1. Introduction

Arctic biological soil crusts (biocrusts) play crucial roles in harsh environments, with fungi contributing significantly to nutrient cycling and soil stabilization [

1]. Fungi in biocrusts decompose organic matter, mineralize nutrients, and form symbiotic relationships with phototrophic organisms, impacting both biocrust productivity and soil structure. Arctic fungi exhibit remarkable adaptations, possessing cold-active enzymes, melanized cell walls for UV resistance, and specialized water retention strategies [

2,

3]. These traits enhance their survival under environmental stress and shape community composition along altitude and environmental gradients.

While studies have documented the altitudinal responses of phototrophic biocrust members, the patterns and drivers of fungal diversity and function across elevation gradients in the Arctic remain poorly understood. We hypothesize that increasing elevation, and the associated changes in temperature, moisture, and radiation, will select for fungal taxa with traits conferring greater stress tolerance (e.g., melanization, psychrotolerance, production of extracellular polysaccharides), leading to shifts in both taxonomic composition and functional profiles. By integrating community profiling with functional trait analysis, our aim is to provide new insights into how Arctic fungi contribute to biocrust resilience and ecosystem functioning under varying environmental conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

Site descriptions, sampling procedures, chemical parameters, and phototrophic community composition were previously described in [

4]. In summary, biocrust samples were collected during the summers of 2022 and 2023 from three localities in Kongsfjorden (Svalbard), selected to represent a spatial gradient from the open sea toward the inner parts of the fjord: Outer Fjord (OF; Geop, Knau, Kn), Mid Fjord (MF; Knud, Bl), and Inner Fjord (IF; Gr, Os), each comprising low and high elevation sites (marked as L and H, respectively). The most common vascular plants included

Dryas octopetala,

Salix polaris,

Saxifraga oppositifolia,

Carex sp.,

Silene acaulis, and

Bistorta vivipara. The collected biocrusts were well-developed and comprised lichens and bryophytes, with their abundance varying by elevation. Five replicates were collected from each site and the total DNA was extracted and subsequently sequenced using the Illumina NovaSeq6000 platform (PE150). The raw reads were submitted to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the project PRJNA1124630.

Bioinformatic analysis was performed using the OmicsBox software (Biobam, Spain), and the reads were quality-filtered using Trimmomatic [

5]. The taxonomic classification of the fungi was executed using the UNITE database (v10.0). Fungi were further divided into the functional guilds based on their primary lifestyle using the FungalTraits database [

6]. Genes were predicted with MetaEuk on the Galaxy platform and functionally annotated using EggNOG (v5.0.2; Huerta-Cepas et al., 2017). Differential abundance of KEGG metabolic pathways between low- and high-elevation samples was assessed with a false discovery rate (FDR) cut-off of 0.05 and a log fold change threshold of –2 to +2.

Statistical analyses were carried out in R (version 4.2.1). To test for differences among the sampling sites, one and two-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were conducted, followed by Tukey's HSD post hoc test (p-value < 0.05). Normality of variance was assessed using Shapiro–Wilk's test. If necessary, data were Log or SQRT transformed. Furthermore, to illustrate the distribution of fungal reads, non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) was performed using the package vegan [

8] and statistical difference was tested with the ANOSIM test. Soil parameters were fitted into the ordination space using the function envfit and significance of the associations was determined by 999 random permutations.

3. Results and Discussion

The majority of the fungal reads in all samples were assigned to the Ascomycota across the samples (40-81% of fungal reads;

Supplementary Figure S1). Basidiomycota (3-29% of fungal reads) and Rozellomycota (3-18% of fungal reads) were also the dominant fungal phyla, as found in previous studies of Arctic biocrusts [

9]. The relative abundance of the majority of fungal phyla demonstrated no significant variation across elevation and location in the fjord. However, two phyla, namely Mucoromycota and Zoopagomycota, exhibited a marked increase in abundance at lower elevations. It has been demonstrated that certain Mucoromycota fungi facilitate plant growth and benefit from plant-derived organic matter [

10], which is supported by the higher angiosperm coverage observed at the lower sites. The presence of dense vegetation has also been linked to a more diverse soil food web, resulting in increased populations of microarthropods, nematodes, and protozoa. These organisms, in turn, might serve as prey for numerous species of Zoopagomycota [

11].

A recent study showed that the diversity of saprotrophs in forest soils from Europe and Iceland declines with elevation [

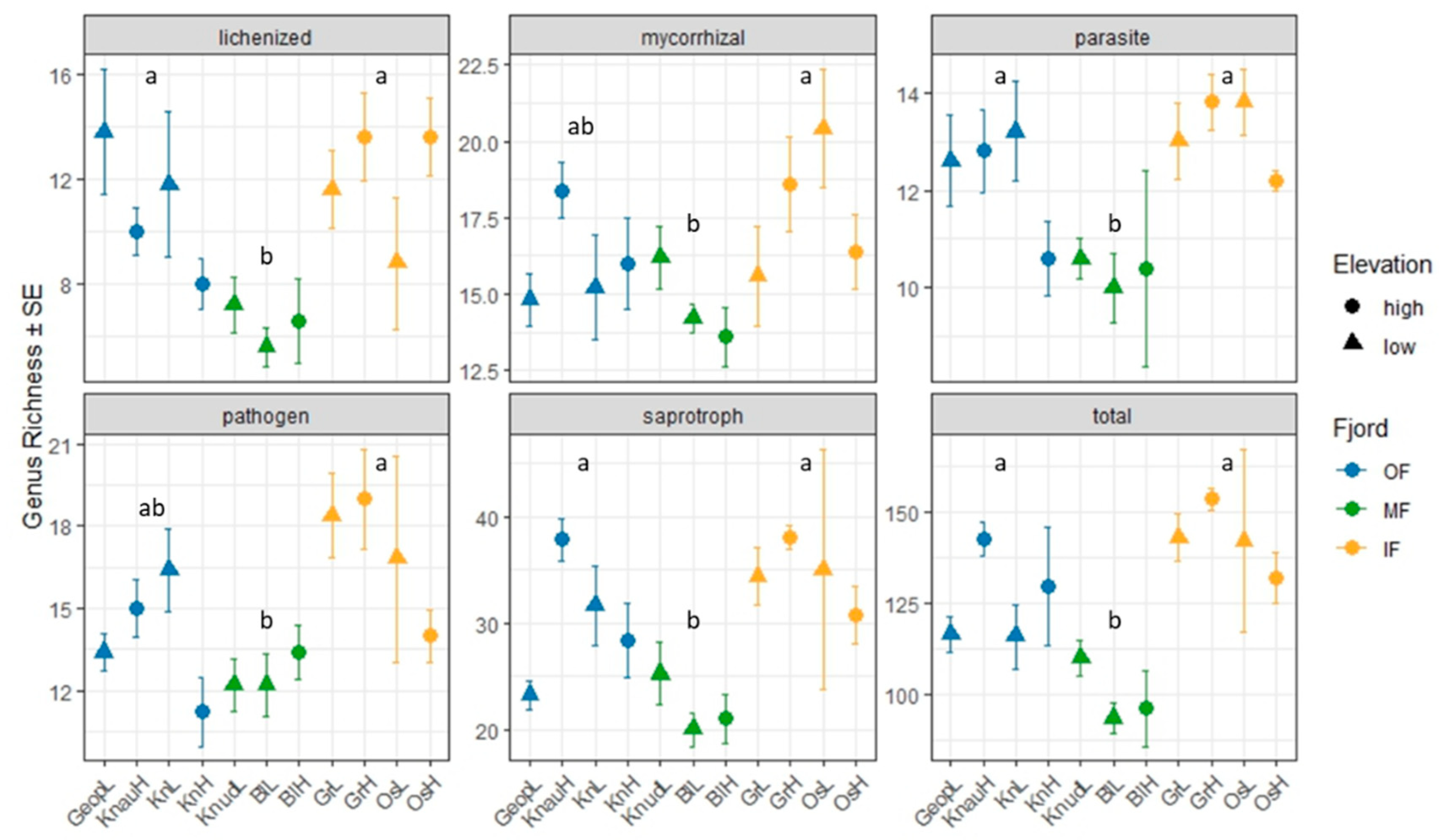

12]. In contrast, in the present study no significant differences in fungal genus richness or read abundance were observed for any fungal guild between low- and high-elevation sites (

Figure 1). However, the location within the fjord significantly affected the composition of the fungi, with the number of fungal genera and read abundance being lower in MF sites and higher in IF sites (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

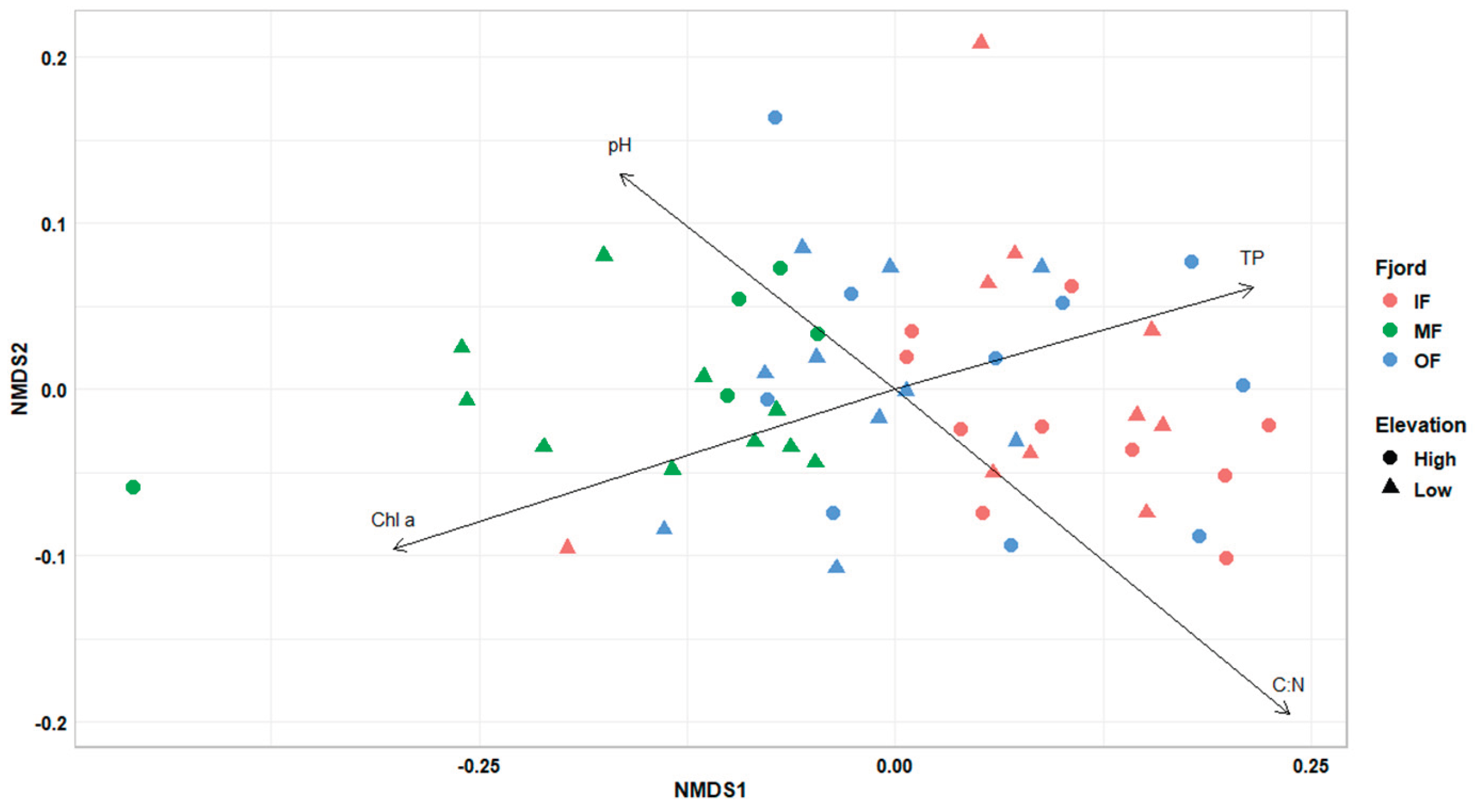

The NMDS plot based on fungal read counts, followed by a PERMANOVA test, showed that the location within the fjord significantly explained variation in community composition (R² = 13.9%, p = 0.001), whereas elevation had a non-significant effect (R² = 2.1%, p > 0.05;

Figure 2). Fungal community dissimilarities were explained by pH, C:N ratio and chlorophyll a, TP contents. Sites in MF had higher pH and chlorophyll a, but lower TP and C:N, which could relate to lower fungal abundance and richness observed there. C:N ratio appears to be a critical factor influencing fungal distribution and competitive success, potentially shaping community composition even across small-scale elevational gradients [

13]. Sites in OF and IF, with higher C:N ratios and TP content, might favour fungal taxa capable of efficiently degrading complex carbon compounds, given that the elevated P availability supports the metabolic and enzymatic processes required for their growth and function [

14].

Despite no significant differences between fungal phyla and guilds, 27 genera were identified as indicators of sites at high elevation, while 4 genera were designated as indicators of sites at low elevation (

Supplementary Table S1). For example, lichenized fungi (e.g.

Staurothele,

Acarospora,

Placopsis,

Calogaya,

Pannoparmelia) were significantly associated with higher-elevation sites, which was also consistent with vegetation analyses showing increased lichen coverage in these areas [

4]. Harsh environmental conditions at higher elevations limit vascular plant growth, reducing competition for space and nutrients and allowing lichens to proliferate [

15]. Increased lichen diversity at higher elevation could provide more hosts for endolichenic (

Sclerococcum) or lichenicolous (

Endococcus and

Cercidospora) fungi, which were also indicator taxa of high elevations biocrusts.

Functional annotation indicated that the core metabolic pathway, such as oxidative phosphorylation (map00190), was consistently observed in fungal communities across the sites (15-38% of annotated fungal contigs). However, fungi from high-elevation sites exhibited significant enrichment in DNA repair, stress signaling, cell structure, gene expression machinery, and specialized metabolism pathways, reflecting adaptations to additional stressors [

16,

17] associated with higher elevations, such as increased UV exposure, lower temperatures, and more extreme microclimatic variability compared to lower-elevation sites (

Table 1). As some pathways were exclusively detected in high-elevation communities and absent in low-elevation ones, these appeared as extreme fold-change values, which should be interpreted as presence/absence signals rather than precise quantitative differences.

Overall, these findings emphasize that Arctic fungal diversity and function are governed not solely by elevation but by a combination of local biotic and abiotic factors, highlighting their integral role in sustaining biocrust stability, nutrient cycling, and ecosystem resilience in polar environments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

This project was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) within the project PU867/1-1, Be1779/.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank members of AWIPEW station in Ny-Ålesund for technical and logistic support during sampling. Furthermore, we are grateful to Isabel Mas Martinez and Leonie Keilholz for the laboratory assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Weber, B.; Büdel, B.; Belnap, J. Biological Soil Crusts: An Organizing Principle in Drylands, Springer International Publishing, 2016.

- Robinson, C.H. Cold Adaptation in Arctic and Antarctic Fungi. New Phytologist 2001, 151, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timling, I.; Walker, D.A.; Nusbaum, C.; Lennon, N.J.; Taylor, D.L. Rich and Cold: Diversity, Distribution and Drivers of Fungal Communities in Patterned-Ground Ecosystems of the North American Arctic. Mol Ecol 2014, 23, 3258–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkareva, E.; Keilholz, L.; Kammann, S.; Linne von Berg, K.-H.; Karsten, U.; Becker, B. Arctic Biocrusts Highlight Genetic Variability in Photosynthesis as a Key Driver of Biodiversity. Preprint. [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Põlme, S.; Abarenkov, K.; Henrik Nilsson, R.; Lindahl, B.D.; Clemmensen, K.E.; Kauserud, H.; Nguyen, N.; Kjøller, R.; Bates, S.T.; Baldrian, P.; et al. FungalTraits: A User-Friendly Traits Database of Fungi and Fungus-like Stramenopiles. Fungal Divers 2020, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta-Cepas, J.; Forslund, K.; Coelho, L.P.; Szklarczyk, D.; Jensen, L.J.; Von Mering, C.; Bork, P. Fast Genome-Wide Functional Annotation through Orthology Assignment by EggNOG-Mapper. Mol Biol Evol 2017, 34, 2115–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oksanen, J. Multivariate Analysis of Ecological Communities in R:Vegan Tutorial. R documentation 2013, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malard, L.A.; Pearce, D.A. Minireview Microbial Diversity and Biogeography in Arctic Soils. Environ Microbiol Rep 2018, 10, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Bonito, G.; Hsu, C.-M.; Hameed, K.; Vilgalys, R.; Liao, H.-L. Mortierella Elongata Increases Plant Biomass among Non-Leguminous Crop Species. Agronomy 2020, 5, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsaro, D.; Köhsler, M.; Wylezich, C.; Venditti, D.; Walochnik, J.; Michel, R. New Insights from Molecular Phylogenetics of Amoebophagous Fungi (Zoopagomycota, Zoopagales). Parasitol Res 2018, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbi, F.; Martinović, T.; Odriozola, I.; Machac, A.; Moravcová, A.; Algora, C.; et al. Disentangling Drivers behind Fungal Diversity Gradients along Altitude and Latitude. New Phytologist 2025, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Y.; Yang, T.; Zhang, K.; Shen, C.; Chu, H. Fungal Communities along a Small-Scale Elevational Gradient in an Alpine Tundra Are Determined by Soil Carbon Nitrogen Ratios. Front Microbiol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pánek, M.; Vlková, T.; Michalová, T.; Borovička, J.; Tedersoo, L.; Adamczyk, B.; Baldrian, P.; Lopéz-Mondéjar, R. Variation of Carbon, Nitrogen and Phosphorus Content in Fungi Reflects Their Ecology and Phylogeny. Front Microbiol 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asplund, J.; Van Zuijlen, K.; Roos, R.E.; Birkemoe, T.; Klanderud, K.; Lang, S.I.; Wardle, D.A. Divergent Responses of Functional Diversity to an Elevational Gradient for Vascular Plants, Bryophytes and Lichens. J Veg Sci 2022, 33, 13105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, B.B.; Mylonakis, E. Our Paths Might Cross: The Role of the Fungal Cell Wall Integrity Pathway in Stress Response and Cross Talk with Other Stress Response Pathways. Eukaryot Cell 2009, 8, 1616–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.J.P.; Cowen, L.E.; di Pietro, A.; Quinn, J. Stress Adaptation. Microbiol Spectr 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).