1. Introduction

Malaria remains one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa, especially among children under five years and pregnant women [

1]. Despite recent advances in malaria vaccine development, insecticide-based interventions, including long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS), remain the most effective prevention methods [

2]. However, the success of these interventions depends on a good understanding of vector population dynamics, particularly their susceptibility to insecticides, to guide the deployment of these tools. In mosquitoes, two major mechanisms of insecticide resistance are target-site and metabolic resistance [

3,

4,

5]. Target site resistance involves genetic changes that alter the protein targeted by the insecticide, while metabolic resistance results from changes in the sequence or expression of a complex array of enzymes and detoxification pathways that remove the insecticide from the system [

6]. In addition to these mechanisms, behavioral and cuticular resistance, have also been described in malaria vectors [

7]. The rise of resistance remains a major concern for malaria control and calls for continued resistance surveillance and rapid development of alternative control tools to accelerate malaria elimination.

Although target-site resistance has been extensively described in the African malaria vector

An. gambiae s.l., metabolic resistance remains poorly characterized [

8], likely due to the number of gene families involved in detoxification, redundancy among their members, and the multiple mechanisms by which metabolic resistance can arise [

9]. However, investigations on this mechanism are becoming increasingly crucial, especially as recent studies demonstrated the growing contribution of the detoxification genes to the resistance phenotype observed in

Anopheles gambiae s.l. [

10,

11,

12]. This trend is likely driven by new mutations within genes encoding detoxifying enzymes that are associated with resistance phenotypes in members of the

An. gambiae complex [

13]. Enzymes that detoxify insecticides include cytochrome P450s, glutathione-S-transferases and carboxylesterases [

14].

One of the major challenges in the ongoing fight against malaria is the identification of genomic bases of resistance, particularly in ways that can inform vector control programs in the field [

15]. Traditionally, insecticide resistance has been monitored using phenotypic assays such as WHO tube tests or CDC bottle bioassays. While useful, these methods are labor-intensive, time-consuming, and require substantial logistical resources. In contrast, advances in genomics now offer powerful alternatives, enabling the identification and surveillance of molecular markers associated with resistance in natural mosquito populations [

16]. To date, most genomic studies have focused on specific regions of the genome already known to be linked with resistance. However, given the dynamic and rapidly evolving nature of insecticide resistance, including the frequent emergence of novel resistance mechanisms, whole genome analysis represents an optimal investigative approach. Genome-wide scans for signatures of adaptive evolution, such as selective sweeps, provide a comprehensive framework to detect emerging resistance loci beyond known targets.

In this study, we used genome-wide scans for selection (GWSS) to detect genomic regions under signals of selection in Anopheles gambiae s.l. populations across sub-Saharan Africa. A literature review and genetic variability analyses were conducted to identify, within these regions and populations, aldehyde oxidase gene family, a novel candidate associated with insecticide resistance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Analysis

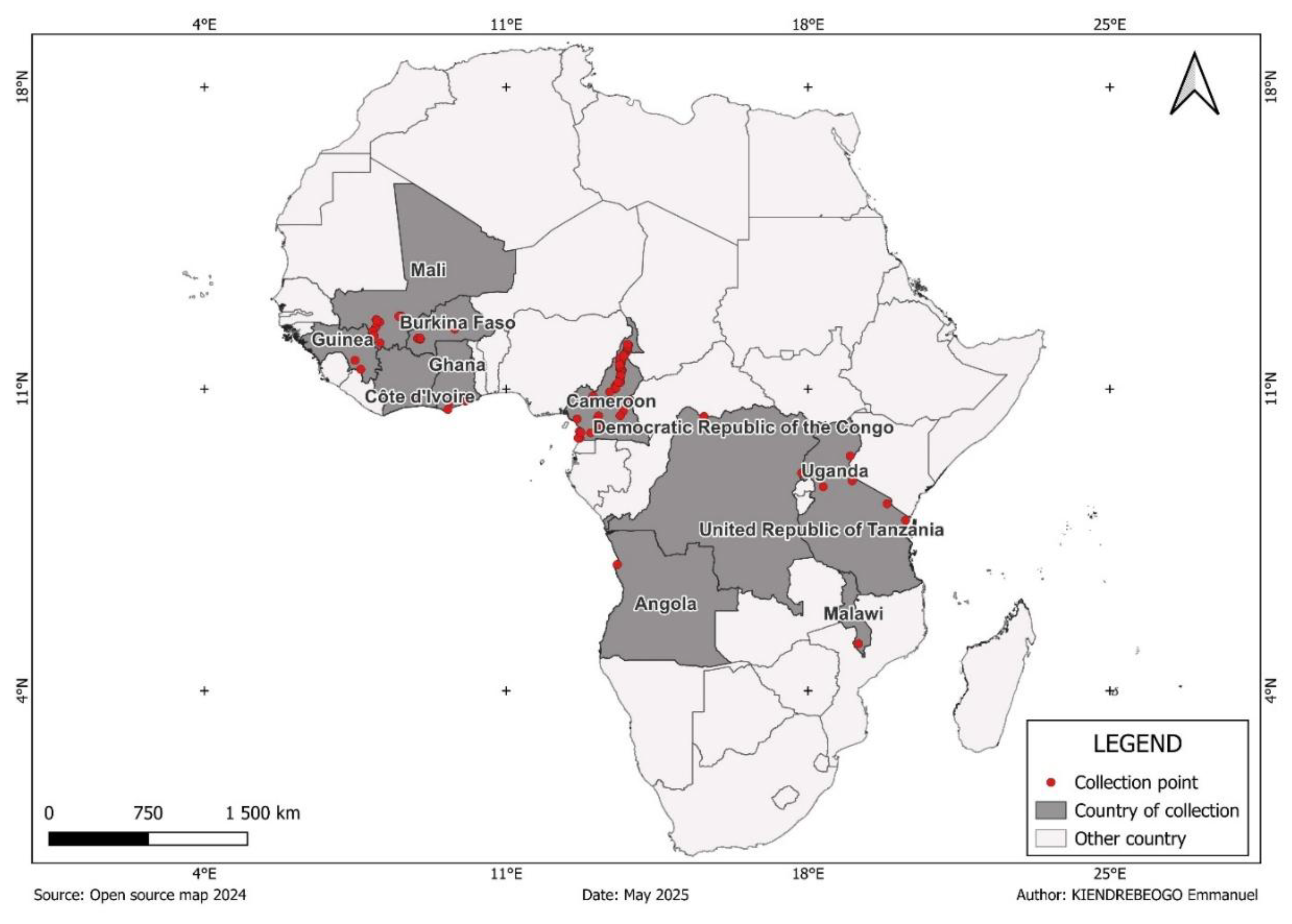

The genomic data used in this study are from the

Anopheles gambiae 1000 Genomes phase 3 Project (Ag1000G) called Ag3.0, published in February 2021 [

17]. Mosquitoes, including three

Anopheles species,

Anopheles gambiae,

Anopheles coluzzii and

Anopheles arabiensis, were collected between 2004 and 2015 in 11 countries across sub-Saharan Africa (

Figure 1,

Table S1). Details on mosquito sample collection, storage and management of the genomic data, including access rights are available on the homepage of MalariaGEN [

18].

Library preparation and sequencing were performed at the Wellcome Sanger Institute. All individuals were sequenced to a target coverage of 30× using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 and the Illumina HiSeq X platforms [

18].

Alignment, SNP calling and sample quality control (QC), were performed by the MalariaGEN Resource Centre Team. Reads were aligned to the AgamP4 reference genome using BWA version 0.7.15. GATK version 3.7-0 RealignerTargetCreator and IndelRealigner were used for Indel realignment while single nucleotide polymorphisms were called using GATK version 3.7-0 UnifiedGenotyper. Given all possible alleles at all genomic sites where the reference base was not “N”, genotypes were called for each sample independently. After variant calling, both the samples and the variants have undergone a series of quality control analyses, to ensure data quality [

18].

2.2. Detection of Genome Regions Under Recent Positive Selection and Identification of New Candidate Genes

Genome-wide scans for selection (GWSS) were performed on

Anopheles gambiae s.l. to detect signals of recent selection using the Garud H12 statistic [

16]. This statistic is sensitive to recent selection, making it ideal for detecting selective sweeps driven by recent insecticidal pressures. The analyses were first conducted at the country level, then at both country and species levels. For each analysis, the window size, defined by a specific number of SNPs, was calibrated to balance resolution and signal detection. Genomic regions under selective sweep were examined for insecticide resistance genes. Potential new candidates were identified through literature research using resources such as VectorBase, NCBI, and Google Scholar.

2.3. Genetic Variability

For each aldehyde oxidase gene, the transcript was identified. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified and grouped by their predictive effect. SNP frequencies within populations were determined, then filtered down to just non-synonymous SNPs that were at the highest frequencies. Copy number variation (CNV) was assessed by computing the frequencies of gene amplification and deletion across the aldehyde oxidase gene regions in the different populations.

Haplotype networks were built for the aldehyde oxidase genes and explored to find evidence of gene flow events between countries and species. Haplotypes carrying the main high frequency mutations were analyzed with a maximum genetic distance of two SNPs.

Population structure was analyzed using principal component analysis (PCA) and pairwise Fst estimates. Genetic diversity summary statistics were computed using SNPs called in the aldehyde oxidase genes region.

3. Results

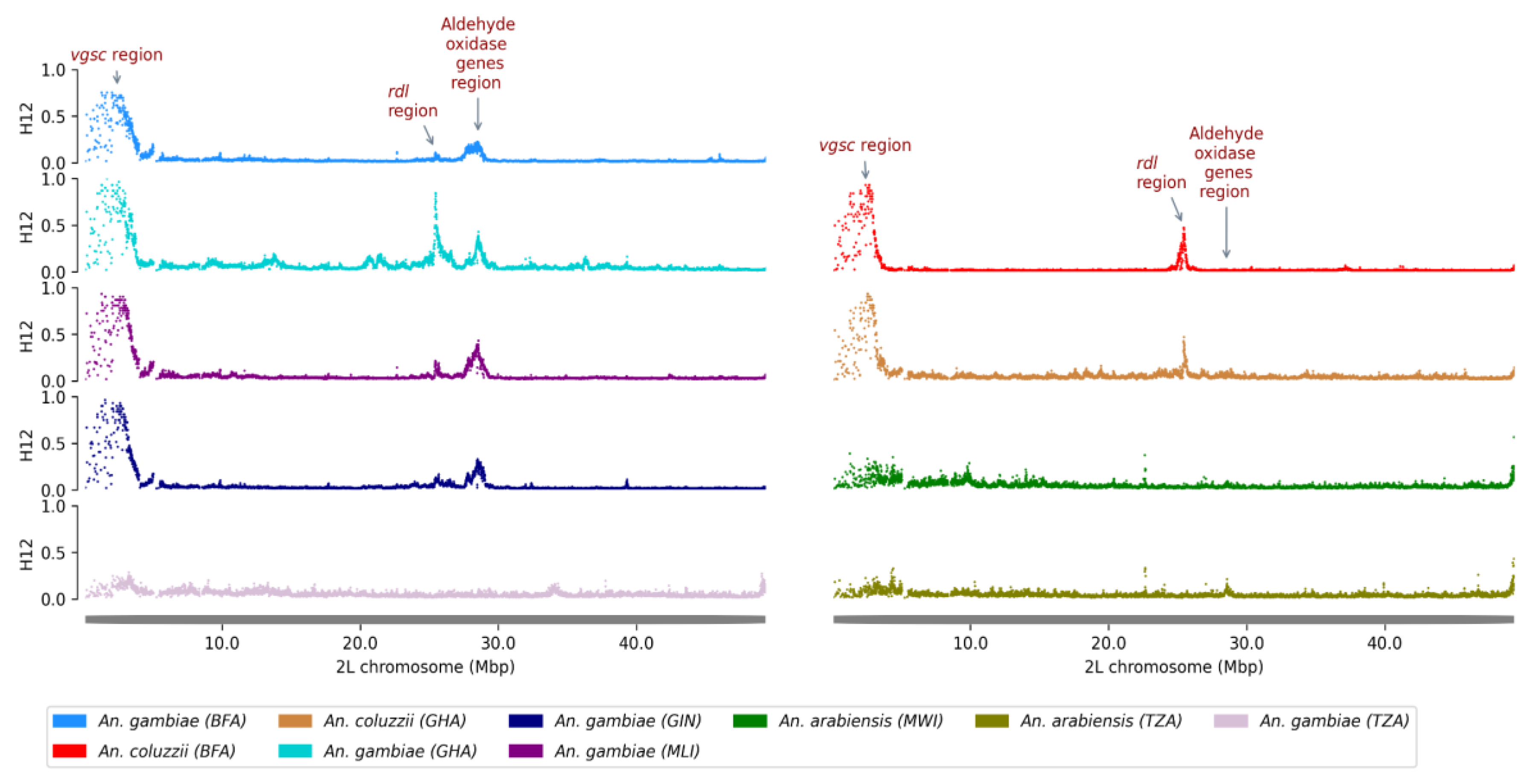

3.1. Signals of Positive Selection - Identification of Potential New Insecticide Resistance Genes

The analyses included a total of 1908 individual genomes from An. gambiae s.s., An. coluzzii and An. arabiensis. Genome-wide selection was conducted using the Garud H12 statistics in windows ranging from 1000 to 2000 SNPs depending on the population. The results revealed several peaks of H12 values across different chromosome arms. These peaks correspond to the genomic regions of Vgsc, Ace1, Rdl and GSTe3 genes, indicating selective sweeps likely due to positive selection in these areas, as previously observed in An. gambiae populations.

Beyond these well-characterized genes, high H12 values were observed in a new locus on chromosome 2L around positions 28,510,000 and 28,590,000, indicating a signal of positive selection in this region. This genomic region corresponds to a cluster of genes encoding detoxification enzymes, including five aldehyde oxidases (

AGAP006220,

AGAP006221,

AGAP006224,

AGAP006225,

AGAP006226), two glucosyl/glucuronosyl transferases (

AGAP006222,

AGAP006223), and two carboxylesterases (

AGAP006227,

AGAP006228). Additional population-specific scans were performed to determine the geographic and species-specific distribution of this selective sweep. In

Anopheles gambiae s.s, the sweep was detected in Burkina Faso, Ghana and Guinea. In

Anopheles arabiensis it was present in Tanzania and Malawi, but with relatively lower proportions. However, in

An. coluzzii the sweep was completely absent (

Figure 2).

We focused our further investigations on aldehyde oxidases, as three of them were located directly under the peak of the selective sweep and based on existing literature, appeared particularly promising as candidate insecticide resistance genes.

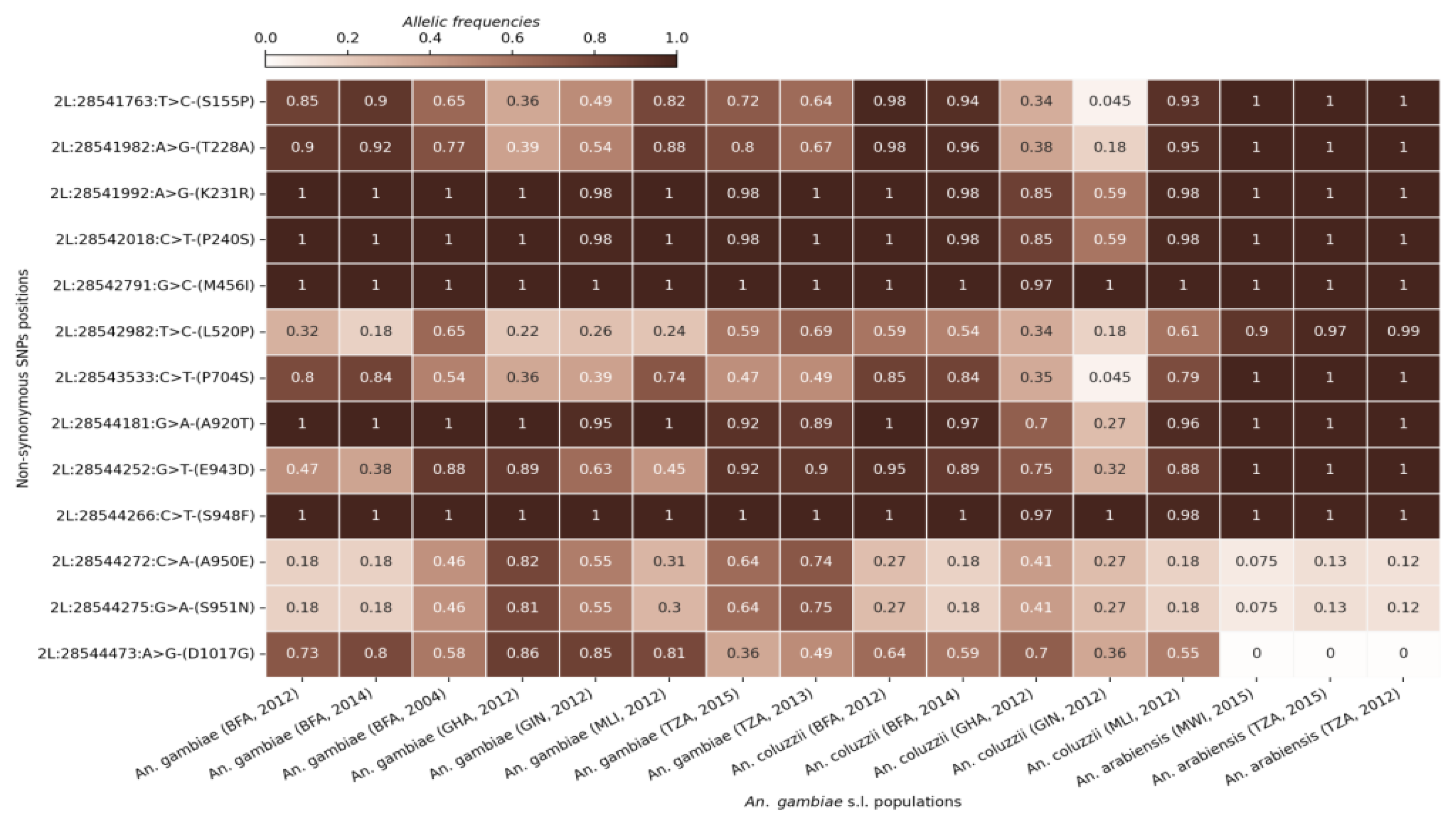

3.2. SNPs in the Aldehyde Oxidase Genes

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) variation was analysed in aldehyde oxidase genes across the five countries, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Guinea, Tanzania and Malawi where these genes were found to be under positive selection. All five genes exhibited a high density of polymorphism across the different populations. Specifically, we identified 2,202 SNPs (including 569 non-synonymous coding SNPs) in

AGAP006220, 2,661 SNPs (691 non-synonymous) in

AGAP006221, 2,698 SNPs (1,433 non-synonymous) in

AGAP006224, 2,515 SNPs (978 non-synonymous) in

AGAP006225, and 2,104 SNPs (811 non-synonymous) in

AGAP006226. The analyses identified a substantial number of non-synonymous coding SNPs at high frequencies across all five genes and in all three species, with some reaching 100% frequency in several cohorts. To focus on the most prevalent variants, the dataset was refined to include only those SNPs with minimum frequencies of 40, 50, or 75% in at least one sample cohort. The refinement showed 21 SNPs at frequencies higher than 40% in AGAP006220 and AGAP006225, and 56 SNPs above 75% in AGAP006221, AGAP006224 and AGAP006226 (

Figure 3,

Figures S1–S4). These patterns suggest that these variants might be under strong selective pressure and could play an important role in the adaptation of malaria vectors to environmental changes such as insecticide resistance.

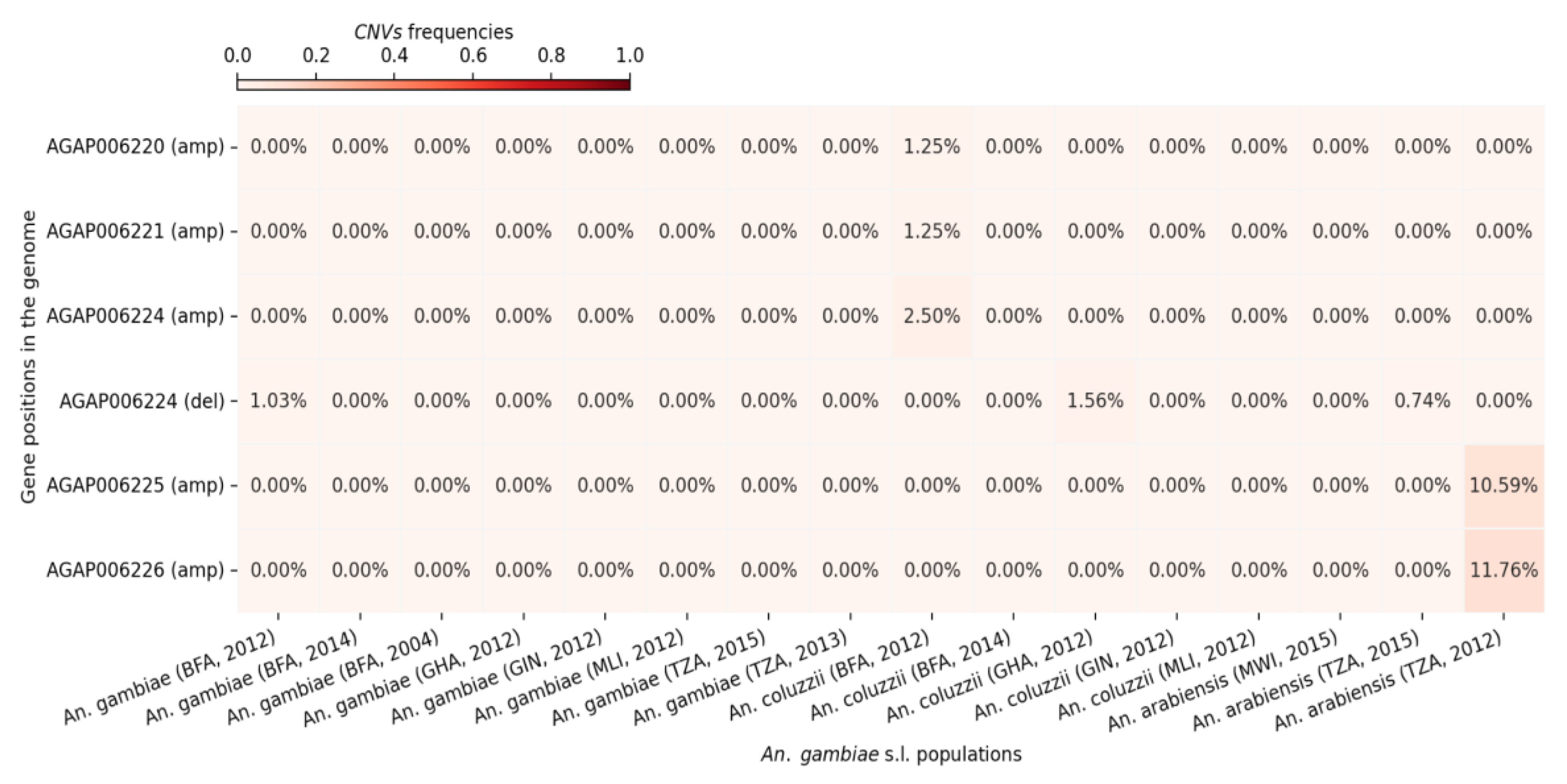

3.3. CNVs in the Aldehyde Oxidase Genes

CNV frequencies were analysed in the five aldehyde oxidase genes across populations from Burkina Faso, Ghana, Guinea, Tanzania, and Malawi. The analysis revealed the presence of CNVs in all five genes. Deletions were detected only in

AGAP006224, while amplifications were observed in all five genes. Overall, amplification frequencies were low (≤3%) across most of the genes and populations, with the exception of

Anopheles arabiensis from Tanzania, where

AGAP006225 and

AGAP006226 exhibited amplification rates of 10.59% and 11.76%, respectively (

Figure 4).

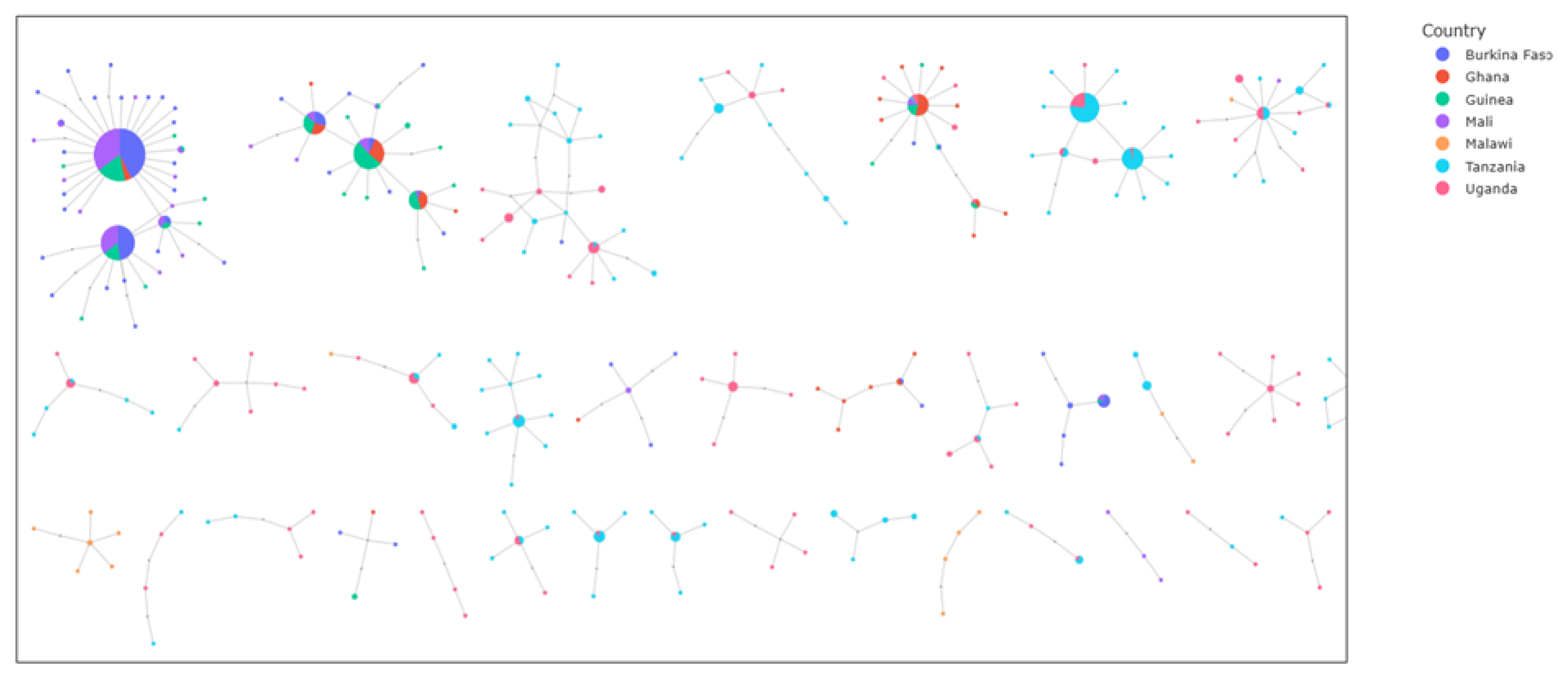

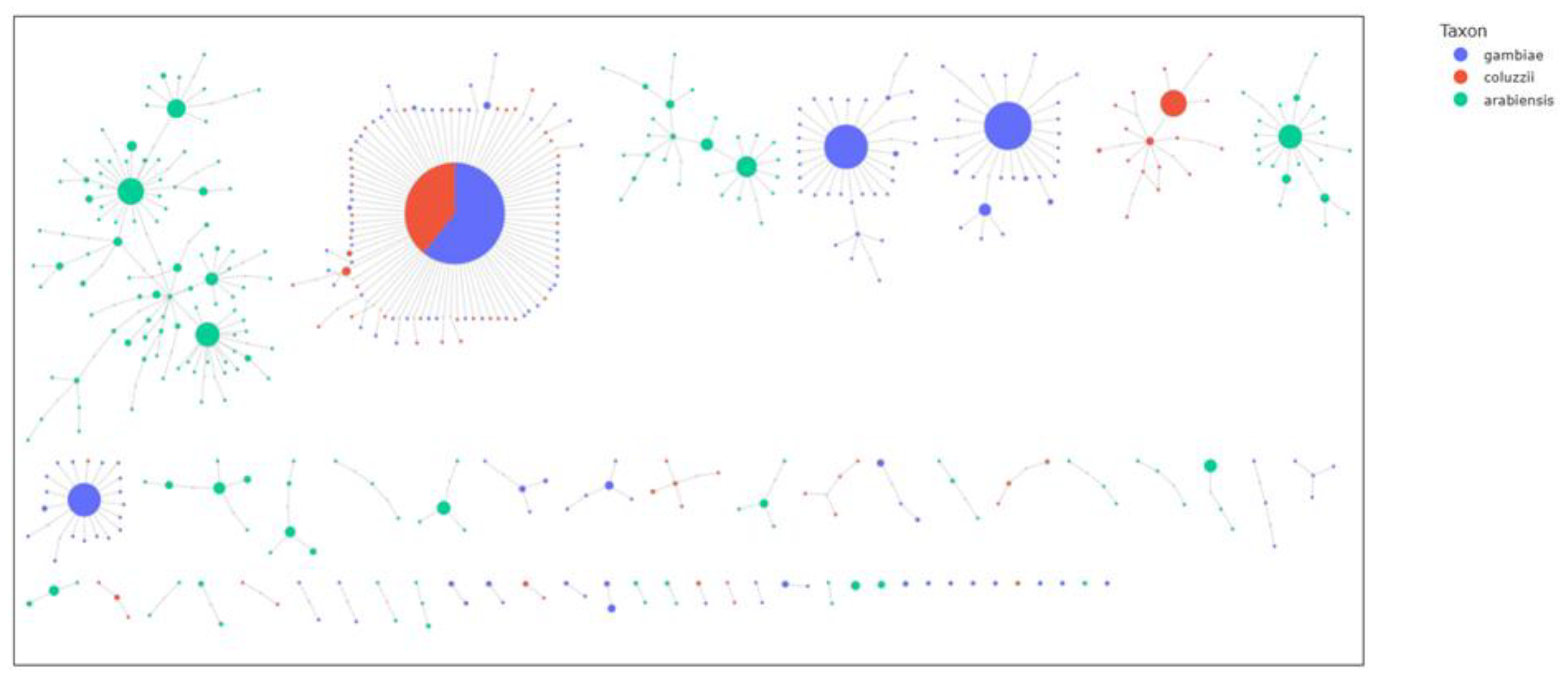

3.4. Gene Flow, Population Structure, and Genetic Diversity at the Aldehyde Oxidases Locus

To investigate gene flow at the aldehyde oxidases locus, haplotype network technique was used to visualize the relationships between haplotypes from different species and countries and show how variants are shared between populations. The results showed strong signs of adaptive gene flow between

Anopheles gambiae s.l. populations in West Africa, as well as between populations of East Africa. Specifically, in West Africa, the largest network comprised 163 identical haplotypes shared across all the vector populations. Similarly, the same pattern is observed in East Africa, with 52 identical haplotypes shared between

An. gambiae s.l. populations from Tanzania and Uganda (

Figure 5). Inter-species gene flow was also evident with a large haplotype cluster of 1001 identical sequences shared between

Anopheles gambiae (n = 609) and

Anopheles coluzzii (n = 392), indicating strong evidence for adaptive gene flow between these two species. However, no shared haplotypes were detected between

An. arabiensis and either

An. gambiae or

An. coluzzii (

Figure 6).

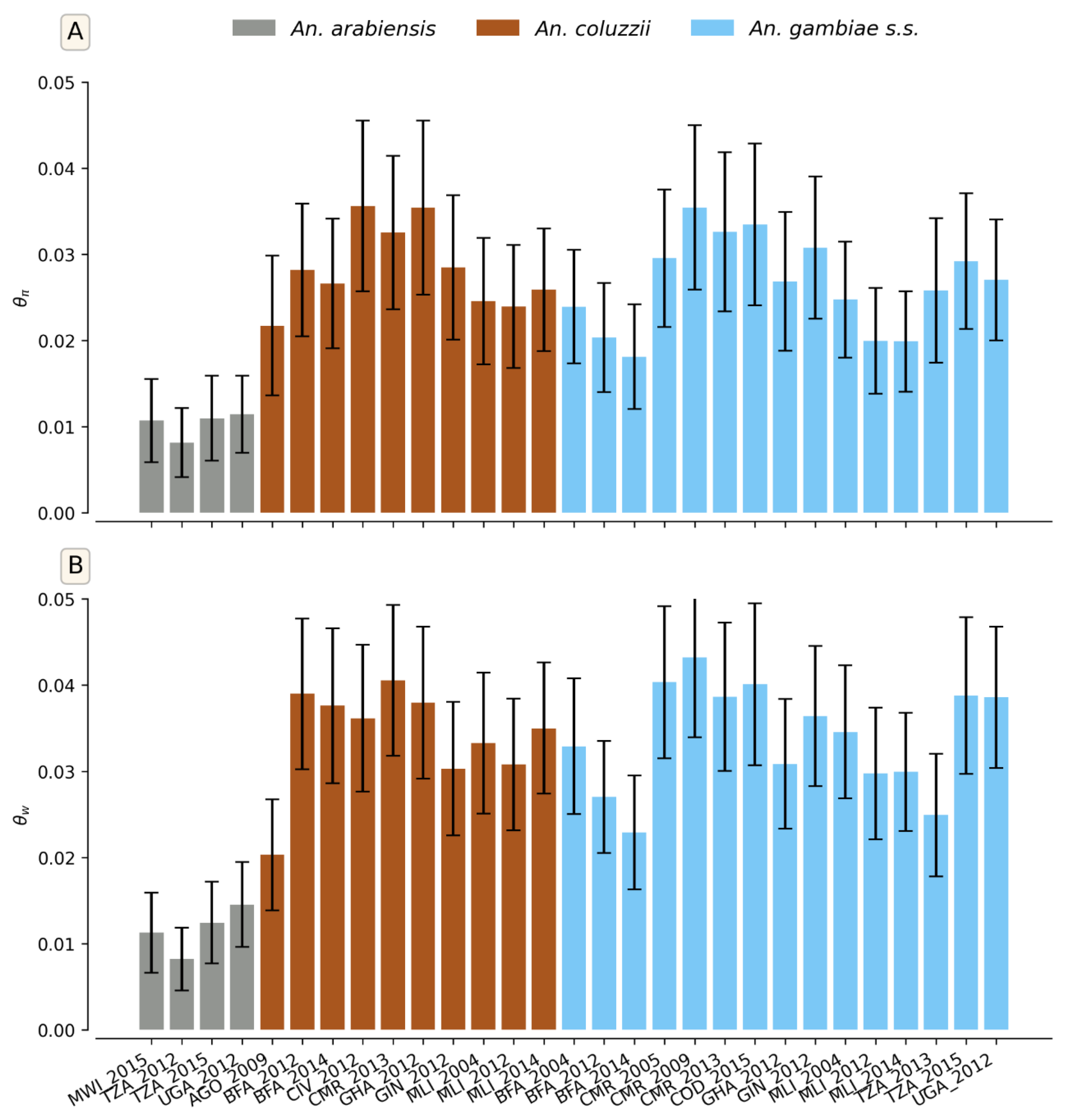

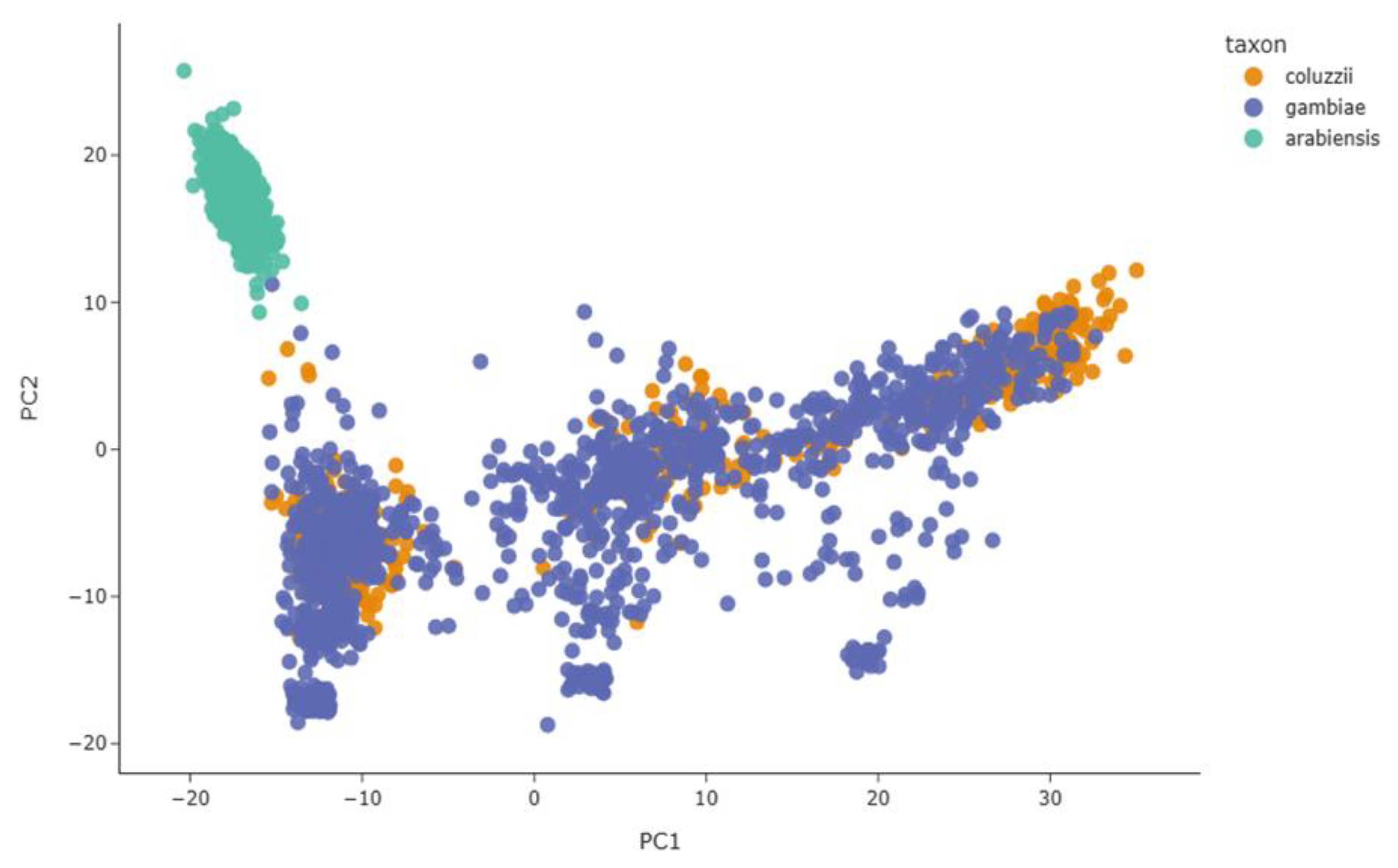

These patterns were supported by population structure and genetic diversity analyses conducted at the aldehyde oxidases locus across the 11 countries. The principal component analysis (PCA) showed a distinct and homogeneous cluster of

An. arabiensis, whereas

An. gambiae and

An. coluzzii clustered together, further supporting genetic exchange between these two species (Figure 8). The genetic differences (

FST) between

An. arabiensis and the two other species were generally higher than those observed between

An. gambiae and

An. coluzzii, indicating greater genetic differentiation (

Figure S5). The results were confirmed by diversity indices, although some variation existed within species. Both measures of diversity (θπ and θw) showed similar results for

An. gambiae and

An. coluzzii compared to

An. arabiensis (

Figure 7). These results suggest a similar demographic history for

An. gambiae and

An. coluzzii.

Figure 7.

Genetic diversity statistics of An. gambiae s.l. populations at aldehyde oxidases locus. A. Nucleotide diversity (θπ). B. Watterson theta (θw). The X-axis shows the different cohorts (country/sampling period/species): AGO=Angola, BFA=Burkina Faso, CIV=Côte d’Ivoire, CMR=Cameroon, COD=Democratic Republic of Congo, GHA=Ghana, GIN=Guinea, MLI=Mali, MWI=Malawi, TZA=Tanzania, UGA=Uganda.

Figure 7.

Genetic diversity statistics of An. gambiae s.l. populations at aldehyde oxidases locus. A. Nucleotide diversity (θπ). B. Watterson theta (θw). The X-axis shows the different cohorts (country/sampling period/species): AGO=Angola, BFA=Burkina Faso, CIV=Côte d’Ivoire, CMR=Cameroon, COD=Democratic Republic of Congo, GHA=Ghana, GIN=Guinea, MLI=Mali, MWI=Malawi, TZA=Tanzania, UGA=Uganda.

Figure 8.

Principal component analysis of An. gambiae s.l. populations at aldehyde oxidases locus. X-axis shows the first principal component (PC1) and Y-axis the second principal component (PC2).

Figure 8.

Principal component analysis of An. gambiae s.l. populations at aldehyde oxidases locus. X-axis shows the first principal component (PC1) and Y-axis the second principal component (PC2).

4. Discussion

Malaria control remains a major challenge in sub-Saharan Africa. Despite ongoing interventions, the region still bears the highest global burden of the disease due to complicating factors such as insecticide resistance, changing vector behaviour and rapid urbanization [

2,

19]. However, strengthening surveillance, particularly through genomic tools, offers new opportunities to enhance the effectiveness of vector control strategies [

20]. In particular, discovering new resistance genes is crucial for controlling malaria effectively by enabling early detection and monitoring within malaria vector populations. These insights help guide and inform the selection and rotation of insecticides, reducing the spread of the resistance variants [

21]. Recent advances in genomics offer valuable opportunities to study the genomic architecture and evolution of malaria vectors, enabling high-resolution mapping of resistance genes, population structure, and adaptive evolution [

21,

22].

Our study detected a signal of positive selection within the aldehyde oxidase genes in

An. gambiae and

An. arabiensis populations across sub-Saharan Africa. The absence of positive selection in

An. coluzzii supports recent findings on the carboxylesterases

Coeae1f and

Coeae2f, which, as previously mentioned, are located on the same locus [

23]. Aldehyde oxidases are indeed known for their broad substrate specificity and marked species differences [

24].

Our results suggest that aldehyde oxidase genes may play an important role in how malaria vectors adapt to environmental changes, such as those caused by insecticide-based vector control tools. Aldehyde oxidase is a cytosolic enzyme that belongs to the family of structurally related molybdo flavoproteins like xanthine oxidase. These enzymes have originated from gene duplication events of an ancestral eukaryotic xanthine oxidoreductase gene found in the flatworm,

Caenorhabditis elegans [

24]. Aldehyde oxidases are common enzymes involved in detoxifying and breaking down many substances across various organisms. Although references to aldehyde oxidase and its role in metabolism date back to the 1950s [

24], the significance of this enzyme in insecticide metabolism has only emerged in recent years [

25]. Like cytochromes P450, aldehyde oxidases contribute to oxidation by carrying out nucleophilic attacks using oxygen derived from water [

26]. Previous studies have characterised these enzymes in

Culex mosquitoes. Investigations into resistant Culex strains showed elevated levels of aldehyde oxidase activity, suggesting that these enzymes may confer a selective advantage in the presence of insecticides [

27,

28]. Beyond

Culex species, growing evidence indicates that aldehyde oxidases may also contribute to insecticide resistance in

An. gambiae s.l. In fact, previous studies have shown that aldehyde oxidases are co-amplified with insecticide resistance-associated esterases. These esterases have been recently demonstrated in association with resistance to pirimiphos-methyl in

An. gambiae s.l. populations [

23,

27]. Furthermore, aldehyde oxidases might play a role in resistance to neonicotinoid insecticides. In vitro studies have shown their capacity to metabolize neonicotinoids such as imidacloprid, thiamethoxam, clothianidin, and dinotefuran [

29],indicating their potential involvement in resistance to this newer class of insecticides. This is particularly relevant given the growing interest in neonicotinoids as alternative tools for vector control in areas where resistance to multiple insecticide classes is already widespread [

30].

These observations are consistent with our results, which, in addition to positive selection, showed increased frequency of non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and copy number variations (CNVs), including gene amplifications in the genomic region of aldehyde oxidase genes. Indeed, SNPs and CNVs have been identified as playing significant role in the evolution of insecticide resistance [

31,

32,

33,

34]. These variants are particularly important in metabolic resistance because they can lead to increased gene expression [

3,

35]. However, given the low frequencies of CNVs observed, we hypothesize that the resistance ultimately induced by these detoxification genes would be more closely linked to SNPs, which were detected at high frequencies. This hypothesis is supported by previous studies showing that SNPs are a key genetic factor influencing variation in aldehyde oxidase expression and active protein levels [

24].

The adaptive introgression observed between

An. gambiae and

An. coluzzii aligns with previous studies demonstrating a high potential for genetic exchange between these two closely related species [

22]. Although no significant selective sweep was detected in

An. coluzzii, the ongoing and increasing gene flow suggests that aldehyde oxidase genes may eventually come under selective pressure in this species as well. Given the spatial patterns of gene flow observed in both study regions, these putative resistance markers are expected to expand to large areas across the continent.

This study highlighted the ongoing evolution of the An. gambiae complex genome in response to environmental pressures and vector control interventions. Genomic changes, including mutations and gene duplications, are driven by factors such as exposure to insecticides, environmental changes and ecological shifts. These evolutionary processes can lead to increased resistance and altered behaviour, which complicate malaria control efforts. Therefore, continuous genomic surveillance is crucial to track and effectively respond to these changes.

5. Conclusions

This study highlighted the importance of genomic data in malaria surveillance. Genomic surveillance can identify how insecticide resistance develops in malaria-transmitting mosquitoes and help guide the deployment of new vector-control tools with multiple modes of action. The results of this study highlighted a cluster of genes that may be associated with insecticide resistance in An. gambiae s.l. populations in Africa. Indeed, the study identified a previously unreported locus, consisting of detoxifying genes encoding aldehyde oxidases, under recent positive selection in An. gambiae s.l. populations. While the involvement of aldehyde oxidases in insecticide resistance has been studied in Culex mosquitoes, our findings provide the first hypothesis supporting the potential role of these genes in the adaptation of An. gambiae s.l to the environmental changes. Genetic variation analyses further support this hypothesis by revealing both copy number variations (CNVs) and high-frequency non-synonymous SNPs within these genes.

Further studies, including gene expression and functional validation, are needed to confirm the role of aldehyde oxidases in insecticide resistance in An. gambiae s.l. If proven, these genes could serve as novel molecular markers to be integrated into resistance monitoring programs, contributing to more effective and adaptive vector control strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Study sites, collection year and species composition; Figure S1: SNP allele frequencies in the AGAP006220 gene in the different An. gambiae s.l. populations; Figure S2 : SNP allele frequencies in the AGAP006221 gene in the different An. gambiae s.l. populations; Figure S3: SNP allele frequencies in the AGAP006224 gene in the different An. gambiae s.l. populations; Figure S4 : SNP allele frequencies in the AGAP006225 gene in the different An. gambiae s.l. populations; Figure S5: Pairwise Fst estimates between different Anopheles gambiae s.l. populations based on the aldehyde oxidase locus.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.D.K. and M.K.; methodology, H.D.K and M.K.; software, H.D.K. and M.K.; validation, M.K. and H.M.; formal analysis, H.D.K. and M.K.; investigation, H.D.K.; resources, A.D.; data curation, H.D.K. and M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, H.D.K.; writing—review and editing, H.D.K., M.K., S.O.G.Y., N.T., K.B., H.M.; visualization, M.K.; supervision, M.K., N.T., K.B., H.M., M.N., A.D.; project administration, A.D.; funding acquisition, A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Pan-African Mosquito Control Association, grant number OPP1214408, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, grant number INV-037164 and the Wellcome Trust, grant number UNS-128536.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Jupyter Notebooks and scripts to reproduce all the analyses, tables and figures are available in the GitHub repository:

https://github.com/HyacintheKi/aldehyde_data. The SNPs and haplotypes data are available on the homepage of MalariaGEN and can be accessed using the malariagen_data package. The raw sequences in FASTQ format and the aligned sequences in BAM format were stored in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA, Study Accession n° PRJEB42254)

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Ag1000G Consortium for making thePhase 3 dataset publicly available. The authors are particularly grateful to the MalariaGEN Vector Observatory which is an international collaboration working to build capacity for malaria vector genomic research and surveillance. We benefited from training in data analysis for genomic surveilance, organised by MalariaGEN in collaboration with Wellcome Sanger Institute and Pan-African Mosquito Control Association. This training was decisive for the completion of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Venkatesan, P. The 2023 WHO World Malaria Report. The Lancet Microbe 2024, 5, e214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wondji, C.S.; Hearn, J.; Irving, H.; Wondji, M.J.; Weedall, G. RNAseq-Based Gene Expression Profiling of the Anopheles funestus Pyrethroid-Resistant Strain FUMOZ Highlights the Predominant Role of the Duplicated CYP6P9a/b Cytochrome P450s. G3 (Bethesda) 2021, 12, jkab352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemingway, J.; Hawkes, N.J.; McCarroll, L.; Ranson, H. The Molecular Basis of Insecticide Resistance in Mosquitoes. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 2004, 34, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranson, H.; N’Guessan, R.; Lines, J.; Moiroux, N.; Nkuni, Z.; Corbel, V. Pyrethroid Resistance in African Anopheline Mosquitoes: What Are the Implications for Malaria Control? Trends in Parasitology 2011, 27, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouhamadou, C.S.; de Souza, S.S.; Fodjo, B.K.; Zoh, M.G.; Bli, N.K.; Koudou, B.G. Evidence of Insecticide Resistance Selection in Wild Anopheles coluzzii Mosquitoes Due to Agricultural Pesticide Use. Infectious Diseases of Poverty 2019, 8, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouamé, R.M.A.; Lynd, A.; Kouamé, J.K.I.; Vavassori, L.; Abo, K.; Donnelly, M.J.; Edi, C.; Lucas, E. Widespread Occurrence of Copy Number Variants and Fixation of Pyrethroid Target Site Resistance in Anopheles gambiae (s.l.) from Southern Côte d’Ivoire. Curr Res Parasitol Vector Borne Dis 2023, 3, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, P.F.; Elanga-Ndille, E.; Tchouakui, M.; Sandeu, M.M.; Tagne, D.; Wondji, C.; Ndo, C. Impact of Insecticide Resistance on Malaria Vector Competence: A Literature Review. Malar J 2023, 22, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, S.S.; Muhammad, A.; Hearn, J.; Weedall, G.D.; Nagi, S.C.; Mukhtar, M.M.; Fadel, A.N.; Mugenzi, L.J.; Patterson, E.I.; Irving, H.; et al. Molecular Drivers of Insecticide Resistance in the Sahelo-Sudanian Populations of a Major Malaria Vector Anopheles coluzzii. BMC Biol 2023, 21, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Schuler, M.A.; Berenbaum, M.R. Molecular Mechanisms of Metabolic Resistance to Synthetic and Natural Xenobiotics. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2007, 52, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynd, A.; Weetman, D.; Barbosa, S.; Egyir Yawson, A.; Mitchell, S.; Pinto, J.; Hastings, I.; Donnelly, M.J. Field, Genetic, and Modeling Approaches Show Strong Positive Selection Acting upon an Insecticide Resistance Mutation in Anopheles gambiae s.s. Mol Biol Evol 2010, 27, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toé, K.H.; N’Falé, S.; Dabiré, R.K.; Ranson, H.; Jones, C.M. The Recent Escalation in Strength of Pyrethroid Resistance in Anopheles coluzzi in West Africa Is Linked to Increased Expression of Multiple Gene Families. BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, E.R.; Nagi, S.C.; Egyir-Yawson, A.; Essandoh, J.; Dadzie, S.; Chabi, J.; Djogbénou, L.S.; Medjigbodo, A.A.; Edi, C.V.; Kétoh, G.K.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Studies Reveal Novel Loci Associated with Pyrethroid and Organophosphate Resistance in Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles coluzzii. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancock, P.A.; Ochomo, E.; Messenger, L.A. Genetic Surveillance of Insecticide Resistance in African Anopheles Populations to Inform Malaria Vector Control. Trends in Parasitology 2024, 40, 604–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, M.J.; Isaacs, A.T.; Weetman, D. Identification, Validation and Application of Molecular Diagnostics for Insecticide Resistance in Malaria Vectors. Trends Parasitol 2016, 32, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, A.T.; Schrider, D.R.; Kern, A.D.; Consortium, A. Discovery of Ongoing Selective Sweeps within Anopheles Mosquito Populations Using Deep Learning 2020, 589069.

- Garud, N.R.; Messer, P.W.; Buzbas, E.O.; Petrov, D.A. Recent Selective Sweeps in North American Drosophila melanogaster Show Signatures of Soft Sweeps. PLoS Genet 2015, 11, e1005004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consortium, T.A. gambiae 1000 G. Genome Variation and Population Structure in Three African Malaria Vector Species within the *Anopheles gambiae* Complex; Manubot, 2021.

- Ag3.0 (Ag1000G Phase 3) — MalariaGEN Vector Data User Guide. Available online: https://malariagen.github.io/vector-data/ag3/ag3.0.html (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Merga, H.; Degefa, T.; Birhanu, Z.; Tadele, A.; Lee, M.-C.; Yan, G.; Yewhalaw, D. Urban Malaria in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Scoping Review of Epidemiologic Studies. Malar J 2025, 24, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nsanzabana, C. Strengthening Surveillance Systems for Malaria Elimination by Integrating Molecular and Genomic Data. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 2019, 4, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarkson, C.S.; Temple, H.J.; Miles, A. The Genomics of Insecticide Resistance: Insights from Recent Studies in African Malaria Vectors. Curr Opin Insect Sci 2018, 27, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kientega, M.; Clarkson, C.S.; Traoré, N.; Hui, T.-Y.J.; O’Loughlin, S.; Millogo, A.-A.; Epopa, P.S.; Yao, F.A.; Belem, A.M.G.; Brenas, J.; et al. Whole-Genome Sequencing of Major Malaria Vectors Reveals the Evolution of New Insecticide Resistance Variants in a Longitudinal Study in Burkina Faso. Malaria Journal 2024, 23, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagi, S.C.; Lucas, E.R.; Egyir-Yawson, A.; Essandoh, J.; Dadzie, S.; Chabi, J.; Djogbénou, L.S.; Medjigbodo, A.A.; Edi, C.V.; Ketoh, G.K.; et al. Parallel Evolution in Mosquito Vectors – a Duplicated Esterase Locus Is Associated with Resistance to Pirimiphos-Methyl in An. gambiae. bioRxiv 2024. [CrossRef]

- Garattini, E.; Fratelli, M.; Terao, M. The Mammalian Aldehyde Oxidase Gene Family. Hum Genomics 2009, 4, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Shen, G.; Mao, X.; Jiao, M.; Lin, Y. Identification and Characterization of Aldehyde Oxidase 5 in the Pheromone Gland of the Silkworm (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae). J Insect Sci 2020, 20, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy, R.; Mutis, A.; Carabajal Paladino, L.; Venthur, H. Genome-Wide Identification of Aldehyde Oxidase Genes in Moths and Butterflies Suggests New Insights Into Their Function as Odorant-Degrading Enzymes. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Significance of Aldehyde Oxidase during Drug Development: Effects on Drug Metabolism, Pharmacokinetics, Toxicity, and Efficacy. Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics 2015, 30, 52–63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemingway, J. The Molecular Basis of Two Contrasting Metabolic Mechanisms of Insecticide Resistance. Insect biochemistry and molecular biology 2000, 30, 1009–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, M.; Vontas, J.G.; Hemingway, J. Molecular Characterization of the Amplified Aldehyde Oxidase from Insecticide Resistant Culex quinquefasciatus. European Journal of Biochemistry 2002, 269, 768–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexton, J.P.; Clemens, M.; Bell, N.; Hall, J.; Fyfe, V.; Hoffmann, A.A. Patterns and Effects of Gene Flow on Adaptation across Spatial Scales: Implications for Management. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 2024, 37, 732–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarkson, C.S.; Miles, A.; Harding, N.J.; O’Reilly, A.O.; Weetman, D.; Kwiatkowski, D.; Donnelly, M.J. The Genetic Architecture of Target-site Resistance to Pyrethroid Insecticides in the African Malaria Vectors Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles coluzzii. Mol Ecol 2021, 30, 5303–5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stica, C.; Jeffries, C.L.; Irish, S.R.; Barry, Y.; Camara, D.; Yansane, I.; Kristan, M.; Walker, T.; Messenger, L.A. Characterizing the Molecular and Metabolic Mechanisms of Insecticide Resistance in Anopheles gambiae in Faranah, Guinea. Malar J 2019, 18, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.M.; Liyanapathirana, M.; Agossa, F.R.; Weetman, D.; Ranson, H.; Donnelly, M.J.; Wilding, C.S. Footprints of Positive Selection Associated with a Mutation (N1575Y) in the Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel of Anopheles gambiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, 6614–6619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouet, C.; Ashu, F.A.; Ambadiang, M.M.; Tchapga, W.; Wondji, C.S.; Kamdem, C. Clothianidin-Resistant Anopheles gambiae Adult Mosquitoes from Yaoundé, Cameroon, Display Reduced Susceptibility to SumiShield® 50WG, a Neonicotinoid Formulation for Indoor Residual Spraying. BMC Infect Dis 2024, 24, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dick, R.A.; Kanne, D.B.; Casida, J.E. Substrate Specificity of Rabbit Aldehyde Oxidase for Nitroguanidine and Nitromethylene Neonicotinoid Insecticides. Chem Res Toxicol 2006, 19, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Countries and collection sites.

Figure 1.

Countries and collection sites.

Figure 2.

H12 statistic on the 2L chromosomal arm of mosquitoes from Burkina Faso (BFA), Ghana (GHA), Mali (MLI), Guinea (GIN), Malawi (MWI) and Tanzania (TZA). Selective sweeps are suggested by peaks. A cluster of five aldehyde oxidases was found under positive selection in An. gambiae and An. arabiensis : AGAP006220 (2L:28,512,602-28,517,680), AGAP006221 (2L:28,518,055-28,523,900), AGAP006224 (2L:28,528,758-28,533,199), AGAP006225 (2L:28,534,732-28,539,416), AGAP006226 (2L:28,540,651-28,545,294).

Figure 2.

H12 statistic on the 2L chromosomal arm of mosquitoes from Burkina Faso (BFA), Ghana (GHA), Mali (MLI), Guinea (GIN), Malawi (MWI) and Tanzania (TZA). Selective sweeps are suggested by peaks. A cluster of five aldehyde oxidases was found under positive selection in An. gambiae and An. arabiensis : AGAP006220 (2L:28,512,602-28,517,680), AGAP006221 (2L:28,518,055-28,523,900), AGAP006224 (2L:28,528,758-28,533,199), AGAP006225 (2L:28,534,732-28,539,416), AGAP006226 (2L:28,540,651-28,545,294).

Figure 3.

SNP allele frequencies in the AGAP006226 gene in the different An. gambiae s.l. populations. The X-axis shows the different cohorts (country, species and sampling period). The Y-axis shows the SNPs positions in the gene and the corresponding amino acid change. The gradient color bar shows the distribution of the allelic frequencies.

Figure 3.

SNP allele frequencies in the AGAP006226 gene in the different An. gambiae s.l. populations. The X-axis shows the different cohorts (country, species and sampling period). The Y-axis shows the SNPs positions in the gene and the corresponding amino acid change. The gradient color bar shows the distribution of the allelic frequencies.

Figure 4.

CNVs frequencies at the aldehyde oxidases genes in the different An. gambiae s.l. populations. The X-axis shows the different cohorts (country, species and sampling period). The Y-axis shows the genes ID and the CNV type (del: deletion or amp: amplification). The gradient color bar shows the distribution of the CNVs frequencies.

Figure 4.

CNVs frequencies at the aldehyde oxidases genes in the different An. gambiae s.l. populations. The X-axis shows the different cohorts (country, species and sampling period). The Y-axis shows the genes ID and the CNV type (del: deletion or amp: amplification). The gradient color bar shows the distribution of the CNVs frequencies.

Figure 5.

Haplotype networks in five aldehyde oxidases (AGAP006220, AGAP006221, AGAP006224, AGAP006225 and AGAP006226) showing gene flow between countries. Identical haplotypes are represented by nodes (circles). The larger the node, the greater the number of identical haplotypes. Maximum distance set to two i.e., each node is separated by a maximum genetic distance of 2 SNPs. Color indicates the country.

Figure 5.

Haplotype networks in five aldehyde oxidases (AGAP006220, AGAP006221, AGAP006224, AGAP006225 and AGAP006226) showing gene flow between countries. Identical haplotypes are represented by nodes (circles). The larger the node, the greater the number of identical haplotypes. Maximum distance set to two i.e., each node is separated by a maximum genetic distance of 2 SNPs. Color indicates the country.

Figure 6.

Haplotype networks in five aldehyde oxidases (AGAP006220, AGAP006221, AGAP006224, AGAP006225 and AGAP006226) showing gene flow between species. Identical haplotypes are represented by nodes (circles). The larger the node, the greater the number of identical haplotypes. Maximum distance set to two i.e., each node is separated by a maximum genetic distance of 2 SNPs. Color indicates the species.

Figure 6.

Haplotype networks in five aldehyde oxidases (AGAP006220, AGAP006221, AGAP006224, AGAP006225 and AGAP006226) showing gene flow between species. Identical haplotypes are represented by nodes (circles). The larger the node, the greater the number of identical haplotypes. Maximum distance set to two i.e., each node is separated by a maximum genetic distance of 2 SNPs. Color indicates the species.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).