1. Introduction

Optimal foraging theory predicts that animals adopt behaviors that maximize their efficiency in finding and selecting food [

1,

2,

3]. In this framework, it is expected that animals will always choose according to the tenets of economic rationality [

4], i.e., to maximize their gains by prioritizing resources that optimize energy intake, both qualitatively and quantitatively [

5,

6,

7]. However, in some contexts, animals may respond to external stimuli with behaviors that violate economic rationality [

8]. For instance, even though animals are expected to always prefer larger quantities of food over smaller ones, this is not systematically observed, and violations of rationality may occur [

8]. In this respect, two decisional biases have been described in the human and non-human animal literature – the selective-value effect and the less-is-better effect [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

The selective-value effect describes the lack of preference for a more abundant option containing both a high-preferred item and a less-preferred one, compared with an option consisting solely of the high-preferred item [

11,

14]. According to Silberberg et al. [

11], this occurs because individuals assign a value only to the high-preferred item within a mixed option. A similar sub-optimal choice behavior is the less-is-better effect [

10,

13,

15,

16], in which individuals rate a single high-preferred item as being better than a larger alternative including both a high-preferred item and a less-preferred one. According to Kralik et al. [

13], this occurs because the preference for an option depends on the overall value of its items, and the addition of a less-preferred item reduces the overall value of the combination. Thus, in both the above-described decisional biases, the individual’s choice is not influenced by the quantity of the items to choose from, but by their perceived overall value, and the presence of a less desirable item can diminish, although to a different extent, the appeal of the more abundant option.

Several studies have explored the occurrence of the selective-value effect and the less-is-better effect in non-human animal species, including great apes [

11,

12,

14], Japanese macaques (

Macaca fuscata; [

11]), Rhesus macaques (

Macaca rhesus; [

13]); dogs (

Canis lupus familiaris; [

17,

18]), pigeons (

Columba livia domestica; [

19]), and tufted capuchin monkeys (S

apajus spp.; [

20,

21]). Silberberg et al. [

11] conducted experiments on three Japanese macaques and one chimpanzee (

Pan troglodytes), finding that the subjects did not show a preference for a mixed option consisting of two food units (a high-preferred food item plus a less-preferred food item) over a single high-preferred food item. However, they did show a preference for the mixed option when the alternative was a single less-preferred food item. Kralik et al. [

13] tested three captive Rhesus macaques, showing that they preferred a single high-preferred food item over a mixed option including the same high-preferred food and a less-preferred food item. Then, they replicated this finding in free-ranging Rhesus macaques, employing a one-trial design. Beran et al. [

12] reported the selective-value effect in two out of four chimpanzees, observing a lack of preference for an option that included both a high-preferred and a less-preferred food compared to an option including only the high-preferred food. This effect extended to all the four tested chimpanzees when the size of the high-preferred food item was carefully equated in both the single and the mixed option. In addition, in Beran et al. [

12] the inter-trial interval (ITI), i.e., the time elapsing between two consecutive trials, modulated the occurrence of the selective-value effect. When the ITI was longer, three out of four chimpanzees preferred the mixed option; instead, when the ITI was shorter, a preference for the single high-preferred food item was observed, suggesting that the presence of the less preferred food in the mixed option assumed a negative value, as it was associated with a delay in completing the trial and thus having again the opportunity to consume the high-preferred food. Sánchez-Amaro et al. [

14] described the occurrence of the selective-value effect in chimpanzees, bonobos (

Pan paniscus), gorillas (

Gorilla gorilla), and Sumatran orangutans (

Pongo abelii), showing that the preference for the mixed option depended on the relative value of the high- and low-preferred food: when the two foods were very differently preferred, the mixed option was chosen to a lower extent than when the two foods were more similarly preferred.

Also non-primate species (birds and dogs) showed the above-described decisional biases when choosing between a single high-preferred food item and a mixed option of the same high-preferred food item and a low-preferred food item. Interestingly, Zentall et al. [

19] observed the less-is-better effect in pigeons, but only when the birds were not food restricted and thus their level of food motivation was relatively low. Two studies observed the less-is-better effect in dogs [

17,

18]. In Pattison & Zentall [

17], in 86.7% of choices dogs displayed a preference for a single piece of cheese over a combination of cheese and carrot. However, when provided choices between two pieces of cheese versus one piece, they consistently preferred the larger quantity, as expected. Chase & George [

18] reported a similar finding also when controlling for potentially confounding factors, as aversion to multiple options of food neophobia.

As for tufted capuchin monkeys, Huntsberry et al. [

20] first reported the occurrence of the selective-value effect in three individuals. They showed indifference between a single high-preferred food item and a combination of the high-preferred item with a less-preferred item, although preferring the mixed option when this was presented against a single low-preferred food item. More recently, we described both the selective-value effect and the less-is-better effect in a few tufted capuchin monkeys out of a larger sample of eight individuals [

21]. We were, however, unable to observe an effect of the length of the intertrial interval, nor we evaluated differences in the occurrence of these decisional biases when employing a low-preferred food compared to a very-low preferred food.

Hence, the present study aims to investigate the occurrence of either the selective-value effect or the less-is-better effect in tufted capuchin monkeys. We examined for the first time how the difference in the preference level between two types of food affect the decision-making process and further explored the role played by the length of the inter-trial interval, while controlling for potential confounding factors (i.e., aversion to heterogeneity, quantitative discrimination failure, food preferences). Capuchin monkeys are particularly well positioned for this investigation because, despite their lineage splitting from humans about 35 million years ago, they share several behavioral and cognitive traits with our species [

22], including several decisional biases (e.g., framing effect [

23]; endowment effect [

24]; decoy effect [

25,

26,

27]. In line with the literature, capuchins were expected to prefer the mixed option, behaving rationally, when the qualitative difference between the two food items was small. Conversely, they were expected to show either indifference between options (selective-value effect) or a preference for the single-item option (less-is-better effect) when the mixed option contained a high-preferred food and a very-low preferred one [

14]. Additionally, capuchins were expected to choose more often the mixed option when the ITI was longer [

12], allowing them to consume the selected food more slowly.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

We tested 12 captive tufted capuchin monkeys, six males and six females (average age: 24 years, min 12, max 36 years old), belonging to four different social groups (see

Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials for further details), hosted at the Primate Center of the Istituto di Scienze e Tecnologie della Cognizione (ISTC-CNR) in Rome.

Capuchins were housed in enriched indoor (25.4 m3) and outdoor areas (53.2 m3 - 127.4 m3, depending on the group size), and individually tested in experimental boxes measuring 1 m3 with free access to one of the two indoor areas, with water available ad libitum. Animals were not food deprived for testing.

The experimental sessions were performed between 9:15 a.m. and 2:30 p.m., before the daily meal. The daily meal consists of a wide variety of fruits, vegetables, and primate monkey chow. Individual subjects were tested on a voluntary basis and were separated from the rest of the group by offering small amounts of food (peanut seeds) as reinforcement. The study was carried out in accordance with the European normative regulating the use of primates in experimental research (Directive 2010/63/EU; authorization n. 721/2024-PR to Elsa Addessi) and the guidelines of the OPBA (Animal Welfare Board) operating at the ISTC-CNR Primate Center.

2.2. Experimental Apparatus and Procedure

In each experimental phase, animals were offered binary choices on a transparent Plexiglas tray (27 x 40 cm), with a central divider of the same material, and two handles on each side. Food items were placed 5.2 cm from the top edge of the apparatus, at the same distance (8 cm) from the tray divider.

The choice options were placed on the tray out of the subject’s sight. The tray was positioned on a black trolley, placed between the experimenter and the subject’s experimental box. In each trial, the tray was slid towards the subject, when it was in front of the trolley. The tray remained in place for up to 15 seconds, until the subject chose one of the two alternatives. The experimenter avoided the eye contact with the subject in order not to bias its choice, nor looked at any of the two options. Each subject made its choice by inserting the hand through the wire mesh and picking up one food option. Once the choice was made, the experimenter immediately removed the tray to prevent the subject from picking up the alternative food option. Each subject's choices were scored during the experimental sessions, which were also videotaped. In the Food preference phase, there was a 10-s intertrial interval (ITI); in the Experimental phase there was either a 10-s or a 30-s ITI, according to the condition.

2.3. Food Preference Phase

First of all, we selected two pairs of differently preferred food items: (i) H vs. L+ pair, including a high-preferred food (H) and a low-preferred food (L+), such that H was selected over L+ in 65-75% of the trials for two consecutive 20-trial sessions; (ii) H vs. L- pair, including a high-preferred food (H) and a very low-preferred food (L-), such that H was selected over L- in 95-100% of the trials for two consecutive 20-trial sessions. Immediately after each H vs. L- session, to assess whether subjects would consume the very low-preferred food L-, despite not preferring it, we carried out a palatability test by offering for 10 trials the L- food (one item in each trial). The weight of each item was carefully standardized by using a precision scale (Gibertini EUROPE 1700, dd= 0,01 g, SER. NO82998): Monkey chow 0.02 g; Rice Krispies 0.01 g; Sunflower seed 0.03 g; Cheerios 0.10 g; Apricot 0.30 g; Raisin 0.20 g; Pineapple 0.30 g; Plum 0.30 g; Pumpkin seed 0.05 g.

Table S2 reports all the individual food preferences.

2.4. Experimental Phase

2.4.1. Experimental Conditions

To test whether the relative value of the high- vs. less-preferred food and/or the length of the ITI modulate the occurrence of the selective-value effect, subjects were tested in 4 conditions: (i) H vs. HL+, with 10-s ITI (“HL+ 10”); (ii) H vs. HL-, with 10-s ITI (“HL- 10”); (iii) H vs. HL+, with 30-s ITI (“HL+ 30”); (iv) H vs. HL-, with 30-s ITI (“HL- 30”).

We used an ABAB-type experimental design. Subjects were first tested in the conditions “HL+ 10” and “HL- 10”, by counterbalancing their order of presentation across subjects, and subsequently in the conditions “HL+ 30” and “HL- 30”, again counterbalancing their order of presentation across subjects. In each condition, subjects received five sessions. Then, the entire experiment was replicated a second time (see

Table S3). Thus, each subject received a total of 10 sessions in each condition.

2.4.2. Experimental Sessions

Each experimental session consisted of 24 trials, which included (1) six experimental trials (H vs. HL+/-, according to the condition), (2) six control trials for heterogeneity aversion (L+/- vs. HL+/-, according to the condition); (3) three control trials for quantitative discrimination with the high-preferred food item H (H vs. HH) and three control trials for quantitative discrimination with the low-preferred food item L (L+ vs. L+L+ or L- vs. L-L-, according to the condition), and (4) six control trials for food preference maintenance (H vs. L+ or H vs. L-, according to the condition).

In the heterogeneity aversion trials, we controlled whether capuchins showed an aversion towards choosing the mixed option, i.e., the option consisting of two different food items, regardless of food preference. In the quantitative discrimination trials, we controlled whether capuchins correctly discriminated between different food quantities. In the food preference maintenance trials, we controlled whether capuchins maintained their food preferences over time.

In each trial type, the position of the two food options on the tray (right/left) was pseudo-randomized within each experimental session. Before the onset of each experimental session, the subject was offered and allowed to consume the two food types (one item each) subsequently presented in the experimental session.

2.5. Data Analysis

For each trial type (experimental, heterogeneity aversion, quantitative discrimination, food preference maintenance), we employed the single-sample Wilcoxon signed-ranks test, both at the population and at the individual level, to assess whether capuchins significantly preferred either option above the chance level.

Then, for each trial type, we implemented random-effects logistic regression models. As dependent variables, in experimental and heterogeneity control trials we used the choices for the mixed option (HL+/-), in quantitative discrimination trials we used the choices for the more numerous option (HH, L+L+ or L-L-), and in food preference maintenance control trials we used the choices for the high-preferred food option (H). Sex, age, block (i.e., first or second part of the experiment, see

Table S3), type of less-preferred food (L+ or L-) and ITI (10 s or 30 s) were included as factors. Interactions were analyzed by using the Wald test, removing not significant interactions from the model and then repeating the analysis. The significance level was established at p< 0.05. We performed this analysis by means of the software Stata 14.0.

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Trials (HL+/- vs. H)

Capuchins significantly preferred the mixed option (HL+ or HL-, according to the condition) above chance level in all experimental conditions (see

Table 1). However, at the individual level, some subjects showed a lack of preference for either option, thus showing the selective-value effect. In the condition “HL+ 10”, 1 out of 12 subjects (Paprika) showed the selective-value effect; in the condition “HL- 10”, 8 subjects out of 12 showed the selective-value effect (Cognac, Gal, Paprika, Robinia, Robiola, Robot, Saroma, Vispo); in the condition “HL+ 30”, no subject showed the selective-value effect; in the condition “HL- 30”, 5 out of 12 subjects showed the selective-value effect (Robinia, Robiola, Robot, Saroma, Vispo) (

Table S4).

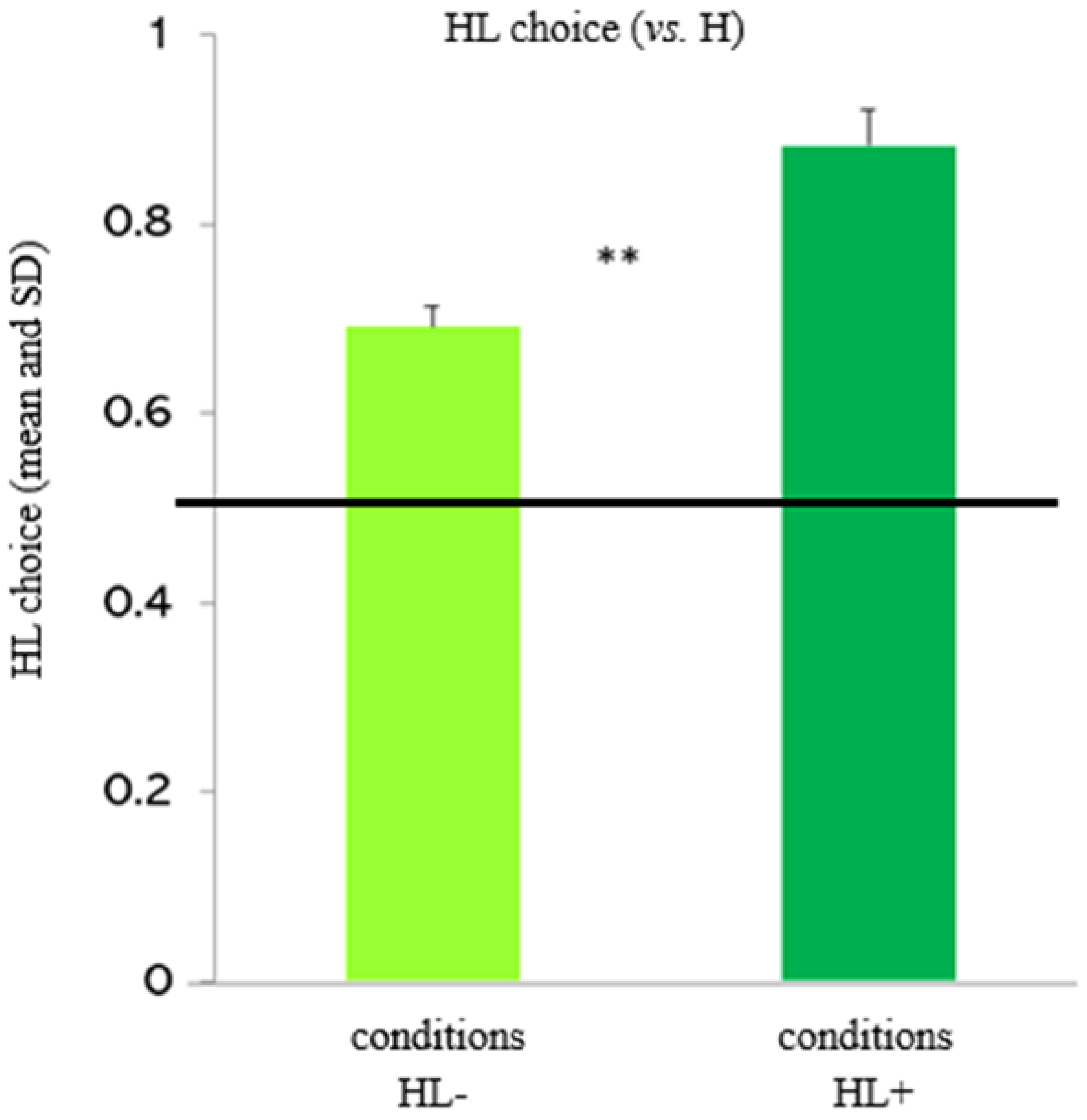

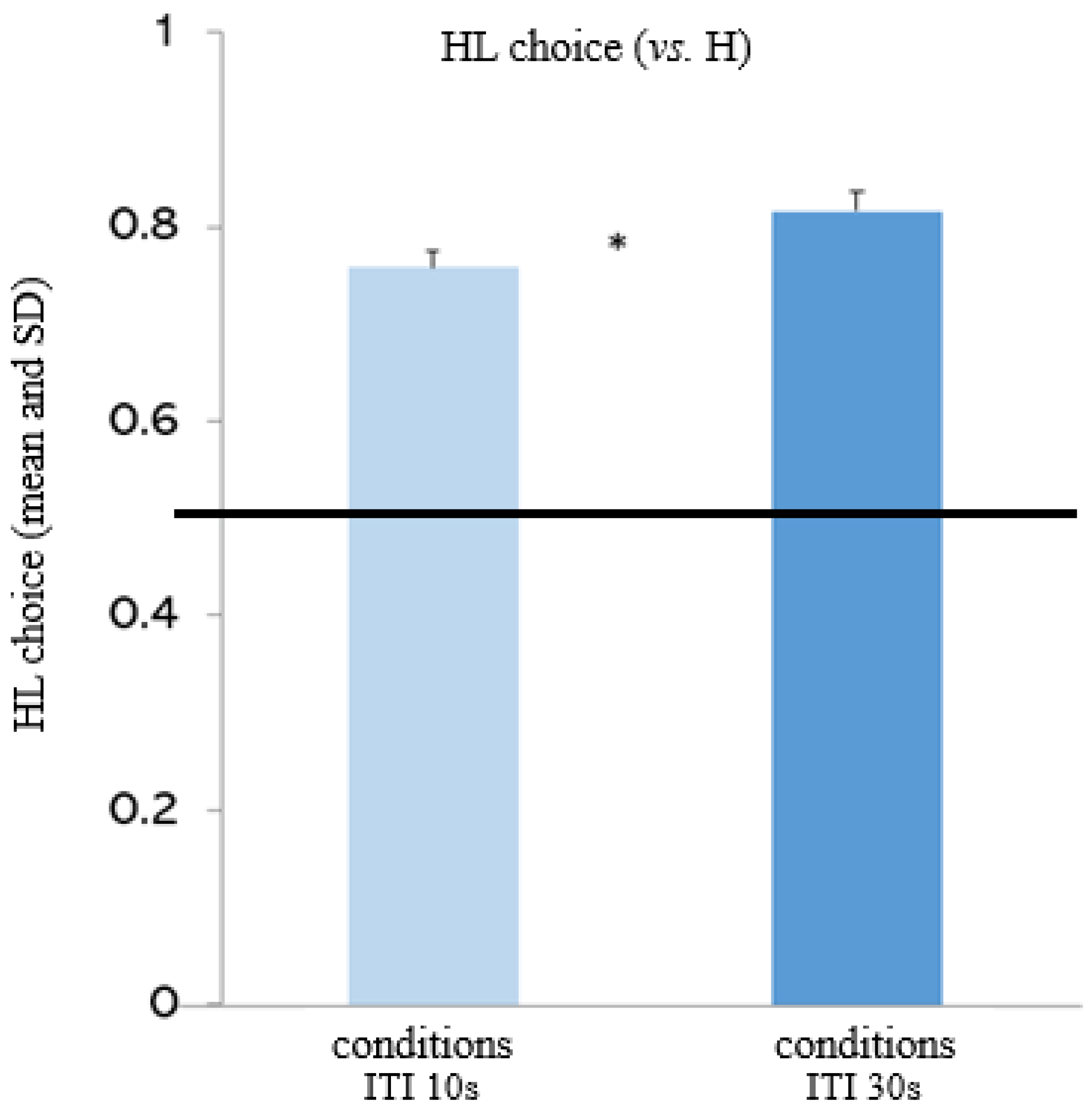

The random-effects logistic regression model showed no significant interactions (condition x ITI: χ

22 = 0.60, p = 0.438; condition x block: χ

22 = 0.31, p = 0.580), but significant main effects of condition and ITI. Capuchins chose the mixed option significantly more when it included the low-preferred food (L+) (i.e., in the conditions “HL+ 10” and “HL+ 30”) than when it included the very-low preferred food (L-) (i.e., in the conditions “HL- 10” and “HL- 30”; see

Figure 1) (coeff= -1.273; z= -3.41; p= 0.001). Moreover, capuchins chose the mixed option significantly more when the ITI was longer (i.e., in the conditions “HL+ 30” and “HL- 30”) than when the ITI was shorter (i.e., in the conditions “HL+ 10” and “HL- 10”; see

Figure 2) (coeff= 0.379; z= 2.50; p= 0.012). There were no other significant main effects.

3.2. Control Trials for Heterogeneity Aversion (HL+ vs. L+; HL- vs. L-)

Capuchins significantly preferred the mixed option above chance level in all experimental conditions (see

Table 2). At the individual level, all subjects (but Gal in the condition “HL+ 10”) preferred the mixed option over the single option (

Table S5).

The random-effects logistic regression model showed no significant interactions (condition x ITI: χ22 = 0.02, p = 0.882; condition x block: χ22 = 3.24, p = 0.072), but a significant main effect of condition. Capuchins chose the mixed option significantly more when it included the very low-preferred food (L-) (i.e., in the conditions “HL- 10” - and “HL- 30”) than when it included the low preferred food (L+) (i.e., in the conditions “HL+ 10” - and “HL+ 30”) (coeff. = 2.296, z= 4.63, p< 0.001). There were no other significant main effects.

3.3. Control Trials for Quantitative Discrimination (HH vs. H; L+L+ vs. L+; L- L- vs. L-)

Overall, capuchins significantly preferred the larger option (HH/L+L+/L-L-) over the suboptimal alternative (H/L+/L-) in all quantitative discrimination trial types (see

Table 3). Individual results confirmed the above findings (

Table S6 and S7).

For the HH vs. H trial type, the random-effects logistic regression model showed no significant interactions (condition x ITI: χ22 = 0.05, p = 0.826; condition x block: χ22 = 0.28, p = 0.599), but a significant main effect of condition. Capuchins preferred the larger option (HH) significantly more in the conditions “HL- 10” and “HL- 30” (coeff= 1.086; z= 3.43; p= 0.001). For the LL vs. L trial type, there was a significant interaction between food type (L+ or L-) and ITI (10 s or 30 s): χ21 = 10.93, p < 0.001. Post-hoc analysis showed that capuchins preferred the larger option (LL) significantly more in the condition “HL+ 30” than in the condition “HL-30” (coeff= 1.201; z= 2.64; p= 0.008), but there was no significant difference between the conditions “HL+ 10” and “HL-10” (coeff= -0.065; z= -0.12; p= 0.907). There were no other significant interactions or main effects.

3.4. Control Trials for Food Preference Maintenance (H vs. L+; H vs. L-)

In the conditions “HL+ 10” and “HL+ 30”, capuchins did not significantly prefer the single unit of the high-preferred food (H) above chance level, whereas they did so in the conditions “HL- 10” and “HL- 30” (see

Table 4). At the individual level, many subjects showed a lack of preference for either option or had reversed their preferences. In the condition “HL+ 10”, 3 out of 12 subjects were indifferent between options (Robiola, Sandokan, Saroma) and 4 subjects had reversed their food preferences (Gal, Roberta, Rucola, Vispo). Similarly, in the condition “HL+ 30”, 7 out of 12 subjects were indifferent between the two options (Gal, Paprica, Robinia, Robiola, Rucola, Saroma, Totò) and 2 subjects had reversed their preferences (Roberta and Vispo). Finally, in the condition “HL- 30” one subject (Totò) was indifferent between options (

Table S8).

The random-effects logistic regression model showed a three-way significant interaction between food type (L+ or L-), ITI (10 s or 30 s) and block (first part of the experiment vs. second part of the experiment): χ22 = 15.16, p < 0.001). Post-hoc analyses showed that, in H vs. L+ trials capuchins chose the H food over the L+ food significantly more in the first part than in the second part of the experiment (coeff= 0.410; z= 3.30; p< 0.001), regardless of ITI (coeff= 0.103; z= 0.84; p = 0.404), whereas in H vs. L- trials capuchins chose the H food over the L- food significantly more in the second part than in the first part of the experiment (coeff= 0.740; z= 3.01; p = 0.003), and significantly more in the trials with 10-s ITI than with 30-s ITI (coeff= 0.471; z= 1.97; p = 0.049).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we aimed to test whether tufted capuchin monkeys presented with choices between a mixed option (one high-preferred food item plus a less-preferred food item) and a single option (one high-preferred food item) showed either the selective-value effect or the less-is-better effect. Additionally, we aimed to investigate whether the relative value of the high- vs. less-preferred food included in the mixed option (low- or very-low preferred) and the length of the inter-trial interval (10 s or 30 s) modulated their choices. As Sánchez-Amaro et al. [

14] and Chase & George [

18], we also included a series of control trials for heterogeneity aversion, quantitative discrimination, and food preference maintenance.

Overall, capuchins performed rational choices, as during the experimental trials they significantly chose the mixed option above chance level. However, both the relative value of the high- vs. less-preferred food included in the mixed option and the length of the intertrial interval independently modulated their choices. Regardless of the ITI, the preference for the mixed option was stronger when the high- and less-preferred food items were more similarly favored (i.e., in the conditions “HL+”) than when the two food items were rated as more qualitatively different by capuchins (i.e., in the conditions “HL-”), as shown by Sánchez-Amaro et al. [

14] in great apes. Moreover, regardless of the relative difference between food items, the preference for the mixed option was stronger when the ITI was longer than when it was shorter (i.e., in the conditions with 30-s ITI), as reported by Beran et al. [

12] in chimpanzees.

From the individual performances, it emerged that many capuchins showed the selective-value effect, i.e., they were indifferent between the mixed option and the single option, in the conditions involving the two very differently preferred foods, but to a higher extent when the ITI was 10 s than when the ITI was 30 s. Indeed, out of 12 capuchins, eight showed the selective-value effect in the “HL-10” condition, and five in the “HL-30” condition, whereas only one capuchin showed the selective-value effect in the “HL+10” condition and none in the “HL+30” condition. This is a higher rate than that reported in Quintiero et al. [

21], in which – out of 8 capuchins -- only two showed the selective-value effect and one the less-is-better effect, probably due to the overall shorter duration of the study (only 40 trials vs. the 240 experimental trials carried out in the present investigation).

As Sánchez-Amaro et al. [

14] suggested, when the difference in the relative value between foods is low, individuals may perceive the choice between the mixed and the single option as a quantitative discrimination, focusing on the larger amount of food and disregarding the qualitative difference between foods. However, when the difference in the relative value between the foods included in the mixed option differs more substantially, the less-preferred food might lose its value [

11], leading the individuals to choose randomly between options.

This interpretation aligns with the results of the preference maintenance control trials (H vs. L+/-), which confirmed that capuchins’ relative preference for the food pairs H vs. L+ and H vs. L- was different. Overall, regardless of ITI, in the conditions “HL+ 10” and “HL+ 30”, in which the difference in the relative value between foods was small (i.e., the L food was preferred over the H food in 65–75% of the trials during the preliminary food preference phase), capuchins did not significantly choose the high-preferred food above chance level and their preference for the L+ food decreased over time. In contrast, in the conditions “HL- 10” and “HL- 30”, in which the difference in the relative value between foods was higher (i.e., the L food was preferred over the H food in 95–100% of the trials during the preliminary food preference phase), capuchins significantly chose the high-preferred food above chance level and their preference for the L- food increased over time. Accordingly, at the individual level, in the conditions “HL+” many subjects showed a lack of preference for either option or had reversed their preferences: out of 12 capuchins, in the condition “HL+ 10” three were indifferent between options and four had reversed their preferences, and in the condition “HL+ 30” seven capuchins were indifferent between options and two had reversed their preferences. Instead, in the condition “HL-10” all capuchins continued to prefer the H food, and in the condition “HL- 30” only one subject was indifferent between options.

The modulation of capuchins’ choices for the mixed option by the length of the intertrial interval, according to which capuchins preferentially selected the mixed option when the ITI was longer, suggests that capuchins prefer to opt for the mixed food option (HL), over the single unit of the high-preferred food (H), when they have more time available to consume the more abundant option before the subsequent trial, and thus another opportunity to consume the high-preferred food. Instead, they preferentially select the single unit of the high-preferred food when the intertrial interval is shorter, not to excessively delay the occurrence of the next trial [

12]. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that in the wild environmental pressures, such as predation or competition, may reduce the time available for foraging and drive animals to prioritize specific, high-value resources [

13,

28].

However, a qualitative comparison between the regression coefficients shows that the relative value of the high- vs. less-preferred food was a slightly stronger modulator of capuchins’ choices for the mixed over the single option than the length of the intertrial interval, and the analysis of each capuchin’s choices, showing that eight capuchins showed the selective value-effect in the condition “HL-10” but only five in the condition “HL-30” (as reported above), corroborates this finding. This is in agreement with previous findings showing that the effect of the length of the intertrial interval on the occurrence of the selective-value effect is labile, as it is observed in some studies [i.e., 12] but not in others [i.e., 14,21].

We can exclude that the selective-value effect shown by several capuchins was due to difficulties in quantitative discrimination or heterogeneity aversion. In control trials for quantitative discrimination (HH vs. H and LL+/- vs. L+/-) capuchins chose the larger option significantly above chance, and in control trials for heterogeneity aversion (HL+/- vs. L+/-) capuchins significantly preferred the mixed option over the single less-preferred food. However, in “HL+” conditions capuchins chose the HH option to a lower extent than in “HL-” conditions, probably to balance their higher selection of the LL option, especially in the condition “HL+30” compared to the condition “HL-30”. Likewise, in heterogeneity trials of “HL+” conditions capuchins chose the mixed HL option less often than in “HL-” conditions, probably because their choices were driven towards the single unit of the low-preferred L+ food, which was qualitatively rather similar to the high-preferred food.

Overall, our findings indicate that in experimental trials capuchin monkeys made rational choices, generally preferring the option yielding a larger food amount (i.e., the mixed option) rather than the single high-preferred food unit. However, as expected, the likelihood of choosing the mixed option was significantly lower when the two foods were very differently preferred and when the intertrial interval was shorter. In these conditions, many capuchins did not make rational choices and preferred the single high-preferred food unit rather than the mixed option including both the high-preferred food and a very-low preferred food, thus showing the selective-value effect, as other non-human animals.

5. Conclusions

Understanding decisional biases in light of economic axioms can be misleading, and irrational behaviors should be analyzed through a biological lens. Indeed, natural selection does not operate under principles of coherence, unlike the behavioral models proposed by neoclassical economic theory. Whereas some animal choices may appear irrational, they can be biologically rational as adaptive responses aimed at optimizing individual fitness [

29,

30,

31]. In an ecological context, an animal may not strive for efficiency in energy intake relative to time but may forage based on specific nutrient needs [

5], and individuals may vary their provisioning strategies in relation to the homeostasis of their metabolic state. For instance, Izar et al. [

32] observed, in natural populations of bearded capuchins (

Sapajus libidinosus), a fixed and constant daily protein intake pattern (protein prioritization), also demonstrated in other primate species, including humans [

33,

34,

35]. According to this model, variations in protein intake can influence the consumption of other macronutrients, such as fats and carbohydrates, whose quantities may vary daily. It is possible that capuchins may prioritize certain foods while avoiding others without these decisions being suboptimal, not only based on the physiological feedback generated by food resources [

28,

35], but also on the individual preferences and sensory cues, which precede the physiological feedback [

36].

In conclusion, this study sheds further light on the factors affecting the selective-value effect, extending the results previously obtained in capuchin monkeys [

20,

21] and expanding the range of decisional biases sharing common evolutionary roots across the primate order.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1: Table S1. Subjects’ sex, age, species and social group; Table S2. Food preference phase; Table S3. Order of presentation of experimental conditions across subjects; Table S4. Experimental trials (HL+/- vs. H); Table S5. Control trials for heterogeneity (HL+/- vs. L+/-); Table S6. Control trials for quantitative discrimination (HH vs. H); Table S7. Control trials for quantitative discrimination (LL+/- vs. L+/-); Table S8. Control trials for food preference maintenance (H vs. L+; H vs. L-).

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, A.D., S.G., E.A.; methodology, A.D., S.G., E.A.; formal analysis, A.D., E.A., investigation, A.D., S.G.; data curation, A.D., S.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.; writing—review and editing, G.S., E.A.; visualization, A.D.; supervision, G.S., E.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding. The Primate Centre was funded by CNR.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was carried out in accordance with the European normative regulating the use of primates in experimental research and the guidelines of the OPBA (Animal Welfare Board) operating at the ISTC-CNR Primate Center. The study protocol was approved by the Italian Ministry of Health (Directive 2010/63/EU; authorization n. 721/2024-PR to Elsa Addessi).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Roma Capitale-Museo Civico di Zoologia and the Fondazione Bioparco for hosting the ISTC-CNR Unit of Cognitive Primatology and Primate Centre, the CNR for funding the capuchin colony, and Arianna Manciocco, Marta Canet and Flavia Pipitone for their expert care of the monkeys.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Stephens, D.W.; Krebs, J.R. Foraging Theory; Princeton University Press: 2019.

- DeAngelis, D.L.; Mooij, W.M. Individual-based modeling of ecological and evolutionary processes. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2005, 36, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyke, G.H.; Stephens, D.W. Optimal foraging theory: Application and inspiration in human endeavors outside biology. In Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior; Choe, J.C., Ed.; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J.; Morgenstern, O. Theory of games and economic behaviour; Princeton University Press, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Emlen, M.J. The role of time and energy in food preference. Am. Nat. 1966, 100, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, R.H.; Pianka, E.R. On optimal use of a patchy environment. Am. Nat. 1966, 100, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoener, T.W. Theory of feeding strategies. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 1971, 1971 2, 369–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnov, E.L. Optimal foraging, the marginal value theorem. Theor. Popul. Biol. 1976, 9, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, L.R.; Rosati, A.G. The evolutionary roots of human decision making. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015, 66, 321–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsee, C.K. Less is better: When low-value options are valued more highly than high-value options. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 1998, 11, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberberg, A.; Widholm, J.J.; Bresler, D.; Fujita, K.; Anderson, J.R. Natural choice in nonhuman primates. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Process 1998, 24, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beran, M.J.; Ratliff, C.L.; Evans, T.A. Natural choice in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes): Perceptual and temporal effects on selective value. Learn. Motiv. 2009, 40, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kralik, J.D.; Xu, E.R.; Knight, E.J.; Khan, S.A.; Levine, W.J. When less is more: Evolutionary origins of the affect heuristic. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Amaro, A.; Peretó, M.; Call, J. Differences in between-reinforcer value modulate the selective-value effect in great apes (Pan troglodytes, P. paniscus, Gorilla gorilla, Pongo abelii). J. Comp. Psychol. 2016, 130, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrish, A.E.; Sandgren, E.E. The less-is-better effect: A developmental perspective. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2023, 30, 2363–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vonasch, A.J.; Hung, W.Y.; Leung, W.Y.; Nguyen, A.T.B.; Chan, S.; Cheng, B.L.; Feldman, G. “Less is better” in separate evaluations versus “more is better” in joint evaluations: Mostly successful close replication and extension of Hsee (1998). Collabra Psychol. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattison, K.F.; Zentall, T.R. Suboptimal choice by dogs: When less is better than more. Anim. Cogn. 2014, 17, 1019–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chase, R.J.; George, D.N. More evidence that less is better: Sub-optimal choice in dogs. Learn. Behav. 2018, 46, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zentall, T.R.; Laude, J.R.; Case, J.P.; Daniels, C.W. Less means more for pigeons but not always. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2014, 21, 1623–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntsberry, M.E.; Roma, P.G.; Christensen, C.J.; Ruggiero, A.M.; Suomi, S.J. Token exchange and the selective-value effect in capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella). In Thirtieth Annual Meeting of the American Society of Primatologists, Wake Forest University School of Medicine Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA, 20–23 June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Quintiero, E.; Gastaldi, S.; De Petrillo, F.; Addessi, E.; Bourgeois-Gironde, S. Quantity–quality trade-off in the acquisition of token preference by capuchin monkeys (Sapajus spp.). Phil Trans. R. Soc. B 2021, 376, 20190662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fragaszy, D.M.; Visalberghi, E.; Fedigan, L.M. The complete capuchin: The biology of the genus Cebus; Cambridge University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.K.; Lakshminarayanan, V.; Santos, L.R. How basic are behavioral biases? Evidence from capuchin monkey trading behavior. J. Polit. Econ. 2006, 114, 517–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshminarayanan, V.R.; Chen, M.K.; Santos, L.R. The evolution of decision-making under risk: Framing effects in monkey risk preferences. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 47, 689–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watzek, J.; Brosnan, S. Capuchin monkeys (Sapajus [Cebus] apella) are more susceptible to contrast than to decoy and social context effects (2020/Unpublished).

- Marini, M.; Boschetti, C.; Gastaldi, S.; Addessi, E.; Paglieri, F. Context-effect bias in capuchin monkeys (Sapajus spp.): Exploring decoy influences in a value-based food choice task. Anim. Cogn. 2023, 26, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marini, M.; Colaiuda, E.; Gastaldi, S.; Addessi, E.; Paglieri, F. Available and unavailable decoys in capuchin monkeys (Sapajus spp.) decision-making. Anim. Cogn. 2024, 27, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raubenheimer, D.; Simpson, S.J. Protein leverage: Theoretical foundations and ten points of clarification. Obesity 2019, 27, 1225–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacelnik, A. Meanings of rationality. In Rational Animals? Hurley, S.E., Nudds, M.E., Eds.; Oxford University Press, 2006; pp. 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, P.M.; Gigerenzer, G. Environments that make us smart: Ecological rationality. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 16, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huneman, P.; Martens, J. The behavioural ecology of irrational behaviours. Hist. Philos. Life Sci. 2017, 39, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izar, P.; Peternelli-dos-Santos, L.; Rothman, J.M.; Raubenheimer, D.; Presotto, A.; Gort, G.; Visalberghi, E.M.; Fragaszy, D.M. Stone tools improve diet quality in wild monkeys. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, 4088–4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felton, A.M.; Felton, A.; Raubenheimer, D.; Simpson, S.J.; Foley, W.J.; Wood, J.T.; Wallis, I.R.; Lindenmayer, D.B. Protein content of diets dictates the daily energy intake of a free-ranging primate. Behav. Ecol. 2009, 20, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.A.; Raubenheimer, D.; Rothman, J.M.; Clarke, D.; Swedell, L. 30 days in the life: Daily nutrient balancing in a wild chacma baboon. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raubenheimer, D.; Jones, S.A. Nutritional imbalance in an extreme generalist omnivore: Tolerance and recovery through complementary food selection. Anim. Behav. 2006, 71, 1253–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visalberghi, E.; Sabbatini, G.; Stammati, M.; Addessi, E. Preferences towards novel foods in Cebus apella: The role of nutrients and social influences. Physiol. Behav. 2003, 80, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).