1. Introduction

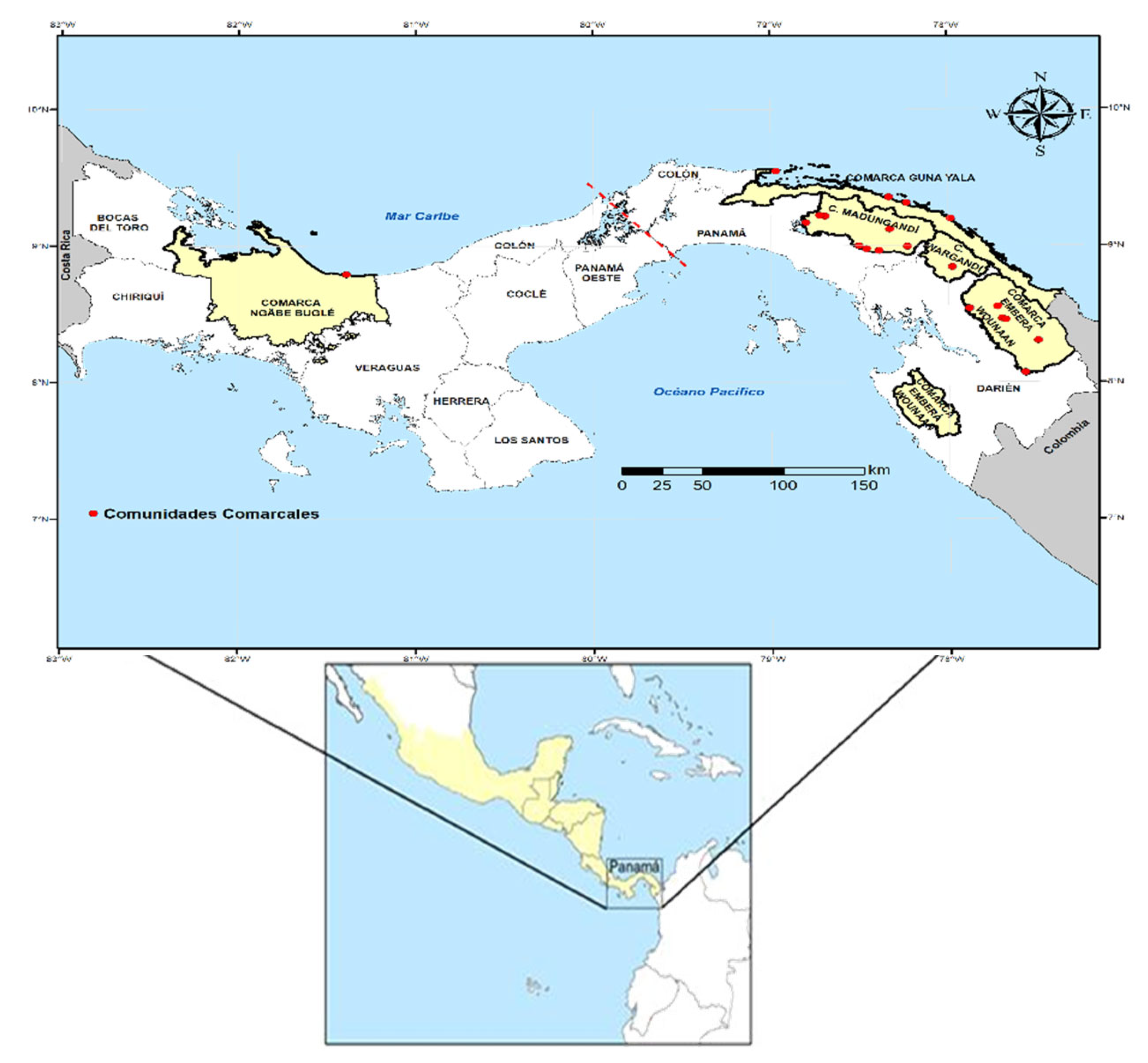

Due to its relatively low number of cases and deaths compared to other regions, the World Health Organization (WHO) has identified Mesoamerica as having the potential for malaria elimination in the short term [1, 2]. Indeed, several countries from this subregion of the Americas, encompassing southeastern Mexico and Central America, have made significant progress in malaria elimination efforts. However, heterogeneity in disease epidemiology, both between and within countries, has resulted in uneven progress towards elimination. While some countries from this subregion, such as El Salvador end Belice, have recently been certified malaria-free by the WHO [

1], others like Panama, located at the southernmost point of Mesoamerica, still faces significant transmission challenges.

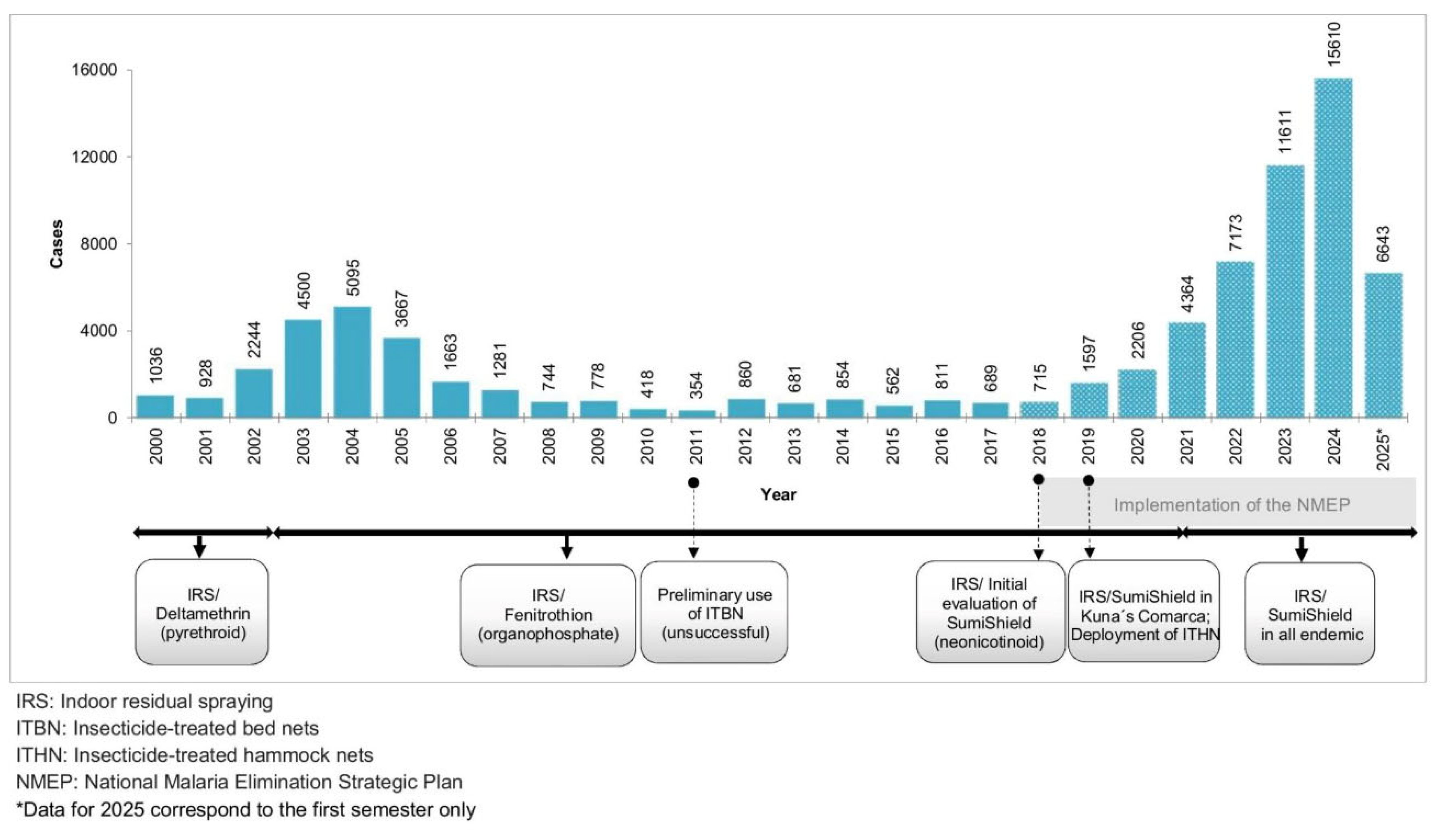

Although Panama is part of the E-2025 initiative aiming to eliminate local malaria transmission by 2025, the number of indigenous cases has increased dramatically from 375 in 2015 to 15610 in 2024 (

Figure 1). This represents an alarming rise of over 4,000% during this period, highlighting major obstacles in achieving national elimination goals. In fact, in recent years, malaria has been considered one of the most important re-emerging vector-borne diseases in the country.

Several factors may have contributed to this uncontrol increase in cases, including but not limited to health threats posed by climate change and the mass human migration crossing the Darien Gap in Panama aiming to reach the United States or Canada [

3]. In fact, malaria transmission has risen along migration routes in eastern Panama [

1]. This situation is further exacerbated by growing concerns over the reduced effectiveness of interventions, driven by biological threats such as emerging drug and insecticide resistance in local parasite and anopheline vector populations [

4].

Considering this epidemiological scenario, completely off-track from elimination targets, the National Malaria Elimination Program (NMEP) in Panama is now reorienting its intervention strategies to regain malaria control, particularly prioritizing high transmission areas. In this context, effective vector control interventions remain a critical strategy for preventing malaria epidemics resulting from local transmission and secondary infections triggered by imported cases [

4,

5].

Although several species have been documented in Panama [

6],

Anopheles albimanus is by far the most abundant and widespread malaria vector across endemic regions in the country [

6,

7]. Indoor residual spraying (IRS) involving the rotation of different insecticides, has been the main vector control intervention in Panama. However, in recent years the NMEP has also implemented the use of insecticide-treated nets (ITN) for beds and hammocks in selected communities with high transmission [

8,

9] (

Figure 1).

Since the beginning of the national malaria control program in Panama (1957), multiple classes of insecticides (organochlorines, organophosphates, carbamates, pyrethroids, and more recently neonicotinoids) have been intensively and repeatedly used, exerting considerably selective pressure on Anopheles populations. However, the selection of insecticides for IRS has often been based on product availability or international recommendations with no previous evaluation, rather than on localized entomological and resistance surveillance evidence. As a result, current knowledge about the status and distribution of insecticide resistance in An. Albimanus population from Panama remains limited.

Given that insecticide resistance poses a significant threat to the efficacy of current malaria vector-control interventions, this study evaluated the molecular resistance profile of An. albimanus populations by detecting the presence, frequency and distribution of resistance alleles in three key genes encoding targets of commonly used insecticides: ace-1 (encoding acetylcholinesterase), vgsc (encoding the voltage-gated sodium channel), and rdl (encoding the GABA receptor). The Plasmodium infection status of collected mosquitoes was evaluated throughout the study period. In addition, we conducted a preliminary analysis of the genetic diversity among An. albimanus populations from various endemic regions to explore potential geographic structuring and population differentiation.

3. Results

Molecular screening was performed in 891 adult female An. albimanus specimens (collected between 2011 and 2023) distributed in 162 pools: 120 pools from Madungandí comarca, 7 from Guna Yala, 2 from Wargandí, 22 from Emberá Wounaan and 11 from Ngäbe Buglé. Pools were molecularly examined to detect natural infection with Plasmodium and were sequenced to assess mutations in genes (vgsc, ace-1 and rdl) associated with resistance to commonly used insecticides for malaria vector control.

3.1. Plasmodium Infection in Collected An. Albimanus

The overall prevalence of

Plasmodium infection in female

Anopheles mosquitoes was found to be 61.7% (100/162 pools), with a much higher

Plasmodium frequency in the Comarca Madungandí (

Table S2). The overall estimated prevalence calculated by the method of pooled prevalence was 0.17%. Of the 100 positive pools, 84 were found positive for

P. vivax (85.81%), 9 pools for

P. falciparum and 7 were mix-infections by both species (5.1%).

Plasmodium falciparum infections were detected in pools from

Anopheles collected in the Madungandí comarca between 2020 and 2023 (

Table S2).

3.2. Frequency and Distribution of Vgsc Genotypes

Of the 162 An. albimanus pools, 122 sequences corresponding to segment 6 of domain II of the vgsc gene were successfully genotyped. All sequences were aligned and compared with reference vgsc gene sequences from An. albimanus available in GenBank under accession numbers OL630652.1, KF137581.1, and MN087506.1. The wild-type allele (susceptible to pyrethroid) at codon 1014 (TTG; leucine, L1014) was present in 64 sequences (52.5%), while the wild-type allele at codon 973 (CAT; histidine, H973) was found in 28 sequences (22.9%).

Conversely, pyrethroid resistance-associated mutations resulting in amino acid substitutions, were identified at both codons (1014 and 973). At codon 1014, the well-characterized knockdown resistance (

kdr) mutation was detected in almost half of the sequences, including TTC (phenylalanine, L1014F) in 6 sequences (4.9%) and TGT (cysteine, L1014C) in 40 sequences (32.8%). Additionally, heterozygous alleles were identified at this codon: TKY in 9 sequences (7.3%) and TKK in 3 sequences (2.5%); all originating from pools collected in the eastern comarcas of Madungandí and Emberá-Wounaan (Fig. 3 and Fig. S1). The

kdr mutation was found to fixed in

An. albimanus pools analyzed from eastern regions since 2021 (

Table S3).

At codon 973, the mutation TAT (tyrosine, H973Y), also implicated in resistance to pyrethroids, was observed in 64 sequences (52.5%); all of which were homozygotes and originated from eastern comarcas. Overall, 50.8% of the

kdr-associated mutant alleles (L1014F/C and H973Y) were detected in pools from communities within the Madungandí Comarca (n = 62), located east of the Panama Canal (Fig. 3 and Fig. S1). In contrast, none of the

vgsc sequences analyzed in this study from the Ngäbe-Buglé comarca located west of the Panama Canal, exhibited mutation associated with pyrethroids resistance (

Table S3).

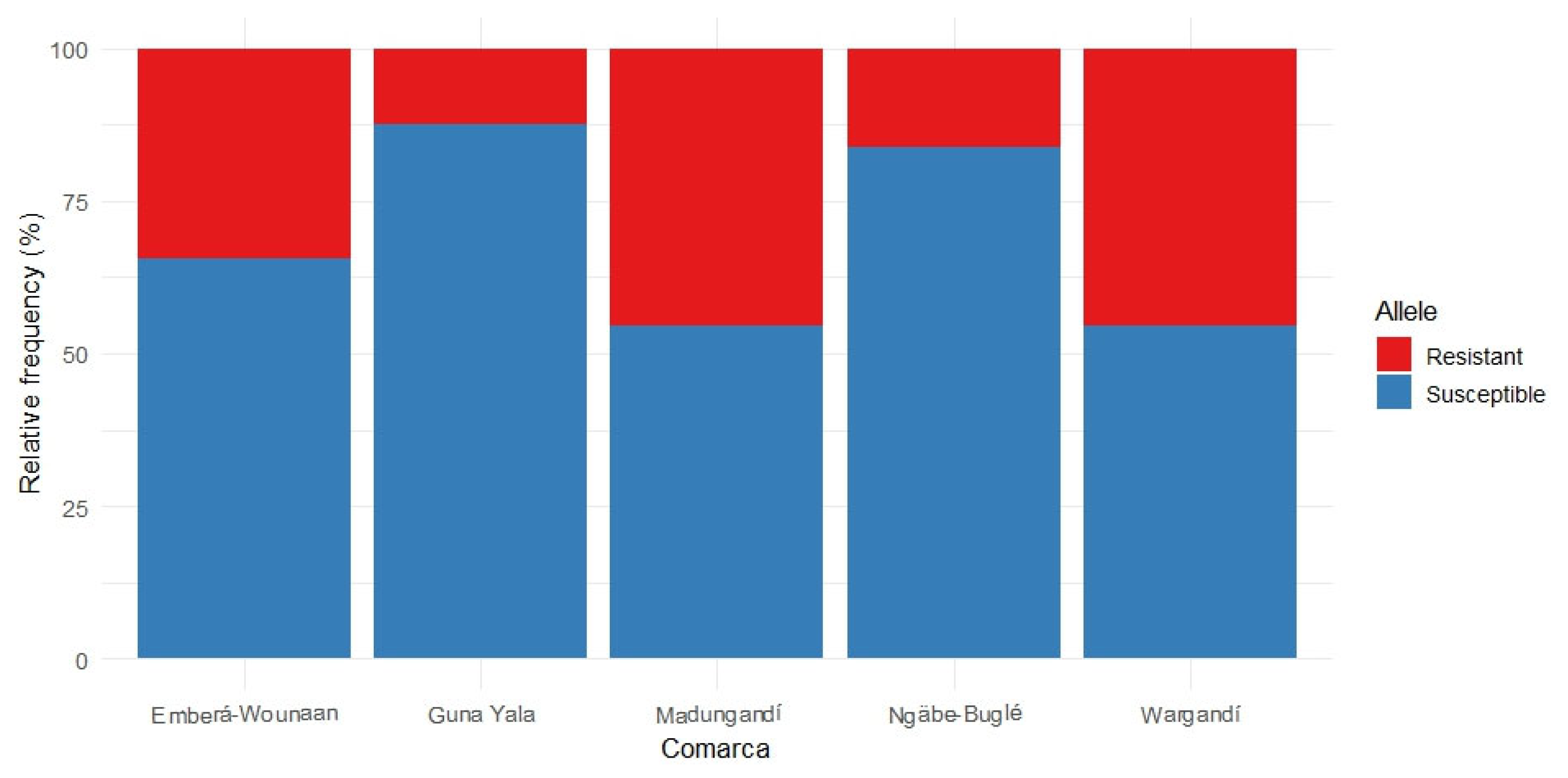

Figure 3.

The frequency for each allele within the vgsc, ace-1, and rdl genes is shown. Alleles associated with insecticide resistance are displayed in red, while susceptible alleles are shown in blue. These alleles were detected in pooled samples of Anopheles albimanus from comarcas in Panama.

Figure 3.

The frequency for each allele within the vgsc, ace-1, and rdl genes is shown. Alleles associated with insecticide resistance are displayed in red, while susceptible alleles are shown in blue. These alleles were detected in pooled samples of Anopheles albimanus from comarcas in Panama.

3.3. Frequency and Distribution of Ace-1 Genotypes

All

ace-1 sequences from this study were aligned with reference acetylcholinesterase-1 gene sequences from

An. albimanus (GenBank accessions AJ566403.1 and AJ566402.1) and

An. darlingi (MK477204.1). All three possible genotypes of the

ace-1 gene were identified at codon 119 in 132 sequences analyzed. These included the homozygous susceptible genotype (119GG) found in 36 sequences (27%), the heterozygous genotype (119GS) in 77 sequences (58%) and the homozygous resistant genotype (119SS) found in 18 samples (14.7%), which is associated with resistance to organophosphorus (OP) and carbamate (CM) insecticides. The resistance-associated mutation (G119S) was detected in samples from communities in eastern Panama, including Madungandí (n = 15), Emberá-Wounaan (n = 2), and Wargandí (n = 1) (Fig. 3, Fig. S1 and

Table S3). Notably, the G119S mutation was absent in samples collected from western Panama.

3.4. Frequency and Distribution of Rdl Genotypes

Three non-synonymous mutations were identified in the

rdl gene based on the analysis of 91

An. albimanus sequences from this study. All sequences were aligned with the reference

rdl gene sequence from

An. funestus, available in GenBank under accession number MN562790.1. Nucleotide variations resulting in corresponding amino acid changes were observed at codons 299, 302, and 333 (

Table S3). All identified alleles in the

rdl gene from this study were found in homozygous form.

At codon 299, the wild-type allele GCA, which encodes alanine (A299), was found in 86 sequences (94.5%). A mutant variant encoding proline (A299P; CCA) was detected in five sequences (5.5%), including four from eastern comarcas and one from the Ngäbe-Buglé Comarca (n = 1) in western Panama (Fig. 3, Fig. S1 and

Table S3).

At codon 302, the well-characterized resistance-associated mutation (A302S) that results in the substitution of the amino acid alanine (GSA) with serine (TCA), was detected in 67 sequences (73.6%) (Fig. 3). This A302S substitution was found predominantly in samples from eastern Panama, including Madungandí (n = 56), Emberá-Wounaan (n = 11) and Wargandí (n = 3), as well as in one sample from the western comarca of Ngäbe-Buglé (n = 1) (Fig S1).

An additional polymorphism was detected at codon 333. The wild-type allele GTA, which encodes valine (V333), was identified in 45 sequences (49.5%), while a variant allele ATA (V333I) encoding isoleucine was found in 36 sequences (39.5%). This V333I variant was observed in

An. albimanus pools from communities in Madungandí (n = 29) and Emberá-Wounaan (n = 6) in eastern Panama, and in one sample from the Ngäbe-Buglé Comarca in western Panama (Fig. 3, Fig. S1 and

Table S3).

The total number of alleles (resistant and susceptible) detected in the

An. albimanus pools from each of the five comarcas studied is summarized in

Figure 4. Although there was considerable variability in the number of samples analyzed from each comarca, Madungandí exhibited the highest number of detected alleles, followed by Wargandí and Emberá-Wounaan. In contrast, the eastern comarcas of Guna Yala and Ngäbe-Buglé in the west, displayed lower frequencies. The ratio of resistant to susceptible alleles also varies among comarcas, suggesting regional differences in genetic resistance patterns.

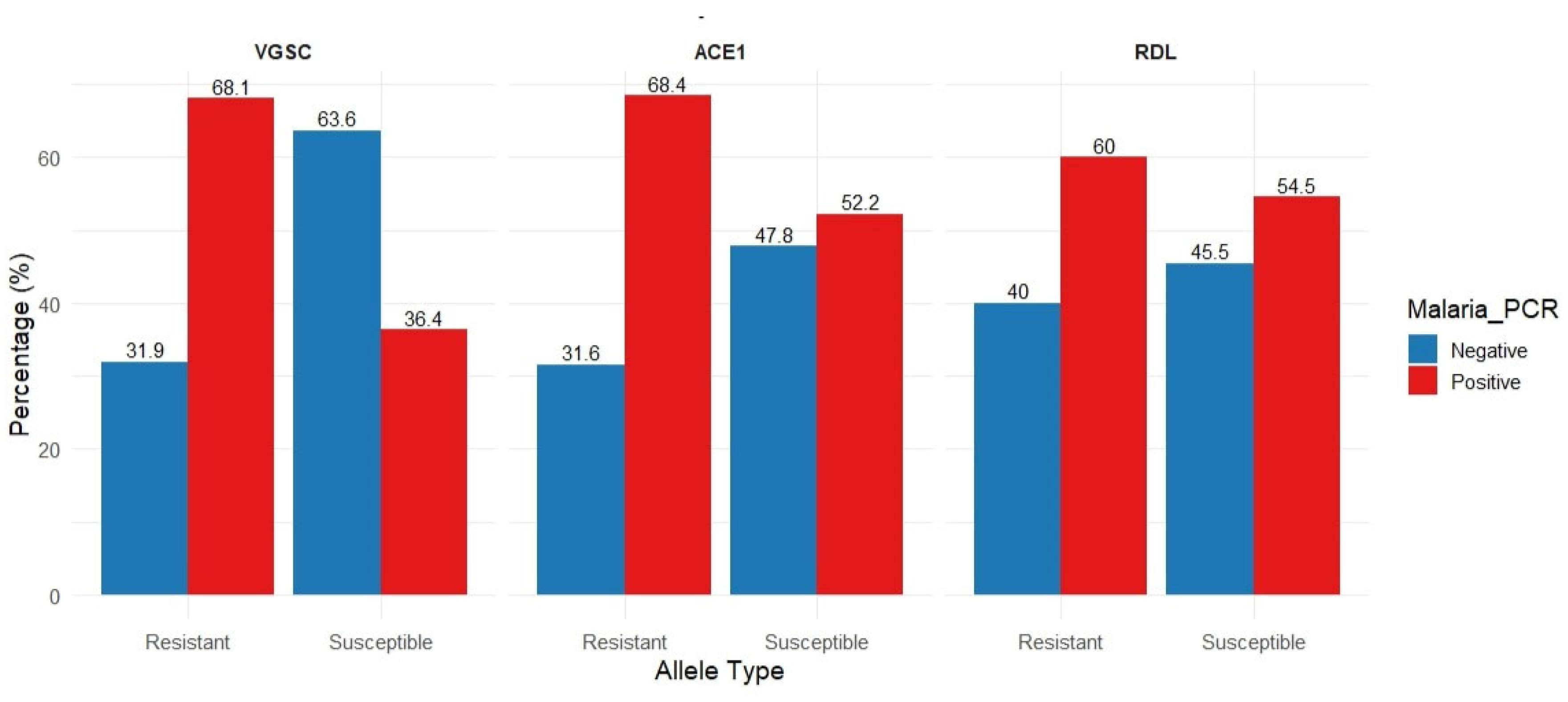

3.5. Plasmodium Infection and Presence of Resistance Alleles

The potential association between Plasmodium infection and the presence of resistance/susceptible alleles in vgsc, ace-1 and rdl genes was assessed in the collected An. Albimanus pools. For all three genes, the frequency of resistant alleles was higher in Plasmodium positive samples (Fig. 5). This difference was statistically significant for vgsc (p= 0.048) and for ace -1 (p= 0.047), but not for rdl gene (p = 0.75) (

Table S4).

Figure 5.

The possible assocition between Plasmodium infection and the existence of resistant or susceptible alleles in the vgsc, ace-1, and rdl genes was evaluated in pooled samples of Anopheles albimanus. The bars show the Plasmodium infection rate (%) based on the existence of resistant (red) or susceptible (blue) alleles for each gene examined. The rate of resistant alleles was higher in Plasmodium-positive groups in all three genes. A statistical significance of these differences was observed for vgsc (p = 0.048) and ace-1 (p = 0.047), while it was not significant for the rdl gene (p = 0.75).

Figure 5.

The possible assocition between Plasmodium infection and the existence of resistant or susceptible alleles in the vgsc, ace-1, and rdl genes was evaluated in pooled samples of Anopheles albimanus. The bars show the Plasmodium infection rate (%) based on the existence of resistant (red) or susceptible (blue) alleles for each gene examined. The rate of resistant alleles was higher in Plasmodium-positive groups in all three genes. A statistical significance of these differences was observed for vgsc (p = 0.048) and ace-1 (p = 0.047), while it was not significant for the rdl gene (p = 0.75).

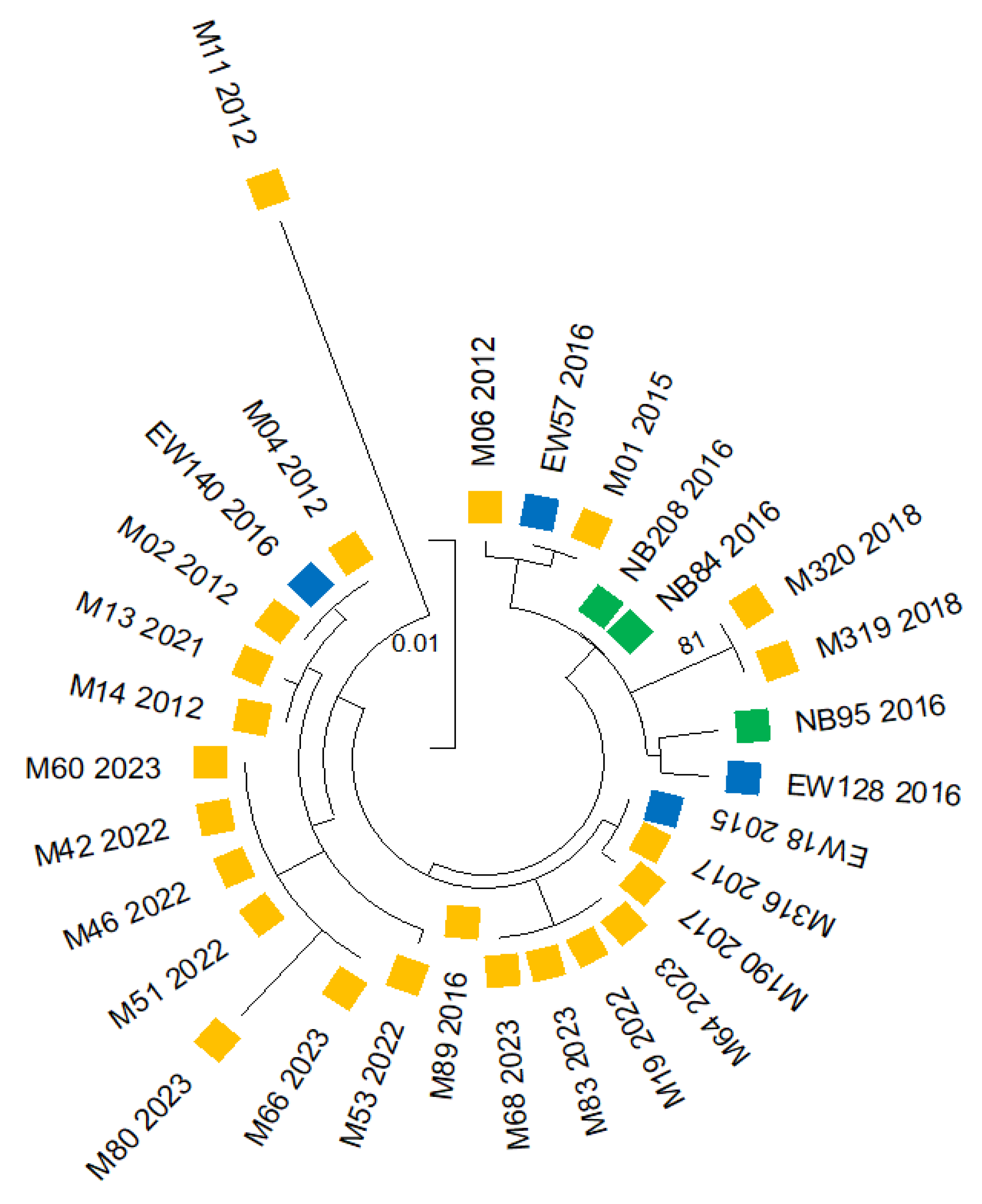

3.6. Phylogenetic and Genetic Diversity Analyses

Phylogenetic tree reconstruction and a haplotype network analysis were conducted using concatenated sequences of the three insecticide resistance markers (vgsc, ace-1 and rdl genes) from An. albimanus collected between 2011 and 2023 across three comarcas (Madungandí and Emberá-Wounaan from the east, and Ngäbe-Buglé from the west). The phylogenetic tree was inferred using the Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura model. The final analysis incorporated 30 nucleotide sequences, covering 629 positions in the final dataset (Fig. 6 and

Table S1). The complete sequence alignment of the concatenated genes from this study is available upon request.

With the exception of a single sample (M11 2012), all samples grouped in a predominant, well-defined clade that encompassed samples from the three comarcas and from the multiple collection years, indicating the absence of a dominant genotype circulating, and instead suggests the persistence of diverse genotypes coexisting over time (Fig 6). Within this predominant clade, several subclades were observed, reflecting a greater genetic diversity among samples generated from eastern comarcas mainly from Madungandí, which clustered into distinct subclades with closer genetic relatedness between them. In contrast, sequences from the Ngäbe-Buglé comarca located in western Panama formed a separate subclade together with some eastern samples from Madungandí and Emberá-Wounaan, indicating some degree of genetic connectivity.

The distinct sample M11 2012 was collected from Puente Bayano, a hiperendemic community located in the eastern comarca of Madugandí. This sample grouped apart in a different clade, highlighting its genetic distance from the rest of the samples analyzed.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic tree constructed from concatenated sequences of three insecticide resistance markers (vgsc, ace-1 and rdl genes) from 30 An. Albimanus collected between 2011 al 2023 in three comarcas: 23 from Madungandí (yellow color), 4 from Emberá-Wounaan (turquoise color) and 3 from Ngäbe-Buglé (green color). The phylogenetic tree was inferred using the Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura model. The final analysis incorporated 30 nucleotide sequences, covering 629 positions in the final dataset.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic tree constructed from concatenated sequences of three insecticide resistance markers (vgsc, ace-1 and rdl genes) from 30 An. Albimanus collected between 2011 al 2023 in three comarcas: 23 from Madungandí (yellow color), 4 from Emberá-Wounaan (turquoise color) and 3 from Ngäbe-Buglé (green color). The phylogenetic tree was inferred using the Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura model. The final analysis incorporated 30 nucleotide sequences, covering 629 positions in the final dataset.

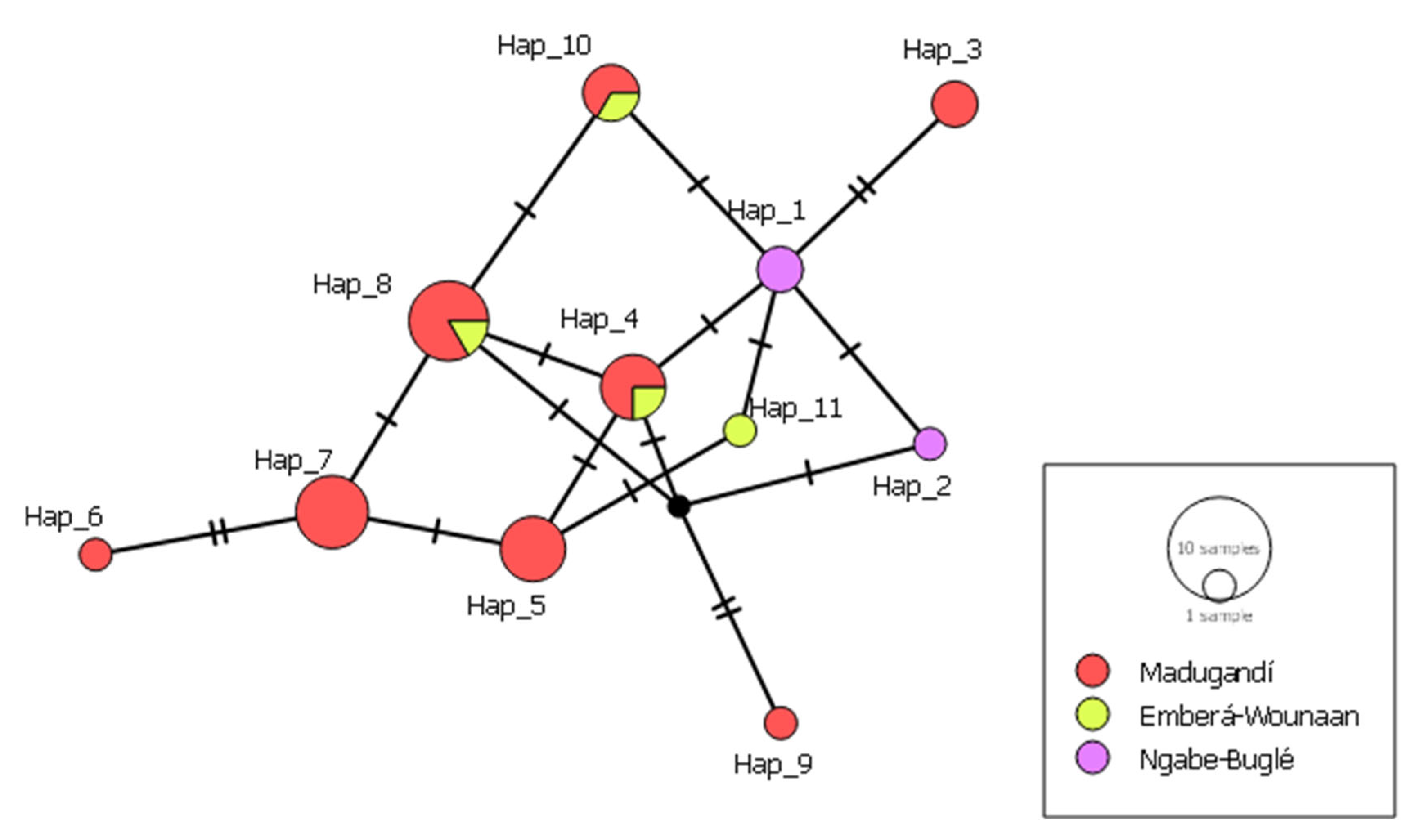

The haplotype network analysis, based on the concatenated gene sequences revealed the presence of 11 distinct haplotypes (

Figure 7). Most haplotypes were restricted to a single comarca, indicating localized circulations of specific genetic variants. For example, haplotypes 3, 5, 6, 7 y 9 were only found in Madugandí, while haplotype 11 was restricted to the comarca Emberá-Wounaan, both located in eastern Panama. In contrast, haplotypes 1 y 2 were exclusively identified in the comarca Ngäbe-bugle in western Panama. Haplotypes 4, 8 and 10 contained samples from different eastern comarcas and showed genetic relatedness between them, indicating potential gene flow or shared ancestry among populations in that region.

To explore potential geographic structuring and population differentiation among An. albimanus populations collected in this study, a preliminary analysis of the genetic diversity was performed. For this purpose, samples were grouped according to the collection site into two ecologically and geographically distinct malaria-endemic regions of Panama (Eastern and Western). Genetic diversity indexes were calculated and compared for each of the three resistance-associated genes (vgsc, ace-1 and rdl) (

Table S5). Higher diversity indexes were captured with the vgsc gene (kdr) and therefore was chosen for further diversity analysis.

Substantial differences in genetic diversity were observed among both groups. Eastern populations exhibited a high genetic diversity, with 7 segregating sites, 14 haplotypes, and a haplotype diversity of 0.77. The nucleotide diversity (ᴫ = 0.078) and the presence of 8 different mutations, reflect the heterogeneous origins of these specimens. The negative Fu's Fs statistic (-5.89) is consistent with recent population expansion or that Anopheles populations from this region are under selective pressure.

In contrast, western Panama populations displayed low genetic diversity, with only two haplotypes identified. Most specimens were genetically similar l (Hd = 0.48; ᴫ = 0). This homogeneity suggests a clonal population structure or genetic bottleneck, possibly due to limited gene flow, localized vector control pressure or ecological constraints.

4. Discussion

After falling short of meeting the 2025 malaria elimination goals set by the WHO Global Technical Strategy (GTS), the NMEP in Panama is currently adjusting strategies to address issues that might have hindered elimination progress. A key component of this revised strategy needs to include a more effective and evidenced-based vector control program, guided by local epidemiological and entomological data, including a program for monitoring and managing insecticide resistance [

24]. In this context, this study provides the first molecular evidence in the country on how allelic variants might be contributing to the resistance status to insecticides in

An. albimanus populations, the dominant malaria vector in Panama across malaria endemic comarcas.

Over the past several decades, malaria transmission in Panama has remained disproportionally clustered in indigenous comarcas that together occupy approximately 22.0% of the Panamanian territory [

25]. Indeed, malaria cases in these reservations have accumulated more than 90% of all cases diagnosed in the country in the last decades [

12]. Indigenous communities living in comarcas are highly underserved, with substantially higher rates of extreme poverty and limited healthcare compared to the rest of the country [12, 25]. These areas are not generally exposed to the high amounts of agrochemicals used in large-scale crop plantations, since their indigenous inhabitants relied mainly on subsistence agriculture and fishing. However, these areas have been subjected to recurrent applications of multiple classes of insecticides used primarily as IRS by vector control programs. This continued exposure might have exerted strong selection pressure over vector populations, therefore favoring the emergence of resistance alleles.

At the initial phases of NMP in Panama (from the early 1960´s to the 1980´s), organochlorides (DDT and dieldrin) and carbamates (Propoxur) were widely used as part of the IRS vector control program [

12]. Over the past 25 years, these insecticides have been replaced by chemicals from the pyrethroid, organophosphate, and neonicotinoid classes. Pyrethroids (Deltamethrin) were used between 1996 and 2002, followed by the organophosphate fenitrothion (Sumithion) from 2002 to 2020 (

Figure 1). In September 2019, a neonicotinoid insecticide (Sumishield) was introduced as an alternative to fenitrothion in three eastern highly endemic comarcas: Madungandí, Guna Yala and Wargandí. Its use was later expanded to the remaining malaria-endemic regions beginning in 2021, (

Figure 1) [

9]. However, in most cases, changes in insecticides for IRS have been driven primarily by product availability or international policy recommendations rather than by thorough local evaluations of insecticide effectiveness and resistance status of the local vectors.

To evaluate the molecular resistance status of

An. albimanus in Panama, we analyzed mutations in three genes (

vgsc,

ace-1, and

rdl) shown to be strongly associated with resistance to common insecticides. v

gsc gene is the primarily target of pyrethroids and DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane), and mutations at codons 973 and 1014 have been shown to confer resistance to both insecticides in

Anopheles mosquitoes [26, 27,28]. In this study, both mutations (H973Y and L1014F/C) were detected at high frequencies (50.8%) in eastern comarcas but were absent in comarcas located west of the Panama Canal (

Figure 3 and

Table S3).

Acetylcholinesterase is the primary molecular target of organophosphates and carbamates, and genetic variants in this gene have been clearly recognized to confer resistance to both insecticides in

Anopheles populations [28, 29]. The resistance-associated mutation (G119S) was widespread in eastern comarcas (over 70% of the samples evaluated) but was not detected in western comarcas (

Figure 3 and

Table S3).

Three non-synonymous mutations (A299P, A302S, V333I) were identified in the

rdl gene, the primary target for insecticides of several insecticides, including cyclodienes (dieldrin) (

Figure 3 and

Table S3). This gene has also been identified as a potential secondary target for other insecticide classes, including neonicotinoids and pyrethroids [

30]. The resistance-related amino acid substitution A302S was detected at high frequencies (73.6%) across all studied comarcas, particularly in the east. A valine to isoleucine amino acid substitution was detected at codon 333 (V333I) in 39.5% of the samples. A similar amino acid replacement has been described at codon 327 in

Anopheles species from Africa and Asia [

31,

32]. Further studies are needed to assess the impact of the V302I mutation in

An. albimanus populations. An additional non-synonymous substitution was detected at low frequencies (5.5%) at codon 299 (alanine to proline) on the

rdl gene (A299P). The biological implication of this amino acid substitution in

An. albimanus populations warrants further investigation.

Dieldrin or other cyclodienes have not been used in the country by the NMP since the early 1960´s. Therefore, the existence of rdl mutant alleles in An. albimanus populations could be associated with the use of other insecticides by NMP that also target rdl, such as neonicotinoids. It is also possible that these mutant alleles are stable in the absence of insecticide pressure or that they confer a selective advantage compared to the wild types.

Few studies have evaluated the presence and frequency of insecticide resistance-associated mutations in dominant

Anopheles populations from Mesoamerica (from Panama to southern Mexico). Resistant

kdr alleles have been previously reported in

An. albimanus populations from México, Nicaragua and Costa Rica [33, 34]. Conversely, a recent study did not detect

kdr or

ace-1 mutations in

An. albimanus from the State of Quintana Roo in southeastern Mexico [

35]. The present study represents the first report of

kdr and

ace-1 mutations in

An. albimanus populations from Panama and is the first description of

rdl polymorphisms in

Anopheles from Mesoamerica.

A high molecular infection rate by

P. vivax was observed in the

An. albimanus pools collected from all comarcas (

Table S2), a finding consistent with the high

P. vivax transmission reported in humans during the collection years. Notably,

P. falciparum infections were detected in pools collected in recent years (2022-2023) from communities within the eastern comarca of Madungandí (

Table S3). This finding preceded the official confirmation of human

P. falciparum cases in 2024 from the same communities where infected vectors were found. Autochthonous

P. falciparum transmission was virtually eliminated in the country, but it has now re-emerged in the eastern comarcas of the country. In this context, monitoring infection in mosquito vectors for

Plasmodium species can be helpful as an important early warning tool to anticipate changes in human malaria transmission, including the possible resurgence of

Plasmodium species in a specific area.

Several studies have suggested that the presence of mutations associated with insecticide resistance in

Anopheles can affect their vector competence, influencing the outcome of malaria infection by increasing

Plasmodium susceptibility and infection rates [36, 37, 38, 39]. In this study, we also found a positive association between the presence of resistance alleles in

vgsc/

ace -1 genes, and an increased infection rates by

Plasmodium in

An. albimanus populations (

Table S4). More studies are needed for a comprehensive understanding of the epidemiological consequences of this relationship, and its importance when designing vector control strategies in different endemic settings.

Although insecticide-resistance genes may not be ideal for conducting genetic diversity studies in

Anopheles due to the strong selective pressures to which they are frequently subjected, our results evidence a distinct

An. albimanus population structure between eastern and western comarcas (

Table S4). Mosquitoes from the western side were highly homogenous, suggesting a clonal expansion, possibly due to limited gene flow or ecological isolation. In contrast, eastern samples exhibited a much higher genetic diversity, possibly influenced by geographical, ecological and epidemiological differences that characterize this region that includes a higher vector species abundance / diversity and intense malaria transmission rate compared to the western side.

Our study has several important limitations. First, the number of pools analyzed was relatively small and with a limited timeframe, spanning from 2011 to 2023. There was also an uneven distribution of the number of pools collected across the comarcas, with a considerable underrepresentation of samples from the western comarca of Ngäbe Buglé. Consequently, our results may not necessarily capture the entire or current insecticide-resistance profile or the diversity of An. albimanus populations in the country. However, it is noteworthy mentioning that collecting mosquitoes in malaria endemic regions in Panama is logistically challenging. Most of these areas are remote and difficult to reach, particularly western comarcas during the rainy season. Transporting mosquito samples from remote areas to specialized laboratories for molecular testing is also time-consuming and costly.

Analyzing Anopheles mosquitoes in pools instead of individually is also major limitation that not only can negatively impact on an accurate estimation of allele frequencies but also can affect the estimation of population genetic parameters, such as determining allele zygosity of the mutations associated with insecticide resistance. Nevertheless, pool analysis can be an efficient and cost-effective approach when working in most malaria endemic settings, characterized by resource constraints. It is also an efficient strategy when the goal is rapid screening of common mutations or a preliminary assessment to identify population structure.

Despite the limited and unbalanced sample size across the comarcas, our study provides a valuable baseline for planning future molecular vector surveillance studies in the region. It also provides valuable information to guide insecticide selection for IRS performed by the NMEP in Panamá. Nevertheless, our molecular results for assessing insecticide resistance in Anopheles should be confirmed with additional susceptibility phenotypic bioassays, such as the WHO tube test and CDC bottle assay.

In conclusion, resistance related mutations to all four main classes of insecticides were present at high frequencies in An. albimanus populations from eastern Panama, while they were absent or at low frequencies in populations from the western region These findings emphasize the need to implement region-specific vector control strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A.R., G.G., A.C., J.E.C.; methodology, C.A.R., V.V., A.M.S., J.E.C., G.G., A.C.; software, C.A.R., V.V., L.A.H., G.G.; validation, C.A.R., J.E.C., G.G., A.C. and V.V.; formal analysis, C.A.R., J.E.C., G.G., V.V.; investigation, C.A.R., V.V., A.M.S., L.C.,; resources, C.A.R., A.M.S., L.A.H., L.C.; data curation, C.A.R., J.E.C., G.G., A.C., V.V.; writing—original draft preparation, C.A.R., J.E.C.,V.V.; writing—review and editing, C.A.R., J.E.C., G.G., A.C., V.V.; visualization, C.A.R., J.E.C., G.G., A.C., V.V.; supervision, J.E.C., G.G., A.C.; project administration, C.A.R., J.E.C.; funding acquisition, C.A.R., J.E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.