1. Introduction

The rapid growth of global infrastructure poses significant challenges, particularly in terms of sustainability and environmental impact [

1,

2]. Historically, raw cement, produced by grinding and burning gypsum or limestone, was mixed with sand and water to create mortar, which was used to bond stones. Over time, concrete has evolved into the most widely utilized material in modern construction, valued for its durability and strength. Its composition typically includes cement, coarse aggregates, fine aggregates, and water [

3]. Concrete production has increased substantially, doubling since the 1990s to surpass 330 million cubic meters annually. This rise in production has led to massive consumption of raw materials, underscoring the need to balance development with responsible environmental management by addressing resource scarcity and promoting sustainability [

4,

5,

6].

The management of organic waste, such as coffee bagasse, represents a significant environmental issue due to methane emissions, a greenhouse gas 21 times more potent than CO₂ [

7,

8,

9,

10]. In Ecuador, coffee consumption and export generate considerable waste, with 16381.05 metric tons of roasted and ground coffee residues produced. This scenario highlights the necessity for effective recycling methods to transform this waste into valuable resources [

11,

12,

13].

The use of biochar derived from organic residues in construction has been explored as an innovative solution to improve concrete properties while providing a sustainable alternative for waste management. Research has demonstrated that incorporating biochar can enhance the compressive strength of concrete, enabling the development of more durable and environmentally friendly infrastructure [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

Previous studies have shown that the concrete industry holds significant potential to increase the use of industrial byproducts and waste materials, including plastics, glass, ash, rubber, and various organic wastes. This trend not only reduces the extraction of natural resources required for concrete production but also enhances properties such as durability and strength [

20,

21]. Integrating these alternative materials promotes a more sustainable and efficient use of resources in construction, driving innovation toward more robust and durable infrastructure while advancing environmentally responsible practices and circular economy principles [

22,

23,

24].

Coffee-derived biochar has been specifically investigated for civil engineering and construction applications due to its small particle size. In a recent study, Mohamed and Djamila in 2018 [

25] examined the effects of incorporating coffee ash as a fine aggregate substitute in dune sand concrete at replacement levels of 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%. The findings revealed significant reductions in compressive and flexural strengths, with a 20% fine aggregate replacement causing a 44% decrease in compressive strength and a 68% reduction in flexural strength. Workability also diminished by approximately 77%.

Similarly, Eliche-Quesada et al. [

26] investigated the use of various waste materials in ceramic brick manufacturing. Their research showed that adding coffee ash increased the water absorption capacity of the bricks but negatively affected compressive strength and thermal conductivity.

Sena da Fonseca [

27] analyzed the effects of mixing clay with coffee ash for ceramic element production. They found that increasing the amount of coffee ash significantly reduced the modulus of rupture. Specifically, adding 5% coffee ash decreased strength by more than 30%, with a linear relationship observed between ash content and strength reduction.

This research is justified by its potential contributions to sustainable development and the improvement of construction material quality. By utilizing coffee bagasse, an abundant agricultural byproduct, as a fine aggregate replacement in concrete, this study seeks to enhance the mechanical properties of the material while promoting waste reuse and fostering a construction industry that is more conscious and responsible in its use of natural resources.

The aim of this study is to develop concrete mixes incorporating various proportions of coffee bagasse as a fine aggregate replacement to enhance compressive strength. The specific objectives are: (1) to conduct pyrolysis tests on coffee pulp samples, (2) to produce simple concrete with varying percentages of coffee bagasse addition, and (3) to perform mechanical compressive strength tests on cylindrical concrete samples.

2. Materials and Methods

The research was organized into several phases to achieve the study objectives. During the preliminary phase, coffee bagasse samples of various types were collected and air-dried. Subsequently, the samples were ground using a ball mill operating (DECO) [

28] at 250 rpm and subjected to pyrolysis in a furnace (IM&M 1200) at 349.5 °C to produce biochar. Finally, mortar cubes with varying proportions of biochar were prepared and tested in accordance with the NTE INEN 488 standard [

29].

In the initial phase, pyrolysis experiments were conducted using coffee bagasse from the “Lojano Arábica” variety. This material was characterized through Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) [

30] to evaluate its thermal behavior. Thermal activation was carried out at 349.5 °C to produce biochar.

During the second phase, plain concrete was prepared with different proportions of coffee bagasse (5%, 10%, and 20%) as replacement of fine aggregate. Aggregates and cement were collected and characterized following specific standards. Tests for moisture content, particle size distribution, and bulk density were conducted to ensure material quality.

In the final phase, compressive strength tests were performed on concrete cylinders with varying coffee bagasse proportions using a universal testing machine Shimadzu 2000X [

30]. These tests followed established standards and procedures to evaluate the mechanical strength and performance of the modified concrete.

1) Preliminary Phase

During this stage, coffee husk was collected from the most frequented coffee shops in Ambato, Ecuador. Three coffee types were sampled: Type 1 Lojano “Arabica,” Type 2 Blend “Arabica and Robusta,” and Type 3 “Robusta.”

The coffee samples were naturally dried in metal containers exposed to sunlight, using solar energy in its natural form to facilitate the spontaneous evaporation of any residual liquid. The three types of coffee husk were then ground using a ball mill at 250 rpm, followed by pyrolysis in an electric furnace at 349.5 °C for two hours to produce coffee biochar (BC).

Following the guidelines of the NTE INEN 488 standard, mortar was prepared using a mix of one part cement and 2.75 parts sand by weight [

29]. A total of 24 cubes, each with 50 mm edges, were prepared for each coffee type: 6 cubes with 10% and 20% sand replacement by raw coffee bagasse, 6 cubes with 10% and 20% sand replacement by coffee biochar, and 6 cubes with 0% coffee replacement as control samples. This resulted in a total of 78 specimens (

Table 1). The cubes were cured in a humidity chamber for seven days at a temperature of 23 ± 2 °C before undergoing compression testing (

Figure 1).

Based on the compression test results, Type 1 Lojano “Arabica” coffee was selected for the subsequent phases of the study.

2) Phase 1

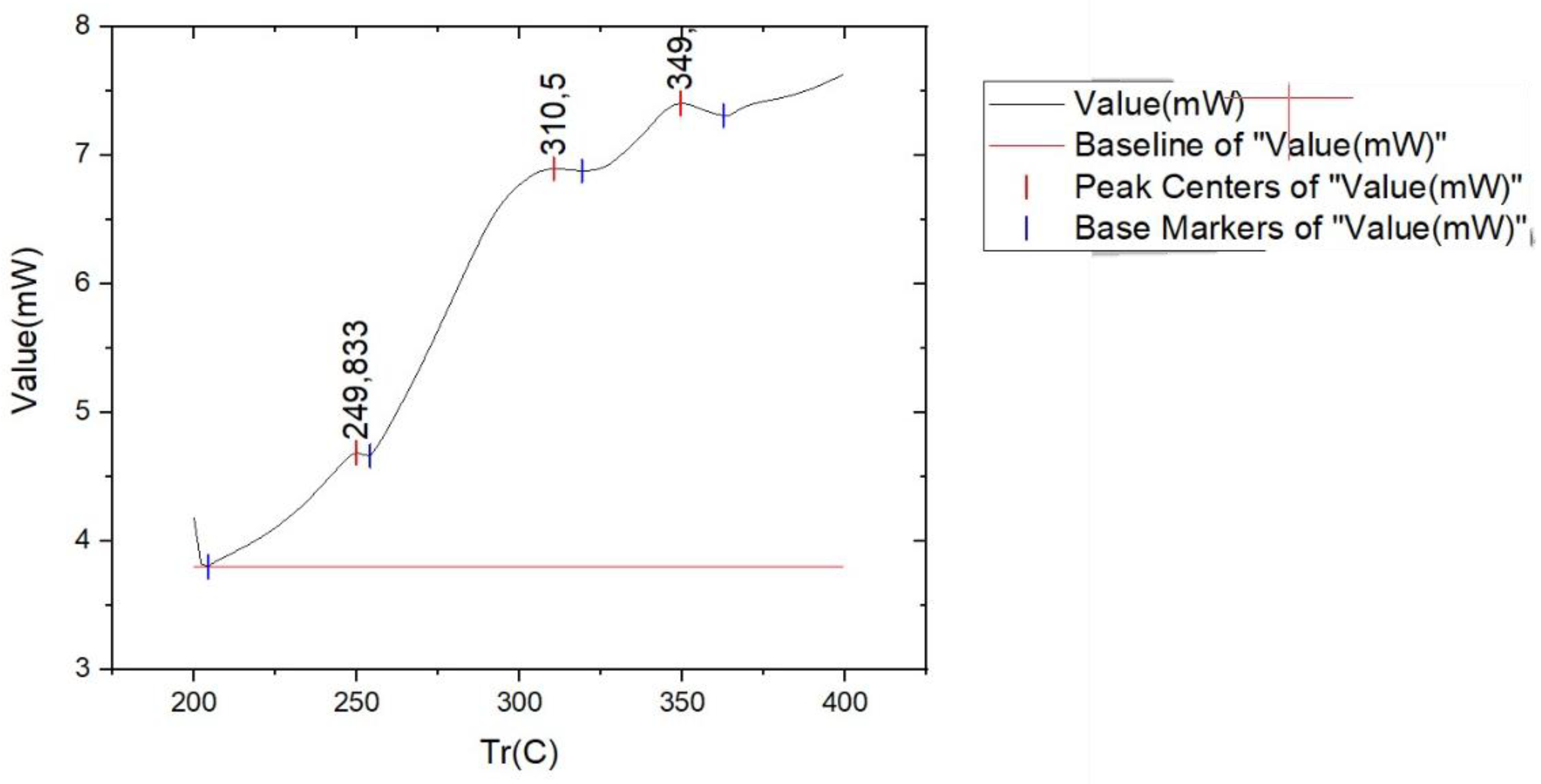

To determine the optimal temperature for the thermal activation of coffee bagasse, a Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) test was conducted (

Figure 2). DSC is a critical analytical technique used to study the thermal properties of materials, including heat capacity, phase transitions, melting temperature, crystallization, and other thermal behaviors. This method is particularly important in the characterization of polymers, metals, ceramics, and biological materials.

During the test, a sample of Type 1 coffee bagasse and a reference material were subjected to a controlled temperature program. The difference in heat flow between the sample and the reference material was measured as both were heated or cooled at a constant rate. This difference provided insights into the thermodynamic processes and the material’s behavior under varying thermal conditions.

After identifying the optimal activation temperature, the samples were completely cooled before proceeding with the preparation of the concrete.

3) Phase 2

Concrete was designed for a compressive strength of 21 MPa using the optimal density method. Selva Alegre Type IP cement, siliceous sand, and gravel with a fineness modulus of 2.76 and a maximum nominal aggregate size of ¾” were used. The physical properties of the aggregates required for mix design were determined through the following tests: granulometry (NTE INEN 696, 2011) [

31], bulk density (NTE INEN 858, 2010) [

32], relative density, absorption capacity of fine and coarse aggregates (NTE INEN 856, 2010; NTE INEN 857, 2010) [

33,

34], and the true density of cement (NTE INEN 0156, 2009) [

35].

A total of 42 concrete cylinders (200 mm x 100 mm) were prepared (

Table 2) according to NTE INEN 1573:2010 [

36] standards. 18 cylinders included 5%, 10%, and 20% additions of raw coffee bagasse (BC), while another 18 incorporated 5%, 10%, and 20% biochar (BC350) produced by pyrolysis of coffee bagasse at 349.5 °C. Six cylinders were designated as control samples (CS).

The specimens were cured in a humidity chamber for 28 days at a temperature of 23 ± 2 °C and a relative humidity of no less than 95%, in compliance with NTE INEN 1576 and NTE INEN 2528 standards [

37,

38]. Following the curing period, the cylinders were subjected to compressive strength testing.

4) Phase 3

Compression tests were conducted on the 42 cylinders in accordance with the NTE INEN 1573 and ACI 318-19 standards [

36,

39]. The tests were conducted using a universal testing machine, with a maximum load capacity of 2000 kN. The load was applied at a constant rate of 0.25 ± 0.05 MPa/s, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

The purpose of these tests was to determine the compressive strength and elastic modulus of the concrete, as calculated using Equations (1) and (2).

For concrete with a unit weight ranging between 1440 and 2560 kg/m³:

Where:

Ec: Elastic Modulus.

wc: Unit weight /Density Kg/m3

f’

c: Specified compressive strength of the concrete.

For normal-weight concrete:

Where:

Ec: Elastic Modulus.

f’c: Specified compressive strength of the concrete.

The experimental results were compared between control samples and those containing varying proportions of coffee bagasse and coffee biochar (5%, 10%, and 20%) as replacements for fine aggregate.

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents the laboratory results obtained from the predefined experimental procedures. The findings are summarized through tables and graphs for clarity.

Preliminary Phase

Preparation and compressive strength testing of 50 mm mortar cubes

The compressive strength tests on 50 mm mortar cubes were conducted in accordance with the procedures outlined in the NTE INEN 488 standard. After a curing period of 7 days, the cubes were subjected to compressive strength tests.

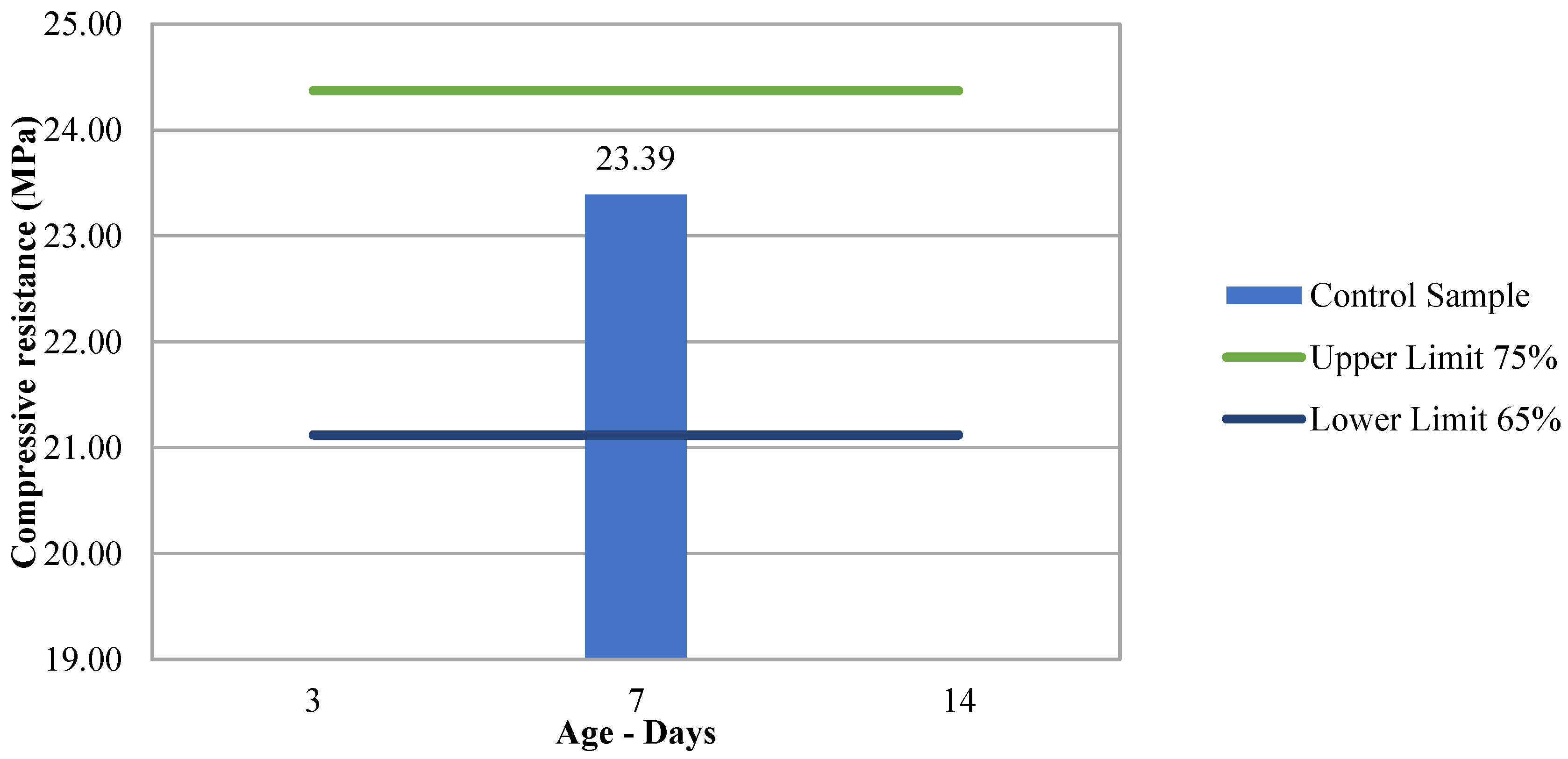

Control Sample

The average density of the mortar cubes, designated as the “Control Sample,” was measured at 1859.07 kg/m³. This value falls within the expected density range for hardened mortars, typically between 1800 kg/m³ and 2000 kg/m³ [

40]. This appropriate density indicates compliance with technical and regulatory specifications, affirming the suitability of the mortar for structural and masonry applications.

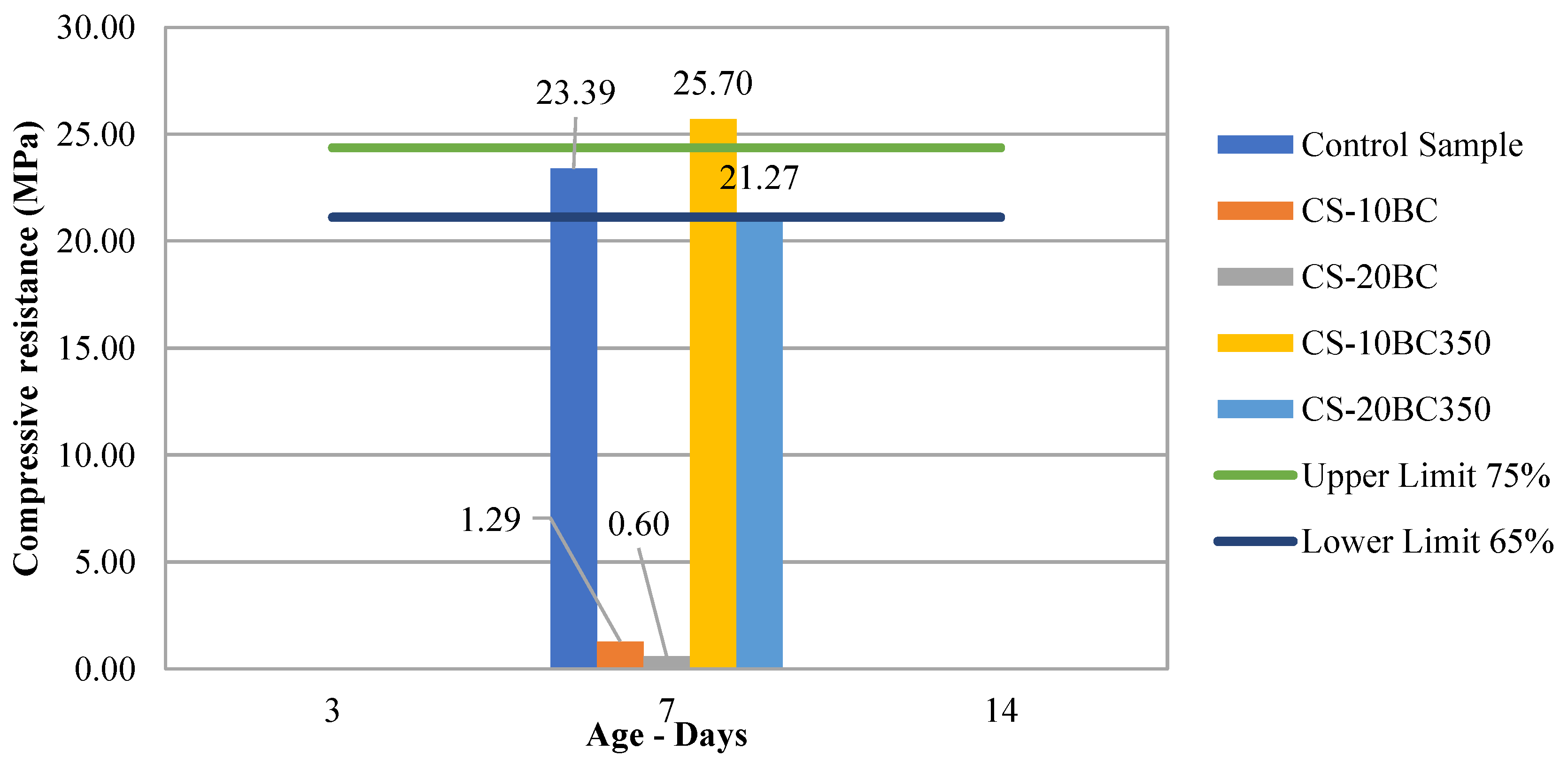

In terms of compressive strength, the 7-day average was recorded at 23.39 MPa, representing 72.00% of the expected strength. This value aligns with the anticipated range of 65% to 75% of the target strength (21.12 MPa to 24.37 MPa), as illustrated in

Figure 4.

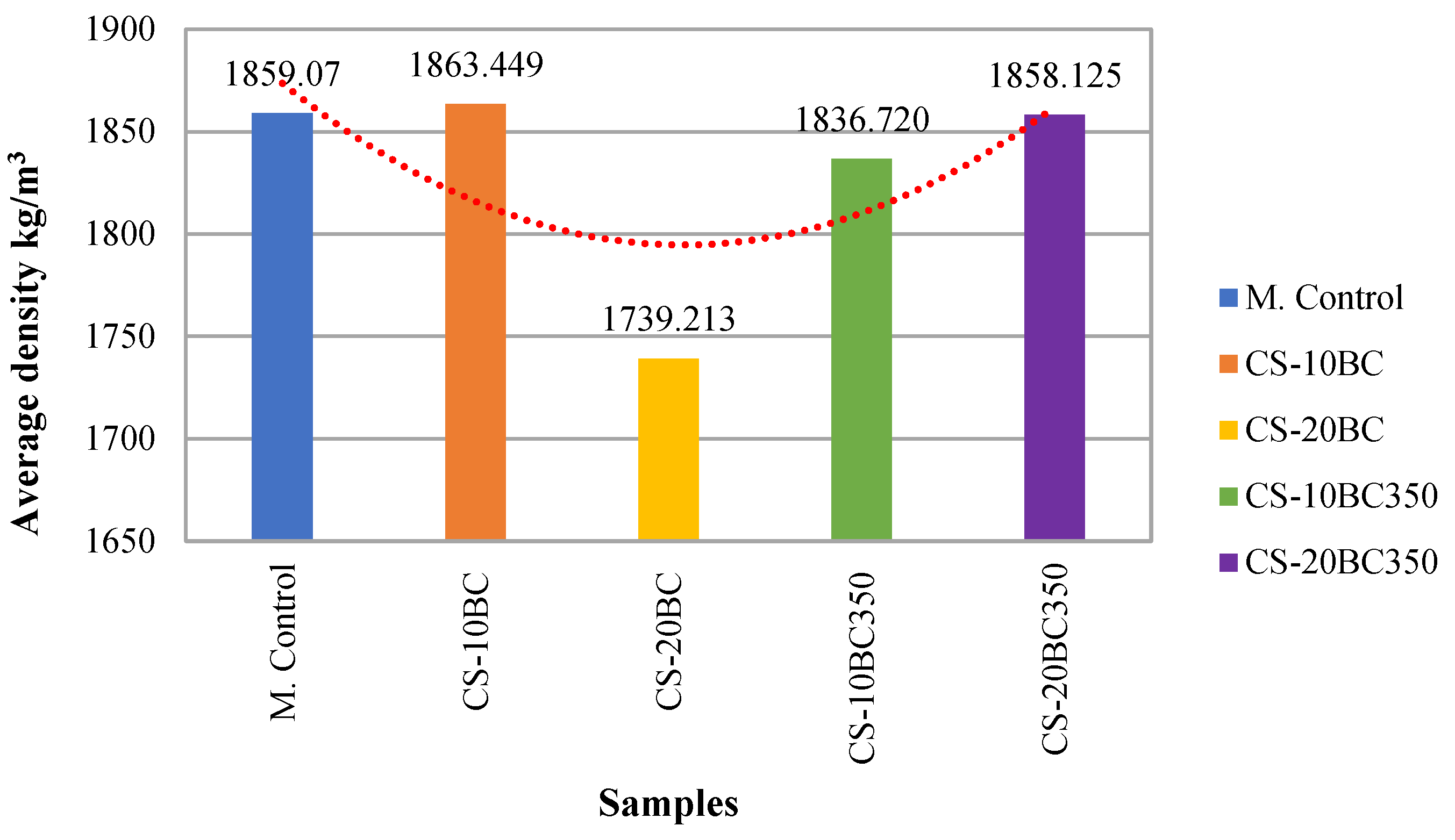

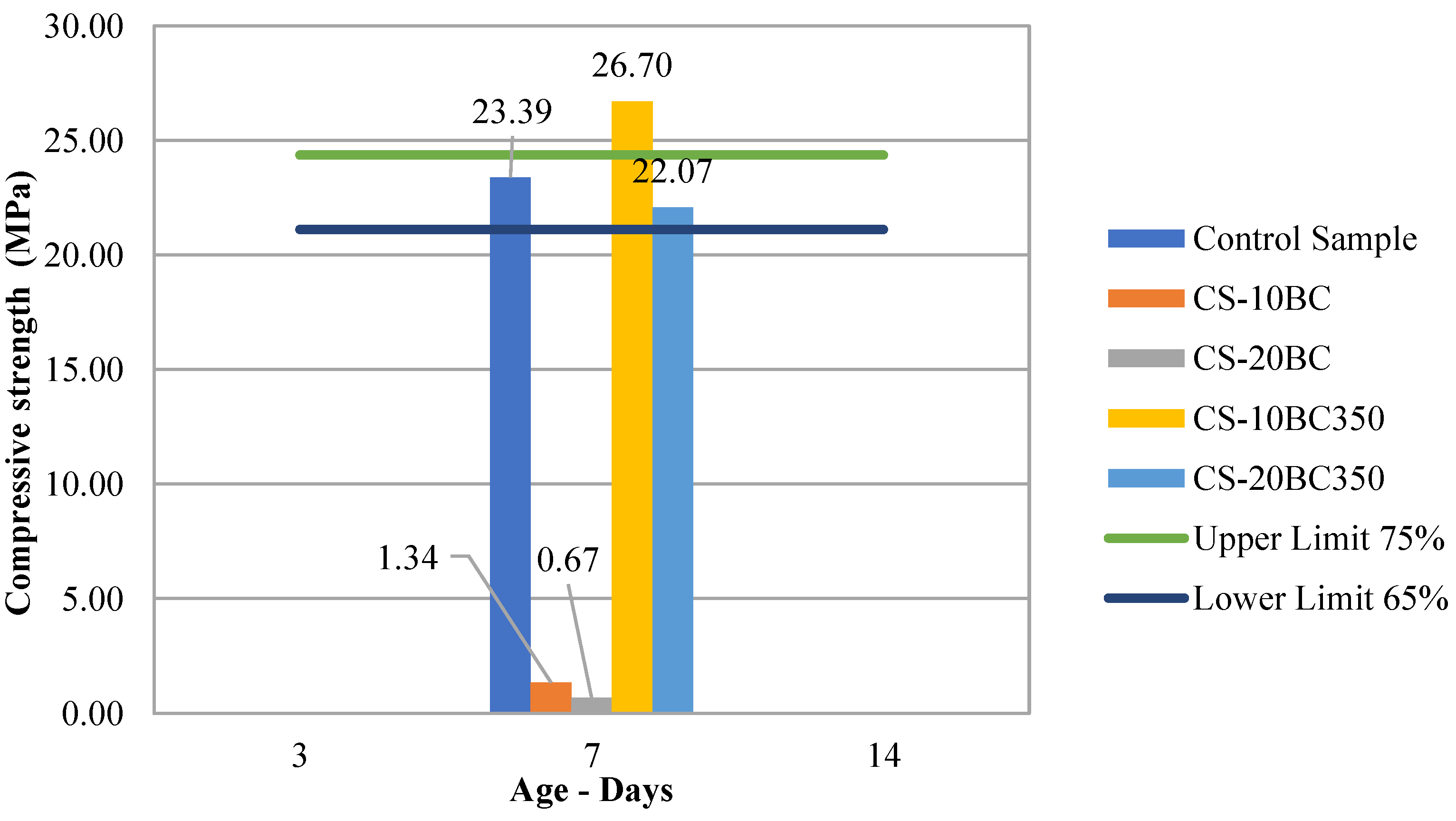

Density and Compressive strength of mortar cubes with Coffee Type 1 – Lojano Coffee “Arabica”

The average density of mortar cubes (

Figure 5) yielded the following results: 1863.449 kg/m³ for CS - 10BC, 1739.213 kg/m³ for CS - 20BC, 1836.720 kg/m³ for CS - 10BC350, and 1858.125 kg/m³ for CS - 20BC350. It is observed that only the average density corresponding to CS - 20BC was outside the expected range. The other values were within the anticipated range for hardened mortar densities, which spans from 1800 kg/m³ to 2000 kg/m³ [

40].

Regarding compressive strength, the average results for the mortar cubes incorporating Coffee Type 1 – Lojano Coffee “Arabica,” evaluated at 7 days, were as follows: 1.34 MPa for CS - 10BC, representing a 94.29% reduction in strength; 0.67 MPa for CS - 20BC, indicating a 97.14% reduction in strength; 26.7 MPa for CS - 10BC350, demonstrating a significant 14.13% increase in strength; and 22.07 MPa for CS - 20BC350, indicating a 5.66% decrease in strength. These values were compared to the control sample, which was considered the baseline (100% reference strength). It is important to highlight that these results fell within the expected strength range of 65% to 75% (21.12 MPa to 24.37 MPa), as illustrated in

Figure 6.

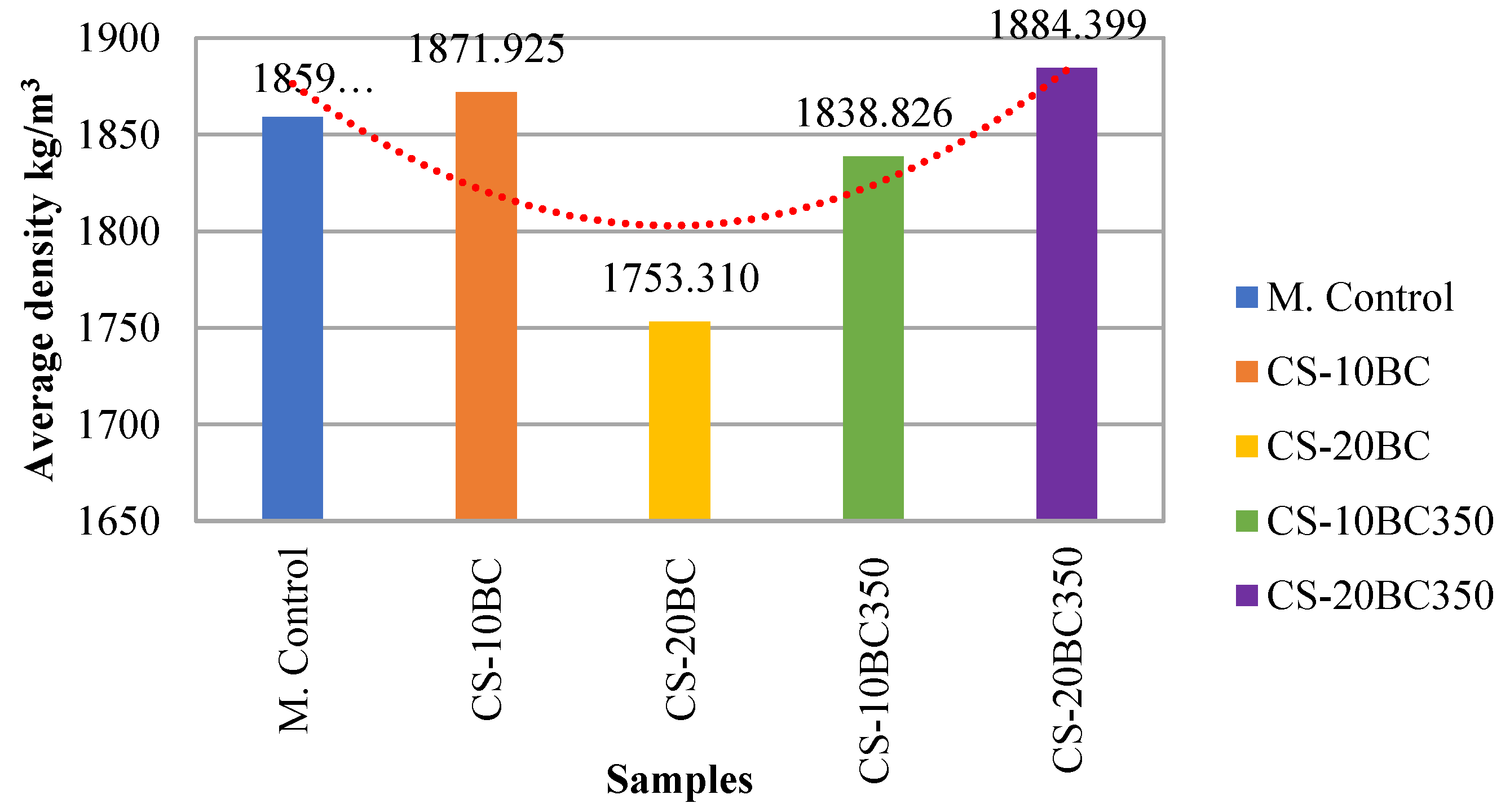

Density and Compressive strength of mortar cubes with Coffee Type 2 – Blend “Arabica and Robusta”

The average density of mortar cubes for Coffee Type 2 – Blend

“Arabica and Robusta

” (

Figure 7) showed the following results: 1871.925 kg/m³ for CS - 10BC, 1753.310 kg/m³ for CS - 20BC, 1838.826 kg/m³ for CS - 10BC350, and 1884.399 kg/m³ for CS - 20BC350. Similar to the results for Coffee Type 1, only the density of CS - 20BC was outside the expected range, while the remaining values were within the acceptable range for hardened mortar densities (1800 kg/m³ to 2000 kg/m³).

The compressive strength of the mortar cubes, measured at 7 days, revealed the following results: 1.29 MPa for CS - 10BC, indicating a 94.50% reduction in strength; 0.60 MPa for CS - 20BC, reflecting a 97.43% reduction in strength; 25.70 MPa for CS - 10BC350, representing a notable 9.87% increase in strength; and 21.27 MPa for CS - 20BC350, reflecting a 9.08% reduction in strength. As with Coffee Type 1, these results were compared to the control sample, taken as the baseline (100% reference strength). All results were within the expected strength range of 65% to 75% (21.12 MPa to 24.37 MPa), as shown in

Figure 8.

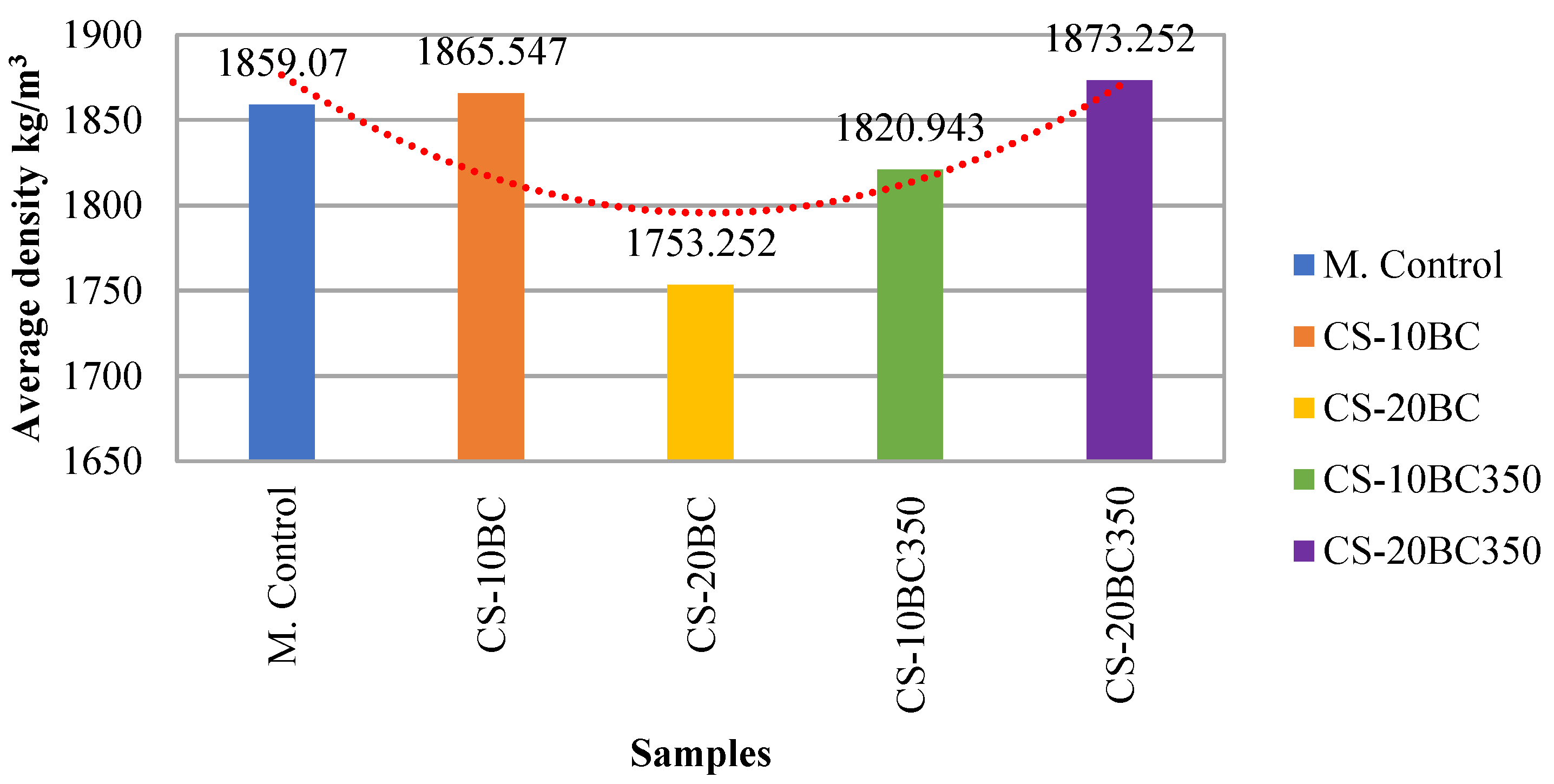

Density and Compressive Strength of Mortar Cubes with Coffee Type 3 – “Café Robusta”.

The average density of mortar cubes incorporating Coffee Type 3

“Café Robusta

” (

Figure 9) showed the following results: 1865.547 kg/m³ for CS - 10BC, 1753.252 kg/m³ for CS - 20BC, 1820.943 kg/m³ for CS - 10BC350, and 1873.252 kg/m³ for CS - 20BC350. It is observed that the density corresponding to CS - 20BC fell outside the expected range, while the other values were within the acceptable range for hardened mortar densities, which spans from 1800 kg/m³ to 2000 kg/m³.

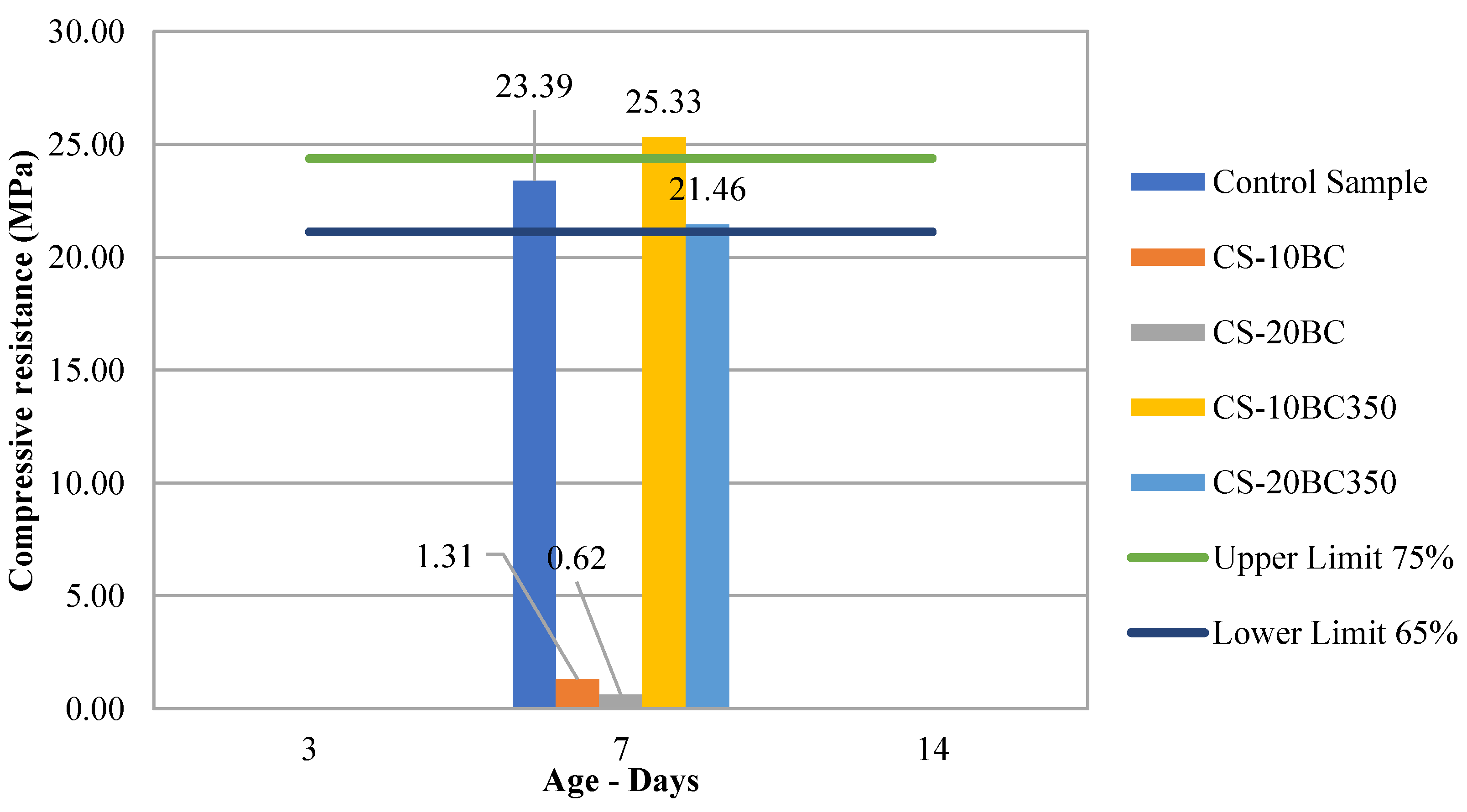

The compressive strength of the 50 mm mortar cubes evaluated at 7 days showed the following results: 1.31 MPa for CS - 10BC, representing a 94.38% reduction in strength; 0.62 MPa for CS - 20BC, indicating a 97.35% reduction in strength; 25.33 MPa for CS - 10BC350, demonstrating a notable 8.27% increase in strength; and 21.46 MPa for CS - 20BC350, reflecting an 8.24% decrease in strength. These values were compared to the control sample, considered the baseline (100% reference strength). All results fell within the expected strength range of 65% to 75% (21.12 MPa to 24.37 MPa), as illustrated in

Figure 10.

Comparison and Selection of Coffee Types

After tabulating and interpreting the compressive strength test results for the coffee-based samples, it was concluded that all three coffee types exhibited similar behavior. Incorporating 10% coffee biochar produced at 350°C, samples tend to increase their compressive strength. Coffee Type 1 – Lojano Coffee “Arabica” showed the best results, achieving a compressive strength of 26.70 MPa, which corresponds to a 14.13% increase compared to the control sample. Additionally, a substantial reduction in average density was observed with the inclusion of the indicated percentage of biochar. Consequently, Coffee Type 1 was selected for use in subsequent phases of the research due to its promising performance.

Phase 1: Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Analysis

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) was employed to characterize the thermal behavior of the studied material. The selected sample, Coffee Type 1 – Lojano

“Café Arábica,

” was exposed to a controlled temperature program to evaluate its thermal properties, including phase transitions and thermal stability. The results revealed endothermic and exothermic peaks indicative of specific events within the material. The first transition peak was observed at 204.33 °C. Between 204.33 °C and 349.50 °C, the material exhibited endothermic behavior. Beyond 349.50 °C, the sample began to melt, ultimately entering the degradation phase at approximately 400 °C (

Figure 11). Based on these observations, the optimal activation temperature for the material was determined to be 349.50 °C, at which thermal activation was conducted.

Phase 2: Fresh-state density of concrete samples.

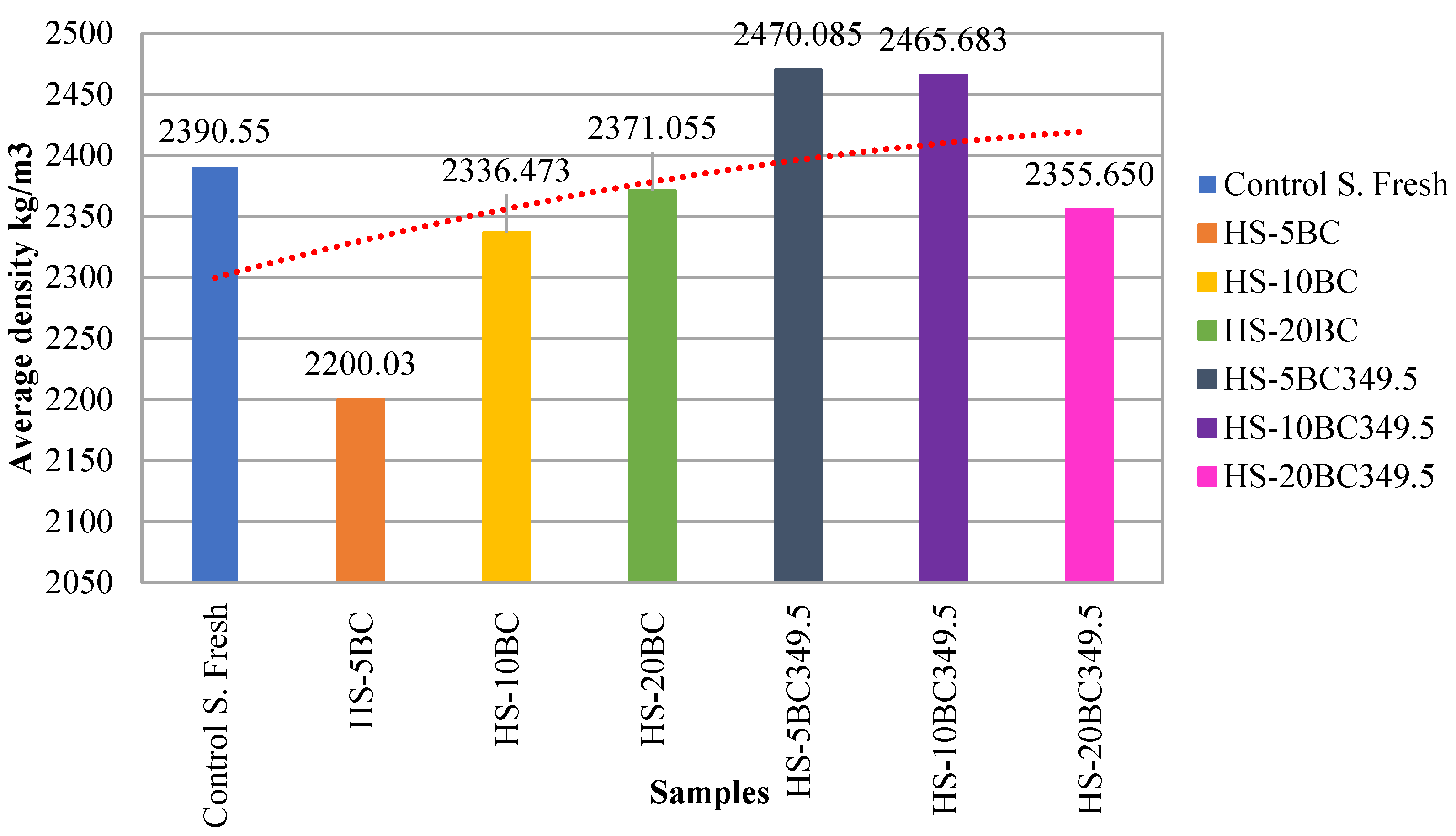

The average density of the samples in fresh-state (

Figure 12) yielded the following results: 2390.550 kg/m³ for the control sample, 2200.030 kg/m³ for HS - 5BC, 2336.473 kg/m³ for HS - 10BC, 2371.055 kg/m³ for HS - 20BC, 2470.085 kg/m³ for HS - 5BC349.5, 2465.683 kg/m³ for HS - 10BC349.5, and 2355.650 kg/m³ for HS - 20BC349.5. These values fall within the typical range for concrete, which varies between 2200 kg/m³ and 2300 kg/m³ in the fresh state, and between 2200 kg/m³ and 2400 kg/m³ in the hardened state, respectively.

Average density of samples

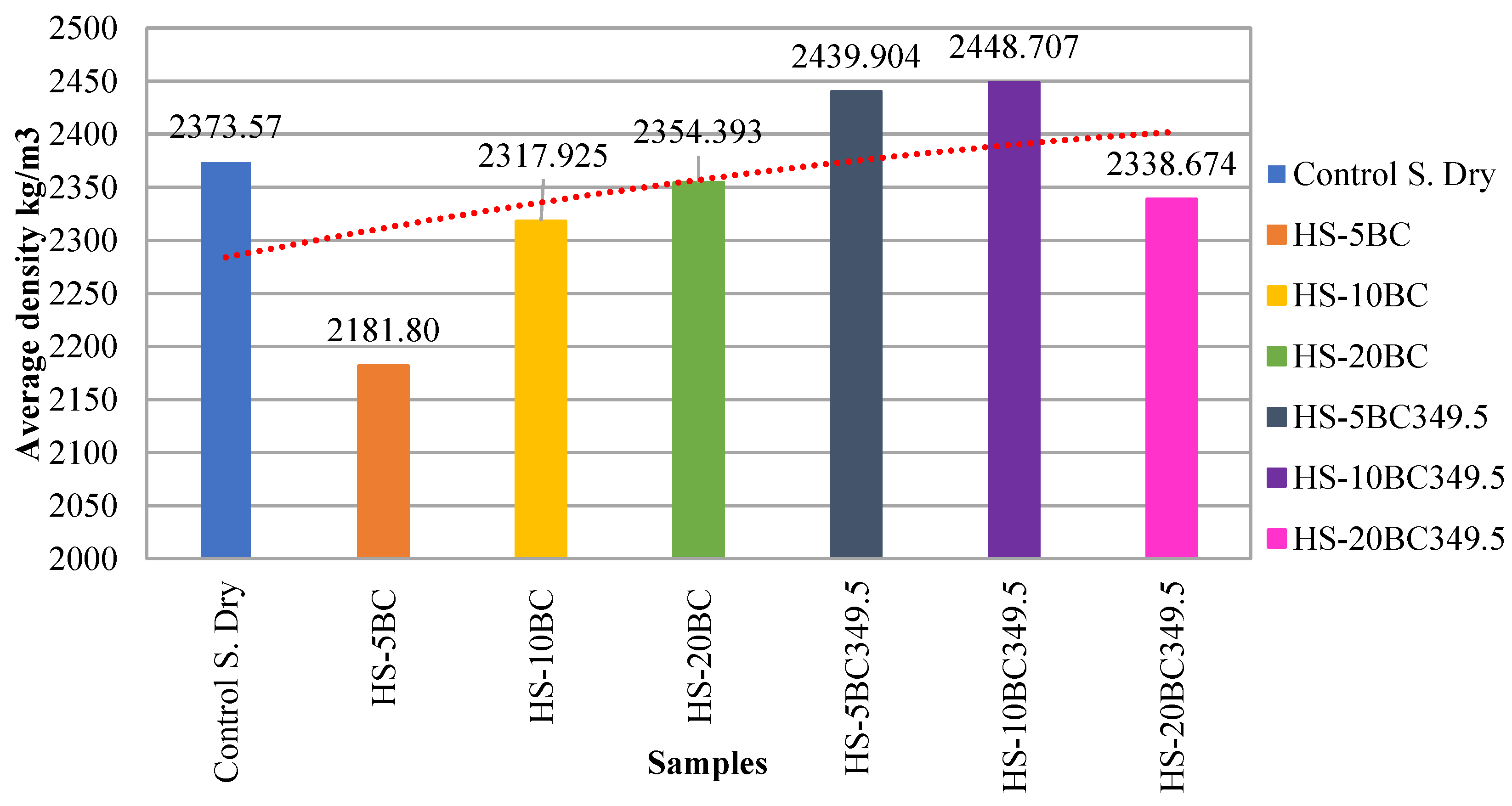

The average density in dry-state of the selected samples showed the following results: 2373.570 kg/m³ for the control sample, 2181.800 kg/m³ for HS - 5BC, 2317.925 kg/m³ for HS - 10BC, 2354.393 kg/m³ for HS - 20BC, 2439.904 kg/m³ for HS - 5BC349.5, 2448.707 kg/m³ for HS - 10BC349.5, and 2338.674 kg/m³ for HS - 20BC349.5. These values fall within the typical range for simple concrete, which spans from 2200 kg/m³ to 2300 kg/m³ in the fresh state, and from 2200 kg/m³ to 2400 kg/m³ in the hardened state, respectively as shown in

Figure 13.

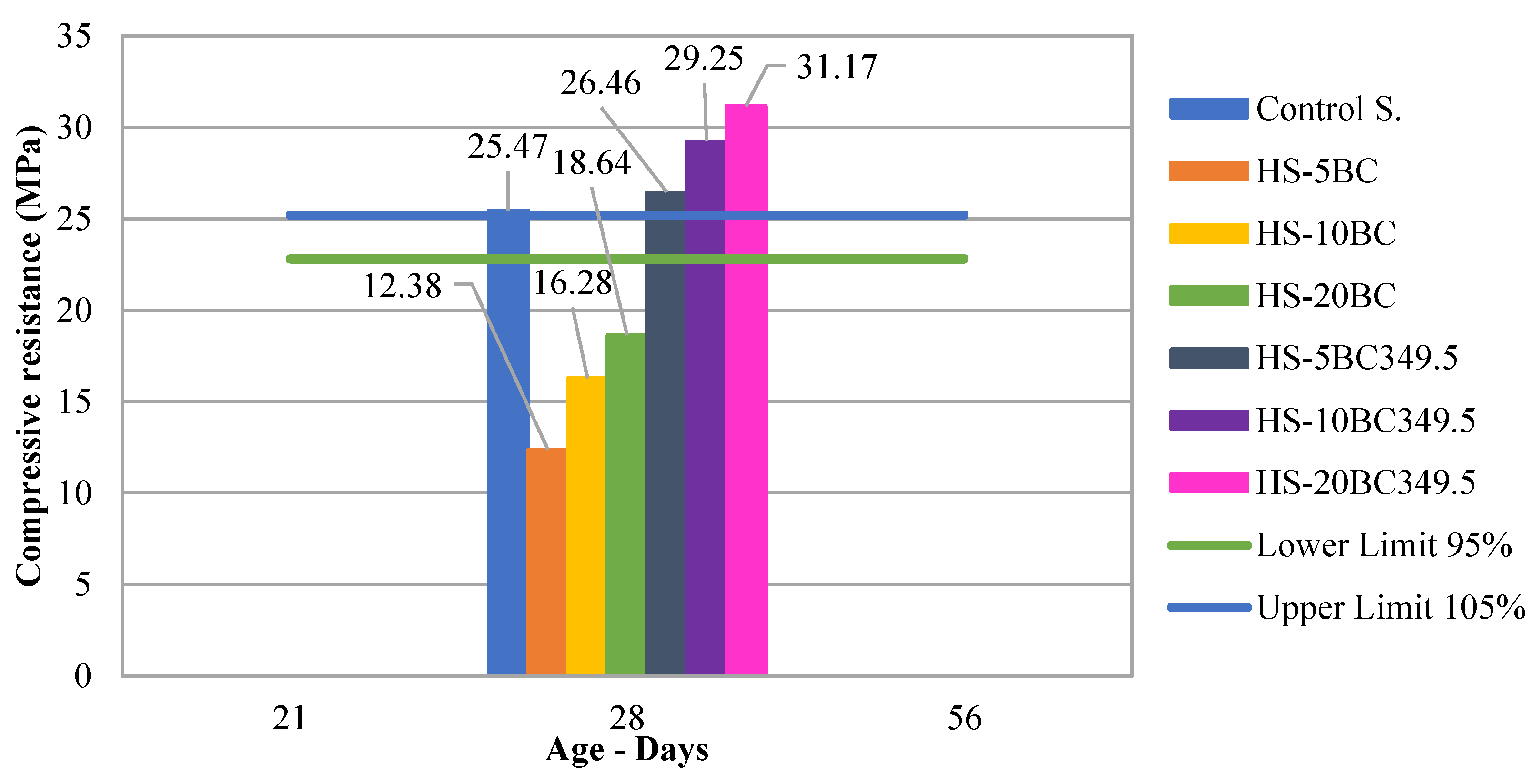

Phase 3: Compressive Strength of Final Specimens

Figure 14 presents the results of the compressive strength tests conducted on the selected samples, yielding the following values: 25.47 MPa for the control sample, 12.38 MPa for HS - 5BC (a 51.38% reduction), 16.28 MPa for HS - 10BC (a 36.08% reduction), and 18.64 MPa for HS - 20BC (a 26.82% reduction). For specimens incorporating coffee biochar activated at 349.50 °C, the following values were obtained: 26.46 MPa for HS - 5BC349.5, representing a 3.88% increase; 29.25 MPa for HS - 10BC349.5, reflecting a 14.82% increase; and 31.17 MPa for HS - 20BC349.5, indicating a 22.39% increase. These values were compared against the control sample, which served as the reference with 100% relative strength. All results were evaluated within the expected strength range of 95% to 105% (22.36 MPa to 24.71 MPa).

Elastic Modulus

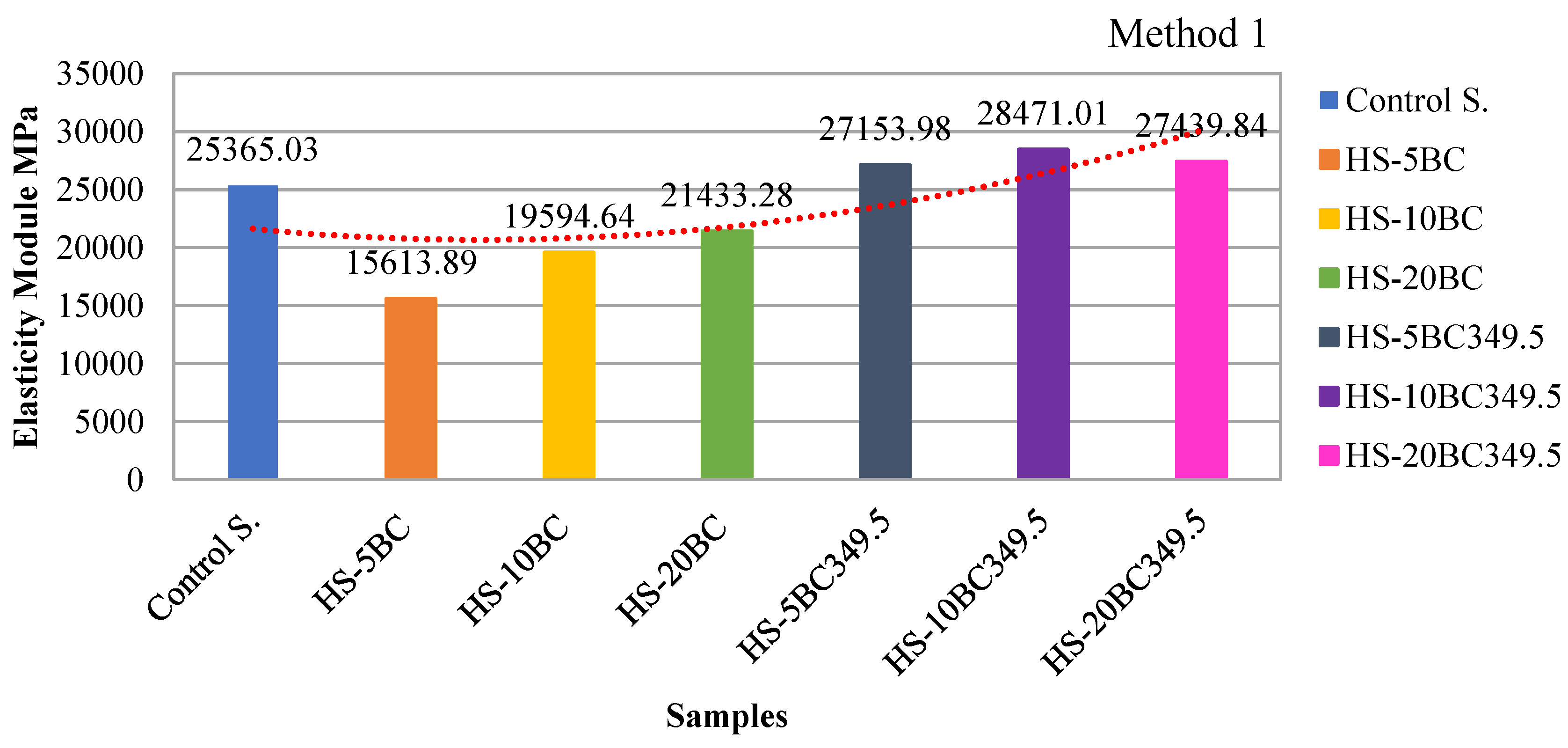

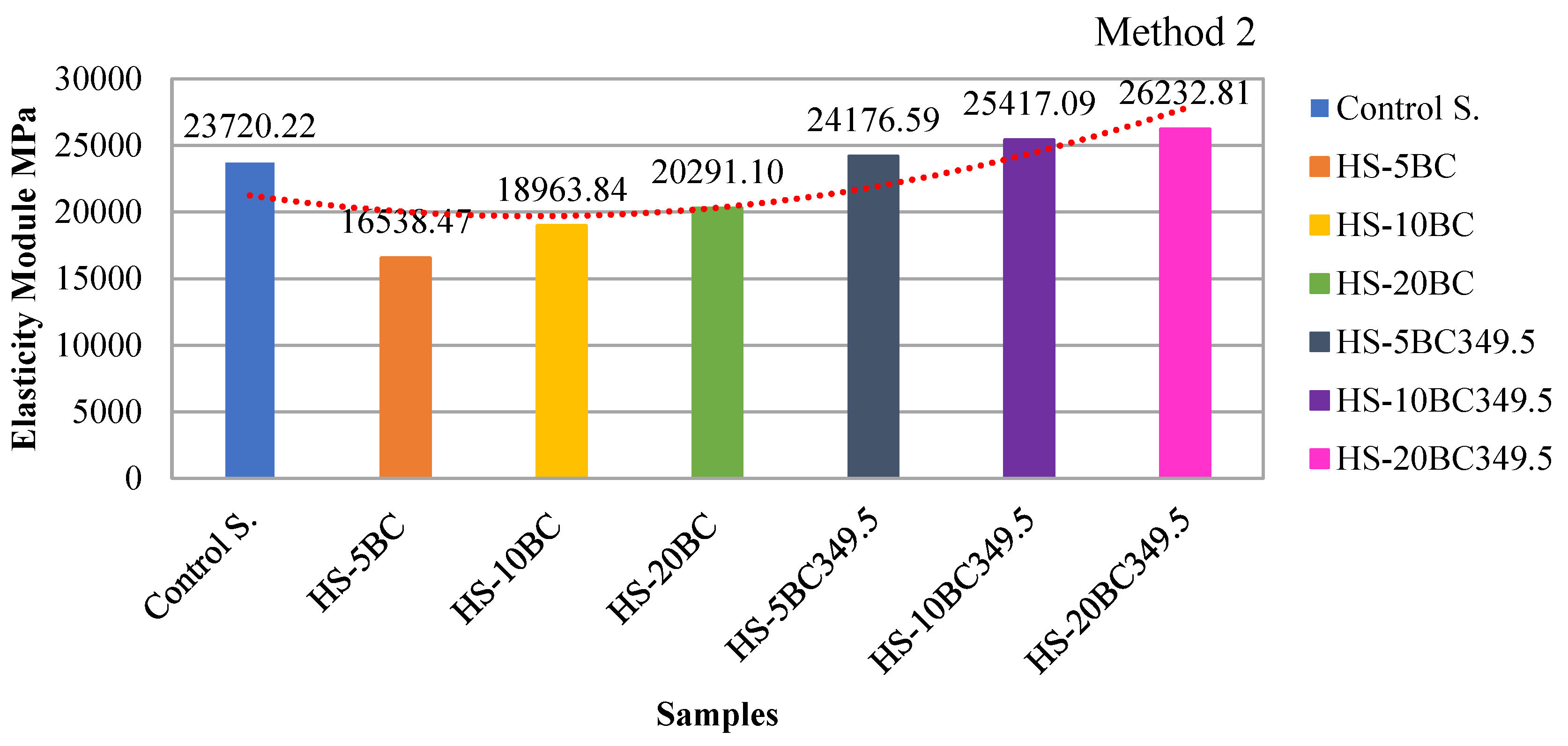

Figure 15 and

Figure 16 present the results of the concret

e’s elastic modulus evaluated using two different methods, comparing mixtures with varying percentages of coffee bagasse and coffee biochar additions. For samples containing coffee bagasse, Method 1 showed reductions of 38%, 22%, and 15% for HS-5BC, HS-10BC, and HS-20BC, respectively. While Method 2 indicated decreases of 30%, 20%, and 14% for the same samples. In contrast, samples with coffee biochar activated at 349.50 °C demonstrated improvements in the elastic modulus. Method 1 reported increases of 7%, 12%, and 8% for HS-5BC349.5, HS-10BC349.5, and HS-20BC349.5, respectively, while Method 2 revealed increments of 1.9%, 7%, and 11% for the corresponding samples. These results, compared to the control sample, indicate that mixtures with higher concentrations of biochar activated at 349.50 °C significantly enhance the elastic modulus, this tendency was consistently observed across both evaluation methods.

4. Conclusions

Differential scanning calorimetry and compressive strength tests on hydraulic cement mortars were used to select a coffee species that allowed the production of simple concrete based on raw bagasse and biochar as a replacement for fine aggregate in different percentages, allowing the evaluation of the behavior of the concrete based on its mechanical properties.

The study demonstrated that incorporating 10% coffee biochar activated at 349.5 °C significantly enhances the compressive strength of mortar, with Café TIPO 1 – Café Lojano “Arábica” exhibiting the best performance. This type of coffee not only increases strength by 14.13% compared to the control sample but also reduces the average density of the mortar.

Pyrolysis tests conducted on coffee bagasse samples revealed that the optimal activation temperature is 349.5 °C. This was determined through differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), which identified significant endothermic and exothermic events at this temperature, including phase transitions and material degradation at 400 °C.

The findings further indicate that adding coffee grounds to concrete is a feasible approach that improves key material properties. Based on the results of 28-day compressive strength tests on concrete cylinders with different percentages of coffee addition, 10% of coffee grounds biochar is determined to be the optimal ratio for improving concrete strength. This specific ratio demonstrated a remarkable increase of 22.39% in compressive strength and 12% in elastic modulus compared to concrete without coffee addition. Although a 20% addition significantly reduced the density, the 10% ratio offers the best balance between strength and density, establishing a solid foundation for the sustainable use of biological resources in civil engineering.

The studies carried out in this research correspond to three types of coffee used as a replacement for fine aggregate. For future research, it is recommended to test with other species that can be used as a replacement or addition.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, L.C., M.S., W.R. and A.A.; methodology, W.R., M.M. M.S. and L.C.; validation, W.R., M.M., M.S. and L.C.; formal analysis, W.R., M.S.; investigation, A.A.; data curation, W.R., M.S. and L.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A., W.R., M.M, and L.C.; writing—review and editing, W.R., M.M, and L.C.; supervision, W.R., L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

The authors acknowledge the Universidad Técnica de Ambato for its financial support through the Research and Development Direction (DIDE) for funding this research under the Project resolution Nro. UTA-CONIN-2025-0050-R: “Reutilización de desechos sólidos provenientes del polvo de lijado y viruta de cuero generados en La Curtiduría Tungurahua, para la mejora de las propiedades del concreto y mortero de cemento hidráulico, reduciendo la huella de carbono generada por la industria”.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly acknowledge the support of the Faculty of Civil and Mechanical Engineering and the Research and Development Directorate of the Technical University of Ambato for the availability provided for the development of this study. In addition, the authors acknowledge the continuous support of the “Gestión de Recursos Naturales e Infraestructura Sustentable” (GeReNIS) research group at Universidad Técnica de Ambato.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- OECD (2024) Infrastructure for a Climate-Resilient Future. OECD.

- Wang L, Wang J, Qian X, et al. (2017) An environmentally friendly method to improve the quality of recycled concrete aggregates. Constr Build Mater 144:432–441. [CrossRef]

- InterNACHI The History of Concrete - InterNACHI®. https://www.nachi.org/history-of-concrete.htm. Accessed 11 Feb 2025.

- World Economic Forum Sustainable concrete is possible – here are 4 examples | World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/09/cement-production-sustainable-concrete-co2-emissions/. Accessed 11 Feb 2025.

- Soomro M, Tam VWY, Jorge Evangelista AC (2023) Production of cement and its environmental impact. In: Recycled Concrete. Elsevier, pp 11–46.

- Marsh ATM, Velenturf APM, Bernal SA (2022) Circular Economy strategies for concrete: implementation and integration. J Clean Prod 362:132486. [CrossRef]

- Shabir I, Dash KK, Dar AH, et al. (2023) Carbon footprints evaluation for sustainable food processing system development: A comprehensive review. Future Foods 7:100215. [CrossRef]

- Vinci G, Ruggieri R, Billi A, et al. (2021) Sustainable Management of Organic Waste and Recycling for Bioplastics: A LCA Approach for the Italian Case Study. Sustainability 13:6385. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Qin D, Hu Y, et al. (2022) A systematic review of waste materials in cement-based composites for construction applications. Journal of Building Engineering 45:103447. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Yang M, Chen Z, et al. (2024) Conversion of waste into sustainable construction materials: A review of recent developments and prospects. Materials Today Sustainability 27:100930. [CrossRef]

- Holland Circular Hotspot (2021) Waste Management in the LATAM Region: Ecuador.

- Pazmiño ML, Mero-Benavides M, Aviles D, et al. (2024) Life cycle assessment of instant coffee production considering different energy sources. Cleaner Environmental Systems 12:. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt Rivera XC, Gallego-Schmid A, Najdanovic-Visak V, Azapagic A (2020) Life cycle environmental sustainability of valorisation routes for spent coffee grounds: From waste to resources. Resour Conserv Recycl 157:104751. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, He M, Wang L, et al. (2022) Biochar as construction materials for achieving carbon neutrality. Biochar 4:59. [CrossRef]

- Barbhuiya S, Bhusan Das B, Kanavaris F (2024) Biochar-concrete: A comprehensive review of properties, production and sustainability. Case Studies in Construction Materials 20:e02859. [CrossRef]

- Legan M, Gotvajn AŽ, Zupan K (2022) Potential of biochar use in building materials. J Environ Manage 309:114704. [CrossRef]

- Cui J, Fu D, Mi L, et al. (2023) Effects of Thermal Treatment on the Mechanical Properties of Bamboo Fiber Bundles. Materials 16:1239. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Ding D, Zhao J, et al. (2022) Mixture Design and Mechanical Properties of Recycled Mortar and Fully Recycled Aggregate Concrete Incorporated with Fly Ash. Materials 15:8143. [CrossRef]

- Li C, Mei X, Dias D, et al. (2023) Compressive Strength Prediction of Rice Husk Ash Concrete Using a Hybrid Artificial Neural Network Model. Materials 16:3135. [CrossRef]

- Na S, Lee S, Youn S (2021) Experiment on Activated Carbon Manufactured from Waste Coffee Grounds on the Compressive Strength of Cement Mortars. Symmetry (Basel) 13:619. [CrossRef]

- Gupta S, Kua HW, Koh HJ (2018) Application of biochar from food and wood waste as green admixture for cement mortar. Science of The Total Environment 619–620:419–435. [CrossRef]

- Brito J, Kurda R (2021) The past and future of sustainable concrete: A critical review and new strategies on cement-based materials. J Clean Prod 281:123558. [CrossRef]

- Ali RA, Kharofa OH (2021) The impact of nanomaterials on sustainable architectural applications smart concrete as a model. Mater Today Proc 42:3010–3017. [CrossRef]

- Nilimaa J (2023) Smart materials and technologies for sustainable concrete construction. Developments in the Built Environment 15:100177. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed G, Djamila B (2018) Properties of dune sand concrete containing coffee waste. MATEC Web of Conferences 149:01039. [CrossRef]

- Eliche-Quesada D, Martínez-García C, Martínez-Cartas ML, et al. (2011) The use of different forms of waste in the manufacture of ceramic bricks. Appl Clay Sci 52:270–276. [CrossRef]

- Sena da Fonseca B, Vilão A, Galhano C, Simão JAR (2014) Reusing coffee waste in manufacture of ceramics for construction. Advances in Applied Ceramics 113:159–166. [CrossRef]

- China Planetary Ball Mill, Laboratory Ball Mill, Ball Mill Jar, Grinding Meida Balls Manufacturers & Suppliers & Factory - Changsha Deco Equipment Co.,Ltd. https://www.deco-ballmill.com/. Accessed 11 Feb 2025.

- NTE INEN 488 (2009) Cemento Hidráulico. Determinación de la Resistencia a la Compresión de Morteros en Cubos de 50 mm de arista.

- DSC Differential Scanning Calorimeter factory, Buy good quality DSC Differential Scanning Calorimeter products from China. https://www.glomro.com/supplier-434656-dsc-differential-scanning-calorimeter. Accessed 11 Feb 2025.

- 2011; 31. NTE INEN 696 (2011) Análisis Granulométrico en Agregados Finos y Gruesos.

- 2010; 32. NTE INEN 858 (2010) Determinación de la Masa Unitaria.

- NTE INEN 857 (2010) Determinación de la densidad, densidad relativa y absorción del árido grueso.

- NTE INEN 856 (2010) Determinación de la Densidad de Áridos.

- NTE INEN 0156 (2009) Determinación de la densidad del cemento hidráulico.

- NTE INEN 1573 (2010) Determinación de la resistencia a la compresión de especímenes cilíndricos de hormigón de cemento hidráulico.

- NTE INEN 1576 (2011) Elaboración y curado en obra de especímenes para ensayo.

- NTE INEN 2528 (2010) Cámaras de Curado, Gabinetes Húmedos, Tanques para Almacenamiento en Agua y Cuartos para Elaborar Mezclas, utilizados en muestras de Cemento Hidráulico y Hormigón. Requisitos.

- 2019; 39. ACI 318-19 (2019) Requisitos de Reglamento para Concreto Estructural.

- NEC-SE-CG (2015) Seguridad Estructural de las Edificaciones. Cargas no sísmicas.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).