1. Introduction

Despite decades of intense theoretical and experimental efforts, a microscopic theory of unconventional superconductivity remains elusive. The Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer (BCS) theory of superconductivity is based on the Fermi liquid model, which describes electrons as non-interacting, ballistic quasiparticles while disregarding the Coulomb interaction. In BCS theory, superconductivity is primarily determined by the pairing energy scale, which gives rise to the superconducting energy gap. Another group of theories has evolved to explain superconductivity, particularly in the field of unconventional superconductors.

For example, the concept of resonating valence bonds (RVB) suggests that electrons from neighboring atoms can create valence bonds to form pairs, which can be doped to achieve a stable superconducting ground state [

1,

2]. The RVB state is a mixture of singlet pairings of electrons at different sites arranged in a specific way. It is a distinct singlet, lacks obvious long-range order, and is fluid, exhibiting quantum transport of spin excitations. The quantum spins continuously alter their singlet partners [

1]. Strongly interacting chains of fermions are expected to display two types of collective excitations: spinons, which carry only spin, and holons, which have only charge [

3]. The low-energy excitations from the RVB states comprise these fractional quasiparticles (spinons and holons), which facilitate spin-charge separation [

3,

4].

Quantum spin fluctuations in a low-dimensional or frustrated magnet disrupt magnetic ordering while preserving spin correlations [

4]. Such fluctuations have been a central topic in magnetism due to their relevance to high-temperature superconductivity and topological states. However, despite numerous efforts, utilizing such spin states has proven to be quite challenging. Based on experimental and theoretical evidence, we know that the physical carrier of the superconductivity phenomenon is a pair of electrons (

), and the isotopic effect

, with

. To justify the experimental transport of

, Cooper tried to convert the Coulomb repulsion into attraction by using the electron-phonon interaction as a foundation.

The electron-phonon interaction produces several effects. For instance, the scattering of electrons through the emission and absorption of phonons contributes to the resistance of electric current. The polaronic effect involves a renormalization of the charge and mass of electrons as they move through the lattice of a metal. Screening via a dielectric function of the Coulomb interaction with another electron yields a repulsive positive potential, as they are charges of the same type. It is possible that Cooper based his argument on this last effect to justify the existence of correlated electron pairs mediated by electron-phonon interactions and to explain the superconductivity observed in BCS theory.

Recently, the orbital correlation effect in

- and

-electron-based solid systems has been described as a means to realize unusual forms of charge-density-wave order [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. The causes of “Cooper pairs” formation in unconventional superconductors are often elusive due to the rarity of experimental signatures that link to a specific pairing mechanism. The typical mechanism of exchange interaction between localized electrons involves the virtual hopping of electrons to neighboring sites and back, which facilitates coupling between spin orientations. When hopping occurs, the energy decreases [

11,

12].

In 2018, Riera et al introduced the Theory of correlated pairs of electrons oscillating in resonant quantum states to reach the critical temperature in a metal [

13]. Coherent, resonant excitation drives coherent oscillations in a solid-state quantum emitter, which have been described and proposed as a means to generate entangled photon pairs [

14]. Recently, the Correlated Electron Pairs at Oscillating Resonant Quantum States (CEP-ORQS) has been theoretically proven to explain the superconductivity observed in polyaromatic compounds, such as benzene, and the nitrogenous bases of DNA [

15,

16].

Neither the BCS nor the RVB theory fully explains the phenomenon of superconductivity. The BCS mechanism relies on the attraction between electrons with opposite momentum and spin, resulting from their interaction with the vibrations of the crystal lattice, known as phonons. In contrast, the RVB theory treats spin and charge as separate entities, allowing the spectrum of electronic excitations to be presented as two distinct branches: charge without spin and spin without charge. In this work, we employ elements from both approaches to clarify the CEP-ORQS, which leads to the emergence of superconducting states. We utilize the concept of orbital approximation to describe the formation of molecular clusters within solid crystals, where an external agent (such as pressure or temperature) induces hybridization between neighboring orbitals, resulting in a readjustment of the electronic configuration of those free electrons. Due to Coulomb repulsion, two electrons tend to repel each other, and by the Pauli principle, they cannot occupy the same space. As a result, an electron is compelled to seek permissible space within its corresponding orbital. The jump of this electron to a lower level not only alters its spin and sign but also emits a quantum of vibrational energy that is captured by a nearby electron, forcing it to change position. This constitutes a half-oscillation. The same phenomenon occurs during a second oscillation, forming CEP-ORQS.

For a better understanding, the paper will address the topics as follows: Section I discusses the orbital effects and the quantum geometry in solids that contribute to “molecular cluster formations”. Section II explains how elements from the BCS and RVB theories converge in the formation of CEP-ORQS. Section III expands the physical-mathematical model for the pair correlation. Finally, in section IV, we discuss our results.

SECTION I. The orbital effects in quantum geometry of solids

Three characteristics—charge, spin, and orbital—define electrons in a solid [

17,

18]. Recent studies have described the connection between orbital structure, order, and electron hopping that leads to exchange in solids. Two types of electron states exist: itinerant electrons, which align with the molecular orbital description in chemistry and are effectively represented by band theory, and localized electrons, which arise from substantial electron-electron interactions in solids (Heitler-London description) [

12,

19]. Changes in electron behavior—whether in the typical free-electron-like or band description—lead to localization at specific sites, thereby altering the properties of the systems [

20]. Regions of allowed states create energy bands, which are typically separated by forbidden areas known as energy gaps.

The weak coupling approximation, which treats a periodic potential of the lattice as a perturbation, and the tight-binding approximation are the two primary methods for describing energy bands [

21,

22]. When there is one electron per site, the material in band theory exhibits partially filled bands and behaves as a metal. Conversely, when interactions are strong enough, some bands become filled, while the upper bands, separated from the occupied ones by an energy gap, remain empty, indicating a band insulator or semiconductor [

19,

20].

In the tight-binding approximation, the bands form through the hopping of electrons between sites. Metal-insulator transitions, and vice versa, can occur due to structural changes that introduce lattice distortions, opening a gap precisely at the Fermi surface [

23]. With itinerant electrons, the metallic system displays ferromagnetic coupling, occupying different orbitals. The band of metals is typically not completely filled. The electron occupation number can change, or an electron hopping parameter could affect the system [

17,

20] (

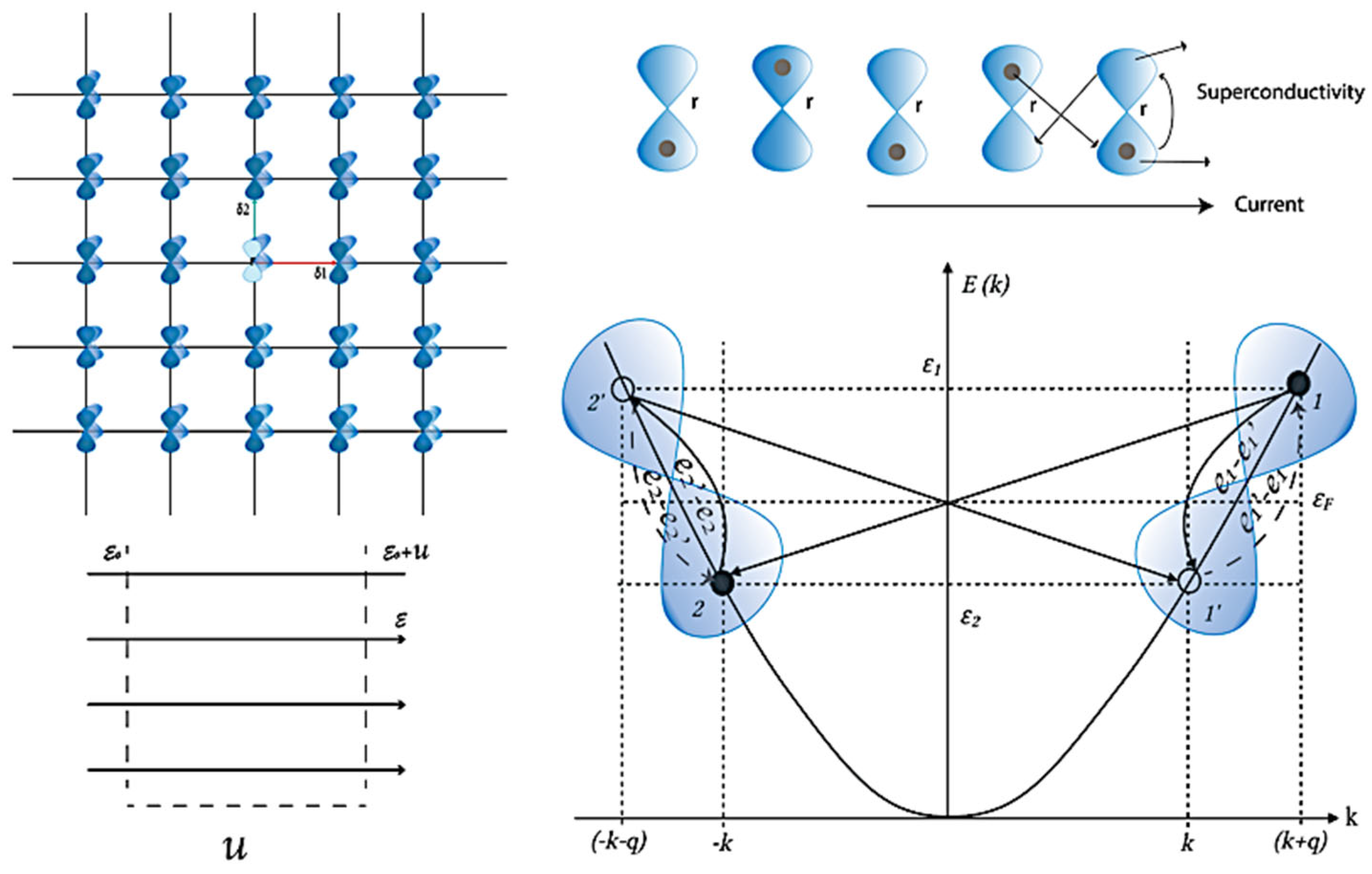

Figure 1).

The spin-orbit coupling mixes up and down spin states, producing fluctuations in molecular geometry inside the solids [

18].

SECTION II. The convergence between the BCS and RVB can be used to explain the ORQS

In natural systems, orbital degrees of freedom are essential. Certain energy levels become degenerate in isolated atoms that exhibit complete spherical symmetry. However, this degeneracy is disrupted in solids due to environmental interactions. Furthermore, space orbitals have unique directional properties [

24]. The occupancy of specific orbitals determines the final geometry of the solid [

25], primarily leading to variations in octahedral geometry due to lower symmetry [

26,

27]. The crystal field splitting results from the combination of

orbital hybridization and Coulomb repulsion [

23]. Atomic radii, the degree of covalency, and other important factors can influence crystal orbital distribution and configuration [

28].

The state of the system, where each electronic state has its distortion, is known as the vibronic state [

29]. This cooperative lattice distortion results in a specific orbital being occupied at each center [

30]. Temperature and pressure exhibit different types of structural transitions in solids [

31,

32]. The Pauli exclusion principle for parallel spins prevents this process, but antiparallel spins permit it, resulting in an energy gain [

33]. Consequently, effective electron hopping occurs between the half-filled orbitals with antiparallel spins at their centers [

12,

19]. This is well-explained by Goodenough-Kanamori rules [

34,

35,

36].

The Fourier transform of the electron-electron Coulomb interaction must be modified by the electronic dielectric function in the manner of Thomas-Fermi screening to account for the effect of other electrons in screening the interaction between a given pair:

However, the ions also screen interactions, and we should not have used the electronic dielectric constant, but rather the total dielectric constant , which considers both electrons and phonons.

We recommend replacing (1) with:

Therefore, the effect of the ions is enhanced by a correction factor that depends on the frequency and the wave vector.

BCS Theory's criterion for forming pairs is based on the same Cooper principles outlined in Equation (2.6) from Bardeen et al. (1957) [

37,

38]. An effective potential between the Coulomb repulsion and the negative electron-phonon interaction should be about

. However, no experimental evidence supports this hypothesis, as an effective potential between the Coulomb repulsion and the electron-phonon interaction does not guarantee the formation of pairs. Nevertheless, through shielding, Cooper established a negative effective potential between the electron-electron and electron-phonon interactions. In the first hypothesis, a negative potential causes the electrons to collapse due to the infinite approach. To achieve an effective negative potential, the electron-phonon interaction must exceed the Coulomb repulsion, or the energy difference between the correlated electrons must be less than the phonon energy, which is mathematically feasible but not physically realizable. One straightforward consequence is that the BCS work must articulate the commutation rules governing the creation and annihilation operators of Cooper pairs.

When computing commutators in the BCS framework, the mixed rules of fermions and bosons are derived solely from the electron creation and annihilation operators. To address this, we recommend considering that if

and

are the creation and annihilation operators of a phonon (the theory can be generalized to bosons) in the state

, and

and

are the creation and annihilation operators of an electron (the theory can be generalized to fermions of the same type) in the state

. Then, the following commutation rules must be satisfied:

Where the sign + under the bracket symbol indicates the anti-commutator.

II.1. Rules for correlation

Different conditions exist for two fermions to be correlated through phonon exchange:

The energy difference between the two fermions must equal the phonon's energy

Fermions should possess opposite momentum, but vary in the phonon's momentum.

The ORQS of the fermion pair is established when a phonon is exchanged via emission and absorption process.

The total momentum or sum of the pair of fermions is the momentum of the phonon, and the difference is.

The system must satisfy specific critical states for these conditions to be fulfilled.

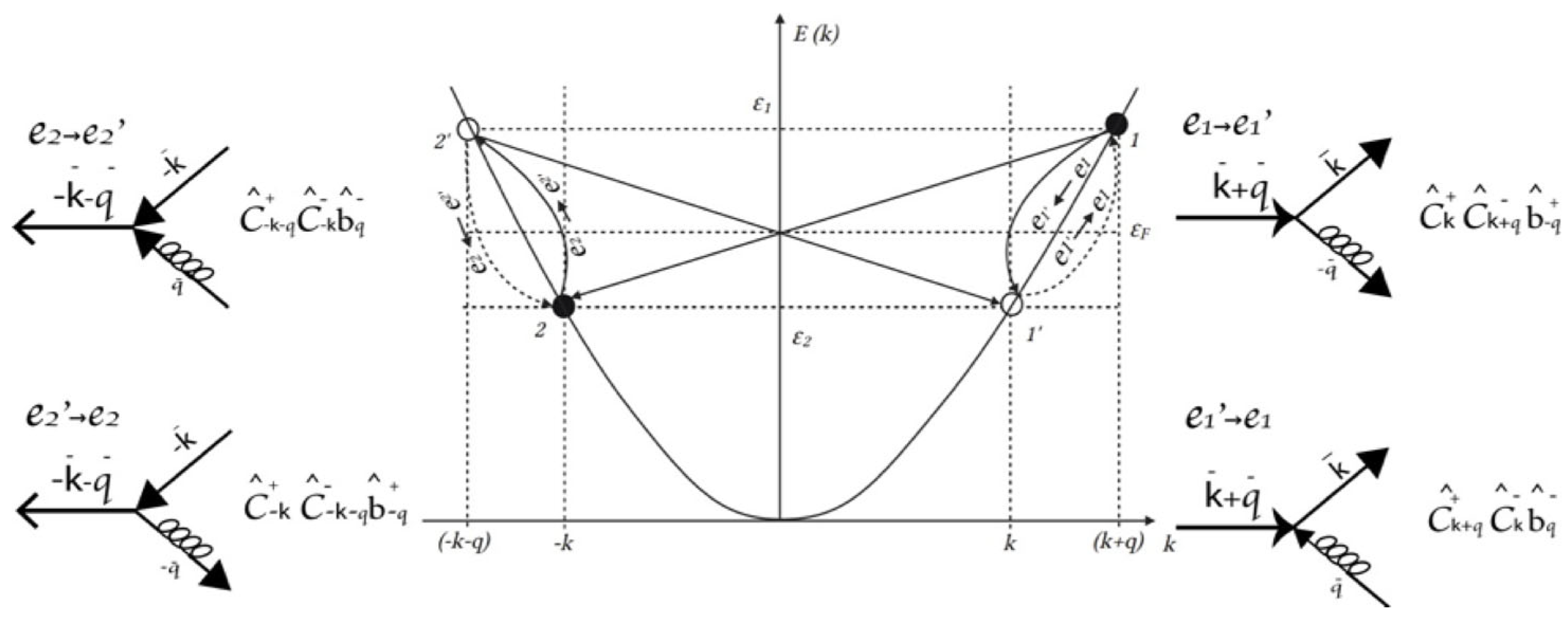

Figure 2 presents a diagram of the conduction band of a metal at the critical temperature

. The vertical axis represents energy

, which is proportional to the temperature in the region

. The horizontal axis represents the momentum

. Two electrons are initially in positions 1 and 2 with momentum

and

, respectively. There are holes at positions

and

with momentum

and

. The energy difference between the states (2 and

) and

is the energy of the phonon

. These states are symmetrically located above and below the Fermi level, indicated by the horizontal line. It coincides with the Fermi energy

.

SECTION III. The physical-mathematical model for the correlation of electron pairs in Oscillatory Resonant Quantum States.

Electrons are correlated in pairs that oscillate in ORQS by exchanging a phonon with energy

and momentum

. Two interactions are involved: the Coulomb repulsion and the electron-phonon-electron interaction. Here, electron 1 (above the Fermi surface) with momentum

and kinetic energy

correlates with electron 2 (below

) with momentum

and kinetic energy

. Moreover, the energy difference between them is exactly the energy of the phonon.

Figure 2

The energy band satisfies the following relations:

Where , , and.

However, for the ORQS, electrons tend to have equal and opposite momentum:

The total initial momentum for the ORQS 1 and 2 is:

.One phonon is absorbed by the electron in state 2. The total final momentum is

when the electron in the state 2´emits one phonon. The variation in the momentum of the electrons in the PRQS 1 and 2 is:

As we can see from (11) and (12), electrons oscillate in the ORQS, trying to match their individual momentum. They reverse the sign of the momentum between pairs of states. The sum and total difference of the electron momentum in the ORQS are equal but opposite in sign, which justifies the existence of these states. At each temperature in the range, electrons can only occupy the permitted states.

When the Coulomb repulsion (described by the potential and screened by the dielectric constant of Thomas-Fermi) is connected, electron 1 emits a phonon with momentum to electron 2 and now occupies the position of hole 1’ with momentum and kinetic energy . Meanwhile, electron 2 absorbs the phonon emitted and occupies hole 2’s position with momentumand kinetic energy. This first process defines half oscillation. The opposite happens in the second half of the oscillation. The 1’ and 2’ electrons exchange a phonon momentum and return to their original positions in 1 and 2. Note that, in the last exchange, the first electron absorbs a phonon (given by the potential). The second electron emits a phonon (given by the potential). These indicate that the potentialsand have opposite signs and are responsible for the complete static oscillation of the electrons, that is, in the absence of an external field.

At the moment when

the Hamiltonian of the system becomes

Therefore, we can say that:

Where the positive sign corresponds to for the first half oscillation and the negative sign corresponds to for the second half oscillation. We can also say that.

III.2. Internal State Characterization of the Electronic Pair in the RQS

For the calculation of the initial state of the oscillations in the RQS, the pair formed by electrons 1 and 2 with a wave function

, we apply

:

Where

is the energy corresponding to the Coulombian repulsion operator between electrons 1 and 2.

is the energy that results from the exchange of the phonon emitted by electron 1 and absorbed by electron 2. Note that the wave function

is not a self-function of the Hamiltonian

, so we apply

again to obtain the initial wave function

:

In the last equation (16), we considered that

and

. If

and

then, we obtain:

The interaction Hamiltoniandoes not have self-states of the CEP-ORQS because it only characterizes half of the oscillation of the pair. is the operator that describes the internal state of the CEP-ORQS for a complete oscillation.

It is crucial to interpret the square of the Hamiltonian as the square of the binding energy between the CEP-RQS in the range of . The participating energies are functions that depend only on the temperature and the .

The dispersion relation of the CEP-ORQS in

is:

Now, we must find the explicit dependence of the energies

on the temperature and the

. For that, we will analyze the instant at which

is reached. When

is equivalent to the room temperature, electrons are in individual states. They are correlated at

. When

the electron-electron interaction is the only participant and the total energy of the electrons depends on it. If we lower the temperature until the

, the electron-phonon-electron interaction is connected, the total energy will rely on

for each

and so:

If we consider that

has a linear temperature dependence, then, we can write:

Where is the parameter that characterizes the qualitative nature of the material to achieve the oscillations.

However, the temperature dependence is not linear

. It is more complicated because we need a potential that involves, simultaneously, the residual Coulomb repulsion and the interactions of both electrons with the phonon. That is why we propose the dependence as follows:

Now, the dispersion law that gives us the binding energy of the CEP-ORQS is:

This last equation coincides with that reported in equation (3.31) of the BCS article [

37] and Buckingham’s suggestions.

In equation (3.31) of BCS, the parameter is considered constant and equal to 3.2 for all materials. In our work, the parameter characterizes each material to undergo CEP-ORQS. If, in the previous equation, we take

, we obtain the parameter from the magnitudes that are measured experimentally:

It remains constant yet varies for each material. We refer to it as the correlation parameter (see Table 1 in [

13].

In the same way, we can calculate the highest binding energy for a metal, which represents the energy accumulated when

:

This means that as the temperature decreases from to zero, energy is accumulated as the binding energy of the pair.

In conclusion, the equation for calculating the binding energy of the pair as a function of temperature and critical temperature is:

SECTION IV. DISCUSSION

Families of strongly correlated electron materials are well established. These compounds exhibit fascinating and technologically appealing electronic properties [

2,

39]. They also possess complex phase diagrams, including both conventional and exotic phases that reveal new physics. The study of strongly correlated electron systems is currently one of the most active and exciting fields in condensed matter physics as well as in other disciplines [

40,

41].

In superconducting states, two electrons with opposite momentum attract each other, forming a bound pair. The pairing mechanism involves coupling electrons and phonons, which are quantum representations of lattice vibrations. Cooper is widely recognized as the father of two-electron correlation. He demonstrated that two electrons could pair up by considering interactions with phonons to explain superconductivity in metals. This phenomenon is also referred to as superconductivity at low critical temperatures.

Today, new compounds have emerged whose superconductivity cannot be explained by BCS [

42,

43], and they are referred to as "non-conventional" superconductors [

44]. Quantum spin liquids are systems that avoid magnetic long-range order down to absolute zero and exhibit a variety of remarkable phenomena due to an intrinsic tendency to form massive quantum superpositions of local, product-like state wavefunctions [

45,

46]. In general, the interplay between covalent bond formation, spin-orbit coupling, and intra-atomic exchange interaction is essential for analyzing the particular physical properties seen transition metal oxides [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53]. One of the most important examples of this system is the RVB state.

The RVB model explains a superposition of fluctuating singlet pairs. RVB correlations and excitations are limited to nearest neighbors. Such valence bonds can be formed between nearest-neighbor spins and between spins beyond nearest neighbors. In this paper, we propose a different interpretation of these correlations and excitations. We argue that the next-nearest-neighbor couplings and multiple-spin exchange are favored by specific geometries adopted by a material under specific conditions. For instance, doping the pure La2Cu04 in the RVB state is compensated not by a displacement of the pseudo-Fermi surface as in a conventional insulator, but by the creation of boson "hole" excitations, as long as the system remains in the RVB state. Therefore, the RVB state represents the equilibrium condition. The holes can experience Bose condensation and form a superconductor [

54].

The electronic (spin, charge, orbital) and structural degrees of freedom contribute to superconductivity. Orbital selectivity alters the band structure and affects the effective interactions, promoting pairing states [

55,

56]. Strong orbital selectivity can lead to gap anisotropy. Additionally, hybridization with neighboring orbitals supplies the holes with kinetic energy. Specifically, the

orbitals exhibit strong interlayer hopping and can form a localized spin-singlet dimer with a pair of electrons [

27].

In a single atom, the double occupation of an orbital is associated with a Coulomb repulsion term

. The kinetic energy or tunneling between orbitals of different atoms gives rise to an antiferromagnetic coupling [

20]. A crystal is a periodic arrangement of infinite atoms, so the number of atomic orbitals

is infinite. As in the case of the molecule, to build a theory of low energies, we will be left with a single

orbital per atom.

Additionally, a specific type of orbital ordering is linked to dimensionality reduction (orbital-dependent valence bond condensation) [

57]. Two and one-dimensional systems frequently exhibit unusual magnetic properties and lead to novel types of phase transitions [

57,

58,

59]. One-dimensional metallic systems can alternate between short and long bonds, showing significant and minimal inter-site hopping [

60], which creates a gap at the Fermi surface and results in a decrease in the energies of the occupied electron states. The unusual pattern of short−intermediate−long−intermediate bond alternation in solid lattices produces higher-order interaction structures and imparts extraordinary properties [

61,

62]. In such dimers, the metal-metal distance is generally shorter than the corresponding distance in the original material [

63]. The transition from a regular structure to a dimer structure under pressure has also been recorded [

64].

Dimer clusters naturally occur in some crystal structures [

65]. Orbitals directed toward neighbors may behave as delocalized, similar to molecular orbitals, while the electrons in other orbitals remain localized. In transition metals with a honeycomb lattice, electrons hopping between

orbitals create structures that remain as hexagons, a state akin to that of a benzene molecule, with the same molecular orbitals. In fact, as in benzene, six of these molecular orbitals form bands in a solid rather than levels.

Conversely, several polyaromatic hydrocarbons, such as benzene, have been identified as topological superconductors [

15,

65,

66,

67]. The

-electrons rule can be split into two pairs of

each, namely, electrons and holes with spin up and down, and can be understood as the winding number in global next-nearest-neighbor hopping [

67]. Intrinsic topological superconductors do not rely on specific external perturbations [

65]. Using the Valence-shell electron-pair repulsion (VSEPR) theory, aromaticity and superconductivity in benzene have been explained in terms of the CEP-ORQS model [

15,

16]. VSEPR theory can describe the spatial arrangement of almost all electrons. Similar to RVB, VSEPR considers orbital interactions and correlations.

2. Conclusions

Systems exhibit orbital-selective behavior, with different orbitals responding uniquely to external perturbations. In conducting solids, electrons are localized in non-hopping “fixed” orbitals, one at each lobe. Meanwhile, mobile electrons in orbitals hop from site to site, aligning their spins parallel to the spins of the localized electrons at each site. Reorganizing these spin-½ objects generates magnetic ordering and properties. For superconductivity to occur, there must be orbitals with free electrons (or lone pairs of electrons), available spaces in empty orbitals (orbital holes), and hybridized orbitals. Some systems naturally possess these characteristics (for instance, some polyaromatic hydrocarbons), while others require external modifications, such as changes in temperature (to reach the Tc) or pressure. One could hypothesize that all models of the so-called unconventional or high-temperature superconductors may contain (or be doped with) at least molecular crystals containing O2, S, or N2 molecules as structural units, as well as carbon-based materials. These elements have partially occupied orbitals with free electrons and holes, which create vacancies and allow for the freedom of movement.

Furthermore, the partial occupation is significantly easier to achieve for the shell of transition metal ions. They have outer valence electrons that shield the d electrons by forming bonds with their neighbors, which leaves the electrons weakly hybridized. This enables an efficient atomic-like intra-shell exchange interaction within a crystal.

Orbital-dependent directional hopping is proposed as a universal resource to explain superconductivity in solids. This work offers a physical-mathematical model for correlating two electrons by exchanging a boson, which operates in every equally charged fermion. The model elucidates the self-doped orbital-selective transition across valence transition-driven superconductivity. Two fermions with the same charge can only be attracted in the presence of bosons. Fermions must oscillate in specific states where total energy is conserved, and the dispersion law is quadratic. This occurs only when a certain critical state is reached. Three operators of simple particles form the operators of creation and annihilation of pairs: two fermions and one boson. The energy difference of the correlated fermion pair is equal to the energy of the boson, and the difference in the fermions’ momentum is less than that of the boson. There is always a parameter that characterizes each particular superconductor:. It represents the qualitative nature of the material to achieve oscillations.

In the BCS formalism, reducing the electronic kinetic energy at the superconducting transition would require a Bose condensation of the superconducting carriers, similar to aromaticity. However, the quantum statistics of Cooper pairs differ from those of Bose-like particles. Therefore, BCS theory and the reduction of electronic kinetic energy in the superconducting state are mutually exclusive. Einstein attempted to understand superconductivity by positing that “supercurrents are carried through closed molecular chains where electrons undergo continuous cyclic exchanges.” Although no further justification for the existence of such conduction paths was provided, this approach was based on the view that superconductivity is deeply rooted in the specific chemistry of a given material, and on the existence of a state that connects the outer electrons of an atom or molecule with those of its neighbors. This work develops a superconducting pairing mechanism based on the correlation of the same type of fermion when they exchange a boson, creating the CEP-ORQS. “The specific chemistry” is given by forming molecular structures in solids.

The electronic structure is central to understanding the physical and chemical properties of different compounds. In superconductivity, electrons cannot condense into a single state due to Pauli's principle; they are compelled to oscillate.

“Nature loves to oscillate”---Theodore Holmes Bullock

References

- Yang, K.; Phark, S.-H.; Bae, Y.; Esat, T.; Willke, P.; Ardavan, A.; Heinrich, A.J.; Lutz, C.P. Probing resonating valence bond states in artificial quantum magnets. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 993. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nascimbène, S.; Chen, Y.-A.; Atala, M.; Aidelsburger, M.; Trotzky, S.; Paredes, B.; Bloch, I. Experimental Realization of Plaquette Resonating Valence-Bond States with Ultracold Atoms in Optical Superlattices. Phys Rev Lett 2012, 108, 205301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, J.; Sompet, P.; Salomon, G.; Koepsell, J.; Hirthe, S.; Bohrdt, A.; Grusdt, F.; Bloch, I.; Gross, C. Time-resolved observation of spin-charge deconfinement in fermionic Hubbard chains. Science 2020, 367, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirobe, D.; Sato, M.; Kawamata, T.; Shiomi, Y.; Uchida, K.; Iguchi, R.; Koike, Y.; Maekawa, S.; Saitoh, E. One-dimensional spinon spin currents. Nat Phys 2017, 13, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xie, F.; Sur, S.; Hu, H.; Paschen, S.; Cano, J.; Si, Q. Emergent flat band and topological Kondo semimetal driven by orbital-selective correlations. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.-X.; Jiang, Y.-X.; Teng, X.; Hossain, M.S.; Mardanya, S.; Chang, T.-R.; Ye, Z.; Xu, G.; Denner, M.M.; Neupert, T.; Lienhard, B.; Deng, H.-B.; Setty, C.; Si, Q.; Chang, G.; Guguchia, Z.; Gao, B.; Shumiya, N.; Zhang, Q.; Cochran, T.A.; Multer, D.; Yi, M.; Dai, P.; Hasan, M.Z. Discovery of Charge Order and Corresponding Edge State in Kagome Magnet FeGe. Phys Rev Lett 2022, 129, 166401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.-X.; Yin, J.-X.; Denner, M.M.; Shumiya, N.; Ortiz, B.R.; Xu, G.; Guguchia, Z.; He, J.; Hossain, M.S.; Liu, X.; Ruff, J.; Kautzsch, L.; Zhang, S.S.; Chang, G.; Belopolski, I.; Zhang, Q.; Cochran, T.A.; Multer, D.; Litskevich, M.; Cheng, Z.-J.; Yang, X.P.; Wang, Z.; Thomale, R.; Neupert, T.; Wilson, S.D.; Hasan, M.Z. Unconventional chiral charge order in kagome superconductor KV3Sb5. Nat Mater 2021, 20, 1353–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerano, L.; Fumega, A.O.; Profeta, G.; Lado, J.L. Multicomponent Magneto-Orbital Order and Magneto-Orbitons in Monolayer VCl3. Nano Lett 2025, 25, 4825–4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macke, E.; Timrov, I.; Marzari, N.; Ciacchi, L.C. Orbital-Resolved DFT+U for Molecules and Solids. J Chem Theory Comput 2024, 20, 4824–4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.; Liu, Z.-K.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, R.; Zhu, J.-X.; Lee, J.J.; Moore, R.G.; Schmitt, F.T.; Li, W.; Riggs, S.C.; Chu, J.-H.; Lv, B.; Hu, J.; Hashimoto, M.; Mo, S.-K.; Hussain, Z.; Mao, Z.Q.; Chu, C.W.; Fisher, I.R.; Si, Q.; Shen, Z.-X.; Lu, D.H. Observation of universal strong orbital-dependent correlation effects in iron chalcogenides. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 7777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomskii, D.I.; Streltsov, S.V. Orbital Effects in Solids: Basics, Recent Progress, and Opportunities. Chem Rev 2021, 121, 2992–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomskii, D.I. Review—Orbital Physics: Glorious Past, Bright Future. ECS Journal of Solid State Science and Technology 2022, 11, 054004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riera, R.; Cabrera, R.A.R.; Rosas, R.; Riera, R.E.B.; Riera, R.I.B. Correlation Pair Of Electrons Oscillating In Resonant Quantum State To Reach The Critical Temperature In A Metal. International Journal of Current Innovation Research 2018, 4, 1070–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Flagg, E.B.; Muller, A.; Robertson, J.W.; Founta, S.; Deppe, D.G.; Xiao, M.; Ma, W.; Salamo, G.J.; Shih, C.K. Resonantly driven coherent oscillations in a solid-state quantum emitter. Nat Phys 2009, 5, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroche, R.R.; García, Y.M.O.; Arellano, M.A.M.; Leal, A.R. DNA as a perfect quantum computer based on the quantum physics principles. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 11636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroche, R.R.; García, Y.M.O.; Moreno, E.C.S.; Cervantes, J.S.E.; Sulbaran, A.C.M.; Leal, A.R. DNA Gene’s Basic Structure as a Nonperturbative Circuit Quantum Electrodynamics: Is RNA Polymerase II the Quantum Bus of Transcription? Curr Issues Mol Biol 2024, 46, 12152–12173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokura, Y.; Nagaosa, N. Orbital Physics in Transition-Metal Oxides. Science 2000, 288, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.G. Spin-orbit coupling and its effects in organic solids. Phys Rev B 2012, 85, 115201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomskii, D.I.; Streltsov, S.V. Orbital Effects in Solids: Basics, Recent Progress, and Opportunities. Chem Rev 2021, 121, 2992–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streltsov, S.V.; Khomskii, D.I. Orbital physics in transition metal compounds: new trends. Physics-Uspekhi 2017, 60, 1121–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegelman, F.; Tarrat, N.; Cuny, J.; Dontot, L.; Posenitskiy, E.; Martí, C.; Simon, A.; Rapacioli, M. Density-functional tight-binding: basic concepts and applications to molecules and clusters. Adv Phys X 2020, 5, 1710252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, J.; Weinstein, M.I. Tight-binding reduction and topological equivalence in strong magnetic fields. Adv Math (N Y) 2022, 403, 108343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.-Y.; Song, Y. Orbital-selective Mott phase of Cu-substituted iron-based superconductors. New J Phys 2016, 18, 073006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, C.L. Physical Organic Chemistry. In Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology; (Elsevier, 2003), pp. 211–243.

- Gorelsky, S.I. Quantitative descriptors of electronic structure in the framework of molecular orbital theory. Adv Inorg Chem 2019, 191–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darari, M.; Francés-Monerris, A.; Marekha, B.; Doudouh, A.; Wenger, E.; Monari, A.; Haacke, S.; Gros, P.C. Towards Iron(II) Complexes with Octahedral Geometry: Synthesis, Structure and Photophysical Properties. Molecules 2020, 25, 5991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, K.; Hu, W.; Yang, J. Spin–Orbit Coupling in 2D Semiconductors: A Theoretical Perspective. J Phys Chem Lett 2021, 12, 12256–12268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Köppel, D.R. Yarkony, and H. Barentzen, editors, The Jahn-Teller Effect (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2009).

- Kaplan, M.D.; Zimmerman, G.O.; editors, Vibronic Interactions: Jahn-Teller Effect in Crystals and Molecules (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2001).

- Streltsov, S.V.; Khomskii, D.I. Jahn-Teller Effect and Spin-Orbit Coupling: Friends or Foes? Phys Rev X 2020, 10, 031043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.-C.; Ye, Q.-J.; Zhu, Y.-C.; Li, X.-Z. Crystal-Structure Matches in Solid-Solid Phase Transitions. Phys Rev Lett 2024, 132, 086101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietveld, I.B. Solid-solid Phase Transitions between Crystalline Polymorphs of Organic Materials. Curr Pharm Des 2023, 29, 445–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Balents, L. Theory of the Ordered Phase in A-site Antiferromagnetic Spinels. Phys Rev B 2008, 78, 144417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-C.; Chang, C.-R. Goodenough-Kanamori-Anderson Rules in CrI3/MoTe2/CrI3 Van der Waals Heterostructure. J Electrochem Soc 2022, 169, 053507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfeld, K.; Daghofer, M.; Oleś, A.M. Spin-orbital physics for p orbitals in alkali RO2 hyperoxides—Generalization of the Goodenough-Kanamori rules. EPL (Europhysics Letters) 2011, 96, 27001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovyev, I.V.; Ushakov, A.V.; Streltsov, S.V. Origin of ferromagnetic interactions in NaMnCl3: How the response theory reconciles with Goodenough-Kanamori-Anderson rules. Phys Rev B 2022, 106, L180401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J.; Cooper, L.N.; Schrieffer, J.R. Theory of Superconductivity. Physical Review 1957, 108, 1175–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J.; Cooper, L.N.; Schrieffer, J.R. Microscopic Theory of Superconductivity. Physical Review 1957, 106, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Gao, J.; Cao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liang, A.; Xu, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Huang, K.; Xu, L.; Wang, C.; Cui, S.; Wang, M.; Yang, L.; Luo, X.; Sun, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y. Observation of Mott instability at the valence transition of f-electron system. Natl Sci Rev 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raychaudhuri, P.; Dutta, S. Phase fluctuations in conventional superconductors. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2022, 34, 083001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loon, E.G.C.P.; Krien, F.; Hafermann, H.; Lichtenstein, A.I.; Katsnelson, M.I. Fermion-boson vertex within dynamical mean-field theory. Phys Rev B 2018, 98, 205148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalian, J. Failed Theories of Superconductivity. Modern Physics Letters B 2010, 24, 2679–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, M.C.; Saal, C. Quantum statistical analysis of superconductivity, fractional quantum Hall effect, and aromaticity. Int J Quantum Chem 2000, 79, 125–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J.E. BCS theory of superconductivity: it is time to question its validity. Phys Scr 2009, 80, 035702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Adroja, D.; Voneshen, D.; Bewley, R.I.; Zhang, Q.; Tsirlin, A.A.; Gegenwart, P. Nearest-neighbour resonating valence bonds in YbMgGaO4. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 15814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousochatzakis, I.; Sizyuk, Y.; Perkins, N.B. Quantum spin liquid in the semiclassical regime. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, L.-F.; Moreo, A.; Dagotto, E. Theoretical study of the crystal and electronic properties of α−RuI3. Phys Rev B 2022, 105, 085107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArdle, P.; Huang, F.-T.; Yang, J.; Chu, M.-W.; Cheong, S.-W.; Qazilbash, M.M. Orbital-selective metallicity in the valence-bond liquid phase of Li2RuO3. Phys Rev B 2022, 105, 245148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasquilla, J.; Chen, G.; Melko, R.G. Tripartite entangled plaquette state in a cluster magnet. Phys Rev B 2017, 96, 054405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Lee, P.A. Emergent orbitals in the cluster Mott insulator on a breathing kagome lattice. Phys Rev B 2018, 97, 035124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, J.; Flint, R. Symmetric spin liquids on the stuffed honeycomb lattice. Phys Rev B 2020, 101, 115103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, P.; Daghofer, M. Comparing the influence of Floquet dynamics in various Kitaev-Heisenberg materials. Phys Rev B 2022, 105, 085144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Sarkar, S.; Phase, D.M.; Raghunathan, R. Emergence of exotic electronic and magnetic phases upon electron filling in Na2BO3 (B = Ta, Ir, Pt, and Tl): a first-principles study. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2024, 26, 16782–16791. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, P.W.; Baskaran, G.; Zou, Z.; Hsu, T. Resonating-valence-bond theory of phase transitions and superconductivity in La2CuO4-based compounds. Phys Rev Lett 1987, 58, 2790–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaguchi, S.; Shimajiri, T.; Akutagawa, T.; Fukushima, T.; Ishigaki, Y.; Suzuki, T. Chalcogen-Peierls Transition: Single-Crystal-to-Single-Crystal Transition from a Two-Dimensional to a One-Dimensional Network of Chalcogen Bonds at Low Temperature. Bull Chem Soc Jpn 2023, 96, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseska, M.; Sutar, P.; Vaskivskyi, Y.; Vaskivskyi, I.; Vengust, D.; Svetin, D.; Kabanov, V.V.; Mihailovic, D.; Mertelj, T. First-order kinetics bottleneck during photoinduced ultrafast insulator–metal transition in 3D orbitally-driven Peierls insulator CuIr2S4. New J Phys 2021, 23, 053023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulsky, E.G.; Long, J.R. Dimensional Reduction: A Practical Formalism for Manipulating Solid Structures. Chemistry of Materials 2001, 13, 1149–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wezel, J.; van den Brink, J. Orbital-assisted Peierls state in NaTiSi2O6. Europhysics Letters (EPL) 2006, 75, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.R.; McCarty, L.S.; Holm, R.H. A Solid-State Route to Molecular Clusters: Access to the Solution Chemistry of [Re6Q8]2+ (Q = S, Se) Core-Containing Clusters via Dimensional Reduction. J Am Chem Soc 1996, 118, 4603–4616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouget, J.-P. Spin-Peierls, Spin-Ladder and Kondo Coupling in Weakly Localized Quasi-1D Molecular Systems: An Overview. Magnetochemistry 2023, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, T.; Gonzalez-Cuadra, D.; Lewenstein, M.; Tagliacozzo, L.; Zakrzewski, J. Devil’s staircase of topological Peierls insulators and Peierls supersolids. SciPost Physics 2022, 12, 076. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, T.; Pan, J.; Chow, T.P.; Aboalsaud, A.M.; Lai, Z.; Sheng, P. Peierls-type metal-insulator transition in carbon nanostructures. Carbon N Y 2021, 172, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, G.; Luo, J.L.; Ma, Y.C.; Wu, D.; Zhu, B.P.; Tang, Z.; Shi, J.; Wang, N.L. Optical study of MgTi2O4: Evidence for an orbital-Peierls state. Phys Rev B 2006, 74, 245102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, T.; Chen, Y.; Kono, Y.; Takahashi, S.; Kasai, H.; Campi, D.; Bernasconi, M.; Ohara, K.; Yumoto, H.; Koyama, T.; Yamazaki, H.; Senba, Y.; Ohashi, H.; Inoue, I.; Hayashi, Y.; Yabashi, M.; Nishibori, E.; Mazzarello, R.; Wei, S. Pressure-induced reversal of Peierls-like distortions elicits the polyamorphic transition in GeTe and GeSe. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 7851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.H.; Suh, D.H. Experimental realization of Majorana hinge and corner modes in intrinsic organic topological superconductor without magnetic field at room temperature. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.05978. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, X.-L.; Hughes, T.L.; Raghu, S.; Zhang, S.-C. Time-Reversal-Invariant Topological Superconductors and Superfluids in Two and Three Dimensions. Phys Rev Lett 2009, 102, 187001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.H.; Suh, D.H. The Origin of Aromaticity: Aromatic Compounds as Intrinsic Topological Superconductors with Majorana Fermion,” arXiv 2021. arXiv:2101.09958.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).