Submitted:

16 June 2023

Posted:

20 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

INTRODUCTION

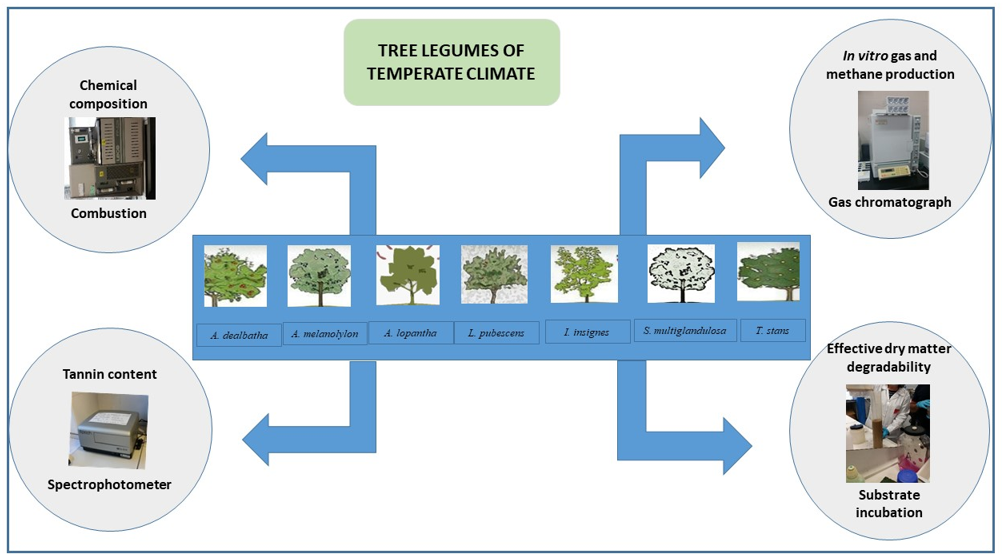

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Collection of samples.

Chemical analysis

In vitro incubations

Statistical calculations and analysis

RESULTS

Chemical composition

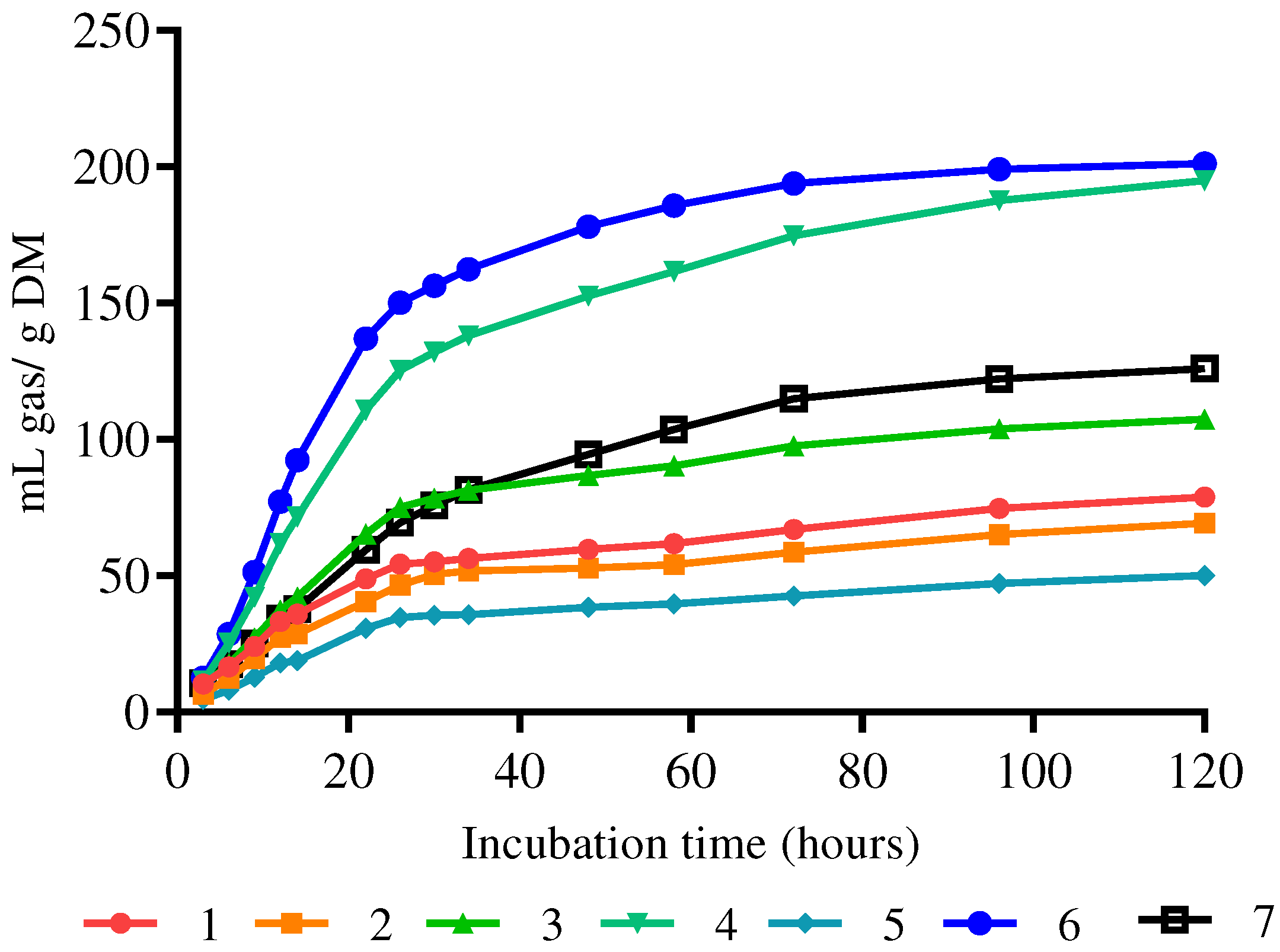

In vitro gas production and enteric methane

Volatile fatty acid profile and rumen function

DISCUSSION

CONCLUSION

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bonilla-Cárdenas J and Lemus-Flores C (2012) Enteric methane emission by ruminants and its contribution to global climate change Review. Rev Mex Cienc Pecu 3(2):215-246.

- IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) (2006). Chapter 10: Emissions resulting from livestock and manure management. In 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. Volume 4: Agriculture, forestry and other land uses. pp 10.1–10.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). (2013) Mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions in livestock production – A review of technical options for the reduction of non-CO2 gas emissions. no.177.

- Kyoto Protocol (1998) United Nations Framework Convention on climate change. United Nations.

- Ku-Vera JC, et al. (2018) Determination of methane yield in cattle fed tropical grasses as measured in open-circuit respiration chambers. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology. [CrossRef]

- Veerasamy S, Rattan L, Jeffrey L, Thaddeus E (2011) Measurement and prediction of enteric methane emission. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology.

- Animut G, Puchala R, Goetsch AL, Patra AK, Sahlu T, Varel VH, Wells J (2008) Methane emission by goats consuming diets with different levels of condensed tannins from lespedeza. Anim Feed Sci Technol 144:212–22.

- Hammond KJ, Crompton LA, Bannink A, Dijkstra J, Yáñez-Ruiz DR, O'Kiely P, Kebreab E, Eugène MA, Yu Z, Shingfield KJ, Schwarm A, Hristov AN, Reynolds CK (2016) Review of current in vivo Measurement techniques for quantifying enteric methane emissions from ruminants. Anim Feed Sci Technol 219:13–30.

- Vanegas JL, Carro MD, Alvir MR and González J (2016) Protection of sunflower seed and sunflower meal protein with malic acid and heat: effects on in vitro ruminal fermentation and methane production. J Sci Food Agriculture. [CrossRef]

- Perna Junior F, Cassiano ECO, Martins MF, Romero LAS, Zapata DCV, Pinedo LA, Marino CT, and Rodrigues PHM (2017) Effect of tannins-rich extract from Acacia mearnsii or monensin as feed additives on ruminal fermentation efficiency in cattle. Livestock Science. [CrossRef]

- Barros-Rodríguez MA, Solorio-Sánchez FJ, Sandoval-Castro CA, Ahmed AMM, Rojas-Herrera R, Briceño-Poot EG, Ku-Vera JC (2014) Effect of intake of diets containing tannins and saponins on in vitro gas production and sheep performance. Animal Production Science 54:1486-1489. https:// doi.org/10. [CrossRef]

- Soliva CR, Zeleke AB, Clément C, Hess HD, Fievez V and Kreuzer M (2008). In vitro screening of various tropical foliages, seeds, fruits and medicinal plants for low methane and high ammonia generating potentials in the rumen. Anim Feed Sci Technol.

- Muir JP, Pitman WD, Dubeux JC Jr, and Foster JL (2014) The future of warm season, tropical and subtropical forage legumes in sustainable pastures and rangelands. African Journal of Range & Forage Science, 31:3, 187-198. [CrossRef]

- AOAC (1999) Official Methods of Analysis, 16th edition, 5th revision.

- Van Soest PJ, Robertson JB and Lewis BA (1991) Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J Dairy Sci 74:3583–3597.

- Makkar HPS (2003) Effects and fate of tannins in ruminant animals, adaptation to tannins, and strategies to overcome detrimental effects of feeding tannin-rich feeds. Small Ruminant Res 49:241-256.

- Broadhurst RB and Jones WT (1978) Analysis of condensed tannins using acidified vanillin. J. Sci. J. Sci. Food Agric 29:788-794.

- Weatherburn MW (1967) Phenol–hypochlorite reaction for determination of ammonia. Anal Chem 39:971–974.

- Carro MD, Lebzien P and Rohr K (1992) Influence of yeast culture on the in vitro fermentation (Rusitec) of diets containing variable portions of concentrates. Anim Feed Sci Technol 37:209–220.

- Martínez ME, Ranilla MJ, Tejido ML, Ramos S and Carro MD (2010) The effect of the diet fed to donor sheep on in vitro methane production and ruminal fermentation of diets of variable composition. Anim Feed Sci Technol 158:126–135.

- Goering MK and Van Soest PJ (1970) Forage Fiber Analysis (Apparatus, Reagents, Procedures and Some Applications), Agricultural Handbook, n ∘ 379.

- Groot JCJ, Cone JW, Williams BA, Debersaques FMA and Lantinga EA (1996) Multiphasic analysis of gas production kinetics for in vitro fermentation of ruminant feeds. Anim Feed Sci Technol 64(1):77–89. [CrossRef]

- Molina-Alcaide E, Carro MD, Rodela MY, Weisbjerg MR, Lind V, Novoa-Garrido M (2017) In vitro rumen fermentation and methane production of different seaweed species. Anim Feed Sci Technol 228(1):1-12.

- McDonald P, Edwards RA, Greenhalgh JFD and Morgan CA (2002) Animal Nutrition. 6th ed. (Prentice Hall: Harlow, England, UK).

- Hernández-Orduño G, Torres-Acosta JFJ, Sandoval-Castro CA, Capetillo-Leal CM, Aguilar-Caballero AJ, Alonso-Díaz MA (2015) A tannin-blocking agent does not modify the preference of sheep towards tannin-containing plants.

- Bhatta R, Saravanan, M, Baruah L and Sampath KT (2012) Nutrient content, in vitro ruminal fermentation characteristics and methane reduction potential of tropical tannin-containing leaves. J Sci Food Agric. [CrossRef]

- Soltan YA, Morsy AS, Sallam SMA, Louvandini H, and Abdalla AL (2012) Comparative in vitro evaluation of forage legumes (prosopis, acacia, atriplex, and leucaena) on rumen fermentation and methanogenesis. Journal of Animal and Feed Sciences, 21:759–772.

- Oduguwa B, Olusoji A, Arigbede OM, & Adesunbola JO, & Sudekum KH (2013) Feeding potential of cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) peles ensiled with Leucaena leucocephala and Gliricidia sepium assessed with West African dwarf goats. Trop Anim Health Prod 45:1363–368.

- Archiméde H, Eugène M, Magdeleinea CM, Boval M, Martin C, Morgavib DP, Lecomtec P, Doreaub M (2011) Comparison of methane production between C3 and C4 grasses and legumes. Anim Feed Sci Technol 166–167: 59–64.

- Beauchemin KA, Kreuzer M, O'Mara F and McAllister TA (2008) Nutritional management for enteric methane abatement: a review, Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture 48:21–27.

- Gunjan G and Makkar HPS (2012) Methane mitigation from ruminants using tannins and saponins Trop Anim Health Prod 44:729–739.

- Tavendale MH, Meagher LP, Pacheco D, Walker N, Attwood GT and Sivakumaran S (2005) Methane production from in vitro rumen incubations with Lotus pedunculatus and Medicago sativa, and effects of extractable condensed tannin fractions on methanogenesis, Anim Feed Sci Technol, 123 –124:403–419.

- Jayanegara A, Leiber F and Kreuzer M (2011) Meta-analysis of the relationship between dietary tannin level and methane formation in ruminants from in vivo and in vitro experiments, Journal of Animal physiology and Animal nutrition. [CrossRef]

- McSweeney CS, Palmer B, McNeil DM, et al., 2001. Microbial interactions with tannins: nutritional consequences for ruminants, Anim Feed Sci Technol, 91, 83–93.

- Pellikaan WF, Stringano E, Leenaars J, Bongers D, Van Laar-van Schuppen S, Plant J, Mueller-Harvey I (2011) Evaluating effects of tannins on extent and rate of in vitro gas and CH4 production using an automated pressure evaluation system (APES). Anim Feed Sci Technol 166–167: 377–390.

- Blümmel, M, Makkar HPS, Becker K (1997) In vitro gas production: A technique revisited Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition 77 (1):24-34.

- Galindo J, Marrero Y, Ruiz TE, González N, Díaz A, Aldama AI, Moreira O, Hernández JL, Torres V and Sarduy L (2009) Effect of a multiple mixture of herbaceous legumes and Leucaena leucocephala on the microbial population and fermentative products in the rumen of Zebu upgraded yearling steers. Cuban Journal of Agricultural Science. 43:251-257.

- Barros-Rodríguez MA, Solorio-Sánchez FJ, Sandoval-Castro CA, Klieve A, Rojas-Herrera RA, Briceño-Poot EG and Ku-Vera JC (2015) Rumen function in vivo and in vitro in sheep fed Leucaena leucocephala Trop Anim Health Prod. [CrossRef]

- Bhatta R, Saravanan M, Baruah L and Prasad CS (2015) Effects of graded levels of tannin-containing tropical tree leaves on in vitro rumen fermentation, total protozoa and methane production..Journal of applied microbiology 118:557-564. [CrossRef]

| Item | Acacia dealbatha | Acacia melanoxylon | Albizzia lophanta | Lupinus pubescens | Inga insignis |

Senna multi glandular |

Tecoma stans |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS 1 | 484.00 | 484.74 | 457.23 | 245.64 | 497.00 | 336.64 | 346.66 |

| MO | 933.12 | 934.92 | 934.94 | 910.56 | 908.00 | 846.75 | 926.63 |

| ASHES | 66.93 | 65.18 | 65.13 | 89.58 | 92.00 | 153.38 | 73.46 |

| CP | 162.32 | 134.66 | 141.87 | 238.45 | 176.85 | 162.95 | 165.37 |

| PC-FAD(%) | 34.86 | 32.79 | 21.98 | 4.13 | 40.43 | 4.64 | 53.28 |

| NDF | 519.88 | 573.45 | 329 | 402.94 | 647.65 | 275.92 | 492.68 |

| FAD | 408.64 | 406.90 | 242.33 | 221.15 | 518.86 | 198.25 | 368.00 |

| LAD | 285.00 | 252.25 | 145.54 | 72.29 | 311.29 | 117.12 | 229.47 |

| LAD/FAD(%) | 69.74 | 61.99 | 60.05 | 32.77 | 59.99 | 59.19 | 62.43 |

| TF2 ( %) | 2.32 | 1.95 | 2.94 | 1.73 | 3.76 | 1.69 | 1.19 |

| CT 3 (%) | 1.24 | 1.48 | 2.18 | 0.42 | 3.45 | 0.35 | 1.15 |

| Gas production | Methane production | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | GP | B. | c | pH | mL CH 4 /g DM 24h |

% CH 4 total 24h | |

| A .dealbatha | 84.3 d | 19.5 ab | 1.220 b | 7.23 a | 1.76 bc | 21.06 | |

| A. melanoxylon | 70.4 ed | 17.3b | 1.390 b | 7.25 a | 1.35 c | 15.56 | |

| A. lopantha | 110.4 c | 17.9 ab | 1.540ab | 7.07 b | 1.86 bc | 15.03 | |

| L. pubescens | 201.9 a | 20.3 ab | 1.540ab | 6.87 c | 4.54 a | 21.54 | |

| I. insignes | 50.7 e | 18.0 ab | 1.467ab | 7.29 a | 1.09 c | 15.98 | |

| S. multiglandulosa | 204.4 a | 15.6 b | 1.856 a | 6.82 c | 3.61 ba | 15.61 | |

| T. stans | 149.3 b | 30.5 a | 1.322 b | 7.02 b | 2.56 abc | 18.37 | |

| EEM | 5.51 | 2.79 | 0.0949 | 0.0246 | 0.450 | 2.178 | |

| Value P | 0.0001 | 0.0243 | 0.0039 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.1982 | |

|

A. dealbatha |

A. melanoxylon |

A. lopantha |

L. pubescens |

I. insignes |

S. multi glandulosa |

T. stans |

EEM | ValueP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate | 69.77 b | 71.74 b | 70.99 b | 70.20 b | 71.36 b | 61.69 c | 75.65 a | 0.771 | 0.0001 |

| Propionate | 20.63 b | 21.53b | 22.77 b | 21.87 b | 17.45 c | 29.51 a | 16.36 c | 0.491 | 0.0001 |

| butyrate | 6.25 ba | 4.31c | 4.37 c | 5.37 bc | 7.40 a | 4.72 bc | 5.73 bc | 0.353 | 0.0001 |

| isobutyrate | 0.82 a | 0.64 a | 0.46 a | 0.60 a | 0.93 a | 0.80 a | 0.66 a | 0.116 | 0.1296 |

| isovalerate | 1.32 ba | 0.98 ba | 0.69 b | 1.11 ba | 1.65 a | 1.32 ba | 0.90 b | 0.147 | 0.0036 |

| valerate | 1.18 b | 0.80 cb | 0.70 c | 0.84 cb | 1.19 b | 1.65 a | 0.67 c | 0.098 | 0.0001 |

| A/P | 3.38 b | 3.33 b | 3.11 b | 3.20 b | 4.12 a | 2.11 c | 4.64 a | 0.117 | 0.0001 |

| N-NH3 | 133.65 | 125.12 | 115.70 | 128.53 | 161.15 | 211.53 | 109.88 | 26.199 | 0.1459 |

| EDDM4% | 339.24 ab | 363.61 a | 309.58 ab | 173.18 c | 381.28a | 232.16 bc | 272.63abc | 2.637 | 0.0001 |

| IVDDM | 748.57 ab | 686.58 ab | 661.44 b | 477.05 c | 791.46a | 469.91 c | 698.82 ab | 2.806 | 0.0001 |

| Gas production |

methane production |

ruminal function | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | N-NH3 | EDDM 4% | ||||||||

| r | P | r | P | r | P | r | P | r | P | |

| TF | -0.664 | 0.104 | -0.602 | 0.153 | 0.051 | 0.913 | 0.097 | 0.836 | 0.616 | 0.141 |

| TC | -0.813 | 0.026 | -0.796 | 0.032 | -0.093 | 0.843 | -0.143 | 0.760 | 0.781 | 0.038 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).