1. Introduction

Classical economic theory posits rational behavior

as its guiding principle, underpinning models of market equilibrium and

resource allocation. Accordingly, individuals are endowed with stable,

internally consistent preferences that yield coherent and predictable choices. Foundational axioms,

such as transitivity, completeness, and independence, serve as the keystones of

this theory, underpinning theories from expected utility to revealed

preferences. Yet an expanding body of empirical research challenges the

universality of these assumptions. Evidence from behavioral economics and

psychology demonstrates that real-life decision-making often deviates from

these idealized models. Such deviations may arise not only from familiar

cognitive biases, but also, in some cases, from underlying cognitive

impairments or mental health conditions that significantly influence the

processes by which individuals evaluate options and make decisions (Bayer &

Osher, 2018; Bayer et al., 2018; Bayer et al., 2019; Bayer & Shtudiner,

2023; Solomon & Bayer, 2023).

One of the most fundamental axioms is transitivity:

if a person prefers A over B and B over C, they should logically prefer A over

C. This principle lies at the heart of rational choice theory (Simon, 1955).

Nonetheless, research shows that even this core assumption is systematically

violated, particularly among individuals exhibiting perfectionistic tendencies,

who often engage in recursive deliberation and cyclical comparisons that

disrupt coherent preference structures (Frost & Steketee, 1997; Schwartz et

al., 2002). Empirical

research has demonstrated that individuals with perfectionist or

obsessive-compulsive tendencies frequently experience significant difficulties

in decision-making, even when the available options are objectively comparable

and acceptable (Rasmussen and Eisen, 1992; Reed, 1985; Tolin et al., 2003).

These individuals often engage in extensive, time-consuming evaluations of

alternatives, struggle to commit to a single choice, and commonly experience post-decision

regret or persistent dissatisfaction (Loomes & Sugden, 1982; Pushkarskaya

et al., 2015). Such behaviors are not fully accounted for by classical models

of bounded rationality, which emphasize cognitive limitations such as

restricted attention, memory, or information-processing capacity (Rubinstein,

1998). Nor can these patterns be attributed solely to randomness or

inconsistency in behavior. Rather, they seem to reflect a structured,

emotionally charged evaluative process in which the individual systematically

prioritizes the avoidance of perceived flaws over the maximization of expected

value or utility. This tendency is particularly pronounced under conditions of

uncertainty, where intolerance of ambiguity and fear of making the “wrong” decision

further exacerbate indecision and cyclical comparison (Tolin et al., 2003).

In particular, individuals with high levels of

perfectionism, often correlated with obsessive-compulsive personality traits,

seem to engage in what might be called deficiency-sensitive comparison.

Therefore, when faced with multiple alternatives, they evaluate each one

primarily in terms of what it lacks relative to the others, rather than what it

positively offers. This framing creates a dynamic in which no option is ever

satisfactory, as each is outdone by another on at least one salient dimension.

The result is a cycle of preferences: one option is preferred to the second,

the second to the third, but the third, paradoxically, to the first. Such

intransitive structures are theoretically inconsistent with rational choice and

practically debilitating, leading to decision paralysis, emotional distress,

and inefficient economic outcomes (Iyengar & Lepper, 2000).

This paper proposes a theoretical model to explain

this phenomenon. We modify standard utility theory by incorporating a

deficiency-penalized utility function that accounts for the psychological cost

of perceived imperfection. In this framework, the utility of an option is not

judged in isolation but is reduced by the extent to which it appears inferior

to other available alternatives. The model generates non-transitive preference

cycles systematically and predictably, reflecting the affective structure of perfectionist

evaluation. It captures a wide range of behaviors observed in clinical

contexts, consumer environments, and experimental settings, and opens new

avenues for modeling emotionally bounded rationality.

By focusing on the interplay between emotion and

evaluation, this approach expands the theoretical foundations of decision

theory. It bridges the gap between formal economic modeling and psychological

insights into the nature of perfectionism, regret, and intolerance of

uncertainty. More broadly, it suggests that in some contexts, emotionally

structured irrationality is not a deviation from preference logic but a

reflection of a different kind of internal coherence, one that prioritizes flaw

minimization over utility maximization. This reorientation has far-reaching

implications for welfare economics, consumer protection, mental health policy,

and the design of decision environments in both public and private spheres.

In the sections that follow, we develop the formal

structure of the model, illustrate its behavioral consequences through a

concrete example, and explore its implications for economic theory, mental

health economics, and artificial intelligence. Our aim is not merely to

challenge the axiom of transitivity, but to deepen our understanding of the

psychological mechanisms that underlie real-world decision-making, particularly

for individuals whose pursuit of perfection becomes a source of persistent

inefficiency and distress.

2. Cognitive Mechanisms of Perfectionism and Decision Paralysis

Perfectionism, especially in its maladaptive form,

significantly impacts decision-making processes. Individuals with

perfectionistic tendencies often strive for flawlessness and set excessively

high-performance standards, which can lead to over-analysis and indecision.

This relentless pursuit of the "perfect" choice can result in a

phenomenon known as decision paralysis, where the fear of making an imperfect

decision leads to inaction.

Research indicates that perfectionists are more

prone to experiencing regret and dissatisfaction with their choices, even when

outcomes are objectively positive. This is partly due to their tendency to

engage in counterfactual thinking, constantly imagining better alternatives

that could have been chosen. Such cognitive patterns can create a cycle of

non-transitive preferences, where the individual prefers option A over B, B

over C, but then C over A, leading to inconsistent and cyclical decision-making.

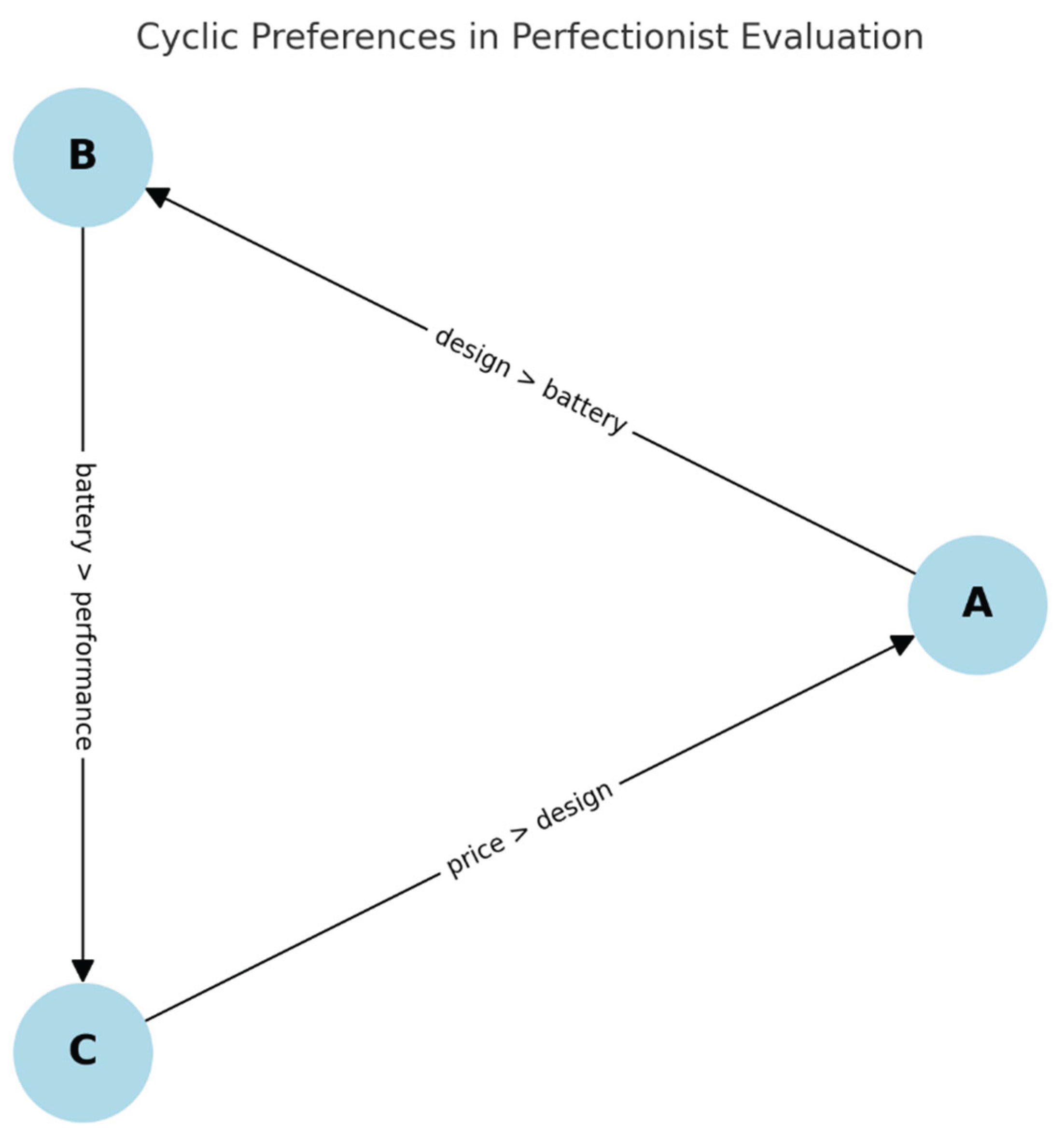

For example, consider a consumer choosing a new

laptop:

Option A: Features a sleek design and

high-resolution display, but has limited battery life.

Option B: Offers extended battery life and

portability but comes with a lower-resolution display.

Option C: Provides a high-performance

processor and ample storage, but is heavier and more expensive.

A perfectionist might evaluate these options as

follows:

A ≻

B: Prioritizing design and display quality over battery life.

B ≻

C: Valuing portability and battery life over performance and storage.

C ≻

A: Emphasizing performance and storage capacity over design and display

quality.

This creates a preference cycle: A ≻ B ≻ C ≻

A. At each step, the focus shifts to what the option is missing, not

what it offers. The perceived deficiencies dominate the decision process,

leading to cyclical preferences and decision paralysis. This kind of

non-transitive structure is common among “maximizers”, individuals who strive

to make the absolute best choice in every decision (Parker et al, 2007;

Schwartz et al., 2002; Iyengar et al., 2006).

3. Theoretical Framework: Deficiency-Penalized Utility

3.1. Overview of the Model

In this section, we formalize the mechanism by

which perfectionist tendencies can lead to cyclical, non-transitive

preferences. At the core of our model is the idea that such individuals do not

assess alternatives in isolation but instead focus on the deficiencies of each

option in comparison to the others. This comparative, emotionally weighted

evaluation introduces systematic distortions into the preference structure,

even when the underlying utility function is well-defined and consistent.

3.2. Mathematical Formulation

Let X denote a finite set of options. Each

alternative x∈ X is

characterized by a vector of measurable attributes a

1(x), a

2(x),…, a

n(x),

where each a

i(x) reflects the performance of option x on attribute i. In

Equation (1), we

define a standard value function:

where wi≥0 is the weight the agent

assigns to attribute i. This function represents the agent’s baseline

evaluation of an option without comparative penalties.

To capture perfectionist tendencies, in

Equation

(2), we introduce a

deficiency penalty that evaluates how much worse

option x performs relative to another option y. Formally:

where γ>0 is a parameter measuring the agent's

sensitivity to perceived shortcomings. The

perceived utility of option x

when compared to option y is then given by

Equation (3):

Option x is preferred to option y if U(x∣ y) > U(y∣ x).

3.3. Asymmetry in Deficiency Evaluation and Implications for Transitivity

One of the core assumptions of our model is that

the deficiency penalty δ(x∣ y) is not symmetric;

namely, δ(x∣ y)≠δ(y∣ x). This reflects the tendency

of individuals, particularly those with perfectionist traits, to

disproportionately attend to what an option lacks compared to others, rather

than focusing on its intrinsic value. In practical terms, comparing option x to y may highlight a

different set of flaws than comparing y to x, resulting in direction-dependent

evaluations that disrupt transitivity.

To capture this, we expand the deficiency penalty

function as follows (

Equation 4):

where:

si(y,x)

is the attentional salience function, representing

the degree of attention attribute

i

receives when comparing option

x

to option

y

. This function captures the

psychological phenomenon that certain attributes become more prominent

depending on the direction of comparison.

wi(y→x)

denotes the dynamic weight assigned to attribute

i

when comparing from

y

to

x

, which may differ from the

baseline weight

wi

due to emotional factors.

ai(x)

and

ai(y)

represent the levels of attribute

i

in options

x

and

y

, respectively.

This formalization highlights how the interaction

between salience, emotional weighting, and comparative framing results in an

inherently asymmetric deficiency structure. Therefore, even when preferences

between any two options are individually consistent, their aggregation may

yield non-transitive cycles, capturing the paradoxical decision dynamics often

observed in perfectionist agents.

Since

both the attentional salience function

si(y,x)

and the dynamic weights

wi(y→x)

vary with the direction of

comparison (i.e.,

si(y,x)≠si(x,y)

and

wi(y→x)≠wi(x→y))

, the deficiency penalty

δ(x

∣

y)

generally differs from

δ(y

∣

x)

.

This directional dependence

creates the conditions for preference cycles, where an individual may prefer

option A over B, B over C, but then C over A, leading to non-transitive

preferences and potential decision-making inconsistencies.

3.4. Application to Perfectionism

In

extreme manifestations of perfectionism, the sensitivity parameter γ in the

model can be conceptualized as approaching infinity. This

scenario represents individuals who are infinitely sensitive to any relative

deficiencies among options.

As γ→∞, the deficiency penalty (x∣ y)

becomes dominant in the utility calculation. In this limit, even the slightest

deficiency in option x's attribute compared to option y results in an infinite penalty,

effectively rendering U(x∣ y)

→ -∞ if x is inferior in any attribute.

This implies that the individual will only consider

options that are not worse in any attribute than others. If every option has at

least one attribute that is inferior to another, the individual perceives all

options as infinitely flawed, leading to decision paralysis.

This framework accounts for empirical observations

of decision cycles, such as an agent preferring option A over B due to superior

design, B over C for better performance, and yet C over A because of lower

cost. While each comparison is internally consistent and emotionally coherent,

the overall preference structure violates transitivity.

Such non-transitive preferences are particularly

prevalent among individuals who place significant importance on details,

especially when evaluating complex products with multiple attributes. In these

scenarios, the emphasis on avoiding any relative deficiency can lead to

cyclical decision patterns, where no single option emerges as the unequivocal

best choice.

In extreme cases, particularly among those

exhibiting obsessive-compulsive perfectionism, this heightened sensitivity to

imperfections can result in decision paralysis. The overwhelming focus on minor

flaws prevents the individual from making any choice, as each option is

perceived as insufficient in some respect. This aligns with findings that

individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) often exhibit

indecisiveness and avoidance of uncertainty, even when the task at hand is

unrelated to their primary symptomatology (Rasmussen & Eisen, 1992; Reed, 1985; Tolin et al., 2003).

3.5. Formal Conditions for Preference Cycles

Proposition

1.

Let

u(

⋅

)

be the baseline

utility ranking with

u(A)

> u(B) > u(C)

and

define the deficiency-penalized utility (

Equation 6):

Then a strict cycle

A≻ B, B≻ C, C≻ A

obtains if and only if

γ[S(A→C) − S(C→A)] > u(C) − u(A).

Proof.

(A∣ B)> (B∣ A) ⟺ u(A)−γ S(A→ B) > u(B)−γ S(B→ A)

which rearranges to

u(A)−u(B) > γ [S (A→ B) −S(B→A)].

- 2.

Similarly,

B≻ C⟺ u(B)−u(C)>γ[S(B→C) −

S(C→B)].

- 3.

Finally,

C≻ A⟺ u(C)−u(A)>γ[S(C→A) −

S(A→C)],

which is algebraically equivalent to (1). Since the

first two inequalities hold under the baseline ranking u(A)>u(B)>u(C),

the emergence of the full cycle hinges precisely on condition (1).

Comparative Statics.

From (1) we obtain a critical threshold (

Equation

7):

So that intransitive loops appear whenever . Because u(C)−u(A)<0 and we assume S(A→C)>S(C→A) (i.e., A’s flaw looms larger), γ* is strictly positive. As γ grows, the region of parameter space admitting cycles expands, illustrating how intensifying perfectionism magnifies choice distortions.

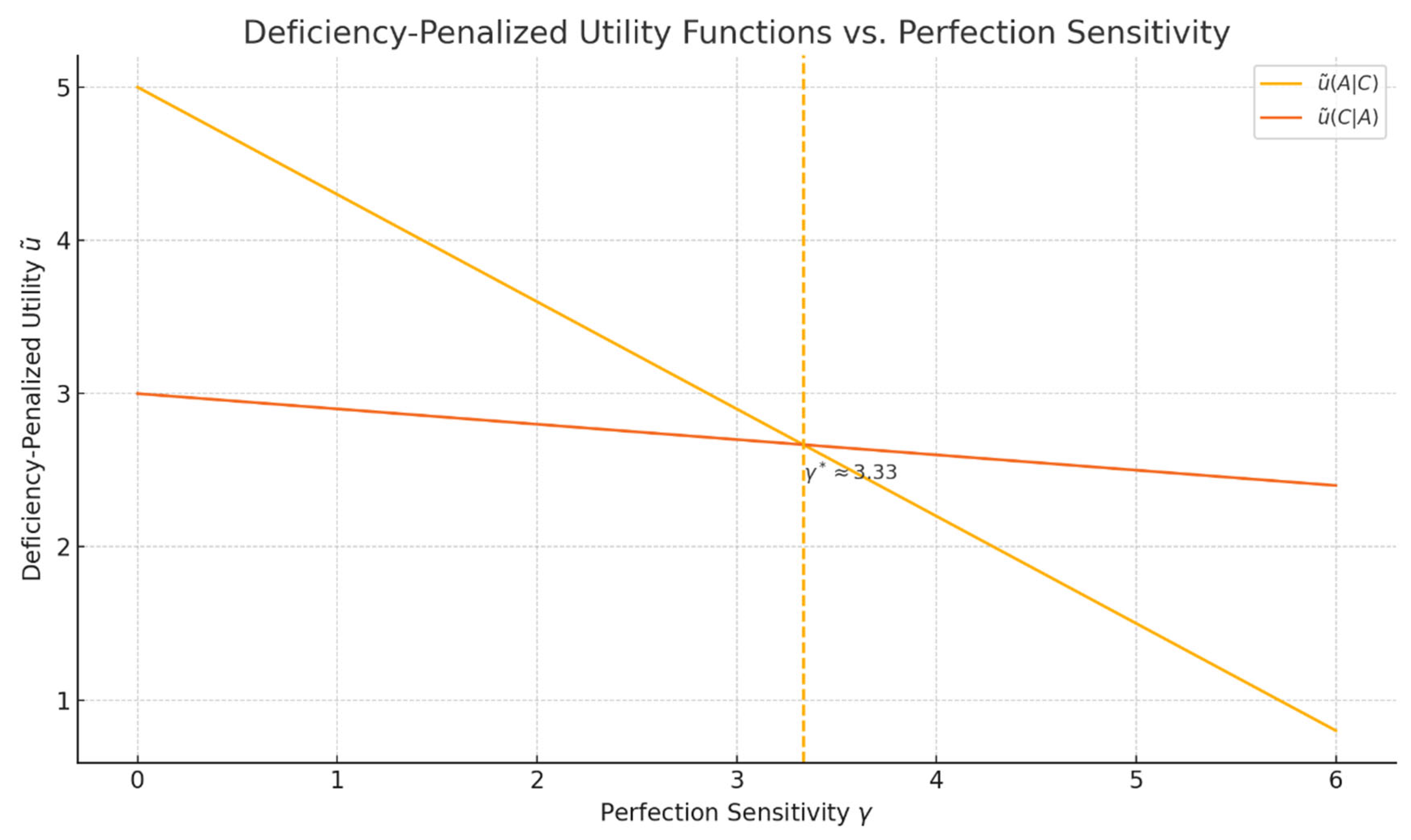

3.6. Numerical Illustration

For illustrative purposes, assume the following calibration of parameters:

u(A)=5, u(C)=3, S(A→C)=0.7, S(C→A)=0.1, and allow γ to range from 0 to 6. The dashed vertical line indicates the critical threshold

As a visual complement to the formal conditions derived above,

Figure 1 plots the deficiency-penalized utilities

(A∣C) and

(C∣A) against the perfection-sensitivity parameter γ.

(A∣C) and (C∣A) as functions of perfection sensitivity γ.

The upper curve shows (A∣C)=5−0.7γ, the lower curve shows (C∣A)=3−0.1γ,

Dashed vertical line marks the threshold ≈3.33, where the two utilities cross.

For γ<3.33, (A∣C)>(C∣A), so A≻C. Once γ exceeds the threshold, the order flips and C≻A, completing the intransitive cycle A≻B≻C≻A. This graphic succinctly illustrates how increasing sensitivity to imperfections generates the preference reversal at the core of our model. where (A∣C) and (C∣A) intersect. For γ<γ*, A remains preferred to C; once γ exceeds this value, the perceived penalty on A’s flaw is large enough to reverse the ordering, yielding C≻A and completing the intransitive cycle.

The model provides a psychologically plausible mechanism through which non-transitive, emotionally distorted preferences can arise systematically, especially among individuals with high sensitivity to imperfection. It bridges affective decision-making with formal economic reasoning and lays the groundwork for analyzing real-world consequences of consumer behavior, policy choice, and mental health economics.

Figure 2.

Simplified cyclic preference graph for a laptop purchase under perfectionist evaluation.

Figure 2.

Simplified cyclic preference graph for a laptop purchase under perfectionist evaluation.

4. Discussion

The asymmetry in deficiency assessments, where δ(x|y) ≠ δ(y|x), arises from several interrelated psychological mechanisms, particularly pronounced in individuals with perfectionistic tendencies. These mechanisms contribute to non-transitive preferences and decision-making challenges, aligning with our model's emphasis on how perfectionists evaluate options.

When comparing options, the prominence of specific attributes can vary depending on the reference point. Evaluating option x relative to option y may highlight different deficiencies than evaluating y relative to x. This phenomenon is rooted in shifting reference points that influence attribute prominence during comparisons. Tversky's (1977) work on similarity judgments demonstrated that people often perceive asymmetry in similarity based on the direction of comparison, attributing more features to the more salient or familiar item. Similarly, Dhar and Simonson (1992) found that contextual factors can alter attribute weighting, leading to preference reversals. In the context of perfectionism, this means that when a perfectionist evaluates option x against option y, the strengths of y become the benchmark, making the deficiencies of x more prominent. Conversely, when the comparison is reversed, different attributes may become salient, leading to a different set of perceived deficiencies. This shifting salience contributes to the asymmetry in deficiency evaluation.

Perfectionists tend to exhibit a cognitive bias toward focusing on negative attributes or deficiencies in options. This selective attention to flaws is not uniformly applied across comparisons, resulting in asymmetrical evaluations. Frost et al. (1990) identified that individuals with high perfectionistic concerns are more sensitive to mistakes and imperfections. Hewitt and Flett (1991) further elaborated on this by distinguishing between self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism, both involving heightened sensitivity to perceived shortcomings. This negative focus means that when comparing options, perfectionists may disproportionately emphasize the deficiencies of the option under consideration, especially if it falls short of their high standards. The intensity of this focus can vary depending on the direction of comparison, contributing to the asymmetry in deficiency evaluation.

Traditional decision-making models often assume stable attribute weights across comparisons. However, in practice, especially among perfectionists, these weights can dynamically shift based on the comparison context. An attribute deemed critical in one comparison may be considered less important in another. This aligns with the concept of constructed preferences, where individuals build their preferences during the decision-making process rather than revealing pre-existing ones. Payne et al. (1992) discussed how decision strategies can vary based on task demands, leading to different attribute weightings. Slovic (1995) also emphasized that preferences are often constructed and influenced by the context in which choices are made. In the context of perfectionism, this dynamic weighting means that the importance assigned to specific attributes can change depending on which option is being evaluated against which, further contributing to the asymmetry in deficiency evaluation.

Understanding these psychological mechanisms provides insight into the challenges perfectionists face in decision-making. The interplay of contextual salience, selective negative focus, and dynamic weight distortion leads to asymmetric deficiency evaluations, which can result in preference cycles and decision paralysis. Integrating these insights into our model highlights the importance of addressing these cognitive biases to facilitate more balanced and effective decision-making strategies for individuals with perfectionistic tendencies.

4.1. Perfectionism and Decision Paralysis: Integrating Psychological Mechanisms into the Formal Model

Building upon our formal model of deficiency-penalized utility, we delve deeper into the psychological mechanisms through which perfectionism contributes to decision paralysis. This integration not only reinforces the theoretical underpinnings of our model but also aligns with empirical findings in the field.

In our model, the utility of an option x is adjusted by a deficiency penalty δ(x∣y), representing the perceived shortcomings of x relative to another option y. This penalty is influenced by factors such as attentional salience si(y,x), dynamic weights wi(y→x), and the sensitivity parameter γ. Perfectionist individuals, characterized by an excessive concern over mistakes and high personal standards, are particularly susceptible to these cognitive distortions.

Perfectionists often exhibit all-or-nothing thinking, where decisions are viewed as either entirely right or entirely wrong, leaving no room for acceptable imperfection (Frost et al., 1990; Hewitt & Flett, 1991). This cognitive distortion amplifies the deficiency penalty δ(x∣y), as even minor shortcomings are perceived as significant failures. Consequently, the utility of viable options is diminished, leading to indecision.

Moreover, perfectionists tend to overanalyze options in pursuit of the optimal choice, leading to information overload and analysis paralysis (Iyengar et al., 2006). In our model, this behavior is reflected in heightened attentional salience si(y,x), where the focus on each attribute's deficiency becomes so pronounced that it hinders the aggregation of utility across options. The dynamic weights wi(y→x) also fluctuate, as the importance assigned to specific attributes changes depending on the comparison direction, further complicating decision-making.

Intolerance of uncertainty is another hallmark of perfectionism, where individuals struggle with making decisions when outcomes are uncertain, fearing that an imperfect choice could lead to negative consequences (Egan et al., 2011). This intolerance is captured in our model by the sensitivity parameter γ, which modulates the overall impact of deficiencies on utility. A higher γ indicates greater emotional sensitivity to perceived shortcomings, thus increasing the likelihood of decision paralysis.

Furthermore, perfectionists often tie their self-worth to the outcomes of their decisions, leading to heightened emotional investment and avoidance of decision-making to protect self-esteem (Shafran et al., 2002). This emotional attachment exacerbates the perceived deficiencies of options, as any potential imperfection is seen as a reflection of personal inadequacy. In our model, this is represented by an increased γ, amplifying the deficiency penalties and reinforcing indecision.

By integrating these psychological mechanisms into our formal model, we provide a comprehensive understanding of how perfectionism leads to decision paralysis. This alignment between theoretical constructs and empirical observations enhances the model's applicability to real-world decision-making scenarios.

4.2. Implications and Broader Significance

The deficiency-penalized utility model introduced in this paper provides a unifying theoretical framework for understanding behavioral anomalies related to perfectionism, particularly those involving decision-making difficulties. While much of the literature on bounded rationality has emphasized limitations in computational capacity, attention span, or information access (Simon, 1955; Rubinstein, 1998), our model focuses on emotional asymmetry, specifically, the tendency of certain individuals to overweigh what is lacking in an option rather than what it offers. This shift in evaluative structure reframes irrationality not merely as a cognitive failure, but as an emotionally skewed distortion of relative value.

In the domain of consumer behavior, this framework helps explain well-documented patterns of decision fatigue, post-purchase regret, prolonged deliberation, and abandonment of shopping carts, especially among “maximizers” (Loomes & Sugden, 1982; Schwartz et al., 2002; Iyengar et al., 2006). For perfectionist individuals, decision paralysis arises not from lack of options or information, but from an evaluative mechanism that penalizes each alternative for its deficiencies in comparison to others. The result is cyclical preference structures, unstable satisfaction, and an aversion to final commitment. These insights suggest that behavioral interventions, such as reducing available choice sets, emphasizing sufficiency over optimality, or implementing commitment-enhancing tools like time limits or defaults, may be particularly effective for mitigating the negative impact of deficiency sensitivity in digital marketplaces.

Beyond the consumer context, the model is relevant for mental health economics. Perfectionism, particularly in its clinical or obsessive-compulsive forms, carries significant economic consequences: reduced productivity, increased healthcare utilization, poor treatment adherence, and impaired social functioning (Egan et al., 2011; Shafran et al., 2002). Our model suggests that these outcomes stem not merely from symptomatic anxiety or compulsivity, but from a fundamentally non-transitive structure of preferences, driven by emotionally overactive evaluations of imperfection. This reconceptualization supports the integration of behavioral parameters into models estimating the mental health burden, extending beyond traditional diagnostic categories. Economically, early intervention through cognitive-behavioral therapy or decision-structuring tools may help reduce long-term costs and improve the daily functioning of individuals prone to evaluative rigidity.

In the broader theoretical sphere, our model adds a critical layer to the study of bounded rationality by incorporating affective salience. Emotional penalties, such as regret, anxiety, or intolerance of imperfection, may be just as structurally impactful as information gaps. As such, even agents who are consistent, deliberate, and self-aware may display non-transitive behaviors if emotional asymmetry dominates their comparative reasoning. This challenges the core premise of revealed preference theory, which assumes that choices reliably reveal welfare. If preferences are emotionally distorted in predictable ways, then maximizing behavior may not indicate true satisfaction, and interventions aimed at modifying choice environments may have normatively desirable effects.

Finally, these insights carry important implications for public policy and institutional design. In systems that require complex decisions, such as pension plans, healthcare enrollment, or educational pathways, the assumption of transitive, stable preferences may not hold for all users. For individuals with high deficiency sensitivity, these systems may provoke avoidance, reliance on defaults, or persistent dissatisfaction regardless of outcome. Recognizing this, policymakers should consider emotionally informed choice architectures that reduce psychological friction: offer Comparable offers, narrow options, frame decisions affirmatively, and provide tools to manage trade-offs may not only improve user experience but also enhance policy efficiency. In this way, the deficiency-penalized framework expands the scope of welfare economics by integrating psychological structure into the heart of evaluative decision-making.

While the deficiency-penalized framework generates clear theoretical predictions, its core assumptions remain empirically untested. Future research should therefore focus on empirical calibration of salience functions and sensitivity γ - using controlled lab experiments and field studies to measure how individuals perceive and penalize flaws across real choice sets. Experimental designs can directly test for preference cycles in multi-attribute tasks, while longitudinal or intervention studies (e.g., cognitive training or therapy) could reveal whether and how γ evolves. Grounding these parameters in observed behavior will both validate the model’s scope and guide practical efforts to mitigate perfectionism-driven distortions.

5. Conclusions

This paper has proposed a novel theoretical framework for understanding how perfectionist tendencies, particularly those associated with obsessive-compulsive traits, can lead to violations of transitive preferences and, consequently, to cyclical, indecisive, and inefficient patterns of choice. By introducing the concept of a deficiency-penalized utility function, we modeled how individuals may consistently evaluate each option in light of what it lacks relative to others, rather than what it offers in absolute terms. This relative and emotionally charged focus on imperfection leads to intransitive preferences that follow a psychologically coherent, but economically inefficient, structure.

Unlike traditional explanations of irrationality based on "noise", heuristics, or information limitations, the model presented here attributes decision anomalies to structured affective distortions, particularly the overemphasis on comparative deficiencies. This is an important departure from the canonical view of economic agents, as it suggests that decision paralysis, repeated checking, or consumer dissatisfaction may not arise from informational deficits or computational failures, but rather from an internal evaluative system that systematically prioritizes flaw-avoidance over benefit optimization. Such a system may be adaptive in certain contexts, helping individuals avoid error or regret, but when it dominates decision-making, it creates emotional and economic burdens.

The deficiency-penalized utility model is simple yet powerful. It captures a wide range of empirical behaviors observed among perfectionist individuals and provides a mechanism that is both formally tractable and behaviorally plausible. Importantly, it also generates testable predictions. For instance, it suggests that individuals with high deficiency sensitivity will exhibit longer deliberation times, greater regret following decisions, a higher likelihood of decision reversal, and increased susceptibility to decision fatigue when the number of options is large or when each option is described in highly differentiated terms. These predictions open the door to experimental validation and empirical refinement.

The model also has normative implications. If some individuals experience emotional penalties when confronted with imperfection, then their observable choices may not reflect their underlying welfare. This undermines core assumptions in revealed preference theory and calls for the incorporation of emotional and psychological costs into welfare evaluations. Moreover, the existence of cyclic and unstable preferences challenges standard optimization-based approaches to public policy design, which often presume that giving individuals more choices will increase utility. Our findings suggest that for certain populations, particularly those vulnerable to perfectionism or obsessive thought patterns, more choice can reduce welfare unless accompanied by supportive structures that help individuals tolerate imperfection and accept trade-offs.

Looking forward, this framework invites interdisciplinary extensions. From a psychological standpoint, it aligns with research on intolerance of uncertainty, regret sensitivity, and the neurocognitive correlates of obsessive-compulsive behaviors. From a behavioral economic perspective, it connects to models of reference-dependent preferences, regret aversion, and bounded rationality, while adding a novel emotional dimension to the construction of utility. From a policy and design standpoint, it encourages the development of choice architectures that protect individuals from the cognitive and emotional costs of excessive deliberation.

Several avenues for further research naturally emerge. One direction involves empirical testing of the model’s predictions, particularly in experimental settings that manipulate the salience of deficiencies or the framing of options. Another direction is the integration of this framework into applied domains such as healthcare decision-making, online platforms, and educational advising, where perfectionism-related behaviors are especially common. Additionally, future work could examine the interaction between deficiency sensitivity and other cognitive biases, such as loss aversion, status quo bias, or ambiguity aversion, to better understand how emotional and cognitive constraints jointly shape economic behavior.

Finally, at a conceptual level, this paper calls for a reexamination of what constitutes “rational” economic decision-making. If rationality is to be defined not merely as consistency in preference order but as the capacity to act following one’s values and to achieve psychological coherence, then models such as the one developed here serve to broaden the theoretical foundations of economics. They help illuminate the invisible, affective costs embedded in everyday choice, and they offer tools for understanding when and why people may fail to choose what is best for them, even when all information is available and presented.

By recognizing that imperfection can carry a psychological penalty, we explain inefficient behavior and offer a theoretical framework for the emotional logic underpinning decision-making. Rather than pathologizing these behaviors, the model addresses them as internally coherent responses to emotionally significant imperfections. This approach expands the analytical boundaries of economic rationality by incorporating psychological coherence as a legitimate foundation for preference construction and decision-making behavior. In doing so, we contribute to a broader understanding of economic behavior, one that integrates psychological experience into the core of rational choice modeling and opens new avenues for supportive intervention, institutional design, and welfare analysis.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bayer, Y.M.; Osher, Y. Time preference, executive functions, and ego-depletion: An exploratory study. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics 2018, 11(3), 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, Y.M.; Ruffle, B.; Zultan, R.; Dwolazky, T. Time preferences in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI); Laurier Centre for Economic Research and Policy Analysis: Toronto, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bayer, Y.M.; Shtudiner, Z.; Suhorukov, O.; Grisaru, N. Time and risk preferences, and consumption decisions of patients with clinical depression. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 2019, 78, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, Y.M.; Shtudiner, Z. Sirens of stress: Financial risk, time preferences, and post-traumatic stress disorder: Evidence from the Israel-Hamas Conflict. Journal of Health Psychology 2024, 29(13), 1489–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, R.; Simonson, I. The effect of forced choice on choice. Journal of Marketing Research 1992, 29(2), 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, S.J.; Wade, T.D.; Shafran, R. Perfectionism as a transdiagnostic process: A clinical review. Clinical Psychology Review 2011, 31(2), 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R.O.; Steketee, G. Perfectionism in obsessive–compulsive disorder patients. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1997, 35(4), 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R.O.; Marten, P.; Lahart, C.; Rosenblate, R. The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research 1990, 14(5), 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, P.L.; Flett, G.L. Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1991, 60(3), 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S.S.; Lepper, M.R. When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2000, 79(6), 995–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S.S.; Wells, R.E.; Schwartz, B. Doing better but feeling worse: Looking for the "best "job undermines satisfaction. Psychological Science 2006, 17(2), 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomes, G.; Sugden, R. Regret theory: An alternative theory of rational choice under uncertainty. The Economic Journal 1982, 92(368), 805–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, P.; Mariotti, M. Sequentially rationalizable choice. American Economic Review 2007, 97(5), 1824–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.M.; De Bruin, W.B.; Fischhoff, B. Maximizers versus satisficers: Decision-making styles, competence, and outcomes. Judgment and Decision Making 2007, 2(6), 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.W.; Bettman, J.R.; Johnson, E.J. Behavioral decision research: A constructive processing perspective. Annual Review of Psychology 1992, 43(1), 87–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkarskaya, H.; Tolin, D.; Ruderman, L.; Kirshenbaum, A.; Kelly, J.M.; Pittenger, C.; Levy, I. Decision-making under uncertainty in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2015, 69, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, S.A.; Eisen, J.L. The epidemiology and clinical features of obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychiatric Clinics 1992, 15(4), 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, G.F. Obsessional experience and compulsive behaviour: A cognitive-structural approach. Personality, Psychopathology, and Psychotherapy 1985, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein, A. Modeling bounded rationality; MIT Press; Cambridge, MA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, B.; Ward, A.; Monterosso, J.; Lyubomirsky, S.; White, K.; Lehman, D.R. Maximizing versus satisficing: Happiness is a matter of choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2002, 83(5), 1178–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafran, R.; Cooper, Z.; Fairburn, C.G. Clinical perfectionism: A cognitive–behavioural analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2002, 40(7), 773–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, H.A. A behavioral model of rational choice. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 1955, 69(1), 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. The construction of preference. American Psychologist 1995, 50(5), 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S; Bayer, Y.M. Is All Mental Harm Equal? The Importance of Discussing Civilian War Trauma from a Socio-Economic Legal Framework’s Perspective. Nordic Journal of International Law 2023, 92(4), 528–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeber, J.; Otto, K. Positive conceptions of perfectionism: Approaches, evidence, challenges. Personality and Social Psychology Review 2006, 10(4), 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolin, D.F.; Abramowitz, J.S.; Brigidi, B.D.; Foa, E.B. Intolerance of uncertainty in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 2003, 17(2), 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A. Features of similarity. Psychological Review 1977, 84(4), 327–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).