1. Introduction

Intertemporal choice has long been central to economic theory, traditionally modeled through exponential discounting, which assumes consistent preferences over time. However, decades of empirical and theoretical research have demonstrated that individuals systematically depart from this framework. Most prominently, present bias, the tendency to overweight immediate rewards relative to future ones, has emerged as one of the most robust deviations from rational choice theory (Laibson, 1997; Frederick, Loewenstein, & O'Donoghue, 2002).

Quasi-hyperbolic discounting models, which introduce a parameter β < 1 to capture present bias alongside standard exponential discounting, have successfully accounted for behaviors such as procrastination, undersaving, and health-related inaction (O'Donoghue & Rabin, 1999). Within this framework, individuals exhibit dynamically inconsistent preferences, favoring immediate gratification despite recognizing the long-term costs. This recognition has led to extensive research on sophisticated agents who are aware of their future time inconsistency and may take preemptive steps to mitigate its effects (O'Donoghue & Rabin, 2001).

The literature on behavioral sophistication generally assumes that self-awareness improves outcomes. Sophisticated agents can use commitment devices, structure incentives to align short-term actions with long-term goals, or implement various self-regulation strategies (Ariely & Wertenbroch, 2002; Thaler, 1999). This perspective suggests that recognizing one's biases is the first step toward overcoming them, and that greater sophistication leads to better decision-making and higher welfare.

However, this conventional wisdom rests on an unexamined assumption: that eliminating bias necessarily improves welfare. While it seems intuitive that removing cognitive distortions should enhance decision-making, this intuition presupposes that welfare should be measured according to some external standard of rationality rather than according to individuals' authentic preferences. If we define welfare according to people's actual preference structures, including their biases, then the relationship between bias correction and welfare becomes far more complex.

This paper challenges the assumption that perfect bias correction enhances welfare by developing a formal model of metacognitive adjustment in intertemporal choice. I analyze a present-biased agent who is aware of their bias and can choose the degree to which they attempt to correct it through a self-imposed adjustment parameter. The central question is whether such an agent should eliminate their bias, correct it partially, or perhaps not correct it at all.

The model reveals a fundamental paradox in behavioral self-correction. While perfect bias neutralization is mathematically feasible, agents can eliminate present bias and achieve time-consistent exponential discounting, doing so actually reduces welfare compared to not correcting whatsoever. This counterintuitive result emerges because the agent's "true" utility function is itself defined by present-biased preferences. When agents force themselves to behave according to normative standards of rationality, they make choices that contradict what maximizes their happiness according to their own preference structure.

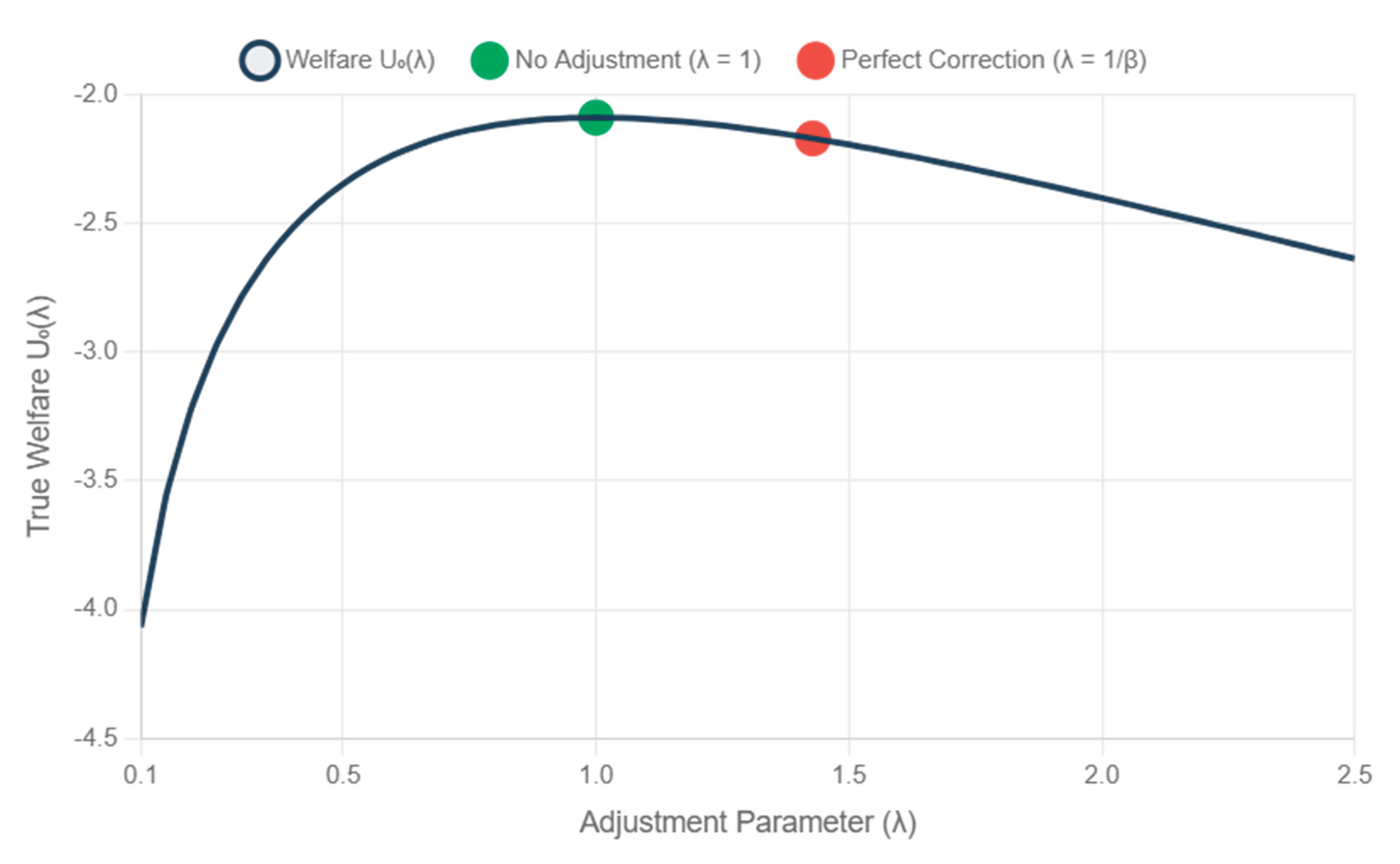

Using a three-period quasi-hyperbolic discounting framework with logarithmic utility, I demonstrate that welfare is uniquely maximized when agents make no metacognitive adjustment to their decision-making process. Perfect bias correction, while achieving the normatively desirable goal of time consistency, systematically reduces welfare across a wide range of empirically realistic parameter values. This finding holds although perfect correction successfully transforms decision weights to match those of exponential discounting.

The implications of this self-correction paradox extend far beyond individual decision-making. The results suggest that behavioral interventions, nudges, and commitment devices may need fundamental reconceptualization. Rather than helping people achieve normatively optimal behavior, such tools might be more effective if they help individuals understand and work with their authentic preferences, even when those preferences deviate from theoretical benchmarks. The findings also illuminate a deeper philosophical tension between two competing conceptions of rationality: behavior that conforms to external standards versus behavior that maximizes subjective well-being.

From a theoretical perspective, the research contributes to our understanding of the relationship between sophistication and welfare in behavioral economics. It demonstrates that greater self-awareness and stronger capacity for self-regulation do not automatically translate into better outcomes. Sometimes, the most sophisticated choice may be to accept rather than correct one's apparent limitations. This insight challenges fundamental assumptions about the goals of behavioral economics and suggests new directions for research on individual decision-making and policy design.

The central contribution of this research is to show that the relationship between behavioral sophistication and welfare is more nuanced than previously understood. While the capacity for self-correction represents an important human capability, perfect self-correction may neither be necessary nor sufficient for optimal welfare. Instead, authenticity, making choices that align with one's genuine preferences, even when those preferences embody apparent inconsistencies, may sometimes be more valuable than conformity to abstract rational ideals.

2. Theoretical Framework

We consider a three-period model, t = 0, 1, 2, in which an agent allocates a fixed resource endowment (normalized to 1) across periods. Preferences follow a quasi-hyperbolic structure with standard concave instantaneous utility u(cₜ) = ln(cₜ), where cₜ denotes consumption in period t.

The agent's authentic preferences are characterized by the following present-biased utility function:

where δ ∈ (0, 1] is the exponential discount factor and β ∈ (0, 1] captures the degree of present bias. When β < 1, the agent exhibits present bias, placing disproportionate weight on immediate consumption relative to future periods.

The central feature of our model is that the agent possesses metacognitive awareness of their present bias and can choose to adjust their decision-making process. Specifically, the agent selects an adjustment parameter λ ≥ 0 and makes consumption decisions by maximizing an adjusted utility function:

subject to the budget constraint c₀ + c₁ + c₂ = 1.

The adjustment parameter λ represents different approaches to self-regulation:

λ = 1: No adjustment - the agent uses their original biased preferences without any metacognitive intervention

λ = 1/β: Complete bias neutralization - the adjusted utility function becomes ln(c₀) + δ ln(c₁) + δ² ln(c₂), corresponding exactly to exponential discounting

λ ∈ (1, 1/β): Partial bias correction - the agent moderates but does not eliminate their present bias

λ > 1/β: Overcorrection - the agent overcompensates for their bias, creating a preference structure that favors future consumption beyond what exponential discounting would prescribe

The distinction between the true utility function U₀ and the adjusted utility function Ũ₀ is crucial for understanding the welfare implications of different adjustment strategies. The adjusted utility function represents the decision criterion the agent employs when choosing consumption levels, while the true utility function determines the actual welfare consequences of those choices.

This framework captures the realistic scenario faced by individuals who recognize their tendency toward present bias and consider implementing various self-regulation strategies. Examples include establishing strict budgets to control spending, using commitment devices to enforce savings goals, or adopting personal rules that limit immediate gratification. The adjustment parameter λ can be interpreted as a proxy for the intensity of such metacognitive interventions, with higher values representing more aggressive attempts to counteract present bias.

The model's key insight emerges from recognizing that perfect alignment between decision-making and welfare maximization occurs only when λ = 1. When the agent chooses any other value of λ, they create a wedge between their decision criterion and their authentic preferences, potentially reducing welfare despite achieving various normative goals such as time consistency. This observation leads to what we term the self-correction paradox: an agent may achieve higher welfare by accepting their bias rather than attempting to correct it completely.

The correction parameter λ may also be interpreted as reflecting individual differences in cognitive control and metacognitive insight. Agents with stronger executive functioning or better self-awareness are likely to calibrate λ more effectively, though our analysis suggests that the optimal calibration may involve accepting rather than eliminating one's biases. This interpretation connects our model to psychological literature on self-regulation and cognitive resources, while challenging conventional assumptions about the relationship between cognitive sophistication and behavioral outcomes.

The mathematical structure of our model ensures tractable analytical solutions while capturing the essential tension between normative ideals and subjective welfare. The three-period framework provides sufficient complexity to illustrate intertemporal trade-offs while remaining analytically manageable. The logarithmic utility function guarantees interior solutions and allows for clean comparative statics, though the qualitative insights extend to more general utility specifications.

2.1. Model Setup and Basic Framework

We analyze a three-period intertemporal choice problem where an agent at time t = 0 must allocate a fixed endowment across periods t = 0, 1, 2. The total endowment is normalized to unity, so that c₀ + c₁ + c₂ = 1, where cₜ represents consumption in period t. We assume logarithmic instantaneous utility u(cₜ) = ln(cₜ), which exhibits the standard properties of positive but diminishing marginal utility.

The agent's authentic preferences follow a quasi-hyperbolic discounting structure, which we designate as their true utility function:

where δ ∈ (0,1] represents the standard exponential discount factor and β ∈ (0,1] captures the degree of present bias. When β < 1, the agent exhibits present bias, placing disproportionate weight on immediate consumption relative to all future periods. When β = 1, preferences reduce to standard exponential discounting without present bias.

The key feature of our model is that the agent possesses metacognitive awareness of their present bias and considers implementing a self-adjustment strategy. Specifically, the agent can choose an adjustment parameter λ ≥ 0 and make consumption decisions by maximizing an adjusted utility function:

This adjusted utility function represents the decision criterion the agent uses when allocating consumption, while the true utility function U₀ represents the actual welfare consequences of those choices. The distinction between these two functions is crucial for understanding the self-correction paradox that emerges in our analysis.

The adjustment parameter λ allows the agent to implement different correction strategies. When λ = 1, the agent does not adjust whatsoever and simply maximizes their original quasi-hyperbolic utility function. This corresponds to accepting one's present bias and making decisions accordingly. When λ = 1/β, the adjusted utility function takes the form ln(c₀) + δ ln(c₁) + δ² ln(c₂), which corresponds exactly to exponential discounting. This represents perfect bias correction, completely neutralizing the present bias inherent in the agent's authentic preferences. Values of λ between 1 and 1/β represent partial corrections, while λ > 1/β represents overcorrection that reverses the bias in favor of future periods.

The central question our model addresses is which value of λ maximizes the agent's true welfare as measured by U₀. Intuitively, one might expect that perfect bias correction (λ = 1/β) would yield the highest welfare by eliminating the inefficiencies associated with present bias. However, our analysis reveals that this intuition is incorrect. Because the agent's true utility function is itself defined by present-biased preferences, forcing oneself to behave according to exponential discounting principles can reduce welfare.

This setup captures a realistic scenario faced by many individuals who recognize their tendency toward present bias and consider various strategies for self-regulation. Examples include setting strict budgets to control spending, using commitment devices to enforce savings plans, or implementing rules to limit immediate gratification in favor of long-term goals. Our model provides a framework for analyzing when such strategies enhance welfare and when they may be counterproductive.

The mathematical structure of the model ensures that all consumption levels remain positive and that the budget constraint is satisfied. The logarithmic utility function guarantees interior solutions and allows for clean analytical results. While this functional form involves some loss of generality, it captures the essential features of intertemporal choice under present bias while remaining tractable for analysis. Extensions to more general utility functions would preserve the qualitative insights while complicating the mathematical derivations.

2.2. The Self-Correction Paradox

The model presented here illuminates a fundamental tension in behavioral self-regulation that has received limited attention in the literature. When we define the agent's welfare according to their quasi-hyperbolic preferences (as captured in the true utility function U₀), we create a situation where perfect bias correction may reduce well-being. This paradox emerges from the conflicting demands of normative rationality and subjective welfare maximization.

To understand this tension, consider that the agent faces a choice between two fundamentally different approaches to decision-making. The first approach involves setting λ = 1/β, which transforms their effective discount weights to (1, δ, δ²), perfectly replicating the exponential discounting pattern advocated by standard economic theory. This choice eliminates present bias entirely and ensures time-consistent preferences across all periods. From the perspective of normative economics, this represents the ideal solution to the agent's self-control problem.

However, this normative ideal conflicts with welfare maximization as measured by the agent's actual utility function. When the agent forces themselves to behave according to exponential discounting principles, they make consumption choices that contradict what would maximize their happiness according to their preference structure. The resulting allocation overweights future consumption relative to what the agent's authentic preferences would dictate, leading to a reduction in overall welfare despite the achievement of time consistency.

The alternative approach involves setting λ = 1, which corresponds to making no metacognitive adjustment whatsoever. Under this strategy, the agent simply maximizes their original quasi-hyperbolic utility function without attempting any correction for present bias. While this approach maintains the agent's time-inconsistent preferences and violates standard assumptions of rational choice theory, it yields higher welfare as measured by the agent's actual utility function. The reason is straightforward: the consumption allocation resulting from λ = 1 aligns perfectly with what the agent's preferences value, even though these preferences embody present bias.

This creates what we term the self-correction paradox. An agent who is fully aware of their present bias and possesses the technical knowledge to correct it completely may nonetheless choose not to do so if their goal is welfare maximization rather than conformity to normative standards. The paradox highlights a deeper philosophical question about the nature of rationality itself: should rational choice be defined as behavior that conforms to theoretical ideals, or as behavior that maximizes an agent's authentic well-being?

The implications of this paradox extend beyond individual decision-making to broader questions in behavioral economics and policy design. If perfect bias correction reduces welfare, then interventions aimed at helping people overcome cognitive limitations may need to be reconsidered. Rather than pushing individuals toward normatively optimal behavior, such interventions might focus on helping people understand and work with their authentic preferences, even when those preferences deviate from theoretical benchmarks.

Furthermore, the paradox suggests that the relationship between sophistication and welfare is more complex than typically assumed. While the capacity for self-reflection and behavioral adjustment represents an important human capability, our analysis indicates that this capability may be optimally deployed in service of authentic preference satisfaction rather than normative compliance. In essence, the most sophisticated choice may be the recognition that one's "biased" preferences represent genuine aspects of personal well-being that should be respected rather than corrected.

2.3. Mathematical Analysis and Optimal Consumption

To analyze the agent's behavior under different adjustment strategies, we solve the optimization problem using standard Lagrangian methods. The agent chooses consumption levels to maximize their adjusted utility function Ũ₀ = ln(c₀) + λβδ ln(c₁) + λ²β²δ² ln(c₂) subject to the budget constraint c₀ + c₁ + c₂ = 1.

The Lagrangian for this problem is L = ln(c₀) + λβδ ln(c₁) + λ²β²δ² ln(c₂) + μ(1 - c₀ - c₁ - c₂), where μ is the Lagrange multiplier associated with the budget constraint. Taking first-order conditions concerning each consumption level yields the standard result that marginal utility per dollar should be equalized across periods according to the adjusted utility function.

This optimization yields the following optimal consumption allocations: c₀* = 1/S, c₁* = λβδ/S, and c₂* = λ²β²δ²/S, where S = 1 + λβδ + λ²β²δ² serves as a normalization factor ensuring that consumption levels sum to the total endowment. These expressions reveal how the adjustment parameter λ systematically affects the temporal distribution of consumption. Higher values of λ shift consumption toward future periods, while lower values concentrate consumption in the present.

The welfare implications of different adjustment strategies become apparent when we evaluate the agent's true utility function U₀ = ln(c₀) + βδ ln(c₁) + β²δ² ln(c₂) at the optimal consumption levels. This evaluation reveals the central paradox of our analysis. When λ = 1, the agent does not adjust their decision-making process and simply maximizes their original quasi-hyperbolic utility function. The resulting consumption allocation perfectly aligns with the agent's authentic preferences, yielding the highest possible welfare under their true utility function.

In contrast, when λ = 1/β, the agent implements perfect bias correction. This choice transforms the effective discount weights in the adjusted utility function to (1, δ, δ²), which corresponds exactly to exponential discounting. The resulting consumption allocation eliminates present bias and satisfies all standard requirements for intertemporal rationality. However, when we evaluate this allocation according to the agent's true utility function, we find that welfare is lower than under the no-adjustment case.

To illustrate this paradox with concrete numbers, consider an agent with β = 0.7 and δ = 0.9. Under no adjustment (λ = 1), the normalization factor equals S = 2.027, yielding consumption levels c₀ = 0.493, c₁ = 0.311, and c₂ = 0.196. The agent's true welfare under this allocation is U₀ = -2.090. Under perfect bias correction (λ = 1/β ≈ 1.429), the normalization factor becomes S = 2.710, resulting in consumption levels c₀ = 0.369, c₁ = 0.332, and c₂ = 0.299. Despite achieving perfect time consistency, the agent's true welfare under this allocation falls to U₀ = -2.171.

The mathematical structure underlying this paradox can be understood by examining how the adjustment parameter affects the relationship between the agent's decision criterion and their true preferences. When λ = 1, there is perfect alignment between what the agent optimizes and what determines their welfare. When λ ≠ 1, this alignment breaks down, creating a wedge between decision-making and welfare maximization. The larger this wedge, the greater the potential for welfare losses.

This analysis demonstrates that the adjustment parameter λ = 1 represents a unique optimum that cannot be improved upon through any form of bias correction.

Figure 1 illustrates this paradox graphically, showing how true welfare U₀(λ) varies with the adjustment parameter λ for empirically realistic parameter values.

While other values of λ may achieve various normative goals such as time consistency or conformity to theoretical benchmarks, they necessarily reduce welfare as measured by the agent's authentic preferences. The mathematical inevitability of this result highlights the fundamental nature of the self-correction paradox and its implications for our understanding of rational choice.

3. Discussion

The self-correction paradox revealed by our analysis challenges fundamental assumptions in behavioral economics about the relationship between sophistication and welfare. The finding that perfect bias neutralization reduces welfare despite achieving time consistency illuminates deeper questions about the nature of rationality and the goals of behavioral intervention. This section explores the theoretical, philosophical, and practical implications of these results.

3.1. Reconceptualizing Rationality and Welfare

The central insight from our model is that two competing notions of rationality can conflict fundamentally. Normative rationality, as traditionally conceived in economics, suggests that agents should eliminate cognitive biases and conform to theoretical benchmarks such as exponential discounting. Under this view, the agent who sets λ = 1/β and achieves perfect time consistency represents the ideal of rational choice. However, subjective rationality suggests that agents should maximize their authentic well-being as defined by their actual preference structure, even when that structure embodies apparent inconsistencies.

Our analysis demonstrates that these two conceptions of rationality can be mutually exclusive. An agent cannot simultaneously satisfy external standards of rational behavior and maximize their subjective welfare when that welfare is defined by present-biased preferences. This tension reveals a fundamental philosophical question that has been largely overlooked in behavioral economics: whose definition of rationality should govern individual choice?

The conventional approach in behavioral economics assumes that theoretical benchmarks represent superior standards against which actual behavior should be measured. Deviations from these benchmarks are labeled as "biases" or "errors" that reduce welfare and should be corrected. Our model suggests that this approach may be misguided when the agent's authentic preferences themselves define welfare. In such cases, conformity to external standards may constitute the true irrationality, as it involves making choices that systematically reduce one's well-being.

3.2. The Authenticity Principle

The results point toward what might be called an "authenticity principle" in behavioral choice. This principle suggests that welfare maximization requires alignment between decision-making processes and authentic preferences, even when those preferences deviate from normative ideals. Under this view, the agent who chooses λ = 1 demonstrates superior rationality by recognizing that their present-biased preferences represent genuine aspects of their well-being that should be respected rather than corrected.

This principle has profound implications for how we conceptualize self-improvement and personal development. Traditional approaches to behavioral change often emphasize overcoming limitations and conforming to external standards of optimal behavior. The authenticity principle suggests that genuine improvement may instead involve understanding and working constructively with one's authentic preference structure, accepting certain apparent limitations as features rather than bugs of individual psychology.

The tension between authenticity and normative compliance appears across many domains of human behavior. In health, for example, individuals may be advised to adopt strict dietary regimens or exercise schedules that conflict with their natural preferences and rhythms. While such regimens may align with medical recommendations, our analysis suggests that approaches that work with rather than against individual preference structures may achieve better long-term outcomes and higher subjective well-being.

3.3. Implications for Behavioral Policy

The self-correction paradox has significant implications for the design of behavioral interventions, nudges, and choice architectures. Traditional behavioral policy assumes that interventions improve welfare by helping people overcome their biases and make choices that align with normative standards. Our findings suggest that this assumption requires careful reexamination.

Rather than pushing individuals toward theoretically optimal behavior, effective interventions might focus on helping people understand and work with their authentic preferences. This approach would emphasize preference clarification over preference correction, supporting individuals in making choices that genuinely reflect their values and priorities rather than external definitions of rationality. Such interventions might include tools for self-reflection, frameworks for understanding personal trade-offs, and mechanisms for implementing choices that align with authentic preferences.

The implications extend to specific policy domains. In retirement savings, for example, automatic enrollment and default contribution rates are typically designed to maximize long-term financial security according to normative benchmarks. Our analysis suggests that such defaults might be more effective if they were calibrated to individual preference structures rather than theoretical optima. This could involve providing individuals with tools to understand their authentic time preferences and then supporting choices that align with those preferences, even when they deviate from standard financial advice.

Similarly, in health behavior, interventions might focus on helping individuals find sustainable approaches to diet and exercise that work with rather than against their natural inclinations. Rather than promoting uniform standards of healthy behavior, such approaches would recognize that different individuals may achieve optimal well-being through different behavioral patterns that reflect their authentic preferences and constraints.

3.4. The Limits of Self-Control

Our findings also illuminate important limitations of self-control as a strategy for behavioral improvement. The model demonstrates that excessive self-control, represented by the choice λ = 1/β, can reduce welfare by creating internal conflict between decision-making processes and authentic preferences. This insight challenges the widespread assumption that more self-control is always better.

The results suggest that optimal self-regulation may involve knowing when not to regulate, recognizing that certain aspects of one's preference structure may be better accepted than changed. This perspective aligns with emerging research in psychology on the potential negative consequences of excessive self-control, including decision fatigue, psychological reactance, and reduced intrinsic motivation.

From a practical standpoint, these insights suggest that individuals seeking to improve their intertemporal choices should focus on understanding their authentic preferences rather than conforming to external standards of optimal behavior. This might involve experimenting with different approaches to find sustainable patterns that work with rather than against natural inclinations, accepting that some degree of present bias may be natural and not necessarily problematic.

3.5. Digital Interventions and Algorithm Design

The implications extend to the rapidly growing field of digital behavioral interventions, including apps and algorithms designed to improve financial, health, and educational outcomes. Many such tools are designed to counteract present bias by encouraging users to delay gratification and focus on long-term goals. Our analysis suggests that such interventions may be most effective when they help users understand and work with their authentic preferences rather than trying to eliminate those preferences.

This approach might involve developing personalized algorithms that adapt to individual preference structures rather than pushing all users toward uniform behavioral targets. Such systems could help users find approaches to goal achievement that align with their natural rhythms and inclinations, potentially improving both adherence and subjective well-being.

The findings also suggest caution regarding interventions that attempt to drastically reshape user behavior. Algorithms that push users too far from their authentic preferences may provoke disengagement or psychological resistance, ultimately undermining the intervention's effectiveness. More successful approaches might involve gradual, sustainable changes that respect individual preference structures while still supporting meaningful behavioral improvement.

3.6. Philosophical and Ethical Considerations

The self-correction paradox raises important philosophical and ethical questions about the goals of behavioral economics and the role of external authorities in defining optimal behavior. If perfect bias correction reduces individual welfare, then policies aimed at helping people overcome their biases may sometimes conflict to enhance well-being.

This tension highlights the importance of distinguishing between paternalistic interventions that impose external standards of rationality and libertarian approaches that support individual autonomy and preference satisfaction. Our findings suggest that effective behavioral policy may require a more nuanced understanding of when intervention is genuinely helpful versus when it may undermine individual welfare.

The results also speak to broader questions about human flourishing and the relationship between individual choice and social welfare. They suggest that diversity in behavioral patterns and preference structures may be valuable not just for individual well-being but also for social resilience and adaptation. Policies that promote uniform adherence to theoretical benchmarks may inadvertently reduce this beneficial diversity.

3.7. Future Research Directions

The self-correction paradox opens several important avenues for future research. Empirical studies are needed to test whether the theoretical predictions hold in real-world settings and to understand how individuals navigate the tension between authenticity and normative compliance. Laboratory experiments could examine how people respond to different types of behavioral interventions and whether approaches that emphasize preference understanding outperform those that focus on bias correction.

Longitudinal research could explore how the relationship between authenticity and welfare evolves, particularly as individuals gain experience with different self-regulation strategies. Cross-cultural studies could examine whether the authenticity principle holds across different cultural contexts with varying attitudes toward individual autonomy and collective standards.

From a theoretical perspective, future work could extend the basic model to incorporate uncertainty about preferences, learning over time, and social influences on individual choice. Such extensions could provide deeper insights into when and how the self-correction paradox manifests in more complex environments.

4. Conclusion

This paper demonstrates a fundamental paradox in behavioral self-correction that challenges core assumptions about the relationship between sophistication and welfare in economic decision-making. Through formal analysis of a three-period quasi-hyperbolic discounting model, I have shown that agents who perfectly neutralize their present bias achieve lower welfare than agents who make no metacognitive adjustment whatsoever. This counterintuitive finding emerges even though perfect correction successfully eliminates time inconsistency and achieves the normatively desirable goal of exponential discounting.

The self-correction paradox reveals a profound tension between two competing conceptions of rationality. Under normative rationality, agents should eliminate cognitive biases and conform to theoretical benchmarks of optimal behavior. Setting λ = 1/β achieves this goal perfectly, transforming decision weights to (1, δ, δ²) and ensuring complete time consistency. However, under subjective rationality, agents should maximize their authentic well-being as defined by their actual preference structure. This goal is achieved by setting λ = 1, corresponding to not adjust one's natural decision-making process.

The mathematical analysis confirms that these two objectives are fundamentally incompatible. An agent cannot simultaneously satisfy external standards of rational behavior and maximize their subjective welfare when that welfare is defined by present-biased preferences. The welfare function U₀(λ) reaches its unique maximum at λ = 1, demonstrating that authenticity, making choices that align with one's genuine preferences, can be more valuable than conformity to abstract rational ideals.

4.1. Theoretical Contributions

The research contributes to behavioral economics by revealing circumstances under which greater sophistication may reduce welfare. This finding challenges the widespread assumption that self-awareness and behavioral correction automatically improve outcomes. Instead, the analysis suggests that the relationship between sophistication and welfare depends critically on how welfare is defined and measured.

The model introduces a novel framework for analyzing metacognitive adjustment in intertemporal choice. By distinguishing between the decision criterion agents use (Ũ₀) and the welfare consequences they experience (U₀), the analysis illuminates how attempts at self-improvement can paradoxically reduce well-being. This framework could be extended to other domains where individuals attempt to correct perceived limitations in their decision-making.

From a philosophical perspective, the research highlights the importance of distinguishing between normative and descriptive approaches to welfare measurement. When we define welfare according to agents' authentic preferences, interventions that push behavior toward normative benchmarks may harm rather than help. This insight has implications for welfare economics more broadly and suggests the need for more nuanced approaches to policy evaluation.

4.2. Policy Implications

The findings have significant implications for the design of behavioral interventions, nudges, and choice architectures. Traditional behavioral policy assumes that helping people overcome their biases improves welfare, but our analysis suggests this assumption requires careful examination. Interventions that push individuals too far from their authentic preferences may reduce rather than enhance well-being, even when they achieve normatively desirable behavioral changes.

Effective behavioral policy may need to shift focus from bias correction to preference understanding. Rather than imposing external standards of optimal behavior, interventions might help individuals clarify their authentic preferences and make choices that align with those preferences. This approach would respect individual autonomy while still providing valuable support for decision-making.

The research also suggests the importance of personalization in behavioral interventions. Given that optimal adjustment strategies depend on individual preference structures, one-size-fits-all approaches may be less effective than tailored interventions that adapt to personal characteristics and authentic preferences. This insight is particularly relevant for digital behavioral interventions and algorithmic choice support systems.

4.3. Individual Self-Regulation

For individuals seeking to improve their intertemporal choices, the results suggest a more nuanced approach to self-regulation than typically advocated. Rather than attempting to eliminate all present bias, individuals might benefit from understanding and working with their authentic preference structures. This could involve finding sustainable approaches to goal achievement that respect natural inclinations while still supporting meaningful behavioral improvement.

The analysis highlights the potential dangers of excessive self-control. Forcing oneself to behave according to external standards of rationality may create internal conflict and reduce subjective well-being. Sometimes, the most sophisticated choice may be to accept certain apparent limitations as features rather than bugs of individual psychology.

These insights align with emerging research on sustainable behavior change, which emphasizes the importance of working with rather than against natural tendencies. Approaches that honor individual preference structures may achieve better long-term adherence and higher subjective well-being than those that attempt dramatic behavioral restructuring.

4.4. Broader Philosophical Implications

The self-correction paradox illuminates fundamental questions about human flourishing and the goals of economic analysis. It suggests that diversity in behavioral patterns and preference structures may be valuable not just for individual well-being but also for social resilience and adaptation. Policies that promote uniform adherence to theoretical benchmarks may inadvertently reduce this beneficial diversity.

The research also speaks to ongoing debates about paternalism and individual autonomy in behavioral economics. By demonstrating that bias correction can reduce welfare, the analysis provides support for libertarian approaches that emphasize individual choice and preference satisfaction over normative compliance. However, it also suggests the need for more sophisticated frameworks that can distinguish between beneficial and harmful forms of intervention.

At the deepest level, the findings challenge fundamental assumptions about the nature of rationality itself. They suggest that rationality should be defined relative to authentic preference structures rather than abstract theoretical ideals. Under this view, apparent "irrationality" may sometimes represent superior adaptation to individual circumstances and constraints.

4.5. Limitations and Future Research

The analysis relies on several simplifying assumptions that future research should address. The model assumes perfect knowledge of the adjustment mechanism and certainty about preference parameters. In reality, individuals may face uncertainty about both their authentic preferences and the effects of different adjustment strategies. Future work should explore how such uncertainty affects the self-correction paradox.

The three-period framework, while analytically convenient, may not capture longer-term dynamics such as learning and adaptation. Longitudinal research could examine how the relationship between authenticity and welfare evolves as individuals gain experience with different self-regulation strategies. Cross-cultural studies could explore whether the authenticity principle holds across different cultural contexts with varying attitudes toward individual autonomy.

Empirical validation of the theoretical predictions represents a crucial next step. Laboratory experiments could test whether people experience higher welfare when making choices that align with their authentic preferences versus when conforming to normative standards. Field studies could examine real-world behavioral interventions to determine whether approaches that emphasize preference understanding outperform those that focus on bias correction.

4.6. Final Reflections

The central insight emerging from this analysis is that authenticity in decision-making may sometimes be more valuable than conformity to external standards of rationality. This finding does not diminish the importance of self-awareness or behavioral sophistication, but rather suggests that these capabilities may be optimally directed toward understanding and working with authentic preferences rather than attempting to transcend them entirely.

The self-correction paradox reveals that the goals of behavioral economics may be more complex than previously understood. Rather than simply helping people make better choices according to theoretical benchmarks, the field might benefit from a renewed focus on helping individuals understand their authentic preferences and make choices that genuinely enhance their well-being according to their criteria.

This perspective suggests a humbler approach to behavioral intervention, one that recognizes the potential value of apparent irrationality and the dangers of excessive correction. It points toward a behavioral economics that respects individual diversity and authentic preference structures while still providing valuable insights for improving human decision-making.

In essence, the optimal correction for present bias may be no correction at all, a paradox that challenges fundamental assumptions about rationality and opens new avenues for understanding the complex relationship between self-awareness, behavioral choice, and human flourishing. The research suggests that sometimes the most rational choice is to remain authentically irrational, embracing the full complexity of human preferences rather than forcing them into the narrow confines of theoretical ideals.