Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Problem Statement and Research Gap

3. Literature Review

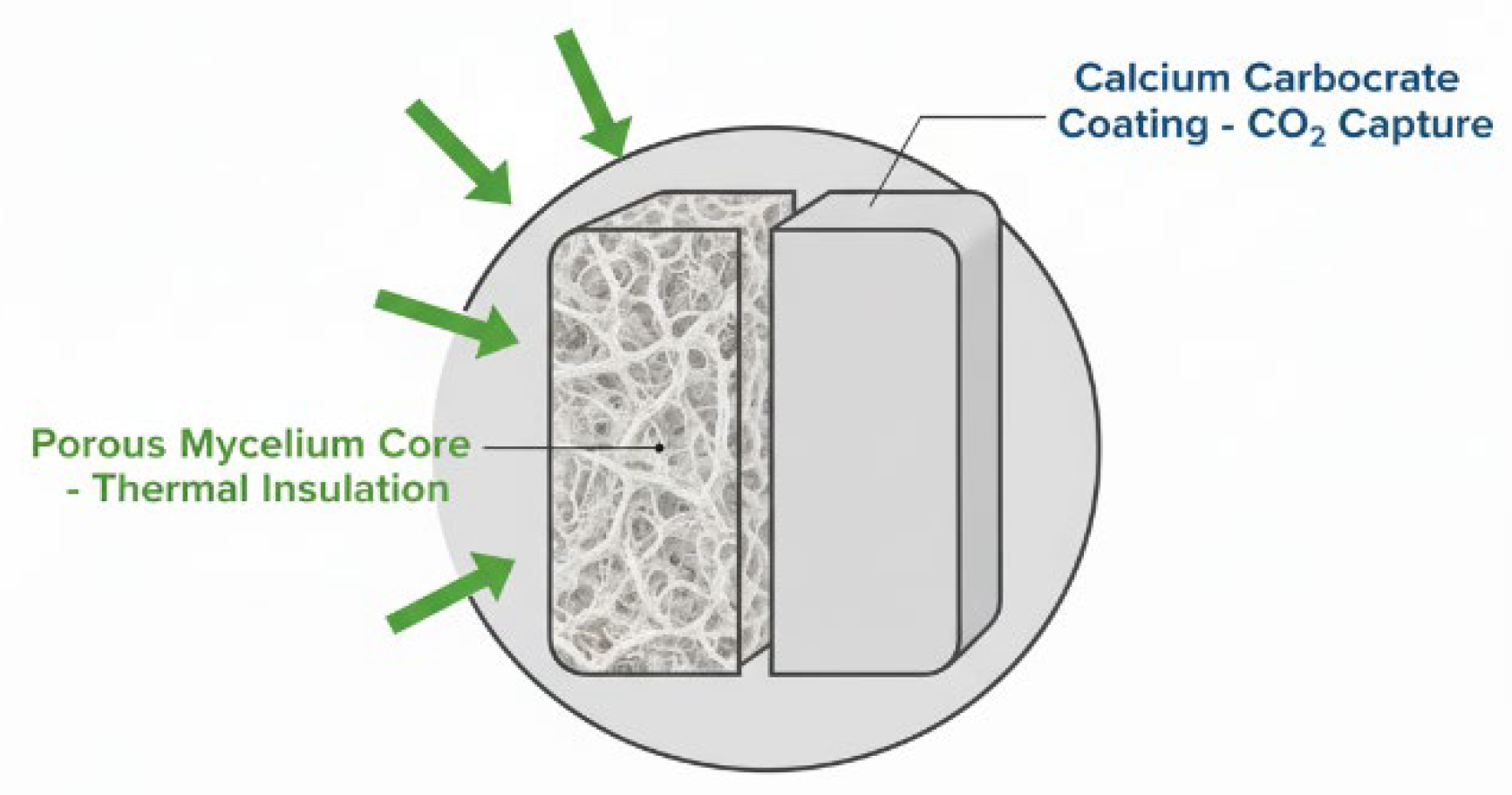

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

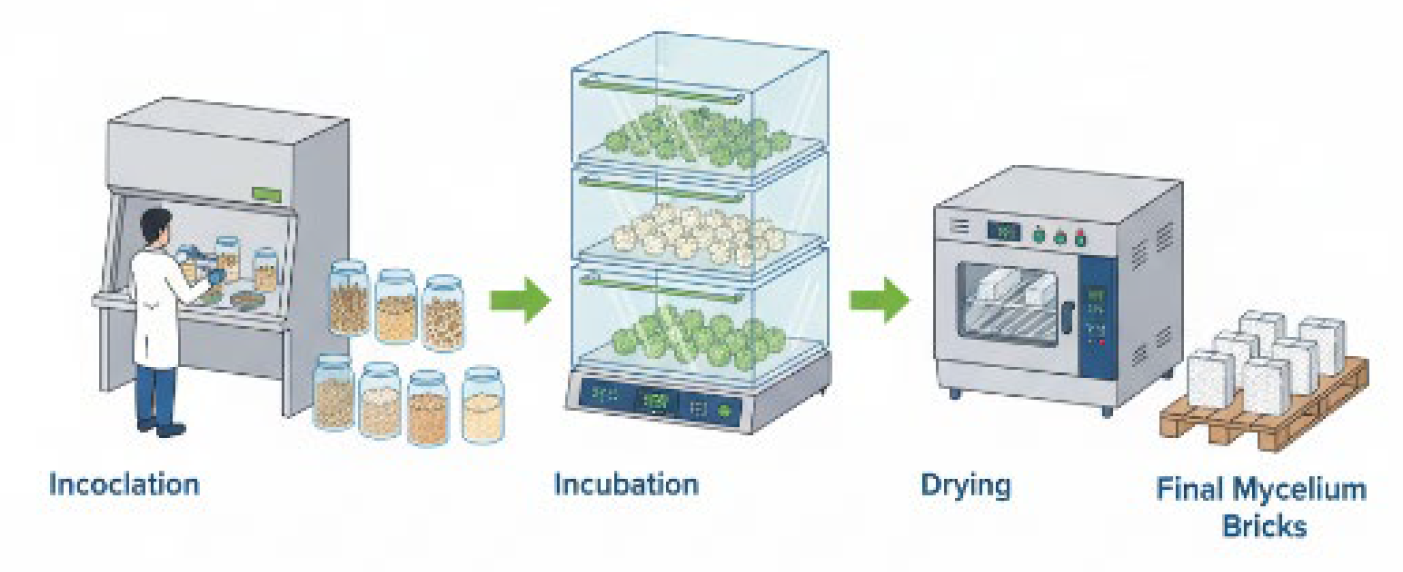

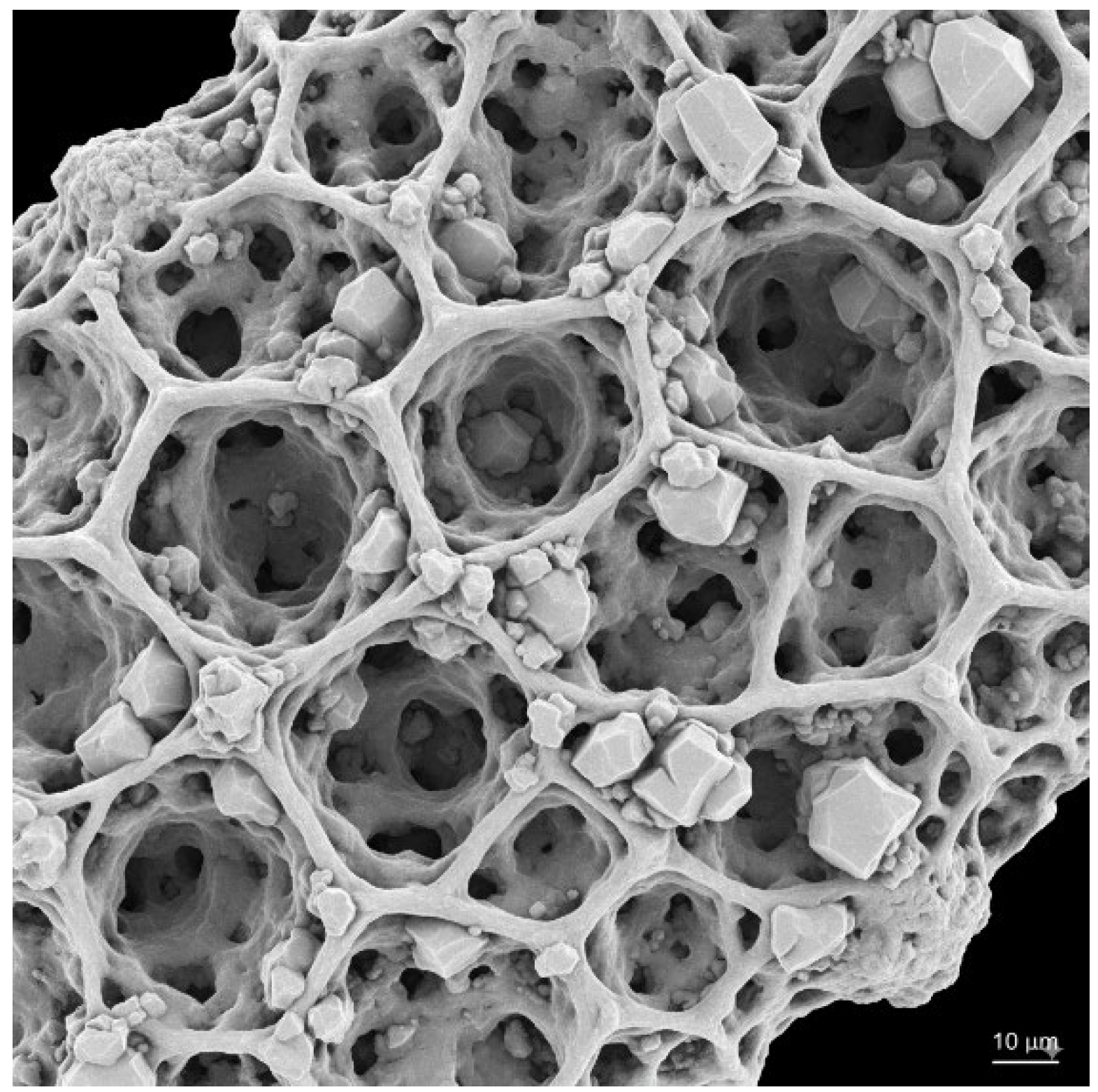

4.2. Sample Fabrication

4.3. Experimental Design

| Group | Substrate | CaCO3 proportion |

Replicates |

Measurements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | Rice husk |

0% | 5 | Compressive strength, Density, Thermal conductivity, Water absorption |

| G2 | Rice husk |

10% | 5 | Same as above |

| G3 | Rice husk |

20% | 5 | Same as above |

| G4 | Rice husk |

30% | 5 | Same as above |

| G5 | Sawdust |

0% | 5 | Same as above |

| G6 | Sawdust |

10% | 5 | Same as above |

| G7 | Sawdust |

20% | 5 | Same as above |

| G8 | Sawdust |

30% | 5 | Same as above |

4.4. Property Evaluation

5. Results

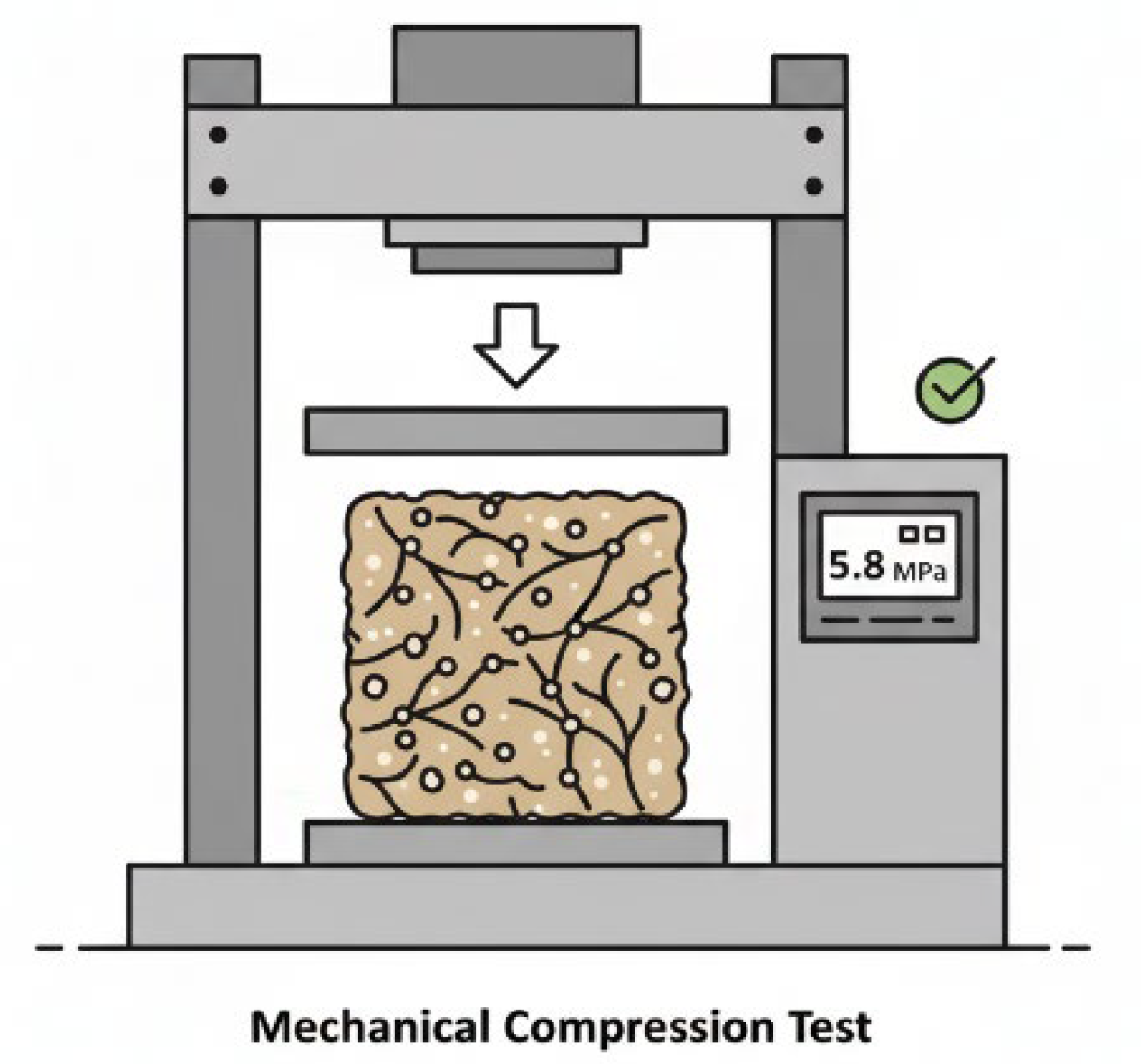

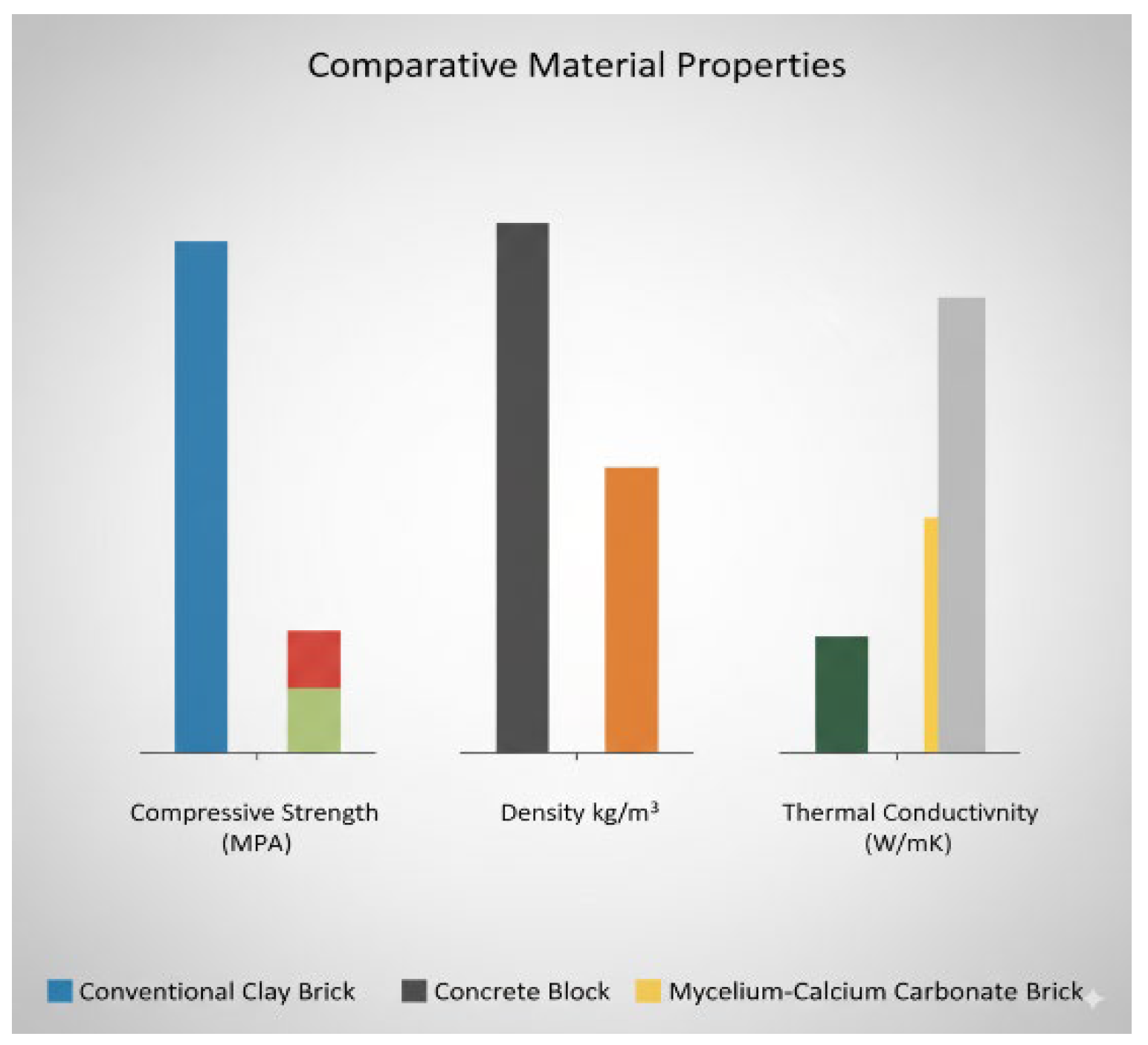

5.1. Compressive Strength

5.2. Density

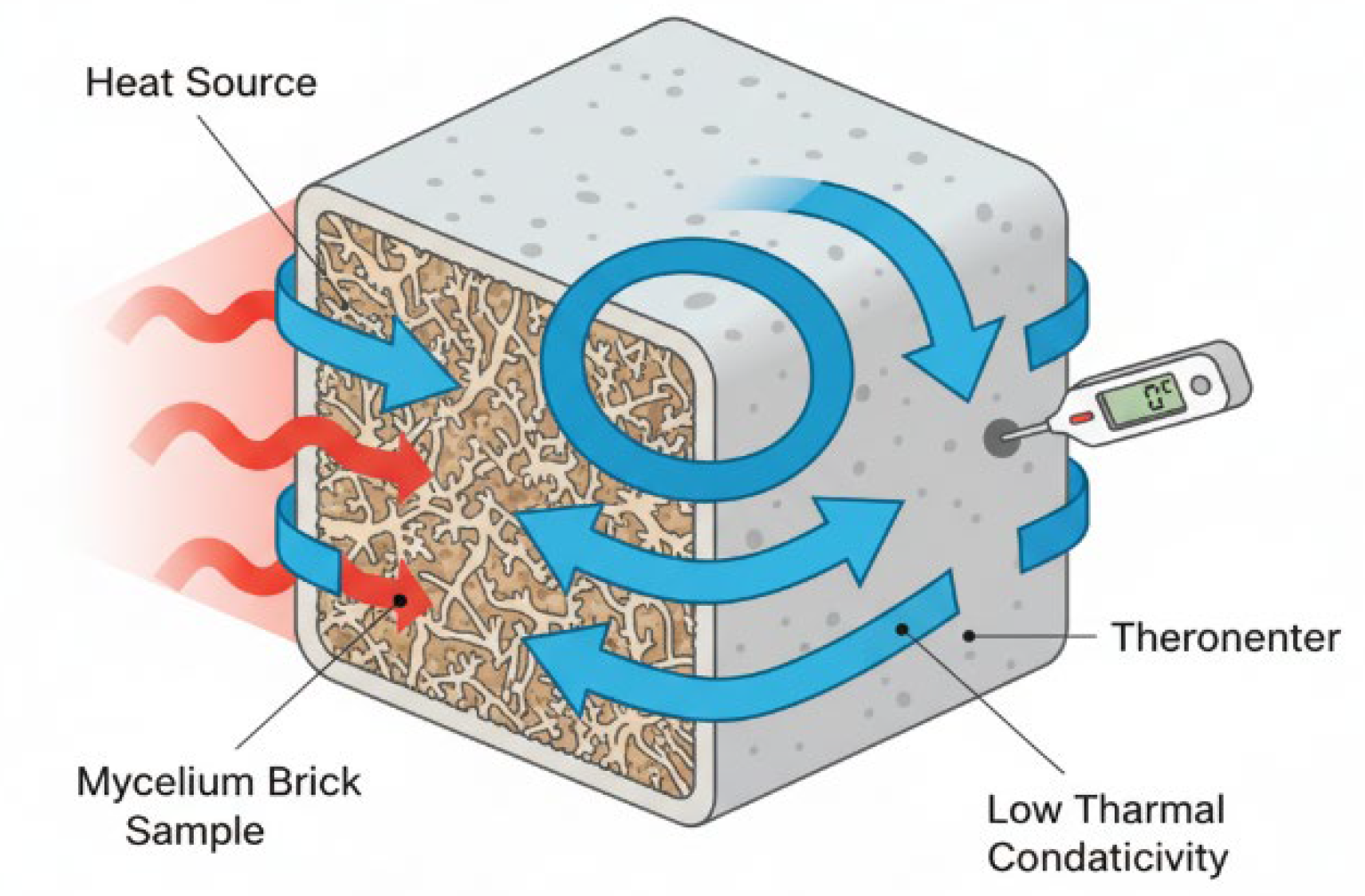

5.3. Thermal Conductivity

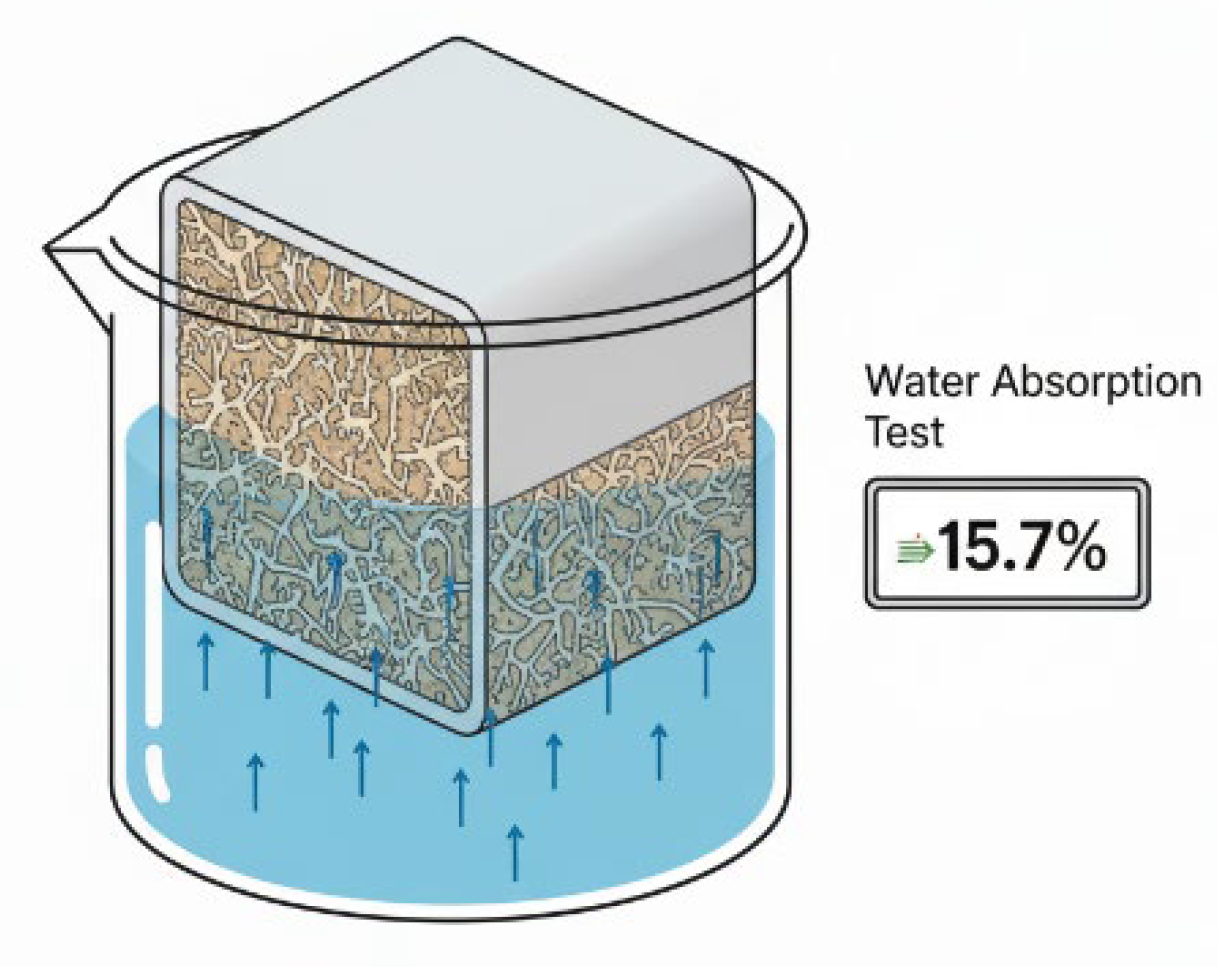

5.4. Water Absorption

6. Discussion

6.1. Mechanical Properties

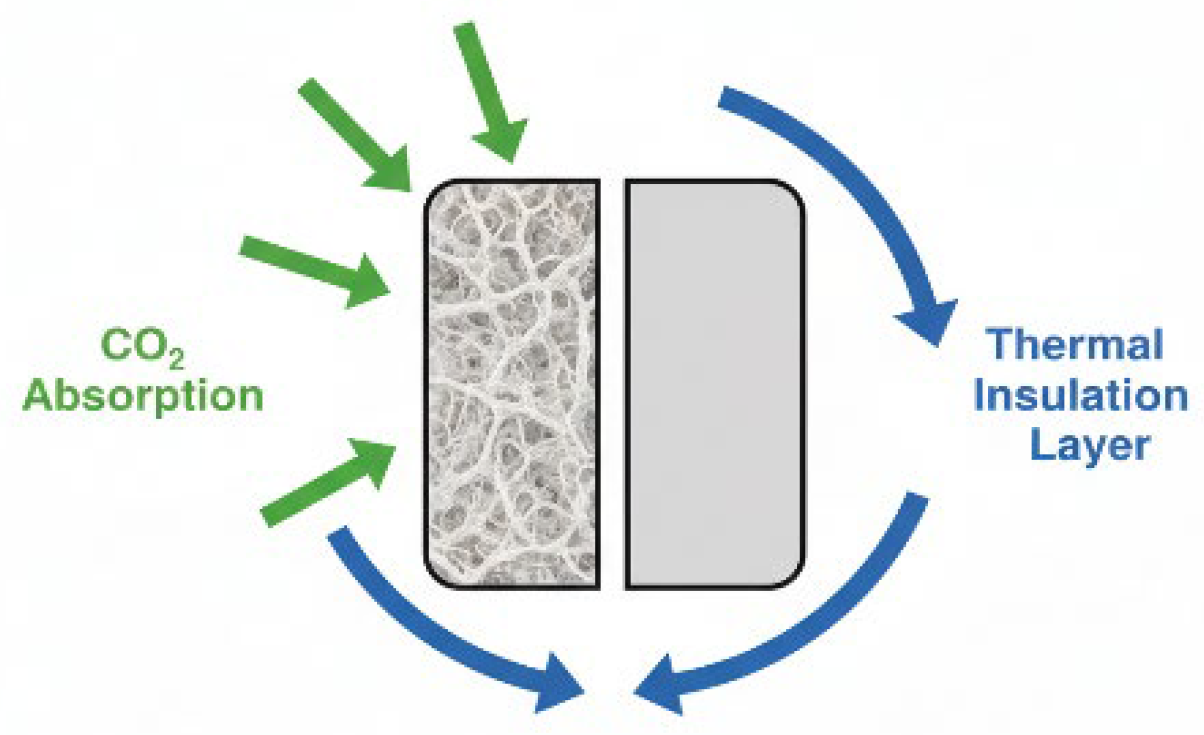

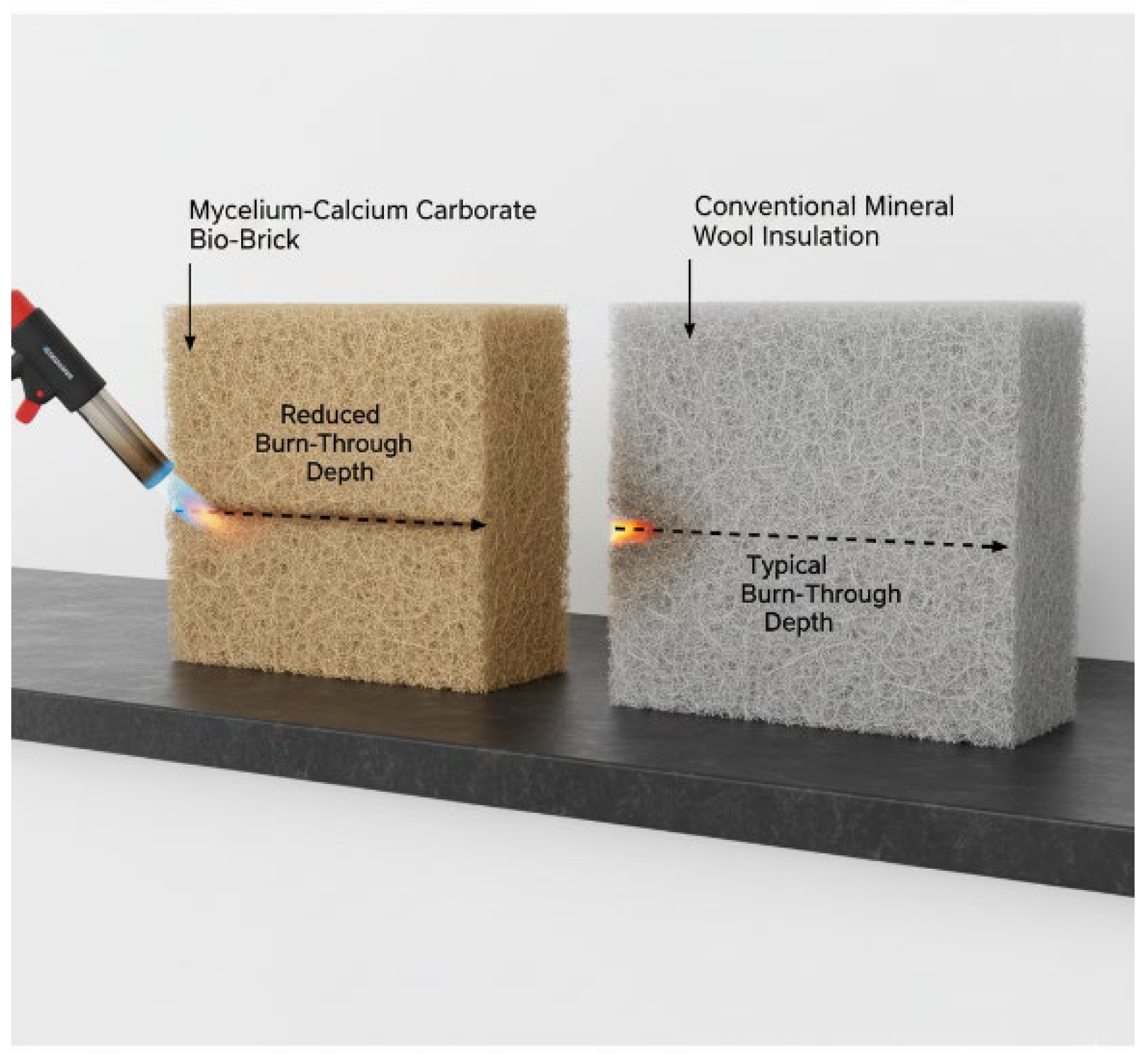

6.2. Thermal Insulation

6.3. Water Absorption and Durability

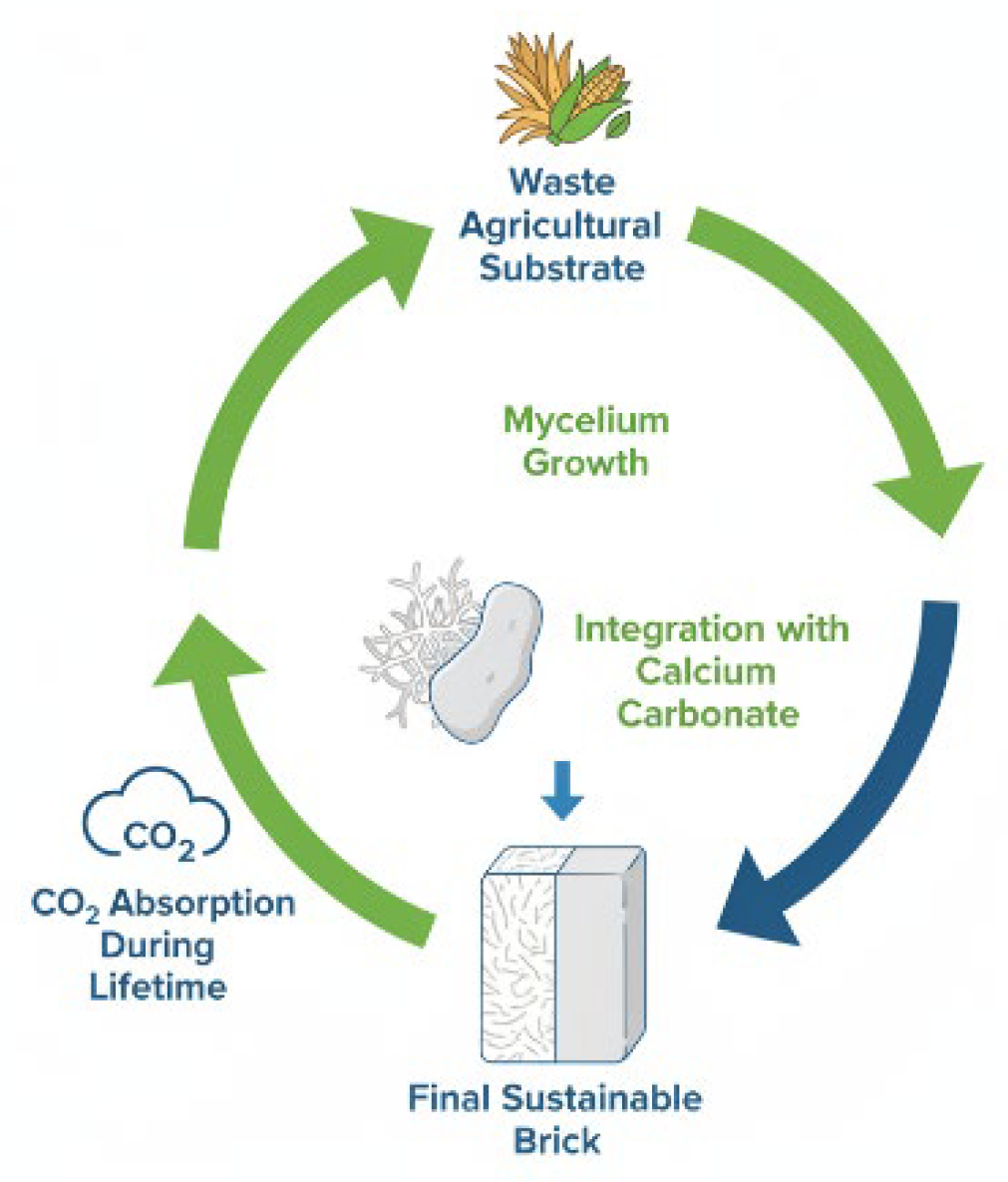

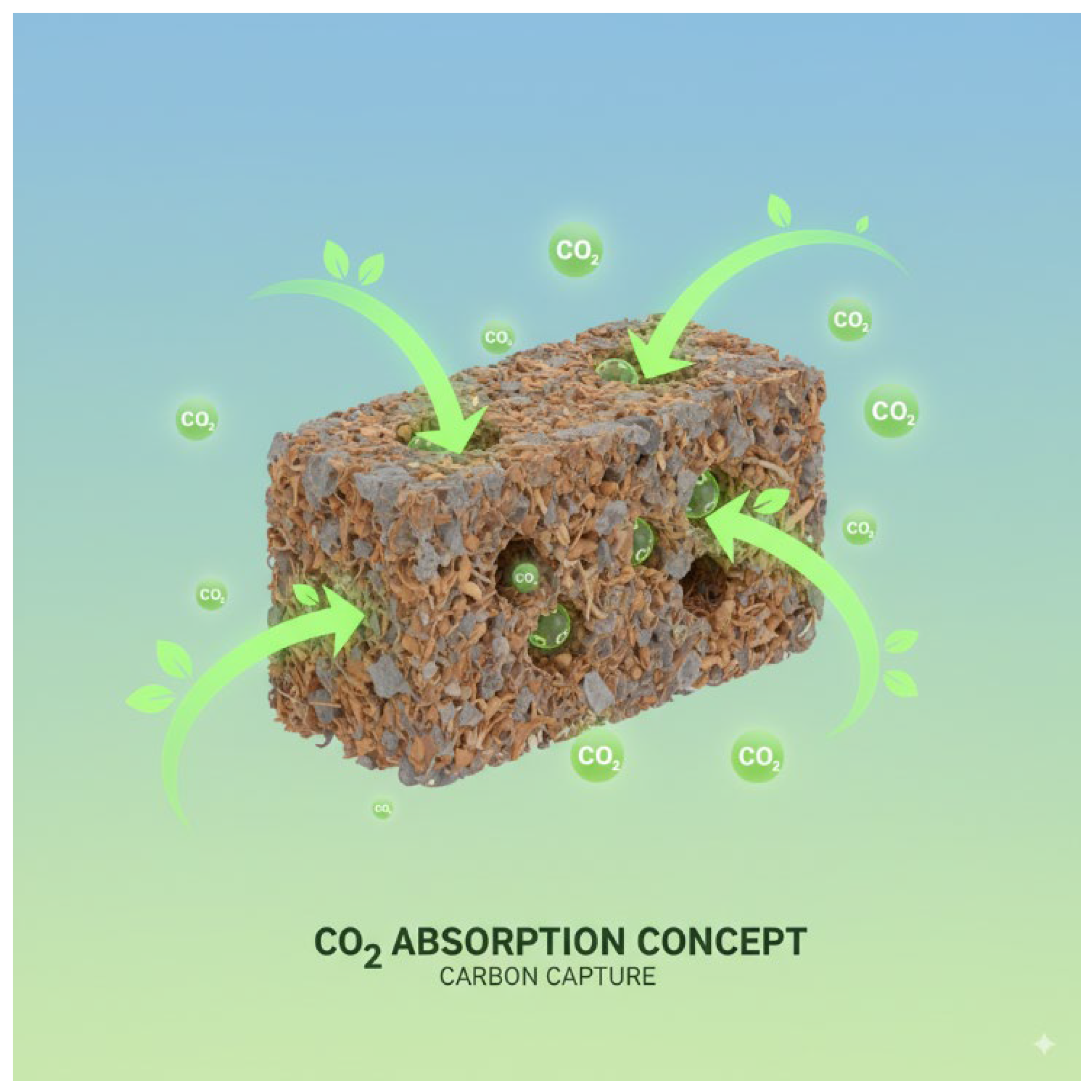

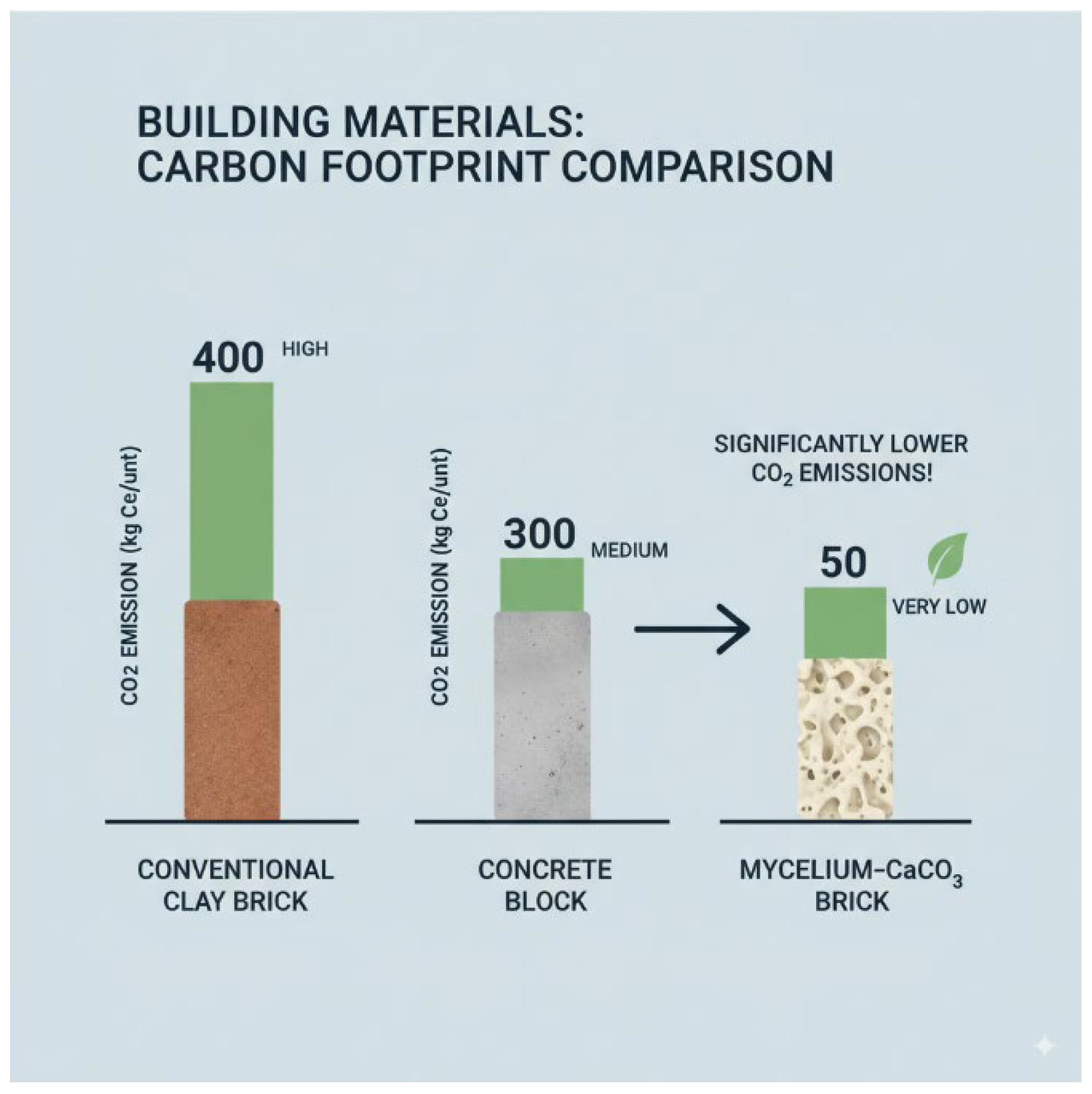

6.4. Environmental Implications

6.5. Study Limitations

7. Conclusion and Recommendations

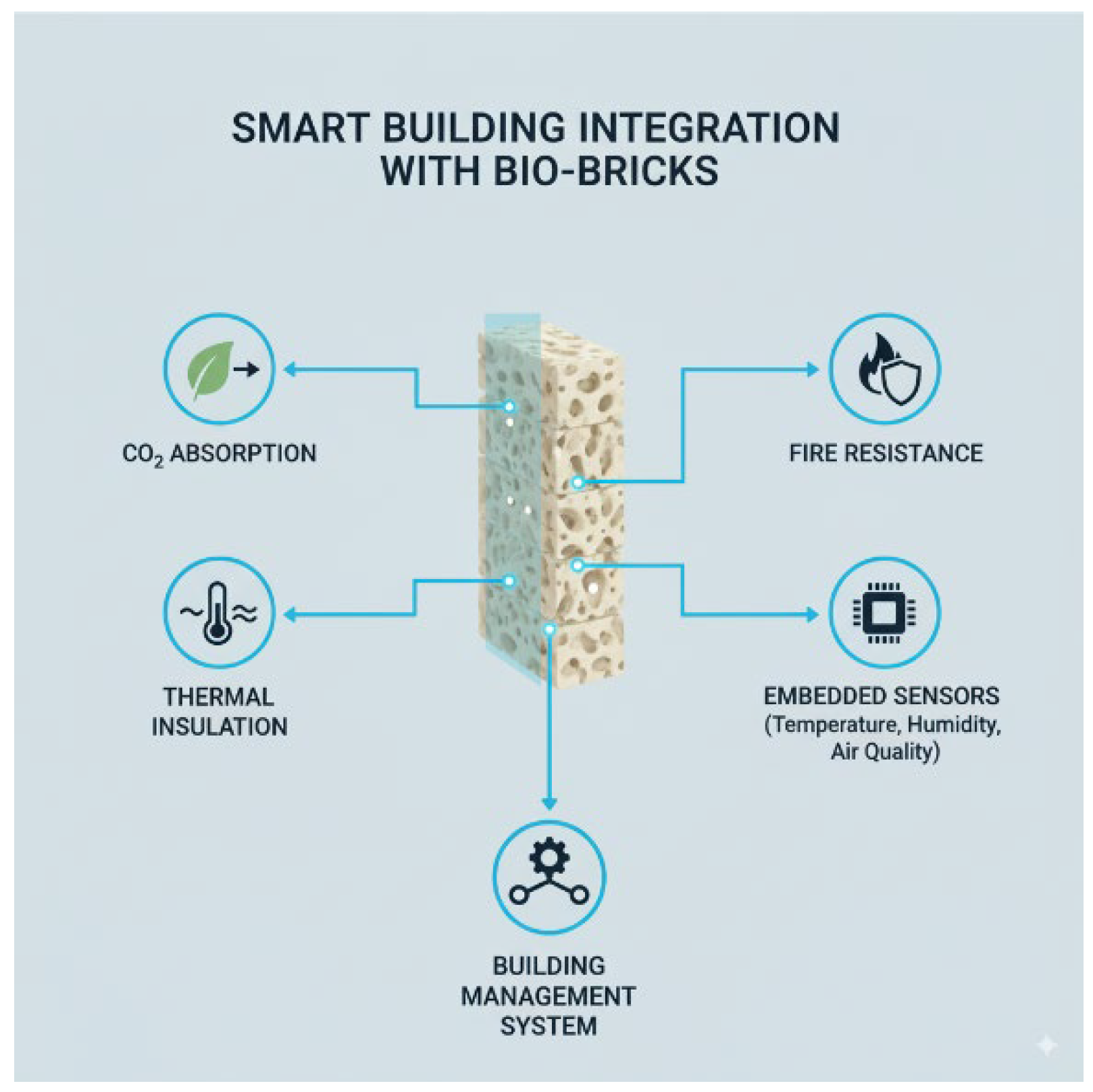

7.1. Practical Recommendations

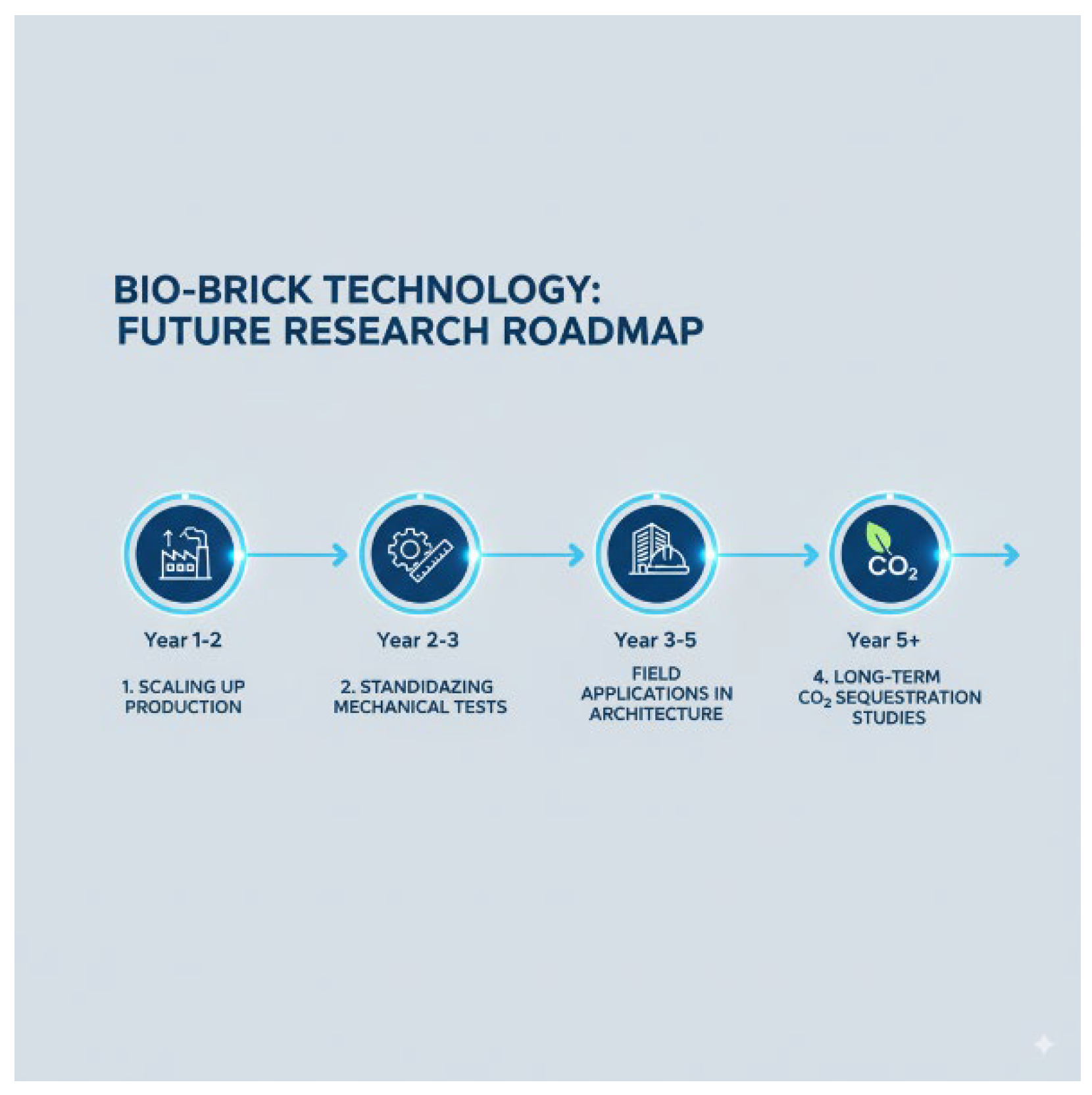

7.2. Future Research Directions

References

- Volk, R.; Schröter, M.; Saeidi, N.; Steffl, S.; Javadian, A.; Hebel, D.E.; Schultmann, F. Life Cycle Assessment of Mycelium-Based Composite Materials. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 205, 107579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Mautner, A.; Luenco, S.; Bismarck, A.; John, S. Engineered Mycelium Composite Construction Materials from Fungal Biorefineries: A Critical Review. Mater. Des. 2020, 187, 108397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, Y.; El Zakhem, H.; Hamami, A.E.A.; El Bachawati, M.; Belarbi, R. Comprehensive Review of Innovative Materials for Sustainable Buildings’ Energy Performance. Energies 2023, 16, 7440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfaleh, I.; Abbassi, F.; Habibi, M.; Ahmad, F.; Guedri, M.; Nasri, M.; Garnier, C. A Comprehensive Review of Natural Fibers and Their Composites: An Eco-Friendly Alternative to Conventional Materials. Results Eng. 2023, 19, 101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaneme, K.K.; Anaele, J.U.; Oke, T.M.; Kareem, S.A.; Adediran, M.; Ajibuwa, O.A.; Anabaranze, Y.O. Mycelium Based Composites: A Review of Their Bio-Fabrication Procedures, Material Properties and Potential for Green Building and Construction Applications. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 83, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomoglou, A.K.; Voutetaki, M.E.; Fantidis, J.G.; Chalioris, C.E. Novel Natural Bee Brick with a Low Energy Footprint for “Green” Masonry Walls: Mechanical Properties. Eng. Proc. 2024, 60, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Filipova, I.; Irbe, I.; Spade, M.; Skute, M.; Daboliņa, I.; Baltina, I.; Vecbiskena, L. Mechanical and Air Permeability Performance of Novel Biobased Materials from Fungal Hyphae and Cellulose Fibers. Materials 2021, 14, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayfutdinova, A.R.; Cherednichenko, K.A.; Rakitina, M.A.; Dubinich, V.N.; Bardina, K.A.; Rubtsova, M.I.; Petrova, D.A.; Vinokurov, V.A.; Voronin, D.V. Natural Fibrous Materials Based on Fungal Mycelium Hyphae as Porous Supports for Shape-Stable Phase-Change Composites. Polymers 2023, 15, 4504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonnala, S.N.; Gogoi, D.; Devi, S.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, C. A Comprehensive Study of Building Materials and Bricks for Residential Construction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 425, 135931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Z.; Han, X.; Liu, J.; Ma, Q.; Yan, H.; Yuan, C.; Yang, L.; Han, H.; Weng, F.; Li, Y. Nano-Fe3O4/Bamboo Bundles/Phenolic Resin Oriented Recombination Ternary Composite with Enhanced Multiple Functions. Compos. B Eng. 2021, 226, 109335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lou, Z.; Wang, Q.; Xu, L.; Li, Y. Introducing Rich Heterojunction Surfaces to Enhance the High-Frequency Electromagnetic Attenuation Response of Flexible Fiber-Based Wearable Absorbers. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2024, 6, 739–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almpani-Lekka, D.; Pfeiffer, S.; Schmidts, C.; Seo, S.-i. A Review on Architecture with Fungal Biomaterials: The Desired and the Feasible. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2021, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsacker, E.; Vandelook, S.; Brancart, J.; Peeters, E.; De Laet, L. Mechanical, Physical and Chemical Characterisation of Mycelium-Based Composites with Different Types of Lignocellulosic Substrates. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Huynh, T.; Dekiwadia, C.; Daver, F.; John, S. Mycelium Composites: A Review of Engineering Characteristics and Growth Kinetics. J. Bionanosc. 2017, 11, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisel, F.; Hebel, D.E. Pioneering Construction Materials through Prototypological Research. Biomimetics 2019, 4, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbabali, H.; Lubwama, M.; Yiga, V.A.; Were, E.; Kasedde, H. Development of Rice Husk and Sawdust Mycelium-Based Bio-Composites: Optimization of Mechanical, Physical and Thermal Properties. J. Inst. Eng. (India) Ser. D 2024, 105, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigobello, A.; Colmo, C.; Ayres, P. Effect of Composition Strategies on Mycelium-Based Composites Flexural Behaviour. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, Y.H.; Yusuf, Y. Mycelium Fibers as New Resource for Environmental Sustainability. Procedia Eng. 2013, 53, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Sumbria, R. Mycelium Bricks and Composites for Sustainable Construction Industry: A State-of-the-Art Review. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2022, 7, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsacker, E.; Vandelook, S.; Damsin, B.; Van Wylick, A.; Peeters, E.; De Laet, L. Mechanical Characteristics of Bacterial Cellulose-Reinforced Mycelium Composite Materials. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2021, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamu, M.; Alanazi, F.; Ibrahim, Y.E.; Alanazi, H.; Khed, V.C. A Comprehensive Review on Sustainable Natural Fiber in Cementitious Composites: The Date Palm Fiber Case. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, D.L.; Júnior, L.U.D.T.; Marvila, M.T.; Pereira, E.C.; Souza, D.; de Azevedo, A.R.G. A Review of the Use of Natural Fibers in Cement Composites: Concepts, Applications and Brazilian History. Polymers 2022, 14, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.J.; Thomas, S. Biofibres and Biocomposites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007, 71, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapuan, S.M.; Harussani, M.M.; Syafri, E. A Short Review of Recent Engineering Applications of Natural Fibres. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1097, 012033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Sumbria, R. Mycelium Bricks and Composites for Sustainable Construction Industry: A State-of-the-Art Review. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2022, 7, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naoum, M.C.; Sapidis, G.M.; Papadopoulos, N.A.; Voutetaki, M.E. An Electromechanical Impedance-Based Application of Realtime Monitoring for the Load-Induced Flexural Stress and Damage in Fiber-Reinforced Concrete. Fibers 2023, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, A.M. State of the Art in Thermal Insulation Materials and Aims for Future Developments. Energy Build. 2005, 37, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajączkowska, P.; Kowalczyk, K.; Chylińska, M.; Wrzalik, R.; Kaźmierczak, J.; Michalik, M.; Kozik, V.; Szatkowski, T. Mycelium-Based Composites—Processing and Mechanical Properties. Materials 2020, 13, 4551. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalcik, A.; Kuciel, S.; Fortelný, I.; Koutný, M.; Vrbova, R.; Ďurčová, D. Influence of Surface Treatments on Properties of Biocomposites with Natural Fibres. Compos. B Eng. 2020, 182, 107626. [Google Scholar]

- Asim, M.; Jawaid, M.; Paridah, M.T.; Saba, N.; Nasir, M.; Shahroze, R.M. A Review on Pineapple Leaves Fibre and Its Composites. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2015, 2015, 950567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamoorthy, S.K.; Skrifvars, M.; Persson, A. A Review of Natural Fibers Used in Biocomposites: Plant, Animal and Regenerated Cellulose Fibers. Polym. Rev. 2015, 55, 107–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Song, B.; Liu, C.; Xu, F.; Wang, X. Research Progress on the Application of Calcium Carbonate in Building Materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 283, 122757. [Google Scholar]

- Montes, C.; Rodríguez, E.; Rosales, J.; Cabrera, M.; López-Alonso, M.; López-Alonso, M.; Ortega, J.M. Mineral Carbonation for CO2 Sequestration: A Review of Recent Developments. J. CO2 Util. 2021, 43, 101374. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; He, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, H. Accelerated Carbonation of Cement-Based Materials: Mechanisms, Testing Methods and Applications. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 114, 103713. [Google Scholar]

- Khushnood, R.A.; Rizwan, S.A.; Memon, S.A.; Tulliani, J.-M.; Ferro, G.A. Carbonated Natural Fibre-Reinforced Cement Composites for Improved Mechanical and Durability Properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 121, 643–651. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Li, D.; Zhou, C.; Wang, H.; Yu, X. Mechanical and Microstructural Properties of CaCO3-Reinforced Biocomposites. Polym. Compos. 2019, 40, 162–171. [Google Scholar]

- El-Shekeil, Y.A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Jawaid, M.; Al-Shuja’a, O.M.; Ahmad, F. Influence of Calcium Carbonate on the Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Kenaf/Polypropylene Composites. Mater. Des. 2014, 57, 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Asim, M.; Saba, N.; Jawaid, M.; Nasir, M.; Ibrahim, F.; Alothman, O.Y.; Almutairi, Z. A Review on Properties and Applications of Natural Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites. Cellulose 2018, 25, 2025–2111. [Google Scholar]

- Stamets, P. Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World; Ten Speed Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stamets, P. Growing Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms, 3rd ed.; Ten Speed Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.T.; Hayes, W.A. The Biology and Cultivation of Edible Mushrooms; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Philippoussis, A.; Diamantopoulou, P.; Israilides, C. Productivity of Agricultural Residues Used for the Cultivation of the Medicinal Fungus Lentinula edodes. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2007, 59, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D695-15. Standard Test Method for Compressive Properties of Rigid Plastics; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM C518-17. Standard Test Method for Steady-State Thermal Transmission Properties by Means of the Heat Flow Meter Apparatus; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM C272/C272M-18. Standard Test Method for Water Absorption of Core Materials for Sandwich Constructions; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, S.; Oh, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, J. Mechanical Behavior of Bio-Based Composites with Fungal Mycelium Reinforcement. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 192, 108107. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, C.; Xu, J.; Chen, S. Influence of CaCO3 Content on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Polymer Composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47528. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Guo, L. Enhanced Durability of Mycelium-Based Biocomposites via Surface Treatments. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 281, 122602. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Yan, R.; Chen, H.; Lee, D.H.; Zheng, C. Characteristics of Hemicellulose, Cellulose and Lignin Pyrolysis. Fuel 2007, 86, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harish, S.; Michael, D.P.; Bensely, A.; Mohan Lal, D.; Rajadurai, A. Mechanical Property Evaluation of Natural Fiber Coir Composite. Mater. Charact. 2009, 60, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M.; Drzal, L.T. Sustainable Bio-Composites from Renewable Resources: Opportunities and Challenges in the Green Materials World. J. Polym. Environ. 2002, 10, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruk, O.; Bledzki, A.K.; Fink, H.P.; Sain, M. Biocomposites Reinforced with Natural Fibers: 2000–2010. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 1552–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, M.F. Materials Selection in Mechanical Design, 5th ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, L.J.; Ashby, M.F. Cellular Solids: Structure and Properties, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.; Huynh, T.; John, S.; Jeronimidis, G. Mycelium Composites: A Review of Engineering Characteristics and Growth Kinetics. J. Bionanoscience 2018, 12, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appels, F.V.W.; Camere, S.; Montalti, M.; Karana, E.; Jansen, K.M.B.; Dijksterhuis, J.; Krijgsheld, P.; Wösten, H.A.B. Fabrication Factors Influencing Mechanical, Moisture- and Water-Related Properties of Mycelium-Based Composites. Mater. Des. 2019, 161, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attias, N.; Danai, O.; Ezov, N.; Tarazi, E.; Bacher, A.; Pereman, I.; Grobman, Y.J. Mycelium Bio-Composites in Industrial Design and Architecture: Comparative Review and Experimental Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 119037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A.R.; Bajwa, S.G.; Holt, G.A.; McIntyre, G.; Bajwa, D.S. Evaluation of Physico-Mechanical Properties of Mycelium-Reinforced Green Biocomposites Made from Cellulosic Fibers. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2016, 32, 931–938. [Google Scholar]

- Haneef, M.; Ceseracciu, L.; Canale, C.; Bayer, I.S.; Heredia-Guerrero, J.A.; Athanassiou, A. Advanced Materials from Fungal Mycelium: Fabrication and Tuning of Physical Properties. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsacker, E.; Vandelook, S.; Brancart, J.; Peeters, E.; De Laet, L. Mechanical, Physical and Chemical Characterisation of Mycelium-Based Composites with Different Types of Lignocellulosic Substrates. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelletier, M.G.; Holt, G.A.; Wanjura, J.D.; Bayer, E.; McIntyre, G. An Evaluation Study of Mycelium Based Acoustic Absorbers. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 51, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panyakaew, S.; Fotios, S. New Thermal Insulation Boards Made from Coconut Husk and Bagasse. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 1732–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madurwar, M.V.; Ralegaonkar, R.V.; Mandavgane, S.A. Application of Agro-Waste for Sustainable Construction Materials: A Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 38, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Goel, R.; Dubey, A.; Shivhare, N.; Bhalavi, T. A Review of Natural Fibres and Biocomposites: Chemical and Mechanical Properties. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2017, 36, 881–907. [Google Scholar]

- John, M.J.; Thomas, S. Biofibres and Biocomposites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008, 71, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, K.L.; Efendy, M.G.A.; Le, T.M. A Review of Recent Developments in Natural Fibre Composites and Their Mechanical Performance. Compos. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 83, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M.; Drzal, L.T. Natural Fibres, Biopolymers, and Biocomposites; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Satyanarayana, K.G.; Guimarães, J.L.; Wypych, F. Studies on Lignocellulosic Fibers of Brazil. Part I: Source, Production, Morphology, Properties and Applications. Compos. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2007, 38, 1694–1709. [Google Scholar]

- Faruk, O.; Bledzki, A.K.; Fink, H.P.; Sain, M. Progress Report on Natural Fiber Reinforced Composites. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2014, 299, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, A.S.; Thakur, V.K. Mechanical Properties of Natural Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2008, 31, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tabil, L.G.; Panigrahi, S. Chemical Treatments of Natural Fiber for Use in Natural Fiber-Reinforced Composites: A Review. J. Polym. Environ. 2007, 15, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bledzki, A.K.; Gassan, J. Composites Reinforced with Cellulose-Based Fibres. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1999, 24, 221–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; McDonald, A.G. A Review on Utilization of Wood–Plastic Composites in Construction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 118, 644–658. [Google Scholar]

- Kozłowski, R.M.; Władyka-Przybylak, M. Flammability and Fire Resistance of Composites Reinforced with Natural Fibres. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2008, 19, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, S.; Cerritelli, G.F.; Forni, D.; Roversi, R.; Tugnoli, A.; Cozzani, V. Life Cycle Assessment of Building Insulation Materials: Environmental and Economic Performance. Energies 2021, 14, 1907. [Google Scholar]

- van der Lugt, P.; Vogtländer, J.G.; Brezet, J.C. Bamboo, a Sustainable Solution for Western Europe Design Cases, LCAs and Land-Use. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 1260–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Pittau, F.; Krause, F.; Lumia, G.; Habert, G. Fast-Growing Bio-Based Materials as an Opportunity for CO2 Sequestration in Buildings. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 33, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza, L.F.; Castell, A.; Medrano, M.; Leppers, R.; Zubillaga, O. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Life Cycle Energy Analysis (LCEA) of Buildings and the Building Sector: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 29, 394–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study (Ref.) | Material / Reinforcement | Density (kg/m3) | compressive Strength (MPa) | Water Absorption (%) |

Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) |

Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [18,19,20] | Pure Mycelium composites (agricultural waste substrates) | 40–200 | 0.2–0.6 | 150–250 | 0.05–0.07 | Excellent insulation, poor strength, high water uptake |

| [23,24,25] | Mycelium + Natural fibers (hemp, flax, jute) |

100–250 | 1.0–2.5 |

60–120 | 0.06–0.09 | Increased compressive strength, reduced water absorption |

| [26,27,28] | Mycelium + Inorganic fillers (sand, clay, nanoclay) |

200–350 | 1.5–3.0 | 50–100 | 0.07–0.11 | Improved dimensional stability and durability |

| [29,30,31] | Mycelium + Surface treatments / processing modifications |

150–300 | 1.2–2.0 |

70–110 | 0.06–0.10 |

Enhanced performance via process optimization |

| [32,33,34] | Calcium Carbonate (CaCO3) composites in construction | 500–1500 | 3.0–10.0 | 30–80 | 0.2–0.4 | Widely used as filler, stabilizer; improves strength and stability |

| [35,36,37] | Bio-composites reinforced with CaCO3 | 400–1200 | 2.5–8.0 | 20–60 |

0.15–0.35 | Enhanced compressive strength, dimensional stability, and moisture resistance |

| [38] |

Gap in literature: Mycelium + CaCO3 integration |

– | – | – | – |

Very few studies; potential for carbon-negative multifunctional bio-bricks |

| Group | Substrate | CaCO3 (%) | Compressive Strength (MPa) |

Density (kg/m3) | Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) |

Water Absorption (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | Rice husk | 0 |

0.45 |

185 |

0.065 |

120 |

| G2 | Rice husk | 10 | 0.62 |

185 |

0.072 | 98 |

| G3 | Rice husk | 20 | 0.78 | 235 |

0.080 |

85 |

| G4 | Rice husk | 30 | 0.95 |

260 |

0.090 | 70 |

| G5 | Sawdust | 0 | 0.40 |

190 |

0.068 | 115 |

| G6 | Sawdust | 10 | 0.55 |

215 |

0.074 |

95 |

| G7 | Sawdust | 20 | 0.72 |

240 |

0.082 |

82 |

| G8 | Sawdust | 30 | 0.88 |

265 | 0.093 |

68 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).