1. Introduction

Ruminants represent the major domestic herbivores and play a key role in global food security [

1], because can transform large quantities of non-edible biomass into high-nutritive food products (e.g., meat and milk) without competing for land with crop production [

2]. Meat and milk from ruminants account for 16 and 8% of global protein and energy consumption, respectively [

1].

In South America, the Chaco region is a woodland ecosystem that supports more than 5 million beef cattle [

3,

4], among other ruminants [

5] underscoring its significant contribution to global food security. Cattle production in this region is predominantly based on grassland systems, where natural grasslands and exotic grasses coexist with tropical forests [

3]. However, the availability and quality of grasses fluctuate significantly due to variable precipitation during the warm season (October to March), with the lowest forage quality and availability typically occurring during the winter [

3,

4,

6]. In this context, the consumption of forest foliage by cattle has been recognized as a beneficial strategy to improve crude protein (CP) supply and overall diet digestibility [

7]. Despite this, knowledge about the nutritional value of forest foliage in the Chaco remains limited. A recent review highlighted that foliage from tropical trees and shrubs may contain substantial levels of CP [

8]. However, the binding of CP to fiber fractions can reduce its availability to ruminants. Moreover, foliage from tropical tree and shrub species can contain secondary metabolites, such as tannins, which may further limit nutrient utilization in ruminants.

Tannins are polyphenolic compounds capable of forming complexes mainly with proteins, but also with carbohydrates, thereby reducing their ruminal degradability [

9,

10]. They have also been recognized for their positive modulation of ruminal fermentation, including the inhibition of methanogenesis, making them potential key metabolites for reducing enteric methane emissions in ruminants [

9,

11,

12]. In plants, tannin concentrations are highly variable and influenced by both biotic and abiotic stresses, as well as by plant organs and species [

13]. This variability is particularly relevant in regions such as the Chaco, where a high diversity of plant species exists under heterogeneous climatic conditions. As a result, there is a knowledge gap regarding the tannin concentrations in foliage from native tree species and their potential effects on ruminal fermentation. Furthermore, a knowledge gap exists regarding the protein fractionation of these foliages and the effect of tannins on the potential utilization of their protein.

Consequently, the objective of this study was to evaluate the in vitro ruminal fermentation and N degradation parameters of foliage from five native tree species of the Chaco region, and to assess how these responses are influenced by tree species and tannin content.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sampling

The foliage samples were collected from the Fortín Delgado area, Presidente Hayes Department, Paraguay (24°25'48"S 59°15'44"W). This area lies at the transition between the subtropical Humid and Dry Chaco ecoregions, with an annual total rainfall of 951.6 mm and an average temperature of 22.4 °C [

14]. The samples were taken from a previous observational study, in which the relative frequency of selected foliage species was recorded from 09:00 to 12:00 h, over a 7-day period in November 2022 (unpublished data). Observations were conducted on a herd of goats browsing within a 20-hectare area consisting of native forest and associated forage species such as

Panicum maximum,

Digitaria decumbens, and

Cynodon nlemfuensis. In that study, 18 trees and shrubs species were identified, and the five most frequently browsed species by the goat herd were selected for this study: leaves and twigs of

Prosopis affinis (PA); leaves, twigs, and fruits of

Prosopis nigra (PN); leaves and twigs of

Acacia polyphylla (AP); leaves and fruits of

Phyllostylon rhamnoides (PR); and leaves of

Tabebuia nodosa (TN). Foliage from each tree species was randomly collected from five individual trees and then mixed into a composite sample.

2.2. Chemical Analysis

The composite samples of foliage were dried in a forced-air oven at 55°C for 72 hours, weighed, and ground to pass a 2 mm screen. Total dry matter (DM) content was determined by oven drying at 110 °C for 24 h. Ash was determined by combustion at 600 °C for 3 h and OM by mass difference. Total N was assayed by the Kjeldahl method [

15] and CP was calculated by multiplying N content by 6.25. The neutral (NDF) and acid (ADF) detergent fiber analyses included ash and were based on the procedures described by Mertens (2002) [

16] and AOAC (1997) [

15], respectively, except that samples were weighed in polyester filter bags (porosity of 16 μm) and treated with neutral or acid detergent in an autoclave at 110 °C for 40 min [

17]. For sulphuric-acid lignin (ADL) analysis, the bags containing residual ADF were treated with H

2SO

4 12 M for 3 h [

15]. Analyses of neutral detergent insoluble N (NDIN) and acid detergent insoluble N (ADIN) were performed according to Licitra et al. [

18]. Ether extract (EE) concentration was determined according to the Soxhlet method using diethyl ether as solvent [

19]. The content of non-fiber carbohydrates (NFC, %) was calculated as: 100 - [(NDF - NDIN × 6.25) + CP + EE + Ash]. Total tannin was analyzed by the Folin–Ciocalteau method, following the procedures of Makkar [

20]. The chemical composition and N fractions of evaluated foliage are presented in

Table 1.

2.3. In Situ Digestibility Assay

The in situ performed in three consecutive runs which were considered as a replicate. The samples of foliage grounded at 2 mm were weighed (1.0 g) in polyester filter bags (5 × 5 cm, 41 µm of porosity) and incubated in the rumen of a cannulated cow for 48 h. The cow was grazing a native grassland (main species composition:

Sorghastrum setosum,

Paspalum sp.,

Steinchisma sp.,

Panicum sp.,

Eleocharis sp.,

Rynchospora sp., and

Cyperus sp.), and was supplemented with 2 kg DM of a commercial concentrate composed by corn grain, rice bran and soybean expeller (12 % CP). Thereafter rumen incubation, the bags were treated with neutral detergent solution in an autoclave at 110°C for 40 min [

17], washed in tap water, oven dried at 110°C for 24 h, and ashed at 600 °C for 3 h. The OMD was calculated as: (incubated OM (g) – residual OM (g))/incubated OM. Digestible organic matter content (DOM) was calculated as the product of sample OM content and OMD. The digestible energy (DE, Mcal/kg DM) was calculated as: DOM (g/kg) × 4.409)/1000, and the metabolizable energy (ME, Mcal/kg DM) was calculated as: DE × 0.82 [

21].

2.4. In Vitro Gas Production Assay

Samples of foliage grounded at 1 mm were weighed (0.5 g) into 100 mL glass bottles. To evaluate the effect of tannins on gas production parameters, each foliage sample was incubated with 1 or 0 g of PEG (molecular weight = 6,000 g/mol), a tannin-binding agent [

22]. Subsequently, 40 mL of a buffer solution [

23] was added, and then kept refrigerated at 4°C for 12 h to allow substrate hydration. After that, the bottles were put in a water bath at 39ºC and 10 mL of ruminal inoculum was added. The inoculum was collected from the rumen of a canulated steer grazing a Tifton (

Cynodon dactylon) pasture and receiving supplementation with 2 kg of DM/d of a commercial concentrate composed by corn grain, rice bran and soybean expeller (12 % CP). All procedures were performed under continuous CO

2 injection. Three in vitro runs were conducted, and each run was considered as a replicate. In each run, samples with or without PEG were incubated in duplicate, along with four additional blank bottles with or without PEG, totaling 24 bottles per run. Gas production was recorded at 12, 24, 36, 48 and 72 h using a system of graduated column [

24]. The cumulative gas production was expressed in mL per g of incubated OM and the fractional rate of gas production was estimated using the unicompartmental model proposed by Schofield et al. [

25]:

were, Vf = final volume of gas (ml/g OM) at time t; S = fractional rate of gas production (/ h); L = colonization time of the bacteria on the substrate (in hours).

2.5. In Vitro Nitrogen Degradability Assay

Samples used in the in vitro assay were previously solubilized with distilled water. Briefly, 10 g of sample (grounded at 2 mm) was weighed into a 10 x 10 cm polyester bag (41 µ porosity) and incubated in distilled water at room temperature for 3 h. Following, the samples were washed with distilled water and dried at 55 °C for 48 h. The water-insoluble fraction of samples was analyzed for DM, OM, N and tannins using the same procedures described above. Soluble N was calculated as the difference between sample N and water-insoluble N. Potentially degradable N was calculated as the difference between total N minus soluble N and ADIN.

Three in vitro runs were conducted for each foliage, and each run was considered as a replicate. For this purpose, water-insoluble residues were weighed (0.5 g) into 100 mL glass bottles. To evaluate the effect of tannins on N degradation, each foliage sample was incubated with 1 or 0 g of polyethylene glycol (PEG; molecular weight = 8,000 g/mol). Subsequently, 40 mL of a modified buffer solution [

23], containing a reduced concentration of ammonium bicarbonate (i.e., 0.293 g NH

4HCO

3/L), was added, and then kept refrigerated at 4°C for 12 h to allow substrate hydration. After that, the bottles were put in a water bath at 39ºC and 10 mL of ruminal inoculum was added. The inoculum was collected before the morning feeding (≈ 9 am) from the rumen of the same cow used for the in situ digestibility assay. All procedures were performed under continuous CO

2 injection. In each run, samples with or without PEG were incubated in triplicates, and four additional blank bottles without sample were also incubated. Thus, 34 bottles were incubated in each run.

Gas production was monitored at 0, 6, 12, 18, 24, 36, 48, and 72 h using a graduated column system [

24]. After each gas record, a 0.5-mL aliquot of the fluid was collected from each bottle using a syringe, and this fraction was mixed with 4.5 mL of acid solution (2% H

2SO

4, v/v), and frozen at -20°C until further analysis. The samples of fluid were thawed at room temperature, centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 20 min, and analyzed for ammonia-N through the phenol-hypochlorite method [

26]. The total amount of ammonia in the bottle was calculated by multiplying the ammonia concentration by the volume of the incubation medium. The ammonia-N release at each time was calculated in proportion of the incubated potentially degradable N, by discounting the NIDA fraction. In vitro fractional rate of ammonia-N release (in vitro

kd) was determined directly as the slope obtained by linear regression of natural logarithms of undegraded N and time [

27]. The soluble N (SN) fraction was obtained as the difference between the content of N in the original sample minus the content of N in the water-insoluble fraction. The potentially degradable N (PDN) fraction was obtained as the difference between the content of N in the original sample minus the content of SN and ADIN. The effective N degradability (END) of feedstuffs incubated in vitro was calculated applying the following equation [

28]:

where SN, PDN and

kd are the same as defined above and

kp is the fractional rate of N rumen outflow, fixed at 2, 4, and 6 %/h.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test through the NORMAL option in PROC UNIVARIATE of SAS software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The data from the in situ digestibility assay (i.e., OMD, and contents of DOM and ME) were analyzed using PROC GLM in SAS, with species as a fixed effect. The data obtained from the in vitro assays (i.e., gas production, S, kd, and END) were analyzed using the same model, with the inclusion or not of PEG in the incubation medium as fixed effect.

3. Results

Chemical composition and N fractions of the plant material is shown in

Table 1. In general, all species presented high levels of CP (≥ 17% DM) and NDF (≥ 48% DM). Foliage from PR presented high level of ash (20% DM), whereas PA, PN and AP showed the high levels of ADL (≥ 17% DM). Tannins were detected in all species, with high concentrations in PN and PA (> 4% DM), whereas the other foliage species showed low concentrations (<1% DM). Despite the high CP content, most of the N fraction was associated with fiber (≥40% of total N) in all species, with a variable proportion bound to ADF (11–29% of total N), which is considered indigestible.

3.1. In Situ Digestibility

In situ OMD, DOM, and ME of the evaluated foliage are presented in

Table 2. The foliage of PR had the highest OMD, DOM, and ME (p ≤ 0.05), followed by PA and TN, which did not differ from each other, while AP and PN showed the lowest values (p ≤ 0.05).

3.2. In Vitro Gas Production Parameters

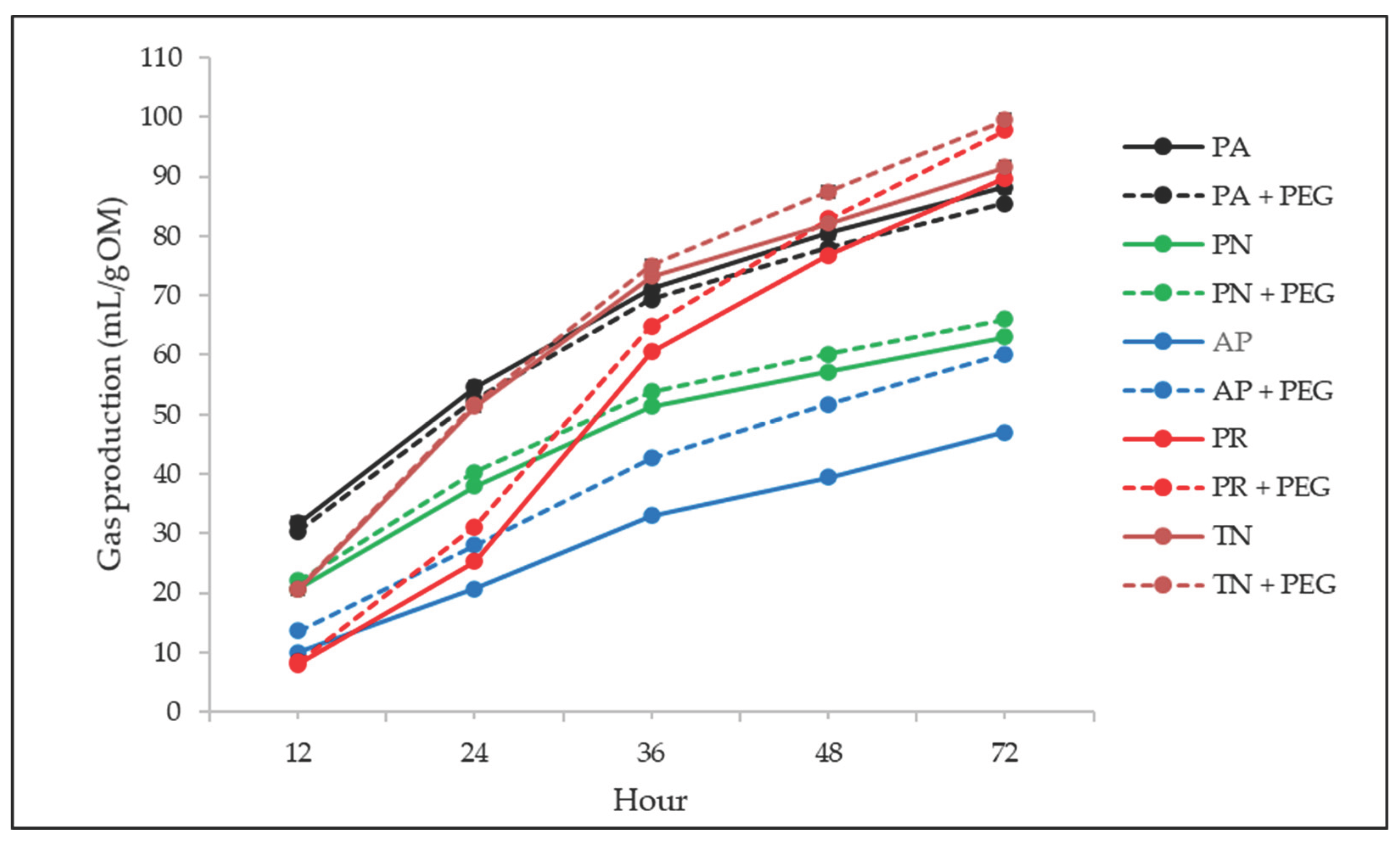

The effect of PEG on in vitro total GP and S of the evaluated foliage is presented in

Table 3 and

Figure 1. Both total GP and S were affected by tree species (p < 0.001), whereas PEG addition had no effect (p = 0.123), and no Sp × PEG interaction was detected (p ≥ 0.693). Total GP was higher (p < 0.05) in PA, PR, and TN compared to PN and AP. Similarly, S was in general higher (p < 0.05) in PR and TN than PN, AP, and PA.

3.3. In Vitro N Degradation Parameters

The effect of PEG on the in vitro

kd and the END of the evaluated foliage is presented in

Table 4. Both tree species and PEG addition affected (p < 0.01) the

kd and END, while their interaction tended to be significant for

kd (p = 0.052) and for END estimated at a rumen passage rate of 6%/h (p = 0.092). The addition of PEG to the incubation medium increased the

kd and, at rumen passage rates of 2, 4, and 6%/h, consistently increased END in PN and AP (p < 0.05), whereas no effect was observed in PA, PR, or TN.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, the specific foliage studied here have not been previously evaluated as feed for ruminants in terms of their nutritional composition, in vitro digestibility, N degradability, or the potential effects of tannins on nutrient utilization. In general, the chemical composition of evaluated foliage, falls within the range reported by Castro-Montoya and Dickhoefer (2020) [

8] for foliage from tropical tree species. The evaluated foliage presented high CP content (17–28%). However, despite the high CP content, a considerable portion of N (40–55%) was bound to NDF, and a variable fraction of N (11–29%) was indigestible (i.e., ADIN), making it unavailable for rumen microbial degradation and post-ruminal digestion, thus effectively limiting the protein availability to the animal [

18].

Despite its high ash content, PR foliage showed the highest OMD and DOM concentration, providing energy levels comparable to those of alfalfa hay (≈ 2.0 Mcal ME/kg DM; [

29]), a widely used temperate legume forage. In addition, the higher OMD was consistent with the lower ADL and tannin concentrations found in PR compared to the other evaluated foliages. In fact, a negative correlation between in vitro digestibility and ADL concentration has been reported in legume foliage, as well as in tropical trees and shrubs [

8]. Furthermore, PR was among the forages with the highest in vitro gas production and fractional rate of gas production. These parameters were not affected by the addition of PEG, suggesting that tannins do not interfere with fermentation, likely due to their low concentration in this foliage (i.e., 0.4 % DM).

Although PR shows the most promising nutritional attributes in terms of digestibility and CP content, 55% and 15% of its N were bound to NDF and ADF, respectively. In addition to its high fiber-bound N fractions, this forage also exhibited the lowest

kd among the species evaluated. Consequently, the END for PR was among the lowest observed in this study. Although END parameters are typically estimated using the in situ bag technique [

28], in our study they were estimated in vitro. Even so, regardless of the technique, the END value of PR estimated at a passage rate of 4%/h was considerably lower than that reported for alfalfa hay (i.e., 82 %; [

29]) and lower than that of fresh

Leucaena leucocephala (i.e., 51%; [

30]), a tropical shrub-tree legume. The addition of PEG to the incubation medium did not affect any N degradation parameters, suggesting that tannins did not interfere with protein degradation in this foliage.

The foliage of PA and TN presented similar nutritional attributes, although PA was high in ADL. Both forages showed low concentration of DOM; however, they exhibited gas production values similar to PR. In addition, in vitro gas parameters were not affected by the addition of PEG to the incubation medium, indicating no effect of tannins, which were found at low concentrations in both PA and TN (i.e., < 1 % DM). Also, PA had high CP levels, and although 40% of its N was bound to NDF, it showed the lowest ADIN value among the forages evaluated, which was below the average ADIN levels reported for tree foliage [

8]. Furthermore, despite the fiber-bound N, the END in this foliage was among the highest of those evaluated, presenting similar values that those reported for

Leucaena leucocephala (i.e., 51%; [

30]) a widely distributed tropical shrub-tree legume.

Despite the high CP levels found in PN and AP, these foliages showed high concentrations of ADL, which may explain the low OMD observed. In fact, they had the lowest DOM values among the forages evaluated, resulting in low energy concentrations, similar to those reported for low-quality roughages such as rice straw (i.e., 1.4 Mcal ME/kg DM; [

31]). Additionally, these forages presented high tannin concentrations, close or above the threshold (i.e., 5 % DM) generally assumed to depress DMI [

32] and in vivo digestibility [

33]. However, despite the highest tannin concentrations, no effects were observed on gas production parameters (i.e., no PEG effect). In addition, both PN and AP foliages exhibited low END values, and the addition of PEG to the incubation medium significantly increased

kd and END, indicating a marked negative effect of tannins on the ruminal N degradability of these forages.

In general, although the utilization of CP from the evaluated foliages is limited due to the high proportion of bound and indigestible N, they could still represent a valuable source of protein, particularly during the dry season or winter months, when the CP content of native or cultivated grasses is low in the Chaco region [

34].

5. Conclusions

The five native tree foliages evaluated showed high CP content, but a large proportion of N was bound to fiber, limiting its availability both in the rumen and post-ruminally. Overall, while some of these forages may have nutritional potential as protein sources for ruminants, their effective N degradability is restricted by both tannin content and fiber association. These factors should be taken into account when considering their inclusion in ruminant diets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A.P., and P.C.; methodology, M.P.C.M., A.R.A., M.E.P.H., C.M.B., O.R.M., and C.A.P.; formal analysis, M.P.C.M., C.A.P.; investigation, M.P.C.M., A.R.A., M.E.P.H., C.M.B., O.R.M., and C.A.P.; resources, M.P.C.M., C.A.P., P.C., and G.V.K.; data curation, M.P.C.M., G.V.K., and C.A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P.C.M., I.D.F., and C.A.P.; writing—review and editing, G.V.K., I.D.F., and C.A.P.; visualization, C.A.P; supervision, G.V.K., P.C., and C.A.P.; funding acquisition, M.P.C.M., and C.A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by the Consejo Federal de Ciencia y Tecnología (COFECYT, Argentina) through the project PFI-2022 (EX-2022- 83861694-APNDDYGD#MCTAl).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to institutional approval at the Centro de Investigaciones y Transferencias de Formosa, in accordance with institutional guidelines for animal care and use.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the results of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mottet, A.; Teillard, F.; Boettcher, P.; De’Besi, G.; Besbes, B. Domestic herbivores and food security: Current contribution, trends and challenges for a sustainable development. Animal 2018, 12 (Suppl. 2), s188–s198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, L.; Rowntree, J.; Windisch, W.; Waters, S.M.; Shalloo, L.; Manzano, P. Ecosystem management using livestock: Embracing diversity and respecting ecological principles. Anim. Front. 2023, 13, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, P.; Baumann, M.; Baldi, G.; Banegas, N.R.; Bravo, S.; Gasparri, N.I.; et al. Grasslands and open savannas of the Dry Chaco. In Encyclopedia of the World’s Biomes; Goldstein, M.I., DellaSala, D.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 562–576. [Google Scholar]

- Milán, M.J.; González, E. Beef–cattle ranching in the Paraguayan Chaco: Typological approach to a livestock frontier. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 5185–5210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, P.D.; Baumann, M.; Blanco, L.; Murray, F.; Nasca, J.; Piipponen, J.; et al. Improving the estimation of grazing pressure in tropical rangelands. Environ. Res. Lett. 2025, 20, 034036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasca, J.A.; Feldkamp, C.R.; Arroquy, J.I.; Colombatto, D. Efficiency and stability in subtropical beef cattle grazing systems in the northwest of Argentina. Agric. Syst. 2015, 133, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belete, S.; Tolera, A.; Betsha, S.; Dickhöfer, U. Feeding values of indigenous browse species and forage legumes for the feeding of ruminants in Ethiopia: A meta-analysis. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Montoya, M.; Dickhoefer, U. The nutritional value of tropical legume forages fed to ruminants as affected by their growth habit and fed form: A systematic review. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2020, 264, 114476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.K.; Saxena, J. Exploitation of dietary tannins to improve rumen metabolism and ruminant nutrition. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkar, H.P.S. Effects and fate of tannins in ruminant animals, adaptation to tannins, and strategies to overcome detrimental effects of feeding tannin-rich feeds. Small Rumin. Res. 2003, 49, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghorn, G. Beneficial and detrimental effects of dietary condensed tannins for sustainable sheep and goat production—Progress and challenges. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2008, 147, 116–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, L.O.; Muir, J.P.; Naumann, H.D.; Norris, A.B.; Ramírez-Restrepo, C.A.; Mertens-Talcott, S.U. Nutritional aspects of ecologically relevant phytochemicals in ruminant production. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 628445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poutaraud, A.; Michelot-Antalik, A.; Plantureux, S. Grasslands: A source of secondary metabolites for livestock health. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 6535–6553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DINAC. Anuario Climatológico 2022; Dirección Nacional Aeronáutica Civil: Paraguay, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists, 15th ed.; AOAC: Arlington, VA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, D.R. Gravimetric determination of amylase-treated neutral detergent fibre in feeds with refluxing beakers or crucibles: A collaborative study. J. AOAC Int. 2002, 85, 1217–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senger, C.C.D.; Kozloski, G.V.; Sanchez, L.M.B.; Mesquita, F.R.; Alves, T.P.; Castagnino, D.S. Evaluation of autoclave procedures for fibre analysis in forage and concentrate feedstuffs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2008, 146, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licitra, G.; Hernandez, T.M.; Van Soest, P.J. Standardization of procedures for nitrogen fractionation of ruminant feeds. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1996, 57, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiex, N.J.; Anderson, S.; Gildemeister, B. Crude fat, hexanes extraction, in feed, cereal grain, and forage (Randall/Soxtec/submersion method): Collaborative study. J. AOAC Int. 2003, 86, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makkar, H.P.S. Quantification of Tannins in Tree and Shrub Foliage: A Laboratory Manual; FAO/IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- NRC. Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle, 6th revised ed.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Makkar, H.P.S. In vitro gas methods for evaluation of feeds containing phytochemicals. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2005, 123, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mould, F.L.; Morgan, R.; Kliem, K.E.; Krystallidou, E. A review and simplification of the in vitro incubation medium. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2005, 123–124, 155–172. [Google Scholar]

- Demarco, C.F.; Paredes, F.M.G.; Pozo, C.A.; Mibach, M.; Kozloski, G.V.; de Oliveira, L.; Schmitt, E.; Rabassa, V.R.; Pino, F.A.B.D.; Corrêa, M.N.; Brauner, C.C. In vitro fermentation of diets containing sweet potato flour as a substitute for corn in diets for ruminants. Ciênc. Rural 2020, 50, e20181055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, P.; Pitt, R.E.; Pell, A.N. Kinetics of fiber digestion from in vitro gas production. J. Anim. Sci. 1994, 72, 2980–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherburn, M.W. Phenol-hypochlorite reaction for determination of ammonia. Anal. Chem. 1967, 39, 971–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, G.A. Determination of protein degradation rates using a rumen in vitro system containing inhibitors of microbial nitrogen metabolism. Br. J. Nutr. 1987, 58, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ørskov, E.R.; McDonald, I. The estimation of protein degradability in the rumen from incubation measurements weighted according to rate of passage. J. Agric. Sci. 1979, 92, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuzé, V.; Tran, G.; Boval, M.; Noblet, J.; Renaudeau, D.; Lessire, M.; Lebas, F. Alfalfa (Medicago sativa). Feedipedia. 2016. Available online: https://www.feedipedia.org/node/275 (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Heuzé, V.; Tran, G. Leucaena (Leucaena Leucocephala). Feedipedia, a Programme by INRAE, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO. 2015. Available online: https://www.feedipedia.org/node/282 (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Heuzé, V.; Tran, G. Rice straw. Feedipedia, a Programme by INRAE, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO. 2015. Available online: https://www.feedipedia.org/node/557 (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Frutos, P.; Hervás, G.; Giráldez, F.J.; Mantecón, A.R. Tannins and ruminant nutrition. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2004, 2, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayanegara, A.; Palupi, E. Condensed tannin effects on nitrogen digestion in ruminants: A meta-analysis from in vitro and in vivo studies. Media Peternak. 2010, 33, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbera, P.; Bendersky, D.; Calvi, M.; Cetrá, B.M.; Flores, A.J.; Hug, M.G.; Pellerano, L.L.; Pizzio, R.M.; Rosatti, G.; Sampedro, D.H.; Sarmiento, N.F. Cría vacuna en el NEA; Ediciones INTA: Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2018. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).