, in examining the influencing factors of CFL levels, we found that pre-training and food deprivation had no significant effect on budgerigars' selection between MC and Easy food containers but did have some influence on the selection between HC and Easy food containers. Specifically, pre-training increased budgerigars' tendency to select HC food containers as their first choice, while MDP reduced the time proportion spent by budgerigars on HC food container selection. Finally, this study compared the time proportion of budgerigars' selection between MC and HC food containers, revealing a preference for MC food containers. Our results indicate that budgerigars, like many other captive and caged animals, showed CFL tendencies. However, the level of CFL was affected by several factors.

CFL is widespread in domesticated and caged animals, and various researchers have explored this behavior from different perspectives based on the animals' living environment and physiological characteristics, aiming to provide reasonable explanations for this phenomenon.

In previous studies, domestic cats were considered the only species that did not show CFL (Delgado et al., 2022). Researchers believe that cats are predatory animals, and their sit-and-wait predation is a low-energy and widespread hunting method (Williams et al., 2014). This foraging style of domestic cats makes them more inclined towards low-energy feeding methods, showing lower CFL tendencies (Delgado et al., 2022). Animals such as domestic pigeons, mice, and giraffes belong to foraging animals, requiring energy expenditure and searching for food (Inglis et al., 1997). Therefore, they are more likely to exhibit CFL tendencies under captive or caged conditions. Budgerigars in this study belong to exploratory foraging animals and exhibit obvious CFL tendencies, demonstrating that foraging style can influence CFL levels.

The definition of CFL is the criterion used by researchers to determine whether animals exhibit CFL tendencies. Some researchers believe that when animals choose to make an effort to obtain food in more than 50% of cases, they exhibit CFL tendencies (Osborne, 1977; Vasconcellos et al., 2012; Sasson-Yenor & Powell, 2019). Other researchers propose that according to the Optimal Foraging Theory, animals should choose free food over effortful food. Therefore, as long as animals select to make an effort to obtain food, they can be considered to exhibit CFL tendencies (Inglis et al., 1997; Mcgowan et al., 2010; Ogura, 2011; Vasconcellos et al., 2012). The budgerigars in this study exhibited CFL tendencies anyway. In fact, according to the original definition of CFL, animals are more likely to choose to make an effort rather than free to obtain food. It suggests that animals' choice to make an effort to consume food exceeds 50%, indicating CFL tendencies. This criterion is also the standard used by most researchers to define whether animals exhibit CFL tendencies. This study concludes that budgerigars exhibit obvious CFL tendencies according to this standard.

In studying CFL, researchers may set up different experimental apparatus based on animal characteristics (such as body size, foraging method, food type, etc.). For example, when studying starlings (Sturnus vulgaris), researchers provided food dishes covered with transparent and opaque plastic membranes for selection (Bean et al., 1999); when studying maned wolves, researchers set up food scattered areas and tray areas for selection (Vasconcellos et al., 2012); when studying domestic cats, researchers set up plates for direct access to food and food puzzle that needed effort to access food (Delgado et al., 2022). Therefore, the inconsistent and diverse experimental settings may also affect animals' choices. In this study, two food containers were set up in the birdcage for the budgerigars, one being an easy-access food container and another requiring the animals to move aside the wood shavings covering the food or open a transparent plastic membrane before moving the wood shavings to access the food. In this way, animals may have their vision obstructed by the wood shavings during feeding. However, since the food containers used in this study were transparent, the animals could see the food in both containers from a straight and downward slanting angle upon entering the feeding area of the cage. Therefore, we believed that the animals' vision would not affect the results of this study.

According to the theory of self-reinforcement mentioned above, if animals cannot achieve satisfaction in overcoming difficulties to obtain food, they will stop feeding, leading to the disappearance of CFL (Inglis et al., 1997). In this study, both the trained and untrained budgerigars had a relatively low success rate in opening the highly challenging containers to access food, leading to a loss of interest in HC food containers and a preference for easy-access food containers. The higher success rate in accessing food in the moderately challenging task confirms this speculation.

According to the information-primacy hypothesis, hungry animals are more inclined towards free food and exhibit lower CFL levels (Inglis et al., 1997; 2001). In the HC/Easy food container selection trials of this study, budgerigars with food deprivation showed lower CFL levels, similar to the results of red jungle fowl and starlings (Lindqvist et al., 2002; Inglis & Ferguson, 1986), indicating that animals exhibit lower CFL levels when hungry, supporting this theory.

Besides, many other factors have been suggested to affect CFL levels, such as age (McGowan et al., 2010), sex (Andrews et al., 2015), physical state (Sasson-Yenor & Powell, 2019), food competition (Andrews et al., 2015), play opportunity (Smith et al., 2021), behavioral pathology (van Zeeland et al., 2023), and so on. The involved factors from our study come from the five proposed explanations of Inglis et al. (1997), applying to most animals that show CFL tendencies. Future studies might investigate the species-specific influencing factors on CFL levels.

5. Conclusions

Budgerigars show tendencies for contrafreeloading. Budgerigars have bright feather colors, lively temperaments, and ease of domestication, are highly favored by bird lovers, and are commonly kept captive animals. Additionally, due to budgerigars' good cognitive learning abilities, they are also often used as experimental model animals (Chen et al., 2019). The results of this study indicate that budgerigars tend to engage in more foraging behavior rather than simple feeding activities with no food deprivation, having implications for the feeding of budgerigars by appropriately setting foraging environments to ensure their animal welfare. Furthermore, the training experience, food deprivation, and effort required can affect their CFL levels, which lays a theoretical foundation for the subsequent study of vertebrate CFL.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.X.Z. and Y.Z.; methodology, Q.X.Z., Y.T., Y.T.Z., H.L.; validation, Y.Z.; formal analysis, Q.X.Z.; investigation, Q.X.Z.; resources, Y.Z.; data curation, Y.T., Y.T.Z., H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.X.Z., Y.T., Y.T.Z., H.L.; writing—review and editing, Q.X.Z. and Y.Z.; visualization, Y.Z; supervision, Y.Z; project administration, Q.X.Z.; funding acquisition, Q.X.Z. and Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was made possible with the help of a grant received from the Research Foundation for Talented Scholars of Hefei Normal University (2020rcjj46 and 2022rcjj47).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Research protocols reported in this manuscript were permitted by the Institutional Committee for Animal Care and Use of Hefei Normal University.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ming Geng and Jing Chen for their help and support throughout our study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Andrews, C.; Viviani, J.; Egan, E.; Bedford, T.; Brilot, B.; Nettle, D.; Bateson, M. Early life adversity increases foraging and information gathering in European starlings, Sturnus vulgaris. Anim. Behav. 2015, 109, 123–132. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, D., Maechler, M., & Bolker, B. (2012). lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes. R package version 0.999999-0. http:// CRAN.R-project.org/packa ge=lme4.

- Bean, D.; Mason, G.; Bateson, M. Contrafreeloading in starlings: testing the information hypothesis. Behaviour 1999, 136, 1267–1282. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zou, Y.; Sun, Y.-H.; Cate, C.T. Problem-solving males become more attractive to female budgerigars. Science 2019, 363, 166–167. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcellos, A.d.S.; Adania, C.H.; Ades, C. Contrafreeloading in maned wolves: Implications for their management and welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012, 140, 85–91. [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, F. H., Tilly, S. L., Baars, A. M., & Spruijt, B. M. (2008). On the rewarding nature of appetitive feeding behaviour in pigs (Sus scrofa): Do domesticated pigs contrafreeload? Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 114(3-4): 359–372.

- Delgado, M.M.; Han, B.S.G.; Bain, M.J. Domestic cats (Felis catus) prefer freely available food over food that requires effort. Anim. Cogn. 2022, 25, 95–102. [CrossRef]

- Inglis, I.; Ferguson, N. Starlings search for food rather than eat freely-available, identical food. Anim. Behav. 1986, 34, 614–617. [CrossRef]

- Inglis, I.; Forkman, B.; Lazarus, J. Free food or earned food? A review and fuzzy model of contrafreeloading. Anim. Behav. 1997, 53, 1171–1191. [CrossRef]

- Inglis, I.R.; Langton, S.; Forkman, B.; Lazarus, J. An information primacy model of exploratory and foraging behaviour. Anim. Behav. 2001, 62, 543–557. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, G.D. Preference for bar pressing over "freeloading" as a function of number of rewarded presses.. J. Exp. Psychol. 1963, 65, 451–454. [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, C.; Jensen, P. Effects of age, sex and social isolation on contrafreeloading in red junglefowl (Gallus gallus) and White Leghorn fowl. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 114, 419–428. [CrossRef]

- McGowan, R.T.S.; Robbins, C.T.; Alldredge, J.R.; Newberry, R.C. Contrafreeloading in grizzly bears: implications for captive foraging enrichment. Zoo Biol. 2010, 29, 484–502. [CrossRef]

- Neuringer, A.J. Animals Respond for Food in the Presence of Free Food. Science 1969, 166, 399–401. [CrossRef]

- Ogura, T. Contrafreeloading and the value of control over visual stimuli in Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata). Anim. Cogn. 2011, 14, 427–431. [CrossRef]

- Osborne, S.R. The free food (contrafreeloading) phenomenon: A review and analysis. Anim. Learn. Behav. 1977, 5, 221–235. [CrossRef]

- Pyke, G.H.; Pulliam, H.R.; Charnov, E.L. Optimal Foraging: A Selective Review of Theory and Tests. Q. Rev. Biol. 1977, 52, 137–154. [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, V. Caged rhesus macaques voluntarily work for ordinary food. Primates 1994, 35, 95–98. [CrossRef]

- Sasson-Yenor, J.; Powell, D.M. Assessment of contrafreeloading preferences in giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis). Zoo Biol. 2019, 38, 414–423. [CrossRef]

- Stephens, D.W., Krebs, J. R. (1986). Foraging Theory. Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA.

- Tarte, R.D. (1981). Contra-freeloading in humans. Psychological Reports 49, 859–866.

- van Zeeland, Y.R.A.; Schoemaker, N.J.; Lumeij, J.T. Contrafreeloading Indicating the Behavioural Need to Forage in Healthy and Feather Damaging Grey Parrots. Animals 2023, 13, 2635. [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.M.; Wolfe, L.; Davis, T.; Kendall, T.; Richter, B.; Wang, Y.; Bryce, C.; Elkaim, G.H.; Wilmers, C.C. Instantaneous energetics of puma kills reveal advantage of felid sneak attacks. Science 2014, 346, 81–85. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).