1. Introduction

Smart-home data governance has become a global concern as cities pursue low-carbon operation, resilient housing, and accountable information flows across the building life cycle. Recent reviews and practice reports emphasize digital-twin adoption—especially for operations and energy analytics—yet evidence from the design stage on object-level identity governance, consumption-side handover, and auditable processes remains limited [

20,

23,

32]. This study addresses that gap by operationalizing Industry Foundation Classes Globally Unique Identifier-22 (IfcGUID-22) compliance and Common Data Environment (CDE)-based traceability in design, and by closing the loop to downstream visualization/game engines and audit.

A smart home refers to residential buildings where sensors, devices, and data services are systematically embedded to provide data-driven capabilities for occupant experience, energy efficiency, and operations and maintenance [

23,

32]. Digital-twin assets denote object-level digital representations for the consumption side—such as visualization/game engines and O&M platforms—that can be used directly for rendering, interaction, and business linkage; they serve as data carriers connecting the design model with downstream applications [

23,

32]. This research targets the “non-standard data” exposed when digital twins and visualization engines are introduced at the design stage of smart-home projects and proposes and validates a practical standardization workflow (“non-standard to standard”). Practice shows that once the consumption side (e.g., the representative game engine Unity) contains non-standard data—object identifiers that are inconsistent, missing, or invalid—cross-system reconciliation and traceability are quickly blocked, leading to rework and a broken chain of evidence. The aim is to turn consumption-side non-standard data into standard-compliant, auditable data streams already at the design stage, serving Building Information Modeling (BIM) and CDE managers, visualization and engine teams, and owners/auditors to reduce breakage and rework at the source; industry studies likewise indicate that the cost of “bad data” is substantial [

10].

Building data management for smart homes concerns the organization, quality control, and traceability governance of life-cycle models, metadata, and versions. Its management anchor is the Common Data Environment (CDE): under ISO 19650 and UK BIM Framework, each information container should have a unique identifier, use agreed naming, and pass through controlled processes for creation, review, and release [

3,

4]. To make subsequent comparison and audit evidenced, we implement traceability-oriented governance in the CDE—registering paths, timestamps, and checksums for key inputs/outputs, measurement configurations, and results—so every number can be traced to a concrete file and command [

4].

Cross-system consistent identification depends on object-level primary keys. At the open-standards layer, buildingSMART’s Industry Foundation Classes (IFC, ISO 16739-1) is the international standard for cross-platform exchange and sharing; its object key IfcGUID has a fixed 22-character exchange representation, and toolchains are required to convert to and from the standard Globally Unique Identifier (GUID) consistently—hereafter referred to as IfcGUID compliance [

5,

26]. Compliance concerns four aspects: existence, format validity, uniqueness, and cross-version stability. If any of these fail, cross-system comparison and reuse devolve into pseudo-comparison of “same thing, different Identifiers (ID)” [

5].

On the consumption side of smart homes, game engines act as real-time 3D platforms that integrate multi-source data such as BIM and IoT for visualization, simulation, and interactive presentation to support collaborative decision-making; Unity is a representative engine widely used in digital-twin integration scenarios [

37]. Game-engine interoperability is another critical point: engine-side identifiers are typically project-internal. For example, Unity writes the asset’s unique Identifier (ID) into a local .meta file; if that file is lost or recreated, a new GUID is generated, which is inherently unsuitable as the minimal cross-platform mutual-recognition key [

27,

28]. It is therefore necessary to bridge engine assets to IfcGUID-22 and to register that mapping, together with its context, in the CDE, so that references remain consistent and replayable along the “IFC → engine assets → audit/reconciliation” chain [

5,

26,

27].

Existing reviews and practice emphasize digital-twin research and evidence on the operations/energy side; integrated mechanisms that combine object-key governance → consumption-side handover → evidencing at the design stage are under-reported. BIM↔engine integration studies focus more on visualization and interaction and less on quantitative, auditable ID-mapping-verification pipelines and measurement conventions [

23,

24,

32]. Accordingly, our entry point is to embed IfcGUID-22 compliance and traceability-oriented governance at the design stage and to close the loop via engine-side handover and cross-system alignment, turning “source-side compliance (IFC/IfcGUID) → consumption-side acceptance (engine/assets) → cross-system reconciliation (CDE/audit)” into executable processes and evidence [

3,

4,

5,

26,

27].

Based on the above, we address two questions:

RQ1 (governance): How can multi-source data be incorporated into a controlled BIM-standard project environment at the design stage and managed with unified, stable object identity across teams, systems, and versions so that they align, compare, and enable accountable traceability—thereby reducing breakage and rework caused by non-standard data? [

3,

4]

RQ2 (engineering): How can a verifiable, low-cost, and transferable process convert consumption-side non-standard data into compliant data streams, create a complete chain of evidence, and support sustained reuse across projects and version evolution? [

5,

26,

27]

To answer these, we build a virtual experimental platform aligned with design-stage data-management requirements for smart homes; freeze data assets; lock environments and execution entry points; and register hashes for key executables/configurations and all inputs/outputs. Using a unified denominator U0, we define and compute four integrity metrics—completeness, validity, uniqueness, and stability—to form the pre-test baseline; we then implement an IfcGUID↔engine bridging and minimal-repair mechanism and perform a same-convention retest with paired reruns, reporting Δ metrics as absolute percentage-point changes with paired counts to avoid denominator drift. This end-to-end, evidence-oriented pipeline is validated in a virtual smart-home setting and is designed to be reproducible within existing toolchains.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Smart-Home Management Requirements

The smart-home market has entered a high-growth, large-scale phase and is now a significant segment of the building sector [

2,

15]. Compared with traditional residences organized around siloed building-services systems (Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning (HVAC), lighting, etc.), smart homes integrate multiple functional clusters; systematic reviews identify five core functions: device management, energy management, healthcare, intelligent interaction, and security [

14,

16]. This shift from “single systems” to “multi-cluster integration” directly expands the objects of building data management—more numerous, more heterogeneous, and more tightly coupled—thereby raising design-stage requirements for data identifiers, naming consistency, and cross-platform mappings [

14,

17,

18]. Accordingly, at the design stage we structure the boundary and inventory of management objects as inputs to subsequent measurement and governance workflows (see

Table 1).

2.2. Design-Stage Applications and Management Status of Smart-Home Digital-Twin Assets

At the design stage of smart homes, digital twins (DT) are increasingly recognized in systematic reviews as an emerging means of management and delivery: by linking design semantics with device logic in a virtual environment, they enable interactive verification and visualization, bringing data governance and scenario checking forward into design while supporting downstream phases [

23]. This study adopts the previously defined management-object inventory and discusses multiple functional clusters—lighting, HVAC, security, energy, and interaction—within a unified framework [

14]. In the design/schematic phase toolchain, real-time game engines (with Unity as a representative) have become common platforms for BIM integration and scenario-driven simulation to support visualization, interaction, and scheme verification; at this stage, DT work primarily simulates owner–scene interactions within design options [

24].

In the smart-home context, design-stage DTs for HVAC remain constrained: much of the building-DT literature concentrates on operations and maintenance (O&M) and relies on operational data and calibration—systematic reviews expressly focus on O&M applications, while American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) guidance notes that calibration typically requires seasonal measured data, which are not available at the design stage [

20,

25].

Authoritative guidance frames smart-home building data management within an ISO 19650-based, life-cycle CDE process: information containers carry unique identifiers and controlled metadata (revision/status/classification) and progress through controlled workflows across planning, design, construction, and O&M; the UK BIM Framework Part C further specifies exchange and container-management requirements for consistent life-cycle delivery and acceptance [

5,

27].

2.3. IfcGUID Generation and Validation Methods

In object-level, traceable building data management, a GUID/UUID is a 128-bit identifier that uniquely identifies objects across systems and time; originating in distributed computing and standardized by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) as UUID (Request for Comments (RFC) 4122)—often called GUID—it provides uniqueness “across space and time” without central registration, laying the foundation for its later role as an object primary key in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) Information Delivery Specification (IDS) exchange [

28]. The AEC domain institutionalizes this via IFC: since IFC 1.0, the base class IfcRoot has carried a GlobalID for independent entities; the standard established the 22-character compressed IfcGloballyUniqueId to convey the underlying UUID’s uniqueness and traceability, making object-level identifiers a hard constraint for model exchange [

21,

22]. This mechanism is published internationally as ISO 16739-1, enabling multi-software exchange and delivery across construction and facility management; accordingly, IfcGUID has become a common institutional arrangement in building-data workflows [

26].

For mainstream generation and validation, practice follows buildingSMART and open-source implementations: convert between a standard UUID and IFC’s 22-character encoding (an IFC-specific Base64 variant), typically using IfcOpenShell (ifcopenshell.guid.compress/expand) for reproducible conversion and batch legality checks (length/charset/reversibility) [

21]. For uniqueness, automatic checks such as “Require Unique IFC GUIDs (Unique in One/All Models)” are applied at single-model and federated-model scales [

29]. For stability, authoring-tool exports enable writing the GUID back to an element parameter (e.g., “Store the IFC GUID in an element parameter after export”) to prevent primary-key drift across repeated exports and to support version tracking in the CDE [

30]. For delivery compliance, requirements such as “must exist, be unique, and be reversible” are encoded as machine-readable information requirements and checked automatically with IDS v1.0 (a buildingSMART final standard), embedding “generate–validate–compliance check–archive” in the CDE workflow from Work in Progress (WIP) → Shared → Published [

33].

For subsequent pre-test/post-test reuse, the compliance basis, derived rules, and indicators are summarized in the following table.

2.4. Research Gaps

Recent systematic reviews concur that digital-twin (DT) research for smart buildings still centers on construction and operations/maintenance, with limited evidence on design-stage data management. Empirical work on interactive visualization is mostly evaluated for communication/collaboration and decision support, seldom unifying “visualization experience” with “data governance (identification, mapping, checking)” in a single workflow, and lacking unified quantitative metrics. This points to a shared view: executable compliance gates should be moved upfront to design to pre-empt downstream data breakage [

32,

33].

At the standards-and-implementation level, ISO 19650/UK BIM Framework require unique identifiers for information containers in the CDE, with status/revision/classification metadata and audit trails for traceable governance across planning–design–construction–O&M; however, industry reports persistent rollout difficulties and inconsistent processes, which increase rework and coordination costs. The gap is how to translate these textual requirements into verifiable registrations and logs to form a cross-phase, consistent chain of delivery evidence [

3,

4].

For semantic interoperability, prototypes and tools for IFC ↔ BACnet/Building Management System (BMS) use Information Delivery Manual (IDM)/ Model View Definition (MVD) methods to define stable minimal subsets for cross-platform exchange; yet many studies note unresolved gaps in BMS–IFC integration, requiring stable unique identifiers and standardized subsets to sustain DT construction. In the smart-home endpoint ecosystem, Matter 1.2 already covers cluster-level semantics for devices such as door locks and thermostats, but systematic mappings to IFC (e.g., Building Controls Domain) and a transferable pipeline remain to be validated [

36].

3. Materials and Methods

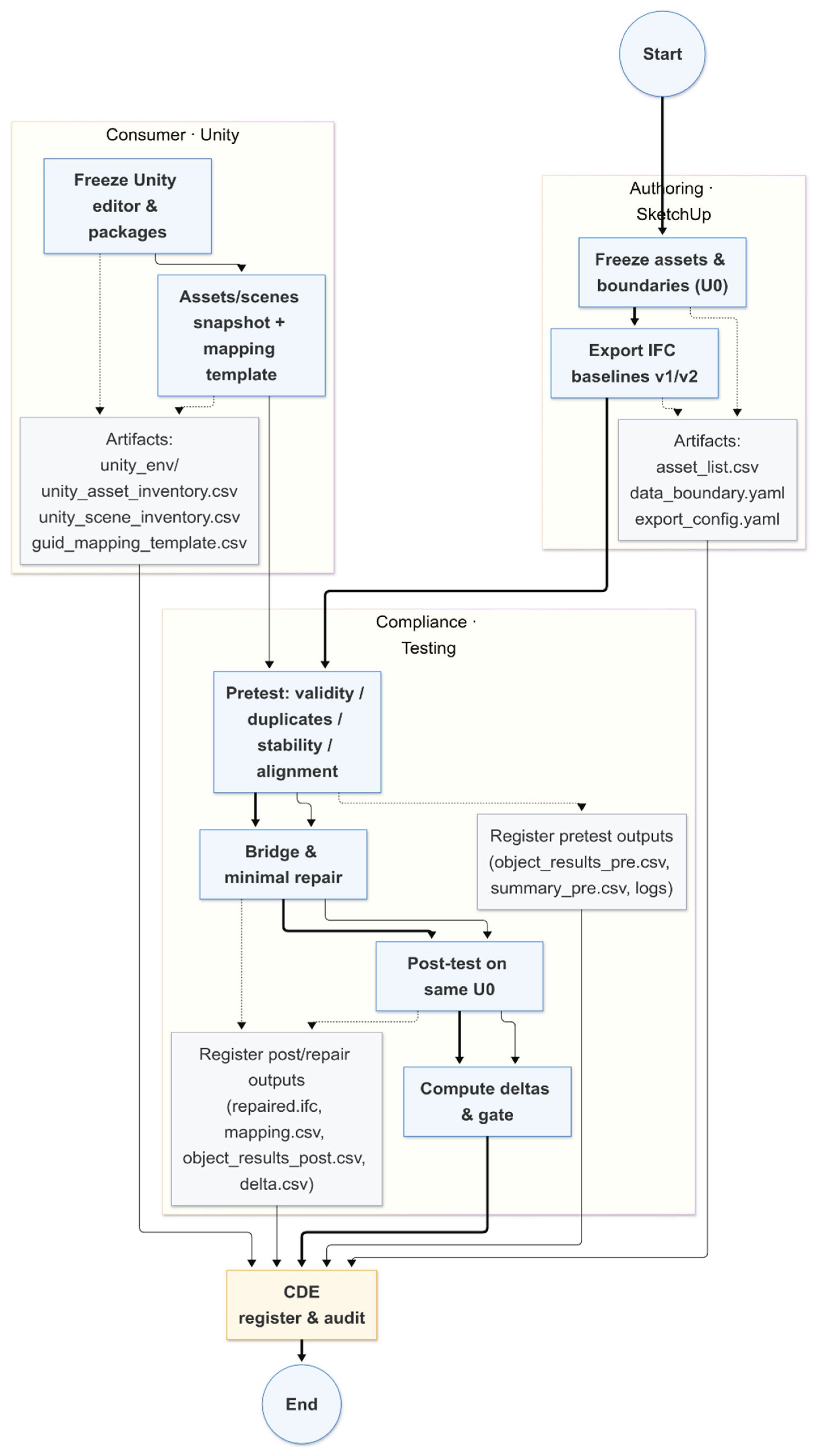

Methodologically, we first construct virtual digital-twin assets as the study object in line with smart-home building data management requirements, unifying and freezing coordinates, units, and naming within the model. Using a single, uniform export strategy, we generate IFC and enable IfcGUID-22 write-back so that IFC becomes the sole data source and object-level primary keys remain stable. We then freeze data assets and the execution environment, lock execution entry points, and register paths, timestamps, and checksums in a controlled information environment to fix measurement conventions and the object scope. Next, under the unified denominator U

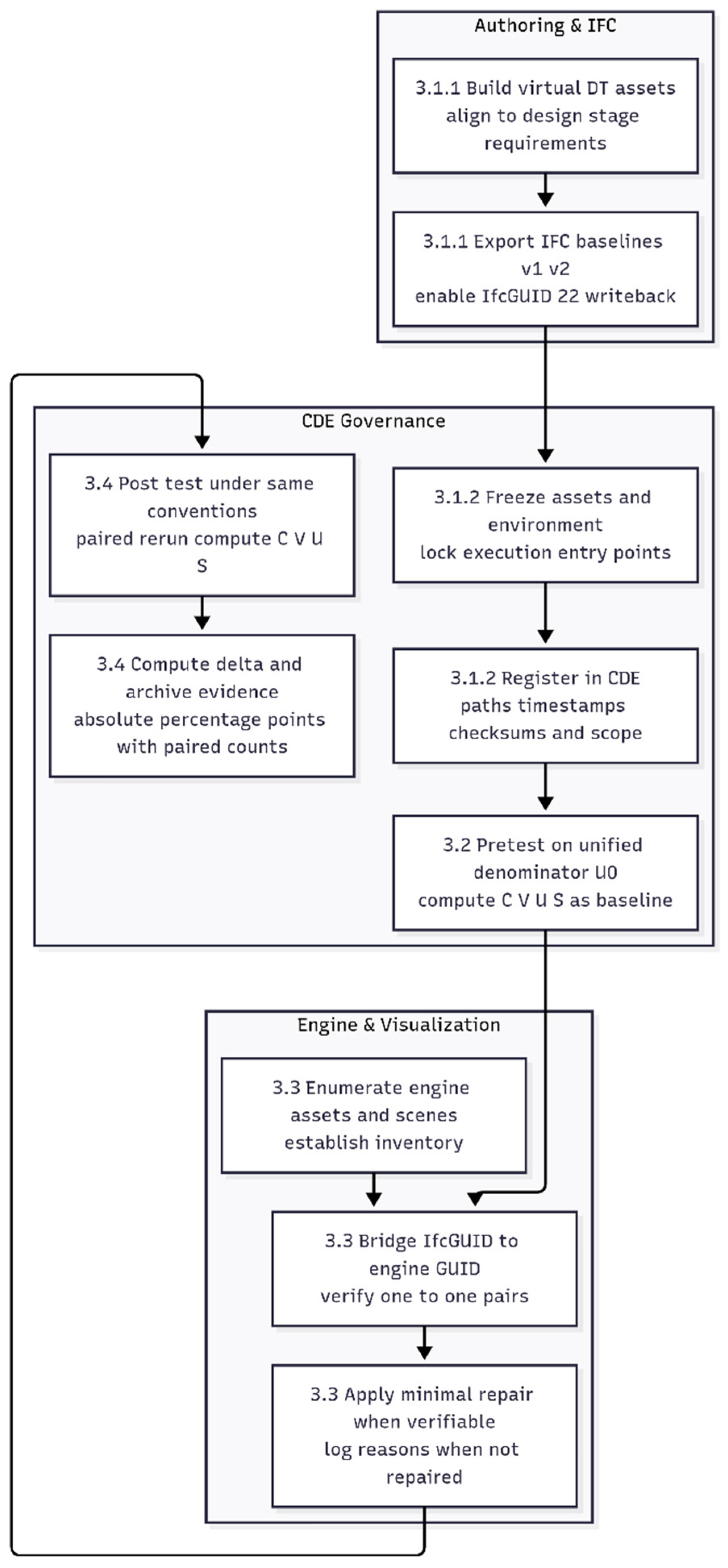

0, we conduct the pre-test, checking each component’s IfcGUID for existence, format validity, uniqueness, and cross-version stability to establish the baseline. Following a small-step, verifiable principle, we implement bridging and minimal repair: we establish a one-to-one mapping between IfcGUID and the engine-side GUID, automatically repairing only when a unique and verifiable repair path exists and otherwise logging reasons without altering the source element. Finally, under the same conventions, we perform the post-test with a read-only paired rerun and report differences as absolute percentage-point Δ with paired counts, completing evidence archiving and traceable registration. The research framework is shown in

Figure 1.

3.1. Experimental Platform Setup and Metric Definition

This section explains how we built a reproducible experimental platform and fixed the measurement conventions. By locking software versions and data entry points, results are affected only by the method, not by environmental drift. We then formalize the four metrics—completeness (C), validity (V), uniqueness (U), and stability (S)—under a unified denominator, ensuring comparability and auditability across stages and operators. The aim is to eliminate two common uncertainties—platform inconsistency and metric non-uniformity—so that subsequent conclusions focus on method effectiveness rather than implementation details.

3.1.1. Scope Definition and Platform Construction

To support comparable IfcGUID measurement and retesting, the platform is built in the order of requirements, scoping, layout design, modeling, and digital-twin assets, keeping each step feasible and reproducible.

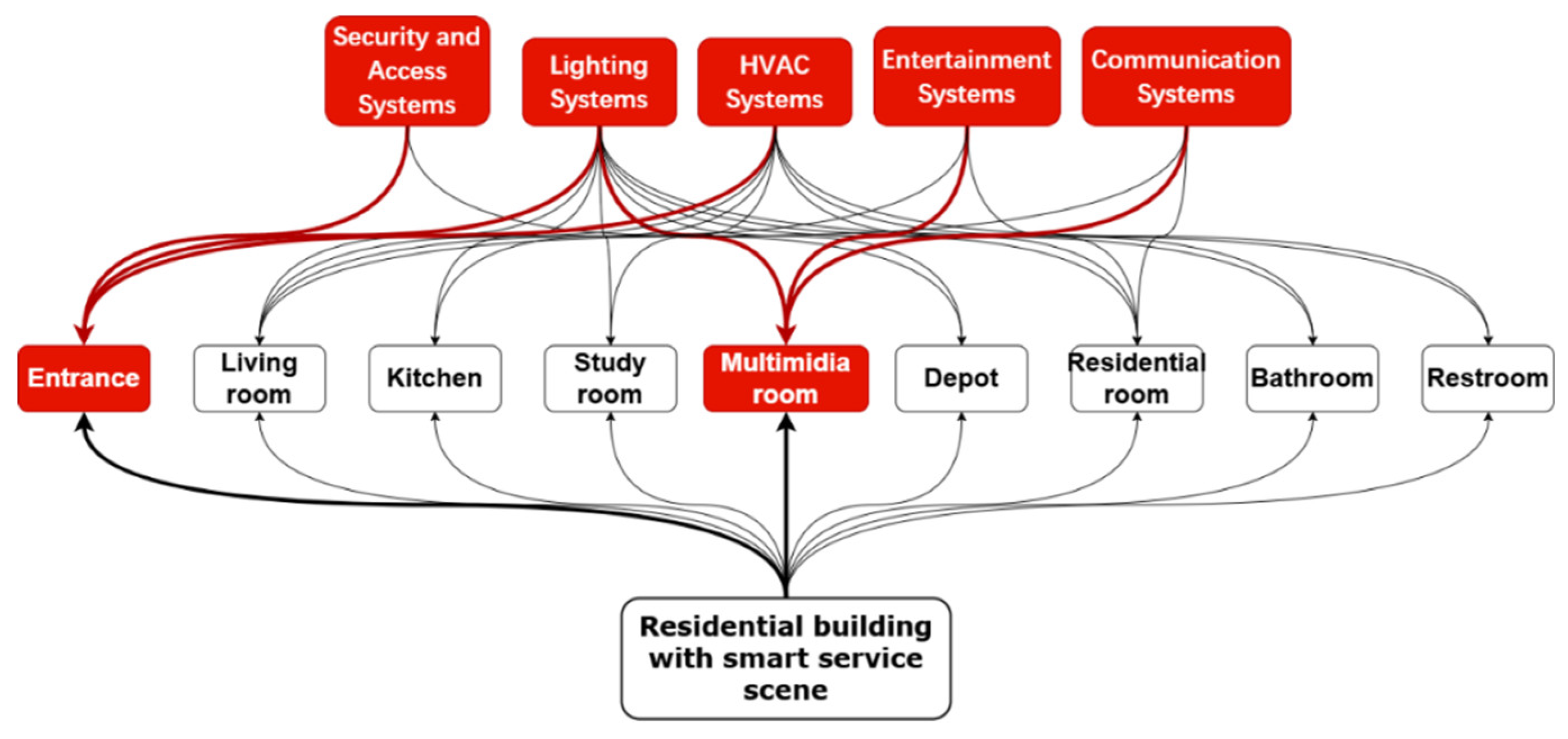

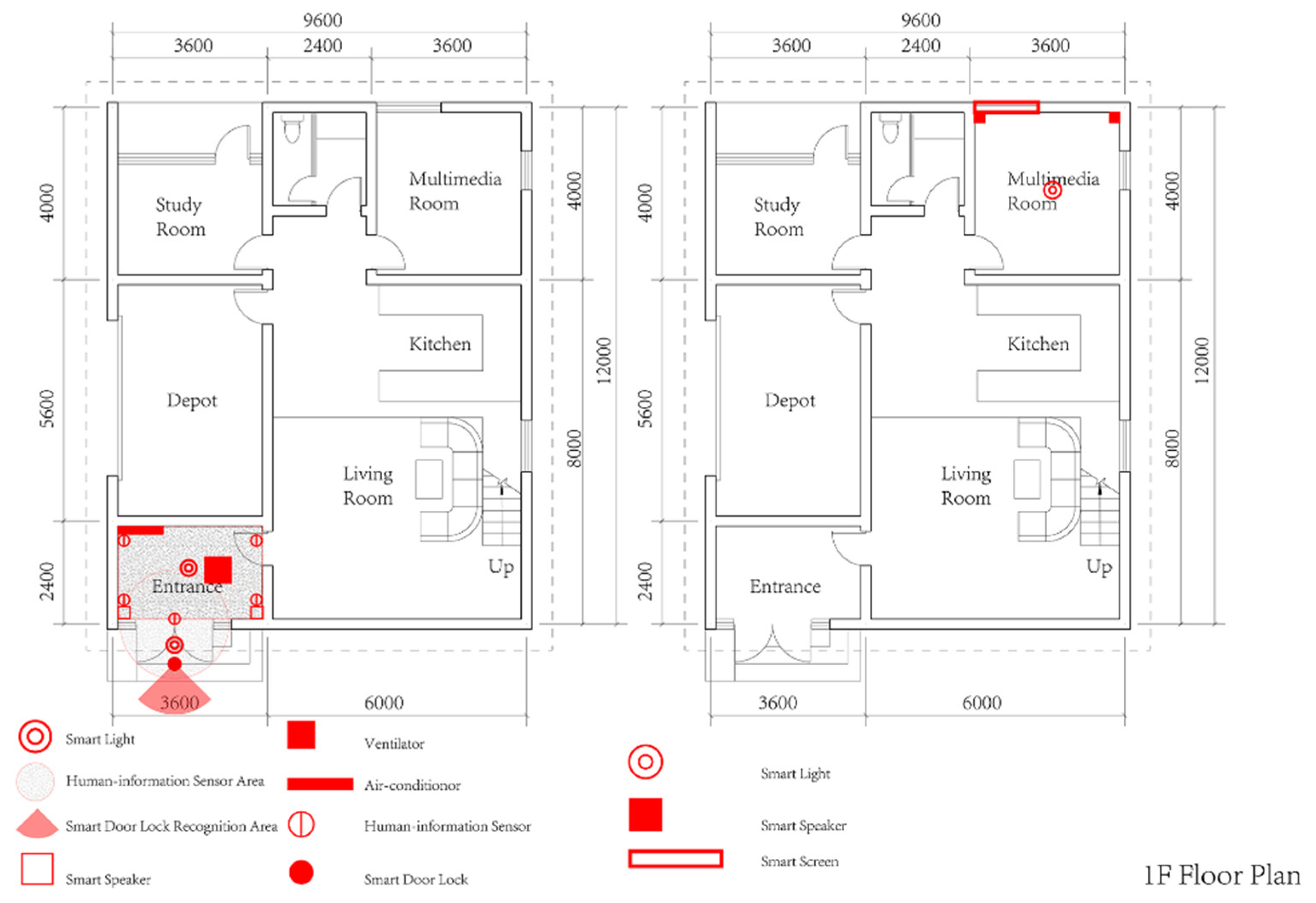

First, define the requirements. Based on the interaction tasks sampled in

Section 2, we construct a virtual smart-home scenario that can be closed-loop verified at the design stage. The platform focuses on four systems—security and access, lighting, entertainment, and communication—to ensure coverage of interactions and engineering feasibility. HVAC, which depends more on operational IoT data and control strategies, is excluded at this stage.

Next, fix the scope. To avoid denominator drift between pre-test and post-test, objects are partitioned into U

0, which enters the measurement and repair loop, and the extended set U

+ used for coverage statistics. Both are fixed through an asset list and boundary file in the Common Data Environment (CDE): E:\SHDT25_CDE\asset_list.csv and E:\SHDT25_CDE\information_standard\data_boundary.yaml.

Section 3.3 and 3.4 reuse the same conventions.

After completing the floor layout and system placement, we select two representative spaces: the Entrance and the Multimedia Room. The former covers access control, security, and lighting with presence-based linkage; the latter covers audio-visual, lighting, and communication linkages. Together they cover the main interaction combinations listed in

Table 2, while keeping scale and complexity within implementable bounds.

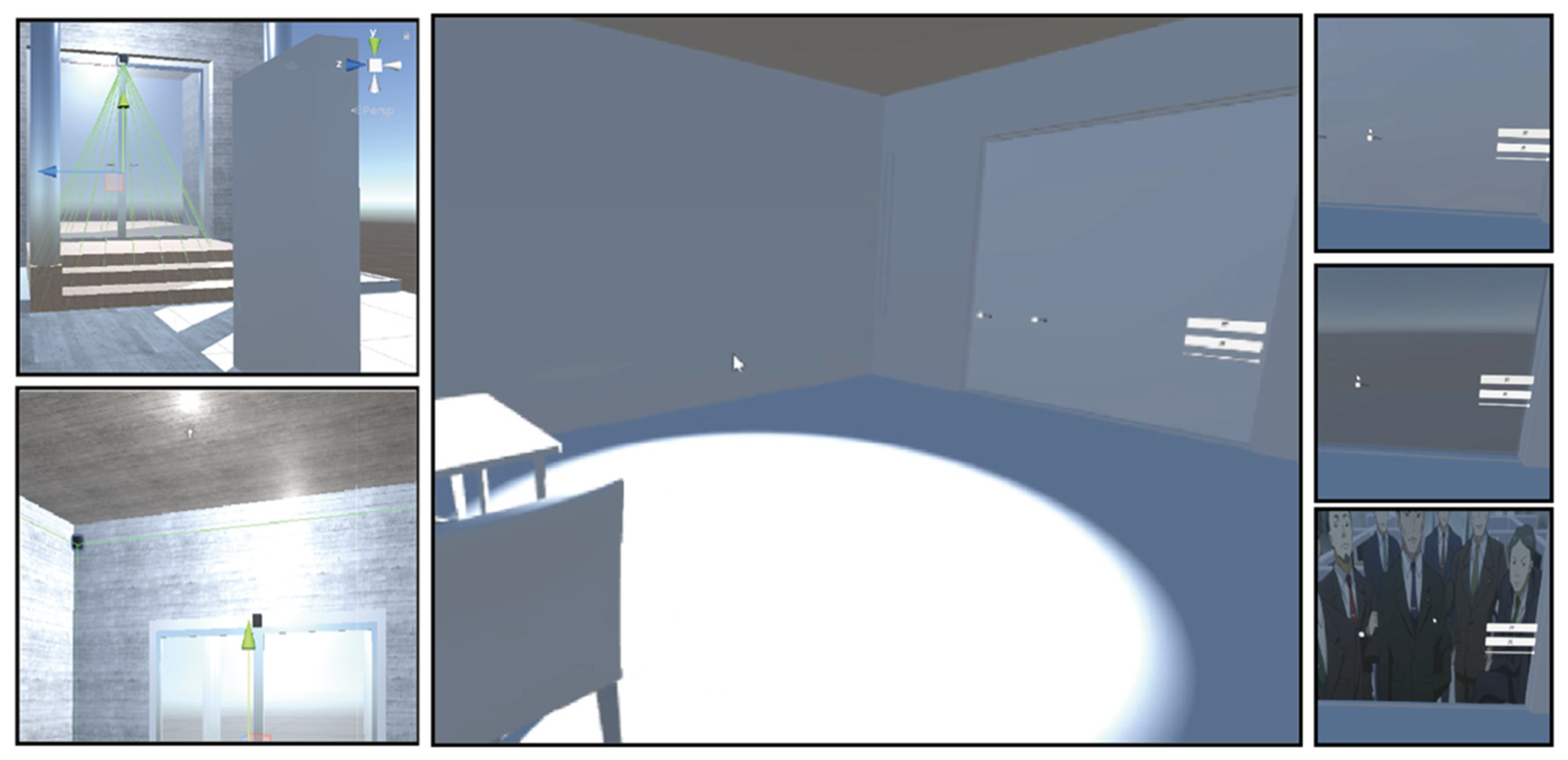

Figure 2 illustrates the selection of two typical spaces—Entrance and Multimedia Room—as the testbed covering access, lighting, AV and communication interactions.

Figure 3 shows the system design for the typical spaces in our smart-dwelling virtual experiment platform.

Finally, we built the model and the digital-twin assets. After modeling in SketchUp with unified naming and hierarchy, we export IFC as the sole data source; in Unity, we build the corresponding interactive scenes and object mappings to form the runtime environment for measurement and retesting. Object references are registered in the Common Data Environment (CDE) and reused under the same conventions in subsequent stages. See

Appendix B (B.1a) for the CDE directory map and (B.1) for registry roles.

Figure 4&5 presents the digital-twin live demonstration scene used to validate interactive behaviors and provenance logging under the frozen environment.

Figure 5.

Digital-twin live demonstration scene.

Figure 5.

Digital-twin live demonstration scene.

3.1.2. Export Pipeline and Asset Freezing

To ensure comparability and auditability, we perform a one-time freeze of digital-twin assets at the design stage: project coordinates, units, and naming are unified and locked; an asset inventory and data boundary are output to form the evaluation set U

0. The export pipeline is fixed as SketchUp → IFC with a consistent strategy, making IFC the sole data source. Under identical environment and configuration, two baselines (v1/v2) are exported for subsequent GlobalId stability checks. All write operations occur only within tool-generated containers, leaving the original project unchanged; in a single transaction, we register the baselines, inventories, environment snapshots, and checksums to support reruns and audits (see Supplementary S2–S4).

Table 3 summarizes the key baselines and locks (coordinates/units, naming/hierarchy, export channel, environment snapshot, and CDE register) and where the evidence is stored. Key baselines and locks are summarized in

Table 4. Full environment pins and checksums are listed in

Appendix A (

Table A1), with controlled inputs in A.2–A.3.

Table 4.

Pretest summary on

Table 4.

Pretest summary on

| Metric |

Value |

Objects_in_U0 |

Duplicate_members |

Aligned_with_Unity_rate |

S_ifc |

Notes |

| R1_Completeness |

0.052439 |

820 |

1 |

0.000000 |

1.000000 |

Denominator U0 = 820 |

| R2_Validity |

0.052439 |

— |

— |

— |

1.000000 |

— |

| R3_Uniqueness |

0.051220 |

— |

1 |

— |

1.000000 |

— |

| R4_Stability |

0.052439 |

— |

— |

— |

1.000000 |

Measured between v1 and v2 |

| BRR (bridge recognition rate) |

0.000000 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

recognized_pairs = 0 of M = 43 |

| DR (break rate) |

1.000000 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

break_missingUnity = 43 |

|

A

|

| IfcClass |

N_in_M |

R1_Completeness |

R2_Validity |

R3_Uniqueness |

R4_Stability |

Aligned_with_Unity_rate |

Duplicate_members |

| IfcWall |

16 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0.000000 |

0 |

| IfcDoor |

5 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0.000000 |

0 |

| IfcFurnishingElement |

5 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0.000000 |

0 |

| IfcWindow |

4 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0.000000 |

0 |

| IfcRoof |

3 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0.000000 |

0 |

| IfcBeam |

2 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0.000000 |

0 |

| IfcSlab |

2 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0.000000 |

0 |

| IfcBuilding |

1 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0.000000 |

0 |

| IfcBuildingStorey |

1 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0.000000 |

0 |

| IfcProject |

1 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0.000000 |

0 |

| IfcPropertySet |

1 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0.000000 |

1.000000 |

0.000000 |

1 |

| IfcSite |

1 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0.000000 |

0 |

| IfcStair |

1 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0.000000 |

0 |

|

B Issue composition in pretest. |

| Issue_category |

Count |

Share_in_issues |

Share_in_U0 |

| Illegal_length_22char |

0 |

0.000000 |

0.000000 |

| Illegal_characters |

0 |

0.000000 |

0.000000 |

| Duplicate_cluster_members |

1 |

0.022727 |

0.001220 |

| Cross_version_unstable |

0 |

0.000000 |

0.000000 |

| Not_aligned_to_Unity_lists |

43 |

0.977273 |

0.052439 |

| Other |

0 |

0.000000 |

0.000000 |

3.1.3. Metric Definitions and Statistics

To obtain comparable, reproducible conclusions in the pre-test and post-test, once the frozen assets are in place we define the four authoritative metrics used in this study—completeness (C), validity (V), uniqueness (U), and stability (S)—and specify their mathematical forms and statistical conventions, together with the notation and denominators for two interoperability summaries (Bridge Recognition Rate (BRR), Disconnect Rate (DR)).

Time index 。

Let the GlobalId sets of the two baselines v1 and v2 at time t be;their union is .

On the Unity side, assets come from the asset inventory and the scene inventory, denoted 、, their union is .

The bridging mapping is (the explicit set of ifc_guid ↔ unity_guid pairs), with size .

The hit set consists of Unity asset GUIDs that can be resolved to a project-relative path; define .

On the Unity3D side, assets come from the asset inventory and the scene inventory, denoted respectively as 、,their union is .

R1 Completeness (C)

Meaning: proportion of objects in

I with a resolvable GlobalId.

R2 Validity (V)

Meaning: proportion of objects in I whose GlobalId is both a 22-character exchange string and round-trip reversible.

R3 Uniqueness (U)

Meaning: proportion of objects in I whose GlobalId does not belong to any duplicate cluster (after normalizing case and separators).

R4 Stability (S): same-config dual baselines

Meaning: retention of the intersection of GlobalIds across two repeated-export baselines under identical settings. We report on the unified denominator and list the IFC-side comparator in parallel.

Interoperability summaries

BRR (recognized pair ratio): share of recognized pairs in the mapping.

DR (missing-in-Unity ratio): share of mapping entries where the Unity side is missing.

Absolute percentage-point change:

Formal metric statements and invariants are consolidated in

Appendix C (C.3).

3.2. Pre-Test (Baseline)

This section builds a baseline measurement without altering source data: under the unified denominator U0, we compute C/V/U/S and fix outputs through the workflow “extract → validate → align → measure → summarize → register,” for subsequent pre–post comparison and auditable reproduction.

Here we establish an IfcGUID-compliance baseline without repair. Within the object scope frozen in §3.1 and the controlled export pipeline, we generate two baselines v1 and v2 and, under the same denominator, compute the four authoritative metrics C, V, U, S, while reporting the IFC-side comparator S_ifc in parallel. The time index comprises pre and post; this section executes pre, and the later post recomputation follows the same conventions.

Execution is strictly read-only. All inputs come from controlled information containers, keeping the statistical denominator, export settings, and runtime environment identical; no writes are made to the IFC or Unity sources. Using Python and IfcOpenShell, we parse IfcRoot.GlobalId, form the 22-character exchange string and verify round-trip reversibility, and identify duplicate clusters to support the uniqueness metric. Based on explicit mapping, we align IFC with Unity to produce an object-level table, then compute summary-level metrics and register input fingerprints and output indices to ensure that paired reruns are auditable.

3.2.2. Script Design: pretest_compute_metrics_U0_ifc.py

The pipeline follows five steps: Detect, Normalize, Align, Measure, Register.

Detect. Read the two baselines and controlled lists (asset list, scene list, object boundary); parse IfcRoot.GlobalId, verify the 22-character exchange string via round-trip checks, identify invalid values and duplicate clusters, and output object-level flags.

Normalize. Standardize representations of IfcGUID and engine-side GUIDs (case, separators, whitespace), ensuring consistent set operations and matching; fix the unified-denominator conventions (I, U, H, , N).

Align. Perform explicit ifc_guid → unity_guid alignment to obtain the hit set H; verify resource existence and path resolvability; generate the object-level alignment table and assign hit/missing reasons for later BRR/DR interpretation.

Measure. Compute C/V/U/S on the unified denominator N and report in parallel; calculations are read-only and do not modify the IFC or Unity sources.

Register. Register input/output manifests and hashes, append timestamps, operator, and run configuration, update the CDE index, and output object-level tables and summary reports to support paired reruns and auditable reproduction.

A reproducibility checklist is provided in

Appendix A (A.3); field semantics are summarized in

Appendix B (B.3).

Acceptance gates and IDS excerpts referenced by this step are summarized in

Appendix C (

Table A6).

Figure 6 outlines the pre-test metric pipeline (pretest_compute_metrics_U0_ifc.py: Detect → Normalize → Align → Measure → Register).

3.2.3. Script Execution and Outputs

The runtime is located in the CDE Published layer under tools_pretest, invoked via the project’s bundled virtual interpreter. Inputs uniformly point to baselines, unity_lists, unity_env, and the configuration snapshot. The script performs extract, validate, align, measure, summarize, and register in a single run. Outputs include object-level and summary-level artifacts; the core files are baseline_guid_report_stage.csv, baseline_summary_stage.csv, interop_summary_stage.csv, coverage_summary_stage.csv, dr_summary_stage.csv, and provenance_summary_stage.csv.

3.3. Authoring and Running the IfcGUID Self-Test and Minimal-Repair Script

Under the unchanged pre-test conventions, we design a self-check and batch-repair workflow. The objective is to keep IfcRoot.GlobalId stable, complete the mapping keys and consistency metadata, and produce auditable repair artifacts and mapping lists, thereby supplying like-for-like inputs for the subsequent post-test.

3.3.1. Pre-Test Findings

Breakpoints concentrate at the consumption-side key layer. The IFC-side IfcGUID shows high consistency and stability; link failures mainly occur in three cases: no explicit mapping, missing Unity resources, and unresolved paths. A small number of nonstandard encodings and duplicate clusters also appear and must be flagged and normalized without changing the object primary key. Accordingly, this section targets four repair goals: (i) unify the exchange representation of IfcGUID, (ii) detect and label duplicate clusters, (iii) establish a round-trip-verifiable IFC↔Unity bridging key, and (iv) output complete repair logs and mapping lists with registration.

3.3.2. Script Design: pipeline_ifc_unity_bridge.py

The pipeline adopts five steps: Detect, Normalize, Bridge, Writeback, Register.

Detect. Read baselines and controlled lists; perform round-trip reversibility checks on IfcRoot.GlobalId; identify duplicate clusters and invalid values; output object-level annotations.

Normalize. Generate a fixed exchange string; normalize case and whitespace to ensure consistent matching.

Bridge. Align ifc_guid with unity_guid; verify resource existence and path resolvability; assign hit flags and disconnection reasons; generate a mapping list using the header of guid_mapping_template.csv.

Writeback. Write a custom property set into IFC to record bridging keys and derived fields; keep IfcRoot.GlobalId unchanged; output the repaired IFC and the external mapping list.

Register. Register input/output manifests and hashes; append timestamp, operator, and version; produce an auditable chain of evidence and paired-rerun index.

Figure 7 details the bridging and minimal-repair pipeline that establishes a one-to-one IfcGUID ↔ engine GUID mapping with read-only repairs.

3.3.3. Script Execution and Outputs

Execution is performed in a controlled terminal using the project-bundled interpreter and fixed configurations; inputs come only from controlled information containers, and the source IFC and Unity projects remain read-only. In a single pass, the script conducts extraction, verification, normalization, bridging, writeback, and registration. Outputs include the repaired IFC, the mapping list, object-level and summary-level repair logs, and registration/validation artifacts. All outputs are uniformly registered with traceable paths, hashes, timestamps, and operator metadata. The subsequent post-test is executed under the same denominator and sampling conventions as the pre-test.

3.4. Retest and Paired Rerun

This section verifies repair effectiveness via “same-condition rerun + pre–post comparison.” We keep the same data scope and the same commands/settings, rerun the full pipeline, and then compare four result types one-to-one—presence/absence, correctness, uniqueness, and cross-version consistency—reporting both counts and proportions. If the rerun outputs match the previous run, the process is stable; if they differ, the divergence can be traced to its source.

Overall, without modifying the IFC/Unity sources, we perform like-for-like recomputation and a paired rerun on the originally frozen assets (pre) and the standardized assets from §3.3 (post), fixing the pre/post versions of the four authoritative metrics and producing immediately verifiable change outputs.

See

Appendix C (C.1–C.3) for pass/fail thresholds, gates, and pairing rules.

3.4.1. Script Design: compute_pre_post_delta.py

The script follows a lightweight pipeline Extract → Validate → Align → Measure → Aggregate → Register. Using the fixed interpreter and the same measurement program, it executes pre and post in sequence, with inputs of the two baselines v1/v2, the controlled Unity inventories, and the explicit mapping. After aligning key domains, it recomputes the four primary metrics on the unified denominator, and produces the interoperability summaries in parallel. It then computes post minus pre deltas and writes paired comparison outputs; finally, it performs registration and verification in a single transaction to ensure rerun comparability and auditable evidence.

Figure 8 shows the compute_pre_post_delta pipeline for same-condition reruns and paired Δ reporting on the unified denominator.

3.4.2. Script Execution and Outputs

The scripts follow a lightweight pipeline of Extract → Validate → Align → Measure → Aggregate → Register. Using a pinned interpreter, execute the pre and post passes sequentially under the same measurement program, with inputs from the two baselines v1 and v2, the controlled Unity inventories, and the explicit mappings. After aligning the key space, recompute the four primary metrics on the unified denominator U0 and produce a side-by-side interoperability summary. Then compute the post minus pre deltas and write the paired artifacts. Finally, complete registration and verification within a single transaction to ensure reruns are comparable and the chain of evidence is auditable.

3.5. Use of Generative AI(GenAI) Tools

During method development and manuscript preparation, the authors used a generative AI tool in a limited way to (i) assist code refactoring and minor bug-fix suggestions for preprocessing scripts, and (ii) translate technical phrases from Chinese to English for terminology harmonization.

Tool used: ChatGPT (GPT-5 Thinking; OpenAI; web app; accessed on 29 September 2025, UTC+8; product page:

https://chatgpt.com/). No passages or figures were drafted de novo by this tool. All code changes were reviewed, tested, and version-controlled by the authors; all text was verified and edited by the authors, who take full responsibility for the content.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Design-Stage Compliance Workflow for IfcGUID-Oriented Digital-Twin Assets

Within a controlled information environment, this study establishes a compliance workflow that treats IfcGUID as the object-level primary key and uses the Common Data Environment (CDE) as the sole carrier of the chain of evidence. From a building data management perspective, it provides BIM/CDE managers, game-engine and visualization teams, and owners/auditors with an executable design-stage pathway to assign object-level unique identifiers and auditable registration to digital-twin assets: implement the ISO 19650/UK BIM Framework requirement for unique identifiers of information containers in the CDE; adopt the 22-character exchange representation of IfcGUID-22 as the cross-system key and bridge to Unity’s unique asset IDs; thereby reducing cross-system reconciliation breaks and rework caused by “bad data,” and restoring traceability and reuse of smart-home digital-twin assets at the design stage.

Workflow details are as follows:

Freezing assets and boundaries. Define the evaluation set U0 and the extended asset set; unify coordinates/units/naming; output the asset inventory and data boundary to fix the denominator and value domain.

Freezing export and consumption pipelines. Take IFC as the sole data source; export two baselines v1/v2 under identical settings (for robustness/channel-variance control); register export_config.yaml and paths/hashes in the CDE. On the consumption side, lock Unity version/dependencies, generate the object library, scene snapshots, and a mapping template, and fix the runtime environment and version control.

Automated compliance checking. Under U0, load v1/v2 and the Unity inventories, and—under the same interpreter—run extract → validate → align → measure → summarize → register; compute the four primary metrics Completeness/Validity/Uniqueness/Stability, and record the bridging recognition rate and disconnection points; the entire process is read-only with respect to models and projects.

Bridging and minimal repair. Normalize Unity identifiers to IfcGUID-22 and verify round-trip reversibility; perform self-checks on the IFC side and, without changing IfcRoot.GlobalId, generate new identifiers for downstream members only where illegality/duplication has a deterministic rule; write out a standardized post-test copy and repair records; persist the bridging detail table to the CDE as post-test inputs.

Self-test closure. With the same interpreter and measurement program—and the same object set and denominator—rerun to obtain Δ (post − pre) for the four metrics and explanatory items, evaluating primary-key stability and channel-variance control.

Evidence archiving. In a single transaction, complete registration/checksums/writes; record relative paths, hashes, timestamps, operator, and stage to ensure that, given the same inputs and program version, the process is auditable and reproducible.

Figure 9 depicts the IfcGUID-oriented standardization workflow that turns consumption-side non-standard data into compliant, auditable data streams.

4.2. Pre-/Post-Test Data Results

4.2.1. Pre-Test Results

Under the unified denominator U0 = 820, we performed read-only extraction, validation, alignment, and aggregation to obtain baseline values for the four primary metrics, and reported the IFC-side comparator S_ifc in parallel. Inputs comprised two IFC baselines (v1/v2) and the Unity asset/scene inventories; outputs included object-level and summary results plus interoperability details, all registered with checksums.

-

Overall summary (U0 scope).

R1 Completeness = 5.24% (C = 0.052439), R2 Validity = 5.24%, R3 Uniqueness = 5.12%, R4 Stability = 5.24%; S_ifc = 1.0.

Within U0, all IFC elements corresponding to the interoperability set M = 43 possessed a valid 22-character exchange representation (N_ifc_valid = 43, N_ifc_invalid = 0), yet model-level uniqueness over U0 was only 5.12%.

-

Interoperability alignment.

recognized_pairs = 0 / 43, recognized_in_scenes = 0, BRR = 0.00, DR (break rate) = 1.00; all 43 breaks had break_reason = missingUnity with no badPath cases.

-

Duplicates.

Within M, one duplicate member was detected (in IfcPropertySet; see the object-level table).

-

By type and by issue

Among the 43 objects in M, main types were IfcWall (16), IfcDoor (5), IfcFurnishingElement (5), IfcWindow (4), etc. For each type within M, R1–R4 = 1.0 (complete, valid, unique, and stable across v1/v2), indicating good “required-field” quality on the IFC side.

Issue composition was dominated by Not_aligned_to_Unity_lists = 43 (97.73% of classified issues; 5.24% of U0); next was Duplicate_cluster_members = 1 (2.27% of classified issues; 0.12% of U0). No illegal length/characters or cross-version instability appeared in the pre-test.

The pre-test reveals a typical breakpoint: although the IFC side (within M) is “present, valid, unique, and stable,” it fails to pair with the Unity asset/scene inventories (BRR = 0, DR = 1), leaving the interoperability chain fully broken on the consumption side. This sets the priority for §4.3 Bridging and minimal repair: first resolve Unity-side mapping/recognition, then address the isolated duplicate member.

Controlled inputs and hash proofs are listed in

Appendix A (A.2).

4.2.2. Post-Test Results

Under the same denominator U0 and the same interpreter and rules as the pre-test, we recompute the four primary metrics, keeping IFC as the sole data source and maintaining read-only constraints. Relative to the pre-test, the post-test enables upgraded bridging and probes on the interoperability side, expanding the enumeration/recording of consumption-side object pairs and introducing finer recognition/break statistics and provenance/attribution outputs. This yields a more complete interoperability view without changing the definitions or conventions of R1 Completeness, R2 Validity, R3 Uniqueness, R4 Stability, ensuring direct comparability with the pre-test.

Coverage of the interoperability set is expanded from the pre-test’s small subset to a full scan of consumption-side object pairs. Newly recorded are the bridging recognition rate, break rate, recognized-in-scenes count, and total pairs, together with object-level interoperability details, provenance summaries, and a Pareto list of issues. The four primary metrics continue to be reported on the unified denominator U0, while interoperability metrics are reported on the expanded set of object pairs.

On the unified denominator U0 = 820, the post-test metrics are:

R1 Completeness = 1.000000, R2 Validity = 1.000000, R3 Uniqueness = 0.976744, R4 Stability = 1.000000; the parallel IFC-side comparator S_ifc = 1.000000.

On the interoperability side, BRR = 0.998715, total pairs M = 778, recognized pairs = 777, DR = 0.001285, total breaks = 1 (with missingUnity = 1, badPath = 0), and recognized_in_scenes = 18.

Duplicates are reduced to 1 remaining member; illegal length/characters and cross-version instability are 0.

Within the IFC object set I = 43, each type attains 1.000000 on R1, R2, R4. The only type not reaching 1.000000 on R3 is IfcPropertySet (one duplicate member); all other types achieve R3 = 1.000000. The issue set converges to two categories: Not_aligned_to_Unity_lists = 1 and Duplicate_cluster_members = 1; all others are 0.

Without changing conventions or the denominator, the post-test lifts validity, completeness, and stability to full values, and narrows residual uniqueness issues to a single member. The interoperability chain is almost fully restored, with only one remaining consumption-side break and effective scene-level recognition established. These results verify the substantive improvement delivered by the bridging and minimal repair strategy on consumption-side interoperability.

Table 5.

Post-test summary on

Table 5.

Post-test summary on

| Metric |

Value |

Objects_in_U0 |

Duplicate_members |

Aligned_with_Unity_rate |

S_ifc |

Notes |

| R1_Completeness |

1.000000 |

820 |

1 |

0.998715 |

1.000000 |

Denominator U0 = 820 |

| R2_Validity |

1.000000 |

— |

— |

— |

1.000000 |

— |

| R3_Uniqueness |

0.976744 |

— |

1 |

— |

1.000000 |

— |

| R4_Stability |

1.000000 |

— |

— |

— |

1.000000 |

Measured between v1 and v2 |

| BRR |

0.998715 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

recognized_pairs = 777 of M = 778 |

| DR |

0.001285 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

break_missingUnity = 1, break_badPath = 0 |

| recognized_in_scenes |

18 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

interoperability view on expanded pair set |

|

A Post-test by IFC class on I |

| IfcClass |

N_in_I |

R1_Completeness |

R2_Validity |

R3_Uniqueness |

R4_Stability |

Duplicate_members |

| IfcWall |

16 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0 |

| IfcFurnishingElement |

5 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0 |

| IfcDoor |

5 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0 |

| IfcWindow |

4 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0 |

| IfcRoof |

3 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0 |

| IfcBeam |

2 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0 |

| IfcSlab |

2 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0 |

| IfcPropertySet |

1 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0.000000 |

1.000000 |

1 |

| IfcSite |

1 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0 |

| IfcStair |

1 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0 |

| IfcBuilding |

1 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0 |

| IfcBuildingStorey |

1 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0 |

| IfcProject |

1 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0 |

|

B Issue composition in post-test |

| Issue_category |

Count |

Share_in_issues |

Share_in_U0 |

| Illegal_length_22char |

0 |

0.000000 |

0.000000 |

| Illegal_characters |

0 |

0.000000 |

0.000000 |

| Duplicate_cluster_members |

1 |

0.500000 |

0.001220 |

| Cross_version_unstable |

0 |

0.000000 |

0.000000 |

| Not_aligned_to_Unity_lists |

1 |

0.500000 |

0.001220 |

| Other |

0 |

0.000000 |

0.000000 |

4.2.3. Change Metrics and Pass/Fail Determination

Under the same conventions and denominator as the pre-test (definitions and rules for the four primary metrics unchanged), we summarize post vs. pre deltas. All four primary metrics—R1 Completeness, R2 Validity, R3 Uniqueness, R4 Stability—increase markedly:

R1/R2/R4 absolute gains are +0.947561 (post − pre, likewise below); R3 gains +0.925524. Interoperability indicators also improve substantially: recognized pairs rise from 0 to 777 (scene recognitions to 18), while total breaks fall from 43 to 1 (missingUnity from 43 to 1, badPath remains 0).

Table 6 reports pre/post/Δ for the four primary metrics;

Table 7 summarizes interoperability changes.

Figure 4-6 visualizes absolute gains for the four metrics (bar chart). A formal pass/fail check (e.g., thresholds C/V/S = 1.00, U ≥ 0.95, BRR ≥ 0.95, DR ≤ 0.05) can be annotated directly in

Table 6 and

Table 7; in this run, post-test values meet these stringent gates, with uniqueness not reaching 1.00 only due to one historical duplicate, yet still exceeding common thresholds.

Under the unified denominator, the workflow lifts completeness, validity, and stability to 1.00, and drives uniqueness close to 1.00 (with only one residual duplicate). Interoperability improves from BRR = 0 / DR = 1 to approximately BRR ≈ 1 / DR ≈ 0, leaving only one explainable breakpoint.

Table 8.

Delta of main metrics (post − pre).

Table 8.

Delta of main metrics (post − pre).

| Metric |

Delta_abs |

| R1_Completeness |

0.947561 |

| R2_Validity |

0.947561 |

| R3_Uniqueness |

0.925524 |

| R4_Stability |

0.947561 |

4.3. Improvement Results

From a building data management perspective, we bring design-stage digital-twin assets into a controlled CDE, using consistent “container identifiers + provenance” to support version reconciliation and evidence archiving, thereby forming a traceable, rerunnable, and auditable chain. This yields concrete, verifiable benefits for different roles: BIM/CDE managers achieve closed-loop governance of object primary keys at the design stage; engine/visualization teams use IfcGUID-22 as the minimal mutually recognized key to stably map Unity asset identifiers to object identity, enabling cross-system consistent referencing and replay; owners/auditors can compare pre/post under the same conventions, with mapping details, baselines, and logs together constituting a verifiable registration chain that markedly reduces cross-system breaks and rework caused by “bad data.”

Under the same denominator U

0 = 820, rules, and interpreter as the pre-test, we compare post (after “bridging + minimal repair”) against pre item by item. Among the four primary metrics, Completeness, Validity, Stability (R1/R2/R4) rise from about 0.05 to 1.00; Uniqueness (R3) reaches 0.976744, leaving only one historical duplicate (see

Table 4-4). The interoperability chain changes from fully broken to nearly fully connected: BRR increases from 0.000000 to 0.998715 (recognized pairs 777/778), while DR drops from 1.000000 to 0.001285 (only 1 missingUnity, 0 badPath; see

Table 4-5), and scene-level recognition is established for the first time (18 items; see

Table 4-6). Note that the post-test enables upgraded probes on the consumption side, expanding the enumeration of object pairs from |M| = 43 to |M| = 778; however, the four primary metrics are always computed on the same U

0, ensuring direct comparability with the pre-test (see

Table 6, “conventions” note).

Taken together, the evidence shows: when Unity is the consumption side, once its asset identifiers are stably bridged to IfcGUID-22 and the chain of evidence is registered in the CDE, design-stage digital-twin assets can be transformed into compliant data streams that are comparable, traceable, and replayable (see

Table 7). The main pre-test breakpoint stemmed from misalignment with Unity inventories, indicating that without bridging and a templated mapping, even complete IFC-side primary keys are hard for the consumption side to recognize as “the same object.” In the post-test, by freezing export settings and preserving the original GlobalId, cross-version consistency reaches 1.00, making the interpretation “version differences = entity changes” valid and removing ambiguity sources in differencing (see

Table 6, “Stability”). Residual issues on Uniqueness have converged to a minimal set of historical duplicates, which can be further reduced in the “minimal repair” step (see the duplicate-cluster detail link associated with

Table 6).

4.4. Research Comparison

By research object and stage, existing reviews and empirical work largely place digital-twin (DT) emphasis on O&M/energy scenarios: for example, Buildings systematic reviews and Energy Informatics assessments summarize major applications as operational monitoring, anomaly detection, energy optimization, and predictive maintenance, with relatively sparse design-stage evidence [

20,

32]. In contrast, this study targets design-stage object-level primary-key governance and traceable registration: we do not address operational control or energy strategies, but resolve object-identifier consistency and cross-platform traceability along the modeling/export/consumption chain (under U

0, with pre–post and bridging statistics).

By task focus in BIM–game engine integration, prior work centers on visualization/interaction/training; typical studies emphasize geometry/material conversion, real-time rendering, and user experience improvements, but seldom propose a verifiable workflow of “object primary-key governance → stable mapping → provenance logging” as an auditable process [

8,

24]. Recent reviews also note that current BIM×engine contributions cluster around visualization, immersive applications, and process integration challenges, while data consistency and identifier persistence remain difficult [

24]. By comparison, we carry IfcGUID-22 as the minimal mutually recognized key through the export side (IFC) and the consumption side (Unity), and provide comparable evidence via read-only pre/post reruns (C/V/U/S and BRR/DR).

By data quality and delivery, Facility Management (FM)/delivery lines (e.g., COBie and FM-BIM) stress list-based constraints on completeness/consistency and Quality Control (QC) processes to provide usable data at handover [

11,

18]. However, these paths typically pivot on as-built/handover time points and pay limited attention to design-stage object-level primary-key compliance, cross-version stability, and engine-side recognizability. Our contribution is to front-load primary-key governance into executable artifacts at the design stage (a six-step workflow), and to form an auditable, replayable chain of evidence with the unified denominator U

0 and pre/post Δ.

By problem evidence and engineering pain points, long-standing issues in the ecosystem include IfcGUID loss/duplication/cross-tool inconsistency (e.g., missing and duplicate cases in Revit import/export; bSI forum discussions on cross-platform GUID stability), which directly break cross-system reconciliation and traceability [

22,

30]. Unlike these, our work not only quantifies Completeness/Validity/Uniqueness/Stability for IfcGUID, but also explicitly addresses the ambiguity “engine-internal ID change ≠ object change” via a stable mapping from Unity .meta unique IDs to IfcGUID-22, and writes mapping details plus baselines/logs to the CDE, turning the “do it right” conditions into a reusable minimal constraint [

22,

27,

30].

4.5. Threats to Validity

Statistical. The risk is that “percentages of percentages” may exaggerate changes and that rare residuals can amplify variance. Control: use the unified denominator U0 throughout, report percentage-point differences (post − pre), and provide count metrics at the interoperability layer (e.g., recognized_pairs, break_total). Residual: relative changes on very small bases can still be magnified.

Internal. Threats arise from export/consumption-channel variance, tool upgrades, and unstable object primary keys. Control: freeze modeling and export settings and the Unity environment; execute the post-test as a read-only rerun; preserve GlobalId; adopt IfcGUID-22 as the object key; and fix the IfcOpenShell validation path and commands. Residual: hidden defaults in third-party plug-ins may introduce minor deviations, so we rely on CDE path/checksum registration to support rerun auditing and issue tracing.

Construct. The question is whether the four core metrics (completeness, validity, uniqueness, stability) plus BRR/DR sufficiently represent “IfcGUID-based compliance and consumption-side usability.” Control: treat IfcGUID-22 legality and uniqueness as hard criteria, enforce unique identifiers and metadata governance at the container level, and materialize “compliance” as machine-checkable via ifcopenshell.validate and JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) reports. Residual: deeper semantic consistency is out of scope; therefore we report IFC-side comparators and interoperability details in parallel to reduce over-inference.

External. The context is limited to the design stage and the SketchUp → IFC → Unity toolchain. Control: three reuse premises—IfcGUID-22 compliance; unique identification and checksum registration of information containers in the CDE; and frozen export/consumption channels plus bridging templates. Residual: migration to other engines/toolchains still requires adapted mappings and probes; however, reproducible artifacts and registrations enable independent verification and repeat experiments, aligning with current artifact-review and reproducibility practices [

36].

Provenance artifacts and checksums are provided in

Appendix A; exceptions policy is in

Appendix C (C.4).

5. Conclusion

Targeting the design stage of smart homes, where introducing game engines can yield non-standard data that cause identifier inconsistencies, cross-system reconciliation failures, and blocked traceability, this study proposes and validates a “non-standard to standard” governance workflow. We use IfcGUID-22 as the minimal mutually recognized object-level primary key, perform container unique identification and provenance logging within the CDE, and stably map Unity’s unique asset IDs (.meta) to IfcGUID, thereby turning design-stage digital-twin assets into comparable, traceable, and replayable data streams. Compared with visualization-centric pipelines, our approach adds object-level unique-identifier compliance and an auditable trail, offering directly actionable value for BIM/CDE managers, engine/visualization teams, and owners/auditors [

3,

4,

5,

10,

27].

Under unified IFC export and CDE registration, we construct an IFC-only baseline and complete the pre-test; using IfcOpenShell, we machine-check and minimally repair completeness, validity, uniqueness, and stability of IfcGUID; on the Unity side, we lock the bridging template and complete asset-list generation and mapping write-back; finally, with the unified denominator U

0, we run a read-only post-test and comparison. The method operationalizes the ISO 19650/UK BIM Framework requirements for unique identification of information containers together with buildingSMART/IFC’s fixed 22-character IfcGUID-22 as executable gates, and aligns with IDS to support pre-delivery conformance checks [

3,

4,

5,

21,

26,

27,

31].

Empirically, with U0 = 820, completeness, validity, and stability rise from about 5.24% to 100%, uniqueness to 97.67%; on the interoperability side, BRR = 99.87%, DR = 0.13%, with 18 scene-level recognitions. These results indicate substantially improved object-level traceability and compliance, an interoperable chain to Unity as the consumption side, and robust mapping without altering source-model primary keys.

The literature shows DT research is largely O&M/energy-focused (operational monitoring, energy optimization, predictive maintenance), while BIM×game-engine integration remains visualization/interaction-oriented, with data consistency and process coupling commonly cited as challenges [

8,

20,

23,

24,

32]. We front-load governance to the design stage, making “identification—mapping—validation—provenance” an auditable workflow centered on IfcGUID-22, and provide quantitative evidence via pre/post on a unified denominator and bridging statistics, thus addressing the design-stage evidence gap on object-key consistency and cross-platform traceability.

Evidence here comes from a single context (design-stage smart homes), a single export/consumption pipeline (fixed IFC→Unity), and one within-project pre/post recomputation. Although a unified denominator and read-only reruns mitigate internal bias, generalizability remains limited. Our metrics focus on four IfcGUID-anchored core indicators plus interoperability recognition; deeper semantic consistency, cross-toolchain interoperability differences, and quantitative time/cost benefits are not covered, delimiting external inference.

Future work proceeds along three lines: (i) replicate across multiple projects, toolchains, and heterogeneous consumers to test robustness under more complex interoperability; (ii) extend coverage from identifier compliance to semantic compliance, combining ISO 19650 container identification and metadata governance to assess end-to-end gains; (iii) release scripts and data artifacts publicly with persistent identifiers/DOIs to enable independent verification and cross-team reuse, iterating bridging and probes based on replication feedback.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.F.; Methodology, Z.F.; Software, Z.F.; Validation, Z.F., X.T., and Z.S.; Formal analysis, Z.F.; Investigation, Z.F.; Resources, X.T. and Z.S.; Data curation, Z.F.; Writing—original draft, Z.F.; Writing—review & editing, X.T. and Z.S.; Visualization, Z.F.; Supervision, X.T. and Z.S.; Project administration, X.T.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data, scripts, configuration snapshots, and provenance logs supporting this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kanazawa University for helpful discussions and environment support. We acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (GPT-5 Thinking; OpenAI; product page:

https://chatgpt.com/) for the limited assistance described in the Materials and Methods section.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Reproducibility Pack

Appendix A.1. Environment and Version Snapshot

Table A1.

Versions and SHA-256 hashes of key executables and configurations.

Table A1.

Versions and SHA-256 hashes of key executables and configurations.

| component |

version |

path_rel |

sha256 |

timestamp |

| Python |

3.12.7 |

<python> |

|

2025-09-23T18:52:52 |

| CDE register |

|

cde_register.csv |

6cebea79e20d836dbc2bfc2e1c77aa27bda394209dccb852561980eb2fdcbb5f |

2025-09-23T18:52:52 |

| Checksums list |

|

checksums.txt |

7fcb41bf881fe65e2d2c08ae1143bdfd5df1a19e5015c490994dc72cc1133e29 |

2025-09-23T18:52:53 |

Appendix A.2 Configuration Snapshots

Included artifacts de-identified where applicable: export_config.yaml; unity_env/ProjectVersion.txt; Packages/manifest.json; scripts; logs.

Appendix A.3 Reproducibility Checklist

Environment lock verified

Input hashes match baseline

Read-only flags set

IDS rule set loaded

Comparator seeds fixed

Outputs registered to cde_register.csv

checksums.txt updated

Appendix B. CDE Map, Registry and Data Dictionary

Appendix B.1 cde_register.csv Schema

Table A2.

cde_register.csv schema

Table A2.

cde_register.csv schema

| field |

example |

role |

required_by |

remarks |

| rel_path |

02_Published/unity_env/Packages/manifest.json |

POSIX-style relative path from CDE root; primary locator for evidence and assets |

Gate G05_PROVENANCE; audit trail; Appendix B usage |

Must use forward slashes; no drive letters; regex ^(?![A-Za-z]:)[^\\]*$

|

| sha256 |

C31805E4…CBAEA620 |

File content fingerprint for provenance and integrity checking |

Gate G05_PROVENANCE; reproducibility checks; Appendix A/B |

64 hex characters; case-insensitive; recommended lowercase; regex ^[0-9a-fA-F]{64}$

|

| modified_iso |

2025-08-20T16:05:12+08:00 |

Evidence timestamp for the registered artifact |

Audit trail; IDS time semantics; Appendix C.2

|

ISO 8601 with timezone, e.g., YYYY-MM-DDThh:mm:ss±hh:mm; prefer Z or +08:00 |

| category |

evidence |

Normalized top-level class for CDE items |

Appendix B.1a mapping; reporting filters |

Allowed set: evidence, tools, environment, lists, published, temp; lowercase |

| purpose |

provenance |

Functional purpose of the item within the CDE workflow |

Appendix B.1a purpose; audit rationale |

Allowed set: provenance, baseline, script, config, inventory, archive; lowercase |

Appendix B.1a CDE Directory Map — Standardized from Register

Table A3.

a. CDE directory map derived from cde_register.csv.

Table A3.

a. CDE directory map derived from cde_register.csv.

| top_folder |

files |

top_category |

top_purpose |

| 02_Published |

157 |

Published |

Holds publishable artifacts and baselines; the single source for pre-test and post-test comparisons |

| information_standard |

1 |

Published |

Holds publishable artifacts and baselines; the single source for pre-test and post-test comparisons |

| post_inputs |

2 |

Published |

Holds publishable artifacts and baselines; the single source for pre-test and post-test comparisons |

Appendix B.2 checksums.txt Examples

Table A4.

checksums.txt Examples.

Table A4.

checksums.txt Examples.

| sha256 |

file_relpath |

| 8D9096C2DB6B168EF8AA5C7431F83C02F48D6E5AE45777397989DD5F94CEB316 |

02_Published/ProjectX_ARCH_baseline_v1.ifc |

| BB97BF0FE35AB3417734C10C10964ADBC9D11BAD13C5EAC114A3E680654F86DB |

02_Published/ProjectX_ARCH_baseline_v2.ifc |

| 7FC9DEFCD22E8216574FE762382CD12FB51C989DCD863268BD9C144DD47AAAED |

02_Published/export_config.yaml |

| B416B712248801F7895F56CF01272C8C292E8634A15E4AEF40074209A1E81097 |

02_Published/unity_env/ProjectVersion.txt |

| 0B3C3DBAC25875621C37BE55C86C1933F9418CAD302780AABBF481F7E1D36C3A |

02_Published/unity_env/manifest.json |

| 9CF548F8AAF84CDCBB1EDBBD0F2BA2F3AAA25E9645D116B4D520DEFBF95D328C |

02_Published/unity_lists/guid_mapping_template.csv |

| 3B37FB30A08EA105B9E34B0D00949767CF819D0D9DC822EE9D4323A6575B8979 |

02_Published/unity_lists/unity_asset_inventory.csv |

| C33FA05C625B5D0782836FDE823B310163C8815EAE2E08B89596110DDBAB61E9 |

02_Published/unity_lists/unity_scene_inventory.csv |

| 32CB6C78194F1318C965A35618F5C285AE4EB0B92B1D94AEA5D2A0D2FBC8C984 |

asset_list.csv |

| 09828E81D573331871F8F1E321BA1184F4A5C3FA93CB673065D2F07E210B0913 |

information_standard/data_boundary.yaml |

| 65262AAA4332B38F71D8F9B3002EF8FB05F4A963C22ABF96330599728A74EBE4 |

information_standard/guid_rules.ids |

Appendix B.3 Data Dictionary

Field-level definitions for assets, GUID mappings and denominator sets U0 and U+, including allowed values, units and validation rules.

Table A5.

Data dictionary profile observed from cde_register.csv.

Table A5.

Data dictionary profile observed from cde_register.csv.

| field |

inferred_type |

nonnull_pct |

min_len |

max_len |

unique_values |

example |

| rel_path |

string/mixed |

100% |

14.0 |

50.0 |

11 |

information_standard/data_boundary.yaml |

| sha256 |

string/mixed |

100% |

64.0 |

64.0 |

11 |

09828E81D573331871F8F1E321BA1184F4A5C3FA93CB673065D2F07E210B0913 |

Appendix C. Acceptance Gates

Appendix C.1 Gate List and Pass or Fail Criteria

Table A6.

Gate catalog.

| gate_id |

scope |

rule_summary |

evidence_source |

pass_condition |

fail_action |

log_key |

| G01_IFCGUID |

Model IfcRoot |

All IfcRoot instances must have valid 22-char IfcGUID |

bSI IfcGUID guidance; IFC IfcGloballyUniqueId |

0 failures |

reject and re-export |

G01_IFCGUID |

| G02_CONTAINER_NO |

CDE containers and filenames |

Container sequential Number must be 4–6 digits; other fields follow project information standard |

ISO 19650 UK National Annex container naming |

0 failures |

flag and fix then resubmit |

G02_CONT_NO |

| G03_CLASS_LINK |

IfcElement |

Elements reference an approved classification via IfcClassificationReference |

IFC ClassificationReference; project-approved code list |

0 failures |

map to approved code then resubmit |

G03_CLASS |

| G04_UNITS |

Model units |

Quantities and units consistent with project IfcUnitAssignment unique per unit type |

IFC IfcUnitAssignment semantics |

0 failures |

correct unit assignment then resubmit |

G04_UNITS |

| G05_PROVENANCE |

CDE evidence records |

sha256 is 64 hex; timestamp is ISO 8601; path_rel is POSIX-style relative path |

Project CDE provenance Appendix A and B |

0 failures |

fix metadata and re-register |

G05_HASH |

Appendix C.2 IDS Rule Items

GlobalId format IfcRoot: regex ^[0-9A-Za-z$_]{22}$ fixed 22 characters

Container numbering ISO 19650 UK Annex: sequential Number 4–6 digits; other fields from project information standard

Classification linkage: use IfcClassificationReference with ItemReference from the approved code list

Units consistency: quantities must align with project-level IfcUnitAssignment unique per unit type

Provenance metadata: sha256 equals 64 hex; timestamp equals ISO 8601; path_rel equals POSIX-style relative path

Appendix C.3 Metric Definitions and Invariants

Define completeness, validity, uniqueness, stability and coverage over U0 versus U+; specify pre-test and post-test invariants and paired-rerun matching rules.

Appendix C.4 Exceptions and Minimal Repair

Enumerate auto-fixable cases with verifiable uniqueness; for non-unique or unverifiable cases record reasons without altering sources.

References

- Basarir-Ozel, B.; Turker, H.B.; Nasir, V.A. Identifying the Key Drivers and Barriers of Smart Home Adoption: A Thematic Analysis from the Business Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9053. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Islam, M.; Shahriyar, F.; Islam, S.; Zaman, H.U.; Hasan, M. Smart Home System: A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering 2023, 2023, 7616683. [CrossRef]

- ISO. ISO 19650-2:2018 – Organization and Digitization of Information about Buildings and Civil Engineering Works, including BIM—Information Management Using BIM—Part 2: Delivery Phase of the Assets. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/68080.html (accessed on 2025-08-01).

- UK BIM Framework. Guidance Part C: Facilitating the Common Data Environment (Workflow and Technical Solutions), Edition 1; September 2020. Available online: https://ukbimframework.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Guidance-Part-C_Facilitating-the-common-data-environment-workflow-and-technical-solutions_Edition-1.pdf (accessed on 2025-08-01).

- buildingSMART International. IfcGloballyUniqueId—IFC4.3.2.0 Documentation. Available online: https://standards.buildingsmart.org/IFC/RELEASE/IFC4_3/HTML/lexical/IfcGloballyUniqueId.htm (accessed on 2025-07-31).

- Grieves, M.; Vickers, J. Digital Twin: Mitigating Unpredictable, Undesirable Emergent Behavior in Complex Systems. In Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems; Kahlen, F.-J., Flumerfelt, S., Alves, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2017; pp. 85–113. [CrossRef]

- Fuller, A.; Fan, Z.; Day, C.; Barlow, C. Digital Twin: Enabling Technologies, Challenges and Open Research. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 108952–108971. [CrossRef]

- Bille, R.; Smith, S.P.; Maund, K.; Brewer, G. Extending Building Information Models into Game Engines. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Interactive Entertainment (IE 2014); ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Zhong, R.Y.; Jiang, Y. Digital Twin and Its Applications in the Construction Industry: A State-of-Art Systematic Review. Digital Twin 2024, 3, 17664. [CrossRef]

- Autodesk; FMI. Harnessing the Data Advantage in Construction. 2021. Available online: https://constructioncloud.autodesk.com/rs/572-JSV-775/images/harnessing_the_data_advantage_in_construction_fmi_apac.pdf (accessed on 2025-09-05).

- Leygonie, R. Data Quality Assessment of BIM Models for Facility Management. Master’s Thesis, École de technologie supérieure (ÉTS), Montréal, Canada, 2020. Available online: https://espace.etsmtl.ca/id/eprint/2629/ (accessed on 2025-09-24).

- Tanga, O.; Akinradewo, O.; Aigbavboa, C.; Oke, A.; Adekunle, S. Data Management Risks: A Bane of Construction Project Performance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12793. [CrossRef]

- Opoku, D.-G.J.; Perera, S.; Osei-Kyei, R.; Rashidi, M.; Bamdad, K.; Famakinwa, T. Barriers to the Adoption of Digital Twin in the Construction Industry: A Literature Review. Informatics 2023, 10, 14. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, T. Review on the Application of Artificial Intelligence in Smart Homes. Smart Cities 2019, 2, 402–420. [CrossRef]

- Grand View Research. Smart Home Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report, 2025–2030. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/smart-homes-industry (accessed on 2025-08-03).

- ISO. ISO 16484-1:2024 – Building Automation and Control Systems (BACS)—Part 1: Project Specification and Implementation. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/84890.html (accessed on 2025-08-03).

- International Code Council. 2021 IRC: International Residential Code for One- and Two-Family Dwellings; ICC: Country Club Hills, IL, USA, 2020. ISBN 978-1-60983-957-4.

- Alnaggar, A.; Pitt, M. Towards a Conceptual Framework to Manage BIM/COBie Asset Data Using a Standard Project Management Methodology. Journal of Facilities Management 2019, 17, 175–187. [CrossRef]

- Becks, E.; Zdankin, P.; Matkovic, V.; Weis, T. Complexity of Smart Home Setups: A Qualitative User Study on Smart Home Assistance and Implications on Technical Requirements. Technologies 2023, 11, 9. [CrossRef]

- Cespedes-Cubides, A.S.; Jradi, M. A Review of Building Digital Twins to Improve Energy Efficiency in the Building Operational Stage. Energy Informatics 2024, 7, 11. [CrossRef]

- OSArch Community. IfcOpenShell Scripting on IFC Loaded in BlenderBIM. 2021. Available online: https://community.osarch.org/discussion/504/ifcopenshell-scripting-on-ifc-file-loaded-in-blenderbim (accessed on 2025-09-24).

- agron. GUIDs in an BIM Project. buildingSMART Forums (IFC), 2020-04-10. Available online: https://forums.buildingsmart.org/t/guids-in-an-bim-project/2593 (accessed on 2025-09-24).

- Omrany, H.; Al-Obaidi, K.M.; Husain, A.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A. Digital Twins in the Construction Industry: A Comprehensive Review of Current Implementations, Enabling Technologies, and Future Directions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10908. [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.U.; Kim, I.; Hwang, K.-E. Advancing BIM and Game Engine Integration in the AEC Industry: Innovations, Challenges, and Future Directions. Journal of Computational Design and Engineering 2025, 12, 26–54. [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE. ASHRAE Handbook—HVAC Applications; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2023.

- ISO. ISO 16739-1:2024 – Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) for Data Sharing—Part 1: Data Schema. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/84123.html (accessed on 2025-07-31).

- Unity Technologies. Manual: Asset Metadata. Available online: https://docs.unity3d.com/6000.2/Documentation/Manual/AssetMetadata.html (accessed on 2025-08-21).

- Leach, P.J.; Mealling, M.; Salz, R. A Universally Unique IDentifier (UUID) URN Namespace. RFC 4122, IETF, 2005. Available online: https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc4122 (accessed on 2025-09-24).

- Solibri. 176 Model Structure. Available online: https://help.solibri.com/hc/en-us/articles/1500004610581-176-Model-Structure (accessed on 2025-08-13).

- Autodesk Support. Missing IfcGUID Properties in Some Rebar Elements after Loading the IFC File into Revit. Available online: https://www.autodesk.com/support/technical/article/caas/sfdcarticles/sfdcarticles/Missing-IfcGUID-properties-in-some-rebar-elements-after-loading-the-IFC-file-into-Revit.html (accessed on 2025-08-13).

- buildingSMART International. Information Delivery Specification (IDS) v1.0 Is Approved as a Final Standard. News, 4 June 2024. Available online: https://www.buildingsmart.org/information-delivery-specification-ids-v1-0-is-approved-as-a-final-standard/ (accessed on 2025-09-05).

- Liu, W.; Lv, Y; Wang, Q.; Sun, B.; Han, D. A Systematic Review of the Digital Twin Technology in Buildings, Landscape and Urban Environment from 2018 to 2024. Buildings 2024, 14, 3475. [CrossRef]

- Din, Z.U.; Mohammadi, P.; Sherman, R. A Systematic Review and Analysis of the Viability of Virtual Reality (VR) in Construction Work and Education. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.01450. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.01450 (accessed on 2025-09-24).

- Abanda, F.H.; Balu, B.; Adukpo, S.E.; Akintola, A. Decoding ISO 19650 Through Process Modelling for Information Management and Stakeholder Communication in BIM. Buildings 2025, 15, 431. [CrossRef]

- Toldo, B.M.; Zanchetta, C. Building Management System and IoT Technology: Data Analysis and Standard Communication Protocols for Building Information Modeling. In Proceedings of the 41st International Conference of CIB W78; Marrakech, Morocco, 1–3 October 2024. ISSN 2706-6568. Available online: http://itc.scix.net/paper/w78-2024-77 (accessed on 2025-09-24).

- Connectivity Standards Alliance (CSA). Matter Application Cluster Specification, Version 1.2; Document 23-27350-003; 2023-10-18. Available online: https://csa-iot.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Matter-1.2-Application-Cluster-Specification.pdf (accessed on 2025-09-24).

- Liu, Y.; Castronovo, F.; Messner, J.; Leicht, R. Evaluating the Impact of Virtual Reality on Design Review Meetings. Journal of Computing in Civil Engineering 2020, 34, 04019045. [CrossRef]

- ACM. Artifact Review and Badging. Available online: https://reviewers.acm.org/training-course/artifact-review-and-badging (accessed on 2025-09-05).

- Tuhaise, V.V.; Tah, J.H.M.; Abanda, F.H. Technologies for Digital Twin Applications in Construction. Automation in Construction 2023, 152, 104931. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).