1. Introduction

Two-dimensional (2D) material are one of the most interesting fields of research in condensed matter physics these days. Both, theoretical and applied. The rise of graphene marks the beginning of this new era [

1]. We can cite several novel 2D materials such as graphene and its derivatives, germanene, phosphorene, hesagonal boron nitride, transition metal dichalcogenides and other 2D heterobilayers [

2]. Nevertheless, we can not forget the recently obtained ultra-high mobility systems based on GaAl. Among the different physical properties studied in those materials the electronic ones are the most important due to their impact in the future nanoelectronics, spintronics and potentially in quantum computing. Thus, it is really worth doing a thorough research study on ultra-high mobility (

) two-dimensional electron systems (2DES) and their electronic properties such as magnetotransport. Different theoretical contributions have recently shown up studying those high mobility materials [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. One of the most challenging demonstrates that 2DES under low magnetic field (

B) and temperature (

T) turn into a structure of Schrödinger cat states (SCS) [

13,

14,

15,

16], a quantum superposition of coherent states [

3] of the quantum harmonic oscillator. The initial idea of coherent states [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19] was introduced by Schrödinger [

17] describing minimum uncertainty constant-shape Gaussian wave packets of the quantum harmonic oscillator.

It is worth mentioning also that when irradiated under

B those 2DES systems give rise to the very well known phenomenon of microwave-induced resistance oscillations [

11,

12]. MIRO are one of most striking radiation-matter interactions effects discovered in the last two decades. We studied this effect based on

the microwave-driven electron orbit model [

3,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. In this model, electron orbits (electrons under

B), are driven by radiation performing a harmonic motion with the frequency of radiation. During this back and forth motion electrons suffer elastic scattering due to charged impurities. One remarkable result that we found [

3,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] is that the time it takes the scattered electron to get from the initial to the final coherent state or evolution time,

, equals the cyclotron period,

[

3]. The rest of scattering processes at different

can be ignored.

Other physical effects obtained in the dark for these materials remains to be fully explained. In this way, experimental results [

20,

21,

22] obtained with ultraclean (

) samples, show the unexpected and striking effect of an almost complete magnetoresistance collapse at low

T (

K) and low

B (

), observed under irradiation and in the dark and well-known as

giant negative magnetoresistance [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28] (GNM). Interestingly enough and observed in the same experiments, this collapse can be reversed with external parameters: with increasing

T, the set up of an in-plane

B (

) with increasing intensity too and can also be altered with the electron density (

) via an external metallic gate. In this article we present a theoretical model for this striking effect and the influence of the external physical properties and how can we make a good use of them to tune the GNM and using it to our advantage. In our theoretical approach we devise a phenomenological model to explain those experimental results. On the one hand, we are based on the quantum superposition of coherent states that give rise to SCS. Thus, the electronic structure of a ultra-high mobility 2DES would be mainly composed of SCS that oscillate with a frequency double (

) than expected considering the applied field. Under these states charged impurity scattering (elastic scattering) is seriously diminished and

drops. On the other hand we focus on the sample disorder as responsible for the cat states destruction to give rise to standard coherent states. Samples with a lower mobility (

) would have an electronic structure based on coherent states [

3] where the scattering fully take place giving rise to the

recovery.

Schrödinger cat states are fragile states that rise when coherent states associate. They turn up in 2D ultra-clean samples at low

T and

B. Another important property is that they show quantum interference at certain values of position and time where their probability density peaks (see below). However when disorder rises with increasing

T or

, SCS are gradually destroyed becoming mere coherent states. In between these two limiting situations we propose that the electronic structure of the 2D samples is made up of an ensemble of SCS and individual coherent states. The intensity of the

drop will depend on which kind of states are predominant in these ultra clean samples. At low

T or low

SCS would be prevailing. In the opposite scenario, at high

T or high

, coherent states would be majority. Thus,

T and

would be the physical properties that allow us to turn gradually and continuously a cat states-based sample into a coherent one and viceversa. Thus,

T and/or

could be used as external tuning physical properties to control the electronic structure of 2DES and make them SCS or coherent states at will. We also study the GNM as a function of the electron density and contrast to experimental results [

27]. We obtain that GNM is not as affected by

as by

T and

.

According to our model, the GNM effect itself, is explained based on two physical origins as follows. The energy difference between Landau states in SCS is

and then this turns the Landau levels involved in scattering into totally misaligned (see Figure 4). As a result, magnetoresistance based on quasi-elastic scattering plummets. This would be one of physical causes of GNM. Another reason would be that we find that the

Schrödinger cat states when involved in scattering processes undergo a destructive process that makes the scattering rate vanish, and in turn

, vanish too [

4]. The Aharonov-Bohm effect plays an essential role in the latter, transforming even Schrödinger cat states into odd ones when a phase shift of

is added [

4]. Nevertheless, there is still a remanent part of

Schrödinger cat states that would be responsible of the experimentally obtained low intensity MIRO. We conclude that ultra-high mobility 2DES under low

B and

T, are made up of a structure Schrodinger cat states and then can become a promising bosonic mode-based platform for quantum computing [

29,

30] that could be controlled by external parameters such as

T or

.

2. Theoretical Model

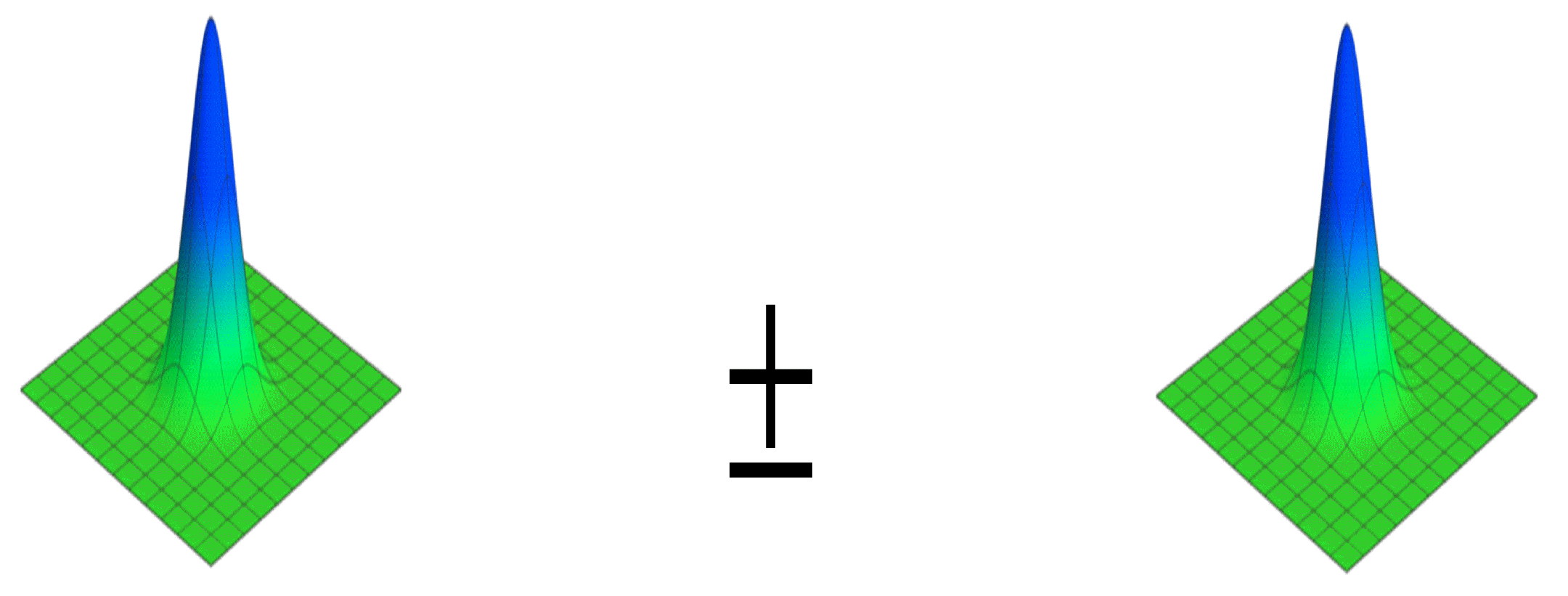

Even and odd coherent states are quantum superpositions of two coherent states of equal amplitude but separated in phase by

radians (see

Figure 1):

where

for even coherent states and

for odd coherent states. The plus sign corresponds to the even states and the minus to the odd ones. The even and odd coherent states can be obtained from the quantum harmonic oscillator ground state with the action of the even and odd displacement operators [

13],

.

and

Thus,

. The corresponding expansions of the even coherent state including the time evolution read,

and for the odd coherent state,

Thus, even coherent states are a superposition of even eigenstates of the quantum harmonic oscillator and the states energy is given by . The odd ones are superpositions of odd eigenstates and the energy is . Interestingly enough, only one every other Landau level is populated in both of them and thus the energy difference between populated levels is . This latter point turns out key to explain GNM. Yet, for genuine coherent states is .

The wave function for even and odd coherent states then reads [

13,

14,

15,

16,

19],

where

is the ground state wave function of the quantum harmonic oscillator,

is the guiding center of the quantum oscillator,

and

are the position and momentum mean values respectively [

19]:

and

where we have used that

.

For experimental values [

27],

is large (low

B) and then the coherent states

and

can be considered as macroscopically distinguishable [

13,

14,

15,

16,

19]. Thus, the two gaussian wave packets are located at macroscopically separated points. They classically oscillate with the frequency

if we consider every gaussian packet independently. Then, electrons are simultaneously localized in both spatially separated wave packets at macroscopic distances of the order of the low

B cyclotron radius (see

Figure 3). Then, the above superpositions are known as

Schrodinger cat states [

14,

15]. The normalization constants are

. These cat states are mainly used in quantum optics and have recently become relevant in quantum computing as a promising platform to implement qbits [

31].

In order to establish the physics of our theory on GNM it is essential to calculate the probability density of the wave function,

which is given by,

where the last term is responsible for the quantum interference. Thus, both types of superpositions are composed of two Gaussian wave packets oscillating (see

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) back and forth harmonically with a phase difference of

radians. When they cross, quantum interference rises. Then, acute peaks are obtained in the probability density when

and

. Thus, we expect that electron scattering, will take place mainly at these points and this is a very important point in our model. Besides, the system as a whole oscillates with double frequency,

, although every gaussian wave packet individually oscillates with

as we said above.

The longitudinal conductivity

is calculated with a semiclassical Boltzmann model [

32,

33,

34], and accordingly,

being

E the energy,

the density of initial Landau states and

is the scattering rate of electrons with charged impurities.

is at the heart of the physics of our theory explaining GNM. We obtain

by the usual tensor relationships [

5,

32,

33,

34],

, where

and

,

being the 2D electron density.

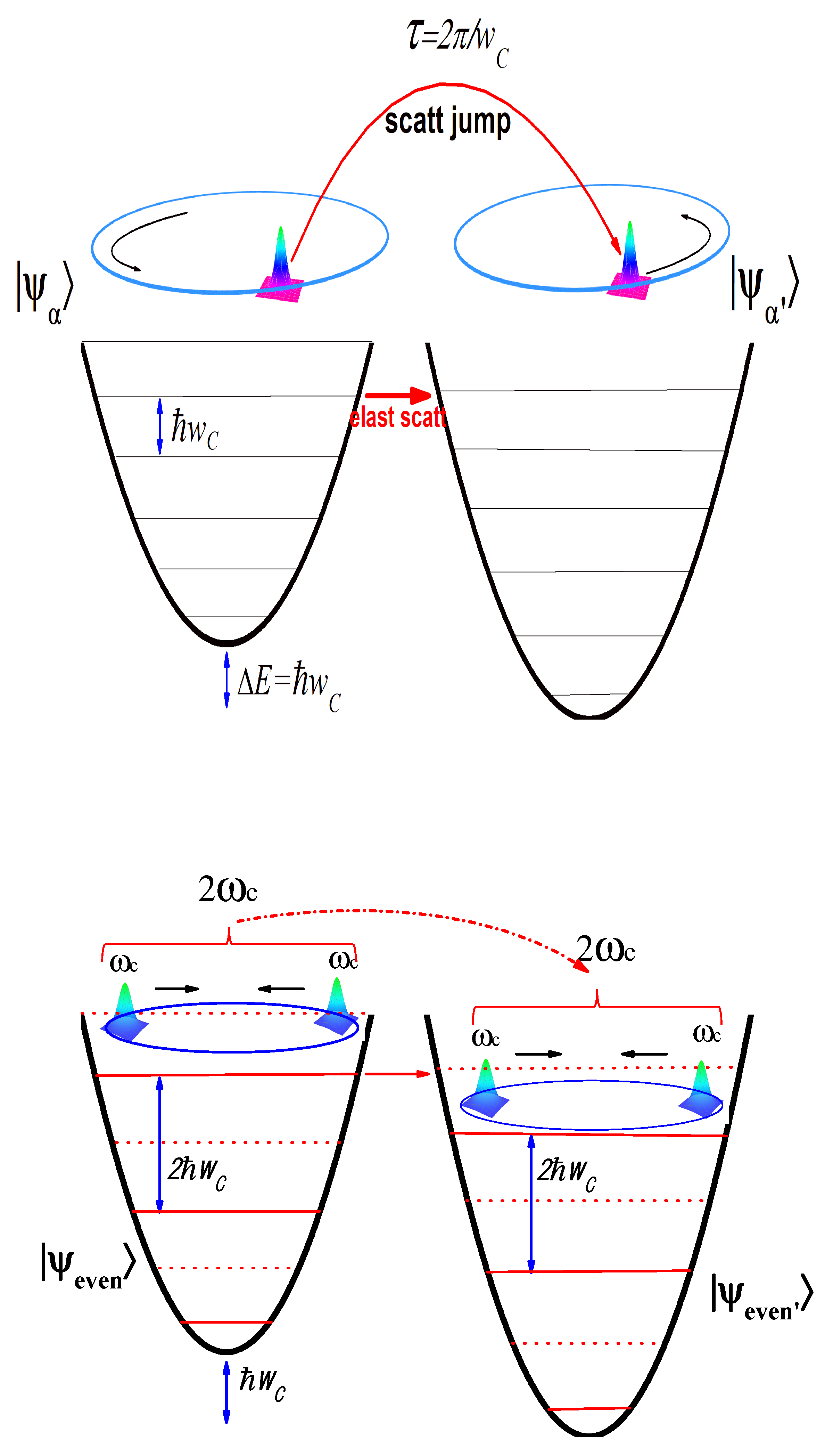

Figure 2.

Upper panel: Schematic diagram of scattering process between coherent states and . The scattering is quasi-elastic because the scattering source is based on charged impurities. The probability density for both coherent states is a constant-shaped Gaussian wave packet and the process evolution time is the cyclotron period. i.e., . Lower panel: Same for the Schrödinger cat states case.

Figure 2.

Upper panel: Schematic diagram of scattering process between coherent states and . The scattering is quasi-elastic because the scattering source is based on charged impurities. The probability density for both coherent states is a constant-shaped Gaussian wave packet and the process evolution time is the cyclotron period. i.e., . Lower panel: Same for the Schrödinger cat states case.

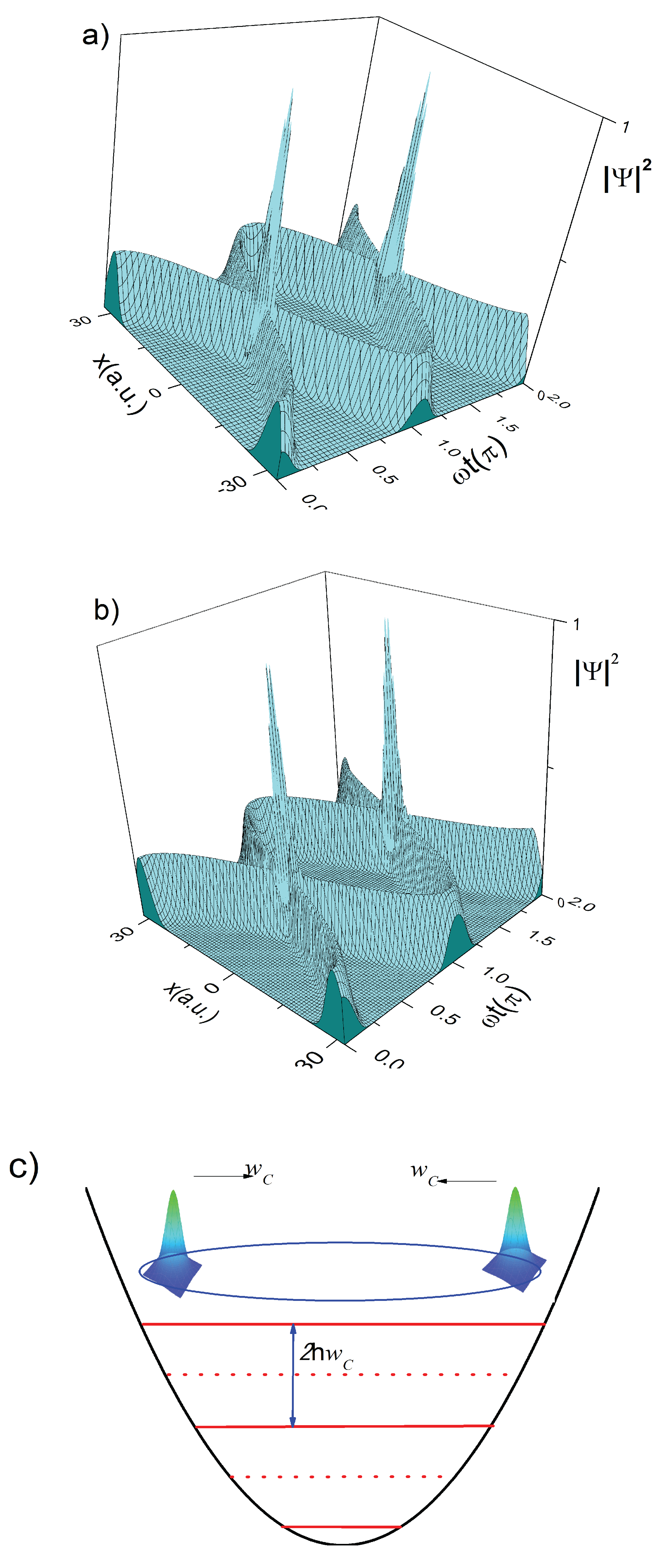

Figure 3.

a) Even coherent state probability density. Quantum interference gives rise to peaks at around

and

and

. b) Odd coherent states probability density. For both (even and odd), the probability denssity peaks at the same points. The probability densities shown are based on experimental values [

20,

21]. c) Schematic diagram for an even or odd coherent state; the two compnents of the state are harmonically oscllating under the same parabolic potential.

Figure 3.

a) Even coherent state probability density. Quantum interference gives rise to peaks at around

and

and

. b) Odd coherent states probability density. For both (even and odd), the probability denssity peaks at the same points. The probability densities shown are based on experimental values [

20,

21]. c) Schematic diagram for an even or odd coherent state; the two compnents of the state are harmonically oscllating under the same parabolic potential.

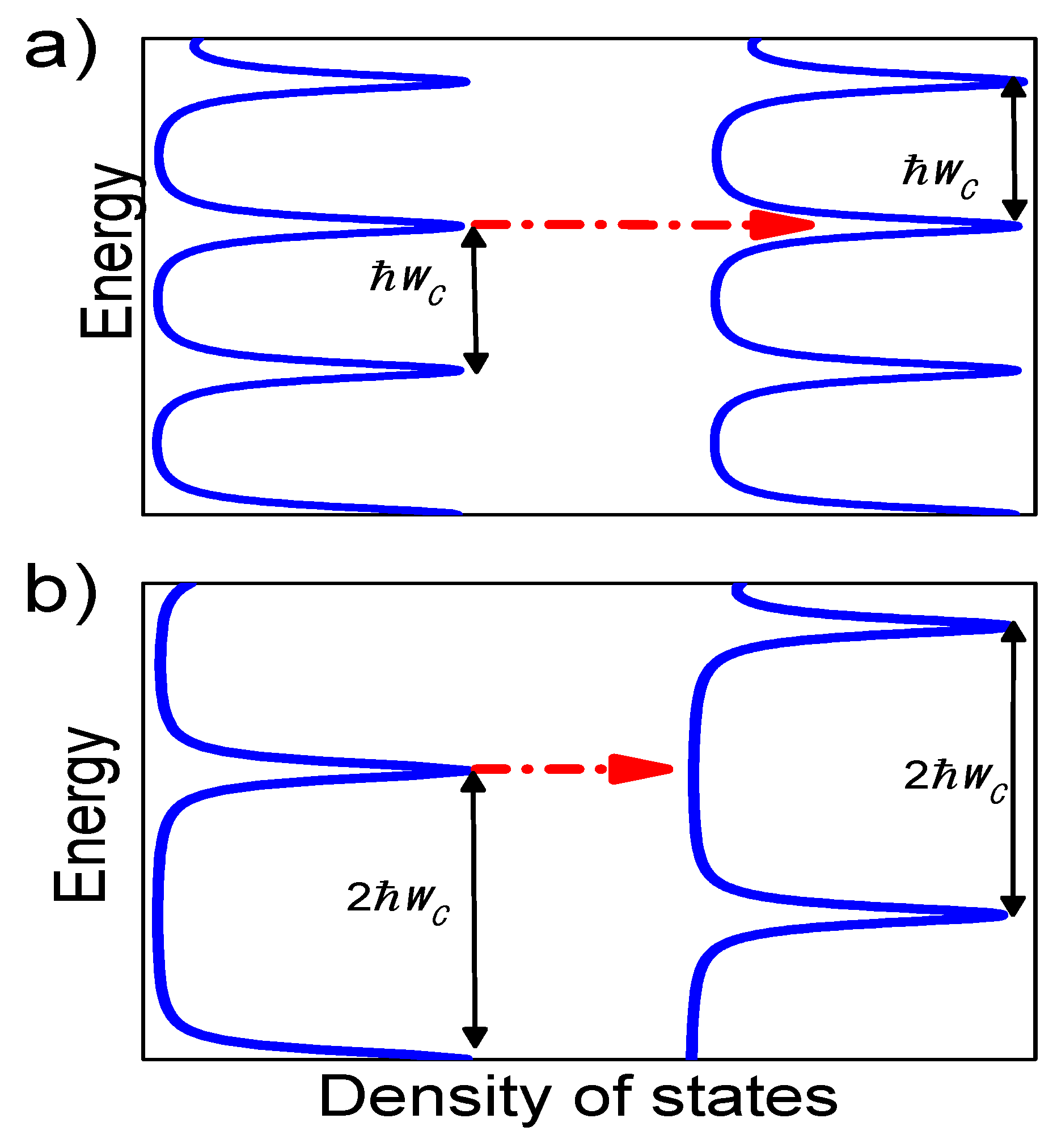

Figure 4.

Schematic diagrams representing electron-charged impurity scattering (elastic) between Landau levels. a) Case of individual coherent states. . b) Case of Schrödinger cat states. .

Figure 4.

Schematic diagrams representing electron-charged impurity scattering (elastic) between Landau levels. a) Case of individual coherent states. . b) Case of Schrödinger cat states. .

is the distance between the initial,

, and final,

, scattering-involved states guiding centers.

[

32,

33,

34] is given by the Fermi’s golden rule:

where

is the number of charged impurities,

and

are the wave functions corresponding to the initial and final cat states respectively,

is the scattering potential for charged impurities [

32,

33,

34].

, and

the

x-component of

, the electron momentum change during the scattering event. The

matrix element is given by [

32,

33,

34]:

where the scattering integral

is [

4],

where

,

and

.

t being the scattering initial time and

the final scattering time [

4]. As above, in the ± sign the

corresponds to magnetoresistance held by even Srödinger cat states and

to odd Srödinger cat states. As we said above, according to the probability density the scattering processes will take place more likely at the probability peaks. This is equivalent to having a small effective oscillation amplitude, i.e.,

and

. Thus, for instance, for the case of

we get to [

4],

Remarkably enough, due to the large value of

the above expression turns out to be negligible (real exponentials tend to zero [

3]) except when

or

. Then, the latter values act similarly as selection rules for the scattering process to take place and contribute to magnetoresistance. After lengthy algebra we get to the final expression [

4],

Thus, for the even Schrödinger cat states we obtain,

whereas for the odd ones

. We also obtain, not shown, that when one of the scattering-involved cat states, initial or final, is odd the scattering integral is zero too.

The latter results in terms of scattering integral are very important. Firstly, a good number of the scattering process that could contribute to magnetoresistance are cancelled and secondly, the remanent magnetoresistance that still persist is being held only by even SCS. The latter point explains one of the two physical reasons justifying GNM according to our model. The second is as follows.

We develop the Dirac delta in

,

as a sum of Lorentzian functions and with the use of the Poisson sum rules get to a an expression for SCS that reads [

25]:

where

is the Landau level width. Recall that the energy difference between Landau levels for a SCS is

. On the other hand, for the case of coherent states [

4,

25], where

,

In the former case (coherent states scattering) the scattering jump between initial and final Landau levels are aligned (see

Figure 5a). Thus, there are available a lot of states and a full contribution to the current and magnetoresistance. Recall that the charged impurity scattering is elastic. However for the latter case (SCS scattering) Landau levels are misaligned due to the energy difference between levels(see

Figure 5b). As a result, there are hardly final states in the scattering jump to contribute to the current. Thus, predominant presence of SCS in ultra-high mobility 2DES explains why the current plummets.

In our phenomenological model, the former expression for

corresponds to a ultrahigh mobility 2DES, i.e., mainly made up of SCS. The latter is for a lower mobility 2DES, i.e., the coherent states are predominant. In between these two scenarios we propose a general expression for

,

Where

is phenomenological

-dependent parameter which is defined below. The electron-charged impurity (elastic) scattering jump between SCS is graphically represented in the schematic diagram of

Figure 5b; the scattering is not efficient due to the lack of final states in an elastic jump. The scattering between genuine coherent states is represented in

Figure 5a; now the scattering is fully efficient in terms of available final states.

3. Results

The effect of increasing

T and

for electrons is to interact with more intensity with the lattice ions producing a stronger emission of acoustic phonons and with the subsequent

increase or Landau level widening. Following Ando et al., [

33] the acoustic phonon scattering (

) is linearly proportional to

T. Then

. This has to be reflected in a rise of

that in our model is expressed as [

25,

28]

. Where

is the LL width for

K, and

eV [

21] corresponds to the LL width of a ultrahigh mobility 2D sample. We calculate

and

according to Ando et al. [

33]. Now we define

, where

eV is the LL width for a lower mobility sample [

35] (

). In our simulations

T ranges from

K to 1 K and

K.

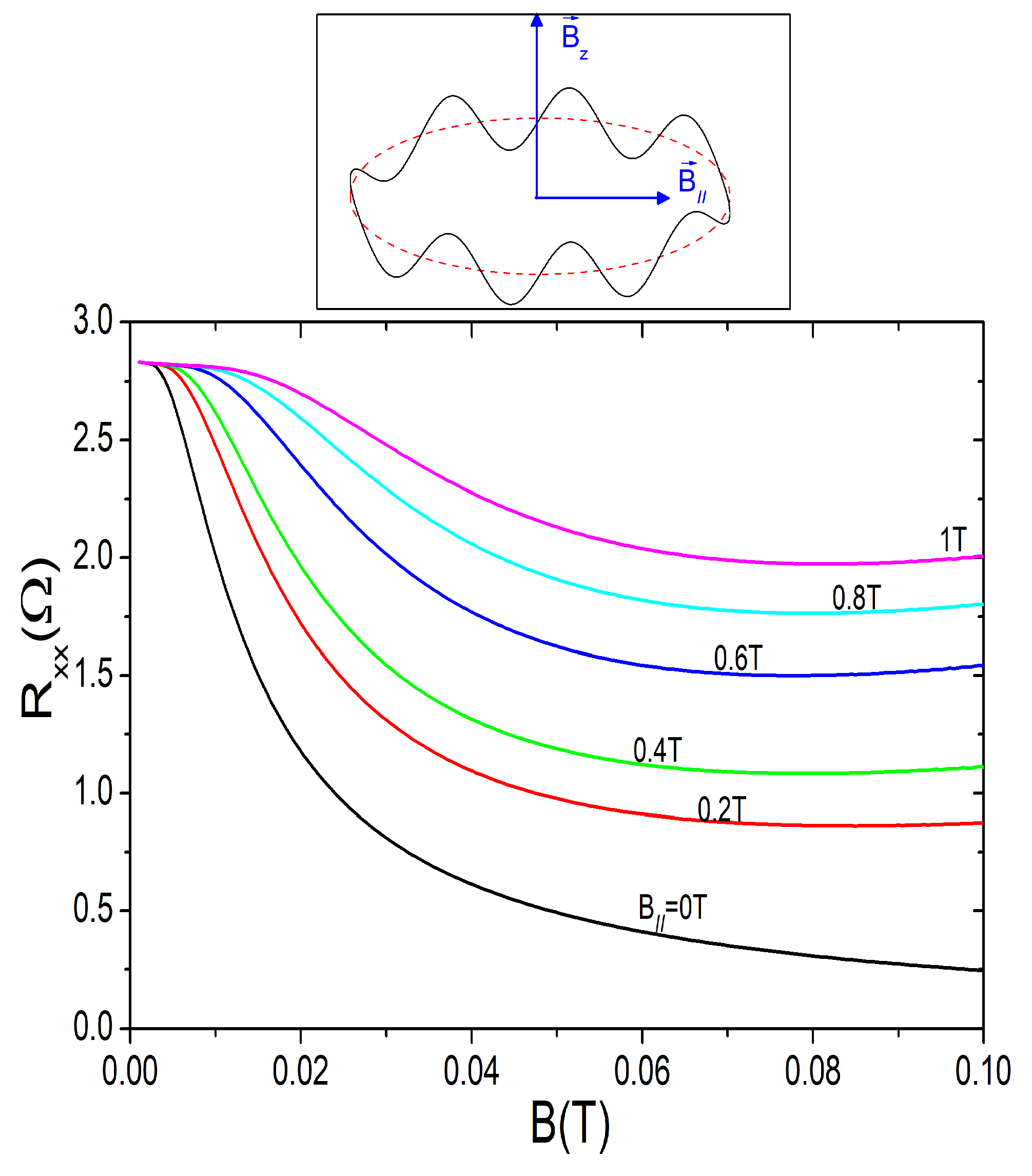

The action of

is to force an extra oscillating motion in a perpendicular direction to the main

B (see upper panel of

Figure 6). This would make stronger the interaction of the orbiting electron with the lattice ions, and similarly as with

T, emitting more acoustic phonons. Thus, the effect of a

would be to produce more disorder in the sample giving rise to an extra LL widening.

The relation between

and

is given by [

36,

37]: As we have indicated above, the presence of in-plane

B alters the electron trajectory in its orbit increasing the frequency and the number of oscillations in the

z-direction. Now the frequency of the

z-oscillating motion is

. This makes longer the electron trajectory increasing the total orbit length and eventually the damping. This increase in the orbit length is proportionally equivalent to the increase in the number of oscillations in the

z-direction. Thus, we introduce the ratio of frequencies after and before connecting

as a correction factor for the damping factor

. The final damping parameter

is:

where

is the effective length of the electron wave function when we consider a parabolic potential for the

z-confinement [

33,

37]. Now, proceeding similarly as before, the increase in LL width is,

, where in this case

.

ranges from 0. T to 1.0 T and for every case

is calculated the same as with

T.

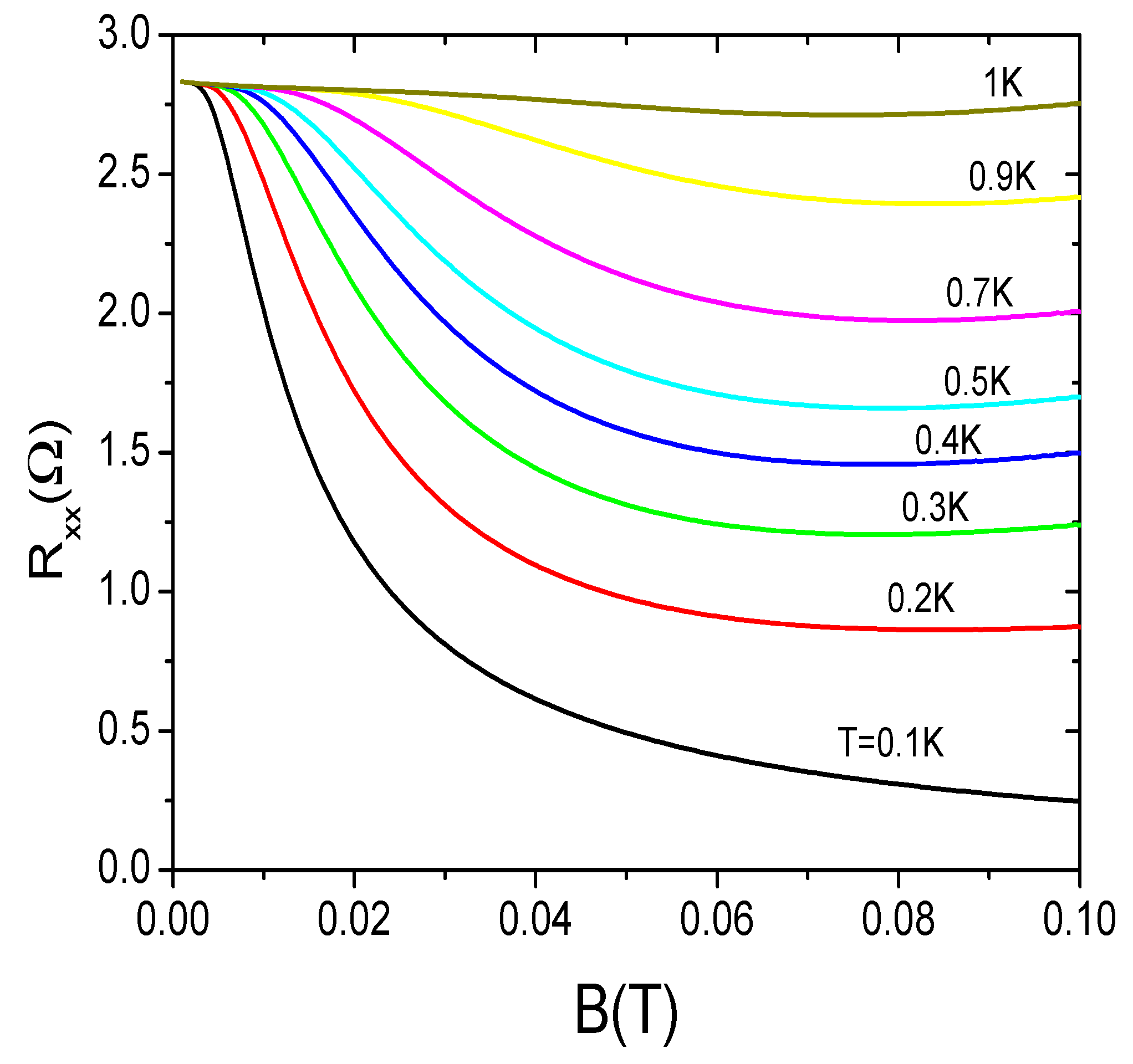

In

Figure 5, we exhibit calculated results for

vs

B in function of

T ranging from

K to 1K. At

K the curve shows a surprising strong

collapse or giant negative magnetoresistance. As

T rises, the GNM effect little by little disappears and it is totally wiped out when

K. As explained above, as

T increases, the disorder of the sample increases too and the predominant SCS are progressively destroyed to become individual coherent states. This is reflected in the model with the Dirac delta

that is gradually turned from Eq. (16) into Eq. (17), being represented in the process by Eq. (18). In the curve of

K the 2DES would be mainly made up of SCS, while in the curve of

K the 2DES would be formed by genuine coherent states. The abrupt collapse is present in the dark and under radiation. In the lower panel of

Figure 6 we present the effect of

on magnetoresistance. Here we present calculated results for

vs

B for different values of

ranging from 0T to 1T. As

increases, the effect is getting smaller and smaller and with 1T, it has nearly disappeared.

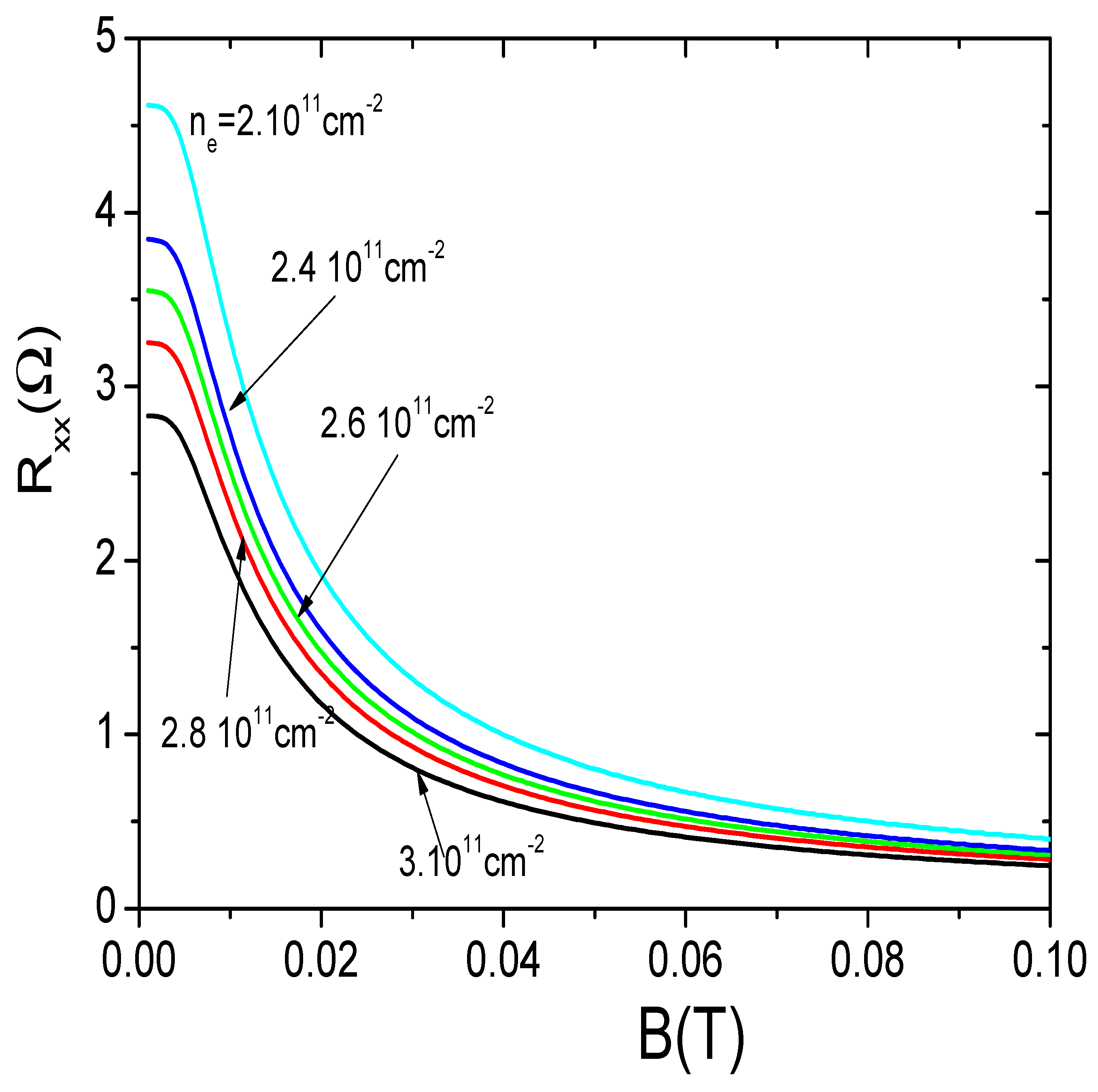

In

Figure 7 we exhibit the effect of electron density on

. The electron density goes from

cm

−2 to

cm

−2. As in experiments we obtain that the strong GNM gets more pronounced as

decreases. The explanation can ge straightforwardly from our model if we consider the tensor relations between

and

. Thus,

. The general effect is not as important as with

T and

. Thus, in our opinion,

via an external gate voltage would not be fully effective when it comes to tune the transition from SCS to coherent states in ultrahigh mobility samples.