1. Introduction

Facility Management is evolving rapidly as BIM integrates with IoT, enabling digital twins for real-time data management [

1,

2]. This integration combines static BIM data—including spatial geometries, asset metadata, and detailed building component information—with dynamic IoT sensor data streams, facilitating continuous monitoring of IEQ and informed operational decision-making [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Additionally, integrating machine learning (ML) further enhances these digital twins, enabling predictive maintenance to improve occupant health, energy efficiency, and asset longevity [

7,

8].

However, practical BIM–IoT implementation continues to face significant challenges. Traditional Building Management Systems (BMS) often lack interoperability, typically operating independently from BIM models, thereby limiting advanced analytical capabilities [

6,

9]. Retrofitting existing buildings with IoT infrastructure presents complex technical and economic barriers, particularly when integrating diverse sensor data into established BIM environments [

10,

11]. FM personnel often struggle with advanced BIM tools due to steep learning curves [

12,

13,

22,

28,

29]. Organizational reluctance to invest, driven by unclear returns on investment and significant upfront costs, further impedes widespread adoption [

11,

14,

15,

30,

31]. Furthermore, although IFC, recognized as the primary open standard for BIM, supports cross-platform interoperability, IFC formats are not inherently optimized for real-time operational data exchange. Thus, converting IFC data into web-compatible formats such as JSON becomes essential yet technically challenging [

16,

17].

This study addresses these identified limitations by introducing a vendor-neutral BIM–IoT integration framework specifically designed for real-time IEQ monitoring and predictive maintenance. In contrast to previous studies that predominantly utilized XML-based IFC data conversions [

16,

18], the official format endorsed by buildingSMART and ISO standards—this research employs JSON. Although JSON is currently categorized as a provisional or candidate standard by buildingSMART, its widespread popularity and compatibility with web-based platforms offer practical advantages. Specifically, the proposed approach combines IFC-to-JSON conversions with Node-RED, a low-code platform that seamlessly integrates BIM models with real-time IoT sensor data. The resulting web-based dashboard provides intuitive, spatially contextualized visualization of IEQ metrics, significantly enhancing the decision-making capabilities of FM teams.

Prior literature on BIM maturity levels [

19] highlights the substantial challenges associated with achieving unified standards essential for BIM Level 3 implementation. Level 3 maturity necessitates advanced standardization, such as the adoption of a Common Data Environment (CDE) for centralized data management and IFC for seamless interoperability [

20,

21]. Recognizing these gaps, this study makes a distinct and novel contribution by simultaneously integrating open standards (IFC, JSON), multidisciplinary collaboration frameworks, low-code integration platforms, and robust cybersecurity protocols. Collectively, this approach advances the practical implementation of BIM–IoT integration frameworks, effectively progressing toward the full collaborative potential envisioned by BIM Level 3.

By addressing these identified technical, organizational, and usability barriers (Objective 1), evaluating existing methodologies (Objective 2), and designing a practical integration framework validated through a case study (Objective 3), this research clearly aims to improve BIM–IoT integration practices.

1.1. Research Contributes

This research delivers a practical, scalable framework for BIM and IoT integration in operational FM contexts, validated through a detailed case study. The primary contributions include:

Enhanced Data Interoperability: By converting IFC models into lightweight JSON, the framework ensures efficient and seamless integration with cloud-based platforms, facilitating unified management of diverse datasets.

Real-Time IEQ Monitoring: Integration of live IoT sensor streams with BIM components using low-code visual programming (Node-RED) enables real-time, spatially contextualized visualization, significantly enhancing operational decision-making.

Improved Usability and Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration: An intuitive, web-based dashboard facilitates collaboration among BIM modelers, IT developers, and FM professionals, overcoming traditional usability barriers.

Open Standards and Vendor Neutrality: Utilizing open standards (IFC, JSON) and accessible low-code tools, the framework minimizes reliance on proprietary software, reducing costs and supporting broad scalability.

2. Literature Review

The integration of BIM and the IoT has significant potential to enhance FM by providing detailed building information combined with real-time sensor data. Despite these advantages, the practical adoption of BIM–IoT integration faces multiple barriers, including technological, usability, organizational and workflow challenges, and advancements in Digital Twin technology.

2.1. Technological Barriers

Key technological barriers include interoperability issues and legacy BMS limitations. Traditional BMS platforms typically use proprietary protocols and isolated data architectures, complicating the integration of real-time IoT data with BIM models [

6,

11]. Additionally, current BIM standards such as IFC, designed initially for static design-phase data, lack adequate provisions for managing dynamic operational data, necessitating complex conversions into flexible, web-compatible formats such as JSON [

16,

17,

18]. This study directly addresses these gaps by employing IFC-to-JSON conversion methods and leveraging the low-code platform to facilitate real-time integration and interoperability.

2.2. Usability

Usability issues represent significant obstacles, as FM personnel often face steep learning curves when adapting to advanced BIM technologies, largely due to inadequate training and support [

13]. A shortage of BIM-trained FM staff further hampers efficient data usage and underutilizes BIM tools [

12]. These challenges are compounded by organizational resistance driven [

14,

15]. To mitigate these usability barriers, this introduces an intuitive, web-based dashboard designed specifically for ease of use by FM professionals without extensive BIM expertise.

2.3. Organizational and Workflow Challenges

Organizational barriers frequently arise due to insufficient managerial support, unclear roles, and ambiguous expectations regarding the return on investment from BIM–IoT integration initiatives [

11,

22]. Furthermore, the extended duration of the FM phase, combined with inconsistent data governance and fragmented workflows, exacerbates these challenges [

23,

24]. Such organizational inertia hinders the effective transition from the construction to the FM phase, leading to suboptimal BIM utilization and fragmented data management [

25]. Addressing these issues, this provides a structured, replicable integration framework that defines responsibilities, standardized workflows, and data management practices, ensuring seamless integration and maintenance continuity.

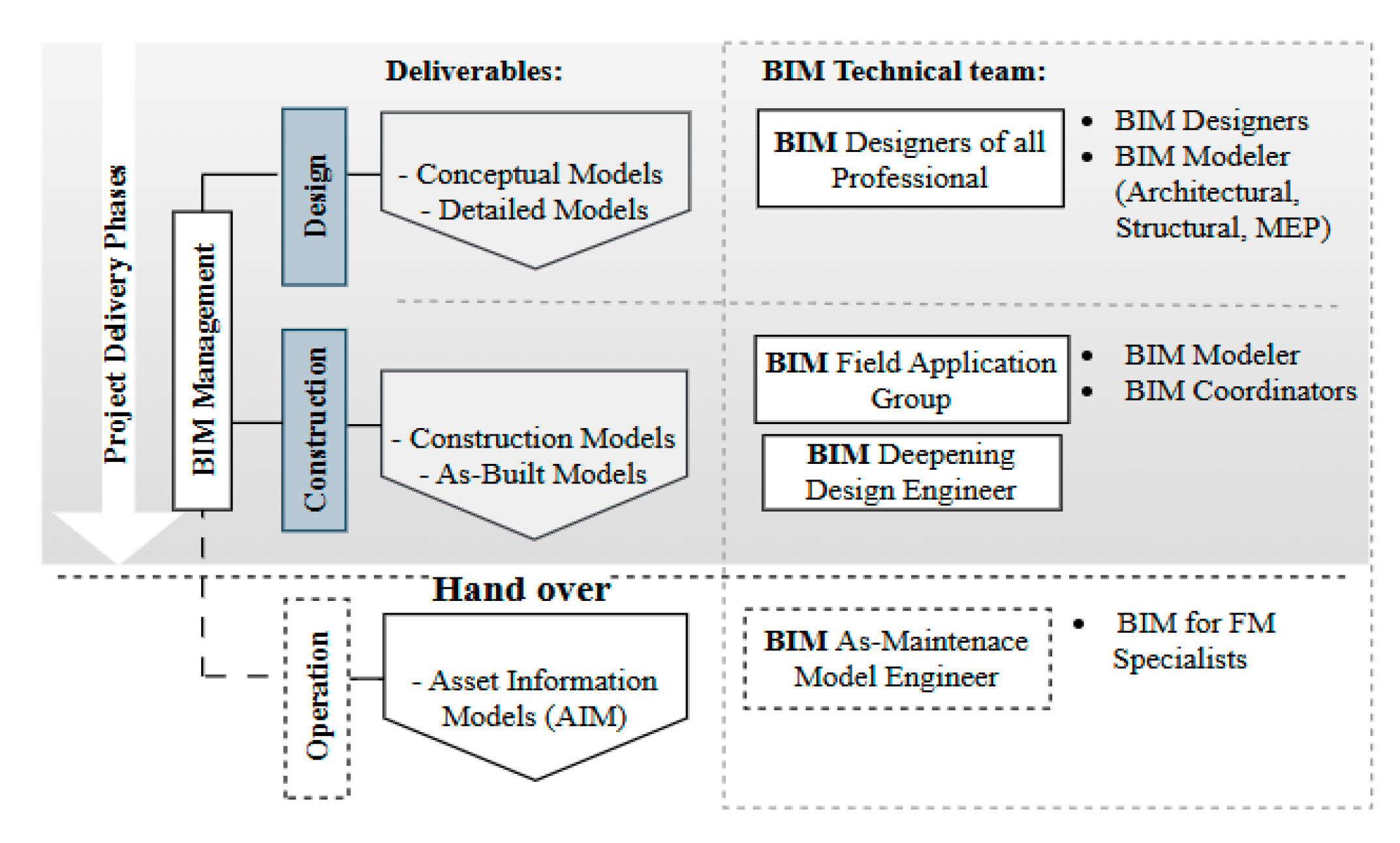

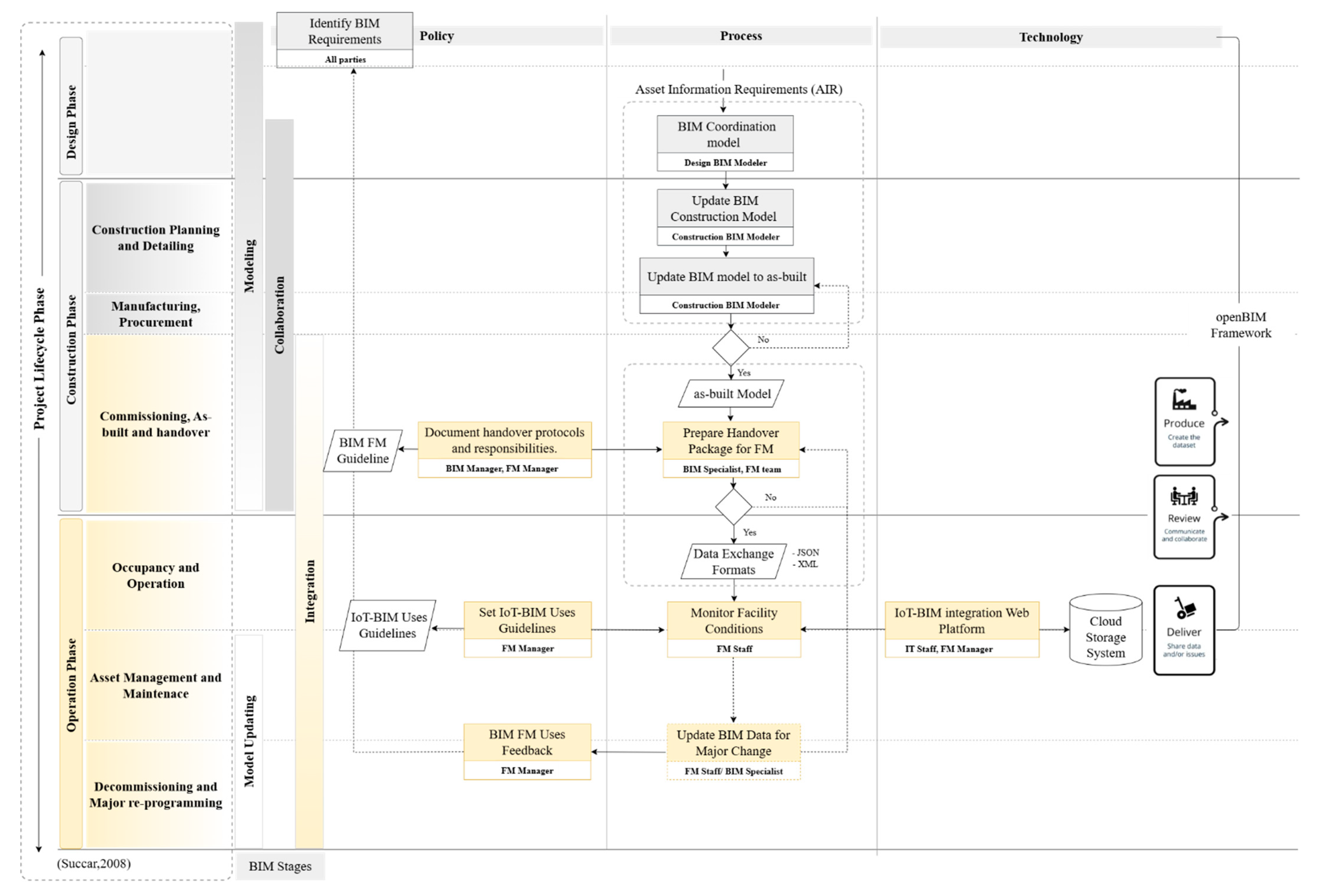

(

Figure 1) depicts the handover gap between BIM management in construction phases and operational phases, underscoring the necessity of clear organizational roles, structured workflows, and standardized.

2.4. Advancements in Digital Twin Technology

Recent advancements position BIM–IoT integration within the broader context of digital twin technology, which enhances capabilities such as predictive analytics and predictive maintenance [

1,

2,

7]. Although digital twin implementations are becoming increasingly sophisticated, widespread adoption remains limited due to persistent interoperability and usability issues [

8]. This contributes to this emerging field by providing a practical example of a scalable, vendor-neutral implementation. The proposed approach leverages open standards, and accessible low-code tools, addressing critical gaps highlighted by recent literature and demonstrating applicability and ease of adoption.

In summary, effective BIM integration in FM requires overcoming key challenges in interoperability, usability, organizational commitment, limited practical implementation, and workflow standardization. As highlighted in

Table 1, the absence of clearly defined roles and structured workflows at the BIM-to-FM transition stage frequently undermines FM operations. This study specifically addresses these gaps by proposing a structured integration framework that leverages open standards, intuitive dashboards, and standardized processes, thus fostering more robust, sustainable, and scalable BIM–IoT integration.

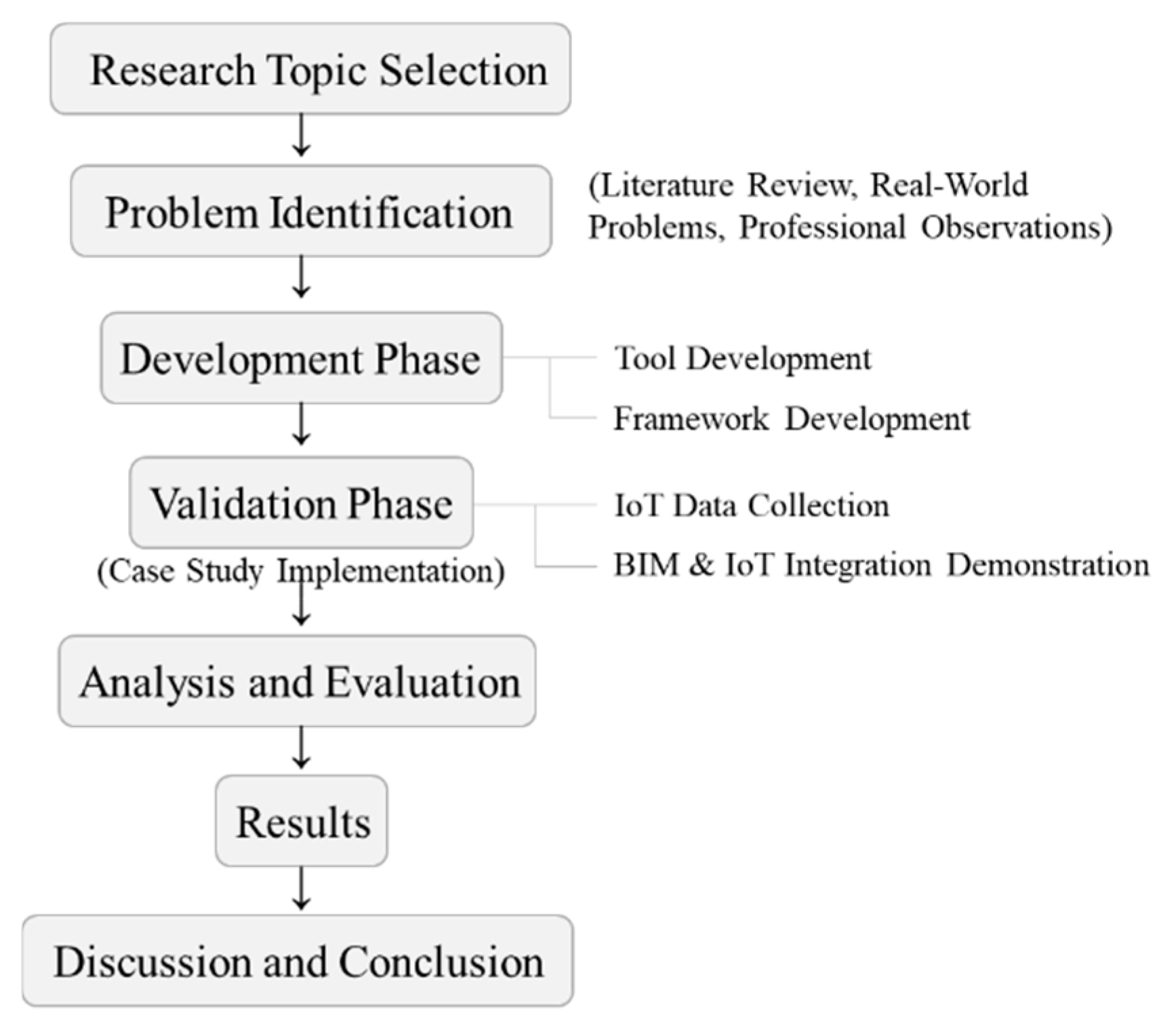

3. Research Method

This study employs a structured mixed-method approach to develop and validate a practical BIM–IoT integration framework tailored for FM, with a focus on IEQ. The research methodology involves sequential phases, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

This research began by selecting the research topic through an initial literature review, clearly defining the study’s context. Subsequently, the problem identification phase involved analyzing current FM practices to pinpoint barriers affecting BIM–IoT integration. The development phase involved designing a web-based tool leveraging data conversions and low-code programming. The validation phase comprised an empirical case study conducted in an operational office building, integrating detailed BIM models with IoT sensors measuring IEQ parameters. Analysis rigorously assessed system responsiveness, accuracy, and usability, confirming its effectiveness for IEQ monitoring and predictive maintenance. Concluding with discussions about its scalability, interoperability, and practical implications for FM operations.

4. Proposed Approach

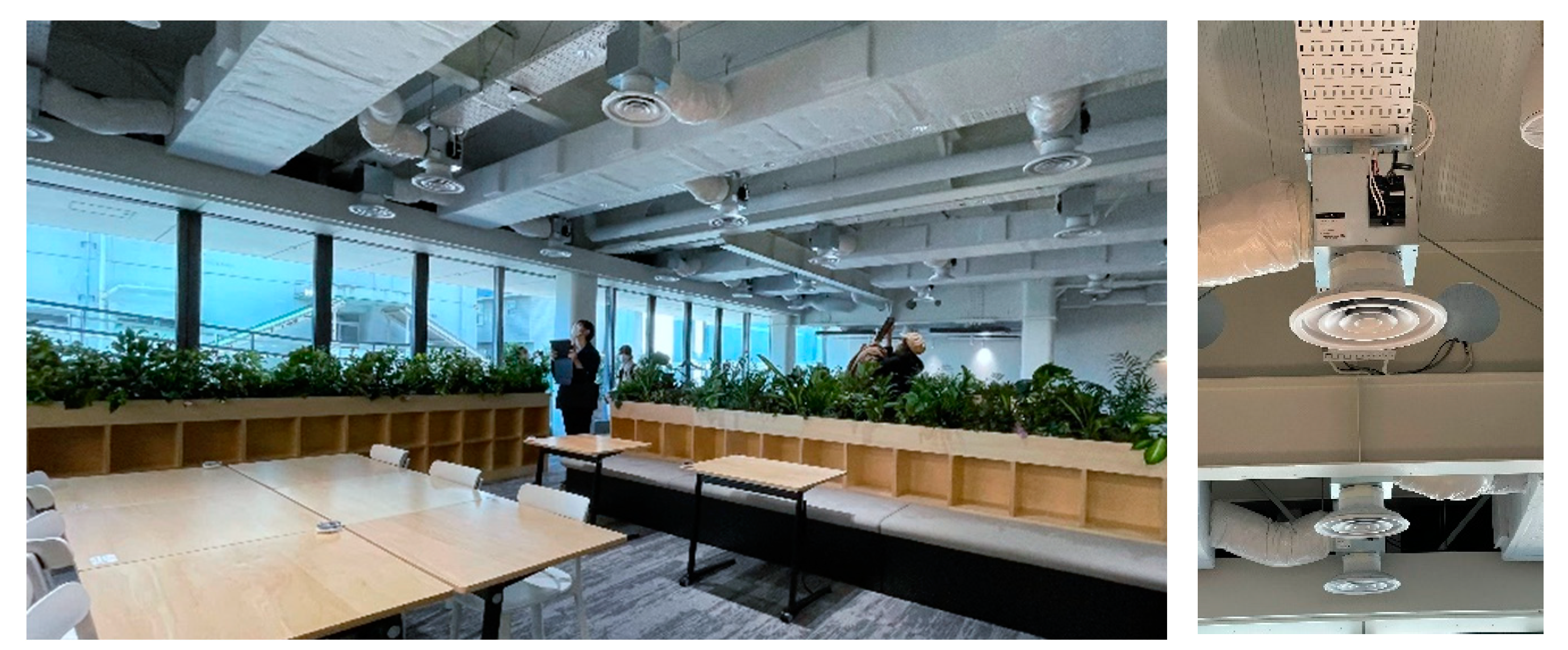

4.1. Case Study: Office Building in Kanagawa, Japan.

This study utilized a practical case study of a six-storey office building located in Kanagawa, Japan. Serving dual functions, the facility operates both as a workspace for employees and as a test environment for advanced building technologies, particularly environmental sensing systems (

Figure 3). Detailed BIM data and IoT sensor outputs from this building were essential for this research. This study specifically focused on the first-floor co-working space, selected for its ability to provide comprehensive IoT sensor data related to IEQ, managed and monitored through the building’s centralized BMS. This data was critical for demonstrating and validating the practical integration benefits of BIM–IoT technologies in FM.

4.2. Data Source and Collection

The data utilized in this study strictly adhere to defined BIM–IoT–FM maintenance requirements from prior literature. Data sources are clearly categorized as either originating from BIM models or external platforms.

Table 2 outlines the recommended storage locations, clearly categorizing each data type and providing succinct details for clarity.

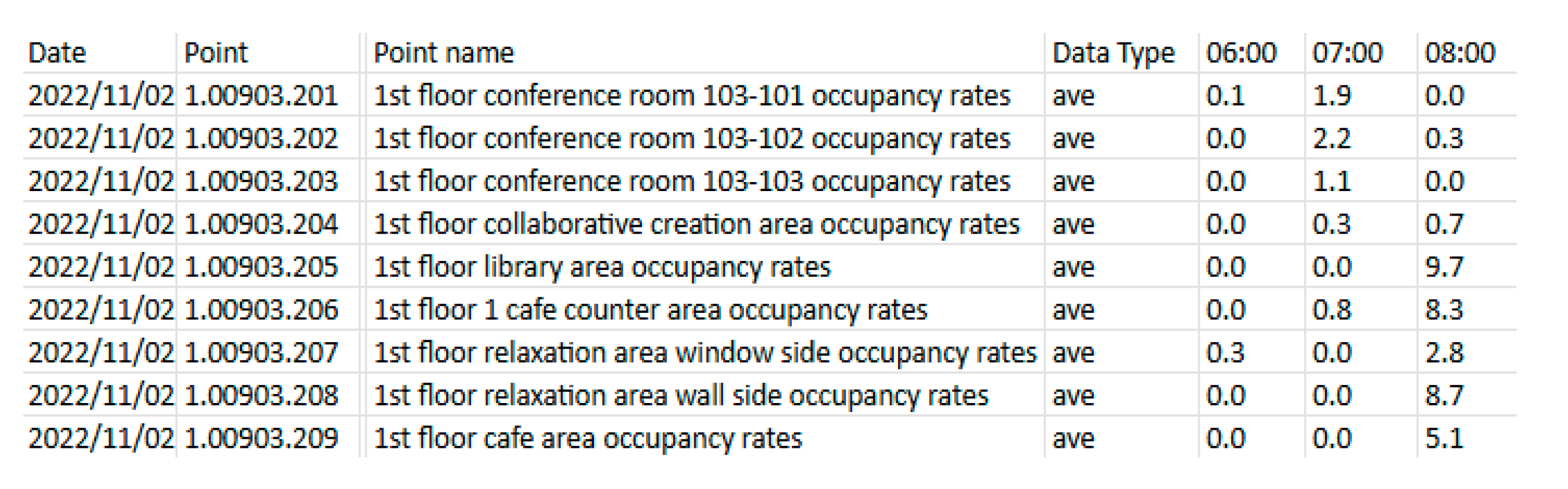

Sensor data were collected via the building's BMS due to cybersecurity policies restricting direct real-time streaming. To address this, the BMS generated CSV files at scheduled intervals containing sensor identifiers, timestamps, and measured IEQ parameters as illustrated in

Figure 4. A secure Node-RED workflow was implemented to periodically access and integrate these CSV files, facilitating secure data transfer and testing.

Sensors were linked directly to BIM elements (e.g., rooms) using GlobalIds provided by the IFC model. Sensor identifiers or zone names from the BMS were systematically mapped to these GlobalIds through a clearly defined Sensor–BIM Mapping Table, enabling automated and accurate linkage between IoT sensor data and BIM components.

This structured mapping facilitates automatic and accurate alignment of real-time IoT sensor data with specific BIM components, enabling dynamic, spatially contextualized visualization on the web-based dashboard. Following data collection, a structured mapping process was developed to align sensor data from the BMS with BIM elements through their GlobalId identifiers. This mapping facilitated seamless data integration and visualization, as detailed in the subsequent IFC-to-JSON conversion process.

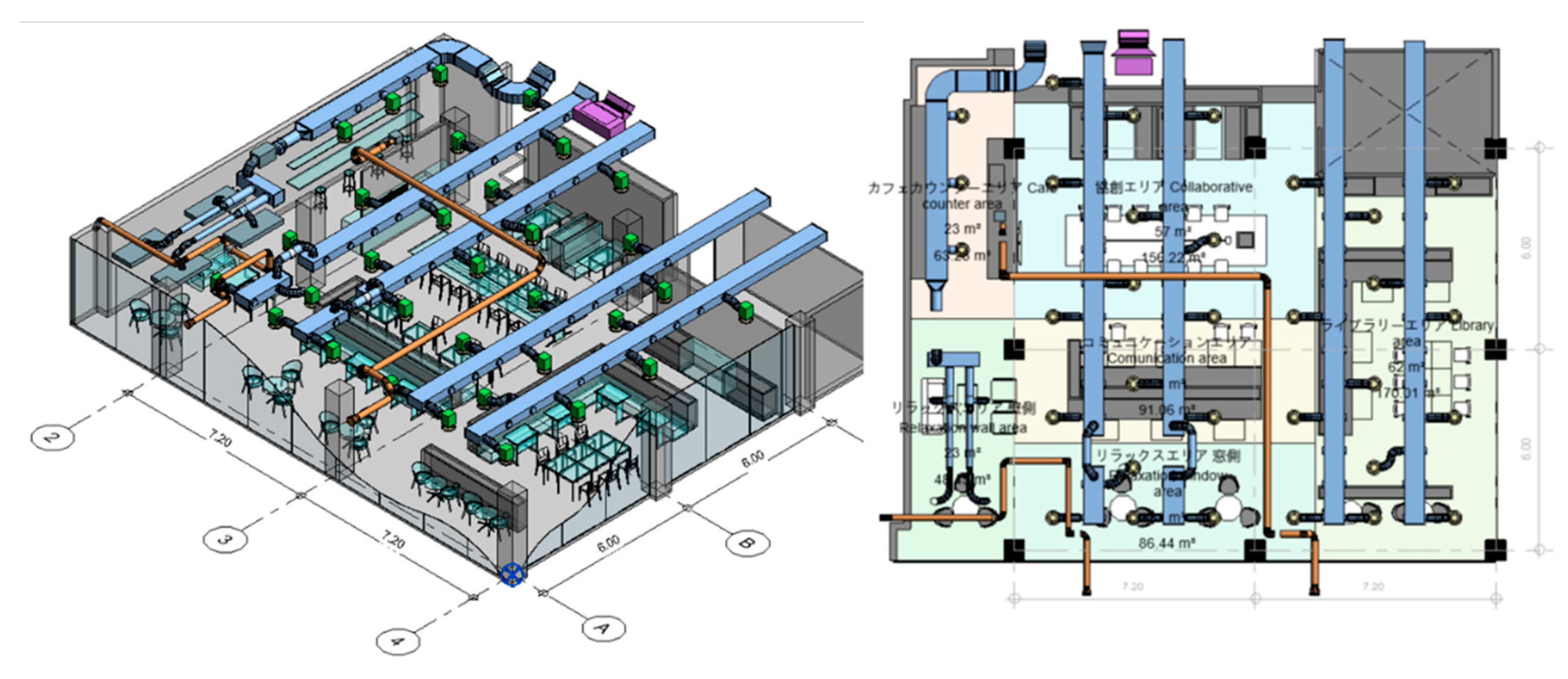

4.3. IFC-to-JSON Data Conversion

Prior to the data conversion, the BIM models as illustrated in

Figure 5, were created and managed in Autodesk Revit. To facilitate interoperability, these models were exported to the IFC format, specifically IFC4 was selected as it is the latest widely adopted IFC standard, providing improved interoperability and richer property sets essential for FM. JSON was chosen due to its lightweight structure, compatibility with web platforms, and ease of integration with IoT data, adhering to internationally recognized open BIM standards. The IFC export process involved selecting appropriate export settings to ensure the retention of relevant data, including geometry, spatial relationships, and element properties.

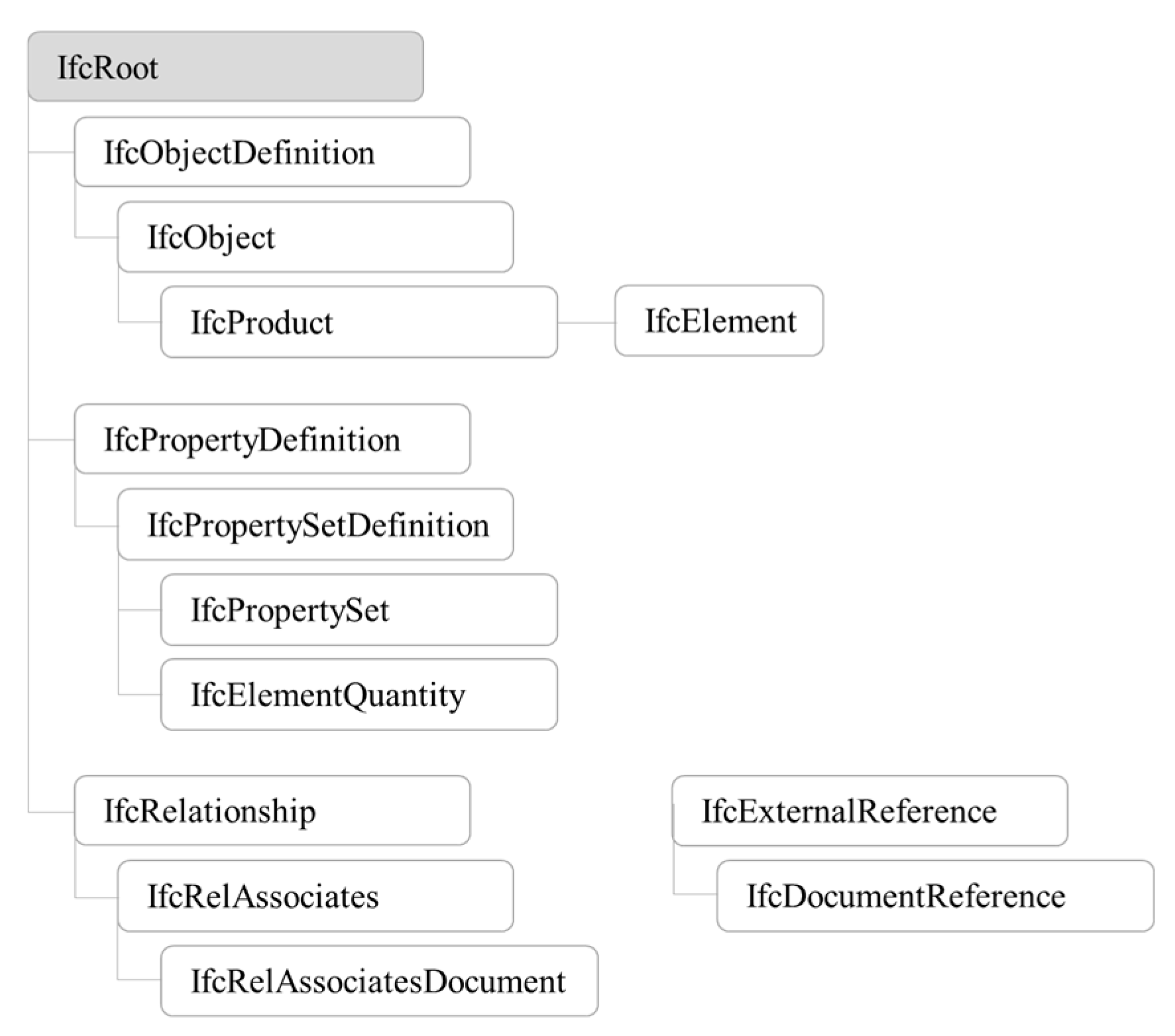

IFC represent a vendor-neutral, international standard facilitating structured building data exchange, crucial for BIM interoperability within FM and IoT systems. IFC systematically organizes building information into hierarchical entities and clearly defined relationships, enabling streamlined data management and comprehensive interoperability.

This study specifically adopts the IFC data structure as illustrated in

Figure 6, originate with fundamental entities such as

IfcRoot, capturing critical attributes like GlobalId and OwnerHistory. These expand into tangible building elements

(IfcElement), including physical components like doors, walls, and mechanical systems. Each IFC element provides metadata essential for asset management operations. Properties associated with these elements are defined either through user-defined attributes in

IfcPropertySet (e.g., materials, manufacturers) or standardized measurable parameters (area, volume, length) through

IfcElementQuantity, supporting maintenance scheduling, asset tracking, and lifecycle management decisions.

Moreover, IFC integrates external resource management via IfcDocumentReference, storing external links (URLs, file paths), effectively connecting BIM data with IoT platforms and other FM systems, thus enhancing predictive maintenance workflows. To facilitate lightweight, web-based BIM data integration for FM, this research implemented an IFC-to-JSON conversion pipeline using the open-source IfcOpenShell Python library. The extraction targeted three primary data categories necessary for FM workflows: Asset Information, Spatial Information, and External System References:

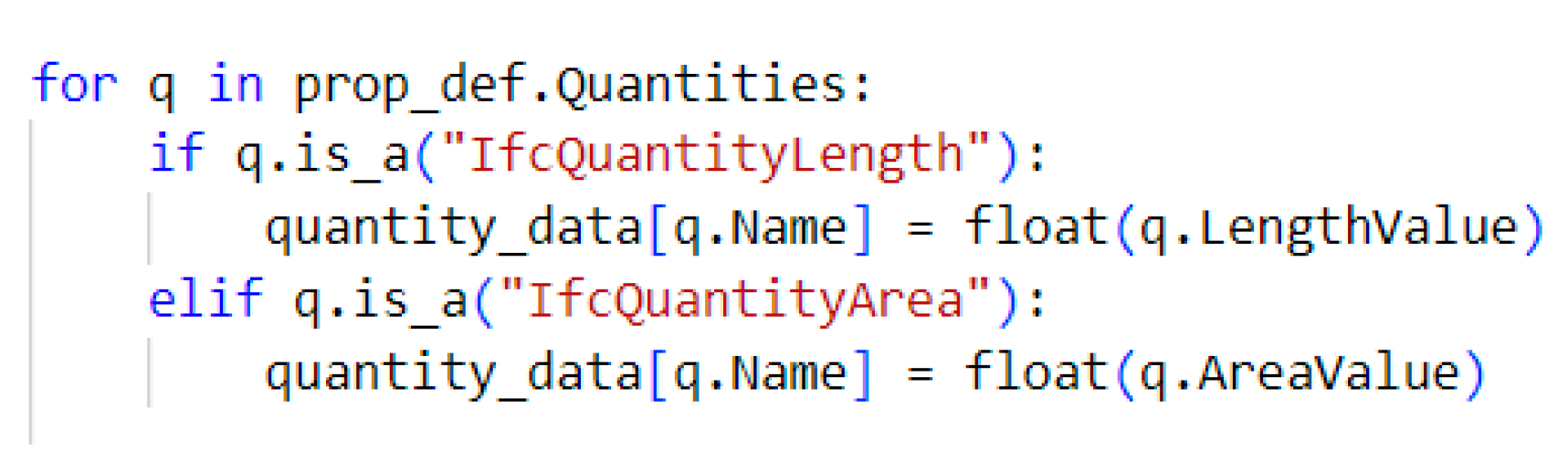

Asset Information (Metadata and Quantities): Asset metadata was collected from each IfcProduct entity using .get_info(), selectively retaining properties relevant to FM (e.g., Name, GlobalId, PredefinedType, Tag). Quantitative data embedded within IfcElementQuantity sets—such as area, volume, and length—were extracted via a dedicated Python function:

Structured asset metadata and quantities were formatted clearly within JSON, enabling direct accessibility for downstream FM systems.

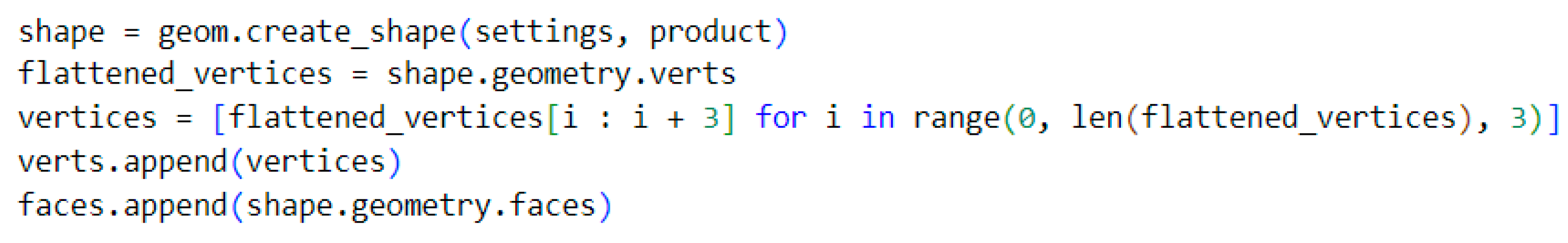

Spatial Information (Geometric Representation): To preserve the spatial context of each asset, the script utilizes the geom.create_shape() method from IfcOpenShell's geometry module. This method converts the 3D representation of each IfcProduct into a list of vertices and indexed triangle faces. The geometry is processed using world coordinates to maintain consistency across elements.

Figure 8.

Python script converting IFC geometry for web-based 3D visualization.

Figure 8.

Python script converting IFC geometry for web-based 3D visualization.

The resulting geometric data, stored under a "points" attribute in JSON, enabled seamless integration with web-based 3D viewers for contextualized real-time sensor visualization.

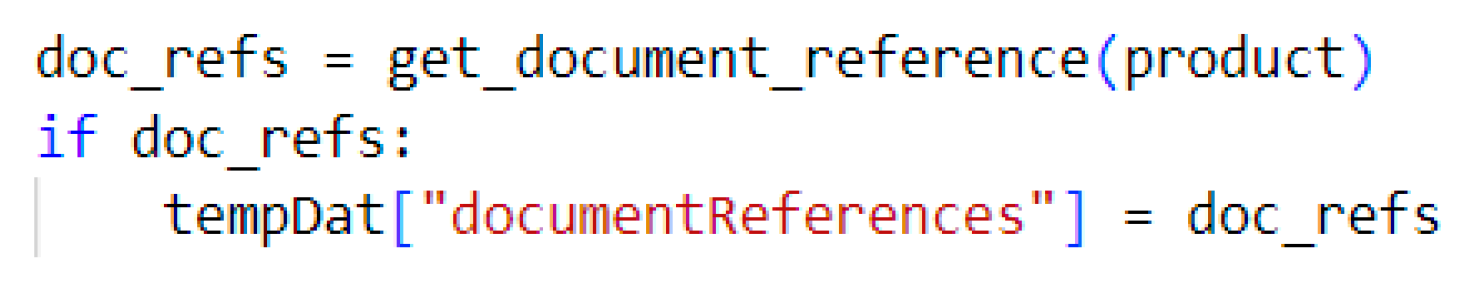

Figure 9.

Python script retrieving external document references from IFC entities.

Figure 9.

Python script retrieving external document references from IFC entities.

This functionality enabled IFC elements to serve as direct access points to external documentation, sensor data platforms, and maintenance records, thereby supporting integrated workflows encompassing digital logbooks, performance monitoring, and predictive maintenance strategies within a unified interface.

Following the IFC-to-JSON data conversion, this section introduces the proposed web-based BIM–IoT integration framework, which utilizes structured BIM data to visualize and manage real-time IoT sensor streams.

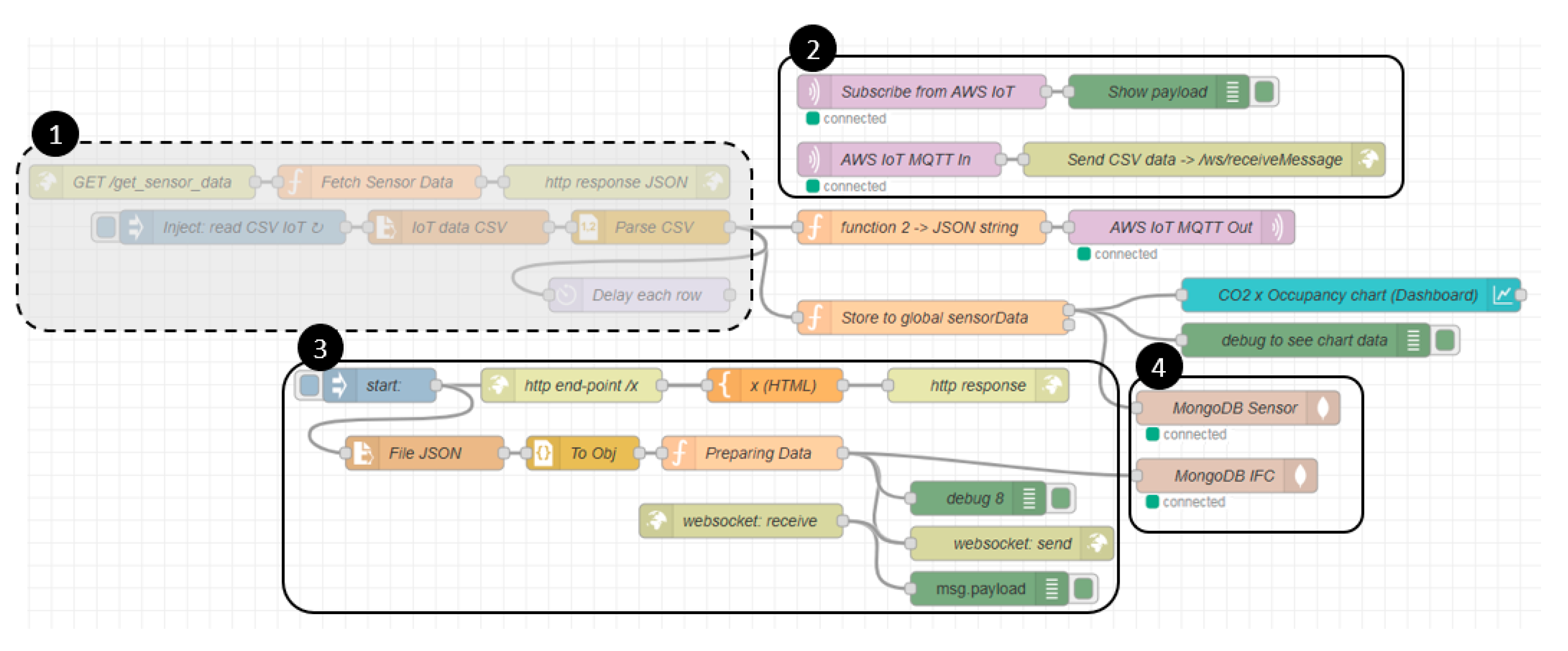

4.4. Node-RED Workflow for Data Integration

Node-RED, a visual low-code programming tool, is utilized to integrate and visualize BIM and real-time IoT sensor data on a web-based dashboard. This Node-RED workflow as illustrate in

Figure 10, leverages structured JSON data, aligning BIM components with sensor data streams. The Python-based scripts detailed facilitate the extraction and formatting of BIM data, ensuring accurate and efficient integration.

The Node-RED implementation detailed comprehensively addresses the limitations of real-time IoT data access due to stringent cybersecurity restrictions, effectively demonstrating a realistic IoT data integration scenario:

Sensor Data Retrieval and Real-Time Simulation (1) : Due to cybersecurity constraints preventing direct real-time data streaming from the BMS, a practical data simulation method was implemented. Node-RED workflows continuously retrieve periodic CSV exports from the BMS containing IEQ parameters such as CO₂ levels, occupancy, temperature, and humidity. Each CSV file is systematically parsed, converting each row into structured JSON objects, including sensor identifiers, timestamps, and measurement values. This approach effectively emulates real-time data streams, thereby enabling realistic system testing and validation without compromising data security.

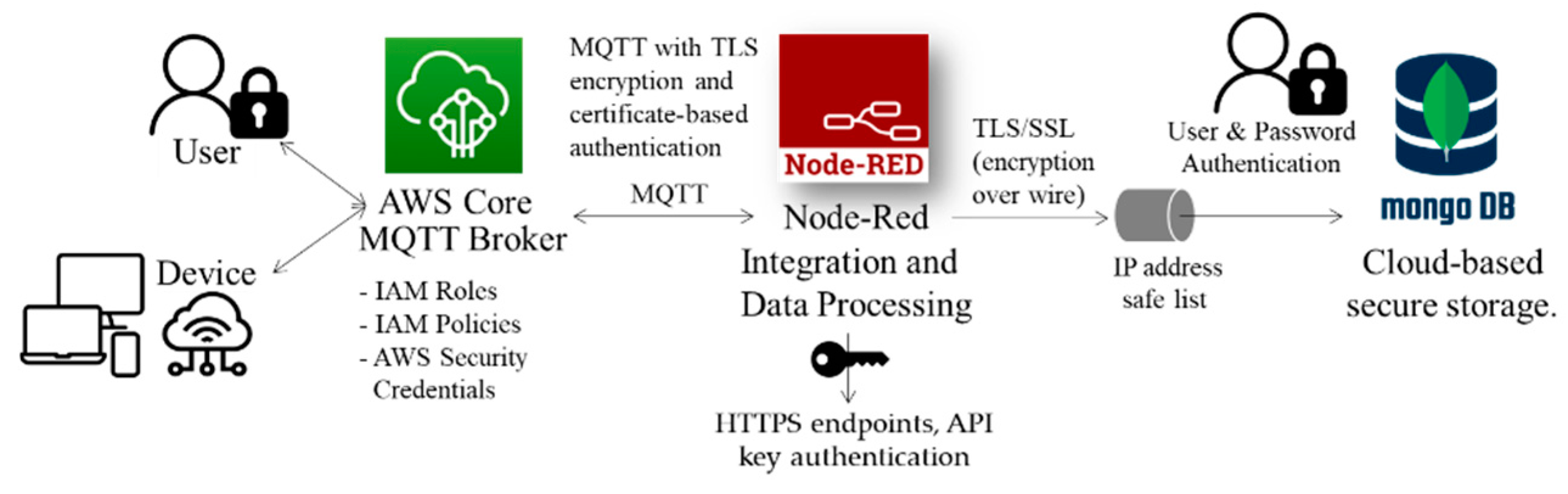

Real-Time Data Streaming (2) : The parsed sensor data are securely transmitted in real-time using the MQTT protocol through AWS IoT Core, an IoT broker providing robust security features such as Transport Layer Security (TLS) encryption and certificate-based authentication. MQTT subscription nodes (AWS IoT MQTT In) ensure secure and continuous sensor data streaming, subsequently relaying these data points to the dashboard for instantaneous visualization. This robust security architecture guarantees reliable and secure data flow between the BMS and the visualization components.

HTTP Endpoint. (3) : An HTTP endpoint (/x) within Node-RED acts as the primary data gateway for interactive client-server communication. Upon receiving a client request, structured JSON files derived from IFC-based BIM models are loaded, parsed, and processed into JavaScript objects for seamless integration. These data are then combined with real-time IoT sensor streams through sophisticated client-side visualizations powered by advanced web technologies, including Three.js and Chart.js. WebSocket nodes enable real-time, bidirectional data transmission between server and client interfaces, ensuring responsive and dynamic visualization updates.

Database Management for Historical Analytics (4) : Long-term data storage and management are handled via MongoDB, integrated within Node-RED. Two dedicated MongoDB nodes (MongoDB Sensor and MongoDB IFC) separately store sensor data and BIM-related metadata, respectively. This structured storage allows comprehensive historical analyses, enabling advanced analytics and machine-learning-based predictive maintenance. Consequently, facility managers benefit from actionable insights derived from historical data, significantly enhancing predictive operational capabilities.

4.5. Web-Based BIM–IoT Integration

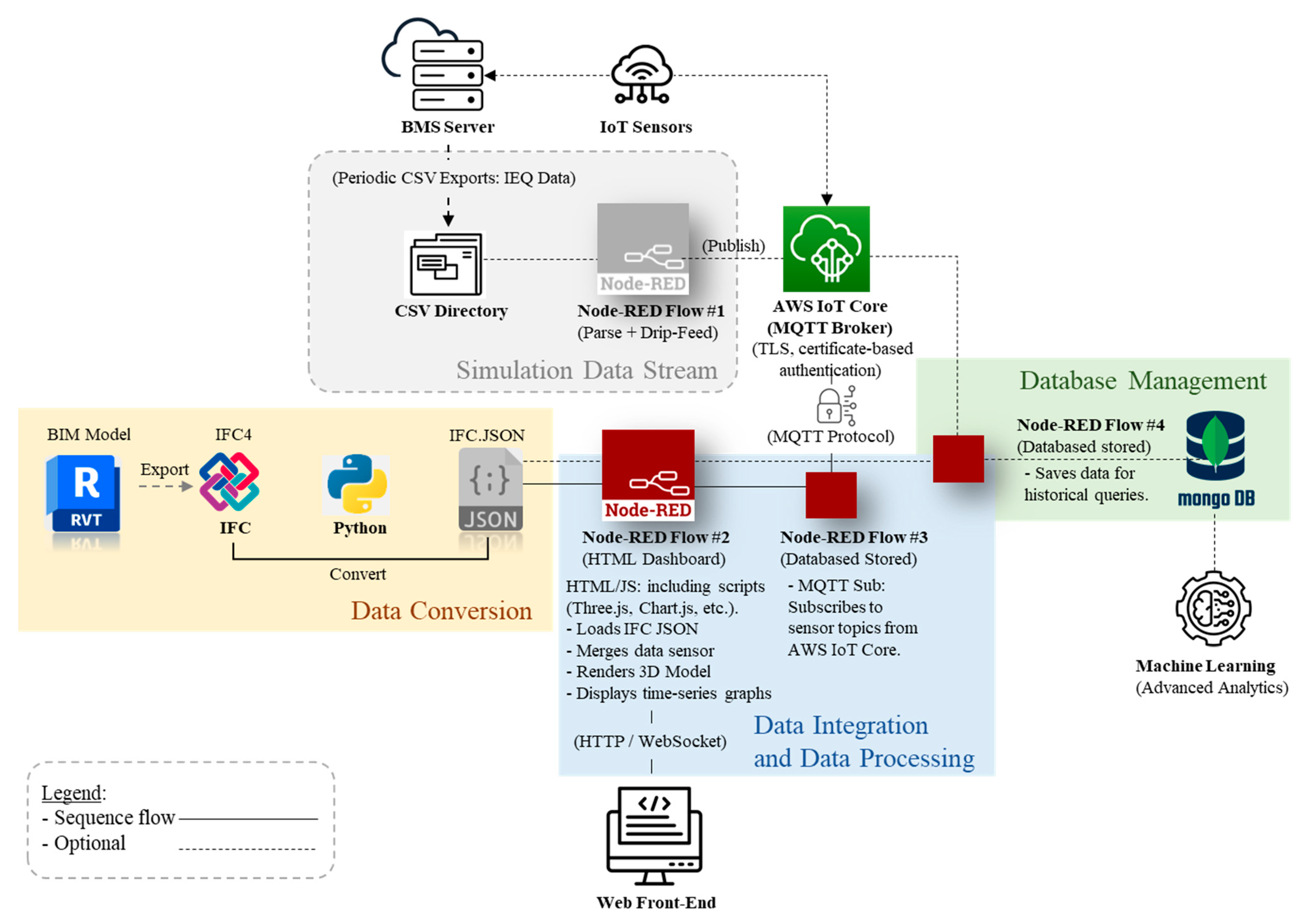

The proposed BIM–IoT integration framework as illustrate in

Figure 11, presents a comprehensive and robust approach for integrating BIM data with real-time IoT sensor streams, significantly enhancing FM operations. Initially, detailed BIM models developed in Revit are exported to IFC4 format, an internationally recognized open standard ensuring interoperability. These IFC files are subsequently converted into structured JSON data through a Python-based parser, extracting essential spatial geometries, hierarchical structures (e.g., IfcBuilding, IfcSpace), and unique GlobalIds. The JSON data is then stored on servers or directly embedded within web-based applications, supporting dynamic and interactive visualizations of building elements alongside their associated sensor data. Node-RED, a visual programming tool, is utilized to integrate and visualize BIM and IoT datasets seamlessly. Real-time IoT sensor data—such as temperature, humidity, occupancy, and CO₂ levels—are securely streamed via AWS IoT Core, an IoT broker employing MQTT protocol with TLS encryption and certificate-based authentication. This ensures secure, reliable, and real-time data transmission. Sensor data integration is accomplished by mapping IoT sensor identifiers to the BIM GlobalIds, enabling precise spatial representation and contextual visualization of environmental parameters.

Building upon the IFC-to-JSON data conversion and Node-RED workflows, the proposed BIM–IoT integration framework consolidates BIM spatial information with real-time IoT sensor data into a dynamic and interactive web-based visualization. The resulting web-based dashboard, developed using Node.js and HTML, provides interactive 3D models and time-series graphs. Additionally, heat maps illustrate spatial correlations, such as variations in CO₂ concentrations across different building zones. Historical sensor data, securely stored in MongoDB via Node-RED, facilitate advanced analytics, machine learning applications, and predictive maintenance strategies, significantly enhancing data-driven facility management decision-making.

5. Validation of the Proposed Framework

5.1. Interoperability and Dashboard Functionality

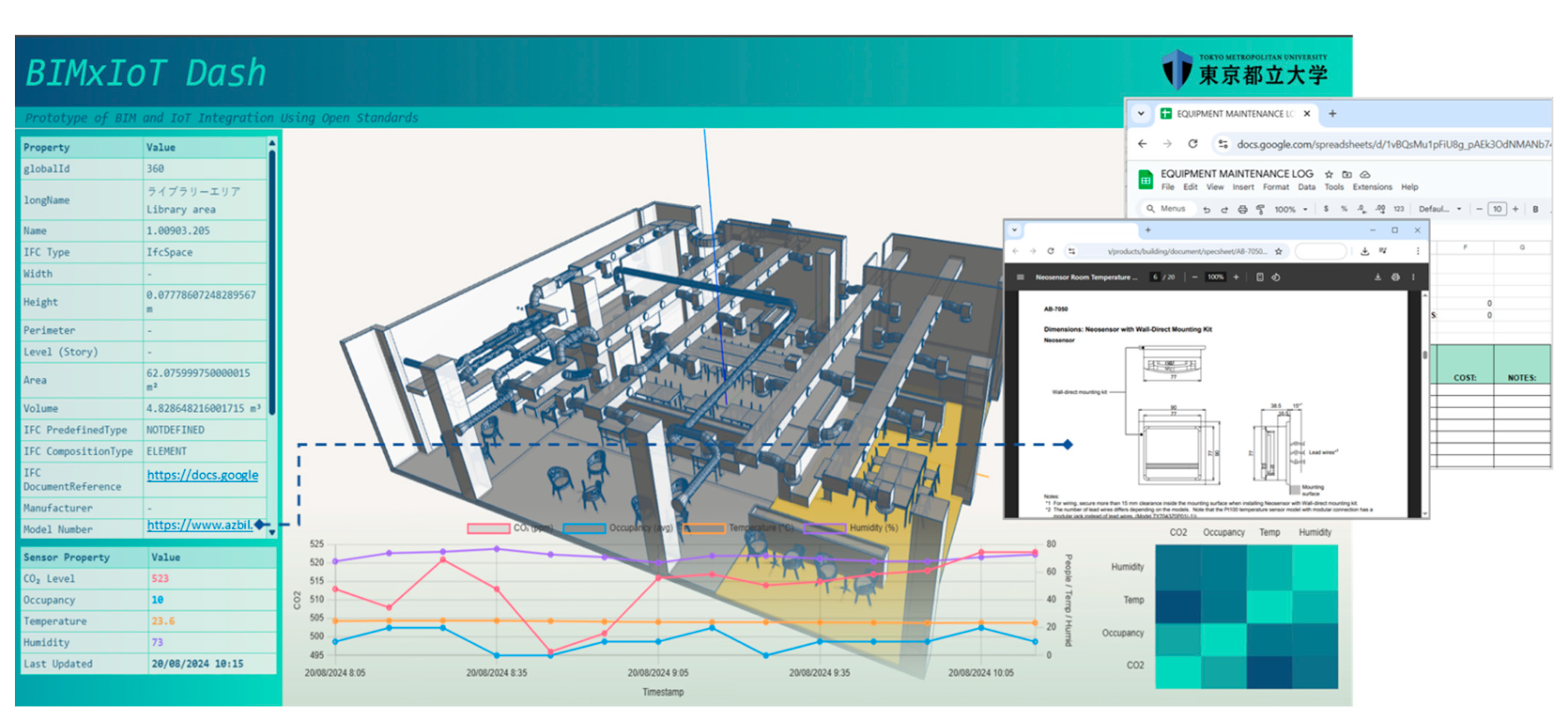

To validate the interoperability and functionality of the integration dashboard, extensive testing was conducted utilizing the developed framework. This evaluation specifically focused on assessing the effective integration of diverse data sources. As illustrated in

Figure 12, the web-based dashboard demonstrated real-time spatial contextualization of IoT sensor data within the BIM environment. Sensor data were accurately mapped, confirming robust interoperability between BIM and IoT datasets. Furthermore, the dashboard included fundamental analytical visualizations, such as heatmap graphs, effectively illustrating spatial variations in environmental parameters.

5.2. Advanced Data Integration and Machine Learning Application

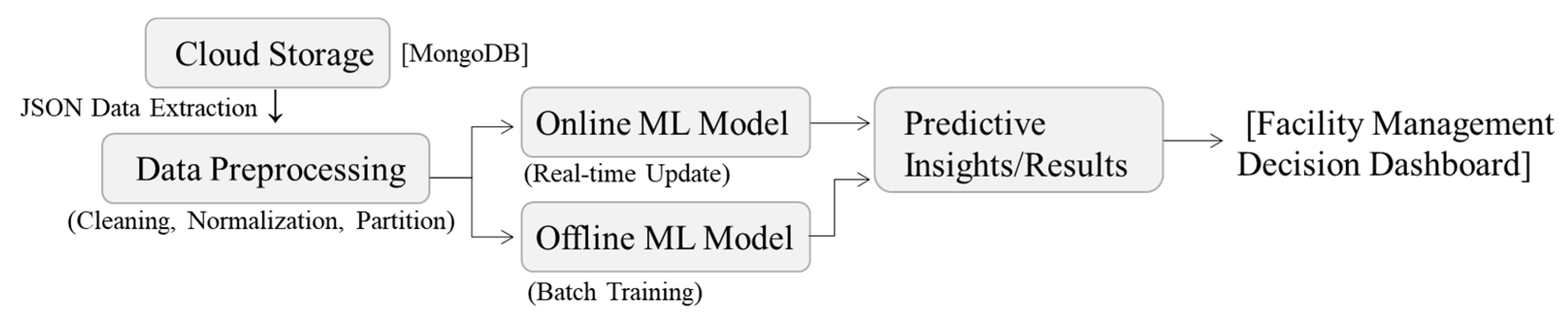

The integration framework developed not only visualizes IoT data within the BIM environment but also consolidates multidisciplinary data from multiple sources into a centralized, cloud-based repository. This unified data approach facilitates advanced analytical processing, such as ML, enhancing the framework's capability for predictive decision-making, as illustrate in

Figure 13.

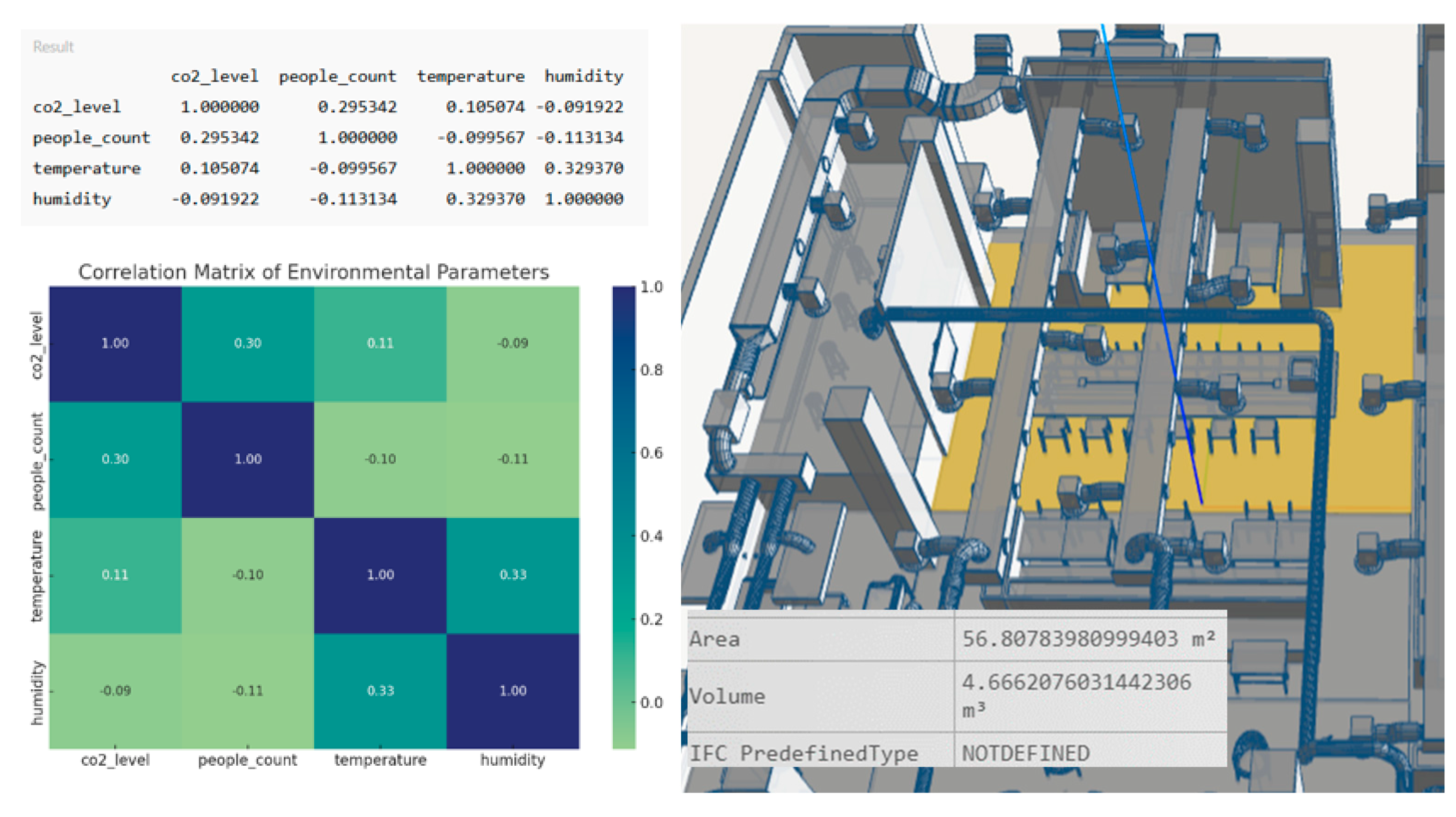

A correlation analysis identified a moderate positive relationship between occupancy and CO₂ levels (r=0.30), indicating significant occupancy influence. The identified correlation between occupancy levels and indoor CO₂ concentrations facilitates improved maintenance management through integration with BIM spatial data. Specifically, spatial information supports precise predictions and targeted proactive maintenance schedules. Facility managers can thus identify spaces consistently experiencing elevated CO₂ levels due to high occupancy and implement infrastructure enhancements, such as increased ventilation capacity or additional sensor deployment, as illustrate in

Figure 14.

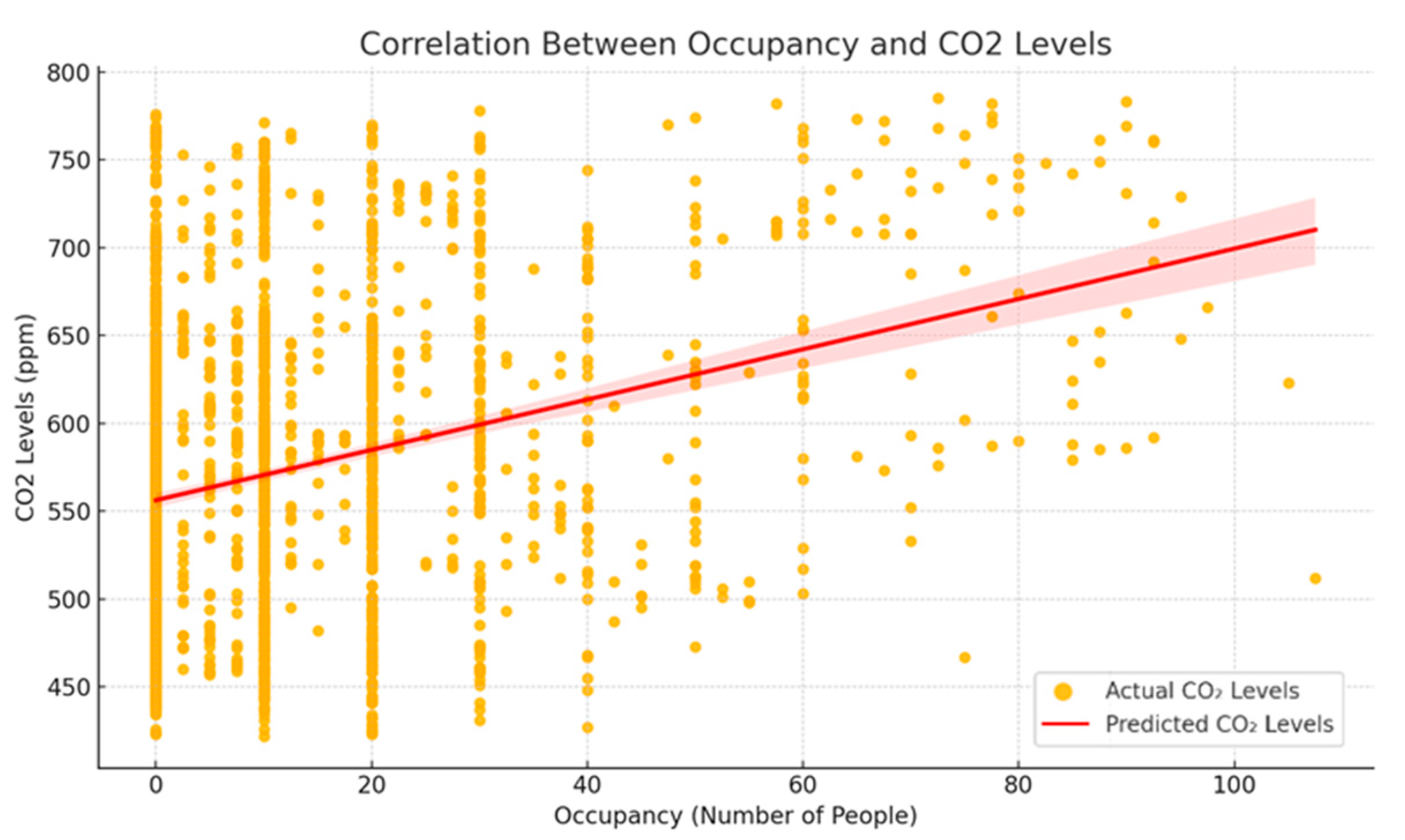

Further validating the practical utility of the proposed integration, a linear regression analysis was conducted using IoT sensor data to examine the relationship between occupancy and indoor CO₂ concentrations. Following data cleaning, normalization, and partitioning into training (80%) and testing (20%) datasets, the analysis yielded a regression coefficient of 1.4049. This indicates an approximate increase of 1.4 ppm in CO₂ concentration per additional occupant, with an intercept of 555.61 ppm.

The moderate R² value (0.0897), likely influenced by minimal operational disturbances in the relatively new building, nonetheless confirms meaningful correlations useful for practical maintenance decisions. Further data collection in older or more extensively occupied buildings could yield stronger predictive insights, as illustrate in

Figure 15. This result supports proactive HVAC adjustments, such as filter replacements or architectural modifications [

49,

50,

51]. Consequently, this BIM–IoT integration provides tangible operational benefits, particularly in managing contemporary challenges like PM2.5 accumulation, which is prevalent in older buildings requiring upgraded ventilation systems.

5.3. Cybersecurity and Data Integrity

The cybersecurity and data integrity were rigorously validated according to the NIST Cybersecurity Framework, focusing on data protection, detection, and responsive measures.

Data transmission utilized MQTT with TLS encryption and certificate-based authentication to secure IoT data. MongoDB storage featured encryption at rest coupled with stringent access control policies, ensuring data confidentiality and integrity. Furthermore, Node-RED workflows utilized secured HTTPS endpoints and API key-based authentication. Comprehensive configuration audits verified the effective implementation of these cybersecurity measures, confirming the reliability and robustness of the framework for practical deployment.

5.4. Comparative Validation

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed BIM–IoT integration approach, this section compares it directly against prominent limitations identified in recent studies. Four critical aspects software dependency, required expertise, added value beyond visualization, and cybersecurity are discussed, demonstrating how this research specifically addresses and improves upon these challenges.

Table 4.

Comparative Validation of the Proposed Approach against Previous Studies.

Table 4.

Comparative Validation of the Proposed Approach against Previous Studies.

| Research Aspect |

Previous Studies |

This Research |

Software

Dependency |

[52,53,54,55,56] |

Previous methods relied on commercial software, causing high recurring costs and vendor dependency. |

Employs open standards (IFC, JSON) and open-source tools (Node-RED), reducing vendor dependency and operational costs. |

Expertise

Requirements |

[52,53,54,55,56] |

Most existing methods required personnel with combined high-level expertise in both BIM modeling and programming, limiting practical usability and implementation.. |

Clearly defines and separates roles (BIM modeling, data integration, facility management), reducing combined skillset requirements. |

Value Beyond

Visualization |

[6,52,53,56,57,58] |

Limited to real-time visualization. |

Demonstrates benefits of integrating real-time IoT data with BIM for advanced maintenance analytics. |

Cybersecurity

Considerations |

[6,41,53,54,56,57,58] |

Rarely addressed cybersecurity explicitly, potentially increasing risks of data breaches or system vulnerabilities. |

Concern, employs security protocols (TLS encryption, certificate-based authentication). |

The comparative analysis shows that the proposed BIM–IoT framework addresses key limitations from previous studies. Using open standards and low-code tools reduces software dependency and ongoing costs. Clearly defined roles simplify expertise requirements, enhancing practical adoption. Integrating real-time IoT data and predictive analytics delivers benefits beyond basic visualization. Explicitly addressing cybersecurity further supports practical implementation.

6. Discussion

Existing research on BIM–IoT integration for FM mainly emphasizes monitoring and improving IEQ [

6,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58]. Despite these advances, significant limitations remain. Many approaches rely heavily on proprietary software such as Autodesk Revit and Dynamo, leading to substantial long-term operational costs [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56]. These recurring costs create hesitation among facility operators, as such investments typically do not directly contribute to revenue generation during the operational lifecycle.

Another barrier is the combined BIM and programming expertise traditionally expected from FM personnel. This combined expertise is rare and expensive, complicating practical implementation during the operational phase.

To address these critical industry gaps, the proposed workflow, as illustrated in

Figure 17, adopts clearly defined role separation aligned with specific expertise across the building lifecycle. Initially, BIM specialists prepare and convert IFC-based models into structured JSON files before operational handover. This ensures that BIM deliverables are immediately usable by FM personnel, significantly reducing complexity. During operations, IT personnel employ low-code platforms such as Node-RED, HTML, and JavaScript to integrate and visualize real-time IoT sensor data. FM staff can then apply their domain-specific expertise without needing extensive BIM or programming training, effectively bridging the BIM–FM skills gap.

Moreover, previous studies frequently limit their scope to real-time visualization without clearly demonstrating additional value beyond traditional BMS capabilities [

6,

52,

53,

56,

57,

58]. In contrast, this study integrates real-time IoT data with predictive analytics, moving beyond mere visualization. Leveraging ML techniques provides tangible operational benefits through predictive maintenance, clearly justifying the additional investment and facilitating proactive decision-making by FM teams.

Cybersecurity remains another critical yet underrepresented aspect in current BIM–IoT research. Given the extensive data exchange and system integration involved, explicit consideration of cybersecurity is essential. This research explicitly addresses cybersecurity using secure protocols like MQTT and TLS encryption. This explicit approach significantly enhances the reliability and practical applicability of the proposed framework.

However, the recommended approach of periodically outsourcing substantial BIM model updates might introduce potential risks, including inconsistent modeling practices. Establishing standardized guidelines or certification procedures for BIM updates is therefore essential to maintain consistency and reliability. Additionally, the proposed workflow highlights emerging professional roles that blend BIM and FM skills, underscoring the need for targeted training programs that foster these hybrid skillsets across the industry.

This research faced certain practical limitations. Firstly, direct access to real-time IoT sensor data was restricted due to data security concerns, limiting the study to periodic data exports from the BMS. Secondly, as the case study building was relatively new (construction completed in May 2022 and data collection occurred in 2024), no dedicated FM staff were available to participate actively or provide direct operational insights. Consequently, this limited the scope of operational validation, as sensor measurements primarily reflected optimal conditions without identifying significant performance issues.

7. Conclusions

This research presents a framework for integrating BIM with IoT technologies, specifically designed to enhance FM through advanced real-time IEQ monitoring and preparing data for further analysis. The study demonstrates how this integration extends beyond basic visualization, illustrating practical linkage of data for ML to support predictive maintenance. By converting IFC models into lightweight JSON format, the framework addresses interoperability challenges, facilitating seamless integration with web-based platforms.

A practical case study in an office setting validated the proposed framework. The integration utilized Node-RED, a low-code visual programming tool, which significantly improved usability and operational effectiveness through an intuitive, web-based dashboard. The study underscores the benefits of employing open standards, clearly defined roles, and careful cybersecurity considerations through trusted applications, which collectively reduce software dependency, simplify skillset requirements, and ensure data integrity, effectively overcoming limitations identified in previous research.

The analytical validation, especially the correlation and regression analysis linking occupancy and CO₂ levels with BIM data, highlights significant operational benefits, enabling proactive FM decisions applicable to contemporary issues such as PM2.5 management. Despite certain practical constraints, including restricted real-time sensor access and the recent completion of the case study building, the framework showcases substantial advantages for practical FM applications. Future research should focus on establishing standardized guidelines for bi-directional BIM updates, from BIM models to FM platforms and back, to ensure continuous and effective data utilization.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Tokyo Human Resource Fund, Tokyo Metropolitan Government, we sincerely appreciate their invaluable support.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BIM |

Building Information Modeling |

| BMS |

Building Management Systems |

| CDE |

Common Data Environment |

| CMMS |

Computerized Maintenance Management System |

| COBie |

Construction Operations Building Information Exchange |

| FM |

Facility Management |

| IAQ |

Indoor Air Quality |

| IEQ |

Indoor Environmental Quality |

| IFC |

Industry Foundation Class |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| JSON |

JavaScript Object Notation |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| XML |

Extensible Markup Language |

References

- A. S. Cespedes-Cubides and M. Jradi, “A review of building digital twins to improve energy efficiency in the building operational stage,” Dec. 01, 2024, Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- M. Deng, C. C. Menassa, and V. R. Kamat, “From BIM to digital twins: A systematic review of the evolution of intelligent building representations in the AEC-FM industry,” Journal of Information Technology in Construction, vol. 26, pp. 58–83, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. B. A. Altohami, N. A. Haron, A. H. Ales@Alias, and T. H. Law, “Investigating approaches of integrating BIM, IoT, and facility management for renovating existing buildings: A review,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 7, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Tang, D. R. Shelden, C. M. Eastman, P. Pishdad-Bozorgi, and X. Gao, “A review of building information modeling (BIM) and the internet of things (IoT) devices integration: Present status and future trends,” May 01, 2019, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- O. Hakimi, H. Liu, and O. Abudayyeh, “Digital twin-enabled smart facility management: A bibliometric review,” 2023, Higher Education Press Limited Company. [CrossRef]

- L. Chamari, E. Petrova, and P. Pauwels, “A web-based approach to BMS, BIM and IoT integration: a case study,” 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Arsiwala, F. Elghaish, and M. Zoher, “Digital twin with Machine learning for predictive monitoring of CO2 equivalent from existing buildings,” Energy Build, vol. 284, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Venkateswarlu and M. Sathiyamoorthy, “Sustainable innovations in digital twin technology: a systematic review about energy efficiency and indoor environment quality in built environment,” Front Built Environ, vol. 11, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Kučera and T. Pitner, “Semantic BMS: Allowing usage of building automation data in facility benchmarking,” Advanced Engineering Informatics, vol. 35, pp. 69–84, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Tibaut, D. Rebolj, and M. Nekrep Perc, “Interoperability requirements for automated manufacturing systems in construction,” J Intell Manuf, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 251–262, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. S. Tsay, S. Staub-French, and É. Poirier, “BIM for Facilities Management: An Investigation into the Asset Information Delivery Process and the Associated Challenges,” Applied Sciences (Switzerland), vol. 12, no. 19, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Dixit, V. Venkatraj, M. Ostadalimakhmalbaf, F. Pariafsai, and S. Lavy, “Integration of facility management and building information modeling (BIM): A review of key issues and challenges,” Facilities, vol. 37, no. 7–8, pp. 455–483, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Pavón, A. A. A. Alvarez, and M. G. Alberti, “Possibilities of bim-fm for the management of covid in public buildings,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 12, no. 23, pp. 1–21, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. H. Beach, O. F. Rana, Y. Y. Rezgui, and M. Parashar, “Cloud computing for the architecture, engineering & construction sector: Requirements, prototype & experience,” Journal of Cloud Computing, vol. 2, no. 1, 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. T. Matarneh and S. A. Hamed, “Exploring the Adoption of Building Information Modeling (BIM) in the Jordanian Construction Industry,” Journal of Architectural Engineering Technology, vol. 06, no. 01, 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Afsari, C. M. Eastman, and D. Castro-Lacouture, “JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) data serialization for IFC schema in web-based BIM data exchange,” Autom Constr, vol. 77, pp. 24–51, May 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu, O. Abudayyeh, and W. Liou, “BIM-Based Smart Facility Management: A Review of Present Research Status, Challenges, and Future Needs,” in Construction Research Congress 2020: Computer Applications - Selected Papers from the Construction Research Congress 2020, American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), 2020, pp. 1087–1095. [CrossRef]

- M. U. Khalid, M. K. Bashir, and D. Newport, “Development of a building information modelling (BIM)-based real-time data integration system using a building management system (BMS),” Building Information Modelling, Building Performance, Design and Smart Construction, pp. 93–104, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Chatsuwan, B. Manajitt, A. Masayuki Ichinose, and H. Alkhalaf, “A Review of BIM Maturity in Standards and Guidelines Across Asia,” in Proceedings of the 41st International Conference of CIB W78, 2024. Accessed: Apr. 22, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://itc.scix.net/paper/w78-2024-48.

- ISO, “Organization and digitization of information about buildings and civil engineering works, including building information modelling (BIM) — Information management using building information modelling,” 2018.

- buildingSMART, “Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) Overview.” Accessed: Nov. 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.buildingsmart.org/.

- P. Gordo-Gregorio, H. Alavi, and N. Forcada, “Decoding BIM Challenges in Facility Management Areas: A Stakeholders’ Perspective,” Buildings, vol. 15, no. 5, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Giel and R. R. A. Issa, “Framework for Evaluating the BIM Competencies of Facility Owners.,” Journal of Management in Engineering, vol. 32(1), 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Munteanu and G. Mehedintu, “THE IMPORTANCE OF FACILITY MANAGEMENT IN THE LIFE CYCLE COSTING CALCULATION,” 2016.

- Mohd Sabri, Ahmad Sekak, and Yusmady Md Junus, “Issues and Challenges of Building Information Modelling (BIM) Implementation in Facilities Management,” Built Environment Journal, vol. 21, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Abdelalim, A. Essawy, A. A. Alnaser, A. Shibeika, and A. Sherif, “Digital Trio: Integration of BIM–EIR–IoT for Facilities Management of Mega Construction Projects,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 16, no. 15, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Huang, Y. Liu, L. Huang, E. Onstein, and C. Merschbrock, “BIM and IoT data fusion: The data process model perspective,” May 01, 2023, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- A. Mannino, M. C. Dejaco, and F. Re Cecconi, “Building information modelling and internet of things integration for facility management-literature review and future needs,” Apr. 01, 2021, MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Enshassi, K. A. Al Hallaq, and B. A. Tayeh, “Limitation Factors of Building Information Modeling (BIM) Implementation,” The Open Construction & Building Technology Journal, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 189–196, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Pinti, R. Codinhoto, and S. Bonelli, “A Review of Building Information Modelling (BIM) for Facility Management (FM): Implementation in Public Organisations,” Feb. 01, 2022, MDPI. [CrossRef]

- S. Liu, B. Xie, L. Tivendal, and C. Liu, “Critical Barriers to BIM Implementation in the AEC Industry,” Int J Mark Stud, vol. 7, no. 6, p. 162, Nov. 2015. [CrossRef]

- B. Becerik-Gerber, F. Jazizadeh, N. Li, and G. Calis, “Application Areas and Data Requirements for BIM-Enabled Facilities Management,” J Constr Eng Manag, vol. 138, no. 3, pp. 431–442, Mar. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. Kassem, G. Kelly, N. Dawood, M. Serginson, and S. Lockley, “BIM in facilities management applications: A case study of a large university complex,” Built Environment Project and Asset Management, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 261–277, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- X. Gao and P. Pishdad-Bozorgi, “BIM-enabled facilities operation and maintenance: A review,” Jan. 01, 2019, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- G. B. Ozturk, “Interoperability in building information modeling for AECO/FM industry,” Autom Constr, vol. 113, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Jupp and R. Awad, “BIM-FM and Information Requirements Management: Missing Links in the AEC and FM Interface,” vol. 9, pp. 311–323, 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. J. Lovell, R. J. Davies, and D. V. L. Hunt, “Building Information Modelling Facility Management (BIM-FM),” May 01, 2024, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- P. U. Wijeratne, C. Gunarathna, R. J. Yang, P. Wu, K. Hampson, and A. Shemery, “BIM enabler for facilities management: a review of 33 cases,” International Journal of Construction Management, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 251–260, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Motawa and A. Almarshad, “A knowledge-based BIM system for building maintenance,” Autom Constr, vol. 29, pp. 173–182, Jan. 2013. [CrossRef]

- W. Chen, K. Chen, J. C. P. Cheng, Q. Wang, and V. J. L. Gan, “BIM-based framework for automatic scheduling of facility maintenance work orders,” Autom Constr, vol. 91, pp. 15–30, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Dave, A. Buda, A. Nurminen, and K. Främling, “A framework for integrating BIM and IoT through open standards,” Autom Constr, vol. 95, pp. 35–45, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Kazado, M. Kavgic, and R. Eskicioglu, “Integrating Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Sensor Technology for Facility Management,” Journal of Information Technology in Construction (ITcon), vol. 24, p. 441, 2019, [Online]. Available: http://www.itcon.org/2019/23.

- C. Quinn, A. Z. Shabestari, T. Misic, S. Gilani, M. Litoiu, and J. J. McArthur, “Building automation system - BIM integration using a linked data structure,” Autom Constr, vol. 118, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Panteli, A. Kylili, and P. A. Fokaides, “Building information modelling applications in smart buildings: From design to commissioning and beyond A critical review,” J Clean Prod, vol. 265, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Heaton, A. K. Parlikad, and J. Schooling, “Design and development of BIM models to support operations and maintenance,” Comput Ind, vol. 111, pp. 172–186, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Edirisinghe, K. A. London, P. Kalutara, and G. Aranda-Mena, “Building information modelling for facility management: Are we there yet?,” Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 1119–1154, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Kim, E. A. Poirier, and S. Staub-French, “Information commissioning: bridging the gap between digital and physical built assets,” Journal of Facilities Management, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 231–245, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Patacas, N. Dawood, and M. Kassem, “BIM for facilities management: A framework and a common data environment using open standards,” Autom Constr, vol. 120, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Jamriska, L. Morawska, and B. A. Clark, “Effect of ventilation and filtration on submicrometer particles in an indoor environment.,” Indoor Air, 2008. [CrossRef]

- O. Hänninen, G. Hoek, B. Brunekreef, and T. Yli-Tuomi, Characterization of Model Error in a Simulation of Fine Particulate Matter Exposure Distributions of the Working Age Population in Helsinki, Finland, vol. 55(7). 2005. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Montgomery, C. C. O. Reynolds, S. N. Rogak, and S. I. Green, “Financial implications of modifications to building filtration systems,” Build Environ, vol. 85, pp. 17–28, 2015. [CrossRef]

- W. Liang, G. Qiang, L. Fan, H. Zhang, Z. Ye, and S. Tang, “Automatic Indoor Thermal Comfort Monitoring Based on BIM and IoT Technology,” Buildings, vol. 14, no. 11, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Desogus, E. Quaquero, G. Rubiu, G. Gatto, and C. Perra, “Bim and iot sensors integration: A framework for consumption and indoor conditions data monitoring of existing buildings,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 8, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. C. Fialho et al., “Development of a BIM and IoT-Based Smart Lighting Maintenance System Prototype for Universities’ FM Sector,” Buildings, vol. 12, no. 2, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Kanna, K. AIT Lachguer, and R. Yaagoubi, “MyComfort: An integration of BIM-IoT-machine learning for optimizing indoor thermal comfort based on user experience,” Energy Build, vol. 277, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Chang, R. J. Dzeng, and Y. J. Wu, “An automated IoT visualization BIM platform for decision support in facilities management,” Applied Sciences (Switzerland), vol. 8, no. 7, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Kang, J. Lin, and J. Zhang, “BIM- and IoT-based monitoring framework for building performance management,” Journal of Structural Integrity and Maintenance, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 254–261, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. D. Eneyew, M. A. M. Capretz, and G. T. Bitsuamlak, “Toward Smart-Building Digital Twins: BIM and IoT Data Integration,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 130487–130506, 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).