Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

06 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Malaria control programmes across Africa and beyond are threatened by increasing insecticide resistance in the major anopheline vectors. In the malaria vectors Anopheles gambiae sensu lato, two point-mutations (L1014F and L1014S) in the voltage-dependent sodium channel gene that confer target-site knockdown resistance (kdr) to DDT and pyrethroid insecticides, have been described in several studies across the northern sudano-sahelian and the southern forested ecological zones of Cameroon. Contrarily, there is an unclear kdr status in anophelines of mountainous agro-ecosystems across the Cameroon Great-west domain. In order to determine the evolutionary profile of kdr alleles in An. gambiae and An. coluzzii sibling species both found in the Cameroon Great West domain, genotyping of the kdr locus on a total of 1172 individual specimen across five mountainous massifs, and sequencing on a minimum-size of 10 individuals per localities of a 510 base pairs fragment of the downstream exon-20, were performed. Knockdown resistance 1014F allele was found to be widespread with An. gambiae having high frequencies compared to An. coluzzii. Meanwhile 1014S-kdr allele was confined in An. gambiae populations. The results suggest that kdr alleles may have arisen through introgression. Estimates of genetic variability provided evidence of selection acting on these alleles, particularly the 1014F which was driven to fixation. Spatial occurrence of 1014F was heterogenous, being seemingly influenced by land elevation and gene flow. This study delineates the comprehensive distribution of kdr mutations in An. gambiae and An. coluzzii across Cameroonian mountainous ecosystems. Taking action to limit the spread of kdr alleles into mountainous landscapes would be helpful for the management and sustainability of malaria vector control.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

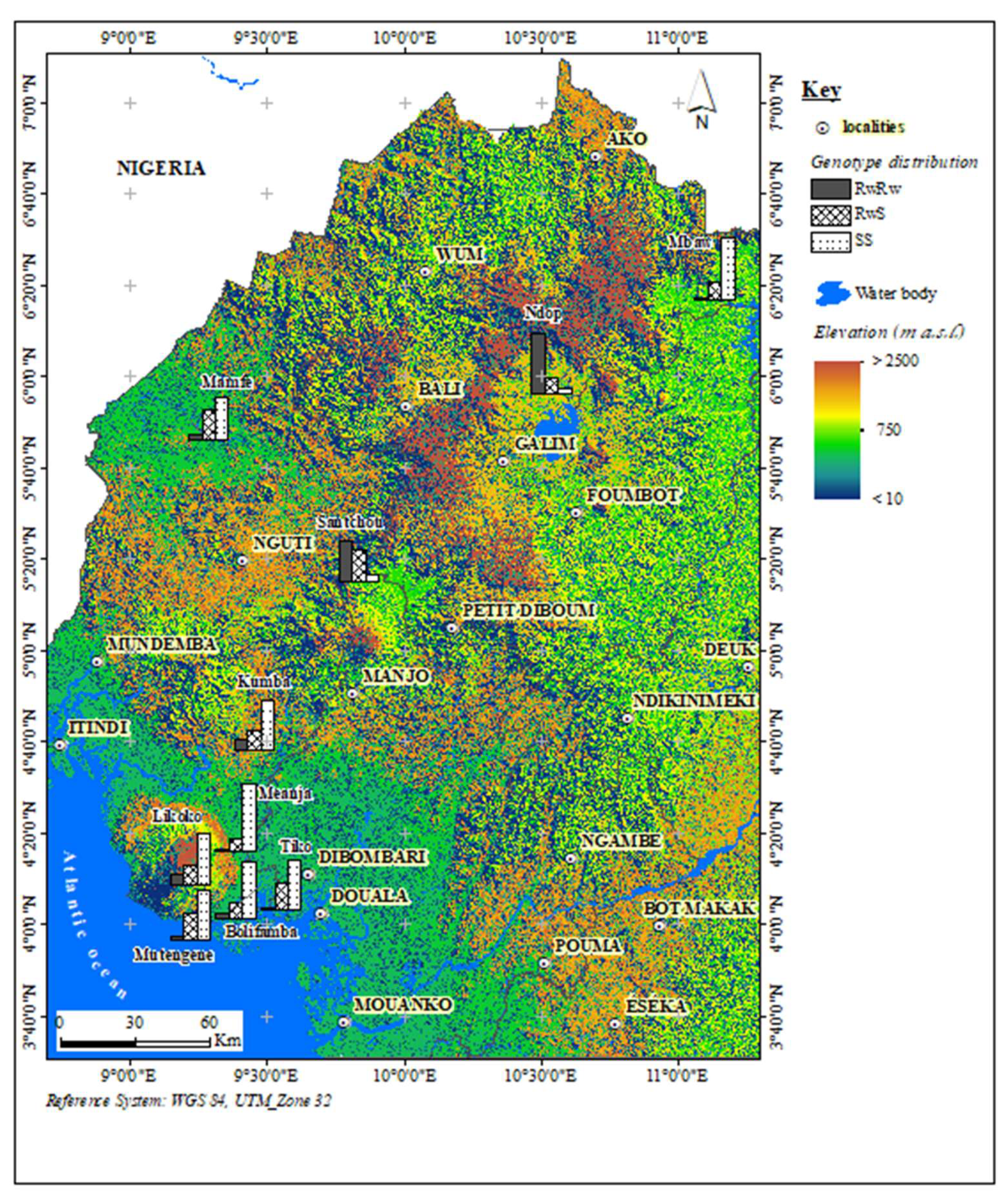

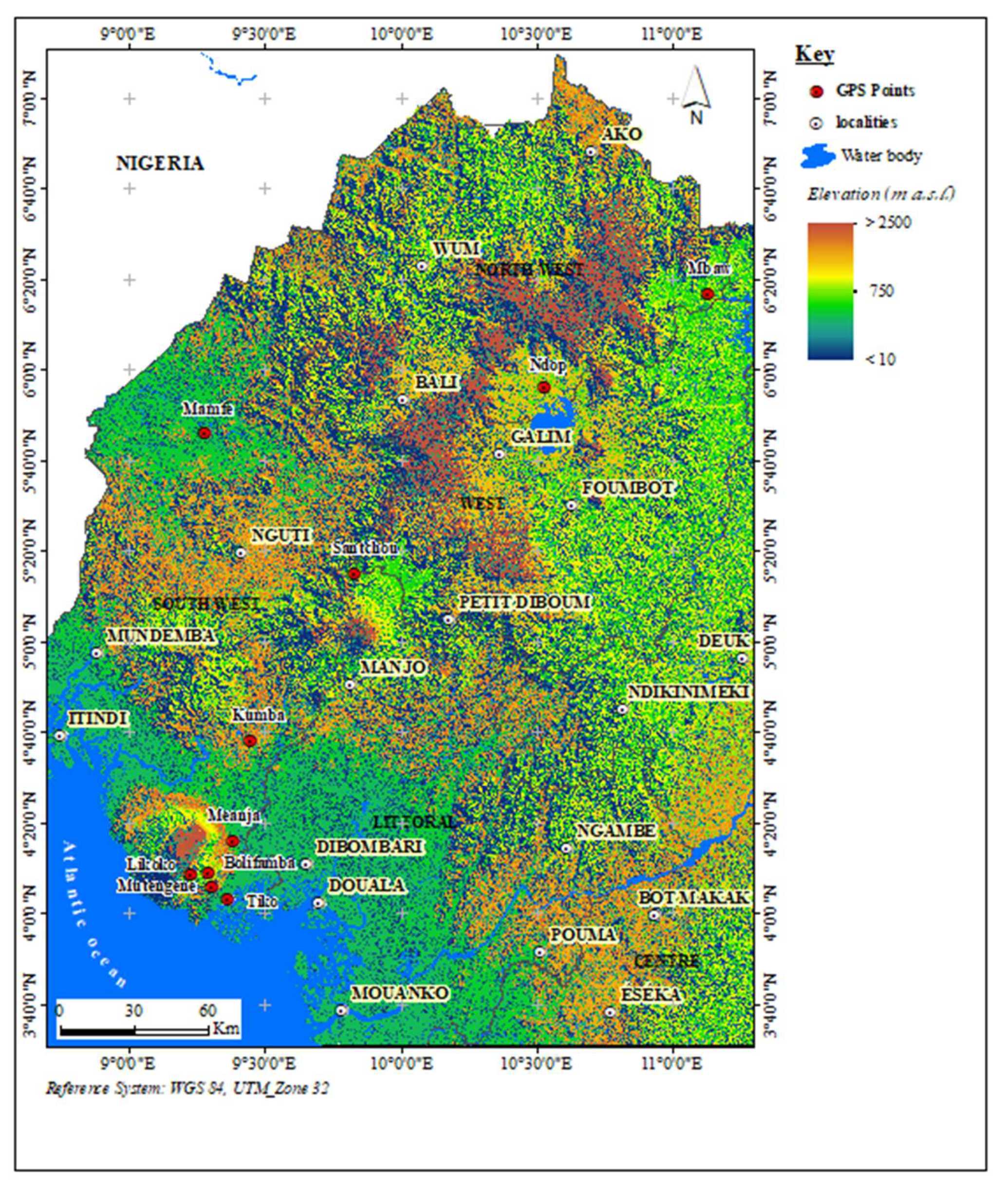

2.1. Study Sites and Sampling

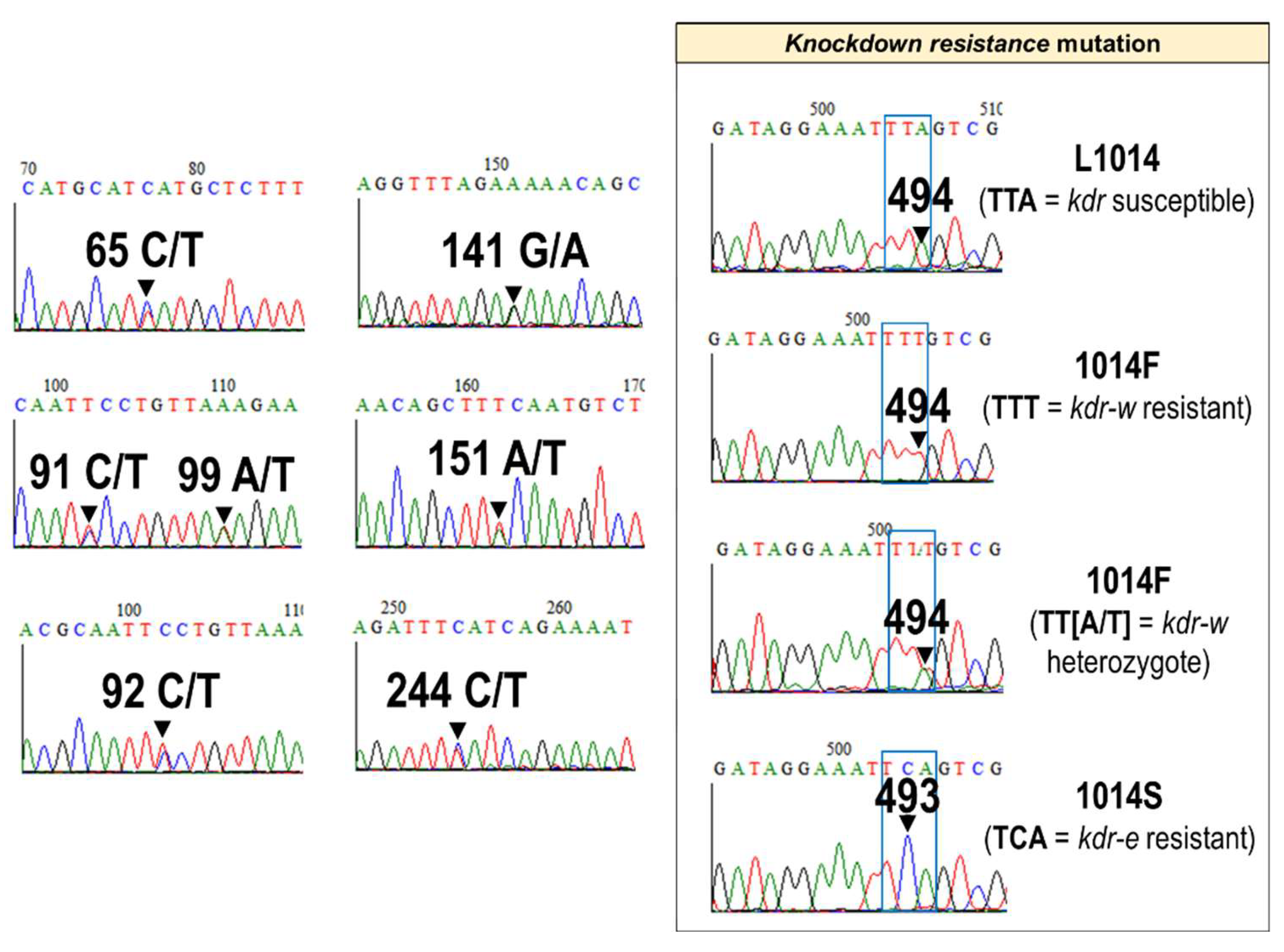

2.2. Genotyping of the kdr Gene Mutation

2.3. Amplification and Sequencing of the Downstream Exon-20 Region of the VGSC Gene

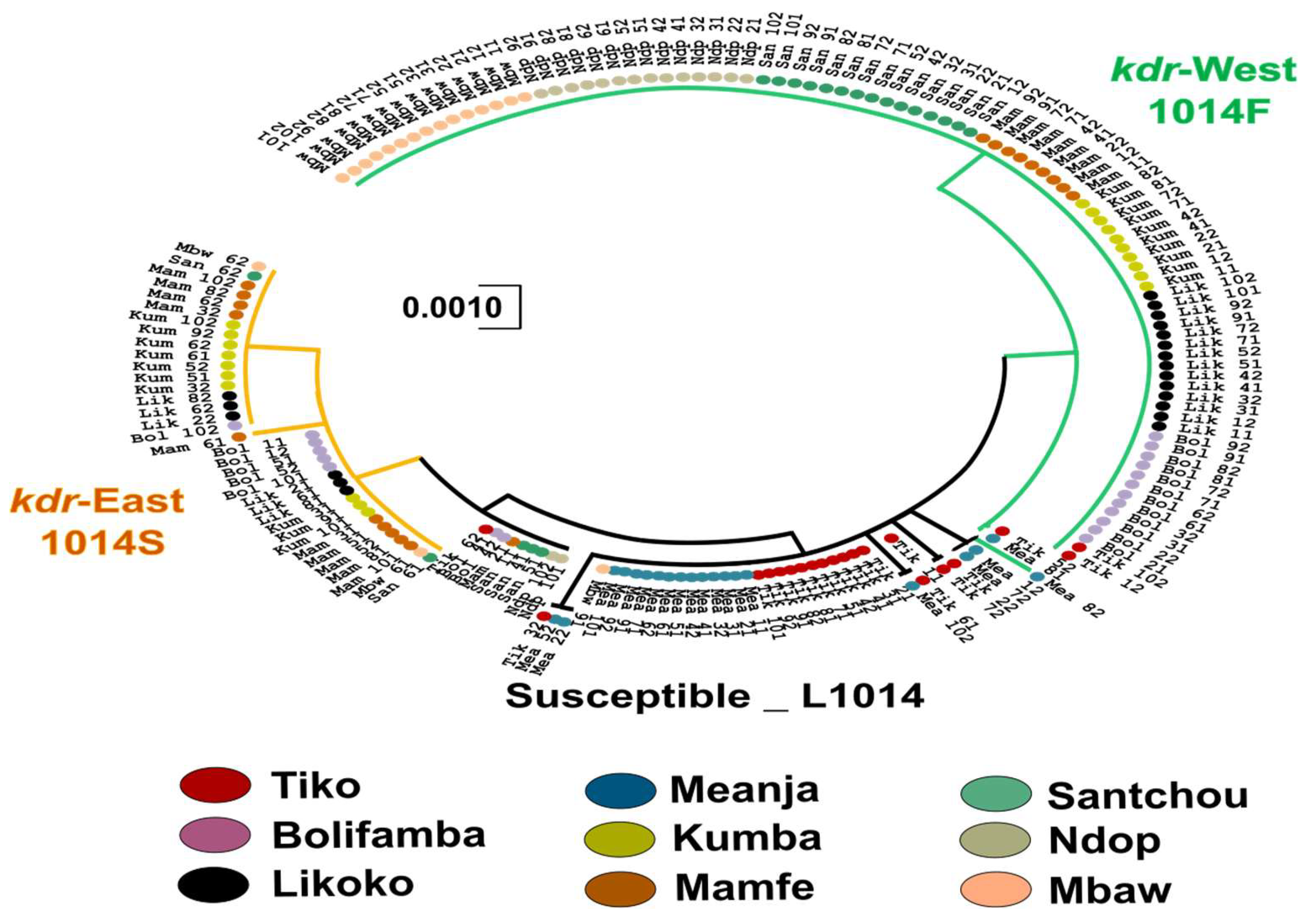

2.4. Phylogenetic Structure Analysis of the Studied Species

3. Results

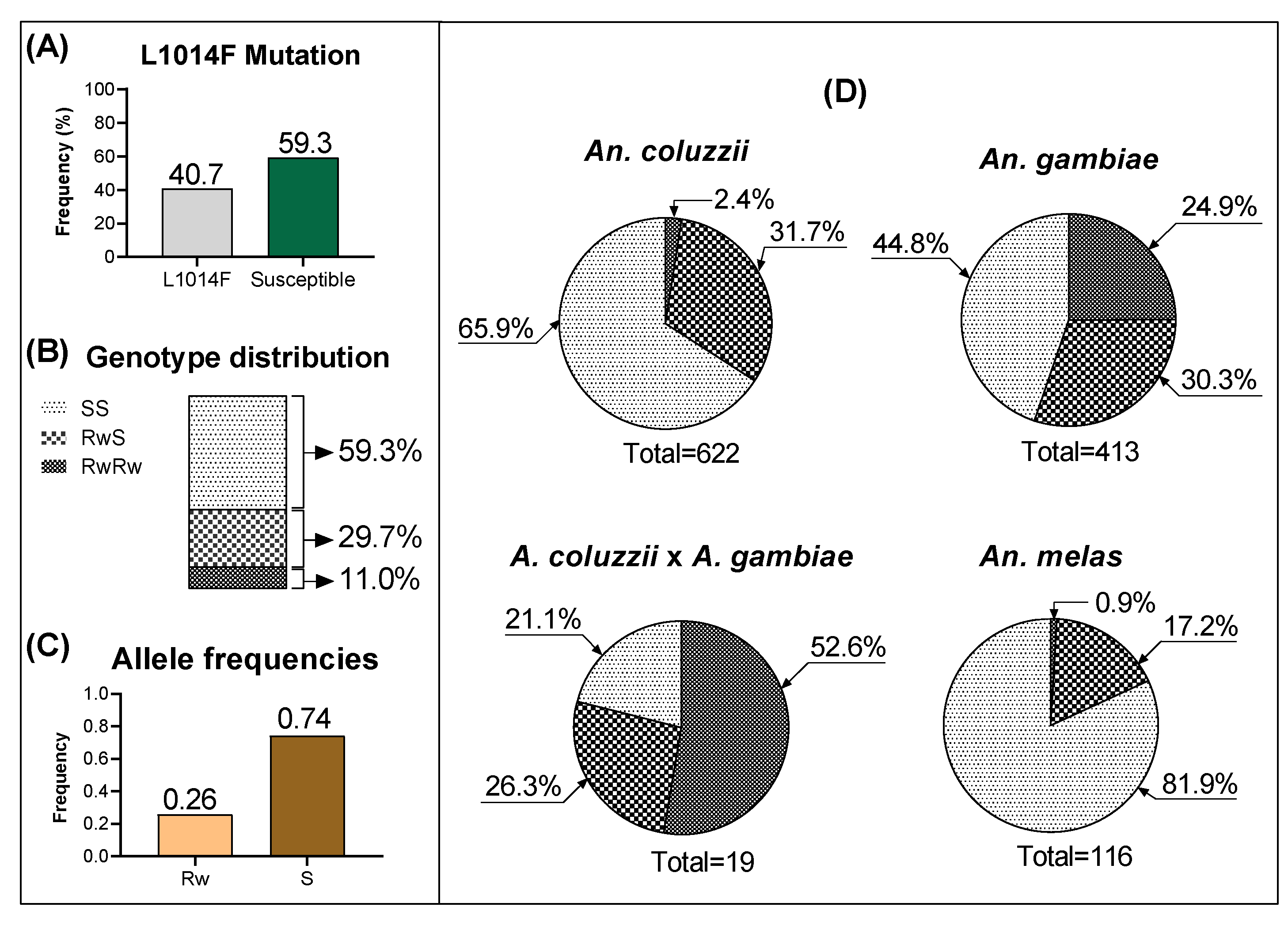

3.1. Frequency and Distribution of kdr Mutations

3.2. Nucleotide Polymorphisms in An. gambiae and An. coluzzii Exon-20 Region of the VGSC Gene

| Samples | N | S | h (Hd) | Syn | NSyn | π (k) | D | F* | |

| Anopheles species ID | |||||||||

| An. Coluzzii | 40 | 6 | 9 (0.61) | 0 | 1 (kdr-W) | 0.002 (0.85) | - 1.07ns | - 0.58ns | |

| An. Gambiae | 134 | 5 | 6 (0.53) | 0 | 2 (kdr-W, kdr-E) | 0.002 (1.09) | 0.41ns | - 0.78ns | |

| kdr Allelic profile | |||||||||

| L1014 | 44 | 5 | 6 (0.61) | 0 | 0 | 0.001(0.73) | - 0.91ns | 0.57ns | |

| 1014F | 94 | 2 | 3 (0.06) | 0 | 0 | 0.0002 (0.08) | - 1.22ns | - 1.29ns | |

| 1014S | 36 | 2 | 3 (0.54) | 0 | 0 | 0.001 (0.57) | 0.35ns | - 0.54ns | |

| Mountain massif | localities | ||||||||

| Mount Cameroon | Tiko | 20 | 5 | 7 (0.64) | 0 | 1 (kdr-W) | 0.002 (0.93) | - 1.05ns | - 0.68ns |

| Kumba | 20 | 3 | 3 (0.64) | 1 | 1 (kdr-E) | 0.003 (1.53) | 2.17* | 1.52ns | |

| Meanja | 20 | 4 | 6 (0.58) | 0 | 1 (kdr-W) | 0.001 (0.75) | - 0.97ns | - 0.17ns | |

| Bolifamba | 20 | 3 | 4 (0.60) | 0 | 2 (kdr-W, kdr-E) | 0.002 (1.05) | 0.63ns | 0.09ns | |

| Likoko | 20 | 3 | 3 (0.49) | 1 | 1 (kdr-E) | 0.002 (1.15) | 0.97ns | 1.15ns | |

| ALL | 100 | 8 | 11 (0.77) | 0 | 2 | 0.003 (1.70) | 0.24ns | 1.08ns | |

| Western Highlands | Mamfe | 20 | 4 | 5 (0.73) | 0 | 2 (kdr-W, kdr-E) | 0.003 (1.48) | 0.92ns | 0.44ns |

| Mount Oku | Mbaw plain | 18 | 4 | 4 (0.31) | 0 | 2 (kdr-W, kdr-E) | 0.001 (0.73) | - 1.13ns | - 0.94ns |

| Kupe Manengoumba | Santchou | 20 | 3 | 4 (0.43) | 0 | 2 (kdr-W, kdr-E) | 0.001 (0.68) | - 0.51ns | - 0.26ns |

| Mount Bamboutos | Ndop | 16 | 1 | 2 (0.23) | 0 | 1 (kdr-W) | 0.0005 (0.23) | - 0.45ns | 0.45ns |

| ALL | 174 | 9 | 12 (0.68) | 0 | 2 | 0.003 (1.48) | - 0.14ns | 0.30ns | |

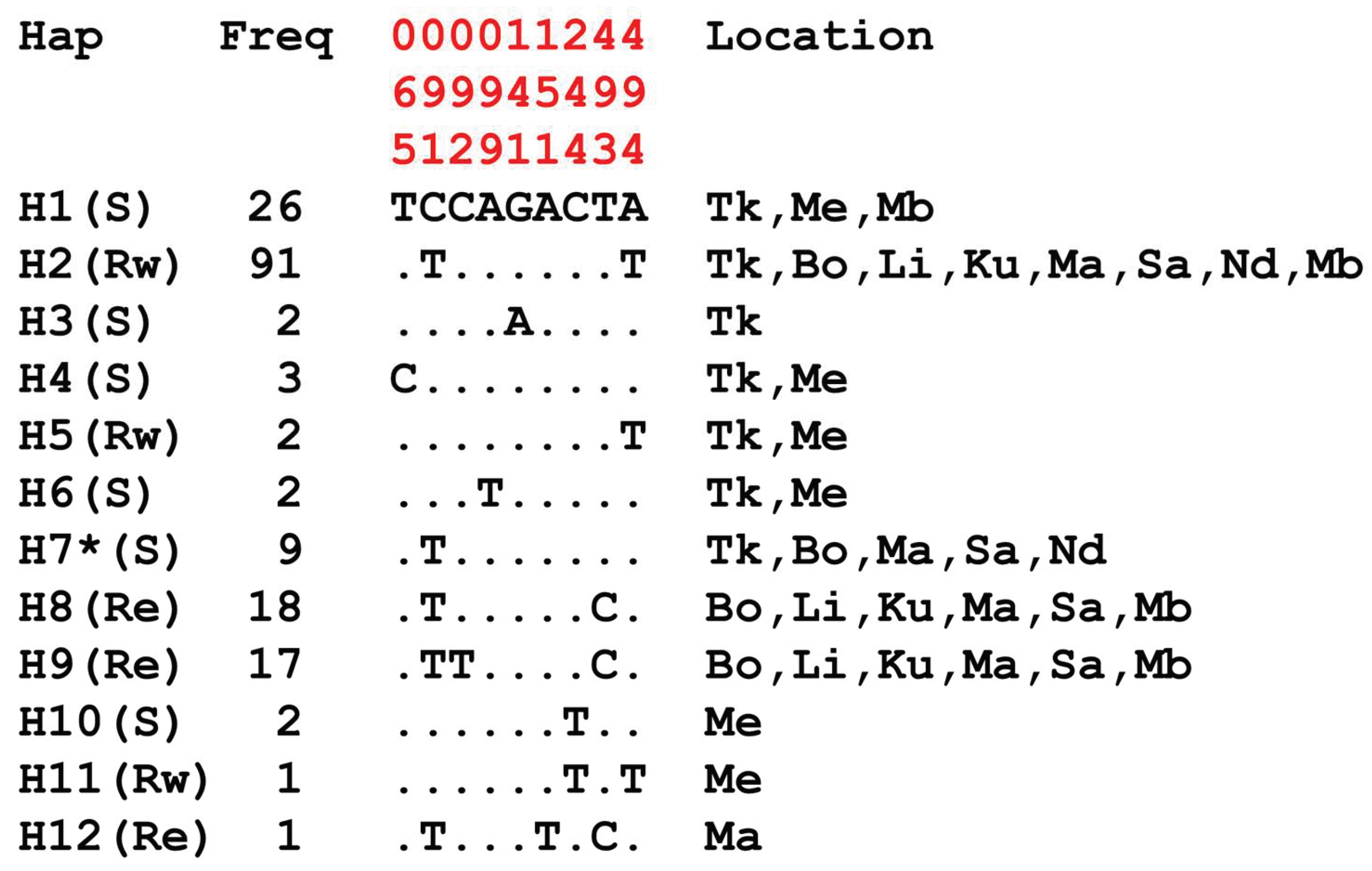

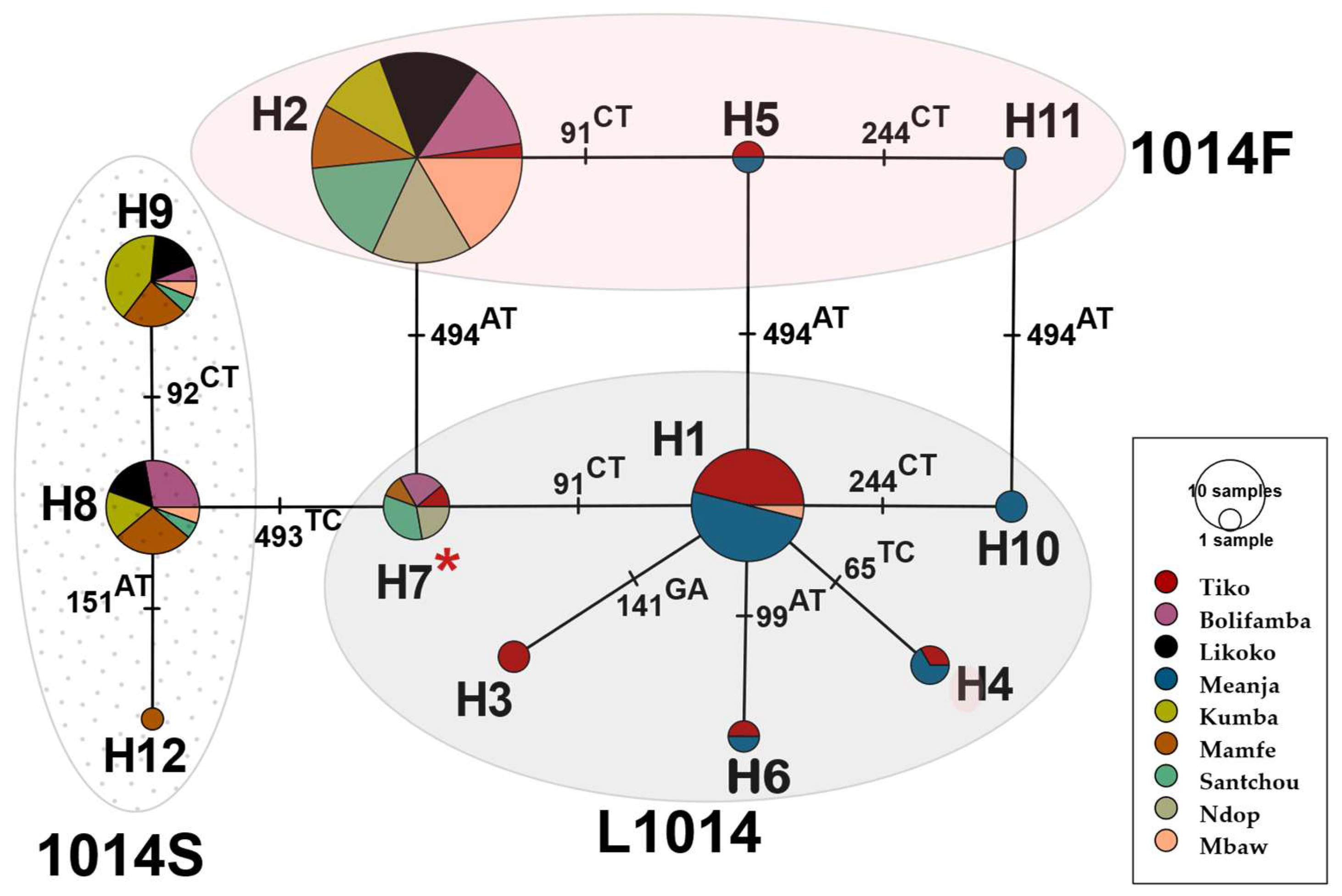

3.3. Genetic Variability and Haplotype Network of An. gambiae and An. coluzzii VGSC Gene

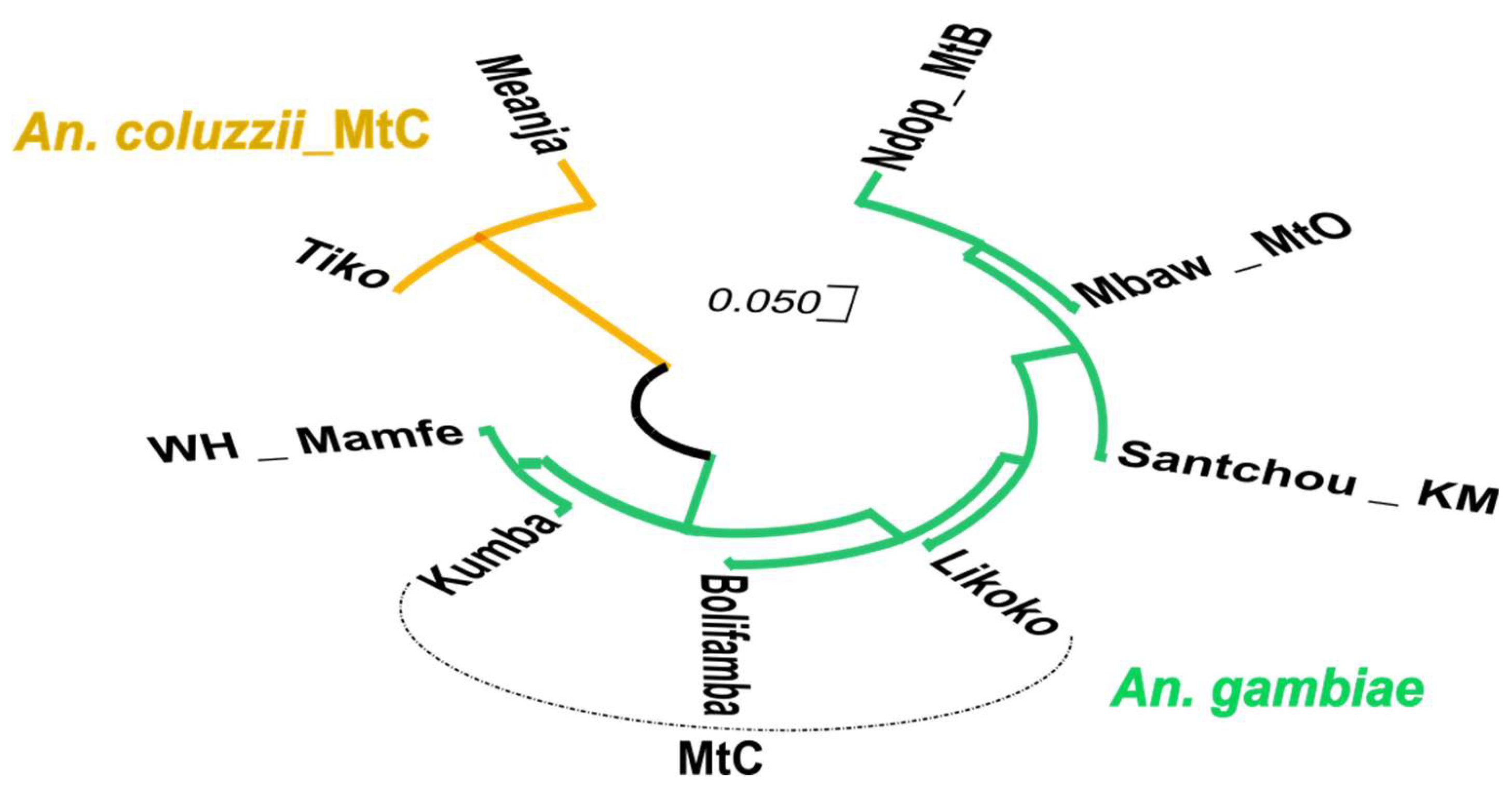

3.4. Phylogenetic Relationship Between Exon-20 kdr Haplotypes

4. Discussion

- Distribution of target-site insensitivity mutations

- Sequence analysis and Genetic variability patterns of the 510bp fragment in exon-20 region of kdr locus

- Genetic differentiation based on exon-20 region of the VGSC gene in An. coluzzii and An. gambiae populations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DDT | Dichloro Diphenyl Trichloroethane |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| IRS | Indoor Residual Spraying |

| ITNs | Insecticide Treated Nets |

| kdr | Knockdown resistance |

| LLINs | Long Lasting Insecticidal Nets |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| VGSC | Voltage Gated Sodium Channel |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Haplotype Diversity Patterns of the 510bp Fragment in Exon-20 Region of the VGSC Gene

References

- Tizifa, T.A.; Kabaghe, A.N.; McCann, R.S.; Van den Berg, H.; Van Vugt, M.;Phiri, K.S. Prevention Efforts for Malaria. Curr Trop Med Rep, 2018. 5(1): p. 41-50. [CrossRef]

- Lobo, N.F.; Achee, N.L.; Greico, J.;Collins, F.H. Modern Vector Control. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2018. 8(1): p. a025643. [CrossRef]

- WHO, World Malaria Report. 2021, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 322.

- Brogdon, W.G.;McAllister, J.C. Insecticide resistance and vector control. Emerg Infect Dis, 1998. 4(4): p. 605-613. [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.; Tomlinson, S.; Kleinschmidt, I.; Donnelly, M.J.; Akogbeto, M.; Adechoubou, A.; Massougbodji, A.; Okê-Sopoh, M.; Corbel, V.; Cornelie, S.; Hounto, A.; Etang, J.; Awono-Ambene, H.P.; Bigoga, J.; Mandeng, S.E.; Njeambosay, B.; Tabue, R.; Kouambeng, C.; Fondjo, E.; Raghavendra, K.; Bhatt, R.M.; Chourasia, M.K.; Swain, D.K.; Uragayala, S.; Valecha, N.; Mbogo, C.; Bayoh, N.; Kinyari, T.; Njagi, K.; Muthami, L.; Kamau, L.; Mathenge, E.; Ochomo, E.; Kafy, H.T.; Bashir, A.I.; Malik, E.M.; Elmardi, K.; Sulieman, J.E.; Abdin, M.; Subramaniam, K.; Thomas, B.; West, P.; Bradley, J.; Knox, T.B.; Mnzava, A.P.; Lines, J.; Macdonald, M.; Nkuni, Z.J.;Implications of Insecticide Resistance, C. Implications of insecticide resistance for malaria vector control with long-lasting insecticidal nets: trends in pyrethroid resistance during a WHO-coordinated multi-country prospective study. Parasit Vectors, 2018. 11(1): p. 550. [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, H.; da Silva Bezerra, H.S.; Al-Eryani, S.; Chanda, E.; Nagpal, B.N.; Knox, T.B.; Velayudhan, R.;Yadav, R.S. Recent trends in global insecticide use for disease vector control and potential implications for resistance management. Sci Rep, 2021. 11(1): p. 23867. [CrossRef]

- Knox, T.B.; Juma, E.O.; Ochomo, E.O.; Pates Jamet, H.; Ndungo, L.; Chege, P.; Bayoh, N.M.; N’Guessan, R.; Christian, R.N.; Hunt, R.H.;Coetzee, M. An online tool for mapping insecticide resistance in major Anopheles vectors of human malaria parasites and review of resistance status for the Afrotropical region. Parasit Vectors, 2014. 7(1): p. 76. [CrossRef]

- Karaağaç, S., Insecticide Resistance, in Insecticides - Advances in Integrated Pest Management, F. Perveen, Editor. 2012, In Tech. p. 469-478.

- Clark, J.;Yamaguchi, I., Scope and status of pesticide resistance, in Agrochemical resistance. 2002, American Chemical Society: Washington DC. p. 1-22.

- Whalon, M.; Mota-Sanchez, D.;Hollingworth, R., Analysis of global pesticide resistance in arthropods, in Global pesticide resistance in arthropods, M. Whalon, D. Mota-Sanchez, and R. Hollingworth, Editors. 2008, CABI. p. 5-31.

- Ishaaya, I. Novel insecticides: Modes of action and resistance mechanism. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol, 2005. 58(4): p. 191-191. [CrossRef]

- Siviter, H.;Muth, F. Do novel insecticides pose a threat to beneficial insects? Proc R Soc B-Biol Sci, 2020. 287(1935): p. 20201265. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Torres, D.; Chandre, F.; Williamson, M.S.; Darriet, F.; Bergé, J.B.; Devonshire, A.L.; Guillet, P.; Pasteur, N.;Pauron, D. Molecular characterization of pyrethroid knockdown resistance (kdr) in the major malaria vector Anopheles gambiae s.s. Insect Mol Biol, 1998. 7(2): p. 179-84. [CrossRef]

- Weedall, G.; Mugenzi, L.; Menze, B.; Tchouakui, M.; Ibrahim, S.; Amvongo-Adjia, N.; Irving, H.; Wondji, M.; Tchoupo, M.; Djouaka, R.; Riveron, J.;Wondji, C. A cytochrome P450 allele confers pyrethroid resistance on a major African malaria vector, reducing insecticide-treated bednet efficacy. Sci Transl Med, 2019. 11: p. eaat7386. [CrossRef]

- Tchouakui, M.; Chiang, M.-C.; Ndo, C.; Kuicheu, C.; Amvongo-Adjia, N.; Wondji, M.; Tchoupo, M.; Kusimo, M.; Riveron, J.;Wondji, C. A marker of glutathione S-transferase-mediated resistance to insecticides is associated with higher Plasmodium infection in the African malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Sci Rep, 2019. 9: p. 5772. [CrossRef]

- Bass, C.; Nikou, D.; Vontas, J.; Donnelly, M.J.; Williamson, M.S.;Field, L.M. The Vector Population Monitoring Tool (VPMT): High-Throughput DNA-Based Diagnostics for the Monitoring of Mosquito Vector Populations. Malaria Research and Treatment, 2010. 2010: p. 190434-190434. [CrossRef]

- Lui, N. Insecticides resistance in mosquitoes: impact, mechanisms, and research directions. Annu Rev Entomol, 2015. 60: p. 537-59. [CrossRef]

- Riveron, J.; Tchouakui, M.; Mugenzi, L.; Menze, B.; Chiang, M.-C.;Wondji, C., Insecticide Resistance in Malaria Vectors: An Update at a Global Scale, in Towards Malaria Elimination - A Leap Forward, S. Manguin and V. Dev, Editors. 2018, IntechOpen.

- Khan, S.; Uddin, M.N.; Rizwan, M.; Khan, W.; Farooq, M.; Sattar Shah, A.; Subhan, F.; Aziz, F.; Rahman, K.U.; Khan, A.; Ali, S.;Muhammad, M. Mechanism of Insecticide Resistance in Insects/Pests. Pol J Environ Stud, 2020. 29(3): p. 2023-2030. [CrossRef]

- Ffrench-Constant, R.; Pittendrigh, B.; Vaughan, A.;Anthony, N. Why are there so few resistance-associated mutations in insecticide target genes? Phil Trans R Soc B, Biol Sci, 1998. 353(1376): p. 1685-1693. [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.;Valle, D., The Pyrethroid Knockdown Resistance, in Insecticides - Basic and Other Applications, S. Soloneski, Editor. 2012, InTech. p. 17-38.

- WHO, Safety of pyrethroids for public health use. 2005, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 1-69.

- Saillenfait, A.M.; Ndiaye, D.;Sabaté, J.P. Pyrethroids: exposure and health effects _ an update. Int J Hyg Environ Health, 2015. 218(3): p. 281-292. [CrossRef]

- Ujihara, K. The history of extensive structural modifications of pyrethroids. J Pestic Sci, 2019. 44(4): p. 215-224. [CrossRef]

- Goldin, A.L.; Barchi, R.L.; Caldwell, J.H.; Hofmann, F.; Howe, J.R.; Hunter, J.C.; Kallen, R.G.; Mandel, G.; Meisler, M.H.; Netter, Y.B.; Noda, M.; Tamkun, M.M.; Waxman, S.G.; Wood, J.N.;Catterall, W.A. Nomenclature of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron, 2000. 28(2): p. 365-8. [CrossRef]

- Ffrench-Constant, R.H.; Daborn, P.J.;Le Goff, G. The genetics and genomics of insecticide resistance. Trends Genet, 2004. 20(3): p. 163-70. [CrossRef]

- Ranson, H.; Jensen, B.; Vulule, J.M.; Wang, X.; Hemingway, J.;Collins, F.H. Identification of a point mutation in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene of Kenyan Anopheles gambiae associated with resistance to DDT and pyrethroids. Insect Mol Biol, 2000. 9(5): p. 491-7. [CrossRef]

- Lynd, A.; Oruni, A.; van’t Hof, A.E.; Morgan, J.C.; Naego, L.B.; Pipini, D.; O’Kines, K.A.; Bobanga, T.L.; Donnelly, M.J.;Weetman, D. Insecticide resistance in Anopheles gambiae from the northern Democratic Republic of Congo, with extreme knockdown resistance (kdr) mutation frequencies revealed by a new diagnostic assay. Malar J, 2018. 17(1): p. 412. [CrossRef]

- Dabiré, R.K.; Namountougou, M.; Diabaté, A.; Soma, D.D.; Bado, J.; Toé, H.K.; Bass, C.;Combary, P. Distribution and Frequency of kdr Mutations within Anopheles gambiae s.l. Populations and First Report of the Ace.1G119S Mutation in Anopheles arabiensis from Burkina Faso (West Africa). PLoS ONE, 2014. 9(7): p. e101484. [CrossRef]

- Gueye, O.K.; Tchouakui, M.; Dia, A.K.; Faye, M.B.; Ahmed, A.A.; Wondji, M.J.; Nguiffo, D.N.; Mugenzi, L.M.J.; Tripet, F.; Konaté, L.; Diabate, A.; Dia, I.; Gaye, O.; Faye, O.; Niang, E.H.A.;Wondji, C.S. Insecticide Resistance Profiling of Anopheles coluzzii and Anopheles gambiae Populations in the Southern Senegal: Role of Target Sites and Metabolic Resistance Mechanisms. Genes, 2020. 11(12): p. 1403. [CrossRef]

- Koukpo, C.Z.; Fassinou, A.J.Y.H.; Ossè, R.A.; Agossa, F.R.; Sovi, A.; Sewadé, W.T.; Aboubakar, S.; Assogba, B.S.; Akogbeto, M.C.;Sezonlin, M. The current distribution and characterization of the L1014F resistance allele of the kdr gene in three malaria vectors (Anopheles gambiae, Anopheles coluzzii, Anopheles arabiensis) in Benin (West Africa). Malar J, 2019. 18(1): p. 175. [CrossRef]

- Antonio-Nkondjio, C.; Ndo, C.; Njiokou, F.; Bigoga, J.; Awono-Ambene, H.; Etang, J.; Ekobo, A.S.;Wondji, C. Review of malaria situation in Cameroon: technical viewpoint on challenges and prospects for disease elimination. Parasit Vectors, 2019. 12(1): p. 501. [CrossRef]

- Verhaeghen, K.; Van Bortel, W.; Roelants, P.; Backeljau, T.;Coosemans, M. Detection of the East and West African kdr mutation in Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles arabiensis from Uganda using a new assay based on FRET/Melt Curve analysis. Malar J, 2006. 5(1): p. 16. [CrossRef]

- Hemming-Schroeder, E.; Strahl, S.; Yang, E.; Nguyen, A.; Lo, E.; Zhong, D.; Atieli, H.; Githeko, A.;Yan, G. Emerging Pyrethroid Resistance among Anopheles arabiensis in Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2018. 98(3): p. 704-709. [CrossRef]

- Chandre, F.; Manguin, S.; Brengues, C.; Dossou Yovo, J.; Darriet, F.; Diabate, A.; Carnevale, P.;Guillet, P. Current distribution of a pyrethroid resistance gene (kdr) in Anopheles gambiae complex from west Africa and further evidence for reproductive isolation of the Mopti form. Parassitologia, 1999. 41(1-3): p. 319-22.

- Gentile, G.; Santolamazza, F.; Fanello, C.; Petrarca, V.; Caccone, A.;della Torre, A. Variation in an intron sequence of the voltage-gated sodium channel gene correlates with genetic differentiation between Anopheles gambiae s.s. molecular forms. Insect Mol Biol, 2004. 13(4): p. 371-7. [CrossRef]

- della Torre, A.; Tu, Z.;Petrarca, V. On the distribution and genetic differentiation of Anopheles gambiae s.s. molecular forms. Insect Biochem Mol Biol, 2005. 35(7): p. 755-69. [CrossRef]

- Santolamazza, F.; Caputo, B.; Nwakanma, D.C.; Fanello, C.; Petrarca, V.; Conway, D.J.; Weetman, D.; Pinto, J.; Mancini, E.;della Torre, A. Remarkable diversity of intron-1 of the para voltage-gated sodium channel gene in an Anopheles gambiae/Anopheles coluzzii hybrid zone. Malar J, 2015. 14(1): p. 9. [CrossRef]

- Etang, J.; Fondjo, E.; Chandre, F.; Morlais, I.; Brengues, C.; Nwane, P.; Chouaibou, M.; Ndjemai, H.;Simard, F. First report of knockdown mutations in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae from Cameroon. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2006. 74(5): p. 795-7.

- Ndjemaï, H.N.M.; Patchoké, S.; Atangana, J.; Etang, J.; Simard, F.; Bilong Bilong, C.F.; Reimer, L.; Cornel, A.; Lanzaro, G.C.;Fondjo, E. The distribution of insecticide resistance in Anopheles gambiae s.l. populations from Cameroon: an update. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg, 2009. 103(11): p. 1127-1138. [CrossRef]

- Nwane, P.; Etang, J.; Chouaїbou, M.; Toto, J.C.; Mimpfoundi, R.;Simard, F. Kdr-based insecticide resistance in Anopheles gambiae s.s populations in Cameroon: spread of the L1014F and L1014S mutations. BMC Res Notes, 2011. 4(1): p. 463. [CrossRef]

- Nwane, P.; Etang, J.; Chouaibou, M.; Toto, J.C.; Koffi, A.; Mimpfoundi, R.;Simard, F. Multiple insecticide resistance mechanisms in Anopheles gambiae s.l. populations from Cameroon, Central Africa. Parasit Vectors, 2013. 6: p. 41. [CrossRef]

- Fadel, A.N.; Ibrahim, S.S.; Tchouakui, M.; Terence, E.; Wondji, M.J.; Tchoupo, M.; Wanji, S.;Wondji, C.S. A combination of metabolic resistance and high frequency of the 1014F kdr mutation is driving pyrethroid resistance in Anopheles coluzzii population from Guinea savanna of Cameroon. Parasit Vectors, 2019. 12(1): p. 263. [CrossRef]

- Mandeng, S.E.; Awono-Ambene, H.P.; Bigoga, J.D.; Ekoko, W.E.; Binyang, J.; Piameu, M.; Mbakop, L.R.; Fesuh, B.N.; Mvondo, N.; Tabue, R.; Nwane, P.; Mimpfoundi, R.; Toto, J.C.; Kleinschmidt, I.; Knox, T.B.; Mnzava, A.P.; Donnelly, M.J.; Fondjo, E.;Etang, J. Spatial and temporal development of deltamethrin resistance in malaria vectors of the Anopheles gambiae complex from North Cameroon. PLoS ONE, 2019. 14(2): p. e0212024. [CrossRef]

- Bamou, R.; Sonhafouo-Chiana, N.; Mavridis, K.; Tchuinkam, T.; Wondji, C.S.; Vontas, J.;Antonio-Nkondjio, C. Status of Insecticide Resistance and Its Mechanisms in Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles coluzzii Populations from Forest Settings in South Cameroon. Genes, 2019. 10(10): p. 741. [CrossRef]

- Antonio-Nkondjio, C.; Tene Fossog, B.; Kopya, E.; Poumachu, Y.; Menze Djantio, B.; Ndo, C.; Tchuinkam, T.; Awono-Ambene, P.;Wondji, C.S. Rapid evolution of pyrethroid resistance prevalence in Anopheles gambiae populations from the cities of Douala and Yaoundé (Cameroon). Malar J, 2015. 14(1): p. 155. [CrossRef]

- Piameu, M.; Nwane, P.; Toussile, W.; Mavridis, K.; Wipf, N.C.; Kouadio, P.F.; Mbakop, L.R.; Mandeng, S.; Ekoko, W.E.; Toto, J.C.; Ngaffo, K.L.; Ngo Etounde, P.K.; Ngantchou, A.T.; Chouaibou, M.; Müller, P.; Awono-Ambene, P.; Vontas, J.;Etang, J. Pyrethroid and Etofenprox Resistance in Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles coluzzii from Vegetable Farms in Yaoundé, Cameroon: Dynamics, Intensity and Molecular Basis. Molecules, 2021. 26(18). [CrossRef]

- Bamou, R.; Kopya, E.; Nkahe, L.D.; Menze, B.D.; Awono-Ambene, P.; Tchuinkam, T.; Njiokou, F.; Wondji, C.S.;Antonio-Nkondjio, C. Increased prevalence of insecticide resistance in Anopheles coluzzii populations in the city of Yaoundé, Cameroon and influence on pyrethroid-only treated bed net efficacy. Parasite, 2021. 28: p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Santolamazza, F.; Calzetta, M.; Etang, J.; Barrese, E.; Dia, I.; Caccone, A.; Donnelly, M.J.; Petrarca, V.; Simard, F.; Pinto, J.;della Torre, A. Distribution of knock-down resistance mutations in Anopheles gambiae molecular forms in west and west-central Africa. Malar J, 2008. 7: p. 74-74. [CrossRef]

- Yougang, A.P.; Kamgang, B.; Bahun, T.A.W.; Tedjou, A.N.; Nguiffo-Nguete, D.; Njiokou, F.;Wondji, C.S. First detection of F1534C knockdown resistance mutation in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) from Cameroon. Infect Dis Poverty, 2020. 9(1): p. 152. [CrossRef]

- Talipouo, A.; Mavridis, K.; Nchoutpouen, E.; Djiappi-Tchamen, B.; Fotakis, E.A.; Kopya, E.; Bamou, R.; Kekeunou, S.; Awono-Ambene, P.; Balabanidou, V.; Balaska, S.; Wondji, C.S.; Vontas, J.;Antonio-Nkondjio, C. High insecticide resistance mediated by different mechanisms in Culex quinquefasciatus populations from the city of Yaoundé, Cameroon. Sci Rep, 2021. 11(1): p. 7322-7322. [CrossRef]

- Djiappi-Tchamen, B.; Nana-Ndjangwo, M.S.; Mavridis, K.; Talipouo, A.; Nchoutpouen, E.; Makoudjou, I.; Bamou, R.; Mayi, A.M.; Awono-Ambene, P.; Tchuinkam, T.; Vontas, J.;Antonio-Nkondjio, C. Analyses of Insecticide Resistance Genes in Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus Mosquito Populations from Cameroon. Genes, 2021. 12(6). [CrossRef]

- Amvongo-Adjia, N.; Wirsiy, E.; Riveron, J.; Ndongmo, W.; Enyong, P.; Njiokou, F.; Wondji, C.;Wanji, S. Bionomics and vectorial role of anophelines in wetlands along the volcanic chain of Cameroon. Parasit Vectors, 2018. 11(1): p. 471-471. [CrossRef]

- Amvongo-Adjia, N.; Riveron, J.M.; Njiokou, F.; Wanji, S.;Wondji, C.S. Influence of a Major Mountainous Landscape Barrier (Mount Cameroon) on the Spread of Metabolic (GSTe2) and Target-Site (Rdl) Resistance Alleles in the African Malaria Vector Anopheles funestus. Genes, 2020. 11(12). [CrossRef]

- Barnes, K.G.; Irving, H.; Chiumia, M.; Mzilahowa, T.; Coleman, M.; Hemingway, J.;Wondji, C.S. Restriction to gene flow is associated with changes in the molecular basis of pyrethroid resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2017. 114(2): p. 286-291. [CrossRef]

- Barnes, K.; Weedall, G.; Ndula, M.; Irving, H.; Mzihalowa, T.; Hemingway, J.;Wondji, C. Genomic footprints of selective sweeps from metabolic mesistance to pyrethroids in African malaria vectors are driven by scale up of insecticide-based vector control. PLoS Genet, 2017. 13(2): p. e1006539. [CrossRef]

- Weedall, G.D.; Riveron, J.M.; Hearn, J.; Irving, H.; Kamdem, C.; Fouet, C.; White, B.J.;Wondji, C.S. An Africa-wide genomic evolution of insecticide resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus involves selective sweeps, copy number variations, gene conversion and transposons. PLoS Genet, 2020. 16(6): p. e1008822-e1008822. [CrossRef]

- Galani, J.H.Y.; Houbraken, M.; Wumbei, A.; Djeugap, J.F.; Fotio, D.;Spanoghe, P. Evaluation of 99 Pesticide Residues in Major Agricultural Products from the Western Highlands Zone of Cameroon Using QuEChERS Method Extraction and LC-MS/MS and GC-ECD Analyses. Foods, 2018. 7(11): p. 184. [CrossRef]

- Bass, C.; Nikou, D.; Donnelly, M.J.; Williamson, M.S.; Ranson, H.; Ball, A.; Vontas, J.;Field, L.M. Detection of knockdown resistance (kdr) mutations in Anopheles gambiae: a comparison of two new high-throughput assays with existing methods. Malar J, 2007. 6(1): p. 111. [CrossRef]

- Trask, J.; Malhi, R.; Kanthaswamy, S.; Johnson, J.; Garnica, W.; Malladi, V.;Smith, D. The effect of SNP discovery method and sample size on estimation of population genetic data for Chinese and Indian rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Primates, 2011. 52(2): p. 129-138. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.; Lynd, A.; Vicente, J.L.; Santolamazza, F.; Randle, N.P.; Gentile, G.; Moreno, M.; Simard, F.; Charlwood, J.D.; do Rosário, V.E.; Caccone, A.; della Torre, A.;Donnelly, M.J. Multiple Origins of Knockdown Resistance Mutations in the Afrotropical Mosquito Vector Anopheles gambiae. PLoS ONE, 2007. 2(11): p. e1243. [CrossRef]

- Irving, H.;Wondji, C. Investigating knockdown resistance (kdr) mechanism against pyrethroids/DDT in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus across Africa. BMC Genet, 2017. 18: p. 76. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.; Higgins, D.;Gibson, T. CLUSTALW: improving the sensitivity of progressive miltiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res, 1994. 22(22): p. 4673-80. [CrossRef]

- Hall, T. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser, 1999. 41: p. 95-98. [CrossRef]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.;Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA Sequence Polymorphism Analysis of Large Data Sets. Mol Biol Evol, 2017. 34(12): p. 3299-3302. [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J.W.;Bryant, D. POPART: full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol Evol, 2015. 6(9): p. 1110-1116. [CrossRef]

- Saitou, N.;Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol, 1987. 4(4): p. 406-425. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.;Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol, 2018. 35(6): p. 1547-1549. [CrossRef]

- Hudson, R.R.; Slatkin, M.;Maddison, W.P. Estimation of levels of gene flow from DNA sequence data. Genetics, 1992. 132(2): p. 583-589. [CrossRef]

- Hudson, R.R.; Boos, D.D.;Kaplan, N.L. A statistical test for detecting geographic subdivision. Mol Biol Evol, 1992. 9(1): p. 138-51. [CrossRef]

- Sumo, L.; Mbah, E.N.;Nana-Djeunga, H.C. Malaria in pregnancy in the Ndop health district (North West Region, Cameroon): results from retrospective and prospective surveys. J Parasitol Vector Biol, 2015. 7(9): p. 177-181. [CrossRef]

- Elime, F.; Nkenyi, N.; Ako-Egbe, L.; Njunda, A.;Nsagha, D. Malaria in Pregnancy: Prevalence and Risk Factors in the Mamfe Health District, Cameroon. J Adv Med Med Res, 2019. 30(1): p. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Fonyuy, B.; Sirri, M.; Mercy, M.;Ndifor, D. Effectiveness of Community-Directed Intervention in the Roll-Back Malaria among the Under-Five Population of the Ndop Health District in North West Cameroon. ACLR, 2019. 7(1): p. 277. [CrossRef]

- Nyasa, R.B.; Zofou, D.; Kimbi, H.K.; Kum, K.M.; Ngu, R.C.;Titanji, V.P.K. The current status of malaria epidemiology in Bolifamba, atypical Cameroonian rainforest zone: an assessment of intervention strategies and seasonal variations. BMC Public Health, 2015. 15: p. 1105-1105. [CrossRef]

- Sumbele, I.U.N.; Teh, R.N.; Nkeudem, G.A.; Sandie, S.M.; Moyeh, M.N.; Shey, R.A.; Shintouo, C.M.; Ghogomu, S.M.; Batiha, G.E.-S.; Alkazmi, L.;Kimbi, H.K. Asymptomatic and sub-microscopic Plasmodium falciparum infection in children in the Mount Cameroon area: a cross-sectional study on altitudinal influence, haematological parameters and risk factors. Malar J, 2021. 20(1): p. 382. [CrossRef]

- Tchuinkam, T.; Nyih-Kong, B.; Fopa, F.; Simard, F.; Antonio-Nkondjio, C.; Awono-Ambene, H.-P.; Guidone, L.;Mpoame, M. Distribution of Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes and malaria-attributable fraction of fever episodes along an altitudinal transect in Western Cameroon. Malar J, 2015. 14: p. 96-96. [CrossRef]

- Wanji, S.; Tanke, T.; Atanga, S.N.; Ajonina, C.; Tendongfor, N.;Fontenille, D. Anopheles species of the mount Cameroon region: biting habits, feeding behaviour and entomological inoculation rates. Trop Med Int Health, 2003. 8(7): p. 643-649. [CrossRef]

- Wanji, S.; Mafo, F.; Tendongfor, N.; Tanga, M.; Tchuente, F.; Bilong Bilong, C.;Njiné, T. Spatial distribution, environmental and physicochemical characterization of Anopheles breeding sites in the Mount Cameroon region. J Vector Borne Dis, 2009. 46: p. 75-80.

- Tchuinkam, T.; Simard, F.; Lélé-Defo, E.; Téné-Fossog, B.; Tateng-Ngouateu, A.; Antonio-Nkondjio, C.; Mpoame, M.; Toto, J.; Njiné, T.; Fontenille, D.;Awono-Ambéné, P. Bionomics of Anopheline species and malaria transmission dynamics along an altitudinal transect in Western Cameroon. BMC Infect Dis, 2010. 10: p. 119. [CrossRef]

- Tabue, R.; Nem, T.; Atangana, J.; Bigoga, J.; Patchoké, S.; Tchouine, F.; Fodjo, B.; Leke, R.;Fondjo, E. Anopheles ziemanni a locally important malaria vector in Ndop health district, north west region of Cameroon. Parasit Vectors, 2014. 7: p. 262. [CrossRef]

- Nyasa, R.B.; Fotabe, E.L.;Ndip, R.N. Trends in malaria prevalence and risk factors associated with the disease in Nkongho-mbeng; a typical rural setting in the equatorial rainforest of the South West Region of Cameroon. PLoS ONE, 2021. 16(5): p. e0251380. [CrossRef]

- Hanemaaijer, M.J.; Higgins, H.; Eralp, I.; Yamasaki, Y.; Becker, N.; Kirstein, O.D.; Lanzaro, G.C.;Lee, Y. Introgression between Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles coluzzii in Burkina Faso and its associations with kdr resistance and Plasmodium infection. Malar J, 2019. 18(1): p. 127. [CrossRef]

- Main, B.J.; Lee, Y.; Collier, T.C.; Norris, L.C.; Brisco, K.; Fofana, A.; Cornel, A.J.;Lanzaro, G.C. Complex genome evolution in Anopheles coluzzii associated with increased insecticide usage in Mali. Mol Ecol, 2015. 24(20): p. 5145-5157. [CrossRef]

- Sy, O.; Sarr, P.C.; Assogba, B.S.; Ndiaye, M.; Dia, A.K.; Ndiaye, A.; Nourdine, M.A.; Guèye, O.K.; Konaté, L.; Gaye, O.; Faye, O.;Niang, E.A. Detection of kdr and ace-1 mutations in wild populations of Anopheles arabiensis and An. melas in a residual malaria transmission area of Senegal. Pestic Biochem Physiol, 2021. 173: p. 104783. [CrossRef]

- Bigoga, J.; Manga, L.; Titanji, V.; Coetzee, M.;Leke, R. Malaria vectors and transmission dynamics in coastal south-western Cameroon. Malar J, 2007. 6(5). [CrossRef]

- Overgaard, H.J.; Sæbø, S.; Reddy, M.R.; Reddy, V.P.; Abaga, S.; Matias, A.;Slotman, M.A.J.M.J. Light traps fail to estimate reliable malaria mosquito biting rates on Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea. Malar J, 2012. 11(1): p. 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Kristan, M.; Abeku, T.A.;Lines, J. Effect of environmental variables and kdr resistance genotype on survival probability and infection rates in Anopheles gambiae (s.s.). Parasit Vectors, 2018. 11(1): p. 560. [CrossRef]

- Mathias, D.K.; Ochomo, E.; Atieli, F.; Ombok, M.; Nabie Bayoh, M.; Olang, G.; Muhia, D.; Kamau, L.; Vulule, J.M.; Hamel, M.J.; Hawley, W.A.; Walker, E.D.;Gimnig, J.E. Spatial and temporal variation in the kdr allele L1014S in Anopheles gambiae s.s. and phenotypic variability in susceptibility to insecticides in Western Kenya. Malar J, 2011. 10(1): p. 10. [CrossRef]

- Bowen, H.L. Impact of a mass media campaign on bed net use in Cameroon. Malar J, 2013. 12: p. 36. [CrossRef]

- Chouaïbou, M.; Etang, J.; Brévault, T.; Nwane, P.; Hinzoumbé, C.K.; Mimpfoundi, R.;Simard, F. Dynamics of insecticide resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae s.l. from an area of extensive cotton cultivation in Northern Cameroon. Trop Med Int Health, 2008. 13(4): p. 476-86. [CrossRef]

- Dabiré, K.R.; Diabaté, A.; Namountougou, M.; Toé, K.H.; Ouari, A.; Kengne, P.; Bass, C.;Baldet, T. Distribution of pyrethroid and DDT resistance and the L1014F kdr mutation in Anopheles gambiae s.l. from Burkina Faso (West Africa). Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg, 2009. 103(11): p. 1113-20. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.S.; Mukhtar, M.M.; Datti, J.A.; Irving, H.; Kusimo, M.O.; Tchapga, W.; Lawal, N.; Sambo, F.I.;Wondji, C.S. Temporal escalation of Pyrethroid Resistance in the major malaria vector Anopheles coluzzii from Sahelo-Sudanian Region of northern Nigeria. Sci R, 2019. 9(1): p. 7395. [CrossRef]

- Etang, J.; Vicente, J.L.; Nwane, P.; Chouaibou, M.; Morlais, I.; Do Rosario, V.E.; Simard, F.; Awono-Ambene, P.; Toto, J.C.;Pinto, J. Polymorphism of intron-1 in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene of Anopheles gambiae s.s. populations from Cameroon with emphasis on insecticide knockdown resistance mutations. Mol Ecol, 2009. 18(14): p. 3076-3086. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.; Lynd, A.; Elissa, N.; Donnelly, M.J.; Costa, C.; Gentile, G.; Caccone, A.;Rosário, V.E.D. Co-occurrence of East and West African kdr mutations suggests high levels of resistance to pyrethroid insecticides in Anopheles gambiae from Libreville, Gabon. Med Vet Entomol, 2006. 20(1): p. 27-32. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Dixon, A.; Batbayar, N.; Bragin, E.; Ayas, Z.; Deutschova, L.; Chavko, J.; Domashevsky, S.; Dorosencu, A.; Bagyura, J.; Gombobaatar, S.; Grlica, I.D.; Levin, A.; Milobog, Y.; Ming, M.; Prommer, M.; Purev-Ochir, G.; Ragyov, D.; Tsurkanu, V.; Vetrov, V.; Zubkov, N.;Bruford, M.W. Exonic versus intronic SNPs: contrasting roles in revealing the population genetic differentiation of a widespread bird species. Heredity, 2015. 114(1): p. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Ammer, H.; Schwaiger, F.W.; Kammerbauer, C.; Gomolka, M.; Arriens, A.; Lazary, S.;Epplen, J.T. Exonic polymorphism vs intronic simple repeat hypervariability in MHC-DRB genes. Immunogenetics, 1992. 35(5): p. 332-40. [CrossRef]

- Riveron, J.; Yunta, C.; Ibrahim, S.; Djouaka, R.; Irving, H.; Menze, B.; Ismail, H.; Hemingway, J.; Ranson, H.; Albert, A.;Wondji, C. A single mutation in the GSTe2 gene allows tracking of metabolically based insecticide resistance in a major malaria vector. Genome Biol, 2014. 12: p. R27. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Yang, C.; Liu, N.; Li, M.; Tong, Y.; Zeng, X.;Qiu, X. Knockdown resistance (kdr) mutations within seventeen field populations of Aedes albopictus from Beijing China: first report of a novel V1016G mutation and evolutionary origins of kdr haplotypes. Parasit Vectors, 2019. 12(1): p. 180. [CrossRef]

- Weill, M.; Chandre, F.; Brengues, C.; Manguin, S.; Akogbeto, M.; Pasteur, N.; Guillet, P.;Raymond, M. The kdr mutation occurs in the Mopti form of Anopheles gambiae s.s. through introgression. Insect Mol Biol, 2000. 9(5): p. 451-5. [CrossRef]

- Davies, T.E.; O'Reilly, A.O.; Field, L.M.; Wallace, B.;Williamson, M.S. Knockdown resistance to DDT and pyrethroids: from target-site mutations to molecular modelling. Pest Manag Sci, 2008. 64(11): p. 1126-30. [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.M.; Liyanapathirana, M.; Agossa, F.R.; Weetman, D.; Ranson, H.; Donnelly, M.J.;Wilding, C.S. Footprints of positive selection associated with a mutation (N1575Y) in the voltage-gated sodium channel of Anopheles gambiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2012. 109(17): p. 6614-9. [CrossRef]

- Riveron, J.M.; Watsenga, F.; Irving, H.; Irish, S.R.;Wondji, C.S. High Plasmodium Infection Rate and Reduced Bed Net Efficacy in Multiple Insecticide-Resistant Malaria Vectors in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. J Infect Dis, 2018. 217(2): p. 320-328. [CrossRef]

- Kawada, H.; Futami, K.; Komagata, O.; Kasai, S.; Tomita, T.; Sonye, G.; Mwatele, C.; Njenga, S.M.; Mwandawiro, C.; Minakawa, N.;Takagi, M. Distribution of a Knockdown Resistance Mutation (L1014S) in Anopheles gambiae s.s. and Anopheles arabiensis in Western and Southern Kenya. PLoS ONE, 2011. 6(9): p. e24323. [CrossRef]

- Faries, K.M.; Kristensen, T.V.; Beringer, J.; Clark, J.D.; White, D., Jr.;Eggert, L.S. Origins and genetic structure of black bears in the Interior Highlands of North America. J Mammal, 2013. 94(2): p. 369-377. [CrossRef]

- Packer, C.; Pusey, A.E.; Rowley, H.; Gilbert, D.A.; Martenson, J.;O'Brien, S.J. Case Study of a Population Bottleneck: Lions of the Ngorongoro Crater. Conserv Biol, 1991. 5(2): p. 219-230.

- Coetzee, M.; Hunt, R.; Wilkerson, R.; Della Torre, A.; Coulibaly, M.;Besansky, N. Anopheles coluzzii and Anopheles amharicus, new members of the Anopheles gambiae complex. Zootaxa, 2013. 3619: p. 246-274.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).